The Navy Department Library

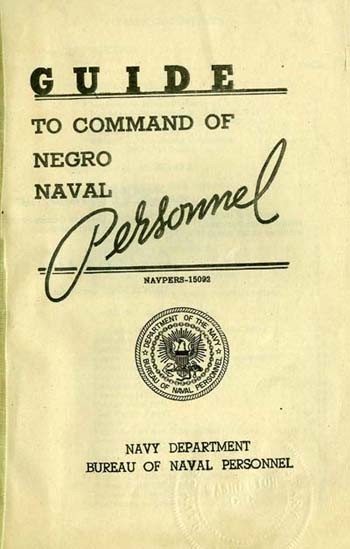

Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel

NAVPERS-15092

Navy Department

Bureau of Naval Personnel

Bureau of Naval Personnel,

Washington, D.C., 12 February 1945.

Bureau of Naval Personnel Pamphlet Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel, is published for the information and guidance of all Naval officers.

[signed]

[Rear Admiral] Randall Jacobs

Chief of Naval Personnel

Table of contents

1. The Negro in the Navy

Negroes in Naval History

Increased Participation in World War II

Racial Theories Waste Manpower

Attitudes and Policy

Handicaps Are Being Overcome

Responsibility is Local

2. Training and Assignment

Negro and White Test Scores

Use of the GCT

Training Reduces Handicaps

Negroes Eager to Learn

Utilization of Civilian Skills

Opportunities and Morale

Advancement in Rating

Satisfaction in Assignment

Unpopular Jobs

Selection for Sea Duty

Importance of Overseas Service

Need for Experiment

Be Skeptical About Ready Generalizations

3. Problems of Command

Attitudes Towards Service in the Navy

Attitudes Can Be Improved

Symbols That Irritate

Even Compliments may be Misunderstood

Racial Separation

Recreation

Community Resources

Transportation

Public Relations

The Negro Press

Rumors

Reprimands and Disciplinary Action

Venereal Disease

Control of Venereal Disease

Leadership

The Choice of Leaders

Mutual Confidence is Important

Negro Petty Officers

Indoctrination of Personnel

Alertness to Learn

The mission of the Naval Establishment is the protection of our country, its possessions and its interests. It includes neither social reform nor support of the personal social preferences of its personnel. In the accomplishment of this mission it is mandatory that the training and ability of all Naval personnel be utilized to the fullest.

It must be recognized that problems of race relations do exist and that they must be taken into account in plans for the prosecution of the war. In the Naval Establishment they should be viewed however solely as matters of efficient personnel utilization.

In general, the same methods of discipline, training and leadership that have long proven successful in the Naval Establishment will be found to apply to the Negro enlisted man. However, the effective administration and use of Negro personnel does call for special knowledge and techniques in some instances.

This is the result of the fact that Negroes as a group have had a history different from that of the majority of Naval personnel. Their educational opportunities have been restricted; the percentage of skilled workers is smaller; and participation in the life of the nation has been limited.

It is the purpose of this pamphlet to point out group differences in background and experience of significance to the officer with Negroes in his command, and to suggest approaches which may be of aid to him in the performance of his duties. The success or failure of each Commanding Officer in the administration of Negroes under him will be determined largely by the spirit in which he approaches the problem and the degree of attention given to it.

Section 1: The Negro in the Navy

Older Navy men today recall the service of Negroes aboard the larger combatant vessels from the turn of the century through the first World War. They served with distinction in the Steward's Branch, as Artificers, as Gunner's Mates, and in various other capacities.

This relatively recent service was not without precedent, for there have been Negroes in the United States Navy since the early days of the Republic. There were proportionally more Negroes in the Revolutionary Navy than in the Army of that time. Eighteenth and early nineteenth century experience on merchants ships and as fishermen prepared many for service in the Navy. Three of the four seamen removed from the Chesapeake in 1807 by the British frigate Leopard were American Negroes. There was a goodly number of Negroes among the men under Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry in the Battle of Lake Erie. Colored men participated generally in the naval engagements of the War of 1812.

For some time after the War of 1812, Negroes remained a relatively important element in the Navy, but they did not maintain this position long enough to play a similar role in the naval engagements of the later wars of the same century. It was not until World War II that they again entered the Navy in large numbers for general service.

