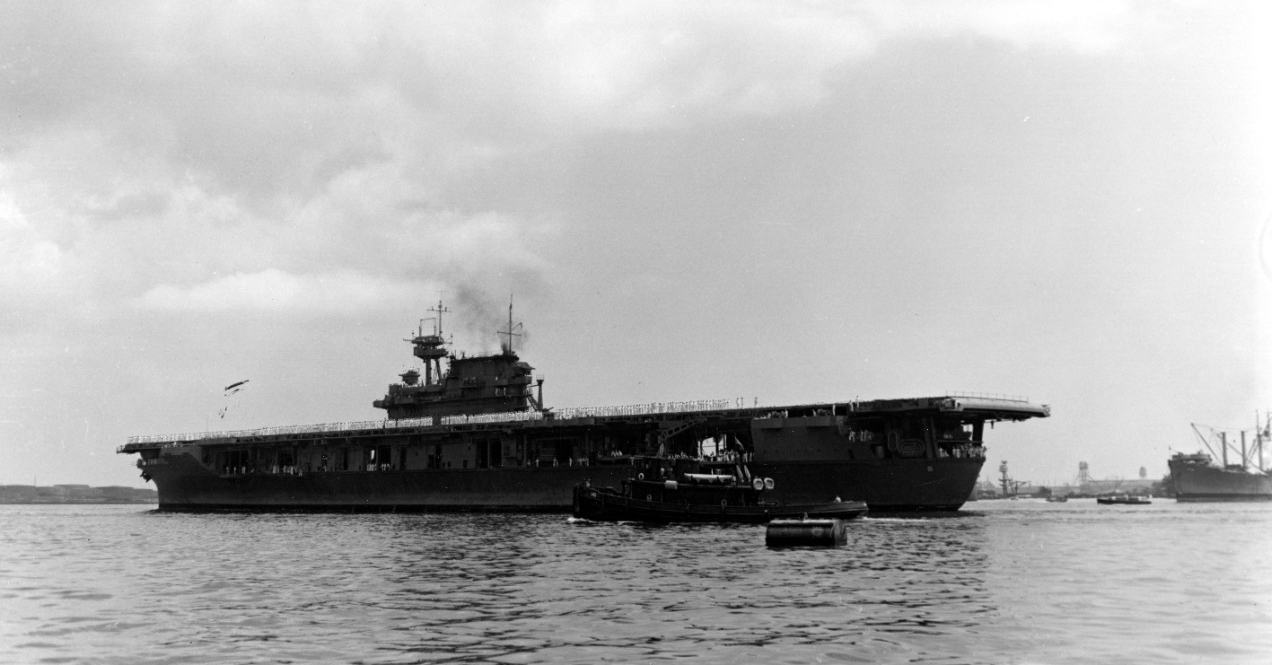

USS Yorktown (CV-5)

