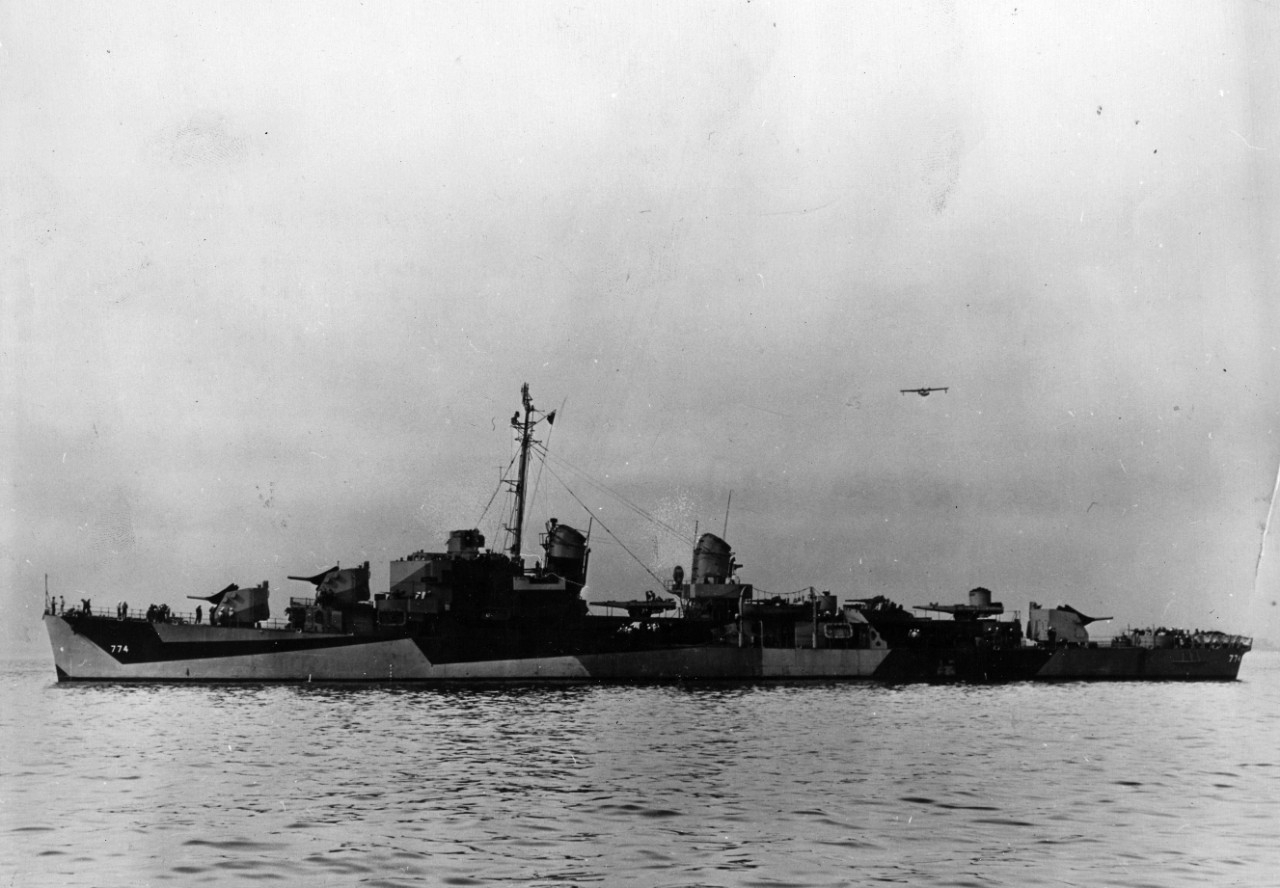

H-046-3: Kikusui No. 6 and Its Prelude—The Epic Fight of USS Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774), 11 May 1945

On 5 May 1945, the Japanese commenced the third Kaiten suicide submarine mission with the departure of the Shimbu (“God’s Warriors”) Mission, which consisted of only one submarine, I-367, configured to carry five Kaiten manned torpedoes, heading for Okinawa. I-366 hit a mine on 6 May and could not participate, returning to port for repairs.

