Guadalcanal I (CVE-60)

1943–1958

The Japanese invaded Tulagi in the Solomon Islands (3–4 May 1942), and subsequently occupied some of the neighboring islands including Guadalcanal, a volcanic island approximately 90 miles long and 25 miles wide. When Allied planners learned in early July that the Japanese began building an airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, they grew concerned that enemy planes flying from the field could savage Allied ships supplying eastern Australia, and support further Japanese landings on the chain of islands stretching across the South Pacific. The Americans consequently resolved to deny the area to the enemy before they could turn it into a bastion and landed on Japanese-held Guadalcanal, Florida, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and Tulagi on 7 August 1942 during Operation Watchtower — the first U.S. land offensive of WWII.

The Americans cleared the other islands of the Japanese during fierce fighting, but the Japanese bitterly contested the landings on Guadalcanal. The fighting raged for months as the enemy poured reinforcements into the island to drive the Americans into the sea, however, despite horrific casualties the Americans gradually won the battle of attrition and drove the enemy across Guadalcanal. The Japanese reluctantly decided to evacuate Guadalcanal, and their organized resistance on the island ended on 9 February 1943, following the final evacuation of their main forces. The Allied victory proved a costly one but rolled the Japanese back from threatening the maritime lifeline to Australia and thrusting at the South Pacific islands.

I

(CVE-60: displacement 7,800; length 512'; beam 65'; extreme width 108'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 19 knots; complement 860; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40 millimeter, 20 20 millimeter, 28 aircraft; class Casablanca; type S4-S2-BB8)

The first Guadalcanal (CVE-60) was converted from Maritime Commission hull MC-1097 by Kaiser Shipbuilding Co., Inc., of Vancouver, Wash. The ship was authorized as an aircraft escort vessel (AVG-60); reclassified to an auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV-60) on 20 August 1942; laid down on 5 January 1943; named Astrolabe Bay (ACV-60) on 22 January 1943; and renamed Guadalcanal (ACV-60) on 3 April 1943.

The ship’s company compiled a Memory Log, and proudly observed that Guadalcanal was named as “a token of respect for those who fought there, and of appreciation for what those men gave and did.”

Guadalcanal was launched on 5 June 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Carol M. Malstrom, wife of Capt. Alvin I. Malstrom; reclassified to an escort aircraft carrier (CVE-60) on 15 July 1943; assigned to Air Force, Atlantic Fleet, on 29 July 1943; and commissioned at Naval Air Station (NAS) Astoria at Tongue Point, Ore., on 25 September 1943, Capt. Daniel V. Gallery Jr., in command.

Capt. Gallery, who had received the Bronze Star while commanding Fleet Air Base Reykjavik, Iceland, during the earlier fighting against German U-boats (submarines), set a hard pace for his crew but also set a confident tone, and as men reported on board they received a memo from the commanding officer:

1. The motto of this ship will be “Can Do,” meaning that we will take any tough job that is given to us and run away with it. The tougher the job, the better we’ll like it.

2. Before a carrier can do its big job of sinking enemy ships, several hundred small jobs have got to be done and done well. One man falling down on a small job can bi___ the works for the whole ship. So learn all you can about your job during this pre-commissioning period. Pretty soon we will be out where it rains bombs and it will be too late to learn.

Note: This ship will be employed on hazardous duty. We will either sink the enemy or get sunk ourselves depending on how well we learn our jobs now and do our jobs later.

ANYONE WHO PREFERS SAFER DUTY SEE ME AND I WILL ARRANGE TO HAVE HIM TRANSFERRED.

D. V. Gallery

Captain, U.S.N.

Guadalcanal completed fitting out, along with a series of drills and loading provisions, on 15 October 1943, and five days later reported to the Pacific Fleet for temporary duty. The ship nosed her way down the Colombia River and completed her shakedown cruise to Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash., where she loaded ammunition and supplies (20–27 October). Heavy seas pounded Guadalcanal during her voyage, and the Memory Log noted that “Someone said, ‘The ship went up and down, my stomach just went up.’”

On 17 August, Composite Squadron (VC) 36 from NAS Alameda, Calif., had been assigned to Guadalcanal. The exigencies of the war, however, drove a change in orders and on 7 September the squadron was transferred to Naval Air Auxiliary Station (NAAS) Holtville, Calif., for night flying training. In the interim, VC-42, Lt. Cmdr. Joseph T. Yavorsky in command, was notified of its deployment to Guadalcanal. The squadron, which had been established on 1 April 1943 at NAS Alameda, Lt. Cmdr. Stuart Stephens in command, trained at Alameda, NAAS Hollister, Calif., NAAS Holtville, and finally moved to NAAS Otay Mesa, near San Diego. Tragedy struck VC-42 when Lt. Cmdr. Stephens fatally crashed while flying a training hop near Monterey Bay on 16 July, and Yavorsky assumed command of the squadron.

The squadron moved onto the ship on Halloween, and she hoisted on board five of its nine Eastern FM-1 Wildcats and five of the 12 Grumman TBF-1 Avengers. The squadron’s orders included a further directive that “streamlined” it by transferring to the ship for permanent duty all but the newly designated streamlined complement of men. Under that new complement, VC-42’s strength remained at 31 officers, but was reduced from approximately 175 to 47 enlisted men. This step marked a turning point in VC-42’s administrative arrangements, for Carrier Aircraft Service Units (CASUs) and Carrier Aircraft Divisions (CASDs) were henceforth to service and maintain the planes. Also the squadron would obtain all of its equipment through the units instead of directly through supply. The eight-day cruise (31 October–8 November) in southern Californian waters thus served a dual purpose: that of breaking these recently transferred maintainers into their new jobs in the ship’s CASD, and that of giving the pilots a chance to complete qualifications.

Gallery made the ship’s first take-off and landing, while flying a North American SNJ-4 Texan, to the accompaniment of cheers from the flight deck crew. Despite the brevity of the voyage, the other pilots experienced their first catapult launches, and VC-42’s historian reported that “the Squadron as a unit began to get the feel of duty afloat.” When they completed their qualifications on the afternoon of the second day, the five Avengers flew ashore to NAS San Diego, carrying as passengers the 11 pilots were to bring back those planes they left at North Island. Four Wildcats and seven Avengers returned to the ship on 4 November, and culminated their flight by successfully simulating an attack on Guadalcanal. The ship launched the five remaining Wildcats on board as a Combat Air Patrol (CAP) in an attempt to intercept the “attackers,” but they reached the Avengers too late to divert the torpedo planes from making their runs. The ship also carried out gunnery practice.

The training did not pass without mishaps, however, and on the 3rd, a Wildcat piloted by Lt. (j.g.) Thomas E. Dunnam Jr., bounced up as it hit the deck and so missed all of the landing wires. The plane rolled in the barrier, damaging its propeller, engine, and starboard landing gear. Five days later another plane, flown by Ens. Alex X. Brokas, hit the barrier, damaging its propeller and engine. When Guadalcanal returned to San Diego, the squadron moved to NAS San Diego, where the men turned over their planes to CASU 5 for servicing. The enlisted men slept in barracks on North Island, but a number of the officers persuaded a Navy representative of the Hotel del Coronado that there were no vacancies in the Bachelor Officer Quarters, and they deserted North Island in favor of luxurious hotel rooms, which the service acquired for them at reasonable prices.

In addition, Lt. Philip J. Berg of VC-42 had worked as a Hollywood agent, and arranged a trip to Los Angeles and Beverly Hills (11–13 November). Capt. Gallery, Cmdr. Henry A. Monat, MC, USNR, Guadalcanal’s surgeon, Lt. William L. Stowell, DC, USNR, the carrier’s dentist, all the officers of the ship’s Air Department, and all of the officers of the squadron, took a bus from the hotel to Berg’s house in Beverly Hills. After a brief respite with libations, the bus took the men to the Beverly Hills Athletics Club, which was to be their headquarters during their sojourn. The men moved on to the Florentine Garden, where an entire section of the night club was reserved for them for the rest of the evening. Six dancers needed partners for a conga routine, and, as the squadron’s historian recorded, the men “hardly had to be coaxed.”

The following day they attended a luncheon at Paramount Studios, after which they toured the studios. Paramount was filming the motion picture Rainbow Island, starring Dorothy Lamour, and between shots the actress and cast members chatted with the men. Not to be outdone, Berg arranged a star-studded reception at Marcelle La Maize’s, another popular nightclub, for that evening. Waiters kept the drinks flowing freely from the open bar while the men gawked in surprise at the other guests: Brian Aherne, Gracie Allen, Edward Arnold, George Burns, Olivia de Haviland, Cecil B. De Mille, Jimmy Durante, Jinx Falkenberg, Joan Fontaine, Judy Garland, Susan Hayward, Charles Laughton, Harpo Marx, Adophe Menjou, Dorris Merit, Frank Morgan, Ray Roberts, Akim Tamiroff, Eva Williams, Kay Williams, and Loretta Young. The guests sat down to a delicious steak dinner at 2030, followed by performances by Gracie Allen and George Burns, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, Harpo Marx, Frank Morgan, and Akim Tamiroff. After the show the guests danced until midnight, and them some departed for after-hours parties. Celebrity columnist Louella Parsons attended and wrote up the affair as “one of the nicest parties ever given in Hollywood.” VC-42’s historian added wryly that the “bus ride back to San Diego the next morning was a very quiet one…”

The squadron’s 31 officers, three chiefs, 44 men, and Prissy boarded the ship on the 15th. A diminutive, talented cocker spaniel, Prissy belonged to Lt. (j.g.) Dunnam and was the only female on board. Her repertoire included begging, jumping over extended arms, playing possum, and rolling over at the expressive command of “Snap Roll!” Prissy served as a “full fledged member” of VC-42, possessed her own log book, and frequently flew in a Wildcat on her master’s shoulder. The dog became a favorite on board Guadalcanal and the ship’s company all but adopted her as their own.

