H-058-2: Korean War: Communist Chinese Offensive Phase 3 – December 1950–January 1951

H-058.2

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

January 2021

U.S. troops prepare to disembark from USS LSU-1317 at Charley Pier, near Inchon's Tidal Basin, 29 December 1950. Wolmi-Do island is in the background, with Sowolmi-Do island in the left distance. Photographer: AF3 F.O. Furuichi. Note cold weather clothing worn by these men. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. (NH 97079)

Situation in Korea, Late December 1950

The Communist Chinese continued their massive offensive in North Korea in December 1950. In the east, the U.S. Marines conducted their heroic fighting retreat from Chosin Reservoir to Hungnam on the east coast of North Korea. Greatly aided by U.S. Navy close air support from the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF-77) operating in the Sea of Japan, as well as by Marine aircraft from escort carriers and ashore, the Marines inflicted such severe casualties on the Chinese that the Chinese were unable to press the attack against Hungnam until after U.S. Navy forces had evacuated the Marines and the rest of the U.S. Army X Corps and Republic of Korea I Corps. The evacuation was complete by Christmas 1950. (See H-Gram 056.)

The Chinese offensive in the west was even more successful─for the Chinese. Suffering heavy casualties in the Battle of Ch’ongch’on River (25 November–2 December), the U.S. 8th Army and other UN forces narrowly escaped being surrounded and cut off by the Chinese. In what became known as the “Big Bug Out,” the 8th Army essentially retreated faster than the Chinese army could keep up, abandoning much equipment in the process. Morale and combat effectiveness in many 8th Army units was shattered. The Chinese advance was so overwhelming that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of United Nations and U.S. forces in Korea, seriously considered using atomic weapons on the Chinese or completely evacuating the Korean peninsula. What many viewed as an ignominious retreat finally stabilized for a time in late December along the 38th Parallel, the original dividing line between North and South Korea.

On 23 December, the 8th Army commander, Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, was killed when his jeep was hit by an oncoming South Korean weapons carrier. On 26 December, Lieutenant General Mathew Ridgeway assumed command of the 8th Army. The highly effective commander of the 82nd Airborne Division and XVIII Airborne Corps in World War II, Ridgeway would be rightly credited with turning around the sense of defeatism in the 8th Army, but not until after several more defeats.

In late December, the United Nations proposed a truce. Chinese leader Mao Tse-tung, convinced that Chinese troops were invincible after their stunning successes, interpreted the UN offer as a sign of weakness. Against the advice of his senior military commanders, who argued that Chinese logistics lines were already over-extended, Mao ordered another major attack, known as the Chinese Third Phase Offensive or the Chinese New Year’s offensive. Commencing on New Year’s Eve 1950, Chinese forces overran South Korean units on the 38th Parallel, causing the 8th Army to evacuate the South Korean capital of Seoul, which fell to the Chinese on 4 January 1951, the third time in the war that Seoul changed hands. The Chinese attack ran out of steam, partly due to continuing air attacks, and Ridgeway rallied his forces and was able to stabilize the battle line near Suwon, about 19 miles south of Seoul. The Chinese advance along the east coast road also stalled out, due to outrunning their supply lines, which were under constant attack by U.S. Navy carrier aircraft and naval gunfire from ships along the coast.

USS McKean Sinks Soviet Sub? – 18 December 1950

Given the enormous number of confirmed Soviet mines provided to the North Koreans, as well as Russian pilots flying “North Korean” Mig-15s (see H-Gram 056), there was considerable concern among U.S. Navy commanders in the Far East that Soviet submarines were a serious potential threat, especially given the lack of escort ships necessary to adequately protect the long and potentially vulnerable sea lanes across the Pacific. As a result, U.S. Navy rules of engagement permitted immediate attack on any unknown submarine contacts in the vicinity of U.S. forces, and on 23 September 1950, the destroyer McKean (DD-784) had dropped five depth charges on a submerged contact, but with no sign a submarine had been hit. The U.S. estimated that the Soviets had as many as 80 submarines in Vladivostok, on the Sea of Japan. Russian sources claim that only about ten submarines were in operational readiness condition.

On 12 December 1950, the first U.S. dedicated ASW Hunter-Killer Group (TG 96.7) in the Korean theater was stood up, in accordance with Commander Naval Forces Far East (CNFE) Oporder 24-50. TG 96.7 was formed around escort carrier Bairoko (CVE-115), which had arrived in the Korean theater in November after re-commissioning in September. Destroyer Division 32 (DESDIV 32) provided the destroyers and Task Group 96.9 provided submarines to serve as practice targets.

On 18 December 1950, destroyer McKean sank a Soviet submarine off Sasebo, Japan, according to a number of accounts, including the book Blind Man’s Bluff and Wikipedia. I will start with the official accounts, which include the originally top secret report by the commanding officer of McKean, “Report of Sonar Contact and Attacks by USS McKean and USS Frank Knox (DD-742) on a Hulk off Sasebo,” Serial 0001, dated 5 January 1951, as well as the assessment by Commander Destroyer Flotilla ONE, Task Force 95, Commander Naval Forces Far East and Commander-in-Chief Pacific Fleet.

