H-038-2: The Battle of Leyte Gulf in Detail

“CRIPDIV 1"—U.S. Carrier Attacks on Okinawa and Formosa, 10–16 October 1944

Following closely on the heels of a typhoon (dubbed “Task Force Zero” by wags on Admiral Halsey’s staff), the 17 carriers of Vice Admiral Mitcher’s Task Force 38 commenced strikes on Okinawa and along the Ryukyu Island Chain on 10 October 1944 as part of a diversionary effort before the commencement of the landings at Leyte in the Philippines, scheduled for 20 October. The carriers then swiftly attacked targets on the island of Luzon in the Philippines before concentrating on the primary target, the Japanese airfields on the island of Formosa (present-day Taiwan), starting on 12 October with about 1,400 aircraft sorties.

The onset of the attacks caught the commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, attempting to return to Japan from an inspection visit to the Philippines (which Japanese intelligence had correctly determined to be the area of the next major U.S. landings). As a result of having repeatedly to take shelter from U.S. attacks, Toyoda was effectively out of communication and unable to command and control the battle, ceding that authority to his chief of staff, Vice Admiral Ryunosuke Kusaka. In response to the U.S. carrier strikes, Kusaka made the decision to initiate an “air only” component of the Sho plan, a decision that proved gravely premature.

Following the heavy Japanese air losses in the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, the Japanese had carefully kept most of their remaining aircraft out of battle, husbanding them for use in what they anticipated would be a U.S. invasion of the Philippines. At the same time, the Japanese were engaged in a massive effort to hastily train a new cadre of carrier pilots. U.S. naval intelligence correctly assessed that these new pilots and new planes (and three new aircraft carriers nearing completion) would not be ready before the spring of 1945, leading to an erroneous assessment that the Japanese would not commit their inadequately trained pilots (nor their current mostly empty-deck carriers) to a major battle before then. However, Kusaka committed the planes to battle in an “air only” response to Halsey’s strikes. The result was a slaughter of hundreds of Japanese planes and pilots, on par with the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” before they ever had a chance to intervene in the U.S. invasion of the Philippines. As a result, the surviving Japanese aircraft in the Philippines would only be able to attack U.S. forces or provide cover to Japanese surface forces, but not both. This would have profound effect on the outcome of the subsequent Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Despite staggering losses to U.S. fighters and dense anti-aircraft fire, some Japanese aircraft managed to get through to hit U.S. ships. At dusk on 13 October, a Japanese twin-engine Betty bomber dropped a torpedo that narrowly missed carrier Franklin (CV-13), thanks to great ship handling by Franklin’s commanding officer (Captain Shoemaker), and another passed under her stern without exploding. However, the pilot of the crippled Betty crashed into Franklin’s flight deck, fortunately at an angle at which the plane slid across the flight deck into the water with only minor damage to the ship. At about the same time, carriers Lexington (CV-16) and Wasp (CV-18) barely avoided being hit by Japanese aircraft. Hornet (CV-12) narrowly dodged an air-dropped torpedo, which then proceeded to hit the heavy cruiser Canberra (CA-70) causing grave damage as it hit below the ship’s armor belt in her engineering spaces, killing 23 men and causing the ship to go dead in the water. Despite the proximity to Japanese land-based aircraft and the continuing air attacks, Admiral Halsey made the bold decision to tow the Canberra rather than scuttle her. The tow of Canberra, initially by the heavy cruiser Wichita (CA-45) is an epic tale of damage control in itself.

On the evening of 14 October, another heavy Japanese air attack succeeded in putting a torpedo into the light cruiser Houston (CA-81), damaging her even more severely than Canberra the previous day and leaving her crippled without propulsion as well. Her skipper initially ordered abandon ship, but then countermanded the order, commencing one of the great damage-control efforts in the history of the U.S. Navy. Halsey again boldly decided to tow Houston also, and two light cruisers and eight destroyers were detached to escort the two damaged cruisers. The force became known as “CRIPDIV 1” (Cripple Division 1). Halsey also detached two light carriers, two cruisers, and four destroyers to provide a covering force to CRIPDIV 1, while he moved the rest of his carriers away from Formosa.

Halsey’s intent was to bait the Japanese (hence the alternate name of the Canberra/Houston group, “BAITDIV 1”) into sending out a surface force to finish off the cripples, and it almost worked. A Japanese force (the Fifth Fleet), consisting of two heavy cruisers and escorting destroyers sortied from Japan. However the force commander, Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima, quickly concluded that the wildly inflated claims by Japanese pilots of U.S. ships sunk were exactly that, wildly inflated; he opted not to be stupid and returned to the Japanese Inland Sea.

Japanese planes, on the other hand, took the bait, and a 107-plane strike was decimated by U.S. fighters and shipboard anti-aircraft fire, but three penetrated the CRIPDIV 1’s screen. Houston’s 5-inch guns were out of action due to loss of power, but the ship put up a massive barrage of 40-mm and 20-mm fire in manual control. Nevertheless, one Japanese plane succeeded in putting yet another torpedo into Houston, this time from dead astern, flooding the scout plane hangar. Despite the grave situation (Houston had 6,300 tons of water on board by then, a degree of flooding beyond which no U.S. cruiser had previously survived), the fleet tug Pawnee never slacked the tow and sent a visual signal that Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison rightly said deserves a place among the Navy’s historic phrases, “We’ll stand by you!”

Ultimately, both Canberra and Houston survived. Houston’s damage would not be repaired until just before the war ended, and she was scrapped in 1947, years before her time. Canberra returned to the fight at the end of the war, and in 1956 would be converted to the U.S. Navy’s second guided-missile cruiser. She would serve with distinction off Vietnam before being decommissioned in 1970. (As an aside, on 6 April 1967, Canberra sailor Doug Hegdahl was accidentally blown overboard by a 5-inch gun blast. He thus became the only U.S. Navy enlisted man to be captured by the North Vietnamese. He played dumb and was known to the North Vietnamese as the “Incredibly Stupid One,” while he memorized the names, dates of capture, circumstances of capture, and other personal information of over 250 other U.S. POWs. Ordered by senior POWs to accept early release so that he could take this critical information back to the United States, Hegdahl provided U.S. authorities with the first ground-truth accounting of the condition of U.S. POWs in North Vietnam, as well as proof that they were being tortured.)

Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23–26 October 1944: U.S. and Japanese Forces

U.S. Forces

The U.S. Navy forces in the Battle of Leyte Gulf were divided into two major elements reporting to two separate theaters of command. The Seventh Fleet was under the command of Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid and reported to General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the Southwest Pacific Area. The Seventh fleet had provided direct support to MacArthur’s advance along the north coast of New Guinea and was intended to provide direct support to MacArthur’s landing at Leyte. The Seventh Fleet forces included six older U.S. battleships. Five were survivors of the attack on Pearl Harbor: California (BB-44) and West Virginia (BB-48) had been sunk at Pearl Harbor, raised, repaired, and modernized; Pennsylvania (BB-38), Maryland (BB-46), and Tennessee (BB-43) had been damaged in the attack. Mississippi (BB-41), which had been on the U.S. East Coast, rounded out Kinkaid’s battleship force. Kinkaid also had 18 escort carriers divided into three groups (radio call signs “Taffy 1,” “2,” and “3”) to provide air support (with about 450 aircraft) to forces ashore and defense of the amphibious and transport forces. Moreover, Kinkaid’s force included several Royal Australian Navy ships, notably the heavy cruiser HMAS Australia.

The U.S. Third Fleet was commanded by Admiral William F. Halsey (embarked on the new fast battleship New Jersey—CV-62), who reported to Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander in chief of the Pacific Ocean Area (Central Pacific) and U.S. Pacific Fleet. The ships of the Third Fleet were the same as those of the Fifth Fleet, but changed fleet designators when Halsey relieved Admiral Spruance after the completion of Operation Forager (invasion of the Marianas and western Carolines), and Spruance and his staff began planning for the invasion of Okinawa. This change of designation confused Japanese naval Intelligence for about a week. The major element of the Third Fleet was the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 38, formerly TF 58) still under the command of Vice Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher, and consisting of four carrier task groups with 17 aircraft carriers: eight new Essex-class fleet carriers, plus Enterprise (CV-6) and eight Independence-class light carriers. The task groups also included 6 newer fast battleships—including Iowa (BB-61) and New Jersey—and (initially) 4 heavy cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and about 60 destroyers and destroyer escorts. Halsey’s task was to provide air cover and support to the Seventh Fleet and the Leyte landings, but his orders from Nimitz gave him the latitude to pursue and engage major elements of the Japanese fleet if the opportunity arose.

The divided U.S. command would be a major negative factor in the outcome of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, particularly General MacArthur’s orders that all Seventh Fleet communications first had to go up the Southwest Pacific Area chain of command before going to Nimitz and Halsey. This would result in major communications delays at critical points of the battle. At some key points, Halsey and Kinkaid only knew what the other was doing by essentially intercepting each others’ communications, which also resulted in delay, confusion, and faulty assumptions—and a potentially disastrous outcome for the Leyte transport and supply force.

