H-063-4: The Formosa Expedition, 1867

On 12 March 1867, the U.S.-flag merchant bark Rover wrecked in a remote area at the southern tip of Formosa (now Taiwan). Aboriginal Paiwan warriors killed all the survivors (some accounts say 14, others 24), including Rover’s captain, Joseph Hunt, and his wife, Mercy G. Beerman Hunt. One Chinese sailor was spared. The action by the Paiwan warriors was in retaliation for the killing of tribal members by other Europeans. Even so, the Paiwan had a long-standing reputation of hostility to outsiders.

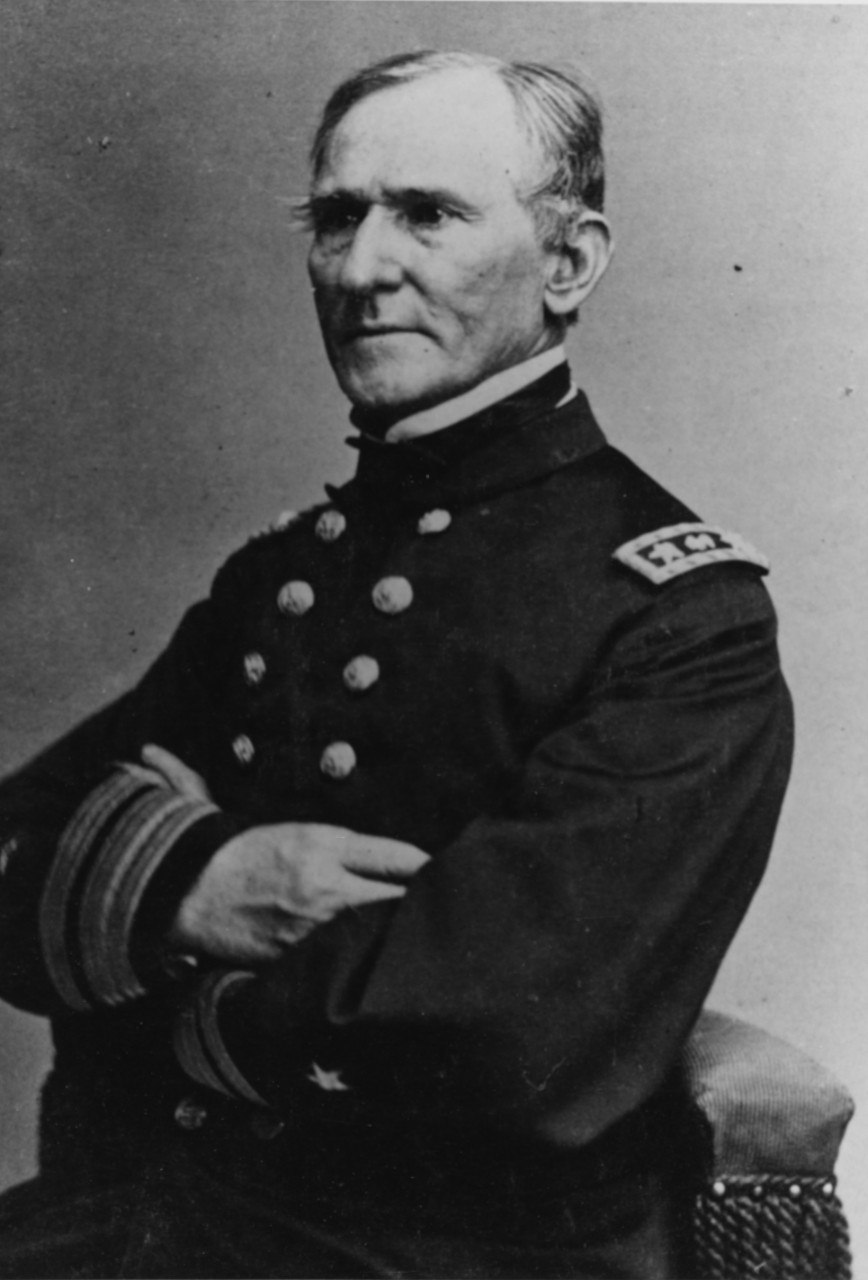

The first ship on the scene was British screw sloop Cormorant, commanded by Commander George E. Broad, Royal Navy. Despite an offer to ransom any captive survivors, a British landing party was fired on. After recalling the party, Cormorant shelled the jungle, which hid the unseen assailants. Cormorant then proceeded to Amoy, China, where the commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, Rear Admiral Henry H. Bell, arrived aboard his flagship, screw sloop Hartford, while transiting to Yokohama, Japan.

