Battle of the Atlantic—Continued

The Establishment of Tenth Fleet and Focus on Antisubmarine Warfare

Although the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 immediately provoked widespread anger and determination to fight back, the initiation of numerous German submarine attacks on shipping along the eastern seaboard the month following aroused much less public fury. U.S. naval and political leaders certainly were much concerned about the heavy loss of merchantmen and tankers, but they were ill-prepared to respond effectively. Several organizations within the Navy, Army Air Force, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine gradually took action from January 1942 through April 1943 to counter the U-boat menace; however, the overall effort lacked sufficient coordination.1 In May 1943, therefore, Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief U.S. Fleet (COMINCH), rationalized the overall effort by creating an unprecedented organization: a fleet with no ships assigned. Officially established on 20 May, Tenth Fleet took control of the U.S. Navy’s antisubmarine warfare (ASW) battle in the Atlantic and, in the process, adopted a number of organizational measures that were to become standard in the 20th century.2

How had the United States' ASW campaign fared to this point?3 The first half of 1942 bordered on catastrophe, with the United States losing more merchant marine tonnage in combat than it had during its 19-month direct participation in World War I.4 In May, German U-boats, already having sunk scores of freighters and tankers sailing independently up and down the East Coast, shifted to hunting in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. U.S. citizens generally were ignorant of the extent of the early losses, however, partly because American propaganda downplayed their scale and fabricated claims of successful attacks against the German predators. However, the reality early on was that relatively small numbers of inexperienced and poorly equipped American escort and reconnaissance crews struggled in vain to stop the onslaught.

Implementation of convoys, increasing production of naval and merchant vessels, development of new technologies and doctrine, and faster sharing of intelligence somewhat improved the situation in the second half of 1942. Certainly a major success was the unmolested transport across the Atlantic of an enormous amphibious force for Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa in November. Then, severe weather in the winter of 1942–43 limited the U-boats’ effectiveness, although it also resulted in 91 Allied merchant losses in the Atlantic alone.5 However, in March 1943, the number of merchantmen lost to enemy action in the Atlantic and Arctic rose to 95. With Germany’s industrial production also ramping up and her submarine force apparently on the verge of commencing another lethal rampage at sea, Admiral King decided to reorganize.

_______________

1 For a look at one early and ineffective ASW effort, see discussion of the role of so-called Q-ships in World War II in the NHHC Library Online Reading Room. This resource may also be used for archival research queries on the Merchant Marine in World War II. For multiple perspectives on the Battle of the Atlantic, see Timothy J. Runyan and Jan M. Copes, eds., To Die Gallantly: The Battle of the Atlantic (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1994).

2 Julius August Furer, Administration of the Navy Department in World War II (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1959), 142.

3 The NHHC 1942 Battle of the Atlantic web page covers multiple aspects of the campaign against German U-boats, including photographs and U.S. and German documents.

4 Samuel E. Morison, History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. I: The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939–May 1943 (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1947), 200.

5 Ladislas Farago, Tenth Fleet, (New York: Ivan Oblensky, 1962), 122; Jonathan Dimbleby, The Battle of the Atlantic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 376–77.

Functioning with a small staff and assigned no ships of its own, Tenth Fleet nevertheless synchronized many existing elements to work more closely in unison. Its Operations Division relied on COMINCH’s own Intelligence Division. Its Anti-Submarine Measures Division, responsible for synchronizing ASW research, training, and material development, tapped into the already existent Anti-Submarine Warfare Operational Research Group (“Asworg”) civilian scientists. The Convoy and Routing Division, previously housed under COMINCH, continued to schedule merchant and tanker convoys, and to coordinate the handoff of their escort coverage from American to Canadian or British elements in the northern or eastern Atlantic.6 In an effort to preserve harmony, Tenth Fleet chose not to issue these convoys’ operational orders directly, but instead sent its “suggestion” or “recommendation” to Atlantic Fleet, whose commander then issued the directive.7 In practice, Tenth Fleet’s performance became that of a brilliant conductor taking over an earnest but somewhat discordant symphony.

