H-060-2: Lost With All Hands

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

It is often said that from the moment a ship is launched the sea is trying to sink it. Sometimes the sea succeeds. In an 1850 report to Congress, the U.S. Navy reported that 29 ships had been lost up to that date. Of those, seven were “never heard of” after sailing, which also meant none of their crews survived. In 1934, the Navy Department Library (now part of NHHC) reported in the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings that 19 U.S. Navy ships had “vanished” up to that point. Counting gunboats and submarines, by my count, at least 27 U.S. Navy vessels have been lost with all hands due to weather and accidents since 1781. A few of these ships have subsequently been located, or were located at the time of their loss, and are not technically “vanished.” Numerous other ships have been lost with large loss of life or with only a handful of survivors. The bottom line is that the sea is always a very dangerous place, even in the absence of enemy fire. (Some of the 52 submarines lost during World War II may have been lost with all hands due to accident, although officially the cause of loss is unknown for 15 of them.)

The following U.S. Navy ships were lost with all hands (not including ships lost in combat):

1781. Saratoga—Continental Navy sloop, commanded by Captain John Young

On 18 March 1781, Saratoga was escorting a convoy of French and American merchant ships from Haiti when she detached from the convoy to pursue and capture a British vessel, which surrendered without a fight. After the prize crew was aboard, a wind of “fearful velocity” nearly capsized the prize. When the prize crew then attempted to join with Saratoga, no trace of the sloop could be found and 86 of Saratoga’s crew perished (minus the unknown number in the prize crew).

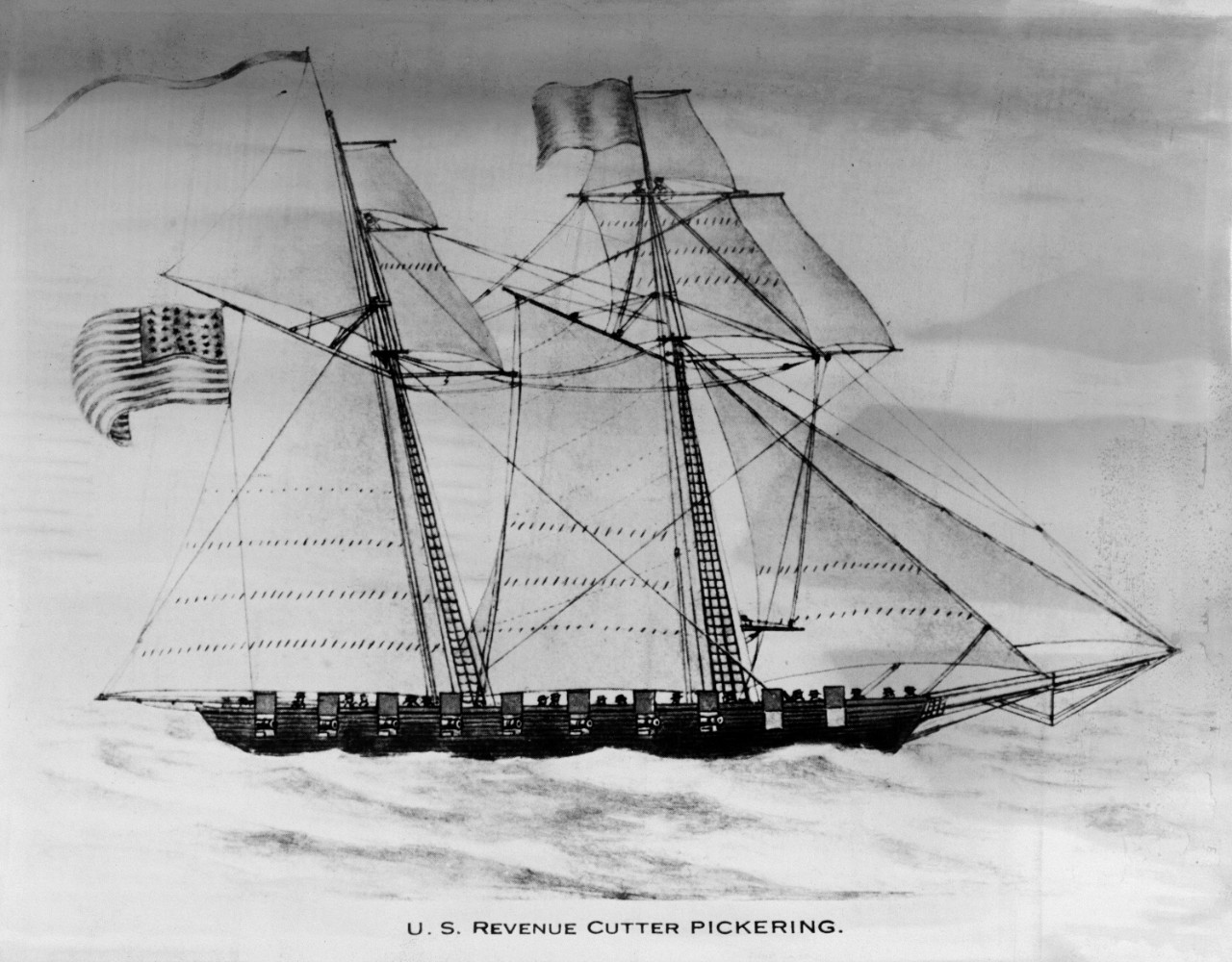

1800. Pickering—topsail schooner, commanded by Master Commandant Benjamin Hiller

Pickering notably defeated a more heavily armed French privateer (L’Egypte Conquise) after a nine-hour battle on 18 October 1799 during the Quasi-War with France, in addition to recapturing 13 American ships and four more French ships. Pickering departed New Castle, Delaware, on 20 August 1800 to join Commodore Thomas Truxtun’s squadron on the Guadaloupe Station in the West Indies. Pickering and her crew of 105 were never heard from again. The ship was presumably lost in a hurricane that struck the West Indies in late September, but she left no trace. Pickering originally served in the Revenue Cutter Service (a forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard), but served as a U.S. Navy ship during the Quasi-War.