Bell had previously been in command of screw frigate San Jacinto during the Battle of the Pearl River Forts in 1856 (see H063.1). Upon being informed of the fate of Rover by Commander Broad, Rear Admiral Bell dispatched the new iron-hulled “double-ender” gunboat Ashuelot to investigate and make contact with local Chinese authorities on Formosa. The steam-powered Ashuelot was armed with two 8-inch Dahlgren guns and was commanded by Commander John C. Febiger. Febiger was a survivor of the wreck of sloop-of-war Concord in the Mozambique Channel in 1842; the captain and two others were lost. (Concord had the distinction of being the first U.S. warship christened by a woman, in 1830.)

When Commander Febiger reached Formosa, he was able to confirm the account. Local representatives of the Chinese Qing Dynasty government in Formosa assured Febiger that the Paiwan tribesmen were operating outside the control of any lawful government, in effect indicating they would not interfere with however the United States chose to deal with the situation. The American consul in Xiamen, China, located across the strait from Formosa, arrived in Formosa and spent the month of April 1867 trying to make contact with the Paiwan, but the tribes remained implacably hostile and attempts at some sort of diplomatic solution failed.

After a delay of three months, which was blamed on red-tapeism in Washington, Rear Admiral Bell departed Shanghai in June 1867 on his flagship, screw sloop Hartford, in company with screw sloop Wyoming, bound for Formosa to conduct a punitive expedition. (Monthly U.S. steamer service had just been instituted between San Francisco and the Far East, enabling indecision in Washington to affect overseas operations—this might arguably be described as the beginning of the “8,000-mile screwdriver.”)

Hartford, commissioned in 1859, had served with great distinction in the Civil War as flagship for Admiral David G. Farragut at the battles of New Orleans, Vicksburg, and Mobile Bay, as well as in numerous smaller actions. Her main armament consisted of twenty 9-inch smoothbore Dahlgren guns. Wyoming, also commissioned in 1859, had searched for the missing Levant in 1860. She spent much of the Civil War in the Far East in the fruitless search for the Confederate commerce raider CSS Alabama and had engaged Japanese warlords in 1863 (see H-063-3).

Bell’s two ships arrived off southwestern Formosa on 13 June 1867 and anchored a half mile offshore, where Rover had wrecked. Paiwan warriors “painted red” were observed gathering in cleared spots, indicating they would not be surprised. Ship’s boats landed 181 officers, sailors, and Marines under the overall command of Commander George E. Belknap (captain of Hartford). The group included Marine contingents from both ships, 80 armed sailors from Hartford, 40 armed sailors from Wyoming, and the Hartford’s light howitzer crew of five. The intent of the operation was somewhat vague—punish the Paiwan—and intelligence on the terrain and objective was completely lacking.

Commander Belknap’s group split into two columns for the march inland. The second column was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Alexander Slidell MacKenzie. (MacKenzie’s father was in command of the brig Somers in 1842 during the only attempted mutiny in U.S. Navy history to result in deaths; the elder MacKenzie ordered three crewmen hanged who were accused of plotting mutiny, one of whom was Midshipman Philip Spencer, the 19-year-old son of Secretary of War John C. Spencer. MacKenzie’s decision to hang the accused mutineers—before they had attempted to mutiny—was highly controversial at the time, and still is. MacKenzie’s brother was one of the Confederate commissioners intercepted and removed from the British Royal Mail vessel RMS Trent by Captain Charles Wilkes on San Jacinto in 1861 in what was known as the Trent Affair. See H-Gram 062 and H-063-1.)

As the two columns pressed inland, about 20 Marines under the command of Marine Captain James Forney formed a skirmish line ahead. The jungle environment was extremely hot and humid, and the U.S. force was inappropriately dressed in heavy woolen uniforms for shipboard warmth. After an hour of thrashing through the dense jungle, Paiwan warriors opened fire with muskets from a concealed hill ahead. No one was hit. MacKenzie’s column and the Marines charged the position, but by the time they hacked their way there, the Paiwan had melted away into the jungle.