According to McKean’s official report, at 1036 India (local), 18 December 1950, McKean was steaming independently en route a gunnery exercise area off Sasebo when she gained a sonar contact bearing 270(T) at 1,500 yards. The McKean’s experienced ASW officer evaluated the contact as a possible sub based on bright visual echo, sharp audible echo, and high Doppler, on course 145(T) at 7 knots. The target depth was estimated at 150-240 feet at position 3326.2N 12917.0E. The commanding officer (Commander J. C. Weatherwax) was called to the bridge and immediately directed the ship go to General Quarters.

A tractor aircraft for an antiaircraft gunnery exercise reported a possible silhouette in the general location of the sonar contact. The contact information was passed to the Officer in Tactical Command (OTC), the commanding officer of destroyer Frank Knox (DDR-742), who ordered an urgent attack. McKean conducted an attack with an eleven depth charge pattern. The aircraft reported that the silhouette was at center of the pattern, after which the silhouette disappeared and was not sighted again. The aircraft then reported air bubbles and an oil slick, which grew larger. The oil slick was sighted by both McKean and Frank Knox, which joined 20 minutes after the first attack. McKean held contact and vectored Frank Knox onto the contact. Frank Knox obtained contact and concurred in McKean’s evaluation.

The contact plotted dead-in-the-water for 25 minutes, but as Frank Knox made a close approach the contact tracked 025(T) at 3 knots. Frank Knox made an attack and then McKean made a second depth charge attack, but missed as the contact was in a hard left turn. Confusing the picture, during McKean’s first attack, an additional contact was noted 200 yards inside the first, which then merged with the first contact.

After McKean’s second attack, the contact remained dead-in-the-water. McKean and Frank Knox alternated attacks. After McKean’s fourth attack, noises were heard from the direction of the contact evaluated as sonar countermeasures. At about the same time, the aircraft overhead reported a possible torpedo wake. Both ships took evasive action and Frank Knox reported crossing the wake. The wake was visible on the QHB-a (sonar) scope, with a humming noise in the direction of the countermeasures. After evading the possible torpedo, McKean made a fifth attack, after which both McKean and Frank Knox lost contact due to the countermeasure jamming. The jamming gradually decreased and the target was regained in the same location, still dead-in-the-water.

By this time, both McKean and Frank Knox had expended all but three depth charges each. The two ships then alternated “heckler runs” at irregular intervals, dropping one depth charge on each run with no further movement detected. At 1712 local, 18 December, destroyer Taussig (DD-746) arrived on scene and McKean was ordered back to Sasebo for a reload of depth charges. McKean returned the next morning and made three more attacks on the contact, which plotted dead-in-the-water in the same location. (From other reporting, probably accurate, McKean expended 55 depth charges on the first day, received a reload of 94 from destroyer tender Dixie (AD-14), and expended 33 more on the second day.)

On 20 December, the salvage and rescue ship USS Greenlet (ASR-10) arrived, moored over the contact and put a hard-hat diver over the side. The diver reported that the target was a hulk with Iona Maru on stern. Iona Maru had reportedly capsized and sunk on 10 December 1950. McKean’s report stated that the sonar jamming was possibly caused by an unexploded Mk. 14 Mod 0 depth charge employed in the fourth attack. (Mk. 14 was an acoustic depth charge developed during WW2, but too late to be used in action.)

