"Calmness, Courage, and Efficiency":

Remembering the Battle of Leyte Gulf

Battle of Leyte Gulf: Arming a Torpedo Squadron 51 (VT-51) TBM torpedo bomber on USS San Jacinto (CVL-30), 25 October 1944. Probably taken before the squadron's planes attacked the Japanese carrier force off Cape Engaño. The torpedo is a Mark XIII, fitted with a wooden stabilizer around its tail and drag ring around its nose (80-G-284708).

Contents

“I Have Returned”: Planning for the Invasion of the Philippines

“Strike, Repeat, Strike!”: In the Skies Over Sibuyan Sea

“Make All Ready for a Night Battle”: Last Clash of the Battleships in Surigao Strait

“Where is Task Force 34?”: Decision and Indecision off Cape Engaño

In Harm’s Way: The Battle off Samar

In the U.S. Navy’s history, few battles are as significant or as controversial as that of Leyte Gulf (23–26 October 1944). Among the largest naval battles ever fought,1 Leyte involved nearly 200,000 men and 282 ships fighting in four separate engagements across 100,000 square miles of ocean. It was exactly the sort of “decisive battle” that both the Allies and the Japanese had sought since the beginning of World War II, one that pitted the waning might of the Japanese Combined Fleet against the U.S. Third and Seventh fleets. Although the Japanese hoped that this battle would revive their flagging fortunes, in the end, it would be prove to be their navy’s death knell, leaving the Allies in command of the Pacific and well situated to recapture the remainder of the Philippines.

Beyond Leyte’s operational significance, it can be argued that no other battle fought during World War II encompassed as many facets of naval warfare nor, for that matter, the rich tableau of experiences and challenges that U.S. Navy sailors endured in service to their country during the conflict. This battle was a naval operation of an incomparable scale, the outcome of which turned on innumerable individual acts of heroism; a showcase for naval air power, which also featured the last engagement between battleships; and an unparalleled victory that came perilously close to becoming an unmitigated disaster. Even 75 years later, Leyte Gulf still has much it can teach us about planning and preparation, the evolving nature of warfare, decision-making under fire, and, above all, individual sacrifice.

“I Have Returned”: Planning for the Invasion of the Philippines

From its very inception, the invasion of the Philippines promised to be one of the most wide-ranging naval campaigns ever conducted by the U.S. Navy, one that would involve multiple fleets, raids on other Japanese-held islands, shore bombardments of enemy defenses, and, most importantly, the transportation and landing of Army troops onto the island of Leyte. Naturally, the planning that went into this undertaking was quite extensive, with Navy planners working hand-in-hand with their Army counterparts to develop a workable strategy for the upcoming invasion. The proposed undertaking was well-conceived, but, like all joint operations, it would require a high degree of cooperation and coordination among all forces involved, a task made all the more complicated by the fact that command of the naval forces would be divided between Admiral William Halsey (Third Fleet) and Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid (Seventh Fleet). While this would prove no obstacle to success initially, the divided command structure had the potential to complicate the operation, particularly if the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) decided to vigorously oppose the invasion.

Suffice to say, this is exactly what the IJN intended to do. Following the Combined Fleet’s disastrous showing at the Battle of Philippine Sea (19–20 June 1944),2 its leaders recognized that time and resources were running out to blunt the Allies’ momentum and prevent them from launching attacks against the Japanese Home Islands. Believing it necessary to force the U.S. Navy into a “decisive battle” but uncertain as to where it would strike next, they developed four separate contingency plans that corresponded to potential invasion routes the Allies might take.3 Collectively known as “Shō-Go” (“Operation Victory”), each plan called for the IJN to commit the bulk of its remaining fleet to the proposed engagement in the hopes of delivering a crippling blow to its enemies.

The IJN’s plan to defend the Philippines (Shō-1) initially involved three separate forces.4 The first, the Task Force Main Body consisting primarily of carriers under Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, would sortie from Japan and approach the Philippines from the north, stationing itself off the island of Luzon. Joined by Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima’s Second Striking Force, they would attempt to draw off the ships covering the Allied landings. With the landing ships now unprotected, Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s First Striking Force would easily be able to swoop in and destroy the landing craft, leaving the Allied troops stranded until a counter-invasion could be launched to wipe them out.5

As we shall see, Shō-1 underwent some crucial revisions once the Allied invasion of the Philippines actually materialized, but even in its earliest form, it can be viewed as a product of both strategic daring and sheer desperation. So much of the operation’s success rested on a number of different variables, not the least of which was whether or not Ozawa’s fleet could entice the U.S. Navy’s covering fleet to abandon the amphibious forces. While they publicly exuded confidence, those involved in the operation privately knew it was a desperate gambit, with Ozawa admitting to Allied interrogators after the war that he did “not have much confidence in being a lure, but there was no other way than to try.”6 Others were even more fatalistic, including Kurita. In the run-up to the battle, he asked his crew, “Would it not be a shame to have the fleet remain intact while our nation perishes?”7

Although the U.S. Navy had some intelligence concerning Japan’s plans for a “decisive battle,”8 those involved in the planning of the Philippines campaign did not anticipate “that major elements of the Japanese fleet will be involved in the present operation.”9 While this prediction proved to be woefully inaccurate,10 it cannot be said that they were ill-prepared to defend the landings in the event that a Japanese attack did materialize. Whereas most prior operations had only utilized a single fleet, the plan for Leyte Gulf called for the involvement of both the Third and the Seventh fleets. The latter, under the command of Vice Admiral Kinkaid would operate out of Leyte Gulf, conducting bombardments of Japanese shore defenses, ferrying General Douglas MacArthur’s troops ashore, and guarding the southern approach to the gulf through the Surigao Strait. Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet, on the other hand, would “cover and support forces of Southwest Pacific [i.e. the Seventh Fleet],” as well as destroy “enemy naval and air forces in or threatening the Philippines Area.” Crucially, Halsey’s orders also contained the important caveat that, “In case opportunity for destruction of major portions of the enemy fleet offers or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task.”11 This certainly got Halsey’s attention, as he subsequently wrote Nimitz, “My goal is the same as yours—to completely annihilate the Jap fleet if the opportunity offers.”12

Halsey’s enthusiastic reaction was very much in line with his overall command style and temperament. Known for aggressive tactics and bombastic pronouncements (upon hearing a Japanese broadcast that tauntingly asked, “Where is the American fleet?” the admiral told an aide, “Send them our latitude and longitude!”),13 Halsey was a commander very much in the mold of Horatio Nelson. In the months following Pearl Harbor, he had led a series of daring raids against Japanese-held islands, provided naval support for the famed Doolittle Raid, and commanded the Navy’s successful operations in the eastern Solomons. Feted by the American press and revered by those who served under him, Halsey was, arguably, the face of the Navy during World War II.

His counterpart, Kinkaid, was almost the polar opposite. Although Kinkaid had developed his own well-deserved reputation as a “fighting admiral,” he was considerably more cautious and personally reserved than Halsey, once remarking to a reporter, “Please don’t say I made any dramatic statements. You know I’m incapable of that.”14 As a commander, he tended to take a more group-oriented approach, trusting in the abilities of his subordinates and collaboration with others to accomplish the tasks at hand. It was for this reason that Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPOA), had chosen him to lead joint operations with the Army, first in the Aleutians in 1943 and then in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). The latter assignment placed him under Douglas A. MacArthur, the famed general who had led the defense of the Philippines in early 1942 and was now desperately seeking to return there. Despite the general’s rather mercurial temperament and his staff’s innate distrust of the Navy, Kinkaid developed a productive working relationship with them during their campaigns against the Admiralty Islands and western New Guinea.15

This strong relationship would pay dividends in planning upcoming invasion of the Philippines. Although planning for the operation had begun in July 1945, the decision in mid-September to move up the invasion from December to October gave Kinkaid and his staff only five weeks to come up with a workable plan. Thankfully, most of the principle staff involved were located at or near MacArthur’s headquarters in Hollandia, enabling them to resolve issues quickly and gain a greater understanding of all aspects of the operation. Indeed, the planning process was apparently so thorough that it impressed even Roger Keyes, former Royal Navy Admiral of the Fleet. Keyes, who was visiting Hollandia at the time, told Kinkaid, “I’ve been here for your briefings. I understand what is going on, I know your plan, and I think the plan is a good one and it will succeed.”16

As thorough as the planning process had been, there was one potential sticking point: the command structure. Since early in the war, Pacific operations had been divided into two separate theaters, with MacArthur in charge of the Southwest Pacific Area and Nimitz commanding the Pacific Ocean Area. Under this arrangement, the Seventh Fleet had been placed under MacArthur’s overall command (hence, its nickname “MacArthur’s Navy”), while Third/Fifth Fleet had been under Nimitz.17 Ideally, the two commands would have merged once operations converged in a single theater, but it is unlikely that either Nimitz or MacArthur would have suffered being made subordinate to the other.18 Thus, the divided command structure remained in place, even as the Allies prepared for what be the largest, most complicated amphibious operation since the landings at Normandy earlier that year.

