The Navy Department Library

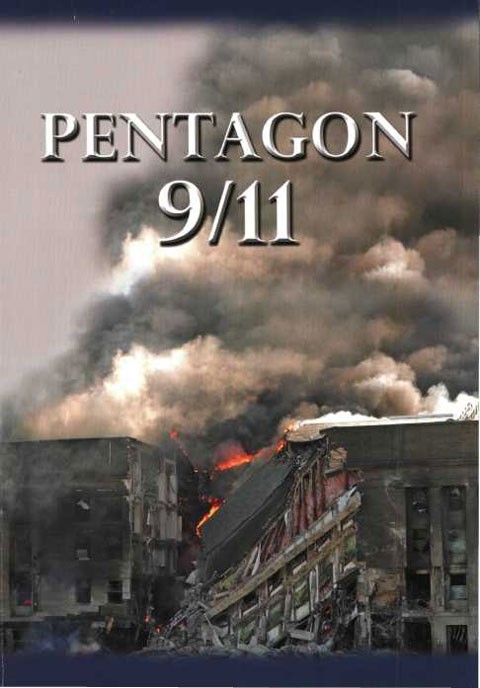

Pentagon 9/11

The following is a transcription of the published work Pentagon 9/11 (Defense Studies Series), the official Department of Defense history of the attack on the Pentagon on 11 September 2001. The complete text is available to download as a PDF here.

Many of the oral histories cited and listed in the bibliography in this published work have been made available online and can be found on the Navy Archives AR/670 DET 206: Documenting the Attack on the Pentagon on 9/11 collection page.

For more NHHC content related to the attacks on 11 September 2001, visit The 9/11 Terrorist Attacks Browse by Topic page.

Defense Studies Series

Pentagon 9/11

Alfred Goldberg

Sarandis Papadopoulos

Diane Putney

Nancy Berlage

Rebecca Welch

Historical Office

Office of the Secretary of Defense

Washington, D.C · 2007

This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of the 0-16 ISBN prefix is for U.S. Government Printing Office Official Editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN.

It is prohibited to use the Department of Defense seal, as appears on the title page, on any republication of this material without the express, written permission of the Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense. Any person using official seals and logos in a manner inconsistent with the Federal Regulations Act is subject to penalty.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pentagon 9/11 / Alfred Goldberg... [et al.].

p. cm. - (Defense studies series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-16-078328-9

1. September 11 Terrorist Attacks, 2001. 2. Pentagon (Va.). 3. Terrorism - Virginia - Arlington. 4. Rescue work - Virginia - Arlington. I. Goldberg, Alfred, 1918- II. United States. Dept. of Defense. Historical Office.

HV6432.7.P43 2007

975.5'295044 - dc22

2007016098

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800

Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001

ISBN 978-0-16-078328-9

Preface

As no other event in U.S. history, not even Pearl Harbor, the deadly assaults on New York and Washington that took the lives of almost 3,000 people on 11 September 2001 shattered the nations sense of security. The utter destruction of the Twin Towers in New York and the severe damage done to the Pentagon by Middle East terrorists signaled a changed world in the making, one that poses a constant threat of attack that the United States must guard against and defeat if its people are to live in freedom and safety. The nation responded first with stunned surprise and overwhelming grief, then with outrage and stern refusal to be intimidated.

What happened at the Pentagon that day and for days afterwards is a compelling story of trauma and tragedy as well as courage and caring and an instructive case study in coping with such appalling contingencies. Any history of this event must relate the resolve and fortitude exhibited by the military and civilians most immediately affected as well as the indispensable help that came from thousands of responders in the aftermath. In the first terrifying minutes after the plane crashed into the building the swift actions of survivors and rescuers helped save the lives of many who would otherwise have perished. The prompt response and subsequent performance of federal, state, and especially local agencies, in particular their coordination and cooperation with each other and with Pentagon

--i--

authorities, provided invaluable lessons for dealing with other large-scale emergencies in the future.

The Department of Defense undertook preparation of a history of the 11 September 2001 attack on the Pentagon at the suggestion of Brig. Gen. John S. Brown, director of the U. S. Army Center of Military History. The OSD Historical Office initiated the project as a Defense Historical Study - a joint endeavor on behalf of the Department of Defense. At the request of the director of the Naval Historical Center, the OSD Historian assigned responsibility for preparation of the study to the Naval Historical Center.

Reconstructing and clarifying this complex event required a collaborative effort. A first draft of the history was prepared by Sarandis Papadopoulos of the Naval Historical Center. He performed extensive research, conducted and directed a large number of oral history interviews, and provided an overall framework for further review and revision. Edward Marolda of the Naval Historical Center edited the manuscript and provided a second draft. A third and final version was prepared by members of the staff of the OSD Historical Office - Alfred Goldberg, Diane Putney, Nancy Berlage, and Rebecca Welch. They performed much additional research including oral history interviews, reorganized and rewrote the manuscript, thoroughly edited it, and checked it rigorously to insure accuracy of fact and of use and citation of all sources. Stuart Rochester gave the manuscript a final review and prepared the book for publication. The final product reflects the efforts of all of these participants and the researchers, compilers, editors, and fact checkers who assisted them.

Above all, this book would not have been possible without the cooperation of the more than 1,300 people who participated in oral history interviews conducted by the historical offices of the Army (almost 900 interviews), Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and OSD. The interviews were conducted by staff members of these offices and by Army and Navy reservists who entered on active duty for the purpose. Most of the firsthand evidence needed to provide the foundation for an evocative, broad-based historical narrative comes from these far-ranging interviews. Until a fuller and more definitive in-depth history can be written, this account represents the most comprehensive effort to date to capture what occurred at the Pentagon on 9/11. Although there are intricate treatments of the crash scene and the physical impact of the collision, the work is not

--ii--

as much concerned with elaborate technical analysis, which can be found in afteraction reports and other literature, as with conveying in accurate and sufficient detail both the essential chronology and the kaleidoscopic nature of the unfolding developments that day, including evoking both the shock and destructiveness surrounding the catastrophe. The focus is on what happened to people and to the building on 11 September 2001 as seen chiefly through the eyes of participants and observers. The huge cast of thousands includes the dead and injured, survivors, rescuers, firefighters, medical attendants, FBI agents, police, Defense military and civilian volunteers, forensic specialists, morticians, representatives of scores of federal, state, local, and volunteer organizations, family assistance staff of the Department of Defense, and the families of the survivors. The many recollections of individual experiences are as fragmented as was the collapsed E Ring section of the building. As with rebuilding of the collapsed area, this account had to reconstruct the sequence and progression of events piece by piece.

The necessary reliance on oral history interviews varying greatly in scope, recollection, and quality presented a challenge in establishing a dependably accurate and consistent record. A number of survivors, rescuers, and responders still suffered from the physical and emotional effects of their traumatic experiences when interviewed days, months, and even years later. Given the circumstances in which those in the impact area found themselves - shocked, injured, dazed, fearful, disoriented, gasping for breath - it is understandable that they could not retain clearly all that had happened to them or that they had observed. Even where witnesses had vivid recollections of their experiences they often acknowledged lack of precision in recalling all that had happened - time, place, people, and circumstances. Physical factors - smoke, darkness, fire, debris, and other hazards - all contributed to disorientation and confusion. It is not surprising, therefore, that versions of the same event by participants or observers viewing the scene from individual perspectives often differed and therefore had to be weighed carefully. Still, it was necessary to make prudent judgments where discrepancies existed. Material used in this study was distilled from the enormous amount of information available from the more than 1,300 interviews, of which we found it possible to use only a representative portion, relying on the corroborative testimony of two or more witnesses wherever possible.

--iii--

Of the many problems encountered in seeking to render an accurate and authoritative account, the most difficult was to establish an exact timeline for 11 September. Few participants or observers could pinpoint precise times for what happened - the building collapse, arrivals and departures, rescues, treatment and evacuation of injured, the progress of fires, warnings and evacuations, building searches, and escapes from the wreckage. For many of the day's developments the best that can be done to identify time of occurrence is to use such locutions as "about 10:00 a.m.," at "approximately 11:15," "between 1:00 and 2:00 p.m." This is especially necessary where there are conflicting recollections or gaps in the available evidence, and other sources such as physical documentation did not permit the authors to resolve the discrepancies or achieve absolute certainty. In general, there may be confidence in the accuracy of the sequence of events if not the exact time of each.

Space does not allow giving here the credit due many individuals who contributed importantly to this volume. We acknowledge them by name in a list appended after the text and regret any inadvertent omissions. The hundreds of oral history interviews cited in the study appear in a list included in the bibliography.

Finally, although this volume was prepared in the Department of Defense, the views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the department.

