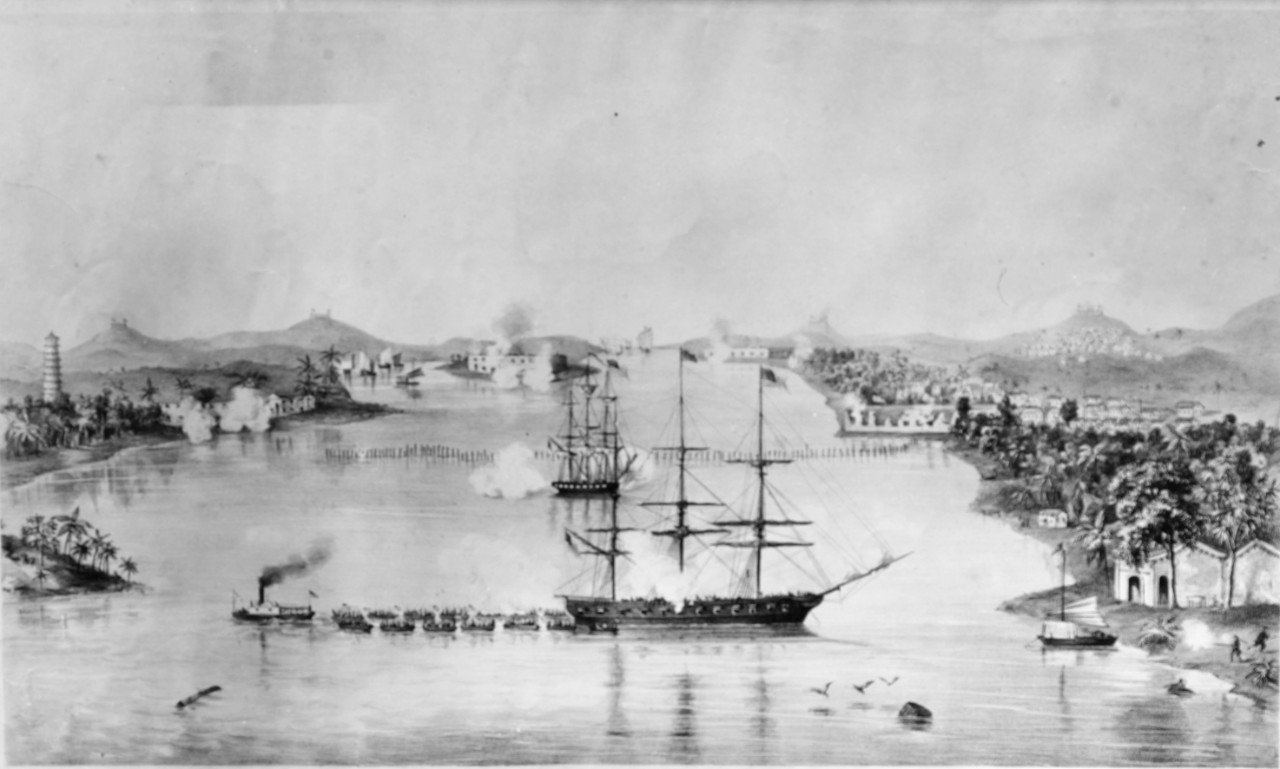

H-063-1: The Battle of the Pearl River Forts, China, 1856

The attack on the barrier forts on the Pearl River near Canton, China, by the American squadron, 21 November 1856. The force consisted of Portsmouth, Levant, and steam frigate San Jacinto. Landing parties were commanded by Captain Foot (Portsmouth), Captain Bell (San Jacinto), and Captain Smith (Levant) (NH 56895).

In 1856, the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing (Ching) dynasty in China was still raging, resulting in the deaths of millions of Chinese and breakdown of law and order. That October, the Second Opium War broke out between the British and Qing China, this time with France joining in with the British (the First Opium War, 1839–42, was between the British and Qing China). As in the First Opium War, the Chinese were trying to keep opium out. Opium was the primary commodity that Britain and other Western countries used to trade for Chinese goods (i.e., the Europeans were the “pushers”). With the outbreak of the Second Opium War, Chinese factions increasingly threatened the interests of all foreign nations in China, including those of the United States, in particular at Canton (now Guangzhou). Canton was one of five Chinese ports open to trade with the West and had a significant U.S. commercial presence. The city is a number of miles up the Pearl River, which enters the sea between Macau to the south and Hong Kong to the north.