On 15 November 1943, Guadalcanal stood down the channel in company with Mission Bay (CVE-59), and destroyer Welles (DD-628) for the east coast. Mission Bay embarked VC-36, Guadalcanal’s originally intended squadron, save for a detachment of six planes that flew cross-country to NAS Quonset Point, R.I., and Naval Air Facility Mineola, N.Y., for further instruction.

An Avenger, manned by Ens. Richard B. Law, AMM1c L.C. Hubert, and ARM3c W.M. Collins, took off for a routine antisubmarine patrol during the forenoon watch on 19 November. As the plane attempted to land at 1430, the arresting hook failed to lower. “I turned the battery switch to “down,” pressed the circuit breaker, but got no reaction,” Law later explained, “so I immediately tried to pull the emergency release. I could pull it only a few inches before it stuck. After conveying this to the ship by visual signals, I jettisoned my bombs and attempted to shake the hook, using various methods: throwing battery on and off; hook switch up and down; and shaking aircraft violently, while trying to pull emergency release. At about 1530 the ship decided to take me aboard without a hook. I got a wave-off on my first approach, and the second time was cut. I hit the deck short, bounced a little, and floated down the deck into the barrier; hit all three barriers; nosed up; turned the switch and gas off; and got out of my aircraft.” All three men survived without injuries.

The trio of ships sailed southerly courses and on the 22nd began planning a joint mock attack on the Gatun locks of the Panama Canal. Planners devised the attack to test the canal’s defenses, and anticipated that they would face strong “opposition” as soon as the defenders discovered the ships. Gallery, as the senior officer of the task group, thus formulated a daring plan.

Mission Bay was to steam to a point approximately 300 miles south of the canal; and launch its Wildcats at noon the following day. Seven of VC-42’s Wildcats flew from Guadalcanal to Mission Bay and joined those of VC-36. The planes were to form a diversionary group and fly at 1,500 feet, which the planners considered an ideal altitude for radar interception, and on a course directly for the locks. Meanwhile, Guadalcanal was to back-track in order to get into position to launch at 1300 that afternoon from the Gulf of Murcielagos, a point on the western coast of Central America at the borderline of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, and attack the canal from the Atlantic side. Four of VC-36’s TBF-1s flew to Guadalcanal and became part of the attack group.

Gallery and his team considered secrecy essential in order to be able to surprise the defenders, but a Martin PBM-3S Mariner of Fleet Air Wing 3 sighted Guadalcanal just after dark on the 22nd. The Mariner reported the carrier to the authorities ashore and USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberators flew out to “destroy” the “enemy.” The flying boat accurately tracked Guadalcanal and the Liberators reached the area and blanketed her, but the ship’s radiomen in Air Plot worked feverishly in an attempt to pick up the receiving and transmitting frequencies of the bombers, and in a few minutes they intercepted the transmitting frequency. The Army pilots chattered to each other constantly, and by breaking the cardinal rule of radio discipline offered Gallery a priceless advantage.

Shortly after the interception, the radiomen overheard the flight leader say that they would begin attacking one-by-one in 15 minutes, and gave further information as to the angle and direction of the glide, and the interval between the planes governing their attack. The radiomen picked up what they believed to be the plane’s receiving frequency, and Gallery tried one more ruse before the first Liberator turned into its attack run and broke in to their chatter in plain language, without use of the day’s code word, “Return to base.” A wingman apparently heard the message, which the flight leader did not receive, and relayed it, using the proper code word for “base.” The Liberators came about and flew from the scene.

The weather proved favorable for attempting to dodge the shadower and any further attackers, and Gallery resourcefully used the low ceiling, poor visibility, and numerous scattered rain squalls to maneuver through one storm after another, dashing at full speed ahead, and then full astern, and then ahead again, in order to disguise the ship’s wake.

The ships thus attacked, with some modifications to their original plan, on 23 November 1943. Mission Bay sent 14 Wildcats aloft and they lured a large number of Army fighters out to sea, engaging them in mock dogfights. Sadly, one of the Army’s planes spun and crashed, killing the pilot. Another developed engine trouble but landed successfully on a nearby beach, and the pilot emerged unhurt.

Slightly before Mission Bay launched her fighters Guadalcanal, which steamed further to the north, catapulted the main attack group of a dozen Avengers from the two squadrons. Yavorsky led the formation, which winged across the Isthmus over Nicaragua and skirted the east coast to come in for a simulated attack. The weather cleared, but an overcast at 10,000 feet caused problems, though above the overcast an opening of about 500 feet in depth occurred before a second overcast set in. The attack planes flew between the two overcasts, which effectively shielded them from prying eyes as they crossed Costa Rica. Foul weather greeted the Avengers on the Atlantic side, however, and compelled them to divert out to sea before they circled back, letting down consistently to an altitude ranging between 25 and 300 feet, in order to get under the overcast. Rain nonetheless hampered their approach, but they skirted most of the storm and reached land at a point approximately 150 miles north of the Gatun locks.

The attackers flew the rest of their run at nearly tree top level, and saw numerous alligators in the swampy terrain, which VC-42’s historian observed “presented anything but a comforting spectacle, especially when one thought of a forced landing.” A flight of Army fighters patrolling for the intruders flew overhead at 5,000 feet but apparently missed sighting the Avengers, which may have blended in to the trees as they flew toward the Gatun locks and made simulated attack runs to “smash” and “loose” the trapped water so vital to the locks. The attacking planes pulled out of their runs and landed triumphantly at France Field at Colón and Albrook Field near Balboa in the Canal Zone, where the Wildcats joined them shortly thereafter. Mission Bay moored off Colón on the 24th, and her aircraft that flew in the mock attack rejoined the squadron. At the subsequent critique, the umpires ruled that Yavorsky and his Avengers knocked out the locks.

Guadalcanal tied up at Balboa early on Thanksgiving morning, the 25th. At 1300 the liberty party went ashore, but the men quickly found that Balboa lacked scenery and entertainment and moved on to nearby Panama City. Some of the men compared the narrow streets and the projecting second story balconies, many of which sported lattice railings, with the old French Quarter of New Orleans, La. The stench of the slums, however, became all but unbearable in the humid air, and the brief showers that washed over the area failed to alleviate the men’s misery. Guadalcanal passed through the Panama Canal on 26 November, and was damaged entering a lock when one of her 40 millimeter gun tubs fouled it, so she stopped briefly at Colón to repair the gun and surrounding hull.

Her aircrewmen were given no time to rest on their laurels, however, because a German Type IXC submarine, U-516, Kapitänleutnant Hans-Rutger Tillessen in command, created a stir among the Allied forces in the area as she savaged unescorted ships steaming in Caribbean waters. U-516 torpedoed and sank merchantman Pompoon (1,082 tons), Master Edward Condell and owned by United Fruit Steamship Co., of New York, about 75 miles north of Cartagena, Colombia, near 11°00ˈN, 75°00ˈW, at 0103 on 13 November 1943. Pompoon steamed independently with general cargo and deck cargo of 10-inch steel pipes and steel reinforcing rods from Cristóbal to Barranquilla when the U-boat’s torpedo sliced into her port side amidships. The ship broke in two, and both halves sank so quickly that her 23 crewmen and the four men of her Armed Guard did not have time to lower a lifeboat. Five survivors managed to clamber into a life raft that floated free, but one of them died the following day and was buried at sea. On the afternoon of 3 December, a Panamanian ship picked up the messman of the ship’s company and three men of the Armed Guard who survived and took them to Cristóbal, where they were treated for their severe injuries.

Tillessen surfaced and opened fire without warning on Colombian two-masted schooner Ruby (39 tons), approximately 120 miles north of Colón, near 11°24ˈN, 79°54ˈW, at 0455 on 18 November. Ruby carried a cargo of 21,600 coconuts, 300 bags of copra, 28 hunting rifles, and 15 boxes with empty bottles on a voyage from San Andrés to Cartagena, both in her native country. The Germans fired 30 rounds into Ruby and sank her, killing the master, the mate, and two sailors. Honduran steam merchant Orotava picked up the seven survivors the following day and landed them at Cristóbal on the 20th. German attacks on Colombian vessels such as Ruby became one of the reasons why Colombia entered the war on the side of the Allies.

U-516 continued to prowl the area for what appeared to be easy pickings. The submarine next torpedoed unescorted U.S. tanker Elizabeth Kellogg (5,189 tons), Master Norman T. Henderson and owned by Spencer, Kellogg & Sons of New York, in her port side amidships near 11°10ˈN, 80°42ˈW, at 0935 on 23 November. Elizabeth Kellogg steamed en route from Curaçao in the Netherlands West Indies to Puerto Barrios, Guatemala, and she caught fire from the bridge to the poop deck, and the crew abandoned ship. The after magazine exploded after six hours and although tug Favorite (IX-45) and several escort vessels made for the area, the ship sank before they could reach the scene of the action and salvage her. Army tanker Y-10 and submarine chaser SC-1017 rescued the 38 survivors the following day, but ten men died in the attack.

