The Navy Department Library

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans

Background and Issues for Congress

Congressional

Research Service

Informing the legislative debate since 1914

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans:

Background and Issues for Congress

Ronald O'Rourke

Specialist in Naval Affairs

January 8, 2016

Congressional Research Service

7-5700

www.crs.gov

RL32665

CRS REPORT

Prepared for Members and

Committees of Congress

Contents

| Introduction | 1 |

| Background | 1 |

| Strategic and Budgetary Context | 1 |

| Shift in International Security Environment | 1 |

| Declining U.S. Technological and Qualitative Edge | 2 |

| Challenge to U.S. Sea Control and U.S. Position in Western Pacific | 2 |

| U.S. Grand Strategy | 2 |

| U.S. Strategic Rebalancing to Asia-Pacific Region | 3 |

| Continued Operations in Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean | 3 |

| Potential Increased Demand for U.S. Naval Forces Around Europe | 4 |

| Longer Ship Deployments | 4 |

| Limits on Defense Spending in Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended | 4 |

| Navy’s Ship Force Structure Goal | 5 |

| March 2015 Goal for Fleet of 308 Ships | 5 |

| Goal for Fleet of 308 Ships Compared to Earlier Goals | 5 |

| Navy’s Five-Year and 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans | 7 |

| Five-Year (FY2016-FY2020) Shipbuilding Plan | 7 |

| 30-Year (FY2016-FY2045) Shipbuilding Plan | 8 |

| Navy’s Projected Force Levels Under 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan | 9 |

| Comparison of First 10 Years of 30-Year Plans | 11 |

| Oversight Issues for Congress for FY2016 | 16 |

| Potential Impact on Size and Capability of Navy of Limiting DOD Spending to BCA | |

| Caps Through FY2021 | 16 |

| January 2015 Navy Testimony | 16 |

| March 2015 Navy Report | 20 |

| Affordability of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan | 21 |

| Estimated Ship Procurement Costs | 21 |

| Future Shipbuilding Funding Levels | 22 |

| Appropriate Future Size and Structure of Navy in Light of Strategic and Budgetary Changes | 23 |

| Overview | 23 |

| Proposals by Study Groups | 24 |

| Fleet Architecture | 26 |

| Potential Oversight Questions | 30 |

| Legislative Activity for FY2016 | 31 |

| FY2016 Funding Request | 31 |

| CRS Reports Tracking Legislation on Specific Navy Shipbuilding Programs | 31 |

| FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1735/S. 1376) | 32 |

| House | 32 |

| Senate | 33 |

| Conference (Version Vetoed) | 38 |

| FY2016 DOD Appropriations Act (H.R. 2685/S. 1558/H.R. 2029) | 43 |

| House | 43 |

| Senate | 43 |

| Conference | 46 |

Figures

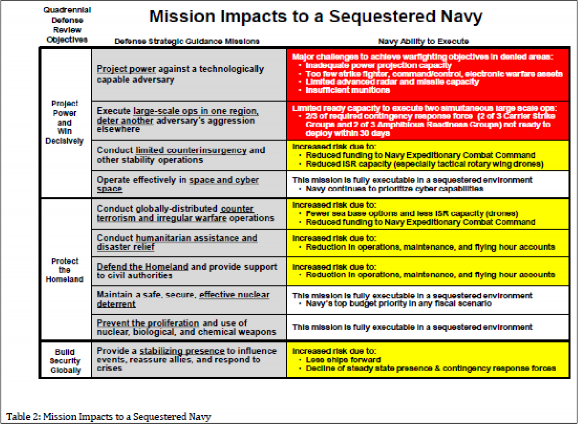

| Figure 1. Navy Table on Mission Impacts of Limiting Navy’s Budget to BC Levels | 20 |

Tables

| Table 1. Current 308 Ship Force Structure Goal Compared to Earlier Goals6 | |

| Table 2. Navy FY2016 Five-Year (FY2016-FY2020) Shipbuilding Plan | 7 |

| Table 3. Navy FY2016 30-Year (FY2016-FY2045) Shipbuilding Plan | 9 |

| Table 4. Projected Force Levels Resulting from FY2016 30-Year (FY2016-FY2045) Shipbuilding Plan | 10 |

| Table 5. Ship Procurement Quantities in First 10 Years of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans | 12 |

| Table 6. Projected Navy Force Sizes in First 10 years of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans | 14 |

| Table 7. Navy and CBO Estimates of Cost of FY2016 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan | 22 |

| Table 8. Recent Study Group Proposals for Navy Ship Force Structure | 25 |

| Table B-1. Comparison of Navy’s 308-ship goal, Navy Plan from 1993 BUR, and Navy Plan from 2010 QDR Review Panel | 52 |

| Table D-1. Total Number of Ships in the Navy Since FY1948 | 57 |

| Table D-2. Battle Force Ships Procured or Requested/Programmed, FY1982-FY2020 | 58 |

Appendixes

| Appendix A. Comparing Past Ship Force Levels to Current or Potential Future Ship Force Levels | 48 |

| Appendix B. Independent Panel Assessment of 2010 QDR | 50 |

| Appendix C. U.S. Strategy and the Size and Structure of U.S. Naval Forces | 54 |

| Appendix D. Size of the Navy and Navy Shipbuilding Rate | 56 |

Contacts

| Author Contact Information | 58 |

Summary

The Navy’s proposed FY2016 budget requests funding for the procurement of nine new battle force ships (i.e., ships that count against the Navy’s goal for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 308 ships). The nine ships include two Virginia-class attack submarines, two DDG-51 class Aegis destroyers, three Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs), one LPD-17 class amphibious ship, and one

TAO-205 class (previously known as TAO[X] class) oiler. The Navy’s proposed FY2016-FY2020 five-year shipbuilding plan includes a total of 48 ships, compared to a total of 44 ships in the FY2015-FY2019 five-year shipbuilding plan.

The planned size of the Navy, the rate of Navy ship procurement, and the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been matters of concern for the congressional defense committees for the past several years. The Navy’s FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan, like many previous Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans, does not include enough ships to fully support all elements of the Navy’s 308-ship goal over the entire 30-year period. In particular, the Navy projects that the fleet would experience a shortfall in small surface

combatants from FY2016 through FY2027, a shortfall in attack submarines from FY2025 through FY2036, and a shortfall in large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers) from FY2036 through at least FY2045.

The Navy’s report on its FY2016 30-year shipbuilding plan estimates that the plan would cost an average of about $16.5 billion per year in constant FY2015 dollars to implement, including an average of about $16.9 billion per year during the first 10 years of the plan, an average of about

$17.2 billion per year during the middle 10 years of the plan, and an average of about $15.2 billion per year during the final 10 years of the plan.

An October 2015 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the Navy’s FY2015 30-year shipbuilding plan estimates that the plan would require 11.5% more funding to implement than the Navy estimates, including 7.7% more than the Navy estimates during the first 10 years of the plan, 11.6% more than the Navy estimates during the middle 10 years of the plan, and 17.1% more than the Navy estimates during the final 10 years of the plan. Over the years, CBO’s estimates of the cost to implement the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan have generally been higher than the Navy’s estimates. Some of the difference between CBO’s estimates and the Navy’s estimates, particularly in the latter years of the plan, is due to a difference between CBO and the Navy in how to treat inflation in Navy shipbuilding. The program that contributes the most to the difference between the CBO and Navy estimates of the cost of the 30-year plan is a future destroyer that appears in the latter years of the 30-year plan.

Potential issues for Congress in reviewing the Navy’s proposed FY2016 shipbuilding budget, its proposed FY2016-FY2020 five-year shipbuilding plan, and its FY2016 30-year (FY2015- FY2045) shipbuilding plan include the following:

the potential impact on the size and capability of the Navy of limiting Department of Defense (DOD) spending through FY2021 to the levels set forth in the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011, as amended;

the affordability of the 30-year shipbuilding plan; and

the appropriate future size and structure of the Navy in light of budgetary and strategic considerations.

Funding levels and legislative activity on individual Navy shipbuilding programs are tracked in detail in other CRS reports.

Introduction

This report presents background information and issues for Congress concerning the Navy’s ship force-structure goals and shipbuilding plans. The planned size of the Navy, the rate of Navy ship procurement, and the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been matters of concern for the congressional defense committees for the past several years. Decisions that Congress makes on Navy shipbuilding programs can substantially affect Navy capabilities and funding requirements, and the U.S. shipbuilding industrial base.

