H-Gram 045: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die (2)—USS Laffey (DD-724), 16 April 1945

16 April 2020

Contents

75th Anniversary of World War II

This H-gram covers the Naval Battle of Okinawa from the second massed kamikaze attack (Kikusui No. 2) through Kikusui No. 3 and No. 4 to 2 May 1945, with special emphasis on the ordeal of USS Laffey (DD-724) on 16 April 1945. It is a follow-on to H-Gram 044. For more on the background on the invasion of Okinawa, please see H-Gram 044’s attachment H-044-1.

USS Laffey (DD-724)

“No! I’ll never abandon ship as long as a single gun will fire!” stated Commander Frederick J. Becton, commanding officer of destroyer Laffey as his severely damaged ship burned on 16 April 1945.

Naval Historian Samuel Eliot Morison remarked, “Probably no ship has ever survived an attack of the intensity that [Laffey] experienced.” Morison was probably right.

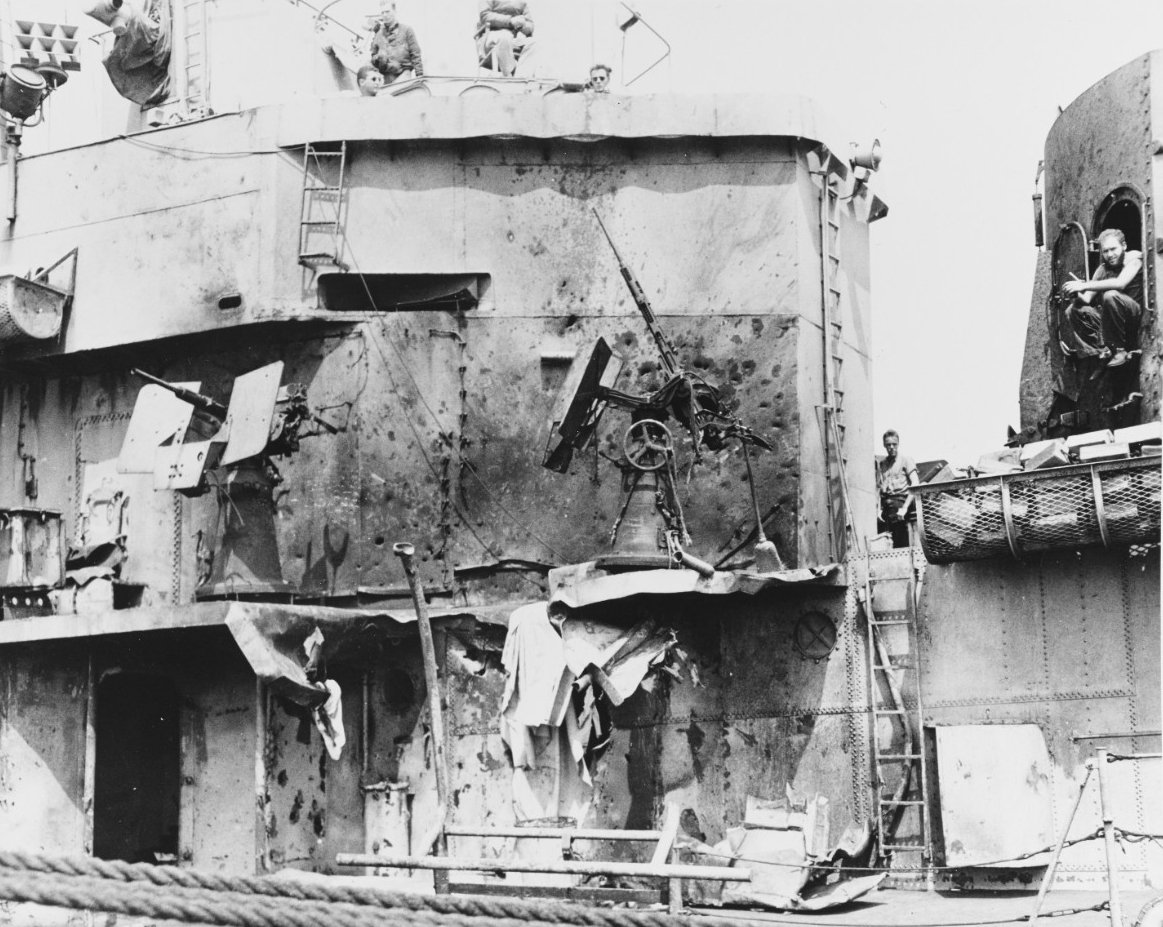

During the 80-minute attack by 22 Japanese kamikaze aircraft and dive-bombers at Radar Picket Station No. 1 northwest of Okinawa, Laffey shot down at least eight aircraft (six in the first 12 minutes) and damaged the six kamikaze that hit her. By this time, she had been damaged by four bombs (plus those carried on the kamikaze). With both her surface search and air search radars out of action, her aft 5-inch turret destroyed, one quad 40-mm destroyed and the other on fire, down by the stern due to a bomb hit, her rudder jammed 26 degrees over, with virtually everything after the aft stack engulfed in aviation gasoline fires from kamikaze hits, it seemed Laffey was doomed. Wounded men in the wardroom casualty aid station were killed by bomb shrapnel. But no one gave up. Gunners kept shooting despite flames all around, and damage control parties kept fighting the fires despite more bombs, strafing, and kamikaze. A number of the 20-mm gunners “died in the straps,” firing their guns at the kamikaze until the instant of impact. Skillful ship handling by Becton, one of the most battle-experienced officers of the time, in maximizing firepower against incoming aircraft and maneuvering to take the unavoidable hits from the stern rather than even more damaging ones from forward was a key factor in Laffey’s survival. Another critical factor was that the destroyer’s firerooms and engine rooms remained watertight.

The arrival of U.S. Marine Corps F4U Corsairs of VMF-441 “Blackjacks” finally changed the odds. The Marines heroically flew into Laffey’s anti-aircraft fire to down numerous Japanese aircraft. One Corsair crashed into the destroyer’s air search radar while chasing and downing a Japanese fighter (the Corsair pilot lived, the Japanese pilot didn’t). Despite horrific damage and high casualties (32 dead and 71—or 72—wounded), Laffey’s crew not only saved their ship, but the ship still had fight in her when the Japanese attacks ended. Commander Becton would be awarded a Navy Cross, and Ensign Robert Thomsen a posthumous Navy Cross. Other crewmen would be awarded six Silver Stars, 18 Bronze Stars and one Navy Letter of Commendation. Laffey would be awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. The skipper of LCS(L)-51 (large support landing craft), Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering, whose small and damaged vessel stood loyally by Laffey and downed six aircraft of her own, was also awarded a Navy Cross.

