H-033-4: 50th Anniversary of the First Moon Landing

I expect there will be numerous articles in the press regarding the 50th anniversary of the landing on the moon by Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin in the “Eagle” lunar excursion module (LEM) of Apollo 11. So, this H-gram will focus on the Navy service of Neil Armstrong and the Navy’s role in the recovery of U.S. manned space flight missions.

Beginning in 1947, Neil Armstrong began studying aeronautical engineering at Purdue University, with his tuition paid for by the U.S. Navy under what was known as the “Holloway plan.” Under the terms of the plan, which was created in 1946, selected students in the aviation program would study for two years, then take two years of U.S. Navy flight training, followed by one year of naval service, and then would go back to college to finish their degree, followed by a three-year commitment in the Navy Reserve. The program was separate from the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) program, but would evolve into the modern NROTC program.

The Holloway plan was named after its founder, Admiral (then Rear Admiral) James Lemuel Holloway, Jr. (father of CNO James L. Holloway III). The Holloway Plan was quite controversial, especially among U.S. Naval Academy graduates, who generally viewed it with disdain, with the mantra, “Did you get your commission the hard way or the Holloway?” Nevertheless, the program proved highly popular, and Holloway (USNA ’18) would get a last laugh when he became the 35th superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy in 1947.

In January 1949, Armstrong commenced flight training at Pensacola, with the rank of midshipman; his flight grades were about average. He soloed on 9 September 1949 and made his first carrier landing on the training carrier Cabot (AVT-3, formerly CVL-28) on 2 March 1950. He then received training at Corpus Christi in the Grumman F8F Bearcat fighter with a recovery on USS Wright (CVL-49) and was qualified as a naval aviator on 23 August 1950 (the Korean War broke out in June 1950) Armstrong’s initial assignment was Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron 7 (FASRON 7) at Naval Air Station San Diego (now North Island). On 27 November 1950, he was assigned to Fighter Squadron 51 (VF-51) flying the F9F Panther straight-wing jet fighter. Armstrong was the youngest pilot in the squadron. He was promoted to ensign on 5 June 1951.

On 28 June 1951, the carrier USS Essex (CVA-9) commenced a deployment to Korea for combat operations. VF-51 flew ahead to NAS Barbers Point for ground-attack training before embarking on Essex in July 1951. On 29 August 1951, Armstrong flew his first combat mission as an escort for a photo-reconnaissance plane to Songjin, North Korea.

On 5 September 1951, Armstrong was flying an armed reconnaissance mission in an F9F-3 (BuNo. 125122) over transportation and storage facilities west of Wonson, North Korea. There are several versions of what happened on this mission. Armstrong would later relate that he was conducting a low-altitude bombing pass when six feet of his right wing was torn off when he struck a cable strung between the hilltops. According to Armstrong, there was heavy anti-aircraft fire in the area, but he was not hit. However, the initial report to the commanding officer of Essex stated the plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire, and while trying to regain control, Armstrong hit a pole. Other accounts differ on how low Armstrong was flying and how much of his wing was torn off. Armstrong flew his crippled plane (missing an aileron) out over water so that when he ejected he could be picked up by helicopter from U.S. ships. However, after he ejected, the wind blew his parachute back over land, in friendly territory, where he was recovered.

Armstrong flew 78 missions over Korea, most in January 1952, with his last mission on 5 March 1952. He was awarded three Air Medals. During this deployment, Essex lost 26 pilots and aircrew (out of 492 U.S. Navy personnel killed during the war). While still aboard Essex, Armstrong’s regular commission terminated and he became an ensign in the Navy Reserve. When Essex returned from deployment in May 1952, Armstrong was reassigned to transport squadron 52 (VR-52) until he was released from active duty on 23 August 1952.

Armstrong returned to his studies at Purdue, graduating in 1955, but he remained active in the Navy Reserve, flying with Fighter Squadron 724 at NAS Glenview, Illinois. He was promoted to Lieutenant (Junior Grade) on 9 May 1953. After graduating, Armstrong moved to California and flew with Fighter Squadron 773 at NAS Los Alamitos until he resigned his commission on 21 October 1960. By this time, he was already a test pilot for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (precursor to NASA) High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base, California. During his time in the Navy, Armstrong logged 2,600 flight hours, including 1,100 in jet aircraft.

Gemini VIII

Armstrong was the command pilot of Gemini VIII, with David Scott as pilot, launched on 16 March 1966. Since Armstrong had resigned his Navy commission, he thus became the first American civilian to fly in space. The mission successfully conducted the first docking of two spacecraft in orbit (with an unmanned Agena target vehicle), but then suffered a critical system failure that required an immediate abort, the first time such a failure threatened the lives of U.S. astronauts in space. Although planned to splashdown in the Atlantic, the re-entry had to be altered due to the emergency and the splashdown point was shifted to an alternate site 430 nautical miles east of Okinawa on 17 March 1966. Three para-rescuers jumped from a C-54 aircraft and attached a floatation collar until the USS Leonard F. Mason (DD-852), which had been fitted with quarantine capability, reached the scene three hours later. The destroyer then returned to gunfire-support duty off Vietnam after disembarking the astronauts and para-rescuers in Okinawa.

Apollo 11

Armstrong was the mission commander for Apollo 11. Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin was the lunar excursion module (“Eagle”) pilot, and Michael Collins was the command module (“Columbia”) pilot. Aldrin and Collins were both U.S. Air Force officers. Apollo 11 was launched from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida atop a massive Saturn V rocket on 16 July 1969. The lunar excursion module, with Armstrong and Aldrin aboard and Collins orbiting overhead, touched down on the lunar surface at 1517 Eastern Standard Time on 20 July 1969 at a point technically designated “Eagle Base” in the “Sea of Tranquility.” However, after completing the post-landing checklist, Armstrong announced “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

At 2356 (Eastern) on 20 July 1969, Neal Armstrong first set foot on the moon. (I watched it with a crowd of people gathered around some guy who had the foresight to bring a portable TV to Big Meadows campground in Shenandoah National Park that just barely got reception.) Neal Armstrong’s words would result in decades of debate as to whether he forgot to say “a” before “man” or whether the “a” was garbled by static. What everyone heard was, “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.” The official transcript has it as “That’s one small step for [a] man. One giant leap for mankind.” Regardless, the mission was far more dangerous than it appeared, and had more close calls than were publicized at the time, so I’m not about to quibble over an “a.” The man was a hero.

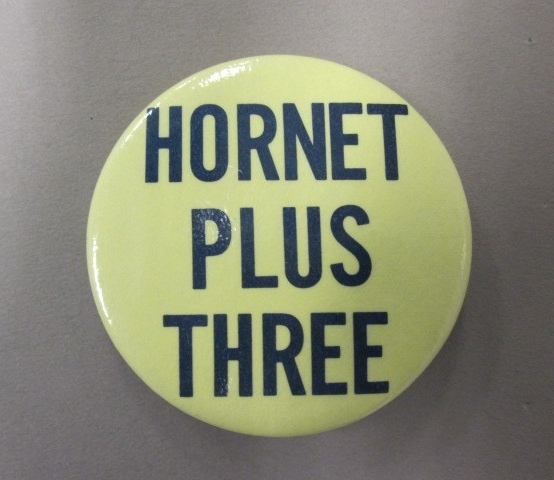

On 5 June 1969, the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CVS-12), under the command of Captain Carl J. Seiberlich, was selected as the primary recovery ship. Arriving at Pearl Harbor from Alameda on 5 July, Hornet embarked HS-4 SH-3 Sea King helicopters that specialized in Apollo recovery missions, specialized divers of UDT Detachment Apollo, a NASA recovery team (35 men), and about 120 press and TV personnel, as well as a “practice” Apollo command module. Most of Hornet’s air wing was put ashore to make room.

On 12 July 1969, Hornet sailed from Pearl Harbor and headed for the planned splashdown site about 1,100 miles southwest of Oahu. President Nixon and an entourage that included Secretary of State William P. Rogers and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger flew on Air Force One to Johnston Atoll, and then on Marine One to the command ship USS Arlington (AGMR-2, a converted light carrier). The next day, the party took the helicopter to Hornet to be greeted by the commander in chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC) Admiral John S. McCain, Jr.

The location of the recovery was subsequently moved 215 nautical miles northeast of the planned point based on imagery from top secret intelligence satellites that indicated a weather front was moving in, which would significantly affect the planned recovery point. (There were only a handful of weather satellites at that time). This change necessitated an alteration to the reentry flight parameters, subjecting the astronauts to greater than planned g-force deceleration. Compounding the problem, the ship suffered a casualty with her navigation equipment forcing a reliance on celestial navigation, which with the overcast was problematic. The upshot was that Hornet knew she was in the general area of the planned splashdown, but did not know precisely where she was.

Prior to sunrise in 24 June, Hornet launched four Sea King helicopters and three Grumman E-1 Tracer airborne early warning aircraft of VAW-111. Two of the E-1s provided radar coverage and the third provided airborne communications relay. One of the E-1s had a radar problem and the communications relay aircraft had to assume that task. Two of the SH-3s carried recovery equipment and divers. The third SH-3 carried photo and movie cameras, and the fourth carried a special decontamination diver and a flight surgeon.

At 0544 local time, the helicopters spotted Columbia’s drogue parachutes deploy only 1,000 feet from the E-1, which had to turn away to avoid the capsule. Seven minutes later, Columbia hit the water 13 nautical miles from Hornet and flipped upside down, but was righted when the astronauts deployed the flotation bags. The divers from the SH-3s quickly attached a sea anchor and additional flotation collars, and deployed rafts. The divers provided biological isolation garments to the astronauts and helped them into a life raft. The astronauts were rubbed down with a chemical solution intended to remove any lunar dust and then were hoisted aboard the recovery helicopter. The “contaminated” raft was deliberately sunk.

The SH-3 then flew the astronauts to Hornet, touched down, and was lowered into the hangar bay, where the astronauts were then put into the mobile quarantine facility (MQF) for 21 days in the remote chance they’d picked up any pathogens on the moon. President Nixon welcomed the astronauts back through the window of the quarantine facility and then wasted no time getting off the ship. The Hornet then hoisted the Columbia command module onto the ship using the ship’s crane after which the Columbia was attached to the mobile quarantine facility with a flexible tunnel. Upon return to Pearl Harbor, the MQF (with the astronauts still inside) and Columbia were offloaded from Hornet, and flown separately to the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas.

The recovery of Apollo 11 was the most complex of all, as it was the first lunar mission and due to the protocols dictated by the “extra-terrestrial exposure law” intended to prevent any possible pathogens from being returned to Earth. Nevertheless, all 31 U.S. manned space missions before 1975 (and advent of the space shuttle) were recovered by U.S. Navy ships. Although the Soviet Union recovered their astronauts on land using a retrograde rocket system, the United States determined that landing at sea was safer, although that required considerably more coordination.

The first U.S. manned space launch was a sub-orbital flight by Mercury 3 (Freedom 7) on 5 May 1961, with Commander Alan Shepard, Jr. (naval aviator) on board, which splashed down 3.5 miles from the recovery ship, the aircraft carrier USS Lake Champlain (CVS-39). Between 1961 and 1975, 17 U.S. Navy ships would act as recovery vessels for Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and Skylab manned space missions. USS Wasp (CVS-18) has the record with five recoveries (Gemini 4, Gemini 7, Gemini 6A, Gemini 9A, and Gemini 12). USS New Orleans (LPH-11) made four recoveries (Apollo 14, Skylab 3, Skylab 4, and the Apollo-Soyuz joint U.S.–Soviet space mission, which, on 24 July 1975, was also the last U.S. ship recovery). USS Ticonderoga (CVS-14) made three recoveries (Apollo 16, Apollo 17, and Skylab 2) and USS Hornet recovered the second lunar landing mission, Apollo 12, on 24 November 1969. USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2) recovered the almost-disastrous Apollo 13 mission on 17 April 1970 (Apollo 13 was commanded by naval aviator Captain James Lovell, who had also been on Apollo 8, the first manned spacecraft to orbit the Moon, in December 1968).

The manned spacecraft recoveries were initially in the Atlantic, although the Apollo lunar missions (8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17), the three Skylab missions (2, 3, 4), and the Apollo-Soyuz mission all splashed down in the Pacific as intended. The first spacecraft to splash down in the Pacific was Mercury 8/Sigma 7 flown by Commander Walter Schirra, Jr. (a naval aviator), which hit the water only half a mile from the recovery ship USS Kearsarge (CVS-33). Schirra joked that he was on course to recover on Kearsarge’s “number three elevator.” The next (and last) Mercury mission (Mercury 9/Faith 7) flown by Gordon Cooper, also recovered in the Pacific after experiencing a number of technical problems that necessitated Cooper making a manual reentry. Cooper splashed down only four miles from Kearsarge, which was actually the most accurate landing of the Mercury program, since Schirra wasn’t supposed to splash down as close to Kearsarge as he did.

The biggest “miss” of any of the recoveries was Mercury 7/Aurora 7, flown by Lieutenant Commander Scott Carpenter (a naval aviator), which splashed down 250 miles off-course on 24 May 1962. After a search, Carpenter was located by land-based aircraft and then picked up by helicopter from USS Intrepid (CVS-11). (This search is actually one of my very earliest childhood memories, watching it on TV with Walter Cronkite being very concerned, which scared us kids). The USS John R. Pierce (DD-753) steamed 206 nautical miles off-station at flank speed to recover the capsule. The only failed recovery was Mercury 4/Liberty Bell 7, flown by Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom. Although Grissom splashed down only 5.8 miles from the recovery ship, USS Randolph (CVS-15), the hatch blew prematurely and the capsule took on water. One helicopter rescued Grissom, while a second tried to keep the capsule from sinking, but was unable to safely do so and cut it loose in 16,000 feet of water (it was recovered in 1999). Years of controversy ensued as Grissom was suspected of accidentally blowing the hatch himself, although this does not appear to be the case.

Lastly, on 27 January 1967, during a simulated countdown, a fire in the Apollo 1 command module killed Lieutenant Commander Roger B. Chafee, USN, along with Gus Grissom and Ed White.

Sources include; NHHC’s “Chronology of Space Missions Involving U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Crew Members, 1961–April 1981”; NHHC Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS); Neil Armstrong’s training log book at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida; First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong by James R. Hansen, Simon and Schuster, New York, 2005; “The Near Miss of Apollo 11” by Captain Forrest Zetterberg, USNR (Ret.), and Carol Zetterberg, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, July 2019. Although I generally use great caution with Wikipedia entries, those for U.S. space missions are quite thorough and well-documented.