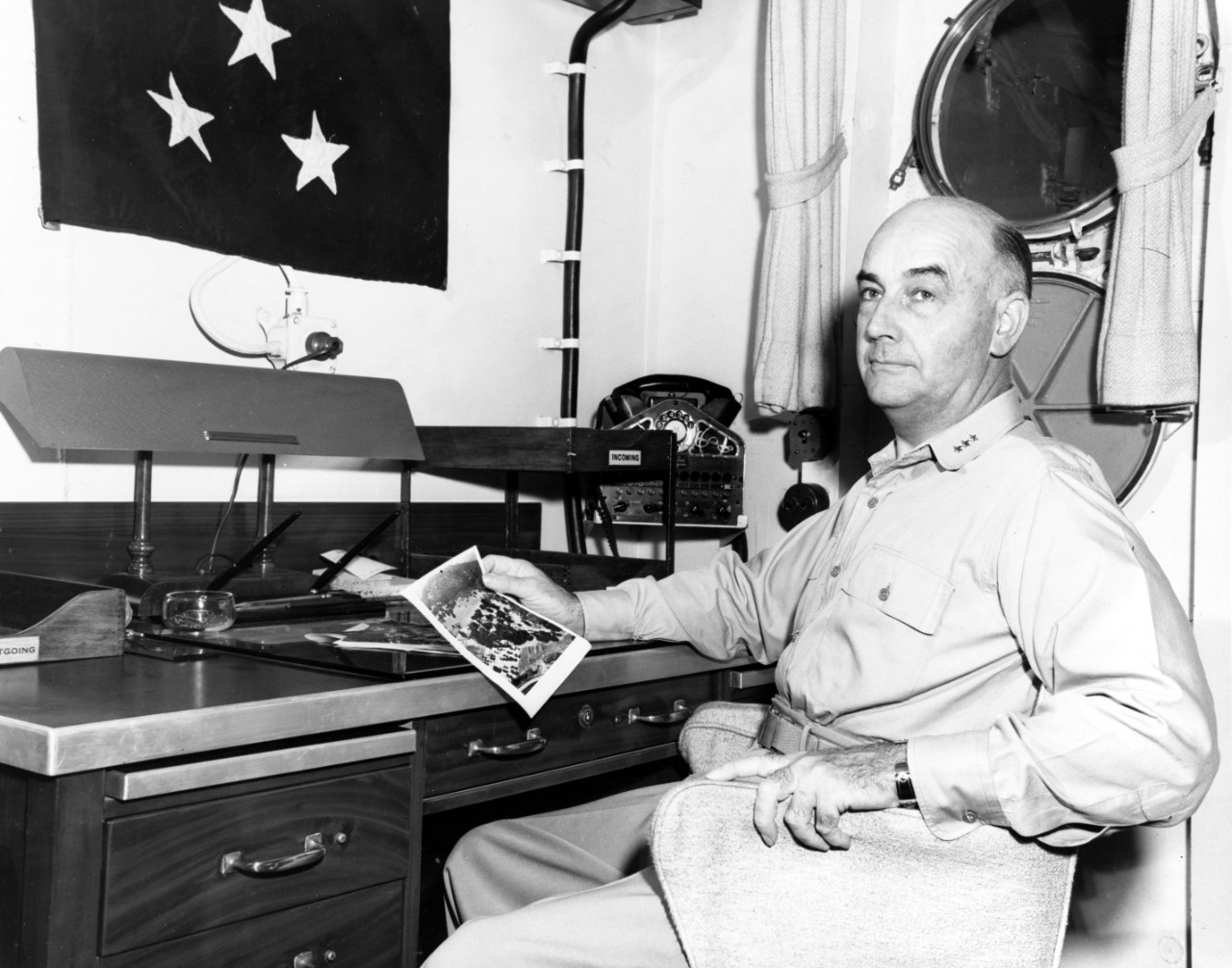

On 19 December 1950, Rear Admiral Kenmore M. McManes (Navy Cross, Battle of Surigao Strait), Commander of Destroyer Flotilla ONE, sent a report evaluating the contact. (COMDESFLOT 1, Serial 0005, 19 December 1950, “Evaluation of Submarine Contact of USS McKean which was Held and Developed by USS Frank Knox, Endicott (DMS-35), and USS Taussig on Probable Submarine.”) In addition to McKean and Frank Knox, the destroyer Taussig and destroyer-minesweeper Endicott had also attacked the contact overnight 18-19 December. McManes’ report included the reporting data from the ships and concluded the contact was a “probable sub.” The “contact was a moving object and that the noises, changes in frequency of these noises, etc., indicated on the tracings, were being manipulated from a moving target which was, more than likely, a submarine. However on the other side of the picture there are no positive indications other than the mechanical ones described above such as floating debris, heavy oil slick, etc. which definitely proves the contact to be a submarine.” After his signature, RADM McManes added “P.S. I have not forgotten the ‘Battle of the Pips’.” (this is a reference to an incident during the Aleutian Islands campaign in July 1943 when U.S. battleships fired over 500 rounds at radar contacts which were probably flocks of birds. See H-Gram 016.) In pen on the report is “final evaluation sunken Jap ship Tom Maru.”

The Commander, UN Blockading and Escort Force (CTF 95) forwarded McKean’s report without comment as did Commander Naval Forces Far East. Commander-in-Chief U.S. Pacific Fleet forwarded McKean’s report to the Chief of Naval Operations on 22 March 1951, signed out by the Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Captain Edwin T. Layton, with the statement “CPF eval is non-submarine.” All these messages were originally classified as top secret due to the sensitivity of attacking a Soviet submarine. (Layton, Intelligence hero of the Battle of Midway, had been a captain since 1943, and would not be promoted to rear admiral until 1953, which sounds slow, although he did go from lieutenant commander to captain in two years.)

In 1998, the book Blind Man’s Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage, was published, including a short passage sourced to two anonymous former intelligence officers that “U.S. Intelligence officials had long believed a U.S. surface ship sank a Soviet submarine that came close to a U.S. carrier force” early in the Korean War. This was followed by multiple accounts claiming McKean sank a Soviet submarine. According to the Wikipedia account, the McKean (call sign “Rancher”) had just left Sasebo to rejoin the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF-77) when she gained hard sonar returns on two submerged contacts. Commander Weatherwax, who had been a submarine officer in WWII, ordered the attack. McKean first sent the international “identify yourself” code (dot dash – letter A) via sonar three times, which was not answered. McKean then attacked the submarine with depth-charges. Commander Weatherwax ordered the word “submarine” struck from the log as that would cause an international incident.

The Wikipedia account then tracks closely with McKean’s official version. However, on the second day (19 December) one of the three aircraft overhead reported a torpedo track, which just missed astern of McKean without being seen by McKean. This was “the other Russian submarine lashing back.” USS Greenlet arrived on the scene and a hard hat diver was lowered and came up with a pair of “new” binoculars. The account then speculates that Greenlet retrieved a “black box” that was the Soviet sonar jammer and possibly code books. Greenlet was then immediately sent to Pearl Harbor and not allowed to return to Korea because her crew knew too much about Soviet secrets. (Greenlet did depart Yokosuka on 6 January 1951 for Pearl Harbor and remained there for the duration of the war.) Although every “B-girl” in Sasebo supposedly knew what happened, McKean’s crew couldn’t talk because they were required to sign secrecy letters, and were informed that the contact was Iona Maru. The account then states, “the Navy brass had already formulated their cover story with the skipper of the Greenlet.” Crewmen on McKean were reportedly incredulous, “We sunk a hulk ship that was doing 5 knots!”

The Russians have only ever admitted to losing one submarine in the Far East in the early 1950s, the M-type S-117 (C-117 in Russian) that went missing in December 1952 due to unknown causes; all others are accounted for, at least officially. No other Russian account has surfaced admitting to losing a submarine in December 1950, or any time, as a result of the Korean War. In fact, those Russian accounts that I can find state that no Russian submarines operated in vicinity of U.S. carrier or surface forces. This would actually be consistent with Soviet rules of engagement during the war, which was to hide the extent of their involvement as much as possible. For example, the Russian pilots flying “North Korean” Mig-15s were forbidden from operating over UN controlled territory, or overwater, for fear a Russian pilot might get captured. The sea mines had the element of “plausible deniability,” which evidence of a sunken submarine would not. The Russians were likely aware of U.S. rules of engagement and had no desire to get one of their submarines sunk for no real purpose. The best Russian source I found was Russian-language, “Korean War. Episodes of the Participation of the Soviet Navy”, by Alexander Rozin (at alerozin.narod.ru/Korea45x53.htm), and the “translate this article” function worked surprisingly well.

There are some lessons from this event. The first is that anti-submarine warfare is really, really hard, even for a crew assessed as well-trained and experienced as the McKean’s. Also, underwater acoustics are really freaky. Third, in any conflict involving submarines, expenditure of ASW weapons on whales and other sea creatures is prodigious and likely to be a serious problem (as the British re-learned in the 1982 Falklands War). Fourth, Blind Man’s Bluff is a really interesting book, but don’t believe everything. Fourth, Wikipedia is a very useful tool, but don’t believe everything there either. Maybe McKean sank a Soviet sub and Russian and U.S. official sources are all lying, but probably not. See, isn’t history fun?

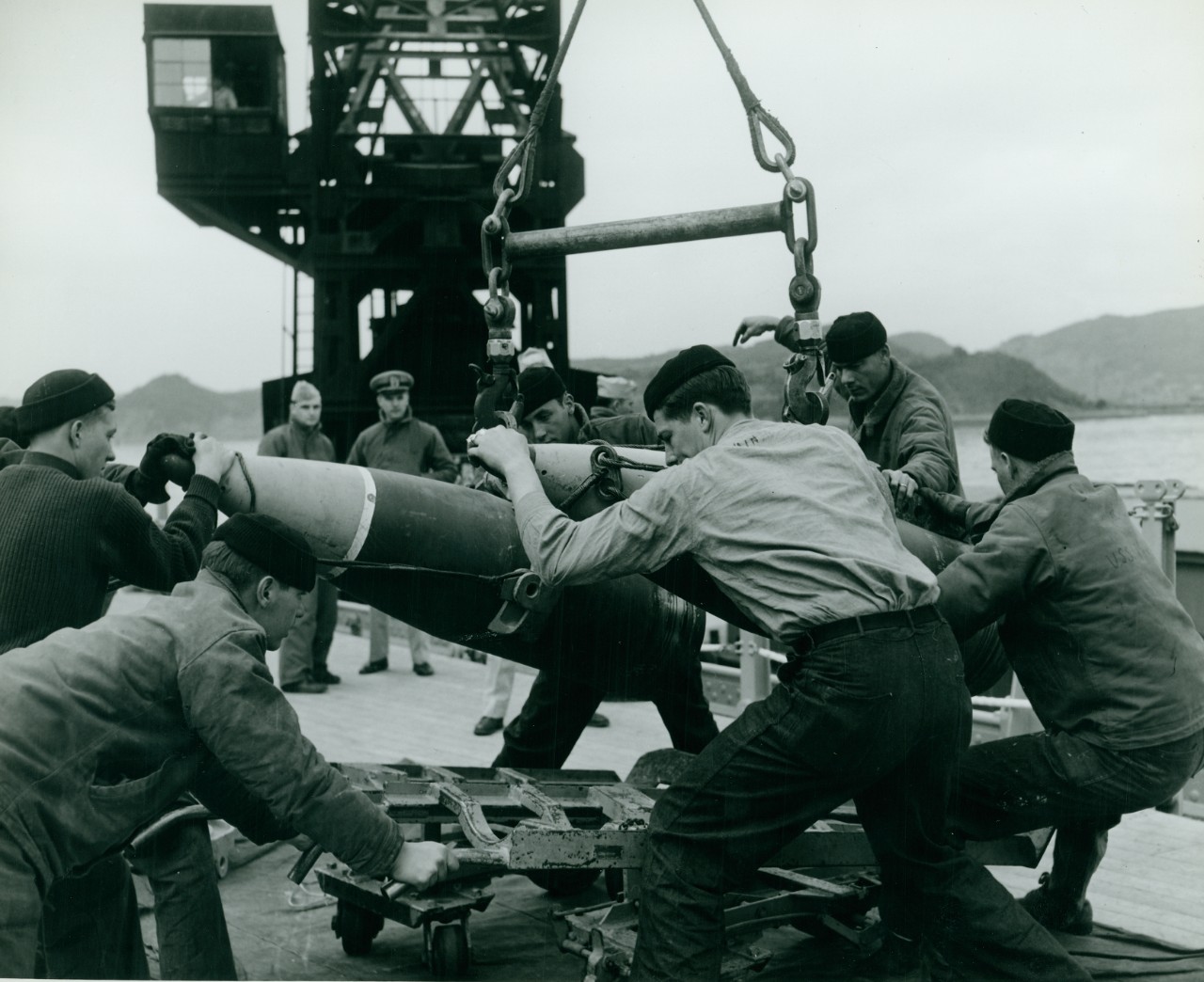

Port facilities at Inchon, South Korea, are destroyed as UN forces evacuate the city in the face of the Chinese Communist advance. Photograph is dated 4 January 1951. The final evacuation of Inchon took place on 5 January. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (80-G-425472)

Evacuation of Inchon – January 1951

In anticipation of continued Chinese offensive action in western South Korea, the escort carriers Sicily and Badoeng Strait, with Marine aircraft embarked, entered the Yellow Sea and relieved British carrier Theseus on 27 December 1950 providing support to the U.S. 8th Army. Two days later, heavy cruiser Rochester (CA-124), with RADM Roscoe H. Hillenkoeter embarked as Commander Task Element CTE 90.12, arrived at Inchon to join with HMS Ceylon and Australian destroyers HMAS Warramunga and Bataan to cover UN forces at Inchon. Two days after that, the “Third Phase” Chinese offensive commenced on New Year’s Eve and 8th Army fell back to more defensible positions south the Seoul. The 8th Army plan was to fall back via road rather than by sea, but there was still considerable equipment and supplies to get out via Inchon. Nevertheless, U.S. Navy forces were waiting off Inchon with the capacity to evacuate 135,000 men if that became necessary.

The evacuation force was under the command of Rear Admiral Lyman A. Thackrey, Commander Amphibious Group THREE/Task Group 90.1. RADM Thackrey’s assets included his flagship Eldorado (AGC-11), one attack cargo ship (AKA), two attack transports (APA), two landing ship dock (LSD), one fast transport (APD), two U.S. Navy LSTs, and nine Japanese-manned (Scajap) LSTs. In addition 15 Victory Ship transports were being held in reserve in Japan. As it turned out, the U.S. ships took out 69,000 military personnel, more than 1,300 vehicles, plus over 60,000 tons of cargo, plus 64,200 Korean nationals.

On 5 January 1951, RADM Thackrey sortied all his ships as the Chinese approached and the Inchon port facilities were blown. This demolition would prove somewhat short-sighted given UN control of the sea around the Korean Peninsula–the Chinese weren’t going to be able to use the port anyway, and this left Pusan as the only high-capacity port on the Korean Peninsula. RADM Thackrey’s ships completed the move of U.S. Army and UN units from Inchon to Taechon, further down the west coast of South Korea, between 7 and 12 January 1951. Taechon was a relatively undeveloped port that required considerable innovation and support from the ships in order to be useable.

On 7 January, the light carrier Bataan (CVL-29), with Navy aircraft, joined escort carriers Sicily (CVE-118) and Badoeng Strait (CVE-116) in the Yellow Sea striking Chinese troop concentrations and supply lines. Rochester (CA-124) and HMS Kenya and HMS Ceylon bombarded Chinese positions on the west coast. On the east coast, carriers Philippine Sea (CV-47) and Leyte (CV-32) joined Valley Forge (CV-45) in striking advancing Chinese forces, while Princeton (CV-37) came off line to Sasebo for upkeep. Foul weather and high winds adversely affected the carrier strikes, which nonetheless continued in brutally cold temperatures.

From 6-10 January, heavy snow precluded all carrier strikes, and on 10 January the weather was so bad that all land-based aircraft on the entire Korean peninsula were grounded. The U.S. Air Force had already been forced out of the airfields near Seoul by the Chinese advance. The Chinese took advantage of the weather to press their offensive in the central area of South Korea. The 1st Marine Division, which had been held in reserve after being evacuated from Hungnam, was once again thrown into the breech to stop the Chinese advance, aided by clearing weather and heavy carrier strikes on 11 January.

