The Formative Years of the U.S. Navy Medical Corps, 1798−1871

by André B. Sobocinski, Historian, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED)

Introduction

For over 150 years,1 the U.S. Navy has recognized 3 March 1871 as the anniversary of its corps of physicians (i.e., the Medical Corps). An important date in the annals of Navy medicine to be sure, but this date does not represent the advent of uniformed physicians in the Navy nor the start of the Navy Medical Department. Rather, the passage of the Appropriations Act on 3 March 1871 elevated the status of Navy physicians, granting them rank relative to their line counterparts,2 acknowledging their role as staff corps, and establishing the title of “surgeon general” for the Navy’s top medical officer/head of the Navy Medical Department.

The 153 physicians serving in the Navy on 3 March 1871 would not have considered themselves plank owners.3 Unlike the birthdays of the Hospital Corps (17 June 1898), Nurse Corps (13 May 1908), Dental Corps (22 August 1912), and Medical Service Corps (4 August 1947), the legislation did not establish this corps of physicians. And certainly, some of the senior physicians serving in 1871 could boast of careers extending back over 40 years into the first years of Navy medicine.

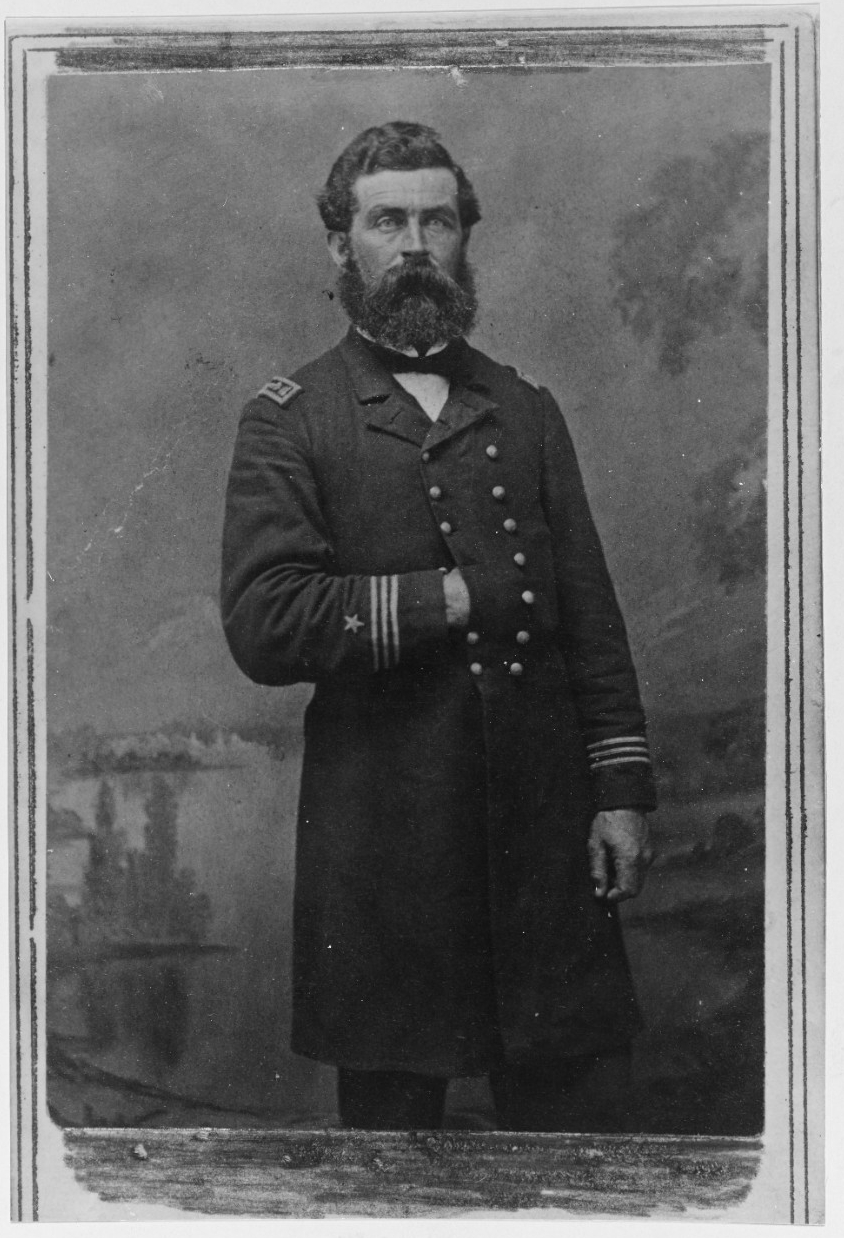

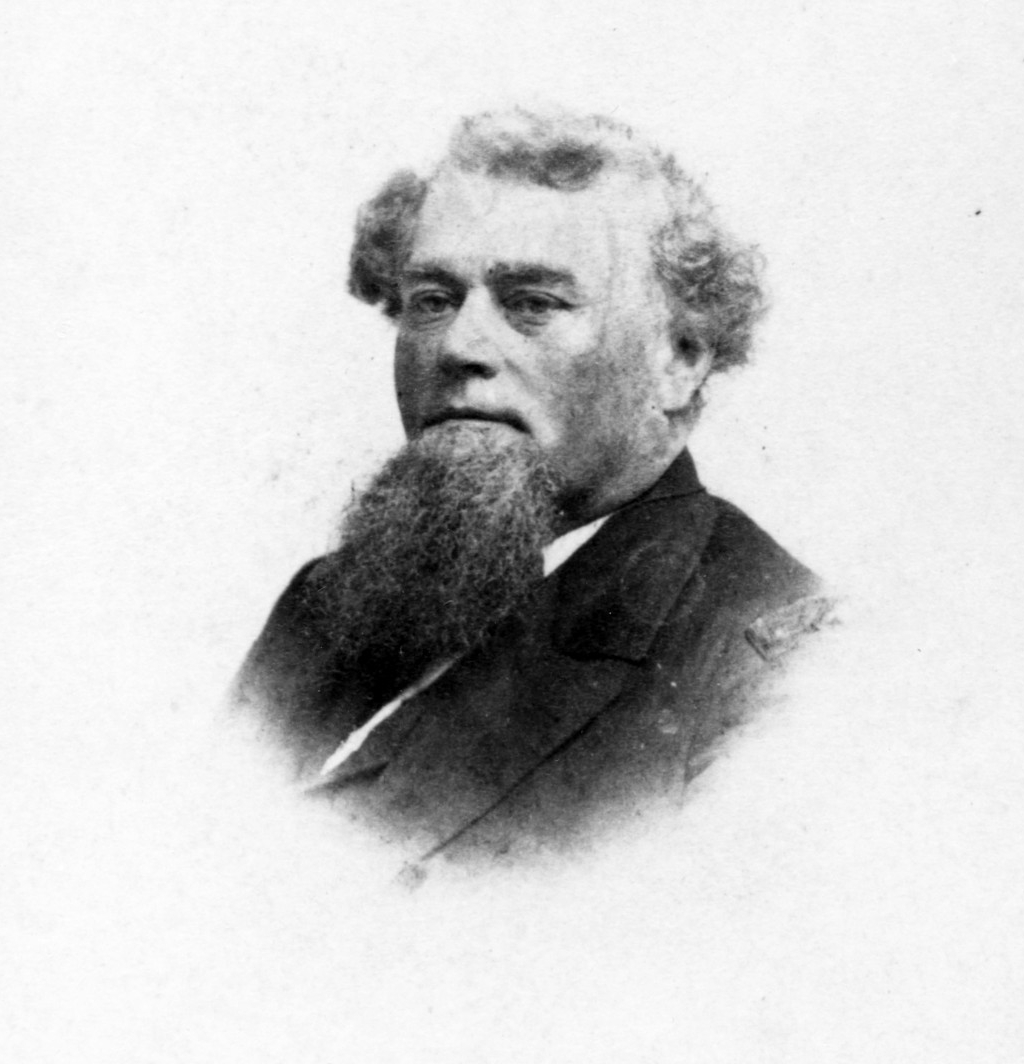

- The first surgeon general, Commodore William Maxwell Wood, was commissioned an assistant surgeon in the Navy in 1829. After a career that included service in the Seminole Wars and Mexican-American War, Dr. Wood served as fleet surgeon for the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. President Grant appointed him Chief BUMED in July 1869. Less than two years later he became the Navy’s first surgeon general.4

- Jonathan Messersmith Foltz was commissioned an assistant surgeon in the Navy in 1830. In a long and distinguished career, Foltz stood in the midst of many bloody wars and skirmishes from the 1832 battle against the Malay pirates to service in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. His life was also colored by his numerous friendships, which included Edgar Allen Poe; Samuel F.B. Morse; and Admiral David Farragut, for whom he served as fleet surgeon during the Civil War. At the close of his career, in 1872, Foltz was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant as Navy Surgeon General (becoming only the second person to hold this title).5

- James Croxall Palmer joined the Navy in 1834. He served as assistant surgeon aboard the frigate Brandywine and then the sloops-of-war Vincennes during the ship’s circumnavigation of the globe. He accompanied the Wilkes Exploring Expedition to the Antarctic (1838-1842). He later was surgeon aboard the steam frigate Niagara when that vessel helped lay the first Atlantic cable. During the Civil War, Dr. Palmer was fleet surgeon of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and was with Farragut at the Battle of Mobile Bay.6

The First Physicians in the U.S. Navy

The U.S. Navy Department was formally established on 30 April 1798. This was years after the Naval Act of 1794 that authorized the first ships of the service and 24 years after the Continental Navy was established by Congress.

Physicians played a vital role in the Continental Navy and its successor U.S. Navy caring for injuries, controlling bleeding, removal of gunshots, performing amputations, setting fractures, and administering the usual assortment of medicines and tonics.7 Both in the Continental Navy and first years of the U.S. Navy, physicians served in two categories—surgeons and surgeon’s mates. Surgeons were typically more experienced physicians prior to their entry and more likely (but not required) to hold medical degrees. Surgeon’s Mates were typically less experienced, junior to surgeons, and rated just above the rate of warrant officer.8

In March 1798—just a month before the U.S. Navy was formally established—the first physicians began reporting aboard the first warships of the U.S. Navy. On 9 March, four surgeons and two surgeon’s mates appears on the roles of three frigates.