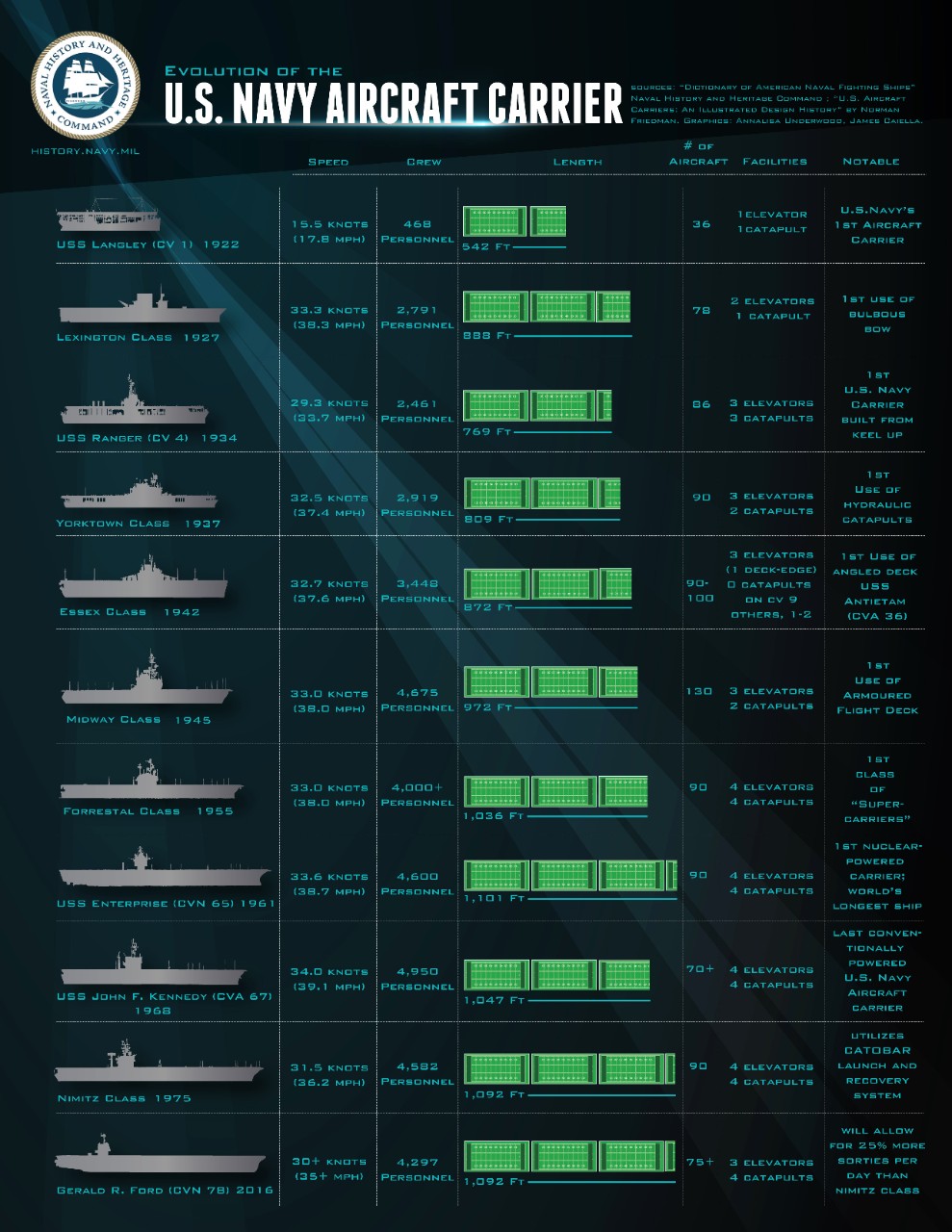

USS Yorktown (CV-5) was commissioned at Naval Operating Base Norfolk, Virginia, on 30 September 1937, with Captain Ernest D. McWhorter in command. After shakedown training that took the aircraft carrier to the Virgin Islands, Haiti, Guantanamo Bay, and Cristobal in the Panama Canal Zone, she returned to Norfolk for subsequent repairs in the fall of 1938. After operating along the eastern seaboard into early 1939, Yorktown participated in her first war game, Fleet Problem XX, which called for one fleet to control the sea lanes in the Caribbean against the incursion of a foreign European power while maintaining sufficient naval strength to protect vital American interests in the Pacific. The maneuvers were conducted with her sistership, USS Enterprise (CV-6), and witnessed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The fleet problem revealed—with convoy escort, antisubmarine defense, and various attack measures against surface ships and shore installations—that if war came to American shores, aircraft carriers could make significant contributions to the war fighter. After steaming to the Pacific in late April 1939, she operated out of San Diego, California, into 1940. Yorktown participated in another fleet problem (Fleet Problem XXI) that would ultimately characterize future warfare in the Pacific. The two-part exercise was devoted to screening and scouting, convoy protection, and the seizure of advanced bases. It also pointed out the need to coordinate Army and Navy defense plans for the Hawaiian Island. Yorktown operated in Pacific waters until April 1941 when the success of German U-boats preying upon British shipping in the Atlantic required a shift of American naval strength. Therefore, the Navy transferred a substantial force from the Pacific including Yorktown, a battleship division, and accompanying cruisers and destroyers, to reinforce the Atlantic Fleet. From that time until the United States officially entered World War II, Yorktown conducted multiple patrols in the Atlantic to enforce American neutrality.