Oberrender (DE-344) and England (DE-635) Knocked Out of the War, 9 May 1945

Japanese kamikaze attacks off Okinawa were not limited to the Kikusui mass raids. There was a near-constant threat from smaller groups of aircraft and even solo flights. On 9 May, U.S. ships conducting ASW screening operations north and northwest of Kerama Retto came under attack.

The destroyer escort Oberrender (DE-344), commanded by Lieutenant Commander Samuel Spencer, USNR, was on the outer ASW screen at dusk on 9 May. Oberrender was a veteran of the Leyte and Lingayen Gulf landings and had survived significant damage when the ammunition ship Mount Hood (AE-11) spontaneously exploded at Seeadler Harbor on 10 November 1944.

Oberrender went to general quarters at 1840, when enemy aircraft were reported in the area, subsequently sighting a single in-bound aircraft and commencing fire at 9,000 yards. Spencer maneuvered at flank speed to bring a maximum number of guns to bear, but despite hits, the plane would not go down. A near miss from a 5-inch shell-burst blew off a wing at 250 yards and deflected the aircraft, but not enough. The kamikaze crashed through the starboard forward 20-mm gun tub, killing the crew.

The plane’s bomb penetrated deep into the ship, exploding in the forward fireroom with such force that it nearly broke the ship in two, with hull plating blown out for nearly a quarter of the ship’s length. Oberrender lost all power and went dead in the water, suffering eight killed and 53 wounded. Damage control teams did great work and luckily the ship did not break apart. The rescue patrol craft PCE(R)-855 took off Oberrender’s casualties and the tug Tekesta (ATF-93) towed her into Kerama Retto. The damage was deemed not repairable and she was stripped of all useable gear, decommissioned on site, and sunk as a target just after the war.

Within minutes of Oberrender coming under attack, kamikaze went after destroyer escort England (DE-635) on ASW station B11 northwest of Kerama Retto. England was under the command of Lieutenant Commander John A. Williamson, who had been executive officer of the ship when she sank six Japanese submarines in 12 days in May 1944 (many accounts credit Williamson as the driving force in England’s ASW prowess and, by the way, he invented the “Williamson Turn” used for man-overboard recovery—see H-Gram 030). England had also almost been hit by a kamikaze on 25 April 1945.

At 1851 on 9 May, three Japanese aircraft (identified as “Vals”) made a run on England with combat air patrol in hot pursuit. The fighters downed the two trailing aircraft while England engaged the lead with guns. Despite being hit and set on fire, the kamikaze just kept coming. The plane reportedly had two pilots, with the pilot in front slumped over the controls and the pilot in back apparently flying the plane (some Vals were modified as dual-control trainers late in the war).

The Val crashed into England’s forward superstructure on the starboard side just below the bridge, and the 250-pound bomb with a delayed-action fuze penetrated into the ship and went off a few seconds later. The after-action report also stated the plane carried two “fire bombs.” The explosion and resulting raging fire demolished wardroom country, the captain’s cabin, ship’s office, and radio room. The flying bridge and signal bridge were enveloped in flames and some crewmen were forced to jump over the side (and took wounded men with them, who wouldn’t have survived otherwise). Twenty-millimeter shells also cooked off and added to the casualties. Williamson was able to jump down from the bridge, make his way aft, and conn the ship via after steering.

England’s crew kept the fires from spreading further and, at 1919, the minesweeper Vigilance (AM-324) came alongside to help put out the fires after picking up some of the overboards. Destroyer-minesweeper Gherardi (DMS-30) came alongside and put a doctor and medical team aboard England. Although England was capable of steaming under her own power, with her entire bridge area burned out and demolished and it being night, Williamson opted to be towed into Kerama Retto, with three officers and 24 enlisted men dead, ten missing, and 27 wounded (final tally of dead was 35 or 37 depending on the account). The bodies of both Japanese pilots were recovered on board and much was made of the fact they were both wearing parachutes. (However: In fact, kamikaze pilots generally flew in full regulation gear, parachute and all, even on one-way missions.)