Nevertheless, the situation was once again perceived to be so dire that General MacArthur assessed that without massive reinforcement and expansion of the war (into China) the Korean Peninsula could not be held and that UN forces should be evacuated. The Joint Chiefs of Staff reluctantly accepted MacArthur’s view that a protracted defense of the Korean Peninsula was not feasible. The United Nations once again proposed a cease-fire, but the emboldened Chinese only upped the ante, demanding admission to the United Nations (in place of the Nationalist Chinese on Formosa) and that commencement of negotiations on Korea precede any cease-fire.

However, at this critical juncture, the Chinese had outrun their supply lines. On 16 January, a reconnaissance in force by General Ridgeway’s forces met surprisingly little resistance, and by 25 January the 8th Army was advancing all the way to the Han River (although Seoul was not re-captured until mid-March). In the next months, the front largely stabilized near the 38th Parallel and although there would be a number of bloody pitched battles there would be little in the way of significant movement of the front for the duration of the war.

Thorin, D.W., APC, prepares to take off in his helicopter with another load of survivors from the Thailand corvette, the HMTS Prasae, which ran aground during a blinding snow storm off the coast of Korea. Other members of the helicopters stand guard as the rescue was affected behind enemy lines. (NH 97164)

Loss of HTMS Prasae – January 1951

Thailand was the first Asian nation to join the United Nations coalition for the defense of South Korea and sent two frigates to participate, HTMS (His Thai Majesty’s Ship) Prasae and her sister ship HTMS Bangpakong, which arrived in early November 1950. Prasae was a British Flower-class corvette (1 x 4-inch gun) completed in 1945, serving briefly with the Royal Indian Navy as HMIS Sind, before being returned to the British in 1946 and sold to Thailand in 1947. In January 1951, Prasae and Bangpakong were participating with the East Coast Blockading and Patrol Task Group (TG 95.2) shelling targets on the east coast of Korea near the 38th Parallel, then about 65 miles behind Chinese forward lines.

On 7 January 1951, blinded by a heavy snowstorm, Prasae suffered a radar equipment malfunction and ran hard aground on the beach. When the weather cleared somewhat, several U.S. ships took station in the vicinity to hold at bay any Chinese attempt to reach Prasae and suppressed distant enemy shelling. Bangpakong approached as closely as possible and tried to send eleven men in a boat with ropes, but six men were washed overboard and one drowned. Attempts by a U.S. tugboat to tow Prasae off the beach later in the day were also unsuccessful. Boats from Prasae also attempted to pull Prasae off the beach without success, and a helo off destroyer-minesweeper Endicott rescued three Thai sailors after they were washed overboard from one of the pulling boats. Endicott’s doctor and chief corpsman also went ashore to care for casualties until they could be evacuated.

On 8 January, a Sikorsky H03S1 of Helicopter Utility Squadron TWO (HU-2) embarked on carrier Valley Forge maneuvered near Prasae when a rogue wave caused the ship to roll. The helicopter’s rotors hit the mast, causing the mast to collapse and the helicopter to crash in flames, which then ignited 20mm shells causing more damage to the ship. The crew put the fire out in under 30 minutes. Somewhat miraculously, the helicopter pilot, Lieutenant (junior grade) John W. Thornton, his aircrewman, and a salvage officer, all survived the crash, but another Thai sailor drowned. The Chinese claimed to hit Prasae with shore battery fire, but it was actually the helo crash.

Over the next two days the storm intensified. Seawater contaminated the engine oil, causing the engine to die and then freeze. By 10 January, the sailors on Prasae were without heat, light, or drinking water as temperatures dropped to minus 16 degrees. On 12 January the medical officer of light cruiser Manchester (CL-83) was flown on board, and determined that the conditions were too severe for the crew to remain on board. The same day, a small enemy patrol was driven off by gunfire from the watch.

Once it was determined Prasae could not be saved, and the seas made boat transfer too dangerous, the crew of Prasae was evacuated by helicopter. An H03S1, flown by enlisted pilot Chief Aviation Structural Mechanic ADC(AP) Duane “Wilbur” Thorin of HU-1, embarked on Manchester, rescued 118 crewmen in 40 sorties over a three day period from 12-14 January. (The “(AP)” designated enlisted pilot after the rating, sometime also abbreviated as “NAP.”) Thorin’s Distinguished Flying Cross citation states he was operating from Rochester, which had already left the area, and evacuated 126 men, stating “at great personal risk, he made repeated flights to evacuate injured personnel, furnish food and clothing and to pass salvage lines.” The discrepancy in numbers is probably due to round trips by U.S. personnel to assist.

Thorin had enlisted in the Navy in 1939 and became an enlisted pilot, serving as a test pilot for all types of carrier aircraft during World War II. After flying Navy transports for a couple years and serving as an instructor pilot, he transferred to helicopters in 1949. Thorin made over 130 rescues in hostile territory before his helicopter crashed under fire during an attempted rescue in February 1952 and he was captured. He escaped from a POW camp in July 1952 but was recaptured. He was awarded a Silver Star and two more DFCs for his rescues. With his trademark green scarf, he was the inspiration for the fictitious Chief Petty Officer (NAP) Mike Forney in James Michener’s book, The Bridges at Toko-Ri, played by Mickey Rooney in the movie adaptation. Thorin was commissioned after the war and served as an analyst at the National Security Agency.

LTJG Thornton survived the crash and continued to fly rescue missions behind enemy lines until he, too, crashed under heavy fire after volunteering for a dangerous rescue mission on 31 March 1951 (for which he was awarded a Navy Cross). He was the first Navy helicopter pilot to be captured during the war and the last POW to be released alive, after the armistice in 1953. Thornton eventually retired from the Navy as a captain.

After the evacuation of her crew, Prasae was destroyed by gunfire from U.S. Navy ships on 14 January 1951 before the Chinese could reach her. In October 1951, the U.S. transferred the patrol frigate USS Gallup (PF-47) to the Thai Navy and she was renamed Prasae. Gallup had served in the Pacific during World War II, before she was transferred to the Soviet Union in August 1945 under the Project Hula lend-lease program via the U.S.-Soviet training program in the Aleutian Islands. Serving in the Soviet Navy as EK-22, she arrived too late to participate in Soviet action against Japan at the end of World War II and it took until 1949 for the U.S. to get her back from the Soviets. The second Prasae returned to Korea to serve with UN forces and remained in service until 2000 when she became a museum ship in Thailand. (My thanks to Captain Tom Phillips, USN (Ret.) for some of his research on this incident.)

Navy Operations Late January 1951

With the emergency situation stabilized in mid-January, Marine squadron VMF-323 debarked Badoeng Stait and VMF-214 debarked Sicily for Japan and then re-deployed to land bases in South Korea, where much to the Marines’ displeasure they were essentially integrated into the 5th Air Force. The two escort carriers then returned to the U.S. Marines on the ground no longer had direct support from their own aircraft, but had to rely on whatever aircraft the 5th Air Force chose to send. The 1st Marine Division was also essentially integrated into the 8th Army and used as just another infantry division, making any further major amphibious landings impractical.

On 17 January 1951, light carrier Bataan with Destroyer Division 72 relieved HMS Theseus and screen as CTE 95.11 in the Yellow Sea. Theseus and Bataan would alternate duty for the next months. Two days later, Leyte detached from TF-77 and returned to Japan and then back to the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, having been deployed to the Korean theater since September (after being yanked off a Mediterranean deployment).

On 19 January, the fast transport Horace A. Bass (APD-124) had landed elements of Underwater Demolition Team ONE (UDT-1) conducting hydrographic survey on the west coast of South Korea well south of the battle lines when they were ambushed by men in civilian clothes and concealed weapons. Two UDT were killed and five wounded. Horace A. Bass departed for the U.S. on 28 January with a Navy Unit Commendation for her UDT work at Inchon, Wonsan and the east coast of North Korea.

On 20 January, the Amphibious Task Force (TF 90), still under the command RADM James H. Doyle, was tasked to lift thousands of enemy prisoners of war and civilian refugees to several offshore islands. On 24 January, the Commander U.S. Pacific Fleet (Admiral Arthur W. Radford), Commander Naval Forces Far East (VADM C. Turner Joy), and Commander U.S. SEVENTH Fleet (VADM Arthur D. Struble) all arrived at Pusan, South Korea, and embarked on RADM Doyle’s flagship Mount Mckinley (AGC-7) for RADM Doyle’s change of command with RADM Ingolf N. Kiland as Commander Amphibious Forces Far East (TF 90.) Having commanded the massive amphibious operations during the defense of the Pusan Perimeter, landings at Inchon, landings at Wonsan, and the evacuation of Hungnam, Doyle was awarded a richly-deserved Navy Distinguished Service Medal to go with his Silver Star from Inchon. He retired in 1953 and was advanced to vice admiral due to his World War II combat service (known as a “tombstone promotion.”)

On 29 January, Task Force 77 commenced what would be its primary mission over the next months, the interdiction of bridges and tunnels in the eastern half of North Korea, including the northeastern area near the Soviet Union. These targets would prove hard to hit with the weapons of the time and even harder to inflict lasting damage. Most would be quickly repaired and were increasingly defended with numerous antiaircraft weapons, including radar-directed AAA, making the missions increasingly hazardous and increasingly viewed by the pilots as futile. Nevertheless, extraordinary innovation and valor was displayed by Navy carrier pilots in this campaign, which I will cover in more detail in a future H-Gram.

With the Chinese offensive halted, UN forces began a methodical advance back towards the 38th Parallel, aided by a deception operation known as Operation Ascendant, under the command of CTF 95, RADM Allen E. Smith. RADM Smith “borrowed” two attack cargo ships (AKA), two LSTs and two LSMR “Rocket Ships” from the Amphibious Force and sailed in his flagship, the destroyer tender Dixie and several gunnery ships to a point on the east coast of Korea, 50 miles behind Chinese lines at Kansong. At 0700 on 30 January, the battleship Missouri (BB-63) opened fire, joined by light cruiser Manchester and several destroyers in a sustained bombardment. During the day, the minesweepers, landing craft and rocket ships conducted a very realistic feint. On the next morning, the force reappeared and did it all over again. How much this fooled the Chinese is unknown. However, Dixie fired 204 rounds, which may constitute the only shore bombardment by a destroyer-tender.

Another diversionary operation took place on the west coast of Korea in the vicinity of Inchon. U.S. heavy cruiser Saint Paul (CA-73) was fired on by enemy shore batteries near Inchon, but gunfire from Saint Paul, HMS Ceylon, and several destroyers, along with air strikes from HMS Theseus, neutralized the artillery batteries. On 6 February, Missouri transited around the Korean Peninsula and on 8 February opened fire on targets around Inchon. Two attack cargo ships and an LSD simulated pre-landing operations. A major demonstration by two transport divisions was planned for high tide on 10 February, but was cancelled when the Chinese pulled out of Inchon before being cut off by the 8th Army, which was advancing faster than anticipated toward Seoul.

Crewmen load 16-inch projectiles aboard Missouri in preparation for further Korean War bombardment operations. Photo is dated 14 February 1951, a day when Missouri was at Inchon, Korea. Note shell carts, used to move the projectiles on the battleship's upper deck. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. (NH 96784)

The Siege of Wonsan

Throughout January, the minesweeper force was busy clearing lanes all along the east coast of Korea for use by ships to bombard enemy positions. The mine force had grown to 13 wooden-hulled AMS, but only two of the larger AM (after Pirate (AM-275) and Pledge (AM-277) had been sunk at Wonsan in October). The work continued to be extremely dangerous as the force worked its way northward for the impending blockade of Wonsan.

On 2 February 1951, minesweeper USS Partridge (AMS-31) was clearing a channel for naval gunfire support ships off Sokcho, just north of the 38th Parallel. A mine popped up from behind the minesweeper ahead of Partridge. With no time to evade, Partridge struck the mine and quickly sank in less than ten minutes. Eight crewmen were killed, including the Commanding Officer Lieutenant (junior grade) Boyers “Morgan” Clark, Jr. Two Japanese mess boys were also killed and six crewmen were wounded of the twenty survivors. Engineman 1/C William D. Haines and Yeoman 3/C Robert E. Shewmaker were each awarded Silver Stars for their heroic efforts to save other crewmen during the sinking. Partridge was the fourth U.S. minesweeper sunk in the Korean War, of seven total (one South Korean and two Japanese contract minesweepers). (Of note, junior officer William McGonagle had served as assistant engineering officer on Partridge until he transferred to Kite (AMS-22) as executive officer. McGonagle would be awarded a Medal of Honor in command of intelligence collection ship USS Liberty (AGTR-5) when she was attacked and severely damaged by Israeli aircraft and torpedo boats in June 1967.)

On 16 February 1951, UN naval forces commenced a blockade of the North Korean port of Wonsan (also known as the “Siege of Wonsan.”) Lasting 861 days until the armistice in 1953, this was the longest naval blockade in modern history. Besides being a major port on the east coast of North Korea, Wonsan was also a logistics chokepoint for rail and road networks in eastern North Korea. Besides closing the port to outside reinforcement, UN forces commenced near daily gunfire missions on 17 February against the shore logistics hub, causing heavy damage. Numerous U.S. ships would be hit by shore battery fire in constant duels over the next three years, but none would be sunk. However, several more U.S. ships more would be badly damaged by mines.

On 19 February 1951, destroyer USS Ozbourn (DD-846) took two direct hits and several near misses from enemy shore batteries near Wonsan, North Korea. Despite the hits, Ozbourn remained on the firing line and sent her whaleboat 14 miles into a minefield to rescue a downed pilot from carrier Valley Forge. The boat officer was awarded a Bronze Star with Combat V. (Ozbourne was again hit by shore battery fire off Vietnam in March and December 1967 but continued her mission each time.)

On 24 February, Republic of Korea Marines captured the undefended island of Sindo-Ri in Wonsan, with the assistance of two U.S. destroyers and two patrol frigates.

The Korean War will continue in future H-Grams.

Sources include: Such Men as These: The Story of the Navy Pilots Who Flew the Deadly Skies Over Korea, by David Sears: Da Capo Press, 2010. Attack from the Sky: Naval Air Operations in the Korean War, by Richard C. Knott: Naval Historical Center, 2002. United States Naval Aviation, 1910-2010, Vol. I, chronology by Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015. “Naval Battles of the Korean War,” by Edward J. Marolda, at history.navy.mil. History of United States Naval Operations: Korea, by James A. Field: U.S. Navy History Division, 1962. “Thai Naval Operations in the Korean War” at GlobalSecurity.org