H-067-1: The Dancing Mouse: USS Edsall's Last Stand, 1 March 1942

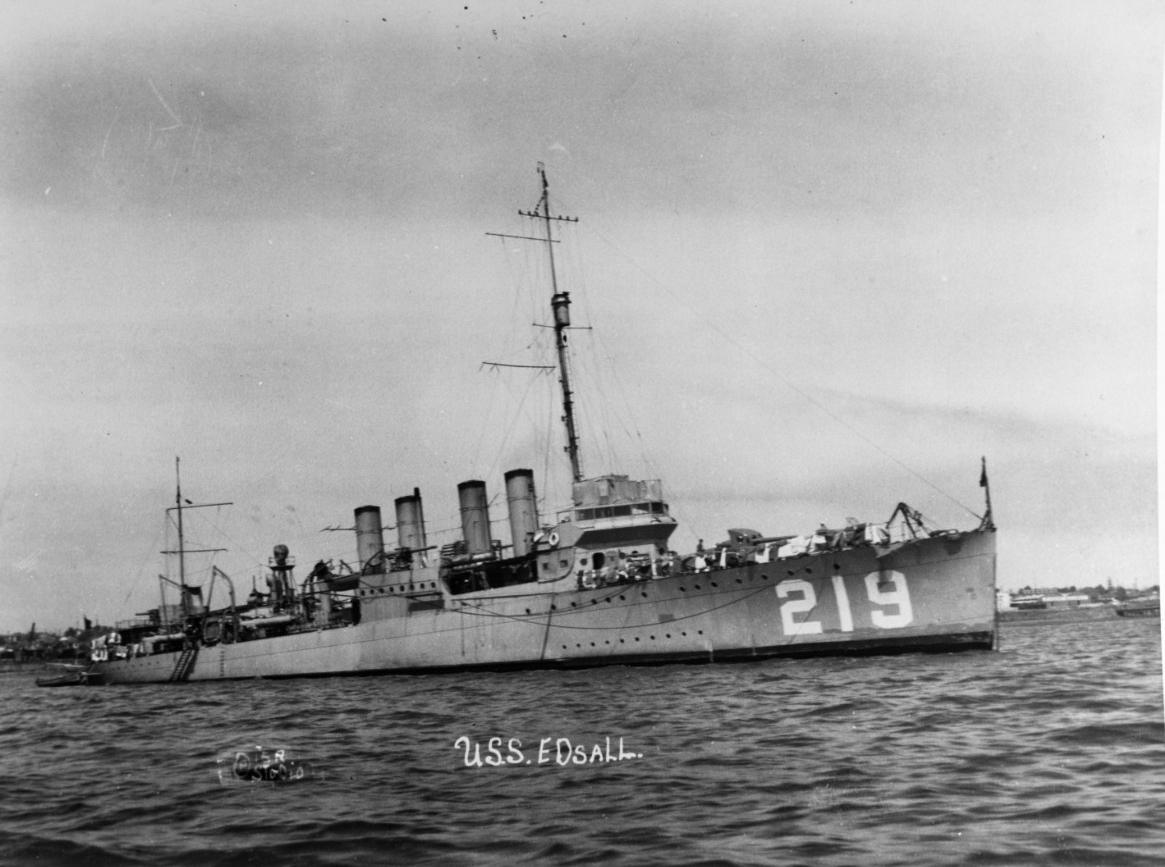

USS Edsall (DD-219) was one of 156 Clemson-class “flush deck” (or “four-piper”) destroyers authorized in 1917 and designed as battle fleet escorts to counter the German torpedo boat threat in World War I. It was the largest shipbuilding program in U.S. Navy history until the Fletcher-class destroyers in World War II. However, none of the Clemson-class destroyers were completed in time to participate in the war for which they were built. Edsall was laid down in September 1919 and commissioned on 26 November 1920.

Edsall was named after Seaman Norman Eckley Edsall, of the protected cruiser Philadelphia (C-4), who was killed in an ambush by Samoan warriors on 1 April 1899 while attempting to carry badly wounded Lieutenant Philip Van Horne Lansdale to safety. Ensign John R. Monaghan refused to leave Lansdale, and both were killed by pursuing Samoan natives. Edsall, Lansdale and Monaghan would have multiple ships named in their honor. (I will cover the Battle of Vailele, Samoa, in the third installment of “Battles You’ve Never Heard Of” later this spring.)

Edsall was 1,190 tons and 314 feet in length. She had two geared turbines with twin shafts and screws, capable of a very respectable 35 knots. She was armed with four single 4-inch/50 -caliber guns (one forward, one amidships starboard, one amidships port, and one aft). She had one 3-inch/23-caliber anti-aircraft gun. She had four triple-tube 21-inch torpedo mounts (two mounts per side) with 12 Mark 8 torpedoes (no reloads). Due to experience countering German U-boats during the war, the design was modified during construction to include two depth charge tracks on the stern, and a Y-gun depth charge projector forward of the after deck house, but she was still optimized to defend battleships. Her anti-aircraft armament would be increased with the addition of .50-caliber and .30-caliber machine guns over time. Her armament in 1941 was essentially the same as in 1920.

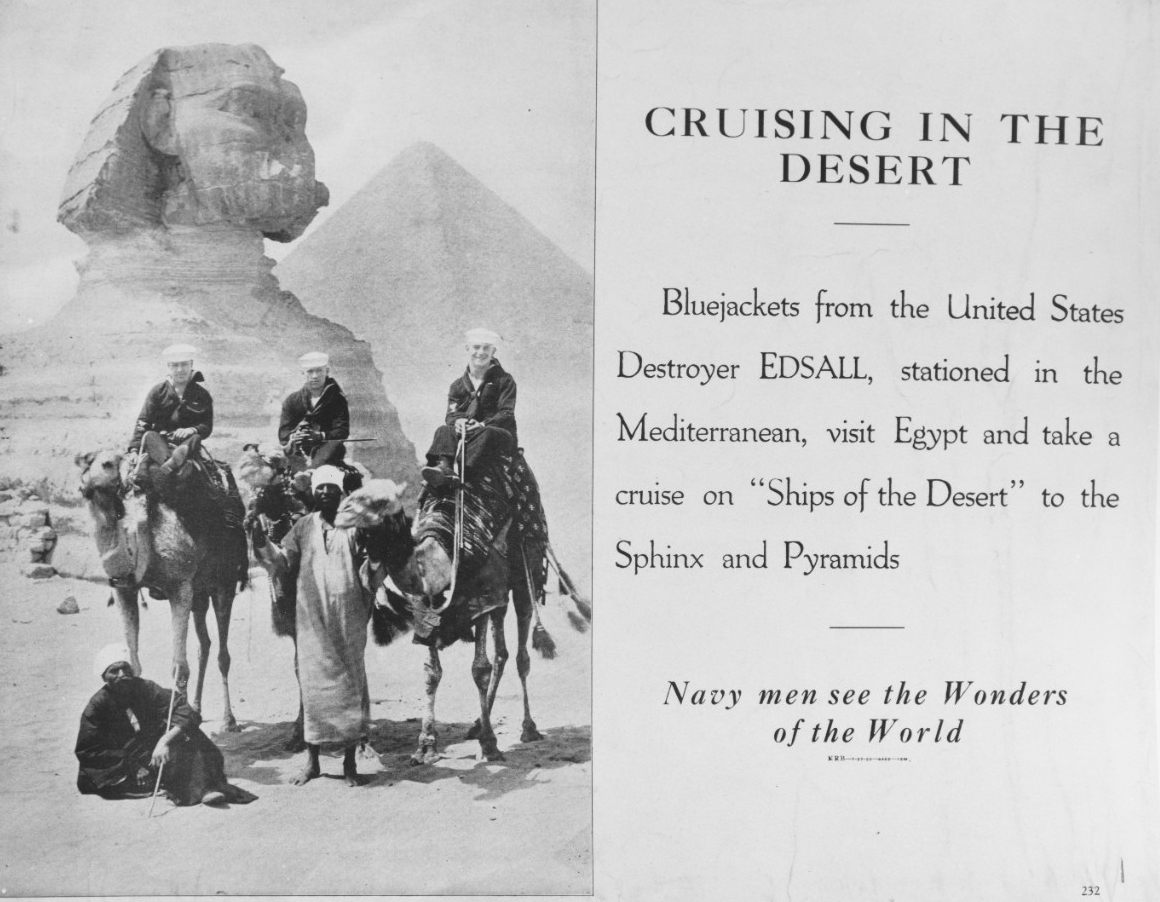

Despite missing the Great War, Edsall had an eventful early career. She deployed to the Mediterranean and the Black Sea in 1922 just as the civil war between the Communists and White Russians raged. During this deployment, war broke out between Greece and Turkey as the Turks expelled the Anatolian Greeks from the west coast of Turkey (where they had lived since before Homer’s times). In September 1922, Edsall evacuated 607 Greek refugees to Salonika, Greece, after they were evicted from Izmir, Turkey. Edsall acted as flagship for U.S. Navy forces protecting American lives and property on the coast of Turkey and evacuating additional Greek refugees. During the deployment, Edsall conducted show-the-flag port visits to Turkey, Bulgaria, Russia, Greece, Egypt, Palestine Mandate, Syria, Tunisia, Dalmatia, and Italy, before arriving in Boston for overhaul in July 1924.

In January 1925, Edsall departed the east coast of the United States for service in the Asiatic Fleet, arriving in Shanghai in June 1925. Edsall remained in the Asiatic Fleet for the remainder of her career. In late 1941, Edsall was one of 13 destroyers assigned to the fleet, all aged Clemson-class. Along with the heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), and elderly light cruiser Marblehead (CL-12), these 13 destroyers represented the surface combatant capability of the U.S. Navy in the Far East on the eve of war with Japan.

Lieutenant Joshua James Nix assumed command of Edsall on 13 October 1941, having first been assigned as the executive officer on the ship in October 1940. Lieutenant Nix was a 1930 U.S. Naval Academy graduate, 304th in a class of 405. His academy nickname was “Nickth” on account of his lisp. He was married the same day that he graduated and would have two sons (Walter was USNA '54). The Class of 1930 would lose 42 members during the war.

Ensign Nix completed his required sea duty on battleship New York (BB-34) before heading to Naval Air Station Pensacola for flight training. However, he did not get his wings. In May 1932, he was assigned to Clemson-class destroyer Fox (DD-234). In December 1933, he was assigned to the even older Wickes-class destroyer USS Lea (DD-118). In 1935, he reported to the elderly light cruiser Omaha (CL-4), before becoming an ordnance instructor at the Naval Academy in 1937. Promoted to lieutenant in June 1938, he was assigned the next year to the Asiatic Fleet destroyer tender, Black Hawk (AD-9). Although his career to that point had not been especially remarkable, he was believed to be the youngest destroyer skipper at the time when he assumed command of Edsall.

As the threat of war with Japan increased in 1941, Commander in Chief, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas C. Hart (USNA ’97) ordered all dependents back to the States. This met with some defiance by spouses, which Hart quelled by threatening to restrict all officers to their ships indefinitely. This would be the last time that Lieutenant Nix would see his family.

On 25 November 1941, Admiral Hart issued his “Defensive Deployment Order,” two days before the “War Warning” message from Washington. Hart’s order directed the fleet’s surface ships to depart the Philippines for locations further south (and out of Japanese land-based aircraft range). The order directed Destroyer Division Five Seven (DESDIV 57) to proceed south to Balikpapan, Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). DESDIV 57 included Edsall, Whipple (DD-217), John D. Edwards (DD-216), and Alden (DD-211). The executive officer of Alden was Lieutenant Ernest Evans (USNA ’31).

Although not stated in the order, Hart had already reached agreement with his British counterpart in Singapore that upon the outbreak of hostilities, DESDIV 57 would proceed to Singapore to provide enhanced anti-submarine protection for the arrival of Force Z, the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse.

Hart’s actions were guided by extensive intelligence that war in the Far East was imminent, much of it derived from the radio intercept site (Fleet Radio Unit - Station Cast). This station was moved from Shanghai, China, to Cavite, Philippines, near Manila, in early 1941 (before being moved to a tunnel on the fortress island of Corregidor in Manila Bay as the Japanese approached). In addition, Admiral Hart was receiving intelligence derived from decrypted Japanese diplomatic communications (the Purple code), that Admiral Husband Kimmel in Hawaii was not.

The devastating Japanese air attacks on the Philippines on 8 December (Philippines time – 7 December in Hawaii and Washington) and the following days effectively eliminated any air cover for U.S. naval forces operating in the Far East. For the remainder of the campaign, Japanese aircraft would have virtually uncontested control of the skies across the entire region.

On 8 December, DESDIV 57 was transiting from Balikpapan, Borneo, to Batavia (now Jakarta) when they were re-routed to Singapore in accord with the previous U.S.-British agreement (which actually had not been coordinated with Washington). Upon arrival in Singapore, DESDIV 57 took on a British liaison officer and four other Royal Navy sailors. However, Force Z had already departed in an attempt to disrupt the Japanese landings ongoing on the east coast of British Malaya.

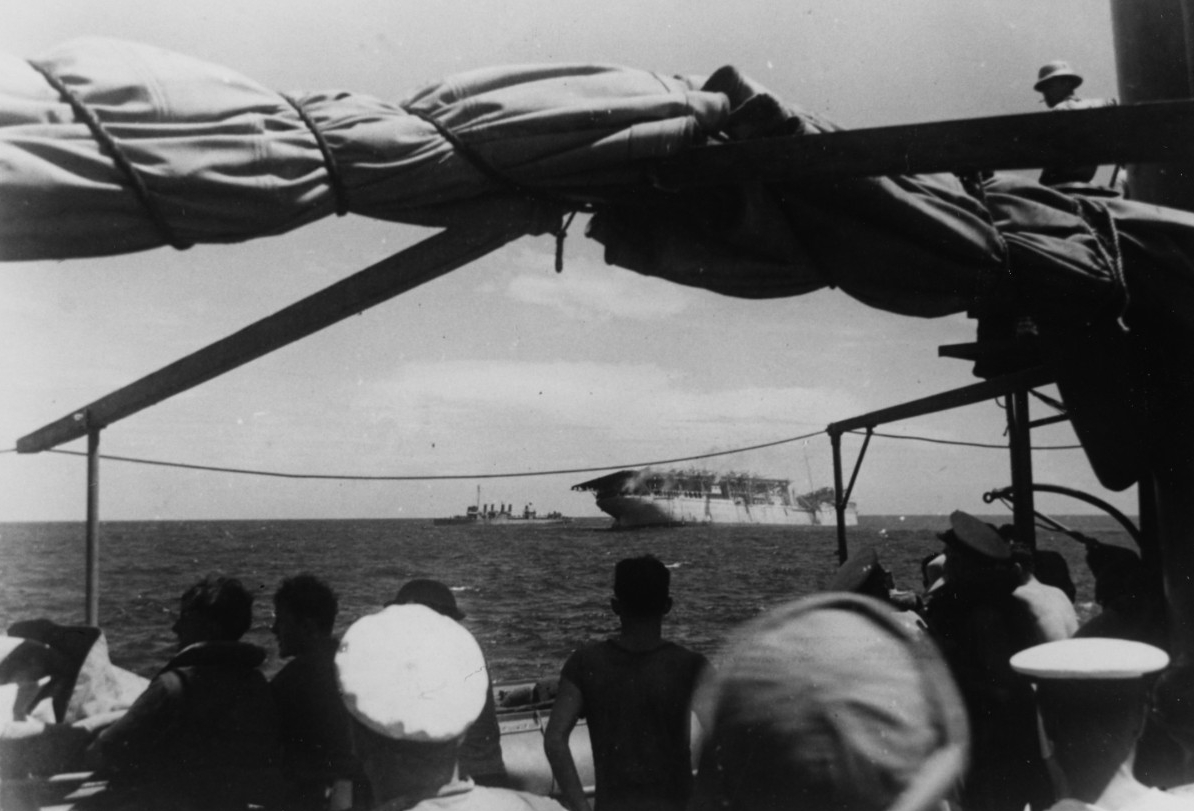

Loss of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, 10 December 1941. Photograph taken from a Japanese aircraft, with Prince of Wales at far left and Repulse beyond her. A Royal Navy destroyer, either Express or Electra, is maneuvering in the foreground. This photograph was likely taken after the first torpedo attack, during which Prince of Wales sustained heavy torpedo damage (80-G-413520).

Before DESDIV 57 could rendezvous with Force Z, both Prince of Wales (which had survived the encounter with German battleship Bismarck earlier in 1941 that sank battlecruiser HMS Hood) and Repulse were sunk by Japanese land-based Navy torpedo bombers. In many ways, this was a bigger shock than Pearl Harbor in that the new (commissioned January 1941) and modern Prince of Wales was the first battleship in history to be sunk by aircraft at sea in wartime conditions.

DESDIV 57 encountered Force Z’s few escorts heading the opposite direction with survivors of the two British capital ships, but DESDIV 57 proceeded to the battle area anyway to search for more survivors, but found none. While returning to Singapore, Edsall intercepted and captured a Japanese fishing trawler towing four small boats. Edsall escorted the trawler (Kofuku Maru in some accounts, Shofu Fu Maru in others) to Singapore.[1]

On 14 December 1941, DESDIV 57 departed Singapore for Batavia. Over the next month, Edsall escorted convoys between Australia and Java as increasing numbers of Japanese submarines arrived in the area, including at least two large mine-laying submarines (the Japanese had four such submarines).

On 20 January 1942, Edsall and Alden were escorting oiler Trinity (AO-13) to Darwin, Australia. At 0526, Trinity was narrowly missed by a torpedo fired by Japanese submarine I-123, about 40 miles west of Darwin. Japanese records indicate one torpedo fired, but Trinity lookouts reported three, although the sub only had two torpedo tubes. Edsall and Alden commenced the search for the submarine, with Alden gaining brief sonar contact and dropping several depth charges with inconclusive results.

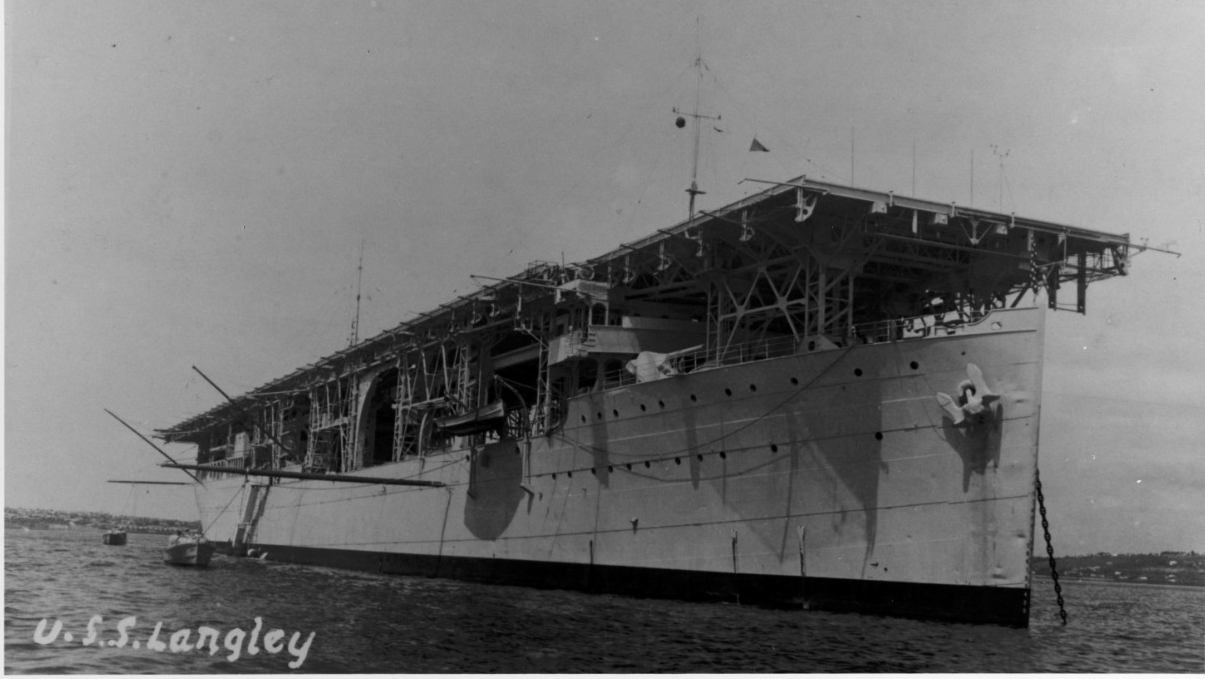

As Edsall and Alden escorted Trinity into the port of Darwin, three Australian corvettes were dispatched from Darwin to pursue the contact. At 1335, I-123’s sister mine-laying submarine, I-124, fired a torpedo at HMAS Deloraine, missing astern by 10 feet due to Deloraine’s evasive action. At 1338, Deloraine gained ASDIC (Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee) contact on the sub and dropped six depth charges. Ten minutes later, Deloraine made a second depth-charge attack, causing the submarine to briefly broach the surface. A well-aimed depth charge from Deloraine’s port thrower hit 10 feet from the submarine’s periscope as it went back under. Shortly thereafter, a bomb from an OS2U Kingfisher floatplane off seaplane tender Langley (AV-3, formerly the first U.S. aircraft carrier, CV-1) detonated about the same distance from the periscope. Oil and debris came to the surface as the target became stationary in 150 feet of water. Deloraine continued dropping depth charges until all were expended.

Commencing at 1710, HMAS Lithgow made seven attacks on the contact, expending all 40 depth charges. At 1748, HMAS Katoomba joined in with more depth charges, and even tried to hook the submarine with a grapnel. In the meantime, Edsall and Alden were ordered back to sea to continue the prosecution. At 1859, Edsall dropped five depth charges on a submarine contact, and at 1955, Alden conducted another depth-charge attack.

Edsall and Alden would be given partial credit for assisting in the sinking of I-124, but the submarine was probably done for well before the U.S. ships arrived. The Australians claimed three submarines sunk, but it was actually multiple attacks on the same submarine.

On 26 February, 16 U.S. divers from submarine tender Holland (AS-3) arrived aboard boom vessel HMAS Kookaburra. The fourth and fifth dives located a large Japanese submarine, mostly intact, with perforations around the sail and a blown hatch. There were no survivors from the approximately 80-man crew.

Some accounts claim incorrectly that the sinking of I-124 was the first blood drawn on the Japanese submarine force. I-124 was the first sunk by the Australians, but it was the fourth, with the first being I-70, sunk by Enterprise (CV-6) dive-bombers off Oahu on 9 December 1941. Other accounts also incorrectly claim that codebooks and other documents were recovered off I-124, which aided subsequent Allied code-breaking efforts. However, no divers ever penetrated I-124’s hull.[2]

On 23 January, Edsall attacked another submarine contact in the shallow water of the Howard Channel near Darwin and a depth charge prematurely detonated under her stern in only 48 feet of water. The force of the explosion damaged one shaft and screw, and her rudder, rendering her incapable of maximum speed and impeding her maneuverability. She was deemed unfit for combat duty, relegated to escort duty, which prevented her participation in other battles, including the disastrous Battle of the Java Sea in late February.

On 3 February, Edsall was ordered to operate out of Tjilatjap, the largest port on the south coast of Java, along with her sister ship Whipple (DD-217). Whipple had previously collided with the Dutch light cruiser De Ruyter and had been fitted with a temporary “soft bow,” rendering her also unfit for combat duty. For the next weeks, Edsall, Whipple, and the elderly (commissioned 1920) gunboat Asheville (PG-21) escorted ships in and out of Tjilatjap.

On 17 February, four carriers of the Kido Butai (Japanese carrier strike force) arrived at Staring Bay, Celebes Island, Dutch East Indies, under the command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who had led the Pearl Harbor strike force. The same night, carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu, heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma, and escorts departed Staring Bay for a high-speed transit toward Australia.

On the morning of 19 February, the Kido Butai launched a devastating surprise strike on the Australian port of Darwin with 81 Kate torpedo bombers (configured as high-altitude horizontal bombers), 72 Val dive bombers, and 36 Zeke fighters (more commonly known as “Zero”) led by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who had led the strike on Pearl Harbor. The carrier attack was followed up by 54 Nell and Betty twin-engine land-based bombers from Kendari, Celebes.

When the attack on Darwin was over, 11 Allied ships were sunk, including destroyer Peary (DD-226), which went down with her guns blazing to the last (her story is also one of incredible valor), and 13 other ships were damaged, including seaplane tender William B. Preston (AVD-7). The strike missed catching heavy cruiser Houston in port by a matter of hours. Thirty Allied aircraft were destroyed and the PBY Catalina flown by future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Thomas Moorer (USNA ’33) was shot down.

The Kido Butai returned to Staring Bay and was joined by the battleship force under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo, which included Battleship Division 3 (Hiei, Kirishima, Kongo, and Haruna) and Cruiser Division 4 (heavy cruisers Atago, Maya, and Takao). Hiei and Kirishima detached from Kondo’s force to reprise their Pearl Harbor role as escorts for the Kido Butai. The two groups then proceeded into the Indian Ocean, operating independently, with intent to support the main Japanese invasion of Java (scheduled for 25 February) by blocking the escape route from the Dutch East Indies to Australia. Nagumo’s force consisted of the four carriers, fast battleships Hiei and Kirishima, the two heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 8 (Chikuma and Tone), the light cruiser Abukuma, and eight destroyers, along with six tankers.

On 26 February, Edsall and Whipple departed Tjilatjap to rendezvous and escort seaplane tender Langley, which was carrying a cargo of 32 P-40E Warhawk fighters, along with 33 U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) pilots and 12 crew chiefs of the 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional). As the Japanese had already shot down or destroyed almost every Allied aircraft in the Dutch East Indies, achieving total dominance of the air, Langley’s mission was one of great desperation. The commander of DESDIV 57, Commander Edwin M. Crouch (USNA ’21) was embarked on Whipple, which was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Eugene S. Karpe (USNA ’26).

Tjilatjap was the only port on the south coast of Java that could take Langley. However, Tjilatjap had no airfield, so getting the P-40s out of the port was going to be a challenge in itself. Worse yet, through a tragedy of multiple errors and garbled communications, Langley would be making her final approach to Tjilatjap in broad daylight with no air cover, defended only by her own inadequate anti-aircraft weaponry and the equally inadequate weapons of Edsall and Whipple.

On 27 February, Langley was attacked by 16 Mitsubishi G4M Betty twin-engine bombers, escorted by 15 A6M Zero fighters, launching from the just-captured Den Pasar Airfield on Bali. The bombers conducted their attacks from above any effective anti-aircraft fire from Langley, Whipple, or Edsall. As the first nine aircraft commenced their attack in a “V” formation, the skipper of Langley, Commander Robert P. McConnell (who had joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in 1920), skillfully maneuvered the ship to avoid the rain of bombs. However, seven of the bombs were near misses, two within 100 feet, parting seams in the old ship’s hull. Langley was already in serious trouble as the source of flooding could not be immediately located.

As the Japanese bombers commenced a second attack, McConnell again maneuvered to avoid, but this time the Japanese withheld their bombs, watching (and learning) from McConnell’s actions. As a result, during the third attack, McConnell’s maneuver was about a second too late and Langley was hit by five bombs and three near misses in what may have been the most accurate ship attack by horizontal bombing in the entire war.[3]

The bomb hits were devastating, despite causing amazingly few casualties. Already top-heavy with the load of Army fighters, Langley quickly took on a serious list as the planes all caught fire. The shock throughout the ship broke fire mains and caused other damage that severely hampered any damage control efforts. Wallowing dead in the water in broad daylight, sinking and in danger of capsizing due to the list, with every prospect of additional air attacks, and no prospect of a tug, Commander McConnell gave the order to abandon ship.

Edsall rescued 177 men from Langley, while Whipple picked up 308. Despite the severe damage, Langley’s casualties were six killed (or seven, or eight, depending on account) and five missing. However, after being abandoned, Langley refused to sink. At 1428, at the request of Commander McConnell, Whipple fired nine 4-inch rounds into Langley to hasten the sinking, with no apparent effect. At 1432, Whipple then fired one of her few torpedoes into Langley’s starboard quarter, with intent to detonate the after magazine. Unlike the Navy’s newer torpedoes, Whipple’s Mark 8 actually exploded on contact, but the magazine did not explode and still Langley refused to sink. Whipple then fired another torpedo into Langley’s port side, which set off a massive fire, but otherwise only succeeded in partially correcting Langley’s list.

Increasingly concerned that the essentially defenseless destroyers, overloaded with survivors, were at great risk of follow-on air attacks (and with Langley’s precious cargo of fighters destroyed by fire), McConnell and Crouch agreed to leave Langley behind and reverse course away from Tjilatjap. At 1446, Whipple and Edsall departed the scene, each crammed with survivors. This sequence of events would lead to later recriminations that not enough was done to save Langley. Recommendations for an investigation were subsequently quashed by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King, who rejected the accusation that McConnell had not upheld the best traditions of the naval service.

As the attack on Langley commenced and the fight to save her continued, the Allied naval forces were engaged in a major sea battle north of Java, which would result in a disastrous lopsided defeat. The Allied commander of the force, Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, would go down with his flagship, the Dutch light cruiser De Ruyter, lost along with Dutch light cruiser Java and destroyer Kortenaer. British destroyers HMS Electra and HMS Jupiter were also sunk, while heavy cruiser HMS Exeter was badly damaged. The four U.S. destroyers involved (including Alden) were ordered to disengage, after being ordered to wastefully fire their torpedoes at long range, and therefore survived the battle. Ernest Evans on Alden would mull over the sting of this defeat, vowing later that he would never run from a fight.

In what became known as the Battle of the Java Sea (the largest surface naval engagement since Jutland in 1916), heavy cruiser Houston and Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth survived the rather inconclusive long-range daylight gunnery duel with two Japanese heavy cruisers, as well as the devastating Japanese night “Long Lance” torpedo attack that sank De Ruyter and Java. At a cost of over 2,300 Allied sailors, Doorman’s force delayed the Japanese invasion of Java by one day. The Japanese lost about 36 sailors and suffered damage to one destroyer and a transport. Within the next two days, Houston, Perth, Exeter, and other U.S., British, and Dutch destroyers would be on the bottom.

On 28 February, Whipple and Edsall rendezvoused with oiler USS Pecos (AO-6) at Flying Fish Cove at Christmas Island, 250 miles southwest of Tjilatjap, with intent to transfer Langley’s survivors to Pecos. Under the command of Commander Elmer P. Abernethy (USNA ‘21), Pecos had departed Tjilatjap carrying a number of wounded men from Houston, Marblehead, and destroyer Stewart (DD-214) as a result of the earlier Battle of the Flores Sea and other air attacks. Before the transfer could get underway, three Japanese land-based bombers arrived overhead. Although the bombers’ actual target was the phosphate mining facility on Christmas Island (which they duly bombed), the ships did not know that and hastened back to sea to the safety of a rain squall. Knowing the bombers would have reported their presence, the three ships then proceeded south in increasingly heavy seas.

In the pre-dawn hours of 1 March, the seas abated enough that the large Pecos could create enough of an artificial lee for the boat transfer of Langley survivors to take place. All survivors were transferred with the exception of 31 USAAF pilots aboard Edsall (two of the 33 pilots were wounded in the attack on Langley and were transferred to Pecos).

Edsall received orders from Allied command on Java to take the pilots to Tjilatlap, to marry up with 27 crated P-40 fighters due in to Tjilatjap on the Sea Witch (which led a charmed life). Given the ongoing complete collapse of the Allied effort to defend Java, one historian characterized this order as “one of the most monumentally stupid decisions of the war.” That may be an exaggeration (with plenty of competition), but Edsall commenced to carry out her orders. However, by 0830 on 1 March, the senior U.S. naval officer in the Allied Command, Rear Admiral William A. Glassford (USNA ’06), issued orders for all U.S. naval forces to evacuate Java and rendezvous at a point to the south (a point that was compromised to the Japanese). As a result of the order, Edsall reversed course to the south.

In the meantime, Whipple was ordered to proceed to the Cocos Islands, southwest of Christmas Island, to escort the Norwegian tanker Belita (later sunk by a Japanese submarine). Pecos was ordered to proceed to Australia with the Langley survivors. Including her own crew of 15 officers and 227 enlisted, Pecos had about 700 personnel embarked.

Unbeknownst to the three U.S. ships, the Kido Butai had arrived in the vicinity of Christmas Island. At 0700, the heavy cruisers Tone and Chikuma each launched one E13A1 Jake floatplane to search the area, locating merchant ships, but no warships, as Pecos and the two destroyers had cleared out the day before.

Chikuma’s Jake sighted the Dutch armed motor vessel Modjokerto, which was escaping from Tjilatjap, and vectored destroyers Isokaze and Shiranuhi to intercept. Admiral Nagumo apparently decided his ships needed some gunnery practice. Some accounts state that Chikuma was unable to sink Modjokerto with gunfire because her armor-piercing shells passed clean through, all as sailors on Akagi lined the rails to watch the spectacle. Chikuma reportedly resorted to firing a torpedo, which did the job, and which earned Chikuma’s skipper a rebuke for wasting a torpedo on a cargo ship. However, the war diary of Destroyer Division One gives credit to Isokaze for sinking Modjokerto. (This is just one of many discrepancies in accounts of these actions, which make it virtually impossible to state definitively what really happened.) Regardless, about 30 survivors were fished out of the water by the Japanese. By 1400, the two cruiser float planes had returned to their mother ships.

At 1000, a single aircraft with non-retractable landing gear was sighted by lookouts on Pecos. The presence of one single-engine aircraft of that type meant that Japanese carriers were in range, indicating that previous fragmentary reports of Japanese carriers operating south of Java were true. With his large slow oiler packed with survivors, Pecos’ skipper Commander Abernethy knew his ship was in deep trouble, and the Japanese carrier aircraft would have all day to attack his ship. The Japanese Val dive-bomber reported the location of Pecos and the carriers began launching aircraft.

At about noon, the attack Commander Abernethy anticipated materialized in the form of six (or nine, depending on account) Kaga Val dive-bombers coming out of the sun one at a time, as if expecting easy pickings on the fat oiler. With her two 5-inch guns, 3-inch guns, and other machine guns, Pecos put up a ferocious defense that threw the Japanese off. Japanese accounts noted that the captain of Pecos was “skilled and superbly avoided our bombs.” Only one bomb hit Pecos, killing most of the gunners at the starboard 3-inch gun mount, which was immediately remanned by other Pecos crewmen and kept firing. Near misses did cause significant damage, resulting in an eight-degree port list. Four of the Vals were hit, a couple badly, although all made it back to their carriers, claiming to have sunk the Pecos.

Following the first attack, the list was corrected, fires brought under control and the radios fixed. An hour later, six more (or nine more) Soryu Vals attacked, again one at a time. Once again, Pecos put up an incredible volume of fire with everything she had, 5-inch and 3-inch guns, .50- and .30-caliber machine guns, Browning automatic rifles, .45-caliber pistols, and even thrown potatoes. Despite intense anti-aircraft fire that damaged most of the Vals and caused several to drop their bombs early, the ship’s impaired mobility from previous damage aided the dive-bombers in obtaining four direct hits and damaging near misses, killing many sailors on Pecos.

Although sailors remanned the guns as fast as gunners were killed, an unauthorized shout of “abandon ship” resulted in about two boats, several life rafts, and about 100 personnel going over the side. One of the boats came down on the spinning starboard propeller, out of the water due to the resumed even greater list, which ripped the full boat and people in it to shreds. None of those who prematurely abandoned ship survived.

Although badly damaged, once again the crew of Pecos put out the fires, corrected much of the list, and brought the radios online again. At about 1445, Pecos’ number was up as 18 dive-bombers from Akagi and Hiryu arrived overhead. So many of the gunners on Pecos had been killed or wounded that the guns were mostly manned by untrained volunteers. Hiryu’s dive-bombers attacked first, this time all at once. Untrained or not, the volume of anti-aircraft fire put up by Pecos’ gunners unnerved what were arguably the best dive-bomber pilots in the Japanese navy (if not the world) and all bombs missed.

Then it was Akagi’s nine dive-bombers’ turn, and like Hiryu’s planes, they came down in a single swarm, and all bombs missed. However, the eighth bomb was a very damaging near miss, resulting in uncontrollable flooding. At this point, Abernethy knew his ship was doomed, and at 1530 he finally gave the order to abandon ship, as he “calmly directed abandoning operations under a hail of fire from enemy fliers who kept circling the ship and strafing helpless survivors clinging to life rafts and floating debris,” according to his Navy Cross citation.

Three Vals strafed survivors in the water. One of the Vals still had its bomb, but was hit and driven off by fire from a .50-caliber machine gun manned by Pecos’ executive officer, Lieutenant Lawrence McPeak (USNA ’24), who was awarded a posthumous Silver Star for his action. The plane dropped its bomb harmlessly 300 yards away.

As the attack was ongoing, Pecos radioed distress signals and position reports, with the last transmission going out at 1538. Pecos sank at about 1548, and her crew (minus those killed in the bombings) went into the water, as the survivors of Langley went into the water a second time. Whipple definitely received the distress signals and changed course to come to the aid of Pecos despite her inadequate anti-aircraft weaponry. Lieutenant Commander Karpe was aware of the attacks as they were ongoing, but correctly decided to time Whipple’s arrival for after sunset, otherwise his ship would most likely meet the same fate.

Whether Edsall heard the distress calls is unknown, although she probably did. The troopship Mount Vernon (AP-22), about 100 miles away, heard the calls. As Pecos’ crew and other survivors of Langley were drifting in the water in the hours prior to sunset, they could clearly hear the sounds of a major sea battle. At this point, the Kido Butai was between Edsall and the Pecos survivors.

Whipple began picking up survivors of Pecos and Langley at about 1915, eventually bringing 232 on board, including Commander Abernethy of Pecos and Commander McConnell of Langley, as well as the two wounded Army pilots transferred from Edsall. The rescue effort was interrupted about 2148 by sonar contact on a submarine, probably valid as survivors reported seeing a conning tower. Whipple dropped two depth charges, which never does swimmers in the water any good. Whipple attempted to resume rescues at 2152, but was interrupted again by a submarine contact, this time dropping four depth charges. At this point, the senior officers conferred and reluctantly agreed that it was too dangerous for Whipple to remain.

At about 2200, Whipple departed the area, leaving about 500 survivors still in the water. Tragically, a subsequent search the next day by a flying boat failed to find any survivors. None of those left behind by Whipple, many in plain sight, survived. Lieutenant Commander Karpe would be criticized for not rescuing more survivors, but the decision was made and jointly concurred with by the more senior officers, Crouch, McConnell, and Abernethy.[4]

Earlier on 1 March, at 1550, a plane from Akagi, possibly returning from bombing Pecos, reported sighting a light cruiser of "Marblehead type" about 16 miles behind the Japanese carriers, and reportedly pursuing the Kido Butai. The Japanese had a bit of a fixation with Marblehead, which had survived severe damage from two direct hits and a near miss from Japanese bombs on 4 February. The Japanese reported sighting her multiple times after she was long gone from the region. As of 1 March, Marblehead was preparing to depart Trincomalee, Ceylon, on her epic journey under her own power (with no rudder) back to the United States, in one of the most incredible damage-control feats of all time.

The contact was obviously not the Marblehead (or any of her sisters, which were nowhere near the Far East). The contact was, in fact, the Edsall. As both Marblehead and Edsall had four stacks, it was hardly the most outrageous misidentification of the war. Edsall was definitely not in pursuit of the Kido Butai; more likely, she was trying to reach Pecos’ last reported position, which was about 24–35 miles from where Edsall was spotted, about 225 miles south southeast of Christmas Island.

Vice Admiral Nagumo was reportedly incensed that an enemy cruiser could have gotten to within 16 miles of his forces without being previously sighted. At 1552, Nagumo ordered Battleship Division Three and Cruiser Division Eight to intercept the “cruiser.” Rear Admiral Gunichi Mikawa (future victor in the Battle of Savo Island) assumed tactical command of the surface action, embarked in battleship Hiei, with Kirishima in trail. Rear Admiral Hiroaki Abe (CRUDIV 8, embarked in heavy cruiser Tone) assumed a secondary role. Chikuma initially took station to port of the battleship column with Tone to starboard.

At 1602, Chikuma sighted Edsall and commenced firing with her 8-inch main battery at extreme range of 21,000 yards at 1603. About five minutes later, Rear Admiral Abe ordered his cruisers to charge.

With her speed and maneuverability impaired by the damage from the previous premature depth-charge detonation, Edsall had no chance of outrunning the Japanese cruisers or the battleships (which were converted battlecruisers, and so faster than other battleships, which is why they were the battleships of choice to escort the carriers). Edsall’s vintage 4-inch guns were incapable of penetrating the armor of Japanese destroyers, much less heavy cruisers and battleships. Edsall’s torpedoes had shorter range than the numerous secondary armament guns on the Japanese battleships and cruisers. Although she had 12 torpedo tubes, Edsall only had nine torpedoes.

In short, Lieutenant Nix’s position was hopeless from the moment Edsall was sighted. As a last gesture of defiance, like the famous cartoon of the little mouse flipping the bird at a huge screaming eagle, Lieutenant Nix chose to make a fight of it. Inculcated in the Naval Academy “Don’t Give up the Ship” mentality, the thought of striking his colors or scuttling the ship without a fight probably did not cross his mind. If it did, he ignored it.

Edsall sent a contact report stating she had been surprised by two Japanese battleships. The Edsall’s radio may have been jammed by the Japanese (they had the capability). Regardless, no Allied ships or stations heard the report. The master of the Dutch merchant ship Siantar, about 99 miles away, reported receiving Edsall’s report, but only after he was rescued several days later after his ship had been sunk. It would not really have mattered. The only Allied warship near enough to come to Edsall’s aid was Whipple, and she would have met the same fate. Not even Houston could have stood up to the battleships, and she was already on the bottom of Sunda Strait. The sea battle that survivors of the sinking of Pecos reported hearing were Japanese guns firing on Edsall.

When the Japanese commenced firing, Edsall commenced laying a smoke screen that the Japanese described as skillfully laid. Edsall then commenced evasive maneuvers, constantly changing course and speed, from flank to zero and in between. Her radical and unpredictable maneuvers, interspersed with additional smoke screens, repeatedly thwarted Japanese aim, all the more remarkable given Edsall’s impaired maneuverability. Japanese reports expressed admiration for Edsall’s ship handling.

The battleships maneuvered to the east to cut off any avenue of escape for Edsall. At 1616, Hiei opened fire with her 14-inch main battery at a range of almost 27,900 yards, achieving a straddle, but little else. At 1619, Hiei commenced launching all five of her floatplanes to provide gunfire spotting, which would prove equally ineffective. It took almost 40 minutes for Tone to actually find Edsall in the smoke before she could open fire. As dozens and then hundreds of Japanese rounds missed their mark, the Japanese commanders became increasingly frustrated. About this time, the Japanese finally realized they were up against a destroyer and not a light cruiser.

At 1620, Rear Admiral Mikawa gave the order “all forces charge.” At 1639, Mikawa ordered all forces to flank speed. As the range closed, Edsall charged the Japanese, jinking and weaving, opening fire with her 4-inch guns. The rounds from Edsall’s guns fell short, but the Japanese were startled to see torpedoes from Edsall narrowly miss Chikuma.

By 1650, the Japanese cruisers and battleships had fired over 1,000 rounds of 14-inch and 8-inch shells, with no direct hits to show for it. Completely fed up, Vice Admiral Nagumo ordered the carriers to launch dive-bombers. At 1655, the surface ships checked fire. At 1657, the carriers commenced launching 26 Val dive-bombers. Kaga launched eight Vals, while Hiryu and Soryu launched nine each, all armed with a 550-pound bomb. Between 1657 and 1720, the dive bombers pounded Edsall. Lieutenant Nix still managed to avoid most of the bombs, but several direct hits and many near misses were more than the old ship could take.

With fires raging and the ship settling and losing way, Lieutenant Nix pointed the bow of Edsall at the Japanese surface ships in his last act of defiance. Japanese observers on Chikuma watched as an officer they believed to be the commanding officer supervised an orderly abandonment of the ship by the crew. The officer then returned to Edsall’s bridge, and was not seen again.

At 1718, with Edsall dead in the water, Kirishima opened fire with her 14-inch guns, switching to her secondary battery four minutes later. Chikuma opened fire on Edsall from the opposite side. Under the last barrage of gunfire, Edsall finally went down by the stern at 1731, leaving a large number of survivors in the water. In the course of the battle, the two Japanese heavy cruisers fired 844 8-inch rounds and 62 5-inch rounds. The two battleships fired 297 14-inch rounds and 132 6-inch rounds. Of the 1,335 rounds fired, one from Tone may have been a direct hit; however, even that is suspect, as it had no apparent effect.

Accounts of this battle, all derived from Japanese sources, sometimes many years after the fact, are contradictory in time and sequence of events. (I use the times from combinedfleet.com tabular record of movement [TROM] for Japanese ships.) Regardless of the times, it was approaching dusk when the carriers launched and light was fading as Edsall sank. This is consistent with Pecos survivors reporting that the distant gunfire occurred during a two-hour period before sunset. The fact that Whipple was able to rescue any Pecos/Langley survivors after sunset was probably due to the sacrifice of Edsall, which diverted the Kido Butai’s attention.

The abysmal gunnery performance was not because the Japanese were poorly trained or had bad equipment, although the excessive ranges for much of the engagement had something to do with it, allowing Lieutenant Nix enough time between the flashes of guns and impact to take evasive actions. Significant credit must go to Nix and his extraordinary ship handling. According to a Japanese observer, Edsall performed like a “Japanese dancing mouse” (a popular domesticated pet in Japan, also known as “waltzing mice” or “whirler” for its manic and bizarre movements). If it were not for the unpredictable speed and course changes, the Japanese would have put Edsall under a lot sooner.

A Japanese cameraman, probably on Tone, filmed about 90 seconds of Edsall, after she was abandoned and immobile, being literally blown out of the water by probably a 14-inch shell from Kirishima. A still taken from the film was used in Japanese propaganda, but misidentified as a British destroyer, “HMS Pope” (there was no such ship). Pope (DD-225) is an indistinguishable sister of Edsall and was sunk the same day in the Java Sea south of Borneo. However, the circumstances of the loss of Pope (equally heroic) were different than Edsall. The famous photo is definitely Edsall (see H-003-6).

Chikuma reported picking up a (Japanese for “handful”) of survivors of Edsall, believed to be about eight. Tone may have picked up one or two survivors, but that is uncertain. Many other survivors of Edsall’s 185-man crew were observed in the water, but were left behind, officially due to a “submarine alert.” (At that point in the war, some Japanese ships would rescue enemy survivors, but later in 1942, there was pretty much “no quarter” at sea, by both side.) The Edsall survivors were treated decently while aboard Chikuma.

The Kido Butai returned to Staring Bay, Celebes, on 11 March, at which point about 36 prisoners of war were turned over to the Japanese Special Naval Landing Force at Kendari, and then turned over to the Tokkeitai (Imperial Japanese Navy military police force).

Lieutenant Nix and his crew were subsequently listed as missing in action as of 1 March 1942, presumably due to enemy action. After the war, no Edsall crewmen were located in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, and the Navy Department declared the entire crew “presumed dead” on 25 November 1945, as of 1 March 1942. In keeping with U.S. Navy tradition for ships lost in battle, the name Edsall was quickly recycled. Commissioned in April 1943, destroyer escort USS Edsall (DE-129) was the lead ship of a class of 85 vessels, optimized for convoy escort and anti-submarine warfare.

During the war crimes trial convened in Java by the Allies after the end of the war, an eyewitness led Allied investigators to the Japanese execution grounds near Kendari II airfield, on Celebes Island, locating 34 decapitated bodies in two mass graves. Most of the bodies were Javanese, Chinese, and Dutch merchant sailors from the Modjokerto, sunk the same day as Edsall. However, five remains of a group of ten were identified as Edsall crewmen based on dog tags. The other five were unidentified but were probably USAAF pilots who had been aboard Edsall when she was sunk. A sixth Edsall crewman, also decapitated, was identified in a separate burial area. Based on his dog tag, this crewman was Fireman Second Class Loren Stanford Myers. Although not known until many years after the war, the Modjokerto and Edsall crewmen had been executed by beheading at Kendari II on 24 March 1942.

All the U.S. remains located at Kendari II were reburied at the U.S. Military Cemetery at Barrackpore, India, on 12 November 1946. They were subsequently disinterred and reburied on 20 December 1949 at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, St. Louis, Missouri, except for Fireman Myers, who was reburied at the National Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) on Oahu, Hawaii, at the request of his family.

Some accounts state Lieutenant Nix was posthumously promoted to lieutenant commander, but there is no documentary confirmation of this, although he would have been at the top of the lieutenant list by the end of the war. He was awarded a Legion of Merit while in missing-in-action status for his actions in command of Edsall prior to her loss. No ship was ever named in his honor.

Edsall was awarded two battle stars for her wartime service. However, because there were no living U.S. witnesses to Edsall’s last fight, there are no Medals of Honor, Navy Crosses or Presidential Unit Citations for what was one of the most gallant and valorous actions in the history of the U.S. Navy. Nevertheless, we have a duty to remember their courage in the face of overwhelming odds.

For more on the valor of the Asiatic Fleet, please see H-Gram 003.

Note: Normally I don’t specifically identify Naval Academy graduates in H-grams. My point in doing so here is that during the darkest days of World War II, the officers on ships were almost entirely Naval Academy graduates, who bought time and held the line, with extraordinary courage and great cost. With their lives, they brought great credit to the institution. Their sacrifice enabled a nation that was not ready for war to recover and persevere. The career enlisted Sailors, who endured years of low pay and hardship in the interwar years, were just as important in holding the line. The influx of massive numbers of reservists, volunteers and draftees after the war started played an absolutely critical role in the offensives that won the war.

____________

Notes

[1] Renamed motor vessel (MV) Krait, the trawler would serve as the mother ship for a daring commando raid on Singapore in September 1943 (Operation Jaywick) by Australia’s Z Special Unit, which sank or damaged seven Japanese merchant ships. Today, Krait is a museum ship in Australia.

[2] The saga of I-124’s wreck after the war is a story in itself, and one reason why I have a dim view of the salvage industry, but it is now protected by Australia as a war grave.

[3] The Japanese bombers were Navy, not Army, which accounts in part for their superior accuracy.

[4] Crouch would be a passenger on USS Indianapolis (CA-35) when she was torpedoed and sunk by Japanese submarine I-58 in July 1945 and was lost at sea. Karpe would be killed in 1952 as he was finishing his tour as a naval attaché to Romania when he was thrown from a train in a tunnel near Salzburg, Austria, possibly by members of a foreign intelligence service (presumably Soviet bloc).

Bibliography

Cox, Jeffrey R. Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2015.

Hoyt, Edwin P. The Lonely Ships: The Life and Death of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. New York, NY: Jove Books, 1976.

Kehn, Donald, Jr. A Blue Sea of Blood: Deciphering the Mysterious Fate of the USS Edsall. Minneapolis, MN: Zenith Press, 2008.

Kehn, Donald, Jr. In the Highest Degree Tragic: The Sacrifice of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet during World War II. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2017.

Messimer, Dwight. Pawns of War: The Loss of USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983.

Stille, Mark. Java Sea 1942: Japan’s Conquest of the Netherlands East Indies. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2019.

Winslow, Walter G. The Fleet the Gods Forgot: The Asiatic Fleet in World War II. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982.

Other NHHC Resources

Battles of Java Sea and Sunda Strait