In the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the Pacific Fleet was reeling. Although there were no American aircraft carriers damaged or sunk during the attack, the fact remained that there were only three carriers in the Pacific—Enterprise, Lexington (CV-2), and Saratoga (CV-3). While Ranger (CV-4), Wasp (CV-7), and the recently commissioned Hornet (CV-8) remained in the Atlantic, Yorktown steamed for the Pacific reaching San Diego on 30 December 1941, where she shortly thereafter became flagship for Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher's newly formed Task Force (TF) 17. On 6 January 1942, Yorktown on her first mission in a new theater, successfully escorted a convoy carrying Marine reinforcements to American Samoa. TF-17, in conjunction with TF-8, also conducted similar troop movements to Tutuila and Pago Pago to augment the garrison already in place at those locations. At the end of January, TF-17 and TF-8 parted ways. TF-8, centered on Enterprise, steamed for the Marshall Islands, while TF-17, centered on Yorktown, steamed for the Gilberts.

In the first American offensive of the war, Yorktown, screened by Louisville (CA-28), St. Louis (CL-49), and four destroyers, launched 11 torpedo planes (Devastators) and 17 scout bombers (Dauntlesses) in the early morning of 31 January that hit what Japanese shore installations and shipping they could find at Jaluit, however, adverse weather conditions hampered the mission. Six of Yorktown’s aircraft were lost. Other Yorktown aircraft attacked Japanese installations and ships at Makin and Mill Atolls. A second attack was planned, but was cancelled due to the weather. Yorktown’s force subsequently retired to the sea and later returned to Pearl Harbor for replenishment. On 14 February, Yorktown was underway for the Coral Sea.

On 6 March, Yorktown rendezvoused with TF-11, which was centered on Lexington, and steamed towards Rabaul and Gasmata to attack Japanese shipping in an effort to stop the Japanese advance and to cover the landing of Allied troops at Noumea, New Caledonia. However, as the powerful Allied force approached their area of operations, word came the Japanese were advancing towards Australia with a landing at Huon Gulf, in the Salamaua-Lae area on the eastern end of New Guinea. The move prompted the task force commander, Rear Admiral Wilson Brown, to change the objective to the Salamaua-Lae sector. On 10 March, both flattops launched attacks on shipping at Salamaua and auxiliaries moored close in shore at Lae. Of the 104 aircraft launched, only one was lost to antiaircraft fire. For many of the pilots, it was their first combat experience. The task force retired to sea, and then resumed patrols in the Coral Sea. After the raid, the situation in the South Pacific appeared to have stabilized, so the task force steamed for the harbor at Tongatabu, in the Tonga Islands, for needed upkeep. However, the enemy was soon on the move.

On 27 April, Yorktown was underway once more for the Coral Sea, however, on 3 May, word came from Australian-based aircraft that Japanese transports were disembarking troops and equipment at Tulagi in the Solomon Islands. The Japanese planned to commence construction of a seaplane base there to support their southward thrust. Yorktown accordingly set course and by the following day was within striking distance of the newly established Japanese beachhead. Yorktown launched its first strike at daybreak. Yorktown's air group made three consecutive attacks on enemy ships and shore installations at Tulagi and Gavutu. In the attacks, Yorktown’s aircraft delivered 22 torpedoes and 76 bombs that sank Japanese destroyer Kikuzuki, three minecraft, and four barges. Meanwhile, later that day, a cruiser-destroyer force joined the group completing the composition of the Allied task force on the eve of the crucial Battle of the Coral Sea.

On the morning of 6 May, Allied forces gathered under the tactical command of Fletcher. At daybreak the following morning, the task force with cruisers and destroyers headed toward the Louisiade archipelago to intercept any enemy attempt to move toward Port Moresby. Meanwhile, while Fletcher moved northward with his two flattops and their screens in search of the enemy, Japanese search planes located oiler Neosho (AO-23) and her escort Sims (DD-409). Two waves of Japanese planes, first high level bombers and then dive bombers, attacked the two ships. Sims took three direct hits and sank quickly with a heavy loss of life. Neosho took seven direct hits, but remained afloat for a few more days until she was sunk by the Allies. Both ships performed a valuable service in that they drew the Japanese away from the carriers. Meanwhile, Yorktown and Lexington's aircraft located Shoho and punished the Japanese light carrier unmercifully, sending her below the waves. The following morning, 8 May, a search plane from Lexington located the carriers Zuikaku and Shokaku. Yorktown’s aircraft scored two hits on Shokaku that heavily damaged her flight deck and thus prevented her from launching aircraft.

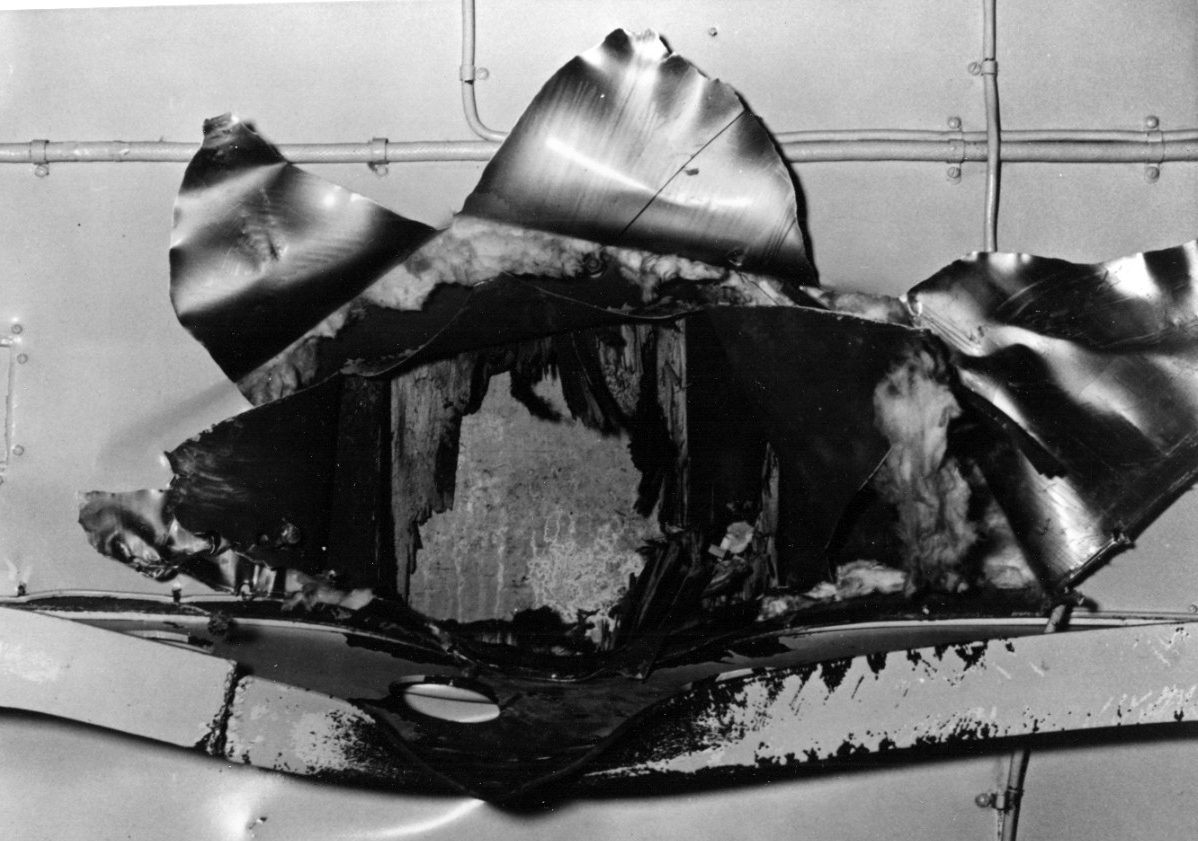

While the carrier’s aircraft continued to pound the Japanese flattops, intelligence reported the enemy had located the American carriers and were planning a retaliatory strike. Sure enough, shortly before noon, the attack came. Although American Wildcats were able to slash through the Japanese formations, downing 17, some of the enemy aircraft were able to slip through the fighters. Lexington took two torpedoes on her port side and three bomb hits causing her to list. Meanwhile, Yorktown was having problems of her own. Although the carrier was able to dodge eight torpedoes, a bomb penetrated the flight deck and exploded below deck, killing or seriously injuring 66 of her crew. Yorktown’s damage control party managed to get the fires under control, but shortly thereafter, a massive explosion from Lexington rocked the ship. Despite a valiant effort by the crew, Lexington’s commander gave the “abandon ship” order. Once the crew was rescued from the water, a torpedo from a nearby cruiser was deployed into Lexington, which hastened the end of “Lady Lex.” The Battle of the Coral Sea was costly for both sides. The Japanese had won a tactical victory, inflicting comparatively heavy losses on the Allied force, however, the Allies, in stemming the tide of Japan's conquests in the south and southwest Pacific, had achieved a strategic victory. They had stopped the drive toward strategic Port Moresby and had saved the fragile lifeline between America and Australia.

The damage Yorktown suffered during the battle was estimated to take about three months for the overhaul. Unfortunately, there was little time for repairs, because Allied intelligence—notably the cryptographic unit at Pearl Harbor—had gained enough information from decoded Japanese naval messages to estimate that the Japanese were on the threshold of a major operation aimed at two islets in a low coral atoll known as Midway. As Admiral Chester W. Nimitz began to plan for battle, which included Yorktown, yard workers at Pearl Harbor miraculously labored around the clock and made enough repairs to enable the ship to be put to sea. On 30 May, Yorktown steamed to Midway as the central ship of TF-17.

At dawn on 4 June, Yorktown launched a 10-plane group of Dauntlesses, which searched for a distance of about 100 miles out but found nothing. The group returned to the ship at 0830. When the last of the initial attack group had landed, Yorktown launched a second attack group. Meanwhile, Enterprise and Hornet launched their attack groups as well. Torpedo planes from the three flattops located the Japanese carrier striking force, but of the 41 launched only six returned. However, the destruction of the torpedo planes served a purpose. The Japanese had broken off their high-altitude cover to concentrate on the Devastators that were flying low above their ships. This left the skies above wide-open for the Dauntlesses. Yorktown's dive-bombers pummeled Soryu, making three lethal hits with 1,000-pound bombs that turned the ship into a flaming inferno. Meanwhile, Enterprise’s planes struck Akagi and Kaga turning both into fiery wrecks in a very short time. The bombs from the Dauntlesses caught all of the Japanese carriers in the midst of refueling and rearming operations, and the combination of bombs and gasoline was explosive and disastrous to the Japanese.

The Japanese had already lost three carriers, however, a fourth, Hiryu, remained at large. Separated from her sister ships, Hiryu launched a strike force of 18 “Vals” that soon located Yorktown. At about 1329, Yorktown’s radar picked up the incoming attack group, and subsequently launched her fighters. About 15 to 20 miles out, the Wildcats intercepted the Japanese and attacked vigorously. Planes were flying in every direction and many were falling from the sky. Despite the valiant effort to keep the enemy attack planes from Yorktown, three scored hits on the ship. Although the attack was devastating to Yorktown, she managed to somewhat recover and began to launch aircraft to fend off the Japanese attack. However, during the fighting, two torpedoes ripped through Yorktown’s port side. The carrier was mortally wounded. She lost power and went dead in the water with a jammed rudder and an increasing list to port. As the list continued to increase and all power lost, the “abandon ship” order was given. Although Yorktown was dead in the water, her aircraft were still fighting in the air, joining those from Enterprise in striking the Japanese carrier Hiryu late that afternoon. After taking four direct hits, the Japanese flattop was soon helpless. She was abandoned by her crew and left to drift. Yorktown had been avenged. Although efforts to save Yorktown were ongoing, the Japanese submarine I-158 managed to move into firing range undetected and fired torpedoes scoring two hits on Yorktown. On 7 June at 0701, the valiant flattop turned over on her port side and sank in 3,000 fathoms of water.

Yorktown received three battle stars for her World War II service. Although Yorktown’s service to the nation was relatively short, she played a significant role in stopping Japanese expansion and turning the tide of the war during the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway.