After temporary repairs, England made her way to Philadelphia Shipyard, where she commenced repair and conversion to a fast transport, which was halted when the war ended and never completed. Although Fleet Admiral King had stated after England’s ASW exploits that “there’ll always be an England in the U.S. Navy,” this has only been true during the service of the cruiser USS England (CG-22) from 1963 to 1994.

Kikusui No. 6: The Epic Fight of Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774) and Evans (DD-552), 11 May

Kikusui No. 6 launched the morning of 11 May from Japanese airfields in Kyushu. It consisted of 150 kamikaze aircraft, including 70 from the navy and 80 from the army. Like Kikusui No. 5, it included a hodgepodge of virtually every type of aircraft in the Japanese inventory (and resulted in wildly inaccurate recognition calls by U.S. ships and aircraft). Radar Picket Position No. 1 lucked out this time. The main Japanese attack came in further west over RP15, located 40 nautical miles northwest of the Transport Area off the southwest coast of Okinawa.

At RP15, was the new Allen M. Sumner–class destroyer Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774), with a Fighter Direction Team embarked, and commanded by Commander Baron J. Mullaney. Also at RP15 was the Fletcher-class destroyer Evans (DD-552), named after the first commander of the Great White Fleet, Rear Admiral Robley “Fighting Bob” Evans (“The Fighting Bob” became the ship’s nickname). Evans was commanded by Commander Robert J. Archer. Four amphibious vessels were on station, including LMSR(R)-193 (the lessons of the loss of three LSM[R]s on 3 and 4 May having not yet taken hold). Three large support landing craft, LCS(L)-83, 83 and 84, were also at RP15.

At dusk on 10 May, the two destroyers had combined to shoot down a Japanese aircraft at 1935. Other single aircraft were detected passing by to Okinawa in the darkness and could not be engaged, but caused the crews being at general quarters for much of the night.

On the morning of 11 May, Hugh W. Hadley’s fighter direction team had control of 16 F6F Hellcats of VF-85 off the newly arrived new-construction Essex-class carrier Shangri-La (CV-38). Hadley also had control of two Marine F4U Corsairs of VMF-323 flying from airfields on Okinawa captured from the Japanese (Kadena and Yontan). The combat air patrol tactics at the Radar Picket Stations were becoming more standardized: The Navy aircraft from the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58) would be vectored to intercept incoming Japanese raids between 25 and 50 nautical miles out, while the Marine fighters would hold close to the ships at the picket station to deal with any leakers from the “outer air battle.”

About 0730, radar on Hugh W. Hadley and Evans began picking up many Japanese aircraft approaching from the north. Commander Mullaney looked at the radar picture in the combat information center (CIC) that the CIC evaluator assessed to show five major groups with an estimated total of 156 aircraft, which wasn’t far off. The Navy CAP were vectored to intercept (other TF 58 fighters would join in), resulting in the largest air-to-air action of the Okinawa campaign. Communications between Hugh W. Hadley and the CAP became increasingly challenging due to the intensity of the action, but, by 0800, it was estimated that 40–50 Japanese aircraft had been shot down by Navy fighters, but somewhere around 100 were still coming through.

The Marine fighters were vectored to intercept and, before long, they were engaged in dogfights ranging up to 10 to 20 miles from the ship; the numbers of Japanese aircraft were just overwhelming. The Marines shot down several planes and even after they ran out of ammunition continued to harass Japanese aircraft, forcing at least some of the inexperienced Japanese pilots to crash into the ocean.

USS England (DE-635): Damage from a kamikaze hit received off Okinawa on 9 May 1945. This view, taken at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 24 July 1945, shows the port side of the forward superstructure, near where the suicide plane struck. Note scoreboard painted on the bridge face, showing England''s Presidential Unit Citation pennant and symbols for the six Japanese submarines and three aircraft credited to the ship. Also note fully provisioned life raft at right (80-G-336949).

At 0740, a Japanese E13A Jake float plane (normally launched from battleships or cruisers) approached Hugh W. Hadley undetected by radar and pursued by a CAP fighter. The Jake was hit and blew up in a large explosion. Evans also reported shooting down a Jake at about the same time (0753); it is likely the same aircraft and uncertain whether Hugh W. Hadley, Evans or, CAP was responsible for its destruction.