Alfred Goldberg

OSD Historian

--iv--

Contents

| I. | Target: The Pentagon | 1 |

| The Building | 1 | |

| The Attack | 8 | |

| II. | The Deadly Strike | 23 |

| First Floor | 28 | |

| Second Floor | 36 | |

| Third Floor | 44 | |

| Fourth Floor | 45 | |

| Fifth Floor | 46 | |

| III. | The Rescuers | 50 |

| IV. | Fighting the Fire | 64 |

| The First Responders | 64 | |

| Command and Control | 72 | |

| Initial Search, Rescue, and Firefighting Efforts | 77 | |

| E Ring Collapse | 80 | |

| Inbound Plane Rumors and Evacuations | 82 | |

| Fighting the Fire "Tooth and Nail" | 86 | |

| The Roof Fire | 91 | |

| Searching and Shoring | 95 | |

| Logistics | 100 | |

| Operational Coordination | 102 | |

| V. | Treating the Injured, Searching for Remains | 106 |

| Medical Assistance | 107 | |

| Removing Remains | 119 | |

| VI. | Up and Running | 128 |

| National Command Authority | 129 | |

| Military Command and Operations Centers | 133 | |

| Keeping the Building Operating | 136 | |

| Open for Business on 12 September | 146 | |

| VII. | Securing the Pentagon | 149 |

| Defense Protective Service | 150 | |

| FBI and the Crime Scene | 157 | |

| Federal, State, and Local Police and the Old Guard | 161 | |

| Tightened Security and Military Police | 168 | |

| VIII. | Caring for the Dead and the Living | 177 |

| Identifying the Dead | 178 | |

| Organizing for Family Assistance | 186 | |

| Pentagon Family Assistance Center | 187 | |

| Continuity and Commemoration | 198 | |

| Afterword | 201 | |

| Appendices | 207 | |

| A. List of 9/11 Pentagon Fatalities | 208 | |

| B. National Transportation Safety Board Reports | 213 | |

| List of Abbreviations | 227 | |

| Notes | 229 | |

| Selected Bibliography | 253 | |

| Acknowledgements | 267 | |

| Index | 269 |

Illustrations

| 1. | The Pentagon in 2001 | 5 |

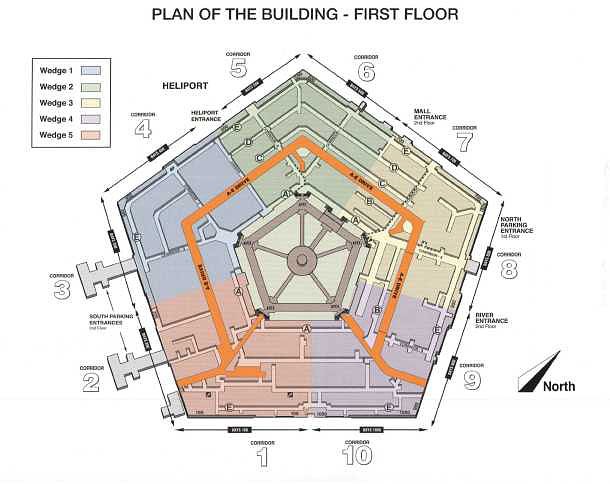

| 2. | Plan of the Building - First Floor | 7 |

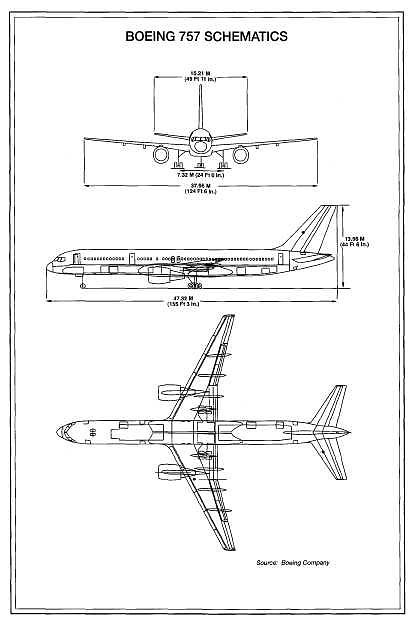

| 3. | Boeing 757 Schematics | 11 |

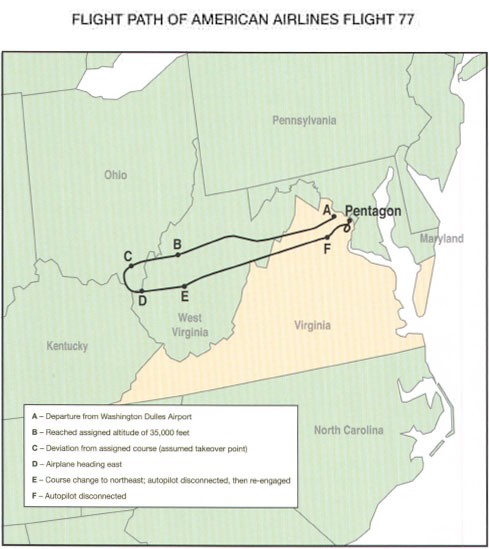

| 4. | Flight Path of American Airlines Flight 77 | 14 |

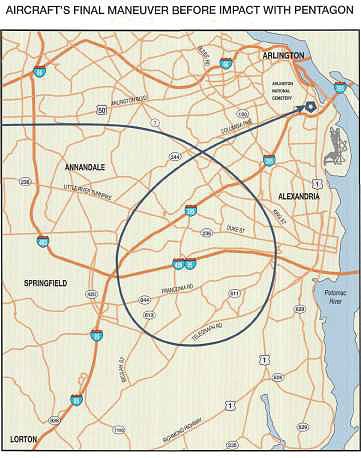

| 5. | Aircraft's Final Maneuver before Impact with Pentagon | 15 |

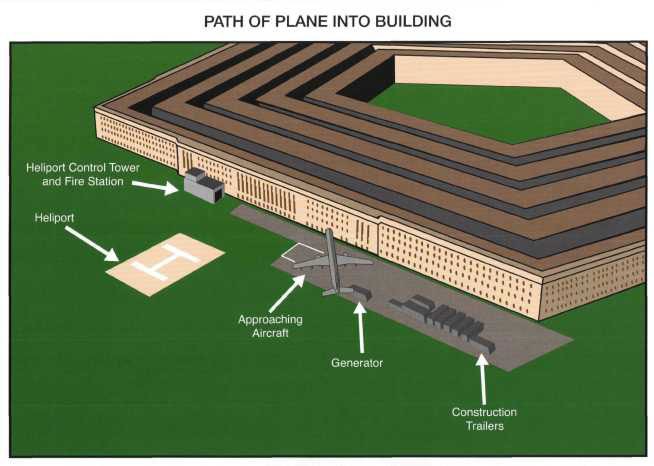

| 6. | Path of Plane into Building | 18 |

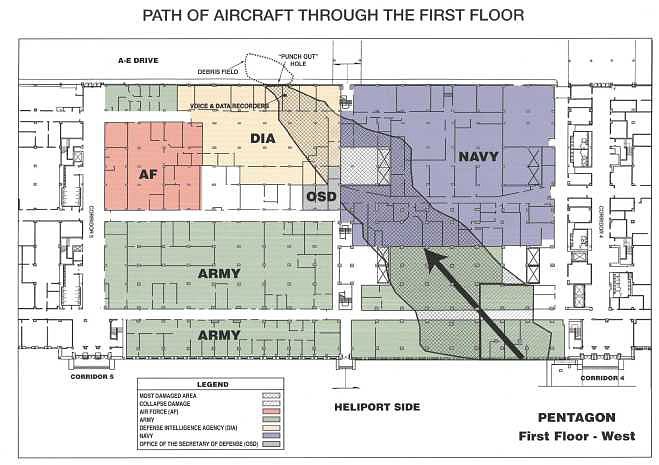

| 7. | Path of Aircraft through the First Floor | 21 |

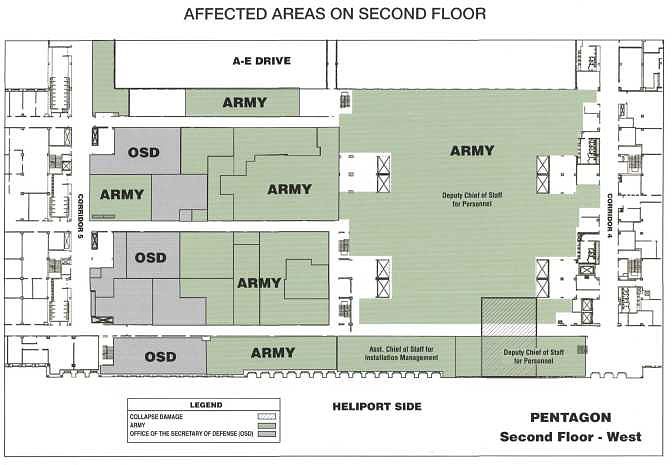

| 8. | Affected Areas on Second Floor | 38 |

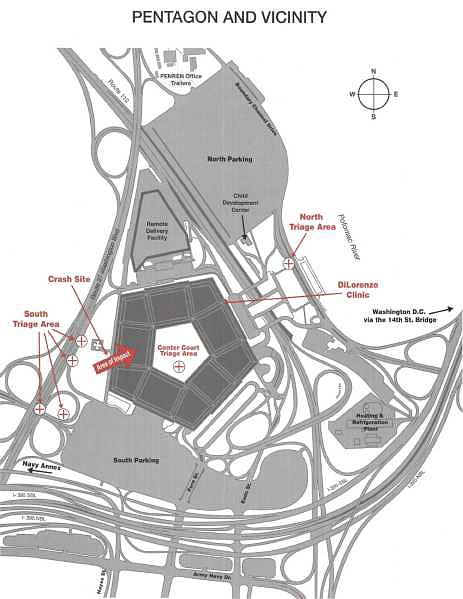

| 9. | Pentagon and Vicinity | 71 |

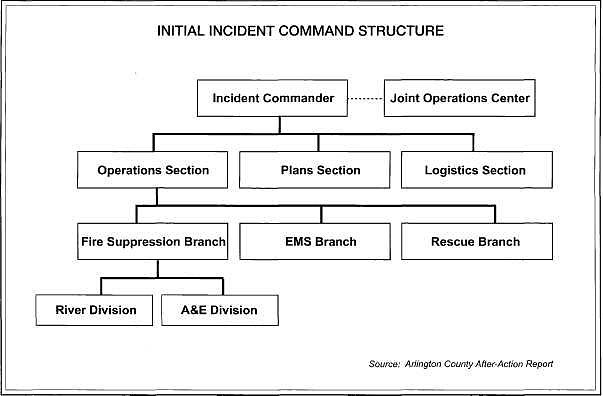

| 10. | Initial Incident Command Structure | 74 |

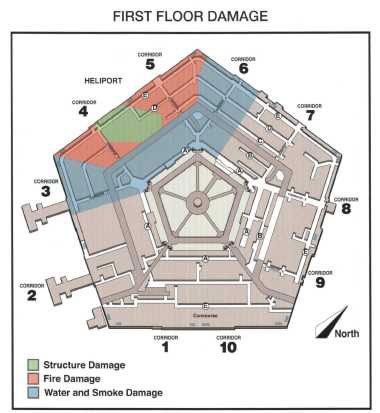

| 11. | First Floor Damage | 81 |

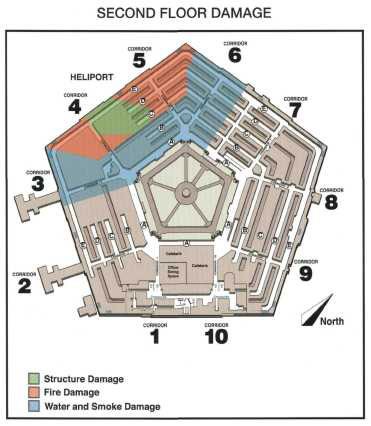

| 12. | Second Floor Damage | 88 |

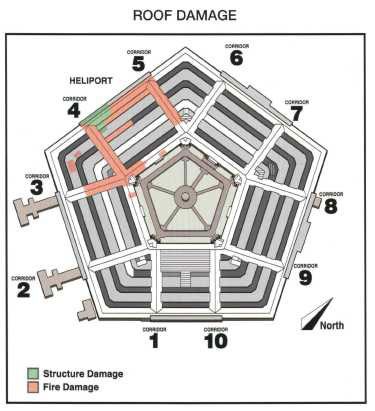

| 13. | Roof Damage | 94 |

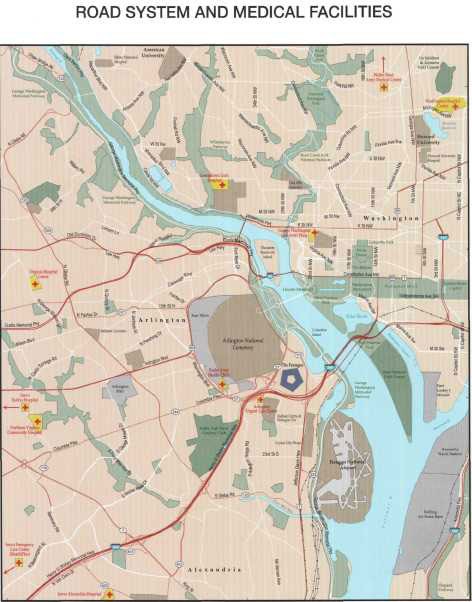

| 14. | Road System and Medical Facilities | 116 |

| 15. | Injured Disposition | 118 |

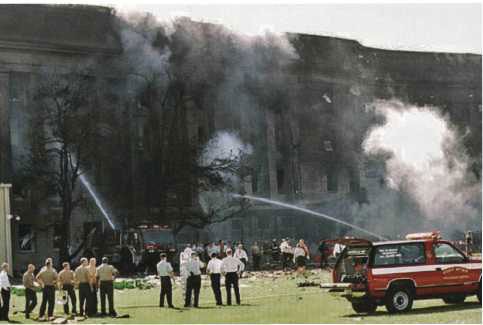

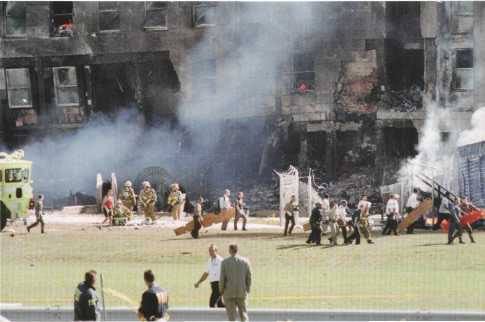

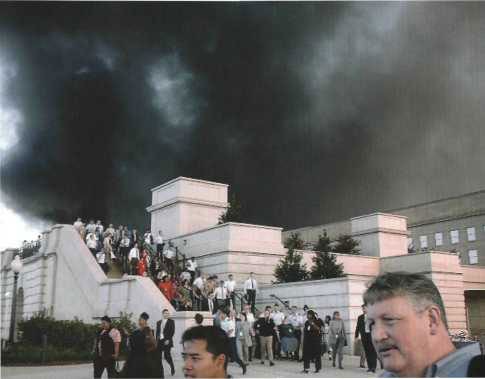

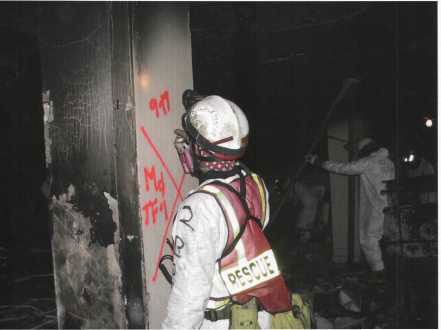

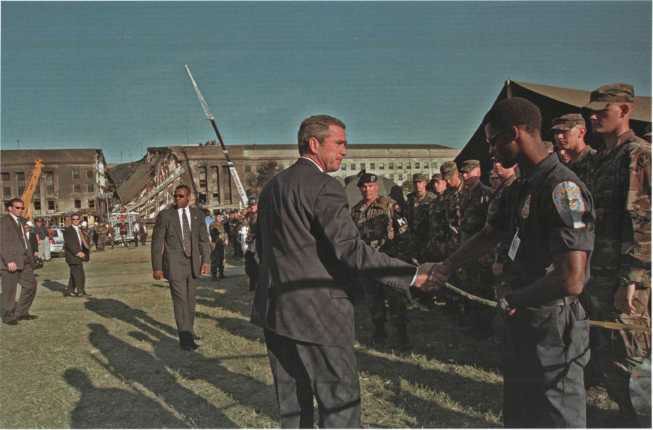

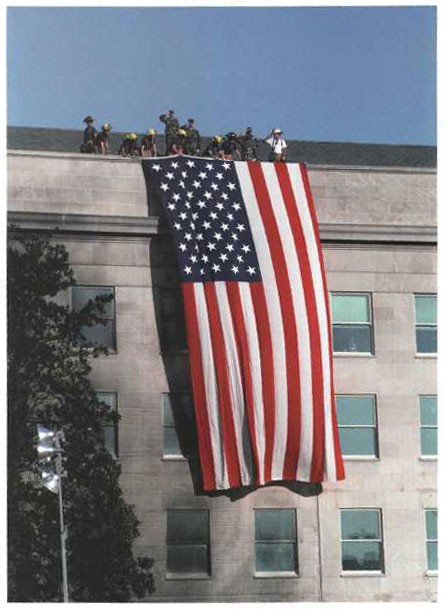

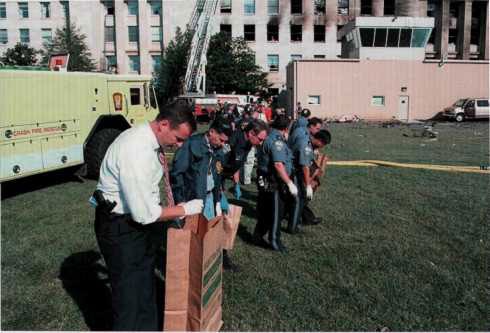

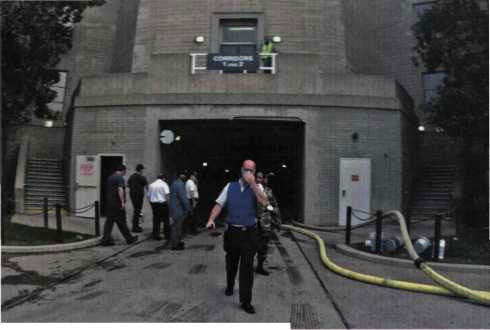

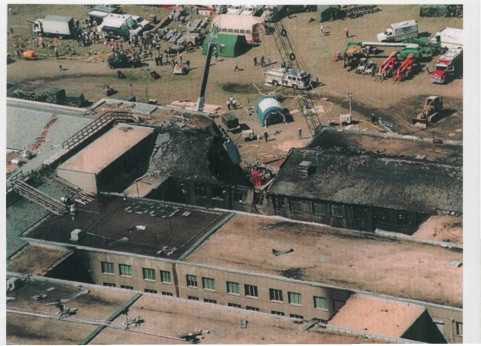

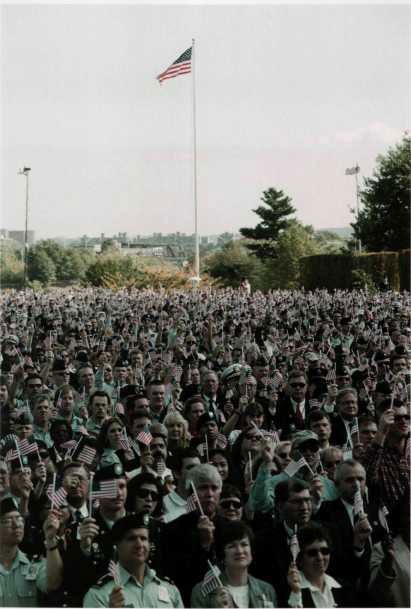

Photographs follow pages 82 and 162.

--v/vii--

Chapter I

Target: The Pentagon

Since World War II the Pentagon has stood as a symbol of American power and influence to the nation and the world. By 11 September 2001 it had been the command center of the nations military establishment for more than a half century. In retrospect it seems obvious that in some regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East, a U.S. military presence and perceived ascendancy should have made the Pentagon an object of fear and hatred and a likely target of attack by terrorist enemies.

The Building

Knowledge of the purpose, design, and construction of the Pentagon is requisite to understanding the deadly effect of the 11 September attack. The original conception of the huge structure in the summer of 1941 derived from the urgent need for space to house the rapidly expanding War Department headquarters in Washington. The shadow of the war in Europe and a growing threat in the Pacific from Japan had caused the United States to mount a partial mobilization of industry and manpower that greatly multiplied the activities and numbers of the Army in 1940-41. By July 1941 Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had obtained permission from his superiors to plan for a single

--1--

building to accommodate the burgeoning War Department staff scattered among 17 buildings in the Washington area.1

Where to place the building occasioned much controversy during the summer of 1941 until President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided in August on a site along the Potomac River in Arlington County, Virginia, directly across from Washington. Groundbreaking occurred on 11 September, exactly 60 years before the 2001 attack. The building was declared completed 16 months later, on 15 January 1943.

Originally the Pentagon Reservation had 583 acres; by 2001 it had shrunk to 280 because of transfers to other purposes. The building covers 29 acres; parking lots take up 67 acres. North and South Parking and other smaller parking areas accommodate about 10,000 vehicles. A Center Court of more than five acres provides appealing landscaping and more light for the inside A Ring. Of the 6.6 million square feet in the building, about 3.8 million were originally devoted to office space.

From the beginning, the building architects and engineers had decided on a pentagonal shape and a horizontal rather than vertical projection, limiting the height to four stories. The afterthought addition of a fifth story in 1942 raised the building's height to 71 feet, A low-rise structure of such massive dimensions - almost a mile around the exterior - gives the Pentagon a fortress-like appearance - not inappropriate for a military headquarters. The appeal of the pentagonal shape, second only to a circular shape in efficient design, lay in making it possible to reach anywhere in the huge building by foot in seven or eight minutes. Stairways, escalators, freight elevators,* and wide ramps provide ready access to all parts of the building. At the outset of construction, given wartime austerity and fiscal constraints, all parties involved agreed that it would be a no-nonsense building - no marble, no decoration, no ornamentation. Truly a pentagon, the structure has five concentric rings (labeled A to E from the innermost ring out), five sides, and five floors. Four light wells between the rings, mainly at the upper three floors, provide daylight for most offices. The dimensions are impressive - the five exterior walls are each 921 feet long, and the five innermost walls facing the Center Court each 362 feet long. From the outer face of E Ring to

_____________

* Since 2001 renovated sections of the building include passenger elevators and new two-way escalators.

--2--

the outer face of A Ring the building has an overall depth of 396 feet. The roofs are concrete and flat, except for those over the more visible A and E Rings and the 10 radial corridors, which are sloped and covered with slate tiles. Outermost walls are faced with limestone and backed with unreinforced 9-inch brick; inner ring walls are of 10-inch architectural concrete. The building rests on more than 41,000 concrete piles, ranging from 27 feet to 45 feet in height, that support an equal number of columns reaching to the roof. The buildings structural framework (floors and columns) is made of reinforced concrete.

Ten numbered corridors radiate like spokes from the A Ring apexes on the inside of the building to the E Ring on the outside. These wide corridors and narrower ones running through the middle of the rings provide 17.5 miles of hallways. The five rings are each 50 feet deep separated by 30-foot gaps known as light wells, except for a 40-foot-wide roadway, the A-E Drive, running through the light well between the B and C Rings, that provides access for vehicles to the Center Court from the outside of the building through tunnels at either end. In much of the building on the 1st and 2nd Floors there are no light courts between the C, D, and E Rings, so that office space is contiguous from the E Ring through the C Ring. The five exterior apexes are at the centers of the five "wedges." The five rings are segmented by expansion joints at four locations evenly spaced around the structure. Where load-bearing partitions are not present, non-bearing partitions separate offices. The five interior apexes at the A Ring have exits to the Center Court at the 1st and 2nd Floor levels. The buildings five-digit numbering system indicates the floor, the ring (a letter), the corridor, and the specific room. Thus, 2E460 (in the direct path of the crash) is on the 2nd Floor, E Ring, near Corridor 4.

The Pentagon Department of Defense (DoD) work force, numbering more than 30,000 military and civilians during World War II and the Korean War, had diminished to fewer than 22,000 people, more than half civilian, in 1998. After renovation work on Wedge 1 began in 1998, the buildings DoD population declined still further to about 18,000, where it stood on 11 September 2001.*

_____________

* The authorized personnel strength in the Pentagon for the years 1945-1998 is listed in Department of Defense Selected Manpower Statistics, Fiscal Year 1999, Table 1-7, prepared by Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports. In addition to DoD employees, the building's population usually included about 2,000 non-DoD employees, chiefly contractors.

--3--

Built originally for the War Department, the Pentagon eventually came to include the major headquarters components of DoD after its establishment in 1947: the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the three military departments - Army Navy, and Air Force. The Marine Corps headquarters did not join the other three services in the building until 1996. Accordingly, all of the most senior officials of the Defense Department have their offices in the Pentagon - the secretary of defense, the secretaries of the three military departments, the Joint Chiefs of Staff,* and the numerous high-ranking civilian and military officials who support them.

In 1989, approaching the half-century mark, the Pentagons historical importance and architectural merit received recognition by placement on the National Register of Historic Places. By that time it had also become apparent that the aging building urgently needed to be thoroughly renovated and made more secure. Concern about the vulnerability of the structure had for some time engaged the attention of responsible officials. There had been security incidents as long ago as the 1960s; on two occasions bombs planted in the building by unknown persons had exploded but caused little damage and no casualties. The growing terrorist threat in the 1980s and 1990s had led to a number of security improvements both inside and outside the building.

The structure's major deficiencies, as reported to Congress, centered on materials and engineering systems failures, fire protection and safety shortcomings, lack of technological modernization, and inadequate security. During its 50 years of existence, the original building systems had never been replaced or significantly improved. Consequently, all systems - heating, ventilation and air conditioning, plumbing, electricity, and telecommunications - required replacement and modernization to bring the building up to code. The 17.5 miles of corridors and the 100,000 miles of telephone cables indicated the scale of the renovation task. Some parts of the ground-supported basement floors between the piles had settled as much as 12 inches. Major structural modifications to the pile-supported foundation were required to create more usable space by enlarging the mezzanine floor to cover most of the basement. Windows, both casement and double-hung, were generally in disrepair and badly in need of replacement.

_____________

* The Defense Department has three military departments and four military services. The chiefs of the military services and a chairman and vice chairman constitute the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

--4--

--5--

Architectural elements - windows, doors, stairways - and the building facade (concrete and limestone), which showed cracks and spalling, required comprehensive overhaul. Removal of hazardous materials, especially asbestos, was another imperative. Moreover, the building did not incorporate modern fire and safety features. Finally, the machinery housed in the Heating and Refrigeration Plant, a separate building nearby, had become obsolete. This long bill of particulars underscored the need for a total renovation of the Pentagon.2

In 1990 Congress authorized a complete overhaul of the Pentagon, capping the cost at $1,218 billion in 1994. To plan and eventually oversee this huge undertaking DoD established under Washington Headquarters Services an office that evolved into the Pentagon Renovation Program Office (PENREN) in 1997. PENREN managed all aspects of planning and execution of the renovation and construction work, employing contractors for almost every phase of the project.3 It soon became evident that the original plan to complete the work within 10 years was optimistic; by 2001 planners projected a completion date of 2014. The first construction phase, a necessary preliminary to all renovation, was the new Heating and Refrigeration Plant and associated exterior utility projects beginning in 1993 and completed in September 1997. There followed the renovation of the basement and the extension of the basement mezzanine floor, a project of high priority and longer duration. Upgrading security stood high on the list for the next stage of reconstruction and renovation of the building proper, which began in 1998 with clearance of Wedge 1, most of whose approximately 5,000 occupants were moved to leased facilities in Northern Virginia by the end of the year. By September 2001, Wedge 1 had been largely reoccupied and work was under way on adjacent Wedge 2, which had been cleared of all but about 700 occupants.

Extending from midway between Corridors 2 and 3 to midway between Corridors 4 and 5, with more than one million internal gross square feet of space, Wedge 1 was only five days from official completion and housed about 3,800 people on 11 September. Corridor 4 provided access to Wedge 1 on all floors, but a temporary construction barrier wall midway between Corridors 4 and 5 limited access to Corridor 5 by Wedge 1 occupants in all rings on most floors,4

Under the renovation plan all of the walls, utilities, and asbestos in Wedge 1 were removed. The outer wall was reinforced with structural steel

--6--

--7--

tubing to increase its lateral stability and provide support to new blast-resistant windows. The buildings windows indeed required special attention. Analysis of attacks on large structures elsewhere bore out that flying glass from blast-shattered windows caused many casualties, including deaths. The Pentagons original 7,748 mostly casement-type windows, varying in size from 5x6' to 6x7', offered no resistance to blast-generated fragmentation. Reinforcing the windows on the outside of the E Ring and the A Ring would diminish the blast and fragmentation effects of exterior explosions. New windows for the E Ring,* the same size as their predecessors but with glass 1½ inches thick and weighing more than a ton apiece, were welded into special tubular steel frameworks. On 11 September many survived the blast.5

Long regarded as a physical security risk, the extensive south side loading dock for truck deliveries was replaced in August 2000 by a new 250,000 sq. ft. Remote Delivery Facility (RDF) adjacent to North Parking, some hundreds of yards from the Pentagon. Named for David Cooke, a longtime DoD administrator popularly known as the "Mayor of the Pentagon" and familiar to all as "Doc," the RDF was linked to the Pentagon by tunnel in February 2002, permitting unloading of large vehicles at a safe distance from the building. After deliveries were x-rayed, goods came into the Pentagon by electric-powered carts via the tunnel. Built largely for security reasons, two new pedestrian bridges at the south side of the Pentagon, entryways into Corridors 2 and 3 at the 2nd Floor level, provided massive barriers separating vehicular and pedestrian traffic.6

While security concerns received increasing attention as renovation progressed, the measures planned, under way, or instituted could neither anticipate nor fully defend against the powerful attack that came on 11 September 2001. Indeed, it is difficult to see how any realistic physical changes to the Pentagon could have deflected or greatly diminished the effects of the attack.

The Attack

For their assault on the U.S. homeland on 11 September 2001 the terrorists, identified as belonging to the al Qaeda network headed by Osama bin Laden, chose four targets known to the world as prominent symbols of American

___________

* New A Ring window glass was not as thick as the E Ring window glass.

--8--

prestige and power. The first two, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York, were icons representing American economic strength. The third, the Pentagon, represented U.S. military might. A fourth and highest-value target selected - presumably the White House or the Capitol - escaped attack when the hijacked plane destined for it crashed in Pennsylvania.

Previous attacks against U.S. official facilities by radical Muslim terrorists had occurred overseas: most notably the suicide truck bombing that killed 241 American military at the Marine barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, in October 1983; a similar strike against the Air Force Khobar Towers housing complex in Saudi Arabia in June 1996; the massive attacks on the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in August 1998; and the small-boat bombing of the destroyer USS Cole in Yemen's port of Aden in October 2000. The only strike within the United States by Middle Eastern terrorists occurred in February 1993 when they exploded a truck bomb in a parking garage under the World Trade Center in New York City, killing six people. Before 2001 the al Qaeda terrorists had decided to aim at more high-value and high-visibility targets in the United States.7

Over a period of two years before September 2001, in accordance with plans conceived by a network of al Qaeda plotters, the chosen agents entered the United States and made preparations for their stunning assault. They selected the most practical, lethal, and obtainable means of achieving their purpose - large aircraft carrying huge loads of explosive fuel. Beginning as early as July 2000, 14 months before the hijackings, several of the terrorists took flight-training courses. They acquired flight deck videos for Boeing 747, 757, 767, and 777 aircraft. By September 2001 the hijackers were ready.8

On the morning of 11 September, the terrorists hijacked four airliners, two from Boston's Logan International Airport, one from Newark Liberty International Airport, and one from Washington Dulles International Airport, in Northern Virginia. The two aircraft departing from Boston - American Airlines Flight 11 (11 crew, 76 passengers, 5 hijackers) at 7:59 a.m. and United Airlines Flight 175 (9 crew, 51 passengers, 5 hijackers) at 8:14 a.m. - were Boeing 767s bound for Los Angeles. Their flight crews each stopped transmitting within half an hour of departing, when they were over central New York State. Air controllers first registered concern at 8:21 a.m. when American Flight 11 turned off its transponder; the

--9--

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) sent its first warning of the hijacking of American Flight 11 to the Northeast Air Defense Sector (NEADS) of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) at 8:38 a.m.9

The call from the FAA did not come in time. The military had less than 9 minutes' warning before the first airliner hit the World Trade Center and 25 minutes before the second. The Air National Guard launched two F-15 fighter planes from Otis Air Force Base, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, at 8:53, too late to intercept the hijacked aircraft. Flights 11 and 175 hit the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center at 8:46 a.m. and 9:03 a.m. respectively, with the fighters still 70 miles distant at the time of the second crash. Otis and Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, each with a pair of fighters at the ready, were the only two alert sites available to NEADS for air defense of New York and Washington. Just 14 fighter planes on alert guarded the whole of American airspace that morning. The New York City attacks caused the South Tower to collapse at 9:59 a.m. and the North Tower at 10:28 a.m., killing more than 2,700 people.10

United Flight 93 (7 crew, 33 passengers, 4 hijackers), a Boeing 757 bound for San Francisco, left Newark at 8:42 in the morning. At approximately 9:24 a.m., NEADS ordered Langley Air Force Base, near Norfolk, Virginia, which had been put on alert at 9:09, to prepare to scramble fighters presumably to intercept not Flight 93, but Flight 11, mistakenly thought to be moving south, this almost 40 minutes after Flight 11 had struck the North Tower. Another 40 minutes later, after a struggle between the hijackers and passengers, Flight 93 crashed into the ground near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, killing all on board.11

The conspirators no doubt chose and methodically planned the takeover of these particular flights to maximize explosive damage. Because all four aircraft were headed nonstop for the West Coast, they carried large loads of highly volatile fuel. The full force of their destructive power became apparent when Flight 175 hit the South Tower in New York; the resulting jet fuel fireball exploded downward into lower floors.12

Near-simultaneous departure and subsequent hijacking of the four planes, all of which took off within a period of 43 minutes, maximized the element of surprise, allowing the FAA little time to warn pilots in U.S. airspace. The huge number of aircraft - more than 4,600 - aloft over the continental United States

--10--

--11--

made it difficult for NORAD to identify the four rogue aircraft. Finally, the element of surprise reduced the time available to launch interceptors to divert or shoot down the hijacked aircraft, assuming that a decision to do so could have been made in time.13

At Dulles International Airport five hijackers boarded American Airlines Flight 77 bound for Los Angeles: Khalid al Midhar, Majed Moqed, Nawaf al Hazmi, Salem al Hazmi, and Hani Hanjour, of whom the first four were subsequently listed as "possible Saudi" nationals. Although some of the men set off metal detector alarms, they were passed through the security checkpoints. When the plane lifted off at 8:20 a.m. it had 64 people on board - a crew of 6 plus 58 passengers, including the 5 hijackers with their weapons, probably small knives and box cutters.

In a speculative reconstruction of what took place in the plane, it seems likely that over eastern Kentucky the hijackers made their move, probably between 8:51 and 8:54, and took over Flight 77. They either waited for a cabin attendant to knock on the flight deck door and then rushed the cockpit or took an individual cabin crew member or passenger hostage and used threats against the victim to gain access. Once on the flight deck the attackers either incapacitated or murdered the two pilots and then took over the aircraft. With one hijacker as pilot, the other four herded the passengers to the rear of the aircraft and forestalled any attempts to retake control of the aircraft before it reached its target. Under the control of the five terrorists, at about 8:55 a.m. Flight 77 turned south and then five minutes later turned eastward from a point near the junction of West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky. Hani Hanjour, who had received FAA pilot certification, no doubt piloted the aircraft.14

Tracking Flight 77 would not have been easy, even if controllers had been able to identify the plane to follow. Its transponder, a transmitter that broadcast the course, speed, and altitude of the airplane, was turned off at 8:56. The hijacker pilot refused to answer any radio messages, adding to the uncertainty of making a decision to dispatch military aircraft to intercept the airliner. For air traffic controllers the lack of a transponder signal meant they could not find the Boeing 757 until it crossed the path of a ground-based radar. In any event, there was not enough warning time for NORAD to take effective action. The only relevant action taken came in response to the erroneous FAA notice that Flight

--12--

11 was flying south toward Washington. At 9:30 a.m. Langley Air Force Base launched three* F-16s that were still about 150 miles away from Washington when Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon seven minutes later. The fighters had flown over the ocean in accordance with standing instructions and did not turn toward Washington until ordered to do so at almost the same time that the Pentagon was struck.15

The crashes into the Twin Towers, quickly perceived as terrorist attacks, were a call to action at the Pentagon. The acting deputy director for operations in the National Military Command Center, Navy Captain Charles Leidig, initiated a call for a "significant event" telephone conference of senior military leaders at 9:29, Leidig rejected the erroneous FAA warning that Flight 11 was heading for Washington. At 9:33 the Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport tower passed to the Secret Service Operations Center in Washington the alarming word that "an aircraft [is] coming at you and not talking with us." A minute later the plane, Flight 77, turned south below Alexandria, Virginia, then circled back to the northeast and flew toward Washington again. Its destination was the Pentagon, not the White House or the Capitol.*16

The final minute of the airliner's flight took it along an east-northeast course above an Arlington County, Virginia, roadway, Columbia Pike. County Police Department Corporal Barry Foust, stopped at a traffic light at the intersection of Walter Reed Drive and Columbia Pike less than two miles from the Pentagon, spotted the aircraft flying low, saw a plume of smoke, then radioed, "We just had an airplane crash ... must be in the District area." Three blocks further along, at the intersection of Columbia Pike with South Wayne Street, Police Motorcycle Officer Richard Cox observed the airliner flying so close to the ground that the polished underside of its fuselage reflected the images of the buildings it passed on its flight; then he heard an explosion.†17

____________

* The two fighters on alert were joined by a third, a spare aircraft that had not been placed on alert. NEADS had ordered Langley to send up three fighters.

† "At 9:34 AM the aircraft was positioned about 3.5 miles west-southwest of the Pentagon, and started a right 330-degree descending turn to the right. At the end of the turn the aircraft was at about 2000 feet altitude and 4 miles southwest of the Pentagon. Over the next 30 seconds, power was increased to near maximum....The airplane accelerated to approximately 460 knots (530 miles per hour) at impact with the Pentagon. The time of impact was 9:37:45 AM." (National Transportation Safety Board, "Flight Path Study - American Airlines Flight 77," 19 Feb 02. See Appendix B.)

--13--

Flying just above the Navy Annex Building and a Virginia State Police radio mast, both uphill from the Pentagon and adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery the hijacker pilot guided the Boeing 757 downhill and turned it in a northeasterly direction. Less than two seconds before the plane hit the Pentagon, R. E. Rabogliatti, a building management specialist at the Navy Annex, peered out of his office window and saw the airliner looming over the building. Later, recalling its screaming engines he judged that the pilot must have pushed the jet's throttle to the limit; he estimated its altitude at less than 150 feet. In the Army Operations Center in the Pentagon Basement, Brigadier General Peter Chiarelli

--14--

was told by "the INTEL folks" that an "aircraft was headed for D.C. and it was right about then that we heard the noise and the building had been hit."18

Others in the immediate vicinity who witnessed the impact recalled that the airliner struck several obstacles, including light poles on Route 27, on the way to its target. The right wing hit a portable generator and the right engine crushed

--15--

a chain link fence. The left engine smashed an external steam vault. Observers saw debris falling from the plane and the building. Five images from a Pentagon security camera, approximately a second apart, recorded the approach, the crash, and the immediate effect - a huge fireball.19

Witnessing the fiery crash from above was the crew of a C-130 transport plane that had taken off from Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, minutes before. As Flight 77 descended toward the Pentagon it crossed the C-130's flight path. An air traffic controller asked the C-130 pilot, Lieutenant Colonel Steve O'Brien, to reverse course and follow the airliner. O'Brien turned and followed, watching in disbelief as Flight 77 smashed into the Pentagon. Ordered to leave the area immediately because fighter aircraft were approaching, the C-130 flew on to its destination - Minneapolis-St. Paul.20

Flight 77 hit the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m.* A description of the moment of impact on the building is contained in a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers - The Pentagon Building Performance Report:

The Boeing 757 approached the west wall of the Pentagon from the southwest at approximately 780 ft/s. As it approached the Pentagon site it was so low to the ground that it reportedly clipped an antenna on a vehicle on an adjacent road and severed light posts. When it was approximately 320 ft from the west wall of the building (0.42 second before impact), it was flying nearly level, only a few feet above the ground.... The aircraft flew over the grassy area next to the Pentagon until its right wing struck a piece of construction equipment that was approximately 100 to 110 ft from the face of the building (0.10 second before impact).... At that time the aircraft had rolled slightly to the left, its right wing elevated. After the plane had traveled approximately another 75 ft, the left engine struck the ground at nearly the same instant that the nose of the aircraft struck the west wall of the Pentagon.... Impact of the fuselage was ... at or slightly below the second-floor slab. The left wing passed below the second-floor slab, and the right wing crossed at a shallow angle from below the second-floor slab to above the second-floor slab.21

The impact proved devastating. The aircraft had taken off with a total weight of over 90 tons, roughly 25 percent of it in fuel. Allowing for the hour-and-a-quarter flight from Dulles Airport to Kentucky and back, Flight 77 still had most of its original 7,256 gallons of fuel on board, the greater part of it in the

_____________

* 9/11 Commission Report, 9, 25-27,461 (n 154), puts the time at 9:37:46.