1800. Insurgent—frigate, commanded by Captain Patrick Fletcher

Originally the 40-gun French frigate L’Insurgente was considered one the of the fastest frigates in the world. She was engaged by Constellation (under the command of Captain Thomas Truxtun) and captured on 9 February 1799, losing 70 of her crew of 409, while Constellation lost only three men. First Lieutenant John Rogers and Midshipman David Porter led the prize crew. (Rogers would later fire the first shot of the War of 1812 from his flagship, the frigate President. Porter gained fame as captain of the frigate Essex during the War of 1812, and was adoptive father to future Admiral David Glasgow “damn the torpedoes” Farragut.) This was the first U.S. victory against a foreign naval vessel since the end of the American Revolution in 1783. After incorporation into the U.S. Navy as Insurgent, she departed Hampton Roads on 8 August 1800 en route to the West Indies and vanished without a trace with her approximately 340-man crew.

Insurgent was assessed to have been lost in a severe hurricane that struck the West Indies on 20 September 1800, which may have also sunk Pickering and almost sank the cutter Scammel (which survived by jettisoning guns and anchors). Insurgent suffered the largest loss of life on a single ship due to the elements in U.S. Navy history. Combined with Pickering, the loss of about 455 men was the worst loss of life from natural causes until 18 December 1944, when Typhoon Cobra sank three destroyers—Hull (DD-350), Monaghan (DD-354), and Spence (DD-512)—and killed approximately 790 men. The loss of Insurgent and Pickering resulted in the worst loss of life in the U.S. Navy from any cause until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

1805. Gunboat No. 7—commanded by Lieutenant Peter S. Ogilvie

Jeffersonian gunboats were not one of President Thomas Jefferson’s better ideas. Appalled by the $302,000 cost of a frigate like Constitution, Jefferson viewed gunboats as a cheaper way to defend the country at $5,000 each (although cost overruns ran the average price to $10,000—some things never change). The problem was that a frigate had 40 times the firepower of a gunboat, which with their low freeboard were already close to sinking. The result was predictable in the War of 1812 with the British defeat of American gunboats on the Chesapeake Bay and the subsequent burning of Washington, D.C.

Although the small gunboats (two 32-pound long cannons) were designed for coastal defense, ten of them were ordered to sail across the Atlantic in 1805 to assist Commodore John Rogers’ fight with Barbary pirates. Gunboat No. 7 departed New York on 14 May, sprang her mast on 20 May, and returned to New York, whereupon all but three of her crew deserted. After the challenging recruitment of another crew, Gunboat No. 7 sailed from New York on 20 June with a crew of about 20 and was never seen again. The other gunboats made the crossing with great difficulty and some were almost lost. Many years later, Secretary of the Navy John Lehman would say, “There is a place for little boats—in the Libyan Navy.”

1810. Gunboat No. 159

On 11 September, Gunboat No. 159 was lost in the Chesapeake Bay with all 13 hands.

1811. Gunboat No. 2

On 5 October, Gunboat No. 2 was lost in a gale on the Chesapeake Bay with all 40 hands. (Some accounts say the gunboat was lost off St. Mary’s, Georgia, but the location is possibly St. Mary’s, Maryland. Gunboats did operate out of St. Mary’s, Georgia, so the Chesapeake Bay might be incorrect.)

1814. Wasp—22-gun sloop-of-war, commanded by Master Commandant Johnston Blakeley

One of the most successful U.S. Navy ships during the War of 1812, Wasp captured seven ships and burned most of them during her first voyage. Wasp also defeated the 18-gun brig-sloop HMS Reindeer in a brutal alongside battle in which British boarding teams were repeatedly repulsed before an American boarding team took Reindeer. The captain of Reindeer and 24 of his men were killed and 42 wounded. Wasp set fire to Reindeer, which blew up.

On her second raiding voyage, Wasp snatched the brig Mary out of a ten-ship convoy under the protection of 74-gun ship-of-the-line HMS Armada. Wasp burned Mary and went for another ship before Armada finally drove her off. Wasp captured and burned more ships before engaging and defeating 18-gun brig HMS Avon in another deadly sea battle. Although Wasp was driven off by the arrival of additional British warships, Avon subsequently sank as a result of her damage. On 21 September, Wasp captured the armed merchant brig Atalanta (8-guns) and put a prize crew aboard under the command of Midshipman David Geisinger.

Wasp encountered the Swedish brig Adonis on 9 October 1814 and was never seen again. Wasp had a crew of about 173 (minus the prize crew on Atalanta). Rumors about Wasp’s fate swirled for years. One story originating in 1824 was that the crew of Wasp ended up shipwrecked ashore in North Africa, during which Arabs claimed “hundreds” of sailors thought to be British, who were all killed in battle with local Arabs. Theodore Roosevelt recounted this story in his The Naval War of 1812, but it has never been verified and Roosevelt concluded, “How she perished no one ever knew.”

1815. Epervier—18-gun brig, commanded by Lieutenant John T. Shubrick

The 18-gun brig HMS Epervier was captured by the 22-gun sloop-of-war Peacock on 14 April 1814. Despite extensive damage, the ship was repaired and commissioned in the U.S. Navy as Epervier. During the Second Barbary War, Epervier joined Commodore Stephen Decatur’s squadron in the Mediterranean and participated in the capture of the Algerian frigate Meshuda and brig-of-war Estedio. Following the surrender of the Dey of Algiers, Decatur ordered Epervier to return to the United States with a copy of the treaty and captured battle flags. Epervier transited the Straits of Gibraltar on 14 July 1815. Neither the ship nor her crew of three officers, 132 Sailors, and two Marines were ever seen again. She was possibly lost in an Atlantic hurricane around 9 August 1815.

1820. Lynx—6-gun Baltimore Clipper rigged schooner, commanded by Lieutenant John Ripley Madison

Following operations in the Gulf of Mexico, during which she captured two pirate schooners and three boats filled with pirates and booty, Lynx departed St. Mary’s, Georgia, on 11 January bound for Kingston, Jamaica, to resume antipiracy operations. Lynx and her crew of 50 disappeared without a trace.