In many respects, Laffey was lucky. Over the next two months, other U.S. Navy ships would come under attacks almost intense and many would be hit, many with even higher casualties. In some cases, crews would save ships that should have sunk, in others the ship was lost despite their crews’ best efforts, often due to sheer random chance of where the kamikaze hit. One thing that is certain, however, was that the extreme valor shown by the crew of Laffey was hardly unique.

For more detail on the ordeal of Laffey, please see attachment H-045-1.

The Naval Battle of Okinawa, Part 2

Not only did U.S. ships off Okinawa face conventional and suicide aircraft attack, but a significant threat also came from Japanese submarines, some of them modified to piggy-back four to six Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes. Between the time U.S. forces arrived off Okinawa in late March 1945 to the beginning of May, the Japanese deployed two groups of Kaiten-equipped submarines, the Tartara Group (I-44, I-47, I-56, and I-58) on 28 March and the Tembu Group (I-47 and I-36) on 20 and 22 April. None of these Kaiten submarines successfully attacked targets, although I-44 and I-56 would be sunk trying.

Conventional Japanese submarines fared even worse than the Kaiten subs, with RO-41 (rammed by destroyer Haggard [DD-555]), I-8, RO-49, RO-56, and RO-109 all being sunk, accounting for almost every Japanese submarine deployed to the Okinawa area. The notorious I-8 (the submarine’s crew committed numerous war crimes against Allied shipwreck survivors) put up a spirited surface gun battle with destroyer Morrison (DD-560) before going down, and the rest used every trick in the book to escape, but were no match for superior U.S. ASW technology.

Japanese kamikaze went after the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF-58) on 11 April, damaging Enterprise (CV-6) and Essex (CV-9); the destroyer Kidd (DD-661) took a severe kamikaze hit, but survived.

The second massed Japanese kamikaze attack (Kikusui No.2) involved 185 kamikaze (125 navy and 60 army aircraft) on 12 April. The destroyer Mannert L. Abele (DD-733) was the first ship to be sunk by an Ohka rocket-assisted manned suicide bomb launched from a bomber, in a massive blast with heavy loss of life (84 killed and 30 wounded). LCS(L)-33 was also sunk. Destroyer Zellars (DD-777), destroyer-minesweeper Lindsey (DM-32), and LSM-189 were put out of action for the rest of the war. Battleship Tennessee (BB-43), destroyers Purdy (DD-734) and Cassin Young (DD-793), destroyer escorts Rall (DE-304) and Whitehurst (DE-634), and LCS(L)-57 were out of action for over a month. About 270 U.S. crewmen were killed and about 430 wounded.

The kamikaze threat was near continuous and, on 14 April, destroyer Sigsbee (DD-502) was badly damaged and nearly sunk.

Kikusui No. 3 came in on 16 April and included 165 kamikaze (120 navy and 45 army aircraft) and resulted in the loss of destroyer Pringle (DD-477) with heavy casualties (65 dead and 110 wounded), and putting the destroyers Laffey (DD-724) and Bryant (DD-665), destroyer-minesweepers Hobson (DM-26) and Harding (DM-28), and destroyer escort Bowers (DE-637) out of action for the duration of the war. Carrier Intrepid (CV-11) was also put out of action for over 30 days, leaving only five of the original 11 fleet carriers undamaged and on line (although all but Franklin [CV-13] would return). About 225 U.S. crewmen were killed and about 390 wounded.

Japanese kamikaze attacks on 22 April sank minesweeper Swallow (AM-65) and LCS(L)-15 and damaged destroyer Isherwood (DD-520).

Kikusui No. 4 came in on 27 and 28 April and included 115 kamikaze (65 navy and 50 army aircraft), and sank the ammunition ship Canada Victory. The destroyer Hutchins (DD-476) was put out action by a Japanese one-man suicide boat and destroyer-transport Rathburne (APD-25) was hit by a kamikaze. Both were saved by their crews, but were too damaged to repair. The evacuation transport Pinkney (APH-2) and hospital ship Comfort (AH-6) were seriously damaged by kamikaze hits. U.S. casualties during Kikusui No. 4 were 77 dead and 87 wounded. Among the dead were 27 Army personnel, including six nurses and ten patients, aboard Comfort. There is some evidence to suggest that the Japanese hit on Comfort was retaliation for the sinking of the Japanese Red Cross ship Awa Maru (with the loss of all but one of over 2,000 aboard) by submarine Queenfish (SS-393), which resulted in the court-martial of the submarine’s commanding officer.

On 29 April, destroyers Haggard (DD-555) and Hazelwood (DD-531) were badly damaged by kamikaze hits, and the next day the flagship of the Minesweeping Flotilla, Terror (CM-5), was put out of action.

However, the worst was not yet over for the U.S. ships off Okinawa, which will be continued in H-Gram 046. For more on the Naval Battle of Okinawa, Part 2, please see attachment H-045-2.

50th Anniversary of the Apollo 13 Mission

The original crew of the Apollo 13 lunar landing mission: (from left) Captain James A. Lovell, Jr., USN, mission commander; Lieutenant Commander Thomas A. Mattingly, Jr., USN, command module pilot (replaced by Jack L. Swigert, Jr., due to an inadvertent German measles exposure shortly before the launch); and Fred W. Hais, Jr., lunar module pilot (USN 1143249).

“Houston, we’ve had a problem,” calmly reported James A. Lovell, mission commander of Apollo 13, after a fire and an explosion in an oxygen tank had crippled the command and service modules. The spacecraft was 180,000 miles from Earth heading to the moon for what was supposed to be the third lunar landing. Using the lunar module’s independent supply of power, oxygen, and propulsion as a “lifeboat,” the three-man crew of Lovell, Jack L. Swigert, Jr., and Fred W. Haise, Jr., were able to survive as Mission Control in Houston worked feverishly to devise solutions to what became the only mission: to bring the astronauts back to Earth safely, hampered by many unknown variables regarding the severity of the damage. Unable to “turn around,” the only way home for the astronauts was to continue to the moon and use the propulsion of the lunar module and the moon’s gravity to act as a slingshot back to Earth, a trajectory that took the three astronauts father away from Earth than any man has been before or since. After several harrowing touch-and-go days, Apollo 13 splashed down safely in the South Pacific as over 40 million Americans were glued to their TV sets. The capsule was recovered by USS Iwo Jima (LPH-2).

Apollo 13 was the fourth space mission for naval aviator Jim Lovell. He had been aboard the longest-duration Gemini mission (Gemini 7) and the final Gemini mission (Gemini 12,). He had also been the command module pilot for Apollo 8, the first manned space craft to ever leave Earth’s orbit and the first to orbit the moon, transmitting an extraordinary Christmas Eve TV broadcast from lunar orbit. Only one other astronaut, naval aviator John W. Young, flew four missions during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs—and walked on the moon on his last mission. Only one astronaut, naval aviator Walter Schirra, Jr., flew missions in each of the three programs. Pilots who were or had been naval aviators (such as Neil Armstrong, the first to walk on the moon) played a prominent role in the “Race to the Moon” and, of course, every one of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions was safely recovered by U.S. Navy warships.

For more on James Lovell’s extraordinary Navy career, his four space missions, and the contributions of naval aviators to the early U.S. space program, please see attachment H-045-3.

H-gram "back issues" may be found here. As always, feel free to share widely—there are some truly inspirational stories.