American Liberty ship Melville E. Stone (7,176 tons), Master Lawrence J. Gallagher and owned by Norton Lilly & Co., of New York, meanwhile steamed independently with a cargo of copper, coffee, balsa, antimony, vanadium, and 294 bags of mail from Antofagasta, Chile, to New York. Tillessen torpedoed and sank Melville E. Stone about 100 miles northwest of Cristóbal, near 10°36ˈN, 80°19ˈW, at 0614 on the 24th. The sinking vessel’s suction capsized two of the lifeboats, but three boats got clear. The ship took Gallagher, four officers, seven crewmen, two men of her Armed Guard, and a passenger of the 88 men on board to the bottom with her, but submarine chasers SC-662 and SC-1023 rescued the 73 survivors.

Rear Adm. Harold C. Train, Commander, Panama Sea Frontier, directed Guadalcanal and Mission Bay to contribute their planes to the searches for the U-boat. Consequently, all of the available Avengers flew a “grueling” five and one half hour search, though despite the aerial reinforcements, Tillessen and U-516 eluded the searchers.

Escort ships Foss (DE-59) and George W. Ingram (DE-62) joined Guadalcanal, Mission Bay, and Welles for the rest of the voyage. The trip through the Windward Passage seemed especially precarious, in that rumors indicated that as many as six U-boats operated there at times (possibly only one or two boats duplicated in reports), and that one of the enemy submarines, while running on the surface, shot down a Mariner. Guadalcanal nonetheless reached Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk, Va., on 3 December. Mission Bay put in to Portsmouth, Va., where VC-36’s cross-country detachment rejoined the squadron on the 21st. Foss and George W. Ingram detached, and Welles continued to New York. While at Norfolk, a group of the ship’s company visited some of the ongoing colonial restoration projects at Williamsburg, Va.

Guadalcanal became the flagship of antisubmarine Task Group (TG) 21.12, and completed voyage repairs and last minute calibrations. Although VC-42 had been streamlined when it first boarded the carrier, the actual separation took place while the ship lay anchored at nearby Hampton Roads. When VC-42 went ashore, Lt. (j.g.) E. Richard King, MC, USNR, the squadron’s medical officer, Lt. (j.g.) Ian K. Lamberton, USNR, more than 100 men, and all of the equipment necessary to maintain the squadron’s planes remained on board Guadalcanal.

Early in the New Year on 3 January 1944, the ship’s squadrons switched and 30 officers, one civilian technician, and 52 men of VC-13, Lt. Cmdr. Adrian H. Perry in command, boarded from NAS Norfolk. The carrier also loaded the squadron’s nine FM-1 Wildcats and a dozen TBF-1C Avengers.

Planners intended for the ship’s planes to patrol the seas in a wide arc beyond the task group, and to search for U-boats using their radar and by visually scanning the waves. Whenever they detected a submarine, they were to radio the discovery to alert the carrier, and fire at the boat in order to mark her position. They could attack their prey with depth charges, rockets, and machine guns, and lead the group’s destroyers to the area, which would then attack with depth charges.

Many of the pilots practiced night bounce drills at fields ashore and checked out in actual night landings on board Charger (CVE-30) while she steamed in Chesapeake Bay. “But in Chesapeake Bay,” Gallery reflected for Naval Aviation News in April 1969, “you are landing on a steady deck, and if an erratic pilot can’t make it, you can just send him back to the beach. In the North Atlantic, you’ve got a heaving deck and the boys have to make it — or else. This makes a big difference.”

Guadalcanal set out on her maiden operational voyage with Alden (DD-211), John D. Edwards (DD-216), John D. Ford (DD-228), and Whipple (DD-217) from Norfolk on 5 January 1944 in search of enemy submarines in the North Atlantic along the U.S. to Gibraltar convoy route. The four destroyers had endured a harrowing ordeal fighting the Japanese in the Pacific (1941–42), and their crews consisted largely of well-seasoned veterans leavened with replacements.

An Avenger (BuNo. 24502), manned by Lt. (j.g.) James F. Schoby, USNR, ARM1c Almon R. Martin, and AMM2 James A. Lavender, launched for a patrol on 10 January. The plane carried six rockets under the wings, two 350-pound depth charges on Stations 10 and 12 in the bomb bay, and its machine gun ammunition. The Avenger thus weighed 16,700-pounds, and investigators later reported that the depth charge loading proved “unfavorable” and caused “tail heaviness.” Several TBFs had already flown successfully in that configuration, however, during the preceding days.

The weather turned foul and heavy swells pounded Guadalcanal, and the ship recalled her planes. The Avenger still held about 150 gallons of fuel as it attempted to land and three other planes were in the landing circle, so the air staff decided to make a concerted effort to land all of the aircraft before the storm reached Guadalcanal in all its fury.

The Avenger received two wave-offs, and approached the ramp again, though slightly to port and possibly a bit slow. As the plane settled toward the flight deck, Schoby applied full throttle and the Avenger’s nose lifted above the three-point attitude. The aircraft cleared the port side of the ship and when it reached about opposite the forward port stack, the left wing dropped, the plane rolled over on its back, the nose fell, and it went over the side into the water about 50 feet from the carrier, and sank in barely 40 seconds. Lavender swam to the surface and Whipple rescued him. Five minutes after the Avenger sank a depth charge exploded at an estimated depth of 250 feet. Whipple searched for an hour after picking up Lavender, but Schoby and Martin perished in the cold waters. Schoby had received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his part in sinking U-487 on 13 July 1943, while flying a TBF-1 Avenger with VC-13 from Core (CVE-13).

The ship continued to corkscrew through the heavy seas and two hours later another Avenger landed in the catwalk, and had to be jettisoned to clear the flight deck for a plane in the air that was running low on fuel. All of the crewmen of the two aircraft survived.

The Germans applied the principles of concentration of force and continued pressure during the Battle of the Atlantic by concentrating U‑boats against convoys. Adm. Karl Dönitz, who led the Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote (BdU) at German naval headquarters, deployed the submarines into various groups or “wolf packs” on patrol lines perpendicular to the main transatlantic shipping routes. To intercept a convoy, the first U‑boat utilized aerial reconnaissance or B‑Dienst reports (Beobächtung referred to observation and were signals used to cross‑fix Allied shipping). The German divided the Atlantic into a system of grids and directed their moves accordingly. The first boat would then shadow the convoy and radio the information back to headquarters, which would direct any nearby U‑boats to intercept the convoy. Dönitz exercised operational control over his deployed U-boats through Enigma-encrypted radio communications.

Allied cryptanalysts working with the Tenth Fleet intercepted and decrypted some of this message traffic, largely through HF/DF (High-frequency direction finding — nicknamed “Huff-Duff”). This was a system of fixing a U-boat’s position by detecting its radio transmissions, and the fleet alerted Guadalcanal.

“Early in the cruise,” Gallery afterward recalled, “we got a tip from the Tenth Fleet that a U-boat refueling rendezvous was slated to take place in our area on January 16 near sunset, 500 miles west of the Azores. We decided to keep well clear of that area with all our planes on deck until just before the rendezvous time. Then we put up eight TBMs to comb the area until sunset.”

Despite the overcast weather two of the Avengers, piloted by Ensigns Bert J. Hudson and William M. McLane, sighted a large submarine, U-544, Korvettenkapitän Willy Mattke in command, fueling a smaller one, U-516, about 40 miles from the ship, in the mid-Atlantic near 40°30ˈN, 37°20ˈW. U-544 also intended to transfer radar detection gear to the other boat. Hudson made a run from the starboard beam and fired several salvoes of rockets and dropped a pair of MK-47 depth charges between the two boats. U-516 sank slowly by the stern, while about 40 men abandoned U-544. McLane then dove for a similar rocket and depth charge attack, which blew men off the larger submarine’s deck and caused her to sink first with the bow at a 45° angle. The Americans assessed their attacks as “probably” sinking U-544, and damaging the refueling submarine, which, despite John D. Ford and Whipple’s determined search, most likely returned to port. The group correctly assessed their attack and sank U-544 with all hands — Mattke and 56 men. The redoubtable U-516 repaired the damage and lasted through the end of the war, however, when the boat surrendered at Loch Eriboll, Scotland, on 14 May 1945.

The planes began to run low on fuel as dusk approached but the crews turned and flew over the scene of the battle to view the carnage below. As the Avengers returned to Guadalcanal they used up a lot of time because of wave-offs for poor approaches in the gathering darkness. McLane landed his plane but a following TBF-1C crashed into the catwalk. Crewmen cleared the fouled flight deck by cutting off the tail of the damaged plane, but the sun set and the two remaining Avengers including Hudson’s were also running short of fuel. Some of the aviators reported what they believed to be a third submarine in the area, but Gallery grew worried about the chances of survival for his fellow pilots and ordered Guadalcanal to turn on her lights.

“You don’t like to show bright lights when you think there are U-boats breathing you’re your neck,” the captain later explained. “But in this case, we had no choice. To have any chance of getting our boys aboard, we had to turn on the lights. You might as well go for broke in such a spot, so we lit up like a saloon on a Saturday night.”