1824. Wildcat—schooner, under the temporary command of Midshipman L. M. Booth (normal commander was Lieutenant James E. Legare)

Serving with the West Indies Squadron suppressing piracy, Wildcat carried urgent dispatches from the West Indies to Washington, D.C. On 28 October, Wildcat was lost in a gale while transiting between Cuba and Thompson’s Island (now Key West and then the base of operations for the West Indies Squadron). All 31 aboard were lost.

1829. Hornet—20-gun sloop-of-war, commanded by Captain Hensley

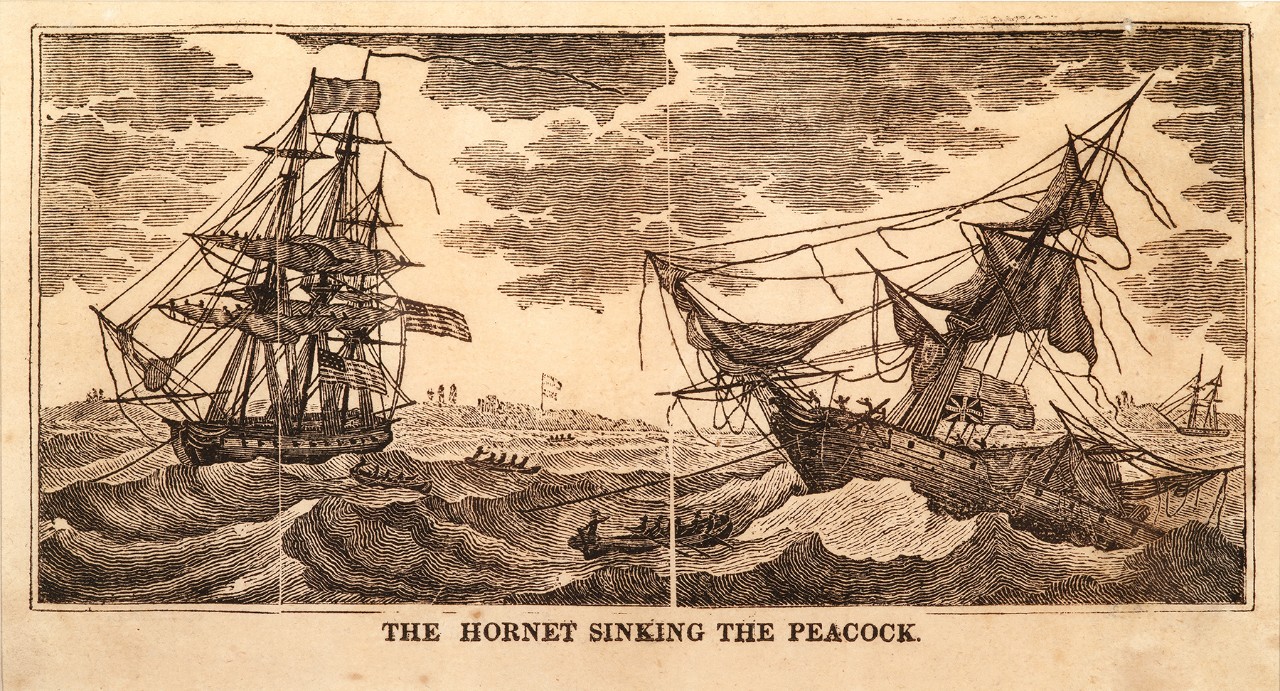

During the War of 1812, Hornet was the first U.S. Navy ship to capture a British privateer, and on 24 February 1813, she engaged and sank the British sloop-of-war HMS Peacock. On 23 March 1815, Hornet captured British sloop-of-war HMS Penguin near Tristan du Cunha in the far South Atlantic. (Technically the war was over, but many ships hadn’t received the word.) On 27 April 1815, Hornet engaged what she thought was a large merchant ship but which was actually the 74-gun British ship-of-the-line HMS Cornwallis. Hornet escaped by essentially throwing everything over the side. After the war, Hornet operated mostly in the West Indies, suppressing piracy and the slave trade. Hornet departed Pensacola on 4 March 1829 en route to the Mexican coast and was never seen again. A report of unknown accuracy indicated she was dismasted in a gale off Tampico, Mexico, and foundered. Her entire complement of 145 men was lost.

1831. Sylph—schooner, commanded by Lieutenant H. E. V. Robinson

Commissioned in May 1831, Sylph’s mission was to protect stands of live oak, extensively used in shipbuilding but increasingly rare. Sylph and her crew of 13 departed Pensacola in August and were never heard from again. She was possibly a vessel sighted in distress in a severe storm near the mouth of the Mississippi River.

1839. Sea Gull—schooner, commanded by Passed Midshipman James W. E. Reid

Acquired by the U.S. Navy in 1838, Sea Gull was one of six ships in the U.S. Exploring Expedition (U.S. Ex. Ex.), commanded by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, to survey parts of Antarctica and the Pacific Islands (and which discovered that Antarctica is actually a continent). On 17 April, Wilkes departed Antarctica for Valparaiso, Chile, leaving Sea Gull and schooner Flying Fish behind to await arrival of supply ship Relief and then to proceed to Valparaiso. On 19 May, Flying Fish arrived at Valparaiso but Sea Gull never did. She was last seen waiting out a gale near Cape Horn; 15 men were lost. (Of note, an additional two officers and 24 Sailors and Marines died during the expedition, a number in armed conflict with Pacific Islanders in the Gilberts, Fiji, and near Samoa.)

