The Navy Department Library

Landing Operations Doctrine

United States Navy, FTP-167

Landing Operations Doctrine

United States Navy

1938

F.T.P. 167

Office of Naval Operations

Division of Fleet Training

United States

Government Printing Office

Washington: 1938

Contents

CHANGE No. 1 to

FTP-167

Navy Department,

Headquarters, Commander in Chief,

U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

Washington, D.C., May 2, 1941.

Landing Operations Doctrine, U.S. Navy, 1938 (FTP-167) was approved on August 5, 1938, for the use and guidance of the naval service, and was made effective on receipt. This publication supersedes "Tentative Landing Operations Manual" of 1935, all copies of which were ordered destroyed by burning.

FTP-167 is intended as a guide for forces of the Navy and Marine Corps conducting a landing against opposition. It considers, primarily, the tactics and technique of the landing operation and the necessary supporting measures therefor. Purely naval or military operations are dealt with only to the extent to which these operations are influenced by the special nature of amphibious warfare.

Change No. 1 to FTP-167 is a complete revision of FTP-167 except for the title page. All pages of FTP-167 (except the title page) bearing Registered Nos. 1-1500 are to be removed and destroyed by burning. Change No. 1 shall be inserted in FTP-167 bearing Registered Nos. 1-1500.

FTP-167, bearing Registered Nos. 1501 and above, has Change No. 1 and the title page entered in process of preparation.

After entry of Change No. 1 to FTP-167 in any copy bearing Register Nos. 1-1500, or after receipt of FTP-167, Register Nos. 1501 and above, the fly leaf receipt shall be executed and forwarded to the Chief of Naval Operations (D.N.C. Registered Publication Section), or District Library, as appropriate.

FTP-167 is a [formerly] confidential registered publication. It shall be handled and accounted for in accordance with the instructions contained in the U.S. Navy Regulations and the current edition of the Registered Publication Manual. It is assigned Class C stowage. It shall not be carried in aircraft for use therein.

It is forbidden to make extracts from or additional copies of this publication without specific authority from the Chief of Naval Operations, except as provided for in the current edition of the Registered Publication Manual.

H.R. Stark,

Admiral, U.S. Navy,

Chief of Naval Operations.

--(iii)--

CHANGE No. 2 to

FTP-167

Navy Department,

Headquarters, Commander in Chief,

U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

Washington, D.C., August 1, 1942.

Change No. 2 to Landing Operations Doctrine, U.S. Navy, 1938 (FTP-167) is approved. Change No. 2 has been incorporated in the following numbered pages which are transmitted herewith:

Pages:

| VII 9 14 34 35 36 41 42 43 45 46 47 48 49 50 |

51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 84 85 89 93 |

95 98 103 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 170 171 174 175 178 |

181 182 200 214 218 220 228 239 240 241 242 243 244 |

These pages will be inserted immediately on receipt, and superseded pages will be destroyed by burning, no report of destruction being required.

/S/ R.E. Edwards,

for and in the absence of

E.J. King,

Admiral, U.S. Navy,

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and

Chief of Naval Operations.

--(iv)--

COMINCH FILE

FFI/A10

Serial: 02593

CHANGE No. 3 to

FTP 167

Navy Department,

Headquarters of the Commander in Chief,

UNITED STATES FLEET

Washington, D.C., 1 August 1943.

| From: | Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations. |

| To: | All Holders of F.T.P. 167. |

| Subject: | Change No. 3 to F.T.P. 167. |

| Enclosure: | (A) New pages nos. IVa, IVb, VII, VIII, IX, X, 111 to 150 (inclusive), 239 to 244 (inclusive). |

1. Change No. 3 to F.T.P. 167, Landing Operations Doctrine, U.S. Navy, 1938, is promulgated herewith and is effective upon receipt. It is [formerly] confidential and nonregistered and shall be stowed, transported and handled in accordance with the current edition of the Registered Publications Manual.

2. This change shall be entered as follows:

Pen changes:

Par. 223c, p. 38 - change HYPO to HOW; change PREP to PETER.

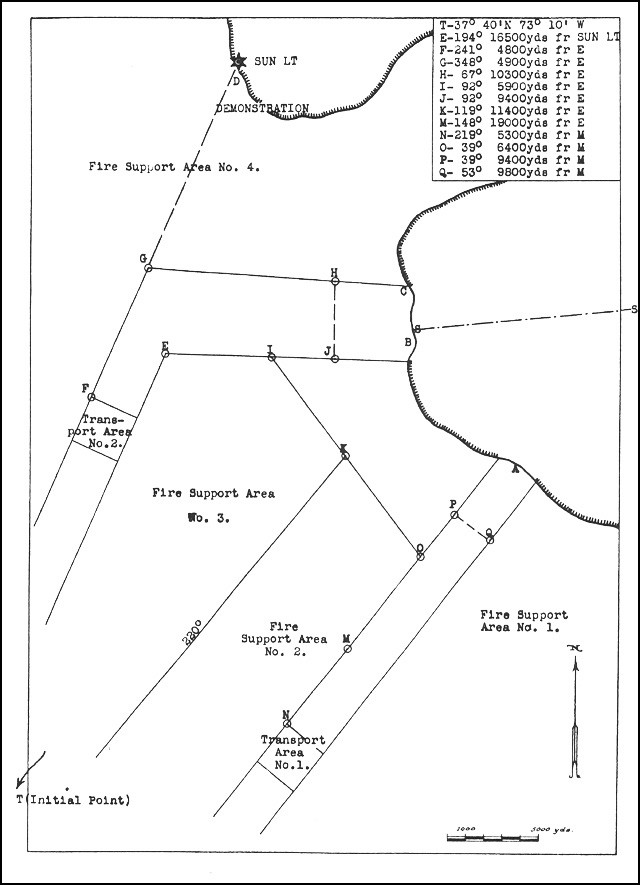

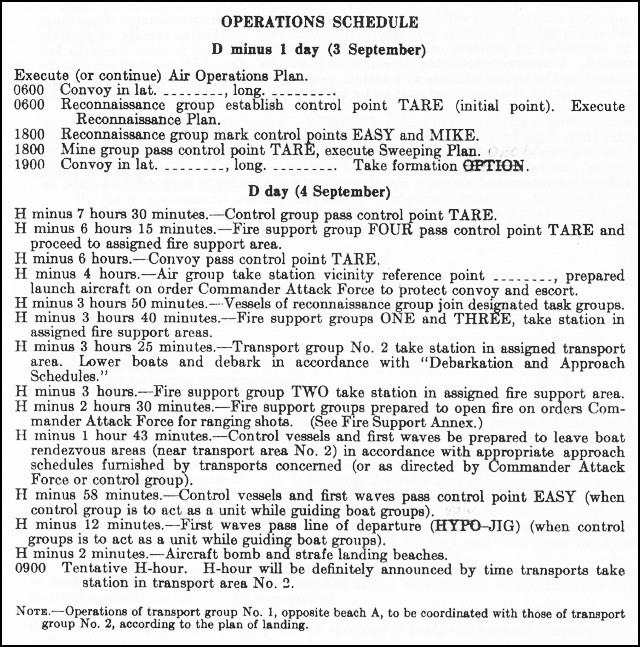

Fig. 2, p. 41 - change OPTION to OBOE; change HYPO to HOW.

Par. 230, p. 42 - change "Section VI" to "Section IV."

Par. 322, p. 54 - insert "(FTP 207)" at end of paragraph.

Fig. 16, p. 91 - change "Affirm" to "Able."

Fig. 17, p. 93 - change CAST to CHARLIE in two places.

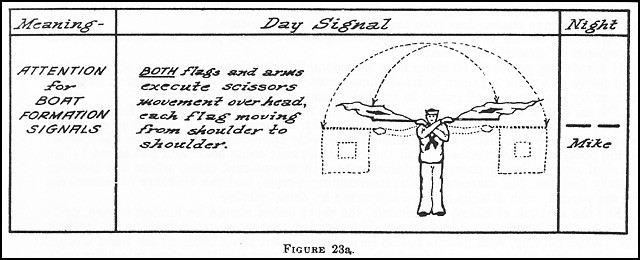

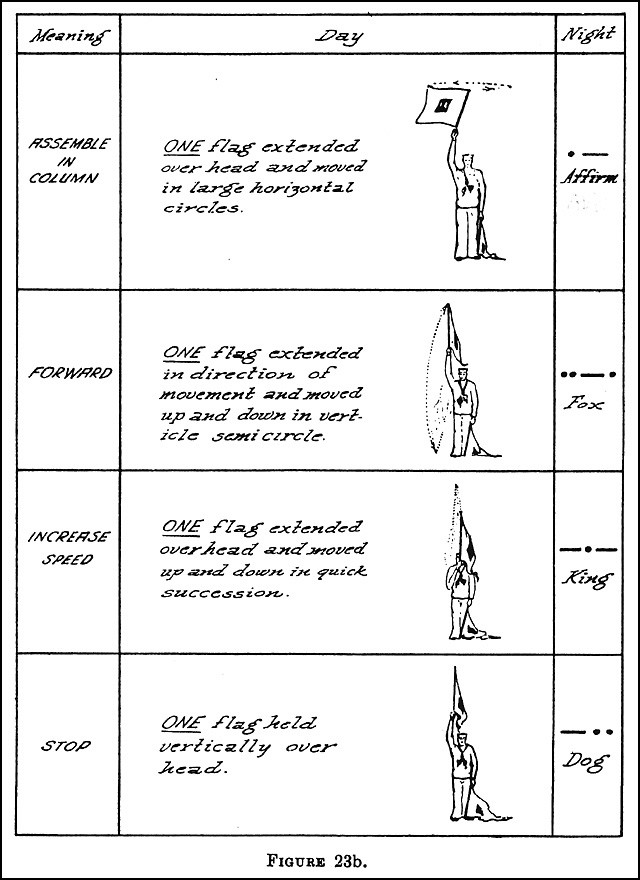

Fig. 23b, p. 107 - change "Affirm" to "Able."

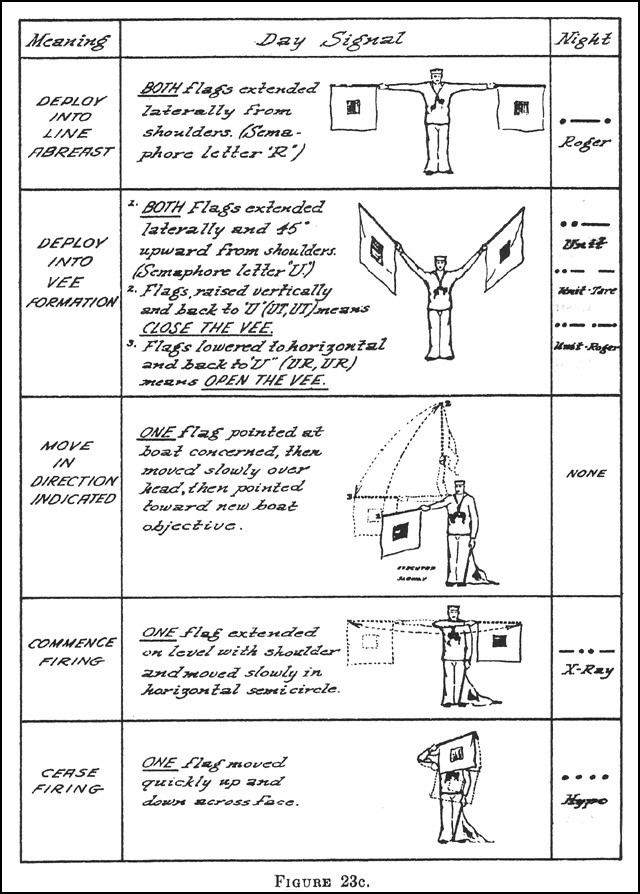

Fig. 23c, p. 108 - change "Unit" to "Uncle" in three places; change "Hypo" to "How."

Par. 615b, p. 154 - change "par. 553" to "par. 522."

Par. 624c, p. 157 - change "par. 543" to "section IV, Chapter V."

Par. 637a, p. 159 - at end of first sentence, strike out "as described in section III, Chapter V."

Par. 811a, p. 178 - change "see pars. 542, 552c, and 731" to "see section IV, Chapter V."

Par. 833b, p. 188 - change "par. 543" to "section IV."

a. Insert the numbered pages transmitted herewith as Enclosure (A). Superseded pages will be destroyed by burning, no report of destruction being required.

/s/ R.S. Edwards,

Chief of Staff.

--IVa--

[BLANK]

--IVb--

CORRECTION PAGE

| Change No. | R.P.M. | Date entered | Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||

| (In registered numbers 1501 to 3500 Change No. 1 was entered in preparation) | |||

| 2 | November 1942 | ||

| 3 | 16 October 1943 | /s/ M.V. Heesaker, Y 3/c | |

--(V)--

[BLANK]

--(VI)--

LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES

| Subject matter | Page No. | Change in effect |

|---|---|---|

| Title Page | --- | Original. |

| Promulgating letter | III | Ch. 1. |

| Promulgating letter | IV | Ch. 2. |

| Promulgating letter | IVa | Ch. 3. |

| Correction Page | V | Original. |

| List of Effective Pages | VII-VIII | Ch. 3. |

| Contents | IX | Ch. 3. |

| Text | 1-8 | Ch. 1. |

| 9 | Ch. 2. | |

| 10-13 | Ch. 1. | |

| 14 | Ch. 2. | |

| 15-33 | Ch. 1. | |

| 34-36 | Ch. 2. | |

| 37-40 | Ch. 1. | |

| 41-43 | Ch. 2. | |

| 44 | Ch. 1. | |

| 45-61 | Ch. 2. | |

| 62-83 | Ch. 1. | |

| 84-85 | Ch. 2. | |

| 86-88 | Ch. 1. | |

| 89 | Ch. 2. | |

| 90-92 | Ch. 1. | |

| 93 | Ch. 2. | |

| 94 | Ch. 1. | |

| 95 | Ch. 2. | |

| 96-97 | Ch. 1. | |

| 98 | Ch. 2. | |

| 99-102 | Ch. 1. | |

| 103 | Ch. 2. | |

| 104-110 | Ch. 1. | |

| 111-150 | Ch. 3. | |

| 151-160 | Ch. 1. | |

| 161-167 | Ch. 2. | |

| 168-169 | Ch. 1. | |

| 170-171 | Ch. 2. | |

| 172-173 | Ch. 1. | |

| 174-175 | Ch. 2. | |

| 176-177 | Ch. 1. | |

| 178 | Ch. 2. | |

| 179-180 | Ch. 1. | |

| 181-182 | Ch. 2. | |

| 183-199 | Ch. 1. | |

| 200 | Ch. 2. | |

| 201-213 | Ch. 1. | |

| 214 | Ch. 2. | |

| 215-217 | Ch. 1. | |

| 218 | Ch. 2. | |

| 219 | Ch. 1. | |

| 220 | Ch. 2. | |

| 221-227 | Ch. 1. | |

| 228 | Ch. 2. | |

| 229-238 | Ch. 1. | |

| Index | 239-244 | Ch. 3. |

| Blank pages ii, ivb, vi, 52, 53, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 110, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 160, 172, 238, 244 | ||

Chapter I

Landing Operations - General

| Section | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Objectives of landing operations | 1 |

| II. | Forces to be employed | 4 |

| III. | Advance forces | 5 |

| IV. | Main and subsidiary landings | 7 |

| V. | Beachheads | 9 |

| VI. | Selection of landing areas | 12 |

| VII. | Scheme of maneuver | 15 |

| VIII. | Comparative times of landing | 26 |

| IX. | Plans and orders | 28 |

Section I

Objectives of Landing Operations

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 101. | General objectives | 1 |

| 102. | Types of bases | 1 |

| 103. | Selection of a base | 1 |

| 104. | Securing a base | 1 |

| 105. | Denying a base | 2 |

| 106. | Illustrative diagram - securing and denying a base | 2 |

| 107. | Landing raids | 2 |

| 108. | Land in the tactical control of sea areas | 2 |

| 109. | Small wars | 2 |

a. Landing operations may be conducted by naval forces for the following general purposes:

For securing bases for our fleet or components thereof.

For denying bases or facilities to the enemy.

For bringing on a fleet engagement at a remote distance from an enemy main base by causing the enemy fleet to operate in protection of the threatened area.

To cause a dispersion of the enemy fleet by threatening areas vital to his plan of campaign.

For protection of life and property in connection with small wars.

For sabotage.

For the conduct of such other land operations as may be required in the prosecution of the naval campaign.

b. The purpose for which a landing operation is conducted in any given area will influence the nature of the operation, its specific objectives, and the forces to be employed.

102. Types of bases. -

a. Classification and definitions of the various types of naval bases will be found in the War Instructions, U.S. Navy.

b. An advanced base is one established in an advanced location by the operating forces for wartime use. An advanced base established for temporary use in support of landing operations is called a supporting base.

103. Selection of a base. -

a. In the selection of a base consideration must be given to the following factors:

Suitability of the area for the type of base it is proposed to establish.

Geographical location in relation to the theater of operations of the fleet.

Defensive strength and natural resources available.

The operations afloat and ashore required to seize and hold the base.

b. Supporting bases should be within flying range of the proposed landings, and should provide space for the construction of landing fields and sheltered water for the operation of sea planes. Shelter for surface craft and submarines is extremely desirable.

104. Securing a base. - In addition to the purely naval phases of the operation, the securing of a base for our fleet involves the control of all land areas from which the enemy can operate

| --1-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

effectively against the base with infantry or artillery. Ultimately, if the enemy air force cannot be denied by our aircraft and antiaircraft, it will be necessary to conduct additional landings for the purpose of neutralizing enemy air operations against the base.

105. Denying a base. - The denial of a base includes those measures necessary to prevent the enemy from using it. Insofar as landing operations are directly involved, this requires the securing of only such land areas as will enable our forces to operate effectively against the base with infantry, artillery, or aircraft. In this case the enemy force defending the base is an objective of the attacker only to the extent that it interferes with the attacker in occupying such areas and operating therefrom.

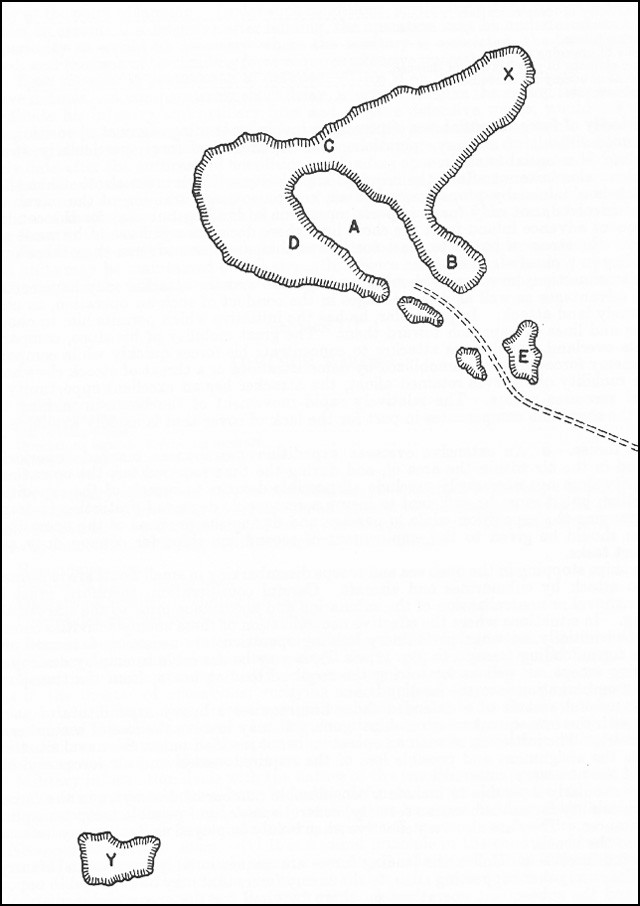

106. Illustrative diagram - securing and denying a base. -

a. The difference between securing and denying a base may be considered under two general situations (see fig. 1):

First situation: A BLUE expeditionary force has the task of securing a base for use of the BLUE fleet at A on an island occupied by RED. This task requires BLUE, in the first place, to drive RED from all such areas as B, C, D, E from which RED can operate against the base or its approaches with infantry or artillery and, eventually, from such areas as X or Y from which he can operate effectively against the base with aircraft. At least BLUE must successfully neutralize enemy weapons and aircraft operating against the base from such areas.

Second situation: BLUE has the task of denying the base A to RED. In this case BLUE would have to secure and hold only one area, such as B or E, from which he could operate effectively against the base or approaches thereto with infantry or artillery, or X or Y from which he could operate effectively against the base with aircraft.

b. In planning a landing operation in an area occupied by an enemy force it should be remembered that the task of the enemy will materially affect the probable strength and disposition of his forces. If his task is to deny the base, his force may be relatively weak and largely concentrated in, or prepared to move into, an area which is easy to defend. If his task is to secure the base for his own use, his forces will probably be of greater strength and more widely dispersed.

107. Landing raids. - Landing raids are generally made for the purpose of destroying enemy facilities and establishments, such as batteries, bridges, docks, supplies, aircraft, etc., or for harassing defense forces, diverting attention from operations in other localities, and effecting division of enemy forces. Such operations depend largely for success upon rapidity of movement and surprise, and normally involve relatively small forces, a limited advance inland, and a quick withdrawal. They may be conducted in connection with other landings or as a separate operation.

108. Land in the tactical control of sea areas. -

a. The ability of naval forces to maintain themselves in a given area may be dependent, from a tactical as well as from a logistical point of view, upon the occupation or control of the land areas lying within or adjacent to the theater of operations. Under modern conditions, certain types of bases have been moved from the realm of logistics to the realm of tactics; that is, from the line of communications to the line of battle.

b. Due to the importance of aircraft in fleet engagements, the relatively small number and vulnerability of carriers, and the possibility of shore-based aircraft operating with and augmenting the strength of our own or the enemy fleet, territory which otherwise might have no strategical or tactical value assumes an important role as possible air bases.

c. To a lesser extent submarine bases may be considered in the same category as air bases.

d. When the successful prosecution of the naval campaign requires the fleet, or portions thereof, to operate in a theater within effective flying range of enemy territory, the preliminary naval operations may revolve around a contest for the available land within or adjacent to the area. The entrance into and the securing of the initial foothold in such a theater of operations is hazardous and involves landing operations of a difficult nature. Under such conditions, the naval operations during the preliminary phases may be in the nature of a naval reconnaissance involving landings made with the view of securing information and seizing unoccupied or lightly held territory which later may be occupied in force and, ultimately, used as a base for further operations. (See par. 119, Supporting Bases.)

109. Small wars. - The extended and skillful use of automatic weapons by unorganized and irregular forces, even though relatively weak, may result in heavy casualties during a landing at localities occupied by such forces, unless the landing is conducted in accordance with sound tactical principles. While the doctrines herein enunciated are intended primarily as a guide in major operations, they apply equally to small war situations, with due allowance made for the character of the forces engaged and the necessity of safeguarding life and property insofar as possible.

| --2-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

| --3-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

Section II

Forces to be Employed

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 110. | Superiority of force essential | 4 |

| 111. | Naval forces | 4 |

| 112. | Marine forces | 4 |

| 113. | Tasks of opposing forces | 5 |

| 114. | Time element in preparation of defense | 5 |

| 115. | Arrival of enemy reinforcements | 5 |

| 116. | Replacements | 5 |

110. Superiority of force essential. -

a. Operations involving landings against opposition are among the most difficult of military operations, and superiority of force, particularly at the point of landing, is essential to success.

b. Numbers alone cannot afford the required superiority. There must also be that effectiveness which is obtained by proper organization, equipment, and training of the naval and marine forces involved, not only for the special operation of landing but also for the conduct of the subsequent advance inland from the shore line where decisions will have to be made and executed under the stress of battle to meet conditions that are more adverse than those ordinarily prevailing in a purely land attack.

c. In this connection, however, it should be recognized that the attacker may have certain very definite advantages as well as disadvantages in the conduct of such an operation, as compared to a purely land attack. In particular, he has the initiative which permits him to choose his objectives and lines of approach toward them. The great mobility of his ships, compared to movements overland, enables the attacker to concentrate his forces quickly while comparatively large enemy forces may be immobilized by demonstrations or a threat of attack elsewhere. Through the mobility of reserves retained afloat, the attacker has an excellent opportunity to exploit initial successes ashore. The relatively rapid movement of the boats in making the approach to the shore line compensates in part for the lack of cover that is usually available on land.

a. An extensive overseas expedition presupposes marked superiority on the sea and in the air within the area of, and during the time required for, the operations. Such superiority does not necessarily preclude all possible damage to vessels of the expedition by enemy action, but it must be sufficient to insure a reasonable degree of protection to transports accompanying the expedition while in passage and during the progress of the operations. Consideration should be given to the employment of second-line ships for convoy duty and gunfire support tasks.

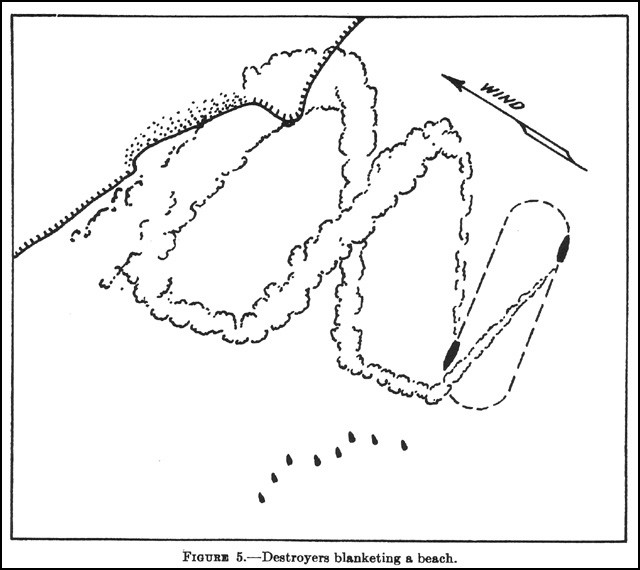

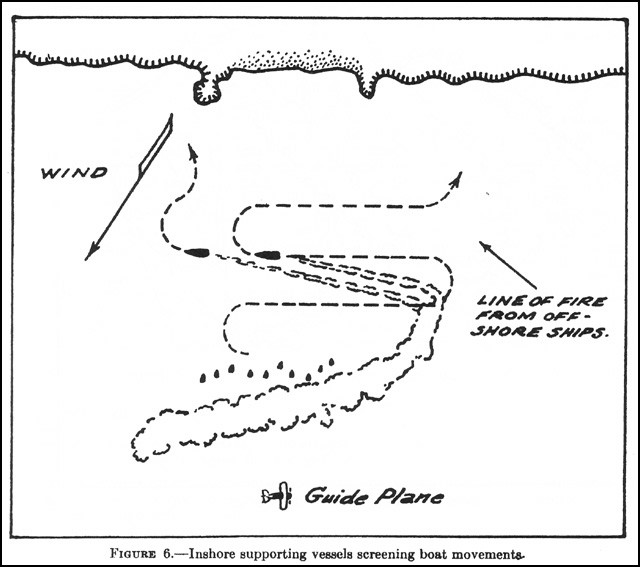

b. Large ships stopping in the open sea and troops disembarking in small boats are extremely vulnerable to attack by submarines and aircraft. Careful consideration, therefore, must be given to the removal or neutralization of the submarine and air menace prior to the start of the actual landing. In situations where the effective neutralization of these enemy activities cannot be accomplished initially, or when preliminary landing operations are necessary to secure protected waters for unloading transports (fig. 11, ch. I), it may be desirable to employ destroyers for transporting troops, as well as for towing the required landing boats, from the transports to the point of embarkation into the landing boats.

c. The successful assault of a defended shore line requires a heavy expenditure of naval ammunition, with the consequent wear on ships' guns. It may involve the loss of a number of ships and aircraft. The initiation of such an operation is not justified unless the naval situation fully warrants the assignment and possible loss of the required vessels and air forces and the expenditure of the necessary ammunition.

d. It is particularly desirable to include a considerable number of destroyers in the forces, due to their suitability for antisubmarine security, control vessels, and possible troop transports for limited distances. They are also very effective when boldly employed against enemy defenses located close to the beach.

a. Unless the landing forces are unquestionably superior in infantry, as well as artillery and other supporting arms, to the enemy forces that may be expected to oppose the landings and the subsequent operations on shore required for the accomplishment of the mission, the initiation of such an operation is not justified.

b. The operations ashore as well as the landing must be adequately supported by marine aircraft or, in their absence, by naval aircraft.

| --4-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

113. Tasks of opposing forces. - If, by reason of the task of the defender, the coast line or amount of territory to be defended is great in proportion to the strength of the defender, he will have to disperse his forces or leave certain portions of the coast undefended. The attacker may thus be able to concentrate, by reason of the superior mobility of his ships, an overwhelming superiority at the point of landing. Under such conditions, particularly if the task of the attacker permits him to assume the defensive after landing, the operation may be undertaken without as great superiority as would be necessary where the territory is restricted, the landing beaches are limited, and the task of the landing force requires offensive operations after landing.