Increased Participation in World War II

At the end of 1944 Negroes constituted about 6.0% of the entire enlisted Naval Establishment. The utilization and training of these men has presented new problems because there were comparatively few Negroes in the Navy as recently as the beginning of the present decade, and these few were largely concentrated in the Steward's Branch.

When the size of the Navy was curtailed following World War I, enlistment of Negroes was discontinued until 1932. Towards the end of that year, active enlistment of Negroes for the Steward's Branch was begun. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Navy announced on April 7, 1942, that Negroes would be recruited for general service ratings. Recruitment began two months later, on June 1. In February, 1943, the Navy discontinued its recruiting program and began procuring its enlisted personnel through Selective Service. With this change of policy, the numbers of Negroes in the Navy increased rapidly.

Racial Theories Waste Manpower

In modern total warfare any avoidable waste of manpower can only be viewed as material aid to the enemy. Restriction, because of racial theories, of the contribution of any individual to the war effort is a serious waste of human resources.

The Navy accepts no theories of racial differences in inborn ability, but expects that every man wearing its uniform be trained and used in accordance with his maximum individual capacity determined on the basis of individual performance.

It is recognized, of course, that Negro performance in Naval training and tasks on the average has not been equal to the average performance of white personnel. Explanation of this difference by resort to some theory of differences in natural endowment, however, leads only to confusion in which the potentialities of individuals become obscured.

It has been established by experience that individual Negroes vary as widely in native ability as do members of any other race. It is the Navy's responsibility to develop the potentialities of individuals to the extent that the exigencies of war require and permit.

It is worse than useless to deny or ignore the existence of personal racial preferences and prejudices. Such opinions and attitudes are no more rare among military than among civilian personnel, and must be taken into account just as any other human factor in the conduct of the Naval Establishment.

This does not mean, however, that such attitudes may be accepted as a controlling factor in the formulation of general policy or in day to day operations. It is encumbent on, and expected of each officer that his attitudes and day to day conduct of affairs reflect a rigid and impartial adherence to Naval regulations, in which no distinction is made between the color of individuals wearing the uniform. This pattern of thought should be passed on by each officer to the enlisted men, both White and Negro, under him.

Despite the handicaps of limited pre-induction educational and occupational opportunities and the hampering effects of unfavorable racial attitudes, Negroes are participating successfully in all types of shore activities in practically all ratings. Satisfactory Negro performance on District craft, the manning of two combat ships (a DE [escort ship] and a PC [submarine chaser]) with predominantly colored crews, and the partial manning of an appreciable number of other ships with Negroes has demonstrated the practicality of assigning colored personnel to sea duty.

Responsibility for the successful utilization of Negro personnel lies in the local activities and with local Commanding Officers. However, the Bureau of Naval Personnel, Division of Plans and Operations, is in a position to be of assistance to local authorities in meeting problems involved in the utilization of Negro personnel in their activities. Reports on experience and requests for aid will be welcomed.

As Negroes acquire additional skills and experience, their participation in the Naval prosecution of the war will broaden. It thus becomes an increasingly important duty to prepare for the full utilization of this important source of manpower. It is to this purpose that the remainder of this pamphlet is devoted.

Section II: Training and Assignment

Modern Naval warfare requires men with ability and training. The old popular notion that men with strong backs and weak minds were as effective as anyone in combat in the ranks is clearly false. There seems to be general agreement that the level of ability and information required for the successful completion of the fourth grade in the ordinary school is the minimum necessary for efficient integration in the Naval forces. Even men who are somewhat above this level must be supported, directed, and led by a great number of superior individuals.

Negroes entering the Navy during World War II have not been as good material on the average as white seamen. The average scores of the Negro recruits on the General Classification Test, and on tests in reading, mathematics, mechanical aptitude, mechanical knowledge and electrical knowledge, have been significantly lower than the average scores of white recruits. This fact is well known, but its meaning in terms of efficient military operation has been less clearly understood.

First, differences in the scores of Negro and white recruits on the General Classification Test, or on any other test, are not measures of differences in inborn ability. The GCT is not a test of native intelligence; scores on it should not be viewed as IQ's. The GCT is a classification test which shows the working level of the recruit at the time the test is given. It must be taken into account in the training and utilization of the men in your command, but it must not be regarded as a fixed ceiling above which men can not rise. In most cases, knowing the scores of your men will be helpful in the development of training plans and in the proper assignment of men. In some cases, however, a low GCT score, after further observation and investigation, may be found to reflect intelligence so low that the men should be discharged from the Navy.