Aboard Constellation, Surgeon George Balfour and Surgeon’s Mate Isaac Henry reported for duty. Balfour was a 26-year-old Virginian and a son of a Scottish merchant who served under General Anthony Wayne at Fort Presque Isle. Henry was a 25-year-old Philadelphian who studied medicine under America’s most famous physician, Benjamin Rush, and later operated a medical practice in Centerville, Kentucky.9 Both Balfour and Henry were aboard Constellation in 1799 during her famous engagement with the French ship Insurgente, becoming the first naval physicians to serve in combat.10

Chasing the French ship Insurgente on 9 February 1799. Constellation overtook the French ship Insurgente. The capture of the frigate by Constellation off the island of Nevis was the most notable event of the war. As the first battle test of the new frigates of the U.S. Navy, the victory was very well taken. (NH 56893)

On board United States, Surgeon George Gillaspy of Philadelphia, and Surgeon’s Mate John Bullus, appear in 1798. Bullus was a British-born Philadelphian who operated private practice in Reading, Pennsylvania, prior to his commission. While in service, Bullus earned distinction as one of the first practicing naval physicians in the city of Washington as well as the first Navy physician to provide medical care to a sitting president (1801).11

Aboard Constitution Surgeon William Read and Surgeon’s Mate Charles Blake reported for duty on 9 March. Blake’s career in the Navy would be short. While serving aboard the ship, Blake fractured his sternum and three ribs during a gale. The severity of his injuries forced Blake to resign his commission in 1799.12

Over the course of the Quasi-War with France (7 July 1798−30 September 1800), some 90 surgeons and surgeon’s mates provided medical care aboard 54 warships to several hundred officers and over 5,000 enlisted personnel.13 They applied their best medical skills without the luxury of antibiotics, anesthesia, knowledge of germ theory, or support of trained nurses or dentists. Medicine in the early days aboard warships like Constitution and United States was surgery, bloodletting, blistering, and application of the usual assortment of anodynes, antiarthritics, astringents, cathartics, emetics, diaphoretics, diuretics, rubefacients, stimulants, and tonics typically found in a shipboard surgeon’s medical kit at the time (most of which were perfectly equipped to induce a host of iatrogenic disorders!).

Calomel (mercury chloride) and jalap (a poisonous root) were commonly used to stimulate the intestinal tract and rid intestinal irritation. Peruvian bark (later known as quinine) was used in the treatment of malaria and other malignant fevers. Potassium acetate was used to increase secretion and flow of urine. Opium and laudanum were used to relieve pain and induce sleep. Teas and tonics were commonly used to settle digestive complaints.14

From the very beginning combatting disease was a significant part of the job—and yellow fever and malaria fever remained a significant problem that Navy physicians contended with for much of the next century, especially on deployments to the tropical climates of the West Indies, and Central and South America. Early Navy medical logs from Navy ships deployed to tropical climates are full of cases of “Ague,” “Fever and Ague,” “Bilious Fever,” “Inflammatory Fever,” “Intermittent Fever,” “Remittent Fever,” and “Putrid, Malignant Ship Fever”—all archaic terms for mosquito-borne illnesses.

The story of the armed merchant ship Delaware offers an example of the impact mosquitoes had in the Quasi-War. On an unseasonably warm day in December 1799, Delaware limped into the port of Curacao with its crew incapacitated with “fever.” Over the next month some 130 members of the ship’s complement—a staggering 72 percent of the crew!—was infected with this fever. The ship’s physician, Surgeon’s Mate Samuel Anderson, described attending to patients under a stale air punctured by the “offensive effluvia” of bilge water. This was an age when some diseases were still associated with atmospheric conditions, noxious vapors, and “miasma” (literally “pollution” or “bad air”).

Anderson established a temporary hospital on shore where his patients were exposed to more “salubrious conditions” and subject to the standard practices of the day—a combination of purgatives and bloodletting. Although the concept of germ theory and the idea of mosquito-transmitted diseases were still several decades away, Anderson came very close to identifying the cause of the malady. He prophetically noted that among his patients: “Eruptions of various kinds appeared. That which was most common and struck my attention most, was in every respect similar to musquitoe [sic] bites.”15

Notable Medical Pioneers of the Early Navy

Among the early titans of the Navy Medical Department was Surgeon Edward Cutbush. The Philadelphia-born Cutbush was commissioned in the Navy on 28 May 1799 after service as a “hospital surgeon” in the Pennsylvania Militia. Soon after succeeding Gillaspy aboard United States, Cutbush inoculated the Sailors against small pox—marking the first time an inoculation was performed aboard a U.S. Navy ship. Later, while serving aboard President during the Barbary Wars, Cutbush established (and oversaw) the Naval Hospital Syracuse in Sicily, the first overseas hospital in use for the wars with the Barbary States.16

In 1808, Cutbush published Observations on the Means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors, one of the first American textbooks on military medicine. Cutbush proposed techniques for cleaning, disinfecting, and ventilating ships; he advocated for strict physical examinations of all recruits coming aboard in order to eliminate disease; and promoted standards of hygiene, which included having Sailors wear their hair short, shave regularly, and to wash themselves and their clothing.17

Jonathan Cowdery (1767−1852)

Jonathan Cowdery of Sandisfield, Massachusetts, entered the Navy as a surgeon’s mate in 1800. Cowdery had learned medicine through apprenticeship and practiced medicine in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont before becoming the senior most surgeon’s mate in the Navy. Assigned to the frigate Philadelphia, he was aboard the ship when it ran aground on an uncharted reef near Tripoli Harbor. Cowdery was captured by the Tripolitan pirates along with Surgeon Jonathan Ridgeley, Surgeon’s Mate Nicholas Harwood, and Loblolly Boy18 John Domyn. While in captivity, Cowdery interceded on behalf of the other American prisoners, cared for them, and saved the life of one of the Pasha’s children. Cowdery’s journal was published in 1806 and to this day remains one of the best accounts of the Barbary Wars.19

Cowdery’s fellow New Englander, Usher Parsons, obtained his commission in the Navy in July 1812, and it would not be long before the Navy physician provided his mettle in combat.

On 10 September 1813, while serving as the medical officer aboard Lawrence at the Battle of Lake Erie, Parsons treated over 100 patients. The following is an excerpt of his account of these experiences.

“In this weakened condition,20 with only one doctor in the squadron to attend the sick and take charge of the wounded of a battle, we met the enemy (September 10, 1813). The action was soon very severely felt on board the Lawrence, the largest vessels of the enemy engaging her at short distance for nearly two hours. The Lawrence being shallow built and affording no cock-pit, or place of security for the wounded, they were received on the ward-room floor, which was nearly level with the surface of the water. Being only ten or twelve feet square, this floor was soon covered, which made it necessary to pass them out into another apartment, as fast as the bleeding could be staunched. Several, however, were wounded a second time before this could be done. Midshipmen Laub was moving from me with a tourniquet on his arm, when a cannon ball struck him in the breast; and a seamen brought down with both arms fractured was struck by a cannon ball in both legs. An hour and a half had so far swept the deck that new appeals for surgical aid were less frequent. This change was rendered the more desirable at this time, from the circumstance that the repeated request of the commodore to spare him another man had taken from me the last one stationed to assist in moving the wounded; in fact, many of the wounded themselves took the deck at this critical moment.

Having sole charge of the wounded of the whole fleet, and the wounded being passed down to me for aid faster than I could attend to them in a proper manner, I aimed only to save life during the action by tying arteries or applying tourniquets to prevent fatal hemorrhage, and sometimes applying splints as a temporary support to shattered limbs, etc. In this state the patients remained until the following morning, under the free use of cordials and anodynes. At sunrise (the 11th), I began amputations, and in the course of the whole day and evening was able to finish all operations and dress at least once or twice, and to do justice to them all. On the following day, I visited the other vessels and brought all the wounded on board the Lawrence and treated them in like manner.”21

William Paul Crillon Barton (1786−1856)

Dr. William Paul Crillon Barton was commissioned in the U.S. Navy in 1809. In his lengthy career—which extended until his death in 1856 —Barton published some of the first writings on hospital administration in the military; help to prohibit alcohol rations aboard Navy ships; and finally serving as the first chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (1842−1844). While on active duty, Barton also served tenures as professor of botany at the University of Pennsylvania and at Thomas Jefferson Medical College, respectively, and set forth on an ambitious project to document American plant life. In the process, Barton compiled several compendiums of American plants, including Flora Philadelphiae Prodromus (1815), Vegetable Materia Medica of the United States (2 volumes, 1817−1825) and Flora of North America (1821−1823); each were standards of botanical science.22, 23

Barton was also one of the leading figures in the U.S. Navy’s fight against scurvy.

Few diseases have been more synonymous with Sailors than scurvy. From the dawn of time, scurvy has been described as the “Black Death of the sea,” and was once even as deadly as smallpox. Yet years after the British Royal Navy successfully demonstrated the treatment and prevention of this affliction through citrus fruit and lemon juice rations the disease continued to plague the U.S. Navy.24

In 1803, the surgeon aboard New York reported that scurvy alone was the chief medical concern aboard his ship stating: “I…think it highly necessary to inform you that from the 23th of October last, the scurvy of a most malignant character & with the highest symptoms has broken out among our ship’s company & increases dayly [sic].”25

The effects of the Vitamin C deprivation could be outright ghastly. In his textbook on nautical medicine, Surgeon Usher Parsons described the manifestation of the scurvy in a Sailor: “The gums become soft, livid and swollen, are apt to bleed from the slightest cause, and separate from the teeth, leaving them loose. About the same time the legs swell, are glossy, and soon exhibit foul ulcers; the same appearances follow, on other depending parts of the body. At first the ulcers resemble black blisters which spread and discharge a dark colored matter…these ulcers increase, great emaciation ensues, bleedings occur at the nose and mouth, all the evacuations from the body becomes intolerably fetid, and death closes the scene.”26

In 1809, Dr. Barton took on the fight against scurvy while aboard United States, then under the command of Commodore Stephen Decatur. Turning to the medical literature out of Great Britain, Barton administered a citrus concoction to the most severely affected crewmembers and cured them of their symptoms.

“I had an opportunity of trying the efficacy of the simple expressed juice of limes, which was liberally allowed on my indent, by commodore Decatur, in eight or nine cases of sea-scurvy, which occurred on board of the frigate United States,” recalled Barton. “Two of these cases were very bad ones. I had the satisfaction to find that I easily checked the disorder by an early and liberal administration of lime-juice, undiluted, three or four times a day, and in the form of lemonade, for drink, at all times.”27

Using these case studies, Barton lobbied the Secretary of the Navy to furnish U.S. Navy ships with what he described as a “clarified lemon-lime ration.” When his correspondence was not answered, he reached out to individual ship captains for their opinions on introducing “antiscorbutic rations” to their crews.

Captain David Porter of Essex assured Barton that he would spread word to his “brother ship captains.”28

Commodore John Rodgers of President commended Barton on his sound judgement, stating, “Your observations relative to the effects of this valuable acid, as a preventive against scurvy; as also of its efficacy in removing from the system that horrid disease, to which seamen (especially after long voyages, when their diet has consisted principally of salted provisions) are particularly liable, I have perused with much pleasure: as well because they serve as a proof that you wish to benefit the service by your experience; as of my conviction of the correctness of what you represent. In the course of my own observation, I have in many instances witnessed the salutary effects of acids, and particularly those of limes and lemons, not only in removing scorbutick [sic] affections from, but in fortifying the system against the disease; and I have not the least doubt, but the most beneficial effects would result by the introduction of lime or lemon juice on board of our ships of war, in the manner you mention; particularly when they are employed on foreign service.”

Despite Barton’s efforts, however, the decision to adopt antiscorbutic rations would remain the hands of individual fleet commanders, ship captains, and their consulting surgeons for well into the nineteenth century. Even if a ship did take necessary preventive measures against scurvy, long deployments could exhaust shipboard provisions leading to a host of nutritional diseases like scurvy.

One of the most well known outbreaks of scurvy took place during the Mexican War in 1846. During the U.S. blockade of Vera Cruz over one fifth of Potomac’s company (over 100 men) were afflicted with scurvy, necessitating the ship’s return to Pensacola, Florida. Raritan and Falmouth would soon after follow Potomac to Pensacola, where they transferred their scurvy-inflicted crews to the naval hospital.29

Remarkably, cases of scurvy would still appear in the medical logs of the U.S. Navy into the twentieth century. In his medical report on scurvy published in the United States Naval Medical Bulletin in 1926, Lieutenant Commander L.J. Roberts, MC, USN, wrote, “With the advancement of knowledge as to its etiology and the means of its prevention its incidence on board steam vessels is now almost negligible and in the United States Navy it is extremely rare…records show that during the period of 30 years, from 1895 to 1924, inclusive, 12 cases of scurvy were reported as occurring in the Navy.”30

Building the Foundations of a Navy Medical Department

Establishing the First Naval Hospitals

From 1811 to 1842 great strides were made in building foundations of what we would call a Navy medical department. A significant part of this was the establishment of naval hospitals.

In the early years of Navy medicine, “hospitals” were often located on or near Navy yards along the Eastern seaboard. At best, they were makeshift facilities offering a modicum of care; at worse they were simply shelters from the elements. Surgeon William P.C. Barton, an early proponent for upgrading hospitals, described one such hovel, “I have myself seen a number of sick seamen with whom I was left in charge at the Navy Yard, Philadelphia, where they were necessarily huddled into a miserable house, scarcely large enough to accommodate the eight part of their number—a spirit of impatience and even of revolt…so wretched was the hovel and so destitute every necessary comfort for sick persons…[that] every man who gathered sufficient strength and was successful in getting an opportunity to effect his escape, absconded immediately.”31

On 26 February 1811, the Navy took its first giant leap forward in the cause of hospitalization of its Sailors and Marines. On this day, Congress approved an act establishing the first permanent Navy hospitals. The Act directed that the Secretaries of the Navy, the Treasury, and War (Army) serve as “Commissioners of Navy Hospitals” and the unexpended balance of the Marine Hospital Fund32— be placed at their disposal for construction of permanent Navy medical facilities.33 In addition, contributions of twenty cents a month by each naval officer and Sailor would be used to bolster the fund now known as the “Navy Hospital Fund.”

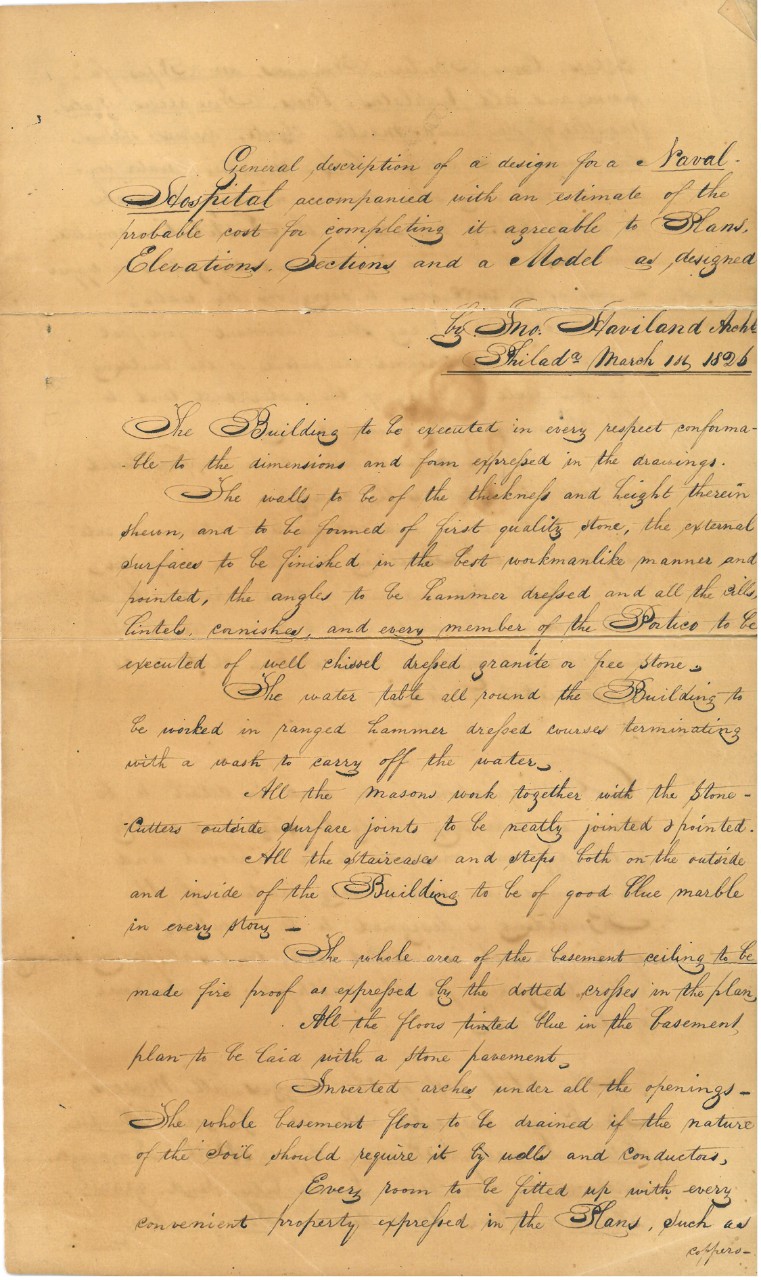

Ten years lapsed before the Commissioners of Navy Hospitals selected the location of the first hospital site in Washington, D.C. (1821). This was followed by the purchase of other sites in Chelsea, Massachusetts (1823); Brooklyn, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (1826); and Norfolk/Portsmouth, Virginia (1827). Some of America’s greatest architects including William Strickland and America’s preeminent prison designer John Haviland were hired to design these new platforms of the Navy Medical Department. The first hospital opened in 1830 in Portsmouth, Virginia, followed soon after by Naval Hospital Philadelphia (a.k.a., located at the “Naval Asylum.”34

As important as establishing a platform for medical care was developing a program to indoctrinate newly commissioned naval physicians.

New Standards and Creating an Identity for Navy Physicians

The passage of the Naval Act of 24 May 1828, (a.k.a., The Better Organization of the Medical Department of the Navy) helped elevate the standards for entry into the Navy Medical Department and expanded the rank structure. The act required all prospective physicians applying for commissions and all physicians seeking promotion to stand before a medical board of examiners who would judge their knowledge, character, and medical acumen.35

Under the act, the rank of surgeon’s mate was replaced with “assistant surgeon.” All prospective physicians who passed the Medical Board were now appointed as assistant surgeons. Assistant surgeons who served at sea “on board a public vessel of the United States, at sea” were permitted to report before the board for promotion to surgeon. Those who passed the examination, but were awaiting a vacancy were called “passed assistant surgeons.”

This same act also created the title of “surgeon of the fleet,” which authorized the president to designate and appoint to every fleet or squadron an “experienced and intelligent surgeon, then in the naval service.”36 The fleet surgeon was to serve in the flagship and be generally responsible for all medical matters within the fleet or squadron.

After 1828, all physicians seeking commissions in the Navy were required to have medical degrees and show proficiency in anatomy, chemistry, material medica, medical jurisprudence, and midwifery before the medical board. As a fact, this may seem unremarkable to us today. It is only by peering through the scope of yesteryear, and looking upon a world where the “M.D.” and medical specialty were precious rarities among practicing “physicians,” that these exceptions become all the more exceptional.

These elevated admission standards ensured that many Navy surgeons were among the elite of their profession, but this did not guarantee that these newly commissioned officers were necessarily ready for the challenges posed by practicing medicine at sea or ashore. In 1823, Surgeon Thomas Harris took it upon himself to solve this riddle. His solution was a special medical course that offered prospective medical officers the means to pass entrance exams into the Navy, give junior medical officers the knowledge that would get them promoted, and most importantly, offer a rudimentary instruction in what we may call “operational medicine.”

A naval medical officer at sea would have to contend with hosts of tropical and venereal diseases, including syphilis and gonorrhea. They treated the occupational hazards and wounds typical for ships of the day. And in wartime, their exhaustive workload could grow with battle wounds, requiring surgical skills.

The newly minted assistant surgeon had no recorded institutional memory to study or briefing books to read. The practice of Navy medicine was learned on service with the African, East Indian, European, Mediterranean, and West Indian squadrons. Surgeon Harris understood this like few others. He earned his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1809. After graduation, he operated a small medical practice in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, before joining the Navy in 1812. Dr. Harris could tell tales of the War of 1812—of service aboard sloop-of-war Wasp, and her celebrated engagements with HMS Frolic and HMS Poictiers. His wartime experience extended into the Second Barbary War (a.k.a., Algerian War), where he served in Commodore Stephen Decatur’s Mediterranean squadron. It is said that his surgical skills were honed amputating gangrenous and crippled limbs of Sailors and Marines with utmost “judgment, coolness, readiness, and dexterity.”37

Dr. Harris returned stateside in 1817 and back to Philadelphia, where he served first at the Navy Yard, and later at the Naval Asylum. Other than a brief tour of duty to Key West, Florida, in 1823, Harris spent twenty-seven continuous years of active duty in the Quaker City. When duties allowed, Harris maintained a private surgical practice, which proved so prosperous that it was reported that he obtained a level of personal income “that has seldom been reached in Philadelphia.”38, 39

In 1823, Harris used his “personal” income to establish a dissection laboratory to teach medical students, and specifically Navy medical officers anatomy and operative surgery, and share his wartime medical experiences. This educational experiment proved such a success that Harris was encouraged by his students to “give the course under government auspices.”40

On 10 May 1823, Surgeon Harris wrote to Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson that, “Many of the Surgeon’s Mates, as well as younger Surgeons of the Navy, manifest, at present, a very laudable anxiety to acquire an intimate knowledge of their profession. As their slender pay deprives them, however, of the necessary means of instruction, the fostering assistance of government is respectfully solicited. For this purpose they are desirous that you would afford such of them as are not on public duty, an opportunity of hearing lectures on nautical medicine, and military surgery, as well as pursuing a course of dissections under some one, whom you may deem competent to this duty.”41

Dr. Harris suggested that he could oversee the studies of medical officers, provide them access to his personal library of medical books, “superintend” their dissections, and direct their instruction of anatomy. Harris wrote that “Navy Surgeons are not presented with the means of continuing their pursuits in this manner, after entering the public service; and it is not an infrequent occurrence that the first time they pass the details of an operation is on a patient, when it must be necessarily attended with embarrassment and awkwardness. The evils which must result on many occasions from circumstances of this kind, and the advantages to the service of measures that would be so apparent, that I feel persuaded of your friendly disposition to the measure proposed.”42

On 19 May 1823, Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson responded, “The plan you propose for the improvement of the Surgeon’s Mates and younger Surgeons of the Navy in the different branches of their profession offers to be productive of much utility to the public service & receives my entire approbation.”43

Thompson authorized 400 dollars, which would, in course, serve as the school’s annual budget. In return for the allowance, Harris was required to submit an annual report to the Secretary of the Navy and forward his vouchers to the Treasury Department for payment.

Under Harris’s tutelage, Navy doctors were exposed to the latest in civilian medical thinking as well as firsthand knowledge of practicing medicine in the fleet. Harris’s course had achieved great popularity among his pupils. One student remarked, “We have never heard a better practical lecturer. His style is familiar, sometimes conversational, and his matter has the great attraction of appearing to emanate more from his experience than the gleanings of books.”44

In 1834, Acting Secretary of the Navy John Boyle responded to Harris’s annual report, “It is highly gratifying to discover that the lectures are so well attended by the medical officers of the Navy. The zeal, alacrity, and industry with which their studies are prosecuted, cannot fail to produce to the service lasting and beneficial results.45

Harris continued to receive funding until 1843, just a year after the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery was established. The new Chief of BUMED—and old rival of Thomas Harris, Surgeon William P.C. Barton—reported to the Secretary of the Navy Abel Upshur that the money Harris was allotted for his course never received legislative sanction. Upshur wrote to Harris on 31 January 1841 that “While, therefore, you have faithfully performed your trust, I feel obliged to discontinue the allowance as unauthorized by law.”46 It would take another thirty years before the experiment in Navy medical education was taken up again.

Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) and Procuring Medical Supplies for the Navy

Throughout much of the early 1800s. Navy medicine was an organization without a central administrative hub. All of this changed on 31 August 31 1842, when the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) was one of five bureaus established by Congress to administer the activities of the U.S. Navy. The General Order of November 26, 1842, charged BUMED with:

- all medicines and medical stores of every description, used in the treatment of the sick, the diseased and the wounded;

- all boxes, vials, and other vessels containing the same;

- all clothing, beds, and bedding for the sick;

- all surgical instruments of every kind;

- the management of hospitals, so far as the patients therein are concerned;

- all appliances of every sort, used in surgical and medical practice;

- all contracts, accounts, and returns, relating to these and such other subjects as shall hereafter be assigned to this bureau.

There is no denying that BUMED’s founding contributed significantly to the Medical Department’s development and efficiency. This cause was helped in September 1842, when President John Tyler appointed William Paul Crillon Barton BUMED’s first chief and the titular head of Navy medicine.

Barton was succeeded by Thomas Harris in 1844, who was succeeded by William Whelan in 1853. Whelan was succeeded in turn by Phineas Horwitz in 1865. A principal issue for BUMED’s Chiefs in those nascent years was the procuring and administering medical supplies for ships and hospitals.

In the 1840s, at each naval yard, a specially designated purveyor was responsible for outfitting ships and medical facilities with medical stores. When a vessel returned to the yard, the purveyor inspected the Navy surgeon’s account books and determined what was used, what could be reutilized, and what needed to be reordered. All losses in the Navy Medical Department that could not be accounted for were deducted from the pay of the surgeon and his assistants. Medical supplies were typically allocated based on a supply table that had first been developed in 1818.

Although well meaning, this system was anything but flawless as many Navy surgeons duly noted in their correspondence with the Secretary of the Navy. Ships were not always supplied with adequate or good quality medicines and purveyors relied on contracts with local druggists and other manufacturers who could exhibit less than scrupulous tendencies. Navy contracts were always awarded to the lowest bidder and there was no way of assessing the quality of the product or trustworthiness of contractor beforehand.

In August 1845, Surgeon William Ruschenberger, then senior medical officer at Naval Hospital Brooklyn, discovered that the hospital had been running low on laudanum (tincture of opium), which was used for treating pain as well as a cough suppressant. Taking the pint-sized bottle with him, he visited the Brooklyn druggist who had been contracted for supplying the medicine. Ruschenberger’s request for a refill was met by the question, “Do you get the shilling or two shilling laudanum?”

According to Ruschenberger that simple response led him to outfitting Naval Hospital Brooklyn with the tools for preparing their own quality medicines. The work of this hospital laboratory continue under Ruschenberger’s successor, Surgeon Water Smith, in 1847 and ultimately under Benjamin Franklin Bache47 beginning in September 1850.

Surgeon Bache came to Brooklyn, New York, to serve as the officer in charge48 of what in 1850 was the largest and arguably the busiest of the Navy’s hospitals. In addition to being located in one of the most active shipyards in the nation, Navy Hospital Brooklyn was unique in that it was the only naval hospital that operated a small laboratory where medicines in short supply could be manufactured for use on the wards.

As the new head of the hospital, Bache brought 26 years of naval experience49 which included tours as fleet surgeon for the Mediterranean (1841−1843) and Brazilian Squadrons (1843−1844, 1847−1850).50 Over the next few years, Bache worked diligently on expanding the laboratory’s scope and mission. In addition to manufacturing the hospital’s pharmaceuticals, it began supplying much-needed medicines to the entire fleet; testing and analyzing the quality of medical supplies obtained from contractors; and training newly commissioned medical officers in laboratory techniques and chemical analysis.

With the backing of BUMED and the Secretary of the Navy, the hospital laboratory was formally established as a unique command under Bache’s helm in 1853 and was now referred to as the “Naval Laboratory.” Bache dedicated himself to finding improved ways on how the Navy purchased supplies and drugs even, as it would later be written, confronted many individuals who “hoped to profit from the unlawful schemes of the contract system.” He used the laboratory to analyze the samples provided by contractors and compared them to what was delivered. In turn, he discovered that the government was often getting the “raw end of the deal.”51

Bache was not alone in this crusade, and the Naval Laboratory was fortunate to have a young Assistant Surgeon named Edward Squibb join its staff in 1852. The Delaware-born Squibb, a former apothecary-apprentice turned physician, had been a student of Bache’s cousin, Dr. Franklin Bache, while at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. He had also served briefly under Bache in the Mediterranean Squadron.

In the 1850s, Bache and Squibb began looking at the medical chests typically furnished to ships and removing all drugs that were determined to be antiquated and/or ineffectual. They also began compiling prices for the remaining drugs, and drew up estimates for manufacturing costs at the Naval Laboratory. This works would result in cost savings as well as the issuance of the Navy’s first medical supply table in nearly 40 years (1857). The tables were modified thereafter with some regularity with updates appearing in 1863, 1864, 1867, 1873, and 1878.

In the spring 1853, Bache authorized Squibb to research new methods for manufacturing and supplying ether. Ether was a much in-demand anesthetic that many physicians avoided due to the inconsistency of quality, and the crude and difficult means of distilling it. Squibb would use the Naval Laboratory’s facilities to devise a new method for distilling a very pure quality of ether by using steam.52, 53

William Whelan, Navy Medicine, and the Civil War

Surgeon William Whelan has been credited for his support of the medical innovations that took place in Brooklyn, while serving as Chief of BUMED. Whelan had entered the Navy in 1828 and served at the Naval Hospital Chelsea, with the West Indies Squadron and Fleet Surgeon with the Mediterranean Squadron before being appointed the BUMED Chief—a position he ultimately held until his death on 11 June 1865. Arguably, his most significant challenge was presiding over Navy Medicine during its largest period of growth (up to that point) in the Civil War.

Navy Medicine grew in the Civil War to meet the massive challenges posed by disease and warfare. The U.S. Navy lost 2,112 Sailors in combat and 2,550 to disease in the Civil War.54 Throughout the war, the Navy treated over 31,000 patients. To meet the new patient loads, Whelan had the three largest hospitals (Brooklyn, Chelsea, and Philadelphia) expanded. New hospitals were constructed in Memphis, Tennessee; Mound City, Illinois; New Bern, North Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Port Royal, South Carolina. Navy Medicine employed new platforms like the hospital ship Red Rover and turned increasingly to support personnel like apothecaries, enlisted medical Sailors (surgeon stewards and male nurses), and volunteer female nurses.55

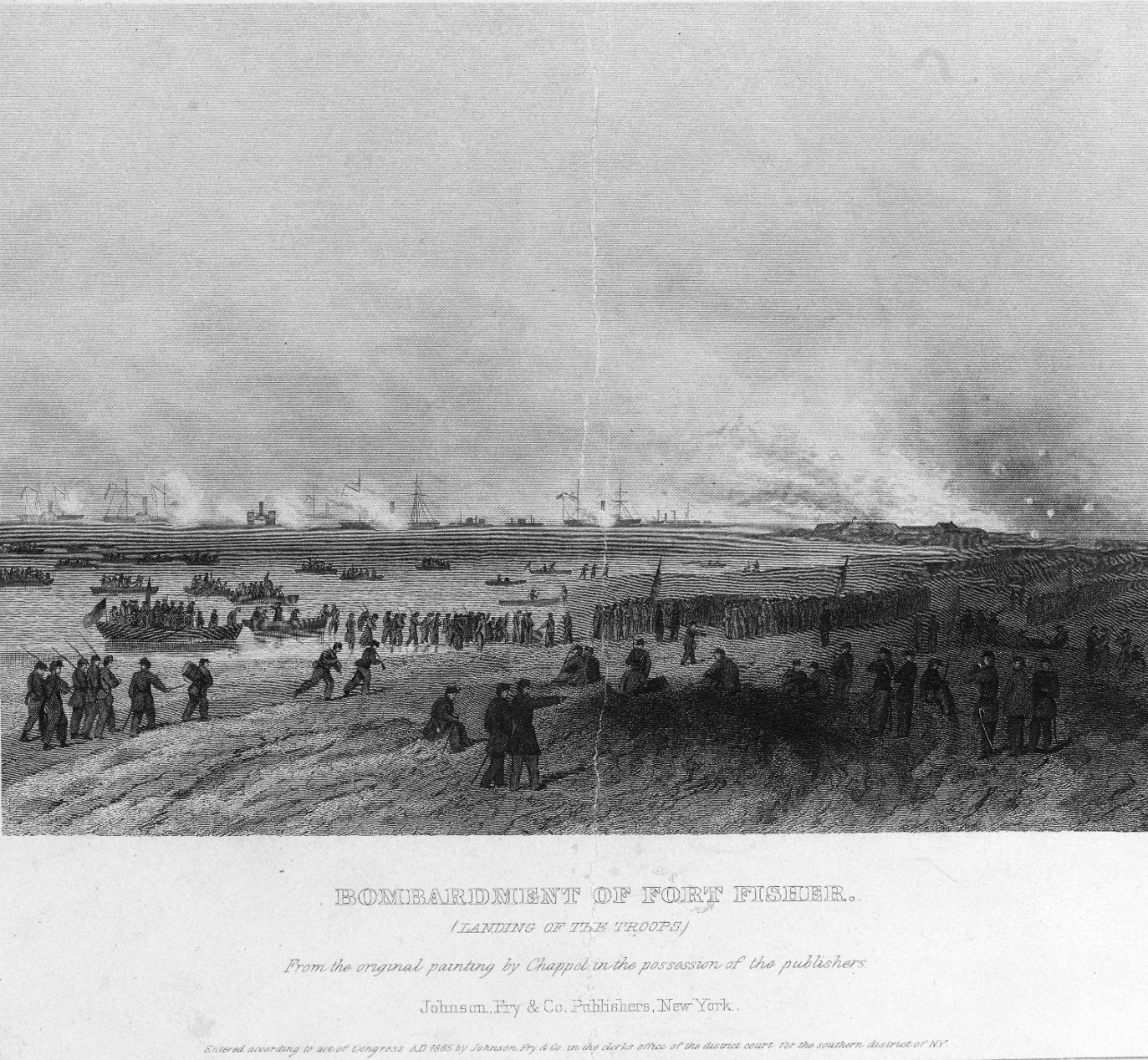

Navy physicians could be found at sea with the blockading squadrons, at hospitals ashore, but also embedded with landing parties. In January 1865, Navy physicians supported an amphibious assault on Fort Fisher overseeing aid stations, serving on the warships offshore, and even charging alongside Sailors and Marines in the attack on the Confederate bastion. Among those tending to the wounded at the risk of his own life was a 25-year-old Navy physician named William Longshaw whose selflessness and bravery was noted by many. Longshaw’s final act would be binding the wounds of a Marine before making the ultimate sacrifice.56

Civil War Navy physicians would also play an important role in overseeing the diet of Sailors.

On 25 July 25 1862, following reports of sickness and low morale, Fleet Surgeon William Maxwell Wood was ordered by the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles to conduct a medical and sanitary inspection of the James River Flotilla.57

Traveling aboard the side-wheel tug Satellite, Wood visited the principal vessels of the flotilla, met with their commanding officers and medical complements. He found diarrhea, dysentery, scurvy, and typhoid to be prevalent among the ship’s companies, and no suitable shipboard accommodations for the sick. The chief complaint among the ship’s Sailors, however, was the lack of fresh provisions and vegetables. As Wood noted, “Those vessels that have been in the river longest have had this kind of diet but once in three months.” Wood recommended that supplies be furnished twice a week going on to state that, “Even though the material effect of this change of ration might not be certain, the moral effect upon men engaged in this depressing service of having the food that they prefer, would be of a sanitary character.”58, 59

Following the war, Wood served on temporary duty as part of the Medical Examination Board. In 1869, he succeeded Surgeon Phineas Horwitz as the Chief of the Bureau. On 3 March 1871—with the passage of the Appropriations Act—Wood earned the distinction as the first Surgeon General of the Navy. He continued to serve in this role until 25 October 1871. Over the course of his career, Wood had witness the Medical Corps come into its own from the establishment of standards, advent of relative rank, formation of administrative headquarters, and the gradual improvements to medical care owing to an increase emphasis on hygiene.

About the Author:

André Sobocinski is a native of Norristown, Pennsylvania, who has served as the historian for the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) since May 2012. Mr. Sobocinski is the author of over 250 published works on history and culture including “A History of Naval Hospitals,” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History; “World War I Medicine,” Americans at War: Society, Culture, and the Homefront; and co-author of “History of Navy Medicine,” Medics at War.

[1] When the Navy medical planners at the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery selected the date of March 3rd, 1871, they realized the fact unlike its fellow staff corps the Medical Corps was not founded by a single piece of legislation and no perfect date existed. As Surgeon General presiding over what was recognized as the 100th birthday of the Medical Corps in 1971, Vice Adm. George Davis acknowledged the history of Navy physicians had long preceded 1871. In his anniversary address he stated that the purpose of the birthday is an “occasion to acknowledge our great heritage,” “the leadership of those retired members of the corps”, and take the time to improve the “true spirit of healing – its joy, its hope, its satisfaction and the calling towards service,” all of which was the true strength of the corps.

[2] Navy Physicians on March 3, 1871 were now led by a Surgeon General with the rank of Commodore. Medical Directors were equivalent of Captains, Medical Inspectors equivalent to Commanders, Surgeons akin to Lieutenants, Passed Assistant Surgeons equivalent to Ensigns, and Assistant Surgeons were equivalent to Masters.

[3] Patton, W.K. Navy Medical Corps—Its Gestation, Birth and Baptism. U.S. Navy Medical Newsletter, Volume 55, February 1970

[4] Kerr, W.M. William Maxwell Wood: The First Surgeon General of the Navy. Annals of Medical History. Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1924.

[5] Foltz, Charles S. Surgeon of the Seas. The Life of Surgeon General Jonathan M. Foltz. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1931.

[6] Roddis, Louis. James C. Palmer. Military Surgeon, May 1942.

[7] Gordon, Maurice Bear. Naval and Maritime Medicine During the American Revolution. Ventnor, NJ: Ventnor Publishers, 1978.

[8] Patton, p3

[9] Langley, Harold. A History of Medicine in the Early Navy. Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1995, p23.

[10] Holcomb, Richmond. A Century with Norfolk Naval Hospital, 1830-1930. Portsmouth, VA: Printcraft Publishing Co., 1930.

[11] Deppisch, Ludwig. The White House Physician: A History from Washington to George W. Bush. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Press, 2007.

[12] Charles Blake, Report No. 404, March 3, 1836. Pension Records.

[13] Langley, p49.

[14] Sobocinski, A.B. “Under the Lantern Light.” The Grog: A Journal of Navy Medicine History and Culture, Summer 2012.

[15] Sobocinski, A.B. “The Mosquito Fighters: A Short History of the Mosquito in the Navy, Part 1.” NMRC News, April 2016.

[16] Pleadwell, Frank. “Edward Cutbush, The Nestor of the Medical Corps of the Navy.” Annals of Medical History. Paul B.Hoeber, Inc: New York, 1923.

[17] Cutbush, Edward. Observations on the Means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors; on the Duties of the Medical Department of the Army and Navy: With Remarks on Hospitals and their Internal Arrangement. Philadelphia, PA: Thomas Dobson, 1808.

[18] Loblolly Boys were Sailors assigned to assist surgeons and surgeon’s mates in the early days of the U.S. Navy. Considered forerunners of today’s hospital corpsmen, Loblolly Boys got their curious name from the fact that they were assigned to administer a porridge or “loblolly” to the sick and wounded aboard the ship they were assigned.

[19] Cowdery, Jonathan. American Captives in Tripoli: or, Dr. Cowdery’s Journal in Miniature Kept During His Late Captivity in Tripoli, Boston: Belcher & Armstrong, 1806.

[20] Disease was rife aboard the ship prior to the battle.

[21] Account published in the U.S. Naval Medical Bulletin, Washington, D.C., July 1922, p430.

[22] Pleadwell, Frank. “William Paul Crillon Barton (1786-1856), Surgeon, United States Navy—A Pioneer in American Naval Medicine.” The Military Surgeon, March 1920.

[23] Surgeon William Baldwin, USN (1779-1819) was another prominent botanist in the early 19th century. Before his death from tuberculosis, Baldwin traveled through eastern Georgia and Florida collecting botanical specimens and penning detailed descriptions of local flora that would be used by botanist Stephen Elliott in his Sketch of the Botany of South Carolina and Georgia (1821). His botanical observations would be published in the Journal of American Science (1818) and posthumously in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (1825). The thousands of specimens he collected would be distributed for various herbaria and museums throughout the country and be used for study. The respect for Baldwin’s work among fellow botanists was so great that the plant genus Balduina and the Baldwin Herbarium in Philadelphia, PennSylvania, would later be named in his honor.

[24] Roddis, Louis. James Lind: Founder of Nautical Medicine. New York: Henry Schuman. 1950.

[25] Estes, J. Worth. Naval Surgeon: Life and Death at Sea in the Age of Sail. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1998.

[26] Parsons, Usher. Sailor's physician, exhibiting the symptoms, causes and treatment of diseases incident to seamen and passengers in merchant vessels: with directions for preserving their health in sickly climates; intended to afford medical advice to such persons while at sea, where a physician cannot be consulted. Cambridge, MA: Hilliard and Metcalf, 1820. p25.

[27] Barton, WPC. A Treatise Containing a Plan for the Internal Organization and Government of Marine Hospitals in the United States Together with a Scheme for Amending and Systematizing the Medical Department of the Navy. Printed by Author, 1814.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Foltz, Jonathan. “Report on Scorbutus as it appeared on board the United States Squadron, Blockading the Ports in the Gulf of Mexico.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, January 1848.

[30] Roberts, L.J. “Scurvy: A Report of Case.” United States Naval Bulletin, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, January 1927.

[31] Holcomb, Richard C. A Century With Norfolk Naval Hospital, 1830-1930. Portsmouth, Va: Printcraft Publishing Company, 1930. p120.

[32] In a time before permanent Navy hospitals, sick and disabled Sailors and Marines could use Marine Hospital facilities (later Public Health Service). Each month twenty cents would be collected from every officer, seaman, and Marine and placed in a “Marine Hospital Fund” to pay for hospital services.

[33] Langley, Harold. A History of Medicine in the Early Navy. Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1995.

[34] The Naval Asylum was comprised of the Naval Hospital, Navy School, and a retirement home for Sailors and Marines.

[35] This first medical boards were convened four years before this act in Philadelphia and at Gadsby’s Tavern in Alexandria, then still part of the Federal City. The Naval Act formalized the medical boards and made them a requirement for all prospective as well as active duty physicians.

[36] Holcomb, p102.

[37] Green, Hennis and Robert Streeten. (ed).“Sketches of American Physicians: Thomas Harris, M.D.” Provincial Medical Journal and Retrospect of the Medical Sciences. Vol V. London: Henry Renshaw. 1843. p56.

[38] Ibid.

[39] This is may seem stunning if not outright unethical to us today, but such outside employment was permissable in Harris’s day as long as the doctor had permission from his commanding officer and the work did not interfere with his official duties.

[40] Langley, Harold D. “Naval Medicine in Philadelphia, 1815-1840.” Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Vol XVII. December 1995.

[41] Roddis, Louis H. “Thomas Harris, M.D., Naval Surgeon and Founder of the First School of Naval Medicine in the New World.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Vol. V. 1950. p240.

[42] Ibid

[43] Ibid, p242

[44] Sketches, p56

[45] Langley, p142

[46] Roddis, p242

[47] Bache was born 7 February 1801 in Albemarle County, VA, the second child—and first son—of Dr. William Bache and Catherine Sarah Wistar, both of Philadelphia, PA. His father, William, was the son of Sarah and Richard Bache and in turn the grandson of Benjamin Franklin. Catherine was the sister of the eminent Philadelphia anatomist Dr. Caspar Wistar (who himself was the namesake of the Wisteria tree). The Baches’ new son shared the name of William’s deceased older brother, the firebrand journalist and editor of the Democratic-Republican newspaper Aurora, Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-1798). When a yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia the summer of 1798, taking the life of William’s brother, the Baches fled the city. It was at the behest of their friend Thomas Jefferson that they resettled on a farm outside of Charlottesville, VA, fittingly dubbed “Franklin.”

[48] Despite serving as the helm of hospitals, medical officers were not permitted to use the term “Command” or “Commanding Officers” in the 19th century. “Command” was termed saved for officers of the Line Navy only.

[49] Prior to his time as a fleet surgeon, Bache served aboard North Carolina (1824-1827), Falmouth (1828-1830), Pennsylvania (1837-1838), Fairfield (1838-1840) as well as at the Pensacola Navy Yard (1830-1834) and Naval Asylum in Philadelphia, PA. (1844-1847).

[50] Bache also served as a professor of natural history and chemistry professor at Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, during periods of furlough between 1834 and 1838.

[51] Shrady, George (Ed.) “Benjamin Franklin Bache.” The Medical Record. A Weekly Journal of Health and Medicine. New York: William Wood & Company, 1881.

[52] Blochman, Lawrence. Doctor Squibb: The Life and Times of a Rugged Idealist. New York: Simon & Shuster, 1958.

[53] Sobocinski, A.B. “Dr. Bache and the founding of the U.S. Naval Laboratory; or looking back at the Navy’s own ‘Benjamin Franklin.’” Logistically Speaking, 2018.

[54] The History of the Medical Department of the United States Navy in World War II. v.3, The

Statistics of Diseases (NAVMED P-1318). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1950.

[55] Roddis, Louis. “William Whelan—Third Chief of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.” The Military Surgeon, February 1942.

[56] Sobocinski, A.B. The Sacrifice at Fort Fisher, 15 January 1865. Navy Medicine Live, January 2020.

[57] The Flotilla was a division of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron whose mission was to open the navigation of the James River and protect vessels transporting Union supplies and personnel.

[58] Kerr, W. “William Maxwell Wood: The First Surgeon-General of the United States Navy.” Annals of Medical History. Paul B. Hoeber, Inc.: New York, NY. 1924.

[59] Throughout the nineteenth century the lack of provisions can be tied to outbreaks of vitamin deficiencies like scurvy and night blindness in the Navy, impacting operational readiness. And, for better or for worse, shipboard rations could also be linked to shipboard morale.