Birmingham I (Scout Cruiser No. 2)

1908–1930

The first U.S. Navy ship named for a city in Alabama.

I

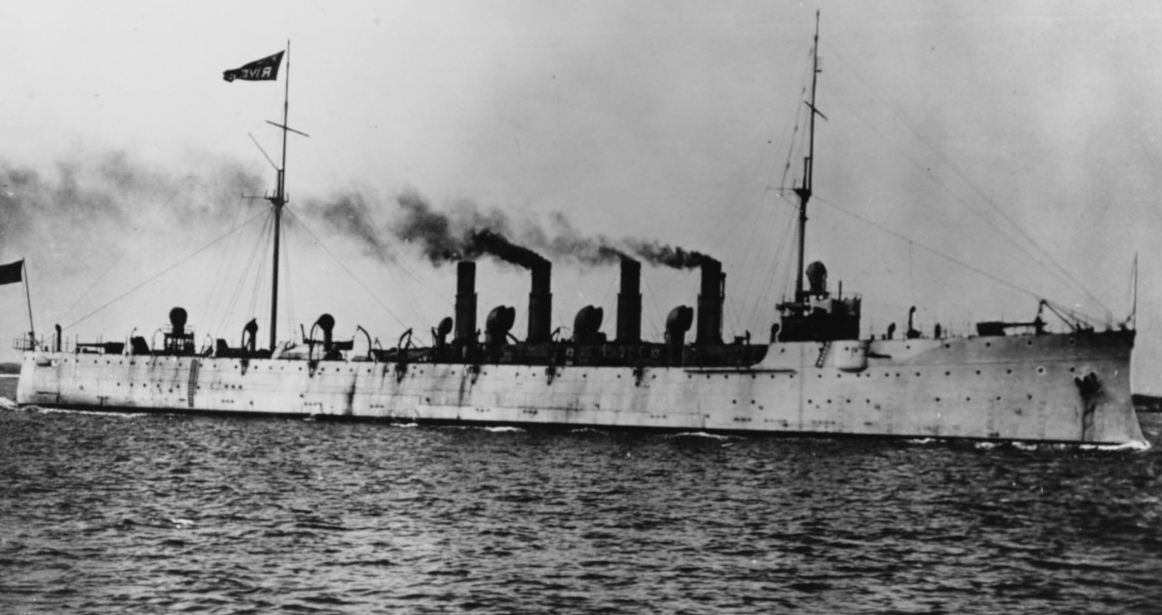

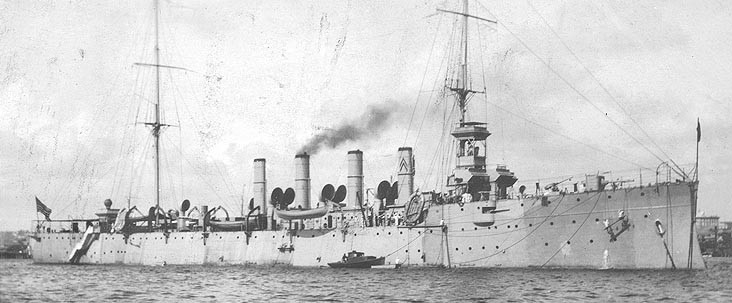

(Scout Cruiser No. 2: displacement 3,750; length 423'1"; beam 47'1"; draft 16'9"; speed 24 knots; complement 356; armament 2 5-inch, 6 3-inch, 2 3 pounders, 2 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Chester)

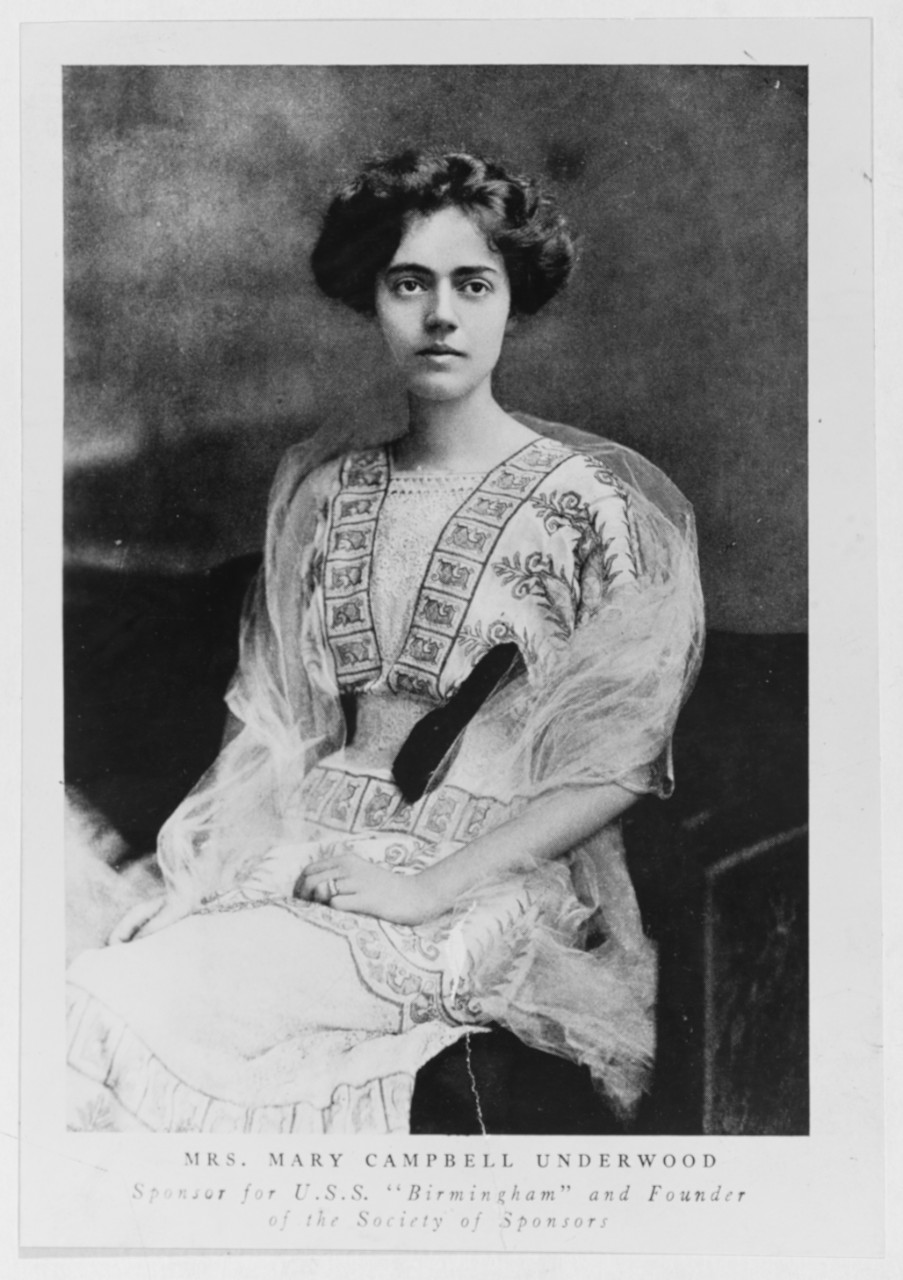

The first Birmingham (Scout Cruiser No. 2) was laid down on 14 August 1905 at Quincy, Mass., by the Fore River Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 29 May 1907; and sponsored by Mrs. Mary C. Underwood, wife of John L. Underwood, son of Sen. Oscar W. Underwood of Alabama.

Commissioned at Boston Navy Yard, Mass., on 11 April 1908, Cmdr. Burns T. Walling in command, Birmingham – assigned to the Atlantic Fleet – completed additional trials and shakedown training in New England waters. The ship accomplished alterations at Boston through the beginning of October 1908, carried out her acceptance trials off Newport, R.I. (3–8 October), and then underwent repairs to boiler issues identified during her trials, while at Boston Navy Yard (9 October–6 December), following which she tested the boilers while still at the yard. Birmingham rounded out her busy first year of service by conducting standardization trials off Provincetown, Mass. (12–13 December), and water consumption tests off Rockland, Maine (13–15 December), Provincetown (15–16 December), Newport (16–22 December), and Tompkinsville, N.Y. (23 December 1908–3 January 1909).