With the apparent rapidly increasing threats to U.S. citizens and interests, the American consul in Canton, Oliver H. Perry (son of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry), requested help from Commander Andrew Hull Foote, commanding officer of the sloop-of-war USS Portsmouth, then at anchor off Whampoa, about eight miles downstream from Canton, having arrived on 23 October.

Portsmouth, commissioned in 1844, had a crew of about 200 officers and sailors, and was originally armed with two 64-pounder Paixhans “shell guns” and 18 medium 32-pounder broadside guns. (Paixhans guns were the first guns designed to fire exploding shells instead of solid shot. Designed by the French, they were quickly adopted by the U.S. Navy in the 1840s until superseded by the safer and more powerful Dahlgren guns in the late 1850s.) However, Portsmouth had been ungraded with 16 new 8-inch Dahlgren shell guns before being assigned to the East India squadron. She had the distinction during the Mexican-American War of landing the force that captured Yerba Buena (later to become San Francisco, California) on 9 January 1846. Portsmouth had departed the U.S. West Coast in May 1856, with Commander Foote in command, to join the U.S. East Indies Squadron.

Andrew Hull Foote began his naval career as a midshipman in 1822 on board the 10-gun schooner USS Grampus (lost in a storm with all 25 hands in 1843—see H-Gram 060). Foote was aboard 30-gun frigate USS John Adams for her 1838–42 circumnavigation of the earth, including participation in the Battle of Muckie (see H-Gram 062). While aboard the 50-gun frigate USS Cumberland, Foote formed a temperance society, which would ultimately lead to the end of grog rations aboard U.S. ships by 1862 (Cumberland would be the first ship sunk by the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia—ex-USS Merrimack—in 1862). In 1849–51, Foote commanded the 8-gun brig USS Perry on West African slave trade–suppression duty. Foote was an outspoken abolitionist. He was promoted to commander in 1856 and given command of Portsmouth.

On 23 October 1856, Foote wasted no time in leading a party ashore into Canton by small boat. It was made up of five officers (one a Marine), 60 sailors with a boat howitzer, and 18 Marines. There was no opposition to the landing by the Chinese forts guarding the Pearl River approach to Canton. Between Whampoa and Canton, the Pearl River was covered by four Chinese forts (two on the north bank, one on the south bank and one on an island in the center of the river). Between them, the forts had 176 guns, some as large as 8-inch and 10-inch calibers, and were well-constructed using the latest European designs. Chinese troops in the forts and in the vicinity of Canton numbered several thousand. The small U.S. Navy and Marine force took up positions on rooftops and in some new fortifications around the American compound in the city.

On 27 October, a second sloop-of-war, USS Levant, arrived at Whampoa. Levant added another 20 Marines, a detachment of sailors, and another boat howitzer to the U.S. compound in Canton, bringing the total ashore to about 150. (The foreign compounds, known as “factories,” lined the riverbank outside the walls of the city itself.) On 3 November, there was an exchange of gunfire between U.S. sentries ashore and Chinese troops, but no U.S. personnel were hurt. The American steamer Cum Fa also reported being fired on. As this was going on, a British assault force had forced its way into Canton. A few Americans accompanied the British and waved the U.S. flag from the breached city wall, which Foote immediately put a stop to as it compromised U.S. neutrality.

Levant was commanded by Commander William B. Smith. Commissioned in 1838, with a crew of about 200, the vessel had an older weapons fit than Portsmouth consisting of 18 “short” 32-pounder broadside guns, although her four 24-pounder long guns had been replaced by four new 8-inch Dahlgren guns. During the Mexican War, Levant was part of the squadron that captured Monterey, California, in July 1846. After serving in the Mediterranean for several years, Levant joined the East Indies Squadron in May 1856.

On 12 November, the screw frigate USS San Jacinto arrived at Whampoa from Shanghai with Commodore James Armstrong embarked as the commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron. Armstrong had begun his career as a midshipman aboard the 22-gun sloop-of-war USS Frolic when she was captured on 20 April 1814 after a running gun battle with 36-gun frigate HMS Orpheus and 12-gun schooner HMS Shelburne. He had been promoted to commodore and given command of the East Indies Squadron in 1855.

