H-051-1: The Last Sacrifices

This turned into a bit of an opus, but it is my tribute to those ships and Navy personnel who made the ultimate sacrifice in the waning days of World War II.

24 January 1945: USS Extractor (ARS-15) —the Last U.S. Ship Sunk by “Friendly Fire”

On 21 January 1945, the Anchor-class rescue and salvage ship Extractor departed Guam en route Leyte, Philippines, under the command of Lieutenant (j.g.) Horace M. Babcock, USNR, with a crew of 79. On 23 January, the ship received a garbled operational priority message that could not be decoded. Mindful of the requirement to maintain radio silence, the crew did not request a retransmission of the message. The message had directed Extractor to reverse course and return to Guam. Unknown to routing authorities there, Extractor continued on her way toward the Philippines.

At 2038 on 23 January 1945, the submarine Guardfish (SS-217) made radar contact on an unknown vessel at 11,000 yards. Guardfish was a veteran boat on her 10th war patrol, having earned a Presidential Unit Citation for her First and Second War Patrols and a second Presidential Unit Citation for her eighth war patrol. The present patrol was her first under Commander Douglas Thompson Hammond and was up to this point a complete bust. She was returning to Guam empty-handed.

Guardfish tracked the contact through the night. Commander Hammond was well aware that the contact was in a “Joint Zone,” where both U.S. submarines and surface ships could operate, and in which neither was allowed to attack contacts without positive identification and confirmation that the target was hostile. At 0113, Guardfish issued a contact report to Commander, Submarines Pacific (COMSUBPAC), requesting to know if there were any friendlies in the area. COMSUBPAC replied that there were no friendly submarines in the area, and warned that the contact might be American, while directing Guardfish to continue to track the contact. Upon Guardfish issuing another contact report, COMSUBPAC replied at 0338 that there were no friendlies in the area, unaware that Extractor had not reversed course as ordered.

Having been informed that there were no friendlies in the area, Guardfish took a position at 0542 13,600 yards ahead of the contact’s track, with a 2,000-yard offset in order for the contact to be silhouetted against the predawn, eastern light. The seas were very choppy, and only the superstructure of the contact could be seen in the seas. Commander Thompson took four looks through the scope, and the executive officer two looks, as the contact approached. At 0605, both Thompson and the executive officer concurred that the contact was a Japanese type I-165-class submarine running on the surface. The Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) system had been incorporated into the air search radar (to warn the submarine against attack from friendly aircraft), but the surface search radar did not have IFF. As the contact was believed to be a Japanese submarine, Guardfish did not attempt to use underwater communications. At 0620 Guardfish fired four Mk. 18 electric torpedoes at the contact from a range of 1,200 yards, with one explosion heard 1 minute 18 seconds later and a second explosion 8 seconds after that.

Sonarmen on Extractor heard the incoming torpedoes, and General Quarters was sounded. In the very rough seas and low light, the lookouts did not see the torpedoes, however, and the ship had almost no time to maneuver anyway. At least one torpedo struck Extractor on the starboard side, in the engine room, killing or wounding everyone in the space. Within three minutes the ship was listing severely, with the risk of imminent capsizing. Lieutenant (j.g.) Babcock gave the order to abandon ship.

On Guardfish, at 0623, as soon as the smoke cleared, Commander Hammond saw Extractor’s stern start to rise out of the water. He realized that the contact was a surface ship and not a submarine. Extractor radioed a coded message that she had been hit and was sinking, which was heard and decoded by Guardfish as she was coming to the surface at 0630.

Guardfish immediately commenced rescue operations, bringing aboard 73 survivors over the next two hours, but six Extractor Sailors went down with the ship or were lost in the water. The Court of Inquiry determined that the sinking had been an unfortunate accident, absolving COMSUBPAC but criticizing Lieutenant (j.g.) Babcock for not breaking radio silence to request retransmission of an operational priority message. The court also criticized Commander Hammond for not using the underwater telephone. He received a formal letter of reprimand but remained in command of Guardfish for her last two war patrols, during which Guardfish only sank one Japanese fishing boat. At war’s end, Guardfish was the only U.S. submarine to sink another U.S. Navy ship.

During World War II, there were also accidental attacks on U.S. submarines by U.S. and Allied aircraft and ships. These attacks were distressingly frequent and provided a major impetus for developing IFF capability. Given how many of these “blue-on-blue” attacks there were, it is almost miraculous that more U.S. submarines escaped being sunk by our own forces—which is a testament to the skill of the submariners in avoiding being hit. It is also an indication of the great difficulty experienced by aircraft or ships in actually hitting a submarine. One U.S. submarine, Seawolf (SS-197), was almost certainly sunk by a U.S. destroyer escort. Two others, Dorado (SS-248) and S-26 (SS-131), were possibly sunk accidentally, by friendly forces.

USS Seawolf

On 3 October 1943, about 35 nautical miles east of Morotai (off the northwest tip of New Guinea), Japanese submarine RO-41 fired her last four torpedoes at the escort carriers of TG 77.1.2. The torpedoes missed Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70) and Midway (CVE-63, later re-named St. Lo) but not destroyer escort Shelton (DE-407), commanded by Lieutenant Commander Lewis B. Salmon, USNR. Shelton maneuvered to avoid the first torpedo, but a second torpedo hit her in the starboard propeller, causing extensive damage and progressive flooding. Destroyer escort Richard M. Rowell (DE-403) conducted an attack on a submarine before coming alongside Shelton and taking off her survivors. Thirteen of Shelton’s crew were killed, and although Shelton was taken in tow, she later capsized and sank. Two Midway aircraft subsequently sighted a submerging submarine and dropped two bombs and dye markers, despite being in a U.S. submarine safety lane. Richard M. Rowell prosecuted the datum and detected an acoustic signal that according to Richard M. Rowell bore no resemblance to any known recognition signals and was interpreted as a Japanese attempt to jam Richard M. Rowell’s sonar. Richard M. Rowell conducted several hedgehog attacks on the submarine and noted a small amount of debris and a large air bubble coming to the surface.

At 0756 on 3 October 1944, Seawolf had exchanged radar recognition signals with Narwhal (SS-167), which was the last heard of Seawolf. Following the attack on Shelton, all four U.S. submarines in the vicinity were directed to report their position; only Seawolf failed to respond. Seawolf, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Albert Marion Bontier (USNA ‘35), was on her 15th war patrol and was on a clandestine mission to the Philippines to deliver supplies to Filipino guerillas. She had previously sunk 14 Japanese ships. This patrol was Lieutenant Commander Bontier’s second as commanding officer of Seawolf. Bontier had previously been awarded a Silver Star as approach officer on the third war patrol of Spearfish (SS-190). In addition to her 83 crewmen, Seawolf had 17 U.S. Army passengers on board, all of whom were lost.

There were no Japanese reports indicating an attack on a U.S. submarine in that time or place. RO-41 returned safely to port and did not report attacking a submarine. (RO-41 was sunk off Okinawa in March 1945 with all 82 hands.) The commanding officer of Richard M. Rowell, Lieutenant Commander Harry Allen Barnard Jr. (USNA ’36), remained in command and was awarded a Legion of Merit for sinking a Japanese submarine on 23 October 1944 (some accounts say this was I-54, but it was more likely I-56, which got away). Although Seawolf might have been lost due to an operational accident or an unrecorded Japanese attack, it is probable she was sunk by accident by Richard M. Rowell.

USS Dorado

On the night of 12 October 1943, a PBM Mariner flying boat attacked what it assessed as two German U-boats two hours apart in the eastern approaches to the Panama Canal. The new-construction submarine Dorado (SS-248), under Lieutenant Commander Earle Caffrey Schneider (USNA ’33), was transiting to the Pacific via the Canal but failed to arrive on 14 October. The second attack by the Mariner was definitely U-214, confirmed in U-214’s log (the boat escaped). The Mariner had received incorrect coordinates for the restricted area associated with Dorado’s track. U-518 was also operating in the area but did not record being attacked. Therefore the Court of Inquiry and most accounts indicate Dorado was sunk by accident by the Mariner. However, of the three depth charges and one bomb dropped on the first submarine, none was seen to explode, so it was possible U-518 did realize she had been attacked. The description of the first submarine provided by the Mariner crew was very detailed and a much closer match to a U-boat than Dorado. In addition, unknown at the time, U-214 also laid a minefield, and it is possible Dorado hit one. Regardless, Dorado was lost with all 77 hands.

USS S-26

On the night of 24 January 1942, submarine chaser PC-460 was escorting four S-class submarines to commence defensive patrols on the Pacific side of the Canal Zone. When PC-460 broke off escort, three of the four submarines (including S-26) failed to get the signal of PC-460’s intent. In the darkness and confusion, PC-460 rammed and sank S-26. The commanding officer, executive officer, and a lookout on the bridge of S-26 survived, but the remaining crew of 47 was lost as S-26 quickly went down. Most accounts attribute this to an accident, but some state PC-460 mistook S-26 for a U-boat and deliberately rammed her. I have been unable to track down the origin of the “deliberate ram” report, but given that PC-460 attempted to back engines and turned to avoid the collision (not to mention this was on the Pacific side of the Canal), this is doubtful in my view as a “blue-on-blue” encounter.

April–July 1945: Minesweepers in the Last Amphibious Landings—Tarakan, Brunei, and Balikpapan

Unsung heroes of World War II were those who served on minesweepers, a critical component of almost every amphibious assault, and a very dangerous place to be. Although overshadowed in the history books by the kamikaze attacks of the Okinawa campaign, the last amphibious assaults of the war to recapture the island of Borneo from the Japanese proved to be particularly dangerous (and controversial). Seven U.S. minesweepers were lost during this campaign from April to July 1945, several of them to more sophisticated U.S. mines that had been offensively laid.

The strategic importance of Borneo was the oil fields, which had been a critical Japanese objective at the start of the war. Before the war, Japanese oil fields on Sakhalin Island and Formosa (both under Japanese control) could only meet about ten percent of Japanese needs. Before the war, most of Japan’s oil had come from the United States. When the U.S. government put an embargo on oil sales to Japan in response to Japanese aggression in China, Japan was faced with two unpalatable choices: Either give in to U.S. demands to withdraw from China, or go to war to take the oil they needed, of which the closest and best source was the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), especially Borneo. The Japanese chose the latter.

At the start of World War II, the very large island of Borneo was divided into smaller British protectorates (Sarawak, Brunei, and Labuan) on the northwest coast and an area, larger than the others, under Dutch colonial control. The Dutch territory included the oil fields at Tarakan and Balikpapan on the east side of the island. (Brunei also had an oil field.) There were some Dutch defensive minefields at Tarakan and Balikpapan, some of which the Japanese found and swept. The Japanese then laid defensive mines of their own. Once Borneo was within range, U.S. aircraft laid offensive minefields. With acoustic and magnetic influence mines, the U.S. minefields were more sophisticated and therefore more dangerous than the Japanese minefields.

On the British side, the Bay of Brunei served as a major Japanese fleet anchorage for much of the war, as the inlet was protected from submarines and initially stood out of range of Allied aircraft. Nearer the end of the war, the Bay of Brunei was further spared from Allied attack because the area was too close to the oilfields.

By the middle of 1944, U.S. submarines had sunk so many Japanese tankers that getting the oil to refineries in Japan became impractical. However, Tarakan crude oil could be burned in ships without being refined, and the Japanese were doing so. But Tarakan crude was also highly volatile and became a major factor in the loss of the carriers Taiho, Shokaku and Hiyo during the battle of the Philippine Sea.

Borneo was in Southwest Pacific Area of Operations, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur’s command. Recapturing Borneo was last on MacArthur’s agenda after operations to recapture most of the islands on the Philippines. The delay in taking Borneo was unfortunate, as about 2,000 Dutch, British, and Australian prisoners of war were starved, executed, or worked to death there in the last months of the war. Only six survived to the end.

Australia provided the ground troops for the Borneo landings, dubbed Operation Oboe. Most of the amphibious ships and gunfire support ships were U.S. vessels and subordinate to the U.S. Seventh Fleet, commanded by Admiral Thomas Kinkaid (promoted to four-star in April 1945) and the Seventh Fleet Amphibious Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Daniel Barbey (promoted to three-star in December 1944). In the course of the war, Barbey would plan and execute 58 amphibious assaults, 30 of them in 1945, along New Guinea’s north coast, the Philippine Islands, and finally Borneo. The first operation was against Tarakan, designated Oboe 1, and the Commander of the Tarakan Attack Group (TG 78.1) was Rear Admiral Forrest Betton Royal, with gunfire support provided by Rear Admiral Russell S. Berkey’s cruiser-destroyer group (TG 74.3).

The first move against Japanese-occupied Borneo was the capture of Tawi Tawi Island at the northeastern tip of Borneo, at the entrance to the Sulu Sea, on 2 April 1945. Prior to the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Tawi Tawi had been a major Japanese fleet anchorage because of its proximity to the Tarakan oil fields. However, the anchorage was relatively exposed, so U.S. submarines had a good view inside even from periscope, and the area was a favorite hunting ground for the U.S. subs. Harder (SS-257), under Commander Samuel D. Dealey, sank three Japanese destroyers and badly damaged another off Tawi Tawi with short-range, “down-the-throat” torpedo shots between 6 and 9 June 1944, for which he was awarded a Medal of Honor (see H-Gram 032/H-032-1.) As the Japanese had not built up any facilities on the island, the capture was relatively uneventful, but the area was heavily mined.

The first ship loss of the Borneo campaign occurred on 3 April 1943, when auxiliary motor minesweeper YMS-71 struck a mine and sank after her bow was blown off. (YMS-71 had been one of the many ships damaged when the ammunition ship Mount Hood [AE-11] spontaneously blew up at Seeadler Harbor on 10 November 1944 [see H-Gram 039/H-039-5]. YMS-71 was repaired, but her luck ran out at Tawi Tawi.) Two crewmen of the 32 aboard were missing and presumed dead.

Tarakan: Operation Oboe 1, April–May 1945

By the time the Japanese captured Tarakan on 11 January 1942, the Dutch had already engaged in a widespread sabotage effort against the oil production infrastructure. In retaliation, the Japanese executed between 80 and 100 Dutch and European civilians, which, however, left the Japanese without the key expertise necessary to get the fields operational again. They subsequently embarked about 1,000 petroleum engineers, technicians, scientists, and industrial experts on the Taiyo Maru to help in the Dutch East Indies oilfields, but the ship was torpedoed and sunk by the U.S. submarine Grenadier (SS-210) on 8 May 1942, and over 800 passengers drowned, a huge blow to Japan’s plan to fully exploit their newly conquered territories.

The hydrographic survey, minesweepers, and covering force arrived off Tarakan on 27 April 1945. The fast transport Cofer (APD-62, ex–DE-208), under Lieutenant Commander Herbert C. McClees, served as flagship and mothership for the minesweepers and underwater demolition teams. The covering force (TG 78.1) included the light cruisers Phoenix (CL-46), Boise (CL-47), and HMAS Hobart, along with five U.S. destroyers and one Australian destroyer.

On 30 April, the destroyers Philip (DD-498) and Jenkins (DD-447) were providing covering fire for a small Australian force setting up an artillery battery on a small offshore island. Despite operating in a previously swept channel, Jenkins struck a mine and suffered extensive hull damage. Her bow came to rest on the bottom. The crew contained the flooding, and she was floated off the next day, suffering only one killed and 14 wounded, but she had to withdraw from the operation for repairs.

On 1 May 1945, the Tarakan Attack Force (TG 78.1), with Rear Admiral Royal embarked in amphibious command ship Rocky Mount (AGC-3), arrived with a heavily reinforced Australian infantry brigade (about 18,000 personnel, counting support units including U.S. Navy beach party detachments). The brigade was embarked on two Australian personnel transports, one U.S. attack cargo ship, one U.S. landing ship dock (Rushmore, LSD-14), 13 LSTs, 12 LCIs, 4 LSMs and 12 LCTs, and was escorted by seven more U.S. destroyers, three Australian frigates, two U.S. destroyer escorts, and 21 PT-boats. The landings at Tarakan went very well under a very heavy naval bombardment, as the Japanese opted for their by-then standard tactic of defending inland and not at the beach. The primary objective of the landing at Tarakan was the airfield, so that it could be used to provide land-based air support to the subsequent Borneo landings. However, the airfield was so badly shot up that it was not operational until the war ended.

On 2 May 1945, a carefully concealed Japanese shore battery of two 75mm guns at Tarakan opened up and hit three of the minesweepers in quick succession. Auxiliary motor minesweeper YMS-481 sank, with a loss of six of her crewmen, and YMS-364 suffered significant damage. Cofer rescued 18 survivors and silenced the Japanese battery for the time being, but it continued to fire sporadically on U.S. ships until the destroyer escort Douglas A. Munro (DE-422) finally knocked it out for good on 23 May. (DE-422 was named for Signalman First Class Douglas A. Munro, USCG, the only Coast Guardsman to be awarded a Medal of Honor, posthumously, for his actions at Guadalcanal on 27 September 1942.)

Brunei Bay: Oboe 6, June 1945

The second major operation during the Borneo campaign was a series of landings by Australian forces at several locations in and near Brunei Bay. As Brunei had been a key Japanese fleet anchorage and training area prior to the Battle of Leyte Gulf, it was heavily mined. U.S. minesweepers had cleared parts of it as early at 22–29 April 1945. However, the landings were postponed to 10 June 1945. Once again, Rear Admiral Royal’s amphibious task group (TG 78.1) provided the lift for about 29,000 Australian troops, mostly Australians. Rear Admiral Berkey’s covering force (TG 74.3) provided gunfire support and was augmented by the addition of the light cruiser Nashville (CL-43), repaired after the severe kamikaze hit on 13 December 1944 that killed 133 of her crew (see H-Gram 040/H-040-2). General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was embarked in the light cruiser Boise to observe the landings.

The minesweeping force (Mine Division 34) arrived off Brunei on 7 June 1945, led by fast transport Cofer and including 12 YMS-type auxiliary motor minesweepers and five of the larger, AM-type ocean-going minesweepers. At about 1600 on 8 June 1945, minesweeper Salute (AM-294), commanded by Lieutenant Jesse R. Hodges, USNR, was clearing a field of moored contact mines when she struck one. The damage was severe. Her keel was probably broken, and she suffered nine men killed, most of them in the engine room. Casualties could have been worse, but based on hard lessons learned earlier in the war, all personnel who were not absolutely essential below decks were required to be topside (a lesson that explains why the frigate Samuel B. Roberts [FFG-58] suffered no deaths when she hit an Iranian mine while attempting to back out of a minefield, and her skipper had ordered everyone out from below the main deck). Nevertheless, Salute’s crew fought hard to save her, aided by two landing craft that came alongside. Cofer sent a medical officer and a repair party in four boats to try to save the ship. It was a valiant but futile effort, and by midnight the Salute had to be abandoned, as the flooding was out of control, and she broke in two. Cofer eventually brought aboard 59 survivors, of which 42 were wounded. Salute was awarded five Battle Stars for her World War II service.

