Omaha II (CL-4)

1923–1945

Whereas the first Omaha was named for the river in Nebraska, the second ship of the name honored the city in Nebraska.

II

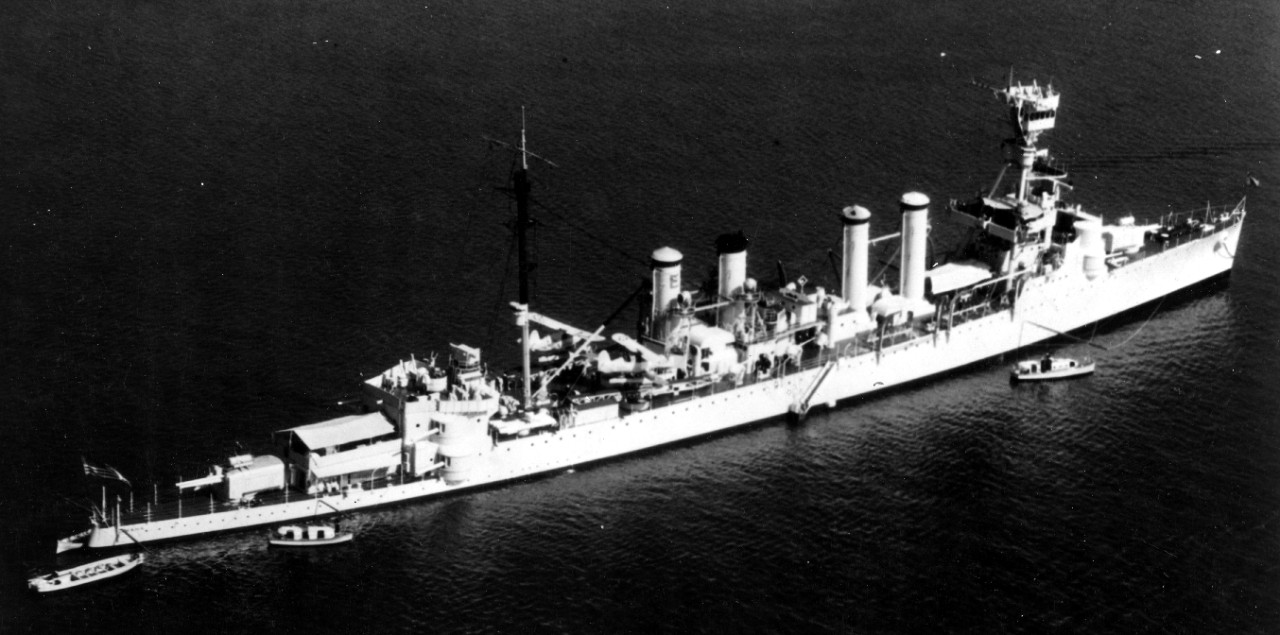

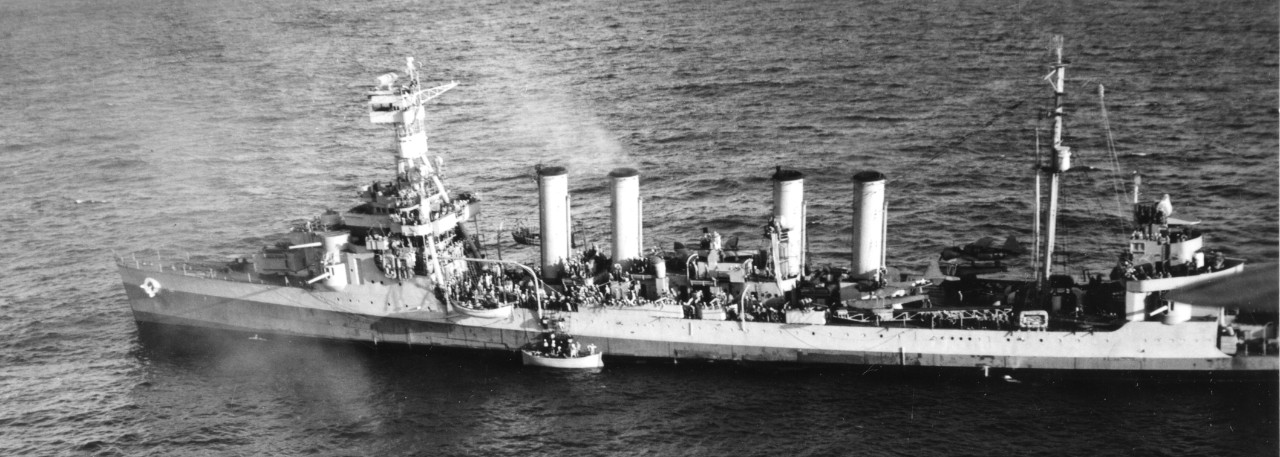

(CL-4: displacement 7,050; length 555'6"; beam 55'; draft 14'3"; speed 33.7 knots; complement 458; armament 10 6-inch, 2 3-inch, 4 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Omaha)

The second Omaha (CL-4) was laid down on 6 December 1918 at Tacoma, Wash., by the Todd Dry Dock & Construction Co.; launched on 14 December 1920; sponsored by Miss Louise Bushnell White, a descendant of David Bushnell, inventor of the submarine Turtle; and commissioned on 24 February 1923, Capt. David C. Hanrahan in command.

