The Ordeal of PQ-17, 27 June –4 July 1942

On 27 June 1942, Allied convoy PQ-17 sailed eastbound from Iceland, headed for the Soviet port of Arkhangelsk. The convoy was located by German forces on 1 July, after which it was shadowed continuously and attacked repeatedly by aircraft and submarines over the course of a week. The German success was possible through signals intelligence (SIGINT), cryptological analysis, and because the Allied escorts were withdrawn to counter a notional German surface threat, supposedly including capital ships. As the escorts and covering forces (which included the battleship USS Washington —BB-56) moved away toward the west, the merchant ships were ordered to scatter, leaving them even more vulnerable to attack. The ordeal of one crew, featured in the following vignette, was repeated tenfold:

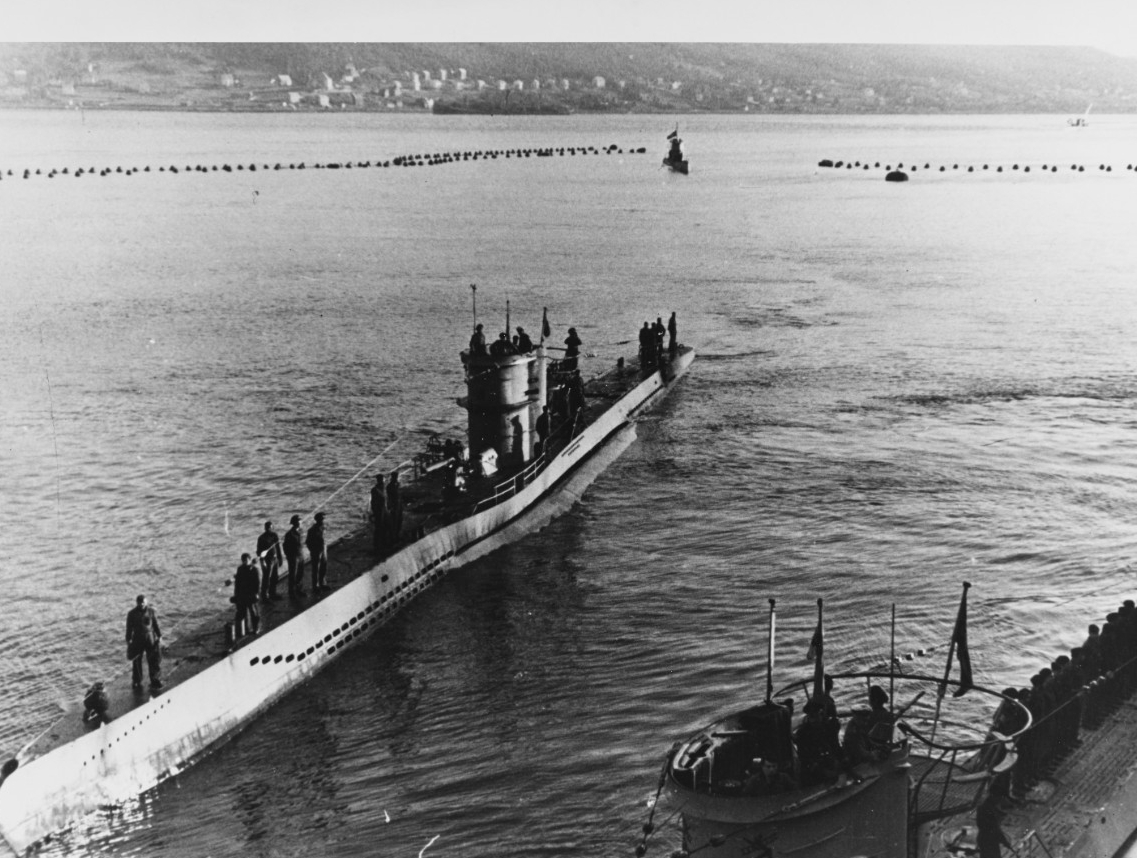

With each passing hour Sailors of the U.S. Navy Armed Guard on the freighter Washington watched in horror as more and more ships in their convoy, PQ 17, fell victim to German submarines and aircraft. Thirty-five merchantmen, a third of them American, escorted by more than a dozen British corvettes, destroyers, and other warships, had departed from Iceland on 27 June 1942. This was the largest and most valuable convoy yet to make the Murmansk Run, carrying more than $500 million of military equipment to the beleaguered Soviet Union. Steaming in the Arctic Ocean on a merchantman was bad enough without the presence of German aircraft and submarines. It was a world of ice and fog, with weather alternating between heavy seas, biting cold, and dull, gray skies, and brilliant summer sunshine, 24 hours a day, under cobalt blue skies. In clear weather, nothing obscured the view from searching German planes. With the convoy coming under unrelenting air and submarine attack and word that the German battleship Tirpitz was heading to sea, the British high command ordered the convoy to scatter and the escort vessels to withdraw, leaving the merchantmen to their fate.