In Halsey’s view, the divided command structure contributed to some of the problem subsequently experienced at Leyte. As he later argued, “If we had been under the same command, with a single system of operational control and intelligence, the Battle of Leyte Gulf might have been fought differently to a different result.”19 Kinkaid, on the other hand, contended that, “One head would not have been better than two in a case of this sort, where each of us had his mission, I thought, very clearly stated.”20 On this last point, the Kinkaid was arguably mistaken. Although some elements of the Third Fleet had been involved the planning process,21 Halsey and Nimitz’s involvement had been limited to a handful of planning sessions, largely attended by their representatives. Thus, it is not necessarily surprising the two came to have differing as perceptions as to what their respective missions were. Whereas Kinkaid and MacArthur believed that Third Fleet’s main priority was to provide cover for the landing operation, Halsey viewed his mission as being potentially much more offensively oriented.22

Complicating things further were the communications restrictions that MacArthur had imposed on Kinkaid. Perhaps fearful of ceding any authority, MacArthur forbade Kinkaid from communicating directly with Nimitz or Halsey directly and required all communications through a radio station on Manus. This would greatly complicate the already difficult task of coordinating the two fleets, as the radio station proved unable to cope with the sheer number of messages that would flow through it during the battle. Consequently, some very critical messages were not delivered until many hours after they had been sent, something that would significantly affect Halsey and Kinkaid’s decision-making.23

It must be emphasized that, at least for now, the divided command structure and communications barriers remained only potential complications for the Leyte operation, and that the invasion plan itself was quite strategically sound. Indeed, the opening stages of the Philippines invasion went about as smoothly for the Allies as could be hoped for. On 17 October, TG 77.2 (the Fire Support and Bombardment Group) under Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf approached Leyte from the east, conducting minesweeping and shore bombardment operations off the islands of Suluan, Homohon, and Dinagat in order to secure the entrance to the gulf.24 Three days later, on 20 October, Kinkaid, MacArthur, and the rest of Seventh Fleet entered the gulf and commenced the invasion of Leyte proper. Not content to watch the operation from afar, MacArthur waded ashore and famously proclaimed, “People of the Philippines! I have returned.”

Despite the grandiloquent certainty of this pronouncement, however, the general’s return was anything but assured at this point. Although the Navy’s strategic planning had already paid considerable dividends, it remained to be seen whether or not it would hold up under pressure, particularly once the Japanese put their own plans into effect. Once that occurred, the Third and Seventh fleets would be forced to contend with not only the Japanese Combined Fleet, but also their shore-based aircraft. It would be here, in the skies over the Philippines, that the opening stages of the Battle of Leyte would be won or lost.

“Strike, Repeat, Strike!”: In the Skies Over Sibuyan Sea

Since the beginning of World War II, aviation had redefined naval warfare, indelibly linking the struggle for supremacy at sea to supremacy in the air. This remained true even as naval actions in the Pacific shifted from carrier duels in open waters to support missions for land-based operations such as the invasion of the Philippines. Indeed, air power arguably became even more important at this stage in the war, for although the Japanese had sustained irreversible losses to their naval aircraft at the Battle of Philippine Sea, they still commanded significant shore-based air power that could be brought to bear against the Navy, particularly now that the action had moved from isolated atolls to large islands in closer proximity to the Japanese mainland.25 Consequently, any successful defense of the Leyte landings would depend just as much on the Navy’s ability to neutralize the Japanese aircraft as it did their ships. Fortunately, in contrast to their opponents, the Navy had both the air power and the trained personnel necessary to do just that.

One of the engagements most critical to the success of the Leyte campaign actually occurred in the weeks preceding the landings. In order to throw the Japanese off-balance and keep them guessing as to where the Allies would target next, Halsey and Third Fleet staged a series of raids against Okinawa, Formosa, and Luzon. These raids succeeded beyond all expectations, not only forcing the Japanese to partially activate Shō-1 and Shō-2 plans, but to also sortie their shore-based aircraft against Halsey’s forces. The ensuing air battles (11–16 October) absolutely decimated the Japanese air fleets, costing them an estimated 529 aircraft. Critically, at least some of these the aircraft were from Ozawa’s carrier force, leaving him with little over 110 aircraft in reserve for the Leyte operation.26 This, coupled with the loss of shore-based aircraft would leave the ships of the Japanese Combined Fleet with precious little air cover heading into the upcoming engagement.27 Captain Mitsuo Fuchida, air staff officer to the Commander in Chief Combined Fleet, later testified that this, essentially, doomed the Leyte operation from the start.28

One other important consequence of Halsey’s raids is that it threw the Japanese completely off-balance and delayed their response until it became clear that the Allies’ primary target was not Formosa or Luzon, but Leyte. It was only on 18 October that they finally initiated the Shō-1 plan in earnest and sortied their fleets in the hopes of catching the Third and Seventh fleets at unawares. Departing from Brunei on 22 October, Kurita’s First Striking Force (referred to as the “Center Force” in U.S. Navy documents) would proceed as planned to the Sibuyan Sea in the hopes of reaching Leyte Gulf by 25 October. Upon the recommendation of Fleet HQ, he would also detach a smaller force of seven ships (two battleships, one cruiser, and four destroyers) under Vice Admiral Shōji Nishimura (the “Southern Force”) to proceed through the Sulu and Mindanao seas with the aim of approaching Leyte Gulf from the south through the Surigao Strait. They would be followed shortly thereafter by Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima’s Second Strike Force, which had originally been slated to oversee the counter-landings at Leyte in the event of Shō-1’s success. Meanwhile, Ozawa’s Mobile Strike Force (the “Northern Force”) would proceed southwards from Japan in the hopes of luring away Halsey’s Third Fleet. If all went according to plan, the Center and Southern forces would meet in Leyte Gulf and overwhelm the landing ships of Seventh Fleet.29

Despite their best efforts, the Japanese quickly lost the element of surprise when U.S. submarines Darter (SS-227) and Dace (SS-247) espied the Center Force off Palawan on 23 October. Taking advantage of their good fortune, the two submarines launched their own surprise attack against the Japanese fleet, damaging cruiser Takao and sinking heavy cruisers Maya and Atago, Kurita’s flagship. Humiliatingly, the admiral would be forced to spend at least part of the engagement (later dubbed the “Battle of Palawan Passage”) treading water until he could be rescued.30

As all of this was occurring, Halsey was busy preparing his own warm welcome. Upon receiving word that the Center Force had entered the Sibuyan Sea on the morning of 24 October, he ordered his aircraft to launch at 0833 with the admonition, “Strike! Repeat: strike!”31 Over the course of the day, they did just that, mercilessly pounding the Japanese Center Force with bombs and torpedoes while fending off incoming waves of Japanese aircraft launched from Luzon and other parts of the Philippines. In a demonstration of just how profoundly air power had reshaped naval warfare, Third Fleet’s pilots fatally wounded Musashi, one of the IJN’s two Yamato-class battleships. The largest battleships ever built, the Yamato-class ships had been feted as nigh unsinkable symbols of Japan’s naval might.32 Now, lacking air support, they had become target practice for the determined squadrons of Third Fleet, with Musashi alone taking between 20 and 30 hits from bombs and torpedoes. Despite considerable effort being made to save her, she would sink at 1900, taking 1,100 sailors into the deep with her. Tellingly, just prior to going down with his ship, Rear Admiral Toshihira Inoguchi expressed considerable regret at having placed so much faith in big guns and big ships.33

U.S. naval air power proved just as effective against airborne foes as it did against surface ones. Over the course of the battle, the Japanese sent three waves of 50 to 60 shore-based planes, all of which were fearlessly met by aircraft from Third Fleet. During the first wave alone, Commander David McCampbell and Ensign Roy Rushing of Essex (CV-9) were able to shoot down a combined 15 planes. McCampbell’s nine kills alone were a record for a single engagement, one that would subsequently earn him the Medal of Honor.34 Despite such heroics, at least one Japanese plane did manage to get through and bomb Princeton (CVL-23) at 0938. Although the initial damage was not fatal, a fire in the ship’s interior caused an explosion in her torpedo stowage at 1523. Unfortunately, the explosion not only mortally wounded Princeton, but also caused significant casualties (229 killed, 420 wounded) on board Birmingham (CL-62), which had pulled alongside the carrier to aid her.35

