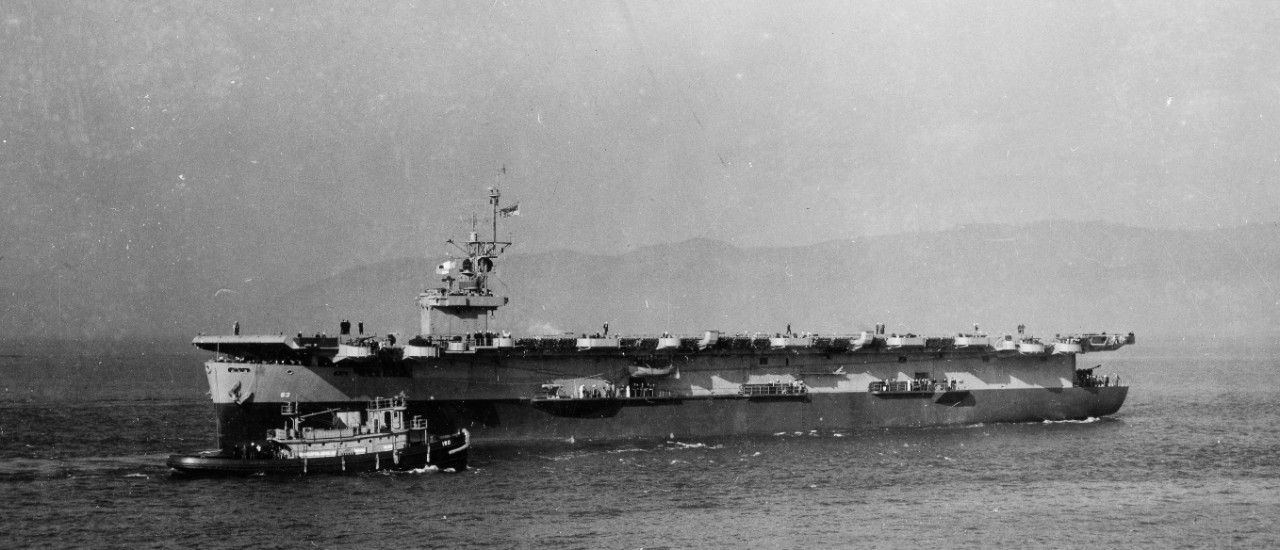

Midway II (CVE-63)

1943–1944

The first Midway was named for the atoll, the second and third for the battle that occurred between 4–7 June 1942. Midway (CVE-63) was renamed St. Lo effective on 10 October 1944, to commemorate the victory of U.S. troops in France who had captured that strongly defended town on 18 July 1944.

II

(CVE‑63: displacement 10,982 (full load); length 512'3"; beam 65'; extreme width (flight deck) 108'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 19 knots; complement 860; aircraft 28; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40-millimeter, 20 20-millimeter; class Casablanca)

The auxiliary aircraft carrier Chapin Bay (ACV-63) was laid down on 3 January 1943 by the Kaiser Shipbuilding Co., under a Maritime Commission contract (M. C. Hull 1100); renamed Midway on 3 April 1943; reclassified as an escort aircraft carrier, CVE-63, launched on 17 August 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Leonie Cauchois Coulter, wife of Capt. Howard N. Coulter, commanding officer of Naval Air Station (NAS) (Lighter-than-Air) Santa Ana, Calif.; and commissioned alongside Pier 3, U.S. Naval Station, Astoria, Ore., on 23 October 1943, Capt. Francis Joseph McKenna in command.

Midway lay alongside Pier 3 at Astoria midday on 13 November 1943, at which point Lt. Cmdr. H. B. Clark and Lt. Cmdr. Langkilde, USCG, pilots, reported on board. The ship stood out of Astoria harbor less than an hour later, escorted first by the airship K-29, then by the submarine chaser SC-536, the former present from 1245 to 1851, and the latter from 1623 to 1715.

After having been piloted in by Lt. Cmdr. A. Fulmar, USNR, Midway anchored in Port Townsend, Wash., harbor the next morning [14 November 1943]. Underway again with Lt. Cmdr. Fulmar at the conn, the new escort carrier stood out of the Port Townsend anchorage, then passed Point No Point shortly after the midpoint of the afternoon watch. Midway embarked pilot C. Christensen less than a half hour into the first dog watch, and he brought the ship to anchor at the mouth of Rich Passage, where she remained as a heavy fog drifted in, lessening visibility to 500 yards. Pilot Christensen returned the next morning and brought Midway to anchor off the Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash., before going ashore. District craft brought ammunition lighters alongside to provide the ship’s commissioning allowance. Before day’s end, Midway proceeded to Illahee, Wash., and the degaussing range there.

Midway depermed on the 17th, then, assisted by the pilots C. Kennan and Lt. Cmdr. Fulmar, completed degaussing operations before anchoring in Port Townsend harbor. She reported for her shakedown that day [17 November 1943]. The new escort carrier then conducted radio direction finder (RDF) calibrations the following morning [18 November], then proceeded to Gunnery Range No. 4 where she commenced a structural firing test a little over an hour into the afternoon watch. At 1428, she fired one 5-inch round, firing to the starboard quarter, after which she suffered a power failure involving gun control, radar, communications, and engine-order telegraph. Shifting steering control to the steering engine room in the interim, the ship regained control at 1436 with restoration of power, enabling steering to be resumed from the pilot house. At 1520, Midway completed her structural firing test without further incident. She then completed another RDF calibration before dropping anchor at Port Townsend.

Standing out the following morning [20 November 1943], Midway proceeded to Seattle, Wash., standing into the harbor at the close of the afternoon watch, mooring alongside Pier 41, U.S. Naval Station, Seattle. Underway for Alameda, Calif., on the afternoon of 22 November, Midway, taken out by Lt. Cmdr. Fulmer, the pilot, stood out of Seattle harbor, steering various courses and speeds to conform to the channel. After stopping to drop the pilot, the escort carrier continued on her coastwise trip, encountering a heavy fog in the first dog watch that day that reduced visibility to only 200 yards and compelled the ship to begin sounding fog signals, which she discontinued when visibility opened to 2,000 yards as the fog lifted. That day, Midway reported unsatisfactory functioning of her evaporators, and requested that a service representative be available about 28 November at San Diego.

Airship K-79 provided escort for Midway into the afternoon watch on the 23rd, during which she was relieved by K-38, which patrolled overhead into the second dog watch. The ship conducted two periods of general quarters practice during the day. K-87 stood watch (0740–1735) as Midway set course for Alameda on 24 November, while the ship carried out more general quarters evolutions, conducted gunnery practice, and completed speed runs.

Picking up her pilot, Lt. Cmdr. G. P. Knight, USCG, during the morning watch on 25 November 1943, Midway soon again encountered heavy fog once she passed Mile Rock, commenced sounding fog signals, then slowed. Passing through the harbor nets at 0747, the ship fouled the port entrance buoy and port gate tender, tearing loose her down-haul paravane and pad eye from the deck, shearing the pelican hook, as well as shearing off a mooring chock from the side of the hull, in addition to receiving a dent in her hull as well as a small hole. She anchored 600 yards off Black Point, San Francisco Harbor ten minutes later, then embarked Capt. C. Rudy, a San Francisco Bar Pilot, who brought Midway safely to the carrier pier at Alameda. Later that day, during a series of inspections, the ship embarked a Lt. Cmdr. Reilly, under whose supervision divers inspected the escort carrier’s propellers for damage.

Over the ensuing days, Midway received lube oil (5,000 gallons) on 26 November 1943, as well as fueled (140,000 gallons), then took on board lubricating oil as well as Navy Special Fuel Oil (NSFO) and 129,238 gallons of 100-octane gasoline (27 November) in addition to aviation lubricating oil. She remained at Alameda until 28 November, when she got underway a little after the mid-point of the first dog watch, at which point she sailed for San Diego, Calif., again encountering heavy fog that closed in almost as soon as she cleared the harbor entrance nets, leading to her sounding her fog signals and showing to 10 knots.

During Midway’s passage the following day, 29 November 1943, the airship K-59 patrolled overhead, as did two Vought OS2U Kingfishers from the inshore patrol. They encountered the heavy cruiser Boston (CA-69) and two destroyers during the early afternoon. Midway exercised at general quarters, then continued on alone from the middle of the second dog watch, alternating, as before, zig-zagging or steering a base course. Eventually she stood in to San Diego Harbor a half hour into the morning watch on the 30th, embarked pilot H. N. Kroc, then passed through the nets, and moored alongside Pier J, NAS North Island, San Diego. That same day, the office of the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet (ComInCh) reassigned Midway from the Atlantic to the Pacific Fleet.

Assigned to work-up under Commander Operational Training Command, Pacific (COTCPac), Midway received the designation Task Unit (TU) 14.5.7. She sailed from North Island on 2 December 1943 for Operational Area II-15 off the coast of southern California, and conducted gunnery exercises and operational training. Joined the following day [3 December] by the motor torpedo boat tender Mobjack (AGP-7) and destroyer Stephen Potter (DD-538), Midway continued training in area II-15, firing more gunnery exercises and conducting other evolutions as part of her shakedown. The carrier then resumed operating singly on 4 December, Area II-3 before mooring to Pier No. 3, U.S. Naval Repair Base, San Diego, later that same day.

Midway remained at the Repair Base until 12 December 1943, undergoing repairs, until she began loading planes and receiving passengers. She stood out of San Diego the following day [13 December], and set course for the Territory of Hawaii. After one day at sea, the escort carrier test-fired her antiaircraft guns, expending 275 rounds of 20-millimeter and 68 of 40-millimeter. Ultimately, Midway stood in to Pearl Harbor on 19 December, mooring to Pier F-13, Ford Island, where she discharged her cargo and disembarked her passengers.

Remaining at F-13, Midway received passengers and cargo on 20 December 1943 and sailed for the West Coast the next day [21 December], escorted for the initial part of the voyage by Sanders (DE-40), setting course to return to San Diego. The ship conducted gunnery exercises “George” and “Charlie Type Tare” that day, her Bofors (40-millimeter) guns firing 624 rounds and her Oerlikons (20-millimeter) 2,160.

Proceeding independently as TU 19.9.7, Midway spent Christmas at sea, and moored at Pier I, NAS San Diego, two days later [27 December 1943], where she disembarked passengers, discharged cargo, and began receiving fuel, completing the latter process the following day. She moved out into the harbor and anchored in Berth 208 on 29 December, her crew beginning the arduous task of removing bombs from their stowage below to the hangar deck, continuing that process the following day. On the last day of the year 1943, as a consequence of her being reassigned from the Atlantic to the Pacific Fleets [30 November], the ship discharged her “East Coast” commissioning allowance of bombs in exchange for the “West Coast” allowance.

New Year’s Day 1944 saw Midway, assigned to Carrier Division (CarDiv) 25 effective 1 January 1944, and still designated as TU 19.9.7, loading a cargo of airplanes while she lay alongside Pier I, NAS North Island. Underway for Alameda on 3 January, the escort carrier dropped anchor in Area 12, San Francisco Bay, the following afternoon, then proceeded on the 5th to Army Pier No. 7, Oakland, Calif., where she began unloading the aircraft she had brought from North Island, an evolution she completed the following day [6 January]. Loading another cargo of planes, Midway fueled ship, then took provisions and ammunition on board, then embarked 163 passengers, getting underway for Australian waters on 7 January.

Proceeding independently, Midway provided a platform for gunnery practice of all calibers while en route “down under,” with training with .45-, .38-, and .22-caliber officers’ firings (8 January 1944), 20-millimeter instructional firing (9–10 January), and both 20- and 40-millimeter target firings (12 January), practices reprised on the 16th. Ten days later [26 January], the escort carrier-cum-transport reached Brisbane, mooring alongside Brett’s Wharf. There, she unloaded, then loaded a shipment of airplanes on the 27th. She shifted berths the next day [28 January], after which she began fueling and disembarked her passengers. After completing fueling, Midway sailed on 29 January for San Diego.

On the return voyage, Midway conducted practice firings of her 40-millimeter battery (619 rounds) and 20-millimeter guns (1,310 rounds), as well as test-fired .30-caliber machine guns (150 rounds) on 1 February 1944, and fired four-rounds of 5-inch/38 the following day (star shells). She fired two test runs of 5-inch/38 on 3 February, five rounds in the first and seven in the second. The homeward-bound escort carrier practice-fired her 40-millimeters on the 4th. She fired once more during the passage from Australia, conducting practice firings of all guns, expending 10-rounds of 5-inch/38, 532 rounds of 40-millimeter and 2,400 of 20-millimeter on the 13th.

Reaching San Diego on the morning of 16 February 1944, Midway moored to Pier K, NAS North Island, then shifted to Pier No. 4, U.S. Naval Repair Base. The following day, she loaded ammunition: 672 rounds of 5-inch, 3,298 rounds of 40-millimeter, 7,440 rounds of 20-millimeter, and 1,350 rounds of .45-caliber, and transferred 271 rounds of 5-inch/38 ashore, to be shipped to the Fall Brooks, Calif., Naval Ammunition Depot. She underwent repairs (17–26 February), and nearly simultaneously loaded stores (19–26 February), at the end of which period she shifted to North Island, mooring at Pier I on the 26th, and received aviation gasoline that day and the next (27 February). After fueling ship on the 27th, Midway got underway the following day [28 February] for the training area to begin carrier qualifications and refresher landings in company with the small seaplane tender Ballard (AVD-10).

Midway, with Ballard plane-guarding, began her training work in Operational Areas DD and FF on 29 February 1944. Qualifying pilots of Composite Squadron (CompRon) 65, she qualified 24 and logged 99 landings on 1 March, with only one minor barrier crash, when an FM-2 engaged wire no. 8 but hit the first barrier. She qualified two pilots the next day [2 March], logging 41 landings with no casualties, and also qualified 31 pilots in 31 catapult launchings. During the day’s operations on the 3rd, she conducted 37 recoveries, during which time an FM-2 nosed over while warming up prior to take-off, the mishap that would necessitate an engine and propeller change. The following day [4 March], Midway logged 30 landings with no casualties, and on the 5th logged 15 landings with only one mishap, when an FM-2 clipped the forward guardrail chain while being parked on the flight deck. During practice firing that day, the ship expended 2,000 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition, then expended 3,500 rounds the next day [6 March]. That same day, she brought her training period to a close with 33 landings and no casualties. Two days later, she launched 17 planes to fly in to North Island, then moored to Pier J at 1648 on 8 May, commencing the process of “fueling ship” soon thereafter, completing it the next day.

Underway at 0741 on 10 March 1944, Midway and the high speed minesweeper Elliot (DMS-4) set course for the familiar waters of areas DD and FF, the carrier having embarked CompRon 4 for their training. Although rough seas prohibited flight operations on the 10th, the weather abated enough to permit Midway to conduct 13 landings – with no casualties – on the 11th. Elliot departed for other duties shortly before the end of the afternoon watch that day, her place taken the next morning [12 March] by the escort vessel Hilbert (DE-742).

Midway logged 40 landings and qualified ten pilots on 12 March 1944, but also experienced her first aircraft loss. Lt. (j.g.) C. H. McClean, A-V(N), USNR, took off in a TBM-1C (BuNo 63967) (carrying the ship’s mail) but in retracting the Avenger’s landing gear “immediately upon becoming airborne” as the bomber gained altitude, over-corrected for the ascent and crashed into the sea. The plane sank in a minute and 10 seconds but Hilbert recovered all hands who had been on board the TBM: McClean, SK3c G. E. Simons, USNR, and AMM2c M. L. Tigner, USNR, returning the latter enlisted man (who had “received a strained back and a mild shock”) to the carrier for medical attention.

Flight operations continued the next day [13 March 1944], with Midway qualifying 14 pilots and logging 49 landings. She catapulted six FM-2s during those evolutions, but one returning Wildcat’s right landing gear collapsed when made a hard landing on board. During the first dog watch, the escort carrier exercised at “torpedo defense,” and test-fired her antiaircraft guns, expending 1,131 rounds of 20-millimeter ammunition and 245 rounds of 40-millimeter. A rough sea prevented flight operations the following morning [14 March], but Midway was able to launch VC-4’s planes early that afternoon to return to North Island, with the escort carrier mooring alongside Pier I at 1732, after which she began unloading bombs and aviation gasoline.

Completing the discharge of aviation gasoline earlier that day, Midway sailed less than a quarter of an hour into the forenoon watch on 18 March 1944, and returned to the Naval Repair Base, San Diego at 0900, mooring alongside Pier No. 4. Workmen soon reported to commence “ship’s work,” and the escort carrier remained at the Repair Base through the first week of April.

Midway returned to Pier I at North Island on the morning of 7 April 1944, where she loaded planes and stores, fueled ship, and received aviation gasoline. Underway the next morning [8 April], she stood out of San Diego and set course for Areas DD and FF. She held degaussing operations, and calibrated her magnetic compass as well as her RDF. Ballard reported for duty as plane guard but reported a mechanical failure and received permission to return to port. The sea proved too rough for flight operations.

The frigate Bisbee (PF-46) reported for duty as plane guard the following day [9 April 1944], and the two ships steamed to Area MM, but a rough sea again prevented flight operations. They proceeded through the waters in MM to those in DD and FF, and the following morning [10 April] commenced qualifying Carrier Air Group (CVG) 21. Midway qualified 10 pilots and logged 27 landings, only one mishap occurring when a Grumman F6F Hellcat damaged its right wheel in a hard landing. Less than a quarter of an hour into the first dog watch, Ballard returned to relieve Bisbee as plane guard for the rest of the day, flight operations being secured at 1841.

Operating once more in Areas FF and DD, Midway experienced a busy day on 11 April 1944, logging 125 landings, but also experienced her first tragedy, when the Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat (BuNo 42159) piloted by Ens. Leonard F. Barry, A-V(N), USNR, went over the side at Frame 104 while attempting a landing. Although Barry had made four take-offs and three normal landings that day, he made a fourth normal landing but – for reasons that would never be known – skidded to the left. The Hellcat, on its unbridled passage over the side, damaged two 20-millimeter guns, tore off a four-foot radio antenna outrigger, bent the splinter shield of a 20-millimeter mount in the gun tub at Frame 108, ripped off the stiffener at Frame 103, bent a support for a gun platform, breaking off the safety releasing arm of life raft no. 20, and bent and ripped the forward stack. The plane sank immediately, plunging into the depths and entombing Ens. Barry, 11 days shy of his 22nd birthday.

The following day [12 April 1944], Midway qualified 9 CVG-21 pilots on landing and 21 pilots in catapult take-offs, and logged 57 landings. During one catapult shot, however, Lt. (j.g.) Cleon M. Arnold, A-V(N), USNR ran up the engine of his F6F-3 (BuNo 42130), prepared to take off, giving the “O.K.” sign just before the tie-down released. The tension ring parted, however, releasing the Hellcat to roll off the bow and into the sea. Fortunately, Arnold was recovered, although he suffered a strained back in the mishap.

Catapulting off nine planes the next day [13 April 1944], Midway returned to San Diego Harbor, anchoring in Berth 208 shortly after noon. She got underway the following afternoon and moored alongside Pier K, North Island, where she fueled ship, disembarked CVG-21, and embarked CompRon 75. In addition, the escort carrier loaded 18 1,000-pound bombs (AP AN-M133), 27 1,000-pound bombs (SAP AN-M59), 72 350-pound depth charges (AN-Mk. 47) and 60 100-pound depth charges (GP AM-M30).

Midway got underway from Pier K at 0650 on 15 April 1944 to return to the familiar waters of Areas DD and FF, once more in company with her plane guard Ballard. The carrier qualified 10 pilots, the day’s landings only featuring one “minor barrier crash which required a propeller change.” Troubles of another nature vexed one of the TBM pilots; a broken oil line caused him to land on San Clemente Island. CompRon 75’s aviators continued their toil the following day [16 April] in Area MM, with the carrier qualifying 19 pilots in landings, and two on the catapult, and only one FM-2 encountered the barrier, requiring an engine and propeller change. Midway operated in Area MM again the following day with Ballard, and the carrier wrapped up her flight operations for the month qualifying 26 pilots on catapult launchings, returning to moor starboard side-to Pier G, North Island.

Midway loaded supplies on 18 April 1944, and the following day received 73,500 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition, and exchanged 50 rounds of 5-inch/38 and a condemned lot of 1,400 rounds of .50-caliber for 1,400 rounds of .50 caliber incendiary service ammunition. That transfer having been taken care of, the escort carrier stirred from Pier G and shifted to Pier K, where she began taking on aviation gasoline and receiving provisions. She loaded planes and cargo the following day, and embarked passengers.

Less than an hour before the end of the forenoon watch on 21 April 1944, Midway got underway from Pier K at 1115, and stood out of San Diego, setting course for Hawaiian waters. K-34 patrolled overhead (1232–1930), then departed, while the escort carrier steamed alone across the Pacific. Midway conducted practice firings of her 40- and 20-millimeter batteries during the passage to Pearl (22–23 April and 25–26 April), with .50-caliber practice on the 26th. Joined by the submarine chaser PC-580, which took station as her escort at 09657 on 27 April, Midway conducted gunnery practice, then stood into Pearl Harbor, mooring starboard side-to Pier F-9, where she disembarked her passengers and unloaded cargo. There, she remained for the rest of April.

Midway remained in Hawaiian waters, preparing for Operation Forager, until sailing for Eniwetok, Marshall Islands, in company with Task Group (TG) 52.1, Rear Adm. Gerald F. Bogan, who wore his flag in Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70). Designated as TU 52.14.4, Midway provided cover for TG 52.15. During her passage to the Marshalls, the carrier conducted practice firings of 20- and 40-millimeter guns (1-3 June and 5 June 1944), but lost one plane in an operational accident off Eniwetok, when Ens. Ray M. Rushing, A-V(N), USNR, made a water landing during qualifications at 0900 on 8 June. While his FM-2 (BuNo 47016) sank, Ross (DD-563), the plane guard, retrieved Rushing uninjured.

A little over three-quarters of an hour into the afternoon watch on 8 June 1944, Midway dropped anchor in Berth 15, Eniwetok Atoll, then shifted to another berth to load provisions, a process she concluded the following day. That afternoon (9 June), she got underway and, after anchoring in Berth 150, fueled ship from the oiler Saranac (AO-74), returning to her original berth (15) shortly before the beginning of the mid watch on the 10th. There she received aviation gasoline, then sailed the following morning, bound for the Marianas, providing air coverage for TG 52.15 as before.

On 14 June 1944, Midway arrived off Saipan and departed TG 52.14, to operate with TG 52.15 for the remainder of the month as Forager proceeded ahead. Midway launched eight FM-2s and four TBM-1Cs, the latter each armed with eight 5-inch rockets and 12 100-pound bombs, to strafe targets ashore in concert with six FM-2s from VC-68 from Fanshaw Bay, eight TBM-1C Avengers from VC-3 in Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) and eight FM-2s from VC-4 in White Plains (CVE-66).

That same day, while on a routine antisubmarine patrol over the carriers off Saipan, Lt. (j.g.) Leonard J. Kash, A-V(N), USNR, flying a VC-65 TBM-1C, noticed a plane turning away from him at a 90-degree angle. Identifying it as a torpedo-carrying Nakajima B5N Type 97 carrier attack bomber [Kanjō Kōgekiki, abbreviated Kankō] the 24-year old Chicagoan gave chase immediately and followed the Kate through the base of a cloud, jettisoning his depth charges to gain more speed, and gradually gained on him. After a chase of several miles, Kash came within range and fired two rockets (which both missed, low). The Japanese pilot jettisoned his torpedo and, his mount thus lightened, pulled ahead. Kash fired his fixed guns, but the starboard gun jammed. He then pulled over to starboard to give GM1c Howard E. Dolliver, USNR, his turret gunner, a chance to engage. The enemy radio-gunner returned fire with five or six rounds before the Kate turned away, climbed into the sun, and broke off the duel.

Midway furnished air coverage for the transport groups off Saipan and participated in strikes on Japanese targets on the island the next day [15 June 1944]. A little over a half an hour into the first dog watch that afternoon, the TBM-1C flown by Lt. Stanley H. Cook, A-V(N), USNR, ditched while in the landing circle. While the Avenger (BuNo 48121) sank, Cassin Young (DD-793) rescued Cook and his passengers uninjured. Still later that same day, Japanese planes attacked the formation but were driven off.

During the second dog watch (1852) on 17 June 1944, a force of Japanese carrier bombers and land attack planes pounced on the disposition, damaging Fanshaw Bay and forcing her departure, as well as compelling Rear Adm. Bogan to shift his flag to White Plains. Midway emerged from the battle unscathed and having sustained neither damage nor injuries, expending 3 rounds of 5-inch/38, 468 rounds of 40-millimeter and 1,740 rounds of 20-millimeter.

In concert with CompRons 3, 4, and 68, VC-65’s pilots engaged the enemy in aerial combat, flying 16 sorties, of which 12 engaged Japanese aircraft. Her FM-2 pilots (all A-V(N), USNR) in the combat air patrol (CAP) claimed three kills: Lt. (j.g.) Charles H. Freer and Lt. (j.g.) Virgil D. Green teamed up to splash a Sally [Mitsubishi Ki-21 Type 97 heavy bomber] during a low-altitude pursuit where the Japanese’ propeller blast left a discernable wake; Lt. (j.g.) John A. Hamman and Ens. Lawrence E. Budnick splashed a Zeke, and Ens. George W. Stroup, Jr. claimed a “probable” Kate. Sadly, Ens. Lloyd F. Woodhouse, S(A1) USNR, an Iowa native who had just celebrated his 25th birthday the day before, failed to return from the mission, and neither he nor his FM-2 (BuNo 47017) were ever seen again. One of the returning FM-2s, damaged in combat with a Zeke, could be repaired on board, but the flight deck crews jettisoned three Wildcats (BuNos 16060, 16205, and 16422) after they had suffered irreparable damage in deck crashes.

On 20 June 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Ralph M. Jones, A-V(N), USNR, commanding officer of VC-65 (recipient of a Navy Cross for his performance of duty during Operation Torch in 1942), led a bombing and strafing mission against targets on Saipan, leading four TBM-1C’s from his own squadron, each carrying eight 100-pounders and eight 5-inch high explosive rocket projectiles, and five from White Plains’ VC-4 that carried identical ordnance loads. Midway’s planes attacked two barracks and smaller buildings, three pillboxes, two large gun positions and three trucks on the north side of Magicienne Bay, with Lt. Cmdr. Jones serving as air coordinator. Lt. (j.g.) Edwin C. Callan, A-V (N) USNR, of VC-65 carried out several runs, scoring a direct hit on a barracks that immediately caught fire and burned to the ground. That same day, Corregidor (CVE-58) and Coral Sea (CVE-57) assumed stations in the task group, replacing Fanshaw Bay that had left on 17 June and Kalinin Bay that had departed the previous day [19 June].

The coming and goings of other escort aircraft carriers in the disposition changed again on 21 June 1944, with Suwannee (CVE-27) and Sangamon (CVE-26) relieving Coral Sea and Corregidor on station, with Suwannee and Sangamon departing without relief on the 22nd. On the latter date, Midway fueled ship from Pecos (AO-65), while the carrier’s CAP intercepted four inbound Jills 40 miles southwest of Saipan, Lt. Christopher K. Maino, A-V(N), USNR, splashing one and Ens. B. P. Yokes, A-V(N), USNR, a second; Lt. Cmdr. Jones, while air coordinator over Saipan, expended two 500-pound bombs and eight rockets on three targets, destroying a small locomotive near Marpi Point, decimating Japanese troops some 1,200 yards southeast of Kalapara Pass, and devastating piles of supplies evidently moved in in the night before, neat Cha Cha Village, Jones lacing the last-named target with .50-caliber machine gun fire and rockets.

Midway’s VC-65 continued to carry out bomb and rocket strikes ashore on almost a daily basis for the remainder of June 1944 and into July. The formation underwent an air attack on 26 June, but the screening ships shot down the plane some two miles away, which dispersed the raid without damage or casualties. Suwannee returned to the disposition on the 27th, departing the following day, with Gambier Bay (CVE-73) replacing her later that same day. White Plains departed the disposition on the last day of June, with Midway’s Capt. McKenna becoming commander of TU 15.4.4.

Midway replenished ammunition at Saipan on 1 July 1944, anchoring at 0630 and sailing at 1606, taking her station in her task group early in the second dog watch. Nehenta Bay (CVE-74) joined the disposition the next day [2 July], while Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay departed. Midway’s air crew took part in strikes against Japanese targets on Saipan as well as carried out antisubmarine patrols. They expended 1,400 pounds of bombs, 1,530 rounds of .50-caliber, as well as 300 rounds of .30-caliber, operating from the ship as she maneuvered in the waters to the east of Saipan.

The following day [3 July 1944], Commander Support Aircraft reported Japanese guns of various calibers and sizes emplaced in Kalopera Pass about 3,000 yards north of Mt. Tapotchau, holding up the advance of U.S. ground troops. CompRon 65 put eleven planes in the air, eight FM-2s and three TBM-1Cs (the latter each carrying two 500-pound bombs and eight 5-inch high explosive rockets) taking off from Midway, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Jones. Two FM-2s strafed the guns to lead off the attack, after which the three Avengers, with a pair of Wildcats on each beam to keep the Japanese antiaircraft gunners’ heads down, loosed their six 500-pounders (two scored direct hits and the other four exploded in proximity), with Lt. (j.g.) Gerald S. Huestis, A-V(N), USNR, on his second run, salvoing his rocket projectiles directly into a gun position and knocking it out. A short-circuited junction box in the third TBM, however, did not allow its rockets to be employed, forcing its pilot to salvo them into the area, a procedure that did not enable accurate assessment of results. In reflecting upon the mission, one observer reported the operation as “completely successful,” with ground forces “mov[ing] into and captur[ing] the area after the air attack was completed.”

While the employment of fighters to protect for the bombers had been routine, “the way they [the FM-2s] were used appears worthy of comment.” Reports had told of medium to heavy Japanese fire in the area attacked, with the enemy’s procedure “to withhold fire until the aircraft could no longer see the ground below or behind. Consequently, planes were being hit from below and from the rear...Standard practice had been for the fighters to strafe in column ahead of the bombers.” Ralph Jones, CompRon 65’s commanding officer, however, “tried out a new plan,” deploying four FM-2s ahead of the TBMs, the Wildcats firing long bursts that forced the Japanese gunners to “hole up.” The last division of two Wildcats fired only at active guns, while the last section of two FM-2s retired 90 degrees from the pull-out direction of the TBMs, employing “violent evasive action” and drawing Japanese fire away from the Avengers. Jones’s new plan “worked effectively in this instance,” an observer wrote, “as no planes were hit by [antiaircraft fire].”

A little over halfway through the afternoon watch that same day [3 July 1944], Midway again went to flight quarters, launching eight FM-2s and three TBM-1Cs, the latter each carrying eight 100-pound bombs and eight 5-inch rockets. With Japanese troops reported 1,200 yards ahead of U.S. forces a mile north of Flores Point, Lt. Cmdr. Jones received orders “to attack enemy personnel, trenches, small gun positions and various buildings capable of affording cover in that area.” Consequently, the eight Wildcats deployed in column and carried out a strafing attack, after which the three Avengers strafed the area and carried out three bombing runs, putting all of their ordnance in the zone, setting fire “to at least one building, which appeared to be a small railroad depot.” The pilots also reported putting several of their bombs in the trenches and among the Japanese troops, but could not accurately assess the results of their attack.

Once they had finished their strafing runs, the FM-2s orbited the area. Spotting a Japanese medium tank, they attacked with their .50 calibers. As he pulled out of his run, Lt. Floyd A. Johnston, Jr., A-V(N), leader of the second division of fighters, spotted a second tank and promptly informed the TBM pilots. The Avengers scored near-misses with eight rocket projectiles, the pilots believing the exploding ordnance gave the Japanese tankers concussions and “putting them at least temporarily out of action, if nothing more.” Johnston’s alertness and skillful attack enabled the U.S. ground forces in the vicinity to resume their advance, and he later received an Air Medal for his “meritorious achievement.”

The low level runs against the armored vehicles, however, yielded the discovery of what appeared to be a “large supply dump…[with] boxes and crates and several trucks…partially hidden under a large clump of trees.” VC-65’s pilots all carried out heavy strafing runs on “these fine targets” while the Avengers fired 16 5-inch rockets into the storage area, setting fire to and destroying one large truck. “Tracers and rockets started many fires,” VC-65 reported, “with one large fire bursting over 200 feet in [the] air. From the suddenness with which this fire exploded it was believed to be gasoline.” Heavy smoke and dust stirred up by the unexpected destruction visited upon the area prevented any “detailed damage assessment,” but Midway’s airmen believed that they had “unquestionably damaged” the area with their “strong attacks.” After two hours in the air, VC-65 returned to the ship having suffered neither loss nor damage as in their earlier strike.

For the next five days (4–8 July 1944), Midway put up strikes each day, fielding various numbers of Wildcats (never less than eight per mission) and Avengers (never less than three but, in one instance, on 8 July, as many as eight). CompRon 65 expended at least 14,400 pounds of bombs, 9,150 rounds of .50-caliber, 450 rounds of .30-caliber, and 144 5-inch rocket projectiles. At the end of that period (8 July), Midway fueled and received aviation gasoline from the oiler Sabine (AO-25).

Less than an hour into the first dog watch on 9 July 1944, White Plains (flagship for ComCarDiv 25), along with Kalinin Bay and destroyers Irwin (DD-794), Cassin Young, and Ross (DD-563) departed the formation. Midway formed TU 52.14.4, her Capt. McKenna in command, and expended 225 rounds of .50-caliber in drills on the 9th and 420 on the 12th.

Midway departed the waters east of Saipan about the middle of the second dog watch on 13 July 1944, and set course for the Marshall Islands for replenishment. She expended 300 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition during exercises the following day and reached Eniwetok late on the afternoon of the 16th. There she loaded ammunition, aviation stores, fueled ship, and received aviation gasoline the following day, and sailed late on the afternoon of 18 July, bound for the Marianas as part of TG 53.19, Capt. Herbert B. Knowles, commanding, in the attack transport Monrovia (APA-31).

Midway provided air coverage as well as antisubmarine patrol, expending 150 rounds of .50-caliber during machine gun test firings. Detached from the task group a little over an hour into the morning watch on 22 July 1944, Midway took departure from Guam as TU 53.19.5 (Capt. McKenna) and set course for Saipan. Nehenta Bay and the destroyers Longshaw (DD-559), Alfred A. Cunningham (DD-752), and Mertz (DD-692) departed the disposition during the morning watch (0520) the following day (23 July), while White Plains and destroyers Porterfield (DD-682), Irwin, Ross, and Callaghan (DD-792) joined 20 minutes later (0540). Midway began providing air support over Tinian and continued providing antisubmarine patrols.

An hour into the afternoon watch on 24 July 1944, Rear Adm. Clifton A. F. Sprague, his flag in White Plains, assumed tactical command of TU 52.14.2 operating in the waters east of Saipan. Midway turned into the wind in the middle of the forenoon watch and launched 11 TBM-1Cs and 14 FM-2s for the 30-mile flight to hit targets on southern Tinian, the strike under Lt. Cmdr. Jones.

On that bright sunny afternoon, Midway’s pilots and aircrew hit a group of four 3- to 5-inch guns emplaced in an open field surrounded by machine guns and antiaircraft guns located at the foot of the eastern slope of a ridge on the southern end of Tinian, 2,350 yards to the west northwest of Marpi Point. Descending from 1,000 feet, the five TBM-1Cs assigned to the task put 39 of their 40 100-pounders onto the target, then returned to make rocket runs, putting 36 of their 40 5-inch projectiles into the target area, knocking one of the four guns out of action and severely damaging the second.

CompRon 65’s second target that day, a trio of guns appearing to be of 3-inch (or smaller) caliber, lay to the east side of the ridge where the first emplacements had been located, about 3,000 yards east southeast of Tinian Town. The first plane “made a perfect hit in the center of the position,” but the 500-pounder turned out to be a “dud.” Six other bombs hit among the three positions, one exploding “directly under the mouth of one gun,” with the air coordinator assessing one weapon knocked out with “undetermined” damage to a second.

One VC-65 TBM pilot made two passes on a gasoline dump – partially camouflaged and hidden under trees -- 600 yards east of the southern end of Tinian Town, and obtained direct hits with his 5-inch rocket projectiles, starting a large fire. Fighter pilots returning from this area later told of the fire still blazing and spreading over a greater area than at the start. “The fire was either uncontrollable,” an observer wrote, “or at least no noticeable effort was made to put it out.” A second TBM pilot made two runs on a railroad car parked on a siding, loosing two 5-inch rockets on each pass, the blast effect of the projectiles holing the enemy rolling stock.

Tragically, one of the Avengers (BuNo 25559) assigned to the second objective never reached the target, when Lt. Stan Cook’s bombs, due to a malfunctioning fuse (each 500-pounder had an instantaneous nose fuse and a 4/5-second delay tail fuse), exploded, flames seen to shoot out of the TBM’s after fuselage and tail. Neither Cook, a Hofstra graduate (Class of 1939) who had just turned 27 less than a fortnight before, nor his crew survived the blast in the bomb bay, the mishap also snuffing out the lives of AMM1c Eugene W. Zepht (who had participated in the attack on the Vichy French battleship Jean Bart at Casablanca in November 1942) and AMM3c Thaddeus Soja, the latter having been temporarily assigned to VC-65 from Midway’s ship’s company on 20 July.

The following day [25 July 1944], Midway reprised her activities from the waters east of Saipan, her air department putting aloft 11 TBM-1Cs beginning at 0920, during the forenoon watch, accompanied by 15 FM-2s, Lt. Cmdr. Jones again leading the strike against Japanese positions on the southern end of Tinian. The mixed ordnance load for the Avengers included two planes with a pair of 500-pounders (instantaneous nose fuses and 4/5 second delay tail fuses), five each carrying eight 100-pounders and two with four depth bombs. Each TBM carried eight rockets. All planes attacked a large wooded area “with considerable track activity leading into it,” near which a truck could be seen parked with “numerous dark objects that appeared to be ammunition boxes or other supplies” in proximity, 2,490 yards north of Tinian Town.

Releasing their ordnance from between 500 and 800 foot altitude, CompRon 65 dropped their bombs squarely on target, as well as unleashed 88 rockets on it as well, but the trees obscured what damage may have been inflicted. The Wildcat pilots strafed the area, starting several fires, then twice attacked three railroad cars on a siding 2,920 yards north of Tinian Town, their strafing setting fire to sugar cane fields that lay beside the railroad tracks. The burning cane, together with tracers fired by the FM-2s, in turn set the rolling stock afire. Subsequent reports noted that the cars continued to burn. All of Midway’s planes began returning ten minutes into the afternoon watch.

CompRon 65’s pilots and aircrew returned to the fray the next morning, Midway launching 27 sorties – 11 TBM-1Cs and 15 FM-2s – beginning at 0837 on 26 July 1944. Preceded by strafing Wildcats, four Avengers each dropped eight 100-pounders in train and fired eight rockets into the area where Japanese troops had been reported in a heavily wooded area on Tinian’s northeastern coast, although the heavy foliage prevented any damage assessment. Two Avengers dropped four 500-pounders and rocketed a series of cave entrances and piles of stores at the foot on a cliff located 225 southwest of the airstrip at Ourgan Point, starting small fires in the area. Four FM-2s each fired short bursts as they strafed antiaircraft guns at the end of the pier that jutted out into the water just south of the Tinian Town sugar plant, observers noting with satisfaction that “the gun which had previously holed a TBM-1C did not fire after the VF attack.” Additionally, another quartet of Wildcats, each employing short bursts of .50-caliber machine gun fire, destroyed a searchlight position 4,100 yards north of Tinian Town. One Avenger returned to the ship damaged -- its port wing had been holed by antiaircraft fire -- but men on board the carrier restored the plane to operational status. That day the squadron had expended 11,060 rounds of .50-caliber and 430 rounds of .30-caliber as well as 82 rockets.

The operation schedule the following day (27 July 1944), found Midway’s fliers and aircrewmen expending 8,000 pounds of bombs, 11,960 rounds of .50-caliber and 625 rounds of .30-caliber, while a reduced schedule saw CompRon 65 expending 2,800 pounds of bombs and 15 rockets on the 28th, the ship fueling and receiving aviation gasoline from Marias (AO-57) during the forenoon watch.

Anchored in Saipan harbor on 29 July 1944, Midway embarked Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, who transferred his flag to the ship. Later that same day (1539), the warship got underway for the Marshall Islands in accordance with a Commander Task Force 51 despatch (282354), but returned at 1715. She dropped anchor at 1746, bad weather having prevented her from recovering her planes. She got underway the following morning [30 July] in company with TU 51.18.5 and set course once more for the Marshalls.

Ultimately, Capt. McKenna received the Bronze Star for his “meritorious achievement” as Midway’s commanding officer during the operations in the southern Marianas (14 June to 1 August 1944). “He at all times provided the maximum fighting strength of his ship against the enemy,” and his shiphandling had reflected his “cool and capable” direction of the escort carrier as she participated in repelling Japanese air attacks. The citation lauded his “professional skill and courage” that “contributed in large measure to the success of the assault operations.”

Midway anchored in Berth J6, Eniwetok Atoll, at 1635 on 2 August 1944. She received aviation stores on the 3rd, then shifted berths ten minutes into the forenoon watch (0810) on the 4th, anchoring in Berth 396, where she started engine repairs. While that work proceeded, she loaded provisions and 550 aircraft rockets on 5 August, and two days later [7 August], received 180,609 gallons of NSFO, 18,120 gallons of 100 octane aviation gasoline, and 1,790 gallons of diesel oil.

Her engine repairs completed on 8 August 1944, Midway got underway at 0610 on 9 August in company with TU 57.19.5, Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague commanding, his flag in Sangamon. The task unit set course for the Admiralty Islands, the ships in cruising disposition 5LS. The formation held target practice on towed sleeves, with Midway expending six rounds of 5-inch/38 from her stern gun, 720 rounds of 40-millimeter, and 2,100 rounds of 20-millimeter.

Midway reached Seeadler Harbor, Manus, late on the morning of 13 August 1944, and during the first watch began fueling. She completed that necessary evolution a little over half-way through the mid watch on the 14th, having received 159,222 gallons of NSFO and 25 barrels of aviation lubrication oil. She loaded stores, and began further engine repairs. While that latter work continued over the next three days, she received the life blood of her brood of Wildcats and Avengers, 7,780 gallons of aviation gasoline, between 0825 and 0925 on 15 August; loaded 160 100-pound GP AN-M30 bombs (1120–1155 on 16 August), and loaded 150 100-pound GP bombs, as well as five 500-pound AP bombs and 155 AN-M100 A1 fuses with vanes. After her engineers adjudged the engine repairs completed (17 August), the loading of ammunition from the Naval Ammunition Depot, Manus Island, continued, with the ship loading and stowing 24 500-pound SAP bombs on the 18th. More supplies came on board from diverse locations for her busy crew to strike below: 8,000 cartridges for Type B starters from an aviation supply depot (20 August) and 104 5-inch high explosive rocket heads and 80 Mk. 7 rocket motors from the Lockheed PV-1 Ventura-equipped Patrol Bombing Squadron (VPB) 146.

Underway at 0715 for training with CarDiv 22, Midway stood out of Manus harbor on 29 August 1944 in disposition 5R with CarDiv 22 and Fanshaw Bay. A little less than three hours later, Midway began taking on board 11 fighters and nine torpedo planes, completing the landing evolution inside of a half hour. She then launched her small brood a little over an hour into the afternoon watch (1311), then exercised at torpedo defense (1345), after which she conducted gunnery exercises, expending ten rounds of 5-inch/38, 1,289 rounds of 40-millimeter, and 2,460 of 20-millimeter (1405-1530). Subsequently, she reformed in disposition 5R and set course for Seeadler Harbor, dropping anchor in Berth 114, where she remained for the rest of the month of August. She received 9,000 Type B starter cartridges from Fanshaw Bay to round out that period.

Midway remained anchored in Berth 114 at the beginning of September 1944, receiving stores and provisions on the 3rd. The next morning at 0635 she got underway for the operating areas north of Manus, her landing signal officer guiding Lt. Cmdr. Jones and the 15 Wildcats and 12 Avengers on board from CompRon 65 starting at 0910. The evolution completed inside of two hours’ time, Midway set course to return to Berth 114 at 1134, and dropped anchor a little over an hour into the afternoon watch on 4 September. The fuel oil barge YO-8 transferred 2,404 barrels of NSFO to the carrier the next day [5 September].

The following day [6 September 1944] found Midway assigned to CarDiv 25 (less Kalinin Bay and White Plains) in accordance with Commander Seventh Fleet operation Order 10-44, the unit designated as TU 77.1.2 (Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, flag in Fanshaw Bay), a part of TG 77.1 (Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague, Commander CarDiv 22 in Sangamon. They in turn formed part of TF 77, Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey in the amphibious force flagship Wasatch (AGC-9), all operating under Allied Force Operating Plan 10-44 and Seventh Fleet Operating Plan 8-44. Consequently, TG 77 sailed from Manus on 10 September, setting course for Morotai, with Midway weighing anchor and getting underway at 1134. Poor visibility, however, compelled her to drop anchor at 1159. The delay proved only a temporary one, for a little over a quarter of an hour later, as visibility improved, and she sailed at 1216. During parts of the afternoon watch and dog watch (1509–1625), her main and secondary batteries carried out scheduled gunnery exercises, expending 12 rounds of 5-inch/38, 1,076 rounds of 40-millimeter, and 4,320 rounds of 20-millimeter.

The passage toward Morotai proceeded uneventfully over the next few days, with Midway and Fanshaw Bay departing TG 77.1 just after the mid-point of the forenoon watch on 13 September 1944 to carry out flight operations. At noon, TG 77.1 joined the formation of TF 77, and three quarters of an hour into the second dog watch [1845], Midway and Fanshaw Bay rejoined the TG 77.1 formation in cruising disposition Charlie 2. An hour before the end of the first watch on 14 September, Midway took departure from TF 77 in accordance with a visual despatch (140647) from Commander TG 77.1 to TG 77.1.

Operation Trade Wind began on 15 September 1944, when TF 77 (Rear Adm. Barbey) put ashore the troops of the U.S. Army’s 41st Infantry (Reinforced) (Maj. Gen. John C. Persons, commanding) to secure Morotai and build airfield facilities there to support the projected recapture of the Philippine Islands. Midway, as one of the six escort carriers providing close air support, turned into the wind and began launch at 0514, putting four TBM-1Cs, each carrying 10 100-pound bombs (with instantaneous fuses) and eight rocket projectiles, into the air within nine minutes, to be followed by twelve FM-2s. The catapult harness broke, however, imposing a seven-minute delay on the launch, after which the dozen Wildcats, each carrying two wing tanks to extend their range, wobbled aloft inside a minute shy of a quarter of an hour. While the TBMs proceeded on the mission, their radiomen, utilizing the Avengers’ radar, kept their pilots informed as to the position of the force and the distance from the planes. Of the FM-2s that had had the delayed launch, only two pilots experienced difficulty, eventually joining up when light conditions permitted. One observer later commented: “Pre-dawn take-off and rendezvous worked out quite satisfactorily as far as this squadron and ship were concerned. As each plane was joined by the next he turned off his lights leaving but one plane with lights on at one time… if all planes had kept their lights on [a] complete rendezvous would have been made.”

CompRon 65’s Wildcats proceeded to their assigned combat air patrol station, while the TBMs flew to their designated sector, soon receiving orders from Commander Support Aircraft to fly to Gotelamo Village in company with four TBM-1Cs from Fanshaw Bay’s VC-66 and seven F6Fs from Sangamon’s VF-60 (each of the latter carrying a single 500-pound bomb). Encountering neither antiaircraft fire nor Japanese planes, Lt. Cmdr. Jones’ group carried out a “very careful bombing attack,” expending seven 500-pounders, 80 100-pounders, and 64 rockets. After the first bombs landed on target, smoke, dust, and debris obscured the area. Although those conditions may have occasioned misses by two of the Hellcats and one of the TBMs (six of eight bombs landed short of the target), “all other bombs and rockets landed well within the area and the village was very heavily damaged,” with a third of the lightly-constructed buildings completely demolished, a third heavily damaged, and the rest hit by machine gun fire (the Hellcats had carried out two strafing runs once the bombing attack had finished) and had been “seriously affected by bomb blast.” Lt. Cmdr. Jones flew over the area once the smoke had cleared and assessed the damage; all planes returned safely.

For the second day in a row, Midway launched her planes before dawn, beginning at 0514 on 16 September 1944 (four TBM-1Cs, each carrying 10 100-pound bombs in their bomb bays and four rockets beneath each wing, and 12 FM-2s) inside of 21 minutes. Unlike the previous day, where darkening each plane hindered the rendezvous, each aircraft on the 16th kept its running lights on, facilitating the joining-up and reducing the “confusion attendant to night operations.”

The four Avengers then proceeded to the orbit area south of Morotai, joining four TBM-1Cs from Fanshaw Bay and one TBM-1C from Sangamon’s Torpedo Squadron (VT) 60 carrying the air coordinator. After orbiting from 0600 to 0800, the nine-plane formation was completing a turn at 5,000 feet about 2,000 yards from the east coast of the southern tip of the island, when antiaircraft fire began to speckle the sky. Three of Midway’s four Avengers immediately took hits: a 20- or 40-millimeter shell exploded on contact and holed one TBM’s port aileron, a 20-millimeter shell hit the second plane in the port stub wing (but fortunately proved to be a dud) and another 20-millimeter shell hit the leading edge of the third TBM two-thirds the length of the port wing. The radioman in the third aircraft immediately looked down and saw what seemed to be a cruiser and a transport below “with smoke in their immediate vicinity. No enemy guns had been located or were known to be on the southern tip of Morotai,” an observer later wrote, “and it is believed that the fire came from those two friendly ships.” Sadly, Commander Support Aircraft did not have a target for the group, and they returned to their carriers without further incident, with sailors on board Midway repairing all three of the damaged TBMs that had been damaged by what would later come to be known as “friendly fire.”

Nine of Midway’s fighters, meanwhile, completed the rendezvous, with the other three joining up a few minutes later, and three divisions reported being on station about 0600. They orbited the base at 10,000 feet until 0715, when Lt. (j.g.) John Hamman – who had shared a “kill” of a Kate three months before – discerned a Japanese fighter flying from port to starboard of the formation, 6,000 feet below, heading for the transport area off Red Beach. He tally-ho’d the enemy’s presence. Unfortunately, his division leader did not hear his report, although Lt. (j.g.) Harold L. A. Ciborowski, A-V(N), USNR, leading the third division of FM-2s, did. The Japanese pilot had apparently made a very low approach to evade detection on radar and thus avoid being identified as a bogey.

Ciborowski led his division down to execute a high side pass on the plane that he identified as most likely a Hamp (Mitsubishi A6M3 Type 0 carrier fighter). The FM-2 pilots carried out a coordinated attack, getting in “one or two very short bursts” on the snooper, but none of Ciborowski’s squadron mates claimed any damage to their nimble adversary, whose “primary evasive maneuver was an extremely tight turn at such high speed that he left a vapor trail at an altitude of only 4,000 feet.” The FM-2s, carrying wing tanks, could not stay with the enemy in those turns.

Ens. Ray Rushing, in the number four position, fired a quick burst at the Hamp as it headed towards him at a lower altitude, but as Rushing began to roll with the enemy he saw another Wildcat maneuvering onto the Japanese’ tail. Wanting to give the other U.S. pilot “a better position to make the run,” Rushing immediately broke off the pursuit. Lt. (j.g.) Ciborowski tried to carry out a second attack, an overhead pass, but antiaircraft fire from the ships in the transport area began to burst in black puffs in the sky, compelling his withdrawal from what was clearly becoming a danger area. As he did so, Ciborowski saw planes from CompRon 66, from Fanshaw Bay, engage the snooper, with one of the FM-2s making an overhead pass and not recovering from it, then splashed in the water below. Another VC-66 Wildcat, however, then finally splashed the Hamp. Midway’s pilots remained aloft on combat air patrol, being vectored toward many bogeys during that time but, as they noted, “none were seen.” Relieved on station, the CompRon 65’s Wildcats returned to the ship.

Midway’s pilots returned to the fray on the 18th, contributing four TBM-1Cs (each carrying 10 100-pounders with instantaneous fuses, and eight high explosive rocket projectiles) to a strike on Japanese targets near the Pitoe Airstrip on Morotai. Midway launched the quartet of Avengers starting at 0645, and they carried out their glide bombing runs, dropping five bombs per run; other planes taking part included four TBM-1Cs from VT-27 (from Chenango) and four from VT-60 (from Sangamon). “Targets consisted of foxholes, buildings, and other installations, located approximately two miles northeast of Pitoe Airstrip,” Lt. Cmdr. Jones later reported, “Very dense foliage covered the target area which made definite identifications of the buildings difficult.” His planes made four runs, expending all bombs (dropping them at 100-foot intervals from 1,500 feet) and all rockets but one (a material failure occurring with 3.25-inch Rocket Motor Mk.VII not igniting when properly fired), all landing within the target area. “Proper assessment of the damage,” Jones wrote, “could not be determined due to the thick growth of trees and vegetation surrounding the target. No fires were started nor were any other indications of amount of damage observed.”

Going to flight quarters the following morning [19 September 1944] Midway turned into the wind and launched four Avengers (carrying 100-pound bombs and 5-inch rockets) to take part in a strike on the Galela Airstrip on Halmahera Island, joining three TBM-1Cs from Fanshaw Bay’s VC-66, eight FM-2s from Santee’s VF-26, four Hellcats from Sangamon’s VF-37 and three F6Fs from Suwannee’s VF-60. Targets assigned by Commander Support Air consisted of a group of small lightly constructed buildings, as well as revetments and dispersal areas adjacent to No.1 airstrip at Galela. All bombs and rockets landed well within the specified areas, each plane making one run. As on the previous day, the heavy foliage prevented an accurate assessment of damage, but in one instance even a target “expertly hidden under a clump of trees” could not escape notice. Lt. (j.g.) Leonard E. Waldrop, A-V(N), USNR, discovered a Kate and made a run, firing two rockets that transformed the Kankō into junk.

Upon return to the ship, two of the four Avengers opened their bomb bay doors, and 100-pound bombs dropped free onto the flight deck but, fortunately, did not explode. Their pilots had pushed over into steep dives when attacking the Galela Airstrip and the ordnance had hung up on the Mk. IV shackle, riding forward in the dive thus locking the bomb release hooks in a partially open condition. “The shackles,” an observer of the incident wrote, “will be modified at the earliest opportunity” so that the “sleeve jacket [will be installed] over the leading edge of the shackle hook’s slot.”

Midway again went to flight quarters on the 19th, shortly past the mid-point of the afternoon watch, when she launched eight FM-2s to strafe the Oba and Miti Airstrips on Halmahera Island. They joined four Hellcats each from VF-27 (Chenango) and VF-60 (Suwannee) in the 60-mile flight to the objective through clear skies with unlimited visibility. Targets at the Oba strip consisted of “supply dumps hidden under trees and a number of small buildings of light construction…either barracks or small supply houses.” Midway’s Wildcats carried out three strafing runs, but as previous occasions had demonstrated, the “thick growth of trees surrounding the target” did not permit accurate damage assessment, but the strafing neither started fires nor seemed to inflict “any other indications of amount of damage…” At Miti, however, the FM-2 pilots discovered between 30 and 40 Kawasaki Ki-61 Type 3 fighter Hien [Tony] in a dispersal area in revetments beneath trees, “a great majority” of the planes appearing to have been holed and set afire in previous raids but “the remaining planes looked to be completely operational.” With the latter in mind, the eight Wildcat pilots carried out four runs apiece “with each pilot picking out his own target,” an observer estimating “three…destroyed and three…probably destroyed.” In all, CompRon 65’s fighter pilots had expended 8,000 rounds of .50-caliber on the two targets.

A little over a half an hour past the start of the afternoon watch on 23 September 1944, Midway departed TU 77.1.1 in company with TU 77.1.2. Steaming at 15 knots, she set course for Mios Woendi Island to fuel ship, and assumed station no. 2 in disposition 5R. Her planes conducted antisubmarine patrols the next day [24 September], then shortly after the start of the forenoon watch on 25 September, she stood into Mios Woendi Harbor taking station astern of Fanshaw Bay, and anchored at 0955 in Berth No. 25. There, she received 51, 350 gallons of aviation gasoline from the gasoline tanker Susquehanna (AOG-5), and 456,840 gallons of NSFO from Victoria (AO-46). The next day, to complete the replenishment process, she received 210 100-pound GP bombs, 175 AN-M 100-A2 fuses, and 25 AN-M-101-A2 fuses from the Naval Ammunition Depot, Woendi Island. Midway sailed at 0540 on 26 September to return to Morotai, in company with TU 77.1.2, steaming in disposition 5R at 15 knots, the task unit commander (Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague) wearing his flag as Commander TU 77.1.2 in Fanshaw Bay, in company with Harrison (DD-573) and John Rodgers (DD-574). En route back to Morotai, passing south of Biak, Midway provided antisubmarine patrols.

Sighting Morotai late in the afternoon watch on 27 September 1944 [1520], Midway assumed station at 1633 with TU 77.1.1 (less Suwannee and Chenango) in disposition 5-R. Sangamon and Santee departed that formation at the end of the first dog watch. The next day [28 September], Midway resumed providing air support for Trade Wind, two and a half hours into the afternoon watch, putting aloft four TBM-1Cs and a like number of FM-2s, the former each armed with two 500-pounders and eight rockets.

Intelligence information having been received of Japanese activity in staging planes in the area of Davao, Philippine Islands, for potential employment against Morotai or Palau Island, Midway’s eight planes headed for Miti airstrip on Halmahera Island, to render it unserviceable, paying a return call on the field they had last visited on 19 September 1944. The four Wildcats strafed the airfield, after which the TBMs pushed over into glide-bombing runs, making two passes each, with at least two of their eight bombs cratering the center of the 4,500 by 450-foot strip and the remainder hitting elsewhere on the field. When a light antiaircraft gun on the northeastern edge of the strip took Lt. (j.g.) Robert W. Wrinch, A-V(N), USNR, under fire, the 22-year old Minnesotan banked his Avenger around and made a run on the emplacement, firing two rockets. While he inflicted slight damage it proved sufficient enough to force the gunners to stop firing.

After providing close air support and air cover for the transports for the remainder of the month of September 1944, Midway continued to operate off Morotai into October, continuing to serve with TU 77.1.2 alongside her sister ship Fanshaw Bay, screened by the escort vessels Eversole (DE-404), Richard M. Rowell (DE-403), Edmonds (DE-406) and Shelton (DE-407). During the afternoon watch on 2 October 1944, Midway once more turned into the wind to put a strike aloft – four TBM-1Cs, two carrying a pair of 500-pounders and two carrying 10 100-pounders, and 2 FM-2s. Reports of a “possible torpedo launcher” near 01°57'N and 127°51'E, an area north of the town of Galela, on Halmahera Island, had prompted the mission, in which two FM-2s from Fanshaw Bay participated.

The attack group searched the area after its arrival; a close study of photographs disclosed only two locations, but the flight leader reported that he did not “see any position that was suitable for such an installation.” Commander TU 77.1.2 instructed them to bomb an area a half-mile north of Galela town and the Avengers dropped five 500-pounders and 10 100-pounders. An area one and a half miles north of Galela came in for three 500-pound bombs and seven 100-pounders, although three of a string of five bombs blasted the beach lying just outside the target area. The TBMs fired 28 rockets at the second objective, hitting several lightly constructed buildings – previous strikes had inflicted damage to the town, making it difficult to assess the effects of the pilots’ efforts.

At least two 20 [25]-millimeter antiaircraft guns fired on the group, the rate of fire and tracers indicating that it was possibly a multiple mount. One of Midway’s FM-2s took hits that holed the starboard wing, severing the aileron controls. Lt. Joseph T. Riley, A-V(N), USNR, 26, who had served in heavy cruiser Portland (CA-33) as a spare pilot during the Battle of Midway, fresh out of flight school, made a safe emergency landing on the partially completed strip at Morotai. Fortunately, Riley, who hailed from Bethlehem, Penn., received a special air drop of necessary parts the next morning and fixed the damage himself.

On her last day in support of the Morotai operation [3 October 1944], Midway, “operating as before,” launched nine planes for TASP and LASP beginning at 0527. At the start of the forenoon watch, the carrier steamed on base course 270°T, shifting to 255°T to follow zig zag plan no.25 at 14.2 knots. With the wind from south by west, those topside noted the swells from the southwest and the wind at force 25 knots; watchstanders reported visibility at 12 to 20 miles. The circular formation (cruising disposition 5R) found the carriers in the center (Midway astern of Fanshaw Bay) and the four escort vessels arrayed 30° either side of the base course (283°) and 60° from each other.

Five minutes into the forenoon watch [0805], lookouts on board Midway noted two torpedo wakes, about 100 feet between them, 100 yards ahead of the ship, just off the starboard bow, the origin of the wakes being followed to roughly northeast by ½ north (040°T); 5,000 yards along the track, observers discerned a disturbance in the water. While the rough sea and the distance militated against affirming the definite presence of a periscope, an observer wrote later that “the disturbance in the sea was observed to disappear in the manner of a submarine periscope.”

With the torpedo having passed well clear of flagship Fanshaw Bay and “relatively close aboard” Midway, the latter immediately transmitted a warning to the task unit commander (TU 77.1.2), Rear Adm. Sprague, and escort vessel Shelton, as reflected in the carrier’s TBS log:

0805:00 Knuckle Two (CTU 77.l.2) This is Derby (Midway) – Torpedo wakes we are paralleling.

0805:15 Trolley (Shelton, DE 407) Do you see those torpedo wakes.

0805:45 Derby from Knuckle Two – Roger we do not see them.

At 0805, Shelton bore 213° distance 4,200 yards from Midway that turned to port to steam parallel to the wakes, going to general quarters. Men on the carrier could see the escort vessel increase speed and alter course, steering to starboard.

0806:15 This is Trolley – We are trying to dodge a torpedo now. The wake is heading for us.

They could see splashes ahead of the torpedo, indicating that it was broaching, the wake pointing toward the doomed Shelton, whose increase in speed heartened those watching – she would clear the torpedo! Suddenly, however, an explosion occurred at 0807, a water spike and debris engulfing the escort vessel’s stern, “causing a large explosion and fire.” Shelton turned quickly to starboard, then went dead in the water with her stern, one witness wrote, “rising at an angle giving an appearance similar to the bow of a net tender.”

0807:15 Vacate (Richard M. Rowell, DE 403) This is Knuckle Two – Stand by injured escort.

TU 77.1.2 had encountered the Japanese submarine RO-41 (Lt. Shiizuka Mitsuo, commanding), over a fortnight out of Kure on her third war patrol and one of five enemy boats sent to deal with the Morotai operation. Shiizuka fired his last four torpedoes at what he believed to be three carriers, and, hearing four explosions and optimistically claimed one carrier sunk and one carrier damaged. Ominously, his attack on Fanshaw Bay and Midway and their screen had occurred less than ten miles south of the southern border of the 30-mile wide submarine safety lane extending from the Admiralty Islands to Morotai. Total bombing restrictions prevailed, and four U.S. boats were known to be in the safety lane, knowledge that complicated the search for the enemy.

Shortly afterward, at 0811, Rear Adm. Sprague directed Richard M. Rowell to help Shelton and then hunt down the submarine. At 0822, the former escort vessel reported a “possible submarine contact” bearing 320°. Fanshaw Bay, meanwhile, turned into the wind and at 0829 launched a pair of TBMs from VC-66 to carry out hunter-killer operations. Midway put aloft a three-plane LASP a minute later, then a single plane inner air patrol and a four-plane TCAP.

On board Shelton, her crew battled fires and jettisoned her torpedoes, and prepared to abandon ship until it appeared that perhaps her men could save the ship, prompting their report “that she might be able to stay afloat.” On the basis of that optimistic dispatch at 0839, Rear Adm. Sprague ordered Richard M. Rowell to take her sister in tow. At 0925, Richard M. Rowell reported a second submarine contact, then a little over two hours later reported all of Shelton’s survivors recovered a quarter of an hour before start of the afternoon watch: 210 survivors, 15 wounded, but ten men dead or missing. At 1129, Midway launched a five-plane TASP relief and a two-plane inner air patrol

At 1130, Ens. William C. Brooks, Jr., A-V(N), USNR, had taken off from Midway in a TBM-1C, side number I [Item] 23, on hunter-killer patrol. As his flight unfolded, he flew over a choppy sea at 2,000 feet, uneventfully until 1213 when ARM3c Raymond J. Travers, Jr., V-6, USNR, Brooks’ radioman, sighted a submarine in the prevailing light haze at a distance of 10 miles, directly off the Avenger’s starboard beam, and notified his pilot. As Brooks, who was not employing radar in view of the “known proximity and general location” of a submarine, neared the boat, it began to submerge, with only the conning tower awash when the TBM was about two to three miles away, the boat crash-diving when the distance closed to a mile to a mile and a half. Brooks discerned no attempt by the submarine to identify herself.

Turning to an intercepting course, Brooks (call sign 83 Derby) called Vacate [Richard M. Rowell], then five miles off the TBM’s port quarter and on a parallel course, and reported the contact. While the escort vessel proceeded to the scene, Brooks released two 350-pound Mk. 47 depth bombs equipped with AN Mk. 234 hydrostatic fuses at an altitude of 800 feet,. One exploded “about 30 feet ahead of swirl directly on sub’s path.” The other detonated “about 70 feet further along plane’s course.” Both ARM3c Travers and AOM3c Joseph A. Downs, V-6, USNR, Brooks’ turret gunner, both saw the Mk. 47s explode.

Relieved on station, Brooks returned to Midway and landed, after which Lt. Richard K. McCreery, A-V(S), USNR, the squadron’s intelligence officer, conducted a thorough post-attack cross-examination of Brooks and his crew in lieu of evaluating photographic evidence given the fact that all operable K-20 cameras, normally employed to document attacks, had been on board other planes.

Richard M. Rowell fired five hedgehog attacks and one 13-charge pattern at what was believed to be a Japanese submarine, the second attack followed by debris and a large air bubble. Tragically, the contact proved to be Seawolf (SS-197), (Lt. Cmdr. Albert M. Bontier), en route to land a U.S. Army reconnaissance party on the island of Samar, in addition to a cargo of supplies. She had exchanged calls with Narwhal (SS-167) at just 0756 that day. Richard M. Rowell’s attack resulted in the loss of the veteran boat and all 99 souls on board.

At 1225, Midway was to recover the first LASP on board. Two of the three planes launched earlier appeared overhead, their pilots received landing instructions, and the LSO brought them in without incident. Lt. (j.g.) Hervey P. Dale, A-V(N), USNR, call sign 89 Derby, in TBM-1C side number I 29, checked in shortly before scheduled to return. Dale reported being ten miles from base. He failed to appear, however, and neither of the other two pilots who had been launched with him had seen him since that time.

Midway then launched a three-plane LASP, one plane for inner air patrol, and a four-plane TCAP, while the search for the missing Item 29 and its three-man crew commenced when the escort carrier launched four FM-2s from VC-65, the Wildcats wobbling aloft at 1434. They returned at 1505, however, and reported no success. Less than one hour later, at 1558, Midway launched six Avengers, as well as an additional four FM-2s, but, a little less than three-quarters of an hour later, welcomed Lt. Joe Riley on board from Morotai at 1636. At 1822, the ship brought the last of those who had been searching for Hervey Dale and his crew, however, their mission having “been to no avail” for “no trace of the missing TBM or its crew was observed.”

Lang (DD-399) and Stevens (DD-479) had arrived on the scene at 1410 to join in the hunter-killer attack, no positive evidence if the destruction of a submarine having been reported. Lang took the crippled Shelton in tow, but the damage proved fatal to the escort vessel, and she sank during the attempt to bring her home.

Meanwhile, Commander Task Force 77 directed TU 77.1.2, now consisting of Fanshaw Bay, Midway, Eversole and Edmonds, to clear the area and set course for Seeadler Harbor, Manus. In cruising disposition 5R (modified), the task unit proceeded as ordered, Fanshaw Bay carrying out a succession (eight of each) of local combat air patrols and antisubmarine patrols during the passage (0528–1749) the following day [4 October 1944], with Belfast (PF-35) and Hutchinson (PF-45) joining up late in the afternoon. The two frigates remained with the disposition until noon on the 5th. Fanshaw Bay carried out flight operations (12 combat air patrols and four antisubmarine patrols) on 5 and 6 October 1944 on the passage to the Admiralties, as well as gunnery practice.

Forming a column of ships, TU 77.1.2 reached its destination on the morning of 7 October 1944 and proceeded, at various courses and speeds, to stand in to Seeadler Harbor and anchor in their assigned berths, the refitting and replenishing process beginning soon thereafter. Three days later, an important event took place in the life of CVE-63. The Chief of Naval Operations had recommended on 14 September 1944 that the name St. Lo be approved for her and that the name Midway be re-assigned to CVB-41, the first of a projected class of large aircraft carriers. Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal approved those actions the following day [15 September 1944], with the changes to become effective 10 October 1944.

Carrying her new name, St. Lo stood out on 12 October 1944 in compliance with Commander TG 77.4 Operation Plan 2-44 and Sortie Despatch 100551, in company with TU 77.4.3, Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, ComCarDiv 25 in Fanshaw Bay, a unit of the larger TG 77.4, Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague, ComCarDiv 22 in Sangamon, a part of TF 77, Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid. White Plains and Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) sortied with TU 77.4.3, with a screen that consisted of the destroyers Hoel (DD-533), Johnston (DD-557) and Heermann (DD-532) and the escort vessels Dennis (DE-405), John C. Butler (DE-339), Raymond (DE-341) and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413). The goodly company of men-of-war stood out through the net gates during the morning watch on the 12th with Sangamon as guide and assumed the disposition of Form 18.

Over the ensuing days, the Allied armada stood toward Leyte with the heavy cruiser Louisville (CA-28) becoming the fleet guide on the 14th. The carriers commenced flight operations the following morning (15 October 1944), Fanshaw Bay, for example, conducted four convoy CAP sorties, two convoy ASP sorties and two visual fighter direction sorties. Inclement weather, however, resulted in flight operations being concluded a little over an hour into the forenoon watch that day, and became “increasingly bad with [a] typhoon center reported approximately north…distant about thirty (30) miles and moving westward” the next morning and continuing into the mid watch on the 17th, with the presence of a typhoon to the northward cancelling the planned early morning strikes against Leyte, with the wind and sea abating by the end of the day.

Ordered to provide air coverage and close air support during the bombardment and amphibious landings, she arrived off Leyte on 17 October. After furnishing air support during landings by U.S. Army Ranger units on Dinagat and Homonhon Islands in the eastern approaches to Leyte Gulf, St. Lo launched air strikes in support of invasion operations at Tacloban on the northeast coast of Leyte, operating with TU 77.4.3. St. Lo steamed off the east coasts of Leyte and Samar as her planes sortied from 18 to 24 October, destroying enemy installations and airfields on Leyte, Samar, Cebu, Negros, and Panay Islands. During that period, on 20 October, Ens. Ray Rushing doggedly pursued a Mitsubishi G4M Type 1 land attack plane, braving heavy return fire from the turret gunner, and pressing home his firing runs to close range. Ultimately, the Betty burst into flames and crashed into the sea.

While St. Lo had been involved in General Douglas MacArthur’s promised return to the Philippines, the Japanese had begun taking action to meeting their adversary’s heralded arrival, by setting in motion Operation Sho.

The carriers of TU 77.4.3 stirred early on the squally, hazy, morning of 25 October 1944, with St. Lo having no scheduled flights at that time, only two TASPs in Leyte Gulf and four LASPs over the task unit. At 0530, Ens. Brooks took off in his TBM-1C with three depth bombs fitted with tail fuses only; soon, five other Avengers were airborne and heading to their assigned sectors. Back on board the ship, Capt. McKenna had “secure” sounded from the dawn general quarters at about 0620.

Ens. Brooks, flying Sector 4 (270°–000°), emerged from a cloud at about 0650 to find Japanese ships arrayed in battle formation below – Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo’s Center Force. Transmitting an immediate contact report to Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, Commander TU 77.4.3, that the enemy bore 330°, north-northwest by ¾ west, between 20 and 30 miles distant, Brooks then circled and radioed an amplifying report that the enemy course was 120°, with his ships moving between 12 and 15 knots: he counted four battleships, four heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and between 10 and 12 destroyers. Upon receipt of Brooks’ electrifying tidings, TU 77.4.3 immediately began a turn to port. St. Lo went to general quarters.