Victory in Europe: Germany's Surrender and Aftermath

April–July 1945

Contents

Overview

Around 1530 on 30 April 1945, in the spacious command bunker under his chancellery in Berlin, Adolf Hitler, styled Führer (leader) of what he had touted as a thousand-year Greater Germany, died by his own hand. The dictator’s mistress and a number of close followers joined him in death. Above the bunker, the old men and boys of the German home guard and a few depleted regular military units still fought the Soviet Red Army in the ruins of Germany’s capital. Hitler’s so-called testament, a diatribe against all those he held responsible for Germany’s defeat, named Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, the commander in chief of the German Kriegsmarine (navy) as his successor.

The Third Reich’s internal situation in the late spring of 1945 was dire. Despite concerted German attempts at production decentralization and facility dispersal, Allied strategic bombing raids had destroyed most of the country’s industrial infrastructure as well as its major population centers. Refined fuel of any kind was at a premium, grounding most of what remained of the German air force und adversely impacting the mobility of the ground forces. Much of the civilian population was homeless, subsisted on inadequate rations, and could be only marginally accommodated by what remained of the relief services. The influx of refugees fleeing the advance of the Red Army in Germany’s eastern provinces strained this fragile net to the breaking point. In desperation, and clearly sensing that its end was near, the Nazi power structure appeared determined to lash out against as many perceived enemies as possible before its demise. Thousands of still-surviving concentration camp inmates were forced on death marches into the country’s interior or just murdered in place. Numerous political prisoners, many incarcerated since before the war, were executed. Military personnel suspected of malingering or desertion were summarily shot or hanged, as were many civilians who ventured to express dissent or “defeatist” sentiments and forcibly conscripted foreign laborers suspected of being saboteurs.

After crossing the Rhine in late March, U.S., British, and French forces had established large bridgeheads on the east bank of the river. By the beginning of May, the western Allies had surrounded and destroyed several German army groups in western and central Germany, and had linked up with Soviet troops at the Elbe River. Hundreds of thousands of German troops were now prisoners of war. Advancing to the south and southeast, Americans and British had pushed into Austria and Czechoslovakia. On 2 May, German forces in Italy and Austria surrendered to Allied forces advancing northward through Italy. Despite encountering fierce German resistance, the Red Army had fought its way through eastern Germany, and had surrounded and assaulted Berlin. The survivors of the city’s garrison surrendered on 2 May.

Facing insurmountable odds, Doenitz’ sole focus as head of state was to ensure the maritime evacuation from the country’s Baltic provinces to western Germany of as many German troops and civilians as possible before the few ports remaining in German hands fell to the Soviets. On 5 May, a day after German forces in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northwestern Germany had surrendered to the British army, Doenitz made contact with the supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, in Rheims, France, in order to negotiate Germany’s surrender. Doenitz, from his headquarters in the northern German port city of Flensburg, attempted to draw out negotiations as long as possible in order to continue the German withdrawal in the east. However, Eisenhower did not tolerate German stalling and, early on 7 May, the German armed forces chief of operations, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, signed the instrument of unconditional surrender in Rheims (the ceremony was repeated, albeit with Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel as the German signatory, by the Soviets in Berlin late on 8 May). The surrender, affecting all German forces, went into effect at 2301 on 8 May. World War II in Europe had ended.

The Battle of the Atlantic Won

By mid-1943, the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic had definitively turned in favor of the Allies. Improved U.S. and British ASW tactics, new technology, ability to crack German naval codes, and expanded air and surface coverage took a steady and increasing toll of the German U-boat force—and of its highly trained personnel. Such German innovations as radar picket submarines, heavier antiaircraft armament, and improved ESM were unable to counter this trend. The June 1944 Allied landings in Normandy and subsequent advance through northern France cut the German submarine force off from its bases on the French Atlantic coast. The U-boats deploying from bases in Norway or northern Germany spent most of their combat patrols avoiding Allied aircraft and surface forces. It was clear that the survivability of conventional diesel-electric submarines was severely limited in this operational environment.