The steam-powered San Jacinto was built as an experimental vessel and was one of the first in the U.S. Navy propelled by a screw propeller instead of sidewheel paddles. She was armed with six 8-inch smoothbore shell guns. (By now, you should be getting a sense of the logistics challenges as U.S. ships were armed with all kinds of different guns during this period.) First commissioned in 1851 or 1852 (records are missing), her steam engines were troublesome throughout her entire service life. After extensive repair, she was recommissioned in October 1855, under the command of Captain Henry H. Bell.

San Jacinto departed New York on 25 October 1855 and transited via the Madeira, Cape of Good Hope, Mauritius, Ceylon, Penang, and Singapore, where Commodore Armstrong relieved Commodore Joel Abbott in command of the squadron. San Jacinto then took U.S. envoy Townsend Harris to Siam, where he negotiated a trade treaty with the King of Siam, Mongkut (who would later be very inaccurately portrayed in the musical The King and I). San Jacinto then took Harris to Shimoda, Japan, to establish the first foreign diplomatic mission on Japanese soil (this leg of the voyage took several months until August 1856, as San Jacinto’s engines kept breaking down).

Upon arriving at Whampoa, Armstrong conferred with Foote, who came down river by boat. Although Armstrong concurred with the actions that Foote had taken in putting Marines and sailors ashore to protect the American compound, he also believed it would be considered a provocation. While seeking to open negotiations with Chinese authorities in Canton, Armstrong nevertheless ordered 28 more Marines (from San Jacinto) to go ashore under the command of Marine Captain John D. Simms, who would assume command of the combined Navy and Marine force ashore. Armstrong and Foote were both aware of the extreme danger posed by the Chinese forts to U.S. personnel and supplies transiting via the river between Whampoa and Canton. They considered making the transits at night, but opted against it, thinking the Chinese might also consider that a provocation.

Despite the tense atmosphere, the American consul and Chinese authorities in Canton reached an agreement that the United States would not intervene in the war between China and Britain and France, and the Chinese would guarantee the safety of U.S. interests in Canton. As a result, the Americans agreed to withdraw the Navy-Marine force from the city, only leaving Commander Smith and a small number of Marines. Armstrong decided that Portsmouth and San Jacinto would remain at Whampoa, while Levant would move upstream to Canton as a contingency.

On the evening of 15 November, Foote was in the last boat rowing down the river when the largest fort opened fire with five rounds. No one was hit, but Armstrong and Foote were incensed at this apparent breach of good faith, and viewed it as an insult to the U.S. flag (which was flying on Foote’s boat). The next day, Armstrong ordered a small unarmed boat from San Jacinto to proceed up the river to take soundings in support of possible movement of his ships upstream. When the survey boat drew within a half mile of the first fort, the Chinese opened fire with both round shot and grapeshot (anti-personnel rounds). The first volley went long right over the boat. In a second volley, the grape hit astern, but a round shot hit and killed the coxswain. The third volley was short. The survey boat returned downstream. While this was going on, the American steamer Cum Fa towed the boats with the withdrawing force down river unmolested.

Armstrong decided that this outrage could not go unanswered. He shifted his flag from San Jacinto to Portsmouth because San Jacinto drew too much water to proceed much further upstream from Whampoa. Most of her crew was cross-decked to Portsmouth and Levant. Commander Bell assumed command of Levant as Smith was still in Canton.

At 1500 on 16 November, Portsmouth and Levant went to battle stations and began moving upstream under tow by two small American merchant steamships, Cum Fa and Willamette, with the intent to bombard the Chinese forts. Due to the narrow channel and current, this would be a risky proposition because the two ships would be stationary at anchor. Levant ran aground before coming in range of the first fort. Portsmouth continued toward the forts and, at 1530, anchored 500 yards from the closest one. All the Chinese forts opened fire, but most shots passed through the rigging with little damage. Portsmouth returned fire, with much greater accuracy. The bombardment by both sides went on until sunset, with Portsmouth firing 230 shells plus grapeshot at the fort. She was hit in the hull six times, only one hit considered serious, and grapeshot tore up her rigging, but the ship was not seriously damaged and only one Marine was badly wounded.

Levant was refloated overnight and towed into range. There was a lull for the next three days as the Chinese did not seem inclined to renew the battle. Armstrong attempted to negotiate with the Chinese to no avail and then suddenly took ill. He returned to San Jacinto and turned over command to Foote with instructions not to fire unless the Chinese attacked. However, faced with four granite forts, the strongest in China, with 176 guns and reports of somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 Chinese troops in the Canton area, Foote determined that the best course of action was to attack. On 19 November, Armstrong gave Foote orders to take any action necessary to forestall a Chinese attack, exactly the longer leash Foote wanted.

On the morning of 20 November, on Foote’s orders, Portsmouth and Levant (with Commander Smith back in command) were maneuvered into firing position by the steamships and opened fire on the forts. The forts returned fire within five minutes, slackening only after about an hour. The ships provided covering fire as three columns of boats put 287 men ashore, led personally by Foote. The initial landing was unopposed, although two apprentice boys were killed by the accidental discharge of a rifle. The first objective was the downstream fort on the north bank. About 50 Marines under Captain Simms and a detachment of sailors with a howitzer went up the bluff, through a village, and assaulted the fort from the rear. Although the fort was strong, the Chinese troops were poorly trained, poorly led, and unmotivated. Most of the Chinese troops fled, some jumping into the river. About 40 or 50 Chinese were killed, mostly as they were fleeing.

However, it didn’t take long for a Chinese force to counterattack. The Marines had chased the Chinese through the village and into the rice paddies, when soon they were attacked by about 1,000 Chinese reinforcements coming from Canton. Sims ordered his men to hold fire until the Chinese were within 200 yards. The Chinese suffered numerous casualties, but initially stood their ground despite accurate fire from the Marines. Fire from the boat howitzers on wheeled carriages also inflicted many casualties. The Chinese tried to attack two more times before they were finally beaten back, broke, and fled. Americans turned some of the guns of this fort against the next one upstream on the north shore (referred to as the “Center Fort”). The other fort responded and one shot sank Portsmouth’s launch. At the end of the day, Foote and Smith returned to the ships, leaving Commander Bell in charge ashore.

Just before dawn on 21 November, the Chinese fort on the south bank (referred to as “Fiddler’s Fort”) opened fire on Portsmouth, scoring a hit with an 8-inch round near the waterline. Two rounds of return fire from Portsmouth’s 8-inch guns ended the duel. Both ships bombarded Fiddler’s Fort as Cum Fa towed lines of boats with Marines and sailors across the river from the fort captured the previous day. The three Chinese forts divided their fire between the two U.S. warships and the boat lines. Chinese fire was heavy but wildly inaccurate, although one 68-pound shot ripped through San Jacinto’s launch, killing three and wounding seven Americans. Once again, Simms led his men up and behind the fort. The garrison fled ahead of the Marines’ assault, and this time about a 1,000 Chinese stayed out of range of the boat howitzers.

After taking the second fort, Simms’ Marines cleared the shoreline, encountering a seven-gun Chinese battery outside the fort. The surprised Chinese fled and Simms destroyed the guns. By this time, the U.S. force had turned the guns of the first two forts against the remaining two, and by nightfall the third fort, located on the island in the river, had been abandoned and fell easily.

During the night, the U.S. force spiked all Chinese artillery that would not be useful in the assault against the last and strongest fort, on the opposite bank of the river. (“Spiking” a cannon means to drive a metal rod or large nail into the touchhole so that the cannon can’t be fired. Technically this only temporarily disabled the gun, but getting the spike back out was extremely difficult.) The most capable captured Chinese guns were trained on the last fort.

At first light on 22 November, an American howitzer fired on the last fort, with no response. More artillery fired on the fort, again with no response. Three lines of American boats began moving across the river, under cover of a heavy barrage from both U.S. and captured Chinese guns. Only as the American boats reached the shore did the Chinese finally open fire with a hail of grapeshot, virtually all of which passed overhead. By the time the Marines had waded ashore and through heavy muck, the Chinese had abandoned the fort after disabling the guns, leaving one loaded cannon with a lit fuse pointed in the general direction of the boats. Marines snuffed the fuse before the gun fired. Over the next days, Foote’s force beat off several large but ineffectual Chinese counterattacks, the most vigorous a surprise night attack on 26 November.

During the bombardments, Levant was hit 22 times in the hull and rigging, suffering one dead and six wounded. Portsmouth was hit 27 times. Neither ship was seriously damaged.

