H-045-2: The Naval Battle of Okinawa, Part 2

USS Missouri (BB-63) about to be hit by a Japanese A6M Zero kamikaze while operating off Okinawa on 11 April 1945. The plane hit the ship's side below the main deck, causing minor damage and no casualties on board the battleship. A 40-mm quad gun mount's crew is in action in the lower foreground (NH 62696).

Roll Call of Valor and Sacrifice

The Battle of Okinawa was so massive that it is impossible to capture the scope of the U.S. Navy’s valor and sacrifice in a relatively short piece. Victory has a price, and in the case of Okinawa an incredibly high one: just over 4,900 U.S. Navy personnel were lost. This H-gram focuses only on those actions that resulted in significant U.S. damage and casualties, from the second mass kamikaze attack (Kikusui No. 2) on 11–12 April 1945 through the end of April just before Kikusui No. 5. I’ve also included significant anti-submarine actions, as U.S. ships faced kamikaze threats from above and Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes from below.

Each U.S. ship listed below was sunk or put out of action for over 30 days, but in every case there are superb examples of the Navy core values of honor, courage, and commitment, and of core attributes of initiative, accountability, integrity, and—especially—toughness. I do not cover the innumerable near misses and close calls or minor damage, or frequent shoot downs of Japanese aircraft. By this time, so many damaged U.S. ships had sought refuge at Kerama Retto that it acquired the black-humor nickname of “Busted Ship Bay.” The U.S. also realized that one of the best defenses during the Japanese preferred attack hours of dawn and dusk was to generated massive smoke screens over any areas with a concentration of ships. As a result, more than a few kamikaze never found a target and crashed into the ocean without hitting anything. But, plenty of kamikaze still carried out their missions.

For the most part, casualty figures are from Appendix Two, Volume XIV (Victory in the Pacific) of Samuel Eliot Morison’s History of United States Naval Operations in World War II series. In many cases more detailed analysis in years since has led to changes in the casualty figures—frequently with deaths being somewhat higher as those who died of wounds much later are factored in, but these are scattered in various accounts. If I came across other more recent figures, I use the higher number. For symbols denoting ship damage/repair status, I’ve used the following:

* = sunk

# = damaged beyond repair

## = repairs completed after the war ended

Early Antisubmarine Operations: March to Mid-April 1945

28 March

The Japanese commenced the fifth Kaiten operation, deploying the Tartara Group (submarines I-44, I-47, I-56, and I-58) to attack U.S. ships in the vicinity of Okinawa. Within a day, I-47 was attacked by U.S. Navy TBM Avenger torpedo bombers and forced to dive. As soon as she surfaced, she was damaged by shrapnel from a bomb, but survived and limped back to port. The other three submarines continued with their mission, although I-58 was hounded so frequently by U.S. aircraft that she never found a target and returned to port (she would sink the USS Indianapolis [CA-35] at the end of July). Some Japanese submarines had been modified to carry manned suicide torpedoes, called Kaiten. For more on the background and capabilities of the Kaiten please see H-Gram 039, attachment H-039-4)

31 March

Japanese submarine I-8 was one of four sent out in response to the Task Force 58 raids on Japan on 18–19 March (which resulted in serious damage to aircraft carrier Wasp [CV-18] and grave damage to Franklin [CV-13] from Japanese air attack). I-8 had been the only Japanese submarine to complete a round-trip to Germany to exchange technology and pick up critical cargo, and had also been responsible for several atrocities against merchant ship crewmen in the Indian Ocean (see H-Gram 033, attachment H-033-1, on the Yanagi Misssons). I-8 had been converted to carry two Kaiten torpedoes by having her floatplane hangar and catapult removed; however, she never actually carried any Kaiten.

On the night before the main landings on Okinawa, destroyer Stockton (DD-646), Commander W. R. Glennon in command, was patrolling off Kerama Retto, assisted by the newly arrived PBM Mariners of VPB-21 that were tended by Chandeleur (AV-10) in Kerama Retto. Stockton detected a surface contact that quickly dove. The destroyer gained sonar contact and made seven depth-charge attacks over the next four hours, expending her entire load out of depth charges. Destroyer Morrison (DD-560) arrived just as the submarine surfaced and then quickly submerged. Morrison laid a depth-charge pattern over the submarine and presumably damaged it. I-8’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Shinohara, then decided to fight it out on the surface. I-8 engaged Morrison with her deck gun in a 30-minute gun battle before direct hits from Morrison’s 5-inch guns hit the submarine, which then capsized and went down by the stern. Morrison put a boat in the water at daybreak and managed to rescue (and capture) one of I-8’s gun crew; all other crewmen were lost.

5 April

Destroyer Hudson (DD-475), Lieutenant Commander R. R. Pratt in command, was on radar picket station when she received a signal from LCS(L)-115 of a submarine sighting. At 0345, Hudson detected a surfaced contact on radar and fired a star shell that caused the submarine to dive. Hudson reacquired the submarine on sonar and, over the next six hours, conducted six depth-charge attacks. The submarine is believed to be RO-49, lost with all 79 hands. This was the second submarine that Hudson received credit for sinking; the first was engaged off Bougainville on 31 January 1944, although the exact identity of that submarine is not clear.

9 April

Destroyers Monssen (DD-798), Lieutenant Commander E. G. Sanderson in command, and Mertz (DD-691), Commander W. S. Maddox in command, were screening TF 58 45 nautical miles west of Okinawa, when Monssen’s radar detected a surfacing submarine at a range of 900 yards. Monssen dropped three patterns of 13 depth charges, and then Mertz dropped three more, followed by another two patterns from Monssen. The submarine was believed to be RO-56, lost with all 79 hands.

Kamikaze Attacks and Anti-Submarine Operations, 11 April–2 May 1945

11 April

Japanese kamikaze attacks increased on 11 April, mostly directed against the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58) in advance of the major kamikaze attack, Kikusui No. 2, planned for 12–13 April against ships supporting the continuing Okinawa landings. There was advance intelligence warning that the attack was coming, including from a Japanese prisoner of war picked up on 6 April. In anticipation of the attacks, TF 58 cancelled support missions over Okinawa and increased the numbers of fighters on combat air patrol. Fighters shot down many of the Japanese planes, but some still got through.

At 1443, a Zeke fighter crashed into the battleship Missouri (BB-63) on the starboard quarter (a famous photo shows the plane an instant before impact). The plane made a small dent in the Missouri’s side (which may still be seen on the ship today at Pearl Harbor) and parts of the plane and the pilot’s body ended up on the main deck. A gasoline fire was quickly extinguished. No one on Missouri was killed or seriously injured. Crewmen were going to hose the remains of the pilot over the side, when Missouri’s skipper, Captain William Callaghan (brother of Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor at Guadalcanal) ordered that the pilot be given a military funeral with honors. This was done the next day, a somewhat controversial act at the time given the general viciousness of the fighting by that point in the war.