To emphasize the importance of Tenth Fleet and to ensure it had ready access to the resources it needed, Admiral King appointed himself as its commander. However, he had far too many responsibilities in the global conflict to focus solely on the new organization, and therefore his chief of staff, Rear Admiral Francis S. “Frog” Low, served as a de facto commander. Having worked previously for King, Low well understood his boss’ intent and predilections. He and his staffers also coordinated effectively with key British and Canadian partners. A firm but humane taskmaster, Low knew how to get the most from his tight-knit staff, which included active and reserve personnel, Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service (WAVES), and civilian scientists.8

The close partnering of science and military operations greatly assisted the ASW effort and would become a catalyst for the Navy’s subsequent development of operational research in the 20th century.9 Civilian scientists, both before and after Tenth Fleet’s establishment, went on missions to observe sailors and aviators in action while escorting convoys or attacking submarines. They gathered and analyzed statistics of engagements closely. Their findings contributed to the highly effective employment of “hunter-killer” escort carrier tactics, one of the U.S. Navy’s most significant contributions to the ASW fight. Finally, the combination of scientists and uniformed Sailors provided valuable input for the development or improvement of equipment such as underwater ordnance, radar, sonar, and high-frequency direction-finder devices (HF/DF or “Huffduff”).10 Of course, German scientists and naval leaders also improved their equipment or developed new tools and accompanying tactics in a race against the Allies’ innovations, but their efforts never again enabled their submariners to dictate the overall battle’s tempo as they had through much of 1942.11

_______________

6 For more on convoy and routing, visit the NHHC Library Online Reading room.

7 Samuel E. Morison, History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. X: The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943-1945 (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1956), 24-25; Farago, Tenth Fleet, 163–216.

8 Morison, The Atlantic Battle Won, 25–26; Farago; Tenth Fleet, 174–81. The NHHC Library contains a brief biography of Admiral Low. He served in the position until the beginning of 1945 when he assumed command of Cruiser Division Sixteen in the Pacific. At Tenth Fleet, Rear Admiral Allan R. McCann became the new chief of staff.

9 Keith R. Tidman, The Operations Evaluation Group: A History of Naval Operations Analysis (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1984), 1-96.

10 For a more detailed description of the U.S. ASW organization and its challenges prior to Tenth Fleet, see Morison, The Battle of the Atlantic, 202–65. For developments from May 1943 onward, see Morison, The Atlantic Battle Won, 32–54, and Farago, Tenth Fleet, 206–43.

11 An overview of Germany’s technical development efforts may be found in the NHHC Library Online Reading Room.

Tenth Fleet’s leveraging of science complemented a highly efficient intelligence effort, one of the keys to victory. Offsetting the submarine’s inherent advantage gained by hiding below the surface, staffers continuously plotted confirmed or suspected U-boat contacts via the reports received from multiple sources. Tips came from British intelligence, spotters operating near German submarine bases in France, or miscellaneous civilian vessels at sea. Meanwhile, HF/DF technicians located at stations rimming the Atlantic triangulated and drew a “fix” on the radio transmissions that U-boat commanders frequently sent back to U-boat command. In 1943, Ultra cryptological intercepts also increasingly helped insert pieces into the puzzle.12 With its understanding of the approximate locations of individual subs or those clustered in “wolf packs,” the Navy could re-route select convoys or send hunter-killer groups to intercept the enemy. By the summer of 1943, the Allies clearly had a better understanding of U-boat command’s operations than vice-versa.

Both sides’ continuous development of new equipment and tactics created demand for ever-evolving and relevant training. From the beginning of its ASW campaign, the United States had instituted a training program, but Tenth Fleet brought further synchronization to the effort. For example, beginning in June 1943, the Navy began publishing a monthly classified U.S. Fleet Antisubmarine Bulletin to disseminate the latest findings from and to the fleet. This compendium of shared lessons and evolving doctrine, which colloquially was known as the “Yellow Peril,” was produced in part by Tenth Fleet’s cadre of WAVES.13 Tenth Fleet also coordinated with dispersed training schools comprising an “Antisubmarine University” that continuously imparted the latest techniques to the growing fleet.14

It is highly likely that the Allies would have prevailed in the Battle of the Atlantic even if Tenth Fleet had never appeared, but the record also strongly suggests that its establishment helped determine the outcome more quickly. When Tenth Fleet began in May 1943, there had been an average of 108 U-boats operating daily at sea—the all-time high—but in August that number had fallen to 51. For the first time, the United States sank more submarines in July 1943 than did the British. After that month, the figures for tonnage lost to submarine attacks in the Atlantic were generally between one tenth and one quarter of what they had been from early 1942 through mid-1943.15

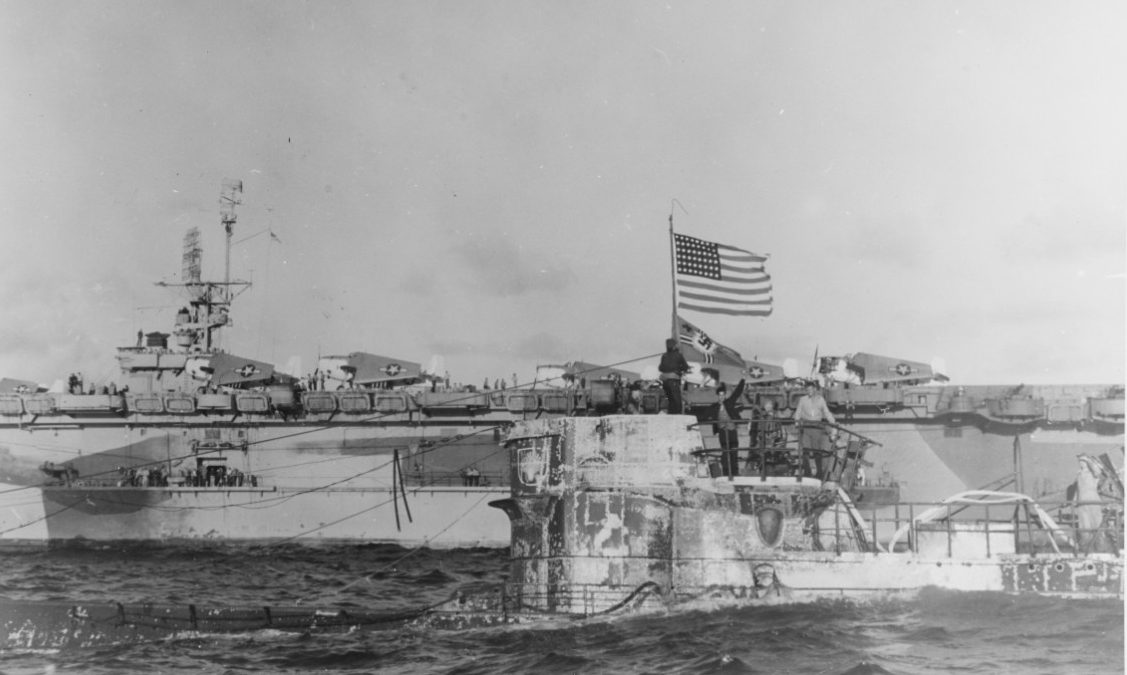

The great improvement during the summer of 1943 fortuitously aligned well with Operation Bolero, the amassing of men and material for an invasion of western Europe. In fact, just two days prior to D-Day, the U.S. Navy scored one of its more remarkable actions in the Battle of the Atlantic. Captain Daniel V. Gallery, commanding the escort carrier group led by Guadalcanal (CVE-60), had for weeks directed his group’s destroyers to practice boarding operations in the hope of gaining an incredibly valuable prize. In late May, his hunter-killer group received a Tenth Fleet–generated tip about a sub off the west coast of Africa and, on 4 June, it captured U-505. Subsequently towed to Bermuda, the boat yielded a trove of intelligence.16

A month prior to U-505’s capture, Germany had deployed a group of newly-developed, snorkel-equipped submarines that could endure much longer submersion periods, but these and other technical counter efforts would have little material impact on the overall campaign. The Allied invasion of France had forced Germany to relocate submarine bases to German-controlled Scandinavian areas or to Germany itself. Meanwhile, the deadly effectiveness of the Allies’ ASW tactics meant that experienced U-boat commanders were becoming scarcer.17

The entry of Tenth Fleet into the Battle of the Atlantic in May 1943 illustrates the importance of occasionally assessing the structure and functionality of an organization engaged in a vast and complex effort. Admiral King’s move to reorganize the United States ASW effort and his initial appointment of Rear Admiral Low empowered the many constituent parts to “pull together” more efficiently and effectively. The new organization may not have been the determining factor in the Battle of the Atlantic, but Tenth Fleet saved lives, equipment, and ships on the high seas and thus helped bring to a faster conclusion the war on land.

—Jon Middaugh, Ph.D., Histories and Archives Division, Naval History and Heritage Command, April 2018

_______________

12 Jerry Russell, “Ultra and the Campaign Against the U.Boats in World War II,” (Carlisle Barracks, PA: May 1980).

13 Morison, The Atlantic Battle Won, xii; Farago; Tenth Fleet, 176.

14 Morison, The Battle of the Atlantic, 47–64.

15 Morison, The Atlantic Battle Won, 366; Farago, Tenth Fleet, 200–201. Figures for the average numbers of U-boats operating daily at sea are for the Atlantic and Indian Oceans but not the Arctic, Baltic, Black, or Mediterranean Seas.

16 The NHHC photo archives contain images of the dramatic capture of U-505. A glimpse at the intelligence derived from the capture of U-505 may be found in the NHHC Library Online Reading room.

17 Dimbleby, The Battle of the Atlantic, 416–17; Farago, Tenth Fleet, 246–47.