--16--

wings, when it hit the Pentagon. Traveling at 530 m.p.h., the aircraft, and the subsequent fuel explosion, delivered enormous destructive power. The catastrophe might well have been even greater had the Pentagon been struck by either of the two Boeing 767s that crashed into the World Trade Center. These larger aircraft, carrying thousands of gallons more fuel than the Boeing 757s that departed from Newark and Dulles, would have done far more damage.*22

Flight 77 struck the west side of the Pentagon at the 1st Floor level just inside Wedge 1 near the 4th Corridor and proceeded diagonally at an approximate 42° angle toward the 5th Corridor in the mostly vacant and unrenovated Wedge 2. After the nose of the plane hit the Pentagon a huge fireball burst upward and rose 200 feet above the roof. Multiple explosions occurred as the plane smashed through the building. The front part of the relatively weak fuselage disintegrated, but the mid-section and tail-end continued moving for another fraction of a second, progressively destroying segments of the building further inward. The chain of destruction resulted in parts of the plane ending up inside the Pentagon in reverse of the order they had entered it, with the tail-end of the airliner penetrating the greatest distance into the building. Remarkably, these circumstances meant that the bodies of the passengers in the rear of the aircraft traveled deeper into the ground floor of the building than did those in the front. The largest concentration of body parts was found at the deepest area of penetration - the C Ring.23

While the immediate building interior area hit by the nose of the aircraft was small, the section subsequently wrecked by the large plane debris and multiple explosions of jet fuel from the ruptured tanks seconds after impact spanned a larger irregular area of more than an acre on each of the 1st and 2nd Floors. Office spaces and corridors on these floors accounted for the locations of all but two of the DoD victims. On the ground floor, the impact damage extended as

____________

* The Boeing two-engine 757-200 aircraft had a wingspan of 124 ft. 6 in., overall length of 155 ft. 3 in., and tail height of 44 ft. 6 in. According to American Airlines, Flight 77 carried "approximately 7,256 gallons of 'Jet A' fuel" on board when it departed Dulles (ltr D. Douglas Cotton, Legal Department, American Airlines, Inc. to Dalton West, OSD Historical Office, 24 Mar 06). According to the National Transportation Safety Board, Flight 77 carried 48,983 lbs. of fuel while on the ramp prior to departure and still had 36,200 lbs. of fuel on board when it hit the Pentagon. A standard conversion factor of 6.7+ lbs. per gallon of fuel yields the 7,256 gallons figure that American Airlines provided as above. See NTSB Office of Research and Engineering, "Study of Autopilot, Navigation Equipment, and Fuel Consumption Activity Based on United Airlines Flight 93 and American Airlines Flight 77 Digital Flight Data Recorder Information," John O'Callaghan and Daniel Bower, 13 Feb 02, 8.

--17--

--18--

far as the inner wall of the Pentagons C Ring adjoining A-E Drive, a depth of 210 feet, although the plane traveled about 270 feet along an angled path into the building. A-E Drive in Wedges 1 and 2 marked the C Ring back end of the 1st and 2nd Floor areas that suffered almost all of the fatalities. Impact damage on the 2nd Floor proved much more limited than on the 1st Floor, with no supporting columns destroyed at a distance more than 50 feet from the outside wall. Above the 2nd Floor most of the damage in the D and C Rings resulted from fire and smoke and collapsed ceilings and light fixtures.24

The velocity of the planes fuselage expended itself by the time it reached A-E Drive, which dissipated the remaining explosive energy of the crash. But the blast had enough force left to blow holes in the C Ring wall and force open the doors of an electrical vault opening into the drive; the openings proved the salvation of many survivors. Parts of the aircraft - including a tire part - hurtled through the outer three rings of Pentagon offices, emerged from a so-called "punch out" hole in the C Ring wall, and came to rest in A-E Drive. The planes voice recorder and flight data recorder were not recovered until several days later, 14 September.25

The report of the American Society of Civil Engineers concluded that "the direct impact of the aircraft destroyed the load capacity of about 30 first-floor columns and significantly impaired that of 20 others." Moreover, "this impact may have also destroyed the load capacity of about six second-floor columns adjacent to the exterior wall." Shattering the many columns essentially doubled the span between columns, thereby imposing severe stress on the stability of the affected building section and causing collapse of the four floors in the E Ring above the impact point at 10:15 a.m. The collapse started with the 2nd Floor just north of Corridor 4 along an expansion joint in the E Ring, and opened a hole to the outside about 95 feet wide at the 1st Floor level. The collapsed zone extended approximately 50 feet from the outside to the still-standing inside E Ring wall.*

___________

* Establishing an exact time for the collapse of the Pentagon's floors above the impacted E Ring area required extensive research. The "Arlington County After-Action Report" cited an incorrect time (9:57 a.m.) in its Appendix 1, page 1-1, seeming to confuse the warning of a collapse with the collapse itself: see A-29-30, A-66. Time-stamped video images provide the best evidence for 10:15 a.m. as the time of the collapse. See WUSA 9 News video, David Statter reporting from the Pentagon, 11 September 2001, 4100 Wisconsin Ave., Washington, D.C., and ABC News video "World Trade Center and Pentagon Bombings," 11 September 2001, 705204, Television News Archive, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. (local Nashville time), http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/tvn-month-search.pl. See also Rossow, Uncommon Strength, 83, n 1.

--19--

The D and C Rings did not collapse. The low hit reduced the damage visible from outside.26

No building could have absorbed the energy of such a crash without suffering structural damage and, if occupied, casualties. Nevertheless, the Pentagon fared better than less sturdy buildings would have. The greatest power of the interior explosions was confined to a limited area bounded by concrete floors and sturdy walls. Major structural damage ended with the collapse of the impact zone. Additional damage incurred over the next 36 hours extended deep into the Pentagon, with a considerably larger area beyond the impact site damaged by fire and smoke as well as the water from sprinklers, burst pipes, and fire hoses. The worst damage came from the volume and flammability of the fuel rather than the structural strength of the plane.

Although never designed to offer the protection of a bunker, the building's steel-reinforced concrete and brick construction protected most employees in Wedges 1 and 2 from fires and explosions and saved their lives. Moreover, the rigidity of the Pentagon's facade caused some of the fuel in the wings to detonate on impact, diminishing the inside destruction and probably reducing the number of dead - all 64 on board the plane and 125 from the building. The lighter structure and largely glass facade of the World Trade Center buildings presented much less impact resistance.27

In other respects, the structural strength of the building proved a mixed blessing. Concrete and brick, not yielding easily to the energy of the impact, channeled the ensuing explosion and flames along paths of less resistance. The new windows, frames, and walls in Wedge 1 held up under extraordinary pressures, but they diminished venting of the fires, heat, and smoke. Consequently the explosion's constrained energy coursed through offices, corridors, elevator shafts, and stairwells, where doors offered less resistance than concrete. The furious energy of the explosion made the bottom two floors in the immediate vicinity of the crash site death traps, compromised stairwells as escape routes, and made firefighting more difficult.

The delay in the collapse of the E Ring in Wedge 1, almost 40 minutes, proved critical to the survival of occupants of the upper three floors, where the immediate impact of the plane claimed only two lives, both on the 3rd Floor. The

--20--

--21--

Pentagon's sturdy construction served to delay the collapse, affording time for hundreds of people on the upper floors to escape.

The destruction and, more importantly, the loss of life, would have been worse without the reinforcement of the exterior wall of Wedge 1 and installation of the blast-resistant windows and fire suppression systems. Hitting just inside Corridor 4 in Wedge 1, the plane penetrated into the unrenovated Wedge 2. On 11 September the offices in or near the impact point were not completely occupied, either awaiting new tenants in Wedge 1 or mostly vacated in preparation for renovation in Wedge 2. Had the aircraft hit fully-occupied unrenovated Wedge 5, several hundred yards to the right, the toll of dead and injured, as well as structural damage, would have been much greater. If the plane had missed Wedge 1 entirely and plowed through only unrenovated and nearly-vacated portions of Wedge 2, the structural and fire damage would have been far greater, but the death toll might have been less. No matter where it might have struck the Pentagon, Flight 77 would have wreaked havoc.

--22--

Chapter II

The Deadly Strike

At 9:37 a.m. on 11 September the 20,000 people present in the Pentagon had no hint of the stunning explosion and firestorm about to engulf those in the path of the doomed airliner only seconds away from striking its target. A few of those witnessing the televised horror of the crashes into the World Trade Center's Twin Towers in New York did, indeed, wonder aloud if the Pentagon might be next. Their worst fears became reality when 34 minutes after United Flight 175 struck the South Tower of the World Trade Center at 9:03 a.m. American Flight 11 smashed into the west side of the Pentagon, bringing great damage to the building and death and injury to many of its inhabitants.

Despite the fortuitous circumstance that only 3,800 of the 4,500-5,000 intended occupants had moved into newly renovated Wedge 1 with its strengthened walls and windows and that Wedge 2 had been largely emptied of personnel (about 700 remained) as renovation began there, the exploding airliner exacted a heavy toll of dead and injured.1 Of the 125 Department of Defense fatalities in the Pentagon, 92 occurred on the 1st Floor, 31 on the 2nd Floor, and 2 on the 3rd Floor, all between Corridors 4 and 5. The dead included 70 civilians (10 of them contractor employees) and 55 military.* The Army incurred the greatest loss -

_____________

* There is evidence that one OSD contract employee, Allen Boyle, may have been outside the building just before the plane hit.

--23--

75 men and women.* Another 106 injured were taken to area hospitals.2 On the periphery of the damaged area many persons suffered from inhaling the dense and noxious smoke that engulfed a large part of the building on all five floors, reaching beyond the 2nd and 7th Corridors on either side and as far as the A Ring and even the Center Court on the lower floors.

On the airliner, all 64 people died, including the 5 hijackers, most of them instantly. Among the six crew members were a husband and wife pair of flight attendants. A party of eight from the Washington area - three teachers, three 11-year-old students, and two escorts from the National Geographic Society - had looked forward to a field trip to the Channel Island Marine Sanctuary in California. One of the children was the son of a Navy chief petty officer on duty in the Pentagon. A family of four, including two small children, and a honeymoon couple bound for Hawaii were among the victims. What befell two passengers - William Caswell and Bryan Jack - was especially ironic. Both were Department of Defense employees on official business trips and had offices in the Pentagon.†3

The attack killed 189 people, all of whom, with a few exceptions, died within minutes. Antoinette Sherman, an Army employee, died six days later in the hospital. Caswell and Jack on Flight 77 brought the total of DoD-affiliated fatalities in the Pentagon to 127.‡

A life-and-death drama for many hundreds of Pentagon occupants played out on the large stage between Corridors 4 and 5 and mostly on the 1st and 2nd Floors in Rings E, D, and C - an area of some two acres on each floor. Those floors contained numerous offices and hundreds of individual cubicles creating mazes awkward to negotiate even under normal conditions. The layout of the building and the drastically altered state of their surroundings caused by the crash dictated the escape routes taken by survivors. The main escape routes from the impact area to the outside of the building from the E Ring were Corridor 5 and the Heliport entrance midway between Corridors 4 and 5. In the opposite direction, Corridors 4 and 5 provided the chief exits through the A Ring to the Center Court. Some survivors from Wedge 2 managed to escape through blown

_____________

* For a complete list of fatalities see Appendix A.

† Still another DoD employee, Herbert Homer, was killed when the plane on which he was a passenger, American Airlines Flight 11, smashed into the World Trade Center.

‡ See Appendix A.

--24--

windows in the E Ring outer wall. On all floors and most rings a wooden construction barrier midway between Corridors 4 and 5, a temporary product of the renovation, often prevented people in Wedge 1 from reaching Corridor 5 and those in Wedge 2 from reaching Corridor 4.* In large measure, this particular obstacle determined routes taken by many of the survivors. Other main escape exits from the impact area were through Corridors 4 and 5 into A-E Drive from the C Ring. Three openings in the C Ring wall between Corridors 4 and 5, one of them the blown doors of the C-4 electrical vault, and a forced window at the 2nd Floor level proved the salvation of many survivors from the 1st and 2nd Floors. The holes into A-E Drive also made it possible for rescuers to enter the building and bring to safety lost and injured occupants who would otherwise have perished.

For people in the immediate vicinity of impact and along the path of destruction the first minutes brought surprise, disorientation, fear, panic, danger, and death. For those spared annihilation, the first minutes began a grim, desperate struggle for survival. In the menacing darkness and smoke, fear for their lives caused some to panic and cry out or scream; many prayed silently or aloud. Others, although frightened and expecting to die, did not panic and strove single-mindedly to find escape for themselves and their coworkers. Close to the crash, bewildered and shaken men and women, their thought and senses clouded by shock, had to function at whatever levels of instinct and willpower they retained. They faced a host of instant hazards: utter darkness, toxic smoke, fire, immense heat, piles of hot debris, collapsed ceilings and walls, live electric wires, blocked exits and stairways, and the beginning of a structural collapse within the critical zone. Hardly any knew or guessed what had precipitated the appalling chaos that had descended on them, even though most were aware of the crashes into the Twin Towers little more than half an hour earlier.

In sections of the building as much as two or three corridors removed from the Corridor 4 crash site, people could not help but notice the effect of the impact - variously described as a loud noise, a sudden shudder of the structure, an explosion, a concussion, the firing of large guns. Most of the occupants

___________

* The wooden construction barrier wall on all floors midway between Corridors 4 and 5 separated Wedge 1 from Wedge 2. Doors in most of the barrier walls permitted access to corridors on either side of a barrier, but they were often obscured by the smoke and most of the escapees from Wedge 2 turned toward Corridor 5.

--25--

in these areas departed in orderly fashion, some after encountering smoke and obstacles. A number stayed behind to help rescue others. Army Major Craig Collier recalled that he and his colleagues remained in their office, 2C638, after the plane hit:

Moments later the building jolted and we heard a muffled boom, then a rumble. Some loose plaster and dust fell from the ceiling, but otherwise there was no other indication of what had just taken place about 200 feet away. All of my peers in the area are experienced combat arms officers, and we quickly agreed that it sounded and felt like a bomb. Most of us stayed in place watching the news and waiting for more information as one or two officers walked out into the hallway to see what was going on. Remarkably, my boss walked in and asked us what was happening. He had been in the latrine next door and hadn't felt or heard a thing. Within about 2 minutes the TV banner below the video of the burning towers changed from "World Trade Center" to "Pentagon," but before I could hear any of the details the word came to evacuate the building. Two of our female civilian secretaries bolted out of the office but the rest of us took the time to calmly turn off computers, call our wives, grab our bags, and exit.4

Away from the impact area, 1,000 and more feet removed, many occupants had no inkling that an attack had occurred and felt little or no immediate effect. They heard the fire alarms, smelled smoke, and heeded instructions from the Defense Protective Service (DPS) to leave the building. Unlike the skyscraping World Trade Center, the low-lying Pentagons numerous exits to the outside and to the Center Court facilitated rapid evacuation; for most of the 20,000 inhabitants the evacuation proved orderly. Once outside the Pentagon no one could miss the immense column of smoke rising from the crash site.

During the renovation sophisticated fire alarm and sprinkler systems had been installed in Wedge 1. These operated initially after the attack, but many were soon damaged or destroyed and ceased to work. Surviving sprinklers helped limit the spread of the fire and toxic smoke and provided survivors much needed relief from the great heat. The older alarm systems in the rest of the building had false alarm and other functional failures. These systems included an automated recorded message giving instructions to evacuate. A backup public address system, called "Big Voice," complemented the automatic announcements by indicating the best escape route. Unfortunately the systems performed poorly. In

--26--

some sections of the building workers heard no alarm at all or received a garbled announcement. In Wedge 2 there were no sprinklers.5

Many occupants in the newly renovated Wedge 1 on the 1st and 2nd Floors were not yet fully familiar with their new quarters. In windowless, blacked out, and smoke-filled areas, disoriented, they had difficulty knowing where to turn to find exits leading to safety. Even occupants of Wedge 2, more familiar with their surroundings, found themselves at a loss in the smoke and darkness.

Knowledge of what happened to the hundreds of people in Wedges 1 and 2 and nearby areas most immediately affected by the explosion and fire comes from an abundance of eyewitness testimony and forensic evidence. The accounts of death and survival that follow are representative of the range of experiences endured by most of those unfortunate enough to find themselves in or near the path of the exploding airliner.

Among those who actually saw Flight 77 hit the building, perhaps closest to the crash site were Air Traffic Controllers Sean Boger and Army Specialist Jacqueline Kidd, in the air traffic control tower between the building and the Pentagon Heliport, from where they directed helicopter landings and departures. On hearing the news of the crashes in New York, Boger wondered aloud, as he had on other occasions, why no airliner had ever accidentally hit the Pentagon, given its close proximity (approximately a mile) to Reagan National Airport. Moments later, after Kidd had gone downstairs to the restroom, Boger, looking out the window, saw "the nose and the wing of an aircraft just like coming right at us, and he didn't veer,... I am watching the plane go all the way into the building." He stared as the Boeing 757 "smacked into the building" less than 100 feet away.

When the plane exploded into the Pentagon, Boger "hit the floor and just covered up" his head because he was "surrounded by glass." As the towers alarms sounded and emergency lights flashed, he rose, yanked open the control room door, and plunged down the stairs, jumping steps to avoid a clutter of ceiling tiles, light fixtures, and broken stair railings. On the ground floor he met Specialist Kidd, and the two ran from the scene. About 25 yards distant they fell to the ground and turned to look at the conflagration that had set on fire their cars, parked next to the tower.6 Inside the building, others in the path of the plane did not have the opportunity to run.

--27--

First Floor

On the 1st Floor of the E Ring and part of the D Ring, directly in the path of the oncoming airliner, the U.S. Army's Resource Services - Washington (RSW) office, part of the Office of the Administrative Assistant to the Secretary of the Army, employing 65 to 70 people, managed money and personnel for the headquarters staff. By 11 September two RSW divisions had moved from their older, unrenovated offices to their new 1E400 area workplace. However, the RSW director, longtime government employee Robert Jaworski, and many of his people from the personnel, financial management, and accounting staffs, had not yet moved into their new spaces and were still working in the D Ring, Corridors 6 and 7 area, 500 feet or more removed from their colleagues.

In his 3D735 office Jaworski heard radio broadcasts of the World Trade Center attacks. After the second airliner hit, Jaworski and his staff realized the crashes were terrorist attacks; he remarked to one staff member visiting from the new E Ring office that the Pentagon would be a likely target. Seconds later Jaworski heard the building shake and the sound of shattering glass - instant, staggering confirmation of his speculation. He and his nearby colleagues got up from their desks, moved quickly down Corridor 7 to the A Ring, then to Corridor 9, down the ramp into the Concourse, and out an exit leading to South Parking.

For the RSW staff in the E Ring, location determined their fate. Jaworski later observed sorrowfully that "they didn't have a chance." Just two occupants of one office along the inner side of that part of the E Ring survived, only because they had stepped out to the restroom moments before the airliner slammed into the building. None of their immediate office mates escaped. RSWs Program and Budget Division, hit especially hard, lost 25 of its 28 members. Across the E Ring hallway, along the outside wall of the building, the jet's impact proved almost as lethal. Of the Managerial Accounting Division's 12 members present, only 3 survived. For these three the fireball and partial collapse of a wall almost proved their undoing; not one escaped without injury. All told, 34 of the 40 members of the Program and Budget and Managerial Accounting Divisions present that morning perished.7

Among the six who survived, Sheila Moody was one of the luckiest. Seated at her desk in 1E472, she heard a "whistling sound.... And then there was a rumble, and a large gush of air and a fireball that came into the office and

--28--

just blew everything all over the place and knocked us over." Trapped in "a lot of smoke and just darkness," she could not see that the hole blown in the outer E Ring wall was only a few feet away. Then, in the silence that had descended, she heard the working of a fire extinguisher and a voice calling out. She called back but "then the smoke and the fumes started taking my breath away, and I couldn't really call out to him. So I started clapping my hands." Her rescuer, Staff Sergeant Chris Brahman, extinguished the flames between them and led her to the outside. Moody was hospitalized for burns to her hands that proved worse than she initially realized.8

Two other survivors from the RSW offices, Juan Cruz Santiago and Louise Kurtz, were less fortunate than Sheila Moody. When the plane hit, Cruz was thrown to his knees and engulfed by fire. Most of his body was scorched with second-, third-, and fourth-degree burns. Reduced to a state of semiconsciousness, he became aware of water being poured over him and he vaguely perceived someone carrying him out of the building. As the initial shock wore off he experienced excruciating pain. Hospitalized for three months, Cruz underwent nearly 30 surgical procedures, including skin grafts to his face, right arm, hands, and legs. He was left with cruel damage to his face, eyes, and hands.9

Louise Kurtz was standing at a fax machine in her RSW office when, she later recalled, she was "baked, totally.... I was like meat when you take it off the grill." In spite of her pain and shock she managed to crawl on top of a table and through a window to the outside of the E Ring. She lapsed into unconsciousness in an ambulance and woke up in the hospital; doctors gave her a 50 percent chance of survival. After more than three months she left the hospital without her fingers and her ears, with multiple skin grafts, and with other severe disabilities.10

Another Army office under the administrative assistant to the secretary of the Army, the Information Management Support Center (IMCEN) on the 1st Floor, suffered six fatalities. Room 1E460 lay in the direct path of the airliner; its three occupants - Michael Selves, Lieutenant Colonel Dean Mattson, and John Chada - perished. Three other IMCEN employees - Teddington Moy, Robert Maxwell, and Scott Powell, a contractor - died at other locations occupied by IMCEN in the E Ring.11

--29--

More fortunate than her six fellow IMCEN employees was Specialist April Gallop, in Room 1E517 in Wedge 2. On 11 September she brought her two-month-old son Elisha to work with her because her babysitter had been hospitalized. With Elisha in a stroller alongside her desk, Gallop sat in front of a computer. "And as soon as I was about to turn the computer on, boom ... the computer blew." The walls and ceiling crumbled, and she found herself covered in debris up to her waist. Frantically looking for her son in the smoke-darkened room, with flames providing the only light, she saw that the stroller was on fire but empty. Freeing herself from the debris, Gallop searched desperately for her baby and found him covered up in the litter."He's in a ball, like that.... So I was thinking, oh, my God, his bones are broken."

Two of Gallop's office mates, Corporal Eduardo Bruno and Sergeant Roxanne Cruz-Cortez, soon came to her aid after freeing themselves from the rubble that had trapped them for a few minutes. They helped her climb over the half-demolished office wall and passed the baby from hand to hand as they moved toward an outside window in the E Ring that led to safety. Followed by perhaps as many as 10 civilian workers, Bruno and Cruz-Cortez reached the window. Cruz-Cortez pushed and pulled two hysterical women to the window. The baby was passed outside and the others followed, dropping one by one. Bruno, although injured and later hospitalized, helped catch people dropping from the window. Once on the outside Gallop lost consciousness. When she awoke in George Washington University Hospital she called for her baby. Fortunately he had survived without serious injury.12

Beyond the Army offices in Wedge 1, the newly opened Navy Command Center (NCC) occupied a much larger space than the RSW offices between Corridor 4 and the wooden barrier midway between Corridors 4 and 5. Including much of the D Ring and all of the C Ring, bridging the light well between the D and C Rings, the center's area exceeded a third of an acre.

The Command Center tracked movements of U.S. Navy vessels and aircraft and monitored significant international events, keeping the chief of naval operations and other senior Navy leaders informed of important developments. The Watch Floor, focal point of the NCC, was staffed 24 hours a day. Seven other offices shared the center's spaces with the Watch Floor. Five-foot-high movable partitions separated most of the office cubicles. For meetings,

--30--

including daily briefings during the workweek, a theater and conference room provided larger spaces. Between 50 and 70 people were normally on duty during a workday. Although its near end was some 80 feet from the outer wall of the Pentagon, the NCC had no real protection from the exploding airplane. In a matter of seconds it became an inferno of explosion, fires, and tangled wreckage that killed or injured most of the occupants.13

At work in the Meteorology and Oceanography section of the center on 11 September were the officer in charge and two petty officers. Early that morning, Lieutenant Nancy McKeown, a former chief petty officer, gave a briefing on global weather patterns. After completing the morning briefing, McKeown returned to her office, where she and her two aerographers, Petty Officers Edward Earhart and Matthew Flocco, watched as United Airlines Flight 175 struck the South Tower in New York City. Soon after, McKeown returned to her own cubicle nearby and sat down. Almost immediately she heard a roaring crescendo of sound as ceiling tiles came down and she fell from her chair. It felt like an earthquake (she had experienced quakes in Japan) and the roar became louder. McKeown yelled "Bomb!" and dived under her desk; the office plunged into darkness and began to fill with smoke. Within moments the thunderous din subsided, the smoke thickened, and she emerged from her now "deathly quiet" office calling out for her two petty officers; there was no response. Only flickering lights overhead illuminated the "pitch black" space.

Disoriented, McKeown walked the wrong way, toward the path the jet had taken through the building. Feeling the wall growing hotter, seeing visibility dropping further, and finding breathing more difficult, McKeown turned around and headed back toward her office, stopping momentarily under the spray of a broken sprinkler line to ward off the intense heat. On spying a small bright spot in the distance she moved toward it, eventually recognizing the glass doors at the 4th Corridor entrance to the Command Center. Although the dense smoke choked her, she somehow succeeded in gaining the attention of two rescuers who took her into Corridor 4 and sat her down. Sputtering, McKeown told them that "we had to go back in and get my two guys." She thought that one of the nearby rescuers headed back into the center. As she awaited further assistance McKeown "could hear people yelling,'Don't jump! Don't jump!'" Looking up, she could "see ... silhouettes falling from the second floor down. I don't know if they were

--31--

jumping or falling.... All I could actually see was the silhouettes coming down and ... people kind of reaching up trying to grab people as they were coming down." After reaching a triage center in North Parking, McKeown was transported by ambulance to the nearby Arlington Urgent Care Center where she was treated for smoke inhalation. Unfortunately, Petty Officers Earhart and Flocco did not survive.14

Another junior officer in the Command Center, Lieutenant Kevin Shaeffer, a 1994 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy who worked in the Strategy and Concepts office, also watched the attacks on the Twin Towers on the center's large-screen television sets. Shaken, Shaeffer returned to his cubicle, where he stood and continued to watch over the tops of the partitions. Suddenly the walls "exploded," and "the next moment was just a gigantic fireball with obviously a ton of force coming through the space." A "huge flash of fire" erupted with such force it blew him to the floor.

Despite suffering grievous injuries Shaeffer never lost consciousness and his actions remained purposeful. Realizing that his hair and skin were on fire, he rolled around on the floor to put out the flames. In those same few seconds he wiped his hands through his hair, and found it charred. When he managed to stand up, smoke-filled air increasingly irritated his mouth and throat and limited what he could see. As far as he could tell, no one around him remained alive. Aware that he was badly hurt, and neither hearing nor seeing anyone, he began looking for a way out. Judging that the explosion had come from the E Ring, he crawled in the opposite direction.

Piles of blown-down light fixtures, ceiling tiles, duct work, wiring, and cubicle furniture made the going difficult, and Shaeffer resorted to crawling under and over these heaps, cutting his badly burned hands. Following a zigzag path he worked his way towards the back of the Command Center, where he saw a dim light ahead. Gasping from the choking smoke, he crawled through rubble, scaled more piles of wreckage, and finally staggered out into A-E Drive through a hole blown in the C Ring wall. Later, he reckoned it had taken about five minutes to crawl the roughly 70 feet to A-E Drive.

After receiving on-the-spot first aid, Shaeffer was transported to the DiLorenzo Clinic in the 8th Corridor, from where he was carried outside on an electric cart and taken by ambulance to Walter Reed Army Medical Center. His

--32--

burns were so severe (over 42 percent of his body) that he was transferred to the Washington Hospital Center where he underwent many weeks of painful treatment in the intensive care unit. After an ordeal of more than three months he was able to leave the hospital. Having suffered permanent damage to his lungs and to the right side of his body, Lieutenant Shaeffer was retired on medical disability.15

In the Intelligence Plot section, tucked into a corner of the Command Center in the C Ring, 13 people were present on the morning of 11 September. This area was a SCIF (Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility), a highly secured space containing especially sensitive classified materials. It lay almost 200 feet from the outer E Ring wall of the Pentagon and along the course taken by Flight 77. The officer in charge, Commander Dan Shanower, and six coworkers had completed briefing Deputy Director of Naval Intelligence Susan Long and members of her staff about 20 or 30 minutes before the impact. Also in the Intelligence Plot that morning were six others: Lieutenant Commander Charles Capets, using a computer on the Watch Floor alongside Lieutenant Megan Humbert and Petty Officer of the Watch Jason Lhuillier, while Petty Officers Steven Gully and Jesse Polasek and Seaman Sarah Cole worked in the adjoining Graphics space.16

Lhuillier interrupted a meeting in Shanower's office to report the second World Trade Center strike. A few minutes later, after returning to his desk, Lhuillier heard a "Kaboom," and was thrown to the floor and under an adjacent desk. Within seconds of the impact, as the fire intensified and the smoke thickened, Lhuillier began to have difficulty breathing. Capets, visiting the Intelligence Plot from his office on the 5th Floor, was present when the Watch Officer received information that a hijacked aircraft was headed toward Washington. Thinking that his boss should know, he picked up the phone to call when "this thing hit." Like Lhuillier he was flung to the floor of the wrecked office and experienced the fire, heat, smoke, and darkness. After initial confusion and failed efforts to find an exit, Capets saw the beckoning light from a hole blown open in the C Ring office wall to A-E Drive and crawled toward it. Finding the office door jammed shut by the explosion, Lhuillier followed Capets, scrambled over a barricade of office equipment, and escaped with him through the same large hole. The two turned back to pull Humbert to safety through a pile of debris. Capets and Lhuillier assisted in frantic rescue efforts that helped survivors get out of the building into

--33--

A-E Drive.17 For Shanower and his briefing team there was no escape. The rapid spread of the fire and the deadly smoke quickly killed all of them.