This tragedy notwithstanding, the U.S. Navy’s overall successes in the air were crucial in forcing Kurita to reverse course. With the operation having lost a significant number of aircraft even before it had begun, Kurita lacked the air cover necessary to fend off the swarms of bombers that Halsey launched at his force that day. Recognizing that he was at a severe disadvantage, the Japanese admiral retired westwards at 1600, both in the hopes of avoiding further damage and giving the impression that he was in full retreat. Despite the significant loss of Musashi and cruiser Myoko, as well as the earlier losses he had sustained off Palawan, Kurita still retained a formidable force of 22 ships (four battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and ten destroyers). Although he could not possibly hope to compete against Third Fleet, he still had sufficient numbers to attack the amphibious forces of Seventh Fleet, assuming he could make it through the San Bernardino Strait unmolested. Hoping to bolster his fatigued commander’s resolve, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet, sent Kurita a message at 1800, exhorting, “Trusting in Divine guidance, resume the attack.”36

Kurita’s “retreat” marked the end of the first engagement of the Leyte campaign (the Battle of Sibuyan Sea). While the U.S. Navy had suffered some casualties, they had inflicted far more damage on the Japanese Center Force. Despite these early successes, however neither Halsey nor his staff could rest easy. To this point, most of the aircraft encountered by Third Fleet had been shore-based, leading Halsey’s air operations officer, Commander Douglas Moulton, to eloquently inquire, “Where in the hell are those goddamn carriers!?”37 Such questions only intensified when two air squadrons from Enterprise (CV-6) spotted Nishimura’s Southern Force steaming through the Sulu Sea at 0820 sans any carriers.38 It would not be until 1245, when Langley (CVL-27) detected fighters inbound from the north, that they realized that the Japanese carriers were approaching from the north.

What they did not learn until much later is that this fleet (dubbed the “Northern Force”) was the decoy force outlined in the Shō-1 plan. Indeed, Vice Admiral Ozawa was actually so eager to be found that he had repeatedly broken radio silence in the hopes of getting Third Fleet’s attention. When this failed to work, he launched nearly all of his aircraft (little more than 110 in all), both in the hopes of relieving pressure on Kurita’s Center Force and attracting Halsey’s notice. On the latter account, he succeeded, as planes from TG 38.3 finally discovered the Northern Force at 1640.39 Having finally found his quarry, Halsey had to decide whether to pursue them or maintain station in the Sibuyan Sea in the event that the Center Force returned. Ever eager to go on the offensive, Halsey ultimately chose the former course, a decision that would eventually come to overshadow nearly everything that had been achieved at Sibuyan Sea.

We shall examine this decision momentarily, but for now, let us remain focused on the battle just fought. In certain respects, few naval battles of World War II demonstrate just how profoundly air power had reshaped naval warfare than Sibuyan Sea. Well before the battle had even commenced, the Japanese had been placed at a severe (perhaps even fatal) disadvantage with the loss of so many aircraft in the Philippine Sea and over Formosa. Unable to muster sufficient air support for its upcoming mission, the Center Force would be forced to rely primarily on its anti-aircraft (AA) guns to counter the threat from the skies above, a rather inadequate solution as the loss of Musashi proved. Built to go head to head with any ship afloat, the majestic battleship was nonetheless rendered impotent by the lack of air support and the repeated air attacks against it. Her rather inglorious end was not only a huge blow to the Japanese, but also seemed to send an unmistakable signal that the era of the battleship had finally come to an end. To a large extent, this was quite true, but, as we shall see, the battleships still had at least one more engagement to fight, one that would end on a decidedly more triumphant note for the U.S. Navy.

“Make All Ready for a Night Battle”: Last Clash of the Battleships in Surigao Strait

Although the Battle of Sibuyan Sea had offered yet another example of just how profoundly air power had changed naval warfare, the big guns of the battleship still had one last song to sing before their final curtain call. The stage for this final performance would be Surigao Strait; the leads, Rear Admiral Oldendorf and Vice Admiral Nishimura; the production, an updated interpretation of a maritime classic that had previously been performed at such illustrious venues as Tsushima in 1905 and Jutland in 1916. It was, to put it less poetically, a classic naval surface engagement between big-gun fleets, one which saw the combined forces of TG 77.2, 77.3, and Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 56 absolutely decimate the Japanese Southern Force using the sort of maneuvers that could have come straight out of any war college textbook. While at least some of this outcome can be attributed to last-minute revisions to the Shō-1 plan and poor coordination among the Japanese forces, it was also a rare example of a meticulously drawn-up battle plan being executed to near perfection.

In its earlier iterations, the Shō-1 plan had not actually called for a separate force to attack Leyte through the Surigao Strait. Instead, the strait was supposed to serve as an exit for Kurita’s force. However, at 1006 on 20 October, Vice admiral Ryūnosuke Kusaka, Admiral Toyoda’s chief of staff, recommended that Kurita detach part of his force to head through Surigao Strait so that they might attack Seventh Fleet from both the north and the south. Kurita concurred with this recommendation and detached seven ships (including battleships Fuso and Yamashiro) under the command of Vice Admiral Nishimura. Curiously, it was around this same time that Vice Admiral Shima received permission to also take the Second Striking Force through the Surigao Strait. One might assume that this force was intended to reinforce Nishimura’s, but for whatever reason, there was no actually coordination between the two.40 Indeed, Kurita was not even aware that Shima had been assigned to the operation until after he had drawn up his plans for Nishimura.41 As a consequence, Nishimura’s Southern Force would enter the strait ahead of the Second Striking Force.

Although the U.S. Navy would soon have to deal with its own coordination and communications issues, at least when it came to defending Surigao Strait, all commanders involved were very much on the same page. Once word arrived that some of Enterprise’s planes had come into contact with Nishimura’s force, Kinkaid sent a message to Oldendorf at 1443, ordering him to “Make all ready for night battle.”42 Consisting of 40 ships, Oldendorf’s squadron already significantly outnumbered the seven ships of the incoming Southern Force. To further tilt the odds in their favor, Kinkaid also detached a group of torpedo boats to patrol the southern end of the strait. These would serve as forward sentries, informing Oldendorf when the Japanese Southern Force entered the strait and then harrying its ships until they came within range of his guns.

Having received his orders, Oldendorf set about developing a battle plan for the upcoming engagement. Taking advantage of the strait’s geography, Oldendorf positioned his destroyers along both sides of the strait while his cruisers and battleships formed the main line across the strait. If all went according to plan, the incoming column of Japanese would be subjected to torpedo attacks by the destroyers and then finished off by raking gunfire from the battleships and cruisers that formed Oldendorf’s battle line. The latter’s firing range would be somewhat limited by the fact that they were mainly carrying high-capacity (HC) explosive rounds meant for shore bombardments rather than armor-piercing (AP) rounds,43 but this would not be a serious impediment in the forthcoming action.

From a tactical standpoint, Oldendorf’s plan was quite sound, but, like any plan, its success would depend on those carrying it out. Wanting to make sure that his commanders had a thorough understanding of the plan and how they it was to be carried out, Oldendorf invited his task force commanders, Rear Admiral George L. Weyler (the battle line) and Rear Admiral Russel S. Berkey (right flank) over to his flagship (Louisville [CA-28]) to discuss every aspect of it from necessary range of the guns to how best to utilize torpedoes.44 According to Captain Roland N. Smoot, commander of DesRon 56, this was very much in character for Oldendorf. As he recalled, Oldendorf was “a very thorough and meticulous man, and one for whom I had the greatest admiration, because he left no stone unturned to be sure that all of his Commanding Officers were versed in the way he thought and how he was going to do this operation.”45 Such praise stands in stark contrast to some of the criticisms leveled at Oldendorf’s opponent, Vice Admiral Nishimura, whose officers later questioned his “indifference at not attending the briefings,”46 and the fact that his “tactical conceptions were quite different from those of the other ships under his command.”47

With all preparations complete, there was little else Oldendorf and his forces could do but wait. Only vaguely aware of the force assembled to meet him in confines of the strait, Nishimura’s Southern Force entered it around midnight and was almost immediately swarmed by torpedo boats. Although they failed to hit any of the Japanese ships with their torpedoes, they at least provided Oldendorf with crucial intelligence concerning the disposition and composition of the enemy fleet. Almost immediately, he knew that seven or eight ships were proceeding through the strait and that they would reach his position in approximately two and half hours.48