Second, while average Negro test scores are appreciably lower than average white score on the same tests, individual Negro recruits achieve scores at all levels. Since there are proportionately fewer Negroes in the upper levels of qualities needed in the Naval Establishment, it is obviously all the more important that those who demonstrate superior ability, knowledge and skill be developed and utilized to the full extent of their potentiality. Such effort to avoid waste of manpower, however, should be carefully watched to check any tendency to lower standards in the selection of men for training and rating.

Third, experience within the Naval Establishment during World War II already has demonstrated that Negro test scores are heavily influenced by handicaps which can be overcome to a material degree even in the limited time available under the pressures of war. Negroes on the average have not made as good a showing in training schools and on the job as have white trainees, as might be expected in view of their limited educational and occupational background. They have, however, done remarkably well in practically all types of work when given proper training. Reports from activities generally agree that they have learned and carried on their duties with greater efficiency than had been anticipated. Activities that had been doubtful concerning the assignment of Negroes, but have approached the problem in a constructive and realistic manner, have commonly expressed satisfaction with their performance after reasonable time and effort for assimilation.

Fourth, Negroes have shown great desire to overcome their handicaps and qualify or advancement. Prior to the establishment of an official school for illiterates, thousands of Negroes at Great Lakes proved their eagerness to make up for the limitations of their backgrounds by attending remedial school in reading, writing and arithmetic one and one-half hours a day four days a week during their free time. Qualified teachers volunteered their time for this instruction. This earnest willingness to learn is an asset to the service which, if utilized properly, will work to the advantage of commanding officers.

Utilization of Civilian Skills

In time of war the Navy has always by tradition and of necessity depended on the heavy recruitment of civilians without seafaring experience for expansion to proper strength. The training of these civilians has naturally come to be largely a matter of direct or indirect use of skills acquired through civilian occupational experience. An armed force which will fight the most effectively and efficiently evolves only when men are doing the things for which their background and experience best fit them.

It is important to note, that there are Negroes who have had training and experience in practically all civilian occupations. Of the 534 different occupations listed in the Census of 1940, all but four were practiced by some Negroes. A survey of all armed forces inductees over a ten month period listed 428 specific occupational specialties acquired by enlisted men in civilian life. Approximately 85% of the 428 skills, trades and professions had been practiced or learned by Negro inductees, although in some the numbers were small. The scarcity of Negroes with skills in occupations of critical importance in the Naval Establishment requires that no qualified individuals be overlooked and that the development of needed skills through training be emphasized.

Proper development and utilization of individual abilities and civilian skills is essential not only because of Naval needs for trained men for specific jobs but also because it is a basic factor in military morale. All men should feel that their officers are concerned with their natural desire to increase their military efficiency. Like other Americans, the Negro wants widening opportunities. Indifference to individual potentialities, and policies which summarily forbid requests for changes in assignment or for specialist training, impede the effective utilization of personnel and create discontent. Enlisted men, white and Negro alike, are notoriously quick in sensing any lack of positive interest in their advancement. Moreover, the Negro has been made extra sensitive in such matters by his civilian experience.

It is the policy of the Navy Department that no discrimination as to race shall be allowed to influence the nomination of candidates for advanced school training. When Negro personnel are qualified under existing regulations and directives, they shall be given the same consideration as white personnel and will be assigned to schools in the same manner and on the same basis. (Bupers. Circ. Ltr. No. 194-44 dated 10 July 1944).

Opportunity for advancement is as important to morale and efficiency as is assignment in accordance with training and skill. Navy Department policy is clear that Negroes are to be rated on the same basis as white personnel and that Negro ratings shall move upwards in the same manner as any other ratings. (BuPers Ltr., Pers-106-3(3) dated 12 July 1943). While the morale aspects of this policy are here stressed, it may be observed that it is in fact no more than a statement of ordinary good management practice.

In spite of the fact that Navy policy covering advancements in rating for Negroes is exactly the same as for white personnel, Negroes have been found doubtful about the opportunities for advancement open to them. In many instances their failure properly to understand Bureau and activity rating programs and policies has resulted in imagined inequalities and injustices, with consequent dissatisfaction and lowering of morale. It is, therefore, important that Bureau and activity training programs and rating policies be thoroughly explained to Negro personnel and that care be taken to make it clear that opportunities are the same for all.