Nonetheless, the rapidly deteriorating conditions gave the other pilots the “jitters.” Hudson gamely landed but went through the barriers and over the port side. Gallery then ordered the other ships to turn on their searchlights, and the last Avenger splashed into the water for an emergency landing while silhouetted in the searchlight beam of one of the escorting ships. All six crewmen of the last two Avengers were rescued, though both planes disappeared beneath the waves. The ship doused her lights and sped from the area to throw off any possible U-boat attempting to set up for an attack run.

“In a spot like that you just have to turn them on,” Gallery justified his difficult decision concerning the lights. “If you get torpedoed and lose your ship — that’s very bad luck. But if you don’t turn them on and lose your fliers, you probably won’t sleep well the rest of your life. And you won’t deserve to.”

In addition to risking the ship, the victory against the U-boats might also have been a Pyrrhic one because of the accidents and the delays in clearing the deck. The captain thus spent the remainder of the voyage relentlessly drilling the crash crew each day in clearing a fouled deck. He directed the men to trundle the damaged Avenger that went into the catwalk out, and then shove the worn plane over the edge of the deck again. He then timed them with his stop watch until they could clear the wreckage in under four minutes.

A Wildcat, Lt. (j.g.) Wanton, flew a patrol several days later but the line to the external fuel became fouled and the plane ran low on fuel and attempted to return to the ship. The pilot tried to drop the fuel tank but it hung up and when he radioed the carrier about whether to ditch or land, the air staff decided to bring him in. The landing shook the tank loose and it struck the flight deck and burst into flame. One of the escorts feared the worst and closed the ship, but the crash crew extinguished the flames, and Wanton emerged from the conflagration with some 1st and 2nd degree burns.

An Avenger (BuNo 47972), Lt. (j.g.) Bert M. Beattie, USNR, ARM2c Dale C. Wheaton, and ARM2c Hugh W. Wilson, launched for a patrol on 20 January. The crew apparently got lost and their radio receiver failed, and the ship last detected the plane on the radar screen heading for the Azores. Investigators later surmised that after the radio failed, the pilot may have decided that he could more easily locate land than find the ship and he deliberately attempted to land in the water as the plane’s fuel ran out and darkness fell. Locals sighted an aircraft off the northwest coast of Flores that evening, and observed three men struggling in the surf for a couple of hours before being carried out to sea. The islanders discovered a life raft from the Avenger, not inflated, and recovered Wheaton’s body, who floated nearby. Guadalcanal adjudged Beattie and his gunner, Wilson, missing. Gallery reluctantly limited the planes to daylight flights for the remainder of the war patrol, despite the odds against finding any U-boats if they only surfaced at night.

“We did a lot of flying but saw no more U-boats,” he elaborated. “It was quite obvious that at this stage of the Battle of the Atlantic, daylight flying was almost a waste of time — except that it did keep the U-boats down until dark. I determined to have a shot at night operations next cruise.”

The ships moored and replenished at Casablanca, Morocco (26–29 January 1944), where some of the men traveled to Rabat and enjoyed the pageantry of a Moroccan military parade that passed in review of Sultan Mohammed V, and then headed back for Norfolk and repairs. They searched unsuccessfully for U-boats during their voyage and returned on 16 February. Guadalcanal and VC-13 made the cruise at a high price, as the squadron lost two pilots, three aircrewmen, and six Avengers. Furthermore, when Guadalcanal anchored at Bermuda for seven hours, she put ashore two Wildcats that had sustained serious damage. The carrier then detached her escorts for other duties elsewhere.

Before they sailed for their next war patrol, Gallery shared his thoughts in terms of the flying schedule with Lt. Cmdr. Richard K. Gould, who led VC-58, the squadron that was to embark, and Lt. Jarvis R. Jennings, the ship’s new landing signal officer. The captain proposed to start round-the-clock flight operations as soon as they experienced a “good moon and a reasonable sea.” Navy meteorologists predicted a full moon during the first couple of days out to enable the pilots to take off and land in moonlight, and Gallery surmised that as the moon shifted through its phases, the men would adjust to the darkness. “If it turned out they couldn’t — we would call it off,” he later reflected, “We would use whatever deck lights we found to be necessary.”

The Avengers were equipped with radar, but the crews usually needed to visually confirm their targets as well. Some of the men practiced dropping flares to illuminate their attacks, but the glare often blinded them, and thus their reliance on moonlight.

Guadalcanal embarked nine FM-2 Wildcats, three TBF-1Cs, and nine Eastern TBM-1C Avengers of VC-58 and set out from NOB Norfolk on her second wartime cruise (7 March–26 April 1944). Cmdr. Frederick S. Hall, Commander, Escort Division 4, led Forrest (DD-461), Chatelain (DE-149), Flaherty (DE-135), Pillsbury (DE-133), and Pope (DE-134) as they screened the carrier while they trained together and hunted for U-boats through the 11th, and then (11–27 March) sailed to Casablanca. The weather failed to cooperate, however, and overcast skies often blocked the expected moonlight, and rough seas otherwise pounded the ship. Guadalcanal launched aircraft from dawn to dusk in areas in which Tenth Fleet intelligence analysts believed that enemy submarines lurked, but without success. Planes dropped sonobuoys that detected an apparent U-boat on the 22nd, but despite attacking the submarine, she got away.

Some of Guadalcanal’s shore party witnessed a French military parade, and then enjoyed themselves at a beer party. The task group stood out of that port on 30 March 1944 with a convoy bound for the United States. The carrier held boxing matches in an improvised ring and musical shows in the hangar deck for recreation, and Cmdr. Monat performed a skit in which crewmen captured Adolf Hitler, satirically played by the doctor.

Scouring the waters around the convoy northwest of Madeira on 8 April 1944, one of the group’s lookouts sighted an oil slick, and Pope left the formation to investigate. The ship failed to detect the enemy but a full moon, clear sky, and calm sea enabled Guadalcanal to send four heavily armed Avengers aloft into the night for the first time during the cruise. “Although we tried to be matter of fact about it,” Galley recalled, “all of us had stomachs full of butterflies.” One of the Avenger pilots reported sighting a U-boat on the surface, but radio failure delayed his report until he returned to the ship. Guadalcanal launched another couple of Avengers to fly over that area.

Just 27 minutes after midnight planes discovered on radar and then spotted visually German Type IXC submarine U-515, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Werner Henke, a holder of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, and closed in for the kill. An Avenger flew “down moon” and dropped depth charges across the submarine. The attack failed to damage U-515, and the aircraft circled the U-boat as Henke temporarily escaped.

Avengers continued to search for the German submarine and dropped sonobuoys, but initially failed to detect her and then regained contact. The U-boat could only stay down so long and Henke brought her to the surface more than once. Three FM-2s flown by Lt. (j.g.) Charles D. Hardesty Jr., Lt. (j.g.) William F. Pattison, and Ens. Ellis R. Taylor attacked the submarine, along with a TBM-1C, manned by Lt. Helmuth E. Hoerner, ACRM Richard T. Woodson, and AOM2c Raymond E. von Spreechen, USNR; and a TBF-1C, Lt. Douglas W. Brooks, AOM2c Leland F. Stone, and ARM3c Edward Browning Jr. The planes made several well-coordinated attacks on the intruder with rockets and depth charges throughout the night, and with Chatelain, Flaherty, Pillsbury, and Pope, scoured the area as well.

The Germans twisted and turned as they attempted to lose the attackers, and Gallery acknowledged that Henke “knew his business.” The U-boat went deep, released decoys, and even released oil and junk, but the U-boat’s air turned foul and her batteries dropped in their charges. Pope gained another sound contact the following day on Easter Sunday, 9 April, and made a class “A” attack run. Bubbles rose to the surface as U-515 lost depth control and at 1510 broke through the waves amid the waiting ships, which immediately devastated her by point blank rocket and gunfire.

As Wildcats strafed U-515, Henke ordered abandon ship and the submarine went to the bottom, taking 16 men with her, near 34°35ˈN, 19°18ˈW. The Americans captured Henke and the other 43 survivors. U-515 had set out on her seventh war patrol from German-occupied Lorient, France, barely a week before on 30 March, and Guadalcanal and her consorts had thrust into a U-boat refueling area. Undaunted, Henke was shot and killed while attempting to escape from the interrogation center at Fort Hunt, Va., on 15 June, most likely in a suicide attempt to avoid extradition to the United Kingdom to stand trial as a war criminal.

Again on the night of 10 April 1944 the task group caught Type IXC boat U-68, Oberleutnant zur See Albert Lauzemis, on the surface in broad moonlight, about 300 miles south of the Azores and 60 miles from the battle with U-515, near 33°24ˈN, 18°59ˈW. Guadalcanal detected U-68 on her radar at about 0200, and aircraft picked up U-68 during the battle against U-515 and made two attacks, the second run after she submerged. Poor visibility impeded their attacks and determining the damage they inflicted, but the pilots spotted a bright light glowing under or on the surface. The task group made for the area and Guadalcanal launched more aircraft.

Plane F-4, an FM-2, Lt. Gould; TBF-1C, Lt. (j.g.) H. Dale Orcutt, USNR, ARM2c Paul W. Deaver, USNR, and AMM3c R.P. Johnston, USNR; TBF-1C, Lt. (j.g.) Eugene E. Wallace, USNR, AOM2c Robert I. Gregory, USNR, and ARM3c Chester R. Boyce, USNR; TBM-1C, Lt. Samuel G. Parsons, USNR, ARM3c Donald F. Shockley, USNR, and AOM3c Russell C. Middleton, USNR; and the TBM-1C manned by Hoerner, Woodson, and von Spreechen, attacked from the dark western sky.