Shortly after the hit on Missouri, a D4Y Judy dive-bomber clipped the deck edge of carrier Enterprise (CV-6), carrying away some 40-mm gun-mount shields. At 1510, another Judy crashed close aboard the starboard bow, throwing debris up on to the flight deck and causing a Hellcat fighter on the starboard catapult to ignite. The burning and pilotless plane was catapulted into the water. The damage was substantial enough that Enterprise had to come off line and go to Ulithi for repairs before returning to Okinawa in May.

Kidd (DD-661). On the afternoon of 11 April 1945, several destroyers performing radar picket duty for TF 58 came under air attack. At 1357, lookouts on destroyer Kidd saw a Japanese plane dive out of the sun heading for Bullard (DD-660), which reacted and shot the plane down at the last moment after sustaining minor damage. Kidd and the other destroyers, working with combat air patrol, drove off several other attacks. At 1409, Kidd observed two aircraft engaging in an apparent dogfight. These were thought to be two Japanese aircraft engaging in a deceptive tactic to make the U.S. ships think one of them was friendly. One of the planes then dove to wave-top level and took aim at destroyer Black (DD-666), which was about 1,500 yards on Kidd’s starboard beam. Despite being hit by anti-aircraft fire, the smoking plane popped up and passed directly over Black, heading for Kidd. With little time to react, Kidd’s 40-mm and 20-mm gunners scored more hits, but the plane still bore in and crashed into the forward fireroom, killing everyone in the space. The bomb on the plane passed through the ship and exploded just on the other side, seriously wounding the commanding officer, Commander Harry G. Moore. Kidd suffered 38 killed and 55 wounded in the attack.

The executive officer, Lieutenant B. H. Britton, took command of the ship and, despite the severe damage, her crew brought the fires and flooding under control while the gunners continued to engage other targets. The destroyer Hale (DD-642) came alongside to transfer her doctor via high-line as Kidd’s doctor had also been severely wounded. While doing this, a bomb impacted about 20 yards from Kidd, jolting both ships. Despite the damage, Kidd was able to reach Ulithi on her own power and then headed to the U.S. West Coast for more extensive repairs. Commander Moore was awarded a Silver Star (I can’t find any records indicating that Lieutenant Britton received an award). Kidd served until 1964, but was not extensively modified. Now a museum ship in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Kidd is the closest of the three surviving Fletcher-class destroyers (The Sullivans [DD-537] in Buffalo and Cassin Young [DD-793] in Boston) to the class’s World War II configuration.

At 1507 that same day, the carrier Essex (CV-9) suffered a near miss from a bomb on the port side that did extensive damage to the engineering plant, fuel tanks, and some of her electronics. Essex lost 33 men killed, with another 33 wounded. Of the 11 fleet carriers at the start of the campaign, five were out of action at least temporarily due to Japanese air attacks.

12–13 April

Kikusui No. 2 consisted of 185 kamikaze aircraft (125 navy and 60 army) with additional aircraft for conventional attacks and escorts (and those would turn themselves into kamikazes if they were damaged and the pilot didn’t think he could make it back).

12 April

The weather on 12 April was described as “gorgeous,” and the Japanese attacked with 185 kamikaze, accompanied by 150 fighters and 45 torpedo bombers. At 0600, about 25 Japanese aircraft approached the northern radar picket station. A few were shot down by night fighters still on station, but most made it through to the beachhead area, where they were driven off by shipboard anti-aircraft fire. The main attacks commenced in the afternoon.

Radar Pickett Station No. 1—Purdy (DD-734), Cassin Young (DD-793), LCS (L)-33*, and LCS (L)-57. A lesson from Kikusui No. 1 was not to have lone destroyers on radar picket stations, so Purdy and Cassin Young were doubled up on Station No. 1 and accompanied by four large support landing craft. In the afternoon of 12 April, 30 Val dive-bombers commenced an attack. Cassin and Purdy combined to down several kamikaze. Then, at about 1340, a kamikaze made a run at Cassin Young and was shot down, hitting the water only 15 feet away. She shot down another kamikaze before a third flew into the port yardarm and fell in pieces on the ship, knocking out the forward fire room. Although 59 men were wounded, only one was killed. As this was happening, Purdy shot down another kamikaze. Cassin Young departed for repairs at Kerama Retto and then Ulithi. She would return to Okinawa in June and get hit again—worse—in July.

At 1441, another raid of Vals came in on Station No.1. One Val kamikaze dove on LCS(L)-33 and barely missed, carrying away radio antennas before hitting the water. Then, two more dove from opposite directions. LCS (L)-33 got one of them, but the other crashed amidships, setting fire to most of the vessel and knocking out all the pumps. The skipper ordered abandon ship, with four dead and 29 wounded. At the same time, despite shooting down three kamikaze, LCS(L)-57 was hit on her forward 40-mm mount, another blew a hole in her side as it crashed close aboard, and then a third kamikaze hit forward. Shortly after, LCS(L)-33 was hit by yet another kamikaze, which ensured she sank. LCS(L)-57 suffered two dead and six wounded and, despite being damaged by three kamikaze, made it to Kerama Retto under her own power.

As the LCSs were getting hit, another Val came at Purdy with three U.S. fighters in hot pursuit. Purdy held fire to avoid hitting the friendlies, but finally had to open up. She hit the Val with a 5-inch shell and the kamikaze hit the water 20 feet short, but bounced into the side and its bomb exploded, blowing ten men overboard. Purdy lost most of her power and jettisoned her torpedoes. Conned from after steering, Purdy limped to the Hagushi roadstead with 13 dead and 27 wounded.

Mannert L. Abele (DD-733)* and LSM(R)-189##. Kikusui No.2 saw the first use of the Japanese MKY7 Ohka rocket-boosted suicide flying bomb, and destroyer Mannert L. Abele was the first victim. The Ohka (“Cherry Blossom”) was a human-guided, purpose-built flying bomb with a 2,645-pound warhead. The U.S. term for the Ohka was “Baka” (Japanese for “stupid” or “idiot”). The Ohka would be carried to the target area slung beneath a modified G4M Betty twin-engine bomber at high altitude. The Ohka would initially glide toward the target before the pilot fired the three solid-fuel booster rockets (in series or simultaneously) and hit the target at anywhere from 500 to 620 knots depending on the angle of dive. The speed of the Ohka made it almost impossible to hit with the anti-aircraft weapons of the time, but effectively controlling it to hit the target was a significant problem for the Japanese. Ohka pilots were members of the “Thunder Gods Corps.”

Mannert L. Abele was operating at Radar Picket Station No. 4 northeast of Okinawa in company with LSM(R)-189 and LSM(R)-190 (these were medium landing ships converted to fire a barrage of unguided rockets in support of beach landings). At 1345, three Japanese Val dive-bombers commenced to attack. Two were driven off, but one on fire attempted to hit LSM(R)-189—it missed. At 1400, between 15 and 25 Japanese aircraft began circling Mannert L. Abele outside anti-aircraft range. At 1410, three Zeke fighters departed the orbit and attacked, but one was driven off and another shot down. However, the third Zeke, in smoke and flames from numerous hits, crashed into the destroyer’s starboard side and penetrated the after engine room, where the plane’s bomb exploded and destroyed the power plant and broke the keel. Mannert L. Abele lost power, went dead in the water, and was probably already done for.

About a minute after the Zeke hit Mannert L. Abele, an Ohka slammed into the ship with an explosion so powerful that her amidships section disintegrated and she broke in two, both bow and stern sections sinking rapidly. Japanese planes then bombed and strafed survivors in the water until the two LSM(R)’s shot down two of the attackers. Then, a kamikaze crashed into LSM(R)-189, wounding four, but she continued rescuing survivors along with LSM(R)-190. Mannert L. Abele suffered 84 dead and over 30 wounded. LSM(R)-189 would be awarded a Navy Unit Commendation, but would not be repaired before the end of the war. LSM(R)-190 would be sunk on 4 May.

The Japanese used at least two more Ohka on 12 April. As destroyer Stanley (DD-478) was steaming at high speed to replace Cassin Young at Radar Picket Station No. 1, an Ohka came out of a swarm of Japanese aircraft being engaged by combat air patrol and hit Stanley in the forward bow area. The Ohka passed right through the ship and exploded on the far side, mangling the bow and wounding three, but not causing enough damage to keep her from operating. Several minutes later, a second Ohka took aim at Stanley, but at the last moment, the pilot was either killed or lost control, and the Ohka missed high, ripping the ensign from the gaff, and impacting the ocean on the far side.

Tennessee (BB-43) and Zellars (DD-777)##. In anticipation of major Japanese kamikaze attacks on 12 April 1945, the commander of the Gunfire and Covering Force (Task Force 54—TF 54) directed his ships to remain in an anti-aircraft disposition throughout the day. Ten battleships, four heavy cruisers, and three light cruisers steamed in a circular formation off southwestern Okinawa with 12 destroyers in an outer ring. The attack did not materialize until after 1400, showing as 11 different groups on radar. At 1450 three Jill torpedo bombers came in on the axis defended by destroyer Zellars at about 15 feet above the water. Zellars knocked down the first Jill and then the second. Despite repeated 40-mm hits, the third Jill kept coming and crashed into the destroyer’s port side in the Number 2 ammunition-handling room and its bomb exploded on the starboard side of the ship, inflicting serious damage and a wall of fire. Zellars temporarily lost all power, but her gunners aft continued to fire and helped down another plane.

Destroyer Bennion (DD-662) came alongside and transferred her doctor to Zellars to assist with the wounded. Two of Bennion’s sailors jumped overboard to rescue an officer from Zellars who had been blown overboard and unfortunately later died from his burn wounds. Bennion also suffered seven wounded when a “friendly” anti-aircraft shell sprayed one of her 40-mm mounts. Zellars’ crew put out the fires, restored power, and the destroyer made her way to Kerama Retto. The commanding officer of Zellars, Commander Leon S. Kintberger, was awarded a Silver Star. Kintberger had previously been awarded a Navy Cross in command of destroyer Hoel (DD-533) when she was lost in an heroic action against overwhelming odds in the Battle off Samar in October 1944.

More Japanese aircraft used the smoke from the burning Zellars to obscure their run at battleship Tennessee, Rear Admiral Morton Deyo’s flagship (CTF 54). Gunners on Tennesse shot down five aircraft that got progressively closer before being splashed, but a Val dive-bomber coming in at low altitude at the same time from a different direction made it through the gauntlet. The plane was heading right for the bridge when a last-second hit deflected it into a 40-mm mount manned by Marines (who had fired on the aircraft to the very end), killing or badly wounding all 12 Marines in the gun crew. Parts of the plane and flaming gasoline sprayed over many of the exposed gun positions before the plane came to rest by the Number 3 14-inch turret. One of the Marines escaping the flames jumped from the 40-mm mount to a 5-inch mount and then fell overboard, ending up in a large raft that had also been blown overboard. By chance, the kamikaze pilot’s body had also ended up in this raft. The Marine was rescued three hours later. The bomb on the kamikaze penetrated into warrant officer country, where it exploded. Tennessee suffered 25 killed and 104 wounded (significantly more than she suffered when hit by a bomb at Pearl Harbor), and many of the wounded suffered horrible burns from the flaming gasoline.

The attacks on TF 54 continued into the night and many Japanese planes were shot down, but no other U.S. ships suffered serious damage. Despite the casualties and damage, TENNESSE made emergency repairs and remained on the gun line for another two weeks before undergoing more extensive repairs at Ulithi, returning to Okinawa in June.

Whitehurst (DE-634). Destroyer escort Whitehurst was on anti-submarine patrol southwest of Kerama Retto screening TF 54, when she was attacked simultaneously from three directions by three Japanese planes around 1500. In a by now depressingly familiar pattern, Whitehurst’s gunners brought down two and damaged a third, but the Val crashed directly into the ship’s combat information center, its bomb passing through the ship and exploding just outside on the opposite side, knocking out her forward guns. The bridge and signal bridge areas were decimated and, for a while, Whitehurst circled out of control. Vigilance (AM-324) sped to Whitehurst’s assistance, and many of Whitehurst’s wounded were transferred to the minesweeper, where the provision of blood plasma saved many who would otherwise have died. As it was, 42 of Whitehurst’s crew died and over 35 were wounded. After her crew put out the fires, Whitehurst was able to make Kerama Retto under her own power.

