The WAVES' 75th Birthday

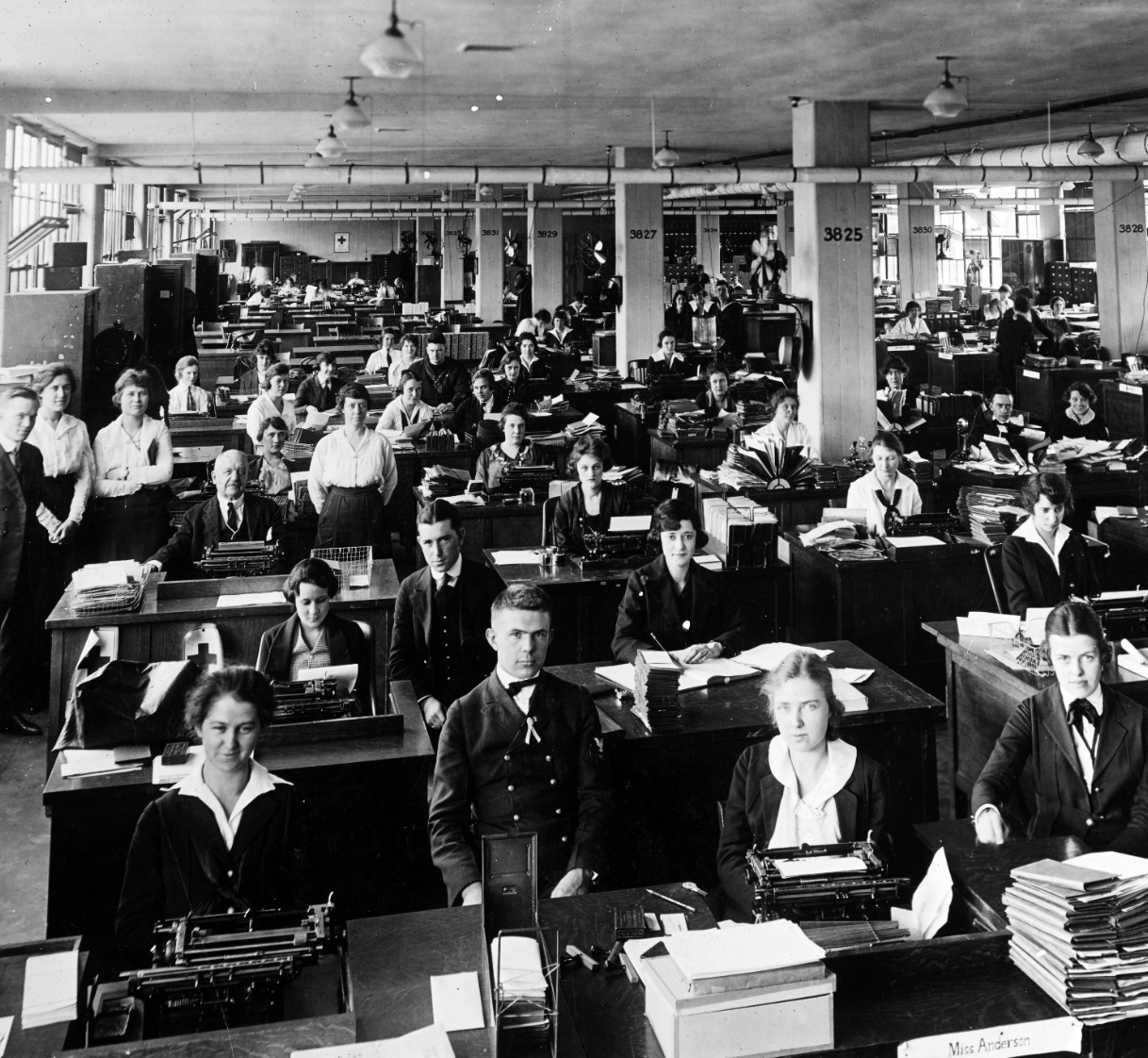

What are the WAVES and why should they be celebrated? If you are like most, many images may come to mind, including actual waves of water. The quick answer is on 30 July 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Public Law 689 creating the women’s reserve as an integral part of the Navy. So what do WAVES have to do with female naval reservists? Why are they important? A more complete answer to these questions necessitates an explanation of their origin, which begins with World War I. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels sought additional workers after learning that the civil service could not meet the need for clerical support. Since the Naval Reserve Act of 1916 read that any U.S. citizen could join, Daniels recruited women. On 17 March 1917, Loretta Perfectus Walsh of Olyphant, Pennsylvania, distinguished herself as the first enlisted woman, forever changing the Navy. More than 11,000 women joined her, working in naval districts across the United States, particularly in Washington, D.C. Patriotism and hoping to end the war sooner were their primary motivations. They also thought their service would persuade President Woodrow Wilson to support the 19th Amendment. A male and a female in the same naval rank earning the same salary meant equal pay for equal work, which appealed to them.

They volunteered to submit to Navy rules and regulations 24 hours a day, 365 days a year and to be assigned wherever the Navy needed them most for four years. After completing an application, an interview, a physical exam, and a business skills test, qualified women took the oath. The shortage of clerical workers was so acute that many started their jobs the same day wearing their civilian clothes. Others went home to await their orders. The Navy recruited mothers and daughters, multiple sisters from one family, several sets of twins, and best friends from across the United States and its territories.

The Navy had a few administrative problems to address. For the first time, Sailors’ gender had to be indicated, so it classified these women as Yeoman (F). Since the Bureau of Navigation—the branch of the Navy responsible for personnel—automatically assigned new Sailors to ships, women were assigned to sunken vessels, unused barges, or docked vessels. Men occupied most of the barracks, so women had to provide their own housing, commuting from home, renting a room in a house, or sharing an apartment. The Navy gave Yeomen (F) a daily subsistence allowance to cover their housing and meals. The Navy did not send them to Great Lakes Naval Training Station but developed a night school for instruction in naval procedures and policies, ship and plane identification, ranks, culture, and customs. Women also mastered marching and drilling after work. Addie Worth Bagley, wife of the Secretary of the Navy, started the Yeoman (F) Battalion to participate in parades and to greet returning ships. The female yeomen eventually received their summer white and dark navy blue winter uniforms that covered them from head to toe.