The minesweeping operations in Brunei Bay continued after the loss of Salute and the landings on 10 June. By 12 June, the minesweeping force had cleared 102 mines. The next day, the force cleared 92 more. Including the earlier sweep operations, more than 500 mines were ultimately cleared from Brunei Bay, and Salute was the only Allied ship lost during the Brunei landings. Unfortunately, after the conclusion of the landings, Rear Admiral Royal suffered a heart attack and died aboard his flagship Rocky Mount.

Salute’s wreck is in shallow water, with the two halves of the ship on top of each other. It is a popular dive site, and over the years divers have made unauthorized recoveries of artifacts, some of which NHHC has obtained and conserved. In November 2016, U.S. Navy Divers of MDSU-1 and Brunei divers made a survey of the wreck from USNS Salvor (T-ARS-62).

Balikpapan: Oboe 2, June 1945

The landing at Balikpapan on the east coast of Borneo was the last major amphibious operation of World War II and was the most dangerous for the minesweepers. Balikpapan was also the site of one of the few U.S. Navy victories (the Battle of Makassar Strait) in the bleak first months of the war, when a squadron of four U.S. destroyers, under the command of Commander Paul H. Talbot, made a surprise night attack on 12 Japanese transports and their escorts, sinking four transports and one patrol boat (see H-Gram 003).

At Balikpapan, the U.S. minesweepers had to deal with old Dutch minefields, Japanese defensive minefields, and a large number of sophisticated, U.S. air-dropped acoustic and magnetic influence mines. Some of these mines had ship counters set as high as seven, meaning many ships (and minesweepers) could pass over them not knowing they were there, until finally a ship would trigger the mine. The Japanese had found and set some of these mines off, but not all of them. Ninety-three such influence mines had been air-dropped in the area, and none of them were set to deactivate. In addition, shallow water extended as much as six miles from the beaches, which forced the supporting naval gunfire support ships to stand off further than usual, adding to the vulnerability of the minesweepers.

Cofer and the minesweepers arrived off Balikpapan on 16 June in a force that initially included 16 YMS-type auxiliary motor minesweepers. As the extent and difficulty of the mine-clearing operation became apparent, this force would grow to three AM-type ocean minesweepers and 38 YMS.

On 17 June, ships of the covering force arrived and commenced 16 days of heavy shelling, the longest pre-invasion bombardment of the war, also accompanied by numerous air strikes. As the war seemed to be drawing to a close, there was great concern for minimizing the Australian casualties for an operation that some believed was not absolutely necessary for the defeat of Japan, as the Japanese forces there had been cut off for a long time, hence the protracted shelling and air strikes. Initial gunfire support was provided by the light cruisers Denver (CL-58) and Montpelier (CL-57) and four destroyers. By the date of the landings, 11 cruisers and 34 destroyers had fired 38,000 shells at the beach, and Allied aircraft had dropped over 3,000 tons of bombs. And just to make things more difficult for the minesweepers, three or four Allied planes inadvertently dropped bombs near minesweepers. As the minesweeping operations were progressing, underwater demolition teams destroyed over 300 yards of beach obstacles.

On 18 June, YMS-50 triggered a magnetic mine near her bow. The Japanese took the opportunity presented by the crippled YMS and opened fire with 75mm shore batteries. YMS-50’s keel was broken, and she could not be saved. Cofer rescued 23 survivors. After the vessel was abandoned, she somehow stayed afloat and began drifting toward the shore, so Denver (CL-58) sank her with gunfire. (On 14 February 1945, while covering operations in Mariveles Bay, on the Bataan Peninsula, Philippines, Denver had rescued Sailors blown off the destroyer La Valette [DD-448] when she was badly damaged by a mine and came close to sinking. Six of La Valette’s Sailors were killed and 23 wounded.)

On 19 June, YMS-339 and YMS-336 came under concerted shore fire, with 30 shells near-missing in the space of five minutes. When sweeping with gear in the water, the minesweepers were limited to about four knots, and when they came under fire, they would drop their gear so they could maneuver at higher speed and avoid being hit. This was certainly understandable, and the result was delays in clearing mines and lost minesweeping gear.

On 20 June 1945, YMS-368 was damaged by a mine. Then YMS-335 was hit by shore battery fire and suffered four men killed but did not sink. Then, on 22 June, YMS-10 was hit and damaged by shore fire. The following day, YMS-364 was hit by a shell that failed to detonate, and her crew manhandled it over the side. On 24 June, YMS-339 was damaged by a near miss from an Allied bomb, and the next day had a near miss from a Japanese bomb during the only air raid the Japanese were able to mount, by several G4M Betty bombers. One Japanese torpedo passed directly under Cofer without exploding, but the plane that dropped it was shot down.

Twenty-six June 1945 was the worst day for the minesweepers at Balikpapan, as YMS-39 and YMS-365 both set off mines and sank. YMS-39 triggered a U.S.-laid magnetic mine and partly disintegrated, capsized, and sank in less than one minute, suffering four killed. YMS-365, commanded by Lieutenant (j.g.) Frederick C. Huff, USNR, also triggered an influence mine and then hit a contact mine. Miraculously, no one aboard YMS-365 was killed, although 18 were wounded. After giving the abandon ship order, Lieutenant (j.g.) Huff was the last to leave before YMS-365 broke in two and began to sink—well, almost the last. After the crew of YMS-365 had been brought aboard YMS-364, the mascot dog of YMS-365, Doc, was seen to swim out of the wreckage and perch on the capsized hull. The survivors beseeched the commanding officer of YMS-364 to let them rescue the dog. After obtaining permission from the officer in tactical command, YMS-364 heaved to and crewmen from YMS-365 dove into the water and rescued Doc (who’d been aboard for over two years, and who lived happily ever after).

On 28 June 1945, YMS-47 was damaged by a mine and YMS-49 was hit by shore fire. By then, only 12 YMSs were still operational.

On 30 June 1945, the destroyer Smith (DD-378) was hit by shore battery fire. Three shells all passed through her No. 1 stack, though none of them exploded, and the damage was superficial. (During the Battle of Santa Cruz on 26 October 1942, a crippled Japanese torpedo-bomber had deliberately crashed into Smith just forward of the bridge in a devastating hit that killed 57 of her crew. Her skipper doused the raging fire by steering Smith into the wake of the battleship South Dakota [BB-57], all the while continuing to put up antiaircraft fire in defense of the carrier Enterprise [CV-6], for which the ship was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and the skipper a Navy Cross [see H-Gram 011/H-011-3]. Smith was repaired and earned six Battle Stars for her WW II service.)

The Balikpapan Attack Force (TG 78.2) was commanded by Rear Admiral Albert G. Noble, embarked in amphibious command ship Wasatch (AGC-9). TG 78.2 consisted of numerous transports, amphibious ships, and other vessels, screened by 10 destroyers, five destroyer escorts and one Australian frigate. The covering force was commanded by Rear Admiral Ralph Riggs and, was divided into three task groups, and included the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Shropshire and light cruiser HMAS Hobart, the Dutch light cruiser HMNLS Tromp, and the U.S. light cruisers Montpelier (CL-57), Denver (CL-58), Columbia (CL-56), Cleveland (CL-55), Phoenix (CL-46), and Nashville (CL-43), as well as 14 U.S. destroyers and one Australian destroyer. General MacArthur was embarked in Cleveland. In addition to aircraft flying from the Philippines, air support was provided by Task Group 78.4, which consisted of the escort carriers Suwannee (CVE-27), Block Island (CVE-106), and Gilbert Islands (CVE-107), a destroyer and five destroyer escorts.

On 1 July 1945, the first day of the invasion, about 10,000 men from the Australian 7th Division were put a shore—almost half of the 21,000-strong in the invasion force. Japanese resistance at the beach was fairly light, although fighting grew more intense inland. The Australians encountered about 100 tunnels and more than 8,000 land mines and booby traps that had to be cleared. Most opposition was overcome by the end of July, but mopping-up operations were still ongoing when the war ended.

The Borneo operations proved to be very controversial after the war, especially in Australia. About 625 Australians were killed in the three major operations, which many believed to have been a pointless loss of life. With the advantage of hindsight, knowing that the Japanese would surrender in August, this is arguably true. The Japanese on Borneo certainly could have been bypassed and left to “wither on the vine,” but unlike other islands in the Pacific, there was a significant civilian population on Borneo that would have suffered along with the Japanese. Had the Japanese not surrendered when they did, the argument about whether the operation was “worth it” might have been different. As to whether the sacrifice of the minesweepers was unnecessary, the mines would have had to be cleared sooner or later anyway and, frankly, it was the U.S. mines that did the most damage.

The mines at Balikpapan claimed one more minesweeper on 8 July 1945, when YMS-84 triggered an influence mine. YMS-367 attempted to take YMS-84 in tow, but the ship sank. Although 10 men were wounded, all 34 crewmen survived and were taken aboard Cofer which, fortunately, did not have to conduct another burial at sea.