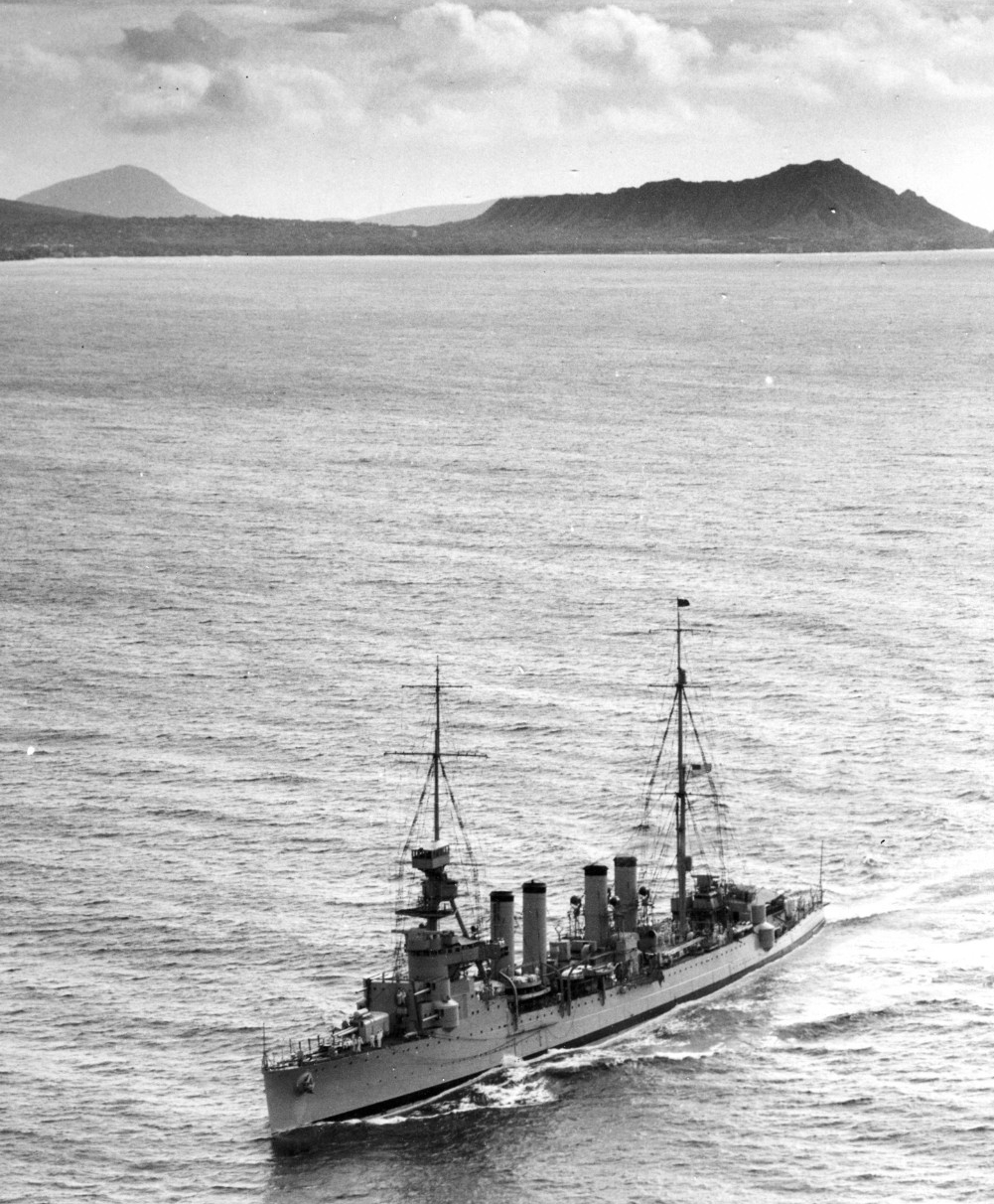

On 14 March 1923, Omaha departed Puget Sound, Wash. for San Pedro, Calif. After pausing at San Pedro (16–22 March), she continued on to Magdalena Bay, Mexico (24–31 March) to begin her shakedown. Omaha returned to San Pedro on 31 March where she spent the first few weeks of April testing her systems. On 19 April, the new light cruiser set course for the Territory of Hawaii (T.H.) to continue her shakedown. While in Hawaiian waters, she made port calls at Honolulu (24–31 April, 3–7 May), Hilo (30 April–3 May) and Pearl Harbor (5–8 May) before steaming to San Francisco, Calif. After giving her crew a break from sea duty in San Francisco (11–21 May), Omaha got underway to “show the flag” at the May Time Frolic and Empire Day at Victoria, British Columbia, Canada (23–27 May). She returned to Puget Sound and put into Bremerton, Wash., to undergo post-shakedown availability (27 June–4 August).

![Flying the stars and stripes at the fore and the White Ensign at the main, Omaha lies moored dressed overall, Victoria, British Columbia, 24 May 1923. Photograph by the Browne [or Brown’s] Studio. (U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships Photograph 19-N-9180, ... Flying the stars and stripes at the fore and the White Ensign at the main, Omaha lies moored dressed overall, Victoria, British Columbia, 24 May 1923. Photograph by the Browne [or Brown’s] Studio. (U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships Photograph 19-N-9180, ...](/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/omaha-ii/_jcr_content/body/media_asset_744737029/image.img.jpg/1491846166829.jpg)

During August 1923, Omaha remained in the vicinity of Puget Sound conducting speed trials (5–7 August) and completing her official standardization trials (1–19 August) before mooring at Tacoma. Omaha did not get underway again until she moved to Puget Sound Navy Yard where her aircraft catapults were installed (6–15 October). Omaha then proceeded to the Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif. (17–23 October) to load ammunition for target practice, then visited Portland, Ore., for the annual Navy Day Celebration (25–29 October 1923). She returned to Mare Island for repairs (31 October–10 November) before steaming back to San Pedro.

During the latter half of November and early December 1923, Omaha took part in multiple Short Range Battle Practice exercises with battleship Mississippi (BB-41), observing the latter’s gunnery during a firing exercise (6–7 December). On 8 December, Omaha joined the Battle Fleet for the first time as a member of the screening formation with other ships of her type. Soon thereafter, however, Rear Adm. Sumner E. W. Kittelle, Commander Destroyer Squadrons, unsatisfied with destroyer tender Melville (AD-2)’s suitability as a flagship, sought a suitable alternative. Consequently, on 27 December 1923, two days after Christmas, Omaha reported to serve as Rear Adm. Kittelle’s new flagship at San Diego, Calif.

Omaha got underway on 2 January 1924 with the Battle Fleet to participate in winter maneuvers at Panama. While the fleet was underway to Balboa, Canal Zone, events were occurring in Mexico that influenced the winter operating schedule. After Mexican Presidenté Álvaro Obregón endorsed Plutarco Elías Calles as his successor, former President Adolfo de la Huerta saw that as evidence of political corruption and, having failed to gain the presidency for himself, had launched a rebellion against the government on 7 December 1923.

On 12 January 1924, Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes notified Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby that forces loyal to Huerta had seized U.S. oil terminals at Port Lobos, Tuxpan, Vera Cruz, Mexico. The rebels also began interfering with the operations of U.S. corporations in the area. Huerta had also taken control of the city of Vera Cruz and closed the local cable office, cutting off communications for the U.S. Consulate. Consequently, President Calvin Coolidge ordered Secretary Denby to send a ship to Vera Cruz to reestablish communications and serve as refuge for fleeing Americans if needed.