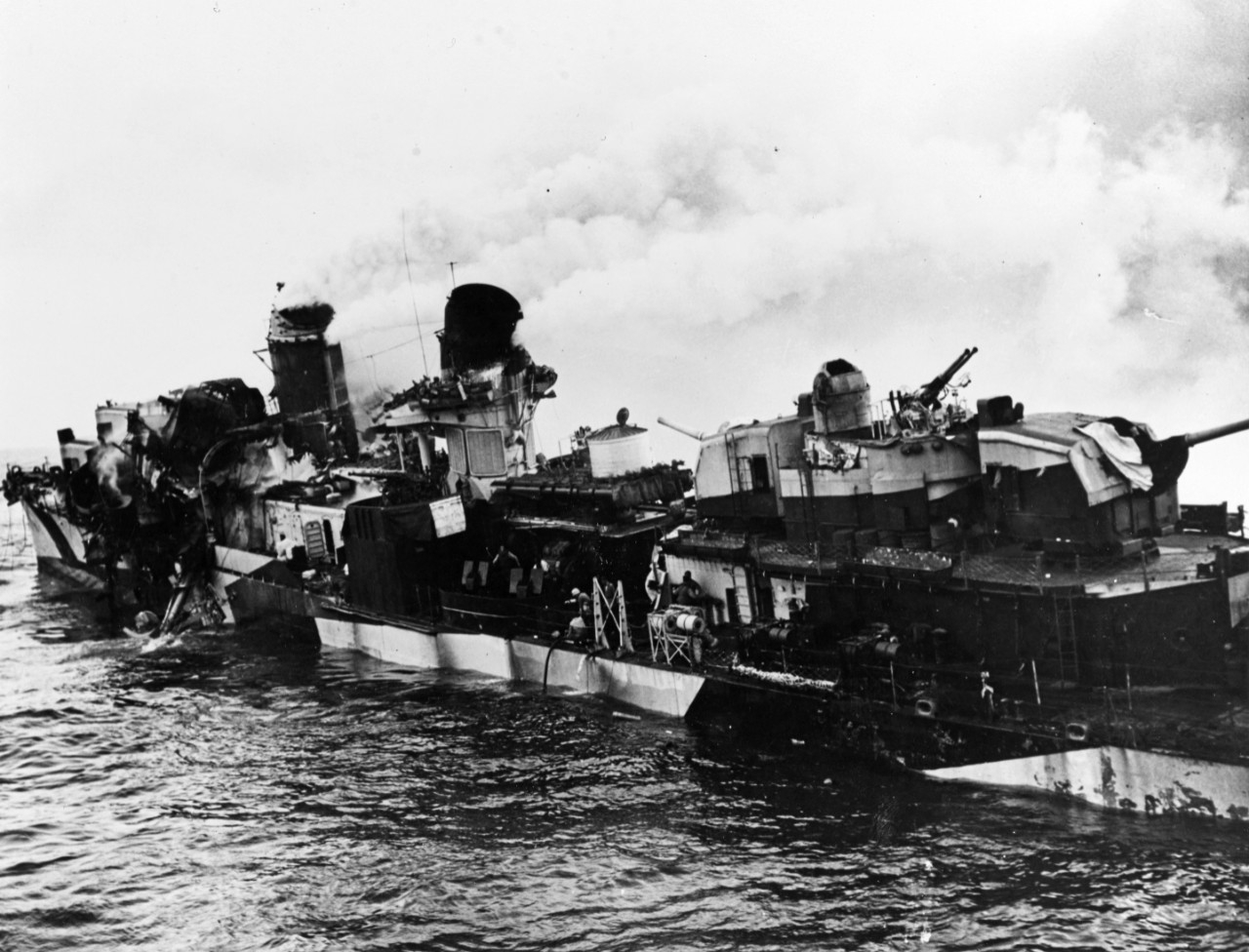

Lindsey (DM-32)##. At 1450, destroyer-minesweeper Lindsey was attacked by seven Val dive- bombers. Her gunners scored repeated hits on the aircraft, driving off most, but two damaged Vals crashed into the ship. One of them hit forward and caused an explosion that blew the Number 1 gun turret right off the ship along with everything forward. Commanding officer Commander T. E. Chambers ordered all back full, which prevented Lindsey from driving herself under the water. If the foreward fire room’s forward bulkhead had collapsed, the ship would have been lost. With superb damage control, Lindsey remained afloat and was towed into Kerama Retto, but the cost was high: 56 killed and 51 wounded. Lindsey received a temporary bow at Guam and returned to the States, but repairs were not completed before the war ended.

Rall (DE-304). While conducting an anti-submarine patrol off Okinawa in the early evening of 12 April, Rall was attacked by five kamikaze. Her gunners shot down the first kamikaze and a nearby cruiser shot down a fourth, but the fifth damaged and burning aircraft crashed into Rall’s starboard side aft. The plane’s 500-pound bomb tore through the ship and out the port side before exploding about 15 feet away. Then, several Japanese fighters came through and strafed the ship while damage control efforts were underway. At a cost of 21 dead and 38 wounded, the crew of Rall got the fires under control, brought her in to Kerama Retto, and then back to Seattle for repairs. (Previously, in November 1944, Rall had sunk a Japanese Kaiten manned torpedo that penetrated the anchorage at Ulithi.)

Despite the large-scale Japanese effort in Kikusui No. 2, U.S. losses fell far short of expectations (and certainly of Japanese claims), but were nonetheless painful for the U.S. Navy. Destroyer Mannert L. Abele and LCS(L)-33 had been sunk. Destroyer Zellars, destroyer-minesweeper Lindsey, and LSM-189 were out of action for the rest of the war. Battleship Tennessee, destroyers Purdy and Cassin Young, destroyer escorts Rall and Whitehurst, and LCS(L)-57 were out of action for over a month. About 270 U.S. crewmen were killed and about 430 wounded.

13 April

On Friday night, U.S. Navy forces off Okinawa learned that President Franklin Roosevelt had died. For many of the young sailors in the fleet Roosevelt was the only president they had known. By order of Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, memorial services were held on every ship in the Navy on 15 April.

14 April

Sigsbee (DD-502)##. On 14 April 1945, 15 kamikaze came after the TF 58 and attacked destroyers on radar picket duty. One kamikaze hit a glancing blow on destroyer Hunt (DD-674) after being riddled by Hunt’s gunners. The plane’s starboard wing stuck in Hunt’s forward funnel, her mainmast was carried away, and the aircraft’s fuselage crashed on the opposite side of the ship. (Hunt had previously rescued 429 survivors of the carrier Franklin [CV-13] when she was gravely damaged 50 nautical miles off the coast of Japan on 19 March 1945.)

Five minutes after Hunt’s close encounter, another kamikaze hit destroyer Sigsbee, blowing off the stern aft of the Number 5 5-inch gun mount, causing her to lose steering, her port shaft, and to take on a lot of water. The ship was in serious danger of sinking, settling almost to the main deck. Her commanding officer, Commander Gordon Paiea Chung-Hoon, was given permission to scuttle the ship, but he refused, saying he could save her. As damage control parties stopped the flooding, Sigsbee’s gunners continued to engage additional Japanese aircraft. Although Sigsbee only suffered four dead, 74 were wounded. Sigsbee was towed to Kerama Retto. Commander Chung-Hoon was awarded the Navy Cross (to go with a Silver Star received while in command of Sigsbee when the ship assisted in the destruction of 20 Japanese planes off Japan on 17 March 1945). Chung-Hoon would go on to be the first Asian-American to achieve flag rank in the U.S. Navy (although this was technically a “tombstone promotion” accorded to World War II officers who had distinguished themselves in battle when they retired). The Arleigh Burke-class destroyer DDG-93, commissioned in 2004 is named in his honor.