U-68 surfaced again and shot “heavy” antiaircraft fire at her tormentors. Gould’s F-4 and T-22 and T-24, two of the Avengers, dropped depth charges and fired rockets at the submarine. She attempted to submerge and escape but a terrific underwater explosion erupted air bubbles, debris, oil, battery acid, torpedo air flasks, and several initial survivors swimming to the surface as she sank with Lauzemis and 55 of his men. Only a single crewman, Hans Kastrup, survived the attack to be taken prisoner, however, and the Germans posthumously promoted Lauzemis to a Kapitänleutnant. Following the war, Kastrup remembered that the Americans stood by to rescue any survivors and sent Gallery an annual Easter card. The group detected U-515 and U-68 at night, and in both instances sank the boats shortly after daybreak. Hall received the Bronze Star for helping to direct the combined attacks which resulted in the sinking of U-515, as did Lt. Cmdr. George W. Cassleman, USNR, for his “meritorious service” while commanding Pillsbury during the battle.

“No one knows better than I that we had a couple of very lucky breaks,” Gallery afterward pondered to Naval Aviation News. “One of them was getting two kills right off the bat. Nothing can give an iffy project a bigger shot in the arm and cure the jitters quicker than immediate spectacular success.”

“The most impressive feature of this cruise was that 2,100 hours of intense daylight operations accomplished nothing,” he observed in his After Action Report, “whereas 200 hrs of night flying resulted in two kills.”

Guadalcanal experienced problems with her regular shielded deck lights during the voyage, which Gallery succinctly described as “useless.” The crew improvised and used as much light as they considered necessary, whether they could shield it or not.

“When there was no moon we lit up like Broadway during landing operations,” Gallery explained. “Had we been torpedoed, I’m afraid I might have had trouble justifying this. But this is what we military men smugly refer to as a calculated risk, after we get away with it!”

The task group anchored at Horta at Fayal in the Azores on the 17th, where Guadalcanal refueled from British corvette Vervain (K.190), T. Lt. Robert A. Howell, RNVR, in command. Despite the light issue the Allied convoy arrived safely in Virginian waters on 26 April 1944. Guadalcanal detached the escorts, unloaded the squadron ashore at NAS Norfolk, and completed voyage repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard.

Almost concurrently with these battles, an event took place in the Solomon Islands that gave the ship added reason to be proud of her name. On 4 April 1944, a group of the islanders presented a plaque to the Navy for Guadalcanal as a token of their gratitude for the service’s part in liberating them from the Japanese. The hand-crafted plaque of Ivatu, a sandalwood tree, held a nautilus shell as its centerpiece. Vice Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, Commander Aircraft, South Pacific Force, accepted the plaque from British Resident Commissioner of the Solomon Islands Protectorate William S. Marchant, and forwarded it to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. The Secretary died on 28 April, and in June the plaque finally made its way to Guadalcanal, and from that day forward the gift adorned the bulkhead in her hangar deck.

As a part of the ongoing intelligence war, capturing a U-boat opened the possibility of gaining valuable intelligence data, especially concerning enemy signal codes. The British had captured codes and machines from U-boats and ships more than once, and their intelligence hauls had contributed greatly to Allied successes. In addition, capturing a U-boat would net a wealth of other information, including details about their design and the torpedo guidance systems.

Gallery therefore directed each ship in the task group to prepare a plan to seize, board, and tow an enemy submarine. The boarding parties began their training in deadly earnest, and Gallery visited the Tenth Fleet’s F-21, the U-boat tracking room. There, he spoke to Cmdr. Kenneth A. Knowles, who headed the Atlantic Section, Combat Intelligence Division, of the Headquarters of the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. Knowles had expanded and developed the initial antisubmarine section and later organized and led the division. The determined officer evaluated enemy submarine strength, dispositions, capabilities, and intentions. Knowles later received the Legion of Merit for these services, and because his estimates proved of “incalculable values and assistance to the Naval High Command and in direct support of operations against the enemy in the Atlantic.” Knowles “carried out his duties in a manner characterized by thorough knowledge, loyalty, perseverance, and zeal, thereby greatly contributing to a clear understanding of the enemy situation in the Atlantic.”

Knowles and his team tracked a U-boat from when she cast off her mooring lines at German-occupied Brest, France, on 16 March 1944 and as she worked her way southward to African waters. The Americans did not identify the submarine, but from the available information Knowles surmised that she was an older boat with a normal patrol of about three months, which meant that Guadalcanal and her group would have to capture the submarine before she turned for home by the end of May.

Unbeknownst to the trackers, their prey consisted of Type IXC submarine U-505, Oberleutnant zur See Harald Lange. Commissioned on 26 August 1941, at Deutsche Werft AG, Hamburg, Germany, Korvettenkapitän Axel-Olaf Loewe in command, the boat’s guest book included the script “Wir Fahren Gegen England” (“We sail against England”). U-505 set out on 11 patrols (19 January 1942–2 January 1944), during which the submarine made good on her claim and sank eight ships totaling 45,005 tons. Three of the vessels were American merchantman: West Irmo (5,775 tons) of the American-West African Line, Inc., of New York on 3 April 1942, Sea Thrush (5,477 tons) of Shepard Steamship Co., of Boston, Mass., on 28 June of that year, and Liberty ship Thomas McKean (MC Hull No. 301, 7,191 tons) of Calmar Steamship Co., of New York on 29 June 1942. In addition, two British, one Colombian, one Dutch, and one Norwegian ship fell victim to the U-boat.

Allied aircraft attacked and slightly damaged the submarine on 18 April 1942. On 10 November of that year, a British Lockheed Hudson (Ser. No. V9253), F/S Ronald R. Sillcock, RAAF, No. 53 Squadron, dove out of a low cloud and surprised U-505 southeast of Trinidad. The plane dropped four depth charges, one of which scored a direct hit, and strafed the boat, seriously wounding a warrant officer and a lookout. The flying debris from the depth charge’s explosion also destroyed the Hudson, however, killing Sillcock, SN1c H.L. Brew, USN, Sgt. P.G. Nelson, RNZAF, Sgt. T.R. Millar, RAF, and Sgt. W. Skinner, RAF. U-505 abandoned her patrol and came about for repairs in Lorient, transferring her casualties to U-462 en route.

The submarine returned to sea but a trio of British destroyers took advantage of a leaking external fuel tank on board the boat that aided their sound tracking and determinedly sought her during a 36-hour duel on 8 July 1943. The Germans nonetheless escaped and on the 13th reached safety at Lorient. U-505 attacked Allied ships during another patrol on 24 October 1943, but an escort depth charged the boat and Kapitänleutnant Peter Zschech, her second commanding officer, committed suicide during the battle. Oberleutnant Paul Meyer temporarily assumed command, until Lange relieved him on 8 November 1943.

U-505 slipped out of Brest with little fanfare for her 12th patrol late on the night of 16 March, crossed the Bay of Biscay, and turned southward toward the waters off Monrovia, Liberia. Enhanced Allied countermeasures, and in particular growing air power, compelled the Germans to deploy their U-boats away from watchful eyes from above, and the submarines searched for their victims at increasing distances from German-occupied Europe.

“They say that provisions have to last for a total of 17 weeks,” one of the U-boat’s crewman logged, possibly Oberfunkmaat (SM1c) Gottfried Fischer, “even though we only took on provisions (including fresh groceries) for 14 weeks. That’s how it is being a poor U-Boots-Schwein, as they call us.” The boat’s wireless caught part of the Wehrmacht’s situation report on 15 April, which announced an Allied air raid on central Germany. “I hope everything is all right back home,” the worried sailor reflected in his log.

“We’ve reached our area of operations,” the man added on 25 April. It took us 5 weeks to get here. The age of the boat is telling again. The door on one of the torpedo tubes does not close properly.” The submarine’s echo sounder also broke down at one point, but the sweltering West African weather posed more of a problem as it wore down the crew.

“For a few days now we have been “enjoying” the tropical heat. Everybody is perspiring freely. Even in the bunks it takes only a few minutes until everything is soaked wet. From sweat, mind you! Water temperature is 29° C [84.2° F]. The temperature inside the boat is 35–40° C [95–104° F]. And this is only the beginning. The heat is so intense that I sometimes wish I could shed my skin.” By the 30th, the heat compelled the man to avoid all unnecessary movement. The sailor journaled that the crew enjoyed a “nice diversion” when a pair of sharks frolicked around the boat’s 20 millimeter gun, and Lange announced over the intercom that men who wished to do so could watch the animals caper.

Lange took U-505 to just outside the entrance to Monrovia, where he looked for Allied ships, but did not spot any vessels in the harbor that he considered worth risking attacking. From there, the submarine operated along the West African coast, usually submerging during the day in order to avoid Allied radar or planes, and surfacing at times during the night to prowl under cover of darkness. The German lookouts spotted several steamers during their patrol but the boat failed to maneuver into position to attack any, usually because of the speed of the intended victims as they outdistanced pursuit. In one instance she intercepted a brightly lit steamer, only to discover that she sailed under neutral Portuguese registry, and on two other occasions encountered neutral Spanish vessels.