The light cruiser Tacoma (CL-20), dispatched from Galveston, Texas, to Vera Cruz, [Arrecife Blanquilla] north of Tuxpan on 16 January 1924 shortly after her arrival, necessitating Richmond (CL-9) and several tugs being sent to assist her. On 18 January, Omaha and six destroyers transited the Panama Canal, then set course for Vera Cruz to increase the U.S. naval presence in the area. By 22 January, the conditions proved much calmer in Vera Cruz as much of the surrounding area was under Huerta’s control. Omaha reached Vera Cruz in deteriorating weather conditions on 23 January, but tragedy once again struck Tacoma when powerful waves, breaking over the battered warship’s hull, drowned Capt. Herbert G. Sparrow, Tacoma’s commanding officer, and three of his crew.

When the threat to U.S. interests appeared to be waning on 23 January 1924, Richmond, Omaha and their companions were ordered to steam into the Gulf of Mexico to rendezvous with the rest of the Battle Fleet. Before reaching the fleet, however, the ships received orders to reverse course, for on 24 January, the Consulate in Vera Cruz informed the State Department that the rebels forces intended to mine the ports of Vera Cruz and Frontera, Tabasco. Fortunately, it was soon learned that Huerta decided not to mine the ports and the cable office in Vera Cruz had reopened.

While Omaha lay off Vera Cruz, Huerta’s grip on the area began to slip in the face of the Obregón’s advancing troops. On 3 February 1924, she departed for Guantánamo, Cuba, to refuel with the intent of returning to Mexico. While she was at Guantánamo, however, the crisis abated when Huerta and his supporters evacuated Vera Cruz on 6 February. Omaha remained at Guantánamo (6–8 February) until she rejoined the Battle Fleet on 10 February.

The fleet concluded their winter exercises in Vieques Sound (10–16 February 1924), after which Omaha put into St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands (16–18 February) for rest and recreation. She rejoined the Battle Fleet until it dispersed to various ports for leave on 27 February. Omaha arrived at her assigned liberty port, Galveston, on 1 March where she remained until the 12th. She got underway for Key West, Fla., where ComDesRons transferred his flag back to Melville (14 March). She then proceeded to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Philadelphia, Pa. for repairs to her propellers (17–29 March). Omaha returned to Guantánamo (1–2 April) for maneuvers with the Battle Fleet (5–7 March) before proceeding to the Panama Canal to return to the Pacific (12 March). Omaha returned to San Diego on 22 April.

For the rest of 1924, Omaha operated along the coasts of California and the Pacific Northwest. During that period she made multiple port calls including holiday visits at San Francisco for Memorial Day (30–31 May) and Portland for Independence Day (1–5 July). She returned to Puget Sound for maintenance, repairs and machinery overhauls at Port Angeles and Tacoma (5 July–15 August). She ended 1924 at San Diego, and remained in the waters of southern California until getting underway for San Francisco (5–15 April 1925) to join the fleet bound for Pearl Harbor (27–30 April).

Omaha spent the early summer months of 1925 operating in Hawaiian waters (1 May–30 June). On 1 July, she departed Pearl Harbor with the Battle Fleet for Australia by way of Pago Pago, American Samoa (11 July). While en route, Omaha, Altair (AD-11), Melville, along with DesRons Eleven and Twelve, were detached from the main fleet to steam toward Melbourne, Australia. The group arrived at their destination on 23 July. After several days in port (23 July–6 August), Omaha, Adm. Robert E. Coontz ,Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, embarked, got underway for Lyttelton, New Zealand (11–21 August). She then proceeded to Wellington, New Zealand (22–24 August) to rejoin the Battle Fleet. On 24 August, the entire fleet departed for Pago Pago (1–2 September) Omaha then proceeded singly (3–15 September) to Puget Sound for overhaul (15 September–12 December). Steaming via San Francisco (12 December), she returned to San Diego on 14 December.

Omaha spent the next several years conducting routine operations along the Pacific coasts of the western U.S. and Central America, and in the Caribbean. She returned to Panama for Battle Fleet exercises (15 February–12 March 1926) then returned to San Diego (31 March). After spending the latter half of June at sea, Omaha put into Bellingham, Wash., to celebrate the 4th of July. On 8 September, in accordance with recommendations of the Chief of Naval Operations, the Commanders in Chief of the U.S. and Battle Fleets, in addition to their subordinate commanding officers, the Secretary of the Navy ordered the removal of all mines and mine tracks from all Omaha-class cruisers.

In early 1927, while she was underway from San Diego to Balboa (29 February 1927), one of Omaha’s embarked seaplanes crashed. The aircraft, a Vought OU-1 (BuNo A-6485) from Observation Squadron (VO) Four piloted by Lt. Robert P. McConnell (a recipient of the Medal of Honor for heroism at Vera Cruz in 1914) broke her forward pontoon struts and flipped onto its back upon landing. This left her hoist-slings underwater and the presence of sharks prevented any attempt to reach them. Finally, it was decided to attach a line to the tail section of the plane to right it and gain access the slings which “wrecked” the tail. Both of her aircraft were modified to provide access to the slings if a similar accident recurred. For the next two years, Omaha remained in western coastal waters putting into her usual ports at San Diego, San Francisco, Bremerton, etc., with the exception of returning to the Hawaiian Territory in the late spring of 1928 (18 April–15 June).

In early fall of 1930, Omaha was dispatched to San Francisco from San Pedro to embark members of the American Samoa Commission – Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut, chairman, Senator Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas, and Representatives Carroll L. Beedy of Maine and Guinn Williams of Texas – who were to investigate conditions and make pertinent legislative recommendations to Congress upon their return. Omaha cleared San Pedro for Pearl Harbor on 11 September. She arrived seven days later at Pearl Harbor then proceeded to Pago Pago on 20 September. Ultimately, the light cruiser arrived at Pago Pago on 26 September. Upon the conclusion of the commission’s business, Omaha began her voyage back to San Diego on 7 October, pausing at Pearl Harbor (13–14 October). She disembarked the commission members at San Pedro (19 October) before putting into San Diego on 20 October.

In 1931, Omaha returned to the Atlantic after participating in exercises in the Caribbean (25 March–2 May). She took part in joint maneuvers with the Army in Hampton Roads (25–29 May) before continuing on to Newport, R.I. (30 May). Omaha continued her participation in maneuvers at Newport, Hampton Roads, and the Southern Drill Grounds until putting into the Boston [Mass.] Navy Yard on 30 October. She remained there until after the New Year (4 January 1932) when she got underway to return to the Pacific.