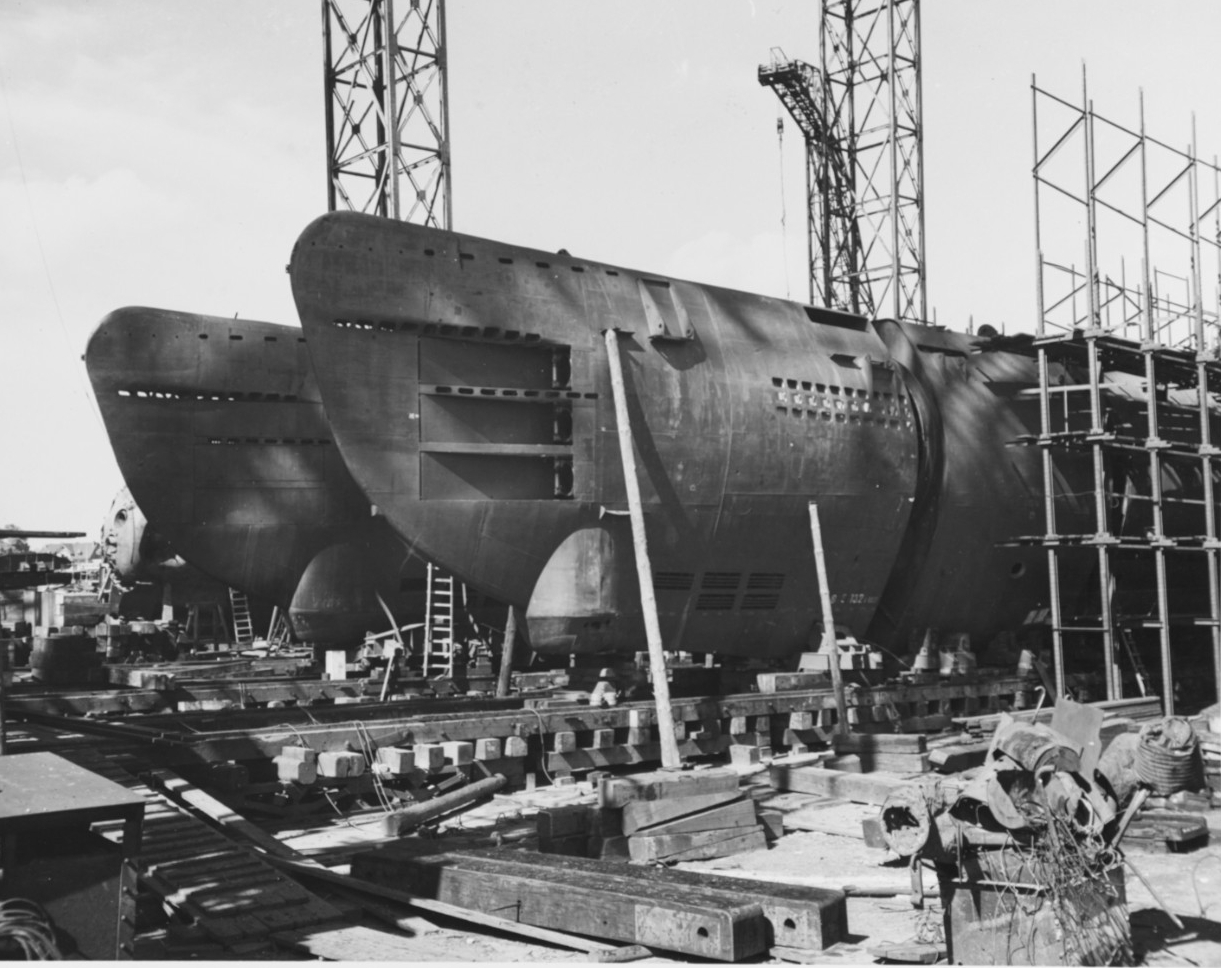

In response, the Kriegsmarine accelerated the development of snorkel arrays, which allowed submerged diesel propulsion and battery replenishment. More important, two advanced submarine models, the Type XXI ocean boat and the smaller Type XXIII coastal boat entered production in late 1944. These so-called Elektroboote were designed to operate submerged for much longer periods. Thus, they featured high-capacity battery arrays, radically streamlined hulls and sails that enabled high submerged speeds, power-assisted torpedo reloading, and better crew accommodations than previous U-boat models. However, their operational impact was negligible at best: only five Type XXI boats and one Type XXIII actually got underway for combat patrols before the war ended. Moreover, Allied analysis of captured boats and unfinished hulls revealed numerous structural and systems deficits entailed by primitive circumstances in which the residual German war industry was operating at war’s end.