In the meantime on 12 May, nine FM-2s and 12 TBM-1Cs of VC-8, Lt. Norman D. Hodson in command, were loaded on board Guadalcanal at Norfolk. The squadron was established on 9 September 1943 at NAS Seattle, Wash., trained on the west coast, and embarked in Solomons (CVE-67) as she steamed from San Diego to Norfolk (30 January–16 February). VC-8 fortuitously completed an antisubmarine course at NAS Quonset Point later that month, returned to Norfolk for additional training and maintenance, and then (16 April–5 May) carried out rocket training at NAAS Manteo, N.C.

After accomplishing repairs, Guadalcanal and her escorts set out as TG 22.3 from Hampton Roads again for the carrier’s third war patrol on 15 May 1944. Cmdr. Hall led the screen — Chatelain, Lt. Cmdr. Dudley S. Knox, USNR, in command, Flaherty, Lt. Cmdr. Means Johnston Jr., Jenks (DE-665), Lt. Cmdr. Julius F. Way, Pillsbury, Lt. Cmdr. Cassleman, and Pope, Lt. Cmdr. Edwin H. Headland.

The Germans continued to unknowingly aid the Allies by transmitting their signals, which the Allies intercepted and decrypted whenever possible. “Sent our situation report by wireless this morning at 0100h,” the German sailor, likely Fischer, noted in his journal on 15 May. “The signal was received well with good strength. Not bad, given the distance between the African west coast and Germany. And considering how small our transmitter is.” The writer reflected proudly on his achievement, unaware that such transmissions enabled the Americans to track the submarine down via Huff-Duff.

Guadalcanal searched for U-505 and the following day, an Avenger, Ens. William M. Allison, USNR, ARM3c Robert E. Hatfield, USNR, and AOM3c Calvin G. Sharp, launched for a routine antisubmarine patrol. The plane ran out of one of its fuel tanks at 1,200 feet altitude and the engine failed to catch until the pilot descended to 500 feet. In the meantime, his crew jumped without orders. Allison circled his men in the water until an escort picked up Hatfield, but Sharp’s parachute evidently failed to open and he was never seen again. The pilot landed the Avenger safely.

Whenever possible, U-boats surfaced after dusk to recharge their batteries, but as U-505 continued to patrol she experienced multiple air alarms at night that abbreviated the time for charging the batteries. In addition, the submarine gradually ran low on fuel, and Lange turned her homeward bound on 23 May. The Americans and Germans may have just missed each other that day as U-505’s threat receiver detected a contact at about 0400. The boat submerged and then surfaced about an hour and a half later, but detected a radar emission and dove again, and gained two acoustic contacts. “Probably a Hunter-Killer Group made up of destroyers and patrol craft,” the German noted. “Periscope depth. Propeller noise faded after one hour. Continued transit.”

On 2 June 1944 the captain decided to stay on the surface longer than might otherwise be thought prudent in order to attempt to recharge the batteries. U-505 evaded discovery but the effort failed to completely recharge the batteries, however, and she thus continued to operate at a disadvantage because of low electricity.

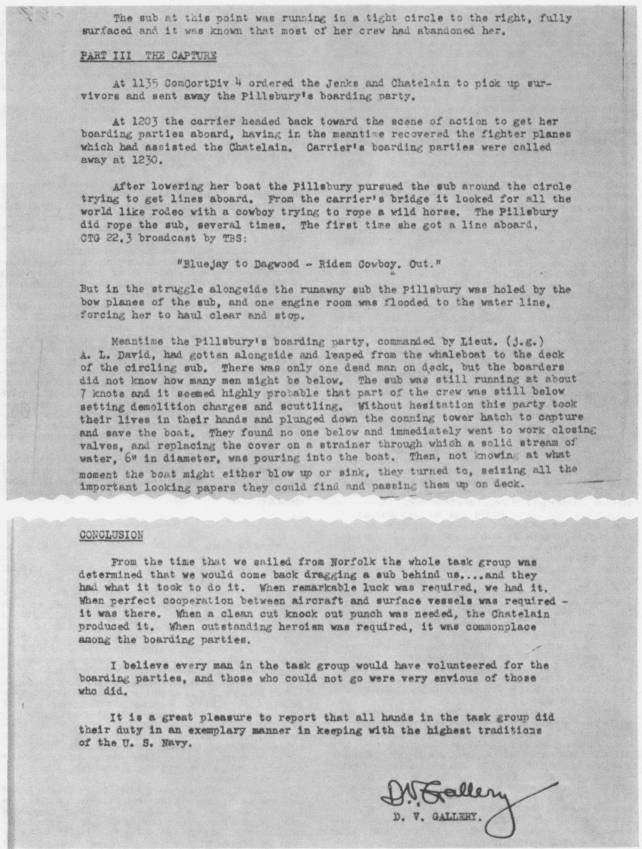

Guadalcanal diligently searched without successfully finding and attacking U-505 -- or any other submarines -- and on 4 June 1944, Gallery decided to swing the task force about and head for the African coast to refuel. “We hunted for this fellow about four or five days and nights,” Gallery later recalled, “had numerous indications that a submarine was nearby, such as disappearing radar contacts, noisy sonar buoys, TAG bearings, but we never did sight this fellow and we were finally about to give up the hunt. As a matter of fact, for all practical purposes we had given it up and were on our way to Casablanca but were keeping fighter planes in the air to serve as escort and also on the outside chance we might still find the fellow…”

That morning, Lange decided to chart a course closer to the Cape Verde Islands in order to shorten the return journey, and the submarine ran slowly northward submerged. Ten minutes after the U.S. task group reversed course, Chatelain’s sonar detected U-505 about 800 yards away on her starboard bow off Cabo Blanco [Ras Nouadhibou], Río de Oro, Spanish Sahara [Western Sahara], near 21°30ˈN, 19°20ˈW, at 1109. The 4th of June blossomed a clear day.

“There wasn’t a wave in the ocean,” SM2c Donald L. Carter, a signalman on board Guadalcanal, recalled afterward. “It was calm, and the Chatelain came over the radio; it says we have a sub contact, and we’re getting ready to attack. Then all hell broke loose.”

Within a minute, Chatelain, having made the sound contact and in accordance with the group’s doctrine and without further orders from Gallery, became the attacking ship, and Jenks and Pillsbury, the two nearest vessels, closed to assist her. Guadalcanal, Flaherty, and Pope opened the range from the contact. As Chatelain’s report reached the carrier’s Combat Information Center (CIC), she vectored F-1 and F-7, a pair of Wildcats just completing a search mission, over Chatelain. The ships and aircraft of the group guarded the same radio frequency, and the Wildcat pilots had already heard the radio message and turned toward the battle. As the planes flew over the U-boat they saw her running submerged just below the surface.

Chatelain loosed a hedgehog (forward-throwing antisubmarine projectile) attack that missed the U-boat. The Germans fired a G7es Zaunkönig (Wren) acoustic torpedo that also missed, and then came about, temporarily throwing Chatelain off the scent. The Wildcats spotted the enemy’s ruse, however, and alerted Chatelain to the ploy, recommended that the ship come about, and then steered her toward the submarine.

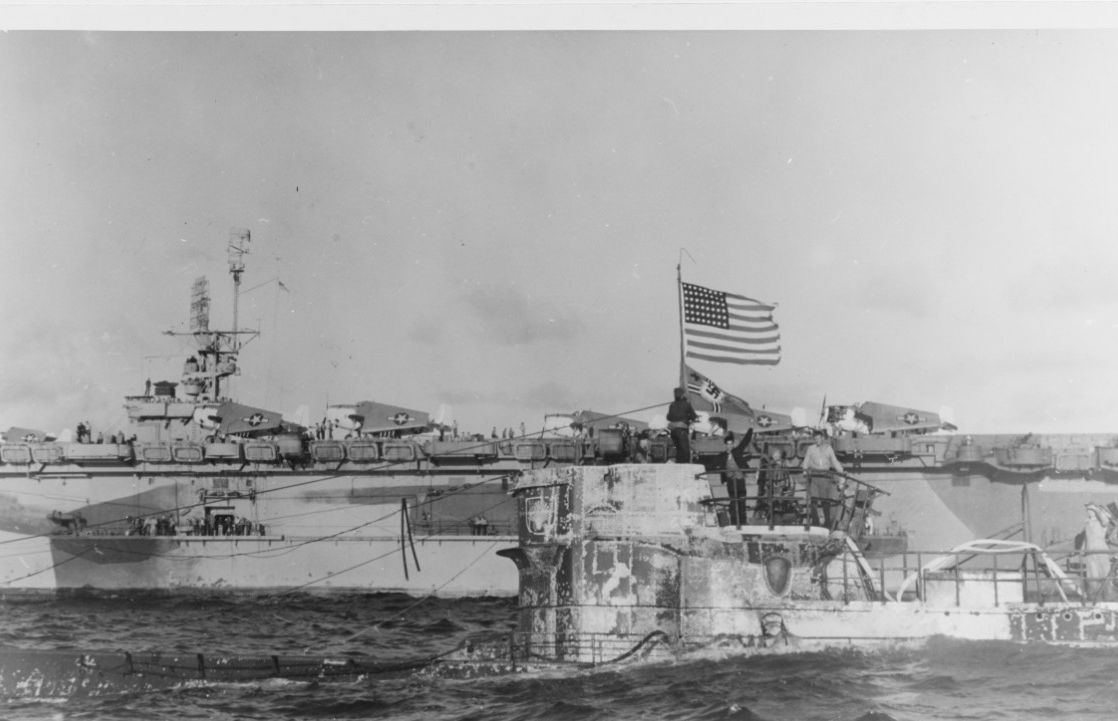

The escort detected U-505 with her sound gear again and, guided in for a more accurate drop by the circling fighters from Guadalcanal, soon made a second depth charge attack, firing a full pattern. This pattern blasted a hole in the outer hull of the submarine, which shuddered violently and rolled on her beam ends. The lights went out, water began pouring in, and the boat plummeted deeper into the depths of the Atlantic. Shouts of panic from the conning tower led Lange to blow his tanks and surface, barely 700 yards from Chatelain. The attackers sprayed the surfaced submarine with 20 millimeter and 40 millimeter gunfire, as well as a few 3-inch high explosive rounds — instead of armor piercing. F-1 and F-7 strafed the submarine with .50-caliber machine guns, killing Oberfunkmaat Fischer.

Some of the Germans bravely attempted to man their guns in the unequal battle but the volume of fire tore into them and a round struck Lange and he temporarily lost consciousness, though not before ordering his men to scuttle the U-boat. Many of the crewmen dove over the side, while others prepared to set demolition charges and open valves and watertight doors. The Americans continued to blast away, however, and most of the remaining Germans, assuming their submarine to be sinking, also abandoned ship. As the men scrambled to survive, most of them forgot to open all of the U-boat’s vents to sink her.

Cmdr. Hall issued the stirring order, “Cease firing. Away boarding parties.” Chatelain, Jenks, and Pillsbury all lowered boats into the water, and then Hall ordered the first two ships to stop and pick up survivors. Hall directed Pillsbury to dispatch her boarding party to seize the U-boat. Lt. (j.g.) Albert L. David, Pillsbury’s assistant engineering and electrical officer, led the boarding party of eight enlisted men: MoMMC George W. Jacobson Jr., USNR, MoMM1c Zenon B. Lukosius, GM1c Chester A. Mocarski, USNR, SM2c Gordon F. Hohne, USNR, BM2c Wayne M. Pickles Jr., EM2c William R. Riendeau, TM3c Arthur W. Knispel, and RM3c Stanley E. Wdowiak. In addition, Coxswain Philip N. Trusheim, SN1c James E. Beaver Jr., USNR, and MoMM3c Robert R. Jenkins, USNR, manned the whaleboat.

U-505 ran at about ten knots with her rudder jammed hard right and in just about full surface trim. David’s boat chased the submarine and cut inside the circle to catch her, and then he and his boarders leaped onto the slowly circling submarine and found her abandoned. Some of the party believed, from the way that the U-boat continued to steam, that a few of the German crewmen still worked below, engaged in scuttling or destroying classified material.

Braving the unknown dangers below, David, Knispel, and Wdowiak, carrying hand grenades and M-1 Thompson submachine guns, dropped down into the conning tower hatch. They did not find the Germans they expected to face, but water poured into the submarine through a bilge strainer about eight inches in diameter, the cover of which the departing crew had knocked off, and through some of the vents. The boat was rapidly flooding. The three men realized that the submarine lay abandoned, and desperately began stopping the leaks, as their fellows climbed below and lent a hand. The boarders closed the vents, and Lukosius discovered the cover to the bilge strainer and secured it. In addition, the men began gathering important papers and books.

Fischer was the only German crewman who died in the battle, and the Americans captured the 59 survivors. The victors gave their prisoners new clothes, coffee, and cigarettes. “When we [the German prisoners] looked again,” Hans J. Decker, a machinist, recalled, “we were thunderstruck to see a large American ensign flying from the conning tower of U-505 and noticed a small whale boat standing by her. Not only had they captured us, but our boat as well!”

Cmdr. Earl Trosino, USNR, Guadalcanal’s chief engineer, led a larger salvage group on board, and they began the work of preparing U-505 to be taken in tow. The submarine lay low in the water as she rolled in the swells and in order to prevent water from washing down her conning tower, they reluctantly closed the hatch. “Those people down below wouldn’t have had any chance whatsoever to escape in case the sub had gotten away from us,” Gallery noted chillingly.

As Pillsbury attempted to lay alongside and get a tow-line on the submarine, she sent a message to the boarding and salvage parties to stop the boat’s engines. The Americans managed to stop her engines, but the stern of the submarine sank and it appeared as if she was going down after all, so they quickly threw the switches to full speed and her stern planes lifted. Pillsbury slipped alongside while U-505 circled and heaved a line at the submarine. Gallery observed the action from the carrier’s bridge and it reminded him of a cowboy attempting to rope a wild horse at a rodeo. “Ride ‘em cowboy!” he said over TBS (line-of-sight voice radio).

Pillsbury attempted to secure her line to U-505 but the two collided and the submarine’s bow planes ripped a gash in the escort’s side, flooding two main compartments. Pillsbury backed clear and sent a message to Guadalcanal that she did not believe that an escort could safely take the prize in tow. Guadalcanal thus maneuvered into position and ordered the men on board U-505 to stop her engines. When they did, the carrier backed her stern up against the submarine’s nose, and they made fast a 1¼-inch wire line and took her in tow.

The boarders ingeniously prepared the submarine for her tow. Trosino disconnected the boat’s diesels from her motors in order to allow the propellers to turn the shafts while she was under tow. Ens. Frederick L. Middaugh traced out U-505’s electric wiring and set the main switches for charging the batteries. Guadalcanal then took the boat under tow at high speed, thus turning the electric motors over, causing them to operate as generators and to recharge the batteries. These actions enabled the salvage parties to run the electric machinery in U-505, and to use the boat’s own pumps and air compressors to bring her up to full surface trim.

Guadalcanal recovered her planes and the task group chartered courses toward Dakar, Senegal, but fears of German spies in that West African port prompted the Navy to redirect the ships to Casablanca, and finally for Bermuda, with their priceless prize in tow. Fleet ocean tug Abnaki (ATF-96) rendezvoused with the task group on 7 June and Guadalcanal passed her tow to Abnaki. Oiler Kennebec (AO-36) also sailed to the scene and refueled some of the ships, and the group reached Bermuda on 19 June.

“I consider this capture to be proof for posterity of the versatility and courage of the present day American sailor,” Gallery proudly announced in a Navy press communiqué on 16 May 1945. “All ships in this task group were less than a year old and 80 per cent of the officers and men were serving in their first seagoing ship. All hands did their stuff like veteran sea dogs, and airplane mechanics became submarine experts in a hurry, when the chips were down. I’m sure John Paul Jones and his men were proud of these lads and of the day’s work when the U.S. colors went up on the U-505.”

For their daring and skillful teamwork in this remarkable capture, Guadalcanal and her escorts shared in a Presidential Unit Citation. Lt. (j.g.) David died from a heart attack at Norfolk on 17 September 1945, but posthumously received the Medal of Honor for his “vigorous part in the skillfully executed attack…Fully aware that the U-boat might momentarily sink or be blown up by exploding demolition and scuttling charges, he braved the added the danger of enemy gunfire to plunge through the conning tower hatch and, with his small party, exerted every effort to keep the ship afloat and to assist the succeeding and more fully equipped salvage parties in making the U-505 seaworthy for the long tow across the Atlantic to a U.S. port.”

Many of the other men involved in the battle also received awards and citations. Knispel and Wdowiak each received the Navy Cross for their “conspicuous heroism” in boarding the submarine, although there “was every reason to believe that” Germans still worked below “setting demolition charges and scuttling,” and that “there was the strong possibility that it would blow up or sink at any moment.” The other boarders each received the Silver Star — Hohne, Jacobson, Lukosius, Mocarski, Pickels, Riendeau, and Trusheim.

Gallery received the Navy Distinguished Service Medal for the daring exploit. Cmdr. Jesse G. Johnson, Guadalcanal’s executive officer, received the Bronze Star. Hall, Trosino, Cassleman, Lt. Richmond P. Burr, and Lt. Deward E. Hampton, USNR, were awarded the Legion of Merit. Lt. Philip F. Ruth, USNR, received a Commendation Ribbon for furnishing Gallery “with authentic and immediate information from CIC that assisted” in capturing the submarine.

Lt. (j.g.) M H. Schroeder, Ens. Middaugh, Chief Ship’s Clerk M.C. Keck, CPhoM C.V. Werila, BM1c J. Wright Jr., MM3c F.H. Venker, and Coxswain R.T. Sparks of Guadalcanal’s ship’s company were all awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

The men of VC-8 shared the laurels of victory and Lt. Hodson received the Bronze Star, while Lt. Wolffe W. Roberts, USNR, the squadron’s executive officer, and Ens. John W. Cadle Jr., USNR, were awarded Distinguished Flying Crosses. Adm. Royal E. Ingersoll, Commander, Atlantic Fleet (additionally designated the Second Fleet), signed Roberts and Cadle’s awards “in the name of the President of the United States” for their “outstanding courage and meritorious service,” but because of the crucial impact of the battle added, “the nature of which cannot be revealed at this time.”

The captors interned their captives at Bermuda and secretly kept U-505 there for some months, where they studied the intricacies of her design. The captured submarine proved to be of inestimable value to American intelligence, and her true fate remained a secret from the Germans until the end of the war. Naval intelligence and engineering officers investigated the prize in 1944–45, but the Germans in the meantime introduced more advanced Type XXI and Type XXIII diesel-electric submarines, which elicited greater interest in their design and development. Consequently, the Navy slated U-505 for disposal as a target for gunnery and torpedo practice.

Guadalcanal lay at Bermuda (19–20 June 1944), where the crew enjoyed a brief respite as they played volleyball on one of the elevators and baseball ashore, where Gallery hit a home run. Afterward, the ship held a swim call and the men cooled off in the Atlantic. The carrier then (20–22 June) steamed from Bermuda to NOB Norfolk, and spent only a brief time there before setting out again on patrol. After escorting convoys with TF 62 to the Mediterranean, Neunzer (DE-150) joined the task group. The ships departed Norfolk on 15 July and between then and 1 December made three largely uneventful antisubmarine cruises in the Western Atlantic.

Following training at Casco Bay, Maine, and Bermuda, the task group made their initial two search patrols for submarines in the Middle Atlantic, refueling in Bermuda. Neither of these patrols uncovered any U-boats, though during Guadalcanal’s fourth war patrol on 23 July 1944, TG 22.2 sonar operators made what they believed to be a positive submarine contact, but the U-boat, if such it was, escaped. The ship also attacked a radar contact that she suspected might be a surfaced submarine on 4 August, and on the 22nd aircraft did so on a sonobuoy contact, but both attacks ended without results. At one point during these cruises, Neunzer high-lined a patient over to the carrier, where Cmdr. Monat performed an emergency appendectomy on the man. Neunzer detached temporarily in late August and returned to New York. Guadalcanal spent the rest of the summer (29 August–12 September) undergoing alterations and voyage repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard. Following the yard work, the ship visited Baltimore, Md., for liberty and recreation (19–24 September).

The following day, nine FM-2s, nine TBM-1Cs, a pair of TBM-1Ds, and another Avenger of VC-69 were loaded on board Guadalcanal. The carrier stood down the channel from NOB Norfolk and rendezvoused with Chatelain, Flaherty, Neunzer, Pillsbury, and Pope, and the group searched for submarines in the North Atlantic (28 September–7 November 1944).

On 13 October 1944, planes detected a radar contact and attacked, but the contact faded. Aircraft dropped sonobouys that apparently discovered a U-boat on the 25th and unsuccessfully attacked the prowler. The group did not otherwise discover any U-boats, but ran through a very severe storm which damaged some of the ships. The foul weather battered the escorts and one huge swell rolled over the carrier’s stern. The ships broke off the patrol, refueled at Ponta Delgada in the Azores, and turned for home. Guadalcanal completed alterations and voyage repairs in dry dock at Norfolk Navy Yard (8–21 November), provisioned on the 25th, and then (26–30 November) paid a return visit to Baltimore. At one point during Guadalcanal’s time in port, actress Martha Scott visited the ship and graciously extended her tour to include the men convalescing in Sick Bay.

Nine FM-2s and six each TBM-3s and TBM-3Ds of VC-19 were hoisted on board Guadalcanal and she set sail with TG 22.7 on 1 December 1944 for training in the waters off Bermuda. The exercises included refresher landings for pilots of her new squadron, gunnery practice, and antisubmarine drills with submarine R-9 (SS-86).

Guadalcanal anchored in Port Royal Bay at Bermuda on 11 December 1944, and in company with Chatelain, Neunzer, and Pillsbury arrived at NAAS Mayport, Fla., on 15 December. Guadalcanal’s arrival marked the first time that a carrier used Mayport’s basin. The ship refueled and provisioned, and held an (early) New Year’s dance in her hangar deck in which the crew invited Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES) from the area for their dates. The ship then (18 December 1944–19 January 1945) stood out to sea and qualified 319 pilots during 2,349 landings while off Mayport.

Continuing her training exercises early in the New Year, Guadalcanal and her consorts made for Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (20 January–13 February 1945). The ship anchored in that U.S. enclave on the 23rd, and next (24 January–10 February) carried out sonar and torpedo exercises, ship casualty drills, and radar exercises between the planes of VC-19 (which flew ashore) and a “tame” submarine, as well as antisubmarine scenarios against the “enemy” boat. In addition, some men attended schools on the naval station. Rumors circulated that they undertook the training in preparation for deploying to the Pacific to fight the Japanese. Chatelain temporally departed from the group and stood by a merchant ship that had been rammed as the remaining ships turned their prows homeward and returned to NOB Norfolk, where VC-19 detached from Guadalcanal.

Guadalcanal, Chatelain, Flaherty, Frederick C. Davis (DE-136), Nuenzer, and Pillsbury formed TG 22.7 and headed to the Caribbean for more exercises in Cuban waters (26 February–14 March 1945— they began the training on the 7th). The carrier embarked three FM-2s, six TBM-1Cs, four TBM-3s, and six TBM-1Ds of VC-6. Pope joined the group later in the training problem.

After the short training cruise to the Caribbean, Guadalcanal steamed into Mayport for a tour of duty as a carrier qualification ship (15 March–22 August 1945). Naval Academy ensigns took a familiarization tour of her during this period, and after qualifying 1,467 pilots, Guadalcanal steamed to Lynnhaven Roads, Va. (26–28 August). There, an inspecting party from Fleet Air Norfolk and escort carrier Solomons boarded and held an annual military inspection and damage control problem on the 28th. The following day, a draft of 24 men transferred to Receiving Station Norfolk, representing the first group to leave the ship for discharge under the Navy’s discharge system as the end of the war approached. Guadalcanal next completed an overhaul in Norfolk Navy Yard (29 August–10 October), where, on 4 September, she was assigned to the Atlantic Inactive Fleet.

The veteran ship shifted to the Chief of Naval Air Training (12–16 October 1945), and the following day reported to Naval Air Training Bases at NAS Pensacola, Fla., where she qualified 14 pilots, carried out indoctrination cruises, and held general drills and gunnery exercises. The ship entertained visitors as she took part in her first Navy Day celebration on 27 October.

Rear Adm. Charles A. Pownall, Chief of Naval Air Training, presented the ship with her Presidential Unit Citation, signed by Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal for the President, on 9 November 1945. Guadalcanal recorded 22,985 day and night landings during her operational career (25 September 1943–16 November 1945), and, during her final year the ship qualified approximately 1,800 pilots.

On 9 February 1946, Guadalcanal reported to the Sixteenth Fleet, and was placed out of commission in reserve. The ship logged her final flight operations at 1017 that day when she launched five Vought F4U Corsairs for a flight to NAS Norfolk, having qualified the carrier’s final 11 pilots in 64 landings.

Guadalcanal was decommissioned at 1015 on 15 July 1946, and assigned to the Norfolk Group, Atlantic Reserve Fleet. The carrier shifted to the New York Group on 30 November 1949. She was reclassified to a utility aircraft carrier (CVU-60) on 12 June 1955, while still in reserve at New York. Guadalcanal was stricken from the Naval Register on 27 May 1958, and was sold for $140,769.89 for scrap to the Hugo Neu Corp., of Nassau Street in New York on 30 April 1959.

Guadalcanal received a Presidential Unit Citation and three battle stars for service in World War II.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Daniel V. Gallery Jr. | 25 September 1943 |

| Capt. Burnham C. McCaffree | 16 September 1944 |

| Capt. Shirley S. Miller | 8 August 1945 |

The Odyssey of U-505

In 1946, Guadalcanal’s former commanding officer told Father John I. Gallery, ChC, his brother and a Navy chaplain, about the plans to sink the submarine. Father Gallery called President Lenox R. Lohr of the Museum of Science and Industry at Chicago, Ill. Julius Rosenwald, a prominent Chicago businessman, had established the museum to showcase “industrial enlightenment” and public science education. The institution thus specialized in interactive exhibits, and Lohr promptly revealed ten-year plans to acquire and display a submarine, and began planning on acquiring U-505.

The people of Chicago raised $250,000 to help prepare the boat to be towed to their city and installed in the museum. U-505 accomplished her final voyage under tow from Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, N.H., to Chicago via the St. Lawrence Seaway/Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan (14 May–26 June 1954). She was then (13 August–3 September) moved into a floating drydock and laboriously shifted about 800 feet from the lake to the east end of the museum building.

Secretary of the Navy Charles S. Thomas presented the Navy’s Distinguished Civilian Service Award to Lohr, Robert Crown and Carl Stockholm, co-chairmen of the U-505 Committee, Ralph Bard, the committee’s honorary chairman, Seth Gooder, the engineer who directed the boat’s beaching and overland move, and to William V. Kahler of the committee on 24 September 1954.

A crowd of nearly 15,000 people gathered the following day on 25 September, as Flt. Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., delivered the dedication address. “As a permanent exhibit at the Museum,” Halsey said, “it will always remind the world that Americans pray for peace and hate to fight, but we believe in our way of life and are willing and capable of defending ourselves against any aggressors.” Radio and television star Arthur Godfrey acted as the master of ceremonies. The submarine became a war memorial and permanent exhibit, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1989.

U-505 braved the elements for nearly 50 years but her condition deteriorated, and the museum moved the boat into a new state-of-the-art underground, climate-controlled space to help preserve her. The process involved substantial preparation (1997–2004), and NORSAR Inc., a company that had experience in moving vessels, positioned U-505 on 18 sets of dollies with eight tires each, all of the dollies individually equipped with adjustable hydraulic rams to enable the movers to maneuver her weight over uneven surfaces. The workers moved the submarine about 1,000 feet into the exhibit area, a 75-by-300-foot, 42-foot deep pen, over several days in April 2004. The entire exhibit cost $35 million and immersed visitors into the dramatic capture of the submarine.