That all graduates of Class "A" schools must be used in the rates and for the types of work for which they have been trained has been declared to be fundamental Navy Department policy. Apart from the fact that such use is in general obviously in accordance with the principles of military efficiency, in the case of the Negro any deviation is likely to take on special significance.

On one occasion an issue arose promptly when a complement of General Service Negroes of high morale and superior grade were temporarily put at work of a Steward's Mate character in the interval following special training and prior to the availability of their ship. The fact that members of a white group also waiting for their ship were assigned to similar temporary work did not keep the issue from lowering morale. This incident illustrates the problem of special Negro sensitivity in occupational assignment growing out of a past history of vocational restriction. Alertness is required to avoid inadvertent and needless cause for suspicion of discrimination in assignment.

Negro seamen and their civilian relatives and friends recognize the higher value generally placed on sea duty. They also recognize that the recency of the beginning of their recruitment for general service and the general problems of their utilization in the Navy have required that the bulk of their service be at shore stations. They are, however, concerned that as many as possible of their fellows be given opportunity to serve on ships. Occupational restriction in civilian life to less desirable jobs has given extra significance to the chance for service in all parts of the Naval Establishment.

Restrictions prior to 1942, practically limiting the service of Negroes in the Navy to the Steward's Branch are still a source of sensitivity to the Negro. Even today, when induction for general service is open to all, service in the Steward's Branch or as Cooks and Bakers is far from popular.

The business of the commissary is related in the thinking of the Negro to traditions of an inferior grade of occupation. There consequently must be no degree of pressure, or temporary over-persuasion, or misunderstanding in transfers of men to this kind of work. Both in the training stage and later, every effort should be made to offset the unpopularity of this kind of work by building morale in the commissary and Stewards groups.

Similar effort must be made to maintain the morale of Negro seamen in other activities also traditionally associated in their minds with inferior occupational status, particularly those involving heavy and relatively unskilled manual labor as a supply and ammunition depots.

Hard manual labor must be done in the normal operation of the Naval Establishment, and both white and Negro personnel are doing it. It is not good personnel procedure, however, to dismiss the matter with merely a statement of its inevitability for all races. There is an extra problem in the case of the Negro seaman of avoiding any basis for the suspicion that he is given such work because he is a Negro. This can be accomplished without coddling by making certain that he receives equitable treatment on the job and that he is aware of the importance in the war of the work he is doing, and that he understands that white personnel are performing the same type of duty.

Negroes, for some time, have been making up a large proportion of the crews of local defense, harbor and patrol craft. Some of these vessels are commanded by Negro petty officers. The Naval Districts have come to rely as a matter of course upon the satisfactory performance of Negro members of the crews of these vessels. Negroes themselves have great satisfaction in their success in this work.

The manning of a DE and a PC with predominantly Negro crews has been entirely satisfactory. Both ships are now successfully performing escort duties. The Districts designated men for these crews with the view, shared by the men themselves, that selection was an honor for the past good records. Even though comparatively few Negroes are involved, there is reason to believe that this step by itself has had an appreciable beneficial effect on the morale of Negro enlisted men in general.

In line with the present policy of reducing the on board complement of shore establishments, the partial manning of 25 auxiliary ships of the Fleet with Negro enlisted personnel was directed a short while after the shakedown cruises of the DE and PC mentioned above. The number of Negroes for general service was limited to a maximum of 10% of the general service complement of each ship. Ratings assigned make up a fair cross-section of the rating groups included in the ships' complements. The Negro increments of these ships are administered in accordance with the established policies and procedures already in effect aboard each individual ship at the time of their assignment. This procedure has produced no apparent ill effects, and will be continued and expanded.

Importance of Overseas Service

Service at bases outside the continental United States should also be mentioned as an opportunity for the utilization of Negro personnel under circumstances which are favorable to Negro morale. To the uninitiated, there is more popular glory in even the hardest manual labor in the South Pacific or some other distant area than in lighter tasks back home. Many Negroes are now serving at such bases in the SeaBees and in base companies. Transfer to a combat zone should be and is generally regarded as a reward for exemplary conduct and performance of duty.

