Hartford I

1859–1956

The capital of the state of Connecticut.

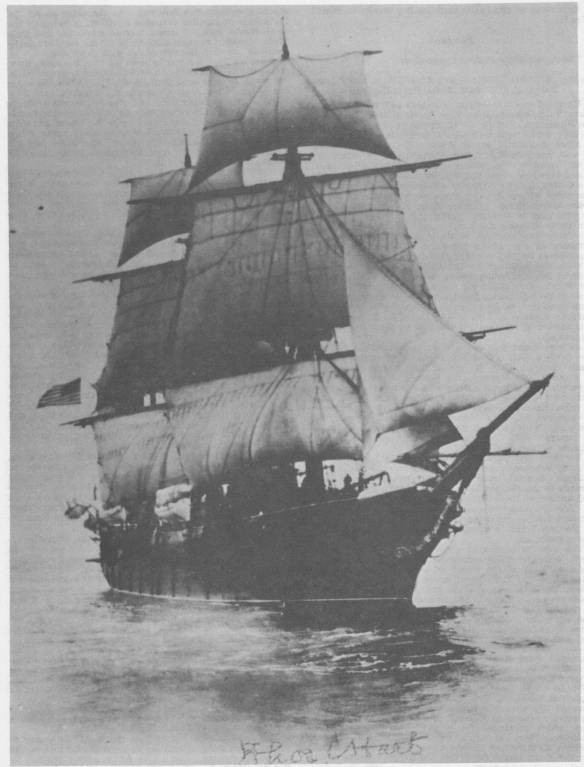

Hartford was launched 22 November 1858 by the Boston Navy Yard; sponsored by Miss Carrie Downes, Miss Lizzie Stringham, and Lt. G. J. H. Preble; and commissioned 27 May 1859, Captain Charles Lowndes in command.

After shakedown out of Boston, the new screw sloop of war, carrying Flag Officer Cornelius K. Stribling, the newly appointed commander of the East India Squadron, sailed for Cape Hope and the Far East. Upon reaching the Orient, Hartford relieved Mississippi as flagship. In November she embarked the American Minister to China, John Elliott Ward, at Hong Kong and carried him to Canton, Manila, Swatow, Shanghai, and other Far Eastern ports to settle American claims and to arrange for favorable consideration of the Nation's interests. Her presence, as a symbol of American sea power, materially contributed to the success of Ward's diplomatic efforts.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Hartford was ordered home to help preserve the Union. She departed the Strait of Sumda with Dacotah 30 August 1861 and arrived Philadelphia 2 Decemlber to be fitted out for wartime service. She departed the Delaware Capes 28 January as flagship of Flag Officer David G. Farragut, the commander of the newly created West Gulf Blockading Squadron.

An even larger purpose than the important blockade of the South's Gulf Coast lay behind Farragut's assignment. Late in 1861, the Union high command decided to capture New Orleans, the South's richest and most populous city, to begin a drive of sea-based power up the Father of Waters to meet the Union Army which was to drive down the Mississippi valley behind a spearhead of armored gunboats. Other operations," Secretary of the Navy Welles warned Farragut, "must not be allowed to interfere with the great object in view, the certain capture of the city of New Orleans."

Hartford arrived 20 February at Ship Island, Miss., midway between Mobile Bay and the mouths of the Mississippi. Several Union ships and a few Army units were already in the vicinity when the squadron's flagship dropped: anchor at the advanced staging area for the attack on New Orelans. In ensuing weeks a mighty fleet assembled for the campaign. In mid-March Comdr. David D. Porter's flotilla of mortar schooners arrived towed by steam gunboats.

The next task was to get Farragut's mighty, deep-draft, saltwater ships across the bar, a constantly shifting mud bank at the mouth of each pass entering the Mississippi. At the cost of endless toil and a month's delay, Farragut managed to get all of his ships but Colorado across the bar and into the river where Forts St. Philip and Jackson challenged further advance. A line of hulks connected by strong barrier chains, six ships of the Confederate Navy, including Ironclad Manassas and unfinished but potentially deadly ironclad Louisiana, two ships of the Louisiana Navy, a group of converted river steamers called the Confederate River Defense Fleet, and a number of fire rafts also stood between Farragut and the great Southern metropolis.

On 16 April, the Union ships moved up the river to a position below the forts, and Porter's gunboats first exchanged fire with the Southern guns. Two days later his mortar schooners opened a heavy and methodical barrage which continued for 6 days. On the 21st, the squadron's Fleet Captain, Henry H. Bell, led a daring expedition up river and, despite a tremendous fire on him," cut the chain across the river. In the wee hours of 24 April, a dull red lantern on Hartford's mizzen peak-signaled the fleet to get underway and steam through the breach in the obstructions. A wild night action of far reaching consequence followed. As the ships closed the forts their broadsides answered a withering fire from the Confederate guns. Porter's mortar schooners and gunboats remained at their stations below the southern fortifications covering the movement with rapid fire.

Hartford dodged a run by ironclad ram Manassas; then, while vainly attempting to avoid a fireraft, grounded in the swift current near Fort St. Philip. When the burning barge was shoved alongside the flagship, only Farragut's gallant leadership and the disciplined training of the crew saved Hartford from being destroyed by flames which at one point engulfed a large portion of the ship. Meanwhile the sloop's undaunted gunners never slackened the pace at which they poured broadsides into the forts. As her firefighters snuffed out the flames, the flagship backed free of the bank.

When Farragut's ships had run the gauntlet and passed out of range of the fort's guns, the Confederate River Defense Fleet made a daring but futile effort to stop their progress. In the ensuing melee, they managed to sink converted merchantman Varwut, the only Union ship lost during the historic night.

The next day, after silencing Confederate batteries which had opened on them from earthen works, a few miles below New Orleans, Hartford and her sister ships anchored off the city early in the afternoon. A handful of ships and men had won a great decisive victory that secured the South could not win the war.

The conquest of New Orleans deprived the South of its greatest center of wealth, commerce and industry as well as her most important outlet to the sea. It was also the first thrust of the mighty pincer movement which ultimately cut the South in two dooming it to defeat.

Early in May, Farragut ordered several of his ships up stream to clear the river and followed himself in Hartford on the 7th to join in the conquest of the valley. Defenseless, Baton Rouge and Natchez promptly surrendered to the Union ships and no significant opposition was encountered until 18 May when the Confederate commandant at Vicksburg replied to Comdr. S. P. Lee's demand for surrender: ". . . Mississippians don't know and refuse to learn, how to surrender to an enemy. If Commodore Farragut or Brigadier General Butler can teach them, let them come and try."

When Farragut arrived on the scene a few days later, he learned that heavy Southern guns mounted on the bluff at Vicksburg some 200 feet above the river could shell his ships while his own guns could not be elevated enough to ait them back. Since sufficient troops were not available to take the fortress by storm, the Flag Officer headed downstream 27 May leaving gunboats to blockade it from below.

Orders awaited Farragut .at New Orleans, where he arrived on the 30th, directing him to open the river and join the Western Flotilla and stating that Lincoln himself had given the task highest priority. The Flag Officer recalled Porter's mortar schooners from Mobile and dutifully got underway up the Mississippi in Hartford 8 June.

The Union Squadron was assembled just below Vicksburg by the 26th. Two days later the Union ships, their own guns blazing at rapid fire and covered by an intense barrage from the mortars, suffered little damage while running past the batteries. Flag Officer Davis, commanding the Western Flotilla, joined Farragut above Vicksburg on the 30th; but again, naval efforts to take Vicksburg were frustrated by a lack of troops. "Ships," Porter commented, ". . . cannot crawl up hills 300 feet high, and it is that part of Vicksburg which must 'be taken by the Army." On 22 July, Farragut received orders to return down the river at his discretion and he got underway on the 24th, reached New Orleans in 4 days, and after a fortnight -sailed to Pensacola, Fla., for repairs.

The flagship returned to New Orleans 9 November to prepare for further operations in the unpredictable waters of the Mississippi. The Union Army, ably supported by the Mississippi Squadron, was pressing, on Vicksburg from above, and Farragut wanted to assist in the campaign by blockading the mouth of the Red River from wihich suip plies were pouring eastward to the Confederate Army. Meanwhile, the South had been fortifying its defenses along the river and had erected 'powerful batteries at Port Hudson, La.

On the night of 14 March, Farragut in Hartford and accompanied by six other ships, attempted to run by these batteries. However, they enconhtered such heavy and accurate fire that only the flagship and Albatross, lashed alongside, succeeded in running the gauntlet. Thereafter, Hartford and her consort patrolled between Port Hudson and Vicksburg denying the Confederacy desperately needed supplies from the West.

Porter's Mississippi Squadron, cloaked toy night, dashed downstream past the Vicksburg batteries 16 April, while General Grant inarched his troops overland to a new base also below the Southern stronghold. April closed with the Navy ferrying Grant's troops across the river to Bruinsburg whence they encircled Vicksburg and forced the beleaguered fortress to surrender on the Fourth of July.

With the Mississippi River now opened, Farragut turned his attention to Mobile, Ala., a Confederate industrial center still building ships and turning out war supplies. The Battle of Mobile took place 5 August 1864. Farragut, with Hartford as his flagship, led a fleet consisting of 4 ironclad monitors and 14 wooden vessels. The Confederate naval force was composed of newly built ram Tennessee, Admiral Buchanan's flagship, and steamers Selma, Morgan, and Oaines ; and backed by the powerful guns of Forts Morgan and Gaines in the Bay. From the firing of the first gun by Fort Morgan to the raising of the white flag of surrender by Tennessee little more than 3 hours elapsed-but 3 hours of terrific fighting on both sides. The Confederates had only 32 casualties, while the Union forces suffered 335 casualties, including 113 men drowned in Tecumseh when the monitor struck a torpedo and sank.

Returning to New York December 13, Hartford decommissioned for repairs a week later. Back in shape in July 1865, she served as flagship of a newly-organized Asiatic Station Squadron until August 1868 when she returned to New York and decommissioned. Recommissioned 9 October 1872, she resumed Asiatic 'Station patrol until returning home 19 October 1875. In 1882, as Captain Stephen B. Luce's flagship of the North Atlantic Station, Hartford visited the Caroline Islands, Hawaii, and Valparaiso, Chile, before arriving San Francisco 17 March 1884. She then cruised in the Pacific until decommissioning 14 January 1887 at Mare Island, Calif., for apprentice sea-training use.

From 1890 to 1899 Hartford was laid up at Mare Island, the last 5 years of which she was being rebuilt. On 2 October 1899, she recommlssioned, then transferred to the Atlantic coast to be used for a training and cruise ship for midshipmen until 24 October 1912 when she was transferred to Charleston, S.C., for use as a station ship.

Again placed out of commission 20 August 1926, Hartford remained at Charleston until moved to Washington, D.C., 18 October 1938. On 19 October 1945, she was towed to the Norfolk Navy Yard and classified as a relic. Hartford sank at her berth 20 November 1956. She was subsequently dismantled. Major relics from her are at the National Navy Memorial Museum, Washington (D.C.) Navy Yard, and elsewhere.