Commissioning Pennant

The commissioning pennant is the distinguishing mark of a commissioned Navy ship. A commissioning pennant is a long streamer in some version of the national colors of the navy that flies it. The American pennant is blue at the hoist, bearing seven white stars, and the rest of the pennant consists of single longitudinal stripes of red and white. The pennant is flown at all times as long as a ship is in commissioned status, except when a flag officer or civilian official is embarked and flies his personal flag in its place.

Ships' commissioning programs often include the story of the origin of the commissioning pennant. As it goes, during the first of three, seventeenth-century, Anglo-Dutch naval wars (1652-54), Dutch Admiral Maarten Tromp put to sea with a broom at his masthead to symbolize his intention to sweep the English from the sea. British Admiral Robert Blake two-blocked a coachwhip to show his determination to whip the Dutch fleet. Blake won and in commemoration of his victory a streamer-like pennant, called a “coachwhip pennant” from its long, narrow form, became the distinguishing mark of naval ships.

This is an interesting anecdote. As with so many other stories, though, nothing has ever been found to prove it. Researchers in England have tried to verify the tale, but without success. The actual origin of the commissioning pennant appears to be a bit more prosaic.

Narrow pennants of this kind go back several thousand years. They appear in ancient Egyptian art and were flown from ships’ mastheads and yardarms from at least the Middle Ages; they appear in Medieval manuscript illustrations and Renaissance paintings. Professional national navies began to take form late in the seventeenth century. All ships at that time were sailing ships, and it was often difficult to tell a naval ship from a merchantman. Navies began to adopt long, narrow pennants to be flown by their ships at the mainmast head to distinguish themselves from merchant ships. This became standard naval practice.

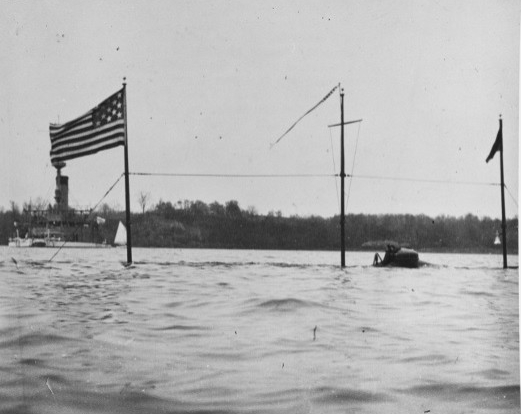

Earlier American commissioning pennants bore 13 white stars in their blue hoist. A smaller, seven-star pennant was later introduced for use in the bows of captains’ gigs, and was flown by the first small submarines and destroyers. This principle even carried over into the national ensign; bigger ships flew the conventional flag of their time, while small boats used a 13-star "boat flag" that was also flown by early submarines and destroyers since the standard Navy ensigns of that day were too big for them. The 13 stars in boat flags and in earlier pennants doubtless commemorated the original 13 states of the Union. The reason behind the use of seven stars is less obvious and was not recorded, though the number seven has positive connotations in Jewish and Christian symbology. On the other hand, it may simply have been an aesthetic choice on the part of those who specified the smaller number.

Until the early years of this century flags and pennants were quite large, as is seen in period pictures of naval ships. By 1870, for example, the largest Navy pennant had a 0.52-foot hoist (the maximum width) and a 70-foot length, called the fly; the biggest ensign at that time measured 19 by 36 feet.

As warships took on distinctive forms and could no longer be easily mistaken for merchantmen, flags and pennants continued to be flown but began to shrink to a fraction of their earlier size. This process was accelerated by the proliferation of electronic antennas through the twentieth century. The biggest commissioning pennant now has a 2.5-inch hoist and a 6-foot fly, while the largest shipboard ensign for daily service use is 5 feet by 9 feet, 6 inches (larger "holiday ensigns" are flown on special occasions).

Selected Documents:

The Traditions of Ship Commissionings

Ship Launching and Commissioning