The training and assignment of Negro personnel is a matter of special concern to responsible officers. Ultimate responsibility for working out solutions for specific questions must and does rest with local commanding officers. It is recommended that carefully planned and controlled experiments toward the maximum and joint utilization of Negro and white personnel be initiated. Some will be failures, otherwise experiment would not be needed. Failures under proper control, however, are not so likely to be serious as indifference to the problems, or inertia.

Be Skeptical About Ready Generalizations

More dangerous than careful experiment is reliance on untested theories. There are many current theories about the Negro can or cannot learn, about what work he can or cannot do, about the likelihood of conflict or cooperation between Negro and white personnel in school or on the job, and about all other questions with which an officer may be faced. All of them should be viewed with skepticism until there is evidence that they have been thoroughly tested under practical conditions as found in the Naval Establishment.

Section III: Problems of Command

The same command techniques are effective for Negro and for white enlisted personnel. In addition to thorough knowledge of his technical duties, the basic requirements of command are that the officer know his men and hold their confidence.

In the case of the Negro, this means that the officer must be keenly aware that special questions growing out of the Negro's history in the United States will be encountered. At the same time, he must never assume that all Negroes are any more alike with regard to a particular characteristic than, for example, all men born in New York City.

Attitude Towards Service in the Navy

The Negro has long resented his period of exclusion from general service in the Navy. Now that he has been accepted other than for commissary duties he remains conscious of the fact that his admission was not without reluctance and is doubtful about the possibility of participation in accordance with ability.

Assignment to the Steward's Branch and as Cooks and Bakers is looked on generally with suspicion as reflecting a belief that he is fit only to do the traditional work of food handling. Work at NAD's [Naval Ammunition Depots] and other heavy labor also brings up the idea that he is kept as much as possible in the less attractive types of work.

Such sensitivity may seem unreasonable to officers who are doing their best to utilize manpower in accordance with their considered judgment of war needs, individual abilities and other circumstances over which they have no control. It is, however, a natural reaction for a group that has had generations of experience with occupational restriction.

Although colored, like white enlisted men, frequently are unwilling or unable to admit personal shortcomings as adequate reason for failure to receive desired assignments and promotions, alertness on the part of officers in the recognition of individual merit is quickly recognized by the men, and avoids giving any basis for discontent.

Knowledge that white enlisted men of comparable ability are assigned to tasks similar to those being performed by Negroes is also of great benefit to Negro morale. Indoctrination in the military importance of arduous duties without glamor is helpful. Finally, it is a good principle that the less satisfaction and prestige men can get out of their work, the more effort should be made to provide off-duty recreational facilities and to encourage their use.

The Negro's skepticism about his role in the Navy has been stressed because it is an important factor in his effective utilization. It may also be mentioned that this skepticism has probably been costly to the Navy in another way, for there is reason to believe that a goodly number of more capable and skilled Negroes have avoided induction into the Navy because they did not believe they would have the opportunity to make their best contribution. In view of the need for leadership among the men, the loss of even a few such men has been serious.

High or low morale has been said to result from a lot of little things. Among the little things of great importance to Negroes are words, jokes and characterizations which white people use on occasion unthinkingly. They can be such sources of irritation that leadership becomes difficult, and continued use of them has on several occasions invoked serious incidents.

Negroes prefer to be referred to in their individual capacities as Americans without racial designation. The word "nigger" is especially hated and it has no place in the Naval vocabulary. Negroes are suspicious that the pronunciation of the word Negro as though it were spelled "Nigra" may be a sort of genteel compromise between the hated word "nigger" and the preferred term "Negro." The terms "boy," "darkey," "coon," "jig," "uncle," "Negress" and "your people" are also resented. If it is necessary to refer to racial origin, "Negro" and "colored" are the only proper words to use.

A safe rule on jokes is to avoid those which depend for their laugh on the stereotype, on the "stage Negro", or on a burlesque of any kind. Of course Negroes tell them among themselves and use terms about themselves which, if used by others, would be considered offensive, but they are not so likely to misunderstand their own motives in doing so.

Even Compliments may be Misunderstood

It is easy to understand why Negroes do not like words or humor symbolizing supposed racial traits or their traditional restricted role in the America community. It is more difficult to appreciate the fact that even well-intentioned and admiring emphasis on supposed advantageous qualities similarly may be cause for annoyance.

The annoyance of this type most likely to occur in the Naval Establishment is the entirely friendly insistence that Negroes contribute to both formal and informal entertainments by showing off their alleged superior abilities in singing, dancing, boxing, or burlesque theatricals.

Although individual Negroes have been outstanding in these forms of entertainment, there is no scientific evidence of inherited racial qualities giving Negroes an advantage in these activities over other races. Perhaps their comparative success in athletics and entertainment has resulted from their being permitted a more normal participation in these fields. They have been pushed forward to do their popularly ascribed specialties so often that in many instances they have become suspicious that tap dancing, guitar playing, the singing of spirituals, and the like, may now be symbols of their special racial status.

Some Negroes can, and would like the chance to put on performances not characterized as Negro. It is a good rule to let all volunteer entertainers decide for themselves what to offer the audience. Under such freedom, no doubt the programs will be much the same as though the customary pressures had been exerted. The privilege of free choice, however, is appreciated.

The idea of compulsory racial segregation is disliked by almost all Negroes, and literally hated by many. This antagonism is in part a result of the fact that as a principle it embodies a doctrine of racial inferiority. It is also a result of the lesson taught the Negro by experience that in spite of the legal formula of "separate but equal facilities," the facilities open to him under segregation are in fact usually inferior as to location or quality to those available others.

The accomplishment of the assigned mission through the harmonious and efficient use of existing equipment and facilities should always be the objective of the commanding officer. Joint use of facilities is frequently possible and desirable, particularly where the ratio of Negro to white personnel is not high. Signs restricting the use of facilities to one or the other of the races are especially offensive to Negroes and under no circumstances should they be used in the Naval Establishment. Difficulties may be minimized if it is realized that in most instances objections voiced by white personnel emanate from a small minority and are usually in the nature of a test of the commanding officer's mettle. If the policy laid down by the commanding officer is impartial, fair, and reasonable, the men, white and Negro alike, are quick to realize it and to accept the situation providing it is clear that the policy will be enforced.

A policy of careful experimentation on the part of commanding officers, with emphasis away from compulsory separation, will usually enable them to arrive at the proper solution when faced with a problem of race relations. Final decisions as to the course to be followed within the broader pattern of Naval regulations are best left to the individual command.

The necessary restrictions of military service on individual freedom emphasize the role of recreation. Facilities for the enjoyment of free time on station and on liberty are of extra significance for the morale of Negro enlisted men.

On station, the commanding officer can see to it that facilities are adequate and in good order. Attention to the full and harmonious use of facilities with the guidance and aid of Specialists (A) and others with skill and experience in the direction of group recreation is recommended. Frequently such leaders can be found within groups of Negro enlisted men, but if not, effort should be made to obtain personnel suitable for the purpose through official channels.

The provision of adequate physical facilities on station has been recognized as important in reducing racial tensions and should be checked with particular care in commands where the races are mixed. In any recreational racial separation seems necessary because of local circumstances, experience suggests that the wisest course of action is to minimize the extent to which it rests upon regulation and formal compulsion.

The extra importance of on station recreational facilities for Negro personnel is a consequence of the fact that in many localities the quality of amusement provided by civilian establishments reflects the generally limited status of the Negro. Only in the larger cities are there likely to be found theatres, stores, restaurants, other commercial establishments, and a community life available and suitable for the normal needs of appreciable numbers of Negro service men. Much can be done to increase wholesome recreational facilities both officially through such national agencies as the USO [United Service Organizations] and the Office of Community War Services, and informally through cooperation with churches, schools, Y.M.C.A.'s [Young Men's Christian Association], Y.W.C.A.'s [Young Women's Christian Association], athletic clubs, local war service commissions, various civic groups and outstanding citizens, especially Negroes.

Transportation facilities are becoming increasingly inadequate in many communities. In areas requiring the separation of white and Negro passengers in public conveyances, the problem of getting from one place to another is likely to be particularly difficult for the Negro sailor. In some localities, civilian bus drivers have been known to refuse to stop for Negro Naval personnel. Crowded public conveyances have become one of the most common sources of interracial irritation.

It is the definite responsibility of local Commanding Officers to find the best possible solution to this problem of public transportation for their men. Through close cooperation with bus companies, the staggering of liberty hours, and use, where authorized, of Naval trucks and busses, much can be done to alleviate individual situations. On troublesome local routes, good results have been obtained by assigning Shore Patrol to the busses and trains not only to keep order, but also to protect Negro sailors from discrimination.

Negro civilian attitudes towards the Navy are of concern to all Naval personnel. They affect the quality of the colored men who express preference for the Navy in the process of induction; they influence the degree of eagerness or reluctance with which the inductee enters the Navy; and they are a major factor in the morale of the men as they work at the jobs the Navy gives them to do.

Material concerning the Negro in the Navy disseminated through the printed page, the motion picture and the radio can help or hinder the administration of Negro Naval personnel. Stories, pictures, articles and editorials which portray the Negro sailor in stereotyped roles or as somehow unique among Naval personnel, develop hampering attitudes. Publicity material that shows the Negro as a sailor engaged in activities in which anyone might take military pride gain helpful public support and increase working morale.

Publicity information issued through the press, the theatre and over the radio is, however, only a part of the stuff of public relations. What men experience and see for themselves and spread through friends is frequently more convincing. Basically, people 's attitudes, white and colored alike, towards the Negro in the Navy depend on the fairness and efficiency of the officers in command and on the Negro's efficiency in his duties.

Some concern has been expressed because a good proportion of Negro enlisted men read Negro newspapers which are severely critical of the Navy or because they belong to organizations working for the improvement of racial conditions. It is apparently thought that such contacts may be a source of low morale. This is a doubtful assumption. Commanding officers who have been most successful with colored personnel commonly subscribe to Negro newspapers through the Welfare Fund.

It is true that Negro publications are vigorous and sometimes unfair in their protests against discrimination, but it is also true that they eagerly print all they can get about the successful participation of the Negro in the war. Negroes have to buy them if they want to read Negro news. Censorship and repression of such interests is not in the American tradition. It cannot be made effective, and has the reverse effect of increasing tension, and lowering morale.

Rumor and misunderstanding have contributed most seriously to public criticism of the Navy's policies and practices regarding the Negro. They have also been a critical factor in every instance of racial tension leading to incidents requiring disciplinary action. Investigation of such incidents suggests that in every case prompt action to check rumor and misunderstanding by seeing to it that the full and true circumstances were known to the men would probably have prevented or minimized open disturbance and restored morale during the period while any needed corrective administrative action was being taken.

Reprimands and Disciplinary Action

Most Negroes are sensitive to reprimands and punishment from whites. Because of this, disciplinary action is frequently construed as being directed against them because of their race, rather than as punishment for the act.

Any tendency on the part of commanding officers to be more lenient in the application of corrective measures because of his sensitivity would be a grave mistake and such action is not advocated. Adherence to the same standards of behavior should be expected and demanded of all personnel. Care should be taken, however, to assure that the offender thoroughly understands the correlation between the offense and the disciplinary measures taken.

There is a widespread belief among Negroes that both civilian and military police are commonly more severe with Negro than with white service personnel. The Navy has made no survey to ascertain the validity of this belief, although undoubtedly in some instances it is substantiated by fact. Regardless of the truth or falsity of the claim of police unfairness, the existence of such a widespread belief is an indication of a potential source of danger.

It is the responsibility of the Navy and of each individual Commanding Officer to make certain that the rights of all men in uniform are observed. In the application of civil and military laws and regulations, the same procedures and treatments should apply to all personnel. No compromise with this thought can be acceptable.

The venereal disease rate usually has been found to be much higher among Negro than among white Naval Personnel. A high venereal rate at an activity constitutes a menace to the morale of the entire group, as well as to their general health and to their work effectiveness.

The general Naval policy of handling venereal disease cases as medical and not disciplinary cases, so long as they are reported, is, of course, to be followed. The importance of vigorous programs both for the treatment of individual cases and for the prevention of infection cannot be overestimated

The principal methods of reducing the venereal disease rate for both white and Negro Naval personnel are: (1) reducing the rate of exposure to infection, (2) increasing the use of prophylaxis, and (3) lessening the risk of infection from adjacent communities. Preventive measures should include close cooperation with local authorities and representatives of other national agencies concerned with the control of venereal disease. Regulating prostitution has been shown many times to be an ineffectual method of controlling disease. An important aid to venereal disease control is healthy recreation on station and in nearby communities. A sustained educational program within the Naval group is essential.

Under no circumstances should Commanding Officers take the position that the matter is relatively hopeless, for it has been demonstrated that with proper planning venereal disease among Negro military personnel can be satisfactorily controlled.

It has been the Navy's experience that the effectiveness of Negro Naval personnel is determined primarily by the kind of leadership afforded. In the majority of cases involving unusually difficult problems with Negro personnel, the trouble can be traced to poor leadership.

Efforts of the Commanding Officer to apply all the techniques of good leadership will be of little value if the junior officers under him destroy the effect of his work through actions resulting from disinterest, lack of knowledge or personal prejudice. Careful selection of junior officers and close observance of their performance of duties are therefore important. (BuPers Conf. Cir. Ltr 44-90, dated 7 August 1944).

In selecting officers to supervise Negro personnel, their abilities as leaders and their personal attitudes, s well as their technical professional qualification, should be considered. It has not been the experience of the Navy that officers from any one section of the country are better suited for assignments over Negro enlisted men than are those from other sections. The ability and interest of the individual officer will determine the measure of success attained.

Mutual Confidence is Important

Men must have confidence in their officers. There is a tendency among Negroes to be distrustful of white persons in positions of authority over them. There is also a tendency towards unwillingness or even inability to speak frankly and fully to white persons about matters of mutual concern. This distrust and reserve are in the nature of protective devices developed in the course of living under conditions where rebuff and discrimination seem always a possibility. They present special problems to the white officer in command of Negro personnel in understanding his men and gaining their confidence.

To earn the confidence of his men, the officer must be prepared to stand firmly behind them in all matters of controversy concerning which they are in right. He must know them as individuals, learn their names, recognize them on sight, and be familiar with something of the work they are doing. Complete frankness at all times pays large dividends, since Negroes by long experience have been schooled to look for and see through any sham. Confidence can only exist where there is mutual understanding and respect.

The Commanding Officer who fails to utilize to the fullest the leadership qualities of Negroes under his command in the supervision of other Negroes is not likely to obtain the best results. Contrary to a fairly general belief, it has been found that Negro Naval personnel respond readily to good Negro leadership.

One reason for the effectiveness of Negro petty officers is that in their relations with the men questions of race and racial discrimination are not involved. Experience has taught, for example, that colored personnel can be directed and disciplined with less likelihood of dissatisfaction by Negro than by white petty officers, provided the former are well selected and competent. This is understandable in view of the tendency on the part of some colored men to weight orders or rebukes, looking for discriminatory implications.

Need for Negro petty officers should not be allowed to cause any relaxing of standards in their selection, training, assignment and advancement. The costs of such deviation from general policy are almost certain to be greater than the gains.

Relations between an officer and his men cannot be satisfactory if the relations between his men and other enlisted personnel with whom they are in contact are not harmonious. One of the most important factors contributing to a good relationship between Negro and white personnel is the proper indoctrination of both groups at the beginning of their association, and thereafter whenever there is evidence that it is needed.

Prior to the arrival of Negroes at a command, white personnel should be informed of their assignment. The status of the newcomers as Naval personnel who are to be treated as such should be made clearly understood. Experience has shown that when white groups clearly understand what is expected of them as a matter of policy of the command, incidents of racial friction are materially reduced in number.

Similar indoctrination should be given all Negro groups by a responsible officer upon their arrival. This should be done in a straightforward manner. Any local laws or customs which may be a source of trouble if disregarded by individuals can be tactfully touched on, but emphasis is not likely to be needed in view of Negroes' general awareness of such conditions. Unnecessary emphasis may cause resentment through misinterpretation.

Indoctrination for Negroes primarily should be in terms of Naval regulations, duties, customs, and responsibilities, to the end that the men will understand and have confidence in their role and status as members of the Naval Establishment.

The problem of the Naval officer in command of Negro personnel is not one of solving overall racial and social problems. Rather it is to learn and use techniques which will enable him to utilize Negro Naval personnel effectively.

The successful supervision of Negro personnel requires a specific knowledge of the attitudes, likes and dislikes, history and present circumstances of the American Negro. Few people who have not studied the subject have this knowledge. It cannot be assumed to be a natural product of the contacts between members of the two races in ordinary life.

In the absence of any possibility of formal study, it is recommended that Naval officers in command of Negroes read such publications concerning Negroes as they can lay their hands on, including Negro newspapers, engage in frank discussions of the problems they encounter, observe carefully the day to day happenings in and about their command, take advantage of opportunities for careful experiment, and maintain thoroughly open-minded approach. By so doing, they will learn much that will contribute to their success in supervising the men under them.

[END]