Many more Japanese aircraft then came in view with the lead elements seemingly intent on flying past the destroyers in order to reach the transport area; Hugh W. Hadley shot down four. Subsequently, a very large number of Japanese aircraft turned their attention to the ship and to Evans and, by 0830, both were in a desperate fight against overwhelming odds, with each being attacked repeatedly by groups of 4–6 aircraft. In their frantic maneuvering, a gap of as much as two to three miles opened up between Hugh W. Hadley and Evans and the supporting amphibious ships so that mutual support became less effective. By 0900, Hugh W. Hadley had shot down 12 Japanese aircraft, many on kamikaze attack runs and some crashing close aboard in near misses. These included one dive-bomber that crashed 20 feet astern at 0835 and another Val that had its wing shot off and crashed 100 yards away. So far, Hugh W. Hadley was not seriously damaged, but urgent calls were going out on the radio for CAP to return overhead to support.

Meanwhile, Evans was putting up a terrific fight of her own, but would be less lucky. Planes attacked her from all different directions between 0830 and 0900, and she shot 15 of them down and assisted in downing four more. At 0830, three Kate torpedo bombers were sighted boring in from the port quarter and Evans shot down all three of them. Over the next 15 minutes, Evans’ gunners downed a mix of seven aircraft identified as Kates, Jills, and Zekes (Navy dive and torpedo bombers and fighters), and Tonys (Army fighter). One of the Kates got close enough to drop a torpedo before it went down. Commander Archer ordered a hard left rudder and the torpedo missed ahead of the bow by only 25 yards. Following the torpedo attack, an army Tony was shot down by both Evans and Hugh W. Hadley, crashing 3,500 yards from the former. Then, a Val dive-bomber on a suicide dive was hit and the pilot lost control, missing Evans and crashing 2,000 yards beyond. An army Ki-43 Oscar fighter dropped a bomb that missed and was shot down while attempting to crash into Evans. An army Oscar and a navy Jill torpedo bomber made a run in from the port side and both were shot down close aboard. A few minutes later, Evans shot down a Tony fighter on an attack run.

Evans’ extraordinary run of good luck (and obvious anti-aircraft skill) ran out at 0907, when a Judy dive-bomber came in from the port bow and crashed into the ship at the waterline, holing the her and causing flooding in the forward crew’s berthing compartment. Nevertheless, Evans’ guns kept firing and another Tony was knocked down at 8,000 yards by a direct hit from a 5-inch shell.

In the smoke of intense anti-aircraft shell bursts, it became increasingly hard to spot incoming aircraft and, at 0911, Evans took her second hit by a kamikaze, which crashed portside amidships in a bad hit just below the waterline that flooded the aft engine room. Then, two Oscar fighters hit Evans in quick succession. The first Oscar released a bomb in a near-vertical dive that exploded deep in the ship in the forward fireroom, destroying both forward boilers, while the crashed plane ignited gasoline fires. The second Oscar hit the ship from the starboard side, starting more fires and inflicting additional severe damage. At 0925, as Evans went dead in the water, two Corsairs chased a Japanese aircraft into range of Evans’ guns, which hit the plane, causing it to miss overhead the bridge and crash close aboard on the other side. At this point, apparently believing Evans was done for, Japanese aircraft focused on the other ships. This gave Evans’ crew a respite to save their ship, including resorting to bucket brigades and portable fire extinguishers, as pumps and fire mains were mostly out of action.

As Evans was being hit by four kamikaze in quick succession and being effectively knocked out of the battle, Hugh W. Hadley was facing a coordinated attack by ten Japanese aircraft. At 0920, four kamikaze came in from the starboard bow, four more from the port bow, and two from astern. In one of the most astonishing displays of gunnery prowess, Hugh W. Hadley’s gunners shot all ten down without taking a hit. Then, her luck ran out and she was hit by a bomb and three kamikaze in quick succession.

Accounts vary widely as to the type of aircraft and order of hits. I rely primarily on the Navy Bureau of Ships (BUSHIPS) final damage report, which differs in some significant ways from Commander Mullaney’s initial after-action report and even from Morison, particularly in regards to whether the Hugh W. Hadley was hit by an Ohka rocket-assisted manned flying bomb. According to the initial after-action report, a Betty bomber flying at low altitude (600 feet) astern launched an Ohka that hit the ship amidships. The BUSHIPS report discounts this for several reasons: the aircraft engine and bomb tailfin found in impact areas, indications that the impact came from forward of beam, and that the Ohka launch profile was usually at 20,000 feet. Moreover, a direct hit amidships by a 2,600-pound warhead probably would have sunk the ship in short order. Nevertheless, a very large explosion (with no smoke, flash, or noise other than a dull thud) occurred well under the keel at the same time as a kamikaze plane impacted the ship. The BUSHIPS report cannot conclusively identify the source of this large explosion, postulating that it might have been an “influence” torpedo, or more likely a very large bomb that passed through the ship, out the bottom, and detonated a significant distance below the keel. The damage was severe, hogging the keel by over 50 inches and flooding both engine rooms and the aft fireroom.

According to the BUSHIPS report, at 0920, a kamikaze of unconfirmed type passed through Hugh W. Hadley’s rigging, carrying away wires and antenna, and crashing close aboard to port (this is listed in accounts as a “kamikaze hit” although a “near-miss shoot down” may be more accurate). A few minutes later, a kamikaze (originally reported as a “Baka Bomb”—an Ohka) hit the starboard side at the waterline at the after fireroom. The plane’s bomb went through the ship, resulting in “extremely severe flexural vibrations running through the ship for 20 seconds.” The three after engineering spaces flooded to the waterline immediately and the ship lost headway, taking on a five-degree list and starting to settle by the stern. Then, a third kamikaze, approaching from astern, dropped a small bomb that hit the aft port quad 40-mm gun (mount 44) and then crashed into the superstructure aft of the No. 2 stack and starting an intense fire in officers’ country. (In other accounts, the crew of mount 44 fired on the plane until the bitter end, with the mount’s gun captain’s last words being, “We’ll get the SOB.”)

Shock, fragment damage, and smoke rendered the ship’s 5-inch and 40-mm batteries entirely inoperable. As flooding spread to shaft alley and the machine shop, and the list increased to seven degrees, the commanding officer, concerned that the ship might capsize, gave a “prepare to abandon ship order.” (From the safety of Washington, DC, the BUSHIPS report assessed that the ship might very well have sunk, but there was minimal risk that it would capsize given the nature of the damage.)

Fortunately, at this point the CAP cavalry arrived and shot down many Japanese aircraft while Hugh W. Hadley was in an extremely vulnerable state, dead in the water with a fire raging amidships setting off munitions, listing to starboard with the fantail awash, and with the risk looming that the Torpex explosive in the torpedoes might explode. At this point, Commander Mullaney gave orders to hoist all available colors: “If this ship is going down, she’s going with all flags flying.” Mullaney also ordered most of the crew and the wounded over the side into life rafts, while 50 officers and men remained on board to make an attempt to save the ship. Torpedoes, depth charges, and unexploded ammunition was jettisoned (there wasn’t much ammunition left, Hugh W. Hadley had fired 801 rounds of 5-inch, 8,950 rounds of 40-mm, and 5,990 rounds of 20-mm ammunition). Topside weight was also jettisoned from the starboard side to try to correct the list. The forward boilers were secured so that they wouldn’t explode.

Initially, the Japanese aircraft focused on the two destroyers and the LSM(R) and three LCS(L)’s that provided what anti-aircraft support they could (the LCS[L]s had radar-directed fire control, but the LSM(R) did not). However, soon the amphibious vessels were fighting for their own lives.