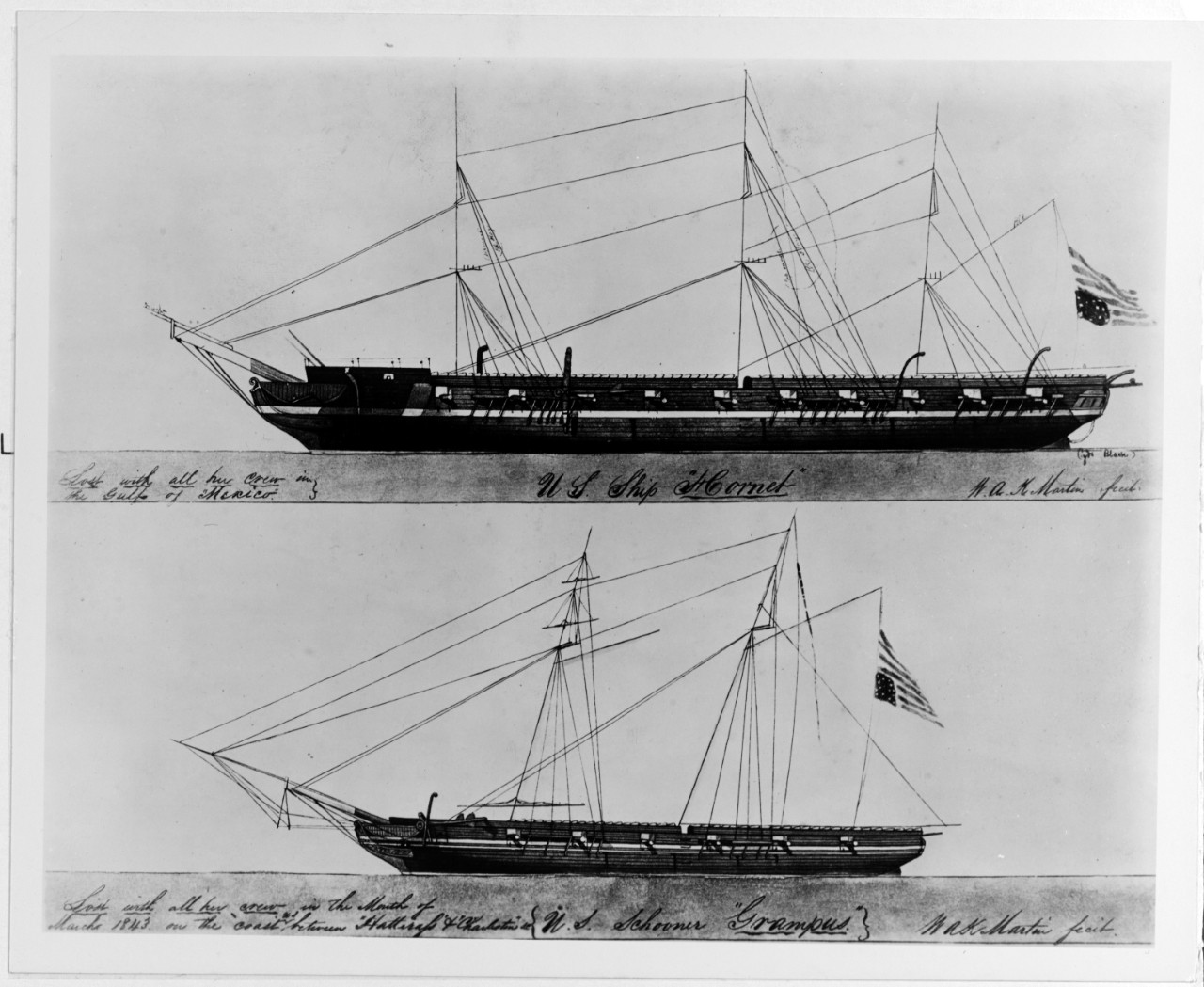

1843. Grampus—schooner

Built at the Washington Navy Yard in 1821 during the first U.S. construction program after the War of 1812, Grampus served on antipiracy and slave-trade suppression duties in the West Indies and West Africa. She had a small role in the Amistad affair in February 1841 (one of the most legally complex and consequential legal cases regarding the international slave trade). Operating with the Home Squadron out of Norfolk, she was last seen off St. Augustine, Florida, on 15 March 1843, and was subsequently lost with at least 25 men aboard.

1854. Porpoise—brig

Porpoise was commissioned in 1836 and participated in the Wilkes Expedition to Antarctica and the South Pacific. She also took part in antislavery patrols off West Africa and service off Tampico and Vera Cruz, Mexico, during the war with Mexico in 1845–46. She participated in the North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition in 1853 as flagship for Commander Cadwalader Ringgold. During the summer of 1854, Ringgold was relieved of command for being “insane” by Commodore Matthew Perry, who was on his own expedition to the Far East to open Japan to U.S. trade. Porpoise detached from the rest of the group on 21 September 1854 between Formosa and China and was lost without a trace of her 62-man crew. She was possibly lost in a typhoon in the area a few days later.

1854. Albany—22-gun sloop-of-war, commanded by Commander James Thompson Gerry

Commissioned on 6 November 1846, Albany was one of the last sail-powered sloops constructed. She saw extensive service in the Mexican-American War during 1846–1848. Her last patrol was along the coast of New Granada (now Columbia and Venezuela). Albany departed Aspinwall (now Colon, Panama) on 29 September 1854 en route to New York and was never seen again. Among the 193 men lost were Commander James T. Gerry, youngest son of former Vice President of the U.S. Elbridge Gerry, and Lieutenant John Quincy Adams, grandson of President John Adams and nephew of President John Quincy Adams.

1860. Levant—22-gun second-class sloop-of-war, commanded by Commander William E. Hunt

Action at the Canton Barrier Forts, China, 21 November 1856. Painting of the bombardment by USS Levant and USS Portsmouth, in support of U.S. forces landing to assault the forts. Oil painting was donated by William Macomb, Philadelphia, from the collection of his father, Captain William Macomb, Executive Officer of Portsmouth at the time of this action. (NH 42915)

Levant was commissioned in March 1838 and provided part of the landing force that claimed California from Mexico in July 1846. She then deployed to the Mediterranean followed by the Far East. Under the command of future Civil War hero Commander Andrew H. Foote, she participated in the Battle of the Pearl River Forts, destroying four Chinese forts by putting a landing party ashore and turning one fort’s cannons against the others. During the battle, Levant was hit in the hull and rigging 22 times by Chinese cannon fire, suffering one dead and six wounded. On a later deployment, Levant hosted a state visit in Honolulu by Hawaiian King Kamehameha IV. She departed Hilo, Hawaii, on 18 September 1860 and neither the ship nor her crew of 155 were seen again. Four U.S. Naval Academy graduates were among those lost. A mast and part of a lower yardarm washed ashore near Hilo, with some indication of an attempt to make them into a raft. A severe hurricane reported in the area may have been the cause. In July 1861 a bottle washed ashore on Cape Sable Island, Nova Scotia; the mostly unreadable message was reportedly from the last three survivors in a boat from Levant and contained the words “God forgive us.”

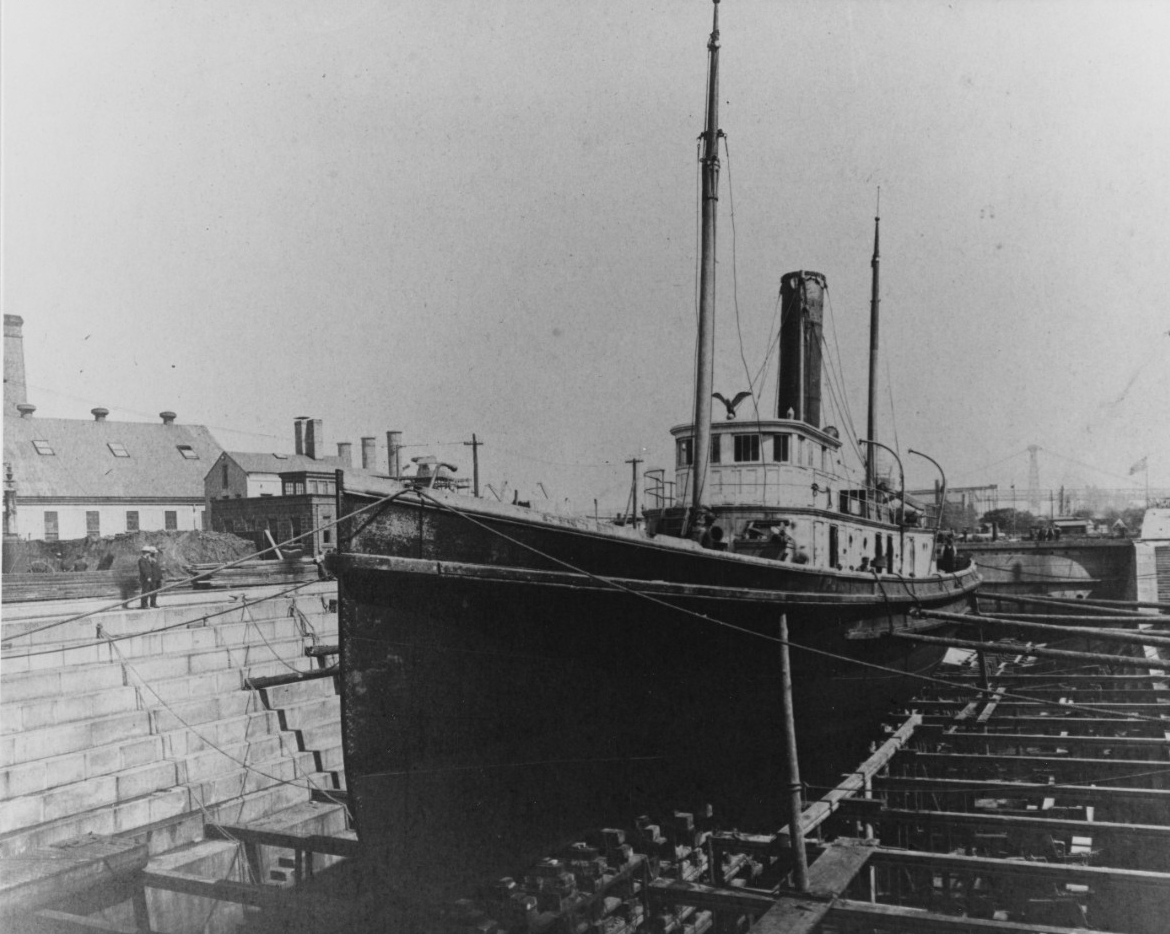

1910. Nina—fourth-rate iron-hulled steamer

Commissioned on 6 January 1866, Nina served in a variety of capacities as a tug, torpedo boat, salvage vessel, tugboat again, torpedo boat tender, supply ship, and then as a submarine tender for the fledgling U.S. submarine force. On 6 February 1910, Nina departed Norfolk en route to Boston and was last sighted off the Chesapeake Capes in a gale. The 33 men aboard were declared lost. The wreck of Nina was located by divers in 1978, 11 nautical miles northeast of Ocean City, Maryland.

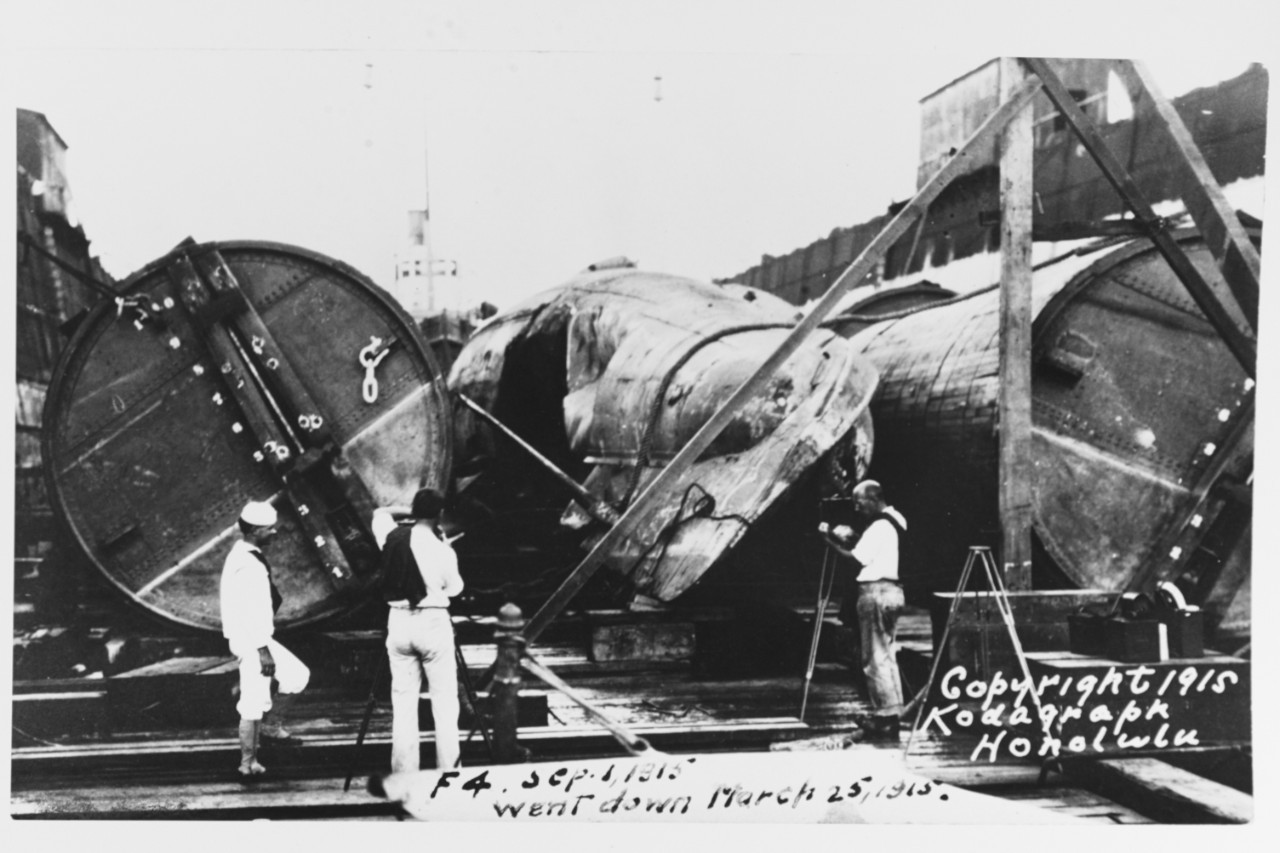

1915. F-4 (SS-23)—F-class submarine, commanded by Lieutenant (junior grade) Alfred Louis Ede

Commissioned on 3 May 1913, F-4 transferred to the Pacific as part of the First Submarine Group, Pacific Submarine Flotilla. While conducting exercises off Honolulu, Hawaii, on 25 March 1915, F-4 submerged in 306 feet of water but did not resurface. Extensive efforts to locate the submarine in time to save the crew of 21 were unsuccessful. F-4 was subsequently raised on 29 August 1915. One of the divers involved in the salvage was John Henry Turpin, among the first African Americans to qualify as a Navy Master Diver. (Turpin survived two catastrophic explosions; he was a mess attendant on Maine when she blew up in Havana harbor in 1898 and one of 90 survivors of 350 aboard. He was assigned to the gunboat Bennington (PG-4) when, on 21 July 1905 in San Diego, a boiler explosion on the ship killed 66 of 102 aboard.) The investigating board concluded that corrosion of lead lining in the battery tank was what caused F-4’s loss, but as is the norm in submarine sinkings, others have second-guessed the board, blaming an unreliable magnetic reducer or problems in air supply lines to the ballast tanks. In November 1915, F-4 settled to the bottom of Magazine Loch, until in 1940 she was reburied in a trench below Submarine Base Mooring S14 in Pearl Harbor. (For more on U.S. submarine losses due to accident please see H-Gram 019/H-019-3.)