15–16 April

The Japanese plan for Kikusui No. 3, scheduled for 15–16 April, included a total of 165 kamikaze aircraft (120 navy, 45 army), with additional aircraft in conventional strike and escort roles. The Japanese did not actually have a schedule for the mass kamikaze raids. Such raids were executed irregularly when enough aircraft were rounded up, with enough volunteer pilots, to get a large mass. The Kikusui were also about the first time in the war during which the Japanese army and navy operated in anything approaching a “joint” manner, and Kikusui would include formations of army and navy aircraft conducting simultaneous attacks.

16 April

Intrepid (CV-11). On 15 April, with intelligence warning of Kikusui No. 3., TF 58 went on the offensive with large-scale fighter sweeps over Japanese airfields on Kyushu, shooting down about 30 aircraft and destroying about another 50 on the ground on 15 April, which no doubt kept the Japanese attack from being worse. The major kamikaze attack occurred on 16 April and some of the kamikaze went after TF 58 carriers, although the majority still went after the ships closer to Okinawa.

At 1336 on 16 April, two kamikaze made it through the gauntlet of fighters and anti-aircraft artillery fire and attacked carrier Intrepid. One kamikaze just missed hitting her flight deck and hit the water close aboard. The second crashed through the flight deck near the aft elevator, blowing a 15-by-20-foot hole in the flight deck; the engine and fuselage went into the hanger. Within 30 minutes, the fires were under control and, after three hours, aircraft recovered on the carrier. Intrepid suffered 10 dead and 87 wounded. The structural damage was bad enough that Intrepid had to proceed to Ulithi for repairs and then to San Francisco via Pearl Harbor. She was the sixth of 11 fleet carriers to be knocked out of action by Japanese kamikaze and air attacks.

Laffey (DD-724)##. Kamikaze and bomb attack, 31 dead, 72 wounded (please see attachment H-045-1).

Bryant (DD-665)##. Destroyer Bryant was on Radar Picket Station No. 2 when she received word of the mass attack on Laffey. The commanding officer, Commander George Seay, did not hesitate to speed toward Laffey to render assistance, damage control teams at the ready. At 0934, six planes made a coordinated attack on Bryant. First, three Zeke fighters came in. One was shot down by a friendly fighter, another by Bryant’s gunners, but the third, battered and trailing smoke, hit the destroyer at the base of her bridge, wiping out the combat information center and main radio. Then, the bomb exploded, knocking out the radars, communications, and surrounding the bridge in flames. Even with the interior of the bridge on fire and exploding ammunition outside, Seay remained on the bridge directing damage control and continued engagement of Japanese aircraft. Bryant’s crew got the fires under control in about 30 minutes and, with word that other ships were standing by Laffey, Bryant made her way to Kerama Retto with 34 dead and 33 wounded. She returned to the San Francisco for repairs that were not completed before the war ended. Commander Seay would be awarded a Silver Star.

Pringle (DD-477)* and Hobson (DM-26, formerly DD-464)##. Destroyer Pringle, destroyer-minesweeper Hobson and medium landing ship LSM-191 were at Radar Picket Station No. 14 northwest of Okinawa when three Val kamikaze came in on attack at 0910 on 16 April. Pringle shot down two of them, but the third made a direct hit on the bridge and crashed through the superstructure all the way to the base of the forward stack, where the 1,000-pound bomb (or two 500-pound bombs) exploded, breaking the keel and severing the ship in two. Both halves sank in less than five minutes, taking 62 men to the bottom. Other ships rescued 258 crewmen, of whom 110 were wounded and three subsequently died. The skipper, Lieutenant Commander John Kelley, survived and was awarded a Silver Star.

Two minutes after Pringle was hit, a kamikaze attacked destroyer-minesweeper Hobson. A hit from a 5-inch shell at point-blank range obliterated the aircraft, but the plane’s bomb hit the ship in the after deck house, apparently with a delayed fuse. The bomb detonated, destroying workshops and blowing a hole in the deck over the forward fireroom, knocking out steam and power lines. As damage control teams fought the fires, two more planes came in for attack and were shot down by Hobson’s gunners. Once the situation was under control, Hobson rescued 136 of Pringle’s 258 survivors and LSM-191 and another unidentified gunboat rescued the rest. Hobson suffered four dead and eight wounded. She was able to reach Kerama Retto on her own and then ultimately headed for Norfolk for repairs that weren’t finished before the war ended. Hobson’s skipper, Commander Joseph I. Manning, was awarded a Navy Cross. (Hobson was rammed and sunk by the carrier Wasp [CV-18] on 26 April 1952 with the loss of 171 of her crew in the worst accidental loss of life in the U.S. Navy since World War II.)

Bowers (DE-637)##. Destroyer escort Bowers was an antisubmarine patrol west of Okinawa at dawn when she shot down a Japanese plane. At 0930, two more came in to attack at low altitude. Bowers attempted radical maneuvers—to no avail as the aircraft split to attack her from different directions. Bowers’ forward guns shot down one plane directly ahead. The second actually passed over the ship from behind and then looped over and crashed into the bridge from ahead, spraying flaming gasoline all over the bridge and pilot house, and severely wounding the commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander S. A. Haavik. The plane’s bomb penetrated into the superstructure and exploded. Damage control teams fought the fires for 45 minutes before bringing them under control. Bowers suffered 48 dead and 56 wounded, but was able to reach the Hagushi anchorage under her own power, and then to Philadelphia. Repairs and conversion to a high-speed transport were incomplete when the war ended.

Harding (DM-28, formerly DD-625)#. Destroyer-minesweeper Harding was en route to relieve Hobson on Radar Picket Station No. 14, when she was attacked by four Japanese aircraft just before 1000. The first plane broke off in the face of intense anti-aircraft fire and the second was shot down. The third ran the gauntlet and almost hit Harding’s bridge before crashing close aboard. The plane’s bomb exploded and blew a 20-by-10-foot gash from her keel to the main deck, bending her keel. Harding was able steam backward to Kerama Retto, having suffered 22 dead and ten wounded. Although she returned to Norfolk, she was not fully repaired. Harding’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Donald B. Ramage, was awarded a Silver Star.

LCS(L)-116. Large support landing craft LCS(L)-116 was operating about six miles east of Laffey when the destroyer was attacked (see attachment H-045-1).

Kikusui No. 3 succeeded in sinking the destroyer Pringle, putting the destroyers Bryant and Laffey, destroyer-minesweepers Hobson and Harding, and destroyer escort Bowers out of action for the duration of the war. Carrier Intrepid was also put out of action for over 30 days. About 225 U.S. crewmembers were killed and about 390 wounded.

17 April

At 2305, while operating east of Okinawa, battleship Missouri’s radar detected a surfaced contact 12 nautical miles from the carrier task group. Escort carrier Bataan (CVE-29) and five destroyers formed a hunter-killer group. Heermann (DD-532), repaired and still under the command of Commander Amos Hathaway after her heroic action in the Battle off Samar (for which Hathaway received a Navy Cross), along with Uhlmann (DD-697), Collet (DD-730), McCord (DD-534), and Mertz (DD-691), conducted multiple attacks. The contact was assessed to be I-56, one of the Tatara Group of Kaiten submarines that departed Japan on 28 March. I-56 was lost with all 116 hands plus six Kaiten pilots.

18 April

Medium landing ship LSM-28 was damaged as a result of Japanese air attack, but suffered no casualties. However, the vessel was out of action for more than 30 days.

20 April

The sixth Kaiten submarine group deployed from Japan was the Tembu (“Heavenly Warrior”) Group. It consisted of I-47, which departed 20 April, and I-36, which departed 22 April, each with six Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes embarked.

22 April

Isherwood (DD-520)##. Destroyer Isherwood was protecting the Hagushi anchorage area at dusk on 22 April, when a lone Val dive-bomber came out of the setting sun and crashed into the Number 3 5-inch gun mount and the plane’s bomb detonated, starting numerous fires. Damage control parties fought the fires for 25 minutes, getting all under control except for one in the depth-charge rack aft. A depth charge exploded, setting off the other depth charges in a large explosion, which severely damaged the aft end of the ship and the after engine room. Casualties were heavy as a result of the kamikaze hit and the depth-charge explosion, with 42 dead and 41 wounded. Isherwood was brought into Kerama Retto for emergency repair and later she steamed to San Francisco, where her repairs were not completed until just after the war ended.

LCS(L)-15*. At 1830, a kamikaze made a direct hit on large support landing craft LCS(S)-15 and the plane’s bomb exploded, sinking the vessel in three minutes. LCS(L)-15 lost 15 crewmen and suffered 11 wounded.

Swallow (AM-65)*. At 1858, a kamikaze burst out of low clouds and hit the minesweeper Swallow on her starboard side amidships at the waterline. Both engine rooms immediately flooded and the ship was listing 45 degrees at 1901, when the abandon ship order was given. Swallow capsized and sank three minutes later. She suffered two dead and nine wounded.

25 April

The Japanese deployed another conventional submarine, RO-109, to the Okinawa area in mid-April. Destroyer-transport Horace A. Bass (APD-124), Lieutenant Commander F. W. Kuhn in command, was escorting a 17-ship convoy from Guam to Okinawa when she picked up a sonar contact at 1,250 yards at 1804. The ship dropped five depth charges while the submarine commenced evasive maneuvers and attempted to jam her sonar with well-tuned sound impulses. Contact was lost after the depth-charge explosions, but then regained, and Horace A. Bass dropped five more depth charges. This time, the submarine went deep and appeared to use sonar decoys that generated multiple false targets, which may have been a German “Bold”-type decoy. Horace A. Bass made six more attacks and, after the last one shortly after 2000, debris and oil came to the surface. This was assessed to be RO-109, lost with all 65 hands.

27–28 April

The fourth Japanese mass kamikaze attack, Kikusui No. 4, included 115 kamikaze (65 navy and 50 army aircraft), along with additional conventional strike and escort aircraft.

27 April

Japanese submarine I-36, which had departed Japan on 22 April as part of the Tembu Kaiten Group, sighted a 28-ship convoy (a mix of LSTs and LSMs) east of Okinawa. I-36 closed on the convoy intending to launch four Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes, but two malfunctioned and only two were launched. Destroyer-transport Ringness (APD-100) sighted a torpedo wake at 0832 and a periscope, and then two more torpedo wakes. Destroyer escort Fieberling (DE-460) sighted another torpedo wake. No ships were hit and I-36 escaped. There was no way to recover a Kaiten, so those were one-way missions for the pilots whether they hit or missed.

Hutchins (DD-476)#. U.S. Navy ships continued to provide extensive gunfire support to U.S. Army and Marine forces ashore on Okinawa throughout the campaign, with the risk of attack by suicide boat an ever-present danger. Many suicide boats were destroyed in “flycatcher” operations, but, on 27 April, one got close enough to the destroyer Hutchins for the boat’s charge to do major damage. No one on Hutchins was killed or wounded. However, damage to the hull and machinery was extensive and she was brought in to Kerama Retto for emergency repairs, and then to Bremerton, where repairs were never completed.

Rathburne (APD-25)#. The World War I–vintage destroyer Rathburne, converted to a fast destroyer-transport, was patrolling in the Hagushi gnchorage area on 27 April, when she detected an incoming aircraft on her radar. Maneuver and gunfire failed to stop the kamikaze from hitting the port bow at the waterline. Luckily, no crewmen were killed or wounded, but a number of compartments were flooded and fires broke out, all of which were brought under control. Rathburne made it to Kerama Retto for emergency repairs and then to San Diego, where repairs were not completed. (Rathburne was actually named after John Rathbun, John Paul Jones’ first lieutenant, but the name was misspelled at commissioning in 1918. The Knox–class frigate Rathburne [FF-1057], in service 1970–92, perpetuated the misspelling, being named after the first Rathburne.)

Canada Victory*. The merchant ship Canada Victory, reconfigured to carry ammunition, was off the Hagushi beachhead on 27 April when a kamikaze crashed into her stern, causing a large explosion in hold Number 5 and causing her to sink in ten minutes with 12 killed and 27 wounded. Fortunately, there was no catastrophic explosion in the roadstead. The loss of Canada Victory, along with the earlier sinkings of ammunition ships Logan Victory and Hobbs Victory, had significant adverse impact on the ground campaign. Among the 24,000 tons of lost ammunition were almost all the 8-mm mortar shells that were vital in hitting Japanese troops otherwise protected on the reverse slopes of fortified ridges.

28 April

Pinkney (APH-2)##. The evacuation transport Pinkney had been off the Hagushi beachhead for several days as casualties were brought on board from the fighting ashore and ships hit by kamikaze. At 1730 on 28 April, Pinkney was hit in on the aft side of her superstructure by a kamikaze spotted only moments before. Sixteen patients were killed in the initial explosion and the rest were evacuated despite a raging fire and ammunition cooking off. The crew fought the fire and threw live ammunition over the side as tugs and landing craft came alongside to fight the fires and evacuate the wounded. The ship listed heavily to port while fires burned out all the medical wards and took three hours to put out. Pinkney lost 18 of her own crew with another 12 wounded, but kept the ship from sinking. She sailed for San Francisco, but repairs were not complete before the war ended. (Pinkney was one of three Tryon-class evacuation transports, which were modified personnel transports with extensive medical facilities. The armed ships, which did not have Geneva Convention protection as hospital ships, operated as assault transports on the way to a landing and then as hospital ships to evacuate wounded while the landing was underway. The ships carried 8–12 doctors and 60 hospital corpsmen (no nurses), could transport 1,150 patients, and had 300 intensive-care beds for severely wounded, two main operating rooms, and two “overflow” surgeries.)

