H-Gram 059: Operation Desert Storm in February/March 1991; 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War

5 February 2021

Contents

This H-Gram continues the story of the U.S. Navy in Desert Storm in February 1991 and discusses the war in Vietnam from the Son Tay POW camp rescue attempt in November 1970 to the end of 1971.

Download a PDF of H-Gram 059 (7.5 MB).

30th Anniversary of Desert Storm: February/March 1991

The battleship USS Wisconsin (BB-64) fires a round from one of the Mark 7 16-inch/50-caliber guns in its No. 3 turret during Operation Desert Storm. (National Archives Identifier: 6480274)

For U.S. Navy operations during Desert Shield (August 1990–January 1991) please see H-grams 052, 053, 054, 055, 056, and 058.

Desert Storm commenced in the pre-dawn hours of 17 January (Gulf time) with massive Coalition airstrikes, led by U.S. Navy Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles. Relentless strikes continued in the days afterwards, focused on Iraqi “strategic” targets in priorities determined by the Joint Force Air Component Commander (JFACC). Numerous tactical threat targets (e.g., Mirage F-1s with Exocet missiles, OSA and captured Kuwaiti missile boats, Silkworm coastal defense missile launchers, etc.), many of them fleeting, were not put on the target list by the JFACC and were therefore not struck during this period, increasing the threat to U.S. Navy ships and forcing the Navy to hold back aircraft for fleet defense that could have been put to better use bombing Iraqi targets. Numerous Navy sorties were wasted trying to find Iraqi mobile ballistic missile launchers in the western Iraq desert; although the wildly inaccurate “Scuds” had very limited military impact, the political impact was substantial as Iraq kept firing missiles at Israel, Saudi Arabia, and a couple at Qatar/Bahrain/UAE. U.S. Navy surface ships conducted audacious operations in the northern Gulf, capturing two Kuwaiti islands from their Iraqi garrisons, but were unaware of the true extent of Iraqi minelaying activity (over 1,200 mines) and only by good fortune didn’t hit any, so far. The Iraqi mines put at substantial risk even the amphibious deception plan intended to pin down Iraqi ground divisions on the coast so that the Marines assigned to Marine Forces Central Command (MARCENT) could conduct their attack into southern Kuwait when the Coalition ground offensive commenced. Had the amphibious assault plan actually been executed, Coalitions losses, and especially U.S. Navy losses, would have been significantly higher. (See H-Gram 058 for more on Desert Storm in January 1991.)

After the Iraqi air force fled to Iran (mostly successfully) and the Iraqi navy tried to do the same (mostly unsuccessfully), Vice Admiral Stanley R. Arthur (COMUSNAVCENT) ordered four carriers into the northern Arabian Gulf, which by the arrival of America (CV-66) from the Red Sea on 14 February dramatically increased bomb tonnage per sortie, and doubled sorties per day per carrier, greatly increasing the effectiveness of USN air strikes on Republican Guard and regular Iraqi army units occupying Kuwait. (In the last week before the ground campaign, USN aircraft were dropping more tons of bombs on Iraqi troops and armored vehicles in the “kill-boxes” than the B-52s). This contributed substantially to the destruction and demoralization of these Iraqi ground forces in advance of the Coalition ground campaign, anticipated for late February.

On 2 February 1991, another USN A-6 was lost, this one from VA-36 off Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), overwater south of Faylaka Island, by AAA or shoulder-launched SAM from the island or Iraqi speedboats. The two men aboard, LCDR Barry Cooke and LT Patrick Connor, were killed.

On 3 February, battleship Missouri (BB-63) opened fire with her 16-inch guns for the first time since the Korean War, with eight shells targeted on Iraqi bunkers in southern Kuwait. In addition, a mine (or more likely a stray HARM) exploded near destroyer Nicholas (FFG-47) causing light damage by shrapnel.

On 5 February, an Air Wing EIGHT (CVW-8) F/A-18, flown by LT Robert Dwyer, was returning to Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) from a strike mission over Iraq when his plane disappeared over the North Arabian Gulf. Neither plane nor pilot was ever found.

On 6 February, battleship Missouri opened up again with 112 16-inch and 12 5-inch rounds in eight fire support missions in the next 48 hours hitting Iraqi targets in southern Kuwait. Within two hours of relieving Missouri, battleship Wisconsin (BB-64) let loose with 11 16-inch rounds against an Iraqi artillery battery in southern Kuwait.

On 7 February two F-14s of Fighter Squadron VF-1 off Ranger (CV-61) received a vector from an E-3A AWACS to a low altitude contact and the lead F-14 shot down an Iraqi Mi-8 helicopter with an AIM-9M sidewinder missile, the first USN air-to-air kill since the first days of the war. The same day, Wisconsin used her Pioneer Remotely Piloted Vehicle (RPV) to target Iraqi artillery and communication sites in southern Kuwait.

On 13 February, carrier America transited the Strait of Hormuz, joining Midway (CV-41), Ranger, and Theodore Roosevelt in the North Arabian Gulf targeting Iraqi ground forces in Kuwait in preparation from the Coalition ground offensive. The same day USN aircraft destroyed an Iraqi Super Frelon (Exocet-capable) on the ground in southern Iraq.

On 18 February, U.S. Navy and Coalition units commenced an approach toward the Kuwaiti coast in preparation for executing an amphibious feint in support of the amphibious deception plan. The flagship of the minesweeping force was Tripoli (LPH-10), with six MH-53 minesweeping helicopters embarked. Unknowingly, Tripoli was steaming in a minefield all night. At 0436, Tripoli struck a moored contact mine in the outer Iraqi minefield, which was further from the coast than anticipated. The mine blew a large hole near the bow; fortunately fuel and paint fumes that filled forward compartments did not explode, otherwise the damage might have been catastrophic. Fortunately, no one was killed and Tripoli continued operations, although it became apparent the damage was more severe than initially thought, and in a few days Lasalle (AGF-3), commanded by future four-star John Nathman, would take over duties leading the minesweeping force. Chief Damage Controlman Joseph A. Carter and Chief Warrant Officer Van Cavin were each awarded a Silver Star for their actions in the immediate aftermath of the mine strike on Tripoli.

At 0716 18 February, the AEGIS cruiser Princeton (CG-59) was maneuvering into position to provide air defense coverage (having already passed through the outer moored contact minefield without detecting or hitting one) for the minesweeping force when she triggered an Italian-made Manta bottom-influence mine under her stern, which in turn triggered the sympathetic detonation of another Manta about 350-yards away. That no one was killed and casualties were comparatively light belied the severity of damage to the ship. Had the Manta detonated directly under the ship, as it was designed, the damage likely would have been fatal with very high casualties. A higher sea state might also have caused loss of the ship, which had to be towed away for repair. (Of note, CNO Michael Gilday was in the crew of Princeton).

On 20 February, AEGIS cruiser Valley Forge (CG-52) vectored an Anti-submarine Squadron VS-32 S-3 Viking aircraft onto an Iraqi gunboat, which the S-3 destroyed with a 500-pound bomb; the first combat kill by an S-3.

By 22 February, it became apparent that Iraqi forces in Kuwait were conducting massive sabotage of Kuwait’s oil infrastructure with well over 100 oil wells being set on fire, covering southern Kuwait in a pall of dense oil-fire smoke. It also became apparent that Saddam Hussein was withdrawing some of his troops and claiming a great victory before the Coalition ground campaign even started. By this time it was estimated that the Iraqis had already lost 1,685 tanks, 925 armored personal carriers, and 1,450 artillery pieces to Coalition air strikes. By 23 February, over 200 Kuwaiti oil wells were on fire. The same day Missouri bombarded Iraqi targets on Faylaka Island (a Kuwaiti Island northeast of Kuwait City).

At 0400 24 February, MARCENT Marines (elements of 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions), under Lieutenant General Walt Boomer, USMC, commenced an assault into southern Kuwait, into the strongest Iraqi defenses. Intended as a “supporting” attack, the purpose of the Marine attack was to fix Iraqi units in place so that the U.S. Army could advance unimpeded around the Iraqi right flank west of Kuwait, around the extensive Iraqi fortifications, and hit the Iraqis from the west and cut off their retreat to the north. This was described by the Commander, U.S. Central Command, General Norman Schwarzkopf, as the famous “Hail Mary” maneuver. Instead, partly due to superior Intelligence on the precise locations of Iraqi defenses, but more to superb combat engineering and vastly superior fire and maneuver tactics, the Marines blew through the vaunted Iraqi defenses with surprisingly few casualties. Some Iraqis put up stiff but ineffective resistance, while many others quickly surrendered. The Marines advanced so far so fast that General Schwarzkopf ordered the U.S. Army to advance their timetable otherwise the Marines were going to be in Kuwait City before the Army even crossed the line of departure. The Marine advance was conducted under the hellish conditions of over 500 burning oil wells, but aided by shelling from battleships Missouri and Wisconsin.

On the morning of 25 February, NAVCENT forces were conducting a vastly scaled back amphibious feint on the coast of Kuwait, with Missouri conducting fire-support operations (133 16-inch rounds) in a small swept area (because that was all that could be swept in the time available) only a few miles off the coast when a previously hidden Iraqi Silkworm anti-ship missile battery fired two Silkworms at Missouri. One Silkworm fell short in the water. The second missed Missouri (or was possibly deflected by jamming or chaff) before it was shot down by a Sea Dart surface-to-air missile from British destroyer HMS Gloucester, after it passed CPA (closest point of approach) to Missouri. By the end of the war Missouri and Wisconsin had fired over 1,000 16-inch rounds.

Also on 25 February, one of the over 70 “Scud” ballistic missiles fired by Iraq finally hit a military target, killing 27 U.S. Army personnel and wounding more than 100 when it fell on a barracks in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, the most Coalition casualties in a single incident in the war.

On 26 February, U.S. Navy jets and other coalition aircraft bombed retreating Iraqi troops on the road from Kuwait City north to Iraq. Blasted vehicles blocked both ends of the road, resulting in a huge traffic jam of hundreds of trapped vehicles and thousands of troops that quickly turned into a slaughter. The carnage was so massive that there was risk of breaking the fragile Coalition if other Arab member nations perceived it as a gratuitous massacre of helpless brother Arabs. As it was, it quickly became known as the “Highway of Death.” Some of the better Iraqi Republican Guard forces managed to escape the massive U.S. Army armored assault closing in from the west at breakneck speed (those few Iraqi units that resisted were steamrollered) so what was trapped in Kuwait were mostly hapless Iraqi conscripts.

The “Highway of Death” was a significant factor in Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell’s recommendation to end of the Coalition offensive and to declare victory after 100 hours. At 2100 EST 27 February 1991 (0500 28 February Gulf time) President Bush announced that Kuwait was liberated and Coalition offensive operations ceased.

During Desert Storm, the six U.S. aircraft carriers launched 18,117 fixed-wing sorties of which 16,899 were combat or direct support sorties, of about 94,000 total U.S. and Coalition fixed-wing combat sorties. The Navy lost seven aircraft in combat (two F/A-18, four A-6E, one F-14) and four to accidents (F/A-18, A-6E, SH-60, H-46). The Navy lost six men killed in action (all aviators) and eight personnel killed in non-combat accidents. Three U.S. Navy Prisoners of War were turned over by the Iraqis on 4 March. Maritime Interception Operations continued and by the end of February reached 7,500 intercepts, 940 boardings, and 47 diversions.

Overall Coalition aircraft losses were 75 aircraft (including helicopters). Of those losses, 65 were U.S. aircraft, of which 28 U.S. fixed wing aircraft were lost in combat. Overall U.S. deaths in Desert Storm were 148 killed in action and another 145 non-battle deaths plus 467 wounded in action. Most estimates of Iraqi deaths are between 25,000 and 50,000 although some are as high as 100,000. Over 71,000 Iraqis surrendered. Over 100,000 Iraqis apparently deserted prior to or during the Coalition Ground Offensive. Nevertheless, to the great consternation of everyone, when it was all over, Saddam Hussein was claiming Iraq won a great victory.

For more on Desert Storm (Part 2) Please see attachment H-059-1. (The Great Scud Hunt, Mine Warfare, Over the Top, Silkworm Shot, The Highway of Death, Vision of Hell.)

The next H-Gram will contain Desert Storm statistics as well as discussion of the role of Sealift, Seabees, and Navy Medical personnel in Desert Storm.

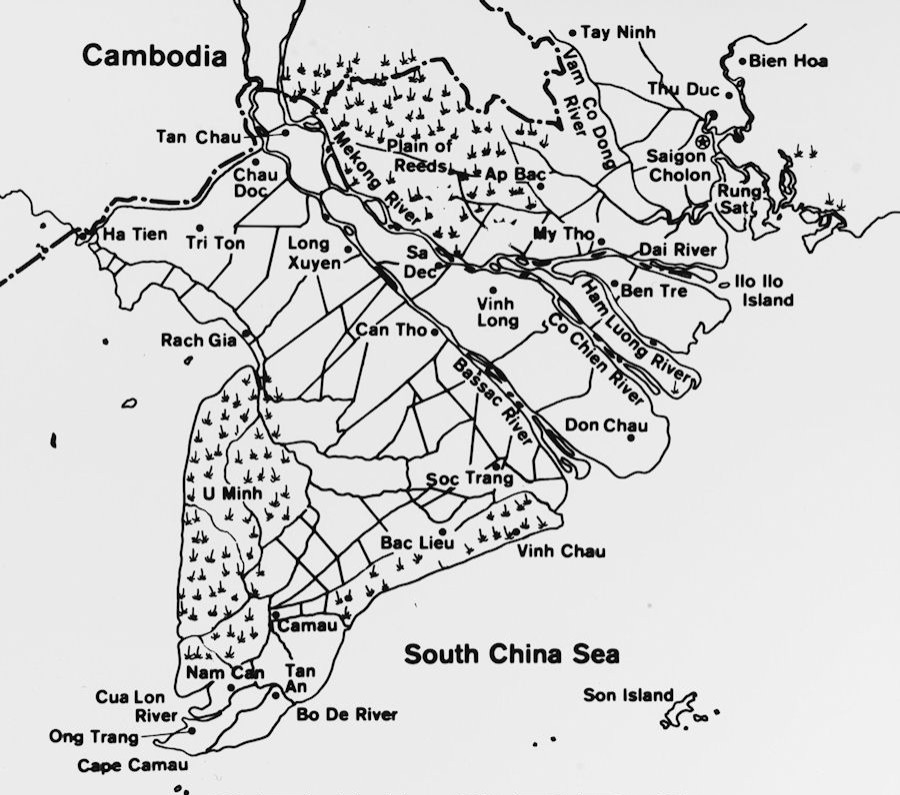

The Sealords Operational Theatre, from By Sea, Air, and Land, by Edward J. Marolda.

50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War

(Of note, National Vietnam War Veteran’s Day is observed annually on 29 March.)

U.S. Navy Operations in the Vietnam War from November 1970 to December 1971.

The largest night carrier operation of the Vietnam War occurred 20-21 November 1970 when carriers Ranger (CVA-61) and Oriskany (CVA-34) launched over 50 aircraft over North Vietnam and along the coast in order to provide a diversion for the daring U.S. Army/U.S. Air Force attempt to rescue U.S. Prisoners of War from the Son Tay POW Camp, only 23 miles from Hanoi. Due to the Rules of Engagement at the time, almost all the Navy aircraft were unarmed, dropping flares to simulate bomb strikes and dropping chaff to simulate a minelaying mission near Haiphong. The twenty North Vietnamese surface-to-air missiles fired at the Navy aircraft were fully armed, but all of them missed. The Navy diversion was a success and the Son Tay raid force got in and out of the target without significant casualties. The dangerous mission was almost flawlessly executed, but the North Vietnamese had moved all 65 POWs at Son Tay to a camp closer to Hanoi in July 1970, resulting in extensive recriminations regarding the “failed” mission. Although unknown at the time, the “failed” mission resulted in a huge boost in morale for the POWs (tangible proof they had not been forgotten) as well as significantly better treatment of the POWs by the North Vietnamese.

For background on the origins of “Vietnamization” strategy, see H-Gram 028: U.S. Navy Valor in Vietnam, 1969.

In 1971, the Nixon administration’s policy of “Vietnamization” of the war was in full stride, with the number of U.S. troops in the country and number of U.S. casualties rapidly decreasing as Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) troops were trained and took on more combat roles. Despite this, opposition to the Vietnam War continued to intensify in the United States, and groups such as Vietnam Veterans Against the War greatly increased in size and became increasingly vocal. A major test of the Vietnamization policy came in February 1971 when a 20,000-strong South Vietnamese force launched an offensive (Operation Lam Son 719) into Laos to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail (the North Vietnamese supply route through Laos and Cambodia and into South Vietnam). Despite rosy pronouncements in Saigon and Washington, the South Vietnamese force got chewed up by intense North Vietnamese resistance and thrown back out of Laos with very heavy casualties (including 107 U.S. helicopters lost and 25X U.S. military personnel killed while trying to support the South Vietnamese.)

The Vietnamization of the naval war went much better, and by mid-1971, almost all riverine and coastal patrol missions and craft had been turned over to the South Vietnamese navy, although air support from the U.S. Navy’s light attack helicopter squadron (HA(L)-3) “Seawolves” and light attack squadron (VA(L)-4) “Black Ponies” continued unabated. Naval gunfire missions along the South Vietnamese coast continued to dramatically decrease and U.S. Navy amphibious forces were withdrawn from Vietnamese waters, although some remained in Subic Bay, Philippines, on alert. The previous successes of Operation Market Time (interdiction of seaborne infiltration of South Vietnam) resulted in the lowest number of infiltration attempts by North Vietnamese trawlers in 1971 (one trawler reached South Vietnam, nine aborted their missions when detected, and one was caught by U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Navy, and Vietnamese navy vessels and blew up with the loss of all hands).

For more information on Vietnamization, see H-043-2: “Sojourn Through Hell”—Vietnamization and U.S. Navy Prisoners of War, 1969–70.

With the moratorium on bombing in North Vietnam still in effect (with some very limited exceptions) while interminable “Peace Talks” were ongoing in Paris, U.S. carrier strike operations were focused almost exclusively on interdicting the northern end of the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos, a very challenging mission resulting in significant losses with little strategic effect. At the start of 1971, the USN maintained a three attack carrier (CVA)-rotation, with two CVAs on Yankee Station (day/night) and one CVA in Subic for R&R and resupply, plus one ASW carrier (CVS) in the Gulf of Tonkin. The number of carriers on station and number of strike sorties steadily decreased throughout 1971 due in part to the weather (three typhoons) but mostly due to fiscal cutbacks necessitating conservation of fuel, ammunition, and aircraft flight hours. By the end of 1971, combat sorties were at the lowest level since Operation Rolling Thunder started in 1964. However, there were ominous signs at the end of the year that the situation was about to change. While talking peace in Paris, the North Vietnamese were actually preparing for a massive conventional invasion of South Vietnam in 1972, which would result in some of the most intense U.S. naval combat since WWII.

For more on the naval war in Vietnam in 1971, please see attachment H-059-2.