*****

Suggested Reading

- Naval Aviation

- Surface Navy

- Early Naval Raids

- H-Gram 005-2: Carrier versus Carrier (Us versus Them)

- H-Gram 005-3: Battle of the Coral Sea

- USS Yorktown (CV-5) Action Report

- H-Gram 006: Battle of Midway 75th Anniversary

Artifacts

- Styrofoam Cup from USS Yorktown (CV-5)

- Decorated Egg from USS Yorktown (CV-5)

- Sword belt buckle from Rear Admiral Harry Guthrie

Interviews with USS Yorktown (CV-5) Crewmembers

- Norman J. Jeansonne

- Francis L. Thompson

- Huron J. Roy

- James E. Patterson

- Willard E. Glidewell

- William A. Stokesberry

- Harold O. Davies

Infographic

Selected Imagery

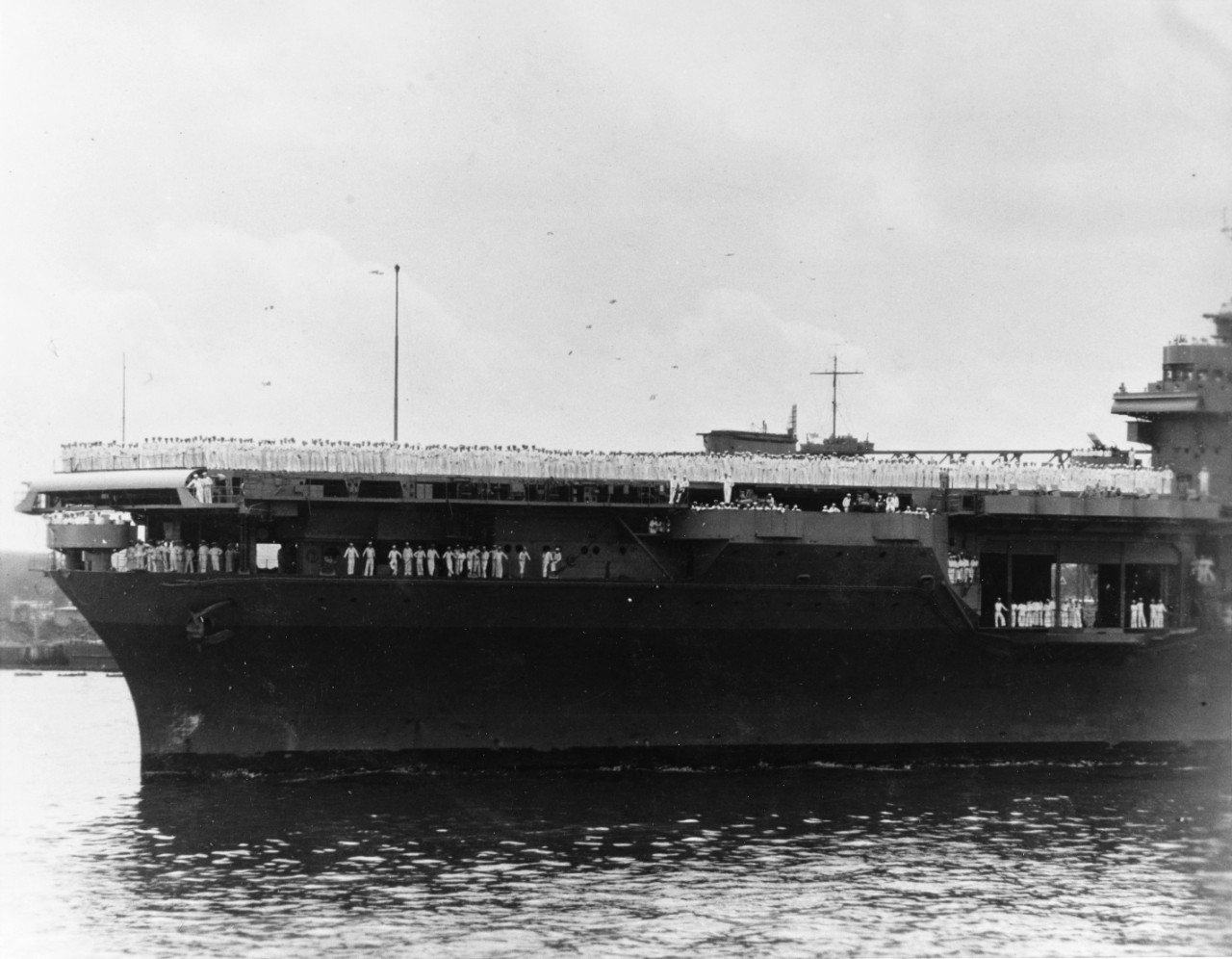

Lieutenant Milton Ernest Ricketts was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for heroism during the Battle of the Coral Sea, 8 May 1942. He was in charge of a USS Yorktown (CV-5) damage control party that suffered many casualties from a bomb explosion. Despite mortal wounds, Ricketts deployed a fire hose and successfully contained a potentially devastating fire before he succumbed to his injuries. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 95297.

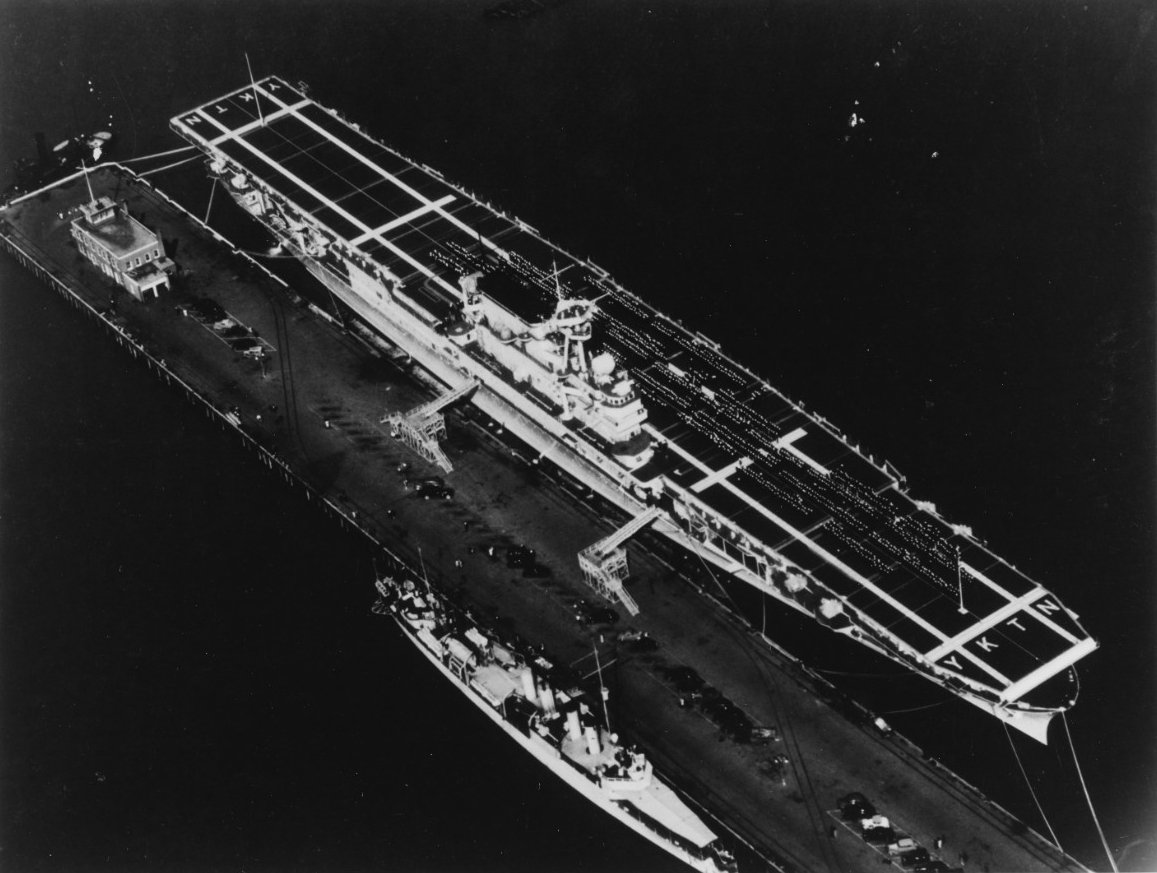

Two Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless scout bombers of Scouting Squadron Five (VS-5) flew past USS Yorktown (CV-5) during operations in the Coral Sea, circa April 1942. Planes parked on the flight deck, in the foreground, are Grumman Wildcat fighters of Fighting Squadron 42 (VF-42). National Archives photograph, 80-G-11664.