114. Time element in preparations of defense. - Time is an important element in preparing an effective defense. A comparatively short delay, which would give the enemy time to organize and coordinate his infantry and artillery fires and prepare defensive works, would necessitate the employment of a much larger attacking force against the same defending force. It is important, therefore, that properly trained naval and marine forces be available and prepared to initiate at an early date after the outbreak of hostilities any landing operation that may be decided upon.

115. Arrival of enemy reinforcements. - The possibility of enemy reinforcements, particularly air forces, arriving during the course of the operation requires careful consideration in the estimate of the relative strength, and influences the selection of the time of arrival of the attacking force in the landing area.

116. Replacements. - Provisions should be made for adequate replacements, so that experienced units may be maintained at full strength. Since casualties in a landing operation are likely to be high in the initial phases, estimates of replacements to accompany the force should be liberal.

Section III

Advance Forces

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 117. | Preliminary operations | 5 |

| 118. | Reconnaissance | 5 |

| 119. | Supporting bases | 6 |

| 120. | Operations against defending aircraft | 7 |

| 121. | Operations against naval defense forces | 7 |

| 122. | Organization of advance forces | 7 |

Preliminary operations. - Prior to initiating an operation involving a landing against serious opposition, the desirability of organizing advance or reconnaissance forces for the conduct of certain preliminary operations should be given consideration. The following preliminary operations in connection with proposed landings may be desirable:

Reconnaissance.

Seizure of a supporting base.

Operations against defending aircraft.

Operations against naval defense forces.

a. Information to be obtained. -

1. Information regarding a theater of operations may be considered under two general heads, namely, Naval and Military.

2. Naval information is obtained for the purpose of determining the enemy naval dispositions in the theater of operations; verifying and supplementing existing hydrographic and meteorologic data; determining, from a navigational standpoint, the suitability of beaches and sea areas required for the conduct of a landing; locating mined areas, underwater obstacles, and other obstructions; selecting suitable approaches to landing areas; preparing sailing directions; and establishing necessary aids to navigation.

3. Military information deals with the nature of the terrain in the proposed zone of operations and the enemy disposition ashore, including defensive works, strong points, machine gun and artillery positions, location and intensity of defensive barrages, landing fields, gassed areas, location of reserves and their routes of advance, supply and ammunition facilities.

b. Necessity for reconnaissance. -

1. It is a sound principle in the conduct of landing operations to avoid landing against strongly organized positions unless such action is the only means of carrying out the assigned task within the time available. In general, such organized positions can be located only by adequate and thorough reconnaissance.

2. There is a notable lack of information on charts and in existing sailing directions in regard to landing conditions for small boats. There is a further possibility that the enemy will place underwater obstacles and other obstructions on or near available landing beaches and

| --5-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

approaches thereto. Information in regard to beaches, therefore, will have to be secured largely through active reconnaissance.

3. On an inadequately charted coast line, with ordinary navigational aids destroyed by the enemy, the safe navigation of the attacker's ships requires careful and detailed reconnaissance. Under some conditions, a limited hydrographic survey of the coast and the establishment of necessary aids to navigation may be required.

4. The necessity for conserving and making the best use of the limited supply of naval ammunition renders it desirable that beaches be reconnoitered before being shelled by ships' guns in order to determine whether or not they are being held by the enemy. It is also desirable to locate strong points in the enemy position, and to chart landmarks which will enable firing ships to identify their target areas.

5. Before landing relatively large bodies of troops, particularly on small islands or in other restricted areas, it is important to determine by reconnaissance if beaches have been, or are likely to be, gassed.

c. Means employed. -

1. To gain the desired information, surface craft, submarines, aerial observation and photography, and landing parties are employed.

2. Aerial photographs and direct observation from the air and sea will give fairly complete information in regard to certain types of fieldworks on shore but will give very little information as to whether or not they are occupied. Particularly dangerous emplacements, such as machine-gun positions, may be so well camouflaged as to be completely invisible. As a rule, the number and location of defensive weapons can only be determined, and then with difficulty, by causing them to open fire, which normally they will do only when a landing seems imminent. Against an alert enemy, therefore, the attacker will have to depend upon landing parties or demonstrations to gain information regarding the enemy's strength and dispositions on shore. The landing parties may consist of agents, patrols, or reconnaissance in force. (See ch. IV, sec. VI, Reconnaissance Patrols.)

d. The intelligence plan. - After making a study of existing data on the proposed theater of operations, an intelligence plan should be prepared in which is listed the additional information, naval and military, required for the conduct of the operation. This intelligence plan forms the basis for determining the size, composition, and tasks of the reconnaissance force dispatched to the theater of operations for the purpose of collecting the necessary information.

e. The principle of surprise. - In the execution of the intelligence plan for a specific landing operation, care must be taken not to divulge the intentions of the attacker, and certain landing areas and beaches, which are not to be used, should be reconnoitered as thoroughly and with the same means as those at which landings are planned.

f. Detailed reconnaissance of a landing area. - In connection with the detailed reconnaissance of a particular landing area, see paragraphs 209 and 210.

119. Supporting bases. -

a. In many theaters of operations, it will be extremely difficult for the defender to occupy all of the available land areas in force. Certain areas will be strongly fortified and others will be more lightly held or even unoccupied. If it is necessary to seize a fortified position in such an area, it will generally be advisable, if not mandatory, to operate step by step, seizing first the weakly defended areas for use as supporting bases in the subsequent landings against the fortified positions.

b. If suitable areas are available for the purpose, the establishment of one or more supporting bases may furnish the following advantages in the execution of the main attack:

Permits naval aircraft to operate from landing fields and reduces the risk incident to carrier operations.

Permits the employment of seaplanes.

Permits employment of the aviation of the landing force.

Denies landing fields and other facilities to the enemy.

Affords shelter for vessels before and during the course of the subsequent operations.

Affords a rendezvous and a point of departure for subsequent landings.

Facilitates the storage and distribution of supplies.

c. A supporting base will usually be within bombing range of an enemy base or possible base. Under such conditions, the seizure and occupation of the supporting base, and the installation of the necessary landing fields and facilities, is a delicate problem and the operation may require a considerable period of time. The initial operation may be a landing in force, or a foothold may be secured by advance or reconnaissance forces. In the latter case, the garrison and base facilities may be gradually built up by the subsequent landing of troops and matériel

| --6-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

in relatively small increments. It will be safer to fly planes in from carriers after adequate landing fields and air and antiaircraft protection have been provided, rather than to attempt landing crated planes and setting them up under hostile bombing attacks. The enemy may be expected to bring the full strength of his air units against the establishment of a supporting air base.

120. Operations against defending aircraft. -

a. Operations against enemy aircraft, preliminary to a landing, may include aerial combat, bombing and strafing planes on the ground, and gassing, bombing, and shelling landing fields and their installations.

b. The enemy will, if possible, utilize a large number of landing fields; camouflage will be employed to the fullest extent to protect his establishments; dummy planes will be displayed; real planes will be widely separated and camouflaged. Such protective measures on the part of the enemy require careful reconnaissance before successful attacks can be launched. The restriction of hostile air activities by rendering a considerable portion of his landing fields unusable through bombing attacks will require extensive operations and a heavy if not prohibitive expenditure of bombs. Therefore, such bombing operations should be limited to landing fields definitely known to be occupied.

c. Carrier-based planes are at a distinct disadvantage in conducting this type of operation compared to land-based planes. For this reason, if a supporting base is not available to the attacker, it may be advisable to restrict preliminary air operations of carrier-based planes to necessary reconnaissance, in order to insure superiority at the critical time of landing.

121. Operations against naval defense forces. -

a. The naval defense forces of a base, having the mission of furnishing information of the attacker's movements and inflicting damage to his ships and small boats transporting troops to the beach, must be cleared from the sea areas required for the conduct of the operation, or effectively neutralized during the course of the landing.

b. In addition to screening and patrolling the station and maneuver areas of the attacking force during the landing, advance forces may be given the task of operating against the naval defense force prior to the landing with the view of clearing the required area of surface patrol craft and reducing the number and effectiveness of enemy submarines.

c. At night, patrol vessels constitute one of the defender's principal means of securing information as to the movements of the attacker's ships. To secure this information, they have to approach closely and attempt to identify every vessel maneuvering on the coast. For this reason, destroyers of the attacker operating at night against naval defense forces have an excellent opportunity of making contacts with enemy vessels and locating their patrol areas. Operations in such areas for several nights prior to the landing should result in material losses to the naval defense force and reduction in its effectiveness by compelling the enemy vessels to adopt a less aggressive attitude.

122. Organization of advance forces. -

a. The composition of advance forces will depend upon the tasks assigned and the probable enemy forces in the theater of operations. Advance forces should be dispatched at such time as will permit the main operation to be executed without unnecessary delay.

b. Specially trained marine personnel and suitable boats for reconnaissance tasks should accompany the force for the conduct of necessary shore reconnaissances. When the advance force is given the task of securing a supporting base, a suitable landing force should be made a part of the advance force, or available to it, for use when the occasion arises.

Section IV

Main and Subsidiary Landings

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 123. | Types of operations | 7 |

| 124. | The main landing | 8 |

| 125. | Secondary landings | 8 |

| 126. | Demonstrations | 8 |

| 127. | Surprise landings | 9 |

123. Types of operations. - The seizure of an area defended by hostile forces may involve the following coordinated operations:

The main landing;

One or more secondary landings; and

One or more demonstrations or feints.

| --7-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

124. The main landing. - The main landing is that upon which the ultimate success of the tactical plan depends. In the assignment of troops, ships, and aircraft, it has first consideration and must be provided with the forces necessary for success. The detachment of any forces from the main landing for the conduct of a subsidiary operation is only justified when the results to be reasonably expected from the latter are greater than if these forces were used in the main landing. In some situations, consideration should be given to making two or more landings in force, with the view to exploiting the landing which is most successful.

125. Secondary landings. -

a. Secondary landings are those made outside the immediate area of the main landing which directly or indirectly support the main landing. They may be made prior to, simultaneously with, or subsequent to, the main landing.

b. Secondary landings are usually made for the purpose of seizing and holding areas which are desirable for operations in connection with the main landing, or which may be used by the enemy in opposing the main landing. Secondary landings may also be made for the purpose of diverting enemy reserves, artillery fire, or aircraft support from the area of the main landing. Such landings may also cause delay in starting the movement of the general reserves, or local defense forces from other sectors, to oppose the main landing.

c. The early entry into action of land-based artillery and aircraft may be necessary in order to provide adequate support for the main landing or the operations on shore. Where suitable areas for landing fields or artillery positions exist outside of the area of the main landing, consideration should be given to the early seizure of such areas by secondary landings.

d. Secondary landings made for the purpose of causing the movement of hostile reserves from the main landing area require, as a rule, a greater proportional force than those seeking to hold enemy forces in place or retard their movement. In the former case, sufficient force must be employed to overcome the local defense forces and gain a success which threatens a point important to the defender; otherwise, he probably will not move his reserves.

e. The term "secondary landings" should not be used in plans and orders, as these landings constitute an important part of the operation as a whole. The forces assigned these tasks must carry them out with the same determination that characterizes the main landing.

f. In some situations, the development of the subsequent operations may make it advisable to exploit a secondary landing rather than the main landing, consequently this should be considered when selecting areas for secondary landings.

126. Demonstrations. -

a. A demonstration, or feint, is an exhibition of force, or movement, indicating an attack. Demonstrations are made for the purpose of diverting enemy reserves, artillery fire, surface craft, submarines, or aircraft support from the area of the main landing, or the retarding of the movement of enemy forces thereto.

b. In order further to deceive the enemy as to the location of the main landing, demonstrations may be conducted and coordinated with secondary landings. A demonstration alone, however, may often be more effective than a weak secondary landing, particularly in delaying the movement of enemy forces toward the area of the main effort. The effectiveness of a weak landing is largely lost as soon as its weakness is discovered, while a show of force constitutes a continuing threat and may hold in place comparatively large enemy forces for considerable periods of time. In order to produce the greatest effect, the mobility of ships should be utilized in such operations to threaten a number of points and thus immobilize enemy forces over a large area.

c. Demonstrations have no territorial objective but they should threaten areas of importance to the enemy. They should be coordinated as to time, and directed at points so distant from the main landing that they will contain the enemy forces stationed at or drawn to such points, and prevent them from opposing the main landing. This coordination as to time and distance is particularly important where it is desired to prevent the participation of the enemy aircraft, surface vessels, and submarines in the operations involved in the main landing.

d. Demonstrations conducted in conjunction with and in the vicinity of an actual landing are effective in causing a dispersion of enemy artillery fire. Shore batteries generally have a "normal zone" covering one or more beaches and a "contingent zone" covering other beaches or areas. The defensive artillery plan will generally provide for a concentration of all batteries within range of a designated point. A few boats approaching a beach, particularly when accompanied by smoke and some gunfire, should make all enemy batteries, within whose normal zone the beach lies, open fire on that particular beach or boats, rather than joining in a general concentration on the actual landing. Such demonstrations are particularly desirable when the main landing is conducted on a comparatively narrow front.

e. Demonstrations may be conducted in connection with reconnaissance prior to a landing in order to cause the consumption of the enemy ammunition and chemical supplies, the disclosure

| --8-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

of his strength and dispositions, artillery positions, barrages, gassed areas, and landing fields, and further the wearing down of his air forces.

f. From the foregoing, it may be seen that demonstrations or feints may be made to contribute greatly toward the gaining of tactical surprise.

127. Surprise landings. - Rubber landing craft, track landing vehicles, and other special types of boats, as well as parachute troops, and troops transported during the night from a distant base by patrol planes or large commercial clipper planes, should be utilized to the fullest extent to execute surprise landings at points where, due to the nature of the beaches or terrain, landings would not ordinarily be expected. These landings may be in connection with or part of the main or secondary landings and should be made in accordance with the same principles and for the same purposes as previously set forth in this section.

Section V

Beachheads

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 128. | The beachhead | 9 |

| 129. | The force beachhead line | 9 |

| 130. | The exploitation line | 9 |

| 131. | Extent and form of the beachhead | 9 |

| 132. | Successive objectives | 10 |

| 133. | The artillery control line | 10 |

| 134. | Intermediate beachhead lines | 10 |

| 135. | Establishing the beachhead | 10 |

| 136. | Advance from the beachhead | 10 |

128. The beachhead. -

a. The first consideration in the conduct of operations on shore after the landing has been effected is the seizure of a beachhead of sufficient extent to insure the continuous landing of troops and matériel, and to provide the terrain features and maneuver space requisite for the projected operations on shore.

b. The establishment of a beachhead enables a commander to maintain control of his forces until the situation ashore has developed and he has sufficient information on which to base his plans and orders for further operations.

c. As a matter of security, it will be necessary to clear the beachhead of enemy resistance. It should be kept in mind, however, that the establishment of a beachhead is not a purely defensive measure. It has the equally important object of insuring further advance inland if required to accomplish the mission of the force. Consideration should be given, therefore, to the early seizure of terrain features which will facilitate this advance by including them in the beachhead or making them the objective of a special operation. Consideration should also be given to depriving the enemy of terrain features which are most advantageous in the defense.

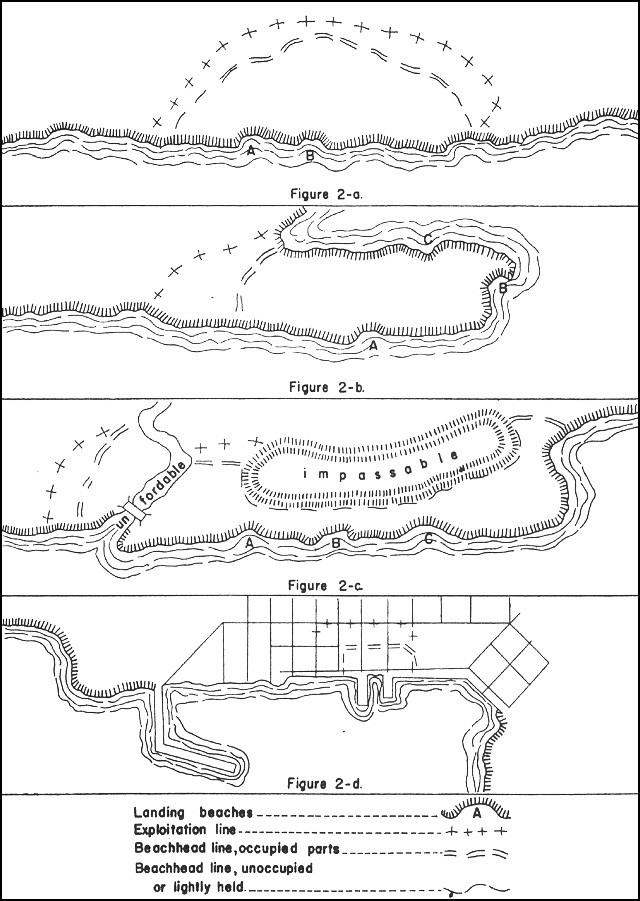

129. The force beachhead line. - This is an objective prescribed for the purpose of fixing the limits of the beachhead. It is not necessarily a defensive position to be occupied and organized as such. It is, however, a tentative main line of resistance in case of counterattack prior to the advance from the beachhead, and it is occupied and organized to the extent demanded by the situation. (See fig. 2.)

130. The exploitation line. -

a. This is a line beyond the beachhead line to which reconnaissance and security detachments will be pushed by units occupying the beachhead line. It provides a zone in which active reconnoitering will be conducted on the initiative of such unit commanders and, at the same time, prevents a greater dispersion of the force as a whole than is desired by the force commander. (See fig. 2.)

b. Reconnaissances beyond the exploitation line will partake of the nature of reconnaissances in force launched by specific orders against designated points or in designated directions.

c. In the event of the occupation of the beachhead line as a defensive position, the exploitation line constitutes the limit of the outpost positions.

131. Extent and form of the beachhead. -

a. The beachhead should be of sufficient depth and frontage to secure the landing from ground-observed artillery fire. Usually this will be possible only with comparatively large forces. A landing force manifestly cannot overextend its units or subject its flanks, beach establishments, and land communications to attack until the enemy situation has been developed. The depth and frontage of the beachhead will be dependent, therefore, upon the mission, the size of the force engaged, the nature of the terrain particularly as regards natural obstacles, and the probable enemy reaction.

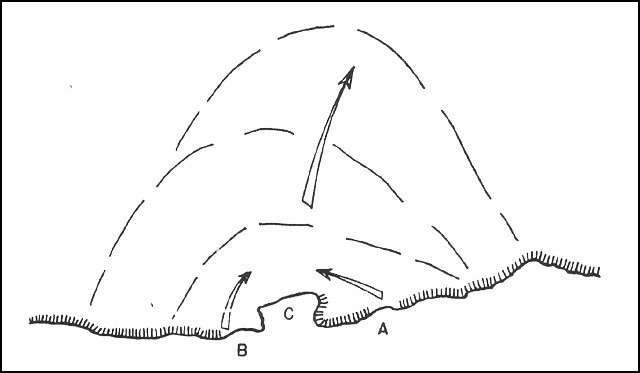

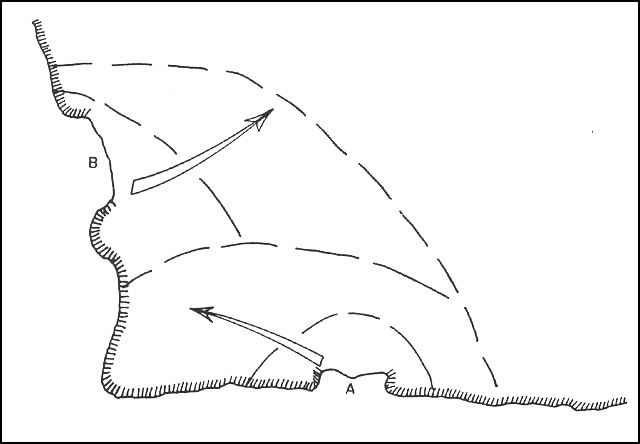

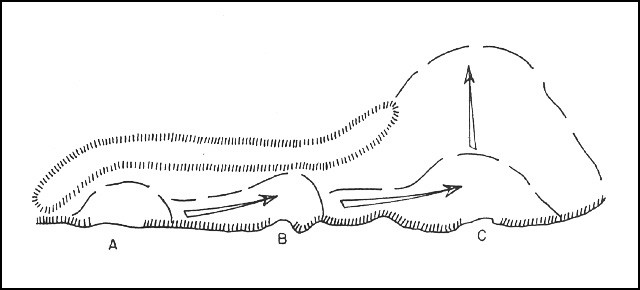

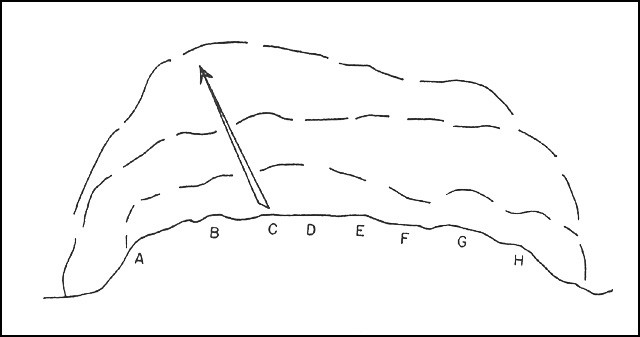

Figure 2 shows diagrammatically how terrain features may modify the form of the beachhead, and the extent to which the beachhead line may have to be occupied under various

| --9-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

conditions in order to insure the desired security of the shore establishments. In figure 2-a, the terrain is assumed to be suitable for maneuver throughout its whole extent. In figures 2-b and 2-c, the effect is shown of certain impassable obstacles, which may be encountered in a variety of forms and combinations. Figure 2-d shows a beachhead where it is necessary to land in a town. This latter situation might arise in the seizure of a town as part of a major operation or in connection with a small war where a beachhead, in addition to its normal functions, would afford an immediate security zone for civilians. In most situations of this kind it would be advisable to land outside the town even though only very weak resistance is anticipated.

132. Successive objectives. - Successive objectives may be designated to coordinate the advance from the beach to the beachhead line. Such objectives have the advantages of permitting reorganization of attacking troops, passage of lines, coordination of field artillery and ships' gunfire with the advance, and facilitating the execution of an appreciable change in direction of the attack. Objectives entail a certain delay and should not be prescribed unless actually needed for a definite purpose.

133. The artillery control line. -

a. This is a line short of which the field artillery does not fire except on request of infantry commanders, and beyond which the advance is supported by the bulk of the field artillery. Its introduction is often desirable in order to permit artillery to open fire immediately upon landing without danger to friendly troops.

b. The position of the artillery control line is fixed after consideration of the probable position of the infantry at the time the artillery is ashore and in position to open fire. If suitable terrain features exist, the artillery control line should be located a safe distance beyond an infantry objective, which can easily be defined and readily identified on the ground by both infantry and artillery. If no such natural features exist, the artillery control line should be located at such distance from the beach that the advanced infantry elements will not, in all probability, have reached the target area at the time it is estimated that the artillery will open fire.

c. Main reliance must be placed in ships' gunfire for support of the attack up to the artillery control line, as field artillery will not be in position to fire short of this line unless the attack is stopped or materially slowed down before the artillery control line is reached.

134. Intermediate beachhead lines. -

a. Subordinate commanders may find it desirable, particularly where beaches are not contiguous, to designate intermediate beachhead lines in addition to the successive objectives prescribed by higher authority, with the view of protecting the beaches from aimed small-arms fire. The depth of such intermediate beachheads will be largely dependent upon the formation of the terrain adjacent to the beach. If there is a bluff or ridge close to the shore line, a comparatively shallow intermediate beachhead may suffice; if the terrain inland from the beach is an open, fairly uniform slope, an intermediate beachhead of from 1,000 to 1,500 yards may be necessary to accomplish the desired purpose.

b. When intermediate beachheads are prescribed, they are designated "Battalion beachhead," "Regimental beachhead," etc., according to the organization for which prescribed.

135. Establishing the beachhead. -

a. In a landing operation, troops must clear the beach rapidly; there must be no delay at the water's edge. This requires, in the first place, that leading units be landed in assault formation as fully deployed as the available boats permit. Once landed, every individual must thoroughly understand that he must first clear the beach and then move rapidly inland or in the designated direction.

b. Assault units push the attack to their designated objectives without waiting for the advance of units on their flanks. Reserves are utilized to cover the flanks of advanced units rather than holding up the attack for a uniform advance on the whole front. If a unit is landed on the wrong beach, its commander will initiate such action as will best further the general scheme of maneuver.

136. Advance from the beachhead. -

a. The desirability of establishing a security zone around his shore base should not lead a commander to adopt a passive attitude. Unless the mission is accomplished by the securing and holding of the beachhead, active, aggressive action provides the surest means of carrying out the mission and will often afford the best protection to the beach establishments.

b. The advance from the beachhead line, however, may entail the breaking of one or both flanks from physical contact with the shore, the establishment of shore lines of communication, and entering into a phase of war of maneuver. Under such conditions, the securing of a beachhead may be followed by a period of stabilization during which the necessary regrouping of forces may be effected and information of the hostile dispositions secured. Reconnaissances by air forces and ground troops should be pushed vigorously so that the delay on the beachhead line may be reduced to the absolute minimum.

| --10-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

| --11-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

Section VI

Selection of Landing Areas

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 137. | The landing area | 12 |

| 138. | Mission | 12 |

| 139. | Enemy dispositions | 12 |

| 140. | Beaches | 12 |

| 141. | Suitability of terrain for shore operations | 13 |

| 142. | Station and maneuver areas for naval forces | 13 |

| 143. | Configuration of the coast line | 14 |

| 144. | Time element | 14 |

| 145. | Weather conditions | 14 |

| 146. | Final selection of landing area | 14 |

137. The landing area. - The landing area comprises the sea and land areas required for executing the landing and establishing the beachhead. Its selection is governed by the following principal factors:

Mission.

Enemy dispositions.

Number and types of beaches and approaches thereto.

Suitability of terrain for shore operations (including the establishment of the beachhead and contemplated advance therefrom).

Station and maneuver areas for naval vessels.

Configuration of the coast line.

Time element.

Weather conditions.

138. Mission. - The area selected must be such as to assure the landing of sufficient troops (after making due allowances for losses before and after landing) at a place from which they can reach their objective and accomplish the mission for which the landing was undertaken.

139. Enemy dispositions. -

a. A landing area in which the defender has been able to occupy and strongly organize the available beaches should be avoided if it is possible to carry out the mission by landing at beaches undefended or less strongly held.

b. Where the defender is organized in depth, with natural obstacles and other means of defense, the successful conduct of a landing operation will require an enormous expenditure of ammunition, far beyond that ordinarily supplied to combat vessels. Such an operation should never be undertaken unless sufficient ships, planes, and ammunition are available effectively to neutralize the enemy weapons.

c. The probable location of enemy general or local reserves, and the facility and speed with which these reserves can be thrown into action to oppose the landing or the advance inland, are important elements in the selection of a landing area. Consideration should be given, therefore, to the routes and means of communications available for these reserves to the various landing areas, the possibility of the attacker interfering with their movement by air attack and interdiction fires, and the presence of terrain features, such as defiles and natural obstacles, favorable to employment of these reserves in opposing the advance.

140. Beaches. -

a. A beach is that portion of the shore line normally required for the landing of a force approximating one infantry assault battalion. It may be, however, a portion of the shore line constituting a tactical locality, such as a bay, to which may be assigned a force larger or smaller than a battalion.

b. Favorable beaches, from a physical standpoint, are those which permit the beaching of small boats close to the shore line and the rapid disembarking and movement inland of troops and equipment without undue interference from weather conditions or navigational difficulties.

c. Open beaches on the weather side where surf is breaking, or is likely to break during the course of the operation, are especially unfavorable, particularly where there are rocks or coral, unless landing boats especially designed to cross these obstacles are available. The landing of a large force with its impedimenta may extend over several days, and this, together with the necessity of maintaining lines of supply, requires that certain beaches provide suitable conditions for continuous landings throughout the operation.

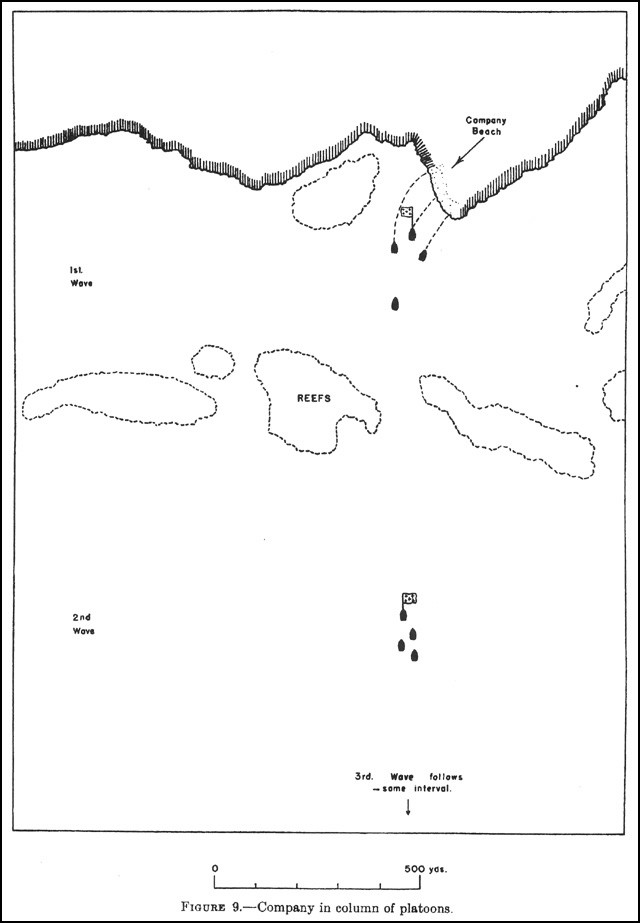

d. Gently shelving beaches, or those having offshore reefs, causing small boats to ground at a considerable distance from the shore line, are unfavorable, as the time of disembarking and deploying is lengthened, with consequent increase in the effect of hostile fire. The use of shallow draft lifeboats or rubber boats will be found advantageous when, because of tactical considerations or hydrographic conditions elsewhere, a landing on this type of beach is desired.

| --12-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

e. Approaches to the beach should be free, under all conditions of tide, from natural or artificial obstructions to navigation, and it is particularly desirable that there be sufficient room to seaward to permit the boats to deploy into their attack formations before coming under effective artillery or small-arms fire. Narrow entrances between islands and channels in reefs prevent this early deployment and greatly increase the effectiveness of the defender's fire.

f. Some of the beaches must provide suitable landing conditions and routes inland for wheeled vehicles and tractors. Such beaches may be captured initially or in subsequent operations. Other beaches may be suitable for landing infantry and pack artillery only. In this connection, it should be recognized that determined foot troops can negotiate precipitous slopes and that such slopes will often offer dead spaces from enemy fires. Landing conditions at the foot of rocky cliffs, however, are often bad and landings may be possible only in calm seas.

g. The area around a beach in which the defender can place weapons for direct aimed fire on the beach will be limited by the configuration of the ground. When such areas have a depth of several hundred yards, the immediate landing is more difficult because of the large zone which has to be neutralized. Shallow areas are advantageous in reducing the size of this zone and permitting the attacker to deprive the defender of observation on the beach after a relatively short advance. Woods which the defender has not had time to clear, or a bluff close to the beach, have certain definite advantages in executing the actual landing, provided the advance of necessary combat equipment is not seriously impeded. Such features may, however, render more difficult the support by naval gunfire of the subsequent advance inland.

h. The number of beaches required for an operation is dependent upon the size of the attacking force, the scheme of maneuver, and the amount of resistance expected. A landing area with a large number of suitable beaches is particularly desirable, even for a comparatively small force, as it causes a dispersion of the defender's efforts and permits the attacker to land on as broad a front as is commensurate with his strength. Such an area also favors tactical surprise, as it offers the attacker a choice in the selection of beaches, and the defender is unable to determine the exact point of landing until the boats have approached close to the shore.

i. The shore line need not be suitable for landing throughout its entire extent, provided the various beaches permit the units landing thereon to be mutually supporting and a portion of the beaches permit the timely landing of the required equipment.

j. Beaches not otherwise suitable may be utilized for landing troops in rubber boats, amphibian tractors, or other special type boats. Such special equipment should be utilized to the fullest extent practicable for the execution of surprise landings, and to assist main landings by pressure at points which, because of the nature of the coast line, are lightly held by the enemy.

141. Suitability of terrain for shore operations. -

a. The influence of the terrain on the shore operations is the same as in ordinary land warfare. The proposed zone of advance should be critically examined as to its suitability for the contemplated operations, paying particular attention to the road net, natural obstacles or defiles which have to be forced, observation for both defender and attacker, maneuver room for the force engaged, and landing fields which permit the early entry into action of our land-based aircraft.

b. In connection with the location of the landing area in relation to the final objective of the shore operations, consideration should be given to the advantages inherent in a movement along the coast line. The sea affords protection to at least one flank, and such a movement greatly facilitates the supply problem in that the shore base may be shifted as the action progresses, resulting in shorter and more easily protected lines of supply. This type of operation also compels the defender to fight on lines perpendicular to the beach and permits reinforcement of field artillery by ships' guns firing under the most advantageous conditions. Too much reliance, however, should not be placed on this support except in areas adjacent to the beach and visible from seaward.

142. Station and maneuver areas for naval forces. -

a. The naval forces should have station and maneuver areas free from mines and obstructions, and with suitable approaches thereto, in which troops may be safely disembarked and from which the type of fire demanded by the situation may be delivered. The areas must be conveniently located with respect to the available beaches.

b. Water deep enough for maneuvering vessels close inshore is desirable, as it enables ships accompanying the boats to stand well in and deliver their fire at short range. This permits the most effective support during the approach of the small boats and the initial landing.

c. Flanking fire in support of a landing is generally more effective than that delivered from the front, as it tends to enfilade the defender's position and permits small boats carrying troops

| --13-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

to approach closer to the area being shelled. Sea areas from which this type of fire can be delivered are, therefore, extremely desirable.

d. A sheltered transport area will materially decrease the time required for unloading troops and equipment and will lessen the danger of the operation being interrupted by bad weather.

e. Water with a depth and bottom suitable for anchoring marking ships or buoys is a desirable feature. It may be advantageous in some cases to anchor transports or even firing ships. Water of less than 10 fathoms furnishes considerable protection against large submarines, provided the shallow depth extends far enough to keep enemy submarines outside of maximum torpedo range. This depth of water, however, does not furnish complete protection from small submarines, and is favorable for enemy mining operations.

f. If a convenient supporting base is not available for anchorage and protection of the naval forces during the period elapsing between the initial landing and the securing of a suitable new base, it is highly desirable that the landing and operations ashore be planned with a view to securing a sheltered anchorage as quickly as possible.

143. Configuration of the coast line. -

a. Favorable landing conditions are usually found in harbors, bays, and indentations in the coast line. Such formations, however, favor the concentration of enemy artillery fire in the entrances and, furthermore, permit the defender to bring flanking fire upon the boats from automatic weapons and antiboat guns from the shores flanking the entrance. Enemy weapons so located must be neutralized by either naval gunfire or the leading element of the landing force before the boats making the main landing come within effective range of such flanking fire.

b. Land projections are favorable to the attacker in that they facilitate the delivery of flanking fire by ships' guns and permit the attacking units to protect both flanks by resting them on the water's edge. At the same time, the base of a peninsula may afford the enemy a strong defensive position which will block progress inland. The seizure of such projections as a supporting measure for other operations may be advisable.

c. A chain of small islands offers certain advantages as a landing area. The delivery of naval gunfire, particularly counterbattery, is facilitated, and the operation may be conducted step by step, each island as it is seized becoming a base for further operations. The islands may be mutually supporting by small-arms or artillery fire, but the employment of general reserves by the defender for opposing the landings on the various islands may be difficult or entirely impossible.

144. Time element. - Certainty of getting ashore is of first consideration, but a successful landing avails nothing if the landing force, by reason of distance or difficulties of the terrain, is unable to reach its objective in time to carry out its mission. The time element, therefore, is important in the selection of the landing area. If time is limited it may be necessary to land close to the objective regardless of enemy dispositions. With more time available, the landing may be made in an area where the beaches are less heavily defended, but requiring more extensive shore operations for the carrying out of the mission.

145. Weather conditions. - Careful study must be made of the weather conditions in the contemplated theater of operations. Operations that may be feasible at one season of the year may be impracticable at another due to weather conditions, such as prevalent high winds which may render landings impossible, the likelihood of storms interrupting ship to shore communications, or rains rendering land operations difficult. Surf and reefs may be negotiable at only one stage of the tide and conditions may vary within the same general area.

146. Final selection of landing area. -

a. Landing areas having the best beaches and the most favorable approaches inland will probably be those most heavily defended by the enemy. Conversely, landing areas with unfavorable beaches and easily defended avenues of approach inland will be less heavily defended.

b. The final selection of the landing area will generally be a question of deciding between these conflicting conditions. A correct decision demands a careful estimate of the situation, involving not only a study of the physical features of the beaches but a thorough knowledge of the capabilities and limitations of the opposing forces and a careful computation of time and space.

c. As a rule sufficient information on which to base a decision will not be available until after a thorough reconnaissance has been completed.

| --14-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

Section VII

Scheme of Maneuver

| Par. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 147. | Frontage of attack | 15 |

| 148. | Boats | 16 |

| 149. | Hostile dispositions | 16 |

| 150. | Types of landings | 16 |

| 151. | Illustrative diagrams--Scheme of maneuver | 16 |

147. Frontage of attack. -

a. An important consideration in formulating a scheme of maneuver is the frontage to be covered by the landings and the subsequent advance inland. Necessarily, the frontage of the landing is dependent, to a large extent, upon the number, type, and relative position of the beaches available in the landing area. An almost equally important consideration, however, is the strength and equipment of the attacking force. During the initial stages of the landing, ships' guns constitute the artillery of the attacking force. This force must be considered therefore, as comprising two elements of major importance, namely -

The landing force.

Naval gunfire.

b. The landing force. -

1. It is desirable to attack on a wide front in order to increase the speed of landing and to cause a dispersion of the defender's efforts, but the attacking force must not itself overextend. It must observe the principle of concentration of effort and assign sufficient forces to the various tasks to insure their success.

2. Units comprising initial assault echelons are particularly apt to become disorganized during and immediately after the landing, and they cannot be expected to make deep penetrations against strong opposition. It is often desirable, therefore, to have leading assault units secure a limited objective or intermediate beachhead and cover the landing of fresh troops with which to carry on the attack.

3. In many cases landings will not be made on the entire front of the beachhead. This will result in the zone of attack increasing in width as the advance inland progresses. The scheme of maneuver, therefore, must provide for the introduction of additional units in the assault from time to time in order to take care of this increased front.

4. Sufficient reserves must be kept in hand to insure the exploitation of successes and to continue the attack to the final objective. But an operation which apparently requires all of the attacker's forces for securing the initial foothold on the beach is rarely justified.

5. The foregoing factors require organization in depth, and units should be assigned frontages which permit a depth of formation commensurate with the effort expected of them; that is, according to the depth of advance, the nature of the hostile opposition, and the assistance to be expected from or given to neighboring units. Consideration must be given not only to the frontage of the landing but to the frontage to be eventually covered by the unit.

6. For frontages applicable to various subordinate units, see chapter IV, section III.

c. Naval gunfire. -

1. Probably the most difficult decision in formulating the scheme of maneuver is that pertaining to the frontage which can be effectively covered by the fire of the available ships, and it is here that the judgment and responsibility of the commander is put to the severest test. In deciding this question, consideration must be given to: First, the devastating effect of the fire of relatively few machine guns when firing under advantageous conditions; second, that an attack against such weapons has little chance of success unless adequately supported by artillery; third, that a landing operation cannot be stopped and resumed at will, and, as a rule, only one chance for success is offered.

2. In order to provide this essential artillery support, the scheme of maneuver must observe the principle of concentration of effort for the naval gunfire as well as for the landing force, by limiting the landings to frontages commensurate with the amount of supporting gunfire available. Where the number of ships is relatively small, two alternate maneuvers are offered for accomplishing the desired results, namely -

Landing at few beaches.

Landing at several beaches in echelon, so that all available ships can concentrate successively on each beach.

| --15-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

148. Boats. -

a. The speed with which troops can be put ashore is directly dependent upon the number and type of boats available and the distance of the transports from the various beaches. The scheme of maneuver, therefore, must take these factors into consideration, particularly where there are not enough boats to embark all of the landing force at one time. The timely support of assault echelons and the prompt exploitation of success require reserves in boats immediately available. This limits the number of boats, and consequently the troops and frontages, which can be assigned the initial assault echelons.

b. The frontage of the initial attack will also be limited by the availability of small, fast boats suitable for assault troops. Such boats should be provided for the leading platoons of battalions which are to be landed in assault. (For detailed discussion of landing boats, see Ch. III.)

149. Hostile dispositions. -

a. Beaches strongly organized for defense should be avoided, if possible, in the initial landings. Advantage should be taken of undefended or lightly defended portions of the shore line, even though presenting less favorable landing conditions, in order to outmaneuver the hostile resistance or to gain a position from which flanking artillery or small-arms fire may be brought to assist the landing at more favorable beaches.

b. This type of maneuver may necessitate awaiting favorable weather conditions in order to effect landings at the desired beaches. It should be recognized that such plans embody additional hazards due to probable delays in execution, and the consequent increased danger of interruption of operations by bad weather or submarine attack.

150. Types of landings. -

a. A simultaneous landing may be made on all selected landing beaches, or the landing may be made by echelon.

b. In attacking by echelon, it is generally desirable to land last at the beach, or beaches, where it is planned to make the main effort. This enables the ships which support that landing to continue, without interruption, in support of the advance of the main effort. Plans must be flexible, however, and constant consideration should be given to the advisability of exploiting a landing already successfully executed rather than attempting a new landing against opposition.

c. The time interval between landings, in an attack by echelon, may vary between wide limits. Where there are sufficient boats to carry all of the landing force in one trip and the supporting ships can cover the various landings from the same general locality, this interval may be only a few minutes. The amount of ships' gunfire to be placed on the various beaches, together with the scheme of maneuver on shore, will determine this time interval. Where two or more boat trips and considerable movement of the supporting ships are required, or where it is desired to cause a movement of hostile reserves toward the first landing, several hours may elapse between landings. The danger of being defeated in detail must be guarded against.

d. Landings by echelon should be attempted only when the beaches, or groups of beaches, are separated by such distances that troops landed on one beach will not be endangered by naval gunfire on another beach.

e. A landing by echelon, as in a landing on a single beach, facilitates the concentration of the hostile artillery fires. In connection with such landings, demonstrations should be made to cause a dispersion of the hostile fire. In addition heavy counterbattery fire should be employed to neutralize the enemy batteries.

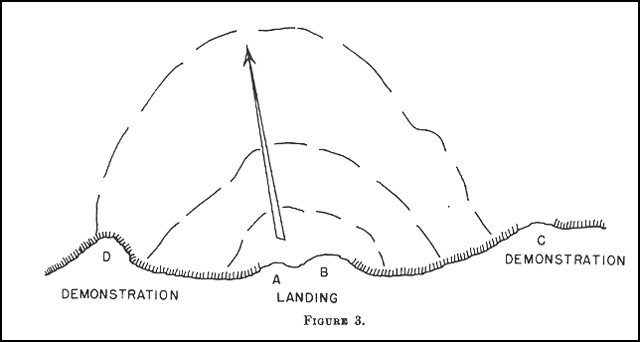

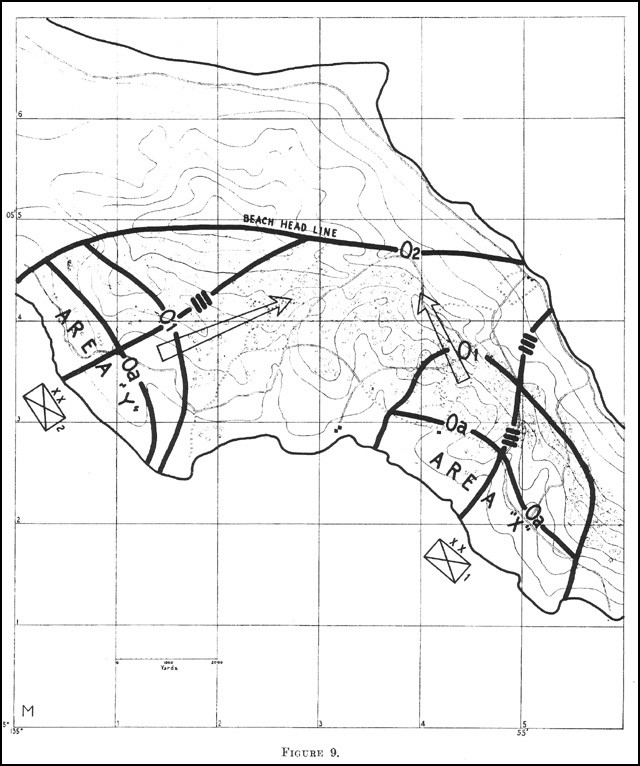

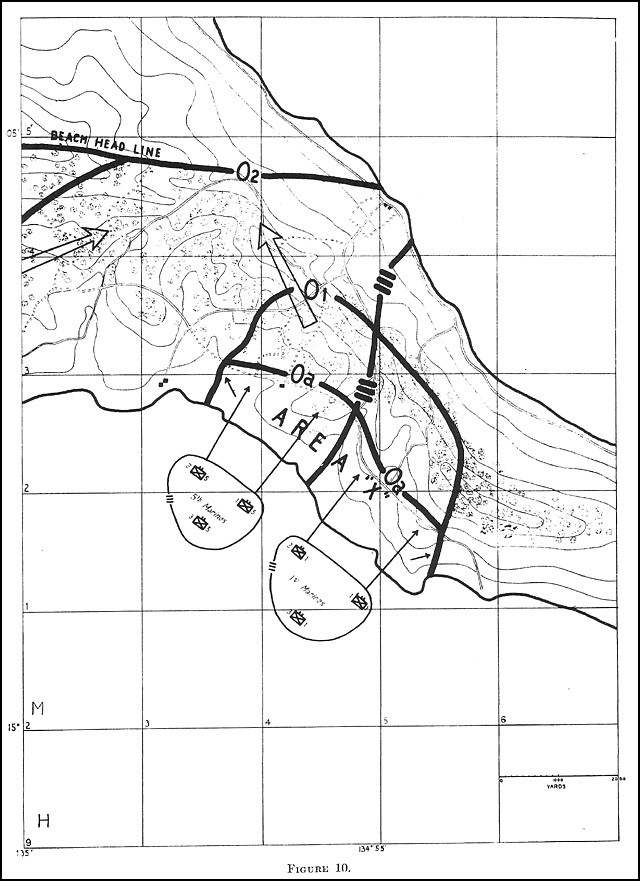

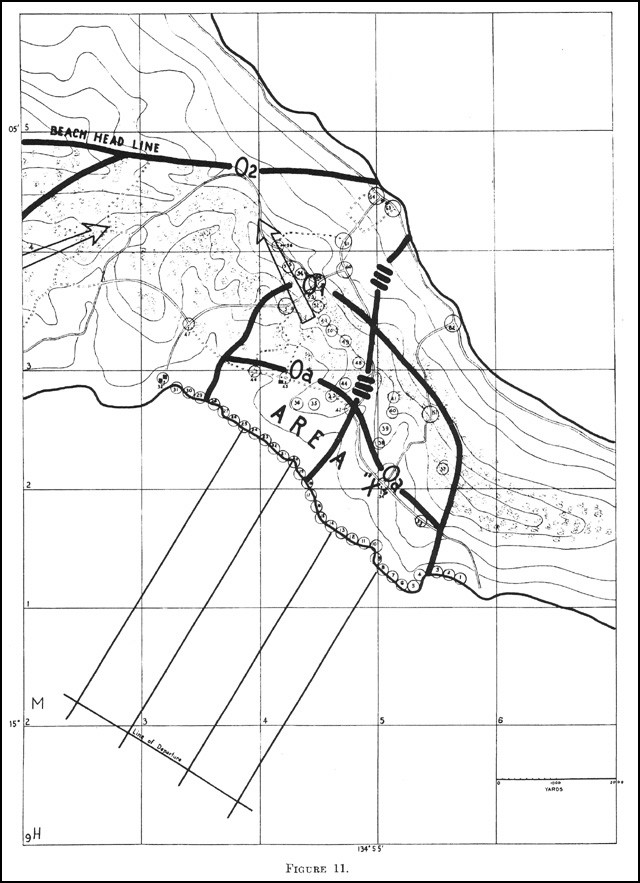

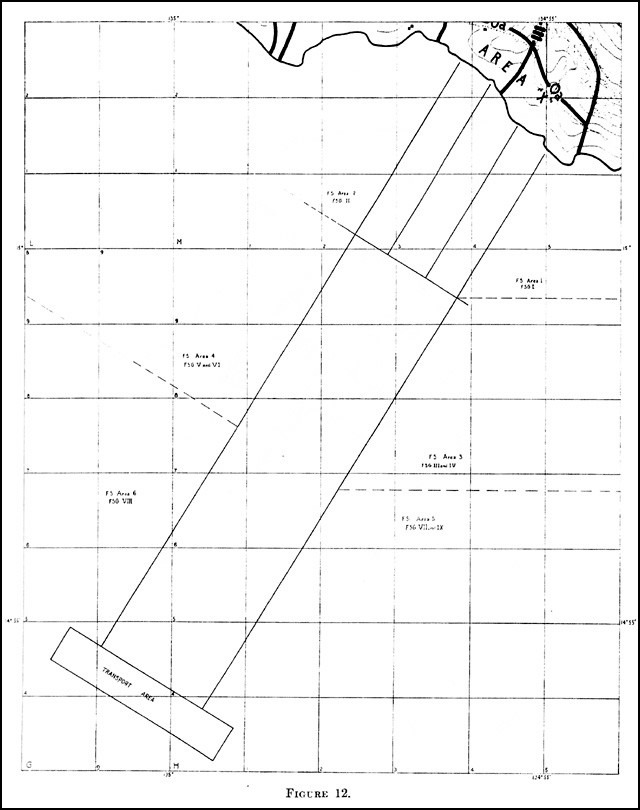

151. Illustrative diagrams - Scheme of maneuver. -

a. The following figures illustrate diagrammatically the application of the foregoing principles in the formulation of a scheme of maneuver for a landing operation under varying conditions as to number of beaches and form of coast line.

b. The diagrams are intended merely to illustrate general principles under certain conditions. In actual practice, these conditions may be encountered in a variety of forms and in an infinite number of combinations.

c. The broken lines in the diagrams are not necessarily objectives, but indicate simply how the maneuver may develop on shore. The actual location of objectives is dependent upon the contemplated maneuver on shore, the nature of the terrain, speed of landing, and the probable rate of advance.

d. The arrows in the diagrams indicate the direction of the main effort, that is, the direction in which the commander plans to exert the maximum effort in the accomplishment of the particular task in view. This is a general direction only; diverging local maneuvers are often necessary by subordinate commanders, and all local successes should be vigorously exploited.

| --16-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

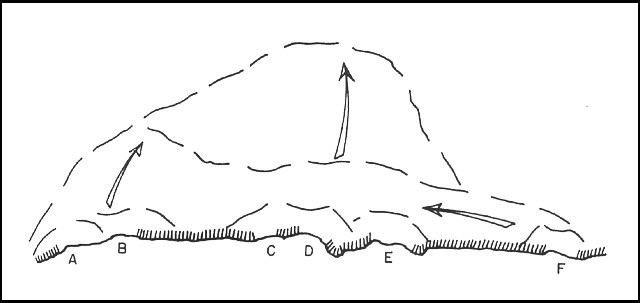

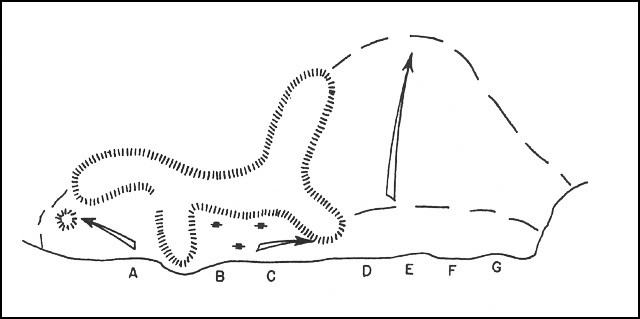

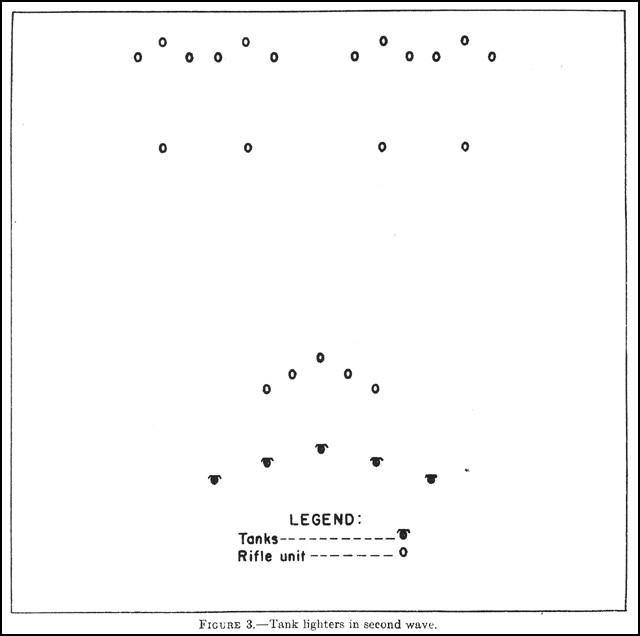

Figure 3 illustrates a landing and demonstrations, with a possible maneuver on shore, when the terrain, amount of naval gunfire, or hostile dispositions make it desirable to limit the landings to one beach, or to a few adjacent beaches.

This maneuver has the advantage of simplicity in the execution of the movement from ships to shore and permits the concentration of ships in support of the one landing.

This type of landing, however, enables the enemy to concentrate his artillery on the landing, facilitates the employment of hostile reserves, and entails the maximum extension of front after the landing is effected. Heavy counterbattery and interdiction fires should be employed in connection with such landings.

The demonstrations at C and D may be employed with any of the illustrations which follow. Demonstrations, made on the flanks of a landing, are desirable in order to disperse the enemy artillery fire and to confuse the enemy as to the actual point of landing. Reconnaissance of adjacent beaches may be conducted in connection with such demonstrations.

| --17-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

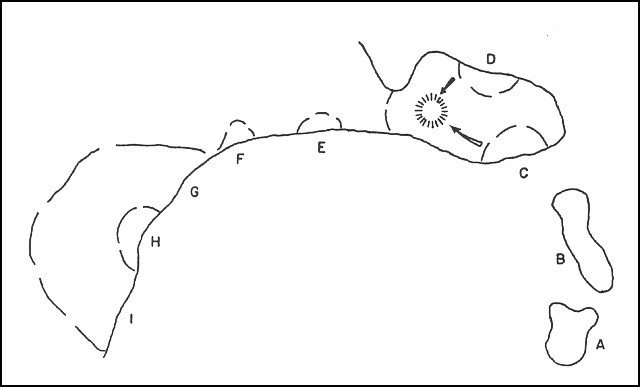

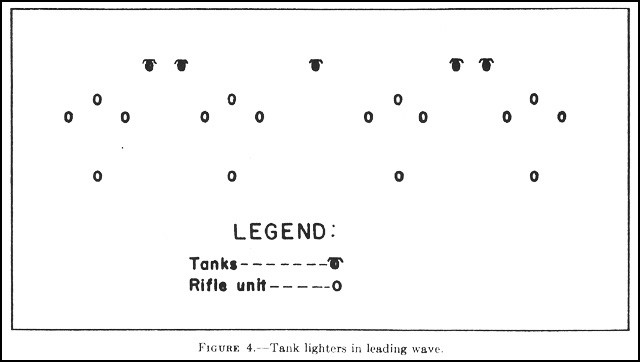

This maneuver is a modification of that shown in figure 3. It illustrates the capture by flanking action of a beach which is strongly defended or difficult of approach from seaward. Initial landings are made at A and B, which have better approaches, are more difficult to defend, or, on account of unfavorable landing conditions, are less strongly held than C. After the capture of C, landings may be continued at that beach, the troops landed at C being used to push the attack in the desired direction.

The landings at A and B may be made simultaneously or by echelon. In the latter case, ships' gunfire is used first to support the landing at A and then at B, or vice versa.

This maneuver may be used in connection with any of the illustrations which follow.

| --18-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

This diagram illustrates a landing on two beaches (A and B) separated to such an extent that the troops will be initially out of supporting distance. The landings at A and B, as in figure 4, may be made simultaneously or by echelon. In the latter case, the first landing is made at A and the second at B in order to facilitate the later support of the main effort. In the event of a success at A, however, consideration should be given to continuing the landing of troops at that point rather than making a new effort at B.

If sufficient boats are not available for embarking the entire landing force at one time, the first trip may be used for the landing at A and the second trip for the landing at B. In this type of maneuver, where a considerable period of time elapses between the various landings, hostile reserves may be deflected toward the first landing and away from the main effort.

| --19-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

Figure 6 illustrates a landing when a number of beaches are available. The main effort may be initially on the flanks and later in the center. Simultaneous landings are made first at A and F, then at B and E, and finally at C and D, the later landings being assisted by fire and movement from troops previously landed.

Modification of this maneuver may be made by starting at one flank and working toward the other, or by making a simultaneous landing at all beaches. In the latter case, a large number of supporting ships would be necessary.

When sufficient boats are available to transport the bulk of the landing force in one trip, permitting short time intervals between the various landings, this general type of maneuver enables a large number of troops to be put ashore in a short period of time. This is particularly advantageous when the defender has large central reserves, necessitating great speed in the execution of the landings and in the development of the operations on shore.

| --20-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

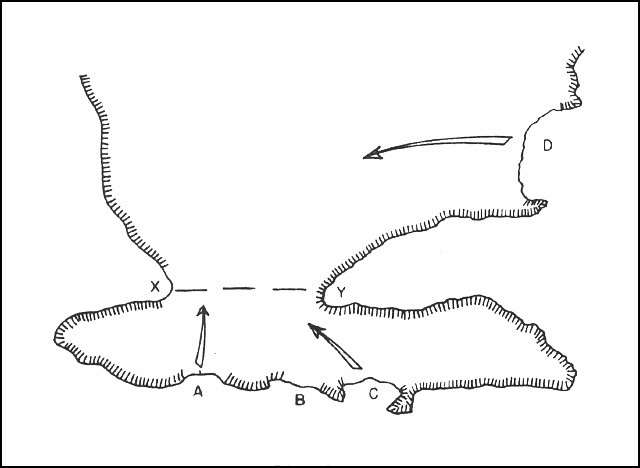

This maneuver illustrates the seizure of terrain in the vicinity of beaches A, B, and C, which later may be used in connection with the main effort at D.

The landings at A, B, and C may be made in accordance with the maneuvers illustrated in the preceding figures. The landing at D may be delayed until enemy forces have been drawn toward A, B, and C, and the advance inland from D may be used to outflank a defensive position such as X-Y.

In some cases, the plan may visualize landing at D only in case the advance from A, B, and C is stopped. This type of maneuver is particularly applicable where there is a naturally strong defensive position, such as X-Y, barring the advance inland from certain beaches which, in consequence, appear to be lightly held. This maneuver presupposes a marked superiority on the part of the attacker.

| --21-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

In the above maneuver only one landing against opposition is contemplated. A limited beachhead is first secured at A. The troops then push on, capture B, and establish the necessary beachhead to permit an unopposed landing there. Troops landed at B then capture C by a similar maneuver.

This type of maneuver is less fatiguing on the landing force than other types of landings at a single beach, in that the troops landing at B and C do not have to march from A. They are however, landed in close proximity to the front lines. The execution of the landing in this maneuver is relatively slow, and it is generally suitable only when two or more boat trips are required, and where some natural obstacle protects the exposed flank, facilitating a rapid advance, from beach to beach.

| --22-- | Change 1 to FTP-167 |

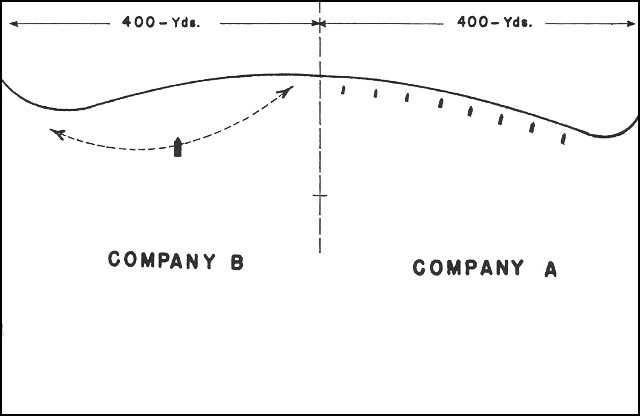

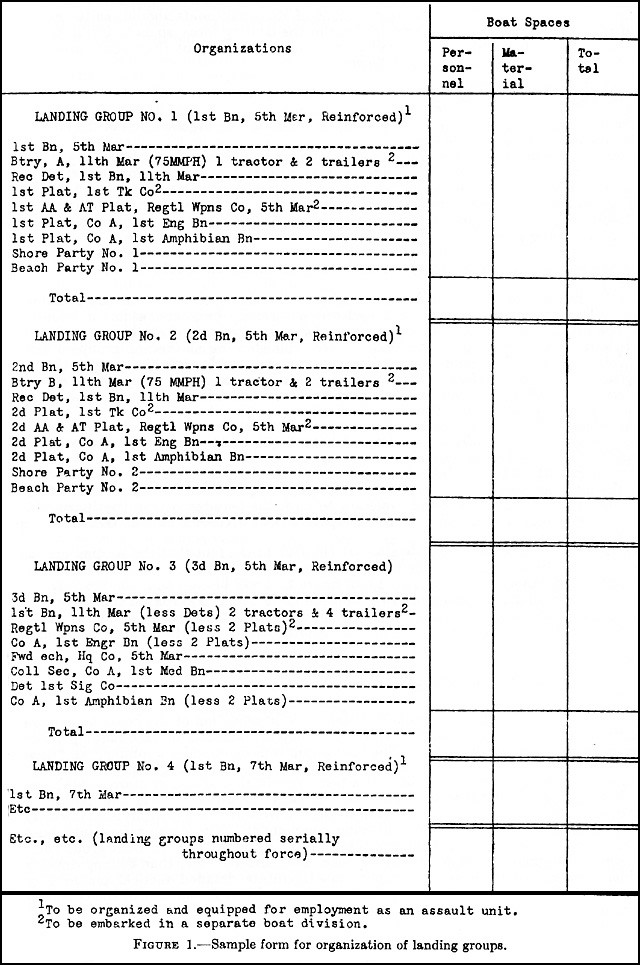

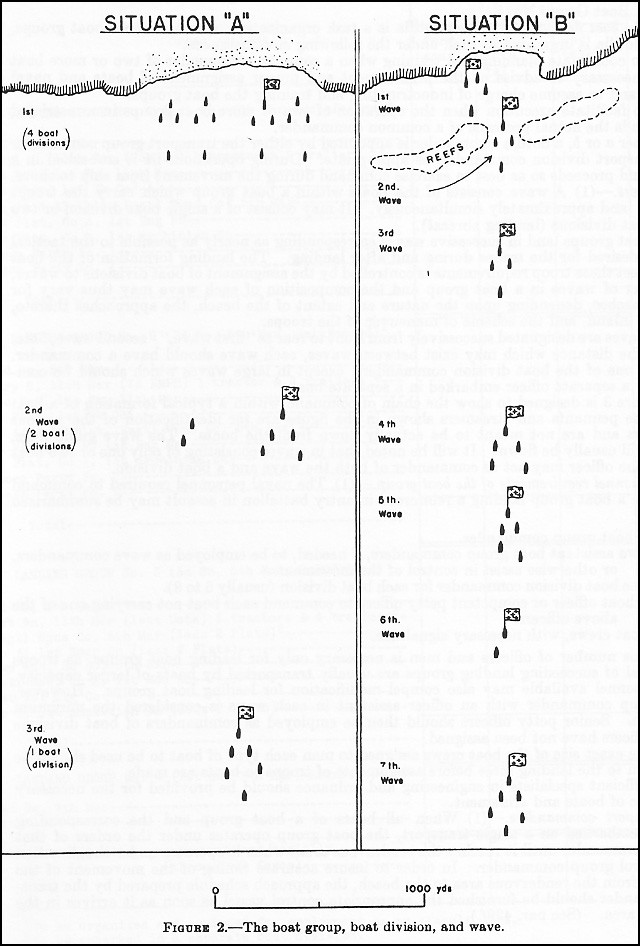

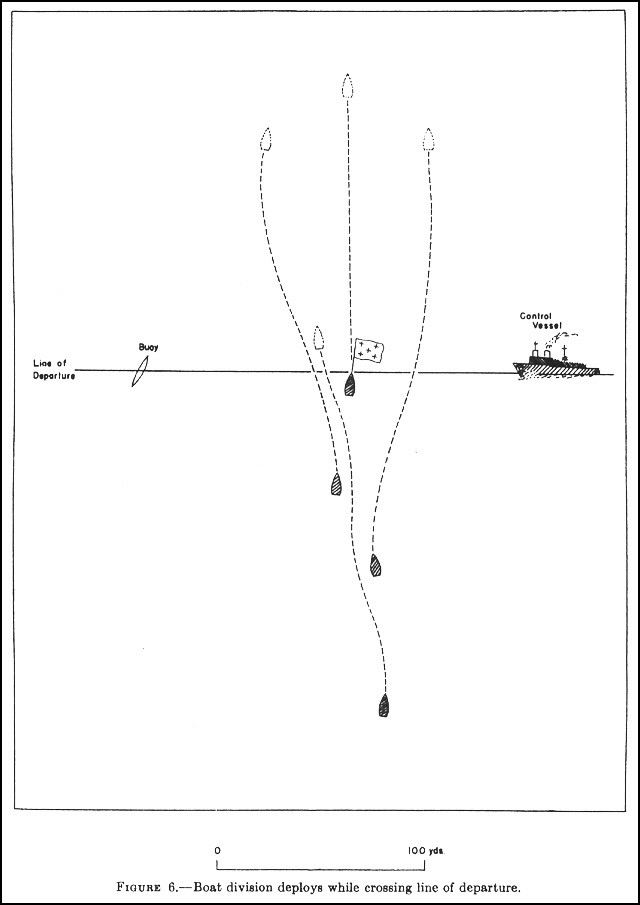

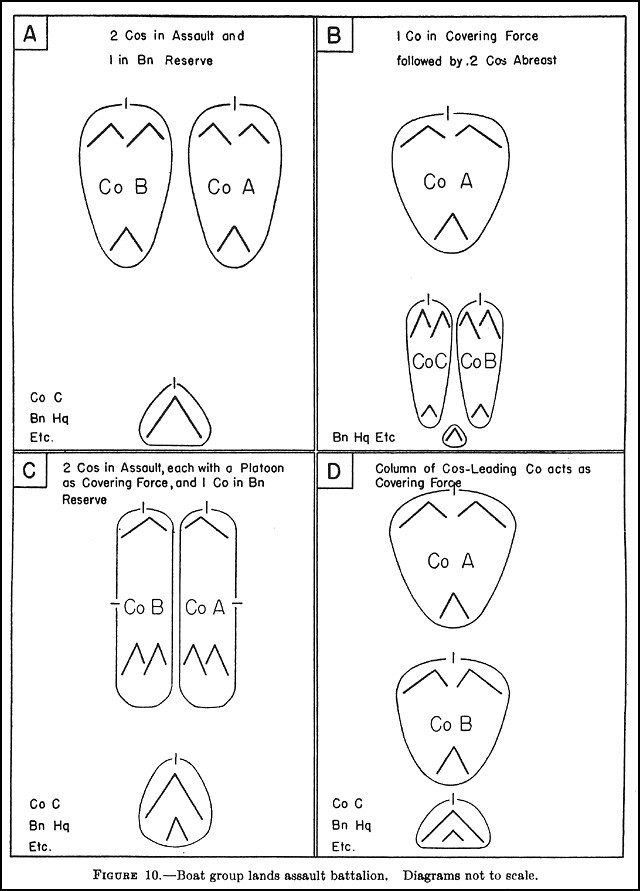

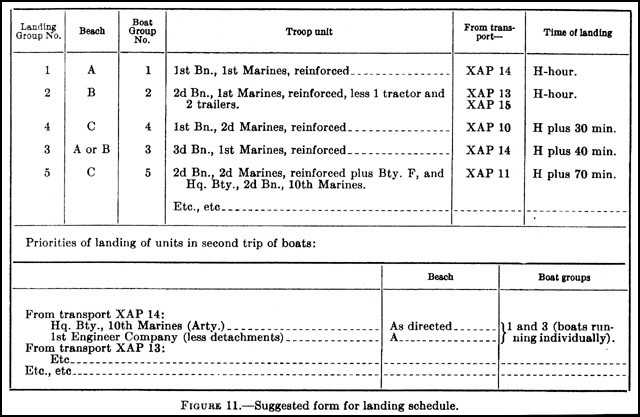

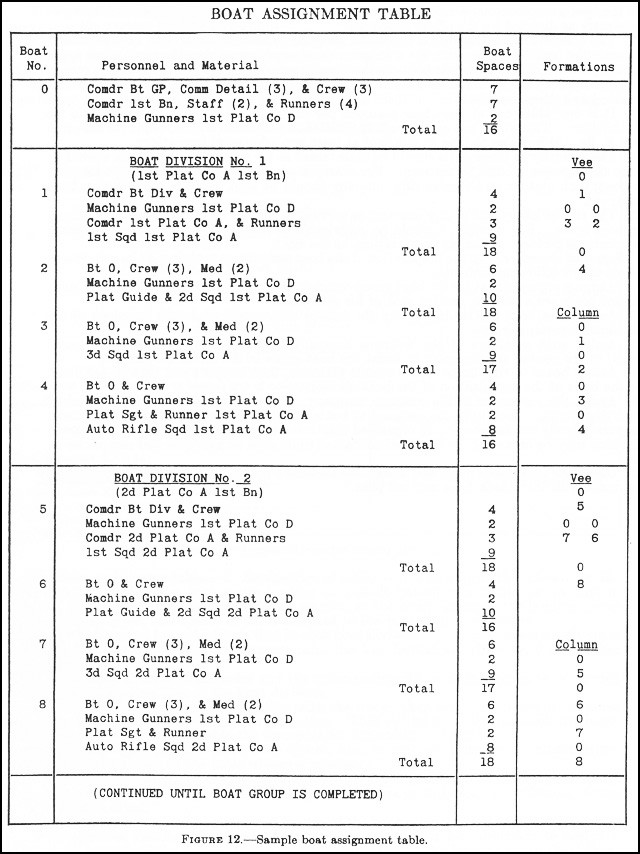

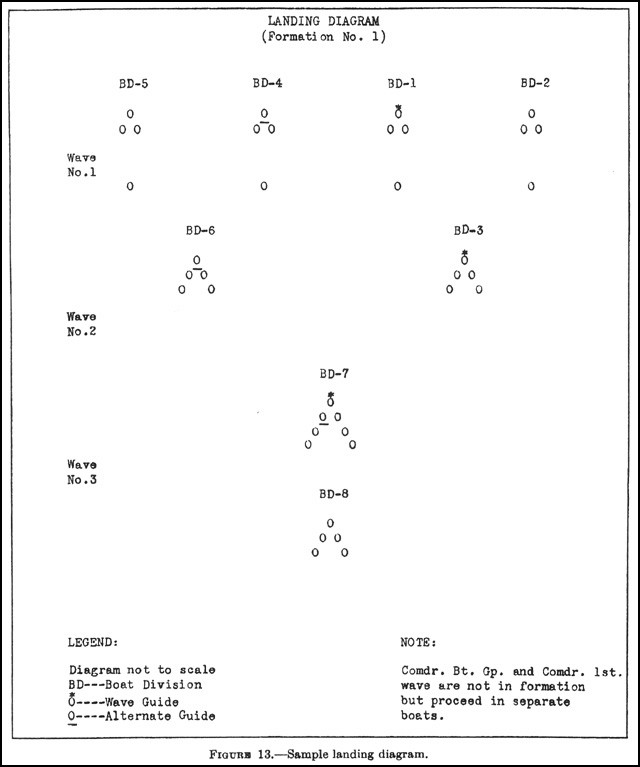

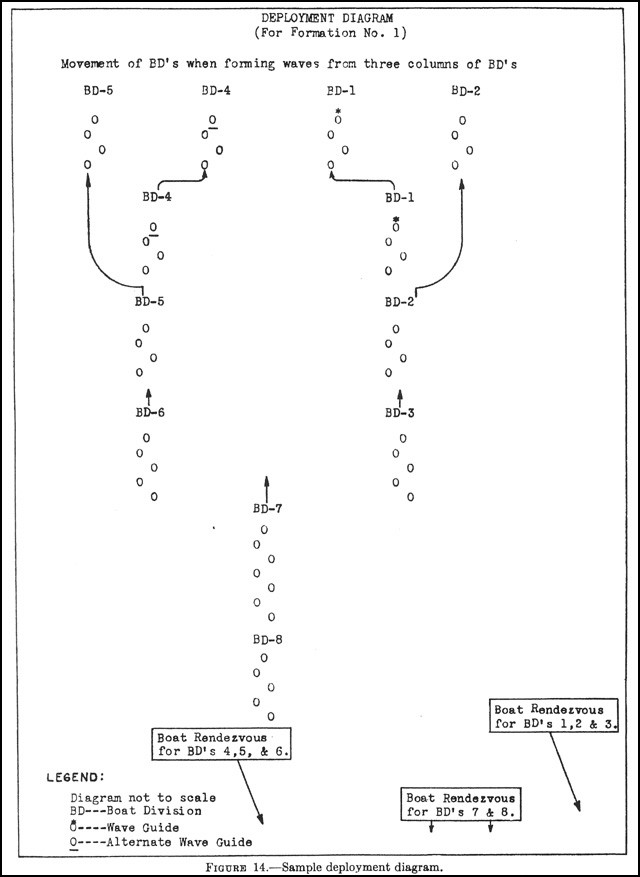

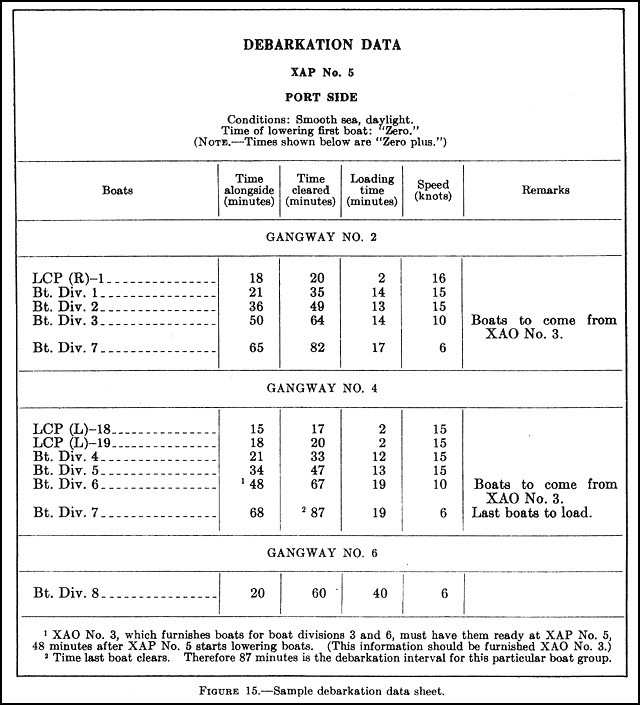

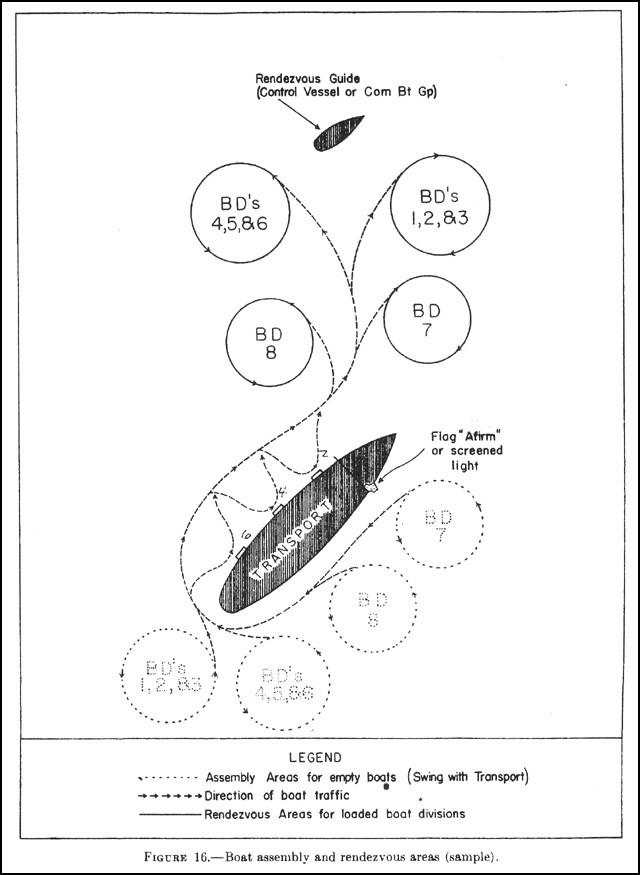

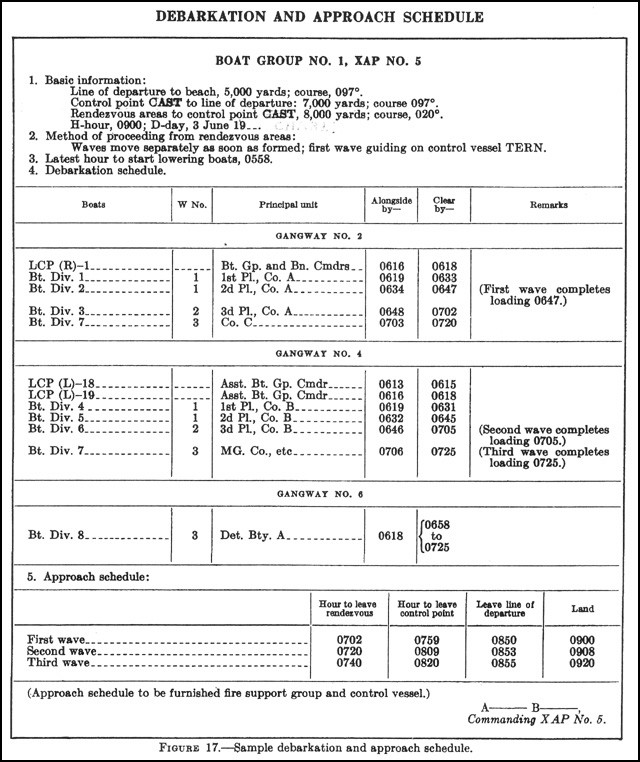

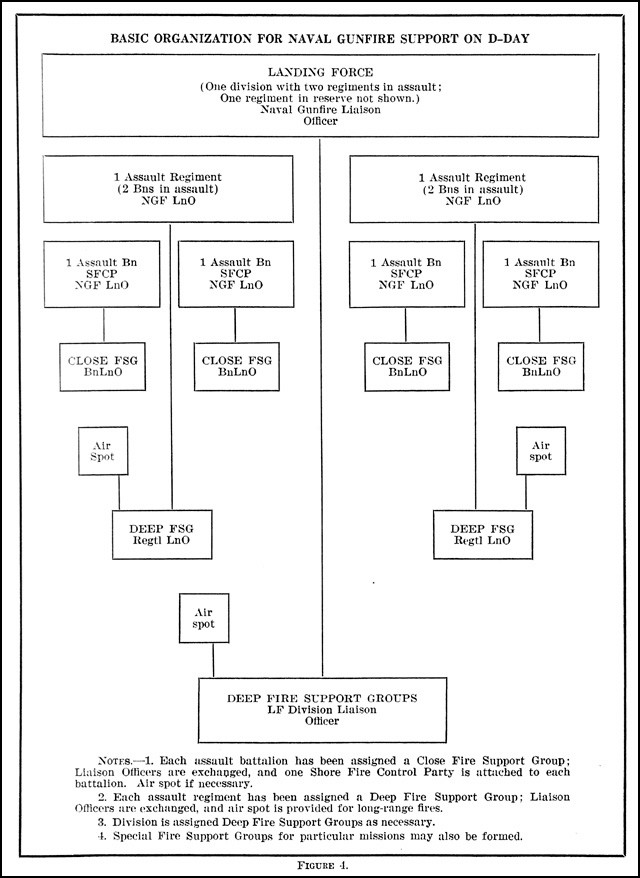

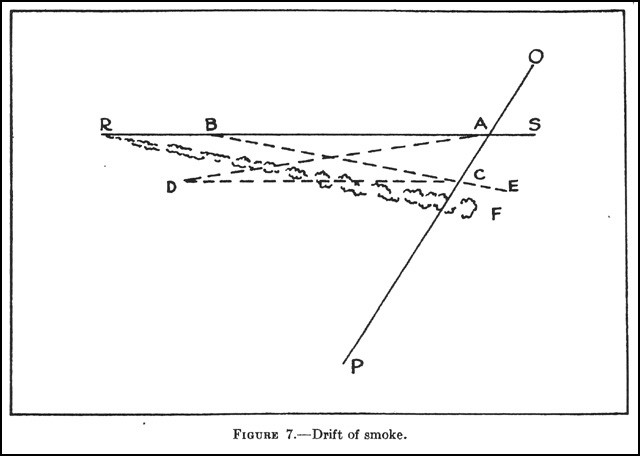

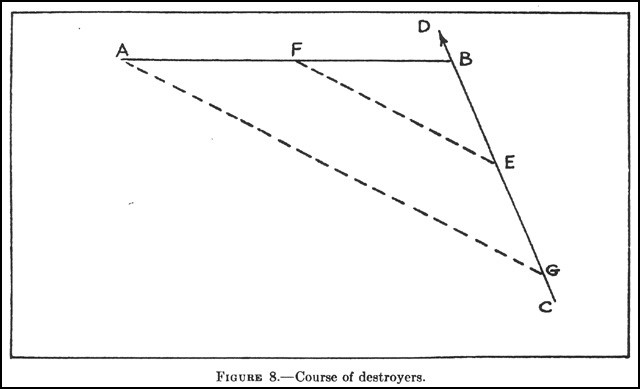

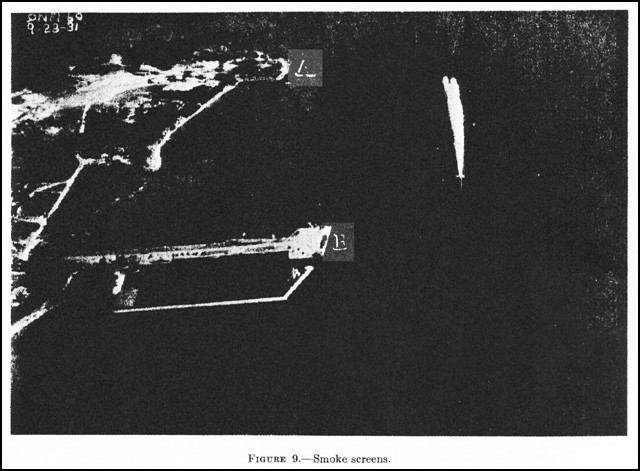

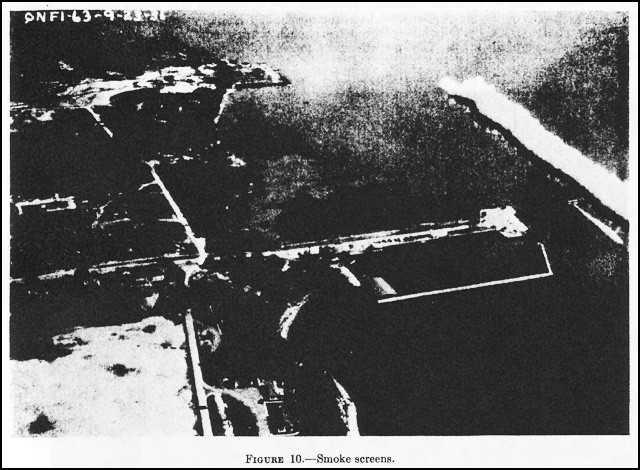

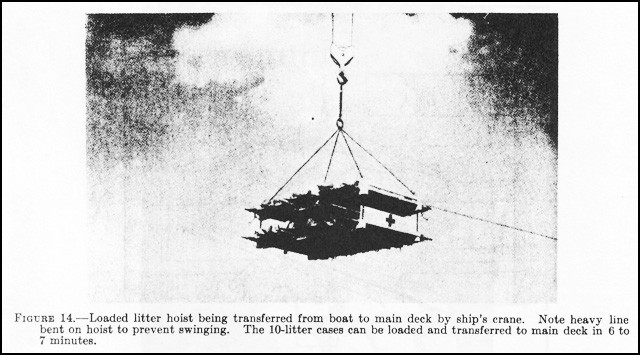

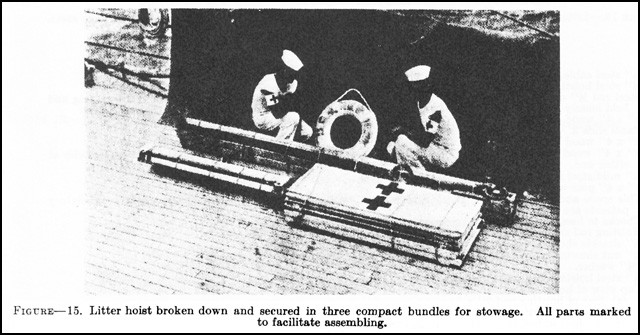

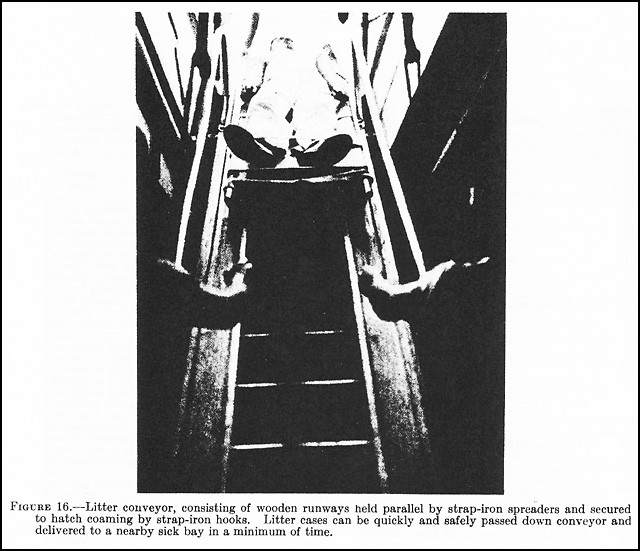

This figure illustrates a simultaneous landing on a long shore line having favorable landing conditions throughout its entire extent.