Birmingham then began cruising along the eastern seaboard of the United States. The new warship coaled at Bradford, R.I. (4–5 January 1909), and next (5–14 January) embarked a naval board at Newport that inspected the ship while she carried out water consumption tests off New London, Conn. The ship steamed to Tompkinsville and then (29 January–2 February) set out from that port for Mobile, Ala., where the increasingly seasoned cruiser received a silver service in honor of that state and her namesake.

After coaling at Key West, Fla. (4–8 February 1909), Birmingham lay off South Pass, La. (9–11 February) while she awaited President-elect Howard H. Taft, and then proceeded up the Mississippi River and received the future chief executive at New Orleans on the 11th. Birmingham transported the president-elect to Hampton Roads, Va. (11–14 February), and then through the 26th took part as President Roosevelt reviewed the return of the “Great White Fleet” following its circumnavigation (16 December 1907–22 February 1909). Birmingham coaled at her familiar port of Bradford (27 February–4 March), completed repairs in dry dock at Portsmouth Navy Yard, N.H. (6–16 March), and then (17 March–12 April) carried out a series of coal endurance tests, including one in company with Chester (Scout Cruiser No. 1) and Salem (Scout Cruiser No. 3) at 20 knots, and another where all three cruisers increased to full power, all off Bradford. The ship required additional work following the tests and before her next voyage and underwent repairs at New York Navy Yard (13–23 April).

The Navy, meanwhile, selected Birmingham to sail to West African waters as ongoing fractional strife among the Liberians rent that country. Secretary of State Elihu Root wrote President Theodore Roosevelt on 18 January 1909, and explained that “the condition of Liberia is really serious.” Root estimated that 40,000–50,000 “civilized” Liberians, “for the most part descendants of the original colonists from the United States,” occupied an area comprising 43,000 square miles, in which more than a million and a half “members of uncivilized native tribes” also lived. The two disparate groups of people repeatedly clashed, and one such conflict led to a tribal revolt by the Grebo people. The British colonists in Sierra Leone to the north and their French counterparts closing in from the east complained about the Liberians’ failure to maintain order along the border, and the Europeans sought to exploit the situation by seizing Liberian territory. On 11 June 1908, the Liberian mission to the United States had requested that the U.S. “invite the government of Great Britain to join with it in an arrangement looking to the perpetuity of Liberia.” A flurry of diplomatic activity between the four countries attempted to address European encroachment on Liberian territory, and to make a joint declaration guaranteeing that nation’s independence.

The U.S. appointed a commission to investigate the crisis, which set out on board Birmingham from Tompkinsville on 23 April 1909. The ship rendezvoused with Chester and Salem, and the three cruisers crossed the Atlantic, coaled and provisioned at Porto Grande Bay at São Vicente in the Cape Verde Islands (1–9 May), and reached Monrovia, Liberia, on the 13th. The commissioners lodged on board the trio of cruisers while they worked with Liberian representatives at Monrovia (13–29 May and 5 June), Grand Bassa (29–31 May), Cape Palmas (1–4 June), and Robertsport -- also on 5 June -- and wrapped-up their investigation with a visit to Freetown, Sierra Leone (7–8 June). The ships coaled and completed upkeep at Las Palmas in the Cape Verde Islands (13–16 June) and at Funchal, Madeira (17–23 June), and returned to Newport. The commissioners subsequently presented a message to Congress, and Root recommended that the U.S. consider lending military officers to assist the Liberians.

Birmingham meanwhile coaled at Bradford (2–4 July 1909), and then celebrated Independence Day at Newport. The ship completed repairs at Boston (6 July–1 September), calibrated her guns off Provincetown through the 5th, and then (6–20 September) shot at targets at the Southern Drill Grounds, beginning and ending her target practice at Hampton Roads. The scout cruiser visited North [Hudson] River, N.Y., for the Hudson-Fulton Celebration, the commemoration of the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s discovery of the Hudson River, and the 100th anniversary of the first successful commercial application of a paddle steamer, by Robert Fulton Jr. (21 September–5 October). During Birmingham’s brief northern sojourn she lay at several New York ports including Newburgh (1–2 October) and Poughkeepsie (2–5 October), and on the 5th received a draft of men and unloaded Chester’s practice ammunition at Tompkinsville. Following the celebration, Birmingham lay off Provincetown while the ship tested her wireless with Brant Rock Station in that commonwealth (7–14 December). Three days before Christmas 1909, British tug Bulldog broke down off Hampton Roads but Birmingham rescued her crew.

Foul winter weather continued to plague the region and tore into steamship Kentucky as she rounded Cape Hatteras, N.C., on 4 February 1910. On 23 January the 996-ton and 203-foot long wooden ship set out on her maiden voyage from New York for Seattle, Wash., to carry passengers between Seattle and Alaskan ports for the Alaska-Pacific Steamship Company. The vessel began leaking badly when she reached the area about 150 miles off Sandy Hook, N.J., but the crew vigorously manned the pumps and kept her afloat long enough to arrive safely at Newport News, Va. The repairs appeared to ensure the ship’s continued safe operation, Lloyd’s of London issued a certificate to that effect, and the U.S. inspector at Newport News declared Kentucky “sound and seaworthy,” and she resumed the cruise on the 2nd.

Heavy seas mercilessly lashed the ship as she attempted to pass the cape, an area notorious for fierce weather, however, and Capt. Moore ordered W.D. McGinnis, the wireless operator, to send an S.O.S., quickly followed by the chilling message: “We are sinking. Our latitude is 32°10ˈ; longitude 76°30ˈ.” The operator at the United Wireless Company station at Cape Hatteras received the message at 11:30 a.m., and almost simultaneously, the operator on board steamer Alamo of the Mallory Line Steamship Co., Capt. McIntosh and bound from New York to Galveston, Texas, overheard the distress call, and Alamo made speed to reach the area.

The Navy station at Washington meanwhile flashed wireless messages across the eastern seaboard, and dispatched Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), Birmingham, revenue cutter Yamacraw, and another revenue cutter to render assistance, but at 5:00 learned that Alamo rendezvoused with Kentucky near 32°46ˈN, 76°42ˈW. Alamo’s funnels belched thick, black smoke to encourage the crew of the distressed ship as she closed and rescued Moore, Chief Engineer Grant, McGinnis, E. Palaskette of Seattle, the company’s superintendent engineer, and all 43 of the other crewmen. McGinnis bravely stayed at his station and coordinated the rescue until the rising water drowned out the dynamo that powered his wireless set. The flooding water reached Kentucky’s fireroom by the time that Alamo pulled the last man off the foundering ship, and she disappeared beneath the waves later that night.

Birmingham consequently returned to Norfolk Navy Yard for repairs (5–19 February). The ship towed targets off Sewell’s Point (24–25 February), and on 9 March recovered a dingy that broke free of Niña, a replica of one of Christopher Columbus’ ships, off Metomkin Inlet, Va.

The U.S. continued to support the Liberians and Dr. Ernest Lyon, U.S. Minister and Consul General to Liberia and an African American minister of the Ames Methodist Episcopal Church, led a delegation that boarded Birmingham at Fortress Monroe, Va., on 20 March 1910. Lyon carried a copy of the commission’s proposals as Birmingham stood out of Chesapeake Bay in company with Chester and Salem. “Liberian public,” that country’s Vice President James J. Dossen wrote President Taft concerning Lyon and his mission on 21 March, “boundlessly grateful for the magnanimous help of your great and good nation.” The ships visited Porto Grande Bay (28–31 March), and provided accommodations and communications for Lyon and his staff while they presented the commission’s findings to the Liberians (4–12 April).

Birmingham also visited Cape Palmas (13 April–9 May), a visit marred by tragedy during the morning watch on 15 April when heavy surf swamped her sailing launch and drive the boat onto the beach, drowning Seaman W. A. Jones and Ordinary Seaman I. S. Benedict. Their shipmates sadly retrieved Jones’ body from the surf and brought him back on board, but last saw Benedict steadfastly attempting to help the boat and her crew and initially could not locate him amidst the pounding swells. The following afternoon the ship’s company mustered aft and Cmdr. William B. Fletcher, the commanding officer, read the funeral service over Jones. A firing party and mourners were then transported ashore, where they interred the sailor in the cemetery at Harper. Benedict’s body washed onto the south beach of Cape Palmas on the afternoon of 17 April. The Board of Inquest together with a burial party, went ashore to view the body, and then also laid him to rest at Harper. Birmingham returned to Monrovia on 10 May before coming about for Hampton Roads, where the cruisers concluded their voyage on 29 May 1910. The visit by the commissioners and the three warships demonstrated dramatically the United States’ interest in the continued existence of Liberia as an independent republic. The following year the U.S. arranged a Loan Agreement, whereby 17 African-American Army officers eventually (1911–1930) served in Liberia, where they worked as military attachés to the American Consulate in Monrovia, or organized, trained, and led the Frontier Force, that country’s constabulary. These dedicated men carried out their difficult mission with minimum support but set the conditions to stabilize the Liberian regime.

Birmingham resumed operations along the eastern seaboard with the Atlantic Fleet. The ship completed post deployment repairs in dry dock at Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pa. (31 May–29 June), and then (30 June–5 July) celebrated Independence Day at Portland, Maine. The cruiser coaled and provisioned at Boston, and (7–9 July) carried out backing tests with Salem off Provincetown, Mass., which the two ships followed by testing their wireless sets with Brant Rock Station (23–25 July). Birmingham coaled at Bradford, and then (4–8 August) held gunnery practice at the Southern Drill Grounds. The ship concluded her shooting and immediately joined the Atlantic Fleet’s Fifth Division while they visited the New York City area — Birmingham put in to North River through the end of the month. The cruiser exercised officers in ship handling while steaming off Cape Cod (31 August–1 September), completed repairs at Boston Navy Yard (2 September–7 October), and the crew then cleaned and painted the ship off Provincetown and Newport in preparation for taking part (18–19 October) in the commemoration of the anniversary of the British surrender at Yorktown, Va., on 19 October 1781. The ship drilled and adjusted her compasses in Long Island Sound, and then (31 October–4 November) test fired torpedoes on the range in Narragansett Bay.

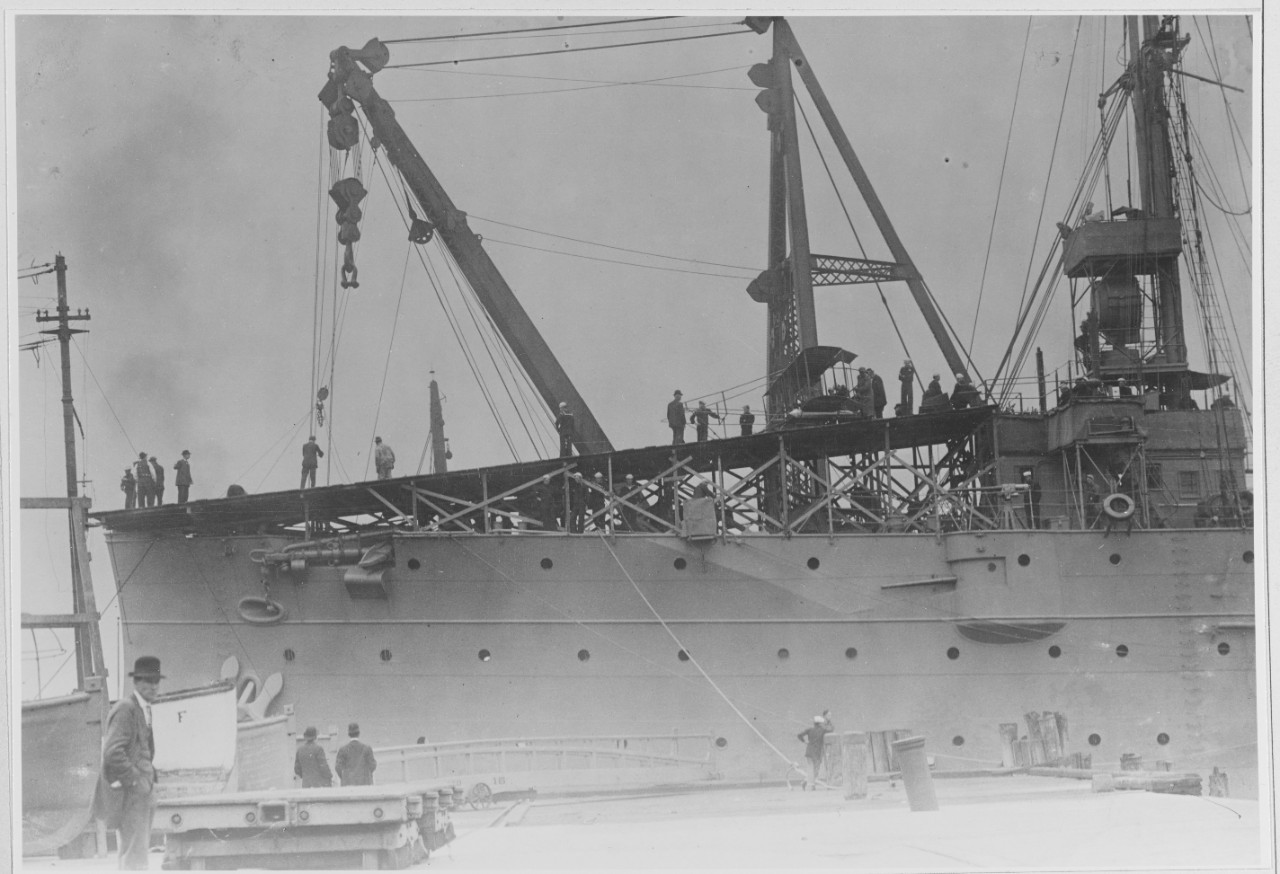

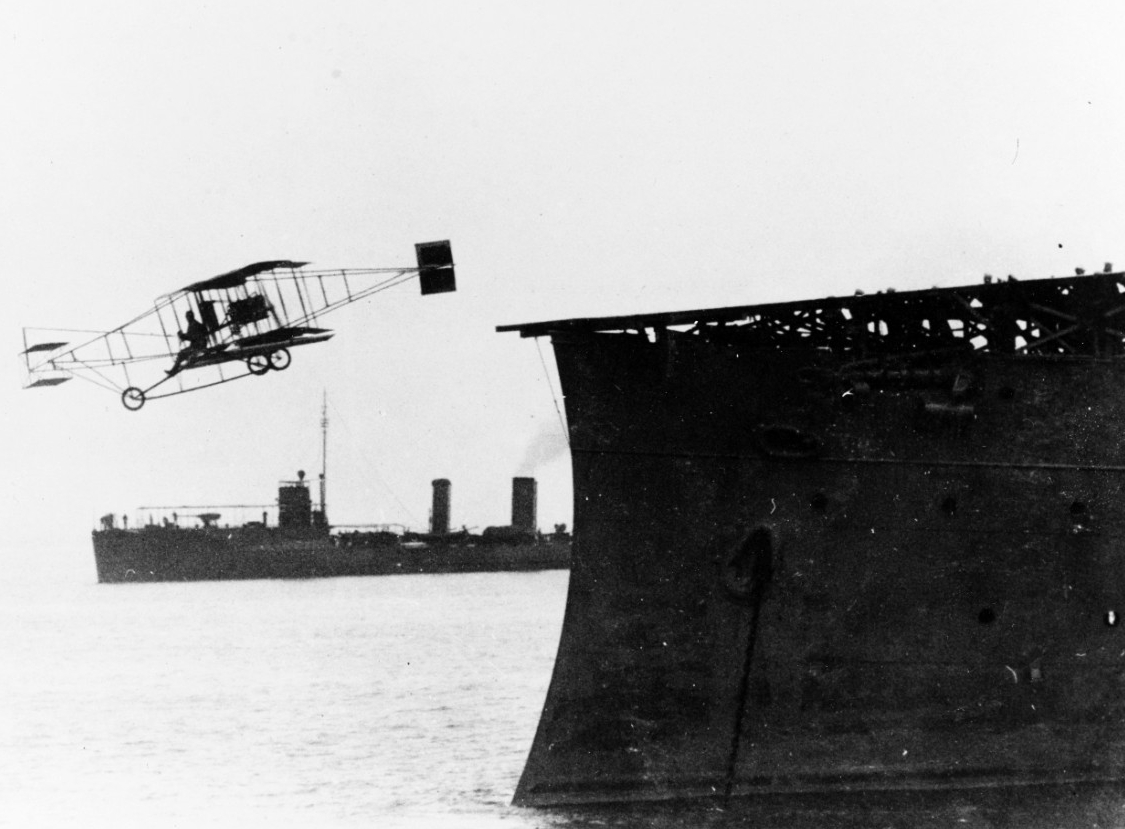

While Birmingham lay at Norfolk (8–14 November 1910), she prepared to participate in an experiment in the early history of naval aviation. Shipwrights from Norfolk Navy Yard built an 83-foot slanted wooden platform onto Birmingham’s bow and, on the overcast morning of 14 November, she embarked civilian exhibition stunt pilot Eugene B. Ely, his 50 hp. Curtiss Model D Pusher biplane, some maintainers, and a group of naval officer observers headed by Capt. Washington I. Chambers, an advocate of early naval aviation. Birmingham got underway at 11:30 a.m. and proceeded in company with Roe (Destroyer No. 24) and Terry (Destroyer No. 25), Barley (Torpedo Boat No. 21) and Stringham (Torpedo Boat No. 19), down the Elizabeth River to the Chesapeake Bay, where she anchored off Old Comfort Point at 12:35, and then shifted her anchorage and dropped the anchor again at 2:55 p.m. Rainy and drizzly weather prevented Ely from taking off several times, but the pilot gamely decided to continue and launched his plane off the cruiser’s bow at 3:17 p.m. As he left the platform the pusher settled slowly and hit the water, but rose again and landed about two and a half miles away on Willoughby Spit. The plane sustained slight splinter damage to the propeller tips but Ely’s daring feat marked the first time that an aircraft took off from a warship. Birmingham sent her motorboat to pick up Ely where he touched down at Willoughby Spit, and he, Chambers, and the rest of the party then transferred to Roe for the voyage back to Norfolk. Birmingham’s crew spent the next day tearing down the platform, raising her topmasts, and setting up the rigging, and left the lumber for Navy screw tug Alice to collect. Ely went on to land his plane on board Pennsylvania (Armored Cruiser No. 4) at anchor off Hunters Point in San Francisco Bay, at 11:01 a.m. on 18 January 1911, but on 19 October of that year died from a broken neck when he crashed while landing during an exhibition at the State Fair at Macon, Ga.

Birmingham continued operations along the Atlantic coast into 1911. She visited Savannah, Ga., for the unveiling of a statue of Gen. James E. Oglethorpe (21–25 November), and the ship’s company overhauled their warship at Norfolk Navy Yard (26 November–10 December). Birmingham trained and towed targets but the years at sea took their toll and her crew again overhauled the cruiser at Norfolk into the New Year. The ship took part in a scouting problem (training exercise) with the Fifth Division from Hampton Roads past the Virginia capes and Cape Hatteras to Caribbean waters (2–3 January 1911). Birmingham coaled at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (13–16 January), and next (17–28 January) carried out torpedo practice with her faithful consorts, Chester and Salem at Samaná Bay in Santo Domingo [the Dominican Republic].

Birmingham rejoined the fleet for battle practice off Guantánamo Bay (30 January–6 February), but detached from the exercise and raced to Watlings Island in the Bahamas to render assistance to British sailing ship Caithness-shire, when she ran ashore to the east of San Salvador Island on 4 February. Caithness-shire, a three-masted, barque-rigged ship built of steel in 1894 by Messrs. Russell & Company, was registered at Glasgow, Scotland, and owned by William Law and others. During her final voyage Caithness-shire, Master Alexander Hatfield, set out from the west coast of South America and reached Wilmington, N.C., which port she left on 25 January, ballasted with 911 tons of sand, bound for Port Arthur, Texas. Birmingham reached the scene at 9 a.m. on the 7th, and anchored outside of the reef, but could render little assistance owing to the reefs, among which Caithness-shire lay stranded. Hatfield and his 20 crewmen finally abandoned the vessel on 3 March and she became a total wreck. The British Board of Trade held a formal investigation at the County Buildings at Glasgow, and found that the ship’s loss occurred because Hatfield over-estimated the distance of the vessel from San Salvador Light at 4 a.m. on 4 February, through which the vessel was allowed to get into proximity with the foul ground to the east of San Salvador Island, where she struck a rock or reef said to have been uncharted. The Court did not find that the stranding and loss occurred by the master’s “wrongful act or default,” but blamed him for not remaining on deck after 4 a.m. as the barque passed San Salvador Island.

Following her daring rescue of the stranded mariners, Birmingham coaled and overhauled her machinery at Guantánamo Bay (9–17 February 1911), and then (21 February–1 March) took part in Mardi Gras at Mobile with Flusser (Destroyer No. 20), Lamson (Destroyer No. 18), Preston (Destroyer No. 19), and Smith (Destroyer No. 17). Birmingham coaled at Key West (3–4 March), but moved to Haitian waters in order to investigate conditions there. Rival Haitian factions vied for power, and violence ashore continually threatened that country’s stability, largely as a result of bandit bands called cacos from the mountainous north. In addition, the Germans intervened in Haitian affairs, and British and French vessels periodically patrolled Haitian waters to protect their people trapped in the chaos, so that the U.S. monitored the situation. Birmingham relieved dispatch boat Dolphin off Port-au-Prince and protected Americans during the crisis (7–22 March), and on the final day of her deployment to those waters hailed German steamer Albingla off Halle Point, to the southwest of Gonaïves Bay. Following that confrontation Birmingham headed to Guantánamo Bay to coal through the 9th — and for her crew to hold small arms target practice. The ship patrolled the Caribbean while tensions continued to flare in Haiti, and she practiced firing torpedoes off Santiago de Cuba and Golfo de Guacanayabo off the southern Cuban coast (9–10 and 11–14 April, respectively), early in May stopped at Guantánamo Bay, and visited Cristóbal at Colón in Panama (24 May–9 June). Birmingham returned to the troubled Haitian waters and on 16 June watched steamer Consul Gostrück. Commissioned in 1894 as Italian protected cruiser Umbria, the Italians sold the aging ship to the Haitian Navy and she arrived at Port-de-Paix on 11 June. The Haitians renamed and manned her Consul Gostrück, and Birmingham kept a watch on the cruiser as her new crew attempted to learn the ropes while at St. Nicholas Mole on the 16th and the capital, but the American cruiser completed that mission on 21 June and set a course for New England. The Haitians lacked experience in ship handling, however, and Consul Gostrück foundered shortly after reaching Hispaniola. Birmingham reached Boston Navy Yard on 27 June 1911, and three days later was placed in reserve.

Activated on 15 December 1911, Birmingham completed repairs there until just after Christmas, and rejoined the Fifth Division for training off Hampton Roads into the New Year (29 December 1911–3 January 1912). Birmingham returned to port and coaled and took on stores, and sailed to participate in a wargame. She was to train with McCall (Destroyer No. 28) and Paulding (Destroyer No. 22), but both ships required repairs at Hamilton, Bermuda, that delayed their participation (11–15 January), and Birmingham then escorted the pair of destroyers back to Hampton Roads for more extensive work. Birmingham turned her prow southward almost immediately on 20 January and at Key West (22–26 January) took part in the ceremony opening the Over-Sea Railroad, an engineering project financed by tycoon Henry M. Flagler, that pushed a railroad through the Florida Keys that connected Miami with Key West. The ship then steamed with the Atlantic Fleet during maneuvers and exercises off Guantánamo Bay (28 January–7 March), and returned to Key West while awaiting orders in connection with second-class armored battleship Maine.

During the friction leading up to the Spanish-American War, the U.S. had dispatched Maine to Havana, Cuba, but she exploded and sank on 15 February 1898, and the battleship’s loss became the primary catalyst that triggered the war. On 5 August 1910, Congress authorized the raising of the ship and directed U.S. Army engineers to supervise the work. Maine’s hulk was finally floated on 2 February 1912, and on 15 March Birmingham set out from Key West and reached Havana, where the bodies of the battleship’s fallen crewmen were solemnly transferred to the cruiser. The following day Maine was towed out to sea, where she was sunk in deep water in the Gulf of Mexico with appropriate ceremony and military honors. Birmingham returned the bodies to the United States at Hampton Roads on 19 March, where they were subsequently interred at the National Cemetery at Arlington, Va. The ship meanwhile coaled and carried out target practice at Lynnhaven Bay, Va. (31 March–10 April).

Birmingham again went into reserve at Philadelphia on 20 April 1912, but following the tragic loss of British liner Titanic on 15 April, the Navy decided to deploy ships to patrol the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to prevent further maritime disasters. Birmingham was consequently returned to full commission on 18 May, and the following day the scout cruiser put to sea from Philadelphia. Birmingham vigilantly roved the cold northern waters (24 May–9 June) until Chester relieved her on the 9th, and then coaled and provisioned at Halifax, Nova Scotia, through the 16th. Three days later she in turn relieved Chester, which enabled that ship to also put in to Halifax (21–28 June). The men involved in these endeavors dubbed their deployment the “ice patrol”, and informed steamers by radio of the ice conditions they encountered near the sea lanes. The service’s Hydrographic Office proudly asserted that the cruisers “thereby rendered most valuable services to shipping.” Birmingham and Chester also obtained important data regarding the visibility, drift, and behavior of ice, and took temperatures of the air and water to aid scientists in their research. Fog repeatedly confounded the ships, however, and interfered with their observations. On more than one occasion they sighted but then lost ice because of fog, which prevented them from taking accurate measurements of drift and behavior. Birmingham completed her assignment when her officers believed that icebergs would no longer drift southward into the sea lanes for that season, and came about on 8 July and on the 11th arrived back in Philadelphia. Birmingham underwent repairs at the navy yard and stood by with the reserve ships at the Delaware Breakwater (8–9 October). The ship headed north for a naval review at the North River at New York (10–15 October), in which ships passed by President Taft and Secretary of the Navy George von L. Meyer on the 14th. Birmingham joined the Atlantic Reserve Fleet at Philadelphia on 16 October 1912, and held a steaming trail at Deep Water Point on 4 March 1913, but otherwise spent an uneventful year at that navy yard.

After almost a year of inactivity, Birmingham was recommissioned at Philadelphia on 1 October 1913 and two days later, stood down the Delaware River with members of the Panama-Pacific Exposition Commission bound for Havana (7–11 October 1913). The commissioners planned the exposition as a world’s fair to mark the completion of the Panama Canal, highlight global commerce and progress, and to honor the European discovery of the Pacific Ocean -- from the New World -- by Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1513. Over the following three months the scout cruiser carried her guests to a variety of ports: Port-au-Prince (14–16 October); Guantánamo Bay (17 October); Santo Domingo (19–21 October); Cristóbal (24–28 October); La Guaira, Venezuela (31 October–3 November); Bahia and Rio De Janeiro, Brazil (14–15 and 17–23 November, respectively); Montevideo, Uruguay (26–30 November); La Plata, Argentina (30 November–5 December); Bahia again on her return voyage (11–13 December); St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies (21–22 December); and back to Philadelphia the day after Christmas 1913. The acclaimed exposition ran at San Francisco, Calif. (20 February–4 December 1915), and that city used the fair to emphasize its reconstruction following the earthquake and fire of 1906. Birmingham in the meantime remained in port outfitting as a tender and flagship of the Torpedo Flotilla. The ship shaped a course from Philadelphia for Guantánamo Bay on 2 February 1914, and six days later reached that American enclave and began her flagship duties. She remained in Cuban waters until the spring. Early in April Birmingham visited Key West and Pensacola, Fla., and the ship steamed en route from Key West to Pensacola on 9 April when a burgeoning crisis in Mexican waters cut short her training.

Revolution tore Mexico apart as disparate groups lunged vengefully at each other and one of the strongmen, Gen. Victoriano Huerta, ruthlessly eliminated rivals and ambitiously amassed power among the Federales (government troops). The chaos endangered Americans caught in the midst of the war and pushed U.S. President Woodrow Wilson beyond forbearance, and he called on U.S. warships to protect, and if necessary, evacuate Americans. Lt. Comdr. Ralph Earle anchored Dolphin in Tampico, Mexico, on 6 April 1914. Earle sent his paymaster and a boat ashore, but the Mexicans arrested the men because they landed in a “forbidden area” and paraded them through the streets. The Mexicans incarcerated an orderly from Minnesota (Battleship No. 22) when he went ashore for the mail at Vera Cruz a few days later. Rear Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Commander, Fourth Division, demanded a 21-gun salute in apology over the “Tampico Incident,” and on 14 April President Wilson ordered the Atlantic Fleet to send an expedition. The following day Wilson wired an ultimatum as the lead ships of the Atlantic Fleet arrived in Mexican waters. The Mexicans could salute the flag prior to 1800 the following day or suffer the consequences — they apologized and rendered the salute. Rumors circulated, however, that the Germans attempted to smuggle 250 machine guns, 20,000 rifles, and 15 million rounds of ammunition on board steamer Ypiranga into Vera Cruz.

Wilson therefore directed Rear Adm. Charles J. Badger, Commander, Atlantic Fleet, to seize the customhouse at Vera Cruz. On the morning of 19 April, U.S. Consul William W. Canada notified Gen. Gustavo Maas, who led the garrison at the port, of the planned landings to avoid bloodshed. Huerta disregarded the warning and ordered Maas to make a show of force to influence foreign opinion among the observers on board the ships in the outer harbor, which included British and French armored cruisers Essex and Condé, respectively, and Spanish gunboat Carlos V. The Americans landed at Vera Cruz on 21 April, and established blocking positions across the streets leading toward the Plaza de la Constitucion, the main square. The Mexicans turned several buildings into strongholds and snipers shot at the invaders from vantage points at the Benito Juarez lighthouse and Naval Academy, and from box cars and warehouses along the waterfront. Gunfire from the ships broke-up enemy troop concentrations, but the operations continued into the summer.

Birmingham lay at Pensacola during the days leading up to the landings (10–20 April 1914) and on the 20th a message flashed across the wireless: “Direct Commanding Officer aeronautic station report you for service one aeroplane section…” In less than 24 hours following the receipt of these orders the ship loaded three aircraft, hydroaeroplane AH-2 -- with spare parts for AX-1 -- and flying boats AB-4 and AB-5; together with Lt. John H. Towers in command of the First Section, an aviation detachment of three pilots; Towers, 1st Lt. Bernard L. Smith, USMC, and Ens. Godfrey de C. Chevalier, ten “mechaniciens,” a cook, and a mess attendant. Birmingham had not been fitted for hoisting aircraft, so they removed a lower boom from aeronautic training ship Mississippi (Battleship No. 23), Lt. Cmdr. Henry C. Mustin in command, and installed it on the cruiser as a derrick to load their aircraft. Rumors did not initially mention Mississippi’s deployment, so sailors transferred special lumber for repairing boat bodies and pontoons from her to Birmingham. Mustin noted that “Captain Sims [William S. Sims, Commander, Torpedo Flotilla] was very much pleased at our promptness and the completeness of the equipment I sent him.” He revealed further motives, however, in a letter to Capt. Mark L. Bristol, Officer in Charge, Office of Aeronautics: “I hope we will be able to show ourselves of some use. Are we beating the Army to it?” To protect the planes on board Birmingham during heavy weather and to make room on the overcrowded ship, they removed all of AH-2’s wings except for the engine section and all of AB-5’s wings. Men disassembled AB-4, and drew a pontoon from stores as spares for AH-2 and disassembled and packed away parts for AX-1, except for the boat body.

The section then sailed on board Birmingham to join the ships operating in Mexican waters, and their deployment inaugurated naval aviation’s first call to action. The ship crossed the Gulf of Mexico and delivered the First Section to Tampico two days later. Birmingham transferred refugees and conducted blockade operations but the fliers cooled their heels at Tampico, in contrast to their counterparts in the Second Section, who had shipped to Vera Cruz in Mississippi. Following the First Section’s arrival with one aircraft ready and another almost ready they waited patiently, only to be told that they were not needed after all and to remove the wings because they blocked the ship’s deck. The Army’s Aero Division prepared to embark at Galveston to reinforce the expedition, and planners felt that they would not need additional naval fliers. When Towers learned of this on 6 May, he sent a message to Bristol repeating the observations of Lt. John V. Babcock, an officer on Sims’ staff. Babcock had just returned from Vera Cruz and passed on Mustin’s plea for their transfer to the port to relieve the exhausted men there. The news surprised Bristol, who replied that “I wish you had given me more particulars regarding your inability to do any flying off Tampico.” With the fall of Tampico to the rebels, some officers believed that Birmingham could enter the harbor to enable the men and planes of the First Section to work inland to gain experience. In the interim, they awaited the Army’s arrival before returning to Pensacola, but Birmingham joined her aviators in keeping an eye on German warships operating in the area, and both the cruiser and the aviators stood ready to demonstrate should the Germans have intervened. Birmingham then carried the First Section to Vera Cruz, where they disembarked on 24 May, and continued the school routine of flight instruction.

The men already at Vera Cruz flew patrols over the area and had their first glimpse of organized bodies of men when they spotted two squads of a dozen and 15 men at two different points. Many of them wore bright red shirts, but the Americans also noted some Soldaderás (women soldiers). The discovery surprised the aviators, who did not know that Mexican women served as nurses and camp followers, and sometimes even took up arms alongside the men. At 9:08 a.m. on 6 May 1914, the Second Section received an urgent message: “It is reported by natives that at a point known as Punta Gorda, consisting of one large stone building near the beach, about one mile north of Vera Cruz, a company of Mexican soldiers, about 100 men, is encamped. A report is requested. By order of Col. Waller. McGill.” Lt. (j.g.) Patrick N. L. Bellinger and Lt. (j.g.) Richard C. Saufley raced over to hydroaeroplane AH-3 and rose aloft in barely five minutes. As the aviators followed the coast north toward Boca del Rio Antigua at an average altitude of 3,200 feet, they flew low over a group of Mexican stragglers, who opened fire with rifles and hit the frail craft. Bellinger immediately pulled up and he and Saufley miraculously escaped unhurt. As they returned the men stepped out of AH-3 and grimly inspected the bullet holes in the wings and fuselage, the first time that enemy rounds struck U.S. naval aircraft in battle.

Birmingham remained on station at Tampico only until May, when the Army began to relieve the Navy from occupation duty. The ship set out from Tampico on 23 May, visited Vera Cruz on the 24th and 25th, and headed back to the United States on the same day. During the crisis the Americans also seized Ypiranga, temporarily cutting off Huerta from his supplies, but the arms on board eventually reached the general. The invaders also left behind valuable stores. President Wilson shrewdly allowed the rival Constitutionalists to receive supplies, enabling them to snatch control from Huerta, who resigned on 17 July and fled into exile — though the Americans occupied Vera Cruz until November. The ship arrived at Boston Navy Yard on 2 June and began a repair period that lasted for the remainder of 1914. On 31 December 1914, the scout cruiser resumed active duty with the Atlantic Fleet.

Until the United States entered World War I on the side of the Allies on 6 April 1917, Birmingham pursued a pattern of operations with annual winter maneuvers in Cuban waters followed by spring and summer exercises off the northeastern coast of the United States. When America entered the war, Birmingham continued her east coast operations into the summer. Cmdr. Nathan C. Twining, Commander, Nantucket Detachment, Patrol Force, broke his flag in the cruiser during antisubmarine patrols in New England waters. Twining issued aggressive standing orders to the force on 20 April:

1. When a submarine is sighted by a patrol vessel the primary object is to destroy it; the safety of the patrol vessel is a secondary matter.

2. Offensive action may be taken against submarines by:

(a) Ramming,

(b) Gun-fire,

(c) Torpedo fire,

(d) Dragging with nets, bombs or grapnels.

The ships patrolled from New York and Newport, initially south of a patrol line bearing 110° from Absecon Light. Navy planners suspected that the Germans might use local fishing boats to furnish supplies to their U-boats, and Twining reported on 2 May that Birmingham “made it a rule, when patrolling, to inspect all fishing craft encountered off shore.”

The first convoy transporting the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to the fighting along the Western Front put to sea from New York on 14 June 1917. Vice Adm. Albert Gleaves, Commander, Cruiser and Transport Force, led the convoy from his flagship Seattle (Armored Cruiser No. 11), and the ships carried approximately 14,000 troops to France, consisting of 2,700 marines, primarily of the 5th Marines, and the balance soldiers, principally of the Army’s 1st Infantry Division. The troopships sailed in four groups, six hours apart, and Birmingham served as the flagship for the escort of Group 2, consisting at times of Burrows (Destroyer No. 29), Fanning (Destroyer No. 37), and Lamson (Destroyer No. 18), armed yachts Aphrodite (S. P. 135) and Corsair (S. P. 159), U.S. Army chartered transports Antilles and Momus, Henderson (Transport No. 1), and transport Lenape (Id. No. 2700), which set out from the Hoboken port of embarkation. Kanawha (Fuel Ship No. 13) and Maumee (Fuel Ship No. 14) preceded the convoy to refuel the destroyers at sea as required.

During the second dog watch on 22 June, Seattle’s helm jammed and the ship took a rank sheer to starboard, blowing her whistle to indicate the sheer. The armored cruiser swung back on course within a few minutes, and at 10:15 p.m., watchstanders on Seattle’s bridge sighted a German U-boat crossing her bow at about 50 yards. Naval officers subsequently consulted French reports in possession of the USN Attaché in Paris and determined that two submarines potentially shadowed the convoy. The enemy hunters apparently trailed the ships at a safe distance waiting for darkness, but their failure to score hits on Seattle’s convoy may have been due to Seattle’s helm jamming and her fortuitous sounding of her whistle, and that the Germans feared discovery.

As each of the four groups of ships approached the Western Approaches/Bay of Biscay, additional U.S. destroyers operating out of Queenstown, Ireland, augmented the escorts. Although the convoy reported torpedo attacks on several occasions, keyed-up imaginations may have caused most of the alerts. While Birmingham helped escort Group 2 at 11:30 a.m. on 26 June, however, the cruiser encountered an apparent enemy submarine when her watchstanders spotted the U-boat’s wake, near 47°61ˈN, 6°28ˈW. Wadsworth (Destroyer No. 60) investigated the wake without further discovery. About two hours later men on board Cummings (Destroyer No. 44), Lt. Cmdr. George P. Neal in command, spotted the bow wave of a submarine two points on the port bow about 1,500 yards away and closing. The gun pointers on her forward 4-inch gun saw the submarine’s periscope but it disappeared each time that they trained their weapon to fire. Cummings crossed in front of the wake and dropped a depth charge ahead of it, bringing considerable oil, timber, and debris to the surface. She left a buoy to mark the spot for other escorts. The officers believed that the gun crews scored a direct hit with the charge, citing increased debris in the vicinity, discolored water and air bubbling from below the surface. Officials originally speculated that the U-boat damaged by the attack was U-60, Kapitänleutnant Karlgeorg Schuster in command, but information on U-boat activity collected after the hostilities ended proved that U-60 operated elsewhere at the time of the attack. Nonetheless, the British richly awarded Cummings with a Distinguished Service Order for Neal and awards for other crewmen. Group 1 meanwhile anchored in the Loire River off St. Nazaire, France, and immediately began disembarking troops, and Birmingham and Group 2 followed suit on 27 June.

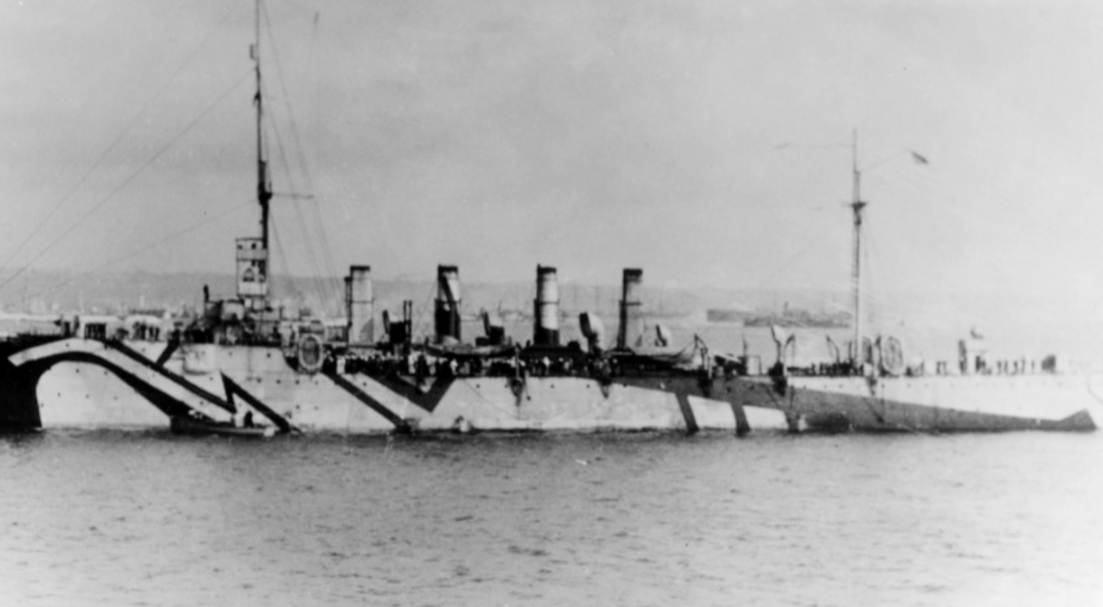

Birmingham, Allen (Destroyer No. 66) Jarvis (Destroyer No. 38), and Sampson (Destroyer No. 63) escorted Lenape and Army transports Havana and Saratoga from St. Nazaire bound for the United States on 2 July 1917. The following day Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, diverted the destroyers to Queenstown. On 6 July British First Sea Lord Adm. Sir John R. Jellicoe, RN, with Vice Adm. Sims’ concurrence, requested that Commodore Guy R. A. Gaunt, RN, British naval attaché in Washington, ask the Navy Department to deploy Castine (Gunboat No. 6), Machias (Gunboat No. 5), Marietta (Gunboat No. 15), Nashville (Gunboat No. 7), Paducah (Gunboat No. 18), Sacramento (Gunboat No. 19), Wheeling (Gunboat No. 14), and armed yacht Yankton to Gibraltar to escort convoys. Jellicoe also asked if Baltimore (Mine Planter No. 3) and San Francisco (Mine Planter No. 5) could help the British with minelaying work, most likely in the North Sea. Adm. William S. Benson, Chief of Naval Operations, thought the matter a “waste of ships,” but Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, supported sending Birmingham, Chester, Salem, Castine, Machias, Marietta, Nashville, Paducah, Sacramento, Wheeling, and Yankton overseas. Benson did not believe, however, that he could spare Baltimore and San Francisco. Sims cabled Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels on 7 July, noting the efforts of the British Grand Fleet’s destroyers and submarines to intercept U-boats north of Scotland. Sims recommended “that all coal-burning Dreadnoughts be kept in readiness for distant service in case future developments should render their juncture with Grand Fleet advisable.” The admiral also recommended that Birmingham, Chester, and Salem join the Grand Fleet’s Light Cruiser Squadron, and that the coal burning Preston (Destroyer No. 19) class destroyers be based at Queenstown rather than at the Azores. Birmingham returned to the United States later that summer. At New York, she fitted out for distant service and on 8 August stood out as the flagship of Rear Adm. Henry B. Wilson, Commander, Patrol Force. The scout cruiser arrived at Gibraltar on 17 August, and began escorting convoys between Gibraltar and primarily Devonport and Plymouth, England, with occasional calls at Brest, France, and Tangier, Morocco. During one such voyage the ship reached Plymouth on 7 January 1918, and on the 19th set out from Falmouth for Gibraltar.

The ship lay at Gibraltar on 11 November 1918 when she learned of the armistice. Birmingham immediately left the famed “Rock” and entered the Mediterranean to support the Armistice Commission. The ship called at Valletta, Malta, on 14 November, and on 3 December she brought Rear Adm. William H. G. Bullard, the U.S. Navy’s representative to an Allied naval commission formed “to decide upon and carry into execution the details of the armistice” with the Austro-Hungarians, to Spalato [Split], Croatia. The Allies selected the port as a naval base for the zone patrolled and protected by American forces under the terms of the Austro-Hungarian armistice. Birmingham continued to transport dignitaries to Italian ports and along the Dalmatian coast as they carried out the naval terms of the armistice in relation to the former Austro-Hungarian fleet. She set out across the Adriatic on 11 December for Malamocco, a port on the Lido di Venezia near that bustling city, and arrived at Fiume seven days later. Birmingham stayed at Fiume into the New Year, until she set out for home, and returned to the United States at Boston Navy Yard (17 January–18 February 1919).

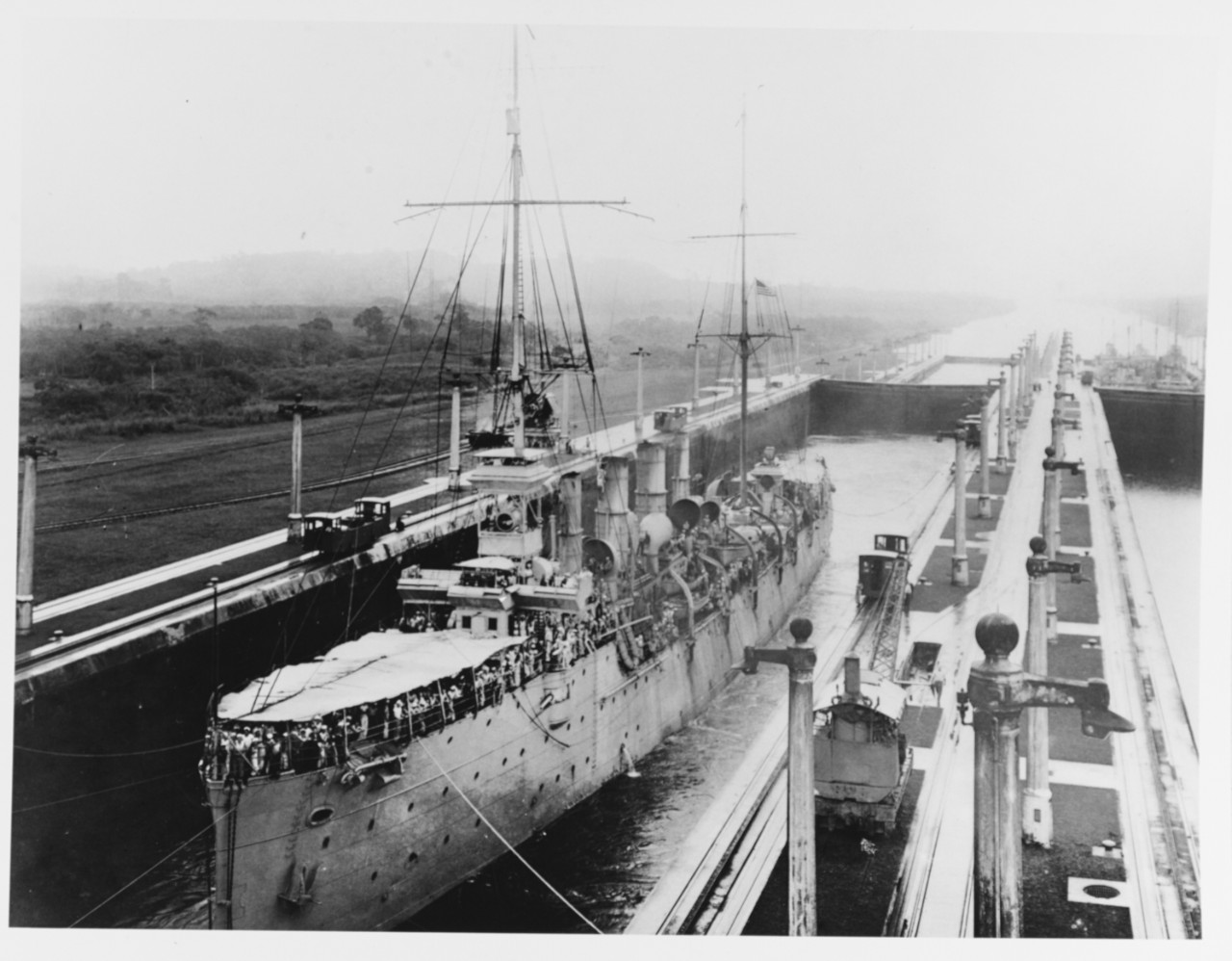

After repairs at the Boston Navy Yard, she joined the Pacific Fleet in July 1919 as flagship for Commander, Destroyer Squadrons, Pacific Fleet. From her base at San Diego, Calif., she ranged the western coasts of the United States and Mexico, engaged in torpedo drills and various tests. On 17 July 1920, when the Navy adopted the alphanumeric system of hull classification and identification, she was reclassified to a light cruiser (CL-2). Birmingham steamed with other ships of the Pacific Fleet to Chile in February 1921. In May of 1922, Birmingham became flagship for Rear Adm. William C. Cole, commander of the Special Service Squadron. Based at Balboa in the Panama Canal Zone, she and the other ships of the squadron brought American naval power to influence people in the region. The ship visited Cost Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua in May 1922. Further visits included the Netherlands West Indies, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

Birmingham rounded out the busy year by attending the American Legion 4th National Convention and the Navy Day celebrations at New Orleans, La. (7–28 October 1922). The ship shaped a course from Balboa to New Orleans (6–12 October), where, on the morning of the 12th, Cole called on officers at the 8th Naval District and ascertained what arrangements they had made for the cruiser’s participation. That afternoon he took Birmingham to Donaldsonville, La., where the South Louisiana State Fair was already in progress. The ship landed a detachment of bluejackets and marines that paraded past fairgoers, and on the 15th she shifted to New Orleans for the convention (16–20 October). Cole entertained multiple dignitaries at lunch on 18 October, and the guests included Capt. Nagano Osami, a Japanese naval attaché to the U.S., a future adversary.

Birmingham accomplished an overhaul at Boston Navy Yard through the end of January 1923, and then renewed ties with the state of her namesake when she took part in Mardi Gras at Mobile (31 January–14 February), celebrating the festival on the 8th. Following Mardi Gras the veteran cruiser set out for the Panama Canal and reached Cristóbal on the morning of 19 February. She fueled there and reached Balboa the following day, where Rear Adm. Cole immediately shifted his flag from Cleveland (CL-21) to Birmingham. The latter ship carried the admiral from Balboa on 21 February to Corinto, Nicaragua, where she arrived just after noon on the 23rd. Cole and his staff landed and boarded a train for Managua, where he inspected the U.S. Legation’s Marine Detachment, Maj. John Marston VI, USMC, in command.

While Birmingham lay at Corinto, MM1c Harry Garland of the ship’s company died from inhaling sulphate of morphine. Garland purchased the substance from Michael (Miguel) Turner, an American self-styled “international adventurer” who lived in Nicaragua, and whom Cole described as a man of “notorious and undesirable character.” Turner ran houses of prostitution and a saloon in Corinto, and was suspected of murdering the port doctor, though escaped conviction because of a lack of evidence. Turner thus eluded deportation more than once, but Garland’s death proved the last straw and the authorities evicted him and he sailed on board passenger steamer San Juan, of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, for Manzanilla, Mexico, on 4 March. The Mexicans refused Turner entry into their country, however, and he continued on to San Francisco, where, on the 27th, he caused a stir among journalists while pleading to return to the United States. Turner told federal authorities that he had been born near San Antonio, Texas, and baptized in Amarillo. He wove quite a tale for the port officials and said that he had once served as a deputy sheriff in New Mexico, where he shot and killed a man while holding that office, but was acquitted of the deed, and elaborated upon his story to include working as a cattle guard for the Department of the Interior. Turner subsequently disappeared from Navy records during “The Roaring Twenties.”

Birmingham carried out upkeep at Balboa until 1 May 1923, when she set out for a courtesy visit to Callao, Peru, where she arrived at 10:00 a.m. on the 6th. Capt. Charles G. Davy, an American officer who commanded the Peruvian Naval Academy, and Capt. Frank B. Freyer, the chief of the U.S. Naval Mission to Peru, boarded the ship and greeted Cole. Davy and Freyer’s unique posting enabled them to gain access to the organization and training of the Peruvian Navy, a move that some of that country’s officers resented, but which in the process also taught U.S. methods to the Peruvians. Their naval academy adopted a curriculum that covered much of the ground covered at the U.S. Naval Academy, and a number of USN text books were translated into Spanish for the Peruvians. The entourage then went ashore to the Peruvian Naval Academy, where they laid a wreath at a bronze bust of Vice Adm. Martin G. Guise, often considered the founder of the Peruvian Navy. United States Ambassador Miles Poindexter hosted the visitors to an informal luncheon at the American Embassy, and in the afternoon they attended races, where Cole met President Augusto B. L. y Salcedo of Peru. During the succeeding days Cole and some of his staff and the ship’s company took part in a number of events, including an expedition up the Arrolla Road to Rio Blanco, a poorly-developed mining area, and a banquet hosted by President Salcedo. The Peruvian chief executive unintentionally caused an awkward situation when he presented Cole and some of the naval officers, along with Maj. Gen. Edwin B. Babbitt, USA, an Army officer stationed in the Panama Canal Zone who sailed as a liaison, decorations including La Orden El Sol del Peru [the Order of the Sun — which the Americans reported as the “Order of El Sol”]. Cole worried about the legal issues involved in accepting the awards, and turned his over to Ambassador Poindexter and his staff.

The ship stood out of that port on 13 May and at 9:30 a.m. on the 16th called at Guayaquil, Ecuador. Cole and the officers of his staff and the cruiser exchanged the usual pleasantries with the American Consul and the local officials, and attended a banquet held in their honor the following evening. The day after the ship arrived, however, an earthquake struck near the capital of Quito. A party of about 90 men from the ship consequently took a 22-hour train ride at the behest of the Ecuadorians to Quito, where a slight after shock from the earthquake ominously announced their arrival. Cole reported that the Americans witnessed “a large assembly and procession of a religious nature” as the Ecuadorians pleaded to heaven for the earthquakes to cease. The visitors met President José L. Tamayo and a number of members of his cabinet. Cole intended to lay a wreath at that country’s Memorial to the Unknown Soldier, but unbeknownst to him the ship’s company conceived of the same idea and collected money for one. Cole thus placed his wreath at a statue dedicated to Gen. Antonio J. de Sucre y Alcalá.

Birmingham weighed anchor at 10:00 a.m. on 24 May 1923 and on the 26th entered Buenaventura, Colombia. Gov. Don José I. Vernaza led a delegation and band that traveled eight hours by train from Cali to greet the ship, a difficult journey that Cole succinctly evaluated as “extremely unpleasant,” and President Pedro N. O. Vázquez telegraphed a message of “felicitation.” The Americans made the usual round of soirées, including a dance and reception hosted by prominent Ecuadorians. Birmingham sailed at 5 p.m. on 27 May and at about 10.00 p.m. the following evening returned to Balboa. “The attitude of the people in Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador…” Cole summarized the visits, “was most cordial and friendly.” The squadron commander added that Babbitt’s “tact and co-operation materially assisted” him during his inaction with people in the three countries.

The following month Birmingham prepared to take part with Denver (CL-16) and Galveston (CL-19) in night battle practice in Panama Bay. Birmingham’s age caught up with her, however, and the ship experienced ongoing problems with her “thrusts”, which heated dangerously whenever she attempted to steam at 15 knots or greater. Cole and his staff departed the ship on 5 June 1923, and while the admiral inspected Denver at Cristóbal, he received a message that the Navy intended to deploy heavy cruiser Rochester (CA-2) to relieve Birmingham, and then the latter ship would be decommissioned because of her “engineering defects.” Cole consequently cancelled Birmingham’s participation in the battle problem and her crew concentrated upon preparing the ship to be decommissioned, which included sealing and “red-leading” 13,500 square feet of interior plating, and transferring stores from the ship ashore to the 15th Naval District.

Birmingham sailed from Balboa to Cristóbal on 28 June 1923, and then (30 June–7 July) set out on her final voyage to Philadelphia. She was decommissioned there on 1 December 1923, and remained in reserve until 21 January 1930, when she was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. Birmingham was sold to the Boston Iron & Metal Co., for scrap on 13 May 1930, and on 25 March 1931 the company reported her scrapped.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Cmdr. Burns T. Walling | 11 April 1908 |

| Cmdr. William L. Howard | 24 February 1909 |

| Lt. Cmdr. William B. Fletcher | 28 October 1909 |

| Cmdr. Hilary P. Jones Jr. | 10 May 1911 |

| Lt. Guy Whitlock | 8 September 1911 |

| Cmdr. Charles F. Hughes | 18 December 1911 |

| Lt. Guy Whitlock | 15 August 1912 |

| Lt. Myles Joyce | 4 March 1913 |

| Capt. William V. Pratt | 8 January 1914 |

| Capt. Charles L. Hussey | 5 November 1914 |

| Cmdr. David F. Sellers | 1 January 1915 |

| Capt. DeWitt Blamer | 9 June 1916 |

| Cmdr. Franck T. Evans | 28 April 1919 |

| Capt. George B. Landenberger | 22 November 1920 |

| Cmdr. Kenneth G. Castleman | 22 November 1921 |

Mark L. Evans and Paul J. Marcello

2 August 2017