The Yeomen (F) contributed to the war effort in clerical and non-clerical specialties, such as switchboard operators, stenographers, recruiters, deciphering code, painters, look-outs for naval bases, translators, and messengers. They dispersed pay, designed camouflage for ships, and produced munitions. As Secretary Daniels observed, “They did everything except go to sea.” They became so proficient in their jobs that one of them could replace two Sailors for combat duty. A few supervisors recommended them for officer ranks but Daniels could not permit that without congressional approval. The women reservists encountered resentment from some individuals who questioned the character of any women who enlisted, while other individuals believed the women would render the Navy less efficient. The Yeoman (F) also endured verbal insults and individuals published negative editorials questioning Daniel’s decision to enlist women.

The Navy stopped recruiting on 11 November 1918 but did not demobilize the female yeomen from active duty until 1920, because they had signed up for four years. Moreover, their supervisors urged Daniels to retain their talent after the war by hiring them for civilian positions doing the same job. Many welcomed the opportunity, and several later retired from the Navy Department. Some naysayers and some members of Congress did not believe another war would erupt and, if it did, women would not be needed. Thus, they rewrote the Naval Reserve Act of 1916 to read that “any male citizen could join.” As a further insult, Congress and other military leaders tried to prevent the women from eligibility for the World War I Victory Medal until advocates intervened. Nurses remained the only women in the Navy until 1942.

As war became eminent, congressional and military leaders began making preparations. The War Manpower Commission reported that there were not enough men to support the Navy’s need for personnel ashore and afloat. U.S. Representative Edith Nourse Rogers, from Massachusetts, was among them. During the previous war, she inspected field hospitals as a part of the Women’s Overseas Service League, served as a Red Cross Nurse, and reported on the treatment of veterans. She decided then that if American women served in the military again it would be as full-fledged members receiving the same entitlements as men. Rogers initially presented her sentiments to the Secretary of War. The Army was the first to respond. She cosponsored the bill that Congress passed creating the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in late 1941, which became law on 12 May 1942.

