Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Mobile Bay

Alabama

5–23 August 1864

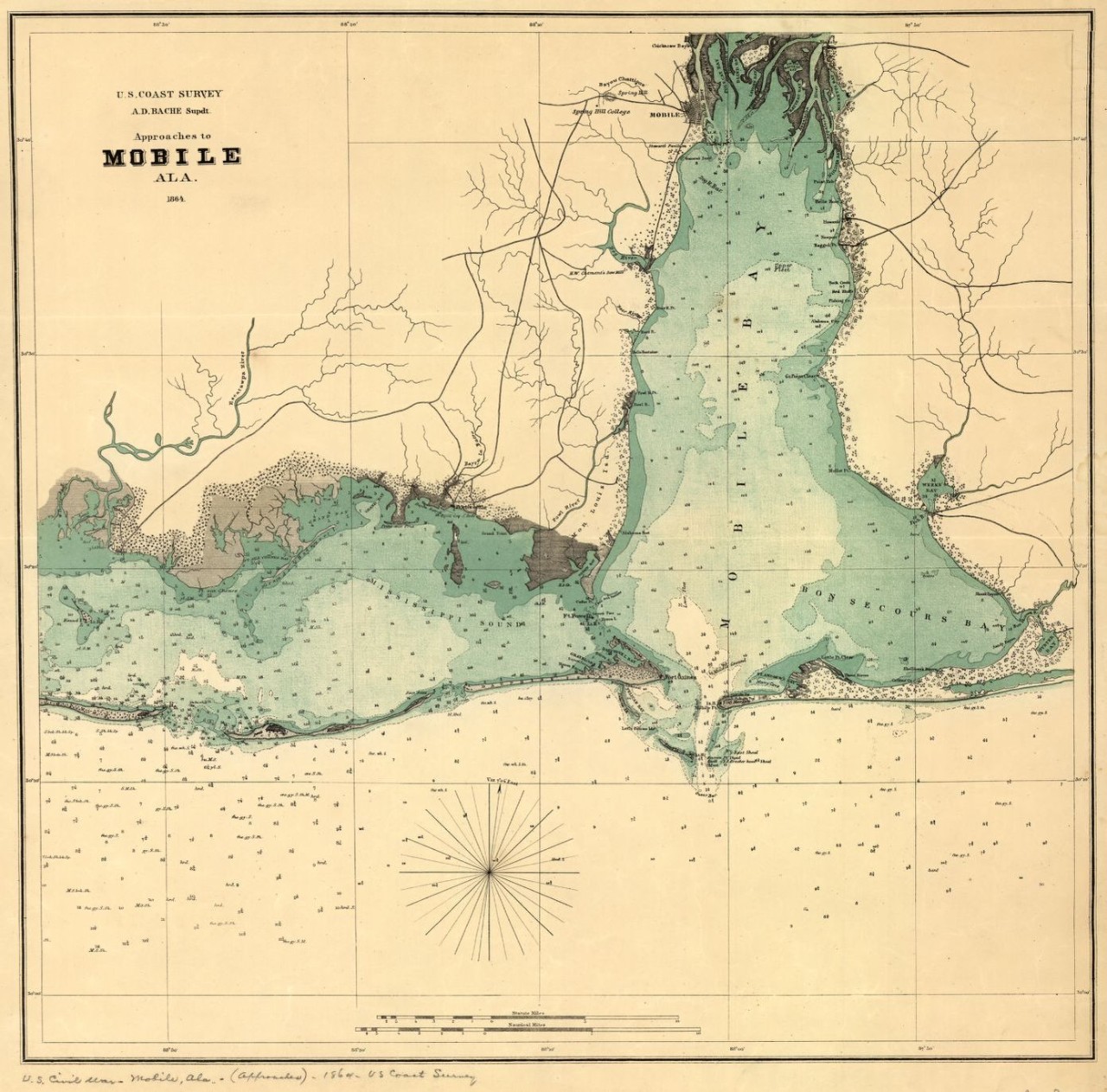

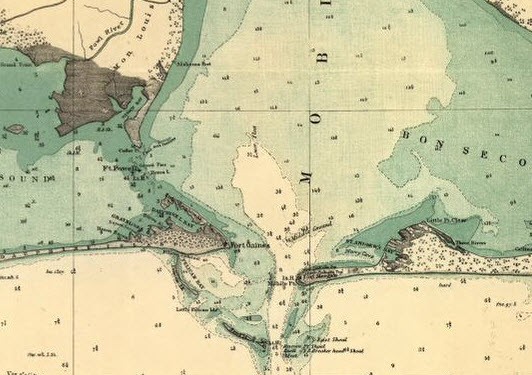

Map of approaches to Mobile Bay, produced by U.S. Coast Survey, 1864 (Library of Congress [LC], 99447256).

UNION LEADERSHIP

Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, U.S. Navy (USN)

Major General Gordon Granger, U.S. Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

Brigadier General Richard L. Page, Confederate States Army (CSA), Fort Morgan

Colonel Charles Anderson, CSA, Fort Gaines

Lieutenant Colonel James M. Williams, CSA, Fort Powell

BACKGROUND

In 1860, the South was a predominantly agricultural society. Cotton was its chief crop and the most valuable export in the United States. The city of Mobile, the only seaport in the state of Alabama, exported more cotton than any city in the United States except New Orleans. It was the 27th-largest city in the United States prior to January 1861. The state of Alabama seceded from the union in January 1861, and Mobile became the fourth-largest city in a new confederacy. Eight days before Alabama seceded from the United States, state militia moved in to take control of Fort Morgan, which guarded the main shipping channel leading into Mobile Bay. They also captured its companion fort, Fort Gaines, which was a work in progress and without a garrison.

On 19 April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade of all Southern ports, designed to prevent the export of cotton or the illegal import of weapons and supplies. A small percentage of cotton continued to be exported by Confederate blockade runners. It was the responsibility of the U.S. Navy to halt this activity. In May 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles established two squadrons to enforce the blockade and prevent the trade with the South. Welles assigned the Gulf Blockading Squadron to patrol 1,500 miles of coastline from Key West to the border with Mexico.

Less than a year later, Welles split the Gulf squadron into two out of frustration, hoping to improve its efficiency.[1] He retained the squadron’s leader, Flag Officer William McKean, and appointed Flag Officer David G. Farragut to split the responsibility between East and West. Welles entrusted Farragut with the plans to regain control of all the Confederate-held ports in the eastern half of the Gulf of Mexico, including New Orleans and Mobile.[2] Decisions on where to attack first depended on both the shifting priorities of the U.S. Army and the value of the target. Plans for attack first centered on the port of New Orleans and its significance to any effort by the U.S. forces to control the Mississippi River.

In his preparations for an attack on New Orleans, Farragut was reluctant to commit his forces too soon. Despite rumors in the port city of the danger posed by the U.S. Navy, Farragut knew an element of surprise was essential to victory. Farragut wrote to Gustavus Fox, the assistant secretary of the Navy that, “I wish to keep up the delusion that Mobile is the first object of attack.”[3] On 24 April, Farragut successfully ran most of his fleet past the forts guarding the entrance to capture the city. The fall of New Orleans in April 1862 left Mobile as the only Confederate-held port on the Gulf Coast. Farragut’s success earned him a promotion to admiral in July 1862.

His plans for Mobile had to wait after the Federal advance down the Mississippi River stalled north of Vicksburg. It was July 1863 before the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson signaled the re-opening of the Mississippi River and an opportunity for Farragut to focus on Mobile.

PRELUDE

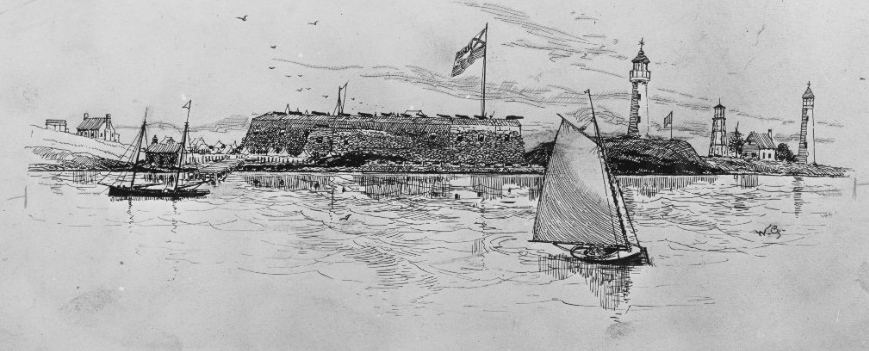

The city of Mobile was at the northern end of the bay, which was 30 miles long and 24 miles wide. Much of the bay was shallow, approximately 10 feet in depth. While the U.S. Navy patrolled the coastline to enforce the blockade, the Confederate forces at Mobile worked to fortify their coastal defenses. Two narrow channels connected the bay to the Gulf of Mexico. The wider of the two channels passed between Forts Morgan and Gaines. Between these two forts, the Confederate navy moored a line of torpedoes (naval mines) to force any passage under the guns of Fort Morgan.

Selection from map of the approaches to Mobile Bay produced by U.S. Coast Survey, 1864 (LOC, 99447256).

On the western approach to the bay, another channel ran from the Mississippi Sound through Grant’s Pass. The Confederates built a third battery on an oyster reef in the middle of this channel, which they named Fort Powell. These three forts were their first line of defense; the Confederate navy would provide the second. The coastal defenses at Mobile Bay, supported by a small squadron of enemy ships prevented the U.S. Navy from any attempt to take control of the bay without the cooperation of the U.S. Army. Farragut had no choice except to wait until the priorities of the U.S. Army shifted in his favor.

Farragut was not the only one subject to shifting priorities. The capture of New Orleans in April 1862 and the increasing likelihood of losing control of the Mississippi River made it more important than ever for the Confederacy to retain control of Mobile. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory had appointed Captain Victor Randolph to command naval defense at Mobile in February 1862. After Randolph spent months biding his time and making demands for ironclads, Mallory decided to make a change. In August 1862, Franklin Buchanan became the first and only admiral in the Confederate navy. Mallory immediately sent him to Mobile as Randolph’s replacement.

The change in leadership did not change the needs of the Confederate navy at Mobile. The small squadron needed an ironclad if they hoped to defend the bay against a full-fledged attack. Buchanan, like his predecessor, advocated for more ironclads. After his experience during the battle of Hampton Roads as the captain of such a vessel, he knew its advantages against the superior numbers of the U.S. Navy. In October 1862, Mallory and Buchanan added a third ironclad to their contract to a local shipbuilder, Henry D. Bassett. In February 1863, CSS Tennessee launched from Selma and headed to Mobile for its machinery and armament.[4] Buchanan finally had his ironclad.

In early 1864, the U.S. Army finally made the capture of Mobile into a top priority. On 18 January, Farragut arrived off Mobile Bay to inspect his squadron and evaluate the Confederate defenses. Based on intelligence, he knew that a protective field of torpedoes was moored under the surface at the entrance to the bay. Farragut knew that their presence along the narrow four-mile gap between Mobile Point (Fort Morgan) and Dauphin Island (Fort Gaines) required his ships to pass right after the guns of Fort Morgan.

On 8 July, Farragut met with Generals Edward Canby and Gordon Granger on board his flagship Hartford.[5] Canby agreed to send troops from the Military Division of West Mississippi to cooperate with Farragut’s incursion into Mobile Bay. With this promise, Farragut began to prepare his vessels for an attack. On 12 July, he issued a general order to prepare all vessels, including specific instructions for his plan of attack.[6]

On 29 July, Canby finally launched his transports with 1,500 infantry under Granger’s command, accompanied by artillery and engineering units. Unfortunately, a delay of a troop movement from Texas prevented Canby from sending more. He suggested to Farragut that this force was sufficient for an attack on Dauphin Island (Fort Gaines).[7] He promised more men for a joint assault on Fort Morgan.[8]

On 1 August, Granger and Farragut met to coordinate their joint assault. On 3 August, a naval detachment from Farragut’s fleet—Conemaugh, Estrella, J. P. Jackson, Narcissus, and Stockdale—escorted Granger’s transports up the Mississippi Sound to Dauphin Island.[9] Granger’s command disembarked on the western tip of the island, prepared to attack Fort Gaines whenever Farragut’s fleet made their move to enter the bay. With Granger’s forces in position, their escort detachment headed for Fort Powell.

On the afternoon of 4 August, Farragut held a meeting of his captains aboard Hartford. The plan was similar to what he had enacted at Port Hudson the prior year. He called for a two-column approach on Fort Morgan with the ironclad monitors masking the second column of wooden ships. The second column was actually two columns lashed together, as he ordered a smaller gunboat lashed to the port side (facing away from Fort Morgan) of each of the seven larger sloops-of-war—Brooklyn, Hartford, Richmond, Lackawanna, Monongahela, Ossipee, and Oneida. The attack was to be organized in a step-like formation (en échelon), slightly behind and on the starboard of the vessel in front of them to allow a wider field of fire for bow guns. After a slight delay, Farragut prepared for his attack on the morning of 5 August 1864.

BATTLE

Before dawn on 5 August 1864, 14 wooden vessels and four ironclads of U.S. Navy waited for the signal from their commander to run past Fort Morgan into Mobile Bay. At 0600, all 18 ships were ordered to up anchor and proceed toward Fort Morgan. The ironclads—Tecumseh, Manhattan, Chickasaw, and Winnebago—engaged Fort Morgan first, staying to the east of the column of wooden vessels. The second column of wooden vessels ran alongside and slightly behind the column of ironclads.

As Farragut’s fleet approached, Buchanan watched from aboard his ironclad flagship Tennessee. His small squadron of wooden gunboats—Gaines, Morgan, and Selma—waited nearby. With a line of torpedoes forcing the enemy under the guns of Fort Morgan, Buchanan had no reason to take the offensive yet.

Passing a buoy that marked the end of the Confederate minefield, Tecumseh hit a torpedo,[10] which blew a hole in its hull and quickly sank the ironclad.[11] Watching the ironclad sink with the Confederate ironclad ram Tennessee waiting to for an opening, Captain James Alden of Brooklyn hesitated at the head of the second column, stopping any further movement through the narrow channel under the guns of Fort Morgan.[12] Frustrated by Alden’s pause, Farragut ordered Captain Percival Drayton to take the lead. Drayton guided Hartford around Brooklyn, heedless of the sunken torpedoes (this is the point at which Farragut is often quoted as saying “Damn the torpedoes.” Although the exact words are often subject to speculation, the sentiment remains true).[13] Hartford fired broadside at Tennessee as the ship passed through the minefield without incident. Commander James D. Johnston, of Tennessee, attempted without success to ram the leaders as they passed the minefield, but the ironclad proved too slow to outmaneuver the enemy.[14]

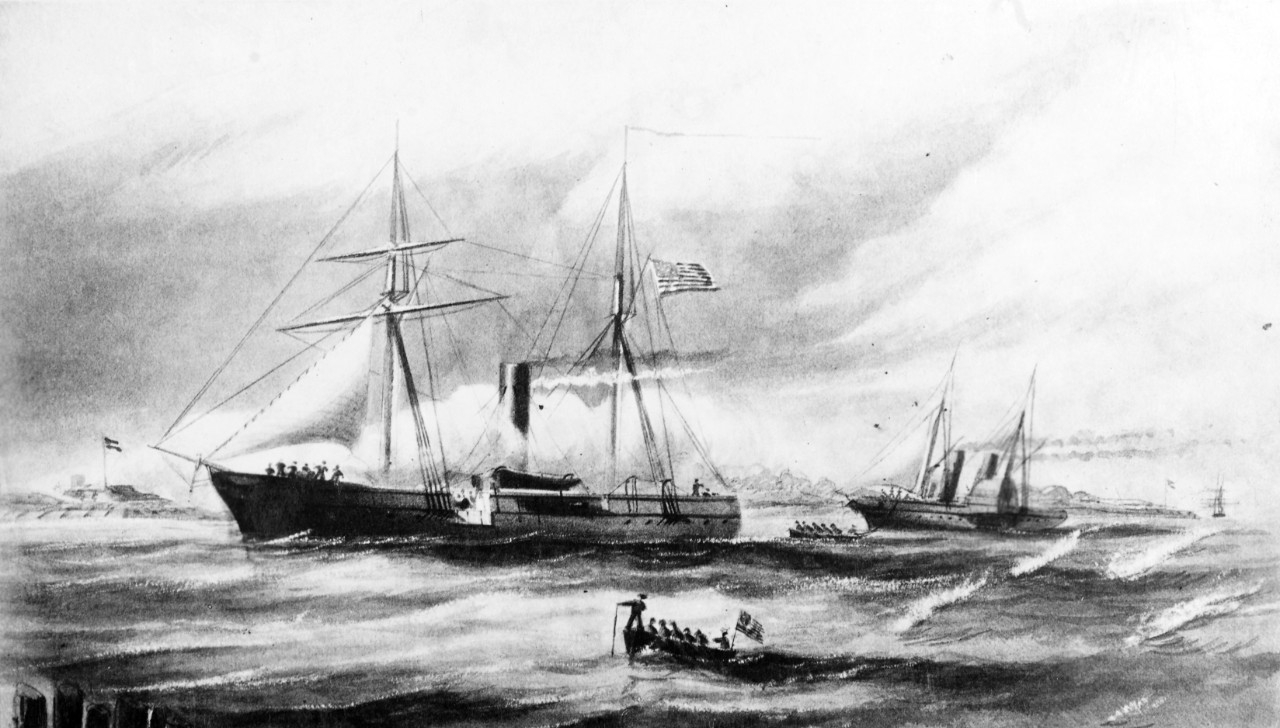

J. O. Davidson, Battle of Mobile Bay, Passing Fort Morgan and the Torpedoes, August 1864, 1886, lithograph (print) by L. Prang and Co. (LOC, 2003663830). This print depicts the naval battle shortly after the sinking of Tecumseh. The Confederate ships (left) are Morgan, Gaines, and Tennessee. The Federal monitors following Tecumseh are Manhattan and Winnebago. Brooklyn (right) is leading the outer line of U.S. warships, immediately followed by Hartford.

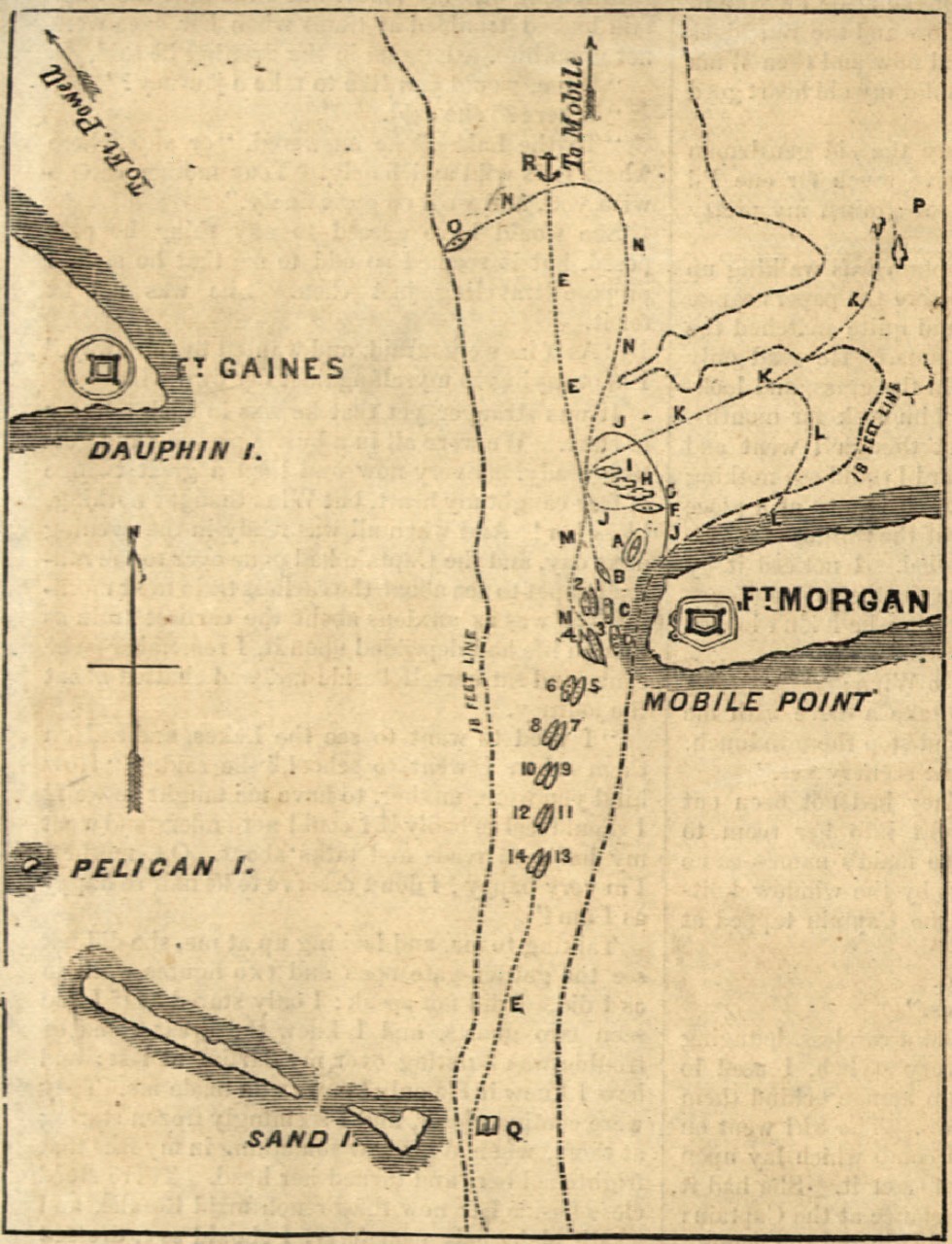

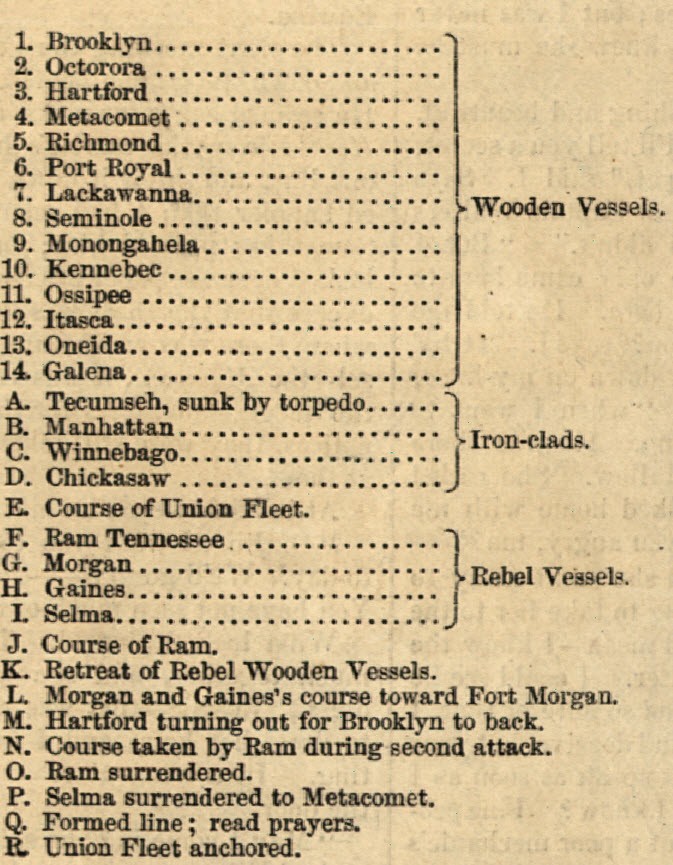

Above: Plan of the battle of Mobile Bay, 5 August 1864, originally published in Harper's Weekly, 24 September 1864. Left: Map key with the names of ships corresponding to the numbers and the letters on the map (LC, 99447253).

By 0830, all but one of Farragut’s fleet had passed the fort. Preparing to engage the enemy squadron, the second column broke apart as the senior officer of each pair of vessels cast off their lines.[15] Farragut ordered the captain of Metacomet to lead pursuit of Buchanan’s wooden gunboats.[16] While engaged with Metacomet, CSS Selma became a target of another Federal steamer—Port Royal.[17] Outnumbered and outgunned, captain of Selma surrendered the ship. Under fire, the crew of CSS Gaines were forced to beach their injured vessel after the ship started taking on water. Morgan remained afloat, running for the cover of the fort. With his squadron scattered, Buchanan had only Tennessee left under his command. At approximately 0845, he ordered the ironclad into action. He was determined to try to sink an enemy ship before this battle ended.[18]

As Tennessee slowly approached, Farragut ordered the Federal ironclads and larger wooden ships to run down the Confederate ram. Two of the faster wooden ships, Monongahela and Lackawanna, reached the enemy first. Neither the full impact of the sloops-of-war striking the sides of the ironclad nor their cannonballs did any significant damage to its heavy armor. Farragut crashed Hartford into the ironclad, bringing the number of collisions to three. In this one-sided engagement, there was more damage to Farragut’s fleet than to the ironclad. The Federal monitors arrived next, unleashing fire on Buchanan’s flagship. Surrounded by the enemy fleet, Tennessee appeared uninjured, although it ceased returning fire. As Hartford was preparing to strike again, Tennessee raised the white flag. [19]

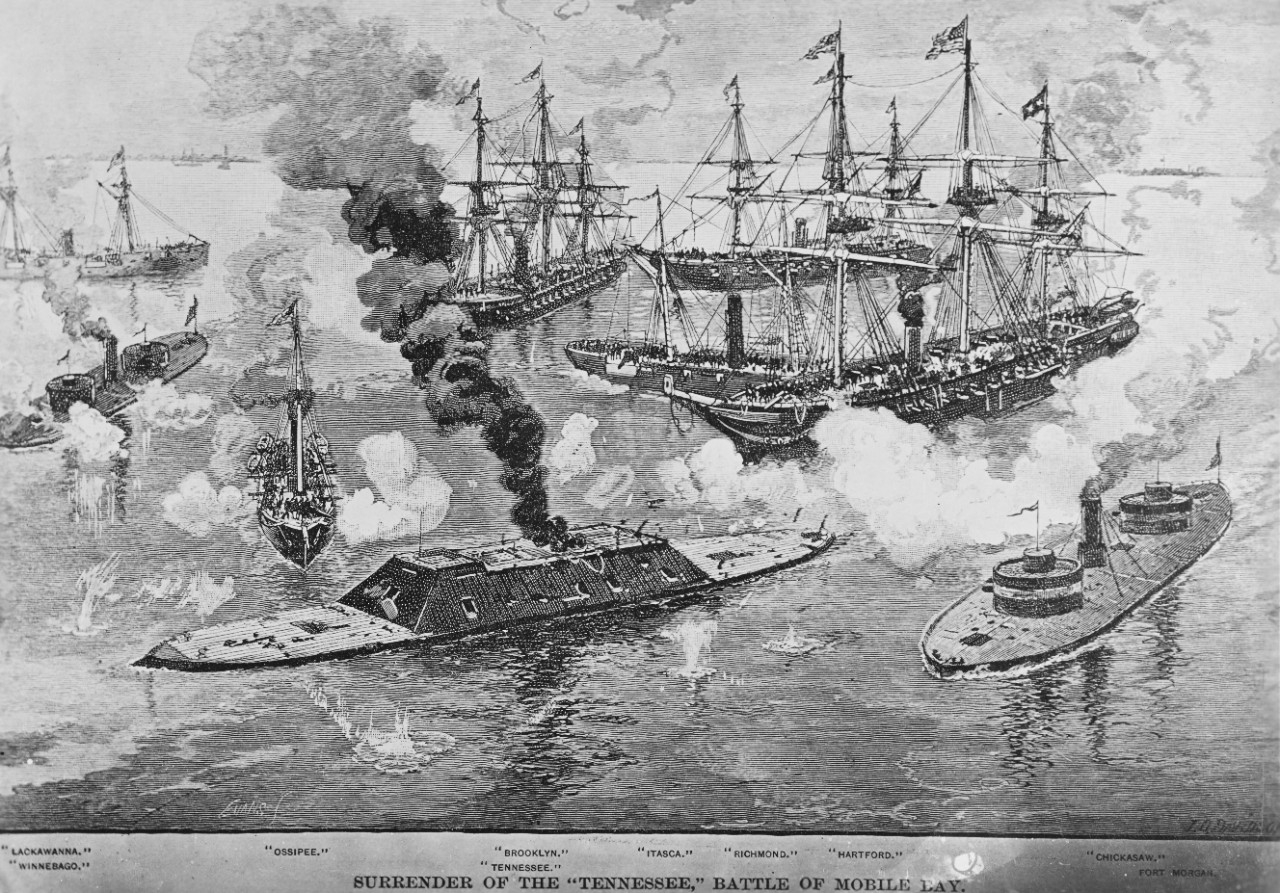

J.O. Davidson, Surrender of the 'Tennessee,' Battle of Mobile Bay, 1888. This artwork depicts CSS Tennessee (center), surrounded by the Federal warships (left to right): Lackawanna, Winnebago, Ossipee, Brooklyn, Itasca, Richmond, Hartford, and Chickasaw. Fort Morgan is shown in the right distance. (NHHC, NH-1276).

Buchanan had told Johnston to “ ‘Do the best you can, sir, and when all is done, surrender.’”[20] Watching the enemy close in, Johnston quickly realized that his vessel was “nothing more than a target.”[21]

At 1000, Commander Johnston surrendered his sword.[22] Buchanan had been injured in the leg during the fight, so Johnston surrendered his weapon on his behalf. As a prisoner of war, Admiral Buchanan was sent to Pensacola for treatment. That night, Morgan made a desperate run for Mobile and succeeded in escaping capture.[23] The surrender of Tennessee marked the end of the naval battle for control of Mobile Bay.

Despite Buchanan’s surrender, the battle between ship and shore continued for another two weeks. Farragut sent the monitor Chickasaw to join the detachment—Conemaugh, Estrella, J.P. Jackson, Narcissus, and Stockdale—already engaged at Fort Powell. With Chickasaw firing into the rear of the fort and the others firing from the Mississippi Sound, it was not long before the commander of the garrison asked the advice of his superiors at Fort Gaines. Given the choice to stand or to retreat, Lieutenant Colonel James M. Williams left with his garrison the same night.[24] Before departing, they set explosives to destroy the fort.

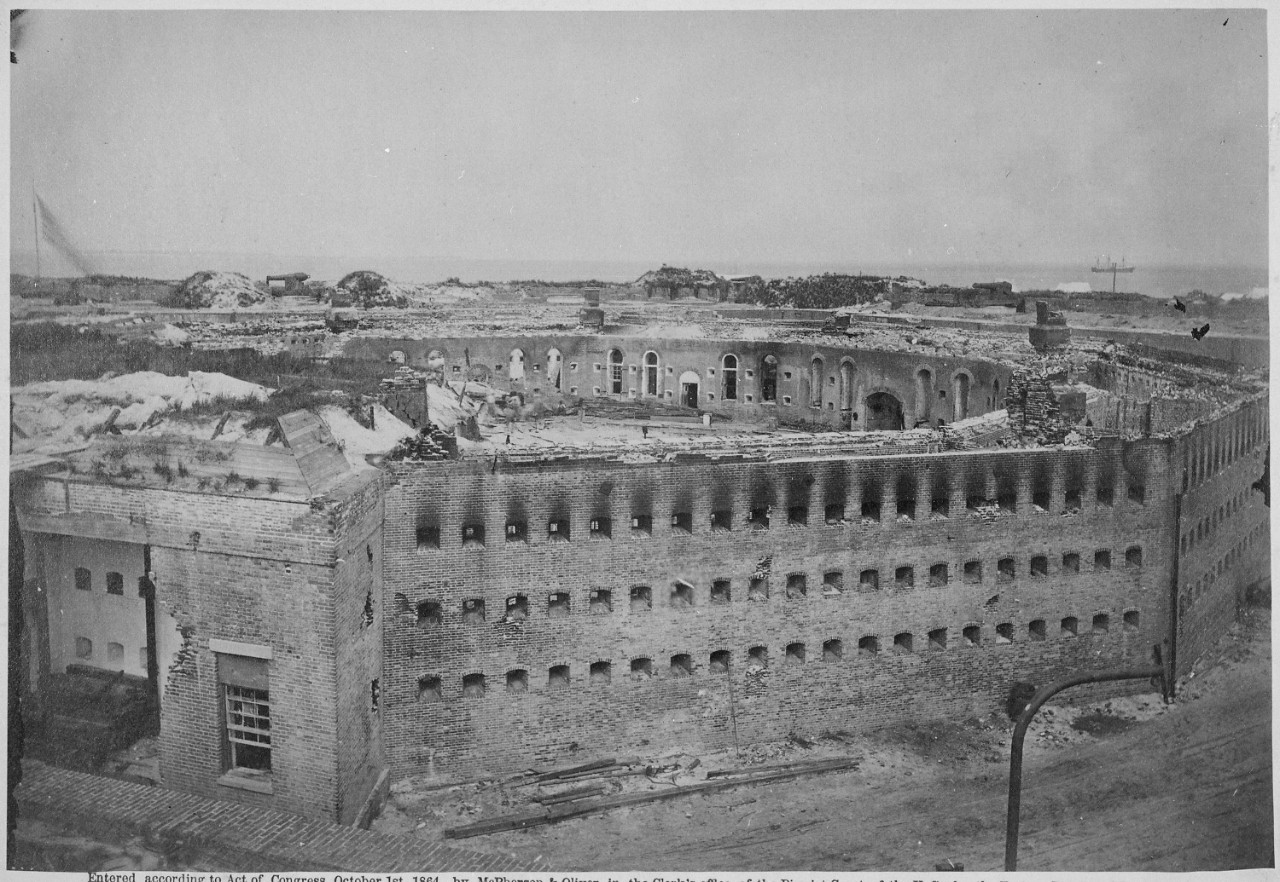

Granger’s forces had already taken Dauphin Island and besieged Fort Gaines. With the combined firepower of Granger’s artillery and Farragut’s gunboats, the fort capitulated within three days on 8 August. Preparing to move to Fort Morgan, Granger wrote to Canby asking for the promised reinforcements.[25] All Federal forces in Mobile Bay converged on the last remaining Confederate-held fort in Mobile Bay. Farragut and Granger demanded the unconditional surrender of the fort, but its commander refused to surrender while he had any means to defend the fort.[26] Seeking to demoralize the enemy, Farragut prepared the captured ram Tennessee to join the monitors firing upon the fort. He continued shelling of Fort Morgan for the next two weeks until the another white flag was raised. Page finally surrendered the fort.[27] On 23 August, all three forts guarding Mobile Bay were under the control of the U.S. forces.

AFTERMATH

The city of Mobile had no military significance after the closing of the port to Confederate blockade runners. Farragut insisted that occupation of the city would be more trouble than it was worth given the number of troops that would be required for this action. Although Canby accepted that the occupation of Mobile could favor the campaign against Atlanta, he agreed with Farragut. He knew it would be impossible to hold the city without more troops.[28] The city of Mobile remained under Confederate control until April 1865.

On 3 September 1864, President Abraham Lincoln commanded a 100-gun salute at the Washington Navy Yard to honor the victory at Mobile Bay.[29] In the same message, he ordered a second salute to honor the capture of Atlanta. From the overland campaign by Ulysses S. Grant in the spring of 1864 to the victory at Mobile Bay to the fall of Atlanta, this year seemed to mark the beginning of the end of the Confederacy.

After the capture of Mobile Bay, Wilmington, North Carolina, was the Confederacy’s last port of call for blockade runners. In September, Welles sent Farragut an offer to assume command the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron and lead an expedition against Wilmington. Farragut was surprised to receive such a difficult assignment given a recent request for leave. [30] Welles acknowledged his concerns and substituted another for the assignment while Farragut remained in Mobile. In November, Farragut finally received his leave of absence to rest and recuperate.

After the capture of Mobile Bay, it was months before Canby managed to accumulate enough troops to attack the city. The final phase of this campaign began on 25 March 1865 and the city surrendered on 12 April, three days after the signing of the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Courthouse.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Battle of Mobile Bay: Selected Documents

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Mobile Bay - August 5, 1864, American Battlefield Trust.

Naval Operations in the Gulf of Mexico, American Battlefield Trust.

FURTHER READING

Browning, Robert M., Jr. “‘Go Ahead, Go Ahead.’” Naval History 23, no. 6 (December 2009): 28–36.

Hearn, Chester G. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign: The Last Great Battles of the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 1993.

Higginbotham, Jay. Mobile: City by the Bay. Mobile, AL: Azalea City Printer, 1968.

Mattei, Eileen. “A Tale of Two Forts on Mobile Bay: Fort Gaines and Fort Morgan.” On Point 20, no. 2 (2014): 36–43.

Smithweck, David. The USS Tecumseh in Mobile Bay: The Sinking of a Civil War Ironclad. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2021.

***

NOTES

[1] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereafter ORN), 30 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), Series 1, Volume 17 (1903), 56.

[2] ORN, 18 (1904), 7–8.

[3] ORN, 1, 18:47.

[4] R. Thompson Campbell, Voices of the Confederate Navy: Articles, Letters, Reports, and Reminiscences (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2008), 104.

[5] ORN, 1, 21 (1906), 416.

[6] ORN, 1, 21:397–98; Battle of Mobile Bay: Selected Documents.

[7] ORN, 1, 21:388.

[8] ORN, 1, 21:38.

[9] ORN, 1, 21:502–03.

[10] ORN, 1, 21:442.

[11] ORN, 1, 21:490.

[12] ORN, 1, 21:783.

[13] ORN, 1, 21:405, 417.

[14] ORN, 1, 21:580.

[15] ORN, 1, 21:398.

[16] ORN, 1, 21:405.

[17] ORN, 1, 21:448, 784.

[18] ORN, 1, 21:443.

[19] ORN, 1, 21:417–18.

[20] ORN, 1, 21:580.

[21] ORN, 1, 21:580.

[22] ORN, 1, 21:418.

[23] ORN, 1, 21:418.

[24]U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter ORA), 128 vols. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 39, pt. 1 (1891), 441–42; James Williams, From That Terrible Field: Civil War Letters of James M. Williams, 21st Alabama Infantry Volunteers (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1981), 136.

[25] ORA, 1, 39, pt. 1, 417.

[26] ORA, 1, 39, pt. 1, 439.

[27] ORA, 1, 39, pt. 1, 438.

[28] ORN, 1, 21:610.

[29] ORN, 1, 21:543.

[30] ORN, 1, 21:656.