Detailed coverage of certain individual Navy shipbuilding programs can be found in the following CRS reports:

CRS Report RS20643, Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R41129, Navy Ohio Replacement (SSBN[X]) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL32418, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL32109, Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report RL33741, Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS)/Frigate Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

CRS Report R43543, Navy LX(R) Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke. (This report also covers the issue of procurement of a 12th LPD-17 class amphibious ship.)

CRS Report R43546, Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Background

Strategic and Budgetary Context

This section presents some brief comments on elements of the strategic and budgetary context in which U.S. Navy force structure and shipbuilding plans may be considered.

Shift in International Security Environment

World events since late 2013 have led some observers to conclude that the international security environment has undergone a shift from the familiar post-Cold War era of the past 20-25 years, also sometimes known as the unipolar moment (with the United States as the unipolar power), to a new and different strategic situation that features, among other things, renewed great power competition and challenges to elements of the U.S.-led international order that has operated since World War II. This situation is discussed further in another CRS report.1

___________

1 CRS Report R43838, A Shift in the International Security Environment: Potential Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Declining U.S. Technological and Qualitative Edge

Department of Defense (DOD) officials have expressed concern that the technological and qualitative edge that U.S. military forces have had relative to the military forces of other countries is being narrowed by improving military capabilities in other countries. China’s improving naval capabilities contribute to that concern.2 To arrest and reverse the decline in the U.S. technological and qualitative edge, DOD in November 2014 announced a new Defense Innovation Initiative.3

In a related effort, DOD has also announced that it is seeking a new general U.S. approach—a so- called “third offset strategy”—for maintaining U.S. superiority over opposing military forces that are both numerically large and armed with precision-guided weapons.4

Challenge to U.S. Sea Control and U.S. Position in Western Pacific

Observers of Chinese and U.S. military forces view China’s improving naval capabilities as posing a potential challenge in the Western Pacific to the U.S. Navy’s ability to achieve and maintain control of blue-water ocean areas in wartime—the first such challenge the U.S. Navy has faced since the end of the Cold War.5 More broadly, these observers view China’s naval capabilities as a key element of an emerging broader Chinese military challenge to the longstanding status of the United States as the leading military power in the Western Pacific.

U.S. Grand Strategy

Discussion of the above-mentioned shift in the international security environment has led to a renewed emphasis in discussions of U.S. security and foreign policy on grand strategy and

___________

2 For more on China’s naval modernization effort, see CRS Report RL33153, China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

3 See, for example, Cheryl Pellerin, “Hagel Announces New Defense Innovation, Reform Efforts,” DOD News, November 15, 2014; Jake Richmond, “Work Explains Strategy Behind Innovation Initiative,” DOD News, November 24, 2014; and memorandum dated November 15, 2015, from Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel to the Deputy Secretary of Defense and other DOD recipients on The Defense Innovation Initiative, accessed online on July 21, 2015, at http://www.defense.gov/pubs/OSD013411-14.pdf.

4 See, for example, Jake Richmond, “Work Explains Strategy Behind Innovation Initiative,” DOD News, November 24, 2014; Claudette Roulo, “Offset Strategy Puts Advantage in Hands of U.S., Allies,” DOD News, January 28, 2015; Cheryl Pellerin, “Work Details the Future of War at Army Defense College,” DOD News, April 8, 2015.

See also Deputy Secretary of Defense Speech, National Defense University Convocation, As Prepared for Delivery by Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work, National Defense University, August 05, 2014, accessed July 21, 2015, at http://www.defense.gov/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1873; Deputy Secretary of Defense Speech, The Third U.S. Offset Strategy and its Implications for Partners and Allies, As Delivered by Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work, Willard Hotel, January 28, 2015, accessed July 21, 2015, at http://www.defense.gov/speeches/speech.aspx?speechid=1909; Deputy Secretary of Defense Speech, Army War College Strategy Conference, As Delivered by Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work, U.S. Army War College, April 08, 2015, accessed July 21, 2015, at http://www.defense.gov/Speeches/Speech.aspx?SpeechID=1930.

The effort is referred to as the search for a third offset strategy because it would succeed a 1950s-1960s U.S. strategy of relying on nuclear weapons to offset the Soviet Union’s numerical superiority in conventional military forces (the first offset strategy) and a subsequent U.S. offset strategy, first developed and fielded in the 1970s and 1980s, that centered on information technology and precision-guided weapons (the second offset strategy). (For more on the second offset strategy, see DOD News Release No: 567-96, October 3, 1996, “Remarks as Given by Secretary of Defense William J. Perry To the National Academy of Engineering, Wednesday, October 2, 1996,” accessed July 21, 2015, at http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=1057.)

5 The term “blue-water ocean areas” is used here to mean waters that are away from shore, as opposed to near-shore (i.e., littoral) waters. Iran is viewed as posing a challenge to the U.S. Navy’s ability to quickly achieve and maintain sea control in littoral waters in and near the Strait of Hormuz. For additional discussion, see CRS Report R42335, Iran’s Threat to the Strait of Hormuz, coordinated by Kenneth Katzman.

geopolitics. From a U.S. perspective, grand strategy can be understood as strategy considered at a global or interregional level, as opposed to strategies for specific countries, regions, or issues. Geopolitics refers to the influence on international relations and strategy of basic world geographic features such as the size and location of continents, oceans, and individual countries.

From a U.S. perspective on grand strategy and geopolitics, it can be noted that most of the world’s people, resources, and economic activity are located not in the Western Hemisphere, but in the other hemisphere, particularly Eurasia. In response to this basic feature of world geography, U.S. policymakers for the past several decades have chosen to pursue, as a key element of U.S. national strategy, a goal of preventing the emergence of a regional hegemon in one part of Eurasia or another, on the grounds that such a hegemon could represent a concentration of power strong enough to threaten core U.S. interests by, for example, denying the United States access to some of the other hemisphere’s resources and economic activity. Although U.S. policymakers have not often stated this key national strategic goal explicitly in public, U.S. military (and diplomatic) operations in recent decades—both wartime operations and day-to-day operations—can be viewed as having been carried out in no small part in support of this key goal.

The U.S. goal of preventing the emergence of a regional hegemon in one part of Eurasia or another is a major reason why the U.S. military is structured with force elements that enable it to cross broad expanses of ocean and air space and then conduct sustained, large-scale military operations upon arrival. Force elements associated with this goal include, among other things, an Air Force with significant numbers of long-range bombers, long-range surveillance aircraft, long- range airlift aircraft, and aerial refueling tankers, and a Navy with significant numbers aircraft carriers, nuclear-powered attack submarines, large surface combatants, large amphibious ships, and underway replenishment ships. For additional discussion, see Appendix C.

U.S. Strategic Rebalancing to Asia-Pacific Region

For decades, the Western Pacific has been a major operational area (i.e., operational “hub”) for forward-deployed U.S. Navy forces. In coming years, the importance of the Western Pacific as an operational hub for forward-deployed U.S. Navy forces may grow further: A 2012 DOD strategic guidance document6 and DOD’s report on the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR)7 state that U.S. military strategy will place an increased emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region (meaning, for the U.S. Navy, the Western Pacific in particular). Although Administration officials state that this U.S. strategic rebalancing toward the Asia-Pacific region, as it is called, is not directed at any single country, many observers believe it is in no small part intended as a response to China’s military (including naval) modernization effort and its assertive behavior regarding its maritime territorial claims. As one reflection of the U.S. strategic rebalancing to the Asia-Pacific region, Navy plans call for increasing over time the number of U.S. Navy ships that are deployed to the region on a day-to-day basis.

Continued Operations in Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean

In announcing the U.S. strategic rebalancing to the Asia-Pacific region, DOD officials noted that the United States would continue to maintain a forward-deployed military presence in the Middle

___________

6 Department of Defense, Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, January 2012, 8 pp. For additional discussion, see CRS Report R42146, Assessing the January 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG): In Brief, by Catherine Dale and Pat Towell.

7 Department of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review 2014, 64 pp. For additional discussion, see CRS Report R43403, The 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and Defense Strategy: Issues for Congress, by Catherine Dale.

East (meaning, for the U.S. Navy, primarily the Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean region). U.S. military operations to counter the Islamic State organization and other terrorist organizations in the Middle East are reinforcing demands for forward-deploying U.S. military forces, including U.S. naval forces, to that region.

Potential Increased Demand for U.S. Naval Forces Around Europe

During the Cold War, the Mediterranean was one of three major operational hubs for forward- deployed U.S. Navy forces (along with the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean region). Following the end of the Cold War, the Mediterranean was deemphasized as an operating hub for forward-deployed U.S. Navy forces. This situation might be changing once again: Russia’s seizure and annexation of Crimea in March 2014, Russia’s actions in Eastern Ukraine, operations by Russian military forces around the periphery of Europe and in the Arctic, and developments in North Africa and Syria are once again focusing U.S. policymaker attention on U.S. military operations in Europe and its surrounding waters, and in the Arctic (meaning, for the U.S. Navy, potentially increased operations in the Mediterranean and perhaps the Norwegian Sea and the Arctic).

Longer Ship Deployments

U.S. Navy officials have testified that fully meeting requests from U.S. regional combatant commanders (COCOMs) for forward-deployed U.S. naval forces would require a Navy much larger than today’s fleet. For example, Navy officials testified in March 2014 that a Navy of 450 ships would be required to fully meet COCOM requests for forward-deployed Navy forces.8 COCOM requests for forward-deployed U.S. Navy forces are adjudicated by DOD through a process called the Global Force Management Allocation Plan. The process essentially makes choices about how to best to apportion a finite number forward-deployed U.S. Navy ships among competing COCOM requests for those ships. Even with this process, the Navy has lengthened the deployments of some ships in an attempt to meet policymaker demands for forward-deployed U.S. Navy ships. Although Navy officials are aiming to limit ship deployments to seven months, Navy ships in recent years have frequently been deployed for periods of eight months or more.

Limits on Defense Spending in Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended

Limits on the “base” portion of the U.S. defense budget established by Budget Control Act of 2011, or BCA (S. 365/P.L. 112-25 of August 2, 2011), as amended, combined with some of the considerations above, have led to discussions among observers about how to balance competing demands for finite U.S. defense funds, and about whether programs for responding to China’s military modernization effort can be adequately funded while also adequately funding other defense-spending priorities, such as initiatives for responding to Russia’s actions in Ukraine and elsewhere in Europe and U.S. operations for countering the Islamic State organization in the Middle East. U.S. Navy officials have stated that if defense spending remains constrained to

levels set forth in the BCA as amended, the Navy in coming years will not be able to fully execute all the missions assigned to it under the 2012 DOD strategic guidance document.9

____________

8 Spoken testimony of Admiral Jonathan Greenert at a March 12, 2014, hearing before the House Armed Services Committee on the Department of the Navy’s proposed FY2015 budget, as shown in transcript of hearing.

9 See, for example, Statement of Admiral Jonathan Greenert, U.S. navy, Chief of Naval Operations, Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Impact of Sequestration on National Defense, January 28, 2015, particularly page 4 and Table 1, entitled “Mission Impacts to a Sequestered Navy.”

Navy’s Ship Force Structure Goal

March 2015 Goal for Fleet of 308 Ships

On March 17, 2015, in response to language in H.Rept. 113-446 (the House Armed Services Committee’s report on H.R. 4435, the FY2015 National Defense Authorization Act),10 the Navy submitted to Congress a report presenting a goal for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 308 ships, consisting of certain types and quantities of ships.11 The goal for a 308-ship fleet is the result of a force structure assessment (FSA) that the Navy completed in 2014. The 2014 FSA and the resulting 308-ship plan reflect the defense strategic guidance document that the Administration presented in January 201212 and 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). The Navy states that 308-ship fleet is designed to meet the projected needs of the Navy in the 2020s.

Goal for Fleet of 308 Ships Compared to Earlier Goals

Table 1 compares the 308-ship goal to earlier Navy ship force structure plans. Compared to the Navy’s previous 306-ship goal, the differences consist of a requirement for one additional amphibious ship (specifically, a 12th LPD-17 class amphibious ship) and a requirement for one additional Mobile Landing Platform/Afloat Forward Staging Base (MLP/AFSB) ship (a ship included in Table 1 in the “Other” category).

___________

10 See pages 205-206 of H.Rept. 113-446 of May 13, 2014.

11 Department of the Navy, Report to Congress [on] Navy Force Structure Assessment, February 2015, 5 pp. The cover letters for the report are dated March 17, 2015.

12 For more on this document, see CRS Report R42146, Assessing the January 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG): In Brief, by Catherine Dale and Pat Towell.

Table 1. Current 308 Ship Force Structure Goal Compared to Earlier Goals

| Ship type | 308- ship plan of March 2015 |

306- ship plan of January 2013 |

~310- 316 ship plan of March 2012 |

Revised 313-ship plan of Septem- ber 2011 |

Changes to February 2006 313 ship plan announced through mid-2011 |

February 2006 Navy plan for 313-ship fleet |

Early-2005 Navy plan for fleet of 260-325 Ships |

2002- 2004 navy plan for 375- ship Navya |

2001 QDR plan for 310- ship Navy |

|

| 260- ships |

325- ships |

|||||||||

| Ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) | 12b | 12b | 12-14b | 12b | 12b | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Cruise missile submarines (SSGNs) | 0c | 0c | 0-4c | 4c | 0c | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 or 4d |

| Attack submarines (SSNs) | 48 | 48 | ~48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 37 | 41 | 55 | 55 |

| Aircraft carriers | 11e | 11e | 11e | 11e | 11e | 11f | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 |

| Cruisers and destroyers | 88 | 88 | ~90 | 94 | 94g | 88 | 67 | 92 | 104 | 116 |

| Frigates | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) | 52 | 52 | ~55 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 63 | 82 | 56 | 0 |

| Amphibious ships | 34 | 33 | ~32 | 33 | 33h | 31 | 17 | 24 | 37 | 36 |

| MPF(F) shipsi | 0j | 0j | 0j | 0j | 0j | 12i | 14i | 20i | 0i | 0i |

| Combat logistics (resupply) ships | 29 | 29 | ~29 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 24 | 26 | 42 | 34 |

| Dedicated mine warfare ships | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26k | 16 |

| Joint High Speed Vessels (JHSVs) | 10l | 10l | 10l | 10l | 21l | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Otherm | 24 | 23 | ~23 | 16 | 24n | 17 | 10 | 11 | 25 | 25 |

| Total battle force ships | 308 | 306 | ~310-316 | 313 | 328 | 313 | 260 | 325 | 375 | 310 or 312 |

Sources: Table prepared by CRS based on U.S. Navy data.

Note: QDR is Quadrennial Defense Review. The “~” symbol means approximately and signals that the number in question may be refined as a result of the Naval Force Structure Assessment currently in progress.

a. Initial composition. Composition was subsequently modified.

b. The Navy plans to replace the 14 current Ohio-class SSBNs with a new class of 12 next-generation SSBNs. For further discussion, see CRS Report R41129, Navy Ohio Replacement (SSBN[X]) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

c. Although the Navy plans to continue operating its four SSGNs until they reach retirement age in the late 2020s, the Navy does not plan to replace these ships when they retire. This situation can be expressed in a table like this one with either a 4 or a zero.

d. The report on the 2001 QDR did not mention a specific figure for SSGNs. The Administration’s proposed FY2001 DOD budget requested funding to support the conversion of two available Trident SSBNs into SSGNs, and the retirement of two other Trident SSBNs. Congress, in marking up this request, supported a plan to convert all four available SSBNs into SSGNs.

e. With congressional approval, the goal has been temporarily be reduced to 10 carriers for the period between the retirement of the carrier Enterprise (CVN-65) in December 2012 and entry into service of the carrier Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78), currently scheduled for September 2015.

f. For a time, the Navy characterized the goal as 11 carriers in the nearer term, and eventually 12 carriers.

g. The 94-ship goal was announced by the Navy in an April 2011 report to Congress on naval force structure and missile defense.

h. The Navy acknowledged that meeting a requirement for being able to lift the assault echelons of 2.0 Marine Expeditionary Brigades (MEBs) would require a minimum of 33 amphibious ships rather than the 31 ships

shown in the February 2006 plan. For further discussion, see CRS Report RL34476, Navy LPD-17 Amphibious Ship Procurement: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

i. Today’s Maritime Prepositioning Force (MPF) ships are intended primarily to support Marine Corps operations ashore, rather than Navy combat operations, and thus are not counted as Navy battle force ships. The planned MPF (Future) ships, however, would have contributed to Navy combat capabilities (for example, by supporting Navy aircraft operations). For this reason, the ships in the planned MPF(F) squadron were counted by the Navy as battle force ships. The planned MPF(F) squadron was subsequently restructured into a different set of initiatives for enhancing the existing MPF squadrons; the Navy no longer plans to acquire an MPF(F) squadron.

j. The Navy no longer plans to acquire an MPF(F) squadron. The Navy, however, has procured or plans to procure some of the ships that were previously planned for the squadron—specifically, TAKE-1 class cargo ships, and Mobile Landing Platform (MLP)/Afloat Forward Staging Base (AFSB) ships. These ships are included in the total shown for “Other” ships.

k. The figure of 26 dedicated mine warfare ships included 10 ships maintained in a reduced mobilization status called Mobilization Category B. Ships in this status are not readily deployable and thus do not count as battle force ships. The 375-ship proposal thus implied transferring these 10 ships to a higher readiness status.

l. Totals shown include 5 ships transferred from the Army to the Navy and operated by the Navy primarily for the performance of Army missions.

m. This category includes, among other things, command ships and support ships.

n. The increase in this category from 17 ships under the February 2006 313-ship plan to 24 ships under the apparent 328-ship goal included the addition of one TAGOS ocean surveillance ship and the transfer into this category of six ships—three modified TAKE-1 class cargo ships, and three Mobile Landing Platform (MLP) ships—that were previously intended for the planned (but now canceled) MPF(F) squadron.

Navy’s Five-Year and 30-Year Shipbuilding Plans

Five-Year (FY2016-FY2020) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 2 shows the Navy’s FY2016 five-year (FY2016-FY2020) shipbuilding plan.

Table 2. Navy FY2016 Five-Year (FY2016-FY2020) Shipbuilding Plan

(Battle force ships—i.e., ships that count against 308-ship goal)

| Ship type | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | Total |

| Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carrier | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarine | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 14 |

| LHA(R) amphibious assault ship | 1 | 1 | ||||

| LPD-17 class amphibious ship | 1 | 1 | ||||

| LX(R) amphibious ship | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Fleet tug/salvage ship (TATS) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| Mobile Landing Platform (MLP)/Afloat Forward Staging Base (AFSB) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| TAO-205 (previously TAO[X]) oiler | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| TOTAL | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 48 |

Source: FY2016 Navy budget submission.

Notes: The MLP/AFSB is a variant of the MLP with additional features permitting it to serve in the role of an AFSB. The Navy proposes to fund the TATFs and TAO-205s through the National Defense Sealift Fund (NDSF) and the other ships through the Navy’s shipbuilding account, known formally as the Shipbuilding and Conversion, Navy (SCN) appropriation account.

Observations that can be made about the Navy’s proposed FY2016 five-year (FY2016-FY2020) shipbuilding plan include the following:

- Total of 48 ships. The plan includes a total of 48 ships, compared to a total of 44 ships in the FY2015-FY2019 five-year shipbuilding plan.

- Average of 8.8 ships per year. The plan includes an average of 9.6 battle force ships per year. The steady-state replacement rate for a fleet of 308 ships with an average service life of 35 years is 8.8 ships per year. In light of how the average shipbuilding rate since FY1993 has been substantially below 8.8 ships per year (see Appendix D), shipbuilding supporters for some time have wanted to increase the shipbuilding rate to a steady rate of 10 or more battle force ships per year.

- DDG-51 destroyers and Virginia-class submarines being procured under MYP arrangements. The 10 DDG-51 destroyers to be procured in FY2013- FY2017 and the 10 Virginia-class attack submarines to be procured in FY2014- FY2018 are being procured under multiyear procurement (MYP) contracts.13

- Flight III DDG-51 to begin with second ship in FY2016. The second of the two DDG-51s requested for FY2016 is to be the first Flight III variant of the DDG-51. The Flight III variant is to carry a new and more capable radar called the Air and Missile Defense Radar (AMDR).

- Modified LCS/Frigate to start in FY2019. The LCS program was restructured in 2014 at the direction of the Secretary of Defense. As a result of the restructuring, LCSs to be procured in FY2019 and beyond are to be built to a more heavily armed design. The Navy has stated that it will refer to these modified LCSs as frigates.

- 12th LPD-17 class ship added to FY2016. The LPD-17 class ship requested for FY2016 is to be the 12th ship in the class. The Navy had planned on procuring no more than 11 LPD-17s, but Congress has supported the procurement of a 12th LPD-17 by providing unrequested funding for a 12th ship in FY2013 and FY2015. Responding to these two funding actions, the Navy, as a part of its

- FY2016 budget submission, has inserted a 12th LPD-17 into its shipbuilding plan, and is requesting in FY2016 the remainder of the funding needed to fully fund the ship.

- TAO-205 procurement to begin FY2016. The TAO-205 class oiler (previously known as the TAO[X] class oiler) requested for procurement in FY2016 is to be the first in a new class of 17 ships.

30-Year (FY2016-FY2045) Shipbuilding Plan

Table 3 shows the Navy’s FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan. In devising a year shipbuilding plan to move the Navy toward its ship force-structure goal, key assumptions and planning factors include but are not limited to the following:

- ship service lives;

- estimated ship procurement costs;

___________

13 For more on MYP contracting, see CRS Report R41909, Multiyear Procurement (MYP) and Block Buy Contracting in Defense Acquisition: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Moshe Schwartz.

- projected shipbuilding funding levels; and

- industrial-base considerations.

| FY | CVN | LSC | SSC | SSN | SSBN | AWS | CLF | Supt | Total |

| 16 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |||

| 17 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | |||

| 18 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 19 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |||

| 20 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 21 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||

| 22 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11 | ||

| 23 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13 | |

| 24 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 12 | |

| 25 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 26 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 27 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 28 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 9 | |

| 29 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | ||

| 30 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| 31 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||

| 32 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| 33 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |

| 34 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |||

| 35 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| 36 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||||

| 37 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | |||||

| 38 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 9 | ||||

| 39 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 9 | |||||

| 40 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 10 | ||||

| 41 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | |||||

| 42 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||||

| 43 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 10 | |||

| 44 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||

| 45 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

Source: FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVN = aircraft carriers; LSC = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSC = small surface combatants (i.e., Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs]); SSN = attack submarines; SSGN = cruise missile submarines; SSBN = ballistic missile submarines; AWS = amphibious warfare ships; CLF = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

Navy’s Projected Force Levels Under 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Table 4 shows the Navy’s projection of ship force levels for FY2016-FY2045 that would result from implementing the FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan shown in Table 3.

| CVN | LSC | SSC | SSN | SSGN | SSBN | AWS | CLF | Supt | Total | |

| 308 ship plan | 11 | 88 | 52 | 48 | 0 | 12 | 34 | 29 | 34 | 308 |

| FY16 | 11 | 87 | 22 | 53 | 4 | 14 | 31 | 29 | 31 | 282 |

| FY17 | 11 | 90 | 26 | 50 | 4 | 14 | 32 | 29 | 28 | 284 |

| FY18 | 11 | 91 | 30 | 52 | 4 | 14 | 33 | 29 | 30 | 294 |

| FY19 | 11 | 94 | 33 | 50 | 4 | 14 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 300 |

| FY20 | 11 | 95 | 33 | 51 | 4 | 14 | 33 | 29 | 34 | 304 |

| FY21 | 11 | 96 | 34 | 51 | 4 | 14 | 33 | 29 | 34 | 306 |

| FY22 | 12 | 97 | 37 | 48 | 4 | 14 | 34 | 29 | 34 | 309 |

| FY23 | 12 | 98 | 36 | 49 | 4 | 14 | 34 | 29 | 34 | 310 |

| FY24 | 12 | 98 | 40 | 48 | 4 | 14 | 35 | 29 | 35 | 315 |

| FY25 | 11 | 98 | 43 | 47 | 4 | 14 | 35 | 29 | 36 | 317 |

| FY26 | 11 | 97 | 46 | 45 | 2 | 14 | 37 | 29 | 36 | 317 |

| FY27 | 11 | 99 | 49 | 44 | 1 | 13 | 37 | 29 | 36 | 319 |

| FY28 | 11 | 100 | 52 | 42 | 0 | 13 | 38 | 29 | 36 | 321 |

| FY29 | 11 | 98 | 52 | 41 | 0 | 12 | 37 | 29 | 36 | 316 |

| FY30 | 11 | 95 | 52 | 42 | 0 | 11 | 36 | 29 | 36 | 312 |

| FY31 | 11 | 91 | 52 | 43 | 0 | 11 | 36 | 29 | 35 | 308 |

| FY32 | 11 | 89 | 52 | 43 | 0 | 10 | 36 | 29 | 36 | 306 |

| FY33 | 11 | 88 | 52 | 44 | 0 | 10 | 37 | 29 | 36 | 307 |

| FY34 | 11 | 88 | 52 | 45 | 0 | 10 | 37 | 29 | 36 | 306 |

| FY35 | 11 | 88 | 52 | 46 | 0 | 10 | 36 | 29 | 37 | 309 |

| FY36 | 11 | 86 | 53 | 47 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 29 | 37 | 308 |

| FY37 | 11 | 85 | 53 | 48 | 0 | 10 | 35 | 29 | 36 | 307 |

| FY38 | 11 | 84 | 54 | 47 | 0 | 10 | 34 | 29 | 35 | 304 |

| FY39 | 11 | 85 | 56 | 47 | 0 | 10 | 34 | 29 | 32 | 304 |

| FY40 | 10 | 85 | 56 | 47 | 0 | 10 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 302 |

| FY41 | 10 | 85 | 54 | 47 | 0 | 11 | 34 | 29 | 32 | 302 |

| FY42 | 10 | 83 | 54 | 49 | 0 | 12 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 302 |

| FY43 | 10 | 83 | 54 | 49 | 0 | 12 | 32 | 29 | 32 | 301 |

| FY44 | 10 | 82 | 54 | 50 | 0 | 12 | 32 | 29 | 32 | 301 |

| FY45 | 10 | 82 | 57 | 50 | 0 | 12 | 33 | 29 | 32 | 305 |

Source: FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan.

Note: Figures for support ships include five JHSVs transferred from the Army to the Navy and operated by the Navy primarily for the performance of Army missions.

Key: FY = Fiscal Year; CVN = aircraft carriers; LSC = surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers); SSC = small surface combatants (i.e., frigates, Littoral Combat Ships [LCSs], and mine warfare ships); SSN = attack submarines; SSGN = cruise missile submarines; SSBN = ballistic missile submarines; AWS = amphibious warfare ships; CLF = combat logistics force (i.e., resupply) ships; Supt = support ships.

Observations that can be made about the Navy’s FY2016 30-year (FY2016-FY2045) shipbuilding plan and resulting projected force levels included the following:

- Total of 264 ships; average of about 8.8 per year. The plan includes a total of 264 ships to be procured, the same as the number in the FY2015 30-year (FY2015-FY2044) shipbuilding plan. The total of 264 ships equates to an average of 8.8 ships per year, which is equal to the average procurement rate (sometimes called the steady-state replacement rate) of 8.8 ships per year that would be needed over the long run to achieve and maintain a fleet of 308 ships, assuming an average life of 35 years for Navy ships.

- Projected shortfalls in amphibious ships, small surface combatants, and attack submarines. The FY2016 30-year shipbuilding plan, like many previous Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans, does not include enough ships to fully support all elements of the Navy’s 308-ship goal over the entire 30-year period. In particular, the Navy projects that the fleet would experience a shortfall in small surface combatants from FY2016 through FY2027, a shortfall in attack submarines from FY2025 through FY2036, and a shortfall in large surface combatants (i.e., cruisers and destroyers) from FY2036 through at least FY2045.

- Ballistic missile submarine force to be reduced temporarily to 10 or 11 boats. As a result of a decision in the FY2013 budget to defer the scheduled procurement of the first Ohio replacement (SSBN[X]) ballistic missile submarine by two years, from FY2019 to FY2021, the ballistic missile submarine force is projected to drop to a total of 10 or 11 boats—one or two boats below the 12-boat SSBN force-level goal—during the period FY2029-FY2041. The Navy says this reduction is acceptable for meeting current strategic nuclear deterrence mission requirements, because none of the 10 or 11 boats during these years will be encumbered by long-term maintenance.14

Comparison of First 10 Years of 30-Year Plans

Table 5 and Table 6 below show the first 10 years of planned annual ship procurement quantities and projected Navy force sizes in 30-year shipbuilding plans dating back to the first such plan, which was submitted in 2000 in conjunction with the FY2001 budget. By reading vertically down each column, one can see how the ship procurement quantity or Navy force size projected for a given fiscal year changed as that year drew closer to becoming the current budget year.

____________

14 For further discussion of this issue, see CRS Report R41129, Navy Ohio Replacement (SSBN[X]) Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke.

Years shown are fiscal years

| FY of 30-year plan (year submitted) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| FY01 plan (2000) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | |||||||||||||||

| FY02 plan (2001) | 6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY03 plan (2002) | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 11 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY04 plan (2003) | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| FY05 plan (2004) | 9 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| FY06 plan (2005) | 4 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 12 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY07 plan (2006) | 7 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | |||||||||||||||

| FY08 plan (2007) | 7 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 6 | |||||||||||||||

| FY09 plan (2008) | 7 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| FY10 plan (2009) | 8 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY11 plan (2010) | 9 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| FY12 plan (2011) | 10 | 13 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| FY13 plan (2012) | 10 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 9 | 12 | |||||||||||||||

| FY14 plan (2013) | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 14 | |||||||||||||||

| FY15 plan (2014) | 7 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 13 | |||||||||||||||

| FY16 plan (2015) | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 10 |

Source: Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans supplemented by annual Navy budget submissions (including 5-year shipbuilding plans) for fiscal years shown. n/a means not available—see notes below.

Notes:The FY2001 30-year plan submitted in 2000 was submitted under a one-time-only legislative provision, Section 1013 of the FY2000 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1059/P.L. 106-65 of October 5, 1999). No provision required DOD to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan in 2001 or 2002, when Congress considered DOD’s proposed FY2002 and FY2003 DOD budgets. (In addition, no FYDP was submitted in 2001, the first year of the George W. Bush Administration.) Section 1022 of the FY2003 Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4546/P.L. 107-314 of December 2, 2002) created a requirement to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year, in conjunction with each year’s defense budget. This provision was codified at 10 U.S.C. 231. The first 30-year plan submitted under this provision was the one submitted in 2003, in conjunction with the proposed FY2004 DOD budget. For the next several years, 30-year shipbuilding plans were submitted each year, in conjunction with each year’s proposed DOD budget. An exception occurred in 2009, the first year of the Obama Administration, when DOD submitted a

[-12-]

proposed budget for FY2010 with no accompanying FYDP or 30-year Navy shipbuilding plan. Section 1023 of the FY2011 Ike Skelton National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 6523/P.L. 111-383 of January 7, 2011) amended 10 U.S.C. 231 to require DOD to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan once every four years, in the same year that DOD submits a Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). Consistent with Section 1023, DOD did not submit a new 30-year shipbuilding plan at the time that it submitted the proposed FY2012 DOD budget. At the request of the House Armed Services Committee, the Navy submitted the FY2012 30-year (FY2012-FY2041) shipbuilding plan in late-May 2011. Section 1011 of the FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1540/P.L. 112-81 of December 31, 2011) amended 10 U.S.C. 231 to reinstate the requirement to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year, in conjunction with each year’s defense budget.

Years shown are fiscal years

| FY of 30-year plan (year submitted) | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| FY01 plan (2000) | 316 | 315 | 313 | 313 | 313 | 311 | 311 | 304 | 305 | 305 | |||||||||||||||

| FY02 plan (2001) | 316 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY03 plan (2002) | 314 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY04 plan (2003) | 292 | 292 | 291 | 296 | 301 | 305 | 308 | 313 | 317 | 321 | |||||||||||||||

| FY05 plan (2004) | 290 | 290 | 298 | 303 | 308 | 307 | 314 | 320 | 328 | 326 | |||||||||||||||

| FY06 plan (2005) | 289 | 293 | 297 | 301 | 301 | 306 | n/a | n/a | 305 | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY07 plan (2006) | 285 | 294 | 299 | 301 | 306 | 315 | 317 | 315 | 314 | 317 | |||||||||||||||

| FY08 plan (2007) | 286 | 289 | 293 | 302 | 310 | 311 | 307 | 311 | 314 | 322 | |||||||||||||||

| FY09 plan (2008) | 286 | 287 | 289 | 290 | 293 | 287 | 288 | 291 | 301 | 309 | |||||||||||||||

| FY10 plan (2009) | 287 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | |||||||||||||||

| FY11 plan (2010) | 284 | 287 | 287 | 285 | 285 | 292 | 298 | 305 | 311 | 315 | |||||||||||||||

| FY12 plan (2011) | 290 | 287 | 286 | 286 | 297 | 301 | 311 | 316 | 322 | 324 | |||||||||||||||

| FY13 plan (2012) | 285 | 279 | 276 | 284 | 285 | 292 | 300 | 295 | 296 | 298 | |||||||||||||||

| FY14 plan (2013) | 282 | 270 | 280 | 283 | 291 | 300 | 295 | 296 | 297 | 297 | |||||||||||||||

| FY15 plan (2014) | 274 | 280 | 286 | 295 | 301 | 304 | 304 | 306 | 311 | 313 | |||||||||||||||

| FY16 plan (2015) | 282 | 284 | 294 | 300 | 304 | 306 | 309 | 310 | 315 | 317 |

Source: Navy 30-year shipbuilding plans supplemented by annual Navy budget submissions (including 5-year shipbuilding plans) for fiscal years shown. n/a means not available—see notes below.

Notes: The FY2001 30-year plan submitted in 2000 was submitted under a one-time-only legislative provision, Section 1013 of the FY2000 National Defense Authorization Act (S. 1059/P.L. 106-65 of October 5, 1999). No provision required DOD to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan in 2001 or 2002, when Congress considered DOD’s proposed FY2002 and FY2003 DOD budgets. Section 1022 of the FY2003 Bob Stump National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4546/P.L. 107-314 of December 2, 2002) created a requirement to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year, in conjunction with each year’s defense budget. This provision was codified at 10 U.S.C. 231. The first 30-year plan submitted under this provision was the one submitted in 2003, in conjunction with the proposed FY2004 DOD budget. For the next several years, 30-year shipbuilding plans were submitted each year, in conjunction with each year’s proposed DOD budget. An exception occurred in 2009, the first year

[-14-]

of the Obama Administration, when DOD submitted a proposed budget for FY2010 with no accompanying FYDP or 30-year Navy shipbuilding plan. The FY2006 plan included data for only selected years beyond FY2011. Section 1023 of the FY2011 Ike Skelton National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 6523/P.L. 111-383 of January 7, 2011) amended 10 U.S.C. 231 to require DOD to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan once every four years, in the same year that DOD submits a Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). Consistent with Section 1023, DOD did not submit a new 30-year shipbuilding plan at the time that it submitted the proposed FY2012 DOD budget. At the request of the House Armed Services Committee, the Navy submitted the FY2012 30-year (FY2012-FY2041) shipbuilding plan in late-May 2011. Section 1011 of the FY2012 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 1540/P.L. 112-81 of December 31, 2011) amended 10 U.S.C. 231 to reinstate the requirement to submit a 30-year shipbuilding plan each year, in conjunction with each year’s defense budget.

Oversight Issues for Congress for FY2016

Potential Impact on Size and Capability of Navy of Limiting DOD Spending to BCA Caps Through FY2021

One issue for Congress concerns the potential impact on the size and capability of the Navy of limiting DOD spending through FY2021 to levels at or near the caps established in the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) as amended. Navy officials state that limiting DOD’s budget to such levels would lead to a smaller and less capable Navy that would not be capable of fully executing all the missions assigned to it under the defense strategic guidance document of 2012.

January 2015 Navy Testimony

In testimony on this issue to the Senate Armed Services Committee on January 28, 2015, then- Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert stated:

A return to sequestration in FY 2016 would necessitate a revisit and revision of the DSG [Defense Strategic Guidance document of January 2012]. Required cuts will force us to further delay critical warfighting capabilities, reduce readiness of forces needed for contingency response, forego or stretch procurement of ships and submarines, and further downsize weapons capability. We will be unable to mitigate the shortfalls like we did in FY2013 [in response to the sequester of March 1, 2013] because [unobligated] prior-year investment balances [which were included in the funds subject to the sequester] were depleted under [the] FY 2013 sequester [of March 1, 2013].

The revised discretionary caps imposed by sequestration would be a reduction of about

$10 billion in our FY 2016 budget alone, as compared to PB-2015. From FY 2016-2020, the reduction would amount to approximately $36 billion. If forced to budget at this level, it would reduce every appropriation, inducing deep cuts to Navy Operation and Maintenance (O&M), investment, and modernization accounts. The Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) accounts would likely experience a significant decline across the FYDP, severely curtailing the Navy’s ability to develop new technologies and asymmetric capabilities.

As I testified to this committee in November 2013, any scenario to address the fiscal constraints of the revised discretionary caps must include sufficient readiness, capability and manpower to complement the force structure capacity of ships and aircraft. This balance would need to be maintained to ensure each unit will be effective, even if the overall fleet is not able to execute the DSG. There are many ways to balance between force structure, readiness, capability, and manpower, but none that Navy has calculated that enable us to confidently execute the current defense strategy within dictated budget constraints.

As detailed in the Department of Defense’s April 2014 report, “Estimated Impacts of Sequestration-Level Funding,” one potential fiscal and programmatic scenario would result in a Navy of 2020 that would be unable to execute two of the ten DSG missions due to the compounding effects of sequestration on top of pre-existing FY 2013, 2014, and 2015 resource constraints. Specifically, the cuts would render us unable to sufficiently Project Power Despite Anti-Access/Area Denial Challenges and unable to Deter and Defeat Aggression. In addition, we would be forced to accept higher risk in five other DSG missions: Counter Terrorism and Irregular Warfare; Defend the Homeland and Provide Support to Civil Authorities; Provide a Stabilizing Presence; Conduct Stability and Counterinsurgency Operations; and Conduct Humanitarian,

Disaster Relief, and Other Operations. (Table 2 provides more detail on mission risks.) In short, a return to sequestration in FY 2016 will require a revision of our defense strategy.

- Critical assumptions I have used to base my assessments and calculate risk:

- Navy must maintain a credible, modern, and survivable sea-based strategic deterrent

- Navy must man its units

- Units that deploy must be ready

- People must be given adequate training and support services

- Readiness for deployed forces is higher priority than contingency response forces

- Capability must be protected, even at the expense of some capacity

- Modernized and asymmetric capabilities (advanced weapons, cyber, electronic warfare) are essential to projecting power against evolving, sophisticated adversaries

- The maritime industrial base is fragile—damage can be long-lasting, hard to reverse

The primary benchmarks I use to gauge Navy capability and capacity are DoD Global Force Management Allocation Plan presence requirements, Combatant Commander Operation and Contingency Plans, and Defense Planning Guidance Scenarios. Navy’s ability to execute DSG missions is assessed based on capabilities and capacity resident in the force in 2020.

The following section describes specific sequestration impacts to presence and readiness, force structure investments, and personnel under this fiscal and programmatic scenario:

Presence and Readiness

A return to sequestration would reduce our ability to deploy forces on the timeline required by Global Combatant Commands in the event of a contingency. Of the Navy’s current battle force, we maintain roughly 100 ships forward deployed, or 1/3 of our entire Navy. Included among the 100 ships are two CSG and two ARG forward at all times. CSGs and ARGs deliver a significant portion of our striking power, and we are committed to keeping, on average, three additional CSGs and three additional ARGs in a contingency response status, ready to deploy within 30 days to meet operation plans (OPLANs). However, if sequestered, we will prioritize the readiness of forces forward deployed at the expense of those in a contingency response status. We cannot do both. We will only be able to provide a response force of one CSG and one ARG. Our current OPLANs require a significantly more ready force than this reduced surge capacity could provide, because they are predicated on our ability to respond rapidly. Less contingency response capacity can mean higher casualties as wars are prolonged by the slow arrival of naval forces into a combat zone. Without the ability to respond rapidly enough, our forces could arrive too late to affect the outcome of a fight.

Our PB-2015 base budget funded ship and aviation depot maintenance to about 80 percent of the requirement in FY 2016-2019. This is insufficient in maintaining the Fleet and has forced us to rely upon Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding to address the shortfall. Sequestration would further aggravate existing Navy backlogs. The impacts of these growing backlogs may not be immediately apparent, but will result in greater funding needs in the future to make up for the shortfalls each year and potentially more material casualty reports (CASREPs), impacting operations. For aviation depot maintenance, the growing backlog will result in more aircraft awaiting maintenance and fewer operational aircraft on the flight line, which would create untenable scenarios in which squadrons would only get their full complement of aircraft just prior to deployment. The situation will lead to less proficient aircrews, decreased combat effectiveness of naval air forces, and increased potential for flight and ground mishaps.

Critical to mission success, our shore infrastructure provides the platforms from which our Sailors train and prepare. However, due the shortfalls over the last three years, we have been compelled to reduce funding in shore readiness since FY 2013 to preserve the operational readiness of our fleet. As a result, many of our shore facilities are degrading. At sequestration levels, this risk will be exacerbated and the condition of our shore infrastructure, including piers, runways, and mission-critical facilities, will further erode. This situation may lead to structural damage to our ships while pierside, aircraft damage from foreign object ingestion on deteriorated runways, and degraded communications within command centers. We run a greater risk of mishaps, serious injury, or health hazards to personnel.

Force Structure Investments

We must ensure that the Navy has the required capabilities to be effective, even if we cannot afford them in sufficient capacity to meet the DSG. The military requirements laid out in the DSG are benchmarked to the year 2020, but I am responsible for building and maintaining capabilities now for the Navy of the future. While sequestration causes significant near-term impacts, it would also create serious problems that would manifest themselves after 2020 and would be difficult to recover from.

In the near term, the magnitude of the sequester cuts would compel us to consider reducing major maritime and air acquisition programs; delaying asymmetric capabilities such as advanced jammers, sensors, and weapons; further reducing weapons procurement of missiles, torpedoes, and bombs; and further deferring shore infrastructure maintenance and upgrades. Because of its irreversibility, force structure cuts represent options of last resort for the Navy. We would look elsewhere to absorb sequestration shortfalls to the greatest extent possible.

Disruptions in naval ship design and construction plans are significant because of the long-lead time, specialized skills, and extent of integration needed to build military ships. Because ship construction can span up to nine years, program procurement cancelled in FY 2016 will not be felt by the Combatant Commanders until several years later when the size of the battle force begins to shrink as those ships are not delivered to the fleet at the planned time. Likewise, cancelled procurement in FY 2016 will likely cause some suppliers and vendors of our shipbuilding industrial base to close their businesses. This skilled, experienced and innovative workforce cannot be easily replaced and it could take years to recover from layoffs and shutdowns; and even longer if critical infrastructure is lost. Stability and predictability are critical to the health and sustainment of this vital sector of our Nation’s industrial capacity.

Personnel

In FY 2013 and 2014, the President exempted all military personnel accounts from sequestration out of national interest to safeguard the resources necessary to compensate the men and women serving to defend our Nation and to maintain the force levels required for national security. It was recognized that this action triggered a higher reduction in non-military personnel accounts.

If the President again exempts military personnel accounts from sequestration in FY 2016, then personnel compensation would continue to be protected. Overall, the Navy would protect personnel programs to the extent possible in order to retain the best people. As I testified in March 2014, quality of life is a critical component of the quality of service that we provide to our Sailors. Our Sailors are our most important asset and we must invest appropriately to keep a high caliber all-volunteer force. We will continue to fund Sailor support, family readiness, and education programs. While there may be some reductions to these programs if sequestered in FY 2016, I anticipate the reductions to be relatively small. However, as before, this would necessitate higher reductions to the other Navy accounts.

Conclusion

Navy is still recovering from the FY 2013 sequestration in terms of maintenance, training, and deployment lengths. Only 1/3 of Navy contingency response forces are ready to deploy within the required 30 days. With stable and consistent budgets, recovery is possible in 2018. However, if sequestered, we will not recover within this FYDP.

For the last three years, the Navy has been operating under reduced top-lines and significant shortfalls: $9 billion in FY 2013, $5 billion in FY 2014 and $11 billion in FY 2015, for a total shortfall of about $25 billion less than the President’s budget request. Reverting to revised sequester-level BCA caps would constitute an additional $5-10 billion decrement each year to Navy’s budget. With each year of sequestration, the loss of force structure, readiness, and future investments would cause our options to become increasingly constrained and drastic. The Navy already shrank 23 ships and 63,000 personnel between 2002 and 2012. It has few options left to find more efficiencies.

While Navy will do its part to help the Nation get its fiscal house in order, it is imperative we do so in a coherent and thoughtful manner to ensure appropriate readiness, warfighting capability, and forward presence—the attributes we depend upon for our Navy. Unless naval forces are properly sized, modernized at the right pace, ready to deploy with adequate training and equipment, and capable to respond in the numbers and at the speed required by Combatant Commanders, they will not be able to carry out the Nation’s defense strategy as written. We will be compelled to go to fewer places, and do fewer things. Most importantly, when facing major contingencies, our ability to fight and win will neither be quick nor decisive.

Unless this Nation envisions a significantly diminished global security role for its military, we must address the growing mismatch in ends, ways, and means. The world is becoming more complex, uncertain, and turbulent. Our adversaries’ capabilities are diversifying and expanding. Naval forces are more important than ever in building global security, projecting power, deterring foes, and rapidly responding to crises that affect our national security. A return to sequestration would seriously weaken the United States Navy’s ability to contribute to U.S. and global security.15

Greenert’s testimony concluded with the following table:

___________

15 Statement of Admiral Jonathan Greenert, U.S. Navy, Chief of Naval Operations, Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Impact of Sequestration on National Defense, January 28, 2015, pp. 4-9.

Source: Statement of Admiral Jonathan Greenert, U.S. Navy, Chief of Naval Operations, Before the Senate Armed Services Committee on the Impact of Sequestration on National Defense, January 28, 2015.

March 2015 Navy Report

The Navy’s March 2015 report to Congress on its FY2016 30-year shipbuilding plan states:

Long Term Navy Impact of Budget Control Act (BCA) Resource Level

The BCA is essentially a ten-percent reduction to DOD’s TOA. With the CVN [aircraft carrier] and OR [Ohio replacement] SSBN programs protected from this cut, as described above, there would be a compounding effect on the remainder of the Navy’s programs. The shortage of funding could potentially reverse the Navy’s progress towards recapitalizing a 308 ship battle force and could damage an already fragile shipbuilding industry. There are many ways to balance between force structure, readiness, capability, and manpower, but none that Navy has calculated that enable us to confidently execute the current defense strategy within BCA level funding.

If the BCA is not rescinded, it may impact Navy’s ability to procure those ships we intend to procure between now and FY2020. Although Navy would look elsewhere to absorb sequestration shortfalls because of the irreversibility of force structure cuts, a result might be that a number of the ships reflected in the current FYDP may be delayed to the future. The unintended consequence of these potential delays would be the increased costs of restoring these ships on top of an already stretched shipbuilding account that is trying to deal with the post FY2021 OR SSBN costs.

As previously articulated, barring changes to the Fleet’s operational requirements, the annual impact of sequestration level funding may require Navy to balance resources to

fund readiness accounts to keep what we have operating, manned, and trained. The net result of these actions could potentially create a smaller Navy that is limited in its ability to project power around the world and simply unable to execute the nation’s defense strategy. A decline would not be immediate due to the ongoing shipbuilding projects already procured but would impact the future fleet size. Disruptions in naval ship design and construction plans are significant because of the long-lead time, specialized skills, and integration needed to build military ships. The extent of these impacts would be directly related to the length of time we are under a BCA and the TOA reductions that are apportioned to the Navy.16

Affordability of 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan

Another potential oversight issue for Congress concerns the prospective affordability of the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan. In assessing the prospective affordability of the 30-year plan, key factors that Congress may consider include estimated ship procurement costs and future shipbuilding funding levels. Each of these is discussed below.

Estimated Ship Procurement Costs

If one or more Navy ship designs turn out to be more expensive to build than the Navy estimates, then the projected funding levels shown in the 30-year shipbuilding plan will not be sufficient to procure all the ships shown in the plan. Ship designs that can be viewed as posing a risk of being more expensive to build than the Navy estimates include Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class aircraft carriers, Ohio-replacement (SSBNX) class ballistic missile submarines, the Flight III version of the DDG-51 destroyer, the TAO-205 class oiler, and the LX(R) amphibious ship.

As shown in Table 7, the Navy estimates that the FY2016 30-year shipbuilding plan would cost an average of about $16.5 billion per year in constant FY2015 dollars to implement, including an average of about $16.9 billion per year during the first 10 years of the plan, an average of about $17.2 billion per year during the middle 10 years of the plan, and an average of about $15.2 billion per year during the final 10 years of the plan.

As also shown in Table 7, an October 2015 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on the Navy’s FY2015 30-year shipbuilding plan estimates that the plan will require 11.5% more funding to implement than the Navy estimates, including 7.7% more than the Navy estimates during the first 10 years of the plan, 11.6% more than the Navy estimates during the middle 10 years of the plan, and 17.1% more than the Navy estimates during the final 10 years of the plan.17 Over the years, CBO’s estimates of the cost to implement the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan have generally been higher than the Navy’s estimates.

Some of the difference between CBO’s estimates and the Navy’s estimates is due to a difference between CBO and the Navy in how to treat inflation in Navy shipbuilding. This difference compounds over time, making it increasingly important as a factor in the difference between CBO’s estimates and the Navy’s estimates the further one goes into the 30-year period. In other words, other things held equal, this factor tends to push the CBO and Navy estimates further and further apart as one proceeds from the earlier years of the plan to the later years of the plan.

___________

16 U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2016, March 2015, pp. 7-8.

17 Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan, Table 4 on p. 13.

| First 10 years of the plan | Middle 10 years of the plan | Final 10 years of the plan | Entire 30 years of the plan | |

| Navy estimate | 16.9 | 17.2 | 15.2 | 16.5 |

| CBO estimate | 18.2 | 19.2 | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| % difference between Navy and CBO estimates | 7.7% | 11.6% | 17.1% | 11.5% |

Source: Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan, Table 4 on p. 13.

The shipbuilding program that contributes the most to the difference between the CBO and Navy estimates of the cost of the 30-year plan is a future destroyer, called the DDG-51 Flight IV, that appears in the final 16 years of the 30-year plan. As shown in the CBO report, this one program accounts for 29% of the total difference between CBO and the Navy on the estimated cost implement the 30-year shipbuilding plan. The next-largest contributor to the overall difference is the Ohio replacement program, which accounts for 22%, followed by the Flight III version of the DDG-51 destroyer, which accounts for 12%.18 Together, the Flight III and Flight IV versions of the DDG-51 destroyer account for 41% of the total difference between CBO and the Navy.

- The relatively large contribution of the DDG-51 Flight IV destroyer to the overall difference between CBO and the Navy on the cost of the 30-year shipbuilding plan appears to be due primarily to three factors:

- There are many of these Flight IV destroyers in the 30-year plan—a total of 37, or 14% of the 264 total ships in the plan.

- There appears to be a basic difference between CBO and the Navy over the likely size (and thus cost) of this ship. The Navy appears to assume that the ship will use the current DDG-51 hull design, whereas CBO believes the growth potential of the current DDG-51 hull design will be exhausted by then, and that the Flight IV version of the ship will require a larger hull design (either a lengthened version of the DDG-51 hull design, or an entirely new hull design).

- These destroyers occur in the final 16 years of the 30-year plan, where the effects of the difference between CBO and the Navy on how to treat inflation in Navy shipbuilding are the most pronounced.

Future Shipbuilding Funding Levels

In large part due to the statutory requirement for the Navy to annually submit a report on its 30- year shipbuilding plan, it has been known for years that fully implementing the 30-year shipbuilding plan would require shipbuilding budgets in coming years that are considerably greater than those of recent years, and that funding requirements for the Ohio-replacement (OR) ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) program will put particular pressure on the shipbuilding budget during the middle years of the 30-year plan. The Navy’s report on the FY2016 30-year plan states:

___________

18 Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan, October 2015, Table B- 1 on page 35.

Within the Navy’s traditional Total Obligation Authority (TOA), and assuming that historic shipbuilding resources continue to be available, the OR SSBN would consume about half of the shipbuilding funding available in a given year – and would do so for a period of over a decade. The significant drain on available shipbuilding resources would manifest in reduced procurement quantities in the remaining capital ship programs. Therefore, additional resources for shipbuilding will likely be required during this period.

Since the CVN funding requirements are driven by the statutory requirement to maintain eleven CVNs, and accounting for one OR SSBN per year (starting in FY2026), there would only be about half of the resources normally available to procure the Navy’s remaining capital ships. At these projected funding levels, Navy would be limited to on average, as few as two other capital ships (SSN, DDG, CG, LPD, LHA, etc.) per year throughout this decade. In assessing the Navy’s ability to reach the higher annual shipbuilding funding levels described above, one perspective is to note that doing so would require the shipbuilding budget to be increased by 30% to 50% from levels in recent years. In a context of constraints on defense spending and competing demands for defense dollars, this perspective can make the goal of increasing the shipbuilding budget to these levels appear daunting....

The cost of the OR SSBN is significant relative to the resources available to DON in any given year. At the same time, the DON will have to address the block retirement of ships procured in large numbers during the 1980s, which are reaching the end of their service lives. The convergence of these events prevents DON from being able to shift resources within the shipbuilding account to accommodate the cost of the OR SSBN.

If DON funds the OR SSBN from within its own resources, OR SSBN construction will divert funding from construction of other ships in the battle force such as attack submarines, destroyers, aircraft carriers and amphibious warfare ships. The resulting battle force will not meet the requirements of the Force Structure Assessment (FSA), National Security Strategy, or the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). Additionally, there will be significant impact to the shipbuilding industrial base.19

The amount of additional shipbuilding funding that would be needed in coming years to fully implement the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan—an average of about $4.5 billion per year20— can be characterized in at least two ways. One is to note that this would equate to a roughly one- third increase in the shipbuilding budget above historical levels. Another is to note that this same amount of additional funding would equate to less than 1% of DOD’s annual budget.

Appropriate Future Size and Structure of Navy in Light of Strategic and Budgetary Changes

Overview

Another issue for Congress concerns the appropriate future size and structure of the Navy. Changes in strategic and budgetary circumstances in recent years have led to a broad debate over the future size and structure of the military, including the Navy. The Navy’s current goal for a fleet of 308 ships reflects a number of judgments and planning factors (some of which the Navy receives from the Office of the Secretary of Defense), including but not limited to the following:

__________

19 U.S. Navy, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2016, March 2015, pp. 7, 13-14.

20 Congressional Budget Office, An Analysis of the Navy’s Fiscal Year 2016 Shipbuilding Plan, October 2015, p. 3.

- U.S. interests and the U.S. role in the world, and the U.S. military strategy for supporting those interests and that role;

- current and projected Navy missions in support of U.S. military strategy, including both wartime operations and day-to-day forward-deployed operations;

- technologies available to the Navy, and the individual and networked capabilities of current and future Navy ships and aircraft;

- current and projected capabilities of potential adversaries, including their anti- access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities;

- regional combatant commander (COCOM) requests for forward-deployed Navy forces;

- basing arrangements for Navy ships, including numbers and locations of ships homeported in foreign countries;

- maintenance and deployment cycles for Navy ships; and

- fiscal constraints.

With regard to the fourth point above—regional combatant commander (COCOM) requests for forward-deployed Navy forces—as mentioned earlier, Navy officials testified in March 2014 that a Navy of 450 ships would be required to fully meet COCOM requests for forward-deployed Navy forces.21 The difference between a fleet of 450 ships and the current goal for a fleet of 308 ships can be viewed as one measure of operational risk associated with the goal of a fleet of 308 ships. A goal for a fleet of 450 ships might be viewed as a fiscally unconstrained goal.

As also mentioned earlier, world events since late 2013 have led some observers to conclude that the international security environment has undergone a shift from the familiar post-Cold War era of the past 20-25 years, also sometimes known as the unipolar moment (with the United States as the unipolar power), to a new and different strategic situation that features, among other things, renewed great power competition and challenges to elements of the U.S.-led international order that has operated since World War II. A shift from the post-Cold War era to a new strategic era could lead to a new reassessment of defense funding levels, strategy, missions, plans, and programs.22

For additional discussion of the relationship between U.S. strategy and the size and structure of U.S. naval forces that can form part of the context for assessing the 30-year shipbuilding plan, see Appendix C.

Proposals by Study Groups