H-053-2: The Surrender of Japan

The Japanese surrender ceremony in progress, as seen from USS Missouri's foredeck, with the Marine guard and Navy band in the center foreground and the ship's embarkation ladder at lower left. The backs of the Japanese delegation are visible on the O-1 level deck, to the left of 16-inch gun turret No. 2 (SC 210628).

The Japanese Decision to Surrender

At the time of the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, senior decision-making authority in Japan was vested in the six-member Supreme Council for the Direction of the War. Three of the members were active duty or retired Imperial Japanese Navy admirals. The ultimate decision maker in Imperial Japan was Emperor Hirohito, whom the Japanese believed to be divine. However, making mistakes is bad for a divinity’s reputation, so the emperor only directly intervened on rare and extremely important matters. Emperor Hirohito was routinely kept informed of the course of the war, and it became increasingly common for senior leaders of the army and navy to apologize to the emperor when something went badly. Nevertheless, the emperor rarely directly told any government, army, or navy leaders what to do.

Most (but not all, especially in the army) senior leaders of Japan understood that an outright victory against the United States was unlikely and that sooner or later the overwhelming industrial might of the United States would overpower Japan. Thus, the Japanese objective was to play for a negotiated end to the war on terms as favorable to Japan as possible. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto recognized this at the very start, and the whole point of the Pearl Harbor attack was to destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet to force the United States to negotiate. As the war continued and went badly, the Japanese objective was to inflict so much cost in blood on U.S. forces that the American people would tire of the war and force the U.S. government to negotiate. Although this was the objective, it was not until the very end that the Japanese considered initiating such negotiations; the idea was to force the United States to offer terms first. The problem for the Japanese was that the perfidy of the “sneak attack” on Pearl Harbor led to an unwavering U.S. war objective of “unconditional surrender.” From the very beginning, the United States had no interest in negotiations.

In the early years of the war, General Hideki Tojo held three of the six positions on the Supreme Council; prime minister, minister of war (army), and chief of the army general staff. Tojo was arguably the man most responsible for pushing Japan into the war, although he had plenty of support. He did not have complete dictatorial power, as the Navy strongly asserted its independence, but he effectively quashed any serious attempts to negotiate an end to the war while he had the power to do so. However, when the Marianas Islands fell to U.S. forces in July 1944, senior Japanese leadership understood that the war was effectively lost, and no amount of propaganda could hide the fact. Tojo received the blame and was forced out, having lost face. The next prime minister only lasted until the United States took the Philippines.

With the loss of the Marianas and the Philippines, some members of the new Japanese government under Prime Minister Admiral (retired) Kantaro Suzuki got serious about negotiations and approached the government of the Soviet Union under Josef Stalin to intercede. The Soviets and Japanese had signed a neutrality pact in April 1941, two years after a particularly nasty, but short, border war in Manchuria, during which both sides suffered thousands of casualties, but the Japanese were decisively defeated. The Japanese believed that the Russians would help because the neutrality treaty enabled the Russians to send many troops from the Far East at the critical moment to blunt Hitler’s offensive into Russia in 1941.

What the Japanese didn’t know was that Stalin had no intention of keeping the neutrality pact past its usefulness and had promised the Allies at the Tehran Conference in November 1943 that he would eventually join the war against Japan. At the Yalta conference in February 1945, Stalin promised he would enter the war against Japan 90 days after the defeat of Germany (and he kept his word almost to the day). What the Japanese also didn’t know was that U.S. intelligence was reading the Japanese diplomatic code (Purple) as fast as they were, and was fully aware of the Japanese negotiation attempts and that the Russians were deliberately stringing the Japanese along. The United States also knew that the Japanese leadership was seriously split between a few who were in favor of a negotiated peace and those who were in favor of a die-hard fight to the end.

As of 6 August 1945, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War was made up of the Prime Minister Admiral (retired) Kantaro Suzuki, Minister of Foreign Affairs Shigenori Togo, Minister of the Army General Korechika Anami, Minister of the Navy Admiral Mitsumasa Yonai, Chief of the Army General Staff General Yoshijiro Umezu, and Chief of the Navy General Staff Admiral Soemu Toyoda.

The prime minister, Admiral Suzuki, had been commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet in 1924 and had retired in 1929. As a captain, he had made a port call in the United States in 1918 in command of the armored cruiser Iwate (sunk by U.S. carrier aircraft in the strikes on Kure in July 1945).

The minister of the navy, Admiral Yonai, was technically an active duty navy flag officer (a requirement of the position). Yonai had become a full (four-star) admiral and navy minister in 1937 and had been appointed prime minister in 1940, but had been forced out by the army due to his opposition to going to war and his pro-American leanings. Of the six members of the council, he was the only one openly in favor of an early negotiated peace. Being “open” carried serious risk of assassination.