Omaha arrived at San Diego on 14 January 1932. From early 1932 until the mid-summer of 1937, Omaha’s schedule fell into a routine. She steamed along the western coast and return on several occasions to Panama for exercises and fleet problems, and also operated in Hawaiian waters during that time.

In December 1933, while undergoing overhaul at Bremerton, she received additional antiaircraft guns and improvements to her aircraft handling capabilities. Omaha returned to the Atlantic and the Caribbean in 1934. There was a slight break in her routine when she steamed to the Aleutian Islands in 1935, putting into Dutch Harbor (9–10 May) and Kuluk Bay (11–14 May). She departed Alaskan waters for Pearl Harbor (24–31 May) before mooring at San Diego on 31 May.

On 19 July 1937, after being relieved as the flagship of the Special Service Squadron by the gunboat Erie (PG-50), Omaha grounded on a reef near Castle Island, British West Indies. According to the ensuing investigation, “she quickly and evenly decelerated as the bottom engaged the smooth reef.” The incident had also occurred during high tide which increased the difficulty of dislodging the cruiser. Salvagers devised a plan to lighten the ship as much as possible by removing unnecessary items, to employ multiple tugs and use destroyers to create waves by circling Omaha, outside the perimeter of the tugs. Several tugs and ships from DesRon Ten were sent to put the plan into action. After ten days, and many failed efforts, Omaha floated free on 29 July. The following day, she got underway for the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., where she underwent repairs (3 August 1937–14 February 1938). In the wake of the grounding, a general court martial, on 11 October 1937, convicted Capt. Howard B. Mecleary, Omaha’s commanding officer, of negligence “resulting in the stranding of the vessel” and sentenced him to lose 25 numbers on the captain’s list.

With her hull damage repaired, Omaha got underway with a new commanding officer, Capt. Wallace L. Lind, on 14 February 1938 to conduct sea trials en route to Guantánamo (28 February). She put into Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk in late March.

After just two days’ rest (29–30 March 1938), Omaha departed for Gibraltar and duty in the Mediterranean Sea. She arrived at Marseilles, France, on 27 April 1938 and remained in the Mediterranean until the late spring of 1939. During that period, she visited Marseilles, Villefranche-sur-mer, and Menton, France. After making a final port call at Malta (25 April–2 May 1939), Omaha got underway to return to the U.S.

Omaha put into the Norfolk Navy Yard on 17 June 1939 where she began an extensive overhaul that lasted until October 1939, during which time, on 1 September, Germany invaded Poland and once again, war ravaged the European continent. Omaha moved to NOB Norfolk to begin her post-overhaul sea trails (12–25 October) before being detached to proceed to Guantánamo to operate in the Caribbean conducting gunnery and tactical exercises.

Subsequently, on 6 December 1939, Omaha arrived at Havana to embark the body of the late U.S. Ambassador to Cuba J. Butler Wright, who had died on 4 December. The warship then transported Ambassador Wright’s remains to Washington, D.C. via Marine Barracks Quantico (10–11 December). Once she had accomplished that sad mission, Omaha returned to NOB Norfolk on 12 December where she remained until 1 April 1940.

Omaha got underway to the Caribbean on 1 April 1940 via the Philadelphia Navy Yard (3–5 April). She put into San Juan, Puerto Rico (12–16 April) before proceeding to Guantánamo (22–23 April) and Havana (20–23 April). By early May, she was back at Philadelphia (3–5 May). After a brief port call at Newport (5–6 May), Omaha was at sea in the Hampton Roads (7–28 May) then returned to Norfolk on 28 May 1940. She remained at Norfolk until she put to sea on 22 June for her new assignment as the flagship for Squadron 40-T at Lisbon, Portugal. This was a temporary squadron under the direct command of the Chief of Naval Operations, formed during the Spanish Civil War to stand ready to protect U.S. interests and civilians in Spain.

As Omaha stood in to Lisbon harbor, she passed her sister ship Trenton (CL-11), her predecessor, standing out bound for the U.S. As the two ships passed, each of their crews greeted their compatriots with waves and loud cheers. Omaha’s band played “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight” while Trenton’s musicians responded with “Empty Saddle in the Old Corral.” During her time as flagship, ship remained in the vicinity of Lisbon until the squadron was disbanded in October 1940. She got underway for the U.S. on 3 October making port calls at Monrovia, Liberia (9–10 October) and Pernambuco, Brazil (14–15 October). She put into NOB Norfolk on 23 October and remained in port until 7 November.

During the next several months (7 November 1940–13 February 1941), Omaha made return voyages to the Caribbean for tactical training and gunnery exercises. She made routine stops at Guantánamo, Culebra, and St. Thomas. After a brief stay at Norfolk (13 February), she got underway for Brooklyn, N.Y. On 17 February, Omaha entered the New York Navy Yard for overhaul (17 February–28 April 1941). It was during that overhaul that Omaha had her first radar system installed.

Once her overhaul was completed (28 April 1941), Omaha got underway but soon developed engine trouble that forced her to return to Brooklyn. It took several weeks (17 May–25 June) for repairs to her No.4 turbine. While she was undergoing repairs there was a significant increase in the German U-boat activity in the Southern Atlantic. The U.S. was already conducting Neutrality patrols and escorting merchant convoys in the North Atlantic.

On 21 May 1941, the German submarine U-69 (Kapitänleutnant Jost Metzler, commanding) stopped the U.S. freighter Robin Moor, en route to Mozambique, some 750 nautical miles west of Freetown, Sierra Leone, British Crown Colony [Republic of Sierra Leone]. The German submariners forced Robin Moor’s 38-man crew and eight passengers into four lifeboats, provided them with rations, after which U-69 submerged, fired a torpedo into the merchantman’s stern, then resurfaced and sent Robin Moor to the bottom with her deck gun. A Capetown, South Africa-bound British ship rescued 35 survivors on 3 June, and the Brazilian freighter Osorio picked up the remaining 11.

In a message to Congress on 20 June 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt stated that Germany “flagrantly violated the right of the United States” and was trying to “drive American Commerce from the ocean.” President Roosevelt went on to note that Robin Moor’s destruction constituted a “warning to the United States may use the high seas of the world only with Nazi consent. Were we to yield on this we would inevitably submit to world-domination at the hands of the present leaders of the German Reich. We are not yielding,” the President declared, “and we do not propose to yield.”