LCS(L)-82 shot down three aircraft and assisted in downing two more. At 0837, LCS(L)-82 fired on and hit a Jill torpedo bomber heading for Evans. The Jill’s flight profile became erratic before it dropped a torpedo that missed Evans just before the plane crashed into the sea (this is probably the same aircraft noted above). At 0845, LCS(L)-82 assisted LCS(L)-84 in shooting down a Tony on the port side. Then, an Oscar came in from the starboard bow and gunners on LCS(L)-82 hit it repeatedly. As the plane passed overhead at 1,000 feet, it broke apart and debris fell toward LCS(L)-82. The skipper, Lieutenant Peter Beierl, adroitly maneuvered the vessel so that wings and engine fell in the wake. At 0940, a Val being pursued by CAP fighters passed astern and LCS(L)-82 gunners hit it, causing it to narrowly miss Evans, although some errant “friendly fire” hit Evans’ forecastle and started a fire. LCS(L)-82 then went alongside Evans to assist.

LCS(L)-83 shot down three Zekes and a “Tojo” (army fighter) between 0900 and 0939. LCS(L)-84 saw a Zeke diving on LCS(L)-83 and shot it down.

Despite LSM(R)-193’s less-than-optimum anti-aircraft capability, she also gave a good account of herself. At 0845, a Kate torpedo bomber dove on Evans, but missed and aimed for Lsm(R)-193 instead, but was shot down by 5-inch and 40-mm gunfire. At 0859, LSM(R)-193 shot down another Kate and then at 0912 shot down a Hamp (a Zeke variant). The LSM shot down a fourth plane and then assisted in shooting down yet another that was headed for Hugh W. Hadley. LSM(R)-193 subsequently went alongside her to assist in fighting the fire and tending to wounded.

When the Japanese attacks finally ended, LCS(L)-82 and LCS(L)-84 were alongside assisting the crippled Evans while Lsm(R)-193 and Lcs(L)-83 were alongside equally wounded Hugh W. Hadley. The combined efforts brought the fires and flooding on both destroyers under control. The destroyer Wadsworth (DD-516), fast transport Barber (APD-57), and fleet tug ATR-114 soon arrived to assist with rescue and towing. Evans was towed to Kerama Retto for emergency repairs and then towed across the Pacific to San Francisco, where she was decommissioned and later sold for scrap. Hugh W. Hadley was also towed to Kerama Retto and spent time in the floating drydock (ARD-28) before she was also towed across the Pacific, encountering heavy weather, but arriving at Hunters Point, California, where she, too, was determined to be too damaged to repair.

Evans’ casualties included 30 men killed and 29 wounded. Hugh W. Hadley’s losses were 30 killed and 68 wounded. The amphibious vessels suffered a number of wounded.

Given the volume of fire from all the ships and the chaos of battle, it is difficult to confirm which ship shot down which airplanes, and in many cases the credit would have to be shared. In most accounts, Evans is credited with shooting down 14 or 15 Japanese aircraft, and assisting with a number of others. The number usually cited for Hugh W. Hadley is 23 Japanese aircraft destroyed, although that number includes the three that crashed into her. Other accounts give a number of 19 or 20. Regardless, any of those numbers for Hugh W. Hadley represent the “all-time” U.S. Navy record for aircraft downed by a ship in a single engagement.

Both Hugh W. Hadley and Evans were awarded Presidential Unit Citations and their skippers, Commander Baron Mullaney and Commander Robert Archer, were each awarded a Navy Cross. The gunnery officer on Hugh W. Hadley, Lieutenant Patrick McGann, was also awarded a Navy Cross. The crew received seven (or eight) Silver Stars and eight Bronze Stars, and several other lesser awards. Crewmen on Evans probably received similar awards (but I can’t find a record). The four amphibious vessels were awarded Naval Unit Commendations, and the skipper of LSM(R)-193, Lieutenant Donald Boynton, was awarded a Silver Star. The skipper of LCS(L)-82, Lieutenant Peter Beierl, was awarded a Bronze Star, and so probably were the skippers of the other LCS(L)s whose names I can’t find.

As any good skipper would, Commander Mullaney of Hugh W. Hadley gave full credit to his crew, writing:

“No Captain of a man of war ever had a crew who fought more valiantly against such overwhelming odds. Who can measure the degree of courage of men who stand up to their guns in the face of diving planes that destroy them? Who can measure the loyalty of a crew who risked death to save the ship from sinking when all seemed lost? I desire to record that the history of the U.S. Navy was enhanced on 11 May 1945. I am proud to record that I know of no record of a Destroyer’s crew fighting for one hour and 25 minutes against overwhelming enemy aircraft attacks and destroying 23 planes. My crew accomplished their mission and displayed outstanding fighting abilities.”

As the Director of Naval History, I can second Commander Mullaney’s motion.

Navy Cross citation for Commander Baron Mullaney, commanding officer of Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774):

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain (then Commander) Baron Joseph Mullaney, United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of Destroyer USS HUGH W. HADLEY (DD-774), Radar Picket Ship, during an attack on that vessel by more than one hundred enemy Japanese planes off Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands on the morning of 11 May 1945. Fighting his ship against waves of hostile suicide and dive-bombing planes attacking from all directions, Captain Mullaney skillfully directed his men in delivering gunfire to shoot down nineteen enemy aircraft and, when a bomb and three kamikazes finally crashed on board and left the ship in flames with three of the engineering spaces flooded, persevered in controlling the damage until HADLEY could be towed sagely to port. Captain Mullaney’s leadership and professional skill in maintaining an effective fighting unit under the most hazardous conditions reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Naval Service.

Presidential Unit Citation for USS Hugh W. Hadley (DD-774):

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Presidential Unit Citation to the United States Ship USS HUGH W. HADLEY (DD-774) for service as set forth in the following citation; For extraordinary heroism un action as Fighter Direction Ship on Radar Picket Station Number 15 duirng an attack by approximately 100 enemy Japanese planes, forty miles northwest of the Okinawa Transport Area on 11 May 1945. Fighting valiantly against waves of hostile suicide and dive-bombing planes plunging toward her in all directions, the USS HUGH HADLEY sent up relentless barrages of anti-aircraft fire during one of the most furious air-sea battles of the war. Repeatedly finding her targets, she destroyed twenty planes, skillfully directed he Combat Air patrol in shooting down at least 40 others and, by her vigilance and superb battle readiness avoided damage herself until subjected to a coordinated attack by ten Japanese planes. Assisting in the destruction of all ten of these, she was crashed by one bomb and three suicide planes with devastating effect. With all engineering spaces flooded and with a fire raging amidships, the gallant officers and men if the HUGH W. HADLEY fought desperately against insurmountable odds and, by their indomitable determination, fortitude and skill, brought the damage under control, enabling their ship to be towed to port and saved. Her brilliant performance in the action reflects the highest credit upon the HUGH W. HADLEY and the United States Naval Service.

Navy Cross citation for Commander Robert J. Archer, commanding officer of USS Evans (DD-522):

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain (then Commander) Robert John Archer, for extraordinary heroism and distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the Destroyer USS Evans (DD-552) in action against enemy Japanese forces while assigned to Radar Picket duty off Okinawa on 11 May 1945. When his ship was subjected to attacks by an overwhelming force of enemy aircraft for one and one half hours, Captain Archer directed the gunfire of his batteries in shooting down fifteen enemy planes and assisting in the destruction of four others. Although the EVANS was severely damaged by hits from four suicide planes and in sinking condition, he led his crew in determined efforts to save the ship and bring her safe to port. His professional ability, courage and devotion to duty upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Also on 11 April, Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s flagship, Bunker Hill (CV-17), was hit by kamikaze aircraft in a devastating blow that resulted in the most deaths aboard a ship due to a kamikaze attack. I will cover this and the continuing rain of kamikaze on U.S. Navy ships in May and June 1945 in a future H-gram.

Sources include: “U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships Final Damage Report on HUGH W. HADLEY” (National Archives—related data available here); Kamikaze Attacks of World War II: A Complete History of Japanese Suicide Strikes on American Ships by Aircraft and Other Means, by Robin L. Rielly (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., Inc., 2010); Desperate Sunset: Japan’s Kamikazes Against Allied Ships, by Mike Yeo (London: Bloomsbury Press, 2019); The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers Against Japan, by William T. Y’Blood (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987); NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); and History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. XIV: Victory in the Pacific, by Samuel Eliot Morison (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1961).