The last Allied ship lost to a U-boat in U.S. waters was the merchant steamer Black Point, sunk on 5/6 May 1945 off Rhode Island. The last actions in the Battle of the Atlantic occurred on 7/8 May, when a U-boat was detected and sunk by a Royal Air Force Catalina patrol aircraft, and two Allied merchant vessels were lost in the North Sea off Scotland.

Ahead of the Allied ground advance, 55 U-boats were scuttled in the Baltic and North Sea between 1 and 4 May. On 5 May, while surrender negotiations were ongoing, it appears that Doenitz’ staff transmitted the codeword “Regenbogen” (“Rainbow”), the signal to scuttle all boats. Doenitz apparently recalled the order within eight minutes, but an additional 87 submarines were scuttled by their crews that day. Of the remaining U-boats, 98 surrendered in German and Norwegian ports, and 52 at sea; four underway boats managed to reach neutral ports in Portugal and South America. On 14 May, off Portsmouth, New Hampshire, U-805 was the last boat to surrender to the U.S. Navy.

Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz in British custody after his arrest on 23 May 1945. Behind him are Armaments Minister Albert Speer and Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff Generaloberst Alfred Jodl. As Hitler's chosen successor from 30 April, Doenitz negotiated the capitulation of German forces in western Europe. Jodl signed the unconditional German surrender on 7 May at the Allied headquarters in Rheims, France (© IWM BU 6711).

Demobilization of the Kriegsmarine

Germany’s surrender found most of the surviving Kriegsmarine surface units returning or already in German and Danish North Sea and Baltic ports. Up to the last moment, the German navy and the German merchant fleet had continued to carry out the evacuation of refugees and troops from Germany’s Baltic provinces, which were encircled by and due to fall to the Red Army. Between January and 8 May 1945, nearly 1.5 million civilians and more than 500,000 military personnel were sealifted to Danish and western German ports—to date, the largest maritime evacuation in history. The German warships, mostly smaller combatants, surrendered to British and U.S. forces. According to the terms of the surrender, no equipment was to be damaged and vessels were not to be scuttled.

A number of surviving Kriegsmarine vessels were distributed among the Allied navies. The U.S. Navy received the last-surviving German capital ship, heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, two destroyers, six minesweepers, several patrol craft, and two Type XXI U-boats, U-2513 and U-3008. After the Navy passed on her, the U.S. Coast Guard received the barque Horst Wessel, subsequently renamed Eagle (WIX-327) and still in commission today as a sail training vessel.

Prinz Eugen, in port in Wilhelmshaven, was redesignated IX-300 and sailed for Boston in 13 January 1946, arriving there 11 days later. At this point, her crew comprised 574 former Kriegsmarine officers and enlisted personnel, supervised by eight U.S. Navy officers and 85 sailors. The German sailors (released back to Germany on 1 May) were retained due to their familiarity with the ship’s complex propulsion system. In Boston, the ship was extensively examined, with particular attention devoted to her advanced fire control systems and electronic support measures (ESM). On 3 March, a U.S. crew took IX-300, at this point suffering constant propulsion breakdowns, to the Pacific via the Panama Canal. On 25 July, she was a target ship in Operation Crossroads’ Baker atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll, but remained afloat. Decommissioned on 29 August, the ship was subsequently towed to Kwajalein Atoll, where she capsized before she could be beached. Her wreck remains there to this day.

Following extensive overhauls, both U-2513 and U-3008 were commissioned as U.S. Navy vessels, retaining their German hull numbers. Both served in routine operations and as test beds for what became the Navy’s Greater Underwater Propulsion Power Program (GUPPY). U-3008 was decommissioned in June 1948, but continued to serve as a test hulk until 1954, when she was scuttled, subsequently raised, and sold for scrap. U-2513 was decommissioned in 1949, served as a target vessel, and was sunk west of Key West in 1951.

A considerable number of German mine warfare vessels was kept in service and their crews were not demobilized, but were retained in order to provide salvage and de-mining services. On 1 August 1945, these units were organized into the German Minesweeping Administration (GMSA), essentially as Allied Forces employees. The GMSA, at its peak comprising more than 28,000 personnel and nearly 400 vessels, was primarily administered by the Royal Navy, with some material support from the U.S. Navy. More than 2,700 mines were cleared in the North Sea and Baltic by the service before it was largely disbanded in January 1948. However, two of its flotillas remained in service and were incorporated into the West Germany’s new Bundesmarine in 1955.

Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz was arrested by the British forces on 23 May 1945 and was subsequently tried at the Nuremberg war crimes trials. Ultimately, he was found guilty of two counts (planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression; and crimes against the laws of war) and imprisoned for ten years. Interestingly, a charge concerning Germany’s conduct of unrestricted submarine warfare was dropped due to a written statement from Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who affirmed that the U.S. Navy had carried out unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan since the formal U.S. declaration of war on 8 December 1941.

President Harry S. Truman (right center, in light cap) leaves USS U-2513 after visiting the former German Type XXI submarine on 5 December 1947 at Key West Naval Station, Florida. Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy is at the far right. During a previous visit in November 1946, Truman became the second U.S. president (after Theodore Roosevelt) to travel submerged on a submarine. At that time, U-2513's snorkel array was demonstrated to him (NH 99322).

The Potsdam Conference

A post-war conference of Allied leaders was held from 17 July to 2 August 1945 in the Berlin suburb of Potsdam. Although the “Big Three” included two new members—U.S. President Harry S. Truman and British Prime Minister Clement R. Attlee—the conference was envisioned as a continuation of national leadership meetings held during the war. However, national goals, priorities and level of engagement varied widely. Truman, although much more wary of Stalin than Franklin D. Roosevelt, had only become President three months earlier after Roosevelt’s death and had not yet attained a high level of experience in representing the United States in the international arena. Attlee, on the other hand, was intent on maintaining good relations with the Soviet Union. Moreover, after besting Winston Churchill in Britain’s 1945 general election, his priorities were to rebuild his war-torn nation, address the dissolution of the British Empire, and push broad nationalization programs and healthcare system reforms. Stalin, well aware of the moral pressure imposed on the western Allies by the extreme human losses suffered by the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front, was adamant about maintaining Soviet hegemony in eastern Europe. France, the other major Allied power, had not been invited to participate due to early occupation policy disagreements and the country’s insistence on reoccupying its prewar colonies in Indochina.

Differences in outlook, tensions among the participants, and the western Allies’ growing skepticism about the Soviet Union’s clearly expansionist agenda made negotiations difficult. Nevertheless, agreement was ultimately reached on a broad policy for the post-war administration of Germany:

- Germany was to be demilitarized, denazified, and democratized.

- Germany and Austria, and their capitals (Berlin, Vienna), were to be divided into four occupation zones.

- An Allied war crimes tribunal to try German war criminals was to be established.

- All German annexations in Europe were to be reversed and Germany's eastern border to be shifted westward.

- Most German populations remaining outside the country’s new eastern border were to be expelled and repatriated to Germany.

- The Soviet Union was to draw war reparations from its occupation zone in Germany.

- German standards of living were not to exceed the European average.

- German industrial war potential was to be dismantled or destroyed (as was most heavy industry), and the economy was to be reorganized and based on agriculture and light manufacturing.

Important for the continuing persecution of the war against Japan was the Potsdam Declaration, announced on 26 July. This ultimatum, agreed to by the United States, Britain, and China (the Soviet Union, still maintaining neutrality toward Japan at this date, abstained), unequivocally stated the terms of Japanese surrender.

U.S. Navy Exploitation of Advanced German Technology

The Allies had learned about many details of the extensive German research in new weapons systems, jet aircraft designs and propulsion, and the integration of advanced technology in ground, air, and sea warfare through intelligence reporting, POW interrogation, and captured materials. Planning to leverage German technology in the war against Japan after the defeat of Germany began in 1944. The “U.S. Naval Technical Mission in Europe” (NavTecMisEu) was established on 26 December 1944 and activated on 20 January 1945. The chief of the Naval Technical Mission was designated as the direct representative of Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief, U.S Fleet. However, in the field, the mission was subject to operational control of Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Naval Forces Europe. NavTecMisEu was organized into a technical and a service branch. The former encompassed ordnance, ships, air, yards and docks, electronics, and hydrogen peroxide (missile propellant) sections. The latter included standard staff functions: administration, intelligence, operations, and supply.

Despite focusing on naval service–specific areas of interest, mission personnel were often to work jointly with their U.S. Army and government agency civilian counterparts, particularly in areas in which service interests coincided, such as German missile systems. Staging in Britain in early 1945, the mission deployed to Germany in March after a number of major German cities west of the Rhine had fallen to the Allies. Four forward headquarters to support field activities were eventually established in Germany before and after VE-Day, covering the western Allies’ occupation sectors. Until it was decommissioned in November 1945, nearly 1,000 naval officers, enlisted personnel, and civilian specialists and technicians served with the mission. NavTecMisEu filed 240 letter reports (summary dispatches) and 350 detailed technical reports. The highest priority was given to technology applicable in the war against Japan. The mission’s work provided often-key information and materials in support of a number of the Navy’s important technical programs. Some areas covered:

- Industrial production of hydrogen peroxide

- Rocket-assisted projectiles

- Guided and ballistic missile technology, to include V-1 and V-2 missiles

- Synthetic fuel development

- Advanced torpedoes

- Submarine gas turbines and closed-cycle diesel engines

- Submarine snorkel arrays

- Shipboard ESM

- Advanced piston-engine and jet aircraft to include the Dornier Do-335, Messerschmitt Me-262, and Arado Ar-234 (several of the German aircraft transshipped to the United States by the mission remain in national museum collections today)

- Jet engine technology

- Assessment, disassembly, and transshipment of a Mach-4.2 wind tunnel

Of note, the mission’s work was augmented by the U.S. strategic joint program Operation Paperclip, which sought out German scientists and technical specialists for U.S. government work. One of these, Dr. Herbert A. Wagner, who had been a key figure in the development of German radio-guided glide bombs, was notable for his work in post-war U.S. Navy missile programs.

Although any application of German weapons technology by the Navy in the Pacific War was preempted by Japan’s surrender, the technical information and hardware collected by NavTecMisEu provided the basis for a broad spectrum of post-war weapons systems research and development.

—Carsten Fries, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, March 2020

Further Reading

Bessel, Richard. Germany, 1945: From War to Peace. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

Blair, Clay. Hitler’s U-Boat War, Vol. 2: The Hunted, 1943–1945. New York, Random House, 1998.

Hastings, Max. Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944–1945. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Leahy, William D. I Was There: The Personal Story of the Chief of Staff to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman Based on His Notes and Diaries Made at the Time. New York: Whittlesey House, 1950.

Mallmann Showell, Jak P. Hitler's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Kriegsmarine, 1939–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009.

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. United States Naval Administration in World War II: Technical Mission in Europe. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1976.

Taylor, Telford. The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Other Resources

Victory in Europe Day: A Selected Bibliography

U.S. Navy at War: Final Official Report—covers the period 1 March to 1 October 1945, by Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations

The Trial of Admiral Doenitz—condensed from the report of U.S. naval officers designated to attend the Nuremberg war crimes trial for the purpose of studying the cases of Grossadmiral Erich Raeder and Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz

Conduct of War at Sea—essay by Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz published 15 January 1946 by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI)

Papers of Admiral Howard Stark—documents relating to Victory in Europe (VE) Day, including radio broadcast transcripts and letters of interest

Papers of Captain John P. Bracken, USNR—summary and finding aid of papers that, among other subjects, cover Captain Bracken’s participation in the Nuremberg war crimes trials as a U.S. Navy liaison to U.S. Chief of Prosecution Justice Robert Jackson

Inter-Allied Naval Relations and the Birth of NATO—presentation from Colloquium on Contemporary History No. 8, 14 June 1993

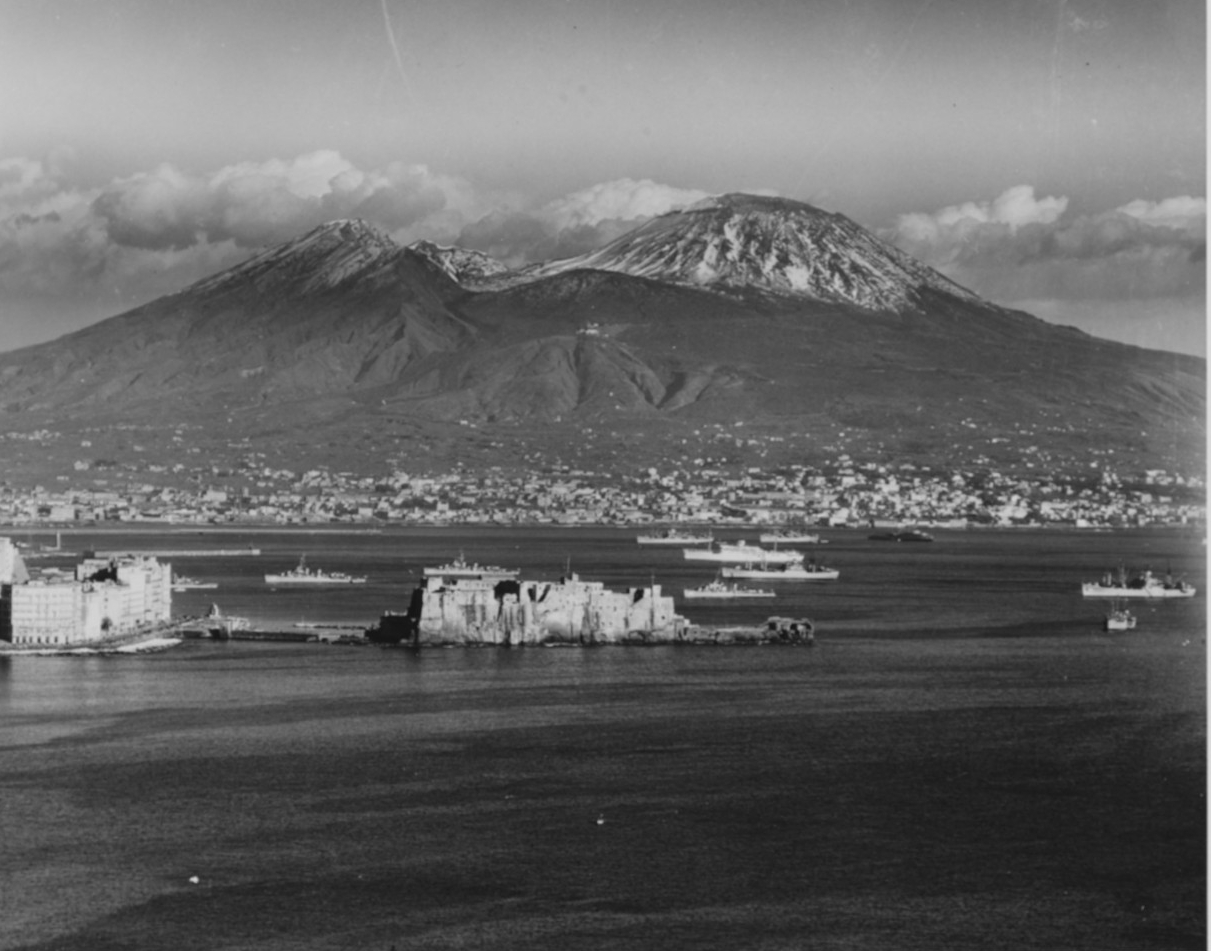

The NATO alliance was a product of post–World War II turmoil and confrontation between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union. To this day, the U.S. Sixth Fleet, based in Naples, Italy, remains an important component of the alliance's force structure. Here, Sixth Fleet ships are shown in port Naples, circa 1955. Destroyers in left center are USS Preston (DD-795) and USS Irwin (DD-794). Destroyer in the center, slightly to the right, appears to be USS Bordelon (DDR-881). The other U.S. Navy ships present are mainly amphibious types (NH 99290).