Only a short time before, on 15 June 1941, Task Force (TF) 3, commanded by Rear Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, had inaugurated patrol operations from the Brazilian ports of Recife and Bahia; resources available to Ingram included Omaha and three of her sister ships, and five destroyers. Her propulsion and engineering issues resolved, Omaha stood out on 30 June to conduct Neutrality Patrols between Recife and Ascension Island, British Overseas Territory. It was Omaha’s duty, as part of Ingram’s force, to intercept, board, and inspect vessels to enforce a blockade against German trade in the region. She also served as a convoy escort to protect the shipping lanes between South America and West Africa. During that period she made port calls to Montevideo, Uruguay, as well as Bahia and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She operated under war conditions.

On 4 November 1941, the British oiler Olwen reported a German surface raider attack at 03°04'N, 22°42'W, prompting Vice Adm. Algernon U. Willis, RN, Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic, to order the heavy cruiser HMS Dorsetshire (accompanied by the armed merchant cruiser HMS Canton) to investigate. Light cruiser HMS Dunedin and special service vessels HMS Queen Emma and Princess Beatrix were ordered to depart Freetown, Sierra Leone, to join in the search.

Dorsetshire and Canton then parted company, with the former steaming southeast and the latter heading toward a position to the northwest, the Royal Navy ships to be supported by TG 3.6, Omaha and destroyer Somers (DD-381), which were at that time well to the northwest of the reported position. Memphis (CL-13) and the destroyers Davis (DD-395) and Jouett (DD-396), near to the location given by Olwen, searched the area without result, while Omaha and Somers search unsuccessfully for survivors. The next day [5 November], the search for the “German raider” reported by Olwen continued, with Vice Adm. Willis informing his ships of the unsuccessful efforts by the five U.S. ships (two light cruisers and three destroyers) that had been involved in the efforts the previous day

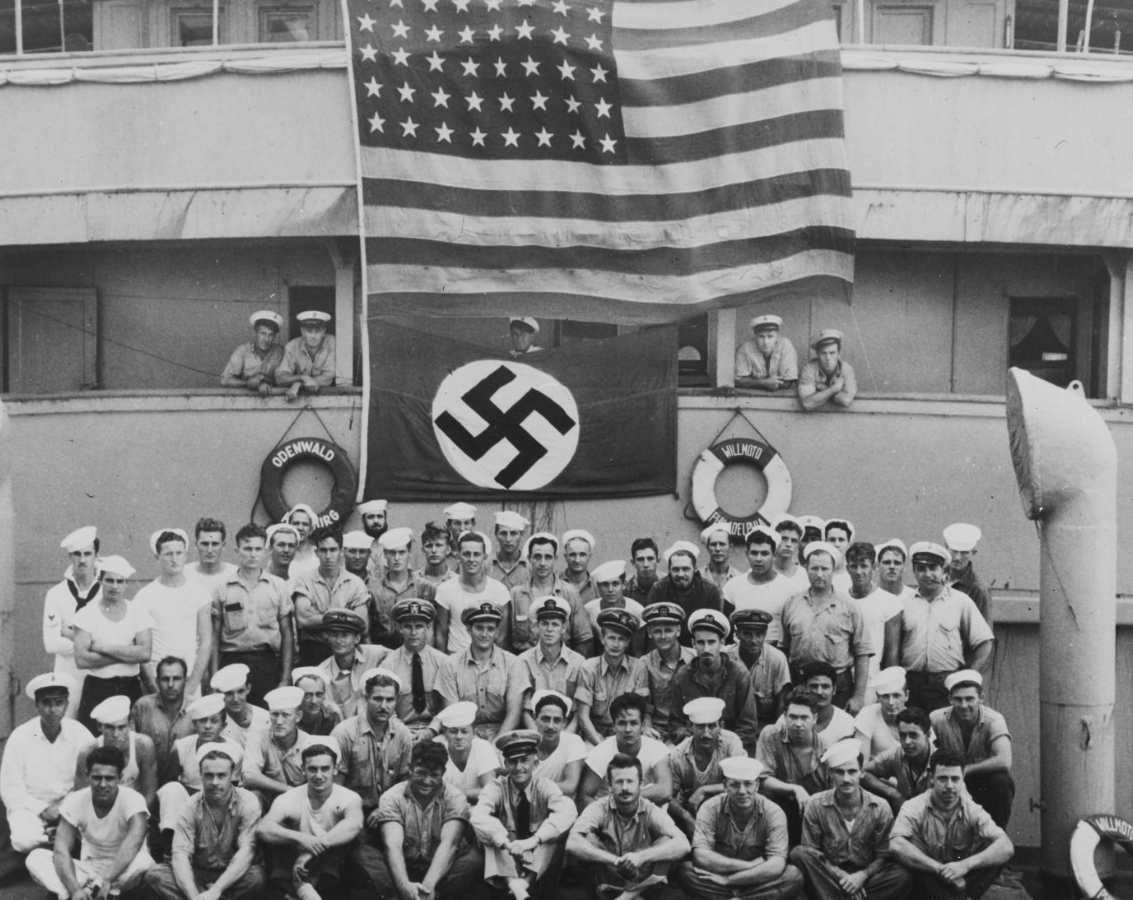

Ultimately, however, the unsuccessful search for the “German raider” reported by Olwen on 4 November 1941, proved not entirely fruitless, for on 6 November, TG 3.6, Omaha and Somers, en route to Recife and returning from a 3,023-mile patrol in Atlantic equatorial waters, sighted smoke on the horizon at 0506. Capt. Theodore E. Chandler put Omaha on a course to intercept. As Omaha grew closer, the ship -- flying U.S. colors and the name on her stern identifying her as Willmoto of Philadelphia, Pa. -- began taking evasive action. Multiple attempts made to communicate with the steamer went either unanswered or were given suspicious responses. Omaha’s lookouts reported the many of the crew on the deck where “uniquely un-American in appearance.”

At 0537, Lt. George K. Carmichael and an armed boarding party began making their way toward the vessel. At that point the steamer hoisted the international symbol “Fox Mike,” indicating that she was sinking and required assistance. As the boarding party began ascending the ship’s ladder, they heard two distinct explosions within the ship. Several of the sinking ship’s crew had lowered lifeboats and were attempting to leave, but Carmichael ordered them back on board. At 0558, Carmichael signaled Omaha stating that the ship that had acted in such a suspicious manner was indeed German and was sinking. She was the German blockade runner Odenwald – her holds filled with 3,857 metric tons of rubber, 103 B. F. Goodrich truck tires and a sundry other cargo all totaling 6,223 metric tons total.

