Maine I (Second-Class Battleship)

1895–1898

First U.S. Navy ship named for the 23rd state, admitted to the Union in 1820.

(Second-Class Battleship: displacement 6,682 (normal); length 324'4”; beam 57'0"; draft 21'6"; speed 16.45 knots (trial); complement 374; armament 4 10-inch, 6 6-inch, 7 6‑pounders, 8 1‑pounders, 4 18-inch torpedo tubes, 4 Gatling guns; class Maine)

Maine was authorized by an Act of Congress on 3 August 1886. Initially designated Armored Cruiser No. 1, the ship represented the changes in the United States Navy and the nation more generally. The U.S. had only recently started the so-called “New Steel Navy” with three cruisers (Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago) and a dispatch boat (Dolphin) laid down in 1883. Maine constituted a partial response to the growth of South American navies, especially the British-built Brazilian armored cruiser Riachuelo, the most powerful ship in the western hemisphere in the mid-1880s. Maine was the largest ship designed by the U.S. Navy at the time, and naturally had teething issues as naval architects designed the ship. Steam power, though long a part of the U.S. Navy, was new enough that Maine was initially designed to employ sails and rigging in addition to coal-powered engines. The sails were dropped mid-way through the design stage.

The Bureau of Construction and Repair approved Maine’s plans on 1 November 1887. The Navy opened bidding for materials on 4 June 1888 and soon signed a contract with Messrs Carnegie, Phipps & Co. of Pittsburgh. The Navy contracted with N.F. Palmer, Jr. & Company’s Quintard Iron Works at New York for Maine’s machinery. She would be powered by a pair of vertical triple-expansion engines of the Navy’s design, capable of producing nine thousand horsepower. Her keel was laid down at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 17 October 1888 and the first rivet driven at 11:00 a.m. on 2 November 1888. The ship had a distinctive design, featuring two large hydraulically powered turrets with 10-inch guns. The 6-inch and 6-pounder guns lined the broadside. In order to allow all main guns fire to forward and aft, the two 10-inch gun turrets were placed off of the centerline, one to the starboard and one to the port. This gave the ship a distinctively lopsided look as the turrets hung slightly over the edge of the hull and allowed heavy forward firepower that would facilitate ramming as generally accepted by naval tactics at the time.

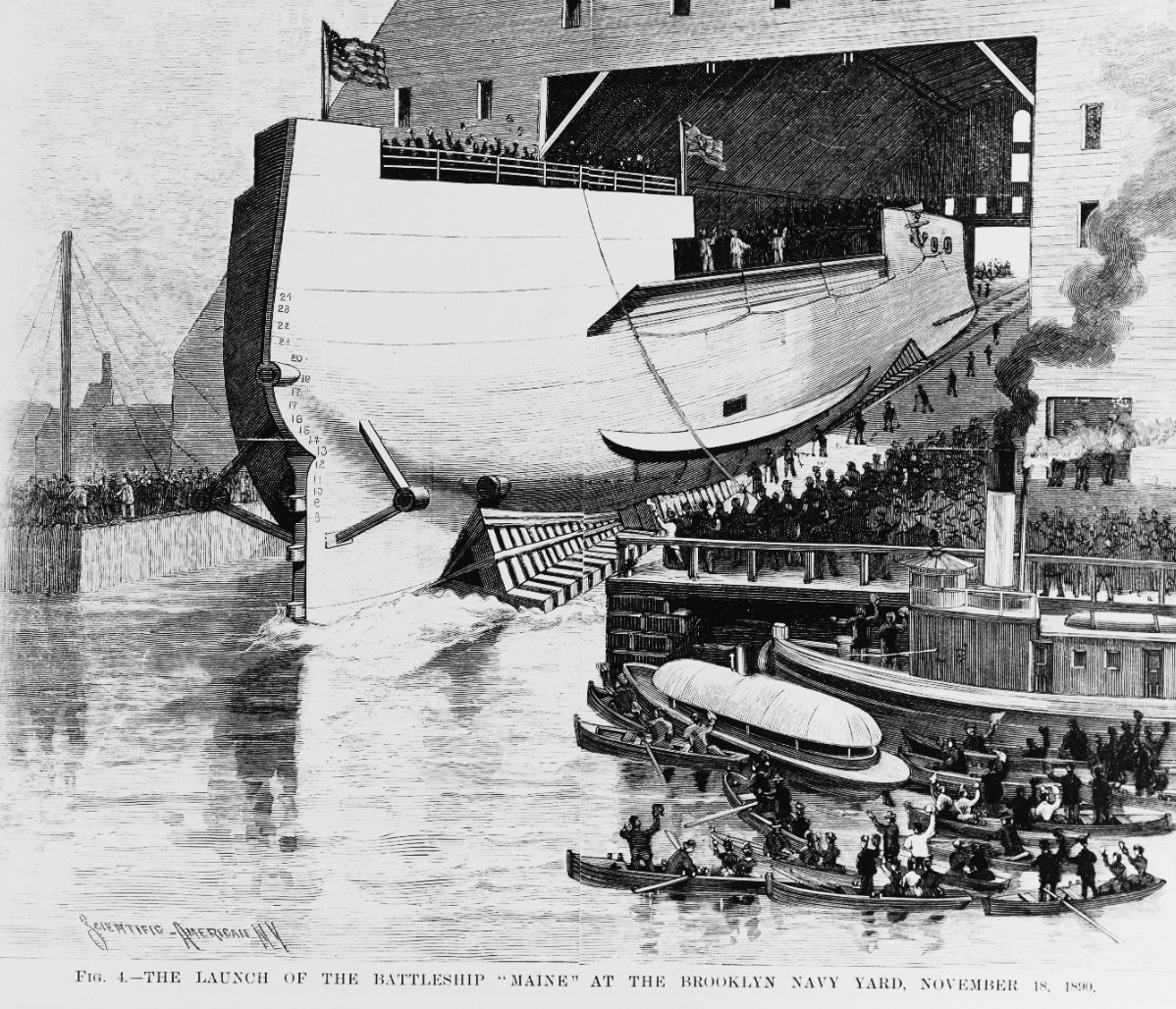

Maine was launched on 18 November 1890. Twenty thousand people attended the launching ceremony overseen by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Tracy, whose granddaughter, 12 year-old Alice Tracy Wilmerding, christened Maine with a bottle of champagne from San Bernardino, California. Workmen removed the keel blocks at 11:00 a.m., and Maine slid into the East River. At the time of launch, the ship was the largest ever built in a U.S. Navy Yard. It took almost five years for Naval Constructor William L. Mintoyne of the Bureau of Construction and Repair and the various other naval bureaus to complete the ship. When launched, the machinery and boilers were still under contract with N.F. Palmer Jr. & Co. of New York. Since American industry was not fully ready to equip a battleship, it took time for U.S. companies to produce the engines, armament, and fittings. The armor alone required three years due to the difficulties in procuring nickel and steel. Some of Maine’s fittings were new technology and thus particularly hard to acquire. For example, the ship needed four hundred light fixtures, just over a decade after Thomas Edison had built the first incandescent lightbulb. The ship also needed a huge number of accoutrements. According to the Secretary of the Navy’s annual report for 1896, in 1895 alone Maine added the following: “side ladders, boat cradles, boats, planing decks, hatch canopy frames, stowage of torpedoes, clothes lockers, securing furniture, wire matting in dynamo room, ordnance and electrical storerooms, ventilation, voice tubes, magazines, shell rooms, ammunition trolleys and hoists, forward turret, spars, lower booms, blocks, awning stanchions, cleaning, calking, docking, painting, and drawings. New raised manhole rings and covers were begun and completed ready to place on board, but were afterwards shipped to Norfolk.”

Maine was finally commissioned at her building yard on 17 September 1895 as a Second-Class Battleship. Captain Arent S. Crowninshield, a New Yorker and Civil War veteran, took command of the new battleship. Chaplain John P. Chidwick later recalled Crowninshield, writing “no clearer-minded, or more generous-hearted, or tender yet stronger character ever wore a naval uniform than this same Captain Crowninshield, and it was not long before he became beloved by officers and men; winning the respect and esteem of all his command.”

The commissioning ceremony took place at 2:00 p.m. Officers and men formed up in a hollow square, and Crowninshield read his orders and told the crew: “I will now expect every man to do his duty.” As one of the Navy’s newest and largest ships, duty on board Maine was a prestigious assignment, given to rising naval stars like Lieutenant Commander Adolph Marix, the executive officer, the first Jewish graduate of the Naval Academy, Lieutenant George Holman, the navigator, and others. Chaplain Chidwick, one of the first Roman Catholic chaplains in the Navy, was assigned to Maine at her commissioning.

Maine became the home of 31 officers and 346 sailors and marines, men recruited from across the United States. Almost a quarter had been born outside the country, reflecting the heavy pace of immigration around the turn of the century. Maine had multiple crewmen from Ireland, Sweden, Germany, Japan, Norway, Denmark, Canada, England, Finland, and Greece, and a single crewman each from Iceland, Romania, Russia, France, and Malta. Of the foreign born, all but eighteen were U.S. citizens or permanent residents who intended to become citizens. Thirteen were registered resident aliens, and five were unregistered foreigners.

Once commissioned and manned, however, the ship still needed work. Apprentice First Class Ambrose Ham confided to his personal log that “it took nearly two weeks to get things straightened proper.” The crew stayed on board the receiving ship Vermont for the first few days after commissioning, going to the Maine to work, but eating and sleeping on board the accommodation vessel. The crew moved on board Maine on 21 September 1895. Once fully loaded, Maine drew three more feet forward than aft, so forty-eight tons of cement were added to the rear of the ship to correct the imbalance.

While the fitting-out proceeded at the New York Navy Yard, the crew experienced some disciplinary problems ashore, especially with the city’s abundance of bars and other attractions. Thirteen crewmen went over allotted leave by 3 October 1895. Soon the crew was no longer allowed liberty. Other disciplinary problems included when Fireman Harry Auchenbach threw a man overboard. Fortunately, the man survived, but Auchenbach was demoted two rates. While the crew was working or fighting, the Navy used one of Maine’s launches to test “liquid fuel,” i.e. oil. Seventeen new men reported aboard on 7 October. Maine finally left the New York Navy Yard on 4 November and anchored in Sandy Hook Bay in New York Harbor.

On 5 November 1895, Maine departed for Newport, Rhode Island, but took her time trying out the ship’s equipment in Gardiner’s Bay on the eastern tip of Long Island, New York, and she arrived at her destination on the 17th, where the ship was fitted out and tested torpedo equipment. A week later, on 24 November, Maine departed Newport and reached Portland, Maine the next day to meet with Governor of Maine Henry B. Cleaves, and to receive a set of three silver dishes with covers and a case, estimated at $1,085 in value, as well as two photo albums with “view[s] of Maine Scenery” valued at $100 apiece.

At the time, ships would often receive a silver service, including a punch bowl. The punch served onboard was usually alcoholic. However, Maine was a prohibition state, so the governor and representatives of its citizenry presented the ship with a silver “soup tureen.” Chaplain Chidwick recalled later that from then on, Maine “provided for our guests, aboard ship, a peculiar quality of soup, of which the soup tureen was never empty; a soup which had neither vegetables nor meat as component parts. It was exceedingly cheerful in spirit and seemed to be the constant centre of attraction to the guests who favored us by their presence.” Maine stayed at Portland until 29 November, receiving civilian visitors on the 28th.

Leaving her namesake, Maine spent the first weeks of December 1895 in and around Newport at sea on trials and inspection. The battleship was assigned to Rear Admiral Francis M. Bunce’s North Atlantic Squadron on 16 December. She left Newport on 22 December and went to Tompkinsville, N.Y. on the 23rd. The next day, she left for Hampton Roads, Virginia, home of the Atlantic Squadron, arriving on Christmas Day. The ship spent a few days at Newport News, returning to Hampton Roads for tactical drills on 29 December. These continued until 9 January 1896, when Maine headed out to sea, stopping at Newport News on the 10th before returning to Hampton Roads on 11 January. The ship remained in port until 30 January, when she left Hampton Roads to go to Newport News again, moving on to Norfolk on 1 February. Maine returned to Hampton Roads on 5 February, briefly traveling to Newport News on 6 March, before returning to Hampton Roads on 7 March. On 10 March, she went out to sea for target practice in Chesapeake Bay, returning to Hampton Roads on the 12th. After staying in port until 7 April, for a brief trip to Newport News, she returned to Hampton Roads on 8 April, remaining there until the 21st. Maine spent 25 March to 29 May in the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., for repairs. Once that work was completed, Maine went to Hampton Roads on 2 June, before she set course for Key West, Florida, on the 4th, reaching her destination on 8 June before embarking upon on a two-month long training cruise.

On 30 July 1896, Maine left for Norfolk, arriving on 2 August. From 3 to 25 August the ship stayed in dock at Norfolk. On 11 August, William Cosgrove, a Navy Yard employee suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on board Maine, the first death on board the ship. On the 25th, Maine left for Tompkinsville, N.Y., arriving the next day. On 1 September, she joined her squadron for drills, which took the next few days. The ship anchored off Fishers Island, N.Y., from 4 to 16 September before heading out to sea. On 19 September, she anchored off Lighthouse Point, Tompkinsville, New York, staying there until 1 October. On the 2nd, the ship left for Hampton Roads, arriving there on the 5th.

On 13 October 1896, Maine headed north and arrived at Tompkinsville for more squadron drills, which took place from 14 to 23 October. On the 23rd, Maine went to the New York Navy Yard, staying there until 27 November, when she anchored at Tompkinsville. Maine spent almost another month in the New York area, finally heading out to sea on 21 December, stopping by Newport News the next day, and anchoring at Hampton Roads on the 24th. She spent almost a month at Hampton Roads quarantined during a smallpox epidemic. To combat the boredom, the crew organized a minstrel show and ball, together with the crew of Columbia (Cruiser No. 12) which also lay quarantined. Maine then coaled at Lambert’s Point, Virginia on 21 January 1897, and returned to Hampton Roads.

On 4 February 1897, Maine left port, heading for Charleston, S.C. While en route, she encountered a severe storm, “blowing [a] fresh gale from S.E.” with “heavy squalls of wind and rain.” Lieutenant George Blow, coming off duty at the end of the morning watch at 8:00 a.m., declared to Chaplain Chidwick that “this is one of the worst storms that I have ever seen.” At 8:15 a.m., Apprentice Second Class L.C. Kogel was, as reported by the log, “washed overboard while securing accommodation ladders in port gangway.” Third Class Gunner’s Mate Charles Hassel was washed overboard while attempting to save Kogel. Landsman William Creelman jumped overboard and “endeavored to pick up” Kogel. Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Friend W. Jenkins, now on duty, ordered life buoys released and the engines stopped.

Captain Crowninshield arrived on the bridge, ordered the starboard engine reversed and a whaleboat, commanded by Naval Cadet Walter R. Gherardi, to rescue the floundering men, the latter evolution extremely difficult in the stormy seas. Unfortunately, Kogel sank in about two minutes, but Creelman and Hassel managed to reach a life buoy. Meanwhile, waves swept marine Private A.B. Nelson and Seaman John Brown off the quarterdeck, never to be seen again. Naval Cadet Gherardi and the whaleboat were unable to make any progress towards Creelman and Hassel, so Maine picked up the whaleboat’s crew around 9:00 a.m. and took the boat in tow, only to have the whaleboat to break adrift “soon afterward.” At 9:25 a.m., Maine herself rescued Hassel and Creelman. As the log put it succinctly, though, “Kogel, Brown, and Nelson were lost.” Chaplain Chidwick visited the rescued men in the sick bay, where, according to Chidwick, Hassel credited his Catholic scapular and prayers to the Virgin Mary for his salvation.

The storm abated by 7 February 1897, and Maine reached Charleston on the 8th. She spent the next week steaming in squadron. Maine returned to Port Royal for coal on the 18th, before heading out again on 21 February, this time for a port visit to New Orleans, Louisiana. Maine and Texas (Second-Class Battleship) arrived in New Orleans on 25 February to represent the Navy at Mardi Gras. There Maine saluted nearby French cruisers L’lphigenie and Dubordieu, and welcomed visitors from the city and the Army.

Maine’s sailors also participated in Mardi Gras celebrations, so much so that the ship’s log entry for 1 March 1897 notes that of 72 men given liberty the day before, 39 did not return for morning muster. That day the ship fired a 21-gun salute for the “King of Carnival,” which was echoed by the visiting French warships. On 10 March, as Maine was preparing to leave the city, ten “natives of Maine now residing in New Orleans” presented a nine-inch tall silver trophy to Captain Crowninshield, who had the cup entered onto the ship’s books with the estimated value of $200. On 11 March, Maine stood out to sea, and joined Texas for maneuvers off Port Royal, South Carolina on the 16th. Exercises completed, the ship left Port Royal on 3 April, headed for Newport News. Maine helped to look for a wrecked ship on 5 April, and then went to the Norfolk Navy Yard on the 6th for repairs.

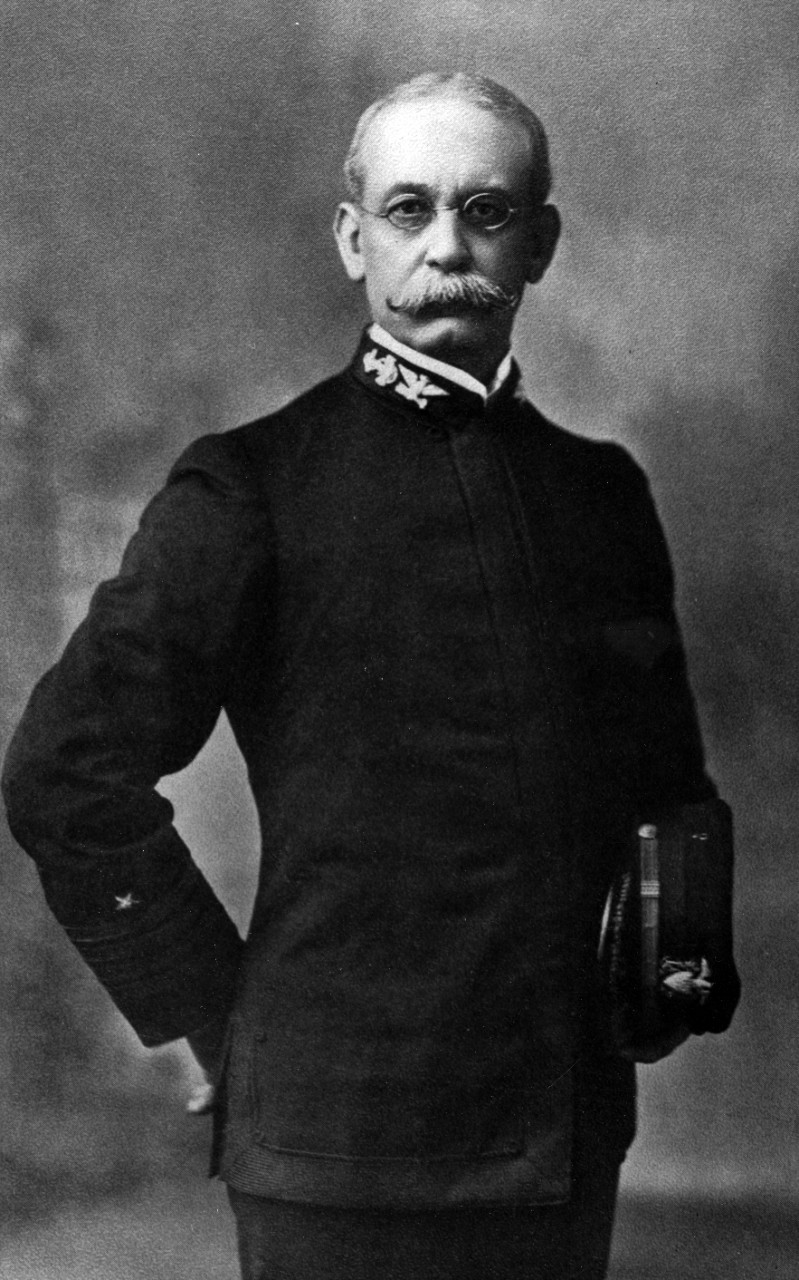

Maine stayed at the Navy Yard until 15 April 1897, and while there saw her first change of command, when, on 10 April, Captain Charles Sigsbee relieved Captain Crowninshield as commanding officer, the latter moving on to serve as Chief of the Bureau of Navigation. Sigsbee, born in Albany, New York, had graduated from the Naval Academy in 1863, and fought in the Civil War, notably taking part in Admiral David Glasgow Farragut’s attack at Mobile Bay. Sigsbee spent much of his career as an oceanographer and commanded several coastal survey missions, including a deep water survey of the Gulf of Mexico. Known as a professional and technical expert, he occasionally struggled with command. An inspection of the sloop Kearsarge in 1886, for example, found that Sigsbee had not drilled the marines sufficiently and that the ship was dirty.

For the next few months, Maine would continue operations along the eastern seaboard, mostly conducting training of naval militia. On 17 April 1896, Maine joined New York (Armored Cruiser No. 2) at Hampton Roads, and then headed to New York City, arriving at Tompkinsville on 20 April. Maine anchored off 30th Street, New York City, on 29 April. From 3 May to 22 June, the ship was moored at the New York Navy Yard for repairs. Once completed, the ship anchored off 42nd Street, North River, New York City, on 23 June, before heading for Hampton Roads, arriving there on 25 June.

Maine stayed at anchor in and around those waters until putting to sea on 3 July 1896, and reached the Delaware Breakwater on the 4th. The next day, the ship met three divisions of the Pennsylvania Naval Militia at Newcastle, Delaware. From 7 to 9 July, the militia drilled on board Maine off of Woodland Beach and the Delaware Breakwater. On the 9th, Maine dropped off the Pennsylvania Militia and headed to New York City. She anchored in Sandy Hook Bay, New Jersey and Tompkinsville, N.Y., from 11 to 17 July. On the 17th, Maine proceeded to New London, Connecticut. On 19 July, Maine went to Fishers Island, N.Y., to pick up units from the Naval Militia of Connecticut. The militiamen drilled for four days on board Maine. Unfortunately, foggy weather prevented the militia from firing practice with Maine’s guns. Lieutenant Commander Marix, Maine’s executive officer, reported afterward that the “four days on board the Maine were well utilized, and undoubtedly very beneficial” to the militia, but not long enough. The ship dropped off the militiamen at Fishers Island on 23 July before going to New London. Maine returned to Fishers Island on 26 July to pick up the Battalion of the East, of the New Jersey Naval Militia. The militia drilled on board Maine until 28 July and were able to fire the 6-inch and secondary guns at a moving target. Marix, perhaps weary of dealing with militiamen, wrote that their discipline on Maine “was as good as could be expected from such an organization.”

On 28 July 1896, Maine headed to Tompkinsville. The next day, 29 July, Captain Sigsbee took the ship into New York Harbor. A trained oceanographer, Sigsbee was qualified to pilot his own ship, and did so as Maine headed up the East River. Unfortunately, the river was crowded with barges and ferries, including the steamer Isabel, with eight hundred members of the Alligator Club of Newark on board. Sigsbee signaled for the steamer to get out of the way, but it was unable to change course. Thinking quickly, Sigsbee turned the ship towards shore, hitting Pier 46. The pier was completely destroyed, but Maine only lost some paint. A naval board investigated Sigsbee’s actions, and though his decision to pilot his own ship in a crowded harbor was not ideal, he received a letter of commendation for saving many lives by hitting the pier instead of the ferry.

After the collision, Sigsbee took Maine to the New York Navy Yard, where the ship was found to have no significant damage, before proceeding to Tompkinsville for the night. The ship went to Jamestown, R.I., on 2 August 1896, and anchored at Newport the next day. On 11 August, the ship left for Portsmouth, N.H., arriving the next day. On the 16th, Maine went to Portland, Maine, staying there for a week. On the 24th, Maine anchored off Bar Harbor, Maine. On 31 August, the ship headed for Hampton Roads, arriving there on 3 September, before anchoring off the Southern Drill Grounds for naval maneuvers with the North Atlantic Squadron. On 12 September, Maine went to sea and anchored at Fort Monroe until the 23rd, heading to Newport News and returning to Hampton Roads on the 25th. Maine attended the 115th anniversary of the Battle of Yorktown, arriving off the battlefield on 27 September, and staying until 3 October in order to conduct maneuvers, including a mock battle near the Yorktown battlefield. From 4 to 5 October, Maine stayed at the Chesapeake Bay Anchorage and then proceeded to the Southern Drill Grounds off Hampton Roads, staying until the 9th. The next day, Maine was ordered to Port Royal, S.C., in order to put a powerful U.S. warship closer to the Spanish colony of Cuba.

Throughout much of the 19th century, Spain had fought a brutal counterinsurgency against Cuban revolutionaries seeking independence. Cuba openly rebelled against Spanish rule in 1895. American newspapers and the public became increasingly worried about Spanish abuses of Cuban civilians, particularly as Cuba was governed by General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau from 1896-1897. Nicknamed “the Butcher” by the American press, Weyler instituted a policy of reconcentration—forcing civilians out of the countryside to live in camps, towns and forts controlled by Spanish forces. Designed to deny the insurgency access to the population, reconcentration decimated Cuba, killed hundreds of thousands of civilians, failed to end the insurgency, and inspired the use of similar concentration camps across the world. The U.S. government struggled to know how to deal with the humanitarian and diplomatic complexities of the situation, and the Cuban crisis proved a major political issue in the 1896 election of President William McKinley. Weyler was recalled in October 1897 by a new liberal government in Spain, which also granted Cuba a degree of autonomy and replaced Weyler with Captain General Ramón Blanco y Erenas. While the changes were an improvement, Cuba was still unstable, and U.S.-Spanish relations remained tense. Maine received orders to be ready to intervene or assist U.S. citizens and interests on the island as decided by President McKinley.

Maine stayed at Port Royal from 12 October until 15 November 1897. Despite the ship’s looming mission, Sigsbee remarked later that “we had a dull time” there. After leaving Port Royal, the ship sailed for Hampton Roads, arriving on 17 November. For the next several weeks, the ship bounced back and forth between Hampton Roads, Newport News, and Norfolk, Virginia, undergoing some repairs at Norfolk. While there, on 7 December, Lieutenant Commander Richard Wainwright relieved Lieutenant Commander Marix as executive officer. Wainwright had recently served in the Office of Naval Intelligence, and came to Maine highly recommended by his superiors. He also came with a good knowledge of U.S. strategic needs and the situation in Cuba.

On 11 December 1897, Maine stood out of Hampton Roads for Key West, filling up with bituminous coal at Newport News before heading south. Bituminous coal can spontaneously combust, but was a preferred fuel over anthracite. Maine arrived at Key West on the 15th and conducted target practice en route. She was joined there by ships of the North Atlantic Squadron on maneuvers, as part of the U.S. efforts to monitor the situation in Cuba. Maine would stay in and around Key West until 23 January 1898; while there, her baseball team engaged “in several spirited games with the local team.” Fireman Second Class William Lambert, an African American sailor, served as the team’s pitcher.

While on patrol, Maine waited for a call for help from U.S. Consul General Fitzhugh Lee, in Havana. Lee had a strong Southern pedigree, coming from a long family of slave holders, was Robert E. Lee’s nephew, became a Confederate cavalry general, and served as Virginia’s governor (1886-1890). President Grover Cleveland appointed him consul general to Cuba in 1896 and he was retained in the position by President McKinley. Lee and Captain Sigsbee arranged a series of code words in case Maine was needed. If Lee ever telegraphed the phrase “two dollars” to the Key West Naval Station, Maine would prepare to sail within two hours. If Lee sent “vessels might be employed elsewhere” Sigsbee would sail for Havana immediately. Sigsbee and Lee communicated almost every day for a month to keep the telegraph lines open and eliminate suspicion if Lee sent an unusual signal. Some of these wired conversations were strange, like when Sigsbee asked Lee about the weather in southern Cuba, to which Lee responded he didn’t know.

Concerned by riots in Havana, Secretary Long warned Sigsbee on 7 December 1897 that Maine, still at Norfolk, might be needed to go to Cuba to protect American lives and property, at the call of Consul General Lee. Lee sent Sigsbee the preparatory “two dollars” message on 12 January 1898 in response to pro-Weyler riots in Cuba in mid-January. Sigsbee accordingly recalled the crew, prematurely ending a baseball game. Lee never sent the actual request for the ship, as the riots died down after a few days. Maine remained in Key West for the next two weeks, sending boats to assist in catching filibusters, Americans running guns and supplies to the Cuban insurrection.

Maine joined Rear Admiral Montgomery Sicard’s passing North Atlantic Squadron on its way to the fleet anchorage at the Dry Tortugas on 23 January 1898. Coal Passer Thomas Troy wrote home that day that “we are going to stay down south here, I think a good while. The whole fleet of ships is maneuvering and drilling at sea.” He reported that a rumor on board predicted the ship would go to Havana, but “the order was postponed.” Instead, “we are watching for filibusters here in Key West since we came here—I mean ships that were smuggling arms and ammunition down to Cuba.”

By late January 1898, President McKinley and Secretary of the Navy Long felt that the U.S. Navy should resume port visits to Havana, as the worst atrocities against Cuban civilians were starting to come to an end. Cuba was now theoretically autonomous, and other ships from friendly or neutral nations frequently visited the city. McKinley and Long also feared for the safety of American civilians and property in Cuba in the face of a still unstable situation on the island. They decided to send Maine to Cuba on 24 January, independently of Consul General Lee. After checking with the Spanish Ambassador in Washington, D.C., Long ordered the ship to Havana, reasoning that although no U.S. Navy vessel had gone to Cuba for years, “the necessity of providing protection to American interests made the presence of our flag in Cuban ports desirable.” Assistant Secretary of State William R. Day informed Lee on 24 January that the government intended to “resume the friendly naval visits at Cuban ports. In that view the Maine will call at the port of Havana in a day or two. Please arrange for the friendly interchange of calls with authorities.” Lee responded, asking to delay the visit by six or seven days “to give last excitement more time to disappear. Will see the authorities and let you know.” Maine was already underway when Lee sent this telegram.

The North Atlantic Squadron anchored at the Dry Tortugas at 11:00 a.m. on 24 January 1898. While most ships banked their coal, Maine kept her boilers ready in case of a call from Havana. Du Pont (Torpedo Boat No. 7) arrived in the evening, bringing orders for Maine to proceed to Havana. After consulting with Admiral Sicard, Sigsbee and Maine set out. Seaman Frank Andrews wrote to his father when Maine left for Havana that “when orders were received to proceed to Havana, we saw that all our guns were in good order, cylinders filled, shot and shell out, and the decks almost cleared for action. Everything was ready for business and we turned in for a couple of hours sleep.”

Maine took her time on the way to Havana so as not to arrive before dawn. Uniform of the day was dress blues for the men and frocked coats for the officers. Relations between the United States and Spain were tense, so when Maine arrived in Havana, the ship was prepared for a fight. Lieutenant Carl W. Jungen recalled later that “to guard against any possible hostile demonstration upon our entrance into Havana Harbor, everything was gotten in readiness for immediate action…Shells were placed in the turrets for the main battery, also the six-pounders, as well as the one-pound guns…all arms ammunition was stacked for immediate use in the armory, while the powder charges for the guns remained in the magazines, of course, put ready for instant use.”

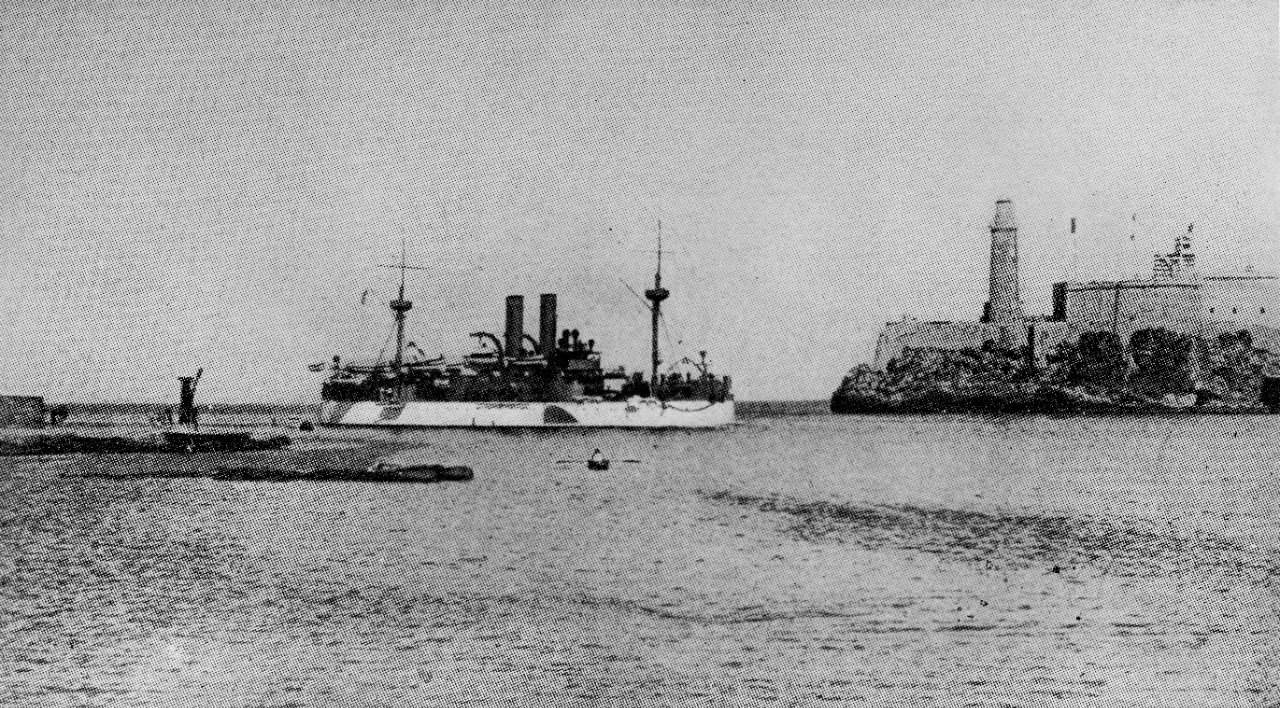

Arriving at 9:30 a.m. local time on 25 January 1898, Maine stood in to Havana Harbor where Julian Garcia Lopez, a Spanish pilot, came on board and directed the ship to buoy number 4, in 5 ½ to 6 fathoms of water in the center of the port. At 10:00 a.m., the ship anchored between the German square-rigged school ship Gniesnau and the Spanish unprotected cruiser Alphonso XII. Once the ship had settled in at the buoy, Sigsbee sent Naval Cadet Wat T. Cluverius to Consul General Lee to arrange a meeting with Spanish Rear Admiral Don Vicente de Materola y Tasconera, the commander of Havana’s naval station, and Cuba’s governor, General Blanco.

Sigsbee ordered the crew to remain vigilant, allowed no shore leave, and took extra precautions against sabotage. He wrote later that “on board the Maine the greatest watchfulness was observed against measures of this kind; not that I believed we were likely to be blown up, but as a proper precaution in a port of unfriendly feeling.” Sigsbee and Wainwright kept the ship’s crew busy with extra drills. Wainwright thought the discipline was “fine,” though the crew needed more exercise. While in port, Maine was well guarded. Marine sentries were doubled and sailors kept a quarter-watch (one fourth of the crew was on deck at all times). All enlisted men were required to stay on board, for fear of precipitating an incident with anti-American Spanish residents of Havana. Officers were allowed to go ashore, but could not stay the night in the city. Still, stewards and, as Sigsbee put it, “certain Chief Petty Officers, entirely trustworthy men” were sent to shore as necessary, often with a market boat to purchase supplies. One officer, Lieutenant Jenkins, was tasked to collect intelligence on Spanish forces and dispositions around Havana.

Jungen and other officers went ashore on the third day of the Maine’s visit for a luncheon at the Havana Club where they surreptitiously inspected the harbor defenses and saw Cuban victims of Spain’s reconcentration policy. The officers got even more opportunities to go to Havana thanks to the hospitality of Spanish officers. Sigsbee visited acting Governor General Julián González Parrado on 27 January 1898 (Blanco being out of town), and Parrado returned the favor on the 28th. According to Lee, Parrado and his staff “inspected the Maine, were entertained and given the appropriate salute. [They] expressed pleasure at their reception and admiration for the splendid battle ship.” Sigsbee mentioned he had never seen a bull fight, so Parrado offered a box containing six seats for a fight starring Luis Mazzantini Eguia, described by one American officer as “the greatest living matador,” on Sunday, 30 January. Sigsbee, Lee, and Lieutenants Holman, Jungen, John Hood, and Naval Cadet Jonas H. Holden attended in civilian clothes to avoid inciting an incident. On the way, an American newspaper correspondent gave Sigsbee a pro-Weyler flyer that had been circulating in the city, calling for “death to the Americans! Death to autonomy! Long live Spain! Long live Weyler!”

Despite the flyer, Sigsbee reported that there was no demonstration from the people during his visit to the bullfight, but that Spanish officers watched him and the other Americans “with decidedly antagonistic looks.” Jungen recalled going to the bull fight years later, denouncing it as “a form of cruelty in which the Spaniards took delight.” Sigsbee and his party exited the bullfight early to avoid the crowds once the fight ended. While returning to Maine, some passengers on a passing ferry heckled the Americans with calls of “Viva España!” After some time in Havana, Sigsbee concluded that the feeling against the United States among the Spanish in Cuba was deeply, but quietly, antagonistic, and held in check by Maine’s presence. Naval Cadet Cluverius concluded that the Cuban population was pro-American, but could not risk openly supporting the United States out of fear of retaliation from Spanish loyalists and officials.

Meanwhile, the crew, isolated on board the ship, wrote home, sometimes expressing fear of the locals. Seaman Charles Denning wrote “if an American sailor went ashore he would not come back to his ship.” While his officers’ experiences prove him mistaken, it does reflect the mood on board the ship. Other sailors feared torpedoes and mines in Havana harbor. “I am ready to do my duty when called on,” Seaman Frederick Paige explained, “but I tell you it is not a pleasant feeling to sit here and think that the harbor is full of mines and that there are torpedoes on all sides. This is my first experience so close to war, but the old tars tell me that they do not trust the Spaniards, and would not be surprised if we had some trouble. But we are here, at anchor, and must stay to guard those we are sent here to protect.”

As a representative of U.S. power in an officially friendly port, Maine was open for visitors. Scores did, mostly well-off visitors of high social standing. The Cuban guests generally told the crew that they were in favor of the anti-Spanish insurrection. Visiting hours were somewhat limited, due to security concerns, and Sigsbee recalled that “Lieutenant-Commander Wainwright was rather severe on desultory visitors.” Wainwright later testified to a naval inquiry board that “all visitors were scrutinized by the officer of the deck before coming on board, and only those that were thought desirable were allowed to come on board.” Visitors were always “accompanied by a reliable member of the crew” and never taken to “intricate parts of the ship.” Very few Spanish sailors, soldiers, or officials visited Maine outside of official duties. Sigsbee could only recall two parties of Spanish officers visiting, one of which he described as “not desirous to accept much courtesy.”

As Sigsbee wrote to Secretary Long on 9 February 1898, “My official relations with the Spaniards here have been in all respects pleasant, but my efforts to get Spanish officers on board the MAINE in a social way, that is to convince them that they were welcome and would please me by visiting the ship have been entirely unavailing.” Despite social challenges, the Spanish ambassador in Washington thought that Maine was helping to normalize the situation in Havana, and was evidence that Spain’s policy of autonomy for Cuba was working. Lee thought that the Maine should stay for some time, and that if she were pulled out of the harbor, a “first-class battle ship should replace present one if relieved, as object lesson and to counteract Spanish opinion of our Navy.” All in all, according to President McKinley, Maine’s visit created a “feeling of relief and confidence [following] the resumption of the long interrupted friendly intercourse.” As February ground on, officers and men started to look forward to spending Mardi Gras in New Orleans again.

The 15th of February 1898 started out as a normal day. The 290 sailors, 39 marines, and 26 officers aboard ran through regular drills, and by the evening, many of the sailors took their hammocks topside to escape the hot berth deck. Naval Cadet Cluverius, Maine’s officer of the watch until 8:00 p.m. that evening, later wrote that the 15th was a “beautiful day, with a gentle northeast breeze blowing and the harbor full of craft.” Once relieved, Cluverius went to his quarters to write a letter, and heard the men “dancing in the starboard gangway to an accordion’s music. One of the gunners’ mates was playing a mandolin in the after turret.”

Lieutenant John J. Blandin, Maine’s officer on watch the night of 15 February 1898, walked around the deck of the ship and then sat by the starboard side of the after turret. Lieutenant John Hood happened by and “laughingly” asked if Blandin was asleep. “No,” he replied, “I am on watch,” and almost immediately the ship exploded, pelting the two officers by a “perfect rain of missiles of all descriptions, from huge pieces of cement to blocks of wood, steel railings, fragments of gratings, and all the debris that would be detachable in an explosion.” A piece of concrete knocked Blandin down, but, while dazed, he was uninjured. Hood ran to the poop deck to lower the boats.

Naval Cadet Cluverius was sealing his letter into an envelope when the explosion occurred. He heard a “report – the firing of a gun it seemed” followed by “an indescribable roar, a terrific crash, intense darkness and the deck giving way beneath.” He and his classmate, Naval Cadet Amon Bronson Jr., got out to the poop deck, while most of the crew, “pinned down and drowning, mangled and torn, screamed in agony.”

Marine Private William Anthony was on the main deck that evening, near the captain’s quarters. “I first noticed a trembling and buckling of the decks,” he later told investigators, “and then this prolonged roar—not a short report, but a prolonged roar. The awnings were spread, and where the wing awning and the quarter-deck awning should join there was a space of at least 18 inches. I looked out and saw an immense sheet of flame, and then I started in to warn the captain… It was such an immense glare that it illuminated the whole heavens for the moment.”

Maine exploded shortly after 9:40 p.m. on 15 February 1898 A tremendous magazine explosion tore the battleship apart and wrecked the entire forward part of the ship, splitting her open. Wainwright, Hood, and Naval Cadet David F. Boyd, Jr., trying to assess the damage a few minutes after the explosion, found that the front of the ship was nothing but a “mass of what appeared to be burning cellulose.” Out of 351 officers and men on board that night (4 officers were ashore), 252 died or went missing, including George Hassell, who had been washed overboard and rescued a year previously. Eight more died in Havana hospitals during the next few days. Many of the crew perished outright in the blast. Others died in the resulting fires and flooding, or drowned in the harbor. As the survivors scrambled to get off the ship over the next minutes, they faced the dangers of rising water, fire, and exploding ammunition.

The blast was visible across Havana and could be heard for miles. A pilot on board the nearby American Ward Line steamer City of Washington described the sound as “a noise as of many rockets” and also heard the “cries of the victims.” William H. Van Syckel, superintendent of the West India Oil Refining Company, heard a “terrible explosion,” and went outside to see that “everything was flying in the air. There were columns of black smoke, and pieces and parts of the ship.” Clara Barton, the founder of the Red Cross, happened to be in Havana on 15 February, assisting the victims of Spain’s reconcentration policy. At the age of 77, she was doing “heavy clerical work” in her office, “when suddenly the table shook from under our hands, the great glass door opening onto the veranda, facing the sea, flew open; everything in the room was in motion or out of place—the deafening roar of such a burst of thunder as perhaps one never heard before, and off to the right, out over the bay, the air was filled with a blaze of light, and this in turn filled with black specks like huge spectres flying in all directions. Then it faded away.”

On board Maine, officers and men struggled to escape the catastrophe that had descended upon them. Lieutenant Jungen, Lieutenant Jenkins and two other officers were in the officer’s messroom when they were stunned by the explosion. Jenkins headed forward, presumably intending to use a ladder to proceed topside. Unfortunately, in the darkness, he could not find his way out of the messroom. Jungen and the other two officers headed to a ladder further aft. While somewhat behind the others, Jungen recalled that “at the rate I was traveling, I did not lose a second in getting on deck.” He went through the captain’s cabin and got to the top of the after deck house where he met Captain Sigsbee and Lieutenant Commander Wainwright. After jumping from the deck to the water not far away, Jungen took command of one of the three surviving boats, and headed for the City of Washington, picking up two sailors on the way.

Lieutenant Commander Wainwright was talking to Naval Cadet Holden in the captain’s office when he “felt a very heavy shock, and heard the noise of objects falling on deck.” Surprised, Wainwright thought that the nearby Spanish cruiser Alfonso XII was firing on Maine and ran to return in kind. Once he arrived at the poop deck, though, he realized the ship was not under attack and shifted to getting the boats ready for launch, mostly using officers for the work. Throughout the disaster, the escape boats would be mostly manned by officers, due to the few surviving enlisted men.

Chaplain Chidwick, in his quarters when the explosion occurred, reached the upper deck, recalling later, “my impression was that war was on, that the enemy had engaged us, and that our deck would be swept with shells and bullets. The deck, however, was clear, but the forward part of the ship was ablaze and up from the waters and from the ship came the heart-rending cries of our men: ‘Help me! Save me!’ Immediately, I gave them absolution.” He then started to assist in rescuing the wounded, especially once Lieutenant Jungen told him “I think we can do better work now, Chaplain, by getting into the barge and rowing around to pick up some of the men.”

Lieutenant George Blow wrote to his wife on 16 February 1898 that “I can not write of the horrors now. Each man lived a lifetime of horror in a few seconds and all would like to forget it if possible.” He went on to tell her that “in my struggle in the darkness and water, you and the babies were in my mind, dearest.”

Naval Cadet Boyd was in the junior officer’s messroom, reading, when he heard “a crashing booming.” As the explosion shook the ship, a piece of wood hit him in the head, briefly knocking him unconscious. Upon regaining consciousness, Boyd and Assistant Engineer Darwin Merritt headed for the poop deck through a passage by the torpedo room. Unfortunately, as Boyd later recalled, a “rush of water swept us apart.” Merritt, a Naval Academy graduate and former halfback, drowned, but Boyd managed to clamber over pipes and torpedoes and through a hatch before water completely flooded the below deck space. He arrived on the poop deck and helped get boats into the water.

While all but two of the officers were able to get off the ship, the crew were mostly asleep in the forward half of the ship, where the explosion occurred. Only two enlisted men escaped from the lower decks. One of them, Coal Passer Jeremiah Shea of Haverhill, Massachusetts, explained his escape thus: “I think I must be an armor-piercing projectile, sir.” The other, Mess Attendant John H. Turpin, was below in the wardroom pantry. Turpin told a court of inquiry that he was sitting down when the ship lifted and heaved. “It was a jarring explosion – just one solid explosion, and the ship heaved and lifted like that, and then all was dark. I met Mr. [Lieutenant Friend] Jenkins in the mess room, and by that time the water was up to my waist, and the water was running aft. It was all dark in there.” Jenkins and Turpin could not find their way out of the pitch dark mess room. As water rose to Turpin’s chest a flash of light lit up the compartment, allowing Turpin to see Jenkins fall under the water. Turpin managed to get to the captain’s ladder out of the wardroom, but the ladder had been washed away. He explained, “by that time the water was right up even with my chin. Then I commenced to get scared, and in fooling around it happened that a rope touched my arm, and I commenced to climb overhand and got on deck.” Lieutenant Holman ordered Turpin to go below for cutlasses to repel suspected borders, but halted by flooding below decks, Turpin ended up jumping overboard and was rescued by a Spanish barge.

Some crewmen were tossed out to sea by the force of the explosion. Marine Sergeant Michael Meehan recalled, “I was simply thrown out in the water. When I left the ship I must have swam out, because when I came up I was about 15 or 20 feet from the side of the ship.” Others, like Landsman George Fox simply jumped overboard and swam, or tried to swim, to nearby boats. Coxswain Benjamin R. Wilber had both experiences. He was on the steam launch stored on board Maine when the ship exploded. The blast “seemed to me as if something hit me in the face, and I didn’t know any more until I came up under the water, some distance from the ship.” Fearing sharks, he swam twenty yards back to Maine before stripping and swimming to a Spanish cutter.

Many of the survivors saw their friends and shipmates killed in the chaos. Coal Passer Thomas Melville was heading through a passage between the galley and the turret when he saw Seaman Peder Laren, who disappeared. Melville later testified, “I couldn’t say how he disappeared. Of course, the shock took all the life out of me for a second—for half a second.” Melville continued on to the starboard gangway, where he saw Fireman First Class William Gartrell praying, and Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Luther Lancaster lying dead. Melville pulled another dead man out of the water, and left him. Earlier, Gartrell was in the steam steering room when the explosion occurred. While trying to escape the engine room, he and Coal Passer Frank Gardiner tried to escape. “The two of us jumped up, and I went on the port side up the engine-room ladder, and Frank Gardiner, he went up the starboard side – at least he didn’t go up, because he hollered to me…he says: ‘O Jesus, Billy, I am gone.’ I didn’t stop then, because the water was then up to my knees.” Gardiner did not survive.

Captain Sigsbee later wrote that “none can ever know the awful scenes of consternation, despair, and suffering down in the forward compartments of the stricken ship; of men wounded, or drowning in the swirl of water, or confined in a closed compartment gradually filling with water.” He thought, and hoped, that most of the crew was killed quickly.

At 9:40 p.m., the captain himself was in Maine’s admiral’s quarters along with his clerk Naval Cadet Jonas H. Holden, finishing up a report to the Navy Department on the employment of torpedoes, as well as a letter to his wife Eliza. On 17 February, he wrote to Eliza, describing his experiences the night of the explosion. “There was an awful moment of trembling and roar, then a tearing, wrenching, crunching sound of immense volume, so great that you cannot conceive it: then falling metal, a great wrench and twist and a heeling subsidence of the Vessel. There was instantaneous darkness and smoke filled my cabin. There was no mistaking it. I knew in the instant that my vessel had been destroyed.” Sigsbee couldn’t see anything out of the window and headed to the passage between the captain and admiral’s quarters where he ran into his orderly, Private Anthony. Anthony saw the captain, “apologized in some fashion” and reported that the ship had exploded. Anthony followed Sigsbee the rest of the night “with unflagging zeal and watchfulness” and would later be commended for staying at his post and promoted to sergeant major. Sigsbee and Anthony climbed to the poop deck, where Sigsbee conferred with Wainwright, Lieutenant Holman and other officers. Sigsbee, initially fearful of a boarding attack, told Wainwright to post sentries, but this quickly became obviously useless. Sigsbee also ordered the magazines flooded, but Wainwright pointed out that the ship was already sinking, and thus flooding the magazines was pointless. As the ship sank, “pitiful cries floated to us” and Sigsbee realized that the officers and men on the poop deck were practically the only able bodied people on board. Most of the ship’s small craft were destroyed in the explosion, so Sigsbee ordered the three remaining boats to be lowered to pick up men. Multiple witnesses describe perfect order and discipline among the officers and crew on the surviving portions of the ship.

Unfortunately, these boats did not have much luck in recovering crewmen in the water. Coal Passer Thomas Melville and Seaman Harry McCann ran aft after the explosion, intending to get to one of the whaleboats, which sank before they could get to it. Fortunately, Boatswain Francis Larkin came along in the captain’s gig and yelled at Melville and McCann to join him. As Melville later testified, “we dove overboard and swam for the cutter and manned her to save lives, which we couldn’t.” Larkin brought the gig back to the poop deck to pick up Sigsbee and the remaining crew on board. Sigsbee ordered the ship abandoned and was the last to board the final boat. Apprentice First Class Ambrose Ham recalled years later that Sigsbee said “I won’t leave until I’m sure everyone’s off” but finally left at Wainwright’s urging. By the time Sigsbee finally got off Maine, the battleship had sunk so far that the poop deck was level with the gig he boarded. Also, at some point in the chaos, a sailor retrieved Sigsbee’s dog, Peggy, and took her to a boat. Sigsbee wrote on 17 February, “poor little Peggy… trembled with fear long after she had been taken off the Maine.”

As men were flung or jumped from Maine, ships and civilians in Havana rushed to their aid. This was dangerous work. Jungen recalled that “the water for about thirty feet around the ship was strewn with wreckage.” In addition, Maine was still on fire, and cooking off ammunition. Spanish cruiser Alfonso XII sent boats out to rescue sailors almost immediately. Naval Cadet Cluverius recalled one Spanish boat that rescued forty sailors from Maine. Some sailors were able to swim to rescue boats. Seaman Mike Flynn had been in the forward section. The explosion apparently broke open the roof before tossing him out into the harbor. He was knocked unconscious while flying, woke up when he hit the water and swam to a Spanish boat. Once rescued, he found that his left hip and shoulder had been dislocated the whole time. Other crewmen were rescued by boats from City of Washington. Master at Arms John B. Load was near the armory when the ship exploded. He helped three marines onto a “Ward Line boat” before throwing two men injured off of the burning ship. One of the two fell too far from the boat to be rescued, but Seaman Andrew V. Erikson was picked up. Load himself was about to leap overboard, when he slipped and fell off the ship. He was rescued by a Spanish boat.

The survivors of the disaster were taken on board City of Washington and Alfonso XII. Spanish officials at Havana showed every attention to the survivors of the disaster and great respect for those killed. Chaplain Chidwick went ashore to see what had happened to the men taken to local hospitals, and found “everyone around me very sympathetic and helpful.” Sigsbee and many of his surviving officers and men found shelter on board City of Washington, captained by Frank Stevens. Maine still burned when Captain Sigsbee telegraphed Secretary of the Navy John D. Long to report “Maine blown up in Havana harbor at nine forty to night and destroyed. Many wounded and doubtless more Killed or drowned Wounded and others on board Spanish man of war and Ward Line Steamer.” Sigsbee went on to ask that “Public Opinion should be suspended until further report.” Sigsbee also telegraphed his wife, Eliza, and reported: “Maine blown up last night totally wrecked all officers Saved but Jenkins and Merritt who were probably Killed about 250 Killed I am uninjured but have lost absolutely Everything but thin Sack Coat trousers and shirt will borrow money of General Lee estimate My pecuniary loss fifteen hundred dollars.” Around this time, Brigadier General Enrique Solado, chief of staff for Spanish forces in Cuba, visited Sigsbee to express his and General Blanco’s condolences and to see what they could do to help. Consul General Lee also spent the night on board City of Washington along with Sigsbee. Sigsbee went to bed around 2:00 a.m., but could not sleep “because it was hot, and my bunk was hard. Then, too, the cries and groans of the wounded were incessant just outside my door.”

Sigsbee’s telegram went first to Key West, where Commander James A. Forsyth was station commander. He forwarded the telegram to Washington, D.C., but also sent a copy via Ericsson (Torpedo Boat No. 2) to the Dry Tortugas, where Admiral Sicard and the Atlantic Squadron were waiting. At 3:00 a.m., Forsyth dispatched the light house tender Mangrove to Havana, carrying Assistant Surgeon Spear of New York and an army surgeon, Captain Olendenin along with other medical personnel. The gunboat Fern left for Havana at 5:15 a.m. on 16 February to bring aid, while Forsyth prepared Key West to receive Maine’s injured survivors. Writing to Secretary Long, Forsyth was impressed by the “leading citizens of this place” who seemed “most earnest in a desire to do anything to help me.”

Maine’s explosion resounded around the world. The so-called yellow press had been advocating for U.S. intervention in Cuba for years, and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal hurried to take advantage of the sensational news. On 16 February, the Journal’s front page headline declared “Crisis is at Hand, Cabinet in Session; Growing belief in Spanish Treachery.” The next day, the World’s headline read “Maine Explosion Caused by Bomb or Torpedo?” Many papers called for war with Spain as early as the morning of 16 February in retaliation for Maine. Over the next weeks and months, pro-war Americans would rally around calls to “Remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain.”

Spanish officials gave as much support to the wounded of Maine as they could. Cluverius wrote later that sailors were taken to local hospitals where “everything possible was done for them. Some lingered a few days in great suffering, many died the next morning.” According to Maine’s Surgeon Lucien G. Heneberger, 29 wounded crewmen were sent to the San Ambrosia Hospital and another six to the Alphonso Treize.

Clara Barton and the available Red Cross people joined in the effort to care for Maine’s crew. The night of the explosion, she wrote later, “we proceeded to the Spanish hospital San Ambrosia, to find thirty to forty wounded—bruised, cut, burned; they had been crushed by timbers, cut by iron, scorched by fire, and blown sometimes high in the air, sometimes driven down through the red hot furnace room and out into the water, senseless, to be picked up by some boat and gotten ashore. Their wounds are all over them—heads and faces terribly cut, internal wounds, arms, legs, feet and hands burned to the live flesh. The hair and beards are singed, showing that the burns were from fire and not steam; besides further evidence shows that the burns are where the parts were uncovered. If burned by steam, the clothing would have held the steam and burned all the deeper. As it is, it protected from the heat and the fire and saved their limbs, whilst the faces, hands, and arms are terribly burned.” Most of the sailors recognized Barton and were relieved to see her. As Barton described in her book The Red Cross in Peace and War: “I thought to take the names as I passed among them, and drawing near to the first in the long line, I asked his name. He gave it with his address; then peering out from among the bandages and cotton about his breast and face, he looked earnestly at me and asked: ‘Isn’t this Miss Barton?‘ ‘Yes.’ ‘I thought it must be. I knew you were here, and thought you would come to us. I am so thankful for us all.’

“I asked if he wanted anything. ‘Yes. There is a lady to whom I was to be married. The time is up. She will be frantic if she hears of this accident and nothing more. Could you telegraph her?’ ‘Certainly!’ The dispatch went at once: ‘Wounded, but saved.’ Alas, it was only for a little while; two days later, and it was all over. “I passed on from one to another, till twelve had been spoken to and the names taken. There were only two of the number who did not recognize me. Their expressions of grateful thanks, spoken under such conditions, were too much. I passed the pencil to another hand and stepped aside.”

The night of the explosion, Wainwright conducted a muster on board City of Washington and Alphonso XII while Chaplain Chidwick visited hospitals in Havana. What they found was grim: 355 men were assigned to Maine when she exploded. 102 survived the initial explosion, but seven enlisted survivors died of burns and compound fractures injuries in the following days. One officer, Lieutenant Blow, died of shock later, leaving only 94 survivors. Only two officers, Lieutenant Jenkins and Assistant Engineer Merritt, died in the initial explosion, due to its concentration in the forward part of the ship. The Surgeon General of the Navy reported later, that “of the 77 rescued sailors and marines, only 16 were uninjured.” Maine’s injured suffered from burns (34%), concussions (30%), “wounds” (26%), dislocations (6%), and fractures (4%). Five men would be invalided from the Navy due to back sprains, “chronic pleurisy,” “deformity of nasal bones,” injuries to a hand, and paralysis. Of the 253 killed in the explosion or by drowning, only 178 bodies were recovered in 1898, with the rest of the bodies lost in the harbor or entombed in the wreck of the ship.

At Sigsbee’s request, Mangrove and Fern came to Havana on the 16th and assisted in care for the dead and wounded. Lieutenant Commander Wainwright assumed command of Fern and stayed on board for seven weeks, providing testimony for the team investigating the explosion, and directing the search for bodies among the wreckage. The same day, the U.S. passenger steamer Olivette arrived in Havana. Sigsbee sent “every officer and man that could be spared or who could travel” to Key West where they were cared for in the Marine Hospital and the Army Hospital, and also quarantined for possible yellow fever. Wainwright, Paymaster Ray, Dr. Heneberger, Chaplain Chidwick, Lieutenant Holman, Naval Cadets Holden and Cluverius, Private Anthony, and Gunner’s Mate Second Class Charles H. Bullock remained in Havana, along with the seriously wounded. Since City of Washington and Olivette left Havana on the 16th, Maine’s wounded were moved to the San Ambrosia Hospital and Sigsbee’s officers moved to the Hotel Inglaterra along with Consul General Lee, except for Wainwright, who preferred to stay on board Fern.

Sigsbee and his assistants had much to do to manage the wreckage, salvage what they could, care for survivors, and bury the dead. They did the latter with the assistance of Spanish authorities. On 17 February 1898, 19 bodies from Maine were buried. They were taken to the Havana Municipal Palace to lie in state and were showered with, according to Sigsbee, “mourning emblems of various kinds and from all classes of people … no greater demonstration of sympathy could have been made.” At 3:00 p.m., Maine’s officers still in Havana joined in a funeral procession to the Cristobal Colon Cemetery, flanked by sailors from Alfonso XII and municipal and military authorities. Thousands of residents also joined in or lined the streets. Much to Sigsbee’s annoyance, the Bishop of Havana insisted on a Catholic service for the funeral. Sigsbee brought along a Protestant prayer book and read out the Episcopal service privately during the procession. Chaplain Chidwick performed the graveside service and the first sailors of Maine were interred at 5:00 p.m. Caring for the dead was a major concern as bodies rapidly deteriorated in the tropical heat and water. Spanish authorities worked hard to assist. Forty sailors were buried on 18 February in Havana, as the local bishop, General Parrado, mayor, and other Cuban officials paid their respects. That same day, Lee reported that other sailors were “coming to surface…but now difficult to recognize.” By the 21st, local authorities had buried 143 in total.

Sigsbee visited the San Ambrosia Hospital on 20 February 1898 and wrote later that the “treatment of our wounded by the Spaniards was most considerate and humane. They did all that they habitually did for their own people, and even more.” He saw, among others, Apprentice First Class George A. Koebler, a “young and excellent” man. Sigsbee later wrote, “Koebler was a handsome, cheery, willing, and capable apprentice, equally a pronounced favorite forward and aft.” He had frequently received awards for good service. “He was in everything that was going on onboard the Maine, and had lately been married on Brooklyn, New York.” He was delirious when Sigsbee got there, insisted he could get back on the Maine and go to New Orleans for a previously scheduled port visit. “I assured him that the Maine should never leave Havana without him. It was very affecting. Poor fellow! He died on the 22d.” Consul General Lee reported that on 21 February, eleven sailors still lay in Spanish hospitals, “comfortable and well cared for.”

Secretary of the Navy Long wrote a few days after Maine’s loss that “the saddest thing of all is the constant coming of telegrams from some sailor’s humble home, or kinspeople, inquiring as to whether or not he is saved, or asking that, if dead, his body may be sent home.” Family members of Maine’s crew asked about fathers, sons, brothers, friends, and husbands. A letter from Elizabeth Denning, mother of Seaman Charles Denning is somewhat typical, as she asked for the Navy to “help a poor sobbing mother and advise me please what I have to do in case Charles died during his service.” Some family members were not sure if their relatives were even on board Maine. For example, Ordinary Seaman William Gorman’s step-father wrote to Secretary Long on 18 March. He reported that Seaman Gorman had left home in 1893. “We have not heard from him since. He told his mother that he was going to California to make a raise. He said he was going to sea and would get on a man-of-war if possible.” Unfortunately, Gorman was lost on board Maine. Fireman Second Class Patrick Flynn’s sister wrote to Long. She had “lost sight of [Pat] for several years” and asked Secretary Long if Flynn was dead. He was.

Family members writing to the Navy wanted many things. Some sought to find out if their loved one was alive. Many just wanted closure, and often asked for the body for burial. Unfortunately, the tropical climate made returning bodies impossible. Other relatives asked for help. Many of Maine’s sailors supported their wives, families, parents, or others. Other letters help to show the international nature of Maine’s crew. Franz Falk, a sailmaker master in Berlin, Germany wrote to the Navy to ask about his brother, Rudolf, who “had been in American war ships for 20 years.” Oiler Rudolf Falk’s body was never recovered, so Franz asked if his brother had left any money or anything else. Karen Anderson, widow of coal passer Holm A. Anderson, asked Secretary Long what to do. “I just got back from Norway and I am pennyles, I also have a little Baby, and I can not be doing much with him.” Inquiries came to the Navy from Sweden, Ireland, and elsewhere about Maine’s crew. The Navy was able to help in some cases, with pensions and other aid. Many relatives also received aid from private donations and funds. According to the Annual Report of the United States Navy of 1898, the service spent $85,384.19 on “relief of suffers by destruction of U.S.S. Maine” as well as another $13,965.87 for “subsistence of survivors, burial of the dead, telegrams and expenses, account of destruction of the U.S.S. Maine.”

In addition to the men killed or wounded in the explosion, the tragedy caused an immense psychological burden for the survivors. Lieutenant Blow wrote to his wife late on 16 February 1898: “Need sleep but can never lose consciousness, as my brain goes over and over events of yesterday.” The explosion deeply affected Lieutenant Blandin, the officer of the watch when the ship exploded, later writing that “the reverberations of that sullen, yet resonant roar…will haunt me from my many days, and the reflection of that pillar of flame comes to me even when I close my eyes.” The events of 15 February haunted Blandin for the rest of his life. After giving his testimony to the naval board investigating the catastrophe, he was put on light duty, but his friends and family noticed a change. As his obituary put it, “He seemed utterly unable to dismiss from his mind the horrors of the fatal night which saw the destruction of the battleship and the death of so many of his comrades, and on July 1 [1898] he broke down under the strain and was removed to the hospital.” He fell into delirium and died on 9 July 1898, another victim of the Maine. Likewise, newly promoted Sergeant Major William Anthony can be considered a victim of Maine. Made famous thanks to his stolid disposition during the explosion, he began corresponding with Adella Maude Blancet of New York State, and married her on 13 October 1898. Promoted to sergeant major, he got out of the Marine Corps, and committed suicide with a cocaine overdose in Central Park on 24 November 1899. Anthony’s suicide note read in part, “I am discouraged and disconsolate. It is better to end it all.” He was survived by his wife and son.

While the dead and wounded were rightly the first priority, Maine’s officers and crew also had to deal with the wreck of the ship itself. Wainwright and Lieutenant Holman tried to visit it early in the morning of 16 February 1898 but were warned off by a Spanish patrol boat. Wainwright complained to Captain General Blanco, who granted Maine’s crew permission to visit the wreck, where Wainwright rescued Tom, the ship’s cat. Sigsbee himself tried to visit the wreck on 18 February and was turned away because he was not wearing a uniform, but once identified, he was allowed on board. Sigsbee entrusted Wainwright primary responsibility for the wreck, and he spent the next several weeks overseeing diving and salvage operations. Wainwright was helped in the diving effort by Ensign W.V.N. Powelson of Fern, who possessed naval construction experience and had expected to be assigned to Maine, and had thus familiarized himself with the ship. While working, Wainwright refused to set foot ashore. Having lost his possessions on board Maine, for some time he had to get by with an ill-fitting suit from Havana obtained by Naval Cadet Cluverius and a pair of yellow shoes given to him by Commander William S. Cowels of the gunboat Fern.

Navy divers from the North Atlantic Squadron arrived on board the coastal survey steamer Bache on 19 February 1898. They encountered tremendous difficulty in evaluating the wreck, given relatively primitive diving technology, dark and muddy water, and the confusing nature of the wreck itself. Wainwright and the investigation and salvage operation had several objectives, one was to retrieve sensitive items from the wreck, most significantly Captain Sigsbee’s code book and keys, which divers managed to do. The Navy, contracting through the Merritt & Chapman Derrick & Wrecking Company, was even able to eventually salvage four 6-inch guns from Maine. Though rusty, they were able to be reused, one being sent to the Santa Cruz Powder Works, and the other three converted for rapid fire.

Second, divers conducted the gruesome task of recovering the bodies of sailors. Diver John Wall reported that while cutting into the wreck he “saw detached arms and legs and skulls ripped bare of hair.” Getting into the wreck, he was startled to see “the most greedy of ocean monsters – a shark! He had in his teeth a body and was swimming rapidly toward the door.” Wall hit the shark with an axe and recovered the body, but the grim task continued. Diver Charles Morgan of New York searched the wreckage in late February and early March. He wrote later that year, “It was horrible!…As I descended into the death-ship, the dead rose up to meet me. They floated toward me with outstretched arms, as if to welcome their shipmate…The dead choked the hatchways and blocked my passage from stateroom to cabin. I had to elbow my way through them, as you do in a crowd…The water swayed the bodies to and fro, and kept them constantly moving with a hideous semblance of life. Turn which way I would, I was confronted by a corpse.” In all, the Navy spent $159,378.08 via special appropriation for “recovering remains of officers and men, and property from wreck, U.S.S. Maine.”

Finally, divers attempted to discover the cause of the explosion. Relations between the U.S. and Spain had been tense for years, and many American immediately blamed Spain. The cause of Maine’s demise would be hotly debated, and closely watched by the world, for the next several weeks.

Secretary of the Navy Long wrote in his diary on 16 February 1898 that Maine’s loss was “most frightful disaster, both in itself, and with reference to the present critical condition of our relations with Spain.” Sailors, politicians, engineers, civilians, and newspapermen wondered what had caused the explosion. Long continued in his diary, “There is intense difference of opinion as to the cause of the blowing up of the Maine…My own judgement is, so far as any information has been received, that it was the result of an accident, such as every ship of war; with the tremendously high and powerful explosives which we now have, on board; is liable to suffer.” The officers and men of Maine themselves disagreed on the cause of the explosion. While Captain Sigsbee and Lieutenant Commander Wainwright both firmly believed that it was a Spanish mine, Lieutenant Blandin, officer of the watch when the ship exploded, differed. Blandin wrote to his wife the next day [16 February 1898] that “no one can tell what caused the explosion. I don’t believe the Spanish had anything to do with it. Don’t publish this letter.”

As news of Maine’s destruction spread, so did questions about its destruction. Theories ran from the grounded to the fantastical, but the fundamental questions were if the explosion started inside or outside of the ship, and if it was intentional or not. If intentional, possible culprits included the Spanish government, Spanish dissidents, Cuban insurrectionists, U.S. newspapermen, or Maine’s own crew. Before exploring the theories and immediate reaction, let us consider the best available technical analysis of the explosion.

In 1974, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover became interested in Maine and put together a historical and technical investigation of the explosion. Rickover’s study included a historical overview of the ship and its loss, context on legal issues around the Maine, a description of a similar explosion on the French pre-dreadnought battleship Iéna (1907), and a technical analysis of the wreck. The analysis, by Ib S. Hansen of the David W. Taylor Naval Ship Research and Development Center and Robert S. Price of the Naval Surface Weapons Center, examined photographs and diagrams taken of Maine in 1911 while the ship was raised for disposal. Hansen and Price found that there was no physical evidence of an explosion outside of the ship – no damage, scoring, or buckling to the outer hull. Any external explosion would have left some mark. A few anomalous portions of the wreck – a bent keel, a plate bent inward, etc. – can easily be explained by water dynamics, especially with the benefit of decades of experience examining underwater explosions. The wreck thus clearly indicates an interior explosion, which could have come from a variety of sources inside the ship. Hansen and Price argued that the most likely cause of an internal explosion was an undetected coal fire in bunker A-16 setting off the 6-inch shells in an adjacent reserve magazine. The magazine explosion then destroyed the ship. The Navy itself warned of coal fires in an investigation published a few weeks before Maine’s loss. “There are some bunkers in which fire would involve great danger, namely those adjacent to magazines… On the New York and … Cincinnati there were fires in bunkers next to the magazines which caused the charring of woodwork in the latter, and if they had not, fortunately, been discovered in time, there might have been in each case a terrible disaster.” Rickover’s study remains by far the most likely explanation for the disaster, an explanation that conforms to available evidence and does not have to resort to conspiracy theories and convoluted plots. This has not stopped a flood of other explanations, some of which have been expounded by the Navy itself, particularly in the days before modern technological analysis was possible.

Given the state of U.S.-Spanish relations and the ongoing insurrection in Cuba, it is unsurprising that many Americans immediately accused Spain of using a mine or torpedo against Maine. Captain William Sherman Vanaman was somewhat typical of this attitude. His ship, the schooner Philadelphia, lay in Havana harbor on the night of 15 February 1898 and he wrote his family a few days later blaming the explosion on a Spanish torpedo. “That is what everyone believes did it.” He went on “if the U.S. doesn’t fight over this, the whole country ought to be blown up.” Newspapers at the time blamed Spain and even published fanciful illustrations of Spanish divers placing a mine or torpedo. Despite public fervency, many disagreed with the Spanish mine theory. Some of the alternative explanations were nonsense, like Reverend Luke McKabe’s published theory that the ship didn’t actually explode, but instead was torn apart due to an insufficiently strong keel. Others were more plausible, like a jostled torpedo on board Maine, but do not conform to available evidence. More importantly, many engineering experts disagreed.

The Washington Evening Star surveyed naval officers in the days following the explosion. Most blamed an accident, some credited a mine, and a few thought it was sabotage. Others pointed to potential problems with the ship’s boilers or magazines, perennial sources of danger in the New Steel Navy, but the main explanation for an internal explosion has long been a coal fire. The Navy was well aware that placing coal bunkers in proximity to ammunition magazines was a serious design flaw.

United States Naval Academy Professor Philip Rounseville Alger pointed out on 18 February 1898 that a coal fire was far more likely than an external detonation. “We know no torpedo such as is known to modern warfare can of itself cause an explosion of the character of that on board the Maine. We know of no instances where the explosion of a torpedo or mine under a ship’s bottom has exploded the magazine within. It has simply torn a great hole in the side or bottom, through which water entered, and in consequence of which the ship sank. Magazine explosions, on the contrary, produce effects exactly similar to the effects of the explosion on board the Maine.” He theorized that a coal fire could have caused the magazine to explode. This was not a popular opinion for some. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt thought that Alger took the Spanish side and insulted the crew of Maine by implying “that the explosion was probably due to some fault of the Navy.” Roosevelt was also concerned that mechanical failings of Maine would discredit naval construction.

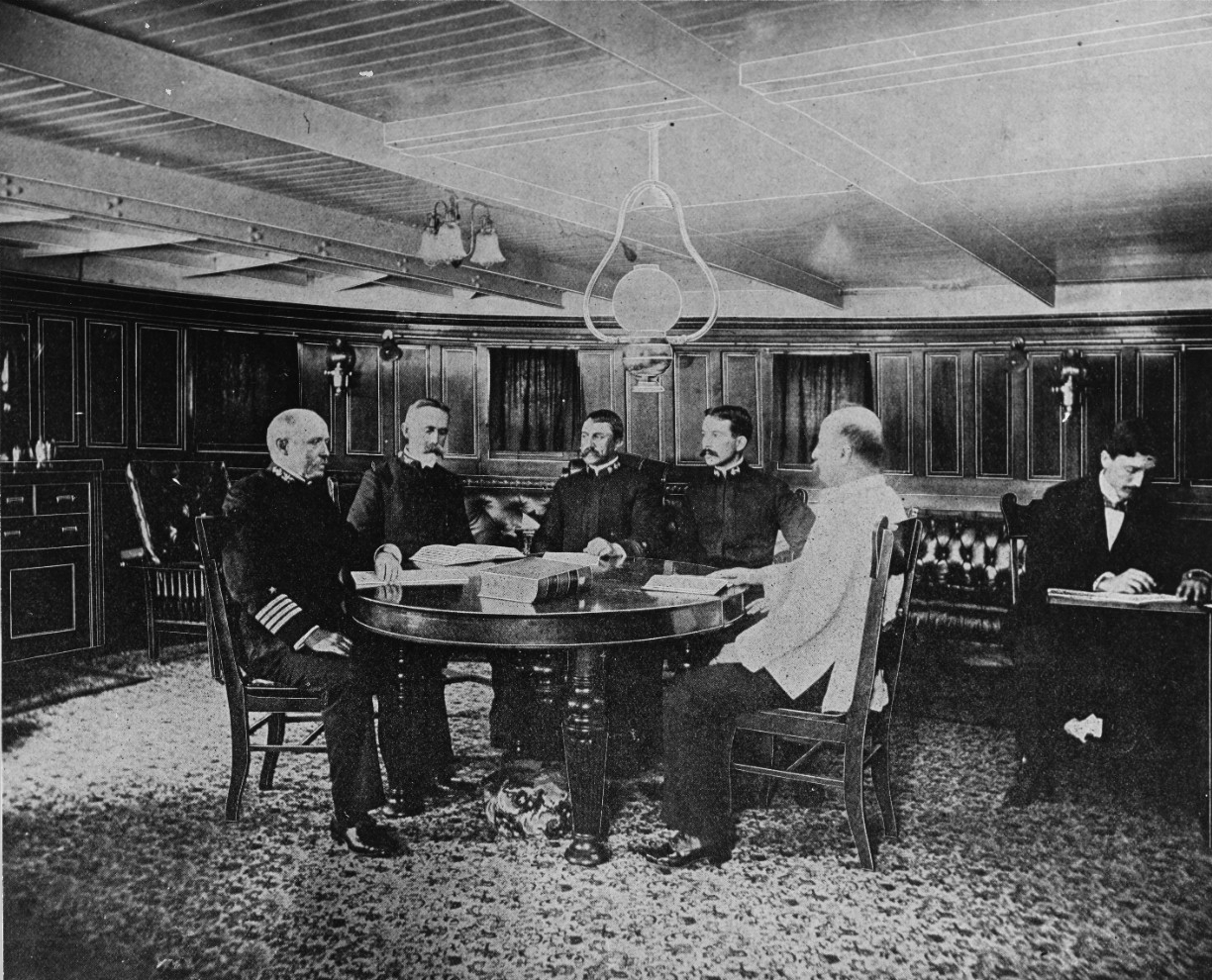

The Navy launched an investigation of the Maine a few days after the explosion. The members of the board were picked with care. Captain William T. Sampson, commanding officer of Iowa (Battleship No. 4) presided. Sampson had previously served as chief of the Bureau of Ordinance as well as the naval torpedo station and was seen as an expert in explosives. Sampson was assisted by Captain French E. Chadwick and Lieutenant Commander William E. Potter, both of the armored cruiser New York. Chadwick had headed the Bureau of Equipment and was an expert in coal and electricity. Potter was a general technical expert. Lieutenant Commander Adolph Marix joined the board as the judge advocate. He had served as Maine’s executive officer and brought valuable personal knowledge of her layout and construction. Before Sampson got to work, Spain proposed a joint investigation of the wreck. Washington rejected the request on 19 February, but promised to give assistance as the Spanish investigated the site.

The Sampson Board arrived in Havana on 21 February 1898 on board the light house tender Mangrove. Ordered by Rear Admiral Sicard to “report whether or not the loss of the U.S.S. Maine was in any respect due to fault or negligence on the party of any officers or crew of said vessel, etc.” The board got right to work. Sampson relied mostly on testimony from the officers and men of Maine, as well as diver reports interpreted by Lieutenant Commander Wainwright and Ensign Powelson. From 21 February to 21 March, the Board collected testimony, examined evidence and debated their conclusion. Captain Sigsbee served as the first witness, and sat in on all additional testimony and meetings, which surely influenced the course of the investigation. He had an obvious incentive to blame the Spanish, and not his own mistakes, if any. Sigsbee testified that the fire alarms worked, that inflammable material was stored according to regulations, and that the ship had special precautions against sabotage. His testimony usually revolved around him giving orders, rather than being sure that they were executed. He was not a trained engineer and may not have fully understood the complexities of his advanced new ship. Sigsbee’s testimony was central to the investigation, and argued by implication that Spain had destroyed Maine. As a result, Lieutenant Ramon de Carranza of the Spanish Royal Navy, and Naval Attaché in Washington, actually challenged Sigsbee (and Consul General Lee) to a duel on 25 April for slandering the honor of the Spanish Navy. Nothing came of the challenge as de Carranza was recalled from his post due to the start of the Spanish-American War.

After discussing the buoy to which Maine had been moored, Sampson pushed on to investigate the possibility of an internal explosion. Divers found the keys to the magazines, indicating that the ship’s ammunition had been securely stored and not accessed on the night of the explosion, largely eliminating the possibility of a magazine accident. Moving on to a possible coal fire, Sigsbee told the board that Maine’s temperature sensors were operational, and Chief Engineer Howell explained coal storage on board the ship. A few days later, Assistant Engineer John R. Morris testified that he had checked all of the coal bunkers on the morning of 15 February, including bunker A-16 at round 10:30 a.m., and did not see or feel anything unusual. No witness discussed blind spots within the temperature sensor system or the relatively long time between Morris’s check and the explosion. The electrical plant and boilers were also discussed, but dismissed as potential causes.