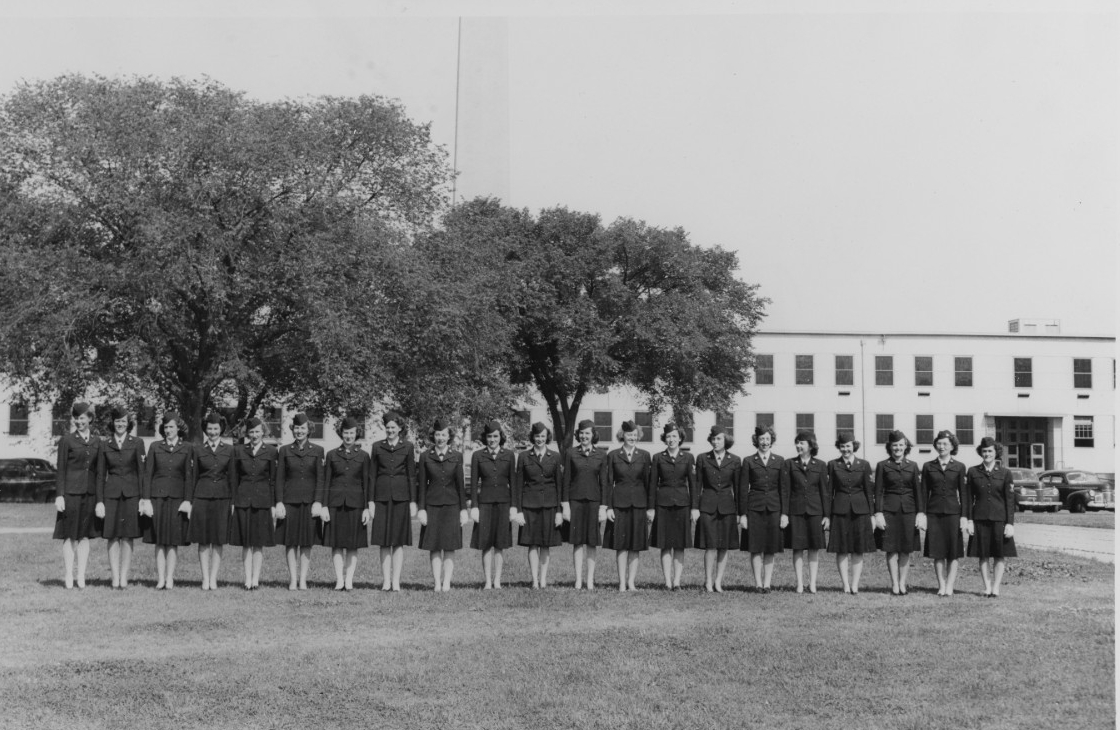

Rogers also approached the Chief of Naval Personnel Chester W. Nimitz who advised her that Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox would have to approve her recommendation. Others pressed Knox to confirm his intentions. Aware of the projected personnel shortages and Rogers’ determination, Nimitz surveyed the Navy Department bureau chiefs to determine how women could be utilized. He received the most positive response from the Chief of Naval Operations, the Bureau of Aeronautics, and Naval Intelligence. Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs succeeded Nimitz and established the Women’s Advisory Council composed of women educators and naval officers to develop a program for women reservists. Knox insisted that if women were going to work with classified or sensitive information, they must be an integral part of the naval reserve—not an auxiliary to it. The council also recommended that women be formally indoctrinated to ensure that they knew naval terms, ranks, ships, aircraft, and customs. They proposed training officer candidates at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. After commissioning a sufficient number of officers, the enlisted recruits began their basic training in Norman, Oklahoma; Cedar Falls, Iowa; and Milledgeville, Georgia. The council recommended Mildred McAfee, president of Wellesley College, to serve as director of the women’s reserve. Despite the emerging need for personnel, congressional and naval leaders opposed women entering the military. Virginia Gildersleeve, a member of the council, recalled that “Now if the Navy could have used dogs or ducks or monkeys, certain of the older admirals would probably have preferred them.”

As they continued planning, council member Elizabeth Reynard began hearing unsavory names for the women (i.e., Sailorettes). This led her to create their official nickname—WAVES, an acronym for Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service. She carefully selected her words to emphasize that they volunteered and it was just for the duration of the war. McAfee benefitted from the lessons-learned by the WAAC director. The Army’s first uniforms did not allow for differences between men and women’s build so they did not fit properly. However, Robert Main Boucher designed the WAVES uniform that remains the basis for the one worn by women in today’s Navy. It was so attractive that some selected the Navy over the other services.

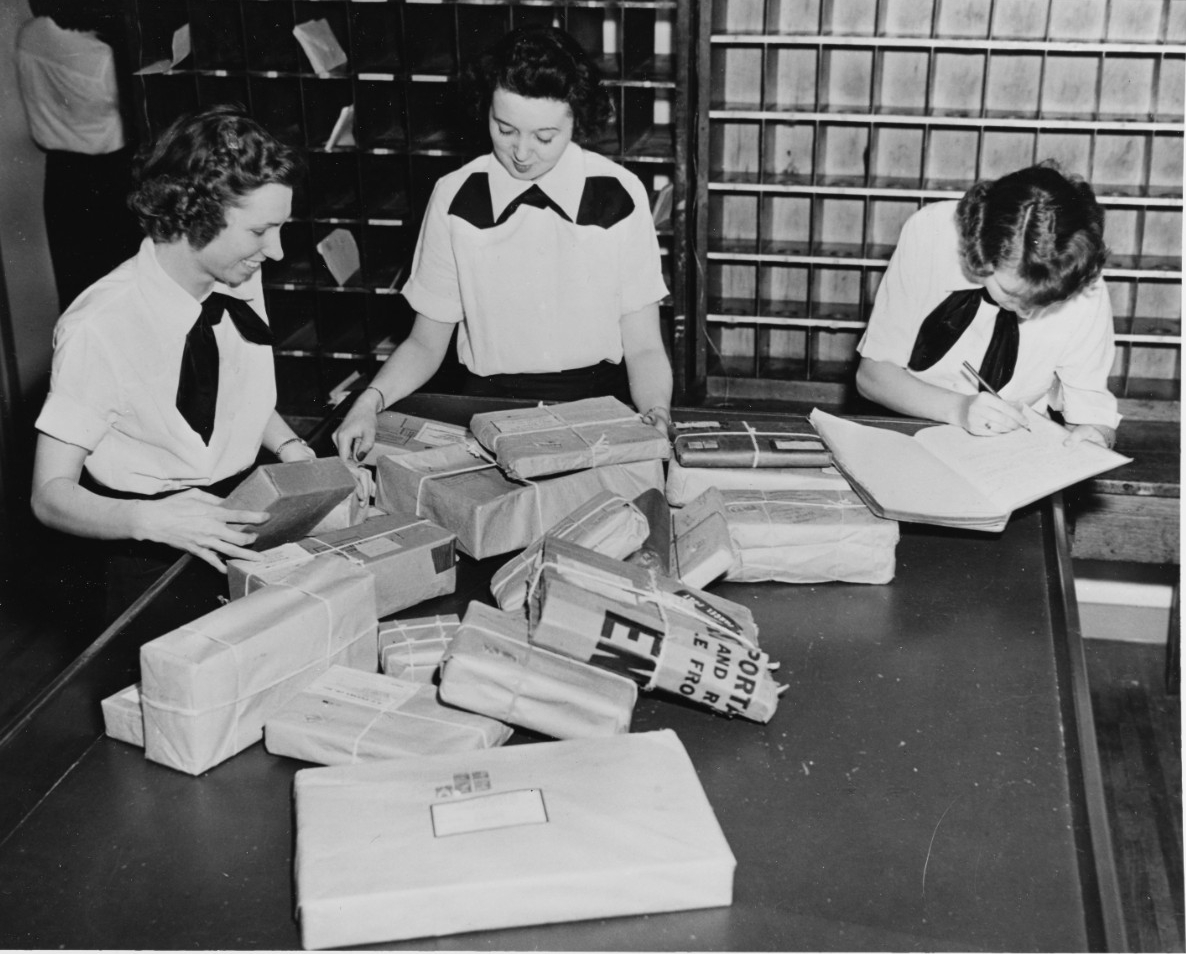

Eventually Congress passed Public Law 689 to establish the women’s reserve as an integral part of the Navy. They had to serve for the duration of the war plus six months. After the legislation sat for several days awaiting the president’s signature, Dean Harriet Elliott, a council member contacted First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Shortly afterwards, the president signed the bill into law on 30 July 1942. Mildred McAfee and her staff trained over 20,000 officers and 70,000 enlisted from urban and rural communities across socio-economic backgrounds. They worked at large and small naval commands from Florida to Washington State and from California to Rhode Island, as well as overseas. Their numerous and diverse contributions ranged from yeoman, chauffeur and baker to pharmacist, artist, and aircraft mechanic.

More than 30 percent of the WAVES worked as naval aviation training pilots, air traffic controllers, and parachute testers. They also excelled as weather specialists, chemists, and lawyers. World War II marked the Navy’s first female doctor, lawyer, bacteriologist, and computer specialist. Grace Hopper helped develop the Mark I computer as a member of a team assigned to the Harvard University Computation Laboratory during World War II.

Director McAfee received verbal and written praise for the critical support provided by the WAVES. On their first anniversary, President Roosevelt commented, “In their first year, the WAVES have proved that they are capable of accepting the highest responsibility in the service of their country.” A year later, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King praised them, “in addition to having earned an excellent reputation as part of the Navy, they have become an inspiration to all hands in the naval uniform.” Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Admiral Nimitz added, “Although history records that women have had influence upon the navies, it is only recently that women have had influence within the navies.” There were times during the war when recruiters could not meet the repeated requests for more WAVES.

There are some significant similarities between the Yeoman (F) and the WAVES. Both forever changed the status of military women. They volunteered; they were not drafted. They helped to dispel myths and stereotypes assigned to women in uniform. They enhanced the legacy of women who supported the nation during previous wars, conflicts, and crises and paved the way for those who followed. Before World War II ended on 2 September 1945, aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, naval and congressional leaders reflecting on the women’s contributions considered granting them a permanent place in the peace time services. After some debate and compromise, Congress passed the Women’s Armed Forces Integration Act on 28 July 1948. That same year President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 mandating equality of treatment for all regardless of race, creed or color. Another similarity is that women of color made up less than a fraction of one percent of the total number of female reservists. There were 14 African American Yeomen (F) among the 11,275 and 2 officers and 70 enlisted WAVES among the 90,000. During both global wars to protect and defend democratic freedoms and values, the Navy reluctantly recruited black women and did so late in the war. The Navy enlisted Japanese, Hispanic, and Native American women before African Americans. Despite the demand for more reservists, the Navy did not make maximum use of all available women.

This brief history explains the origin of the WAVES and the significance of their war service. If given the opportunity, tell others about them. Military personnel and society at large need to know about these outstanding women to better appreciate the opportunities available to women today and the costs of the freedoms they enjoy. All ratings and specialties are open to all qualified women. The Yeoman (F) and the WAVES epitomized the Navy’s core values of duty, honor, and commitment, long before they were adopted. To learn more about these pioneering women see:

Women in the U.S. Navy , Minorities and Women in the Navy , the Historical Overview of the Yeoman F, and the United States Naval Administrative Histories of World War II, Volumes 88a and 88b, which includes the World War II Administrative History on the Women’s Reserve, photographs, documents, bibliographies, and artwork.

—By Regina T. Akers, Ph.D., Historian, Naval History and Heritage Command