Omaha’s sailors, joined by a diesel engine specialist from Somers’s ship’s company, prevented Odenwald’s loss while the cruiser’s SOC floatplanes and her accompanying destroyer screened the operation. The three ships then proceed to Port of Spain, Trinidad, because of possible complications with the Brazilian government. In view of the precarious fuel state in the U.S. ships, Somers’s crew ingeniously rigged a sail that cut fuel consumption, but all reached their destination with fuel to spare. Ironically, the British RFA oiler Olwen later reported that she had made the “raider” signal when what was probably a surfaced submarine had fired upon her at dawn. While ten U.S. and British warships had searched for two days for a phantom enemy, however, two of the U.S. ships had ended up capturing a blockade runner.

On 17 November 1941, Omaha stood in to the harbor at Port of Spain with Odenwald flying her German flag with the U.S. colors flying above it on the mast. Several years later, on 30 April 1947, in a case brought by Odenwald’s owners against the U. S., the District Court for Puerto Rico held that since a state of war did not exist at that time between the U.S. and Germany, the vessel was not taken for a prize or bounty. Also, given the fact Odenwald was saved from sinking, that the taking of the vessel was legally defined as a salvage operation. The U.S. government was awarded the profits made off of Odenwald and the men of the boarding party were given $3,000 each. Consequently, the laws were changed and this was the last time such an award was paid to members of the Navy.

There was little time for celebration. On 7 December 1941, while steaming with Somers to Recife from San Juan, Omaha received communication informing her commanding officer about the Japanese attack on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and to “execute WPL [war plan] 46 against Japan.” Capt. Chandler mustered the crew and read them the entire message. The U.S. Congress officially declared war on the Empire of Japan on 8 December. Three days later, Germany declared war on the United States (11 December 1941). Prior to the German declaration, the Kriegsmarine had been prohibited from attacking U.S. convoys. That restriction was now lifted. In just a few short days protecting the shipping lanes between South America and Africa became exponentially more hazardous for Omaha and her compatriots.

Omaha continued to do her part to keep ships in the southern Atlantic as safe as possible from attack. She searched with her radar, sound equipment and floatplanes for enemy ships and steamers transporting contraband that could aid the Nazi war effort.

While on patrol in company with Jouett on 8 May 1942, Omaha came across the Swedish motor vessel Astri. The light cruiser’s boarding party discovered Ens. John F. Kelly, USNR, six members of the armed guard detachment and eight crewmen from the U.S. freighter Lammot Du Pont that had been torpedoed and sunk by U-125 (Kapitänleutnnt Ulrich Folkers) 500 miles southeast of Bermuda on 23 April. The 15 men had been adrift in life rafts for two days before being found by Astri. Omaha -- informed that the Office of Naval Operations (OpNav) had suspected Astri of being a tender for German submarines -- left Jouett on station to investigate the neutral vessel while Omaha set course to Recife with Lammot Du Pont’s survivors. Directed to the scene by a patrolling aircraft, destroyer Tarbell (DD-142) rescued the remaining 23 survivors on 16 May.

On 18 May 1942, Omaha intercepted an urgent dispatch giving the location of the Brazilian steamer Commandante Lyra that had been torpedoed. The merchant ship had been attacked by the Italian submarine Barbarigo. In the initial attack, Commandante Lyra was struck by a torpedo on her starboard side. Barbarigo then surfaced and began shelling the disabled ship. Upon receiving the coordinates, Omaha immediately set a course to the area, and when she arrived the next day found her sister ship Milwaukee (CL-5), the destroyer Moffett (DD-362), and small seaplane tender (ex-minesweeper) Thrush (AVP-3) on the scene. Commandante Lyra was fully ablaze and it was decided that any attempt to board her was too dangerous. Instead, the ships began to search the area for survivors. Milwaukee and Moffett pulled 41 survivors from the sea. Once the fire had mostly abated and was isolated to her stern, a salvage party was sent aboard Commandante Lyra to assess her seaworthiness. The team determined the ship would sink in three to four hours. Men from Omaha and her companions, however, proved able to keep Commandante Lyra afloat. On 20 May, once the threat of sinking was removed, Thrush, covered by Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats from Patrol Squadron (VP-83), towed the salvaged steamer to Fortaleza, Brazil (20–25 May 1942).

On 1 June 1942 at 0130, Omaha sighted a small light on the horizon. This light turned out to be a small lifeboat carrying eight crewmen from the British merchant Charlbury. The merchant had been attacked by on 28 May while en route to Buenos Aires, Argentina. The first enemy torpedo had missed the ship. The submarine then surfaced, attacked with “withering gunfire,” and submerged. Charlbury was then struck by a second torpedo after which she sank by the stern. Several hours later, Omaha encountered more survivors. In all, Omaha pulled 40 men from the water and carried them to Recife. Two of Charlbury’s men had been slain by the submarine’s gunfire.

A week later, on 8 June 1942, Omaha found eight British seamen on board the Argentinian merchantman Rio Diamante, the only survivors (41 men had perished in the sinking) from the British merchant Harpagon that had been torpedoed and sunk by U-109 (Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Bleichrodt) near Bermuda on 20 April. The men, who had been adrift for 35 days, opted to remain in Rio Diamante, which transported them to Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In early June 1942, following a brief upkeep period at San Juan during which she received a new camouflage pattern, Omaha escorted a convoy carrying 400 M-4 Sherman tanks to Ascension Island. There she was relieved by a British convoy carrying soldiers to Europe. Throughout the summer, Omaha continued patrolling the southern Atlantic and escorting convoys.

During 16–17 August 1942, U-507 (Korvettenkapitän Harro Schact) sank five Brazilian merchantmen, attacks that killed over 500 men, outside of Brazil’s territorial waters, and destroyed a sixth vessel flying Brazilian colors on the 19th. Shortly thereafter, while waiting for a harbor pilot at Montevideo, Uruguay (22 August), Omaha’s crew got a close look at the rusting wreck of the German armored ship Graf Spee, that had been scuttled there on 18 December 1939 following the Battle of the River Plate. After Omaha had moored, Capt. Chandler received a visit from Brazilian naval officer, who informed him that Brazil was preparing a declaration of war against Germany and Italy. The declaration was promulgated that day (22 August 1942).

Although the threat from the enemy had lessened by August 1942, there were other ways the men of Omaha could be harmed. While she was anchored in Carenage Bay, Trinidad, one of Omaha's sailors returned after indulging in an especially “hard liberty.” The man was sleeping off the effects on the direction finder deck when the ship took an unexpected roll. The inebriated bluejacket rolled off of the deck, down the awning over the quarterdeck and over the side of the ship. According to Capt. Chandler, he was uninjured “probably due to his perfectly relaxed condition.” Other such incidents did not end as well.