Admiral Soemu Toyoda replaced Admiral Koshiro Oikawa on 29 May 1945, following the first serious formal discussion about ending the war. Oikawa believed the war was clearly lost and resigned when the Supreme Council refused to consider peace proposals formally. Toyoda, along with Generals Anami and Umezu, held a vociferous hardline “fight to extinction” view (which was actually the Supreme Council’s formal position in a vote taken 6 June). Suzuki and Togo kept their real opinions close to their vests. The challenge for the Japanese was that any major decision regarding the course of the war required the unanimous consent of the Supreme Council. It was not until 22 June (after the fall of Okinawa) that the emperor, in a typically enigmatic way, expressed support for ending the war (without a fight to the death for everyone).

Between 16 July and 2 August, President Truman, Josef Stalin, and Winston Churchill met at Potsdam in defeated Germany. (Actually, in a surprising display of ingratitude, Prime Minister Churchill was voted out of office during the conference and replaced by new Prime Minster Clement Atlee.) The Potsdam Declaration was issued on 26 July and specified terms for the surrender of Japan. After somewhat incongruously laying out a number of conditions, the declaration concluded that Japan proclaim “unconditional surrender” or face the alternative, “prompt and utter destruction.” The declaration made no mention of the Japanese emperor.

The Supreme Council haggled over the Potsdam Declaration, but repeatedly failed to achieve unanimous consensus as the hardliners refused to budge, voting 4 to 2 to reject the declaration. The Supreme Council also did not have a sense of urgency because Japanese intelligence had assessed, correctly, that the United States would not invade Kyushu (also a correct assessment) until November 1945. U.S. leaders, on the other hand, were aware of the status of the debate due to the broken Japanese diplomatic codes.

The first atomic bomb blast on 6 August had little impact on the Supreme Council when they were informed almost immediately. Both the Japanese army and navy had their own independent atomic weapons development efforts and the leaders knew full well how difficult it was to make a bomb. Admiral Toyoda was skeptical that the devastation of Hiroshima was caused by an atomic bomb, but if it was, Toyoda stated, correctly, the United States couldn’t have very many. Most Japanese cities had already been laid waste with hundreds of thousands dead as a result of incendiary raids by B-29s and Hiroshima was just one more (the radiological effects were little understood by anyone at that point). U.S. planners associated with Project Alberta (the employment of the atomic bomb) had correctly anticipated exactly such a reaction by the Japanese, which is why it was believed necessary to hit the Japanese with a second bomb as soon as possible (see H-Gram 052) to bluff them into thinking that the United States had plenty more. Of note, a third bomb would not have been ready until 19 August and fourth not until late September, followed by a long gap in development.

Historians and others have had a long-running food fight over whether the Soviet entry into the war or the second atomic bomb was what really caused the Japanese to sue for peace. In Cox’s opinion, the answer is “yes.” It was a one-two punch of profound shock.

Word of the Soviet invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria and southern Sakhalin Island reached Tokyo at about 0400 on 9 August. It would be a couple days before the Japanese truly understood the full scope of the debacle as the massive Soviet multi-directional combined arms attack cut through the vaunted (but skeletonized) Japanese Kwantung Army like butter, stopping only when Soviet fuel supply couldn’t keep up with the tanks. What the Japanese leadership did immediately grasp was that the clock was just about to run out for negotiations. While the U.S. invasion was not expected until November, the Soviets could, in theory, be in Hokkaido in a week. The Japanese who supported peace overtures experienced a demoralizing realization that the Soviets had been lying to them all along.

The Soviet invasion of Manchuria is often characterized as the Russians jumping in at the last moment. This is not the case. The Soviet intervention was very carefully planned and executed, with the full support of the United States. It was the United States that, at the last moment (after news that the atomic bomb worked), decided that Russian intervention that had been actively sought wasn’t such a good idea after all. The sense that Russian entry into the war with Japan was not really necessary had been building in the last year of the war in senior U.S. military and especially Navy leadership. Nevertheless, although the Russians supplied their own tanks, artillery, and men, the vast majority of the munitions that enabled the Soviet attack were supplied by the United States in a major stream of neutral-flag shipping across the North Pacific to Soviet Ports at Petropavlovsk and Vladivostok. (The amount of munitions transferred to the Soviets by sea dwarfed the far more famous aerial supply of China “over the Hump”—the Himalayas.) The Japanese knew of this shipping, but took no action against it for fear of bringing the Russians into the war. The Soviet offensive would not have been possible without this U.S. support, at least not as soon as it occurred.