Japanese Forces

During 1944, and accelerating after the U.S. captured the Marianas Islands, the Japanese had developed a series of contingency plans for a decisive battle to defend the Japanese homeland. The plans were termed Sho (“Victory”) Go (“Operation”). Sho Ichi Go was Victory Operation 1 (or Sho 1) and was the defense of the Philippines. Sho 2 was defense of Formosa. Sho 3 was defense of the Ryukyus and Okinawa, and Sho 4 was the defense of northern Japan and the Kuriles. As early as July 1944, the Japanese assessed that the Philippines would be the next major U.S. objective, even before this had been officially decided by the American leadership. The Japanese also correctly assessed that the first objective would be Leyte. (The objective was initially Mindanao until a series of U.S. carrier strikes on that island convinced Admiral Halsey that Japanese strength there was weak; he recommended Mindanao be bypassed and that the timetable for the Leyte invasion be moved up by over a month to mid-October, which was sooner than the Japanese expected.)

The Japanese Combined Fleet was under the command of Admiral Soemu Toyoda (replacing Admiral Mineichi Koga, lost in a plane crash in March 1944), who moved ashore in Japan from his flagship, light cruiser Oyodo, before the battle so that he could have better communications capability to command the battle. As it turned out, he was away from his headquarters (to buck up the morale of Japanese forces in the Philippines) at a critical decision point in the lead-up to the battle, with severe adverse consequences for the Japanese. (Sometimes, “managing by walking around” or “going out to the field” is not the right answer.) Toyoda was roughly Nimitz’ opposite number.

The First Mobile Fleet (actually intended by the Japanese as a decoy force) was referred to as the “Main Body” in Japanese communications (confusing U.S. commanders). It was usually referred to as the “Northern Force” or “Carrier Force” in many accounts. The fleet was under the command of Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, the senior Japanese commander in tactical command of the battle. This force was essentially what remained of the First Mobile Fleet after the Battle of the Philippine Sea. It included the fleet carrier Zuikaku (last surviving carrier of the Pearl Harbor strike force), the light carrier Zuiho, and the converted seaplane tenders Chitose and Chiyoda, with only about 110 aircraft between all four carriers. Added to the force were the recently converted “hybrid” battleships Ise and Hyuga, each of which had their aft two main battery turrets replaced with a flight deck, but which deployed without aircraft. Three light cruisers and nine destroyers provided escort. Departing from Japan, the purpose of this force was to sacrifice itself in order to draw the carriers of Halsey’s Third Fleet away from the Leyte area to give Vice Admiral Kurita’s battleship force the chance to get into Leyte Gulf via the Sibuyan Sea and San Bernardino Strait.

The “First Diversion Strike Force,” (actually intended by the Japanese as the primary strike force) was usually referred to as the “Center Force,” “First Striking Force,” “Force A,” or “Kuritas’s Force” in many accounts. Under the command of Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, this force initially consisted of 7 battleships, 11 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and escorting destroyers, which were based near Singapore to be near fuel supplies (which were already severely depleted in Japan due to submarine attacks on tankers). Upon indication of the Allied invasion of Leyte, this force moved to Brunei, took on fuel and divided into two parts. The major portion of the force remained under the command of Kurita, and included the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi (the largest in the world, with nine 18-inch guns), along with the battleships Nagato, Kongo and Haruna, 10 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 15 destroyers. The purpose of this force was to transit through the San Bernardino Strait and attack into the Leyte beachhead area from the north, and constituted the Japanese “main effort.”

The Japanese “Third Section” (a subset of the First Diversion Strike Force) is usually referred to as the “Southern Force” in many accounts. Under the command of Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura, this force detached from Kurita’s force at Brunei, and consisted of the old battleships Fuso and Yamashiro, the heavy cruiser Mogami, and four destroyers. The purpose of this force was to transit the Sulu Sea and attempt to enter Leyte Gulf from the south via Surigao Strait with the intention of sacrificing itself to draw the major elements of Admiral Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet to the south side of Leyte Gulf in order to open an avenue of approach to Kurita’s force from the north.

The “Second Diversion Strike Force” was a separate force often lumped together with the “Southern Force,” sometimes referred to as the Second Striking Force. Under the command of Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima, this force consisted of the heavy cruisers Nachi and Ashigara, a light cruiser, and four destroyers. Originally, the Japanese Fifth Fleet (responsible for defending northern Japan), it was brought south, receiving various changed and contradictory orders, before ultimately trying to enter Surigao Strait shortly after Nishimura’s force. (Nishimura and Shima were aware of each other’s presence, but did not coordinate their attack.)

Japanese command, control, and communications were even more messed up than those on the U.S. side. Although Ozawa was the senior Japanese commander, neither Ozawa nor Kurita ever really knew what the other was doing due to missed and delayed message traffic. In addition, once Nishimura was detached from Kurita’s force, he was essentially on his own. Although Shima was slightly senior to Nishimura, he did not attempt to take command, and Nishimura, for tactical reasons, did not slow down for Shima’s force to catch up (although Shima closed the gap as best he could), resulting in a piecemeal attack into the Surigao Strait by the two forces. Communications and coordination between the Japanese fleets and land-based navy and army air forces was essentially non-existent, with the result that Kurita, Nishimura, and Shima’s forces were completely devoid of air cover throughout (except by a few of their own embarked floatplane scouts, which were actually used effectively by Nishimura’s force).

The Invasion of Leyte, 20 October 1944

At 0800 on 17 October 1944, the light cruiser Denver (CL-58) was the first to open fire on a Japanese-held island at the entrance to Leyte Gulf in support of a U.S. Army Ranger operation to seize Japanese-held islands covering the approaches to Leyte. This was followed by minesweeping operations and, on 18 October, the battleship Pennsylvania and two cruisers commenced bombardment of the southern Leyte beaches. The destroyer-transport Goldsborough (APD-32) was damaged by shore fire, but otherwise initial Japanese resistance was relatively light, and most of the Japanese ground troops on the island were out of position (and about to be overwhelmed by the massive force about to be put ashore by ships of the U.S. Navy, ultimately about 200,000 U.S. Army troops).

However, just after midnight on 19 October, the destroyer Ross (DD-563) was covering the minesweepers when she struck a mine in the swept channel, and then struck a second mine. Although badly damaged, with 23 of her crew killed, Ross gained the distinction as the only destroyer in the Pacific to survive hitting two mines in quick succession.

On 20 October, the main U.S. invasion fleet entered Leyte Gulf and commenced the amphibious assault by General Douglas MacArthur’s Sixth Army on the designated northern and southern beaches, fulfilling MacArthur’s vow (“I shall return!”) that he made when he was ordered out of the Philippines in 1942. Compared to other island assaults, the Leyte landings were significantly less bloody, but the assault would soon bog down (in large part due to abysmal weather) and it would take a long time for the soggy airfield at Tacloban to become fully operational and enable land-based Army aircraft to take over from Navy aircraft carriers. By the time the island was finally secured, over 3,500 U.S. troops were killed, making it one of the more costly battles in the Pacific War.

It didn’t take long for Japanese air counterattacks to commence, although the reduced number of aircraft available to defend the Philippines (thanks to Halsey’s strikes on Okinawa, Luzon, and Formosa) made them less effective than they might otherwise have been. Nevertheless, on the afternoon of the 20 October, a Japanese torpedo plane succeed in hitting the light cruiser Honolulu (CL-48) with one torpedo. Honolulu had been a lucky ship, going through multiple battles and even surviving two torpedo hits at the Battle of Kolombangara in 1943, all without losing a man. Her luck ran out. Although her skipper successfully maneuvered to avoid a hit in her vitals, 60 of her crew were killed, but the surviving crewmen saved their ship. Honolulu was then struck by a stray “friendly” anti-aircraft round that killed five more crewmen.

Japanese air attacks continued at first light on 21 October. A damaged Japanese aircraft deliberately crashed into the foremast of HMAS Australia, devastating the bridge with debris and flaming fuel oil, killing 30, including her captain, and wounding 61 more including the senior Australian officer present, Commodore John A. Collins (for whom the Australian Collins-class submarines currently in service are named). Some sources suggest this was the first kamikaze attack, although it appears to have been conducted on the pilot’s own initiative after his plane was damaged (as many had done before) and not the result of a pre-planned suicide mission. (In early January 1945, HMAS Australia would get hit by five actual kamikaze, and a bomb, and would keep fighting).

The Battle of Palawan Passage, 23–24 October 1944

U.S. submarines drew the first blood during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. At 0430 on 23 October, the submarine USS Bream (SS-243), commanded by Commander Wreford G. “Moon” Chapple, fired six torpedoes in a daring surface attack on the Japanese heavy cruiser Aoba, and hit with one, possibly two, severely damaging the ship. Aoba had been detached from Kurita’s force at Brunei, along with the light cruiser Kinu and a destroyer, to proceed ahead to Manila with the intent of forming the nucleus of a “Tokyo Express” force to get supplies and reinforcements to Leyte. Aoba was hit in the Number 2 engine room and took on a 13-degree list, but was successfully towed into Manila Bay. U.S. Navy codebreakers intercepted and decrypted Aoba’s damage report. The cruiser would be damaged again on 24 October by planes from Halsey’s carrier force, but would survive to be scuttled at Kure, Japan, in the last days of the war. (Chapple commanded three submarines on 14 war patrols, including the daring and frustrating action by S-38 in Lingayen Gulf in the opening days of the war—see H-Gram 003—and was awarded two Navy Crosses, three Silver Stars, and a Bronze Star during the war).

Shortly after midnight on 23 October 1944, the submarine USS Darter (SS-227), under Commander David H. McClintock, made radar contact on Kurita’s force of battleships and heavy cruisers transiting northeasterly of the west coast of Palawan Island off the northeast tip of Borneo (Kurita’s departure from Brunei was undetected by U.S. radio intelligence, either due to Japanese radio silence or due to cloud cover masking the activity from U.S. aircraft). Darter made the first of three vital contact reports, which alerted U.S. naval forces that Kurita was on the move. Japanese radiomen on Yamato also intercepted one of the urgent contact reports, giving Kurita indication he’d been detected.

Darter and her nearby cohort Dace (SS-247), commanded by Commander Bladen D. Claggett, moved to position themselves ahead of Kurita’s force for a submerged attack just before sunrise. After the Japanese force zigged toward Darter, at 0524, Darter fired six torpedoes at near point-blank range at the heavy cruiser Atago (Kurita’s flagship), at least four of which hit, causing the ship to rapidly sink in 18 minutes and take 360 of her crew to the bottom. At about 0534, Darter then fired her four stern tubes and hit the heavy cruiser Takao with two torpedoes, inflicting severe damage, which forced her to return to Brunei (the Japanese were unable to repair the damage for the duration of the war). Darter then survived a depth charging by Japanese destroyers.

At 0556, Dace hit the heavy cruiser Maya with four torpedoes, causing Maya to capsize in seven minutes along with 336 of her crew (amazingly, 769 of her crew were saved by destroyer Shimakaze, which came right alongside so crewmen could cross on ad hoc gangways).

Kurita was forced to swim for his life (and, unusual for a Japanese admiral, was one of the first off the ship) before being rescued by the destroyer Kishinami, transferring to the super-battleship Yamato, and resuming command of the force. However, Kurita had already lost 3 of his 10 heavy cruisers and 2 of his 15 destroyers (detached to escort the wounded Takao) to a devastating submarine attack. He now knew he had lost even the slim chance of achieving surprise, assuming correctly that he would soon be subject to large-scale carrier air attack, and also setting him several hours behind schedule.

As Darter and Dace stalked the damaged Takao later in the day, Darter ran hard aground Bombay Shoal. Dace rescued all of Darter’s crew and then attempted to scuttle her with shellfire and torpedoes, which hit the reef instead, after Darter’s own scuttling charges failed to sink her. Submarine Rock (SS-274) attempted to do the same with ten torpedoes, also unsuccessfully. Darter was then severely damaged by deck-gun shelling from submarine Nautilus (SS-168). Although Darter’s crew destroyed their code materials, the Japanese did salvage some useful documents and equipment. Darter’s skipper, Commander McClintock, and Dace’s skipper, Commander Claggett, would both be awarded the Navy Cross and both subs received the Navy Unit Commendation.

USS Tang (SS-306) Sunk by Own Torpedo, 23–24 October 1944

Medal of Honor Citation for Commander Richard “Dick” O’Kane

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of USS TANG operating against two Japanese convoys on 23 October and 24 October 1944, during her fifth and last war patrol. Boldly maneuvering on the surface into the midst of a heavily escorted convoy, CDR O’Kane stood in the fusillade of bullets and shells from all directions to launch smashing hits on 3 tankers, coolly swung his ship to fire at a freighter and, in a split second decision, shot out of the path of an onrushing transport, missing it by inches. Boxed in by blazing tankers, a freighter, transport and several destroyers, he blasted two of the targets with his remaining torpedoes and, with pyrotechnics bursting on all sides, cleared the area. Twenty-four hours later, he again made contact with a heavily escorted convoy steaming to support the Leyte campaign with reinforcements and supplies and with crated planes piled high on each unit. In defiance of the enemy’s relentless fire, he closed the concentration of ships and in quick succession sent 2 torpedoes into the first and second transports and an adjacent tanker, finding his mark with each torpedo in a series of violent explosions at less than 1,000 yards range. With ships bearing down on all sides, he charged the enemy at high speed, exploding the tanker in a burst of flame, smashing the transport dead in the water, and blasting the destroyer with a mighty roar which rocked Tang from stem to stern. Expending his last 2 torpedoes into the remnants of the once powerful convoy before his own ship went down, CDR O’Kane, aided by his gallant command, achieved an illustrious record of heroism in combat, enhancing the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

It should be noted that medal citations are written based on the information available at the time, so are not always completely accurate in terms of losses and damage to enemy forces (only the cargo ships Kogen Maru and Matsumoto Maru were sunk on the second night), although there is absolutely no doubt that O’Kane’s incredibly courageous surfaced attacks on two Japanese convoys on two successive nights in the Formosa Straits met the definition of “above and beyond the call of duty.” The citation also does not mention that at 0230 on 24 October 1944, Tang was sunk by a circular run of her own torpedo, a new Mark 18 electric torpedo that was the 24th of the 24 torpedoes aboard to be fired.

Tang lookouts immediately saw the last torpedo commence a circular run and, despite O’Kane’s attempts to evade, the torpedo struck amidships 20 seconds after being fired, sending the submarine 180 feet to the bottom. Nine officers and men were topside when the torpedo hit, but only three were rescued by the Japanese the next morning, including O’Kane. One other escaped via the conning tower before the sub went under, and was also picked up by the Japanese. About 30 crewmen in the forward part of the sub survived the sinking. Of those, 13 were known to have escaped using the Momsen Lung escape breathing apparatus (the only time this was known to have worked), but only five were picked up by the Japanese. The nine survivors were severely beaten by the Japanese crewmen aboard the frigate CD-34, who had suffered their own severe losses at the hands of Tang. O’Kane and eight others were secretly held captive by the Japanese, but survived the war; 78 of Tang’s crew perished.

Commander Richard O’Kane would be awarded the Medal of Honor, three Navy Crosses, three Silver Stars, a Legion of Merit with Combat V, and a Purple Heart for his actions in command of Tang and as executive officer of USS Wahoo (SS-238), under Lieutenant Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton. Tang would be awarded two Presidential Unit Citations and four battle stars, one of the citations for rescuing 22 downed U.S. aviators off Truk. Claims for Japanese ships and tonnage sunk by submarines during the war were subject to considerable revision based on post-war analysis of records, usually downward. O’Kane would be the only one of the top-scoring skippers ultimately to be given credit for more ships sunk than he actually claimed.

During the war, Tang was credited with sinking 31 ships of 227,800 tons during her five war patrols, making her the most successful U.S. submarine of the war in terms of numbers and tonnage. After the war, the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) reduced this to 24 ships and 93,824 tons, which made Tang second in numbers (behind Tautog—SS-199—with 26) and fourth in tonnage behind Flasher (SS-249), Rasher (SS-269), and Barb (SS-220). Subsequent analysis then revised Tang’s total to 33 ships and 116,454 tons, once again placing the boat first in both categories. Throughout, Tang retained the record for number of ships sunk on a single patrol (ten on the third war patrol, in the Yellow Sea; O’Kane had claimed only eight). In ten war patrols (five on Tang and five on Wahoo), O’Kane had a hand in more successful attacks than any other U.S. submarine officer.

Greatest U.S. Navy Ace: Commander David McCampbell, 24 October 1944

Medal of Honor Citation for Commander David McCampbell

“The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Commander David McCampbell for service as set forward in the following citation; For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commander Air Group Fifteen, during combat against enemy Japanese aerial forces in the First and Second Battles of the Philippine Sea. An inspiring leader, fighting boldly in the face of terrific odds, Commander McCampbell led his fighter planes against a force of eighty Japanese carrier-based aircraft bearing down on our fleet on June 19, 1944. Striking fiercely in valiant defense of our surface forces, he personally destroyed seven hostile planes during a single engagement in which the outnumbering force was utterly routed and virtually annihilated. During a major Fleet engagement with the enemy on October 24, Commander McCampbell, assisted by but one plane, intercepted and daringly attacked a formation of sixty land-based craft approaching our forces. Fighting desperately but with superb skill against such overwhelming airpower, he shot down nine Japanese planes and, completely disorganizing the enemy group, forced the remainder to abandon the attack before a single aircraft could reach the fleet. His great personal valor and indomitable spirit of aggression under extremely perilous combat conditions reflect the highest credit upon Commander McCampbell and the United States Naval Service.”

On the morning of 24 October 1944, Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi, commander of land-based Japanese naval aircraft ashore in the Philippines (mostly on Luzon) launched three waves of aircraft of about 50–60 planes each at U.S. carriers operating east of Luzon, with Task Group 38.3 under Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman as the closest target. At 0950 on 24 October, a large flight of Japanese land-based aircraft was detected on radar approaching the U.S. carriers. Many of the carriers’ aircraft were already airborne on the way to Luzon to attack airfields, leaving a reduced number of fighters for fleet defense. The USS Essex (CV-9) quickly scrambled six F6F Hellcat fighters as the Japanese approached to 22 nautical miles from the carriers. Several of the fighters, including one flown by the air group commander, David McCampbell, were launched without a full load of fuel. The flight was directed by the Essex fighter direction officer, Lieutenant John Connally, Jr. (future Secretary of the Navy, governor of Texas, and wounded in the same car when President Kennedy was assassinated).

McCampbell and his wingman, Lieutenant (j.g.) Roy Rushing, became separated from the other four aircraft and engaged a large number of fighters by themselves. These turned out to be a highly unusual mix of Japanese army and navy aircraft, which actually turned away when challenged (it’s also possible the fighters were all Japanese navy and the “army” planes were misidentified). McCampbell and Rushing pursued the Japanese, with McCampbell shooting down nine and Rushing six. McCampbell’s tally of five A6M Zekes, two A6M3 Hamps, and two Army Ki-43 Oscars is the all-time single-sortie record for any U.S. pilot. When McCampbell recovered on the light carrier USS Langley (CVL-27), his plane had two rounds left and ran out of fuel while still hooked to the wire.

McCampbell (USNA ’33), who was the naval aviation gunnery champion in 1940 and had survived the sinking of the aircraft carrier Wasp (CV-7) in September 1942, thus became the only U.S. aviator to achieve “ace-in-a-day” status twice (he’d shot down seven planes in two sorties on the same day during the “Marianas Turkey Shoot” in June 1944). McCampbell would finish the war with 34 kills in the air (and 20 more on the ground), making him the third-highest U.S. ace of all time, and the leading Navy ace. (He was also the highest-scoring U.S. ace to survive the war). McCampbell would be awarded a Medal of Honor (the only carrier aviator to receive one in World War II), a Navy Cross, and a Legion of Merit with Combat V. McCampbell’s Air Group 15 (CAG 15) destroyed more aircraft in the air (315) and on the ground (348) than any other carrier air group. Arleigh Burke–class DDG-85, commissioned in 2002, is named in McCampbell’s honor.

USS Princeton (CVL-23) Lost to Japanese Air Attack, 24 October 1944

Despite the large number of attacking Japanese aircraft, all were shot down, forced to turn away, missed, or failed to find the U.S. carriers east of Luzon, except for one plane. At 0938, a Japanese D4Y3 Judy dive bomber hit the light carrier Princeton (CVL-23) with one 550-pound armor-piercing bomb, causing a severe fire in the hangar bay and multiple secondary explosions. As the fires spread, most of the crew was evacuated, while damage-control teams continued to fight the fires, gradually regaining the upper hand. However, at 1523 a massive secondary explosion, probably in the after bomb stowage, devastated Princeton and the light cruiser Birmingham (CL-62), which was alongside helping to fight the fires. The carnage on Birmingham was brutal, as many of the crew were topside manning hoses. Of these, 233 were killed and 426 wounded, and Birmingham was forced to withdraw from the battle. Another light cruiser and two destroyers were also damaged by the force of the blast. (Birmingham’s skipper, Captain Thomas B. Inglis, was awarded a Navy Cross for his courage, and would later become director of naval intelligence (1945–49) and retire as a vice admiral). Even so, the burning Princeton refused to sink and had to be scuttled at 1750 by torpedoes from the light cruiser USS Reno (CL-96). Princeton lost 108 of her crew, but 1,361 were rescued. The carrier was the largest U.S. ship lost during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, 24 October 1944

On the morning of 24 October 1944, three of Halsey’s four carrier task groups were operating east of the northern Philippines (the fourth was en route Ulithi Atoll for refueling), when Kurita’s force was spotted transiting easterly in the Sibuyan Sea en route San Bernardino Strait. Ozawa’s decoy carrier force had yet to be spotted, despite its deliberate efforts to be detected, deliberately breaking radio silence with messages that for some reason U.S. radio intelligence failed to intercept. The U.S. carriers quickly began launching waves of air strikes at Kurita’s force. Of note, after the Battle of the Philippine Sea, the Japanese invested heavily in increasing the number and capability of anti-aircraft weapons on their ships (including battleship main-battery special shells which worked a bit like a giant shot-gun burst). The greatly enhanced AAA capability would do them little good.

At 1030, planes from Intrepid (CV-11) and Cabot (CVL-28) struck first, damaging the battleships Yamato, Musashi, and Nagato (which all kept on steaming) and so badly damaging the heavy cruiser Myoko with a torpedo that she was forced to withdraw (and was never fully repaired). A second wave from Intrepid, Essex, and Lexington (CV-16) then struck, with most hits (about ten) being scored on Musashi. A third wave from Enterprise and Franklin (CV-13) hit super-battleship Musashi with 11 bombs and 8 torpedoes. Musashi absorbed at least 17 bombs and 19 torpedoes before she finally capsized and sank at about 1930, taking 1,023 of her 2,399 crewmen to the bottom, including 143 survivors of the previously sunk heavy cruiser Maya. The U.S. Third Fleet carriers flew 259 sorties by dive and torpedo bombers against Kurita’s force, but each wave kept attacking the same ship (Musashi) over and over again. The loss of Musashi, the pride of the Japanese navy, was a serious psychological blow to Kurita and other Japanese who witnessed it. Eighteen U.S. Navy aircraft were lost in the attacks.

At about 1600, Kurita reversed course to the west. This course change, coupled with inflated pilot reports about how many Japanese ships had been sunk or damaged convinced Halsey that Kurita’s force was beaten and retreating. Thus, he could conceivably send his carriers and battleships against Ozawa’s carrier (decoy) force, which had finally been sighted northeast of Luzon at about 1640 on 24 October. Kurita’s course change, however, was temporary, and, at 1715, he resumed course toward San Bernardino Strait with his four still-battle-worthy battleships. When Kurita first reported his course change to the west, it provoked a “flaming” message (Operations Order No. 372) from Combined Fleet Commander Admiral Toyoda: “With confidence in heavenly guidance, the entire force will attack!” Due to communications delays, Kurita had already turned back toward the east before he received this rebuke from the fleet commander.

USS Tang (SS-306): The submarine's commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander Richard H. O'Kane (center), poses with the 22 aircrewmen that Tang rescued off Truk during the carrier air raids there on 29 April–1 May 1944. The photograph was taken upon Tang's return to Pearl Harbor from her second war patrol, in May 1944 (80-G-227987).

Air Strikes in the Sulu Sea, 24 October 1944

With the reports from the submarines confirming that Kurita’s battleship force was on the move, the aircraft carriers of TG 38.4, Enterprise and Franklin, launched reinforced search-strike packages commencing at 0600 to cover the Sulu Sea and the approaches to the southern entrance to Surigao Strait. U.S. naval intelligence was aware that Vice Admiral Shima’s force of two heavy cruisers (the Second Diversion Strike Force) was on the move, but the orders Shima received were so vague and contradictory that even he didn’t know what he was supposed to do, and ultimately decided on his own to head for Surigao Strait. What the Americans did not know was that Kurita had detached the two battleships Fuso and Yamashiro, under Vice Admiral Nishimura, to make an attack into Leyte Gulf via Surigao Strait (the orders were hand-delivered, so there was no radio intercept).

Shima was slightly senior to Nishimura, but did not attempt to take charge or combine the two forces. This would have required Nishimura to slow down and arrive too late in Surigao Strait to support the planned attack by Kurita from the north via San Bernardino Strait into Leyte Gulf. (As it turned out, Kurita’s attack would be delayed as a result of the air strikes on his force in the Sibuyan Sea, but Nishimura opted to keep to the timetable rather than delay and be forced to try to fight through the strait in daylight.) Shima would ultimately boost speed to close the gap with Nishimura, arriving at Surigao Strait about 45 minutes after Nishimura.

The scout/strike force from Franklin sighted and attacked three Japanese destroyers (this force had been detached from Shima’s group in order to take aviation personnel and equipment to Leyte). The destroyers skillfully avoided numerous bombs until finally Wakaba was hit. The other two destroyers took a risk and succeeded in rescuing most of Wakaba’s crew before she went down. However, a following scout/strike from Intrepid damaged HATSUSHIMA, and the two surviving destroyers reversed course toward Manila (without notifying Shima, who kept hoping they would join up).

As Franklin’s planes were expending numerous bombs on the destroyer group, the scout/strike package from Enterprise sighted Nishimura’s force and attacked, with somewhat better aim. Nishimura’s flagship, battleship Yamashiro, experienced numerous near misses. About 20 crewmen were killed by strafing and rocket hits, but she was not significantly damaged. Battleship Fuso, on the other hand, suffered a direct bomb hit beside the Number 2 twin 14-inch gun turret and sprang leaks in the hull that could not be closed (and seawater had to continuously be pumped out for the remainder of the battle). Another bomb hit the quarterdeck, destroying both of Fuso’s floatplanes and starting an aviation gasoline fire, that as it turned out looked worse than it was. The heavy cruiser Mogami and several of the escorting destroyers were damaged by strafing (destroyer Shigure may also have been hit by a bomb), but after the attack was over, the entire force resumed course and speed en route Surigao Strait.

The commander of Fighter Squadron 20 (VF-20), Commander Fred Bakutis, was shot down after making repeated rocket strafing runs; he survived seven days adrift in the Sulu Sea before being rescued by submarine Hardhead (SS-365), was awarded a Navy Cross for leading the strike and went on to be a rear admiral). There were no follow-up strikes on Nishimura’s group, as Admiral Halsey had directed all of his carrier groups to start transiting north toward the Japanese carrier force. Reporting by U.S. scout aircraft on Nishimura and Shima’s forces became seriously garbled to the point that the commander of the Seventh Fleet, Vice Admiral Kinkaid, thought as many as four or more Japanese battleships were heading toward Surigao Strait.

Sinking of “Hell Ship” Arisan Maru—Greatest Loss of U.S. Life at Sea—24 October 1944

On 21 October 1944, the Japanese cargo ship Arisan Maru departed Manila with 1,781 Allied prisoners of war, almost all American, crammed aboard in unbelievably appalling conditions (hence the term “hell ships” used to describe Japanese ships engaged in transporting Allied POWs). Arisan Maru was initially part of a 13-ship convoy with three escorting destroyers. On the late afternoon of 23 October, the convoy was ordered to scatter when it detected signs that it was being stalked by a U.S. submarine wolfpack (Seadragon—SS-194), Blackfish—SS-221, and Shark—SS-314). As the slowest ship in the convoy (7 knots), Arisan Maru fell behind.

At 1700 24 October, Arisan Maru was struck by a torpedo from Shark, and took until about 1940 to sink. As Arisan Maru was sinking, the Japanese destroyers Take and Harukaze attacked and sank the Shark (with all 87 hands) and then returned to the Arisan Maru, rescuing 347 Japanese survivors, but taking aboard none of the POWs (all of whom had survived the torpedo strike, although several had already died aboard the ship due to sickness). Five of the POWs were able to reach China in a lifeboat. Four other POWs were later picked up by other Japanese ships; one of these died after being put ashore.

It is estimated that more than 20,000 Allied POWs were killed when the ships they were aboard were torpedoed and sunk by Allied submarines or bombed by aircraft. In many cases, POWs who survived the sinking were machine-gunned in the water by the Japanese, or left to die, and many died aboard the ships even before they were hit. Although U.S. naval intelligence knew the Japanese were transporting POWs by sea on cargo ships, it was not readily apparent which ones were transporting POWs, as the ships were not marked in any way different than other cargo vessels.

The greatest loss of POWs in a single sinking was the Junyo Maru, sunk by the British submarine HMS Tradewind on 18 September 1944; about 5,600 Dutch POWs and Javanese slave laborers died. Other major “hell ship” losses included Montevideo Maru sunk by USS Sturgeon (SS-187) on 1 July 1942 (1,054 Australian POWs died); Lisbon Maru sunk by USS Grouper (SS-214) on 1 October 1942 (800 British POWs died); Suez Maru sunk by USS Bonefish (SS-223) on 25 November 1943 (548 British and Dutch POWs died).; Shinyo Maru sunk by USS Paddle (SS-263) on 7 September 1944 (687 U.S., Dutch, and Filipino POWs died); Rakuyo Maru sunk by USS Sealion (SS-195) on 12 September 1944 (1,159 British and Australian POWs died); Kachidoki Maru sunk by USS Pampanito (SS-383) also on 12 September 1944 (431 British POWs died); Oryoku Maru sunk by U.S. airstrikes on 13 December 1944 (about 270 mostly U.S. POWs died); Enoura Maru bombed by U.S. Navy aircraft from USS Hornet (CV-12) on 9 January 1945 (350 Allied POWs died).

The Battle of Surigao Strait: Last Battleship Versus Battleship Action, 25 October 1944

With warning from the U.S. airstrikes in the Sulu Sea, the commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, Vice Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, had ample time to set up a blocking force at the northern exit from Surigao Strait to keep Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura’s “Southern” force from forcing its way into Leyte Gulf. Kinkaid assigned the task to Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf, commander of Fire Support Unit South. Oldendorf then consolidated the battleships and most of the cruisers and destroyers of the Southern and Northern Fire Support Groups. (The light cruiser Nashville—CL-43—was held back from the battle because General Douglas MacArthur was still embarked. Although MacArthur was eager to ride her into battle, Kinkaid and Oldendorf thought better of it, and assigned her to cover the beachhead area).

Six pre-war battleships (West Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania), four heavy cruisers (Oldendorf’s flagship Louisville—CA-28, Portland—CA-33, Minneapolis—CA-36, and HMAS Shropshire), and four light cruisers (Denver—CL-58, Columbia—CL-56, Phoenix—CL-46, and Boise—CL-47), plus 28 destroyers and 39 PT-boats were arrayed to meet the Japanese force. They were deployed in such a manner that Nishimura’s force would have to run a 50-mile gauntlet of PT boats, destroyers, and cruisers before it even reached the U.S. battle line.

Two of Oldendorf’s battleships, West Virginia and California, had been sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor, then raised and modernized. Maryland, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania had been damaged at Pearl Harbor, repaired and modernized. The cruisers Portland, Minneapolis, and Boise had all been severely damaged early in the war, but had survived and been repaired due to America’s enormous industrial might.

Many accounts inaccurately describe Nishimura as blundering in to an American trap, and he has been often characterized as inept or foolhardy, or deceived into thinking that no U.S. force was waiting for him. Actually, Nishimura knew full well what he was facing—his catapult-launched scout planes had actually served him well. He knew he was on a sacrificial mission (described in Japanese sources as “special attack,” the same terminology used for kamikaze aircraft). His mission was to draw the American forces to the southern side of Leyte Gulf, to clear a path for Kurita’s force to enter from the north. According to the original plan, Nishimura was to enter Leyte Gulf from the south, via Surigao Strait, at the same time as Kurita came in from the north (which might give him some chance of survival), but once he learned that Kurita had been delayed by U.S. Navy airstrikes in the Sibuyan Sea on 24 October 1944, he knew there was no hope. However, he knew his duty was to proceed. In an irony of fate, Surigao Strait was where Nishimura’s only son had been killed in a plane crash early in the war.

As Nishimura approached the southern end of Surigao Strait after darkness fell, fully expecting to be ambushed by the Americans, he sent the heavy cruiser Mogami and three of his four destroyers ahead to scout a bay that was a likely place for U.S. ships to be waiting, while the battleships Yamashiro and Fuso trailed some distance behind. As it turned out, no U.S. ships were there, and waiting U.S. PT boats missed Mogami and destroyers as they went by in the darkness before then detecting trailing Yamashiro and Fuso at 2236. PT-131 commenced the first attack, but Japanese night tactics against PT boats and defensive fire were very effective, driving the initial attacks off. At roughly the same time, Mogami and the battleships linked back up, but in the darkness and confusion, one of Fuso’s secondary battery guns opened fire and hit Mogami with the first round. For the next three hours, the Japanese force fought off one wave of U.S. PT boats after another, damaging ten (one of which was run aground to prevent sinking, but later sank), but receiving no significant damage in return. Nishimura’s force entered the southern end of Surigao Strait at about 0200.

At 0300, Nishimura’s luck ran out. Captain Jesse B. Coward, commander of Destroyer Squadron 54, had deployed each of his two destroyer divisions on opposite sides of the strait, with flagship Remey (DD-688), McGowan (DD-678), and Melvin (DD-680) on the east side. McDermut (DD-677) and Monssen (DD-798) hugged the shoreline on the west side, both on a reciprocal course to the Japanese, which had first been detected by McGowan’s SG radar at 0238 at a range of 39,700 yards. Having learned the lessons of previous battles, the U.S. destroyers did not open fire with guns until after the torpedoes were well on their way. Coward’s eastern group of destroyers launched 27 torpedoes about 30 seconds after 0300. The Japanese opened fire on the eastern destroyers at 0301, straddling them and forcing them to turn away without firing their guns. The western two destroyers launched 20 torpedoes at about 0310, the two groups catching the Japanese in a crossfire. The result was devastating.

Two torpedoes from Melvin struck Fuso, inflicting serious damage to the old ship, and she fell out of line (in the ensuing confusion, Nishimura never knew Fuso was no longer following behind). At 0320, the torpedoes from McDermut and MONSSEN arrived. One torpedo from Monssen hit Yamashiro, with less damage than on Fuso, and Yamashiro plowed on with Mogami closing up behind her. At the same time, two torpedoes from McDermut hit the destroyer Yamagumo, which then blew up with all hands. Another McDermut torpedo hit the destroyer Asagumo, blowing off her bow and inflicting severe damage that would subsequently prove fatal, and knocking her out of action. At least one more McDermut torpedo hit the destroyer Michishio, which began to sink. Several torpedoes appeared to pass under Shigure (the luckiest ship in the Imperial Japanese Navy) without exploding. With his torpedo salvos, Captain Coward had hit both battleships and taken Fuso and three of the four Japanese destroyers out of the battle. (Coward would be awarded a Navy Cross—his second—and criticized by the Naval War College for taking a bad angle shot).

Then, Destroyer Squadron 24, under the command of Captain Kenmore M. McManes, commenced a torpedo attack at 0330 from the western flank in two sections. The first section was flagship Hutchins (DD-476), Daly (DD-519), and Bache (DD-470), and the second was led by HMAS Arunta, followed by Killen (DD-593) and Beale (DD-471). The explosion of Yamagumo from McDermut’s torpedo lit the scene. Shigure dodged four torpedoes from Arunta. One torpedo from Killen hit battleship Yamashiro (her second torpedo hit), causing Nishimura to issue a “general attack” order—i.e., all ships attack independently. More torpedoes hit the sinking Michishio, hastening her demise. Daly dodged torpedoes fired from either Mogami or one of the Japanese destroyers, and other destroyers in the group experienced near misses from Japanese return fire. McManes would also be awarded a Navy Cross.

Subsequently, Destroyer Squadron 56, commanded by Captain Roland M. Smoot, attacked in three sections. Section 1 was Albert W. Grant (DD-649), Richard P. Leary (DD-664), and flagship Newcomb (DD-586). Section 2 was Bryant (DD-665), Halford (DD-480), and Robinson (DD-562). Future CNO Lieutenant Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., was the evaluator in the combat information center on Robinson and would be awarded a Bronze Star with Combat V. Section 3 was Bennion (DD-662), Leutze (DD-481), and Heywood L. Edwards (DD-663). Future CNO Lieutenant (j.g.) James L. Holloway III was the gunnery officer on Bennion (in his second week on board) and would also be awarded a Bronze Star with Combat V. By this time, Yamashiro had shaken off the second torpedo hit and resumed her forward advance with the so-far undamaged Mogami. Shigure doubled back to look for Fuso, but in the confusion reported Yamashiro as Fuso (they were sister ships), which served to completely confuse Nishimura. In the meantime, the torpedo hits on Fuso had proved fatal and she rolled over and sank at about 0325. A huge underwater explosion ignited a large pool of the highly volatile Borneo (Tarakan) fuel in which Fuso’s survivors were swimming. Only about 10 of her crew of 1,600 survived, many lost in the conflagration. Early accounts, including by Morison, indicated that Fuso blew up and for a time the two floating halves drew fire from U.S. ships. However, the research ship Petrel in 2017 confirmed more recent analysis that Fuso went down in one piece and that subsequent U.S. shellfire was directed a flaming pools of oil. Captain Smoot would be awarded his first of two Navy Crosses.

As Smoot’s destroyers launched their torpedoes, the U.S. cruisers opened fire at 0351, followed shortly after by the battleships. Two torpedoes from Bennion hit Mogami (other accounts indicate fire detonated four of Mogami’s own torpedoes), but either way she kept on coming. (By this point in the battle, it is very difficult to reconstruct exactly who shot who). As Smoot’s destroyers were withdrawing, they were mistaken for attacking Japanese. At about 0407, Albert W. Grant was hit 22 times by both Japanese and U.S. cruiser fire (more from the U.S ships) and suffered severe damage, with 39 killed and 104 wounded, but her crew was able to get her engines back on line and she retired from the battle area. The U.S. “machine-gun cruisers,” the light cruisers, pumped out prodigious amounts of 6-inch shellfire (Columbia fired 1,147 rounds in 18 minutes), several of which hit Albert W. Grant.

The U.S. battleships, having crossed the Japanese “T” (although there wasn’t much left of the Japanese “T”) opened fire at 0352. West Virginia hit Yamashiro with her first salvo. In the deluge of shellfire from the cruisers and battleships, some of the battleships could not find targets, particularly those with older radar. West Virginia, California, and Tennessee had new Mark-8 radar and got off 60–90 main battery rounds each. Of the ships with older radar, Pennsylvania never fired her main battery and Maryland used her older radar to fire at the splashes raised by West Virginia’s shells. Mississippi finally fired one salvo, which turned out to be the last U.S. battleship shells ever fired at another enemy ship.

In only a matter of a few minutes, Yamashiro and Mogami were hit repeatedly by battleship and cruiser shellfire, yet both continued returning fire and advancing despite receiving unbelievable punishment. At 0405, Mogami launched a spread of deadly “Long Lance” torpedoes, but because of the greatly reduced visibility in the smoke of the battle, her aim was off, and none of the U.S. battleships were hit. At some point, Yamashiro was hit by more torpedoes from U.S. destroyers, probably Newcomb and possibly Bennion (she probably absorbed at least four torpedoes, possibly five or six total). U.S. shellfire devastated the bridge of Mogami, killing all the senior officers, and at one point the ship was under the command of a chief petty officer signalman, who kept fighting. Finally, after an incredibly gallant but ineffective fight against overwhelming odds, Yamashiro turned away at 0410 and then suddenly rolled over and sank at about 0419—and, like Fuso, only about 10 of her crew of 1,600 would survive. Nishimura was lost with his flagship. Only when the flagship turned away did the battered Mogami follow and finally begin to retreat down Surigao Strait. On the U.S. side, the only casualties were on Albert W. Grant, most from “friendly fire.”

As the battle at the northern end of Surigao Strait reached its crescendo, Vice Admiral Shima’s force of two heavy cruisers (flagship Nachi and Ashigara) and four destroyers was steaming at high speed northerly into the battle area, the flashes of the battle plainly visible ahead. Shima’s force had entered the southern end of Surigao Strait at about 0245 and, due to rain and navigation error, had nearly run aground on an island, the force saved by a last-minute course change. This time, the U.S. PT boats had better luck. PT-137 fired a torpedo at a ship that was probably the severely damaged destroyer Asagumo limping back down the strait. The torpedo missed, but then hit Shima’s light cruiser, Abukuma, under the bridge, killing 30 sailors and severely reducing her speed (yet she continued toward the battle). Abukuma and the rest of Shima’s force were passing unseen on the far side of Asagumo when the torpedo came out of nowhere and hit. The Japanese destroyers had to take evasive action to avoid colliding with Abukuma.

Shima’s force passed burning and sinking Japanese ships, plowing into the battle area at very high speed in severely reduced visibility due to the smoke. The on-rushing Nachi, intent on conducting a torpedo attack on U.S. ships detected on radar, collided with the limping Mogami heading the opposite way at 0420. Last-minute evasive action by Nachi’s skipper kept the collision from being worse, but the damage to Nachi was bad enough to reduce her speed. The chief petty officer on the bridge of Mogami apologized via signal lamp for colliding with the reasonable excuse that all of Mogami’s senior officers were dead. At this point, the Japanese fired a swarm of Long Lance torpedoes in the direction of gun flashes of the U.S. ships, otherwise unseen in the heavy smoke, which luckily hit nothing. Disappointed in the lack of effect of his torpedoes and realizing that Nishimura’s force had been essentially wiped out, and the same was in store for him, Shima opted to live to fight another day, and his force reversed course.

Of Nishimura’s force, Asagumo finally sank, and the severely damaged Mogami would be hit ten more times by shells from U.S. cruisers that briefly pursued her down Surigao Strait. Mogami was then unsuccessfully attacked by U.S. PT boats. At 0902 the next morning, Mogami was hit by three bombs from TBM Avengers from Ommaney Bay (CVE-79) of Taffy 2 and she finally had to be scuttled; 192 of her crew were lost. Only the destroyer Shigure survived (the second time she was the sole survivor of a major battle). Her luck would run out on 24 January 1945, when she was sunk by submarine Blackfin (SS-322).

Of Shima’s force, the badly damaged Abukuma would be hit on 26 October by U.S. Army B-24 bombers (a rare case of high-altitude heavy bombers actually hitting a ship), detonating her torpedo bank, and causing her to sink with the loss of 250 of her crew. Nachi would be sunk by U.S. carrier aircraft off Manila on 5 November 1944, with a loss of 807 crewmen; Vice Admiral Shima was ashore and survived.

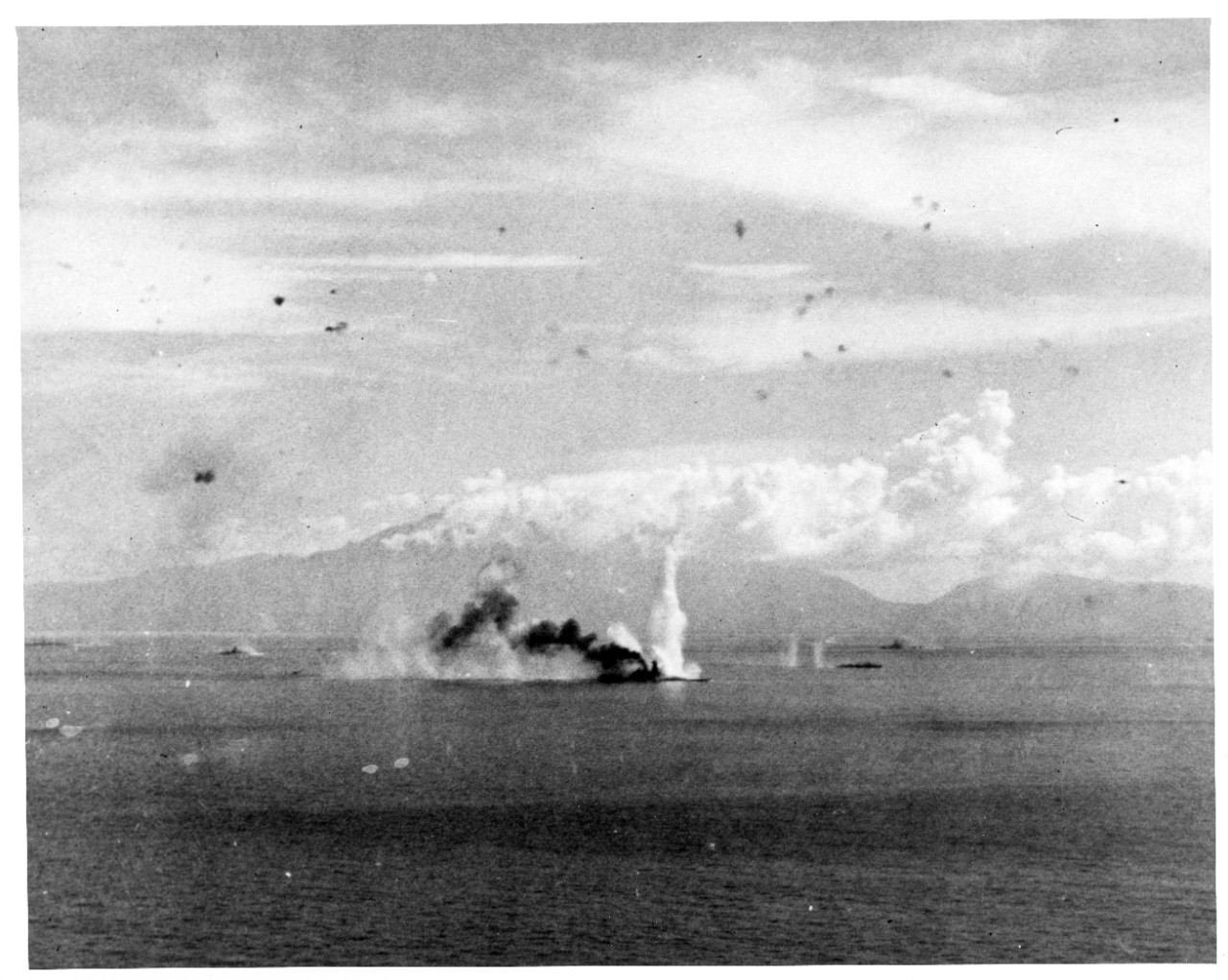

Japanese aircraft carriers Zuikaku (left center) and (probably) Zuiho (right) under attack by U.S. Navy dive bombers during the Battle of Cape Engano. Both ships appear to be making good speed, indicating that this photo was taken relatively early in the action. Both carriers are emitting heavy smoke. Note the heavy concentration of anti-aircraft shell bursts in lower right and right, and a U.S. Navy SB2C Helldiver diving in the lower left (80-G-281767).

The Battle of Cape Engano, 25 October 1944

Early on 24 October, after Kurita’s force (and Nishimura’s “southern” force) had been sighted, but before Ozawa’s carrier force had been detected northeast of Luzon, Halsey and his staff developed a contingency plan to block San Bernardino Strait with a surface force (designated Task Force 34) of 4 battleships, 5 cruisers, and 14 destroyers, intended to be executed on order. However, the actual message promulgating the plan stated that Task Force 34 “will be formed.” The message was not addressed to Kinkaid, but was intercepted and copied anyway by Seventh Fleet, and the ambiguous wording led Kinkaid to the faulty assumption that TF 34 would be formed and would guard San Bernardino Strait. Admiral Nimitz and even the White House Map Room, who were addressed on the message, made the same mistaken assumption as Kinkaid. Halsey did send out a clarifying report at 1710 saying that TF 34 would be formed “when directed,” but sent it by voice radio, which Seventh Fleet did not hear.

During the night of 24–25 October, Halsey’s three carrier groups and accompanying fast battleships raced northwards to engage Ozawa’s carrier force at dawn, leaving behind no forces to guard San Bernardino Strait. This force included five fleet carriers, five light carriers, six new battleships, two heavy cruisers, six light cruisers and 40 destroyers. In the early evening of 24 October, scout aircraft from the light carrier Independence reported that Kurita’s force had reversed course and was once again heading for San Bernardino Strait, and that navigation lights in the strait had been turned on. A Seventh Fleet PBY flying boat, subordinate to Kinkaid, had flown through San Bernardino Strait during the night (just to be on the safe side, even though Kinkaid assumed Halsey had the strait covered), but as the fortunes of war would have it, timed just right to miss the Japanese transit (this was not known to Halsey). Despite the Independence scouts’ report, Halsey viewed the Japanese carriers as the primary threat and continued on course to engage them.

During the night, Vice Admiral Mitscher’s chief of staff, Captain Arleigh Burke (future CNO, 1955–61), became convinced that Ozawa’s force was a decoy and that the Japanese would attack via San Bernardino Strait. Burke tried to convince Mitscher to radio Halsey with a warning. Mitscher declined to do so under the assumption that Halsey had the Independence scouts’ report. (This was true, or at least Halsey’s staff said so in response to queries from Vice Admiral Willis “Ching” Lee and Rear Admiral Gerald Bogan—commander, TG 38.2—who also had become concerned the Japanese carriers were a decoy.) Halsey nevertheless decided to continue toward the Japanese carriers. His intelligence officer, Captain Michael Cheek, with analysis developed by one of his lieutenants, Harris Cox (no relation), also became concerned that the Japanese would come through the unguarded San Bernardino Strait and take the U.S. invasion force by surprise. Cheek wanted to wake Halsey with a warning, but was dissuaded by the Third Fleet chief of staff, Rear Admiral Robert B. “Mick” Carney, (future CNO, 1953–55) on grounds that Halsey was finally sleeping after being awake for 48 hours, and that he had already made up his mind anyway.

At about 0240 on 25 October, Halsey’s battleships detached from the carrier task groups and combined in a single Task Force (TF 34), under the command of Vice Admiral Lee (victor of the battleship versus battleship night action off Guadalcanal on 14–15 November 1942). Halsey was embarked on New Jersey. However, the purpose of this force was to engage Ozawa’s carriers after they were hit by Mitscher’s carrier aircraft, not to cover San Bernardino Strait. One fact missed by most histories of the battle is that even if TF 34 had been formed in response to the Independence scouts’ report, it would have not reached San Bernardino Strait in time to intercept Kurita’s force before it exited the strait into the Philippine Sea.

Early on 25 October, U.S. Navy radio intelligence picked up and reported clear indications that a major Japanese force had exited the San Bernardino Strait and was operating east of Samar, presumably en route Leyte Gulf. Admiral Nimitz was so concerned about this development that he ordered a message transmitted that specifically mentioned that these contacts were due to Ultra intelligence, risking possible compromise of the radio intelligence/code-breaking source. Halsey received this message, but did not react because it was already far too late for TF 34 to intercept Kurita’s force. Halsey also made the assumption that Kinkaid’s six battleships would be able handle the threat, unaware due to communications delays of Kinkaid’s depleted ammunition state after the Battle of Surigao Strait. (Actually, Kinkaid’s battleships still had a significant quantity of ammunition, but of the type intended for shore bombardment. What Kinkaid was critically short of was armor-piercing ammunition—although there is still some dispute about this in varying accounts.)

Despite the indications that Kurita’s force had come through San Bernardino Strait, Halsey reasoned (correctly) that it was already too late for him to do anything about it. Having greatly closed the gap between his forces and Ozawa’s carriers, he chose to continue toward what he perceived as a golden opportunity to finish off the Japanese carrier force for good.

At dawn on 25 October, Ozawa launched 75 aircraft to attack Mitscher’s carriers. At the same time, Mitscher launched 180 aircraft to attack Ozawa’s carriers (with Commander David McCampbell in tactical control of the strike, for which he would be awarded a Navy Cross to go with his Medal of Honor). Almost all the Japanese planes were shot down; U.S. ships were not damaged. Conversely, U.S. fighters escorting the U.S. strike shot down almost all of the 30 Japanese fighters defending their carriers. The first U.S. strike wave was already airborne even as the first searches commenced, and by 0800 commenced the attack on Ozawa’s carriers.

During the course of the day, TF 38 flew 527 sorties against Ozawa’s carriers, sinking the fleet carrier Zuikaku (843 hands lost out of 1,704) and the light carriers Zuiho (215 hands lost) and Chitose (903 hands lost), and the destroyer Akizuki (182 hands lost). The light carrier Chiyoda and light cruiser Tama were severely damaged.

Late in the afternoon, a force of two U.S. heavy cruisers, Wichita and New Orleans (CA-32, with a new bow replacing the one blown off a Tassafaronga in November 1942), two light cruisers, Santa Fe (CL-60) and Mobile (CL-63), and nine destroyers, under the command of Rear Admiral Laurance T. DuBose, raced ahead, caught, and sank the damaged light carrier Chiyoda (lost with all 1,470 hands) and, after a spirited fight, sank the destroyer Hatsuzuki (lost with all hands). After sunset, Ozawa ordered the hybrid battleships Ise and Hyuga to engage DuBose’s force, but they failed to make contact in the darkness. When Zuikaku sank, Ozawa transferred his flag to the light cruiser Oyodo and survived the battle. (Zuikaku turned out to have been a bad choice as a flagship as her communications suite was much inferior to that of Oyodo, which had been groomed as the Combined Fleet flagship before Admiral Toyoda chose to move his staff ashore. Ozawa was plagued by delayed and missed messages throughout the battle, and the Japanese message delays adversely affected U.S. radio intelligence capability to provide timely intercept and reporting). Just before midnight on 25 October, the submarine Jallao (SS-368) sank the crippled light cruiser Tama.

First Kamikaze Attacks, 25 October 1944

At about the same time that Taffy 3 came under attack by Kurita’s battleships in the 0700 hour of 25 October off Samar, the four escort carriers of Taffy 1 (call sign of Task Group 77.4/Task Unit 77.4.1) came under the first true kamikaze attack of the war. (That is, the planes that attacked Taffy 1 launched with the specific purpose of conducting suicide attacks on U.S. ships. There had actually been at least two intended kamikaze strikes over the previous days, but the planes had not found any targets and had returned to base.)

Taffy 1 was commanded by Rear Admiral Thomas Sprague (senior to and no relation to Rear Admiral Clifton “Ziggy” Sprague of CTU 77.4.3—Taffy 3) and included the escort carriers Santee (CVE-29, flagship), Suwanee (CVE-27), Sangamon (CVE-26), and Petrof Bay (CVE-80). Taffy 1’s other two escort carriers, Chenango (CVE-28) and Saginaw Bay (CVE-82), had detached on 24 October en route Morotai to exchange damaged aircraft for replacements (accounting for discrepancies in accounts of how many escort carriers were in the Battle of Leyte Gulf).

Taffy 1 had launched 11 Avenger torpedo bombers and 17 Hellcat fighters (the Sangamon-class escort carriers were bigger than the Casablanca class and carried Hellcats instead of Wildcats), most in a strike intended to pursue Japanese survivors of the Battle of Surigao Strait. By 0730, Taffy 1 was in the act of re-calling aircraft from searches and land strikes in order to re-arm and react to the battle that had commenced off Samar with Taffy 3 about 130 nautical miles to the northwest. In the confused air picture, ten Japanese aircraft slipped in from the south, mimicking U.S. return profiles and making good use of cloud cover; they were detected, but not properly identified.

At 0738, a Japanese Zeke fighter peeled off and dove on the escort carrier Santee with so little warning that there was no anti-aircraft fire in response. The plane crashed into Santee’s flight deck and penetrated into the hangar bay below, killing 16 crewmen. Moments later, a second Zeke dove on Sangamon, while a third acted to draw fire away from the kamikaze, but the kamikaze was hit by fire from Suwanee and just missed the Sangamon.

By 0751, the fires on Santee had been extinguished, when, a few minutes later, lookouts on the destroyer escort Eversole (DE-404) sighted a torpedo from a Japanese submarine just before it struck Santee’s starboard side. Fortunately, Santee was a converted oiler and absorbed the torpedo damage much better than the newer, more lightly built Casablanca-class escort carriers and therefore did not meet the same fate as Liscome Bay (CVE-56) in November 1943. Eversole and Trathen (DD-530) then counter-attacked the submarine.( It is not known which Japanese submarine hit Santee; four were operating in the Leyte Gulf area, and three were lost, one of which, I-26, was the third-most-successful Japanese submarine in terms of tonnage sunk.)

Another Zeke kamikaze came in at 0804, crashed into Suwanee near her aft elevator, and penetrated into the hangar, where its bomb exploded, causing much more damage than on Santee and starting serious fires. Aboard Suwanee, 32 men were killed and another 39 later died of their wounds (259 total were killed, wounded, or missing). Nevertheless, Suwanee’s crew patched the hole in the flight deck and resumed flight operations at 1030. By this time, Taffy 1’s Hellcats had beaten off the rest of the attackers (and some went on to strafe Kurita’s ships). Around noon on 26 October, Suwanee would be hit by another Zeke, causing fires that took nine hours to bring under control and killing another 36 crewmen (107 total in the two kamikaze hits).

Japanese submarine I-56 attacked Taffy 1 at 2234 on 25 October, narrowly missing Petrof Bay. Destroyer escort Coolbaugh (DE-217) counter-attacked. I-56 survived, with an unexploded hedgehog projectile stuck to her deck. On 28 October, Eversole would be hit by two torpedoes from I-45, and sunk with a loss of about 72 of her crew. I-45 fired on some of Eversole’s survivors with machine guns without hitting any before subsequently being sunk by Whitehurst (DE-634).

The Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944

For in-depth coverage, please see H-Gram 036.

Posthumous Medal of Honor Citation for Commander Ernest Evans

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as commanding officer of USS Johnston in action against major units of the Japanese fleet during the battle off Samar on 25 October 1944. The first to lay a smokescreen and to open fire as an enemy task force, vastly superior in number, firepower and armor, rapidly approached, CDR Evans gallantly diverted the blasts of hostile guns from the lightly armed and armored carriers under his protection, launching the first torpedo attack when the Johnston came under straddling Japanese shellfire. Undaunted by damage sustained under the terrific volume of fire, he unhesitatingly joined others of his group to provide fire support during subsequent torpedo attacks against the Japanese, and outshooting and outmaneuvering the enemy, he consistently interposed his vessel between the hostile fleet units and our carriers despite a crippling loss of engine power and communications with steering aft, shifted command to the fantail, shouting steering orders through and open hatch to men turning the rudder by hand and battled furiously until the Johnston, burning and shuddering from a mortal blow, lay dead in the water after 3 hours of fierce combat. Seriously wounded early in the engagement, CDR Evans, by his indomitable courage and brilliant professional skill, aided materially in turning back the enemy during a critical phase of the action. His valiant fighting spirit throughout the historic battle will venture as an inspiration to all who served with him.”

The destroyer escort USS Evans (DE-1023), commissioned in 1957 and decommissioned in 1973, was the only ship named after Commander Ernest Evans. The ship’s motto was “Uletsu-Ya Sti,” meaning “Bold Warrior” in Cherokee.

The contributions of the aircraft from the six escort carriers of Taffy 2 (Task Unit 77.4.2, commanded by Rear Admiral Felix B. Stump) are often overlooked in accounts of the battle. With more time to re-arm with torpedoes than Taffy 3, Taffy 2’s aircraft inflicted much of the severe damage on Kurita’s force and was a significant part of the reason why he turned away. Planes from Natoma Bay (CVE-62), Manila Bay (CVE-61), Marcus Island (CVE-77), Kadashan Bay (CVE-76), Savo Island (CVE-78), and Ommaney Bay (CVE-79) conducted multiple attacks on Kurita’s force and deserve a significant share of the credit for leaving heavy cruisers Chokai, Chikuma, and Suzuya in sinking condition, and damaging heavy cruisers Tone and Haguro. (Most of Chokai’s crew were rescued by destroyer Fujinami, which was then sunk on 27 October by planes from Essex with the loss of all hands, including all Chokai survivors. The same fate befell the survivors of Chikuma, when the destroyer Nowaki was sunk by U.S. cruiser gunfire and torpedoes from destroyer Owen—DD-536—late on 25 October).

Halsey’s Response to Taffy 3’s Plight

As the attacks by Kurita’s force on Taffy 3 commenced, Vice Admiral Kinkaid quickly recognized the gravity of the situation and, by 0800, was sending messages to Halsey requesting assistance from TF 34 to stop Kurita’s force before it could get into Leyte Gulf. However, due to the stove-piped theater communications architecture, Halsey didn’t get these messages until around 1000 (by which time Kurita had already turned around). Kinkaid even sent one message in plain text: “My situation critical. Fast battleships and support by airstrikes may be able to keep enemy from destroying CVEs and entering Leyte.” (Japanese radio intelligence intercepted and copied this message, so Kurita had it sooner than Halsey). Kinkaid also sent a message indicating his battleships were critically low on ammunition following the Battle of Surigao Strait. Actually, this message appears to have been exaggerated, although there are differing accounts regarding the true state of the battleships’ ammunition.

The increasingly desperate messages from Kinkaid and Taffy 3 reached Admiral Nimitz at Pearl Harbor, provoking great concern and prompting Nimitz to send one of the most famous and dissected messages of the war: “TURKEY TROTS TO WATER GG FROM CINCPAC ACTION COM THIRD FLEET INFO COMINCH CTF SEVENTY-SEVEN X WHERE IS RPT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR RR THE WORLD WONDERS.” The phrases before and after the double consonants were padding, designed to complicate Japanese cryptanalysis. However, the phrase “the world wonders,” violated standing operating procedure in that padding was to be nonsensical. The radio room on Halsey’s flagship New Jersey should have stripped off “the world wonders” before passing the message to Halsey, but was unsure whether it was actually part of the message. (“The world wonders” may have been derived from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “Charge of the Light Brigade,” as 25 October 1944 was the 90th anniversary of the famous charge). Regardless, Halsey thought he was being insulted by Nimitz and flew into a blinding rage, throwing his cover on the deck and stomping on it, until finally Halsey’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral “Mick” Carney, got Halsey to calm down.

Halsey well understood that it was already too late for his battleships to effect the outcome of the Battle off Samar, and only with the greatest of reluctance ordered them to cease pursuit of the Japanese carriers and turn toward Leyte Gulf at about 1100. As Halsey expected, the subset of TF 34, designated TG 34.5 under Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger II and consisting of the two fastest battleships (Iowa and New Jersey), three cruisers, and eight destroyers did not reach San Bernardino Strait before Kurita had already entered it westbound. The U.S. ships were ordered not to pursue through the strait for fear it had been mined. They did catch the destroyer Nowaki, which had stayed behind to rescue survivors of the heavy cruiser Chikuma; Nowaki was sunk with her entire crew and the survivors of Chikuma, a total of about 1,400 men.