While awaiting the arrival of the Southern Force, Oldendorf worried that Nishimura would stop and reverse course in an attempt to draw him deeper into the strait. He need not have been concerned, as Nishimura instead moved his destroyers to the front of the column and increased his speed, apparently intent on plowing headlong into Oldendorf’s battle line. The admiral could scarcely believe his good fortune. Although he had planned for this possibility, he had not actually expected the Japanese to engage in such a reckless maneuver, one that would leave them exposed to gunfire from his entire battle line while limiting them to using just their forward guns. Known as “crossing the T,” this was exactly the sort of scenario “dreamed of, studied, and plotted in War College maneuvers and never hoped to be obtained.”49 The Japanese had won the Battle of Tsushima in 1905 using just this sort of maneuver and now they were poised to be on the receiving end of it. As Oldendorf recalled, “It can readily be seen that the force at my disposal was enormously superior to the Southern Japanese Force…. Is it any wonder that I could not quite believe that this far outmatched Jap force would really run headlong into us?”50

Oldendorf’s incredulity was understandable, but it must emphasized that the Southern Force’s strategy was very much in line with the daring and desperation that underlay other parts of the Shō-1 plan. While his orders had only stated that he was to transit the Surigao Strait and rendezvous with the Center Force in Leyte Gulf, Nishimura was wise enough to know that his mission was likely one-way, intended primarily to divert part of the Seventh Fleet similar to how Ozawa’s carriers were intended to distract the Third Fleet. Even knowing this, Nishimura was determined to carry his mission out at all costs, perhaps believing that his forces might either win, or at least, distract Oldendorf’s squadron long enough to allow Kurita’s Center Force more time and opportunity to sneak into Leyte Gulf and destroy the landing forces.51

Regardless of Nishimura’s intentions and expectations, Oldendorf was not about to give him any quarter. Muttering, “This is going to be good,”52 he ordered his ships to open fire on the approaching Southern Force at 0240. The destroyers were the first to attack, launching wave upon wave of torpedoes that would slam against the hulls of the vulnerable Japanese ships. In the first half hour alone alone, the Japanese Southern Force would suffer significant casualties, with Fuso and Yamashiro receiving significant damage, while destroyers Asagumo and Michisio were disabled entirely. Destroyer Yamagumo, on the other hand, exploded in spectacular fashion, quickly sinking within a matter of minutes. According to an eyewitness, the fiery wreckage made a sizzling sound as it sank into the water, “like a huge red-hot iron plunged into water.”53 All of this was before Oldendorf had even brought his cruisers and battleships forward.

Prior to World War II, the United States and Japan had expected their big-gun fleets to play a critical role in any hostilities, but the emergence of the aircraft carrier and naval air power had largely relegated the battleship to the sidelines of many engagements and left them to serve as oversized escort ships.54 Now, for the first time during the war, they were finally involved in just the sort of battle they had been built for. After Oldendorf’s cruisers engaged the enemy at 0351, his battleships’ 16-inch guns roared to life at around 0353. Fittingly, one of the opening salvos was fired by West Virginia (BB-48), which had been sunk during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Raised from the harbor and refitted, she and her sister ships had waited three long years for this very moment. She made it count, hitting Nishimura’s flagship Yamashiro dead on with her very first shot.55

Much to his chagrin, Oldendorf saw very little of this. In his zeal to see Louisville’s big guns in action, he had failed to shield his eyes, causing him to be temporarily blinded when they fired.56 Fortunately, DesRon 56 commander Captain Smoot was able to provide him with a rather poetic description of the action, observing that, “The devastating accuracy of this gunfire was the most beautiful sight I have ever witnessed. The arched line of tracers in the darkness looked like a continual stream of lighted railroad cars going over a hill. No target could be observed at first, then shortly there would be fires and explosions, and another enemy ship would be accounted for.”57

From the Japanese perspective, the reality of the situation was far less poetic than Smoot had described. Oldendorf’s fleet absolutely decimated the Southern Force, ultimately sinking five ships including Fuso and Nishimura’s flagship Yamashiro. On the two battleships alone, 3,500 hands went to the bottom of the strait,58 almost one and half times the number killed at Pearl Harbor. By the time Shima’s fleet finally arrived, only Mogami and Shigure were still afloat (although the former would soon have to be abandoned). Amazingly, no one among on board the surviving ships thought to warn Shima what awaited him at the other end of the strait. It was only as he got closer to Oldendorf’s position and saw the strait lit up by the burning, twisted hulks of sinking ships that he learned of the Southern Force’s fate. Recognizing the futility of pressing forward, he retreated southward.59

Compared to the significant casualties they had inflicted on the Japanese, the Allied losses had been fairly minimal save for those on board Albert W. Grant (DD-649). In one of the war’s tragic ironies, the ship had experienced engine trouble during the battle, leaving it exposed to the withering crossfire from both Yamashiro and Oldendorf’s battle line. Smoot’s enthusiasm turned to horror when he realized what was happening. He immediately got on the radio at 0408 and alerted Oldendorf that, “You are firing on ComDesron 56! We are in the middle of the channel!”60 By the time the Oldendorf’s battle line stopped firing, 34 men were already dead or dying. More might have perished had their commanding officer, Commander Terrell A. Nisewaner, not gone down into the forward engine room (one of the hardest-hit areas of the ship) and carried out a number of wounded.61

Even accounting for this tragedy, Surigao Strait was still arguably one of the more lopsided naval victories of World War II, one that to this day stands as both the last engagement fought directly between battleships and one of the few in which a fleet successfully crossed its opponent’s “T.” While the ultimate outcome was not particularly in doubt given Oldendorf’s numerical superiority and the Southern Force’s suicidal approach, the engagement could have exacted a considerably higher toll on the U.S. ships had the planning or the execution been lackluster. Neither was, however, something which is attributable in part to the high degree of preparedness of all involved. As Captain Jack H. Duncan of Phoenix (CL-46) enthused in his after-action report, “I was most forcibly impressed with the calmness and coolness of action of all hands. Here was the peak of every naval man’s fighting man’s ambition—a major surface engagement! Here we were in a situation which every officer and man in the Navy would give a right arm to share! Here we were carrying the ball in the pay-off! Yet one would think from the appearance of all hands that routine drill was being carried on, in oil-smooth fashion.”62

Oldendorf deserves at least some of the credit for this as he not only drew up the battle plan for the engagement, but also ensured that those involved had a firm understanding of it. The CINCPOA report on the operation praised Oldendorf as “a man holding a handful of aces or trumps,” who “played them with consummate skill.”63 For his part, Oldendorf merely noted, “Luck plays a part in any battle. I myself, I admit, after 40 years of training, was lucky to be there in command. But the force that I commanded was well balanced and war seasoned—manned by able officers and men who, when the order came to open fire, knew what to do—and did it.”64 Such modesty was characteristic of Oldendorf’s views on command and its role in winning battles. As he reflected at another point in his memoir, “Neither land nor sea battles are any longer won (if they ever were) by the unaided genius of any individual who suddenly changes the whole course of action by some order that proves to be so clear and so unanswerable as instantly to decide the outcome.”65 Left unsaid was the fact that while battles might not be won by the “unaided genius” of individuals, they could indeed be lost on account of it. Such was nearly the case of William Halsey and his fateful decision to pursue the Northern Force.

“Where is Task Force 34?”: Decision and Indecision off Cape Engaño

Following the Battle of Sibuyan Sea, Halsey had a critical decision to make, one which, in his view had the potential to not only influence the outcome of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but the war itself. To the north, just off Luzon, lay the Japanese carrier fleet that had served as the heart of Japan’s naval might since the war’s beginning. To the west lay the Center Force, which had been bloodied, but now appeared to have resumed its approach toward the San Bernardino Strait. Both were potential threats to the Leyte operation, but, in Halsey’s view, only one of them could be dealt with at a time. Faced with the choice of going on the offensive against the Japanese carriers or guarding the strait against the Center Force, Halsey chose the former option, and, in doing so, exposed Seventh Fleet to a devastating attack from the Center Force. Controversial even at the time it was made, Halsey’s decision is a cautionary tale that highlights the need to maintain flexibility of thought in the heat of battle. It also highlights the importance of establishing clear channels of communication among forces, firm awareness of the overall strategic objectives, and creating a command culture that both permits and encourages collaboration and criticism.