USS Comfort (AH-6) and Awa Maru

Comfort (AH-6). On the evening of 28 April, the hospital ship Comfort had departed Okinawa fully loaded with wounded and was 50 nautical miles southeast of the island and heading for Saipan. Comfort was fully lit and carried large red cross markings in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Moreover, the moon was full. At 2041, a Japanese plane first made a close pass at masthead height and then made a 360-degree turn and dove into Comfort’s amidships superstructure. It penetrated through three decks into the surgery, killing all the medical personnel and patients there. (Unlike most other Navy hospital ships, Comfort was one of three 700-bed hospital ships manned and operated by the Navy for the U.S. Army; the medical staff were all Army personnel). Two sailors and 21 Army personnel, including six Army nurses, plus seven patients were killed. Seven Sailors, 31 Army personnel (including four nurses), and ten patients were wounded. Topside damage was considerable, but the engineering spaces were unaffected, so Comfort was able to continue on to Guam and then Los Angeles for repairs. Navy hospital ships Relief (AH-1) and Solace (AH-5) were also attacked by Japanese planes off Okinawa in April 1945, but Comfort was the only one to suffer damage or casualties.

There is some evidence, and a lot of speculation, that the attack on Comfort (and possibly on the other hospital ships) was deliberate retaliation for the sinking of a Japanese-declared Red Cross ship, Awa Maru, by the submarine Queenfish (SS-393) on 1 April, which resulted in the loss of all but one of 2,004 people aboard. The Japanese claimed it to be “the most outrageous act of treachery unparalleled in the history of world war” and, in a radio Tokyo broadcast on 9 April, stated that “We are justified in bombing hospital ships as they are being used as repair ships for returning wounded men back to the fighting front.” A document recovered from the dead kamikaze pilot had a list of U.S. ships off Okinawa, including two hospital ships.

The 11,600-ton Awa Maru was designed as a passenger ship, but was requisitioned by the Japanese navy when it was completed in 1943. The ship made several convoy runs in 1944 transporting military cargo, and was even beached after it had been hit by torpedo from a U.S. submarine wolfpack on the night of 18–19 August 1944. The ship was recovered and repaired, and, in 1945, was declared under the terms of the “Relief for POWs Agreement” as a Red Cross relief ship carrying humanitarian supplies to U.S. and Allied POWs in Japanese control.

After completing a relief run to Singapore in March 1945, Awa Maru then took onboard about 1,700 Japanese merchant sailors (survivors of previous sinkings), as well as a number of military personnel, diplomats, and civilians. It also took on a cargo of rubber, metal (nickel, lead, tin—accounts vary), and possibly sugar, but definitely no Red Cross supplies. The ship was also rumored to have loaded an extremely valuable cargo of gold and other precious materials. These were the result of years of “treasure hunting,” in Asia (the ship was also rumored to be carrying fossilized remains of “Peking Man,” the 750,000-year-old Homo erectus, one of the earliest finds of Homo sapiens’s ancestors). Regardless, the Japanese declared Awa Maru as a Red Cross ship and, as required, provided the track to the Allies. On 28 March, Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood, the commander of Submarine Force Pacific (SUBPAC), sent a message to all U.S. submarines not to sink it. The SUBPAC message was notably lacking in specifics, beyond the dates of March 30 to 4 April for the transit from Singapore to Japan. The message did note that Awa Maru would be lighted at night and “plastered with white crosses.” However, as Awa Maru transited the Taiwan Strait at night and in dense fog on 1 April, Queenfish mistook the ship for a destroyer and sank her with four torpedoes.

Queenfish rescued one Japanese survivor, the captain’s steward (who was also the sole survivor of two previous sinkings), who revealed that the ship was Awa Maru. The skipper of Queenfish, Commander Charles E. Loughlin (who had been awarded two Navy Crosses and a Silver Star for his first three war patrols on Queenfish—this was the fourth for sub and skipper), immediately reported the sinking. CNO Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King ordered an immediate return to port for Queenfish and relief from command and general court-martial for Loughlin. Although the Awa Maru was not in use as a hospital ship or carrying relief supplies (or sounding its foghorn as required), these facts were deemed irrelevant as it was under declared Red Cross protection and orders had been given not to sink it.

The court-martial dismissed the charge of “culpable inefficiency in the performance of duty and disobeying the lawful order of a superior,” but found Loughlin guilty of “negligence,” with a punishment of a Secretary of the Navy Letter of Admonition. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz determined this to be too lenient and sent Letters of Reprimand to the Board members (a higher punishment than given to Loughlin—it would be interesting to see what JAGs would think of that today). King ordered that Loughlin not be given another command, which was apparently forgotten after the war as Loughlin went on to command Mississenewa (AO-144) and Toledo (CA-133) before making rear admiral and commanding Submarine Flotilla 6. He finished his career in 1968 as the Commandant of the Washington Naval District. An extensive search of the Awa Maru wreck (found in 1977) by China in 1980 found no treasure.

Awa Maru was one of 24 hospital ships sunk by hostile action during World War II (one Japanese hospital ship sank due to a collision), three of which were sunk in the Pacific Theater. On 14 May 1943, the Japanese submarine I-177 sank the Australian hospital ship Centaur, which went down in a matter of minutes with the loss of 268 of 332 aboard. I-177 was sunk with all hands by Samuel S. Miles (DE-183) on 3 October 1943 with all 101 hands. However, the skipper who sank Centaur had transferred and survived the war. A war crimes trial was unable to prove he knowingly sank a hospital ship, but he did admit to machine-gunning survivors in the water on three previous occasions in command of a different submarine and was convicted of that.

On 27 November 1943, the Japanese hospital ship Buenos Aires Maru was hit by a bomb and sunk by a probable U.S. Army B-24 four-engine bomber. Although reportedly an accident, Buenos Aires Maru was well marked, the plane was only at 300 feet altitude, and the Japanese claimed it strafed survivors. The Japanese rescued about 1,000 survivors, but 158 were lost, including some number of Japanese nurses (63 were on board). The Southwest Pacific Theater command surgeon recommended that the United States apologize for the sinking, but General Douglas MacArthur refused and no apology was ever given. Buenos Aires Maru had also been previously hit and damaged by a torpedo from submarine Runner (SS-275) on 25 April 1943, and nothing untoward seems to have happened to the skipper as he made rear admiral (Runner was lost with all hands on 26 June 1943). The last hospital ship sunk in the Pacific was the Japanese Hikawa Maru No. 2 (a former Dutch hospital ship captured by the Japanese) that was sunk by a scuttling charge on 14 August 1945.

Kikuisan No. 4 didn’t accomplish much for the Japanese. The ammunition ship Canada Victory was sunk, along with some much-needed ammunition. The destroyer Hutchins and destroyer-transport Rathburne were saved by their crews, but were too damaged to repair. The evacuation transport Pinkney and hospital ship Comfort were seriously damaged. U.S. casualties were 77 dead and 87 wounded. The dead included 27 Army personnel, among them six nurses and ten patients, aboard Comfort.