The landing at Balikpapan cost four YMSs sunk, seven battle-damaged, eight minesweeper men killed, and 43 wounded, plus another 10 “stress cases” attributable to the constant strain uniquely associated with operating in a minefield. The relatively low number of casualties was attributable to the standard operating procedure of having no personnel below decks during minesweeping operations, but the casualties were sacrifices nonetheless in the closing moths of the war. For all the effort, only 18 U.S.-laid magnetic mines and nine Japanese moored contact mines were swept; but this was good enough, as the only ship losses were the minesweepers themselves. 21 of the YMSs that were at Balikpapan from the early days of the operation were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

24 July 1945: USS Underhill (DE-682)—the Last U.S. Destroyer Escort Lost

Commencing on 14 July 1945, the Japanese launched their final naval offensive of the war, as six boats of Submarine Division 15 departed Japan on the ninth (and last) Kaiten mission. Designated the “Tamon” Group, the six submarines, I-47, I-53, I-58, I-363, I-366, and I-367, each embarked six Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes. Message traffic on the sortie was intercepted by U.S. radio intelligence and reported by Fleet Radio Unit Melbourne on 14 July: “Four subs have been ordered to carry out reconnaissance and offensive operations against Allied shipping. The first, I-53, leaves Bungo Suido on 14th to patrol halfway between Okinawa and Leyte Gulf.” The intelligence report was accurate but for the number of boats: It was six submarines, not four.

I-58 departed four days after I-53, and the others followed in the next days. With the exception of the first Kaiten mission, which sank the U.S. oiler Mississinewa (AO-59) at Ulithi Atoll on 20 November 1944 (see H-Gram 039/H-039-4), the previous eight Kaiten missions had been completely fruitless for the loss of eight mother submarines.

I-53 was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Saichi Oba and was a relatively new (commissioned in February 1944) C-3–class long-range cruising submarine. (Her sister, I-52, was sunk in the Atlantic near the Cape Verdi Islands on a “Yanagi Mission” to Germany on 23 June 1944 [see H-Gram 033/H-033-1]. In late August 1944, I-53 had been converted to carry four Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes. After two unsuccessful Kaiten missions, she was modified again in April 1945 to carry two more Kaitens (six total). Each Kaiten had a 3,400-pound warhead and one pilot to guide it on its one-way mission (once launched, a Kaiten could not be recovered). Departing Otsujima on 14 July 1945, I-53 arrived in her assigned operating area—about 260 nautical miles east-northeast of the Cape Engano lighthouse on Luzon, Philippines, on the U.S. convoy track from Okinawa to Leyte—on 22 July 1945. While operating submerged on 24 July, I-53 sighted a southbound convoy.

Task Unit 99.1.18 was three days out from Okinawa and included six LSTs (LST-647, -768, -769, -991, and two others) transporting the battle-scarred U.S. Army 96th Infantry Division to Leyte following three months of heavy fighting on Okinawa. The convoy also included the stores ships USS Adria (AF-30, misidentified in many accounts as a “troopship” or “merchant ship”). The convoy was escorted by the destroyer escort Underhill (DE-682), patrol escort ship PCE-872, four patrol craft (PC-1251, -803, -804, and -807), and two submarine chasers (SC-1306 and SC-1309.)

USS Underhill was a Buckley-class destroyer escort armed with three single 3-inch guns, anti-aircraft weapons of various calibers, three 21-inch torpedo tubes, one hedgehog launcher, two depth charge racks, and eight side-throwing K-gun depth charge projectors. Underhill was commissioned 15 November 1943 and had previously served on convoy escort duty in the Atlantic and Mediterranean until commencing Pacific service in March 1945. She was named for Ensign Samuel Jackson Underhill, a naval aviator lost during the Battle of the Coral Sea on 8 May 1942 and awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. An SBD Dauntless pilot in Scouting Five (VS-5), Underhill had participated in the sinking of the Japanese light carrier Shoho on 7 May 1942. He was one of eight VS-5 SBDs held back from the strike on the Japanese carrier Shokaku in order to provide ASW patrol in defense of the carrier Yorktown (CV-5) when the main Japanese air strike came in. The SBDs courageously engaged the Japanese bombers and fighters, but four of the SBDs, including Underhill’s, were shot down. Underhill was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Robert Maston Newcomb, USNR, who had been with the ship since her commissioning—first as executive officer and then as commanding officer. Underhill was not supposed to be the escort for this convoy but had replaced another ship that had mechanical problems.

Earlier in the morning on 24 July 1945, one of the submarine chasers broke down and had to be taken in tow by PCE-872. About the same time, between 0900 and 1000, a Japanese aircraft (reportedly a Ki-46 Dinah twin-engine high-speed reconnaissance aircraft) observed the convoy but never got closer than ten miles. Some accounts state the Dinah was reporting the convoy’s movements to I-53, but Japanese records show I-53 did not receive any such support, which would have been unusual from an army aircraft anyway.

As the largest and most capable escort, Underhill was steaming ahead of the convoy. At about 1415 on 24 July, she sighted an object ahead, assessed it to be a floating mine, and gave orders for the convoy to execute a 45-degree turn to port to avoid the hazard. At the same time, Underhill engaged the object with 20mm and rifle fire. (Some accounts indicate that this mine, if that is what it was, had been laid by I-53 to divert attention, but I-53 did not carry mines, so this is unlikely.) Nevertheless, as Underhill was shooting at the object, her sonar made contact on a possible submarine. She directed PC-804 to investigate the contact.

Exactly what happened next varies in different accounts. According to Japanese records, I-53 launched Kaiten No. 1 at 1425. Other accounts claim a second (or even third) Kaiten might have been launched. At 1451, PC-804 conducted a depth charge attack that brought the submarine to periscope depth. Underhill attempted to ram the boat, but it dove, and at 1453 Underhill dropped a 13 depth charge pattern, which produced oily, debris-filled water. Lieutenant Commander Newcomb believed they had sunk a small submarine. He had just announced the news to his crew when PC-804 sighted another periscope. At some point, according to the Japanese, Kaiten No. 1 passed under PC-804 and then surfaced near Underhill, which went to flank speed and attempted to ram the Kaiten’s port side. According to U.S. accounts, lookouts sighted periscopes of two more submarines heading for Underhill, one on each side. One of these might have passed underneath LST-991 without exploding. The one to starboard of Underhill was reportedly too close to bring guns to bear, and Underhill rammed the one to port.

Whether there was one Kaiten or two, what is certain is that at 1507 two massive explosions in quick succession obliterated everything forward of the stack on Underhill. The blasts were due to some combination of Kaiten warhead(s) and a magazine or boiler explosion. The bridge, mast, and forward guns were blown clear off the ship, and other parts of the ship flew 1,000 feet into the air. All hands in the forward half of the ship, including the commanding officer, were killed, as that part of the ship went down almost instantly. There were casualties in the aft half, too, but the cascade of water from the huge explosions doused the flames, although it also washed many men overboard. The aft half of the ship remained afloat and upright for several hours.

Ten of the ship’s 14 officers were killed, leaving Lieutenant (j.g.) Elwood M. Rich as the senior survivor. PC-803 brought a surgeon from LST-749, the flagship of LST Group 46, while other PCs searched for survivors in the water—a search that was repeatedly disrupted by continued periscope sightings, probably imaginary, as I-53 made its getaway and subsequently reported sinking a large transport. PC-803 and -804 took 116 survivors off the aft end of the ship at 1800 before being ordered to sink it with 3-inch and 40mm gunfire. Several other survivors were fished out of the water. Numbers vary in different accounts, but 112 (or 113, or 119) of Underhill’s crew of 238 (or 236) died. According to Samuel Eliot Morison, there is no indication that a submarine alert was sent out to the fleet about the loss of Underhill, which would factor into the fate of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35) on 29 July 1945.

Lieutenant Commander Newcomb was awarded a posthumous Silver Star for his actions in the moments before the sinking. However, it wasn’t until 55 years later that Secretary of the Navy Richard Danzig approved the award of a Navy Unit Commendation for Underhill in 1998, at the instigation of Missouri Senator Kit Bond, who was convinced that Underhill’s valor and sacrifice in defense of the convoy had not been adequately recognized at the time. Also in 1998, a belated Bronze Star with Combat V was awarded to Chief Boatswain’s Mate Stanley Dace (posthumously). Dace had been instrumental in the survival of many men in the aft end of the ship and was the last man off. (An episode of the television show JAG featured a fictitious ship, the USS Stanley Dace.) Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Joseph Manory, who had kept many of the survivors alive, was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal with Combat V in 1998.

Although it can be argued that ramming what was essentially a big torpedo was not a good idea, Lieutenant Commander Newcomb had little choice under the tactical situation but to do what he did in order to protect the convoy. But for the sacrifice of Underhill, many Army soldiers aboard the slow and vulnerable LSTs might have been lost to additional Kaiten attacks from I-53. Although the following Navy Unit Commendation citation from 1998 contains a number of historical inaccuracies, it does accurately reflect the valor of Underhill and her crew.

The Secretary of the Navy takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Unit Commendation to USS Underhill (DE 682) for exceptionally meritorious service as lead ship in a convoy from Okinawa to the Philippines on 24 July 1945. As the senior ship assigned to escort seven tank landing ships and a merchant vessel carrying the battle-weary soldiers of the 96th Division, Underhill performed her duties in an outstanding and heroic manner. Detecting an unidentified object in waters ahead of the convoy, she redirected the convoy to avoid the peril. As she proceeded to attempt to sink the object without success, her sonar detected further contacts and together with assigned submarine chasers began prosecuting several contacts. Successfully identifying and depth-charging the first of the Kaitens, Japanese midget suicide submarines, she proceeded to ram the next two in order to protect the convoy. The subsequent ramming caused two violent explosions that severed the vessel in half, sinking her and killing 113 of her men. With the enemy threat eliminated, the convoy continued safely on to the Philippines as planned. By their truly distinctive performance, self-sacrifice, and loyal devotion to duty, the officers and enlisted personnel of the USS Underhill (DE 682) reflected great credit upon themselves and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

A report on the sinking of the Underhill filed by LST-647 on 18 October 1945 led with the following paragraph: “Peace-loving people throughout the world today are grateful to those who have given their lives to further the cause of freedom and democracy. But to the men whose very lives have been saved by the heroic deeds of their fighting comrades, this gratitude assumes the strength of an unpayable personal debt. Everlasting are the vivid memories of thousands of us who have seen our comrades sacrifice their lives so that we may live. If only the entire world could feel the same personal indebtedness toward those heroes, it would be a great impetus toward attaining the free and peaceful world for which these men were fighting. The attainment of this goal can be our only reasonable tribute.” Hard to argue with that.

However, I-53 wasn’t finished yet. On 27 July 1945, I-53 sighted another 10-ship, southbound convoy. Lieutenant Commander Oba initially assessed that the convoy was too far away to attack, but one of the Kaiten pilots beseeched Oba for the opportunity to make a long-range Kaiten attack. I-53 launched Kaiten No. 2. Although a large explosion was heard an hour later, it was most likely the Kaiten self-destructing, as no ships in the convoy were hit.

On 7 August 1945, one day after the Hiroshima atomic blast, I-53 sighted another southbound, Okinawa-to-Leyte LST convoy and commenced a submerged night approach. However, at 0023, I-53 was counter-detected by sonar on the destroyer escort Earl V. Johnson (DE-702), commanded by Lieutenant Commander Jules James Jordy, USNR (USNA ‘35). (Like Underhill, Earl V. Johnson had been named for a VS-5 SBD Dauntless dive-bomber pilot who earned a posthumous Navy Cross by engaging Japanese fighters escorting the strike on the carrier Yorktown during the Battle of the Coral Sea on 8 May 1942.) Earl V. Johnson dropped 14 depth charges on the contact and then lost sonar contact. Contact was regained, and Earl V. Johnson conducted a second depth charge attack at 0055 and then a third depth charge attack at 0212. Patrol escort ship PCE-849 then fired a hedgehog salvo at the contact. I-53 survived all the attacks but suffered significant damage, with several batteries, the rudder engine, and all the lights knocked out.

At 0230, I-53 launched her No. 5 Kaiten from a depth of 130 feet, and 20 minutes later I-53 heard a large explosion. Meanwhile, lookouts on Earl V. Johnson sighted one torpedo approaching at 0235 and two more at 0245, one of which passed directly under Earl V. Johnson’s keel before exploding on the far side at 0246. At 0256, PCE-849 made another hedgehog attack on I-53, without success, as Earl V. Johnson subsequently regained sonar contact on the elusive sub.

At 0300, I-53 launched her No. 3 Kaiten and heard another heavy explosion at 0332. Her remaining two Kaitens had mechanical problems and could not be launched. At 0326, Earl V. Johnson conducted yet another depth charge attack on a sonar contact, which resulted in a large explosion and a white puff of smoke, and the force of the explosion caused slight damage to Earl V. Johnson. This explosion might have been Kaiten No. 3. At this point Lieutenant Commander Jordy reported sinking a submarine and re-joined the convoy.

On 12 August, I-53 returned to Otsujima, Japan, and offloaded two Kaitens. This would suggest that only one Kaiten was involved in the attack on Underhill and that reports of two or more Kaitens involved are the result of jittery and traumatized lookouts and the “fog of war.” I-53 was surrendered at the end of the war and scuttled by gunfire from the submarine tender Nereus (AS-17) on 1 April 1946 as part of Operation Road’s End.

Of the other Kaiten mother submarines in the Tamon Group, I-47 ran into a typhoon that ripped off one of her Kaitens, and I-47 returned to port. I-366 attacked a U.S. convoy north of Palau, and two Kaitens were defective and failed to launch. Three others that were launched probably ran out of fuel before reaching the convoy, and no U.S. ships were hit. I-366 was scuttled as part of Operation Road’s End. I-367 had no success at all and after the war was also scuttled in the same operation. I-363 was the last to depart Japan, on 8 August, and was subsequently diverted to the Sea of Japan to guard against a Soviet attack, as the Soviets had entered the war in the Pacific on 9 August. I-363 was then strafed by U.S. carrier aircraft, with two Japanese crewmembers killed. Although I-363 survived the war, on 29 October 1945, while transiting from Kure to Sasebo, she struck a leftover mine and sank. Ten crewmen were rescued, but the commanding officer and 35 others were lost. I-58 would meet destiny and the heavy cruiser Indianapolis in the middle of the Philippine Sea on 29 July 1945.

29 July 1945: USS Callaghan (DD-792)—the Last U.S. Destroyer Lost

There had been a lull in kamikaze attacks around Okinawa following mass kamikaze attack Kikusui No. 10 (see H-Gram 049) and the end of organized Japanese resistance on the island on 22 June 1945. With Okinawa a lost cause, the commander of the Japanese kamikaze operations, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, was saving most of his remaining aircraft and pilots for the final defense of the Japanese Home Islands.

The lull was broken on the night of 28–29 July 1945 when five volunteer petty officer pilots of the Special Attack Corps 3rd Ryuko (Flying Tiger) squadron took off under a bright, third-quarter moon on a one-way mission from Miyakojima, an airfield formerly used for training on an island midway between Okinawa and Formosa (the flights had originated on Formosa). The pilots were flying navy Yokosuka K5Y Willow two-seat biplane trainers, known to the Japanese as Akatombo “Red Dragonflies” (they were painted a bright orange-red) and to the Allies as “Willows.” The Willows had a maximum speed of about 120 knots and cruised at about 90 knots. Each of the Willows launched that night carried one 220-pound bomb. (These were not “float planes” or “seaplanes” as described in some accounts.)

By 29 July 1945, the number of radar picket stations around Okinawa had been reduced to two because of a lack of Japanese air activity. At Radar Picket Station 9A were three destroyers and three LCSs. The Fletcher-class destroyer Callaghan (DD-792), under Commander Charles M. Bertholf (USNA ’34), had the commander of Destroyer Division Five (DESDIV 55), Captain Albert. E. Jarrell (USNA ’25), embarked and was due to be relieved on station in two hours by the destroyer Laws (DD-558) in order to commence a return to the U.S. West Coast for refit. Cruising in formation ahead and behind Callaghan were the Fletcher-class destroyers Pritchett (DD-561), under Commander Cecil Caulfield, and Cassin Young (DD-793), under Commander John W. Ailes III (USNA ’30). The three LCSs (LCS-125, -129, and -130) were veteran “pallbearers” on station to provide additional antiaircraft support and, probably more importantly, firefighting and rescue services.

By coincidence, Callaghan and Cassin Young were both named for officers killed aboard the heavy cruiser San Francisco (CA-38) during the bloody nighttime melee off Guadalcanal on Friday, the 13th of November 1942. Rear Admiral Daniel Callaghan was in command of the U.S. cruiser-destroyer force that engaged two Japanese battleships and escorts, while Captain Cassin Young was in command of Rear Admiral Callaghan’s flagship San Francisco. Following the battle, during which Callaghan’s force accomplished its mission of preventing a battleship bombardment of the U.S. Marines on Guadalcanal, at an extremely high cost, Callaghan was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. Captain Young, who had been awarded a Medal of Honor in command of the repair ship Vestal (AR-4) during the attack on Pearl Harbor, was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross (See H-grams 001 and 012). Pritchett was named for a Navy officer in the Civil War who had fought off a superior Confederate force while in command of the gunboat USS Tyler during the Battle of Helena, Arkansas (an unsuccessful Confederate attempt to relieve the siege of Vicksburg) on 4 July 1863.

At 0028 on 29 July, a low, slow aircraft was detected on radar at 13 nautical miles, closing the force at 90 knots. The destroyers shortly thereafter opened fire with their main battery guns, but the radar-proximity–fused 5-inch shells proved ineffective against the mostly fabric and wood aircraft. An intense barrage of 40mm fire and an additional barrage of 20mm fire also failed to stop the biplane as it commenced a kamikaze run at about 2,000 yards. The Willow passed between Pritchett and Callaghan before crashing into the main deck of Callaghan on the starboard side at 0041. The flimsy plane itself didn’t do that much damage, but the bomb penetrated into the aft engine room and detonated four minutes later, decimating the damage-control teams that had responded to the fire started by the crashed aircraft.

The fire amidships raged out of control and spread to Callaghan’s No. 3 5-inch gun upper-handling room, resulting in the successive detonations of 75 5-inch rounds. The explosions caused severe hull damage and flooding. Exploding ready-use 40mm and 20mm ammunition cut down even more of Callaghan’s crew as they bravely but vainly tried to control the fire and flooding. Within minutes, the fantail was underwater and the ship was developing a 15-degree list.

Commander Berthold called for assistance from LCS-130, which came alongside at 0110 to help fight the fire and take aboard wounded, having picked up 27 men who had been blown overboard (31 total, eventually). The commanding officer of LCS-130, Lieutenant William H. File Jr., was awarded a Silver Star for his actions that night, including shooting down another Willow that attacked at 0145. LCS-125 and -129 also came alongside, first to help fight the fires and then to evacuate the crew.

Berthold ordered all but a few key men off the ship to continue to try to save her, but it was beyond hope. At 0153, he and Jarrell boarded the LCS. Callaghan went down by the stern at 0235 followed by a large underwater explosion. Callaghan suffered 47 dead and 73 wounded. She was the last U.S. ship sunk by a kamikaze, the last destroyer lost in the war, and the last of 14 U.S. destroyers lost near Okinawa.

Meanwhile, the fire on Callaghan served as a beacon for the other Willows, which circled for a while before attacking. These aircraft may also have been guided by a G4M Betty bomber, one of which was reported shot down by a U.S. night fighter. One Willow made a run on Cassin Young and was shot down at 0047. Another attacked Pritchett at 0143. Despite being hit multiple times, the Willow came very close to Pritchett when it crashed six feet from her port side. (Pritchett had survived and been repaired after being hit on the fantail by a 500-pound bomb on 3 April 1945.) The Willow’s bomb detonated close aboard, dishing in Pritchett’s hull plating, also causing significant damage to the portside superstructure, damage control racks, and radio power leads. Two crewmen were killed. Despite the damage, Pritchett continued to stand by Callaghan for two hours while Cassin Young guarded against further attack. Following the sinking of Callaghan, the LCSs and Pritchett transferred the survivors to Cassin Young, which took them into the Hagushi Anchorage, while Pritchett went to Kerama Retto for repair. Pritchett was awarded a Navy Unit Commendation for her service at Okinawa.

Damage to Pritchett’s stern on 29 July 1945. While rescuing survivors from Callaghan, which had just sunk as a result of being hit by a kamikaze, Pritchett was also attacked by a kamikaze. It was shot down but exploded six feet off Pritchett’s port quarter, killing two men and seriously wounding another (NH 69894).

Commander Bertholf was awarded a Navy Cross for actions by Callaghan earlier in the Okinawa campaign:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander Charles Marriner Bertholf, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as commanding officer of destroyer USS Callaghan (DD-792), from 25 March to 29 June 1945 in the vicinity of Okinawa. During this period of almost continuous action Commander Bertholf repeatedly placed his ship, with coolness and excellent judgment, and in spite of attacks from enemy planes, suicide boats, submarines and shore batteries, in a position where it could be employed most effectively against the enemy. His ship was individually responsible for the destruction of one midget submarine and six enemy aircraft, and assisted in the destruction of many others, while continuing to provide fire support to our forces ashore and protection to important units of the fleet which materially contributed to the success of our operations against the enemy. His determination, professional skill and heroic conduct were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Captain Jarrell was also awarded a Navy Cross for actions of DESDIV 55 earlier in the Okinawa campaign.

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain Albert Edmonson Jarrell, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as commander of a Destroyer Squadron and of the screen of detached groups which served as Gunfire and Covering Force, in action against enemy Japanese forces on Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands, from March to May 1945. Alert to constant danger of enemy aerial attack and aggressively maintaining the officers and men of his command at the highest peak of efficiency during prolonged and hazardous naval operations, Captain Jarrell skillfully directed the ships of his command in bringing effective gunfire to bear upon hostile aggressors in this area. Instantly assuming command of rescue and salvage operations when two destroyers were severely damaged in the intense aerial attack of 6 April 1945, he contributed to the saving of many lives and to the safe return of both crippled vessels. His unfaltering decision, cool judgment, and resolute fortitude in the face of continual peril reflect the highest credit upon Captain Jarrell and the United States Naval Service.

Yet the Willows were not finished yet. On the night of 29–30 July, three more Willows launched from Miyakojima en route to Okinawa. One Willow made it into the Hagushi anchorage on the southwest side of Okinawa and almost hit the high-speed transport Horace A. Bass (APD-124), commanded by Lieutenant Commander Frederick W. Kuhn. Horace A. Bass had shot down a Japanese kamikaze off Okinawa during the mass attack on 6 April 1944. While escorting a 17-ship convoy from Guam to Okinawa on 25 April 1945, she sank a Japanese submarine, probably RO-109, despite the submarine attempting to jam Horace A. Bass’s sonar and using every evasive trick in the book. However, at about 0230 on 30 July 1945, luck ran out for one Horace A. Bass Sailor (I’ve tried to find his name, without luck). Although there was radar warning that a plane was inbound, no lookouts sighted the low, slow aircraft until it was too late, and none of the ships engaged the plane. The Willow struck a glancing blow on the top of the superstructure, wrecking boat davits and life rafts and carrying away signal flags and halyards before crashing on the far side. The Willow’s 220-pound bomb also missed, detonating close aboard and spraying the ship with shrapnel, killing one and wounding 15. The damage was not enough to require immediate repair, so Horace A. Bass continued operations around Okinawa. After the war, Horace A. Bass embarked the “prize crew” that then took possession of the Japanese battleship Nagato, and she would later play an important role in the Inchon landings during the Korean War in September 1950.

The destroyer Cassin Young’s luck ran out an hour after Horace A. Bass was damaged. Cassin Young had had two previous brushes: On 12 April 1945, she shot down five kamikazes before a sixth hit her foremast, causing the plane to explode in midair about 50 feet above the deck, showering the ship with fragments and flaming gasoline that wounded 50 crewmen, many seriously, but killed only one. The previous night, 28–29 July, Cassin Young had shot down a Willow, assisted in shooting down another, and picked up Callaghan’s survivors, all without being damaged.

On the night of 29–30 July, Cassin Young had been assigned to screen the entrance to Nakagusuku Bay on the southeast side of Okinawa. At about 0325, two Willows approached. One was shot down (Cassin Young’s after action report indicated that, unlike more modern Japanese aircraft, the Willow didn’t catch fire when hit and most shells passed clean through). The second Willow attacked Cassin Young from astern and flew alongside to starboard before hitting the aft boat davit and crashing into the ship, starting a serious fire. The bomb exploded in the fire-control room and knocked out radars, radios and communications with the forward fireroom. Despite extensive damage, the crew regained control by 0345 after jettisoning torpedoes and 40mm ammunition. Although the starboard shaft was locked up, the ship got underway to Kerama Retto for repair. Among the 22 dead was the prospective commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Alfred Brunson Wallace (USNA ’39), who had been aboard for three days. The commanding officer, Commander Ailes, was among the 42 wounded. Cassin Young was awarded a Navy Unit Commendation for Okinawa operations.

Commander Ailes was awarded a Silver Star as commanding officer of Cassin Young on 29 July 1945, and a Navy Cross as commanding officer of Cassin Young for previous operations around Okinawa:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander John William Ailes III, United States Navy, for extraordinary professionalism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as commanding officer of destroyer USS Cassin Young (DD-793), during air-surface action in the vicinity of Okinawa Jima, on 12 April 1945. While on radar picket station, Commander Ailes skillfully and courageously handled his ship during an attack by five enemy planes, destroying all enemy planes and keeping damage to his ship to a minimum. His ship was able to proceed to a friendly base, under its own power, after the action. His skill and courage were at all times in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Commander Ailes continued to serve and retired as a rear admiral in the mid-1960s.

30 July 1945: USS Indianapolis (CA-35)—the Last U.S. Cruiser Lost

On 14 July 1945, Fleet Radio Unit Pacific (FRUPAC), decoded Japanese message traffic revealing the departure of submarine I-53 that day. I-53 would sink destroyer escort Underhill (DE-682) with a Kaiten manned suicide torpedo on 24 July. The “Ultra” message also revealed that another boat, I-58, would depart on 18 July for an operating area 500 nautical miles north of what was assessed to be Palau. According to the intercept, I-47 and I-367 would depart on 19 July to operate on the Okinawa-Marianas transit route. An additional intercept on 19 July confirmed I-58’s departure.

On 16 July, with her repairs complete following the kamikaze hit off Okinawa on 31 March 1945 (see H-Gram 044/H-044-2), the heavy cruiser Indianapolis departed Mare Island, California, on a mission with top secret cargo, with orders to proceed to Tinian via Pearl Harbor at fastest possible speed. Neither the commanding officer nor any of the crew knew what the cargo was; components of the first atomic bomb, which would be dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 (I will cover the U.S. Navy’s role in the atomic bomb in more detail in the next H-gram). By this time of the war, Indianapolis had earned ten Battle Stars and, for much of the war, had served as the flagship for Admiral Raymond Spruance for the U.S. Navy’s advance across the central Pacific—Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, Western Carolines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa—with credit for downing nine Japanese aircraft, destroying the supply ship Akagane Maru in the Aleutians, and for numerous shore bombardments in support of U.S. Marines and Army fighting ashore.

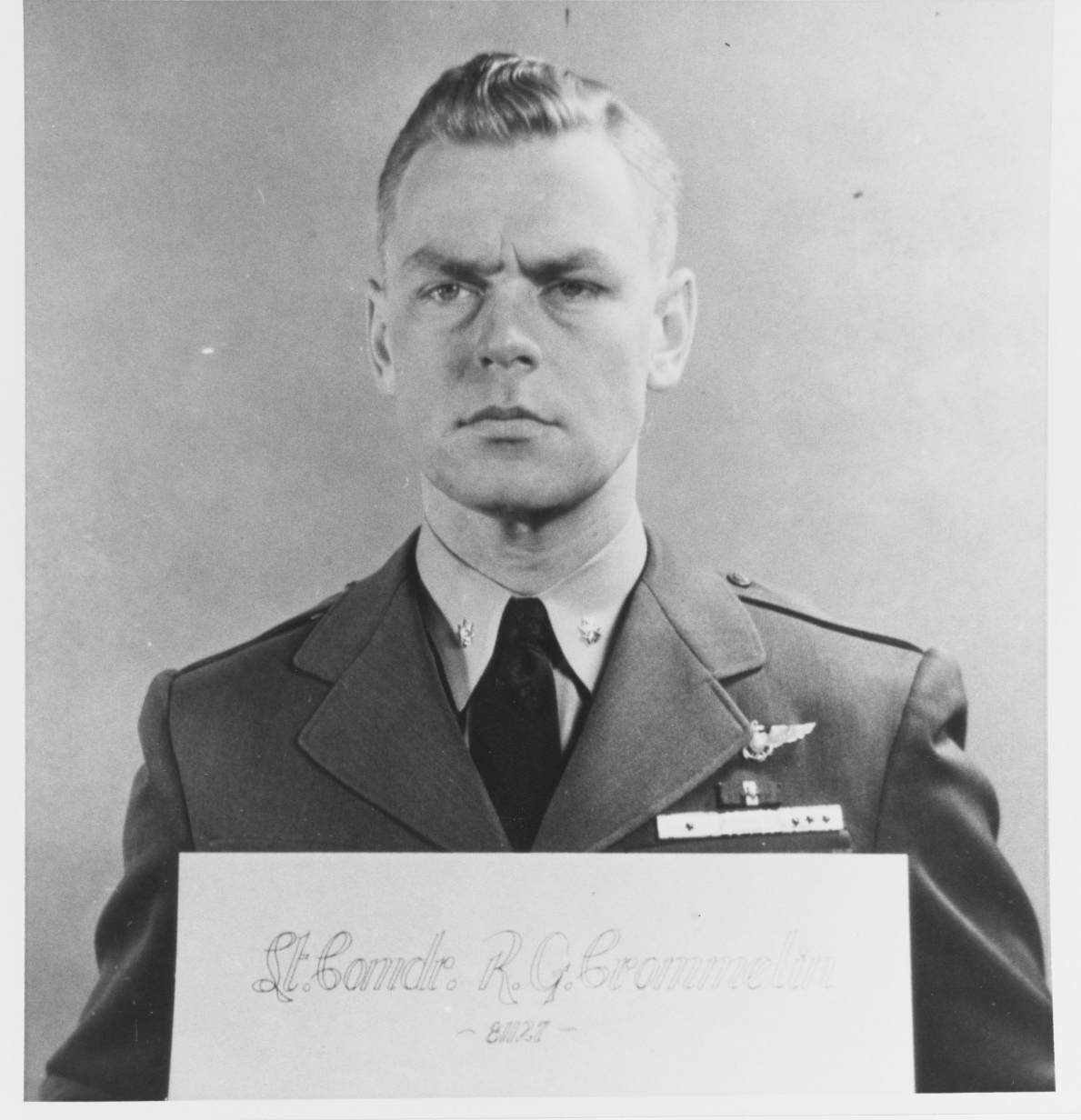

The commanding officer of Indianapolis, Captain Charles Butler McVay III (USNA ’20), was a highly regarded, fast-track officer, and son of a four-star admiral, Charles B. McKay, Jr. (USNA ’90), who had been commander of the Asiatic Fleet in the early 1930s. Although many of Indianapolis’ crewmen were battle-hardened veterans, 250 of her crew were going to sea for the first time, and the special mission prevented Indianapolis from conducting a planned two-month training period.

As predicted by U.S. Pacific Fleet Intelligence,.Japanese submarine I-58, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, sortied from Japan on 18 July as part of the Tamon Kaiten group. I-58 was a relatively new submarine, commissioned on 7 September 1944, with the capability to carry and launch a seaplane, although she never did. She was originally modified to carry four Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes, but in May 1945 had been further modified to carry six. The sumarine had conducted three Kaiten missions with no luck, although Japanese reports claimed she sank an escort carrier and a large oiler. She had served as a radio relay for a daring Japanese suicide air mission to the U.S. Navy fleet anchorage at Ulithi Atoll on 10 March 1945 (Operation Tan 2), when only six of 24 P1Y Frances bombers reached Ulithi and one crashed into the carrier Randolph (CV-15), at anchor, killing 25 U.S. sailors and wounding 106 more.

Hashimoto, a 1931 graduate of the Japanese naval academy at Etajima, had been in command of I-58 since her commissioning. During the attack on Pearl Harbor, he was serving on I-24, which had launched one of the five midget submarines intended to penetrate Pearl Harbor. (The midget launched by I-24 missed the harbor and ran aground. Its pilot, Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, was the only one of 10 midget submarine crewmen to survive and became the first Japanese prisoner of war of the United States.) Despite his frustration with lack of success, Hashimoto identified a possible target as a hospital ship (correctly) on 25 April 1945 and let it pass, only to be depth-charged by three U.S. destroyers the next day.

On 19 July, Indianapolis arrived at Pearl Harbor in a record time of 74.5 hours on her unescorted transit. She was given first-priority entry and exit for a short stop to refuel and drop off passengers, before resuming her high-speed unescorted transit to Tinian. (The previous record of 75.4 hours had been set by light cruiser Omaha [CL-4] in 1932.)

On 22 July, FRUPAC intercepted another Japanese message adding two more submarines (I-363, I-366) to the Tamon Group and reiterating I-58’s vague operating area.

On the morning of 26 July, Indianapolis arrived at Tinian and offloaded her top secret cargo. She then steamed to Guam, arriving on the morning of 27 July.

On 27 July, intercepted Japanese message traffic was assessed to indicate that I-58 had been sunk. This may have been RO-47, but certainly was not I-58, because I-58 arrived in a position on the Guam-Leyte transit route (Route Peddie) on 27 July, about 250 nautical miles south of the position identified in the previous Ultra intercept—unbeknownst to U.S. naval intelligence.

During the brief stop in Guam on 27 July, Captain McVay received routing instructions and an intelligence brief. The brief did not include Ultra intelligence, as distribution was tightly held (it also wouldn’t have been very useful, as the closest submarine to his intended track—I-58, 200–300 nautical miles off track—had been incorrectly assessed as sunk). Nor was McVay informed of the sinking of Underhill on 24 July, but that was about 600 nautical miles off his intended track. The intelligence report did include three possible submarine sightings (one on 22 July and two on 25 July) along his track (However, none of these was valid as I-58 wasn’t there yet and the reports were not high confidence).

Nevertheless, despite the appearance of a low submarine threat, McVay requested an escort as Indianapolis had no sonar or other ASW capability other then radar, eyeballs, and guns. He was informed that no escort ships were available. Having just made an unescorted transit from the West Coast (and having made previous unescorted transits between Guam and Okinawa), this was not considered to be a show stopper. McVay was also trying to balance two opposite requirements: a desire to minimize further unnecessary wear on his engines after the high speed transit, and a desire to get to Leyte as soon as possible for anti-aircraft training that his crew desperately needed before going into battle for the invasion of Japan. Indianapolis departed Guam on the morning of 28 July, bound for Leyte, Philippines.

At about 1400 on 28 July 1945, I-58 sighted a “large tanker escorted by a destroyer,” about 300 nautical miles north of Palau. The tanker was actually the armed cargo ship SS Wild Hunter, commanded by Lieutenant Bruce Maxwell, USNR, and the destroyer was destroyer escort Albert T Harris (DE-447), under the command of Lieutenant Commander Sidney King. At 1629, lookouts on Wild Hunter sighted a periscope at 3,000 yards on the port beam, which quickly submerged. Eleven minutes later, a periscope appeared directly astern. Wild Hunter’s gunners hit it with their first shot from a 3-inch gun. The cargo ship also transmitted two messages reporting the action.

Albert T. Harris had been about 14 miles from Wild Hunter when the action commenced. The destroyer escort subsequently gained sonar contact at about 1810, and conducted four hedgehog attacks at 1842, 1852, 1930, and 1947. Albert T. Harris’ contact and attack report was transmitted and rebroadcast by the Philippine Sea Frontier to all ships. Albert T. Harris regained contact later in the evening and conducted another hedgehog attack at 2026, and again at 2150, ultimately 10 total. (It would turn out that the gyro for the hedgehog launcher was off and every attack was 10 degrees off target.) Early the next morning, destroyer-transport Greene (APD-36) arrived to join in the search, making at least two depth charge attacks with no result.

Upon sighting and closing on Wild Hunter, I-58 had launched Kaiten No. 2, followed about 12 minutes later by Kaiten No. 1. I-58 recorded two explosions, but due to rain squalls could not assess the results of the attack. Regardless, both Kaiten were lost without hitting anything and I-58 got away.

The submarine received orders addressed to all the Tamon boats to head toward the Okinawa-Leyte transit route, but, as Lieutenant Commander Hashimoto was already well south in the Philippine Sea, he improvised and headed first for the intersection of the Guam-Leyte route (Peddie Route) and the Palau-Okinawa route.

Multiple reports of the submarine actions from Albert T. Harris reached the combat information center and bridge watch of Indianapolis, although they apparently did not reach Captain McVay. False submarine reports were frequent, and no shore command provided any assessment of the validity of Albert T. Harris’ reports. Nevertheless, submarines were considered an ever-present danger by lookouts and CIC watch personnel.

After sunset on 29 July, Indianapolis ceased zig-zagging by direction of McVay, who had discretion to do so under directives in effect at the time, which required zig-zagging during good visibility, including bright moonlight, neither of which was the case after dark on 29 July. By doing so, he could steam a slower speed, sparing his engines, and still reach Leyte at the desired time for optimum anti-aircraft training in the early morning. This was a calculated decision to both maximize training and avoid excessive wear on his engines. It was not a case of complacency. Nor is there any evidence the lookouts, bridge, and CIC watchstanders were less attentive than they should have been. As the ship was in the heat of the tropics, she was sailing in Condition III (wartime steaming, when danger of surprise air or submarine attack existed). This was typical in order to give the crew some bare minimum of comfort, as higher conditions of readiness could not be sustained for too long.

