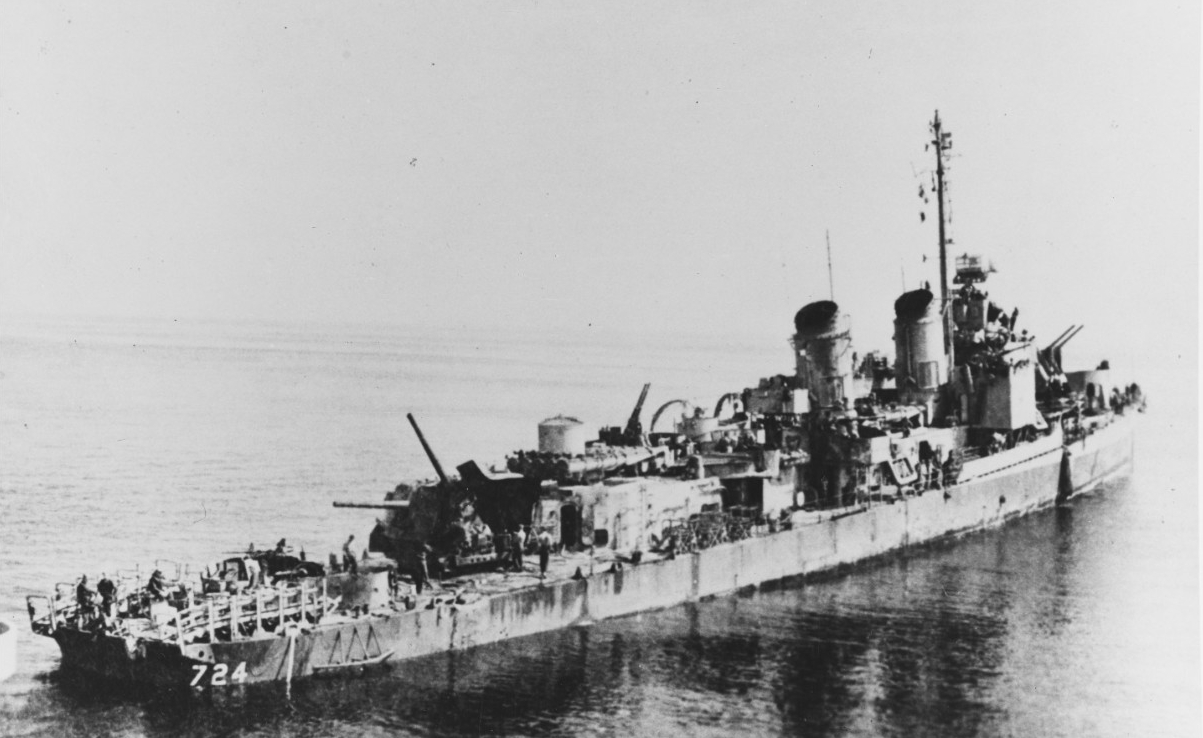

H-045-1: The Ship That Wouldn’t Die (2)—USS Laffey (DD-724), 16 April 1945

“No! I’ll never abandon ship as long as a single gun will fire!”

—Commander Frederick J. Becton, commanding officer, USS Laffey (DD-724), 16 April 1945

Prelude

USS Laffey (DD-724) was the second U.S. destroyer named after Irish-born Seaman Bartlett Laffey, who was awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions as member of the crew of the Union stern-wheel gunboat USS Marmora in action ashore against Confederate forces at Yazoo City, Mississippi, on 5 March 1864. The first USS Laffey (DD-459) was a Benson-class destroyer that had rescued survivors of the torpedoed carrier Wasp (CV-7), and fought in the Battle of Cape Esperance off Guadalcanal. She was lost in heroic action in the brutal no-quarter 13 November 1942 night melee off Guadalcanal, in which she dueled the Japanese battleship Hiei with a CPA (closest point of approach) of 20 feet. Laffey lost 59 of her 247 crewmen, was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation, and her skipper, Lieutenant Commander William Hank, was posthumously awarded his second Navy Cross (see H-Grams 011 and 012).

The second Laffey was one of 58 new Allen M. Sumner–class destroyers (of which 55 were completed during the war), designed as a follow-on to the Fletcher class. Laffey was 2,200 tons, with a speed of 34 knots and a crew of 336. Instead of the Fletchers’ five single 5-inch gun mounts, Laffey had three twin 5-inch/38-caliber gun mounts, with two forward and one aft. This was double the forward firepower of a Fletcher and, at long range, the aft 5-inch mount on Laffey was designed to fire over the mainmast, adding even more forward firepower. Laffey retained the two quintuple 21-inch torpedo tube mounts from the early Fletchers (many Fletchers and Sumners would later have one torpedo bank removed in favor of additional 40-mm anti-aircraft guns). In addition, Laffey had 12 40-mm Bofors and 11 20-mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns, plus six K-gun depth-charge throwers, and two depth-charge racks on the stern.

From bow to stern, Laffey’s gun armament was as follows: Mount 51 (twin 5-inch/38-caliber), Mount 52 (twin 5-inch/38-caliber) superimposed over Mount 51. Two 20-mm antiaircraft guns were on each side of the forward superstructure (Groups 21 and 22). A twin 40-mm mount was on each side of the forward stack (Mounts 41 and 42). Two 20-mm guns were on the port side of the aft stack (Group 24). Two 20-mm guns were on the starboard side above the aft deckhouse (Group 23). Two quad 40-mm mounts were on top of the aft deckhouse, staggered starboard (Mount 43) and port (Mount 44), so both mounts could train to either side or aft. Mount 53 (twin 5-inch/38-caliber) was aft of the deckhouse. Three 20-mm guns (Group 25) were on the fantail in a triangular arrangement, between Mount 53 and the depth-charge racks on the stern.

The commanding officer of Laffey since her commissioning on 8 February 1944 was 36-year-old Commander Frederick Julius Becton (USNA ’31), one of the most battle-tested skippers at that time, already with four Silver Stars. Becton had been the executive officer of destroyer Aaron Ward (DD-483) during the same battle in which the first Laffey was lost. During that battle, two powerful Japanese “Long Lance” torpedoes passed under Aaron Ward without exploding before she hit Japanese destroyer Akatsuki (which blew up and sank) and before getting hit nine times in return, going dead in the water, and nearly being hit the next morning by main battery 14-inch shells from the crippled Japanese battleship Hiei. Aaron Ward suffered 15 dead and 57 wounded.

Becton was in command of Aaron Ward on 7 April 1943 when she was bombed and sunk by six Japanese Val dive-bombers while defending a convoy off Guadalcanal that included LST-449 (with Lieutenant Junior Grade John F. Kennedy as a passenger on his way to assume command of PT-109). Despite valiant attempts by her crew to save her, Aaron Ward sank with the loss of 27 killed or missing and 59 wounded (see H-Gram 018).

Becton was awarded his first Silver Star as the operations officer for Destroyer Squadron 21, embarked on the destroyer Nicholas (DD-449) during the Battles of Kula Gulf, Kolombangara, and other night actions in the Central Solomon Islands between 5–13 July and 17–18 August 1943. Becton’s second Silver Star was awarded while he was in command of Laffey during the Normandy “D-Day” invasion of June 1944. Laffey bombarded German gun emplacements on 8 and 9 June, and drove off an attack by German E-boats on 12 June that had blown off the stern of destroyer Nelson (DD-623) with a torpedo (see H-Gram 031). Laffey then participated in the Battle of Cherbourg on 25 June, in which battleships Nevada (BB-36), Texas (BB-35), and Arkansas (BB-33) dueled with large-caliber German shore batteries. During this engagement, Laffey was hit by a medium-caliber (about 6-inch) shell that skipped off the water and lodged itself in the boatswain’s locker without detonating. The unexploded shell was hoisted out and rolled overboard.

After Normandy, Laffey sailed to the Pacific, participating in operations in support of the Leyte landings in October 1944, where she subsequently rescued and captured a downed Japanese pilot, who was transferred to carrier Enterprise (CV-6). Becton received his third Silver Star in command of Laffey for actions during kamikaze attacks at the landings at Ormoc Bay, Philippines, on 7 December, and then a fourth Silver Star for defending against kamikaze during the landings at Lingayen Gulf, Philippines, in January 1945 (see H-Gram 040).

During the Okinawa Operation, Laffey was assigned to the Gunfire and Covering Force (Task Force 54—TF 54) Unit 2, under the command of Rear Admiral C. Turner Joy, supporting old battleships Arkansas (BB-33) and Colorado (BB-45), and heavy cruisers San Francisco (CA-38) and Minneapolis (CA-36). TF 54 supported the capture of Kerama Retto before providing pre-invasion bombardment of Okinawa and then gunfire support to forces ashore.

On 12 April 1945, Laffey received orders to proceed to Kerama Retto and cross-deck the fighter direction team from destroyer Cassin Young (DD-793), which had been damaged and had suffered one dead and 59 wounded in a kamikaze attack that day on Radar Picket Station No. 1. The next day, Laffey received her orders to proceed to the same station, brought on board the two fighter direction officers and three enlisted men with their special electronics gear, and also loaded 300 additional rounds of 5-inch ammunition so as to have a full load out. Laffey arrived at Radar Picket Station No. 1, 30 nautical miles northwest of the northern tip of Okinawa, relieving destroyer-minesweeper J. William Ditter (DM-31), which, on 4 June, would get hit by a kamikaze and knocked out of the war.

Already on Radar Picket Station No. 1 were two large support landing craft: LCS(L)-51, commanded by Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering, and LCS(L)-116, commanded by Lieutenant A. J. Wierzbicki. The 160-foot LCS(L) was an adaptation of the infantry landing craft (LCI) with additional 40-mm (fore and aft) and 20-mm guns, and .50 caliber machine-guns, along with two high-capacity pumps that enabled it to act as fire and rescue craft.

During the day on 14 April, Laffey’s fighter direction team shared combat air patrol with destroyer Bryant (DD-665) on Radar Picket Station No. 3 to vector aircraft in shooting down a group of three and then a group of eight Japanese planes, none in range of Laffey’s guns. (Some accounts switch the order of these two events.)

Sunday, 15 April, was quiet for Laffey, with no engagements. The destroyer was directed to investigate a downed Japanese aircraft that had remained afloat. Laffey found the plane, with the dead pilot still in the cockpit, crewmen retrieved the pilot’s codebook and other items of interest from the plane, and then Laffey sank it.

Monday, 16 April 1945: Laffey Fights for Her Life

There are many accounts of LAFFEY’s fight. All of them differ to varying degrees about specifics of the Japanese attacks, particularly in the latter stages. Times, type of aircraft, direction of attack, and other details often don’t match. I used Laffey’s own after-action report as the baseline, but even that was subject to revision over the years. I have attempted to reconstruct the attack using multiple sources and will try to highlight those aspects on which all accounts substantially agree and note some of the differences.

At 0800 on 16 April, the sea was smooth with a light breeze and very good visibility. At 0808, Laffey’s air search radar detected many incoming aircraft from the north and the destroyer commenced maneuvering on various courses and speeds. Laffey’s fighter direction officer requested immediate combat air patrol and the escort carrier Shamrock Bay (CVE-84) scrambled four FM-2 Wildcats of Composite Squadron 94 (VC-94), but they would take time to reach Laffey. By 0825, Laffey’s radar showed too many aircraft to count. These aircraft were the lead elements of Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) No. 3, the third mass Japanese kamikaze attack on U.S. forces off Okinawa. Kikusui No. 3 included a total of 165 kamikaze aircraft (120 Japanese navy and 45 Japanese army) and 150 other aircraft in conventional strike and escort roles.

At 0830, one Aichi D3A Val dive-bomber was observed in proximity of Laffey, probably conducting reconnaissance. When fired upon by Laffey’s forward 5-inch guns, the Val jettisoned its bomb and departed. Shortly afterward, four more Vals were spotted at a range of eight miles to the northeast. When fired upon, the Vals split into two pairs and commenced a coordinated attack from ahead and astern Laffey. Commander Becton maneuvered to try to bring broadside (maximum number of guns) to bear on the Vals. There had been debate in the U.S. Navy as to whether the best way to defeat kamikaze aircraft was by radical maneuver or by bringing the maximum number of guns to bear. Eventually, it was decided that although maneuver was effective against bombs, the faster speed of the kamikaze rendered the ships’ maneuvers moot, and maximizing firepower became the preferred tactic—although skippers had to make split-second decisions to adapt to specific circumstances.

Laffey’s Mounts 51 and 52 took the two Vals on the starboard bow under fire, downing one Val (aircraft number one) at 9,000 yards and another (number two) at 3,000 yards. (Some accounts indicate that the first two Vals were hit by 20-mm gunfire—effective range 1,600 yards, max range 7,400 yards). Mount 53 took the two Vals circling down the starboard side to get behind Laffey under fire and hit one (number three) with VT-fuze ammunition at 3,000 yards. The Val’s fixed landing gear caught a wave top and the damaged plane crashed into the sea. The other Val (number four), crossing starboard-to-port astern was hit by fire from both Mount 53 and from LCS(L)-51 (which was on Laffey’s port quarter) and crashed about 5,000 yards to port from the destroyer near LCS(L)-51. Laffey was four for four at this point with no hits received (some accounts credit the support landing craft with the shoot down of the fourth Val and this is at least partially correct).

Almost immediately after the four Vals were shot down, two newer and faster Yokosuka DY4 Judy dive-bombers commenced near simultaneous high-speed attacks from opposite sides. The Judy (number five) approaching from the starboard quarter was shot down by 40-mm and 20-mm fire at 3,000 yards. Ten seconds later, the Judy (number six) coming in from the port quarter was strafing as it was hit by 40-mm and 20-mm fire before crashing in the water close aboard the after stack. The port Judy’s bomb exploded, wounding several gunners and knocking out the SG surface search/low-altitude aircraft and fire control radar antenna, and a radio antenna. Fires were quickly extinguished and other crewmen took the place of wounded gunners. Laffey was now six for six (or five for six), with some damage from a near-miss kamikaze and bomb explosion.

First Kamikaze Hit. At 0839, another Val (number seven) came in from the port bow through 5-inch fire and was hit and slightly deflected by 20-mm gunfire. The Val grazed the top of Mount 53 from fore to aft and crashed just off the starboard quarter. The gun captain in Mount 53 was spared as he had just ducked inside the turret to deal with a misfire in one of the 5-inch guns, but one man in the mount was killed by wing fragments of the plane. The plane also spewed aviation fuel over the after parts of Laffey. (Some accounts count this as a kamikaze hit and others as a near miss).

At 0843 a third Judy (number eight) came in low and fast on the starboard beam and was hit by 40-mm and 20-mm fire before it exploded in mid-air close aboard. In only 12 minutes of battle, Laffey’s gunners were seven for eight, with only some damage received from a two near-miss kamikaze plane crashes. This was followed by about a three-minute respite.

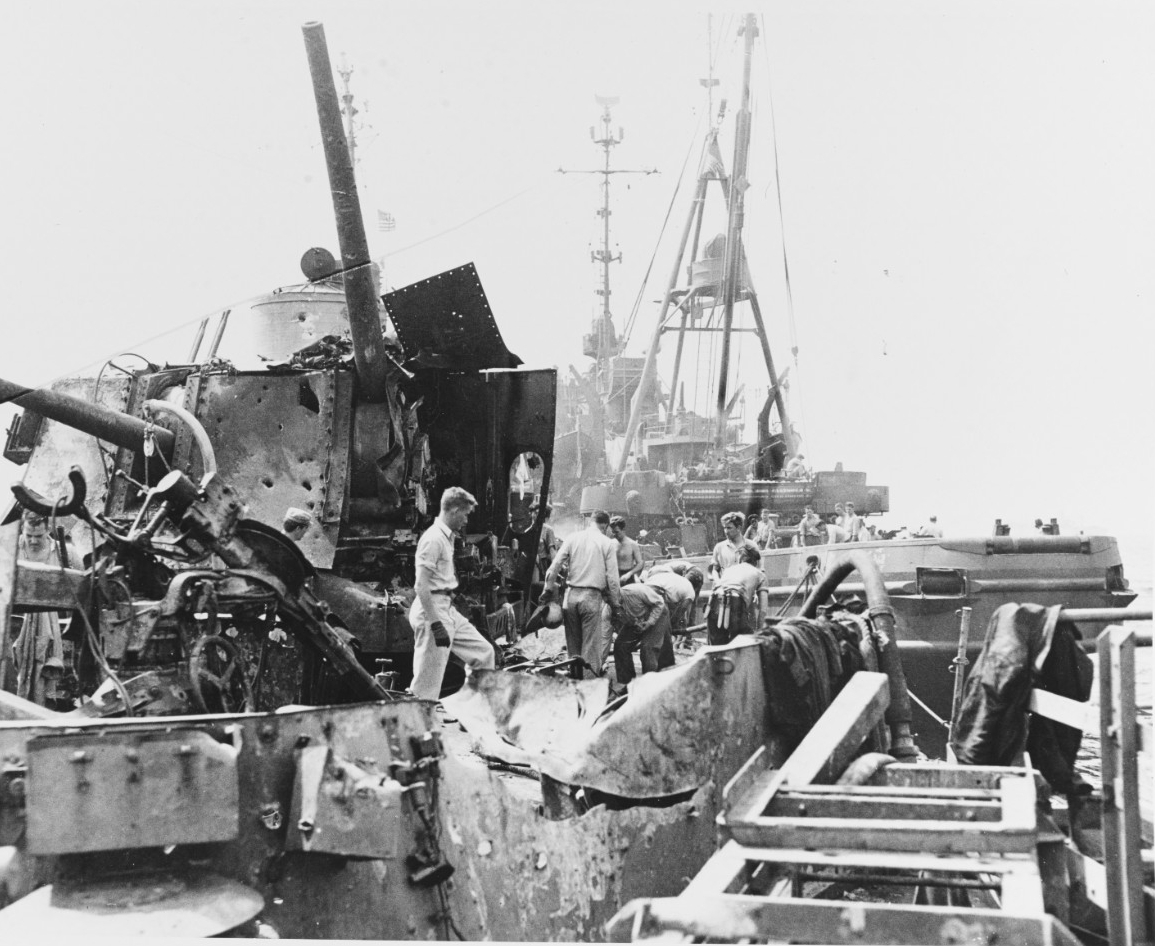

Second Kamikaze Hit. At 0845, another Judy (number nine—some accounts note a Val) came in from the port beam and Laffey’s luck began to run out. Despite repeated 40-mm and 20-mm hits, the Judy just missed the port motor whaleboat and then crashed into the two 20-mm mounts (Group 23) on the starboard side abaft the after stack, spewing burning gasoline, destroying the guns, and killing three gunners outright while a fourth jumped over the side in flames. The fire overran the two 40-mm quad mounts (43 and 44) on top of the after deckhouse, significantly reducing Laffey’s defensive firepower. Fires also threatened Mount 44’s magazine below; fortunately, the protective cans for the 40-mm ammunition prevented a larger explosion. Clips of 40-mm shells around the gun tubs began to cook off even as crewmen were jettisoning them over the side (Mount 43 would be re-manned in local control when fires were extinguished). The crash also knocked out communication to the forward engine room, but the engineers would crank up speed to the max when they heard heavy and fast gunfire and slow down when it was quiet.

Third Kamikaze Hit. At 0847, a Val (number ten) came in low from astern, strafing as it approached and, despite being hit by 20-mm fire from the fantail guns, crashed through the 20-mm mounts (Group 25), destroying all three and killing six gunners before hitting the starboard after corner of Mount 53 as flaming gasoline covered the fantail. The plane disintegrated and the bomb exploded, starting a major fire that threatened the aft 5-inch magazine, which Becton quickly ordered flooded. The gun captain of Mount 53, who was directing fire from the side hatch (because the top hatch had been jammed shut by the plane that had grazed the turret) was somewhat miraculously blown clear of the turret unharmed.

First Bomb Hit, Fourth Kamikaze Hit. Moments afterward, yet another Val (number 11) came out of the sun from astern, dropped a bomb that hit two feet inboard of the deck edge abeam Mount 53, and crashed into Mount 53, finishing it off and killing six men inside.

Second Bomb Hit. Less than two minutes later, another Val (number 12— Laffey’s after-action report doesn’t specifically identify this aircraft by type) came in from astern and dropped a bomb that hit the ship on the starboard quarter just above the propeller guard. Although taken under fire by the 20-mm guns in Group 24 (by the after funnel on the port side), the plane flew on. The bomb exploded in the after 20-mm magazine and fragments ruptured hydraulic lines in the steering gear and jammed the rudder at 26 degrees to port. After this hit, Laffey steamed in a tight circle, with only acceleration and deceleration as a means to disrupt Japanese aim. Even though the ship was down by the stern, it was her good fortune that the watertight bulkheads and hatches to the aft engineering spaces held, which prevented severe flooding and also ensured that she had full power throughout the attack. At this point, Mount 53 and 40-mm Mounts 43 and 44 were out of action, along with five 20-mm mounts destroyed, making Laffey very vulnerable from astern.

During these attacks on Laffey, the four FM-2 Wildcats off Shamrock Bay were engaging over 20 Japanese aircraft of various types, which would have made Laffey’s situation even worse. Lieutenant (j.g.) Carl J. Rieman rolled in on a Val that jinked and was then shot down by Rieman’s wingman, Dick Collier. Rieman then shot down a Val and subsequently fired on a Nakajima B5N Kate torpedo bomber, killing the pilot and sending it down. He then hit another Kate with the last of his ammunition and, as he followed the plane down to see if it would crash, an F4U Corsair came in and added more holes to it. Some of the fighters continued to make attempts to scatter the Japanese even when they were out of ammunition. Not counting Rieman’s last Kate, which he didn’t claim, the four Wildcats accounted for six Japanese aircraft before they had to break off, low on fuel and ammunition (some accounts say only four Japanese were shot down). (Rieman survived the war and, when he passed in 2011, had 12 children, 50 grandchildren, 84 great-grandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren.)

Also, as Laffey was being attacked, so too were the two support landing craft. LCS(L)-116’s forward 40-mm mount was about to fire on a Japanese plane, when an F4U Corsair fighter arrived and shot it down. However, another kamikaze came in carrying a bomb and hit the after 40-mm mount, killing three and wounding others. Yet another kamikaze came in and good shooting by a .50-caliber machine gun hit the plane in the cockpit. It overshot and impacted the water on the far side. LCS(L)-116 ultimately suffered topside damage along with 17 dead and 12 wounded during additional attacks.

Fifth and Sixth Kamikaze Hits. As the badly damaged Laffey steamed in tight circles, two kamikaze in quick succession came in from the vulnerable port quarter. The first one, a Val (number 13), crashed into the after deckhouse as damage control parties were fighting the fires. Moments later, a Judy (number 14) crashed into almost the same spot in a big ball of fire, killing four crewmen and starting another major gasoline fire.

About this point, 12 U.S. Marine Corps F4U Corsairs of VMF-441 “Blackjacks,” launched from Yontan Airfield on Okinawa, joined the fray, shooting down between 15 and 17 Japanese aircraft in the vicinity of Laffey. VMF-441 had arrived at Yontan on 7 April. Yontan was one of the two major airfields captured in the first day of the invasion (Yontan by the Marines and Kadena by the Army). The Marine Corsairs performed heroically, often pursuing Japanese aircraft into Laffey’s anti-aircraft fire. Aircraft shot down by Corsairs, in whole or in part near Laffey, also account for the differing numbers of aircraft reported as downed by the destroyer.

A Val (number not reported) came at Laffey from the port side, pursued by a Corsair. The Corsair forced the Val to overshoot the destroyer and crash in the water on the ship’s far side. (This is not reflected in the after-action report or in Morison, but is mentioned in some accounts. This may have been one of the many aircraft downed by Corsairs that are not included in Laffey’s report, which only includes those that were near threats to the ship.)

A Ki-43 Oscar (number 15) fighter came at Laffey from the port side on a strafing run with a Corsair in hot pursuit. Gunners on Laffey tried to shoot down the Oscar without hitting the Corsair. The Oscar hit the destroyer’s mast with its wing, carried away the port yardarm and the U.S. ensign, struggled to gain altitude, but then crashed in the water on the starboard side. The pursuing Corsair hit Laffey’s SC air search radar antenna and knocked it down. The damaged F4U was able to gain enough altitude so the pilot could roll the plane over and bail out before the aircraft crashed. The pilot was rescued by LCS(L)-51. A signalman climbed Laffey’s mast and attached a brand-new flag. (All accounts are fairly consistent on this episode, except some have the Oscar coming from starboard. The Oscar was a Japanese army fighter, which would indicate an unusual combined navy and army attack on the same target. Although the reports note an Oscar, it is also true Oscars were easily confused with Japanese Navy A6M Zero/Zeke fighters.)

First Bomb Near Miss. A Judy (number 16) coming in fast and low from the port bow with a Corsair on its tail crashed close aboard a few yards from Laffey. Its bomb exploded, spraying fragments over the forward part of the ship, mortally wounding one gunner and wounding two others including the gun captain in Mount 52, and severing communications with the forward two 5-inch gun mounts. The machine gun control officer, Ensign James Townsley, quickly rigged a work-around, climbing on top of the pilot house with a microphone that he plugged into the ships’ loudspeaker system, and providing warning and direction of incoming aircraft (Townsley would be awarded a Silver Star for this action). The Corsair is generally give credit for shooting down this kamikaze.

Another Judy (number 17), coming in fast and low from the starboard quarter, was shot down by 40-mm (Mount 41) and 20-mm (Group 21) fire at 800 yards from the ship (sixth or seventh plane shot down by Laffey).

An Oscar (number 18), coming in from the starboard beam, took a direct hit in the engine by a 5-inch shell from Mount 52, which was still firing in local manual control despite the damage and wounded gunners from the earlier hit. The Oscar disintegrated 500 yards from the ship. Mount 51, also operating in local, shifted fire to a Val (number 19) coming in from the starboard bow and knocked it down with a VT-fuze shell, also about 500 yards from the ship (seventh and eighth or eighth and ninth plane shot down by Laffey).

There was a brief lull at this point, during which the assistant communications officer, Lieutenant Frank Manson, noted the severe damage to the aft end of the ship and asked Commander Becton if he was considering abandoning the ship. Becton responded that he would not abandon the ship as long as there was single gun left to fire. Although Laffey was down by the stern and her aft end was mostly on fire or burned out, her hull integrity was still in good shape.

Third Bomb Hit. Using the sun and smoke from Laffey as cover, a Val (number 20) approached from the destroyer’s undefended stern and planted a bomb on her fantail, blowing an eight-by-ten-foot hole in the deck just aft of Mount 53. Shrapnel from the bomb hit the emergency casualty aid station topside. The bomb also killed Ensign Robert Thomsen, who had left his station in the command information center after the radars were knocked out in order to take charge of a fire party aft (for which he would receive a posthumous Navy Cross), along with other members of the fire party. The Val clipped the starboard yardarm, but kept going until it was shot down by a Corsair ahead of the ship. The 20-mm gunners in Group 21 (starboard forward) continued to fire on the Val to make sure it crashed.

Fourth Bomb Hit. Another Val (number 21) came in from the starboard bow strafing. Despite fire from 5-inch, 40-mm, and 20-mm guns, the plane dropped a bomb and barely cleared the ship before it was shot down by a Corsair. Seaman Feline Salcido didn’t think Commander Becton saw the bomb coming in and he shoved the skipper down as the bomb exploded in the 20-mm Group 21 (which had been firing to the last) just below the starboard bridge. Fragments penetrated the wardroom, which was being used as a casualty aid station, killing several of the wounded, the attending pharmacist’s mate, and wounding the ship’s doctor.

At 0947, another Judy (number 22) came in from port side forward with a Corsair on its tail. Hit repeatedly by 40-mm (Mount 42) and 20-mm (Group 22) fire and by tracer fire from the pursuing Corsair, the Judy finally blew up close aboard and crashed (credit has generally been given to the Corsair).

By this time, additional combat air patrol had arrived, including Corsairs from carrier Intrepid (CV-11) and Hellcats from light carrier San Jacinto (CVL-30), and the Japanese attacks on Laffey finally ceased. Although the situation on Laffey was dire, with the stern down due to flooded compartments aft, fires still raging aft and the steering gear still jammed over, Becton assessed his ship as still 30 percent combat effective. The elevating mechanism of Mount 51 had a break in its hydraulic line and had to be elevated manually. Mount 52 had no electrical power and had to be trained and elevated manually. The 40-mm twin Mounts 41 and 42 were undamaged and the quad Mount 43 had been re-manned after fires had been beaten back, but electrical power to the directors was knocked out and all were operating in degraded mode. Four of the 11 20-mm guns (Group 22 and 24), all on the port side, were still operating. The air search and surface search radars were destroyed.

Aftermath

At about 1100, LCS(L)-51 came alongside to assist with firefighting, although she had been damaged during the battle as well, and had shot down several aircraft herself. LCS(L)-51 had a seven-foot hole in her port side amidships and three crewmen wounded.

During the 80-minute attack, Laffey had shot down at least eight aircraft and damaged the six kamikaze that hit her. Moreover, she had been damaged by four direct bombs hits (plus bombs carried by the kamikaze). Laffey’s heroic crew suffered 32 dead and 71 (or 72) wounded.

Destroyer-minesweeper Macomb (DMS-23) took Laffey in tow toward Kerama Retto at four knots, which was a struggle due to the jammed rudder, before turning the destroyer over to tugs Pakana (ATF-108) and Tawakoni (ATF-114). After emergency repairs, Laffey departed Kerama Retto on her own power on 22 April, heading toward to Seattle via Saipan and Pearl Harbor. While at Pier 48 in Seattle, Laffey was opened to public viewing. Apparently, there was some concern that shipyard workers were “slacking off” in anticipation of the war’s end, and this was intended as motivation to demonstrate that the conflict was still far from over.

In addition to her five battle stars, Laffey was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. Commander Frederick Julian Becton was awarded the Navy Cross. Ensign Robert Clarence Thomsen was awarded a posthumous Navy Cross. Other crewmen were awarded six Silver Stars, 18 Bronze Stars,and one Navy Letter of Commendation. The commanding officer of LCS(L)-51, Lieutenant Howell D. Chickering, was also awarded a Navy Cross as his ship was given credit for downing six Japanese aircraft.

Presidential Unit Citation for USS Laffey:

For extraordinary heroism in action as a Picket Ship on Radar Picket Station Number One during an attack by approximately 30 enemy Japanese planes, thirty miles northwest of the northern tip of Okinawa on 16 April 1945. Fighting her guns valiantly against waves of hostile suicide aircraft plunging toward her from all directions, the USS LAFFEY set up relentless barrages of anti-aircraft fire during an extremely heavy and concentrated air attack. Repeatedly finding her targets, she shot down eight enemy planes clear of the ship and damaged six more before they crashed on board. Struck by two bombs, crash-dived by suicide planes and frequently strafed, she withstood the devastating blows unflinchingly and, despite severe damage and heavy casualties, continued to fight effectively against insurmountable odds, and her brilliant performance in this action reflects highest credit upon herself and the United States Naval Service.

For the President,

James Forrestal

Secretary of the Navy

Navy Cross citation for Commander Becton:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander Frederick Julian Becton, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Destroyer USS LAFFEY (DD-724), in action against enemy Japanese forces off Okinawa, on 16 April 1945. With his ship under savage attack by thirty hostile planes, Commander Becton skillfully countered the fanatical enemy tactics, employing every conceivable maneuver and directing all his guns in an intense and unrelenting barrage of fire to protect his ship against the terrific onslaught. Crashed by six of the overwhelming aerial force which penetrated the deadly anti-aircraft defense, the USS LAFFEY, under his valiant command fought fiercely for over two hours against the attackers, blasting eight of the enemy out of the sky. Although the explosions of the suicide planes and two additional bombs caused severe structural damage, loss of armament, and heavy personnel casualties, Commander Becton retained complete control of his ship, coolly directing repairs in the midst of furious combat, and emerged at the close of the action with his gallant warship afloat and still an effective fighting unit. His unremitting tenacity of purpose, courageous leadership and heroic devotion to duty under fire were inspiring to those who served with him and enhanced the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Navy Cross citation (posthumous) for Ensign Robert Clarence Thomsen:

Ensign Thomsen, Navigator, served as assistant evaluator in Combat Information Center (CIC) during this action, performing his duties in a superior manner. After radars were put out of action by two direct hits on the mast and his services were no longer required, he proceeded aft to assist in fighting fires that were raging as a result of two suicide crashes and a bomb hit. He fearlessly led a fire hose team into the smoke and flame of Compartment C-204-LM, where fires were threatening to set off ammunition in 5-inch Mount 3 upper handling room and in the after 5-inch magazine. There he met his death when two suicide planes crashed near him. Although his primary duties were in CIC, he unhesitatingly risked, and lost, his life when he realized the urgency of the situation which threatened the destruction of his ship. His conduct was exemplary and a source of inspiration to those who carried on the fight to save the ship, for which he had given his life.”

Ensign Thomsen belonged to the USNA class of ‘45 (accelerated graduation in 1944).

As a good commanding officer and leader, Becton gave full credit to his crew: “Performance by all hands was outstanding…. [T]he engineers played a vital part in saving the ship by the manner in which they furnished speed and more speed on split second notice….. [G]unnery personnel demonstrated cool-headed resourcefulness and continued to deliver accurate fire throughout the action, often in local control. Damage control parties were undaunted, although succeeding hits undid much of their previous efforts and destroyed more of their firefighting equipment. They were utterly fearless in combating fires, although continually imperiled by exploding ammunition…. [E]specially deserving of mention were the 20mm gunners of whom at least four were killed ‘in the straps’ firing to the last.”

Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison noted that one of the many heroes was 18-year old Coxswain Calvin W. Cloer, who was badly burned while serving a gun. Upon seeing the wardroom crowded with other wounded who he deemed to be in need of more medical attention, he returned to his gun and was subsequently killed by a bomb. Morison noted that, “not a single gun was abandoned, despite the flames and explosions.”

Laffey’s squadron commander, Captain B. R. Harrison, attributed the destroyer’s survival to the fact that she retained full engine and boiler power throughout, and to the superb ship handling by the commanding officer in taking most of the damage aft and avoiding the full effects of crashes from forward. Rear Admiral C. Turner Joy, commander of the Fire Support Force, TF 54 Unit 2, added that laffey’s performance “stands out above the outstanding.”

After the war, Commander Becton went on to serve in multiple assignments, including as executive officer of the light cruiser Manchester (CL-83), and as commanding officer of attack transport Glynn (APA-239), battleship Iowa (BB-61), Cruiser Division 5, and Mine Force Pacific Fleet. He was promoted to rear admiral in 1955 and retired in 1966 as Naval Inspector General.

Laffey would be repaired and reactivated for the Korean War, earning two Battle Stars screening Task Force 77 carriers Antietam (CV-36) and Valley Forge (CV-45) in March through June 1952, while also participating in the bombardment and blockade of the North Korean port of Wonsan and engaging several shore batteries. She sailed through the Suez Canal on 22 June 1952, returning to Norfolk after completing her first around-the-word deployment. In 1954, Laffey completed her second around-the-world deployment. In 1956, the destroyer participated in U.S. Navy reaction to the 1956 Suez Crisis following the Arab-Israeli War. The rest of her career consisted primarily of operating from the U.S. East Coast in anti-submarine hunter-killer task groups until she was decommissioned in 1968.

Laffey is currently a museum ship at Patriot’s Point, Charleston, South Carolina, and is a designated National Historic Landmark. There is reportedly a Hollywood movie, to be directed by Mel Gibson, about Laffey in the works called Destroyer.

Morison summed it up best when he stated that “probably no ship has ever survived an attack of the intensity that she experienced.”

Why the U.S. Navy has not seen fit to name another warship after Laffey, or Commander Becton, is a damn fine question.

Sources include: “USS Laffey Report of Damage by Bombs and Suicide Planes during Air Action on April 16, 1945,” dated 27 April 1945, from Commanding Officer to the Chief of the Bureau of Ships; History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1960); NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS): “USS Laffey: Attacked off Okinawa in World War II,” by Dale P. Harper in World War II Magazine (March 1998) at historynet.com; The Ship That Would Not Die, by F. Julian Becton (Missoula, MT: Pictoral Histories Publishing Co., 1987); Hell from the Heavens: The Epic Story of the USS Laffey and World War II’s Greatest Kamikaze Attack, by John Wukovits (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2015).