Given its significance, it is just as important to analyze why Halsey made his decision as it is to understand its fateful consequences. It must be strongly emphasized at the outset that Halsey’s decision to pursue the Japanese carrier force was not an inherently poor one nor was it entirely unworkable. While it is true that the Northern Force was intended to serve as decoy and possessed very few surface aircraft, Halsey could not know either of these things for certain. In fact, all he knew at the time was that there was a sizable enemy carrier force to the north, one that likely possessed the capability to strike at both him and other forces operating in and around Leyte. Equally important, its proximity to Luzon might have enabled its aircraft to rearm and refuel ashore, allowing them to conduct shuttle bombing runs. Given these possibilities, one can understand why Halsey deemed the Northern Force a more significant threat than it actually was.66

Even bearing this in mind, the innately pugnacious admiral still had to weigh these considerations against the possibility that Kurita’s Center Force would return and try to slip through the San Bernardino Strait. Halsey did not consider this likely, having been led to believe by his pilots’ reports that the Japanese Center Force was considerably more damaged than it actually was. As he wrote in his action report, “Jap doggedness was admitted, and Commander THIRD Fleet recognized the possibility that the Center Force might plod through the San Bernardino Straits and on to attack Leyte forces, a la Guadalcanal, but Commander THIRD Fleet was convinced that the Center Force was so heavily damaged that it could not possibly win a decision.”67 Halsey probably should have been more skeptical of his pilots’ claims (aviators on both sides were notorious for inflating the number of enemy ships destroyed), but again, this was all the intelligence he had to work with.

Given these possibilities, Halsey had to carefully weigh the prospect of destroying the Japanese carrier force against the need to defend the San Bernardino Strait. Theoretically, he could have achieved both ends by leaving behind a portion of his forces to guard the strait while he proceeded north with the remainder. However, the notion of dividing one’s forces was antithetical to one of the prevailing strategic principles of the time, namely, that it was imperative to always concentrate one’s forces.68 Deeply influenced by the ideas of Mahan and the exploits of Horatio Nelson, Halsey was not about to violate this seemingly core tenet of naval strategy, particularly if it meant leaving TF 34 without air support.69 As such, the choice between pursuing the carriers and defending the strait was, in Halsey’s view, a purely a binary one.

Prudence would have dictated that Halsey should guard the strait, but as his operations officer, Commander Rollo Wilson, argued, this would be akin to watching “a rat hole, waiting for the rats.”70 Aware of the criticism Spruance had endured for demonstrating too much “nuance” at Philippines Sea and believing that destruction of the carriers would “mean much to future operations,”71 Halsey was not about to let them escape. Indeed, to do so would go against the very core of his command philosophy. As he later wrote in his autobiography, “If any principle of naval warfare is burned into my brain, it is that the best defense is a strong offense—that as Lord Nelson wrote in a memorandum to his officers before the Battle of Trafalgar, ‘No Captain can do very wrong If he places his Ship alongside that of an Enemy.’”72

In an age in which fleets were regularly attacking each other from hundreds of miles away with technology undreamt of in the 18th and 19th centuries, relying on the wisdom of Horatio Nelson might seem imprudent, but in fairness to Halsey, he was not the only officer of his generation who had worshipped at the twin altars of Nelson and Mahan. We must remember, after all, that when Halsey and his fellow officers first entered the Naval Academy, naval aviation did not even exist and the most recent naval action during their lifetimes was Dewey’s triumph at the Battle of Manila Bay. For them, the model of a successful officer was one who had been in the thick of the action, fighting ship-to-ship engagements with, at best, a small number of ships. Although Halsey would adapt very well to the many technological and doctrinal shifts that had subsequently occurred (he had even earned his naval aviation wings), at heart he was still very much a traditionalist, eager to take direct command of any situation and to engage the enemy aggressively.

Such qualities had served Halsey quite well in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, when the Navy’s collective morale stood on a knife’s edge and bold action was needed to dispel the aura of invincibility that surrounded the Japanese Combined Fleet. The situation had changed considerably since that time, however. Carrier duels, such as the one Halsey now hoped to engage in, had not been fought since the Battle of Santa Cruz in October 1942, having largely given way to support operations for amphibious assaults such as the one Third and Seventh fleets were now engaged in. Such operations required both a greater degree of strategic flexibility and a support-oriented mindset to achieve their objectives, namely, protecting and assisting the troops on shore while denying the enemy supplies and reinforcements. Halsey had begrudgingly adapted to this new reality during his campaigns against New Georgia and Bougainville,73 but he never lost his instinctive aggressiveness nor his desire to go toe-to-toe with the Japanese fleet on the high seas.

Now, at Leyte, this instinct threatened to get the better of him. Even before the Japanese Combined Fleet appeared, Halsey chafed at the “restrictions” imposed by having to cover the landings and asked permission to operate out of the South China Sea. Nimitz reminded him that “There was no shortage of tasks set forth in his Operation Plan No. 8-44 and that any restrictions imposed by covering the SOUTHWEST PACIFIC Forces were unavoidable.”74 MacArthur also admonished Hasley that, “The basic plan for this operation in which for the first time I have moved beyond my own land-based air cover was predicated upon full support by the Third Fleet; such cover being expedited by every possible measure, but until accomplished our mass of shipping is subject to enemy air and surface raiding during this critical period;… consider your mission to cover this operation is essential and paramount.”75 None of this seems to have made a deep impression on Halsey. Latching onto the caveat in his original orders, he was prepared to risk leaving the San Bernardino Strait unguarded in order to pursue Ozawa’s carriers. From his perspective, destroying the carriers was not only an opportunity to mortally wound the Japanese fleet, but also an opportunity to achieve something that, “I had dreamed of since my days as a cadet.”76

This aggressive, individualist attitude appears to have not only influenced Halsey’s decision-making, but also filtered down to his staff. Although all were competent, outspoken officers in their own right, “group think” appears to have taken hold during deliberations on board New Jersey (BB-62), with almost all of those involved readily assenting to Halsey’s plan.77 Perhaps as a consequence of this, Halsey did not consult his plans, intelligence, or radio officers, nor for that matter, any of his task group commanders. Had he done so, he might have received a very different set of opinions. Mike Cheek, his intelligence officer, told Moulton, “They’re coming through [the San Bernardino Strait], I know, I’ve played poker with them.” Unable to convince Moulton, he took the matter to Halsey’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral Robert Carney, hoping to persuade him to wake the admiral. Carney was reluctant to wake Halsey, but told Cheek he was more than welcome to do so. He warned him, however, that Halsey had been without sleep for 48 hours and that he had already overruled the last person who dissented. Cheek chose to walk away. As he recalled years later, “I silently agreed that any effort on my part would be useless.”78

During the transit northwards, planes from Independence (CVL-22) spotted navigation lights along the San Bernardino strait and possibly even Kurita’s Center Force. Vice Admiral Gerald F. Bogan attempted to report this information to Halsey, but, as the admiral was resting, one of his staff brushed him off. Vice Admiral Willis Lee likewise was ignored when he attempted to reach Halsey in the hopes of being detached to guard the strait.79 Commodore Arleigh Burke did not even get that far. As he recollected, when he went to Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher to send a dispatch, the admiral told him, “There’s nothing worse than changing orders in a battle, then having a subordinate come in and criticize a plan that’s being executed…. I don’t think we ought to bother Admiral Halsey. He’s busy enough.” Burke was not deterred. He went back and rewrote the dispatch he drafted to suggest leaving behind a force of battleships and one carrier task force to guard the strait. Again, Mitscher rebuffed him, stating, “Admiral Halsey is in command. He has all the information. He’s drawn different conclusions than we have. He can be right. If we start making critical analyses, it’s going to confuse an already hectic operation.”80

Mitscher’s subdued reaction and refusal to send Burke’s dispatch were rather uncharacteristic, as he normally had no hesitation about forcefully articulating his opinion to his superiors. Some have speculated that he was smarting from Halsey having shunted him aside to assume direct control over carrier operation, while others, such as Burke, have drawn attention to the fact that he was in rather poor health by this point in the war. His assertiveness may have also been tempered by previous experiences, namely, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, in which his attempts to urge Spruance to go on the offensive received a cold reception.81 Whatever the case may be, this was precisely the wrong time for him and Halsey’s other commanders to show deference and assume that the admiral had “all the information” or that “any effort” to persuade him “would be useless.” Just as a ship requires its crew to assume a questioning attitude and provide forceful backup, so too do senior commanders need their subordinates to speak up when they appear to have overlooked something. Unfortunately, Halsey’s subordinates were either unwilling or unable to express their concerns, something which may have been the product of the admiral’s own forceful personality and an unwillingness to solicit opinions from those outside of his inner circle.