At 2226 on 29 July (local time—some other accounts use other times), Hashimoto intended to surface, but it was so dark and visibility so poor, he decided against it. At 2335, he tried again and brought I-58 to the surface as the moon started intermittently breaking through the clouds. Almost immediately, a lookout sighted a ship at 11,000 yards (6.3 nautical miles). At first, Hashimoto thought it was a surfaced submarine and he immediately took I-58 down. Through his night scope, Hashimoto could make out a ship approaching, which he then estimated to be an Idaho-class battleship travelling at 12 knots (actually 17 knots). The geometry was a submarine skipper’s dream: It didn’t matter whether Indianapolis zigged or zagged or stayed on steady course—he couldn’t miss. Hashimoto alerted the pilot of Kaiten No. 6 to man his torpedo, with No. 5 in reserve; however, he was convinced the Kaiten would not be able to find the target as dark as it was. Moreover, he didn’t need to: The shot would be well within parameters for conventional torpedoes. When Hashimoto reached 4,400 yards, he realized that when he reached optimum firing position he would be too close for the torpedoes to arm, so he did a curving maneuver to solve that problem.

At 2356, at a range of 1,640 yards, Hashimoto fired all six of his bow Type 95 torpedoes at two-second intervals and set for 13 feet (4 meters). Hashimoto reported seeing three equally spaced hits: one near the bow, one just forward of the No. 1 8-inch turret, and third abreast the No. 2 turret near the bridge.

Given the infrequent glimpses of the moon and distances involved, the likelihood of a lookout seeing a periscope or torpedo wakes in time was very small, and no one did. There was no warning before the first torpedo hit Indianapolis at 0003 on 31 July near the bow just forward of the No. 1 turret. This hit caused a very large secondary explosion. A second torpedo hit between the No. 2 turret and the bridge superstructure with devastating result, knocking out all communications in the forward part of the ship as well as the fire mains. The two engines in the forward engine room were knocked out, and one of two in the aft engine room was badly damaged and shut down. With no communications, the engine room crew did what they were trained to do and kept the remaining engine running at speed, causing Indianapolis to take in massive amounts of water through the gaping holes forward. Essentially, the cruiser drove herself under.

Since Indianapolis had survived severe damage at Okinawa, Captain McVay initially thought the ship might be saved, but within a few minutes it was clear that was not possible as the ship was going down by the bow and taking on a rapid list to starboard. McVay gave the order to abandon ship. He personally tried to ensure a distress message went out, but was washed over the side; he was one of the very last off the ship alive. Both main radio and radio No. 2 sent messages, but none actually went out due to loss of power and damage, although radiomen died trying. Within 12 minutes, Indianapolis rolled over and went down by the bow.

After observing the hits and Indianapolis still moving forward, Hashimoto decided that a second attack would be necessary, so he took I-58 down to 100 feet to re-load torpedoes. He could hear a number of explosions, which were taking place on Indianapolis after she went under. When the explosions ceased, Hashimoto surfaced and went through the area of the sinking at 0100, but later reported seeing no sign of survivors. He then proceeded north and, at 0145, issued a radio report to higher headquarters reporting that he had sunk an Idaho-class battleship. The report was intercepted by U.S. Navy radio intelligence; however, it could only be partially decrypted. The class of ship sunk and the grid coordinates of the sinking were not recovered and remained unknown to anyone in the United States until after the war. So, all Pacific Fleet Intelligence had was a report from I-58 (previously thought to be sunk) reporting sinking an unknown ship in an unknown location with three torpedoes just after midnight on 29–30 July (the report was one of about 500 messages processed that day).

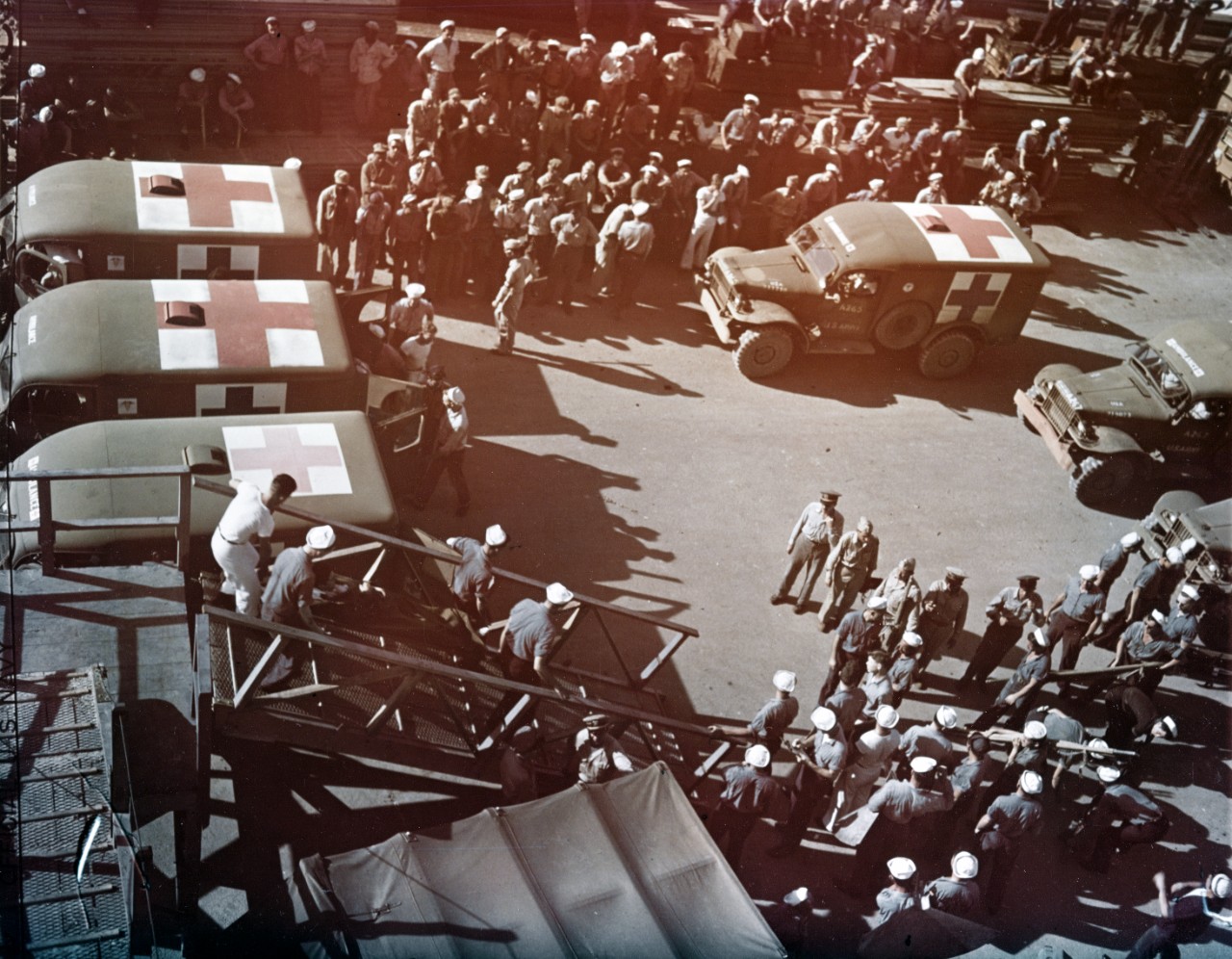

Of the 1,195 men (mostly Navy personnel, but also a Marine Detachment) aboard Indianapolis, somewhere between 200 and 300 went down with the ship. They might be counted among the lucky ones. Since the ship was still making way as it was being abandoned, survivors found themselves scattered across a considerable distance in about 10 different groups. A few of the groups had rafts, some had floater nets, some just had life jackets, and some had nothing. The largest group was about 400 men who only had life jackets. Most of the wounded and those without life jackets or belts succumbed the first night, probably around 100. Those that survived endured up to four and a half days of scorching sun during the day, hypothermia at night, vomiting from ingesting oil, unquenchable thirst, and shark attack. Those who succumbed to drinking seawater (which has the same effect as drinking poison) suffered hallucinations and paranoia before they died. In some cases this caused additional deaths among those in the water, as delusional men fought with each other believing they’d been infiltrated by Japanese. Only 316 men would ultimately survive the horrific ordeal; 808 enlisted men and 67 officers were lost (four more enlisted men would die shortly after being rescued).

The tragedy was compounded by the fact that no one except the Japanese knew Indianapolis had gone down, as no distress messages were received (reports surfaced years later claiming that distress messages had been received, but this is almost certainly not true, although not for lack of trying by some brave radiomen). It was also not due to Indianapolis being on a top secret mission in radio silence—that mission was over. Rather, it was due to communications foul-ups and bad assumptions based on faulty standard operating procedures, and a degree of complacency ashore.

Indianapolis was due to arrive at Leyte on 31 July. When she did not arrive, port authorities assumed she had been diverted elsewhere, which was a common occurrence, and standard procedure was not to report the arrival and departure of warships (the Japanese had radio intelligence, too). So, authorities in Guam did not know that Indianapolis had not arrived at Leyte. The commander of U.S. Navy forces at Leyte (TG 95.7), Rear Admiral Lynde D. McCormick, did not know Indianapolis was on the way because the message to his flagship (ironically, the battleship Idaho) had been garbled in transmission and his communications team had not requested a re-transmission.

At around 1900 on 31 July, a U.S. Army Air Forces C-54E cargo plane passed overhead and reported seeing a “naval action” below (flares from the survivors). This report was dismissed and not passed on under the assumption that if there was a naval action going on, then the Navy already knew about it.