29 April

Haggard (DD-555)#. On the late afternoon of 29 April, TF 58 destroyer Haggard had just joined Uhlmann (DD-687) on a radar picket station when Japanese aircraft attacked. One Zeke kamikaze was taken under fire by both Uhlman and Haggard. Hit repeatedly, the Zeke crashed into Haggard amidships at the waterline at 1657. After a delay, the plane’s bomb exploded, and the forward engine room and both fire rooms flooded and the ship was in danger of sinking. Another Zeke made an attack run and was shot down by Uhlmann, crashing just short of Haggard. As Haggard jettisoned torpedoes and depth charges, Uhlmann rescued two of Haggard’s crew, who had been blown overboard. Damage control teams on Haggard prevented progressive flooding, as Uhlmann radioed for back-up and combat air patrol arrived overhead, followed an hour later by the anti-aircraft light cruiser San Diego (CL-53) and destroyer Walker (DD-517). Fortunately, the sea was relatively calm and Walker towed Haggard to Kerama Retto. Haggard’'s casualties were 11 killed and 40 wounded. Due to the number of damaged ships at Kerama Retto, it took until 18 June before she was able to get underway for San Diego. Due to the extent of damage, she was scrapped instead of being repaired.

Haggard and Uhlmann had teamed up previously to sink Japanese submarine RO-41, which had been sent out to intercept the Fast Carrier Task Force strikes on Japan on 18/19 March. As TG 58.4 was exiting the area to the south, Haggard and Uhlmann gained radar contact at 25,000 yards and the two destroyers were ordered to investigate. After the contact submerged, Haggard gained sonar contact and, while Uhlmann provided over watch, Haggard dropped depth charges. Just before midnight, the submarine broached just off Haggard’'s port beam. Haggard opened up with 40-mm fire, damaging the submarine’s conning tower, before Haggard’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander V. J. Soballe, gave the order to ram the submarine. Haggard smashed her bow, but the submarine rolled over and sank with “explosions of gratifying violence.” RO-41 was lost with all 82 hands. Uhlmann escorted Haggard to Ulithi for repairs.

Hazelwood (DD-531). As destroyer Hazelwood was steaming to assist Haggard on 29 April, three Zekes dropped out of the overcast. Hazelwood shot down one, which crashed close aboard, and the other Zeke missed. The third Zeke came in from astern. Although hit multiple times, it clipped the portside of the aft stack and then crashed into the bridge from behind, toppling the mainmast, knocking out the forward guns, and spraying flaming gasoline all over the forward superstructure. Its bomb exploded, killing the commanding officer, Commander Volkert P. Douw, and many others, including Douw’s prospective relief, Lieutenant Commander Walter Hering, and the executive officer and ship’s doctor.

The engineering officer, Lieutenant (j.g.) Chester M. Locke, took command of Hazelwood and directed the crew in firefighting and care of the wounded. Twenty-five wounded men had been gathered on the forecastle when ammunition began cooking off. Because of the danger of imminent explosion, the destroyer McGowan (DD-678) could not come alongside close aboard. The wounded were put in life jackets, lowered to the water, and able-bodied men dove in and swam them to McGowan. Only one of the wounded men died in the process. Hazelwood’'s crew got the fires out in about two hours and McGowan took her in tow until the next morning, when Hazelwood was able to proceed to Kerama Retto under her own power and, from there, to the West Coast for repairs. Although Morison gives a casualty count as 42 killed and 26 wounded, multiple other sources state 10 officers and 67 enlisted men were killed and 36 were wounded. Locke was awarded a Navy Cross.

LCS(L)-37.# Large support landing craft LCS(S)-37 was damaged by a Japanese suicide boat on 28 April. Four men were wounded and the damage was deemed beyond economical repair. She was scuttled over the Philippine Trench in March 1946.

On the afternoon of 29 April, a VC-92 TBM Avenger off Tulagi (CVE-72), piloted by Lieutenant (j.g.) Donald Davis, sighted a submarine on the surface. From 4,000 feet, he dove on the contact and dropped a depth bomb that exploded alongside the conning tower as the submarine was crash-diving. Circling back for another pass, Davis dropped a Mark 24 Fido acoustic homing torpedo that exploded against the submarine’s hull. That was the end of I-44, one of the Tatara Group of Kaiten submarines that had deployed from Japan on 28 March. All 130 crewmen and four Kaiten pilots were lost.

30 April

Terror (CM-5). Throughout the Okinawa operation, the minelayer Terror served as flagship and tender for the Mine Flotilla (Rear Admiral Alexander Sharp) at Kerama Retto. (The 5,900-ton Terror was the only U.S. ship built specifically for minelaying during World War II—other U.S. minelayers were converted destroyers.) During April, Terror’s crew went to general quarters 93 times. In the pre-dawn hours of 1 May, a lone kamikaze found its way through the smoke screen and caught Terror at anchor. Coming in from the starboard quarter so fast, only one gun on Terror was able to open fire before the plane crashed into the communications platform and one of two bombs exploded. The other bomb penetrated the main deck before exploding and the plane’s engine crashed into the wardroom. The large fire was under control quickly, but casualties were high: 48 dead and 123 wounded. Terror’s damage was extensive enough that she had to return to the States.

1 May

Kaiten submarine I-47 (of the Tembu Group) reported that it attacked a convoy, firing four conventional torpedoes from 4,300 yards and hearing three explosions. At 0900 on 2 May, I-47 sighted a 10,000-ton tanker with two escorting destroyers heading toward Okinawa. At 1100, the submarine launched Kaiten No. 1 and Kaiten No. 4, and reported two heavy explosions. I-47 sonar then detected two Fletcher-class destroyers and she launched Kaiten No. 2, which was followed by a heavy explosion. I-47 escaped the area, but no ships were hit and the explosions were most likely the Kaiten self-destructing. On 7 May, I-47 launched another Kaiten at a British Leander-class cruiser, but the remaining to Kaiten couldn’t be launched dueto malfunctions, so the submarine was ordered to return to port. None of her targets was hit. (Actually, I can’t find what the targets really were).

H-Gram 046 will continue with Kikusui No. 5 and beyond.

Sources include: NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) for U.S. ships and combinedfleet.com for Japanese ships; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1960); Too Close for Comfort, by Dale P. Harper (Bloomington, IN: Trafford Publishing, 2001); Silent Victory, by Clay Blair (Philadephia: J. B. Lippencott, 1975); Ghost of War: The Sinking of the Awa Maru and Japanese-American Relations, 1945–1995, by Roger Dingman (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997); Kamikaze: To Die for the Emperor, by Peter C. Smith (Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Aviation, 2014).