Once in control of all four forts, Foote’s force proceeded to destroy them. All remaining operable Chinese guns were spiked and then rolled into the river. The walls were blown up by demolition teams. On 5 December, an accidental spark prematurely ignited powder being placed under the wall of the last fort, killing three men of the demolition team and wounding seven others. On 6 December, Portsmouth and Levant moved back downstream to join San Jacinto at Whampoa (this time, Portsmouth ran aground and had to be refloated).

When the battle was over, the four strongest forts in China were ruined, with as many as 250–500 Chinese killed. U.S. casualties included seven killed in action and three killed in the demolition accident, along with 32 wounded. Somewhat amazingly, no Marines were killed, although one subsequently died from illness.

The destruction of the Pearl River forts brought about a mixed outcome. Chinese authorities in Canton quickly issued an apology for the unprovoked attack on 16 November. In the words of a Marine Corps history, “Foote had avenged an insult to the American flag and made certain that the Chinese at Canton would behave in the future.” Nevertheless, after the American consul and remaining Americans withdrew from Canton, the Chinese burned down the foreign compounds. In the aftermath of the event, Foote came under considerable criticism for being overly belligerent, and there were those who believed the entire action was unnecessary and could have been avoided. Other critics blasted Commodore Armstrong for not being aggressive enough. Regardless, the United States and China subsequently signed a neutrality agreement, which both sides honored except for one U.S. infraction during the combined Anglo-French assault on the Chinese forts at Taku on the Hai River in June 1859.

The Chinese actually learned much from their defeat at the Pearl River forts that they incorporated into their defense of the Taku forts. Under a much more able commander, the Chinese gave the Anglo-French force a decisive defeat. The British lost three gunboats sunk, three run aground, 81 killed, and 345 wounded. The French suffered 12 killed and 23 wounded. Both British and French admirals were wounded. The commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, Commodore Josiah Tattnall (who had relieved Armstrong) was observing the battle from the chartered steamer Toey-Wan (ex-HMS Eaglet), when he decided to assist the British by towing some of their boats, One American was killed and another wounded.

Following the Battle of the Pearl River Forts, Commodore Armstrong returned to the U.S. in poor health. He was in command of the Pensacola Navy Yard when Florida voted to secede from the Union in January 1861 and surrendered the facility a few days later (four months before South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter, starting the Civil War). Captain Henry Bell, commander of San Jacinto, fought for the Union in the Civil War and returned to the Far East as commander of the East Indies Squadron. He was killed in a boat accident at Osaka, Japan, in 1868, becoming the first rear admiral to die in the line of duty (I think). Two ships were named after Bell: Wickes-class destroyer DD-95 (1917–22) and Fletcher-class destroyer DD-587 (1943–46, 12 Battle Stars).

Commander Foote, commander of Portsmouth, went on to a very distinguished war record during the Civil War in command of the Mississippi Gunboat Flotilla during the battles of Fort Henry, Fort Donaldson, and Island No. 10. Foote was promoted to rear admiral in 1862, but died shortly after of natural causes. Three ships were named after Foote: Foote-class torpedo boat TB-3 (1896–1920), Wickes-class destroyer DD-169 (1918, lend-lease to Britain in 1940, lend-lease to Soviet Union in 1944, scrapped 1952), and Fletcher-class destroyer DD-511 (1942–46, four Battle Stars). Fort Foote on the Potomac was also named for him in 1863.

San Jacinto served in the Africa Squadron in 1859–61, where she captured the slave ship Storm King near the mouth of the Congo River, and returned 616 Black slaves to Africa. During the early Civil War, under the command of Captain Charles Wilkes, San Jacinto became famous for her involvement in the “Trent Affair,” a flagrant violation of British neutrality by Wilkes (see H-Gram 062). After otherwise creditable service during the war, San Jacinto ran aground on a reef in the Bahamas in 1865; the crew was saved, but the ship could not be.

Portsmouth departed the Far East in 1858, served during the Civil War, and then served as a training ship between 1878 and 1915. Levant was assigned to the Pacific Squadron in 1859. She disappeared with all 155 hands after departing Hilo, Hawaii, on 18 September 1860 (see H-Gram 060/H-060-2).

Sources include: The Battle of the Barrier Forts, by Bernard C. Nalty, Marine Corps Historical Reference Series No. 6, Historical Branch G-3 , December 1958; Far China Station: The U.S. Navy in Asian Waters, 1800–1898, by Robert Erwin Johnson, Naval Institute Press, 2013; and the NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS).