The Navy Department Library

Battles of Savo Island and the Eastern Solomons

The Battles of

Savo Island

9 August 1942

and the

Eastern Solomons

23-25 August 1942

Naval Historical Center

Department of the Navy

Washington

1994

CONTENTS

Battle of Savo Island

The Battle of the Eastern Solomons

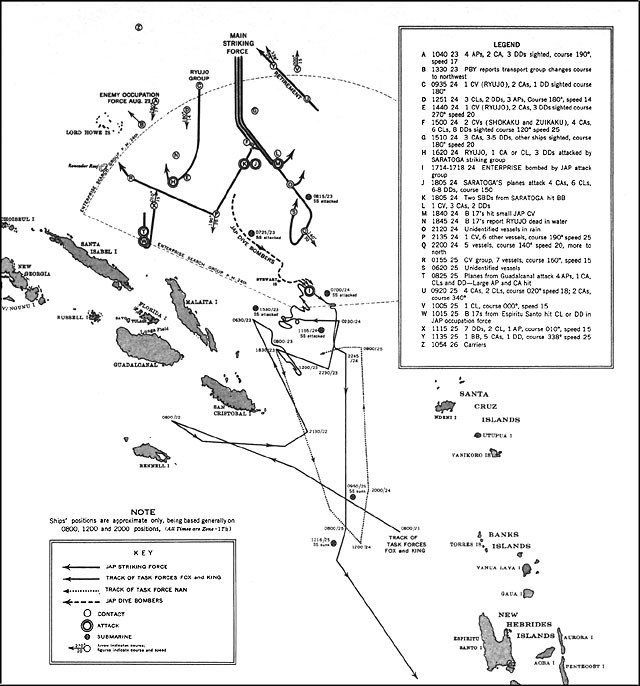

| Introduction | 49 | |

| Disposition of our forces | 50 | |

| Task Force FOX | 51 | |

| Task Force KING | 51 | |

| Events of the 23rd | 52 | |

| Events of the 24th | 53 | |

| Air Search and Patrol | 54 | |

| The Saratoga Attack Group | 56 | |

| Guadalcanal Attacked | 58 | |

| The Second Attack Group | 59 | |

| Air Combat Patrol | 61 | |

| Air Attack on the Enterprise Force | 64 | |

| The Retirement | 69 | |

| Guadalcanal Bombarded | 70 | |

| Events of the 25th | 70 | |

| Summary of events | 71 | |

| Conclusions | 72 | |

| Appendix I: Victories credited to fighter pilots defending the fleet, 24 August. | 77 | |

| Appendix II: Designations of United States naval ships and aircraft. | 78 | |

| Charts and Illustrations | |

|---|---|

| Disposition of Screening Force, Battle of Savo Island [Chart] | x |

| View of Savo Island | xi |

| Removing Canberra personnel | 13 |

| Canberra burning | 14 |

| Chicago with damaged bow | 14 |

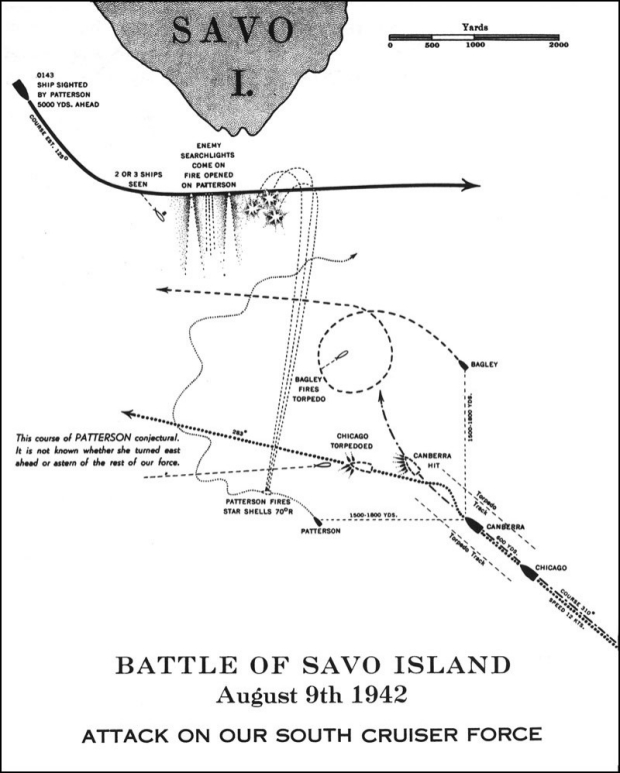

| Attack on South Cruiser Force [Chart] | 15 |

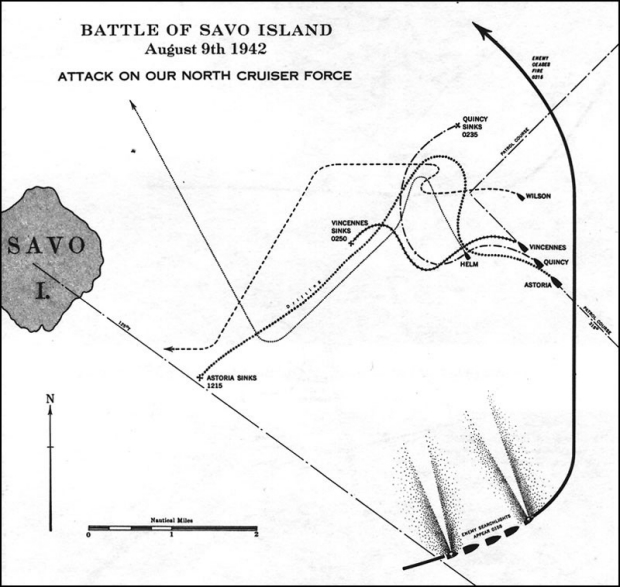

| Attack on North Cruiser Force [Chart] | 16 |

| Chart: | Battle of the Eastern Solomons. | 47 |

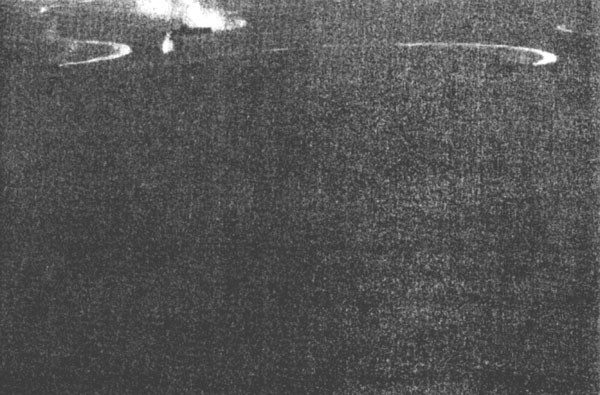

| Illustrations: | Enterprise and screen maneuvering. | 48 |

| Japanese bomber crashes into sea. | 48 | |

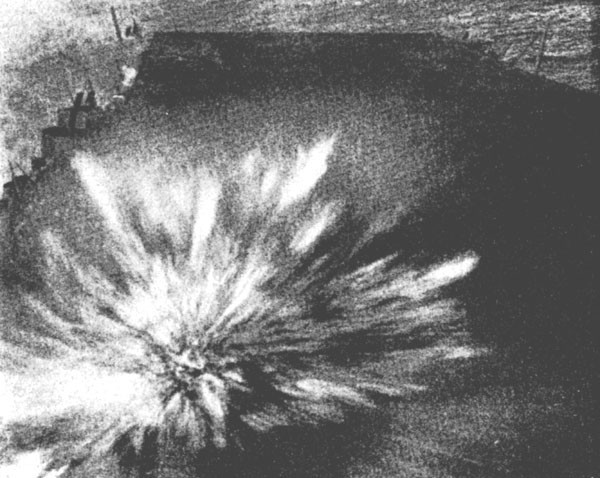

| Enterprise after second bomb hit. | 73 | |

| The battle above the Enterprise. | 74 | |

| Second bomb hit on Enterprise. | 75 | |

| Third bomb hit on Enterprise. | 75 | |

| Fighting fire on Enterprise. | 76 |

The Battle of Savo Island and the Battle of the Eastern Solomons comprise one of a series of twenty-one published and thirteen unpublished Combat Narratives of specific naval campaigns produced by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence during World War II. Selected volumes in this series are being republished by the Naval Historical Center as part of the Navy's commemoration of the 50th anniversary of World War II.

The Combat Narratives were superseded long ago by accounts such as Samuel Eliot Morison's History of the United States Naval Operations in World War II that could be more comprehensive and accurate because of the abundance of American, Allied, and enemy source materials that became available after 1945. But the Combat Narratives continue to be of interest and value since they demonstrate the perceptions of naval operations during the war itself. Because of the contemporary, immediate view offered by these studies, they are well suited for republication in the 1990s as veterans, historians, and the American public turn their attention once again to a war that engulfed much of the world a half century ago.

The Combat Narrative program originated in a directive issued in February 1942 by Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, that instructed the Office of Naval Intelligence to prepare and disseminate these studies. A small team composed of professionally trained writers and historians produced the narratives. The authors based their accounts on research and analysis of the available primary source material, including action reports and war diaries, augmented by interviews with individual participants. Since the narratives were classified Confidential during the war, only a few thousand copies were published at the time, and their distribution was primarily restricted to commissioned officers in the Navy.

The Guadalcanal Campaign was one of the most arduous campaigns of World War II. While it began auspiciously for American forces with little initial opposition from the Japanese, the battle quickly degenerated into a contest of wills that lasted for six months during which the

--iii--

tide of battle ebbed and flowed as both sides injected more and more forces into the struggle. The key to the entire campaign was the control of the sea approaches to Guadalcanal. The first of many Japanese challenges to American sea power was the Battle of Savo Island, one of the worst defeats ever suffered by the U.S. Navy. That engagement provided American naval forces with a bitter lesson in the superiority of Japanese nighttime naval tactics.

The U.S. Navy redeemed itself in another action that is described in this narrative. Two weeks after Savo Island, during the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, American planes sank an enemy light carrier and a damaged seaplane carrier; and the Japanese lost 75 planes. American losses were 25 planes and damage to the carrier Enterprise. The significance of this battle was that it turned back the first major Japanese effort to retake Guadalcanal.

The Office of Naval Intelligence first published this narrative in 1943 without attribution. Administrative records from the period indicate that Ensign Winston B. Lewis wrote the account of the Battle of Savo Island, while Lieutenant (jg) Henry A. Mustin authored the description of the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. Both were Naval Reserve officers. Lewis was a professional historian who taught at Boston's Simmons College prior to the war; after the war, he taught history and political science at Amherst College and later joined the faculty of the U.S. Naval Academy. Before World War II, Mustin was a journalist with the Washington Evening Star. After the war, he returned to that newspaper and later was associated with the Columbia Broadcasting System, Mutual Broadcasting, and the Voice of America.

I wish to acknowledge the invaluable editorial and publication assistance offered in undertaking this project by Mrs. Sandra K. Russell, Managing Editor, Naval Aviation News magazine; Commander Roger Zeimet, USNR, Naval Historical Center Reserve Detachment 206; and Dr. William S. Dudley, Senior Historian, Naval Historical Center. We also are grateful to Rear Admiral Kendell M. Pease, Jr., Chief of Information, and Captain Jack Gallant, USNR, Executive Director, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps WW II 50th Anniversary Commemorative Committee, who generously allocated the funds from the Department of the Navy's World War II commemoration program that made this publication possible.

Dean C. Allard

Director of Naval History

--iv--

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D.C.

1 October, 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U.S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75½ and 76 of Naval Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

/s/

R. E. Schirmann

Rear Admiral, U.S. N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence.

--v--

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

/s/

E. J. King

ADMIRAL, U.S. N.,

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

--vi--

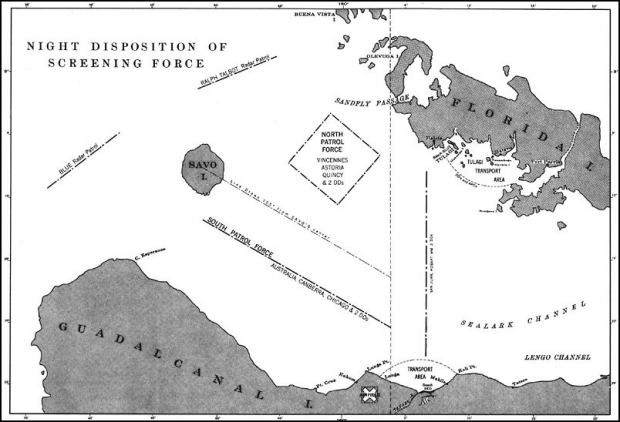

Map showing "Night Disposition of Screening Force" around Savo Island.

View of Savo Island from the East. Cape Esperance at left.

The Battle of Savo Island

9 August 1942

THE MARINES landed in the Solomons in the early morning of 7 August 1942.1 On Guadalcanal the Japanese, apparently believing that only a naval raid was in prospect, retired to the hills, so that our landing was made almost without opposition. On the smaller islands, however, they could not withdraw. On Tulagi and Gavutu they offered the most desperate resistance, and on Tanambogo even succeeded in repulsing our first landing. Consequently on the evening of the 8th the Marines were still engaged in mopping up snipers or in securing their positions on these islands.

This stubborn resistance prevented the completion of our initial operation in one day as planned. Furthermore, the unloading of our transports and cargo vessels was considerably delayed by two air attacks on the 7th and another on the 8th. This protraction of the action had serious consequences, for late in the evening of the 8th our three aircraft carriers, the Wasp, Saratoga, and Enterprise, which had been providing air support from stations south of Guadalcanal, asked permission to retire. Not only was their fuel running low but they had lost 20 of their 99 fighters. Although they had not been sighted by the enemy, it was felt that they ought not to remain within a limited area where the enemy had shown considerable air strength.

In view of the Japanese air raids of the preceding 2 days, the prospective loss of our air protection would leave our ships in a precarious position. The danger was emphasized by information which was received from Melbourne sometime during the afternoon or evening of the 8th.2 This

_____________

1. This is described in the Combat Narrative The Landing in the Solomons, which should be consulted for details of the action and for the organization of our forces.

2. There appear to have been several broadcasts of this warning. An entry in Admiral Turner's diary indicates that he received it at 1800. It was broadcast again from Melbourne at 1821. Admiral Crutchley says that it was received "during the day" and that he discussed it with Admiral Turner. Capt. Greenman of the Astoria remarks that it was received "during the day." Lt. Comdr. Walter B. Davidson in his report for the Astoria's communication department says that an urgent report of the contact in plain language was received from Honolulu during the 1800-2000 watch, and that a coded rebroadcast of the report was being decoded when the battle started. The Quincy's chief radio electrician, W. R. Daniel, remarks that details of the enemy force were received as early as 1600. Capt. Riefkohl of the Vincennes says the report was received "during the afternoon of 8 August" and that there was another report, apparently of the same force, giving their position as of 1200 some 25 miles south of the first reported position. The news of the enemy force was either officially announced or had become general "scuttlebutt" on the Vincennes by evening and caused some men not on watch to sleep beside their guns that night.

--1--

placed three Japanese cruisers, three destroyers and two gunboats or seaplane tenders at latitude 05°49' S., longitude 156°07' E., course 120° T., speed 15 knots at about 1130.3 This position is off the east coast of Bougainville, about 300 miles from Guadalcanal. Shortly before midnight Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, Commander of the Amphibious Force, sent a message to Rear Admiral John S. McCain, Commander Aircraft, South Pacific Force, suggesting that this enemy force might operate torpedo planes from Rekata Bay, Santa Isabel Island, and recommending that strong air detachments strike there on the morning of the 9th.

Because of these developments a conference was held about midnight on board the McCawley, Admiral Turner's flagship. In view of the danger of air attack it was decided to withdraw our ships as early as possible the following morning. Meanwhile the transports continued to unload and land supplies throughout the night both at Guadalcanal and at Tulagi-Gavutu. Supplies were particularly needed in the latter area because it had been necessary to land the Second Marines to reinforce our depleted forces there.

DISPOSITION OF OUR FORCES, NIGHT OF 8 AUGUST

Of the 19 transports in the Task Force, 14 were anchored or underway near Guadalcanal and 5 were in the Tulagi area on the night of 8-9 August. The latter were screened by an arc of vessels composed of the transport destroyers Colhoun, Little, and McKean, reinforced by the destroyers Henley and Ellet. The Monssen had been giving fire support to our troops on Makambo Island that evening, but with the fall of darkness had taken her assigned position screening the San Juan on patrol.

The larger group of transports off Guadalcanal was screened by several ships on the arc of a circle of 6,000 yards radius with the Tenaru River as its center. On this arc were the minesweepers Trever, Hopkins, Zane, Southard and Hovey, and the destroyers Selfridge, Mugford and Dewey.

______________

3. Times in this Narrative are Zone minus 11.

--2--

The transport George F. Elliott, which had been hit during the day's bombing attack, had drifted eastward along the shallow water. As the fire on board could not be controlled, it was decided to sink her. In the evening the Dewey expended three torpedoes without sending her down. She was still burning brightly when the destroyer Hull, having taken off her crew for transfer to the Hunter Liggett, fired four more into her an hour before midnight. Even then she did not sink, but was still afloat and burning when our ships departed on the evening of the 9th.

The disposition of our cruisers and the remaining destroyers was governed by "Special Instructions to the Screening Group," issued by Rear Admiral V. A. C. Crutchley, R. N., commander of the escort groups and second in command of the Amphibious Forces. To protect the disembarkation area from attack from the eastward, the American San Juan and the Australian Hobart, both light cruisers, were assigned to the area east of longitude 160° 04' E., guarding Lengo and Sealark Channels. They were screened by the destroyers Monssen and Buchanan. At 1850 these ships began their patrol at 15 knots on courses 000° and 180° between Guadalcanal and the Tulagi area.

As a precaution against surprise from the northwest, two destroyers were assigned to radar guard and antisubmarine patrol beyond Savo Island. The Ralph Talbot was north of the island, patrolling between positions 08° 59' S., 159° 55' E. and 09° 01' S., 159° 49' E. The Blue was stationed west of the island between positions 09° 05' S., 159° 42' E.4 and 09° 09' S., 159° 37' E., patrolling on courses 051° and 231° at 12 knots.

The area inside Savo Island, between Guadalcanal and Florida, was divided into two patrol districts by a line drawn 125° T. from the center of Savo. It was upon the vessels patrolling these sectors that the Japanese raid was to fall. The area to the north of this line was assigned to the heavy cruisers Vincennes, Astoria, and Quincy, screened by the Helm and Wilson. The last-named replaced the Jarvis, which had been damaged by a torpedo during the day's air attack. This group was patrolling at a speed of 10 knots on a square, the center of which lay approximately midway between Savo and the western end of Florida Island. At midnight it turned onto course 045° T. and was to make a change of 90° to the right approximately every half hour.

The area to the south of the line was covered by the Chicago and H. M. A. S. Canberra, screened by the Patterson and Bagley. H. M. A. S.

_______________

4. The Blue's report gives this as 159° 24' E., but this appears to be a typographical error.

--3--

Australia was the flag and lead ship of this group, but at the time of the action she was absent, having taken Admiral Crutchley to the conference aboard the McCawley. Capt. Howard D. Bode of the Chicago was left in command of the group, although the Canberra ahead of his ship acted as guide. The group was steering various courses in a general northwest-southeast line--the base patrol course was 305°-125° T.--reversing course approximately every hour.

Admiral Crutchley's instructions were that in case of a night attack each cruiser group was to act independently, but was to support the other as required. In addition to the Melbourne warning, a dispatch had been received indicating that enemy submarines were in the area, and night orders placed emphasis on alertness and the necessity for keeping a sharp all-around lookout. The destroyers were to shadow unknown vessels, disseminate information and illuminate targets as needed. It was provided that if they should be ordered to form a striking force, all destroyers of Squadron FOUR except the Blue and Talbot were to concentrate 5 miles northwest of Savo Island. This arrangement was to cause some confusion during the battle.

There was no moon on the night of 8-9 August, and low-hanging clouds, moved by a 4-knot breeze from the northeast, drifted across the sky and added to the darkness. Occasional thundershowers swept the otherwise calm sea. Mist and rain hung heavily about Savo Island and visibility in that direction was particularly bad.

An hour before midnight the Astoria appears to have made a radar contact, but it is not clear whether it was on a ship or a plane.5 Most likely it was the latter, for about the same time the San Juan reported to the Vincennes by TBS6 that she had sighted an aircraft flying eastward from Savo Island, and this word was given the captain. At 2345 the

_______________

5. W. W. Johns, Fire Controlman, First Class, who was on watch in Spot I from 2000 to 2400, says that he turned over the following information to his relief: "A report had been received over the JS circuit that at about 2300 a radar contact on the Astoria SC radar had been made bearing north, distance 34 miles, no other data available." Ens. William F. Cramer, who was on watch in Astoria's radar plot during the same period, says that the radar antenna was operating through a 360° sweep, but that because of the surrounding land there was serious interference on all sides, except for a small arc varying from the west to the northwest, depending on the position of the ship. They were operating on a 30,000-yard scale and "nothing unusual was noticed on the screen."

6. TBS is short wave, voice radio.

--4--

Ralph Talbot on patrol north of Savo sighted an unidentified, cruiser-type plane low over the island. She at once reported on both the TBO7 and TBS: "Warning, warning, plane over Savo headed east." This was repeated for several minutes on both transmitters. Neither the Task Force Commander nor Commander Destroyer Squadron FOUR responded to his code call, and Commander Destroyer Division EIGHT undertook to get the warning through to Admiral Turner.

The Blue to the west of Savo received the Ralph Talbot's warning and a moment later picked up the plane on her radar. Subsequently the plane could be heard as it apparently circled the island and moved off to the south. Some observers believed they saw its running lights. The Vincennes also heard the warning, but Admiral Crutchley did not hear of it until just before the battle started. The Quincy's radar also picked up the plane, and the bridge reported it to Control Forward, but five or ten minutes later sent word to disregard the contact.

Planes continued to fly over at intervals during the next hour and a half. At about 0100 the Quincy (apparently then on a course of 225°) heard a plane pass to starboard going forward. At about the same time the watch in Astoria's sky control reported to the bridge that a plane was overhead, and aircraft engines were heard and reported on the Canberra. Half an hour later the plane was heard, seemingly going in the opposite direction. Shortly after this, a plane crossed the Quincy's port quarter. These contacts were reported to the bridge, but apparently were not passed on to the gunnery control stations, nor was any further warning broadcast to other ships, so far as can be determined.

No more than half an hour elapsed from the time enemy ships appeared without warning around the southern corner of Savo Island till they ceased fire and passed back out to sea. In that short interval they crossed ahead of our southern cruiser group, putting the Canberra completely out of action within a minute or two and damaging the Chicago, then crossed astern of our northern group, battering our cruisers so badly that all three sank--the Vincennes and Quincy within an hour.

The action opened with two almost simultaneous events: contact by our southern cruiser force with the enemy surface force and the dropping of flares by aircraft over XRAY, the transport area off Guadalcanal.

_____________

7. TBO is a portable radio, used also by the Marines.

--5--

At about 0145 several bright flares were dropped from above the clouds over the north coast of Guadalcanal, just southeast of our transport group. They were in a straight line, evenly spaced about a mile apart, and provided a strong and continuous illumination which silhouetted our transports clearly for an enemy coming from the northwest. On the San Juan it was remarked that these flares were exceptionally large, blue-white and intensely brilliant. They burned without flickering and lighted up the entire area. After laying one series the plane returned and repeated the process. Probably the enemy intended to maintain a continuous illumination, for when the first flares were dropped the enemy surface force was just rounding Savo Island, still some 20 minutes away from the beach.

At this time the cruisers of our southern group were on course 310° T., about 4 miles south of Savo Island.8 This was near the northern end of their patrol and they were to reverse their course in a few minutes. The Canberra was leading, with the Chicago about 600 yards astern. The Patterson was about 45° on her port bow, distant 1,500-1,800 yards, while the Bagley was in the same relative position on the starboard bow.

The Australian cruiser was in the second degree of readiness, except that turrets B and Y9 were not manned, although their crews were sleeping near their quarters. One 4-inch gun on each side of the ship was manned. All guns were empty. The Chicago's state of readiness is not reported.

At about 014310 the watch on the Patterson sighted a ship dead ahead. It was about 5,000 yards distant, on a southeasterly course and very close to Savo Island. The destroyer at once notified the Canberra and Chicago by blinker and broadcast by TBS to all ships: "Warning, warning, strange ships entering harbor."11 At the same time she turned left to unmask her guns and torpedo batteries.

______________

8. See chart p. x.

9. Her turrets were lettered from forward aft, A, B, X and Y.

10. There is no precise agreement as to the time of the opening of the action. The Patterson, which was evidently the first to sight the enemy, gives the time as 0146. The Bagley, which must have been a minute later in making contact, gives it as 0144. The Canberra, which was still later, records the time as 0143. The Chicago saw the Canberra swing to starboard at 0145.

11. Comdr. Callahan of the Ralph Talbot reports: "The following was heard at about 0150 on the TBS . . . 'Warning, warning, 3 enemy ships inside Savo Island.' The voice was recognized as that of Comdr. Walker of the Patterson."

--6--

Within a minute and a half of sighting, the enemy changed course to the eastward, following the south shore of Savo Island closely. With the change of course 2 ships could be seen, one of which appeared to be a Mogami-type heavy cruiser, the second a Jintsu-type light cruiser. Some observers on the Patterson's bridge reported seeing 3 cruisers and thought that the second in the column was of the Katori class. When their movement and the Patterson's turn had brought the Japanese cruisers to relative bearing 70° and a distance of 2,000 yards Comdr. Frank R. Walker ordered "Fire torpedoes," but at the same instant the destroyer's guns opened fire, so that the order went unheard and no torpedoes left the tubes. Before this was realized, "something" was reported close on the port bow and the captain ran to the port wing of the bridge to investigate, but was not able to make out anything.

The Patterson's opening salvos were two four-gun star shell spreads, after which No.3 gun continued star shell illumination until it was hit. These were used in preference to the searchlight in order to avoid the possible silhouetting of our own cruisers. Why the Patterson's star shells did not enable our men to see the enemy more clearly than they did is puzzling. As the Patterson's other guns opened with service projectiles, the gunnery officer saw the rear enemy cruiser fire a spread of eight torpedoes. Meanwhile both enemy ships had illuminated our destroyer with their searchlights and had opened heavy fire upon her. One shell hit the No.4 gun shelter and ignited ready service powder. The after part of the ship was for a moment enveloped in flames and No.3 and 4 guns were put out of action, the latter only temporarily. The ship zigzagged at high speed while a torpedo passed about 50 yards on her starboard quarter. She then steadied out on an easterly course, roughly parallel to that of the enemy. Her No.1 and 2 guns maintained a rapid and accurate fire, in which No.4 soon rejoined. The rear enemy cruiser was hit several times, its searchlight extinguished and a fire started amidships.

The Patterson did not cease fire till about 0200, when the Japanese cruisers turned north. Before she lost contact the enemy must have opened fire on our northern cruiser group. All told, the Patterson fired 20 rounds of illuminating and 50 rounds of service ammunition.

It was just before the enemy ships changed from a southeasterly to an easterly course, and therefore about a minute after the Patterson's sighting them, that the Bagley saw unidentified vessels about 3,000 yards

--7--

distant, slightly on her port bow.12 The ships appeared to be on a course of about 135°, moving at high speed, perhaps about 30 knots.

The Bagley, like the Patterson, swung hard left in order to fire torpedoes. In less than a minute the enemy was abeam, about 2,000 yards distant, but before the primers could be inserted in the starboard torpedo battery, the Bagley had turned past safe firing bearing. She therefore continued her turn to the left to bring the port tubes to bear. This required 2 or 3 minutes more, and by this time the range had increased to 3,000-4,000 yards. The enemy formation was becoming very indistinct when four torpedoes were fired. Neither the commanding officer, Lt. Comdr. George A. Sinclair, nor the officer of the deck observed any hit, but the junior officer of the deck saw an explosion in the enemy area about 2 minutes after the firing, and the sound operator, who had followed the torpedoes with the sound gear, reported two intense explosions at the same time. After firing her torpedoes the Bagley continued her circle, went westward, and scanned the passage between Savo and Guadalcanal without sighting anything.

It was evidently very soon after the Bagley sighted the enemy that the port lookout on the Canberra reported a ship dead ahead, but neither the officer of the watch nor the yeoman of the watch could see it.13 At the same time there was an explosion at some distance on the starboard bow. It does not seem likely that this could have been caused by the Bagley's torpedoes, for they were fired at least 3 minutes after sighting the enemy and would have required 2 minutes more to reach their target. About this time the Astoria also heard a heavy, distant, underwater explosion.

Capt. F. E. Getting, R. A. N., and the navigating officer of the Canberra were called promptly, but before they could take any action two torpedoes were seen passing down either side of the Canberra on opposite course. Presumably these were the same which passed near the Chicago a moment later. The general alarm was sounded and the Evershed14

______________

12. The Bagley gives her position at this time as about 1.7 miles from Savo Island, the left tangent of which bore 3I0° T.

13. The Bagley reported that the Canberra turned right only a few seconds after the Bagley sighted the enemy vessels. Furthermore, it would have taken only slightly more than a minute for the enemy ships to have moved from directly ahead of the Patterson to directly ahead of the Canberra, assuming their speed to have been about 25 knots. It is just possible that the ship first seen by the lookout was the Bagley turning left in front of the Canberra.

14. The Evershed is a target bearing designation system. Generally a sight is mounted on either wing of the bridge, from which bearings are transmitted to appropriate stations on the ship.

--8--

was trained on two ships less than a mile distant on the port bow. These appeared to be destroyers or light cruisers. According to the reports of the other ships in the formation, the Canberra was at this time swinging hard right to unmask her guns. Before they could be brought to bear, she was hit by at least 24 five-inch shells, and one or two torpedoes struck her on the starboard side between the boiler rooms. The four-inch gun deck was hit particularly badly. All the guns were put out of action and most of the crews killed. One hit on the barbette jammed turret A in train and another shell exploded between the guns of turret X. The plane and catapult were struck and burst into flames. A serious fire was started by hits in the torpedo spaces, and other fires broke out at various points. As a result of the torpedo explosion, light failed all over the ship. The engine rooms filled with smoke and had to be abandoned.

The Canberra may have been able to fire a few shots in return, for the Bagley reported that as the cruiser turned right she opened fire with her main battery, and that it was the second or third enemy salvo which landed. The Chicago too reported that the Canberra (then on her starboard bow) opened fire.15 According to the Canberra's own report, the port 4-inch guns may have fired one or two salvos before being put out of action, and one gun of turret X may have fired one salvo. Possibly two of the port torpedoes were fired.

Within a minute or two the ship stopped and lay helpless. She was listing about 10° to starboard and was lighted by several intense fires. Upon receipt of word that the captain was down,16 the executive officer, Comdr. J. A. Walsh, R. A. N., took command.

Apparently the Chicago did not sight the Japanese ships until the Canberra swung to starboard, but 3 minutes earlier she had seen two orange colored flashes near the surface of the water close to Savo Island. Capt. Bode was apparently on deck, as the Chicago's report does not mention his being called. The flashes were followed very shortly by the appearance of the first flare over the transport area, and the Canberra was seen to turn about 2 minutes later. As she turned, two dark objects could be seen between the Canberra and Patterson and another to the

______________

15. The sequence of events according to the Chicago was as follows: 0142 orange flashes seen; 0143 first of 5 aircraft flares seen, bearing 160° to 170° R.; 0145 Canberra turns; 0146 dark objects and torpedo wakes sighted; 0147 Chicago hit by torpedo, flashes of gunfire seen on both port and starboard bows, Canberra opens fire, Chicago fires star shells.

16. Capt. Getting was seriously wounded and died a day later.

--9--

right of the Canberra. It seems probable that it was this last which fired the torpedoes into the cruiser's starboard side. It will be remembered that 2 or 3 minutes before this, the Patterson had seen "something" on her port bow as she turned left and that not long afterward a torpedo passed on her starboard quarter.

Whatever the objects were, the Chicago's 5-inch director was trained on the one to the right, beyond the Canberra. She was preparing to fire a star-shell spread when the starboard bridge lookout reported a torpedo wake to starboard and she started to turn with right full rudder. The ship had turned only a little to starboard when the main battery control officer sighted two torpedo wakes bearing 345° R., crossing from port to starboard. Since the first torpedo to starboard had not been seen on the bridge and that to port had been, the ship was given left full rudder. It was intended to steady out when the ship's course paralleled the wakes, but at that point something that was thought to be a destroyer in a position to fire torpedoes was seen farther to port, and the order was given to swing farther to the left.

Before the helmsman could comply, the talker in main battery control forward saw the wake of a torpedo headed for the port bow on bearing 345° R., and at almost the same moment it struck the bow well forward. "The forward part of the ship to amidships was deluged with a column of water which was well above the level of the foretop." The bow below the water line was largely blown off, but this did not seriously alter the trim of the ship or impair operation at the moment. The Chicago's track chart shows that she was on course 283° T. when she was hit. Since the torpedo was seen approaching on 345° R., it must have come from 268° T.; i. e., it came not from the direction of the enemy cruiser line, but from the west. Perhaps it was fired by the destroyer, or whatever it was, seen to port shortly before the Chicago was hit.

At the same time that the Chicago was torpedoed, flashes of gunfire were observed close aboard, bearing 320° R. Since the Patterson had opened fire by this time and must have been somewhere on the Chicago's port bow, she may have been responsible for the flashes seen.

It appears that the Chicago had not yet sized up the situation. Her port battery fired two four-gun salvos of star shells toward the flashes bearing 320° R., while the starboard battery fired the same number at 45° R., set for 5,000 yards, to illuminate what appeared to be a cruiser beyond the Canberra. This cruiser was firing on the Australian ship,

--10--

which lay about 1,200 yards distant, bearing 45° R. from the Chicago. To the left of the Canberra, 2,500 to 4,000 yards distant, were two destroyers which were thought to be enemy. Probably they formed the guard astern of the enemy cruisers. Not one of the 16 star shells fired by the Chicago at this critical moment functioned, so that positive identification could not be made.

At this time a shell hit the starboard leg of the Chicago's foremast, detonated over the forward funnel, and showered shrapnel over the ship. Shortly afterwards a ship ahead, which was thought to be the Patterson, illuminated with her searchlight two ships which appeared to be destroyers on the port bow. The Chicago's port battery opened up on the left hand destroyer with a range of 7,200 yards. The target was hit twice, apparently not by our cruiser but by the destroyer thought to be the Patterson. A minute later the latter ship turned off her searchlight and crossed the line of fire of the Chicago's port battery on a course opposite to that of the Chicago.

There is some possibility that the Chicago's identification of these ships was mistaken. In the Patterson's report it is specifically stated that she did not use her searchlight for fear of silhouetting our cruisers, but used star shells instead.

Meanwhile the poor visibility had prevented the main battery director from picking up the cruiser on the starboard bow, and the starboard 5-inch battery had expended all ready service star shells without the main battery's being able to get a "set up" on the target. This was due largely to the fact that out of a total of 44 star shells fired by the Chicago during the action, only 6 functioned.

At about this time the port 5-inch battery also lost its target, the destroyer 7,200 yards on the port bow, but just before firing ceased the burst of a hit was seen. In an effort to relocate this target, the shutters on No.2 and 4 searchlights were opened as the ship was swinging to port, but they swept only empty sea. In the meantime the gun engagement to starboard (probably involving the main enemy cruiser force) had moved on to the northward. Director II was on a ship bearing 120° R., but soon reported it as a friendly destroyer, while another ship bearing 270° was also identified as friendly. Probably the former was the Patterson and the latter the Bagley.

In fact the enemy had completely left our southern group and was now engaging the Vincennes group. With no target in sight there was

--11--

time to take stock of the situation aboard the Chicago. Damage control reported some forward compartments flooded, but shoring of bulkheads was already underway and it was thought the ship could do 25 knots. A message was decoded ordering withdrawal toward Lengo Channel, and the Chicago slowed down to 12 knots. Five or six minutes later, before she had turned back, a gun action was seen to the westward of Savo Island. The Chicago moved toward it at full speed, and a few minutes later fired a star shell spread bearing 100° R. set for 11,000 yards. The ships were out of range, however, and the Chicago ceased fire. A fire was visible in the distance but it was not certain whether it was on one of the ships or on the far side of Savo Island. A range of 18,000 yards was obtained on it, but the firing had ceased, no ships were visible, and the Chicago again slowed to 12 knots.

It is impossible to say what this engagement seen from the Chicago was. The time was about 0205, whereas the only known engagement beyond Savo was that of the Ralph Talbot about 0220.

Of the ships in our southern group, the Canberra had been put out of action before she could fire more than a few rounds. The Chicago had gone off to the west while the enemy passed to the eastward, and had been able to take no effective action. The Bagley, after firing her torpedoes, had started on a futile search of the channel to the west. Only the Patterson had correctly estimated the situation and had followed the main enemy force to the east.

The entire engagement with our southern group seems to have lasted no more than 10 minutes. Since the enemy cruisers passed to the eastward, they must have opened fire on our northern force immediately after breaking off action with the southern.

Our northern cruiser group was patrolling its square at a speed of 10 knots. The Helm was 1,500 yards on the port bow and the Wilson 2,000 yards on the starboard bow of the Vincennes. The Quincy and Astoria followed rather closely in order to enjoy the maximum antisubmarine protection from the destroyers. All three cruisers were in Condition of Readiness II. On the Vincennes all guns of the main battery had remained loaded since the noon air attack, and two guns in each turret were manned. Broadside antiaircraft and heavy machine gun batteries

--12--

Destroyers removing personnel from the Canberra.

--13--

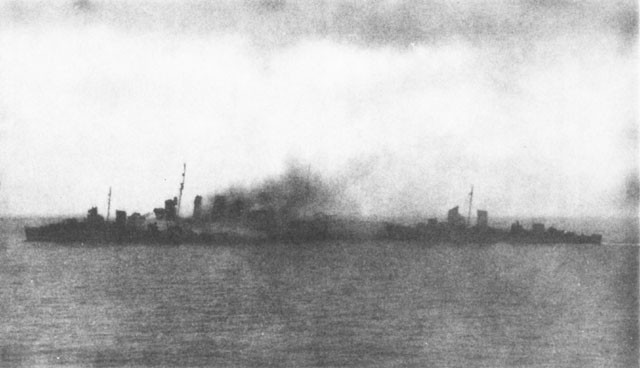

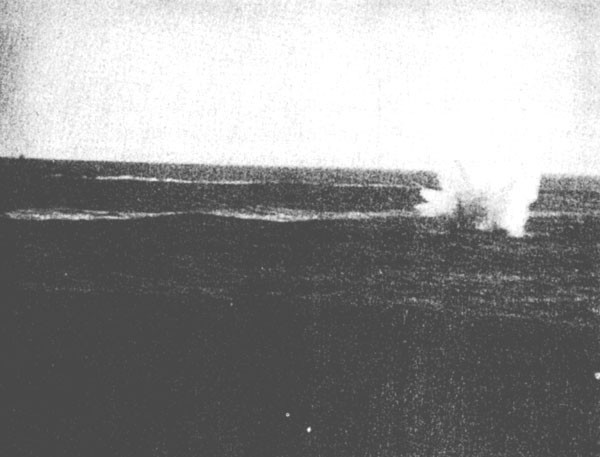

Canberra with destroyer alongside, Savo Island in background.

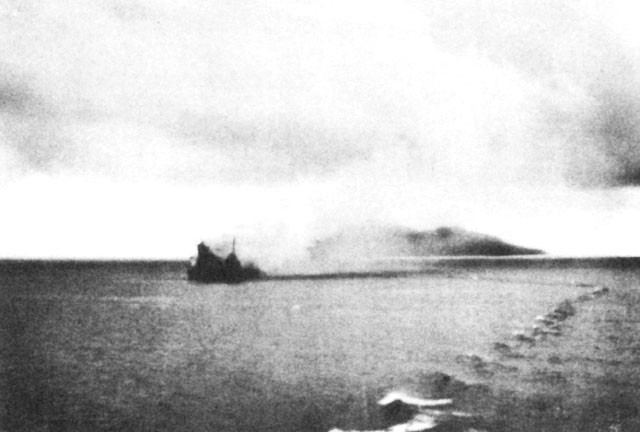

Chicago, showing damaged bow.

--14--

Attack on South Cruiser Force

--15--

Attack on North Cruiser Force

--16--

were fully manned, as were plot and most control stations. Steam was available for 30 knots. The Quincy was in Material Condition of Readiness YOKE, with Ammunition Condition of Readiness I in main and antiaircraft batteries. On the Astoria all guns of the main battery were loaded and two guns in each turret were manned. The antiaircraft battery was completely manned. The ship was in Material Condition ZED, with a few exceptions necessary because of the heat, which had caused several cases of prostration during the day.

At about 0120 the group turned onto course 315°.17 Since course was altered approximately every half hour, another change was due at 0150. But at about 0145 the Vincennes ordered by TBS that the course be held until 0200. The Quincy and Wilson had some difficulty in getting these orders and they were repeated several times. Thus the orders and their acknowledgment occupied the TBS for several minutes--at a most critical time, as it turned out.

Probably the first incident in the rapid succession of events which was to follow came about 0145, when a lookout on the Vincennes' main deck aft saw a submarine surface and then submerge about 600 yards distant on the port quarter.18 This was reported to the pilot house, but it is not certain that the report was acknowledged. About the same time one of the sky lookouts called the attention of Lt. Comdr. Robert R. Craighill, assistant gunnery officer, to "a shape he thought he saw about broad on the port bow." Lt. Comdr. Craighill searched the area with binoculars, but there was a rain squall in the vicinity of Savo and he could make out nothing.

Perhaps about 2 minutes later--about 0147 as nearly as may be deter-

______________

17. It is not entirely clear whether this was 0120 or later, as accounts were contradictory. Capt. Riefkohl, in command of the group, said, "at 0120 change of course to 315° was ordered and at 0200 to course 045°." Lt. Comdr. Heneberger, senior surviving officer of the Quincy: "At 0050 orders were received that change of course would be made at 10 minutes before and 20 minutes after the hour . . . At 0120 the formation changed course to 315° (T.) . . . At 0145 a fix was obtained . . . Orders were received for the formation to remain on course 315° (T.) until the end of the hour." But Lt. Comdr. Topper, who was supervisory officer of the deck on the Astoria stated, "At about 0120, while on course 225° T., word was broadcast over TBS from the Vincennes, the senior ship of our group, that the formation would continue on its present course until 0140, at which time we would change course to right by column movement the same amount that we would normally have changed at 0130. The Quincy and destroyer 408 (Wilson) experienced some trouble in getting this information over the TBS, and it was repeated several times. At 0140 the Vincennes changed course to right to 315° T., the Astoria changing course by column movement at about 0144." Lt. (jg) Noel A. Burkey, jr., who was officer of the deck on the Astoria, wrote, "At 0140 the formation started making a change of course to 315° T., the Astoria making her turn about 0145. About 5 minutes later the lookouts, main battery control and bridge personnel reported white flares on our port quarter."

18. For chronology of the northern cruiser action see table pp.32-33.

--17--

mined19 - the Patterson's message came over the TBS: "Warning, warning, strange ships entering the harbor." The report was received on the Vincennes, but it did not reach the captain asleep in his emergency cabin adjoining the pilot house, and it is not certain that it was heard by the executive officer on the bridge. The warning was also heard on the Quincy and general quarters was sounded, but the report was not passed on to the gunnery control stations. The Astoria was using her TBS to acknowledge orders regarding the change of course and did not receive the report. The Wilson heard the broadcast, but apparently the Helm did not.

By this time flares or star shells were seen. Actually the first of these seem to have appeared a minute or two before the TBS warning. There were two groups visible from the Vincennes. The first were almost astern. Very shortly afterward, flares or star shells and then gunfire were seen to port, in the direction of our southern force. Those astern were well below the overcast, white and evenly spaced across the sky from about 200° to 180° R. Those to the right appeared first, the others following in quick succession. They were apparently laid about normal to the course of our ships, although to one or two observers they seemed rather to parallel it. The estimates of their distance run from 3,000 to 10,000 yards.

It was not at once clear whether they were star shells or flares. Lt. Comdr. Truesdell, gunnery officer of the Astoria, believed they were flares: "Their interval of appearing was so short that it indicated that they could not have been fired by a single pair of guns. Also, if fired simultaneously from one battery they should appear almost simultaneously."

It seems probable that these were the flares dropped near the transport area, which otherwise were not seen from our cruisers. The direction is about right, as is the time. If this is true, the estimates were in error and they were at a considerably greater distance than they seemed. If, on the other hand, they were really only 3,000 to 4,000 yards astern, they must have been near the southern corner of the patrol square and designed to illuminate our cruiser group.

______________

19. The Ellet at Tulagi recorded its receipt at 0146. Naturally it is impossible for the officers on our ships which were engaged to recall at precisely what time events took place. The following is based upon the sequence of events as reconstructed by our officers, with an attempt to relate and synchronize accounts.

--18--

At any rate, the flares did give the Vincennes group a very brief warning, and it was by their light that the enemy cruisers were first identified from the Astoria so that fire could be opened promptly.

One or the other of the two groups of flares was seen from all of our cruisers. On the Astoria, R. A. Radke, Quartermaster Second Class, sighted the flares astern and then saw a ship at a considerable distance on the port bow open fire--evidently the Japanese firing on our southern force. He thereupon promptly rang the general alarm on his own initiative. Just as he pulled the switch, he received the order from the bridge to stand by the general alarm." At the Quincy's control forward it was at first thought that the flares astern were star shells fired by our destroyers near Tulagi to locate the enemy plane which had been heard shortly before. But very soon afterwards the TBS warning was received; Capt. Samuel N. Moore was called, general quarters was sounded, all boilers were lighted off and Condition ZED was set throughout the ship. This was, however, probably about 2 minutes later than on the other ships.

Lt. Comdr. Craighill of the Vincennes sighted the star shells astern, but it was the flares over the Canberra and Chicago that were seen from the bridge. Comdr. William E. A. Mullan, executive officer, at once ordered general quarters sounded. He described the scene: "Almost at once there was a great display of light, and silhouettes of a group of ships southeast of Savo Island could distinctly be seen and recognized as the southern group of Allied ships. They were, I believe, on approximately the same course as the Vincennes, which was northwest."

Capt. Frederick L. Riefkohl of the Vincennes, commanding our northern cruiser group, had been called promptly. As he stepped from his emergency cabin, to which he had retired less than 2 hours earlier, he could see three or four star shells at a distance on the port beam, and a ship firing star shells toward the southeast. Another ship to the left was firing toward the first. "I estimated," he reports, "that Australia group had made contact with a destroyer. I received no report of the contact or orders to concentrate. I thought this contact probably a destroyer and a ruse to draw off my group while the main attack force passed through my sector to attack the transports. If enemy heavy ships had been sighted I expected Australia group would illuminate and engage them, and the situation would soon be clarified. I considered turning right to course 045° T., but felt I might be called on to support Australia group. I signalled speed 15 knots and decided to hold my course

--19--

temporarily. Fired no star shell as I did not wish to disclose myself to an enemy approaching my sector from seaward."

The brief warning given the Vincennes group was inadequate. In spite of the fact that a large proportion of the men were either on watch or sleeping near their posts, it is doubtful if battle stations were completely manned on any of our cruisers by the time searchlights were turned on them and a rain of shells followed. Lt. Comdr. Chester E. Carroll of the Helm describes the opening of the action: "The Vincennes group continued on course. A few minutes later our force was under fire, the Quincy apparently being hit immediately, with large fires amidships. One cruiser immediately opened fire, followed by the other two. The point of aim of the cruisers was not clear, as some fire was to port and some to starboard." Lt. Comdr. Walter H. Price of the Wilson remarks, "Our cruisers appeared to be enveloped in a plunging fire as soon as they were illuminated."

Capt. Riefkohl's order for an increase in speed had just gone out on the TBS when a searchlight appeared about 7,000 yards on the port quarter (250° R.). This light, which seemed to be directed at the Astoria, was followed at once by a second to the right, which picked out the Quincy, and third light still further to the right, which was turned on the Vincennes.20 Lt. Comdr. Truesdell suggests that the enemy used destroyers ahead and astern to illuminate and to draw our fire, for the cruiser upon which the Astoria opened fire a moment later was to the right of a searchlight and did not have a searchlight on.

Enemy fire followed the searchlights, and a salvo seems to have landed near each of our cruisers as soon as it was illuminated. Lt. Comdr. Truesdell speculates that the enemy may have concentrated upon each of our cruisers in turn, two ships initially firing upon the leader of our column and the third ship firing upon our second cruiser. A comparison of the reports, however, indicates that our ships were taken under fire almost simultaneously, the Astoria at the rear perhaps slightly before the Vincennes in the van. It seems that for the first few minutes at least, only one cruiser was firing on each of ours.

The Astoria was the first of our cruisers to return the enemy's fire. This was due to the alertness and initiative of the gunnery officer. At

_____________

20. This account is based on the reports of Capt. Riefkohl and Lt Comdr. R. L. Adams, gunnery officer of the Vincennes. Capt. Riefkohl says the first searchlight bore 205° T. On the Astoria it was thought that the first light was directed at the Vincennes.

--20--

the first appearance of the flares, Lt. Comdr. Truesdell had ordered the main battery trained out on the port quarter. At the same time he requested the bridge to sound general quarters. Very shortly afterwards he and the ship's spotter, Lt. (jg) Carl A. Sander, saw on the port quarter the silhouette of a Japanese cruiser which Lt. Sander identified as of the Nachi class. Then the first searchlight came on. Almost simultaneously, a salvo landed 500 yards short and 200 yards ahead of the Astoria. Lt. Comdr. Truesdell asked permission to fire. A second enemy salvo landed 500 yards short, 100 yards ahead. The next would probably be on in deflection. Receiving no answer from the Bridge, Lt. Comdr. Truesdell himself gave the order to fire, and the main battery sent off a salvo toward the port quarter. All 3 turrets fired, but it is not certain whether 6 or 9 guns participated. The range was 5,500 yards, bearing 240° R. (about 195° T.). The general alarm was still ringing and Capt. William G. Greenman, who had just been called, was astonished to hear the main battery fire as he awoke. He was just entering the pilot house when the battery fired again. Capt. Greenman's first impression on seeing the flares and searchlights inside the bay was that our ships had sighted a submarine on the surface and that we were firing into our own ships. Lt. Comdr. Topper, who was on the bridge, reports him as asking, "Who sounded the general alarm? Who gave the order to commence firing? Topper, I think we are firing on our own ships. Let's not get excited and act too hasty. Cease firing."

Upon this order, firing ceased. Someone on the port wing of the bridge reported searchlights illuminating our ships, while word came from main battery control that the ships had been identified as Japanese cruisers. By this time, too, the Vincennes' order to increase speed to 15 knots had been reported to the captain. Then the JA talker reported, "Mr. Truesdell said for God's sake give the word to commence firing." The captain then ordered, "Sound general quarters,"--it was in fact sounded this second time,--and almost immediately, "Commence firing," with the remark, "Whether our ships or not we will have to stop them."

"I believe this remark," explains Lt. Comdr. Topper, "was caused by the splashes that had just landed ahead and to port of the Astoria." This was probably the enemy's third salvo, which was still about 500 yards short.

Our other two cruisers opened fire not long after the Astoria. On the

--21--

Vincennes the general alarm must have been sounded very nearly as promptly. The 8-inch guns were already loaded, but control had not yet received word that the battery was manned when the first enemy searchlight appeared.21 Lt. Comdr. Robert L. Adams, the gunnery officer, immediately ordered the main battery trained out to the left to pick up the target, but before the guns could be brought to bear the second and third enemy searchlights came on and an enemy salvo landed 75 to 100 yards short. The Vincennes replied with an 8-inch salvo, using a radar range of 8,250 yards. (This was somewhat greater than the range obtained by our other cruisers.) Simultaneously the 5-inch battery fired a broadside of star shells for illumination. Before the Vincennes could fire again an enemy salvo landed on the well deck and hangar, where intense fires broke out. The bridge, too, was hit, and the communications officer and two men m the pilot house were killed.22 After this salvo electric power for the guns failed, but within a minute it was restored and the 8-inch battery resumed fire. By this time the ship was being hit heavily, and word came from aft that Battle II had been hit. Sky Forward and Sky Aft were hit about the same time. Only one badly wounded man survived the hit on the latter station.

Of our three cruisers the Quincy was hit most severely. Since it was at first thought that the star shells astern had been fired by our own destroyers, general quarters was not sounded until about 2 minutes later, when the TBS warning came through. Just before the enemy searchlights came on, the silhouettes of three cruisers rounding the southern end of Savo could be discerned from the bridge. These had three turrets forward, the middle being the highest. Apparently none of this information was passed on to the control stations, so that "the first intimation the gunnery control stations had that enemy ships were in the vicinity was when they turned searchlights on the formation, immediately followed by a salvo falling just short of the U.S. S. Vincennes."23

When the enemy searchlights came on, the Bridge ordered, "Fire on the searchlights." But the batteries were not yet completely manned and plot had not yet reported ready to Control Forward when the ship was hit

______________

21. According to one report this was about 1 minute after general quarters was sounded, according to another, 5 minutes.

22. According to the report of Lt. Comdr. Adams, the Vincennes was hit immediately after firing her first salvo, but Capt. Riefkohl's and Lt. Comdr. Craighill's reports indicate that she was hit on the bridge just before the turrets fired. At any rate, the two events were very close together.

23. Report of LL Comdr. Harry B. Heneberger, senior surviving officer.

--22--

on the 1.1-inch gun mounts on the main deck aft. Very shortly afterwards the Quincy was able to reply with a full nine-gun salvo. A range of 6,000 yards was used, although just before the guns were fired a radar range of 5,800 yards was obtained. Target angle was estimated to be 60° and speed 15 knots. (Our other cruisers assumed a target angle of 315° and speed of at least 25 knots, which was probably more accurate.) Meanwhile the ship received many hits. A plane in the port catapult caught fire, which illuminated the ship as similar casualties illuminated our other cruisers. From our other ships the Quincy soon appeared a mass of flames.

Thus in the first 2 or 3 minutes of action our cruisers had been hit repeatedly and set ablaze before they could fire more than one or two salvos each. While it is clear that the main enemy force was on their port quarter, crossing astern of our formation, it is just possible that other enemy ships were to starboard. Lt. Comdr. Ellis K. Wakefield, who was in sky forward on the Astoria, says that when our ships opened fire on the searchlights on their port quarter one of his talkers observed shooting in our direction from ships on the starboard quarter. Lt. Comdr. Wakefield thereupon "ordered sky forward to commence firing at flashes of light, apparently from gunfire, bearing about 150° R.," but he received no acknowledgment of this order. Comdr. Mullan of the Vincennes, remarks, "At this time [the time of the first enemy hits] there was a great deal of illumination on the starboard hand, but I do not know from what source."

When our cruisers opened fire, the Helm on the port bow of the Vincennes opened fire also. However, no target was visible and the situation was not clear, so that "cease fire" had to be ordered at once. Although it appeared that our cruisers were being illuminated from the southeast, smoke from the fires already blazing on them so obscured the picture that there could be no certainty.

Soon orders were received on TBS from the Vincennes for the screening destroyers to attack. Since it could not yet be ascertained in which direction the attack should be made, the Helm remained in formation for several minutes before heading south. At about 0200, after she had been moving south for a few minutes, a ship could be seen about 8,000 yards on the port bow, partially illuminated by a searchlight. It was close to the southern shore of Savo Island, apparently headed seaward. The Helm changed course to the southwest and closed at full speed,

--23--

preparing to make an attack. As she approached, however, the ship was again illuminated and could be identified as one of our own destroyers. Probably it was the Patterson, which had trailed the enemy eastward and had lost contact about this time.

The Wilson, on the starboard bow of the Vincennes, had the advantage of having received the TBS warning and also enjoyed a clearer view of the situation. When the enemy searchlights came on, she immediately opened fire on the right hand light with all four 5-inch guns, using a range of 12,000 yards. After two salvos she had to turn to the left to keep guns No. 1 and 2 bearing. Evidently she did not receive the order to attack, for Lt. Comdr. Price remarks that the order to increase speed to 15 knots was the last he received from the Vincennes. After a few moments of action all three of our cruisers were seen to be on fire. As the Wilson continued firing rapidly, it is possible that it was her gun flashes that Lt. Comdr. Wakefield saw to starboard of the Astoria, although she should have been on the starboard bow, rather than the quarter.

Meanwhile the bearing of the enemy force on the port quarter was drawing rapidly astern. After the first salvo or two the forward directors and turrets of our ships could no longer bear, and gunnery officers began to request that their ships come left.

When the first enemy salvos landed, Capt. Riefkohl on the Vincennes ordered speed increased to 20 knots and started a turn to the left "with a view of closing the enemy and continuing around on a reverse course if he stood in toward the transport area." He intended to make the turn by simultaneous ship movements, but all communications had failed after the bridge had been hit, and he could send no signal. The Quincy24 seems to have followed the lead of the Vincennes, while Capt. Greenman of the Astoria, seeing that the ships ahead were 10° to 15° to the left of the base course, ordered left rudder and full speed ahead. The Astoria's speed, however, increased only slightly.

During this turn to the left our ships were taking a terrific pounding, but they continued to fire. With the Vincennes' second salvo--she fired only two to port from the main battery--there was an explosion on the target and the enemy searchlight went out. The assistant gunnery officer, Lt. Comdr. Craighill, saw the target make a radical turn to the left as if

_____________

24. The Quincy's report gives the impression that she started turning to starboard at the opening of the action, but it is clear from the other reports that she first followed the Vincennes to the left. It was actually a little later that she turned to starboard.

--24--

it had gone out of control, after which it was lost from sight. Inasmuch as the Vincennes 5-inch battery, the Wilson, and perhaps the Quincy may have been firing on the same target, it cannot be determined who made the hit.

The Quincy was badly on fire and had received a hit in her No.1 fireroom. Sometime very early in the engagement the bridge was hit and many of the personnel there were killed. She was firing, but the enemy was drawing astern so rapidly that after one or two salvos from the main battery, director I and the two forward turrets could no longer bear. Control was shifted to director II with orders to fire turret III. This turret, however, had just been hit and was jammed in train, so that for a few minutes not one gun of the main battery could be used.

On board the Astoria the interval between the order to cease fire and commence fire had been only a minute or two. After the first two salvos, turret II had reached the limit of its train (218° R.), but the order to turn left was given at about the same time as the order to recommence fire, so that the turret could soon bear again. Before the Astoria could resume fire, the enemy fourth salvo arrived. It was about 200 yards short, but seems to have been good for one hit on the Astoria's bow. The fifth Japanese salvo was on the target, making four or more hits amidships. Fires were started in the hangar and at other points. Power for turret III was temporarily interrupted, so that the Astoria's answering salvo (her third) was fired by only the six guns of turrets I and II. The enemy at this time was about 6,200 yards distant, bearing 235° R.

Having once found the Astoria's range, the enemy kept it. Immediately after firing the third salvo, turret I received a direct hit. Flames sprang up, then quickly died down as the turret burned out. At the same time a hit on the barbette of turret II put the shell hoist for the right-hand gun out of commission, so that the fourth salvo was fired by only 2 guns. The range was now 6,000 yards, bearing 225° R.

The 5-inch battery seems to have opened fire about the same time as the main battery, and the 1.1-inch at the time of the captain's order to resume fire. However, either the guns or their ready service boxes were hit before many of them could fire more than 6 or 7 rounds, while the director in sky forward was hit, forcing the 1.1-inch guns onto local control.

During this time our ships were turning left, but, as Lt. Comdr. Truesdell remarked, "all ships turned too slowly, and the increase of speed

--25--

was too slow to clear the next astern." As a result the Astoria found herself coming up into the Quincy's line of fire and had to turn sharply to the right across her stern to clear her. This shift to the right brought the enemy bearing astern more rapidly, so that after one or two more salvos neither director I nor turret II could bear. Control was shifted to director II, which fired another three-gun salvo from turret III, bearing 170° R., range 5,000 yards. Meanwhile turret II had trained around to starboard, and director I was soon able to fire two more salvos with both turrets. That was all, for shortly both the main battery control and director I ceased to function and turret III lost power. Only turret I was able to fire a little longer on local control.

In these few minutes the ship had been raked heavily from both quarters as the enemy crossed astern. The boat deck had been hit and was flaming after the 5-inch guns had fired about eight salvos. Power for these was lost, and what remained went onto local control until the progress of the fire soon put an end to their activity. Sky Aft reported that they were getting burned and were forced to break off communication. The bridge was hit and the helmsman fell. Another man took his place. The engine rooms were being abandoned, their crews driven out by smoke and flames drawn down their ventilators and intakes. After this the ship began to lose speed.

It could not have been long after the Astoria swung right across the Quincy's stern that the Vincennes at the head of our group turned to starboard. Her forward turrets had again reached their limit of train to the left, and the ship was being hit severely. The previous turn to the left had brought the ship's head around to about 275° T. when Capt. Riefkohl, in an attempt to throw off the enemy's fire and to enable the forward guns to bear, turned hard right and signalled flank speed. The engine room answered the signal, but only about 19.5 knots was reached.

While the ship was turning right two or three torpedoes crashed into the port side under the sick bay and near No.4 fireroom. The ship "shook and shuddered" under the impact of the explosion, which seems to have been remarkably heavy. Since no flash from torpedo tubes had been seen, Capt. Riefkohl thought that the torpedoes might have been fired by a submarine. At about the same time a hit on the main battery control station aft killed most of the men there, while other hits fell on the rangefinder hoods of the forward turrets and fragments penetrated the officers' booth of turret II, seriously wounding personnel there.

--26--

After the torpedoing, power was lost for the main battery. Diesel auxiliaries were cut in for turrets I and III, but there was none available for turret II. During this turn to the right only turret III continued firing.

Until the Vincennes turned right, two destroyers which were thought to be the Helm and the Wilson were ahead on the starboard hand. Our cruisers' turn to the left would probably have brought them into this relative position. "One destroyer was then observed crossing our bow from port to starboard, while the other was crossing from starboard to port. The one crossing from port to starboard may have been an enemy, but as the two vessels barely missed colliding and did not fire on one another, it is believed that they were both friendly. One DD, on our starboard hand, probably Wilson, was observed firing star shell and what appeared as heavy antiaircraft machine-gun fire."25

The Wilson's account of the episode explains that when the Vincennes turned right, she, too, turned right, unmasking her starboard battery. She had continued on this course for several minutes when "the gun flashes disclosed a Monssen-type destroyer close aboard the starboard bow on a collision course. In order to avoid collision, speed was increased to 30 knots and the ship swung hard left. Continued this left turn until clear of the destroyer and the battery was unmasked to port. Reopened fire as soon as possible." By this time the Wilson had lost sight of all our cruisers except the Astoria, which was under heavy fire. She continued fire on the searchlight till it went out. Then she shifted her aim to a light to the left, which was still illuminating the Astoria, and fired till it went out. By that time no more targets were visible, and the location of our own forces was unknown, so the Wilson headed toward Savo Island.

The Helm does not mention the near collision, and, if the times given in her report are correct, she was in fact making her excursion to the south at that moment. This makes it appear quite possible that the second destroyer was Japanese. If it was really the Helm, the incident must have occurred just before she went south, for when she returned and "passed through the cruisers between the Vincennes and Quincy, the latter appeared to be stopped and to have suffered heavy damage." The Vincennes was by that time firing in an easterly direction and it could be seen that our cruisers were illuminated by a searchlight to the

______________

25. Capt. Riefkohl's report.

--27--

east. The Helm remained near the Vincennes for some time, and orders were given to fire on the searchlight, but almost immediately it went out. The Quincy had indeed suffered heavy damage. She had started swinging to starboard about the same time as the Vincennes. As soon as they could bear on the starboard quarter, turrets I and II reopened fire (turret III had been hit and jammed in train), while the starboard antiaircraft battery started firing star shells. It got off only three salvos, however, before being put out of action. After two salvos turret II exploded and burned out, and turret I was put out of action by a hit in the shell deck and a fire in upper powder. By this time the entire 5-inch battery had been knocked out by direct hits, shrapnel, explosion of ready service boxes, and by fires on board.

It was about this time that control forward received its last communication from the bridge: "We're going down between them--give them hell!" But there was little besides fighting spirit left on the Quincy. Not one gun of either the main or 5-inch battery could fire, and the ship must already have been losing headway. No. I fireroom had been hit soon after the beginning of the action. A hit above No.2 fireroom about the time the Quincy started to turn right forced its abandonment. It was believed that while she was turning a torpedo struck between No.3 and 4 firerooms, probably about the same time the Vincennes was torpedoed. The No. I and 2 engine rooms continued to operate as long as there was steam. Then, because of the list which was developing to port, the crew left No.2 engine room. It appears that No.1 engine room was not abandoned before the ship capsized.

Soon after the 5-inch battery had been knocked out, an enemy vessel with mushroom top stacks passed about 2,000 yards to port, blazing at the Quincy with all her guns. Perhaps it was the same ship which Marine Gunner Jack Nelson saw pass very close along the port side of the Vincennes on a parallel course, raking her with fire.

It was probably very shortly after the Quincy's Control Forward received the last determined message from the Bridge that the latter suffered another hit which killed practically everyone in the pilot house. At about the same time a hit killed almost everyone in Battle II. By this time the boats on the boat deck were burning, the galley was in flames, the fire on the fantail was out of control, and the hangar and well deck were "a blazing inferno." Steam was escaping from No. I stack with a deafening roar. The forward battle lookout was hit, as was the 1.1-inch

--28--

clipping room. The resulting flames enveloped the forward control stations and reached up to the forward sky director.

"When the flames which engulfed the forward control station subsided, an officer went to the bridge to see what the orders were regarding firing and maneuvering. He found a quartermaster spinning the wheel, trying to turn the ship to port, who said that the captain had told him to beach the ship. He had no steering control. Just then the captain rose up about half way and collapsed dead without having uttered any sound except a moan. No others were moving in the pilot house, which was thick with bodies."26

Enemy fire had stopped when the control officer received this information and ordered the abandonment of the sky control stations. These had been inoperative for several minutes. By this time "the ship was listing rapidly to port, the forecastle was awash, water coming over the gun deck to port, and fires were blazing intermittently throughout the whole length of the ship. The party aloft found nothing but carnage about the gun decks, and dense smoke and heat coming from below decks." The ship was almost dead in the water and was going over when the gunnery officer, as the senior officer present, ordered abandon ship. A minute after this group got clear, "the ship capsized to port, the bow went under, the stern raised and the ship slid from view into the depths." This was about 0235 or soon after.

The Astoria, after swinging right to avoid the Quincy, moved northward for 4 or 5 minutes "under the heaviest concentration of enemy fire." Her engine rooms were being abandoned because of the fires above them and the ship was losing speed. She next swung left and was on a southwesterly course when the Quincy was seen on the port bow "blazing fiercely from stem to stern." The Quincy still had considerable way on and was swinging to the right. For a moment it looked as if a collision was inevitable, but the Astoria put her rudder hard left and swung clear. The Quincy could be seen coasting off astern and not long afterwards appeared to blow up.27

After clearing the Quincy, the Astoria steadied out on a course of 185°. By this time only turret II was still in commission, and only No. I gun of the secondary battery could still fire. As the Astoria steadied out, an enemy searchlight appeared to the east, just abaft the port beam. Lt.

_____________

26. Report of Lt. Comdr. Heneberger, senior surviving officer.

27. While the Quincy may not literally have blown up, it seems clear that there was a very heavy explosion aboard before she sank, which gave that impression to men on our other ships.

--29--

Comdr. Davidson, the communications officer, climbed up to the trainer's sight of turret II and coached its guns onto the target. The turret fired and the shells could be seen to hit.

This was probably the last salvo fired by any of our cruisers. Enemy fire had been diminishing and ceased shortly afterwards, at about 0215. It was fortunate, for at about that time the quartermaster reported that steering control was lost, and the engineroom advised that power had failed. Since the bridge had ceased to be useful as a control station, it was abandoned. While the ship drifted on toward the southwest the work of assembling the wounded began.

After the Vincennes had been torpedoed during her turn to the right, power for the main battery failed. Diesel auxiliaries were cut in for turrets I and III, but II had to go onto hand power. About the same time the forward magazines had to be flooded because of the progress of a fire in the vicinity. Steering control in the pilot house was lost and steering had to be shifted aft. Soon it was lost there too. The captain desired to turn left and attempted to do so by stopping the port engine, but communication could not be established with the engine room. At this time the explosion of another torpedo was felt. It was believed to have hit the port side at No. I fireroom.

During the turn to the right, only turret III had been able to fire, but as soon as turret II could bear to starboard it also joined in firing two salvos at a searchlight to the east. All director circuits were dead and fire was locally controlled. A hit was definitely seen, though the searchlight did not go out.

During these few minutes the ship was raked by a heavy fire from starboard. Turret I was prevented from joining in these last salvos by a hit on the starboard side of its barbette, which jammed it in train. One shell hit on top of turret II, while an 8-inch projectile penetrated its face and set fire to exposed powder. Powder in both turrets burned without exploding. Turret III, after one or two salvos, was also put out of action. Lt. Comdr. Adams, making his way along the gun deck about this time "noted many hits in the vicinity of the 5-inch battery and that there were many dead and wounded at each gun." Only No.1 gun was still firing. After the rest of its crew had been wiped out, Sgt. R. L. Harmon, USMC, was joined by Ens. R. Peters, and it was reported that the gun scored a hit on the conning tower of a submarine which was seen at about 400 yards distance.

--30--