While back at Trinidad (30 October 1942), the side of a truck carrying Omaha’s baseball team fell off taking six players with it. There were no serious injuries, just some sprained ankles, lacerations and contusions. On 2 November 1942, Omaha launched one of her new Vought OS2U Kingfishers for the first time while on escort duty in company with Marblehead (CL-12). Three days later (5 November) an aviator flipped one of Omaha's new Kingfishers upon landing. The aviator was uninjured but the plane was seriously damaged and required an overhaul when Omaha put into port. Tragedy struck Marblehead on 17 November 1942. While hoisting her whaleboat carrying a landing party back aboard, one of the sailors fell overboard and never resurfaced. The man was wearing a new style life vest that required manual inflation by mouth. Following that fatality, Capt. Chandler ordered that all of Omaha’s boarding party members to wear the older style life jackets. Despite the fact they were cumbersome and bulky, the jackets were effective.

On 30 December 1942, Omaha departed Recife with Jouett for the U.S. After unloading ammunition at Trinidad on 5 November, the two ships continued on toward home. Jouett parted company with Omaha on 8 November to put into Charleston, S.C., while Omaha continued to the New York Navy Yard, arriving there on 11 December to begin an overhaul and give her sailors some well-deserved time off in the city. Unfortunately, local conditions – a full barracks and housing in short supply due to a local Scarlet Fever outbreak – necessitated her crew remaining on board during the overhaul. While at Brooklyn, five of Omaha’s officers married.

Having completed sea trials and gunnery training by 13 March 1943, Omaha returned to regular duties operating out of Recife, escorting the stores ship Pollux (AKS-4). Throughout the year Omaha did not encounter any enemy vessel or the results of their handiwork. She continued patrolling the southern Atlantic often in the company of sister ships Milwaukee, Memphis (CL-13), Cincinnati (CL-6) and Moffett.

While changing stations on formation on 30 April 1943, Milwaukee grazed Omaha’s starboard bow, destroying one of the latter’s paravanes and ruptured some plating, causing flooding. Omaha’s damage control party was able to execute makeshift repairs, stopping one leak by shoring up two mattresses in the hole. One compartment flooded completely and a second had to be pumped out every two hours. One of Milwaukee’s port 6-inch guns and torpedo tube mount were put out of commission. She also had several holes in her side above the main deck. She had some leaking under the waterline due to damaged plates and rivets in addition to losing her No.3 main circulation pump. The damage having been determined not serious enough to discontinue their mission, the two cruisers completed their patrol, then put into Rio de Janeiro for repairs at the Brazilian Navy Yard.

Omaha’s time of relatively uneventful operations came to an abrupt halt on 4 January 1944. While on patrol, Omaha and Jouett began to pursue an unidentified ship about 55 miles northeast of the Brazilian coast. At 1020, Omaha challenged the vessel with her searchlight but elicited no response. Lookouts spotted two guns on the ship’s bow. Several minutes later, a large cloud of heavy smoke was seen issuing from the ship’s stern, leading to the assumption that her crew was scuttling her to avoid capture. Omaha maneuvered along the ship’s port side and began firing with her starboard battery. Jouett also opened fire. The ship’s crew were seen trying to escape in lifeboats off of her stern. Omaha attempted to drive the men back using machine guns. It soon became obvious that the ship was lost. Omaha again opened fire on the vessel and shortly afterwards, she sank by the stern. Fearing that the action might have drawn the attention of enemy submarines, Omaha and Jouett departed the area without picking up the survivors. It was later determined that the ship was the German blockade runner Rio Grande. Omaha’s sister ship Marblehead rescued 72 survivors on 8 January.

The following day [5 January 1944], while she steamed in the vicinity of where Rio Grande had met her end, Omaha encountered another unidentified steamer, and again challenged the ship with her searchlight. After receiving no response, she fired two shots over the suspect’s bow as she appeared to be dead in the water. An explosion was seen on the ship followed by billows of smoke. Omaha trained her 6-inch battery on the ship and opened fire. Because many members of Omaha’s crew had been unable to witness the previous day’s action, Capt. Elwood M. Tillson allowed his men to rotate topside to watch the gunfire. Thirty minutes later, the steamer -- later identified as Burgenland, another German blockade runner -- sank by the stern. Davis rescued 21 of her survivors on 7 January; Winslow (DD-359) retrieved an additional 35 on the following day [8 January].

A little over a month later, on 6 February 1944, while Omaha was patrolling with Jouett and Memphis, the ships received orders to keep watch for survivors of a U-boat that had been sunk in their vicinity. Jouett sighted wreckage and shortly afterward Omaha’s forward lookout spotted a yellow life raft that was occupied. When the cruiser neared the raft, she lowered one of her 26-foot whaleboats to collect the enemy submariners. The German sailors were survivors from sinking of U-177 that was sunk on 6 February 1944. Before the submarine was attacked, U-177 lay on the surface with some of her crew sunning and swimming. The U-boat was spotted by a Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberator from Bombing Squadron (VB) 107 operating from Ascension Island. The bomber attacked with its depth charges.

According to Leutnant Hans-Otto Brodt, one of 14 survivors, fifty men, including Korvettenkapitän Heinz Bucholz, their commanding officer, had gone down with the ship. While in Omaha, the prisoners were taken to the sick bay to be treated for shock and exposure. They were then placed under armed guard and given fresh clothing that was provided by the Red Cross. After the ship put into Bahia (15 February 1944), the Germans were disembarked and transported to Recife.

Soon afterward [16 February 1944], Omaha hosted First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Rear Adm. Oliver M. Read, Commander, Surface Patrol Force (TF 41). Before the ship left port, on 19 February, a local athletic club treated Omaha’s officers to a celebration of the beginning of Carnival. Ultimately, the cruiser departed Bahia on 21 February to escort the U.S. Army Transport State of Maryland back to the U.S. in company with Christopher (DE-100).

After several months of patrolling and escorting convoys, Omaha got underway to the European Theatre with destroyer escorts Marts (DE-174), Reybold (DE-177), and troop transport General W. A. Mann (AP-112) on 4 July 1944. The convoy arrived at Gibraltar on 13 July with the addition of Marsh (DE-699), Hollis (DE-794) and the destroyer Kearney (DD-432). Omaha then remained at Gibraltar (13-18 July) until she got underway for Palermo, Sicily, with the battleships Nevada (BB-36) and Arkansas (BB-33) on 18 July. While the crew was enjoying a little rest at Palermo watching a film on the fantail, the last reel caught fire in the projector. The film was a complete loss but the projector survived (21 July 1944).