This breakdown in communications extended beyond Third Fleet. While Halsey was deciding how best to proceed, he sent messages to Third Fleet, Nimitz, and King stating that TF 34 “will be formed.” In his view, the wording indicated this was merely a contingency, but both Nimitz and King assumed otherwise. So, too, did Kinkaid, who had intercepted the message even though it had not been addressed to him. Consequently, when Halsey messaged Kinkaid at 2024 to indicate that he was, “proceeding north with 3 groups to attack enemy carrier force at dawn,” the Seventh Fleet commander assumed that Halsey had left a fourth group (TF 34) behind to guard the San Bernardino Strait. What Halsey really meant to say was that his group and three others were proceeding northward.82

Unaware that his messages were being misinterpreted, Halsey concentrated his forces at 2345 and began his run northward. Although Mitscher had anticipated encountering the enemy fleet at around 0430, TF 34’s search planes lost contact with the Northern Force during the night. Not wanting to lose the initiative, Mitscher launched not only his search planes at dawn, but also his air patrol and strike group. The latter would trail behind the search planes, ready to strike as soon as contact was made. This much-awaited event came at 0735, when one of the planes caught sight of the Northern Force approximately 140 miles east of TF 38’s position. Wasting no time, the first strike group launched their attack at 0810. Both they and Halsey were surprised at the absence of planes in the air and on the decks of the Japanese carriers, but it was assumed that they had merely surprised the Japanese at an inopportune moment. Quickly dispatching the 15 or so aircraft that were covering the Northern Force, the first strike group hammered the Northern Force, sinking light carrier Chitose.83

TF 38 was just about to launch its second strike group when Halsey received an urgent dispatch from Kinkaid. Delivered in plain language, Kinkaid alerted Halsey that, “Enemy BB and cruiser reported firing on TU 77.4.3 from 15 miles astern.”84 Shortly thereafter, he sent another dispatch, stating, “Urgently need fast BBs Leyte Gulf at once.” Several more requests of this nature followed over the course next hour and a half, much to Halsey’s aggravation. From his point of view, not only should Kinkaid and Sprague have detected the Center Force passing through the San Bernardino Strait, but they should have had more than enough ships to repulse it. It was not until he received another missive from Kinkaid informing him that Oldendorf’s battleships were low on ammunition that he began to grasp the severity of the situation.85 Even so, Halsey felt there was little he could do save detach TG 38.1 under Vice Admiral John S. McCain, which, at this point, was en route from Ulithi.

At 1000, just as the second striking group was beginning its run against the Northern Force, Halsey received another message, this one from none other than Chester Nimitz. It read, “WHERE IS RPT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR THE WORLD WONDERS.” The last part was originally just padding that had been added by a junior communications officer in order to complicate Japanese decryption attempts, but it somehow made its way into the message Halsey received. Believing that Nimitz’ had just slighted him, Halsey reacted with characteristic fury, only calming down when his chief of staff, Rear Admiral Carney, admonished him with the sternest possible language. With his battleships just 42 miles away from the Northern Force, Halsey was on the verge of fulfilling his “dream” to engage the enemy fleet head on. However, he knew that he could no longer ignore the dire situation in the south. Thus, with great reluctance, he ordered part of TF 34 (including his own flagship New Jersey) to detach itself and turn south. Ironically, having justified his decision to head north as being based on the need to maintain concentration of his forces, he was now dividing them.86

Of course, by this point, the battle’s outcome was not really in doubt. After the third strike at 1435, the Japanese task force was pretty much finished, have lost or on the verge of losing two destroyers, one cruiser, and four carriers. The latter group included Zuikaku, the last surviving carrier to have participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. More strikes would be launched over the remainder of the day, but, for all intents and purposes, the Battle of Cape Engaño had become a cleanup operation. Even so, Halsey would have given much to participate in this. Having missed his opportunity to do battle with a Japanese fleet, he would find himself similarly frustrated when he reached San Bernardino Strait. By that point, the action off Samar had ended and the Center Force had retreated through the strait.87 He would later bitterly reflect that, “My real mistake was in turning around.”88

The only battle left for Halsey to fight that day would be the one to salvage his reputation. Although he was not openly criticized by his superiors, many fumed privately at his decision to leave the San Bernardino Strait. According to General Richard Sutherland, MacArthur’s chief of staff, his boss was beside himself with fury, charging Halsey “with failure to execute his mission of covering the Leyte operations…. Gen. MacArthur repeatedly stated that Halsey should be relieved and would welcome his relief as he no longer had confidence in him.” 89 Back in Washington, the President’s chief of staff, Admiral William D. Leahy, also had watched situation unfold with increasing horror. In his assessment of Halsey’s actions, he noted, “We did not lose the war on account of it, but I don’t see why we didn’t…. I thought we were going to. Halsey started a little war of his own.”90

For the remainder of the war, this criticism would remain behind closed doors. It would only be after the war, when Halsey published his autobiography laying the blame squarely at the feet of Kinkaid, that the controversy became public and turned into a battle in its own right.91 True to form, Halsey refused to back down, maintaining to the bitter end that he had made the right call. Not many were inclined to agree with him. While the outcome of the Battle of Cape Engaño was, on its own, one that the Navy could rightfully take pride in, it came at the expense of Seventh Fleet and was the product of a decision that was made without consideration for the overall mission or the flexibility to adapt to the situation at hand. While Halsey would maintain until the bitter end that his mission was an offensive one, he did ruefully concede at one point that, “I wish that Spruance had been with Mitscher at Leyte Gulf and I had been with Mitscher in the Battle of the Philippine Sea.”92 On this count, he was not alone, as many among and outside Seventh Fleet held a rather similar attitude,93 particular those who had survived the fateful consequences of Halsey’s actions. For them, glory was not something to be pursued, but rather, something that they would have thrust upon them.

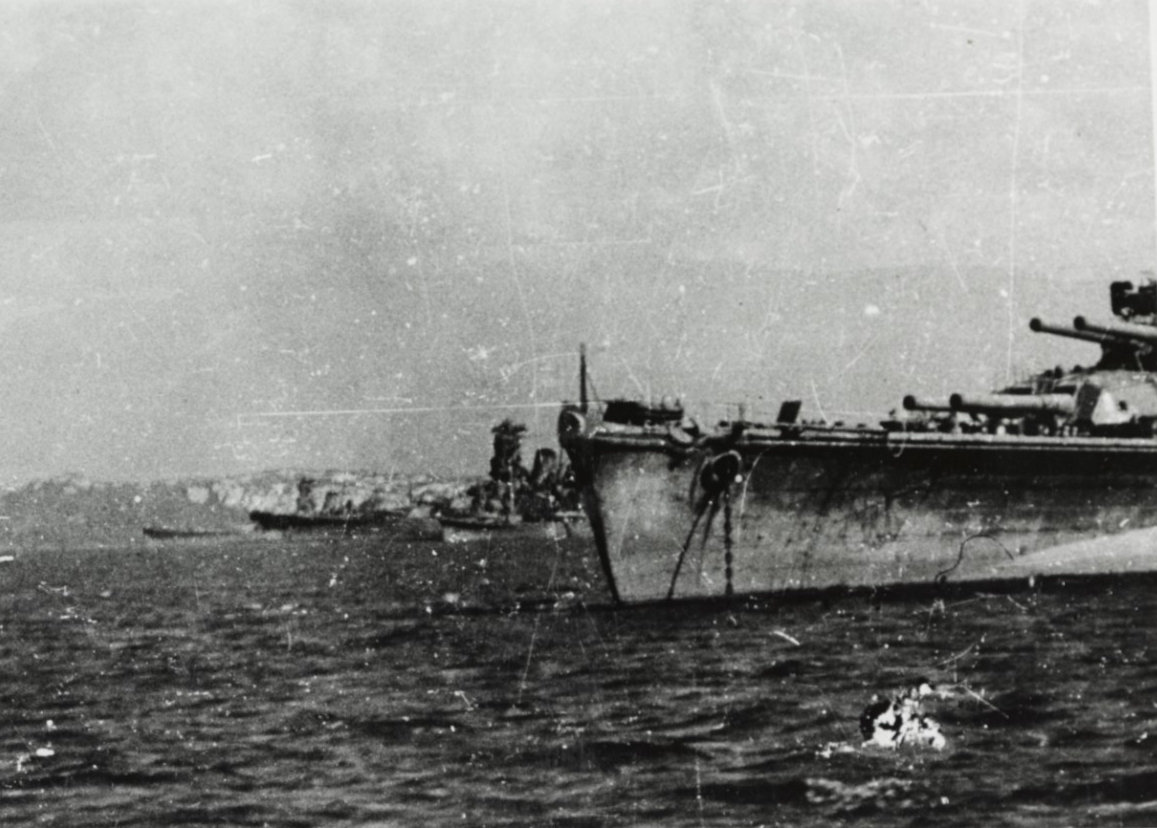

Japanese aircraft carrier Zuiho under attack by planes from USS Enterprise (CV-6) during the Battle of Cape Engaño, 25 October 1944.

In Harm’s Way: The Battle off Samar

Throughout its history, the U.S. Navy has had many “finest hours.” Whether it be John Paul Jones exclaiming, “I have not yet begun to fight” during the Battle of Flamborough Head in 1779 or David Farragut allegedly crying out, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” during the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864, every U.S. Navy sailor has been indoctrinated with tales of determined commanders and crews fighting against overwhelming odds who somehow emerged victorious. By World War II, such tales of individual heroism may have begun to seem increasingly antiquated given the sheer number of vessels involved in operations, the complexity of the strategies that underlay them, and the participation of forces from the skies above and beneath the seas. As Vice Admiral Kinkaid observed, “Today, there is no room for heroics. Today, the forces involved are much larger and much more important. The issues are not only the differences to be settled between two ships or even between the two countries concerned. They are issues of world-wide significance.”94 From the standpoint of naval strategy, Kinkaid was not wrong, but he should have known better than anyone to dismiss the role of heroics. After all, were it not for the heroism and the sacrifices of those on board the ships of Seventh Fleet’s very own “Taffy 3,” the Battle of Leyte Gulf may very well have been remembered as one of the worst disasters in the Navy’s history, rather than among its finest hours.

When Halsey decided to turn his fleet northward, he did so in the belief that the Japanese Center Force was far too damaged to be much of threat to Seventh Fleet. This assessment turned out to be dangerously inaccurate, as the Center Force still had 22 ships at its disposal. Meanwhile, the bulk of the Seventh Fleet’s firepower (TG 77.2, 77.3, and DesRon 56) had been sent south to Surigao Strait, leaving the northern approach to Leyte Gulf dangerously exposed. This on its own would have been cause for concern, but Kinkaid had further compounded the problem by stationing his carrier groups at the mouth of the gulf. The northernmost one, TF 77.4.3 (henceforth referred to by its call-sign, Taffy 3) would patrol the area east of Samar, putting its right in the path of Kurita’s Center Force.95

Task Group 77.4 consisted mainly of escort carriers and destroyer escorts. In contrast to the fast attack carriers (CVs) that spearheaded Third Fleet, the CVEs (also sometimes known as “jeep carriers”) were relatively small vessels (about 500 feet in length) that carried at most 27 aircraft. They were not intended for engaging surface forces, but, rather, to support convoy and amphibious operations, with their aircraft being used primarily to hunt submarines and provide air cover.96 While this made them the perfect vessels to support the Leyte landings, they were hardly equipped to fight a major surface engagement on their own.

Similar to the fast attack carriers, the jeep carriers of TG 77.4 were protected by a screen of destroyers. Among these ill-fated ships was Johnston (DD-557), a Fletcher-class destroyer that had been commissioned less than a year prior. At her commissioning ceremony, her commanding officer, Commander Ernest E. Evans, channeled the spirit of John Paul Jones, declaring, “This is going to be a fighting ship. I intend to go in harm’s way, and anyone who doesn’t want to go along had better get off right now.” Upon hearing these words, Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Lloyd Campbell recalled, “Nobody made a move. They knew he meant it.”97 Subsequent events would give truth to Evans’s words, as Johnston and her crew had repeatedly put themselves in harm’s way, participating in actions off Bougainville and Guam.

Prepared though they were to risk their lives in the service of their country, no one on board Johnston or any of the other ships of Taffy 3 believed that they be called to do so again on 25 October. The same could be said for Kinkaid and his staff on board Wasatch (AGC-9). Having spent most of the night following reports of the action taking place in Surigao Strait, the admiral was prepared to finally retire for the night when his chief of staff, Captain Richard Cruzen, observed, “We’ve never asked Halsey directly if Task Force 34 is guarding the San Bernardino Strait.” Realizing that he had, in fact, not received any confirmation from Halsey to that effect, Kinkaid dashed off a message to Halsey requesting confirmation. Under normal circumstances, it should have been easy for him to get confirmation, but as we noted earlier, MacArthur had forbidden Kinkaid and Halsey from communicating directly. Instead, Kinkaid would be forced to send his message through the radio station at Manus. There, it would languish for over two hours.98 This delay would prove costly, for by the time Halsey responded, Kinkaid and Seventh Fleet had clearly established that TF 34 was not, in fact, guarding the strait.

The first sign of trouble came at 0637, when Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70) intercepted a Japanese transmission. Shortly thereafter, radar contact was made with unidentified surface craft and antiaircraft bursts were sighted on the horizon. Initially it was thought that these ships were from Third Fleet, but upon sighting pagoda masts, all involved quickly realized that they were up against large force of Japanese vessels. A flurry of reports soon followed from other vessels, bringing the situation into clearer view: The Center Force had transited the San Bernardino Strait, rounded the island of Samar, and was now bearing down on Taffy 3. Almost immediately, Rear Admiral Clifton A. F. Sprague ordered his ships to make smoke while his carriers turned into the wind and launched all planes, regardless of their state of readiness. While they were doing this, the guns of the Japanese ships roared, first targeting White Plains (CVE-66) and St. Lo (CVE-63). Sprague later reflect that, “It did not appear any of our ships could survive another five minutes…. The task unit was surrounded by the ultimate of desperate of circumstances.”99

On board Wasatch, Kinkaid watched the situation develop with mounting dread. A veteran of multiple battles who had been involved in the war since the very start, he knew full well the implications of what was transpiring. As one eyewitness reported, “I watched you undergo one of the most severe strains that I think any human being could ever be required to endure. I refer to the time when you could not understand the lack of support, and justly so, and the moment when you felt that our chances for survival were at a minimum.”100 Facing potential annihilation, Kinkaid immediately messaged Halsey to request assistance. As before, however, his requests were invariably delayed by the communications setup imposed by MacArthur.

In the meantime, Kinkaid had some difficult decisions to make, not the least of which was what to do about Taffy 3. Although he still had Oldendorf’s force at his disposal, the Seventh Fleet commander knew that they were too far south to render immediate assistance. Even if they could, they were also low on ammunition and were still needed to guard against Shima’s Second Striking Force in the event that he too reversed course and came back through the strait. Mindful that his primary mission was to protect MacArthur’s beachhead, Kinkaid ordered Oldendorf at 0850 to proceed just to the north of Hibuson Island. While this placed him in position to render aid to Taffy 3, it was clear that no immediate aid would be forthcoming for the beleaguered task unit.101

Lieutenant Commander Robert Copeland, commanding officer of Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), also knew the situation was dire. Rather than conceal this from his men, he chose a different tact: complete transparency. Getting on the loudspeaker, he announced that this would be “a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival could not be expected, during which time we would do what damage we could.”102 Although all on board were prepared for the worst, many privately hoped that they would somehow managed to pull off the impossible.

On board Johnston, Ernest Evans prepared to make good on his promise to “go in harm’s way.” Even before Sprague could order his destroyer screen to form up, Johnston rushed ahead of Hoel (DD-533) and Heerman (DD-532) to make a torpedo attack. As Lieutenant Robert Hagen recalled, “We felt like David without a slingshot.”103 Nonetheless, she unleashed a furious barrage of nearly 200 rounds from her 5-inch battery, followed by a spread of ten torpedoes. They found their mark, setting Japanese cruiser Kumano aflame. ohnston, however, took six hits for her troubles, resulting in the loss of power to her main steering and her aft guns. Evans himself lost two fingers on his left hand and had the clothing on his upper torso shredded, but he remained unbowed.104 Finding shelter in a nearby rainstorm, he and his crew set about making repairs.

The destroyers were not finished. At 0742, Sprague ordered his screen to make another torpedo attack, this one to include the smaller destroyer escorts (codenamed the “little wolves”). Boldly steaming forward in what can best be described as a maritime rendition of “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” they fought the Japanese ships for well over an hour even as casualties mounted and shipboard systems failed. During this action, Heerman actually went head-to-head against the battleships Yamato and Haruna, causing one of her crew to joke, “What we need is a bugler to sound the charge.”105 Not to be outdone, Samuel B. Roberts launched a daring assault of her own against cruisers Chōkai and Chikuma, firing nearly 608 of her 650 shells and even launching starshells and anti-aircraft rounds. So relentless were her attacks that she subsequently came to be known as the “destroyer escort that fought like a battleship”106 Gunner’s Mate 3rd Class Paul H. Carr was among the chief contributors to this legacy. Manning Samuel B. Roberts’s last remaining 5-inch gun, he kept firing until a breech explosion destroyed it, killing or wounding nearly all of its crew. Mortally wounded himself, Carr nonetheless repeatedly attempted to load a final round into the gun, even as others sought to attend to him. He would posthumously receive the Silver Star for his unwavering devotion to his duty.107

Although Johnston had used up the last of her torpedoes and was running on one engine, Evans was not about to hang back while others risked their lives. Even as Hoel and Samuel B. Roberts succumbed to the overwhelming firepower of the Japanese ships, Johnston continue to race about, providing fire support to any ships in need. Around 0850, she observed Gambier Bay (CVE-73) taking severe damage from a Japanese cruiser. With no thought for his ship’s safety, Evans ordered his crew to “'commence firing on that cruiser, draw her fire on us and away from Gambier Bay.”108 Johnston not only drew the cruiser away, but subsequently interposed herself between the carriers and an approaching force of destroyers led by cruiser Yahagi.

Despite her valiant efforts, Johnston could not long survive the sustained attacks from the ships of the Center Force. As Lieutenant Hagen observed, “We were now in a position where all the gallantry and guts in the world couldn't save us.”109 Surrounded on all sides, she endured heavy fire and sank at 1010. Out of her complement of 327, 186 would be lost including Evans, who is thought to have made it off the ship but then drifted away from the life rafts. Lieutenant Commander Copeland of Samuel B. Roberts would never forget the sight of the bloody and bare-chested Evans waving to him from the fantail as Johnston undertook her final charge toward the Japanese destroyers.110 In signing what Samuel Eliot Morison described as her own “death warrant,”111 Johnston helped to temporarily stall the Japanese offensive against the carriers. Now, out of the fight, her crew and those of the other sunk vessels would wage a different kind of battle, trying to stay afloat until they could be rescued. They would be waiting a considerable period of time.

Taffy 3’s screening vessels were not the only ones who distinguished themselves that day. Many of the planes launched from the escort carriers fought just as tenaciously. Ordered by Sprague to launch shortly after sighting the first pagoda mast on the horizon, some planes launched low on fuel or even without ammunition. Nonetheless, they harried the Japanese ships from all sides, forcing them to take constant evasive maneuvers. Later joined by planes from Taffy 1 and Taffy 2, they helped to sink Chōkai and significantly damaged a number of other ships. Lieutenant (j.g.) L. E. Waldrop performed an even more spectacular feat when he spotted a full salvo of torpedoes headed directly for Kalinin Bay (CVE-68). Heedless of the danger to himself, he dove astern of the torpedo formation and actually managed to explode one with strafing fire.112 Given their effectiveness and persistence, it is no wonder that Kurita actually thought he was under attack from land-based aircraft rather than those from the very carriers he was pursuing.113

Despite efforts from both their screening vessels and aircraft, the escort carriers did not escape their pursuers unscathed. Even before Johnston came to her rescue, Gambier Bay had already been mortally wounded, while Kalinin Bay, White Plains, and Fanshaw Bay all took significant damage from gunfire. St. Lo would experience an even crueler fate. Having finally escaped her pursuers, some of her crew had just been allowed to stand down from General Quarters when a Mitsubishi A6M Zero dove directly into her flight deck at 1051. The ship sank in less than 15 minutes, taking 141 men to the deep with her.114 Ironically, some of her crew had predicted this fate two weeks earlier when they received word that the ship’s name would be changed from Midway to St. Lo. Superstitious to the core, one her crew allegedly exclaimed, “You don’t change the name of a Navy ship. We’ll be at the bottom of the ocean in two weeks!”115 The prediction turned out to be true, though even they could not have foreseen that their ship would have the dubious honor of being the first to be sunk by a kamikaze attack.

On board Wasatch, Kinkaid was growing frantic. Frustrated at all the communication delays, he finally sent Halsey a message in plain language, demanding to know, “Where is Lee!? Send Lee!” Unbeknownst to the beleaguered admiral and the rest of Seventh Fleet, Kurita himself was beginning to experience a crisis of confidence. Although his forces had successfully sunk four U.S. ships (Gambier Bay, Hoel, Johnston, Samuel B. Roberts), he had not expected to encounter such determined resistance. As the hours wore on and he began to take losses of his own, his doubts only began to grow and his judgment of the situation became shakier. Estimating the jeep carriers’ speed to be about 30 knots (in actuality, they could only steam at 18 knots),116 he and his commanders believed that they had no chance of catching them and, indeed, thought they had lost them in the smoke and squalls (they were, in fact, only 7 nautical miles away). The delays also increased his concern about the fuel situation and the possibility that U.S. reinforcements would soon arrive in the gulf, particularly after he learned that Nishimura’s Southern Force had failed in its mission.117 Ironically, Kinkaid’s frantic messages in plain language on an open channel only increased these fears. Rather than interpreting these as an indication that no help was forthcoming, Kurita assumed it was a ruse intended to entrap him. As he later confided, it was “very, very unusual to intercept a message from the United States fleet and I thought perhaps they thought we could not understand English.”118

Ultimately, Kurita decided to turn his ships northward back toward the San Bernardino Strait. His stated reason was that he was concerned that enemy aircraft appeared to concentrate on Tacloban and the disposition of the U.S. Navy ships within the gulf was unknown. Rather than risk his fleet in an engagement in which he would be easy prey for enemy aircraft and unable to maneuver easily, he instead would turn northward, in the hopes of engaging an enemy task force that was supposedly located at “113 miles bearing 5° of Suluan Light at 0945, when it least expected us to come.” It is uncertain where Kurita received this information from, but what is known is that there was no such task force in north, as Halsey was still over 300 miles away.119 Some of Kurita’s own subordinates were skeptical of his stated reasons, particularly Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki. In his diary, he laconically wrote, “I felt irritated on the same bridge seeing that they [Kurita and his staff] lack fighting spirit and promptitude.”120

No such criticism could be leveled at those sailors who had fought off Samar that day. In the face of overwhelming odds, they had managed to hold their own against the Center Force. Were it not for their tenacity and their sacrifice, the Japanese Center Force might very easily have overwhelmed Seventh Fleet and brought the invasion of the Philippines to a grinding halt. Instead, the Center Force was compelled to spend precious hours, fuel, and ammunition doing battle with ships that, by all rights, it should have defeated easily. To be certain, there was still very little chance that the tin cans of Taffy 3 could have survived had Kurita truly wished to press his advantage. As Sprague acknowledged, “The Jap main body could have, and should have, waded through and completed the destruction of this Task Unit.”121 However, their staunch defense provided sufficient time and space for other factors to influence events, not the least of which were doubt and fatigue on Kurita’s part. Unable to secure a quick victory and already worn down by the struggles of the prior two days (including being forced to swim to escape his sinking flagship), the Japanese admiral had been pushed beyond his breaking point, not by the majestic carriers of Third Fleet or the towering battleships of TG 77.2, but by the scrappy jeep carriers and destroyers of Taffy 3. Their crews’ collective and individual heroism continue to serve as a reminders that, for all their complexity, for all the planning they involve, and for all the resources they demand, battles are still fought and won by the bravery, tenacity, the heroism, and the sacrifices made by sailors such as Ernest Evans (who posthumously received the Medal of Honor) and Paul H. Carr. As Lieutenant Commander Copeland (himself a recipient of the Navy Cross) observed of his own crew, even knowing that they faced certain death, “men zealously manned their stations wherever they might be, and fought and worked with such calmness, courage and efficiency that no higher honor could be conceived than to command such a group of men.”122

No Higher Honor

Leyte would not be the last major naval operation of World War II, let alone the last in the campaign to retake the Philippines. It was, however, the culmination of journey that begun on 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and established an aura of seeming invincibility that would persist until Midway. Now, almost three years later, some of very same ships sunk at Pearl Harbor had returned to action and the U.S. Navy had grown exponentially, both in terms of ships and manpower. Having worked tirelessly to achieve ascendancy on the sea, in the skies above, and below the surface, the Navy now struck a mortal blow against the Combined Fleet, forever ending Japan’s dreams of a Pacific empire and maritime dominance.