In addition, the U.S. Navy was the major participant in a secret program to provide the Soviets with lend-lease ships and aircraft through Alaska, specifically with the intent of using them against the Japanese. Between March 1945 and the end of the war, at an isolated location in the Aleutian Islands, the U.S. Navy trained 12,000 Soviet Navy personnel and transferred 149 ships and vessels (mostly frigates, mine warfare, and amphibious vessels) in an operation known as “Project Hula,” the largest transfer program of the war.

The news of the Soviet offensive sent the Supreme Council into urgent session, with Prime Minster Suzuki and Minster of Foreign Affairs Togo coming out in favor of opening a negotiating channel to the United States via Switzerland and Sweden, along with Navy Minister Yonai. Togo’s proposal to accept the Potsdam Declaration with the condition that the emperor’s position be preserved (something the declaration did not specifically address). The hardliners countered with a proposal that added additional conditions (which the Allies would certainly reject). As the discussion was going on, General Amani and General Umezu were secretly taking steps to implement martial law to prevent any such negotiations from happening at all. At 1030, Suzuki reported to the council that the emperor was in favor of ending the war quickly. Nevertheless, the council was still deadlocked 3–3 at 1100 when word of the Nagasaki bomb was received, and remained so even afterward.

With the Supreme Council still deadlocked, the full cabinet met at 1430 on 9 August, again arriving at a 3–3 vote. Arguments raged in a series of meetings late into the night. Finally, Suzuki requested an impromptu imperial conference with the Supreme Council and the emperor, which commenced at midnight and continued until 0200. Finally, Suzuki informed the emperor that consensus was impossible and requested that Hirohito break the stalemate. The emperor sided with Togo’s proposal to make an offer to accept the Potsdam Declaration with the condition that the emperor’s position be preserved. Suzuki then implored the Supreme Council to accept the emperor’s will.

On 10 August, the Japanese government sent a telegram via the Swiss, which was immediately intercepted by U.S. intelligence. As U.S. leaders evaluated the Japanese proposal, President Truman ordered a halt to the bombing of Japan and that the next use of an atomic bomb would require explicit presidential authorization (the second one didn’t). As a result, Chief of Naval Operations Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King sent a “Peace Warning” message to Nimitz. Nimitz had already ordered Halsey to conduct another round of carrier strikes on the Japanese home islands, which he then countermanded.

On 12 August, the United States responded to the Japanese offer, stating that “The ultimate form of government of Japan, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, to be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” The Japanese found the response to be ambiguous, which it was, provoking more heated discussion in the Supreme Council whether to hold out for an “explicit guarantee” of the emperor’s position. The same day, the emperor informed his family members that he had made a decision to surrender.

On 13 August, U.S. B-29s dropped leaflets all over Japan, making public the Japanese proposal and the U.S. counterproposal. A strong case can be made that it was actually the psychological impact of this huge leaflet drop that tipped the balance (making it one of the most effective psyops campaigns in history), although by this time the full magnitude of the collapse of Japanese defenses in Manchuria and Sakhalin Islands was also known to the Supreme Council, which finally agreed that the language in the U.S. counterproposal was good enough.

The U.S. counterproposal of 12 August directed the Japanese response to be sent in the clear. However, the Japanese sent their response message to their embassies in Switzerland and Sweden in code, which the United States initially interpreted as a “non-acceptance.” In addition,, there was a major spike in Japanese military message traffic, raising concern that an all-out banzai attack was in the works. As a result, President Truman reluctantly ordered a resumption of bombing. Over the course of 14 August, over 1,000 B-29s bombed Japan in the largest single day of strikes in the war, which also wiped out the last operational oil refinery in Japan. Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet geared up for a resumption of carrier strikes on the Tokyo area, set for daybreak on 15 August (see H-Gram 051).

On 14 August, Emperor Hirohito met with senior army and navy leaders. Admiral Toyoda, General Anami, General Umezu, and most military leaders wanted to fight on. An exception was the commander of the Second Army, who would be responsible for the defense of southern Japan and whose headquarters in Hiroshima had been obliterated. He argued that continued fighting was futile. Finally, the emperor announced that he had decided to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration with the “will of the people” caveat. The emperor having announced a decision, the Supreme Council and the full cabinet unanimously ratified it. The Foreign Ministry sent a coded message to the Japanese embassies around the world of their intent to accept the Allied terms, which was intercepted and reached Washington at 0249 on 14 August (late afternoon 14 August Tokyo time). However, the intercept of Japanese intent did not constitute the actual official Japanese response, so plans for Navy strikes on 15 August continued.

At 2300 on 14 August (Tokyo time) the emperor made a gramophone recording reading his statement to the Japanese people of his decision to surrender (without ever actually using that word), which was to be broadcast to the Japanese people over the radio at noon on 15 August. A couple of trusted members of the emperor’s personal staff then hid the copies of the recording.

Meanwhile, a coup attempt was underway, led by Major Kenji Hatanaka and other mid-grade army officers who were against surrendering. By midnight, the renegade army group surrounded the Imperial Palace and gained access under the false pretense of defending the palace against an outside revolt. Hatanaka shot and killed Lieutenant General Takeshi Mori, the commander of the Palace Guard, who had become suspicious. Other renegades fanned out across Tokyo and tried to assassinate Prime Minister Suzuki and other government officials. Despite threats of death, the palace officials who knew where the recordings were refused to acknowledge their whereabouts. The renegades then searched throughout the labyrinthine palace in an attempt to find and destroy the recordings. The search was severely hampered when Tokyo was blacked out in response to the very last B-29 bombing mission of the war, which targeted the oil refinery north of Tokyo. The rebels could not find the recordings and, by about 0800 in the morning, the coup fizzled as key army units failed to rally to the rebels’ side.

Just before dawn, aircraft from Halsey’s carriers had begun launching to attack targets in the Tokyo area. Two hours later, as the first wave of carrier aircraft were approaching their targets, the Pacific Fleet Intelligence Officer, Captain Edwin Layton, barged into Nimitz’ office with the intercept of Japan’s official acceptance of unconditional surrender. Nimitz ordered a flash message sent to cease all offensive air operations. The carrier planes were recalled before any bombs were dropped, but four U.S. Hellcats were shot down by Japanese fighters on the way back, and their pilots lost.

On board USS Nicholas (DD-449), two U.S. Navy officers examine a Japanese officer's sword, 27 August 1945. The Japanese were on board to provide piloting services for Third Fleet ships entering Sagami Wan and Tokyo Bay. Note other Japanese swords and sword belts on the table in the foreground (80-G-332611).

Fleet Admiral King’s reaction to the news was, “I wonder what I am going to do tomorrow.”

At noon, 15 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito’s radio address went out to the Japanese people. It was the first time the vast majority of Japanese people had ever heard his voice. Because of the poor quality of the recording and the archaic style of Japanese used in the Imperial Court, most of the people didn’t understand what he was saying. But, for the first time in its history, Japan had surrendered to a foreign power.

General Anami committed suicide before the address. General Umezu and Minister of Foreign Affairs Togo were tried and convicted as war criminals and died in prison. Admiral Toyoda would be the only member of the Japanese military tried for war crimes and acquitted. Admiral Yonai would be the only member of the Supreme Council to remain in his position after the war. Admiral Suzuki resigned as prime minister upon the announcement of the surrender.

President Truman allowed Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy to address the American public on the radio. (Leahy was the senior U.S. military officer with a position roughly analogous to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.) Leahy’s words are still relevant: “Today we have the biggest and most powerful navy in the world, more powerful than any other two navies in existence. But, we must not depend on this strength and this power alone. America’s true strength and secret weapon, that really won the war, came from our basic virtues as a freedom-loving nation.”

After the war, the United States would learn that the estimates of 5,000–7,000 Japanese kamikaze that would oppose the U.S. invasion were far too low. The real number was over 12,000, plus about 5,000 Shinyo suicide boats and several hundred midget submarines. In a future H-gram, I will discuss the U.S. plan for the invasion of Japan (Operation Downfall) and the Japanese counter (Operation Ketsugo).

The Japanese Surrender

Fleet Admiral Nimitz issued a directive upon the termination of hostilities against Japan: “It is incumbent on all officers to conduct themselves with dignity and decorum in the treatment of the Japanese and their public utterances in connection with the Japanese …the use of insulting epithets in connection with the Japanese as a race or as individuals does not now become the officers of the United States Navy.”

On 19 August, two Japanese Navy G4M Betty bombers took off from an airfield near Tokyo, carrying a delegation of 16 Japanese officers led by Lieutenant General Torashiro Kawabe, the Vice Chief of the Army General Staff. In accordance with directions from General MacArthur’s headquarters, the two planes were disarmed, painted completely white, with green crosses replacing the red “meatballs.” The U.S. forces gave the planes the call signs “Bataan 1” and “Bataan 2.” The aircraft initially flew northeast as there was serious concern they might be shot down by rogue Japanese fighters, which had fired on U.S. reconnaissance aircraft after the cease-fire. They picked up an escort of U.S. Army Air Forces P-38 fighters and B-25 bombers, and flew to Ie Shima airfield, on a small island just off Okinawa. One terrified young Japanese airman offered a bouquet of flowers to the Americans, which was rebuffed. At Ie Shima, the delegation transferred to a U.S. C-54 transport plane (also call letters B-A-T-A-A-N) and flew to Nichols Field, near Manila. There were no negotiations. The Japanese were given directions for what they needed to do to prepare for the formal surrender and subsequent occupation of Japan.

The Japanese delegation was given instructions that originated from Fleet Admiral Nimitz regarding the Japanese navy. All Japanese ships were to remain in port pending further directions. Any ships at sea were to immediately report their position by radio in the clear, remove breechblocks from all guns, and train main battery weapons fore and aft. All torpedo tubes were to be emptied. Searchlights were to be on and vertical at night. Submarines at sea were to surface and fly a black flag or pennant and proceed to designated Allied ports. All aircraft were to be grounded, harbor defense booms opened, navigation lights lit, obstacles removed, explosives secured, and minefields removed (the minefields would prove to be a major challenge, especially those laid by the United States).

The first U.S. aircraft to land in Japan were two Army Air Forces P-38 fighters on an armed reconnaissance mission that ran low on fuel and landed at a field on Kyushu on 25 August. An hour later, a B-17 landed with fuel for the fighters and then all took off.

The lead elements of the U.S. 11th Airborne Division were scheduled to land at Atsugi Airfield, near Tokyo on 26 August to conduct initial reconnaissance and set up communications. However, typhoon conditions caused the operation to be delayed by two days (as was General MacArthur’s subsequent arrival).

On 27 August, a fighter pilot of Carrier Air Group 88 on Yorktown (CV-10) brazenly landed at Atsugi, in defiance of orders, and directed the startled Japanese to hang a banner that read, “Welcome to Atsugi from Third Fleet,” which would greet the U.S. Army advance team when they arrived on 28 August.

Also on 27 August, the lead elements of Third Fleet entered Sagami Wan (the bay on the Kamakura/Zushi side of Miura Peninsula—Yokosuka is on the other side of the peninsula). Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet flagship, Missouri (BB-63), entered in company with destroyers Nicholas (DD-449, 16 Battle Stars) O’Bannon (DD-450, 17 Battle Stars) Taylor (DD-468, 15 Battle Stars), Stockham (DD-683, 8 Battle Stars), and Waldron (DD-699, 4 Battle Stars). O’Bannon had the most Battle Stars of any U.S. destroyer, with the distinction of having suffered no combat deaths in some of the most horrific battles of the war. Nicholas, O’Bannon, and Taylor were specifically selected by Halsey, “because of their valorous fight up the long road from the South Pacific to the very end.”

Following Missouri into Sagami Wan was a Royal Navy squadron led by battleship Duke Of York, flagship of Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, commander of the British Pacific Fleet.

The small Japanese destroyer-escort Hatsuzakura (“Early Blooming Cherry”), one of the very last ships commissioned in the Imperial Japanese Navy (May 1945), brought harbor pilots and translators to Missouri. Nicholas then distributed them to other ships. On the Yokosuka side, the Japanese towed the battleship Nagato (the only Japanese battleship still afloat) out to anchor in Tokyo Bay in an attempt to salvage some shred of dignity.

On the morning of 28 August, the minesweeper Revenge (AM-110) led a group of minesweepers to ensure the path into Tokyo Bay was clear. Then, the first of 258 Allied ships steamed into Tokyo Bay. The first to enter were destroyer-minesweepers Ellyson (DMS-19), Hambleton (DMS-20), and destroyer-minelayer Thomas E. Fraser (DM-24). Then came the new Gearing-class destroyer Southerland (DD-743) and then Twining (DD-540). Next was the anti-aircraft light cruiser San Diego (CL-53), flagship of Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger, commander of the occupation task force. (With 18 Battle Stars, San Diego was second only to carrier Enterprise (CV-6), which had earned 20 Battle Stars.) Next came destroyer-transport Gosselin (APD-126), destroyer Wedderburn (DD-684), and then seaplane tenders Cumberland Sound (AV-17) and Suisun (AVP-53).

Battleships South Dakota (13 BB-57) and Missouri (BB-63) entered Tokyo Bay, followed by six more U.S. and two British battleships. With 15 Battle Stars, South Dakota was tied with North Carolina (BB-55) for the most Battle Stars of any battleship, although South Dakota had suffered the most casualties of any battleship after Pearl Harbor. North Carolina remained on duty at sea off Japan with all the U.S. carriers, except for light carriers Cowpens (CVL-25) and Bataan (CVL-29), which entered Tokyo Bay.

Missouri was selected for the site of the surrender ceremony by President Truman upon the recommendation of Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal. Not only was Missouri President Truman’s home state, but the ship had been christened by his daughter Margaret. Forrestal also engineered a graceful compromise between the Army and the Navy after Truman named General MacArthur the Supreme Commander Allied Powers (SCAP), somewhat to the Navy’s chagrin, which held that the service had done far more to bring about the defeat of Japan than McArthur and the Army. Forrestal suggested that the formal surrender be held aboard a ship, and that McArthur would sign for the Allied Powers and Nimitz would sign for the United States. The proposal was accepted.

