H-Gram 057: The 75th Anniversary of WWII: Operation Downfall and Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, the 150th Anniversary of the Saginaw Gig, and the 75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19.

6 January 2021

Contents

- 75th Anniversary of World War II: Operation Downfall─The Planned Invasion of Japan

- 75th Anniversary of World War II: Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night─The Japanese Plan for Biological Warfare

- 150th Anniversay of the Saginaw Gig

- 75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19

This H-gram focuses on the U.S. plan to invade Japan on 1 November 1945 (Operation Downfall), as well as the Japanese plan to wage biological warfare against the U.S. in World War II using submarine-launched kamikaze aircraft with plague bombs (Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night); also covered is the epic tale of survival following the grounding of the sidewheel steam sloop-of-war Saginaw on Kure Atoll in 1870, as well as additional detail on the disappearance of the five Avengers of Flight 19 in December 1945 (as promised in H-Gram 056).

Download a PDF of H-Gram 057 (6 MB)

Operation Downfall: The Planned Invasion of Japan

In this season of “Peace on Earth, Good Will Towards Men” it is fitting to contemplate and give thanks that Operation Downfall, the U.S. plan to invade Japan, never happened. Instead of what would have been the bloodiest battle in U.S. naval history, hundreds of thousands of U.S. servicemen actually were going to be “home for Christmas” in Operation Magic Carpet.

Operation Downfall had two phases. The first phase, Operation Olympic, was a massive amphibious assault scheduled for 1 November 1945, to seize part of the Japanese home island of Kyushu for use as a staging base for the second phase, Operation Coronet, intended as the decisive landing near Tokyo, scheduled for 1 March 1946. Japanese Intelligence provided a very accurate prediction of where, when, and in what strength the U.S. planned to invade, and they made defensive plans accordingly.

The planned invasion force for Olympic included almost 3,000 ships, carrying over 700,000 U.S. Army and Marines, under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance, Commander U.S. FIFTH Fleet. At the same time, Admiral William Halsey’s THIRD Fleet would have been striking targets on Honshu and Shikoku to isolate Kyushu from the rest of Japan. But it would already have been too late, as the Japanese actually did reinforce Kyushu with over 900,000 troops and a massive number of civilian “volunteers” who were expected to fight and die to the last along with the soldiers. Although U.S. Intelligence provided increasingly high estimates of the number of Japanese troops and aircraft involved, these estimates were still lower than what the Japanese were actually doing.

The Japanese strategy was to inflict the maximum number of casualties on the American force, regardless of the cost to the Japanese (military and civilian) with the intent to break the resolve of the American people to continue to support the Allied objective of “unconditional surrender.” The Japanese hope was that a massive death toll would lead to a negotiated end to the war, one that did not involve foreign occupation of Japan, something that had never happened in over 2,000 years of Japanese history. The Japanese defense plan, Ketsugo, called for the ultimate effort to defeat the U.S. amphibious invasion force just as it approached the beachhead at Kyushu, with the troop transports as the highest priority targets just when they were most vulnerable. Every aircraft that could fly would be committed to kamikaze suicide attacks, along with a surprisingly large number of suicide boats, midget submarines, manned suicide torpedoes, and suicide frogmen while the invasion force was trying to come ashore, where it would be met with very extensive and carefully prepared defensive positions, specifically sited and constructed to withstand heavy naval and aerial bombardment.

There were many casualty estimates prepared for Operation Downfall. These have become “politicized” over the years in the argument over whether the use of the atomic bombs was necessary. All of the various estimates contain huge assumptions (most wrong) and it is impossible to say with any degree of accuracy how the battle would have turned out, other than that the cost to both sides would almost certainly have been staggering. For example, the Japanese had been hiding and hoarding aircraft and aviation fuel for the final defense of Japan. Their plan called for throwing as many kamikazes against the amphibious ships in the first three hours as were thrown against U.S. Navy forces in three months off Okinawa. If the kamikaze aircraft alone had achieved the same hit per sortie ratio as at Okinawa the result would have been as high as almost 100 ships sunk, 1,000 damaged, and 12,000 Sailors killed. Subs, mines, suicide boats, frogmen, and the Japanese “home field advantage”─all would have only added to the toll. Well aware of how the Japanese had fought to the death at every island in the Pacific, but especially Saipan, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, Fleet Admirals Leahy, King, Nimitz, and Admiral Spruance all argued against an invasion; they understood what was going to happen.