The two columns pressed forward, coming under fire from spears, rocks, and musket fire from a mostly unseen enemy. Each time the U.S. force charged, the Paiwan just retreated further into the jungle. After about six hours of this, a number of U.S. personnel had passed out from heat exhaustion and sunstroke, and others were delirious. Finally, unseen Paiwan warriors fired a volley of muskets. MacKenzie was hit and mortally wounded. At this point, Belknap, who was prostrated by the oppressive heat, made the decision to withdraw from the fruitless pursuit. Paiwan casualties, if any, are unknown.

After the failed punitive expedition, Rear Admiral Bell recommended that the only way to ensure the area was safe was to enlist a powerful local ally to drive out the Paiwan natives. The American consul in Xiamen convinced the Chinese governor general of Fuzhou Province to send a 1,000-man expedition to Formosa. Although Bell declined to send a gunboat in support of this expedition, the American consul, Charles W. Le Gendre, actually wound up in charge of it; he succeeded in negotiating a treaty with the natives for the safety of shipwrecked sailors in exchange for keeping Chinese soldiers out of Paiwan territory. Le Gendre later reported that the Paiwan chief’s willingness to negotiate was a result of the power demonstrated by the U.S. expedition in June, which perhaps wasn’t such a failure after all.

Despite the agreement, Formosan natives continued on occasion to kill shipwreck survivors. The most egregious was the Mudan Incident in 1871, when 54 Ryukyuan sailors were beheaded by Paiwan natives. This incident provoked a Japanese military campaign in 1874—the first overseas campaign by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. The Japanese campaign succeeded where the American expedition failed, but at a cost of 12 Japanese killed in battle, and 561 dead from disease.

In late 1867, the U.S. East Indies Squadron was reconfigured as the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, with Rear Admiral Bell still in command. On 1 January 1868, Bell arrived in Osaka, Japan, aboard Hartford, in company with screw sloops Shenandoah and Oneida and screw gunboat Aroostook. The purpose of the port call was to pressure the Japanese into opening the port of Hyogo (near Kobe) to Western trade, as they had previously committed to do in the accord after the second Battle of Shimonoseki Strait. Despite rough weather on 11 January, Bell chose to go ashore for a meeting. The boat capsized when it was hit by “three heavy rollers”; Bell, his flag lieutenant, and 10 sailors perished (only three were rescued). Bell had been promoted to Rear Admiral (technically on the retired list) the previous year, which may make him the first U.S. Navy admiral to die in the line of duty. (Of note, Oneida was accidentally hit by the British steamer Bombay off Yokohama, Japan, on 24 January 1870 and sank with the loss of 125 crewmen; 61 were rescued by Japanese fishing boats.)

George Belknap was promoted to rear admiral in 1889; his son Reginald Belknap commanded the North Sea mine barrage in World War I and was promoted to rear admiral in 1927. Clemson-class destroyer DD-251 (1919–45) was named in honor of the elder Belknap. The guided missile cruiser CG-26 (1964–95) was named in honor of both Belknaps.

The iron-hulled gunboat Ashuelot struck a rock off the Chinese coast on 17 February 1883 and sank with the loss of 11 crewmen. Wyoming continued to serve in the East Indies, North Atlantic, and Europe until 1878; she then served as a training ship for midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy until she was sold off in 1892. Hartford survived in various capacities, due to her Civil War fame, until her final decommissioning in 1926. In 1938, she was moved to Washington, DC, to be part of a naval museum (in the Tidal Basin) envisioned by President Franklin Roosevelt, which was to also include Constitution, Constellation, and Olympia. The plan was abandoned as soon as Roosevelt died in 1945. After being poorly maintained, Hartford sank at her berth in the Norfolk Navy Yard on 20 November 1956.

Sources include: Far China Station: The U.S. Navy in Asian Waters 1800–1898, by Robert Erwin Johnson: Naval Institute Press, 2013;“The Pirates of Formosa; Official Reports of the Engagement of the United States Naval Forces with the Savages of the Isle” in the New York Times, 23 August 1867; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS).