H-046-1: USS Aaron Ward (DM-34)—"The Ship That Couldn't Be Licked," 3 May 1945

Naval Historian Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison stated in his History of United States Naval Operations in World War II that probably no ship survived an attack of greater intensity than the destroyer USS Laffey (DD-724) did on 16 April 1945 (see H-Gram 045). The crew of the destroyer-minesweeper Aaron Ward (DM-34) might dispute that, as their ship suffered more damage and higher casualties than Laffey and, although the total number of kamikaze and bombing attacks was less, they came in even more rapid succession. Nevertheless, the crew of Aaron Ward saved their ship in an epic of damage control following an intense suicide attack at the beginning of the massed kamikaze attack Kikusui (“Floating Chrysanthemums”) No. 5 on 3 May 1945.

Aaron Ward (DM-34) was a Robert H. Smith–class destroyer-minelayer, commissioned on 28 October 1944, under the command of Commander William H. Sanders, USN. The Robert H. Smith class essentially comprised Allen M. Sumner–class destroyers with the ten torpedo tubes (two banks of five) and two of six K-gun depth-charge throwers removed and replaced with the capability to carry and lay up to 80 mines. Otherwise their armament was the same as that of the regular destroyers, with two twin 5-inch/38-caliber dual-purpose turrets forward (mounts 51 and 52), one twin 5-inch/38-caliber aft (mount 53), two twin Bofors 40-mm anti-aircraft guns on each side of the forward stack (mounts 41 and 42) and two quad 40-mm mounts atop the after deckhouse (mounts 43 and 44), situated so that both mounts could fire astern or to either side. Like the Allen M. Sumners, the Robert H. Smiths had 8 to 11 (depending on the ship) Oerlikon 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, plus four side-throwing K-gun depth-charge launchers along with two depth-charge rolling racks on the stern. In terms of tons (2,200), length (376 feet), speed (34 knots), and crew size (363), the two classes were virtually the same.

The Robert H. Smith–class destroyer-minelayers were designed in anticipation of a mission to establish a blockade of Japan, in which the ships would dash in and mine the entrances to Japanese ports. None of them were ever used in this manner and none ever laid mines operationally. Initially used to protect minesweeper forces, they were regularly employed interchangeably with other destroyers.

The first Aaron Ward (DD-132) was a destroyer built during World War 1 and named after Rear Admiral Aaron Ward, who had been commended for gallantry in command of the armed yacht Wasp during the Battle of Santiago in the Spanish-American War of 1898. At the time of his mandatory age retirement in 1913, he was second-in-command of the Atlantic Fleet. During World War I, he was the captain of the Red Cross ship Red Cross, which provided medical aid to wounded and sick soldiers of all nationalities. As a result, Aaron Ward may be to only U.S. flag officer to be given a medal by an enemy nation, the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s Medal of Merit, awarded by Emperor Franz Joseph.

DD-132 served in the U.S. Navy (mostly in reserve) from 1919 to September 1940, when she was leased to the United Kingdom along with 49 other equally aging destroyers in exchange for U.S. basing rights in British territories in the Western Hemisphere (this was prior to U.S. entry into the war against Nazi Germany). As HMS Castleton, the former DD-132 escorted Atlantic convoys during World War II and rescued survivors from sunken cargo ships. In November 1941, she was damaged in an explosion, then repaired and returned to service. On 20 August 1942, Castleton and HMS Newark captured 51 survivors of German submarine U-464 who had been picked up by an Icelandic trawler. Considered obsolete, she was placed in reserve in March 1945 and scrapped after the war without returning to U.S. service.

The second Aaron Ward (DD-483) was a Gleaves-class destroyer (4 single 5-inch guns) commissioned in March 1942 under the command of Commander Orville F. Gregor, USN; the executive officer was Lieutenant Commander Frederick Becton. Aaron Ward conducted several shore bombardments in October and November of 1942 in support of U.S. Marines fighting the Japanese ashore on Guadalcanal. On the night of 12–13 November 1942, Aaron Ward fought valiantly in the brutal night action with two Japanese battleships and numerous destroyers and barely survived, suffering 15 killed and 57 wounded. (The first Laffey [DD-459] was among the U.S. ships lost in this battle.) The commander of the South Pacific Ocean Area, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., commended Aaron Ward in an after-action report, “The AARON WARD gave another fine example of the fighting spirit of the men of our destroyer force. Though hit nine times by both major and medium caliber shells which caused extensive damage, she nevertheless avoided total destruction by the apparently superhuman efforts of all hands. The superb performance of the engineer’s force in effecting temporary repairs so the ship could move away from under the guns of the enemy battleship largely contributed to saving the ship.” Commander Gregor was awarded a Navy Cross and would eventually retire as a rear admiral.

After repairs, Aaron Ward rejoined the fleet in February 1943, now under the command of her former executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Becton. On 7 April 1943, Aaron Ward was escorting LST-449 (which had future U.S. President John F. Kennedy, a junior grade lieutenant, embarked), when one of the last significant Japanese air raids off Guadalcanal rolled in. Aaron Ward was hit by three Japanese navy Val dive-bombers in an especially well-executed attack out of the sun, in which one bomb was a direct hit and two were devastating near misses, with an underwater mining effect. As she went dead in the water, and despite an intense anti-aircraft barrage from her gunners, three more Vals scored two more damaging near misses on the immobile destroyer. Her crew fought for over seven hours to save her, but the damage was just too great and she sank only 600 yards from being beached on Guadalcanal. Aaron Ward suffered 27 killed or missing and 59 wounded. Becton would later be given command of the second Laffey (DD-724).

The first commander of the third Aaron Ward (DM-34), Commander William H. Sanders, had joined the U.S. Navy as an apprentice seaman in 1925 before subsequently attending and then graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1930. After her commissioning on 28 October 1944, Aaron Ward conducted work-ups and proceeded to the Western Pacific to participate in her first combat operation, the invasion of Okinawa, during which she provided escort protection to the Mine Flotilla.

Aaron Ward arrived in the Okinawa area on 22 March and supported the minesweeping operations around Kerama Retto, during which she shot down three Japanese aircraft. On 1 April, she assumed duty screening the battleships and cruisers conducting gunfire support to the main U.S. Army and Marine landings on Okinawa. She then escorted empty transports to the Marianas before returning to Okinawa on 27 April, shooting down one Japanese plane on that day. On 28 April, Aaron Ward was operating near Kerama Retto and shot down one Japanese plane. She claimed another as a probable. Then, she rescued 12 crewmen who had been blown into the water when the evacuation transport Pinkney (APH-2) was hit and badly damaged by a kamikaze.

On 30 April, the ship assumed duty at Radar Picket Station No. 10 (RP10), located to the west-southwest of Okinawa and Kerama Retto, a station that was comparatively quiet compared to those to the north of Okinawa. RP10 was on the axis of attack from Formosa, but the British carrier force (Task Force 57) had handled and borne the brunt of attacks from that direction. On the evening of 30 April, Aaron Ward fired on several air raids, but the Japanese did not press the attacks. Poor weather prevented further air attacks over the next few days until the afternoon of 3 May, when the skies began to clear. Visibility was excellent at the surface, but some low clouds provided an advantage to any attacking aircraft.

On station with Aaron Ward on 3 May was the destroyer Little (DD-803) and four smaller amphibious support craft, LSM(R)-195, LCS(L)-25, LCS(L)-14, and LCS(L)-83. Little was the penultimate of 175 Fletcher-class destroyers commissioned during the war and had previously seen action on the gun line at Iwo Jima that February 1945. Her skipper was combat veteran Commander Madison Hall (USNA ’31), with a Silver Star swarded for his command of destroyer Jenkins (DD-447) at the Battle of Kolombangara on 13 July 1943. Little had initially operated with the Okinawa demonstration (decoy) group and had previous experience on radar picket stations—her crew knew what to expect.

At 1820, about 45 minutes before sunset on 3 May, about 18–24 Japanese aircraft approached the ships on Radar Picket Station No. 10. For whatever reason, by the approach of dusk, a significant distance had opened between the support craft and the two destroyers, so that the two groups were not mutually supporting at the onset. Of note, the after-action reports (and most every account is based on them) describe these aircraft as Japanese navy Val dive-bombers and Zeke fighters, but Japanese records do not corroborate that many Vals and Zekes airborne at the time. This attack was most likely conducted by Japanese army aircraft flying from Formosa, and the aircraft identified as Vals are most likely older Japanese army Nate fighters (which, like Vals, had fixed landing gear) and other Japanese army fighters (Ki-43 Oscars and Ki-84 Franks) that were frequently misidentified as navy Zekes during the war. This would have been even more likely given the fading light.

Radar on Aaron Ward and Little detected the incoming raid at 27 miles out and, at 1822, Aaron Ward’s crew was called to general quarters. At about 1840 (reporting of times in this action is inconsistent between ships), two Japanese planes broke from formation and headed for Aaron Ward while several others went for Little. Aaron Ward opened fire on the first aircraft (number one) coming in from the starboard quarter at 7,000 yards and the second kamikaze (number two) at 8,000 yards on the port beam. Despite being hit repeatedly, both aircraft kept coming, with the first commencing its dive at 4,000 yards before the pilot was killed or lost control. The plane crashed 100 yards short, although the its engine, propeller, and a wing part bounced off the water and crashed into the after deckhouse, which fortunately did not cause great damage. (In photos of Aaron Ward, the three-bladed prop can be seen stuck in the deckhouse bulkhead just forward of mount 53.) The second plane finally crashed 1,200 yards from the ship.

As Aaron Ward was fighting off the first two attackers, Little was fighting several more kamikaze that made effective use of the low clouds to cover their approach, giving Little little time to defend herself. Despite repeated hits by Little’s anti-aircraft fire, four kamikaze crashed her in less than four minutes. The first kamikaze hit the port side, destroying the aft low-pressure turbine and condenser. A second kamikaze was shot down, but another one hit moments later in almost the same location as the first, causing additional severe engine room damage. Little took a third hit from another kamikaze portside amidships damaging the No. 3 boiler. Less than a minute later a fifth kamikaze (and the fourth to hit) crashed into the after torpedo mount in a near vertical dive, detonating the torpedo air flasks as the plane’s engine penetrated deep in the ship, bursting the No. 3 and No. 4 boilers, and causing a large explosion that probably broke Little’s keel.

As Little went dead in the water with no power or internal communications, and settling rapidly, her crew tried to control the damage, but the last hit had been fatal. By 1850, the main deck was almost awash, and several minutes later Commander Hall ordered abandon ship. Little went under 12 minutes after the first hit, suffering six dead, 42 missing (most declared dead), and 79 wounded (31 total were killed). Hall would be awarded his second Silver Star for his valiant attempt to fight the kamikaze and save the ship in the few minutes he had.

As Little was in her death throes, a Japanese plane (number three) (identified as a “Zeke” in most accounts) dove from the clouds from astern Aaron Ward. Despite being hit repeatedly, the aircraft kept coming, dropping a bomb just before it crashed into Aaron Ward’s after deckhouse. The bomb penetrated the hull below the waterline and detonated in the after engine room, quickly resulting in flooding that space and the after fireroom (bomb hit number one). Fuel tanks burst, resulting in a severe oil fire that cut steering control to the bridge, with the rudder jammed hard to port and the ship slowing to 20 knots. Meanwhile, the gasoline fire from the crashed plane (kamikaze hit number one) burned the after deckhouse, severing power and communications to mount 53, which from that point fought in manual local control. With two engineering spaces flooded, rudder jammed, losing speed, and fires raging, Aaron Ward was already in extremis and in worse shape than Laffey had been.

As the support ships rushed to come to the aid of Little and Aaron Ward, they were also attacked by kamikaze aircraft. Large support landing craft LCS(L)-25 was damaged by debris from a downed kamikaze that crashed close aboard, suffering three killed and three wounded. She proceeded to rescue many of the survivors from Little before limping into Kerama Retto (by then known by the black humor nickname, “Busted Ship Bay”). LCS(L)-83 was also nearly hit twice by kamikaze, before she shot down two more.

Less lucky was the rocket-armed medium landing ship LSM(R)-195, commanded by Lieutenant W. E. Woodson, attacked almost simultaneously by two Japanese aircraft, one on an effective strafing run and the other in a suicide attack. LSM(R)-195 was hit by a twin-engine kamikaze identified (probably correctly) as a Ki-45 “Nick,” a Japanese army aircraft. The explosion of the plane and bomb inflicted fatal damage, knocking out the fire main and auxiliary pumps, and causing secondary explosions among the ship’s own rocket launchers (75 quadruple rail Mk. 36 rocket launchers). The rockets shot off in all directions, so there was no hope that the crew could save her. Woodson smartly ordered abandon ship, and shortly thereafter LSM(R)-195 suffered a massive explosion and went to the bottom, with a loss of nine crewmen and 16 wounded of her 81-man crew. Most of her survivors were picked up by destroyer BACHE (DD-470), which was rushing from Radar Picket Station No. 9 to assist, having just been narrowly missed by a kamikaze that overshot the her (Bache would get hit on 13 May).

Bache and destroyer-minesweeper Macomb (DMS-23), operating with three large support landing craft, LCS(L)-89, -111 and -117, on Radar Picket Station No 9 (just to the east of Aaron Ward), had come under kamikaze attack about the same time as Aaron Ward and Little. Two Japanese army Ki-61 Tony fighters attacked. Although Macomb had control of some combat air patrol fighters, the fighters missed the intercept in the clouds. In the melee, a U.S. Navy FM-2 Wildcat of VC-96 was shot down by “friendly” fire and the pilot rescued by LCS(L)(3)-111. Meanwhile, the two Tonys bored in at high speed. At 1829, one Tony went for Bache, was hit multiple times, missed the ship, and crashed off her port quarter.

Less than a minute later, the second Tony aimed for Macomb’s bridge and was deflected only at the last second and hit the No. 3 5-inch gun aft, blowing off the after part of the gun’s blast shield and killing most of the gunners. A large gasoline fire ignited, but, fortunately, the Tony’s 500-pound bomb passed clear through the after deckhouse and exploded in the water off the port quarter. Macomb’s damage control parties had the fire out in about three minutes and damage was relatively modest, although the ship suffered seven killed and 14 wounded. Macomb then remained on the radar station alone for another three hours as Bache was ordered to assist Aaron Ward.

Macomb’s skipper, Lieutenant Commander Alton Louis Clifford “Red” Waldron, was awarded a Silver Star and Macomb, which had previously sunk German submarine U-616 in the Atlantic, was awarded a Naval Unit Commendation for her role in shooting down numerous Japanese aircraft around Okinawa. Macomb’s damage would be repaired in time for her to be present in Tokyo Bay for the Japanese surrender. Ironically, the ship would end up serving in the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) as Hatakaze (D-182) from 1954 to 1969, before then being transferred to the Republic of China (Taiwan) Navy.

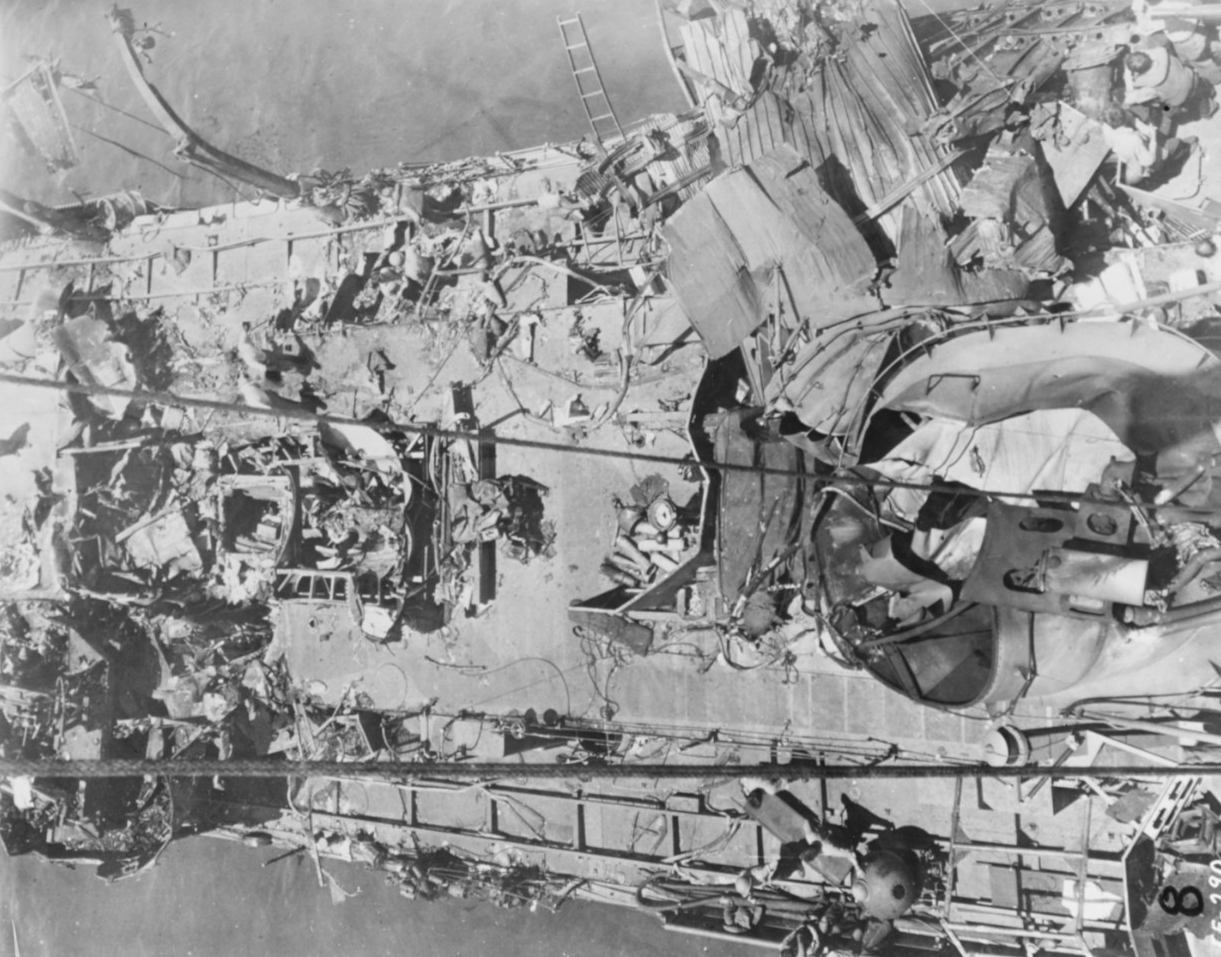

USS Aaron Ward (DM-34): Damage amidships received during kamikaze attacks off Okinawa on 3 May 1945. View looks down and aft from Aaron Ward's foremast, with her greatly distorted forward smokestack in the lower center. Photographed while the ship was in the Kerama Retto on 5 May 1945. A mine is visible at left,on the ship's starboard mine rails (80-G-330107).

As Little was sinking, and after the kamikaze and bomb hit on Aaron Ward, circling Japanese aircraft did not press home further attacks for about 20 minutes, turning away each time they were fired on by the burning Aaron Ward. Steering control was shifted to after steering, which brought her out of her circle, but steering was still erratic. Finally, as it appeared Aaron Ward was not going to quickly sink, just after 1900 another Japanese aircraft (number four) commenced an attack run. Aaron Ward opened fire at 8,000 yards and downed the plane at 2,000 yards (third aircraft shot down). At about the same time, another aircraft (number five) attacked, but exploded and disintegrated after a direct hit by Aaron Ward’'s gunners (fourth aircraft shot down).

Minutes after the third and fourth kamikaze were shot down, two more Vals (numbers six and seven) attacked from the port bow while being chased by American fighters. One was shot down by either the fighters or anti-aircraft fire (fifth plane shot down), but the other made it through the gauntlet despite being hit. Making a steep dive directly at Aaron Ward’s bridge, the plane was hit or buffeted enough by the heavy anti-aircraft fire that it veered at the last second. It missed the bridge, crossing above the signal bridge, carrying away antennas and halyards, before it smashed into the top of the forward stack and then bouncing overboard just to starboard (kamikaze hit number two). Fortunately, this hit also did relatively little damage.

At 1913, shortly after the glancing blow by the seventh kamikaze, another aircraft (number eight) attacked from forward of the port beam. The plane was hit at 2,000 yards and caught fire, but kept on coming and dropped a bomb just before it crashed into the main deck amidships. The bomb hit the water and exploded a few feet beyond the ship on the starboard side. It sprayed the topsides with fragments and blew a large hole in the hull plating near the forward fireroom, flooding the forward fireroom and causing Aaron Ward to lose all power and headway (kamikaze hit number three, first damaging bomb near miss). Aaron Ward was now a sitting duck and only her remaining gunners operating in manual local control could buy enough time for her repair parties to stem the flooding and put out the fires.

The gunners wouldn’t have much of a chance as only four seconds later, a Zeke (number nine) made an unobserved approach through the clouds and smoke of Aaron Ward’s fires. It crashed into the deckhouse near the aft starboard 40-mm mount (mount 43), igniting an even bigger gasoline fire that killed many of the crew who were fighting the fires as well as gunners (kamikaze hit number four). Fortunately, this plane did not appear to be carrying a bomb. Aaron Ward went dead in the water with the only power being supplied by the forward emergency diesel generator.

At 1921, two more kamikaze (numbers 10 and 11) attacked in quick succession. One kamikaze came in on a steep dive from the port quarter. Because of the loss of power, none of the 5-inch guns were able to engage, and the few remaining 40-mm and 20-mm guns didn’t have the stopping power and the plane crashed into the port superstructure. It started still more gasoline fires and caused 40-mm ammunition to cook off, which resulted in extensive casualties (kamikaze hit number five). The other kamikaze (number 11) came in from forward, despite being hit by 40-mm fire, with a final high-speed low-altitude run from the port side. The kamikaze struck amidships at the base of the after stack and the plane’s bomb exploded, obliterating the stack and blowing a searchlight and two 20-mm guns high into the air. Most of the debris landed back aboard the ship, causing even more casualties (kamikaze/bomb hit number six). This proved to be the last attack of 52 minutes of hell.

By this time, Aaron Ward’s topsides aft of the forward stack were burned and mangled, the ship was settling with an eight-degree list and only five inches of freeboard at the main deck. Were it not for the forward emergency diesel generator, which enabled some fire main pressure, the ship probably would have been lost at this point. However, even as darkness fell, and into the night, her skipper and crew refused to give up the ship. Despite imminent danger of sinking, damage control parties went deep into the ship to wet down ammunition magazines to keep them from exploding. By 1935, LCS(L)-14 and LCS(L)-83 were alongside helping to fight the fires and assisted with over 50 badly wounded men and 20 lesser injuries. By 2045, the fires were out.

At 2106, destroyer-minelayer Shannon (DM-25) was able to take Aaron Ward in tow as the seas were relatively calm and take her slowly to Kerama Retto, arriving on the morning 4 May 1945. Aaron Ward received a message from Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, which stated, “We all admire a ship that can’t be licked. Congratulations on your magnificent performance.” The cost for this accolade was very high. Aaron Ward suffered 19 crewmen killed outright. Six died of their wounds. Sixteen men and one officer were missing, for a total of 42 lost. Somewhat astonishingly, only one officer was lost, Lieutenant (j.g.) Robert N. McKay, USNR, Supply Corps. Fifty Sailors and four officers were seriously wounded and many more had minor injuried.

Due to the number of damaged ships at Kerama Retto, temporary repairs to Aaron Ward were not completed until 11 June, when she got underway for the United States via Ulithi, Guam, Eniwetok, Pearl Harbor, and the Panama Canal, finally arriving at the New York Navy Yard in mid-August. With the war ending and the damage so great, she was decommissioned on 28 September 1945 and sold for scrap in 1946 without repairs being completed. Her 4,000-pound anchor ended up in a park in Elgin, Illinois (where it is today), at the request of the father of one of the Sailors lost aboard. Aaron Ward only earned one Battle Star for her World War II service, but she was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.

The commanding officer of Aaron Ward, Commander William H. Sanders, was awarded the Navy Cross, and numerous other crewmen were recognized for their valor in saving the ship. One Sailor that went unrecognized, due to the systemic racism of the time, was Steward First Class Carl E. Clark, an African American crewman who put out a fire in an ammunition locker, quite possibly saving the ship, and carried many wounded shipmates to safety from the fires and flooding. In 2012, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus presented a Navy Commendation Medal with Combat V to Carl Clark (who passed away in 2017).

The Presidential Unit Citation for Aaron Ward reads as follows:

For extraordinary heroism in action as a Picket Ship on Radar Picket Station during a coordinated attack by approximately 25 Japanese aircraft near Okinawa on 3 May 1945. Shooting down two kamikazes which approached in determined suicide dives, the USS AARON WARD was struck by a bomb from a third plane as she fought to destroy this attacker before it crashed into the superstructure and sprayed the entire area with flaming gasoline. Instantly flooded in her after engine room and fireroom, she battled against flames and exploding ammunition on deck, and, maneuvering in tight circles because of damage to her steering gear, countered another suicide attack and destroyed three kamikazes in rapid succession. Still smoking heavily and maneuvering radically, she lost all power when her forward fireroom flooded after a seventh suicide plane which dropped a bomb close aboard and dived in flames into the main deck. Unable to recover from this blow before an eighth bomber crashed into her superstructure bulkhead only seconds later, she attempted to shoot down a ninth kamikaze diving toward her at high speed and, despite the destruction of nearly all her gun mounts aft when this plane struck her, took under fire the tenth bomb-laden plane, which penetrated the dense smoke to crash on board with a devastating explosion. With fires raging uncontrolled, ammunition exploding and all engine spaces except the forward engine room flooded as she settled in the water and listed to port, she began a night-long battle to remain afloat and, with the assistance of a towing vessel, finally reached port the following day. By her superb fighting spirit and the courage and determination of her entire company, the AARON WARD upheld the finest traditions of the Unites States Naval Service.

For the President,

James Forrestal

Secretary of the Navy

The Navy Cross citation for Commander Sanders reads:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Commander William Henry Sanders, Jr., United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Destroyer USS AARON WARD (DM-34), in action against enemy aircraft on 3 May 1945, while deployed off Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands. With his radar picket station the target for a coordinated attack by approximately twenty-five Japanese suicide planes, Captain Sanders gallantly fought his ship against the attackers and, although several bomb-laden planes crashed on board, skillfully directed his vessel in destroying five kamikazes, heavily damaging four others and routing the remainder. Determined to save his ship despite severe damage and the complete loss of power during this action, he then rallied his men and renewed the fight against raging fires, exploding ammunition, and the flooding of all engineering spaces until, after a night-long battle to keep the ship afloat, he succeeded in bringing her into port. By his inspiring leadership and courage in the face of overwhelming odds, Captain Sanders upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Captain Sanders continued to serve after the war, including as commanding officer of the destroyer tender Dixie (AD-14) operating off Korea during the Korean War, before he retired in 1959 as a rear admiral.

No U.S. Navy ships since World War II have been named for Aaron Ward or William Sander.

Sources include: Brave Ship, Brave Men, by Arnold S. Lott (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1964); “History of USS Aaron Ward (DM-34)” at destroyers.org; Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships by Aircraft and Other Means, by Robin L. Rielly (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2010); Desperate Sunset: Japan’s Kamikazes Against Allied Ships, by Mike Yeo (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2019); NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); and History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1961).