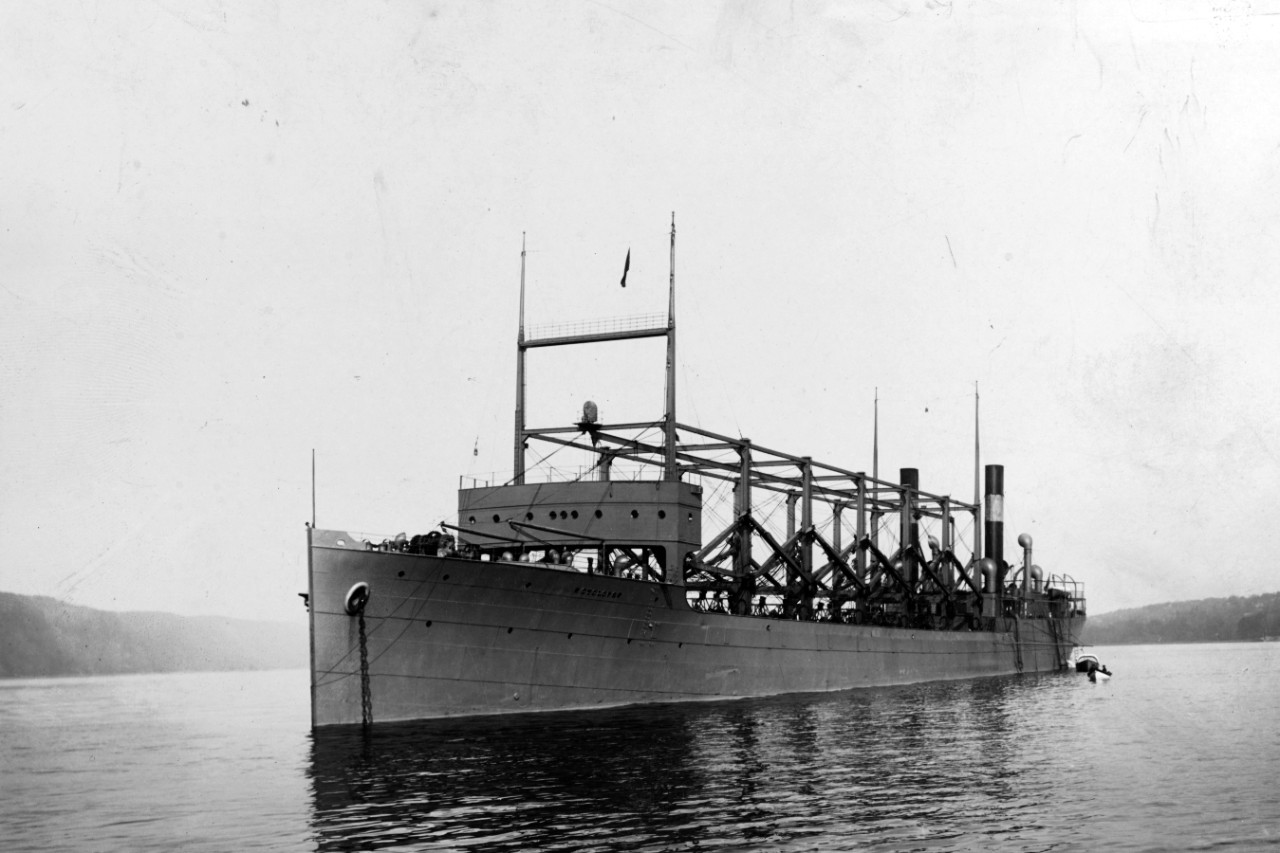

1918. Cyclops (AC-4)—Proteus-class collier, commanded by Lieutenant Commander George W. Worley

On 22 February 1918, Cyclops departed Salvador, Brazil, bound for Baltimore with a cargo of manganese ore picked up in Rio de Janeiro. Following a brief stop at Barbados on 4 March 1918 with 306 on board (250 crew and 56 passengers—these numbers vary in different sources), Cyclops was never seen again and no trace has ever been found. Although her disappearance occurred during time of war, there is no evidence enemy action had anything to do with her loss. The loss of Cyclops was later incorporated into the mythology of the Bermuda Triangle. Of note Cyclops had three sisters. Proteus (AC-9) was later sold into commercial service and vanished without a trace in the Bermuda Triangle with a cargo of ore (vice coal) [AESCN1] [EKACN2] in March 1941. Nereus (AC-10) was also sold into commercial service and vanished without a trace in the Bermuda Triangle with a cargo of bauxite ore in February 1941. Neither ship was lost due to enemy action. The fourth sister, Jupiter (AC-3) was converted into the U.S. Navy’s first aircraft carrier, Langley (CV-1) in 1922. (For more on the loss of Cyclops please see H-Gram 016/H-016-4.)

1921. Conestoga (AT-54)—fleet tug, commanded by Lieutenant Ernest Larkin Jones

Commissioned on 10 November 1917, Conestoga conducted towing and escort duties along the U.S. East Coast and near the Azores in WWI. Conestoga departed Mare Island, California, on 25 March 1921 bound for Samoa via Pearl Harbor and disappeared. Due to a breakdown in communications, no one knew she was missing until she was two weeks overdue at Pearl Harbor. Although the search was immense, no confirmed trace of the ship or crew was found. The wreck of an unidentified ship was found just off the Farallon Islands (off the entrance to San Francisco Bay) in 2009. A joint National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) mission in 2015 confirmed the wreck was Conestoga. This also confirmed Conestoga had not gone very far; the search was not initiated until almost a month after her loss and was conducted in the wrong places. The location of the ship suggested she was trying to reach the comparative safety of a cove in the Farallones as a result of heavy seas and high winds noted the day she left San Francisco Bay. (Please see attachment H-060-1 for more images and detail on Conestoga.)

1928. S-4 (SS-109)—S-class submarine, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Roy H. Jones

S-4 was commissioned on 19 November 1919. Commencing on 18 November 1920, S-4 transited with Submarine Divisions 12 and 18 on what was then the longest transit by U.S. submarines, from Newport, Rhode Island, to Cavite, Philippines, via the Panama Canal and Pearl Harbor. On 17 December 1927, while surfacing near Provincetown, Massachusetts, S-4 was accidentally rammed and sunk by Coast Guard destroyer Paulding (CG-17, formerly USN DD-22) on Rum Patrol. Six crewmen survived the sinking but were trapped in the submarine at a depth of 110 feet. Although the survivors communicated with rescuers on the surface by tapping on the hull in Morse code, foul weather thwarted heroic rescue attempts (diver Chief Gunner’s Mate Thomas Eadie was awarded a Medal of Honor) and all six survivors perished with the 34 other crewmen. S-4 was subsequently raised on 17 March 1928 by an effort led by (future Chief of Naval Operations) Captain Ernest J. King. S-4 was repaired and recommissioned on 16 October 1928. Decommissioned in April 1933, she was subsequently deliberately sunk on 15 May 1933.

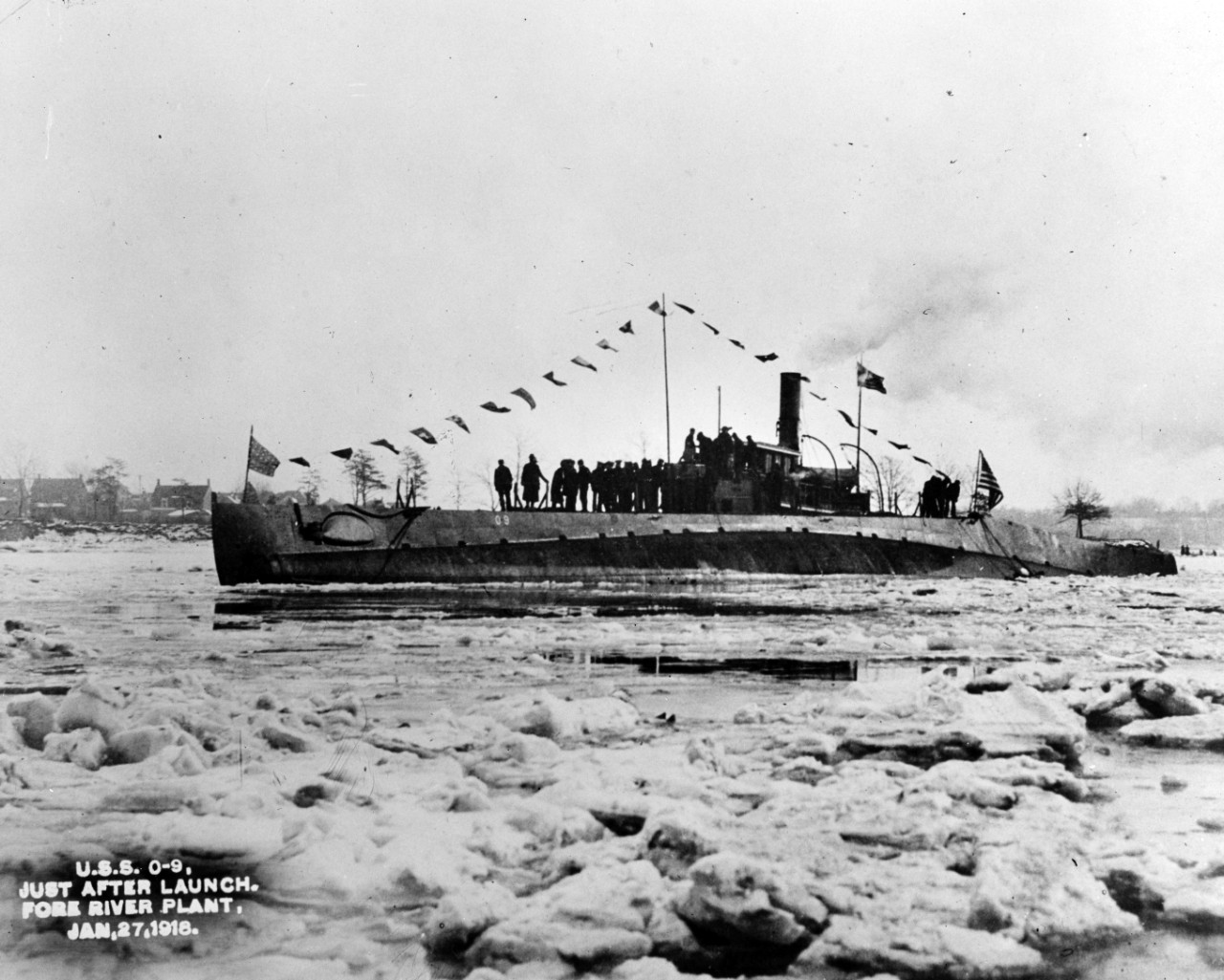

1941. O-9 (SS-70)—O-class submarine, commanded by Lieutenant Howard Joseph Abbott

First commissioned in 1918 and decommissioned in 1931, O-9 was recommissioned on 14 April 1941 along with seven other O-class boats to serve as training vessels in anticipation of the Second World War. O-9 was prone to mechanical problems even after extensive repairs. On 19 June 1941, O-9 along with O-6 (SS-67) and O-10 (SS-71) departed New London, Connecticut, for the test depth training area off Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 450 feet of water. On the morning of 20 June, O-6 and O-10 made successful dives. O-9 then submerged and never came up. Rescue attempts immediately commenced with limited prospect of success as O-9’s crush depth was 212 feet. Divers reached the sub on 21 and 22 June, setting depth and endurance records, but the submarine’s hull had been completely crushed aft of the conning tower and there was no chance that any of her 33 crewmen had survived.

1944. S-28 (SS-133)—S-class submarine, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Jack Gordon Campbell

Commissioned in 1923, S-28 survived seven war patrols during WWII, mostly in the Aleutian and Kuril Islands of the North Pacific. In October 1943, she commenced training duty out of Pearl Harbor. On 4 July 1944, S-28 was engaged in antisubmarine warfare training with U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Reliance (WSC-150). As the exercise concluded, contact between the two vessels became sporadic until 1820, when contact was lost. An extensive search eventually located an oil slick in the area of her loss, but the depth exceeded the equipment of the time. The submarine and her crew of 42 were declared lost, and a court of inquiry was unable to determine a cause. Although this occurred in wartime, there was no evidence of enemy action. The remains of S-28 were found in 2017 at a depth of 8,500 feet by Tim Taylor of the Lost 52 Project, and identity of the submarine was confirmed by NHHC.

1944. Mount Hood (AE-11)—Mount Hood-class ammunition ship, commanded by Commander Harold Agnew Turner

Although 18 crewmen survived because they were ashore, everyone who was actually aboard Mount Hood was obliterated when the 3,800 tons of ammunition aboard blew up by accident in Seeadler harbor, Manus Island, Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea, on 10 November 1944. Of 350 men aboard Mount Hood or alongside in small boats, no human remains were found. Everyone topside on the nearby repair ship Mindanao (ARG-3) were killed along with more inside the ship for a total of 82 dead. The blast sank or damaged beyond repair 22 small boats and amphibious craft, and damaged numerous other ships in the harbor, wounding another 371 personnel. The Board of Inquiry concluded that the most likely cause of the explosion was “careless handling of ammunition aboard ship.” (For more on the Mount Hood disaster please see H-Gram 039/H-039-5.)

1963. Thresher (SSN-593)—Thresher-class nuclear fast attack submarine, commanded by Lieutenant Commander John Wesley Harvey

Commissioned on 3 August 1961, Thresher was lost on 10 April 1963 during deep dive trials off Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Thresher was the first nuclear submarine lost at sea. Lost with the submarine were 129 personnel (112 crew and 17 shipyard personnel), making Thresher’s loss the second-deadliest submarine accident. (130 men were lost aboard French submarine Surcouf, which disappeared on 18 February 1942, possibly after a collision with a U.S. merchant ship.)

1968. Scorpion (SSN-589)—Skipjack-class nuclear fast-attack submarine, commanded by Commander Francis Atwood Slattery

Commissioned on 29 July 1960, Scorpion was lost with all 99 of her crew on 22 May 1968 about 400 nautical miles southwest of the Azores while returning from a Mediterranean deployment. Debate about the cause of her loss still rages on the internet along with conspiracy theories. The chance that she was sunk by the Soviets is about zero. She was one of four submarines that disappeared in 1968. That same year, Soviet Golf-II diesel-electric ballistic missile submarine K-129 went missing in the Pacific and its wreck was located by Halibut (SSN-587), followed by a partially successful top secret (at the time) recovery of the submarine by the Glomar Explorer (Project Azorian). Also in 1968, Israeli submarine Ins Dakar disappeared in the Mediterranean (wreckage located in 1999), and French submarine Minerve (S-647) went missing near the Port of Toulon (wreckage located in 2019).

Sources:

“U.S. Navy Ships Lost in Selected Storm/Weather Related Incidents.” (NHHC)

“Missing and Presumed Lost,” by James P. Delgado in Naval History Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 4, August 2016.