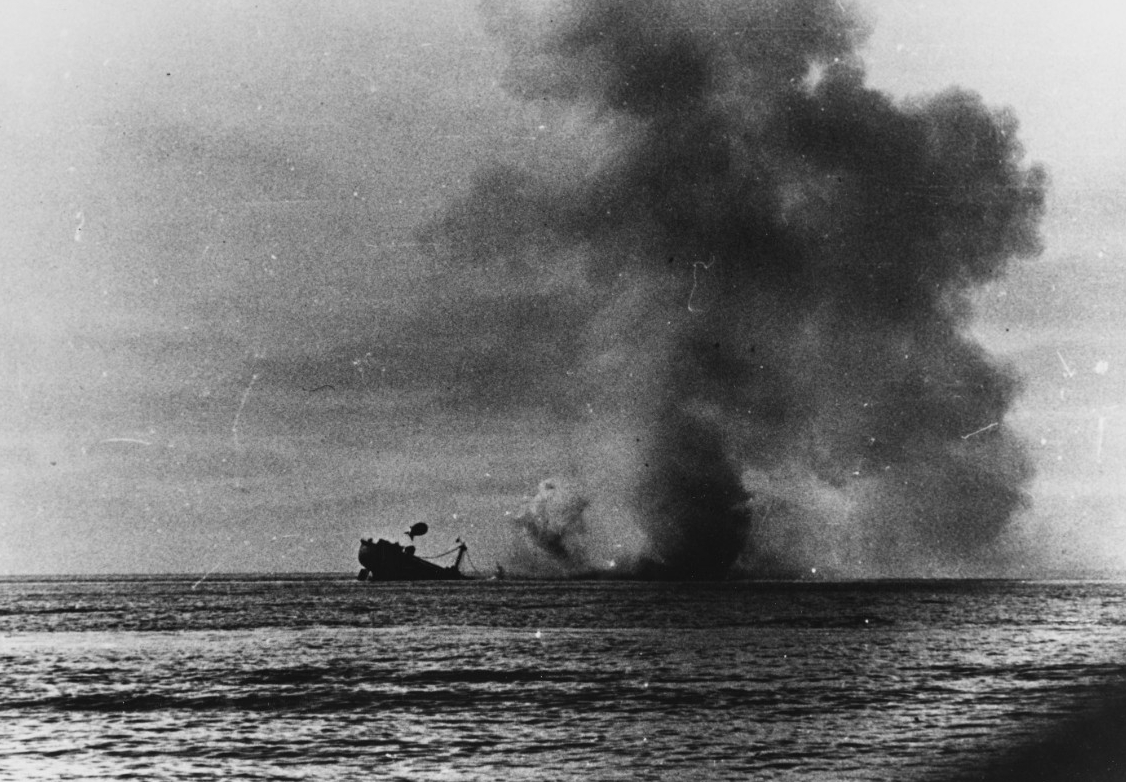

The slaughter had begun about 0830. Soon, frantic distress signals from stricken ships filled the Arctic airways. German bombs and torpedoes sank 12 ships that day, littering the Arctic Ocean with oil slicks and assorted flotsam from tankers and cargo vessels heavily laden with the tools of war.

Washington was carrying more than 600 tons of high explosives when she came under dive-bomber attack. Several hits had set the deck cargo ablaze, and with the flames raging out of control, the order to abandon ship was given. The gun crews loaded into two lifeboats and pulled away from the fiery wreck as fast as they could. When another ship tried to save them, the survivors repeatedly waved off all rescue attempts. They reasoned that they would simply be leaving one target for another and voted to remain adrift. It was their hope that once in the lifeboats they would be ignored by the attacking Germans. Within hours, just as anticipated, they witnessed the sinking of their would-be rescuers, hit by three torpedoes. Rigging sails and rowing in shifts, they reached the Soviet Union after ten freezing days.

The attacks continued for five more days, sending nine more ships to the bottom, along with 150 Sailors and officers, 430 tanks, 210 bombers, and some 100,000 tons of other cargo.

Of the initial 35 ships, only 11 reached Arkhangelsk. The disastrous outcome of the convoy demonstrated the difficulty of passing adequate supplies through the Arctic, especially during the summer period of perpetual daylight. PQ-17 was the first combined Anglo-American naval operation under British command in the war—its tragic outcome caused significant friction between the two Allies and the suspension of further convoys until September 1942. Nonetheless, a total of 78 Arctic convoys successfully transported significant amounts of war materiel to the Soviet Union by the end of the war. The convoys demonstrated the Western Allies' commitment to the Soviet war effort and tied up substantial German naval and air assets.

Read NHHC Historian Mark Evans's essay, "Convoy is to Scatter": Remembering the High Cost of the Arctic Convoys, for more information on arctic convoys.

PQ-17 vignette by Robert J. Schneller, Ph.D., Naval Historical Center, October 2008