For more on Operation Downfall, please see attachment H057.1.

Aichi M6A1 Seiran at the Udvar-Hazy Center. Aichi chief engineer Toshio Ozaki designed the Seiran (Clear Sky Storm) during World War II to fulfill a requirement for a bomber that could operate exclusively from a submarine. (Photo from Udvar-Hazy Center; Smithsonian web ID: WEB10862-2008)

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night

On 22 September 1945, the Japanese planned to attack San Diego, California, with 15 Seiran float planes launched from five of their massive I-400-class aircraft-carrying submarines (largest in the world) on kamikaze missions to spread millions of fleas infected with bubonic plague, in retaliation for the fire-bombing of most of their major civilian population centers. The raid never happened, for the most obvious reason that Japan surrendered before the plan, code-named Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, could be executed. The other big reason was that the Japanese didn’t have five I-400s ready; only two had been completed and in service as aircraft carrier submarines (a third was completed as a tanker). Nevertheless, the planning for the raid was extensive and it was probably technologically feasible as even in 1945 the Japanese still had surprises up their sleeve; for example, U.S. and Allied Intelligence did not know the specially-built Seiran existed.

Japan’s biological weapons program was extensive, led by the notorious “Unit 731” which conducted horrific experiments on live humans and deployed biological agents against the Chinese, causing an undetermined but believed-to-be very high casualty count. Whether a bubonic plague weapon deployed against the U.S. West Coast would have caused similarly high casualties is unknown, but quite likely could have provoked substantial psychological terror amongst U.S. civilian population, which to that point had been spared the horrors of war experienced by the Japanese civilian population. Given the advanced state of U.S. “Ultra” code-breaking and radio intelligence by that point of the war in tracking Japanese submarine general operating areas, it is also likely that the Japanese would not have achieved surprise in the attack (although the biological weapons might very well have been a very nasty surprise). Fortunately, the atom bomb prevented what might have happened. For more on the I-400 submarines and Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night, please see attachment H057.2.

The Gig of the Saginaw, by Stanley Owens Davis, Sr., USNR (1917-1958), oil on canvas, painted in 1937. Gift of the artist's wife, Margaret Davis, and his son, LCDR Stanley Owens Davis, Jr., USN, to the Naval War College Museum.

150th Anniversary of the Saginaw Gig

On 18 December 1870, the extensively modified captain’s gig of the Saginaw, with five volunteers on board, completed a 1,400-mile, 28-day voyage under sail from Kure Atoll, where the sidewheel steam sloop-of-war Saginaw had wrecked on 29 October. Severely debilitated by malnourishment and sickness after the provisions spoiled, four of the men died as the boat tumbled ashore in the crashing surf of Kauai’s north shore; only Coxswain William Halford barely survived. By that narrow margin, ships were dispatched by the American Consul and the Kingdom of Hawaii, which rescued 88 other survivors of Saginaw (half USN crewmen and half civilian contractors); all of Saginaw’s crew, except the four on the gig, survived the sinking and 68 days on the atoll, including Saginaw’s captain, Commander James Sicard, who went on to serve many years as the chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, make rear admiral, and served with credit during the Spanish American War. Halford was awarded the Medal of Honor for his gallantry (he was recalled to active duty during WWI, serving as an acting lieutenant at the age of 77). The gig still exists, and after an almost 150-year odyssey of its own, is now in the custody of the Naval History and Heritage Command undergoing preservation work. For more on this epic tale of courage and survival, please see attachment H057.3.

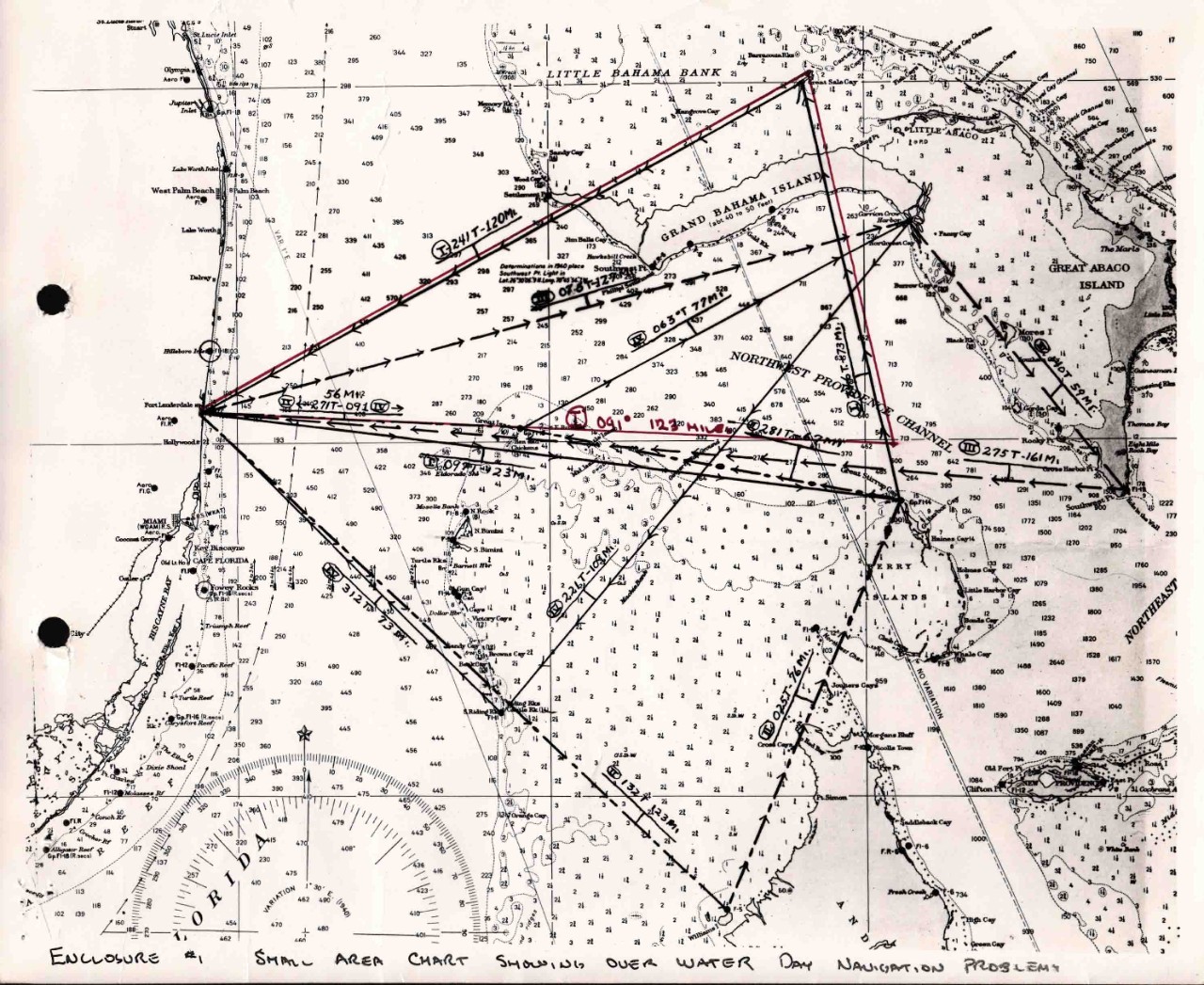

Map of Navigation Problem No. 1 for Flight 19. Flight 19 was a flight of five Navy Avenger aircraft lost off the coast of Florida on 5 December 1945. National Archives identifier 73985447.

75th Anniversary of the Loss of Flight 19

In H-Gram 056 I provided a brief synopsis of the mystery of Flight 19; five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers that were lost on a training mission over the Bahamas on 5 December 1945. I promised more detail, so if interested please see attachment H057.4.