On 6 August 1944, Omaha steamed to Ajaccio, Corsica, to join a task force preparing to assault Île de Port-Cros, France. As she lay off Île d' Hyéres, Omaha observed the bombardment of a fort still held by German forces at Île de Port-Cros. Once the enemy surrendered, Omaha embarked 10 Army casualties and 22 German prisoners (17 August). One prisoner, Oberleutnant G. A. Hildebrandt, had been severely wounding in the fight. The ships medical staff treated the German officer then transferred him, alone with three wounded U.S. officers, to the hospital ship Acadia.

The following day, Omaha was protecting the flank of a formation, consisting of the heavy cruisers Quincy (CA-71) and Augusta (CA-31), and Nevada and the French battleship Lorraine (K.258), bombarding Toulon, France. Omaha fired 24 rounds as part of the bombardment. At 1717, she drew fire from a shore battery which Quincy responded to by laying out a smoke screen. Omaha fired 3.5-inch rockets to jam the enemy radar. After supporting Nevada on 20 August, the light cruiser once again drew enemy fire as she departed the area. Fortunately, the shells splashed 1,000 yards off her stern and 3,000 yards off her port quarter.

While at Porquerolles, France, the net tender Hackenberry (AN-25) came under fire from a shore battery. Omaha quickly sprang into action to protect the tender, silencing the enemy position with 73 6-inch rounds. On 23 August, Omaha was dispatched with a task force to Giens Peninsula at Rade d' Hyères, France, to deploy a landing to force the occupying Germans to surrender. Once she arrived on station, flags of surrender were already flying so the bombardment was cancelled. Motor torpedo boat PT-533 carried the landing party ashore to confirm the surrender and arrange the landing of Allied troops.

Omaha departed the assault area on 27 August 1944 to return to Palermo. She then got underway to Oran, Algeria, with Cincinnati (CL-6), Marblehead, Quincy, the destroyer McLanahan (DD-615). The group departed Oran on 1 September, with the addition of Mackenzie (DD-614), to transit the Strait of Gibraltar and continued on to Bahia. When the formation entered the Atlantic, Marblehead was detached and proceeded to the west independently.

Once Omaha returned to Bahia (9 September 1944), she resumed her previous duties patrolling the southern Atlantic and providing escort services. During this period she made port calls at Rio de Janeiro (18–26 October, 9–22 November) and Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (29–31 October). She returned to the North Atlantic, escorting the transport General M. C. Meigs (AP-116) in company with the Brazilian destroyers Mariz E. Barros and Marcilio Diaz to Gibraltar (27 November–4 December). Omaha turned over her escort duty to Edison (DD-439) on 4 December then proceeded independently to Sandy Hook, N.J. She arrived at New Jersey on 14 December then put into the New York Navy Yard the next day. Omaha ended 1944 undergoing repairs and alterations to improve her living spaces.

Omaha departed New York on 8 February 1945 and began working her way back to Recife. After putting into Guantánamo 17 February, she took part in training exercises in Caribbean (19–25 February). While participating in these evolutions, one of her Kingfishers broke apart upon launching off the catapult. The pilot and his passenger were not seriously hurt, but both suffered head injuries in the mishap (24 February). Once she returned to Recife, Omaha resumed patrol and convoy escort duties. On 10 March, while at Recife, a ceremony was held to award the Omaha’s commander, Capt. Elwood M. Tillson, the Silver Star medal for the combat action in the Mediterranean during August 1944. Subsequently, while underway for Buenos Aires, the entire crew mustered to hold a solemn memorial service (15 April) for President Roosevelt after being informed of his death on 12 April 1945.

On 8 July 1945, Omaha departed Recife on a search and rescue operation after the Brazilian cruiser Bahia (C.12) had been reportedly sunk by a submarine. The British steamer Balfe reported that she had rescued 33 survivors, three of whom later succumbed to their injuries. Omaha intercepted Balfe and transferred over her medical staff to aid in treating the castaways. The Brazilian destroyer Greenhalgh (M.3) discovered one additional survivor on 11 July 1945. One Brazilian seaman reported that he had been in a life raft with three U.S. sailors that eventually died. He did not know their names or rates. As the search continued, what caused the vessel to sink became unclear. Many of her sailors reported a large explosion but the source could not be determined. After the search was concluded, 44 men, of whom seven died, and eight bodies, were recovered. The remainder of the crew, 294 men, had been lost. Eventually, an investigation determined the cause of the explosion on board Bahia. While conducting anti-aircraft training on 4 July, one of her gunners had shot down a kite target and continued firing as he trailed the target’s descent. Without proper safety stops installed on his gun, he inadvertently fired into a rack of live depth charges on the fantail.

Following the Bahia tragedy, Omaha remained in the South Atlantic area until 11 August 1945. She departed Recife for the last time the next day [12 August]. After pausing at San Juan (19–22 August) and Norfolk (25–30 August) she got underway for the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard (1 September). Soon thereafter, a Board of Inspection and Survey recommended that Omaha be taken out of commission.

Decommissioned on 1 November 1945, Omaha was stricken from the Navy Register on 28 November 1945. She was scrapped at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard by February 1946.

Omaha received one battle star for her World War II service.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. David C. Hanrahan | 24 February 1923 |

| Capt. Frederick J. Horne | 14 June 1924 |

| Capt. Cyrus W. Cole | 16 January 1926 |

| Capt. Allen Buchanan | 25 August 1927 |

| Capt. John Downes | 6 November 1929 |

| Capt. Andrew C. Pickens | 22 May 1930 |

| Capt. Jonathan S. Dowell Jr. | 14 May 1932 |

| Capt. James S. Woods | 4 June 1934 |

| Capt. Herbert A. Jones | 14 December 1935 |

| Capt. Howard B. Mecleary | 10 September 1936 |

| Capt. Wallace L. Lind | 17 January 1938 |

| Capt. Lyal A. Davidson | 1 February 1939 |

| Capt. Paulus P. Powell | 1 September 1939 |

| Capt. Theodore E. Chandler | 15 October 1941 |

| Capt. Charles D. Leffler, Jr. | 1 April 1943 |

| Capt. Elwood M. Tillson | 10 March 1944 |

| Capt. William L. Freseman | 23 June 1945 |

| Cmdr. Albert D. Lucas | 24 September 1945 |

John W. Watts, Jr.

7 April 2017