Missouri anchored 4.5 nautical miles northeast of the spot where Commodore Mathew C. Perry’s four-ship squadron had anchored in July 1853, an event that resulted in the “opening” of Japan to U.S. trade, literally at the point of a gun (actually, 73 of them). Halsey requested that the U.S. Naval Academy Museum (now part of NHHC) dispatch the flag that had flown on Perry’s flagship USS Susquehanna during the Japan expedition. Lieutenant John K. Bremyer, of the Navy’s top secret courier service, carried the 31-star flag 9,000 miles, leaving Washington, DC, on 23 August with only stops for fuel at Columbus, Ohio; Olathe, Kansas; Winslow, Arizona; San Francisco; Pearl Harbor; Johnston Island; Kwajalein; Guam; and Iwo Jima. The last leg was via an Army-Navy rescue seaplane that arrived in Tokyo Bay on 29 August, and the whaleboat from Missouri smashed the plane’s tail in the choppy seas. Halsey intended to fly the flag, but it was too fragile and had been backed by linen on the front side (so the stars are on the right). The flag was framed and mounted over the entrance to Captain Stuart S. “Sunshine” Murray’s in-port cabin on the O-1 level, where it is visible in photos of General McArthur reading his opening statement. The flag is now back at the Naval Academy Museum.

On 29 August, Nimitz and his staff arrived in Tokyo Bay aboard two PB2Y Coronado seaplanes and embarked on battleship South Dakota. The same day, anti-aircraft light cruiser San Juan (CL-54) entered Tokyo Bay with destroyer Lansdowne (DD-486) and hospital ship Benevolence (AH-13), and linked up with destroyer-transport Gosselin to commence Operation Swift Mercy, the location, care, and repatriation of Allied prisoners of war. The first camp liberated was the Omori Camp, the largest in the Tokyo area. The senior allied POW in the camp was Commander Arthur L. Maher, who was also the senior survivor of the heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), sunk in the Sunda Strait on 1 March 1942. Camp conditions were so appalling that Operation Swift Mercy was accelerated by 24 hours (ahead of General MacArthur’s arrival) and, by the next day, 1,500 POWs had been rescued from Omori, with many more to follow from elsewhere in Japan.

Also on 30 August, the destroyer-transport Horace A. Bass (APD-124) pulled alongside battleship Nagato and put a prize crew of 91 sailors from battleship Iowa (BB-61) aboard, led by her executive officer, Captain Thomas J. Flynn. The group included 49 explosive ordnance disposal personnel of UDT-18. When Flynn ordered the captain of Nagato to lower the rising sun flag, the Japanese captain tried to delegate it to a lower-ranking officer, but Flynn insisted the Japanese captain haul it down himself. Flynn then assumed command of the Japanese battleship. At 1030, San Diego docked at Yokosuka, following the landing of the 4th Marine Regiment. Nimitz and Halsey went ashore and toured the Yokosuka Naval Base.

That same day, General MacArthur landed at an airfield near Yokosuka, two days later than originally planned due to a typhoon, and then proceeded to his new headquarters in Yokohama in an old U.S.-made car that broke down multiple times. Nimitz and Halsey paid a call on MacArthur at his headquarters on 1 September, proceeding to Yokohama by the more reliable destroyer Buchanan (DD-486).

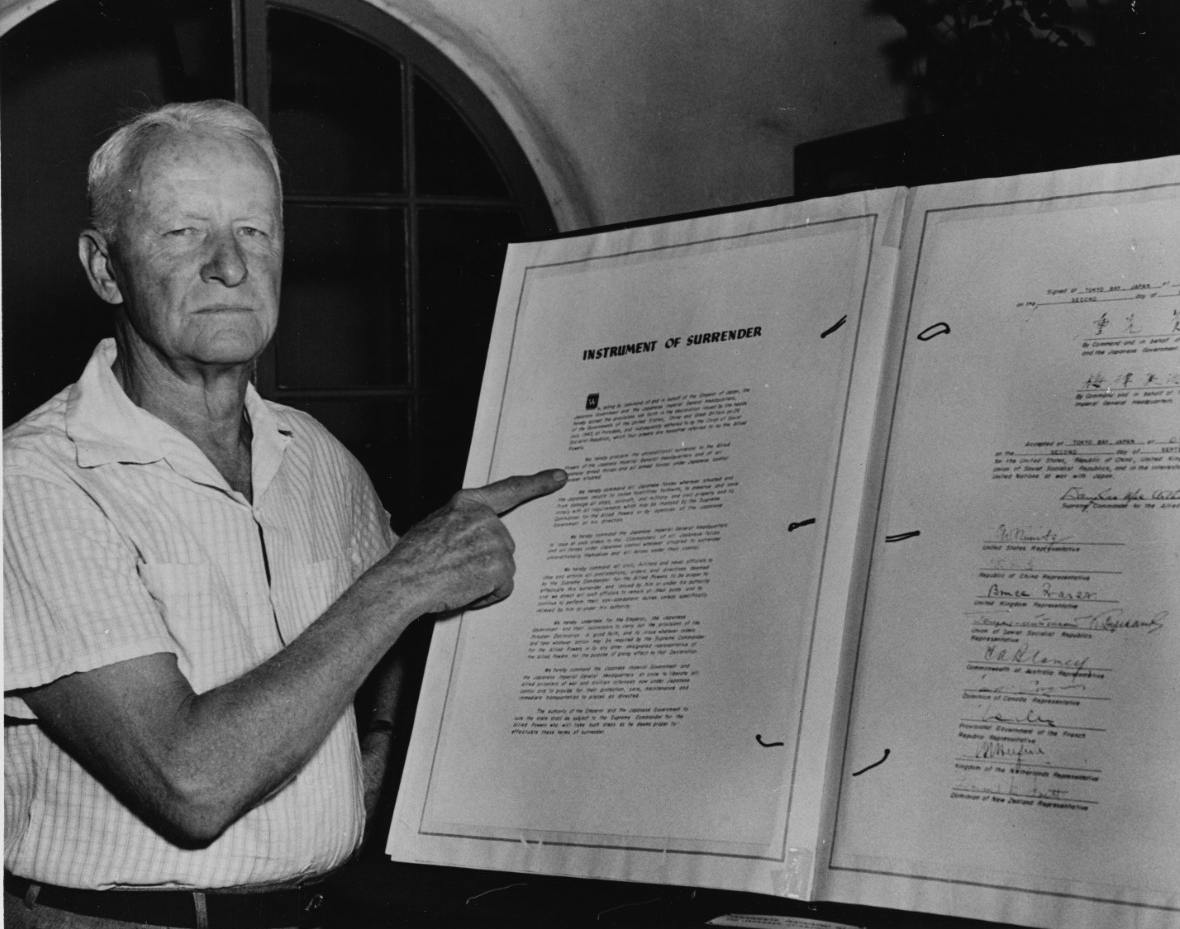

Japanese Foreign Ministry representatives Katsuo Okazaki and Toshikazu Kase, and Lieutenant General Richard K. Sutherland, U.S. Army, correcting an error on the Japanese copy of the Instrument of Surrender at the conclusion of the surrender ceremonies, 2 September 1945. Photographed looking forward from USS Missouri's superstructure. Note the relaxed stance of most of those around the surrender table. The larger ship in the right distance is USS Ancon (AGC-4) (USA C-4626).

At morning colors at 0800 Sunday on 2 September, Missouri hoisted the flag that the press claimed was flying over the U.S. Capitol on 7 December 1941, and which had subsequently flown over Casablanca, Rome, and Berlin when those cities fell to the Allies. According to Missouri’s skipper, Captain Murray, it was “just a plain GI-issue flag.” The national flags of all the Allied signatory nations were flown from the halyards.

At 0803, Allied representative arrived onboard Missouri from South Dakota via Buchanan. Nimitz arrived on a motor launch shortly afterward and broke his flag on Missouri. Halsey had already shifted his flag to Iowa. MacArthur arrived just after Nimitz. Both Nimitz’s blue five-star flag and MacArthur’s red five-star flag were flown at the exact same height, although Nimitz initiated a salute when MacArthur came on board and MacArthur returned the salute. The uniform of the day had been a matter of significant discussion, but MacArthur and Nimitz actually had little difficulty reaching agreement with words to the effect, “We fought the war without ties, we’ll have the ceremony without ties.” So for the Navy, the uniform for officers was long-sleeve open-neck khakis, no ties, no ribbons—and for enlisted, white jumpers.

The table for the surrender proceedings was set up on the O-1 level, starboard side, just aft of the No. 2 16-inch gun turret. Two copies of the surrender document were on the table, one for Allies to keep and one for the Japanese to take. The senior signing officials for the Allied nations were in the front rank behind the table and other Allied officers behind them. Senior U.S. Navy and Army officers were in ranks inboard of the table. Staff officers and crew of Missouri crammed into every square foot of the ship that had a line of sight to the table. Commodore Perry’s flag was prominently displayed above the arrayed officers.

In the line of U.S. officers was Vice Admiral John “Slew” McCain, who had just been relieved of command of Task Force 38, partly as a result of the findings of the board of inquiry following the damage suffered in Typhoon Viper. McCain just wanted to leave, but Halsey strong-armed him into staying for the ceremony, for which McCain subsequently expressed great gratitude. McCain returned to the United States four days later and died of a heart attack the next day.

Missing from the line-up was Admiral Raymond Spruance. Spruance was invited by MacArthur but declined. Nimitz and Spruance had agreed that Spruance should stay at sea, just in case of some Japanese perfidy. Spruance was aboard his flagship, battleship New Jersey (BB-62), off Okinawa during the ceremony.

The destroyer Lansdowne picked up the 11-man Japanese delegation from Yokohama, arrived alongside Missouri, and transferred the delegation to a launch that arrived at Missouri at 0856. The delegation was led by Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, signing for the Japanese government, and Chief of the Army General Staff Yoshijiro Umezu, signing for the Japanese military. When Umezu was informed it would be his duty to sign, it took the personal intervention of Emperor Hirohito to keep him from committing suicide. The other nine members of the delegation were three each from the Foreign Ministry, army, and navy. The delegation was piped aboard Missouri, but no salutes were rendered. There was dead silence aboard the ship throughout the entire proceeding. Shigemitsu had difficulty climbing the ladder from the launch to the main deck and then to the O-1 level because of his artificial leg (he had lost his right leg in 1932 in an assassination attempt by a Korean independence activist). Missouri sailors with broomsticks in their pants had rehearsed this to get the timing right so that the ceremony could start at precisely 0900.

General MacArthur convened the proceedings and, following the national anthem, gave a short, powerful speech that included the words, “It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past—a world founded on faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance, and justice.”

MacArthur then directed the Japanese to sign. Shigemitsu got confused about where to sign, so MacArthur directed his Chief of Staff, General Richard Sutherland, to show Shigemitsu the appropriate line. After the Japanese signed, MacArthur signed first for the Allied Powers, using six pens. Nimitz signed next for the United States using two pens. He signed the Allied copy with a pen given to him three months earlier by Y. C. Woo, a Chinese refugee neighbor of Nimitz in Berkeley where the two families had become very close. (Nimitz returned the pen to Woo after the ceremony, who re-gifted it to Chiang Kai-shek, and it ultimately wound up in a museum in the People’s Republic of China, where it is today.) Nimitz then signed the Japanese copy using the same 50-cent green Parker Duofold pen he had carried throughout the war, which is now in the Naval Academy Museum. Nimitz confessed in a letter to his wife that he was thankful that he managed to sign in the right place.

Eight other representatives of the Allied powers then signed the documents in the following order (which also matched the order in which they were arrayed behind MacArthur): China: General Hsu Yung-chang for China; Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser for Britain; Lieutenant General Kuzma Derevyanko for the Soviet Union; General Sir Thomas Blamey for Australia; Colonel Moore-Gosgrove for Canada (he did manage to sign in the wrong place, which caused a kerfuffle with the Japanese foreign ministry representatives until the signature was lined out and corrected); General Jacques Leclerc for France; Lieutenant Admiral Conrad Helfrich for The Netherlands; and Air Vice Marshal Sir Leonard Isitt for New Zealand.

Following a benediction, the ceremony ended at 0925. There were no salutes or handshakes. As the Japanese were departing, 450 carrier planes and 600 B-29 bombers commenced the greatest airpower demonstration flyover in history.

After the ceremony, the Soviet representative and Russian photographers staged a photo shoot at the surrender table that made it look like Lieutenant General Derevyanko was dictating terms to the Japanese. The Soviet delegation had generally made a nuisance of themselves before and during the ceremony, particularly when those on top of turret No. 2 stood up deliberately and blocked the view of many of the photographers.

Fleet Admiral Nimitz flew back to his forward headquarters on Guam the next day, taking along a Marine who had just been liberated from a Japanese prison camp. Nimitz described the Marine as “about the happiest young man I ever saw.” In all, 62,614 U.S. Navy personnel did not come home from the war; 36,950 due to enemy action.

Perhaps the last word should go to a Japanese naval officer who survived the war, Vice Admiral Masao Kanazawa: “Japan made many strategical mistakes, but the biggest mistake of all was starting the war.”

____________

Sources include: The Naval Siege of Japan: War Plan Orange Triumphant, by Brian Lane Herder, Osprey Publishing, 2020; Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945–1947, by D.H. Gianreco, Naval Institute Press, 2009; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, 1945, by Samuel Eliot Morison, Little, Brown and Co.,1960; The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy and King—The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea, by Walter R. Borneman, Back Bay Books, 2012; The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific, 1944–1945, by James D. Hornfischer, Bantam Books, 2016; Nimitz at Ease, by Captain Michael A. Lilly, USN (Ret.), Stairway Press, 2019; combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships; and Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships.