The Navy Department Library

A Study of the General Board of the U.S. Navy, 1929-1933

Presented to the

Department of History

and the

Faculty of the Graduate College

University of Nebraska

In Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree

Master of Arts

University of Nebraska at Omaha

Scott T. Price

April, 1989

TABLE OF CONTESTS

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| PREFACE | iii | |

| Chapter | ||

| I. | ORIGINS | 1 |

| II. | THE WASHINGTON NAVAL TREATY AND OTHER NAVAL DEVELOPMENTS | 22 |

| III. | PRE-LONDON CONFERENCE NEGOTIATIONS | 48 |

| IV. | THE 1930 LONDON NAVAL CONFERENCE | 73 |

| V. | NAVAL BUILDUP OR REDUCTION? | 108 |

| VI. | WARSHIP DEVELOPMENT | 144 |

| VI. | CONCLUSION | 180 |

| APPENDIX | ||

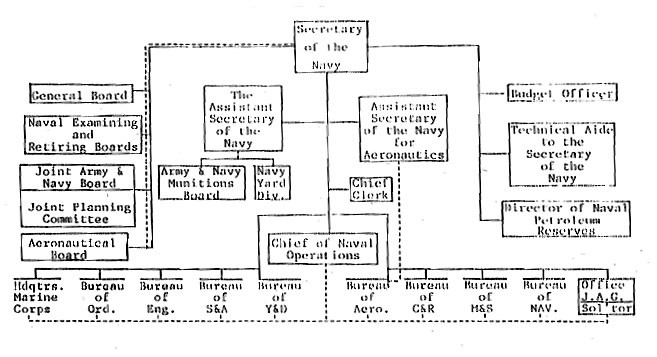

| I. | NAVY DEPARTMENT ORGANIZATION | 202 |

| II. | U.S. NAVAL CONSTRUCTION, 1929-1933 | 203 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 205 | |

Preface

In 1900, the then Secretary of the Navy, John T. Lone, organized the General Board of the United States Navy, the first permanent naval advisory body designed to advise the Secretary of the Navy on all aspects of the naval establishment. Secretary Long established the Board because he believed his not having received professional advice constituted a serious weakness in the Navy's administration. He ordered the Board to provide reports that recommended construction programs, technical details on the designs of new warships, and any other matter that concerned naval affairs that the Secretary saw fit to submit to the Board for its recommendations.

The principle aim of this thesis is to determine the influence of the General Board on the United States Navy during the Administration of Herbert Hoover. This thesis will also examine the interaction of the General Board with the civilian branches of the United States Government and examine the formation and early developments of the General Board. The years between 1928 and 1933 are ideal ones in which to examine the Board because it then exercised a wide range of functions not normally undertaken during other

--iii--

administrations. During Hoover's Administration the Board made official contact with the President, various Congressional committees, and Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson, while it worked under two successive Chiefs of Naval Operations, men who held divergent naval viewpoints. The period between 1928 and 1933 also witnessed the last international efforts prior to World War II to reduce naval armaments, efforts in which the Board acted in its advisory capacity. These years also saw the Board struggle with the development and implementation of new naval technologies while the nation teetered on the brink of economic collapse caused by the Great Depression.

The thesis is organized topically with the topics usually taken up in a chronological order. The first chapter examines the advisory boards that pre-dated the General Board, its inception in 1900, and provides an outline of its membership and duties. The second chapter covers the Board during the 1920's. The third and fourth chapters respectively address the 1930 London Naval Conference. The fifth chapter examines the Board as it functioned after the London Treaty through the end of President Hoover's Administration. The sixth chapter covers the Board's hearings on new warship design. The conclusion provides an over-all assessment of the General Board during the period of 1929 through 1933.

The extent of the Board's influence on naval and other

policy formulation by the Hoover Administration will be determined by examining the Board's recommendations made in light of contemporary domestic and international conditions. Therefore, this thesis will complement scholarly studies of the Hoover Administration by providing a focused look at how one faction of high ranking naval officers affected, viewed, and worked with the civilian branches of the government, thereby adding to historians' knowledge of the period. Therefore this thesis would complement such works as Martin L. Fausold's The Hoover Presidency: A Reappraisal and Warren I. Susman's Herbert Hoover and the Crisis of American Capitalism1.

By examining the Board's hearings and its recommendations made in light of its understanding of U.S. foreign policy and the policies of rival nations, this thesis will complement studies of international relations during the inter-war years. Such studies would include : Robert H. Ferrell's American Diplomacy in the Great Depression: Hoover-Stimson Foreign Policy, 1929-1933; Gerald E. Wheeler's Prelude to Pearl Harbor; Stephen Roskill's Naval Policy between the Wars, 1919-1939; Dorothy Borg's Pearl Harbor as History: Japanese-American Relations: 1931-1941. 2 This thesis will supplement such larger studies by providing a thorough definition and discussion of the principle advisory body of the U.S. Navy and its peace time role in national defense as well as by indicating the

--v--

extent to which both the Board's recommendations and Navy policies were conditioned by U.S. domestic interests and foreign policy during the Hoover Administration.

This thesis will also complement studies of the inter-war Navy by determining how the Board functioned within the Navy and how the-different, factions within the Navy viewed the Board and its work. Such an approach would complement studies that deal with the Navy's hierarchy, including: Robert Albion's Makers of Naval Policy and Robert Love's The Chiefs of Naval Operations 3. The Board's decisions concerning the development of emerging naval technologies, such as aviation and submarines, will also be covered. Therefore, this thesis would supplement such studies as Charles M. Melhorn's Two Block Fox: The Rise of the Aircraft Carrier and Clay Blair's Silent Victory4 .

The principal source of evidence for this thesis are the written records of the hearings of the General Board. Whereas I have studied all of the Board's eighty-four recorded hearings during the period of 1929-1933, I have included in the thesis only those hearings that affected major ship designs, international conferences, naval building programs, and major naval developments. Such hearings make up the majority of the hearings actually held. In my opinion, the topics of the remaining hearings were too narrow to shed any light on the subject of this thesis and therefore I did not include them. For example,

--v--

I did not refer to the Board's hearings on the naval dental corps, on stowage equipment for gas masks, and on the difference between classified and restricted documents.

I supplemented the records of the General Board's hearings with a number of other sources, including the reports of the. General Board, the official and private papers of President Herbert Hoover, his Secretary of the Navy, Charles F. Adams, Chairman of the General Board Rear-Admiral Mark L. Bristol, and Board member Rear-Admiral Charles B. McVay. Department of State records helped to fill in information not available in the naval records on the naval conferences and international negotiations.

I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. Bruce M. Garver, the chairman of my thesis committee, for his editorial guidance and support throughout the course of my thesis preparation. I would like to thank Dr. Peter Maslowski for first suggesting the topic of this thesis, for his expert critical advice, and also for taking the time to serve on my thesis committee. Finally, I would also like to thank Dr. Orville D. Menard and Dr. William Petrowski for pointing out a number of weak points in an early draft of this thesis and also for taking the time to serve on my thesis committee. I must also thank my maternal grandfather, Colonel Wilbur L. Thompson, U.S.A., for encouraging a young boy's fascination with things naval, a difficult task for a man who fought with the Third Army

--vii--

across the fields of France, Belgium, and Germany. I am quits sure that he had hoped I would follow in his footsteps, or at least show more enthusiasm for military history. I alone am responsible for any and all shortcomings with this thesis.

--viii--

ENDNOTES

1. Martin L. Fausold, ed., The Hoover Presidency: A Reappraisal (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1974); Joseph Hutchmacher and Warren I. Susman, eds., Herbert Hoover and the Crisis of American Capitalism, (Cambridge: Schenkman, Inc., 1973).

2. Robert H. Ferrell, American Diplomacy in the Great Depression: Hoover-Stimson Foreign Policy, 1929-1933 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1957); Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1963); Stephen Roskill, Naval Policy Between the Wars, 1919-1939, Vols. I&II (New York: Walker and Co., 1968); Dorothy Borg and Shumpei Okamato, eds., Pearl-Harbor as History: Japanese-American Relations: 1931-1941 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1973).

3. Robert G. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, 1798-1947 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, hereafter NIP, 1980); Robert W. Love, ed., The Chiefs of Naval Operations (Annapolis: NIP, 1980).

4. Charles M. Melhorn, Two Block Fox: The Rise of the Aircraft Carrier (Annapolis: NIP, 1974); Clay Blair, Jr., Silent Victory, The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan (New York: Bantam Books, 1976).

--ix--

CHAPTER ONE

ORIGINS

One cannot understand how the General Board functioned during Herbert Hoover's Presidency without some knowledge of the history and development of the General Board and the several naval advisory bodies that preceded it. This chapter will survey the evolution of these advisory bodies before discussing the Board's inception in the context of national and naval conditions at that time. The chapter will conclude by examining the Board's subsequent evolution within the naval establishment up to the inauguration of Herbert Hoover in March 1929.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Americans debated the extent to which the United States should play a larger part in world affairs and the extent to which growing international interests would require an increase in the size of the U.S. Navy. In 1896, President Eliot of Harvard University expressed the view of many Americans who believed that any large American military buildup would be incompatible with traditional American values and institutions. He stated:

The building of a navy and the presence of a large standing army mean... the abandonment of what is characteristically American... The building of a navy, and particularly of

--1--

battleships, is English and French policy. It should never be ours.1

Eliot's speech was but one of many statements critical of the turn of the century expansion and modernization of the U.S. Navy, guided in part by the ideas of such naval officers as Stephen Luce and Alfred Mahan. No longer would the Navy be required only to protect the coasts of the United States. Luce and Mahan provided the Navy with an ideological rationale for building a large fleet capable of supporting the growing imperialistic policies of the government. Politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt supported Luce's and Mahan's theories and consequently advocated the construction of a large steel battle fleet.

In 1898 the United States went to war with a European opponent for the first time since 1812. In the Pacific and the Caribbean, the fleets of the U.S. and Spain fought battles that matched steam-powered steel vessels capable of firing armor piercing projectiles from turreted guns. The U.S. won the war at sea and on land, thereby gaining its first overseas possessions and becoming one of the world's colonial powers.

Although American arms were everywhere victorious, the Spanish-American war highlighted a number of shortcomings in the U.S. Army and Navy. Problems in the Navy included a lack of war planning, organization, and coordination. The horizontal distribution of power in the Navy Department was the source of the problems. Under the Secretary of the

--2--

Navy (hereafter referred to as SECNAV) worked eight independent bureaus who answered only to the civilian SECNAV. A political appointee, the SECNAV usually had little or no background in naval affairs, and as such could not effectively coordinate the functions of the various bureaus or prepare the U.S. Navy for war.2

The eight naval bureaus, created by Congress between 1842 and 1862, provided technically qualified personnel to handle the various aspects of naval maintenance and controlled the shore and fleet functions of the Navy. The Bureau of Yards and Docks constructed and maintained public works; Supplies and Accounts procured, stored, and distributed supplies; Ordnance handled the development, procurement, and storage of all weapons and ammunition; Naval Personnel, later referred to as the Bureau of Navigation, handled the training and detailing of personnel; Engineering designed warship powerplants; Construction and Repair handled the planning and construction or repair of naval vessels at Navy yards; Equipment and Recruiting; and Medicine and Surgery. Aeronautics, established in 1921, handled all matters that pertained to naval aviation.3

A single officer of flag rank headed each bureau and he jealously guarded his jurisdiction. The bureaus dealt directly with Congress on the important matter of appropriations. The bureau chiefs established the principle that Congress appropriated funds directly to the bureaus

--3--

rather than to the Navy Department. Therefore funds could not be transferred to other offices in the Navy Department. The chiefs also dealt with the SECNAV directly, and thus possessed considerable autonomy. Such a power structure had the dual effect of increasing the Secretary's responsibility by requiring him to sign the minor administrative papers of each bureau, while at the same time reducing, his control through the sheer number of bodies directly under him. Thus, because only the SECNAV had the power to coordinate the actions of the bureaus, to appoint a poor administrator to the post invited "disaster."4

On the whole, the bureau system offered a satisfactory method of dividing work within the Department along functional lines and it provided a means of specialization needed due to the technological advances occurring in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Yet there was no naval strategic planning body or coordinating agency that could set up a naval policy or develop war plans. Many officers, including Captain Alfred Mahan, took a cue from the Prussian Army and advocated the creation of a naval "General Staff" to lead the organizing and planning of the Navy and to advise the SECNAV.

Until the formation of the General Board in 1900, the SECNAV had to ask the advice of any naval officers close at hand, usually one of the bureau chiefs. The Navy Department established some advisory boards to give advice on a

--4--

particular issue and were then promptly dismissed, much like the select committees of Congress. Because these boards were not permanent, they only temporarily solved the advisory problem. 5

The first of these advisory boards was the Board of Navy Commissioners, active from 1815 through 1842, and handled administrative matters and occasionally offered advice on policy. The Board was unsatisfactory because the members had to be familiar with all aspects of the business concerns of the department, and "were thus constantly overloaded with work."6 In 1842 Congress replaced the Board of Navy Commissioners with the bureau system.

The establishment of the United States Naval Institute at Annapolis, Maryland on October 9, 1873 aimed to promote "the advancement of professional and scientific knowledge" within the naval establishment. Under the guidance of such men as Captain Stephen B. Luce, the monthly meetings of the Institute and its resultant published essays began to explore the areas of naval policy and development. Some soon to be prominent names began to appear in the published United States Naval Institute Proceedings, including Alfred T. Mahan and William S. Sims.7

In 1884, the Navy Department established the Naval War College, primarily due to the efforts of Commodore Stephen B. Luce. The College enabled a number of officers to be freed from their regular responsibilities with the fleet or

--5--

the bureaus to "think along broad, creative lines," in relation to U.S. naval development. The officers primarily studied strategy and played war games against potential adversaries, but also discussed questions of naval policy. Combined with the information gathered by the newly created Office of Naval Intelligence (hereafter ONI) in 1882, the Naval War College now formulated war plans for the Navy Department.8

Arguably the College's most important contribution to naval reform was to give Captain A.T. Mahan a chance to write and deliver those lectures that he later compiled and published as The Influence of Sea Power Upon History in May of 1890, the work that thrust him into the international spotlight. Naval officers from admiralties all over the globe read and studied Mahan's theories on the strategic principles of sea power. Consequently Mahan's theories influenced the development of many navies, including that of the U.S.9

Another important event in the eventual formation of the General Board was the creation of four temporary Naval advisory boards, one in 1881, 1882, 1889, and 1898. SECNAV William H. Hunt convened the first board on the orders of President Chester A. Arthur, who supported a naval modernization effort. Hunt assigned the board of fifteen naval officers to define the basic requirements of President Arthur's modernization plan and then determine what type of

--6--

warships should be built. The board recommended the construction of 159 various ships, including "steel steamers of war, armed with rifled ordnance," to be completed during an eight year plan.10 Congress was not ready to authorize the construction of so many vessels so Hunt shelved the plan and disbanded the board. 11

SECNAV William E. Chandler convened a second board in 1882 that scaled down the previous board's requests so that Congress appropriated funds for the construction of four warships in 1S83, sometimes known as the "ABCD's." Chandler then disbanded the board. Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy created the next board on July 16, 1889. Its job was to "study the naval requirements of the United States," and helped Secretary Tracy forge the fleet he intended to build.12 The board recommended that the U.S. build a fleet of twenty battleships and sixty cruisers. Tracy then disbanded the board. Congress appropriated enough money to build three "seagoing, coastline battleships."13

The next important step in the eventual formation of the General Board came with the creation of the Naval War Board, convened by Secretary of the Navy John D. Long at the prodding of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, during the first week of April, 1898. Long ordered the board to advise the Administration on operational plans for a possible war with Spain. The board

--7--

first consisted of Assistant SECNAV Theodore Roosevelt, Rear Admiral Montgomery Sicard, Captain A. S. Barker, Captain A. S. Crowninshield, the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, and Commander Richardson Clover, the Chief Intelligence Officer. After the outbreak of war between Spain and the U.S., Roosevelt, Barker, and Clover left the board for war commands and Long called Captain Mahan back from retirement to serve in their place.14

The board met daily throughout the war, collected information, advised the SECNAV on matters of strategic policy, and reviewed war plans drawn up by the Naval War College. The board also participated in cabinet meetings and military councils at the White House and counciled the Administration on questions of strategy. Long disbanded the board at the end of the war.15

Mahan, like many naval officers, believed that the Naval Board was an ineffective substitute for what was really required, a naval general staff. When asked later about the effectiveness of the Naval War Board, Mahan said: "Fortunately, the war was short and simple."16 SECNAV Long conceded the need for permanent and effective planning and coordination within the U.S. Navy, but did not subscribe to Mahan's concept of a Naval General Staff. Fearful that such an organization would eventually become more powerful than the civilian SECNAV, he established "That able body of naval statesmen," otherwise known as the General Board of

--8--

the Navy, by General Order No. 544 on March 13, 1900.17 The order stated that: "The purpose of the Department in establishing this board is to insure efficient preparation of the fleet in case of war and for the naval defense of the coast."18 Long also ordered the Board to coordinate the work of the Naval War College and the ONI.

Unlike a general staff, the General Board was only an advisory body and had no executive powers. It also differed from a general staff by having a president who did not serve as the supreme operational commander of the battle fleet in war-time. Nevertheless, Senator Frederick Hale of Maine, the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs and the Bureau chiefs, bitterly opposed Long's proposal. They feared the Board would become to powerful and would infringe on the bureau's functions. But these opponents acquiesced because the Board failed to gain legislative sanction and only existed by a Navy Department order, whereas the bureaus received their power by Congressional action.19 The influence of the Board's first and only president, the popular war hero Admiral George Dewey, also helped to secure the Board's position within the Navy Department.

Not all officers shared Long's fear of a general staff. Mahan called the General Board a "pallid child of the Naval War Board," yet he did agree that the General Board was an improvement over the previous "appointed" boards.20 Mahan

--9--

wrote that the General Board was "eminently" fitted to coordinate the work of the Department and the Fleet, and to keep a "general surveillance" over the larger strategical and technical questions, which could not be dealt with by the commanders of the squadrons or the bureau chiefs.21

General Order No. 544 provided for the following membership on the Board: The Admiral of the Navy; the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation; the Chief Intelligence Officer and his principal assistant; the President of the Naval War College and his principle assistant; and three other officers above the grade of Lieutenant Commander, later changed to the rank of Captain.22

In 1903, SECNAV Long and his opposite in the War Department created the Joint Army and Navy Board. As designed, the Joint Board advised both Secretaries in matters that involved inter-service cooperation, including the development of joint war plans. The membership of the Joint Board consisted of four members of the General Board and four from the U.S. Army's General Staff, also created in 1903. Admiral Dewey became its President. As with the General Board, the Joint Board was only advisory and held no executive powers.23

The creation of the General Board did not silence the advocates of a naval general staff, including Mahan, who clamored for a Chief of Naval Operations and a suitable staff responsible for all war planning and fleet control,

--10--

but still subservient to the Secretary of the Navy. Mahan gained a friendly ear in the executive branch when Theodore Roosevelt became President. Under Mahan's prodding, Roosevelt set up and appointed Mahan to the "Moody Commission." Roosevelt ordered the commission to study the "structure, efficiency, and functions" of the bureaus and the "encroachment" of civilian control over the bureaus, and to examine the war planning capabilities "within the Navy Department."24

The Commission proposed that the Navy Department be divided into five divisions, headed by four flag officers and the assistant secretary. The primary division would be that of Naval Operations and its head would be the secretary's principal advisor who would also be the ex-officio head of the General Board. His staff would be responsible for war planning, the formulation, of general naval policy, and the administration of the Naval War College and the ONI. However the Commission's report died in Congress.

The Commission's efforts were not totally in vain because the next SECNAV, George von L. Meyer, introduced a modified General Staff system, with four line aides for operations, material, inspection, and personnel. Meyer superimposed the aides on the Bureau system. The aides for operations, material, and for personnel joined the General Board as ex-officio members. Later the Commandant of the Marine Corps also became another ex-officio member. The

--11--

aides, however, did not receive legitimization from Congress. SECNAV Josephus Daniels, who succeeded Meyer in 1913, eliminated all of the aides except the aide for operations. 26

Perhaps the most important change in the U.S. Navy's administration and one that affected the General Board came with the creation of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (hereafter referred to as CNO). The aide for operations, Admiral Bradley A. Fiske, against Secretary Daniel's objections, managed to secure the passage of a bill that created the Office of the CNO "charged with the operations of the fleet and with the preparations and readiness of plans for its use in war," on March 3, 1915.27 But, due to Daniels pleas that this office would lead to the "Prussianization" of the naval officer corps, Congress limited the CNO's power by giving him no authority over the bureaus and "enjoined him to work under the direction of no the civilian secretary."28 The CNO took over the General Board's vital function of war planning, the first major reduction of the Board's role. The CNO also became an ex-officio member of the Board.29

The United States Navy Regulations for 1920 stated that the Board had no executive or administrative duties and only served in an advisory capacity to the SECNAV. It also specified the subjects the Board was responsible for, including the formulation of a naval policy for the U.S.

--12--

and an annual building program for the SECNAV that specified the number and types of ships the Board believed /ere necessary for the fleet.30 The Regulations also ordered the Board to recommend the military characteristics that should be "embodied in the designs to be prepared for new ships," and further instructed the SECNAV to consult the General Board if the U.S. Navy made any changes or modifications on any new designs for ships or aircraft or on any commissioned vessels already with the fleet. 31

The Board consisted of two main sections: the Executive Committee which was the working part of the Board, and the ex-officio members. The SECNAV appointed the members of the Executive Committee of the General Board, and they served on the Board full time. Appointed officers were usually of flag rank, although the SECNAV appointed some captains. There was no specified duration of the appointment. The SECNAV made his choice after consulting the CNO. With the death of Admiral Dewey in 1917, the U.S. Navy dropped the office of President of the General Board "in tribute to his memory." 32 The senior executive officer of the Board then acted as the Chairman.

The Regulations further divided the Executive Committee into four "Sections." The First Section dealt with any matters relating to the fleet that the SECNAV asked the Board to consider, which included maintenance, distribution, operation, training, the number and rank of officers,

--13--

and the number and rating of seamen. The Second Section dealt with all matters that pertained to the preparation for war and matters related to the international policy of the U.S. The Third Section considered the "numbers and types of ships proper to constitute the fleet."33 The Fourth Section considered all matters related to shore stations, fuel depots, and logistics. The Chairman of the Board made the appointments to each section, and depending on the number of officers serving on the Executive Committee, he usually appointed two officers to each.34

The SECNAV or the CNO referred requests on paper to the Executive Committee of the General Board, which met every day at 10:00 AM. The Committee gave each paper a serial number and then made copies of the paper for all members concerned with its topic. The Board referred to these copies as "brown papers," because of the color of the paper on which they were mimeographed. The Chairman of the Board forwarded the brown papers to the ex-officio members and any of the bureaus involved in or affected by the study, and he assigned the paper to one of the four sections.35

The officer in charge of the study submitted his findings to the Chairman, usually after several months of study and hearings held in the Board's office. The Board invited any bureau members, civilians, or officers involved to attend the hearings and share their views or ideas on

--14--

the subject under study. The Navy Regulations made clear that the Board should "avail itself of all sources of information, civil and naval, foreign and domestic," so that any recommendations made would be based on "the best obtainable information."36 The secretary of the Board then typed up the findings on a "yellow paper." The Executive Committee discussed the yellow paper prior to presenting it to the full Board.

The final reports submitted to the SECNAV or the CNO always began with the words "The General Board recommends," hat suggested unanimity among the members. This was a tactic designed to lend force to the Board's recommendations. The Executive Committee never allowed any minority reports because such reports "might suggest unequal distribution of information and opinions" within the Board. 37 Supporting arguments preceded all decisions and recommendations made by the Board. Only the senior member of the board present at the final hearing signed the recommendation or report before submitting it to the SECNAV, again reinforcing the idea of unanimity. One should note that although the reports did not include minority opinions, the decisions reached by the Board did not always reflect the opinions of the entire U.S. Navy.

After 1918, the full Board met at the Navy Department building on Constitution Avenue, usually at 10:00AM on the Last Tuesday of each month. During these meetings the

--15--

entire General Board discussed, modified, and approved the final yellow papers. Once approved, the Chairman or the senior officer present signed the report and had it forwarded to the SECNAV. 38

The formulation of a naval policy for the U.S. was one of the primary tasks of the General Board. The policy formulated 1913 noted that the U.S. fleet, as it existed, was inadequate to support the "advancement of national 39 policies. The Board also noted that the Navy bore no relationship to political parties, and should "not be affected by changes of administration." This assertion by the Board that the Navy was in no way connected with politics may have been sincerely believed by the members, but such a belief did not reflect reality. A civilian appointee headed the War and Navy Departments, and the entire military establishment answered to an elected Chief Executive. Despite such facts, the officers believed that they were disassociated from politics.

Another of the more important functions of the Board was the yearly recommended naval building program whereby the Board recommended the numbers and types of ships that the Board believed should be constructed. Naval finance, as with the other government departments, required long term planning. In order to obtain legislative acceptance of its fiscal 1929 budget, the Navy began working on it in the spring of 1927, or two years before the money would be

--16--

spent. As such, the Board submitted its building program for the fiscal 1929 budget during the middle months of 1927.

Occasionally, as in 1916 in response to a request from President Wilson, the SECNAV would ask the Board to develop a special building program to meet a current crisis. Here the Board recommended the construction of 60 capital ships to make the U.S. Navy "second to none." Congress authorized the construction of 162 vessels. Because Congress had to first authorize the construction of vessels, and in a separate act would or would not appropriate money for their construction, the U.S. Navy was still constructing vessels from the 1916 authorization through 1931.

The General Board also developed plans for new warships and throughout the period following the Washington Naval Conference. The Board attempted to determine how such new ships would fit into war plans developed by the Joint Board. The Naval War Collage also tested new designs during war games conducted at the College and submitted a report on the ship's performance to the Board.

The Board determined the characteristics of new warships after holding hearings attended by the representatives of the War Plans Division of the Office of the CNO, Bureau of Aeronautics, Construction and Repair, Engineering and Ordnance. As noted earlier, the Bureaus were

--17--

independent and responsible only to the SECNAV. Their lack of coordination could, at times, cause considerable friction and confusion. For example, Ordnance designed and built a warship's armament, Construction and Repair designed the actual vessel and its armor protection, and Engineering designed the powerplant. If any one bureau changed or modified its original plans, the other bureaus would then have to modify their plans accordingly. The General Board acted as the only coordinating body between the bureaus. The designs approved by the Beard were always based on considerable compromise. The Treaty restrictions made the design problem more difficult, because any changes made in the original design affected the one design factor that could not be compromised, the tonnage of the vessel, as it was set by the Washington Treaty.

Thus, the General Board was born out of the SECNAV's need to have a body of professional officers to advise him and help coordinate the actions of all naval bureaus. Even thought the General Board only exercised advisory powers and in 1915 lost its war planning function to the CNO, the Board was, by the time of the Presidential election of 1928, well established in the Navy Department and continued to make important recommendations on almost all aspects of U.S. naval affairs.

--18--

ENDNOTES

1. As quoted in Barbara Tuchman, Practicing History (New York: Harper and Row, 1984), p. 35.

2. Robert G. Albion, "The Administration of the Navy, 1798-1945," Public Administration Review, V (Autumn, 1945), pp. 298-300; John R. Wilson, "Herbert Hoover and the Armed Forces: A Study of Presidential Attitudes and Policy," Doctoral Dissertation, Northwestern University, 1971, p. 28.

3. Henry P. Beers, "The Development of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations," Military Affairs, X (Spring, 1946), pp. 42-43; Albion, "The Administration of the Navy," pp. 297-299.

4. Robert H. Connery, The Navy Yard the Industrial Mobilization in World War II (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), p. 14; Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 298; Wilson, "Herbert Hoover and the Armed Forces," p. 28.

5. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 74.

6. Ibid., pp. 70-71.

7. Ibid., pp. 72-73.

8. Beers, "Chief of Naval Operations," p. 48. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 72.

9. Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1890).

10. Charles O. Paullin, Paullin's History of Naval Administration, 1775-1911: A Collection of Articles from the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1968), pp. 370, 388.

11. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 76.

12. Ibid., p. 77. Harold and Margaret Sprout, The Rise of American Naval Power (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946), pp 206-209. Walter R. Herrick, Jr., The American Naval Revolution (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966), p. 47.

13. Ibid.; See also Ronald Spector, "The Triumph of

--19--

Professional Ideology: The U.S. Navy in the 1890s, in Kenneth J. Hagan, ed., In Peace and War, Interpretations of American Naval History, 1775-1894, 2nd ed. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1984), p. 176.

14. Beers, "The Development of the Office of the Chief of Naval operations," pp. 53-54; Herrick, The American Naval Revolution, p. 228. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 77.

15. Ibid.

16. Robert Seager II, ed., Alfred Thayer Mahan: The Man and His Letters, (Annapolis: NIP, 1974), p. 541.

17. Jarvis, Butler, "The General Board of the Navy," Naval Institute Proceedings, LVI (August, 1933), p. 700; John D. Long, The New American Navy (New York: The Outlook Company, 1903), pp. 183-186.

18. Ibid.

19. Beers, "The Development of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations," pp. 54-55.

20. Seager, Mahan: The Man and His Letters, p. 540.

21. Butler, "General Board," p. 702.

22. Memorandum, Captain Robert L. Ghormley to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ernest Jahnks, "The General Board," 14 December 1919, Presidential Papers, Official Files (hereafter referred to as OF), General Board Records (hereafter 18m-Navy), Herbert Hoover Presidential Library (hereafter HHPL), West Branch, Iowa.

23. Fred Greene, "The Military View of American National Policy, 1904-1940," The American Historical Review, LXVI (January, "1964), p. 354; Louis Morton, "War Plan ORANGE: Evolution of a Strategy," World Politics, XI (January, 1959), p. 225; Louis Morton, United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific, vol. 2, Strategy and Command: The First Two Years (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, hereafter USGPO, 1962), p. 22.

24. Seager, Mahan: The Man and His Letters, p. 543.

25. Ibid.

26. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, pp. 12-13.

27. Love, The Chiefs of Naval Operations, p. xvii.

--20--

28. Ibid.

29. The War Plans Division of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations was charged with creating war plans. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 89.

30. United States Navy Regulations, 1928 edition (Washington, D.C.: USGPO, 1921), pp. 138-139.

31. Ibid.

32. Butler, "General Board," p. 703. Navy Regulation 434, Navy Regulations, p. 139.

33. Memorandum, no author, "Duty of Members of the Executive Committee," Official Correspondence File, Marx L. Bristol Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division (hereafter LC).

34. Ibid. As quoted in Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 84.

35. Memorandum, no author, 11 December, 1920, "General Board," Official Correspondence, Bristol Papers, LC.

36. Navy Regulation 404, Navy Regulations, 1923, p. 139.

37. Memorandum, no author, "General Board Policy and Practice," No . 1024, Official Correspondence, Bristol Papers, LC.

38. Memorandum, no author, 11 December, 1920, "General Board," Official Correspondence, Bristol Papers, LC.

39. As quoted in Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, p. 84.

40. Ibid.

41. Wilson, "Herbert Hoover," p. 53; In 1921, the Budget Act created the Bureau of the Budget whereby all executive departments would have to first obtain the Bureau's approval of the department's appropriation request. Now, each department had to leap two hurdles in order to obtain funding: Congress and the Bureau of the Budget. See Percival F. Brundage, The Bureau of the Budget (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), p. 3.

42. Albion, Makers of Naval Policy, pp. 112-129.

43. Ibid., pp. 112-129, 83.

--21--

CHAPTER TWO

THE WASHINGTON NAVAL TREATY AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTS

The decade of the 1920's were important years in the development of the post-war U.S. Navy, primarily because of the continued efforts by all leading naval powers to build up and improve the quality of their fleets at a time when the League of Nations and most diplomats and politicians attempted to limit naval expansion. The latter-groups convened conferences at Washington, D.C. and Geneva, to reduce the fleets of the major powers and establish building ratios for the different classes of vessels that made up each fleet. This chapter will cover these conferences and other events of the 1920's that affected the U.S. Navy and the General Board and would condition the naval policies of President Hoover.

Although the 1916 construction program authorized by the Naval Act of 1916 slowed down after Germany's capitulation in November 1918, the Board never gave up advocating a fleet "second to none." It contended that only by completing the 1916 program could America's interests, as defined by the Board, be secure. Despite the Board's advice, the construction program authorized in 1916 was cut short after 1919. The war was over and the German fleet

--22--

lay at the bottom of Scapa Flow. Congress recognized that the U.S. no longer faced any immediate threat that required a massive fleet. In 1921, the newly elected President, Warren G. Harding, proposed that the major naval powers attend a naval reduction conference in Washington. Harding hoped to reduce international tensions between the former allies brought about by naval expansion. The resultant treaty from the conference further limited the 1916 building program by setting capital ship tonnage, at 525,000 tons for Great Britain and the United States, 315,000 tons for Japan, and 175,000 tons for Italy and France.1

The Treaty was less than popular with the members of the General Board, the only exception being RADM William V. Pratt, a Board member and negotiator at the Conference. As a whole, the Board believed that the Treaty restricted the U.S. Navy in such a way as to prevent the fleet from fulfilling what the Board believed to be the Navy's obligations in defending certain "cardinal" U.S. policies. The policies included: the Monroe Doctrine, no entangling alliances with foreign governments, maintaining the Open Door in China, the restriction of Asiatic immigration to the U.S., access to raw materials, and the defense of U.S. possessions.2 "The Board took particular exception to Article XIX of the Treaty.

Article XIX of the Treaty affected the plans of the General Board and consequently, that of the Joint Board.

--23--

The Navy reorganized the Joint Board in 1918 by replacing the four General Board members with the CNO, the Assistant CNO, and the Director of the War Plans Division of the Office of the CNO. The Navy and War Departments gave the Joint Board, which met monthly, an effective staff, called the Joint Planning Committee. Comprised of three officers from each department's war planning division who met weekly, the Joint Planning Committee handled questions referred to it by the Joint Board.3 After the reorganization, the formulation of the actual policy regarding naval war plans and fleet operations rested with the Office of the CNO based in part on the recommendations of the Joint Board. Under the reorganization, the General Board's influence on policy came only on the design, types, and numbers of new vessels. Such vessels would constitute a fleet run by the CNO on plans for the fleet's operation developed by the Naval War Plans Division and the Joint Board.

Article XIX provided that with the exception of Hawaii, Alaska (not including the Aleutian Islands), and the Panama Canal area, America's Pacific islands were to remain militarily in status quo. Similar non-fortification provisions applied to the British and Japanese. The British could fortify nothing east of Hong Kong and the Japanese nothing outside of their home islands. 4 Article XIX proved to be critical in light of the General Board's,

--24--

the Joint Board's, and the ONI' s conclusions that the foreign policies of Japan were a threat to America's Far Eastern interests, namely the Open Door and the protection of the Philippine Islands.

The U.S. bases in the Pacific were vital to the war plans developed by the Joint Board that outlined the campaign against Japan in case of war between Japan-and the U.S., a plan code-named War Plan ORANGE. Under continuous revision until replaced by the RAINBOW-plans in 1939,. War Plan ORANGE was important to the General Board because the Board recommended warship design characteristics in light of the requirements set out by ORANGE.5 Article XIX affected ORANGE because the Article denied the U.S. Navy bases it needed to fulfill the objectives of the plan. There were no functional refueling or repair bases suitable for capital ships open to the U.S. after the Article went into effect.

Therefore, the Board always emphasized that each vessel be as self contained and as shell proof as possible. Each carrier, battleship, cruiser, and submarine also had to have a minimum cruising radius of at least 10,000 nautical miles. Such requirements were necessary because without bases in the Western Pacific, a vessel could not afford to be seriously crippled or run low on fuel before it met the Japanese fleet near the Philippines. The Joint Board revised the ORANGE Plan in 1928, and the U.S. Navy

--25--

operated under this version during the Hoover Administration.6

The Board also took exception to the Treaty because it believed that Great Britain and Japan engaged in an attempt to control the remaining unexploited natural resources: Great Britain on a world wide scale and Japan in the Far East. Therefore the Board argued that in order to protect U.S. interests, the Navy would need, at a minimum, parity with the Royal Navy and a two-to-one superiority over Japan "in order to have an equal opportunity in a conflict with either nation.7 Referring to the Treaty, the General Board stated: "from a naval position that then [pre-treaty] commanded the respect and attention of the World and was potentially the greatest, we have sunk to a poor second."8 The Board recommended that the U.S. should quickly build up to treaty standards, especially in the cruiser category.

The Treaty restricted carrier tonnage to 135,000 tons for the U.S. and Great Britain, 81,000 tons for Japan, and 60,000 tons for Italy and France. The Treaty limited carriers to a maximum tonnage of 27,000 tons per ship. Each nation could build two carriers of up to 33,000 tons each provided that total allowed tonnage was not exceeded. In consequence to the latter clause, two U.S. battle cruisers under construction at the time of the Washington Conference could be converted into aircraft carriers

--26--

instead of being scrapped. The U.S. Navy christened the carriers the Lexington and the Saratoga, and along with the previously converted collier Jupiter, re-named the Langley [also known as the "Covered Wagon"), began to initiate acceptance of naval aviation with the battle fleet.9

The Treaty restricted categories of warships other than capital ships to a maximum tonnage of 10,000 tons per vessel. The Treaty specified that such a vessel could not mount guns exceeding eight-inches in caliber. However, the Treaty did not restrict the size of the cruiser fleets of each nation and thereby opened the door for competitive cruiser building programs, programs that would lead the major powers to further limitation talks in Geneva and later in London.

Incorporated into the Treaty were a number of articles written by former Secretary of State and War Elihu Root that dealt with submarine warfare. Amended to the Treaty by the chief British delegate to the Conference, Lord Balfour, the articles were the result of the public outcry and abhorrence over the German U-boat's unrestricted war against the Allied commerce. The amended articles specified that merchant vessels "must be ordered" to submit to any search for contraband, all passengers and crew had to be "placed in safety" before their ship could be sunk, and if the rules could not be "observed," then the vessel "must be allowed to pass unharmed." The last article

--27--

specified that any person who disregarded the rules "would be held liable for an act of piracy."10 England, Japan, and the United States signed the submarine amendment on February 6, 1922.

While the General Board did not approve of the amendment, it, along with Japanese naval planners, viewed the submarine as a warship "killer" and not a commerce raider. Therefore the amendment did not affect U.S. submarine operations.11 Such views, coupled with public opinion in the U.S., led the Board and the members of the War Plans Division of the Office of the CNO to ignore the experiences of the German U-boats during World War I. The U-boat's campaign proved the effectiveness of commerce warfare against an island nation and that the submarine was the best weapon to carry out such a war. However, the U.S. Navy ignored the lesson taught by the U-boats and the naval planners from each nation developed their submarines to work with the battle fleet.

Soon after the close of the Washington Conference, then-Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur ordered the Board to develop a "Naval Policy" for the Department, a policy that would guide the planning and organization of the fleet. The Board came up with a five page document that began with the statement "The Navy of the United States should be maintained in sufficient strength to support its policies and its commerce, and to guard its

--28--

continental and overseas possessions."12 Under the heading of "General Naval Policy," the Board noted that the U.S. Navy must "create, maintain, and operate a navy second to none and in conformity with Treaty restrictions."13

The Board always referred to the policy in its recommended building programs, although Congress, the President, or the State Department, never officially recognized the policy. The real value of the policy lay in its clear statement of the Board's view of the role of the U.S. Navy and as a basis from which to base the Board's building programs. The Board also held hearings on the naval policy each year to determine if it met current international conditions. It remained virtually unchanged until the outbreak of. the World War II.

The U.S. Navy reorganized its fleet on December 6, 1922, to complement War Plan ORANGE. The U.S. Navy stationed the Battle Fleet, consisting of twelve battleships and the Lexington and the Saratoga, in the Pacific, thereby reflecting the view of the Board, the ONI, the CNO, and the Naval War College that the Imperial Japanese Navy was the primary concern of the U.S. Navy. The Navy also based the weaker Scouting Fleet in the Atlantic. The Navy also stationed a Control Force consisting of light cruisers and destroyers in the Atlantic, but replaced it in 1929 by a Submarine Force stationed in the Pacific. Operating independently of

--29--

either fleet were the Asiatic Fleet, Naval Forces Europe, Special Service Squadron, and Naval Transportation Service.14

As the Board noted in its report on the Washington Naval Treaty, the fleet's most serious deficiency lay in the lack of any heavy cruisers. Despite this weakness in cruisers, Congress did not authorize any new ones until Japan laid down six heavy cruisers and Great Britain five. The 1924 Cruiser Bill authorized the construction of eight 10,000 ton cruisers armed with eight-inch batteries on a design approved by the General Board. Because the U.S. Navy laid down only two heavy cruisers by 1927, the U.S. fleet had to rely on its Omaha class light cruisers to fill the growing cruiser gap between Japan, Great Britain, and the United States.15

Cruisers were essential in making the fleet "well balanced" because in a tactical role they supported the battle line against attack from enemy cruisers and destroyers and led U.S. destroyers in attacks on an enemy battle fleet. Strategically, the cruisers acted independently of the fleet as an advance scout, a commerce raider, and as a convoy escort. The Omaha class cruisers, armed only with six-inch guns, could not fulfill all of the required cruiser roles. Only the large, 10,000 ton, eight-inch gun cruisers could, according to the Board.16 As such, the Board only recommended heavy cruiser construction. Such recommendations led to difficulties at the next

--30--

naval limitation conference.

Although the United States was not a formal member of the League of Nations, an ambassador at large attended the League hearings that affected U.S. interests. The League's Preparatory Commission on Disarmament held hearings in the attempt to solve the problem of both naval and land arms limitation, and was one such conference attended by a U.S. representative. However, as the Commission made such little headway by 1927, President Coolidge extended invitations to Great Britain and Japan to meet in Geneva to discuss only the naval limitation problems, independently of the League. 17 Italy and France refused to attend any conference chat was not a part of the League, but Japan and Great Britain accepted the President's invitation.18

In March, 1927 SECNAV Curtis D. Wilbur instructed the General Board to study U.S. cruiser needs in relation to Great Britain, and Japan for the upcoming conference. The Board recommended a maximum total cruiser tonnage for the U.S. and Great Britain of no more than 400,000 tons and 240,000 tons for Japan, with each nation retaining the right to determine for itself the size of each warship and its gun caliber. The Board specified that the U.S. should reserve the right "to build cruisers appropriate to our 19 needs," namely, the 10,000 ton, eight-inch cruiser.19 The current emphasis on cruiser buildup should not, warned the Board, obscure the fact that the "battleship is the

--31--

ultimate measure of strength of the Navy and that anything that would tend to reduce that measure of strength would impair our national defense."20

The British had a different plan concerning cruisers.

They proposed to divide cruisers into two categories: heavy (10,000 ton, eight-inch guns), and light (6,000 ton, six-inch guns), with the number in each category to be fixed by agreement, a direct contrast to the U.S. proposal to fix only the total tonnage for each class. The Admiralty stated that Great Britain needed an absolute minimum of seventy cruisers, fifty-five light and fifteen heavy.21 On this point, the British were not open to negotiation, as Admiral of the Fleet John Jellicoe pointed out to the press:

On the outbreak of the Great War we possessed 114 cruisers, and in spite of the fact that Germany had only two armored cruisers, six light cruisers and four armed auxiliaries outside the North Sea, our losses in merchant ships due to the action of these German, vessels exceeded 220,000 tons.... Later in the war, three disguised German raiders accounted for 254,000 tons of British and 39,000 tons of allied shipping. If, under these conditions, 114 cruisers proved to be an inadequate number ... can it be said that 70 is now excessive?22

The seventy cruisers would weigh in at 500,000 tons, above the maximum limit set by the U.S. The insistence of the U.S. delegates, headed by Rear Admiral (hereafter referred to as RADM) Hilary P. Jones, a staunch supporter of the views advocated by the General Board, on parity with

--32--

Britain and the British insistence on a minimum of seventy cruisers led to the collapse of the Conference. The Japanese could do little more than stand by and observe the argument between the U.S. and Britain. The U.S. public and press thought that the conference failed because "the admirals were on top, rather than on tap."23

After the collapse of the Geneva Conference, the General Board recommended a comprehensive, five year building program that would build up the fleet on a 5:5:3 ratio in cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, including twenty-five 10,000 ton, eight-inch gun cruisers.24 But, or. February 13, 1929, Congress only authorized the construction of fifteen cruisers and one aircraft carrier, a program accepted by President-elect Herbert Hoover.25

Japan, by this time, completed the construction of four cruisers of the Furutaka class (9000 tons, 6 eight-inch guns), four Myoko class (10000 ton, 10 eight-inch guns) and laid down four Atago class cruisers (10000 ton, 10 eight-inch guns), while Great Britain completed five Kent class cruisers (10000 ton, 8 eight-inch guns), four London class (10000 ton, 8 eight-inch guns) and laid down two Dorsetshire class (10000 ton, 8 eight-inch guns) and two 26 York class (8400 tons, 6 eight-inch guns).26

During the summer of 1928, while Congress debated the naval construction bill. Great Britain and France announced that they had reached a compromise on naval disarmament.

--33--

The Anglo-French Naval Compromise of July 28, 1928, stipulated that the next disarmament conference held by the League would consider restrictions on four classes of warships: capital ships (warships displacing more than 10000 tons or mounting guns of more than eight-inch caliber); aircraft carriers in excess of 10000 tons; Surface vessels of or below 10000 tons armed with guns of more that six-inch caliber and up to eight-inch caliber; ocean-going submarines of over 600 tons. One should note the absence of the two vessels best suited for the special needs of the two nations: the Royal Navy's six-inch gun cruiser and the French Navy's coastal submarine.27

The British Government submitted the plan to Washington, D.C., Tokyo, and Rome, in the hope of obtaining their approval of the terms. Secretary of State Kellogg asked the Secretary of the Navy Wilbur to prepare the basis for an answer. Wilbur submitted the British request to the General Board and asked for its recommendations. The Board replied that exempting the six-inch gun cruisers from control "is comparable to the British position at Geneva 28 and constitutes, in effect, no limitation.28 As for the proposal concerning the submarines, the Board noted that such vessels could carry a torpedo "having a destructive power equal to those carried by larger submarines," and the unrestricted construction of these submarines "is a potential threat to the safety" of the U.S.29 As such, the

--34--

Board concluded that the Anglo-French agreement was unacceptable to the United States.30 The influence of the Board in this case is readily apparent as Wilbur's reply to Kellogg was a verbatim copy of the Board's report, and Kellogg's telegram to the British and French used both its 31 ideas and language in rejecting the proposal. 31

Ironically, the same Congress that passed the Fifteen Cruiser Bill also passed the Kellogg-Briand Pact which renounced war as an "instrument of national policy except as a means of defense" and pledged the contracting parties to settle all matters of controversy peacefully.32 The apparent contradiction in passing two diametrically opposed bills by the same Congress is best explained by the American Legion. The Legion endorsed the principle of the Kellogg-Briand Pact, however, since the pact in no way guaranteed peace, the Legion stated that no reduction should be made in the military establishment, and the U.S. should "certainly not" reduce its military forces by example in the hope that other nations would follow suit. The contradiction also exemplified the division of the general public and the influence of various pressure groups on Congress, including the Navy League.33 This then was the state of naval affairs as President Hoover entered office.

As a group, the General Board gave no notice of the changing Administration, nor gave any hint of the upcoming conflict between it and President Hoover. It presented its

--35--

recommended building program for the fiscal year of 1931 on April 4, 1929. The Board recommended that the U.S. begin modernizing its battleships (replacing coal burning with oil burning steam powerplants), lay down two battleships before the end of 1931, two 10,000 ton, eight-inch cruisers, four destroyer leaders, eleven submarines, one aircraft carrier, and one floating drydock. The Board also recommended that the U.S. continue the Five-Year Aircraft Program, authorized by Congress in 1926, that provided for the construction of 1000 aircraft by July 1, 1931. The Board concluded its recommendation by noting ^hat the construction of the previously authorized fifteen heavy cruisers and one aircraft carrier be continued.34

Perhaps in anticipation of a change of heart concerning naval construction by Congress or the new Administration, the Board, in its recommended building program, warned that the. shipbuilding industry in the U.S. was an "integral and essential" part of the nation's defense and noted that such an industry required "stability of operations" in order to maintain the technically qualified "specialists necessary to construct warships.35 The Board concluded its warning by noting that the recommended program would "help materially to conserve the shipbuilding industry, which is a strong factor in our national defense and prosperity."36 The Board typically included some statement in its recommended building

--36--

programs to help "sell" the program to the Administration and Congress, although not always successfully.

The Army and Navy Journal welcomed the new President and noted that his election: "brings satisfaction to many and no bitterness to any."37 Hoover, throughout his campaign in 1928, promised that his administration would "assure national defense."38 He was more specific in a speech given during October, 1928, when he stressed the need for a navy that would give "complete defense to our homes and from the fear of foreign invasion," a portent of his desire to have the Kellogg-Briand Pact become the cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy, a policy that would spell doom for big navy advocates who desired a fleet large enough to counter any 39 threat to all U.S. possessions.39

President Hoover supported a navy strong enough to defend the United States and the Western Hemisphere against attack and to make sure that "European and Asiatic aggressors would not even look in this direction."40 He regarded the Panama Canal as vital to the defense of the nation. He recognized that distant possessions like Guam, Samoa, and the Philippines, most in the Japanese sphere of influence, would be expendable in the event of war with Japan. The cost of insuring their protection would far exceed their value; besides, a sufficiently large navy to defend them would be a provocation to Japan.41

Hoover, in his Memoirs, noted that "I was not in favor

--37--

of the United States' permanently holding foreign possessions except those minor areas vital to our defense. Our mission was to free people, not to dominate them." He also made clear that he advocated freeing the Philippines, but not before they had "complete economic stability."42 Finally, he accepted the futility of attempting to shelter American commerce during wartime. He stated that his policies in "national defense and world disarmament" had one objective: "to insure freedom from war to the American people." 43

Hoover's policies contrasted markedly to the Naval Policy, modified by the Board in 1928. The Board's policy advocated maintaining the "Open Door" in China, protecting U.S. interests in Asia, and one that defined the Philippines as being vital to U.S. interests. 3eyond the stated policy, the General Board believed that Japan would be the next enemy, and based on War Plan ORANGE, advocated a fleet that would meet the objectives stated by the War Plan.44 The battle lines between the General Board and their Commander-in-Chief had been drawn.

The U.S. Navy, as a whole, approved of Hoover's selection of the Treasurer of Harvard University, Charles F. Adams of Massachusetts, as the SECNAV. The Army and Navy Journal praised Hoover's choice and stated that it expected Adams to be a "seagoing secretary whose personality, approachability, and interest in the Navy will make

--38--

him a favorite in the Service."45 Adams, Hoover hoped, would fulfill what Hoover deemed as the five essential qualities he desired in his appointees, including: rigid integrity, public esteem, sympathy with the ideas of the President, general efficiency, and success as an administrator.46 Time magazine correctly predicted that although Adams may have been popular among naval officers, the President expected him to stand firm against the Admiral's demands and instead be "responsive" to Hoover.47

The post of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, although created in 1862, had only been continuously filled since 1890. At first, the principal justification for the position was to provide a civilian of appropriate rank to substitute for the SECNAV in his absence. Eventually, the Assistant Secretary also managed civilian personnel and also the shore establishment.48 Hoover's choice of Ernest Lee Jahncke of New Orleans literally "came out of the blue," and no one is sure who recommended him or why Hoover chose him. Perhaps Hoover's appointment was a reward to the South for its support in the 1928 election.49 Jahncke became close friends with Hoover and played medicine ball with Hoover and the President's closest advisors each morning. Jahncke denounced the League of Nations as a "political monstrosity" and irked many naval officers by his request that they call him "Commodore," a title that he signed all of his correspondence.50

--39--

Hoover's appointment of David S. Ingalls of Ohio, the husband of the heiress to the Standard Oil fortune, as the Assistant Secretary for Aeronautics gratified advocates of naval aviation such as RADM William A. Moffett. As the Navy's only "ace" in the World War, Ingalls was a staunch advocate of naval aviation.51

During March and April, 1929, Hoover appointee RADM Charles B. McVay as the Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet and Vice Admiral Louis M. Nulton as the Commander in Chief of the Battle Fleet. Directly under Nulton Hoover appointed RADM L.A. Bostwick as the Commander of the Battleship Division of the Battle Fleet and Admiral William V. Pratt as the Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet.52

The roster of the General Board remained unchanged and included as an ex-officio member The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral C.F. Hughes. The Chairman of the Board was RADM Andrew T. Long (United States Naval Academy Class of 1887, hereafter referred to as Class of 1___) and the other members of the Board included RADMs: R.H. Jackson (Class of 1894), J.V. Chase (Class of 1890), H.H. Hough (Class of 1891), G.C. Day (Class of 1892), J-M. Reeves (Class of 1894), and ex-officio member and head of the Naval War College J.R.P. Pringle (Class of 1894). Also on duty with the Board were ex-officio member Major General W.C. Neville, Commandant of the United States Marine Corp, Medal

--40--

of Honor winner (Class of 1892), Captain A.W. Johnson (Class of 1897) and the Secretary of the General Board Commander R.L. Ghormley (Class of 1906).53

One of the first tasks the new Administration ordered the General Board to accomplish was to reassess the U.S. need for cruisers. The General Board's report, reeking of Mahan's theories, stated that the demand for cruisers from "every strategical and tactical point of view is urgent."54 The lack of cruisers in the fleet "constitutes the Navy's greatest weakness today."55 The report then-emphasized the "vital" role cruisers played in protecting U.S. trade. The Board concluded by noting:

If our prosperity is to continue, our merchants and manufacturers must not only hold the foreign markets we have gained, but, as European conditions return to normal, we must seek new markets for their output. Showing the flag has a very marked influence upon their endeavors, and the measure of their success is influenced in no small degree by the prestige which up-to-date and smart looking cruisers create and foster.

This reference to international economics is commonly found in reports prepared by the Board, even though none of the Board members held a degree in economics or worked in any manufacturing or production enterprises. The argument that economic expansion required fleet expansion was obviously influenced by Mahan's theories of seapower which were emphasized in the officers' Annapolis and Naval War College education.57 Yet President Herbert Hoover did not share this view, and as a portent of future affairs, he ordered the

--41--

Presidential Yacht Mayflower decommissioned "as a small contribution to economy in the face of our greatly increased expenditures.58

--42--

ENDNOTES

1. The actual capital ship ratios worked out to 5:5:3 for the three major powers: Great Britain, the United States, and Japan, respectively.

2. General Board Report, No. 438, Serial No. 1088-A, 17 September, 1921, Records of the General Board (hereafter RGB), Record Group 80 (hereafter RG 80), National Archives (hereafter NA).

3. Greene, "The Military View of American National Policy," pp. 354-35*6.

4. Paolo E. Coletta, ed., The American Naval Heritage (New York: Lanham, 1987), pp. 269-270.

5. Morton, Strategy and Command, p. 71; Jeffery M. Dorwart, The Office of Naval Intelligence (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1979), pp. 48-52. War games were conducted against the major naval powers, and each was given a color code-name. The U.S. was BLUE, Great Britain RED, and Germany BLACK. It should also be noted that the Board never mentioned Germany as a potential adversary during its hearings held during Hoover's Administration.

6. Morton, "War Plan Orange," p. 233.

7. Raymond G. O'Conner, Perilous Equilibrium: The United States and the London Naval Conference of 1930 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1962), pp. 5-6.

8. General Board Report, No. 420-2, Serial No. 1162, 7 April, 1923, RGB, RG 80, NA.

9. James H. and William M. Belote, Titans of the Seas, The Development and Operations of Japanese and American Carrier Task Forces During World War II (New York: Harper and Row, 1975), p. 15.

10. Richard D. Burns, "Regulating Submarine Warfare, 1921:41: A Case Study in Arms Control and Limited War," Military Affairs,: XXXV.(April. 1971), p. 57.

11. Ernest Andrade, Jr., "Submarine Policy in the United States-Navy, 1919-1941," Military Affairs, XXXV (April, 1971), p. 55.

--43--

12. General Board Report, No. 420-2, Serial No. 1108, 1 December, 1922, Presidential Papers, OF 18m-Navy, HHPL.

13. Ibid.

14. Coletta, Naval Heritage, p. 282.

15. Ibid; The Omaha class light cruisers, the only modern cruisers in the U.S. Navy, were completed by 1924.

16. Hearings Before the General Board (hereafter HGB), "10,000 Ton Treaty Cruiser," 27 November, 1929, Microfilm (Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1983), pp. 404-405.

17. The League wanted the major powers to accept the French approach of "global tonnage" whereby a nation's fleet would be limited as a whole; the U.S., on advice given by the General Board, wanted limitation by class of warship.

18. Italy and France later agreed to send "observers" to the conference. Coletta, Naval Heritage, p. 271.

19. General Board Report, No. 438-1, Serial No. 1408, 23 February, 1923, RGB, RG 80, NA.

20. Ibid.

21. Armin Rappaport, The Navy League of the United States (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1962), p. 109.

22. As quoted in: U.S. Congress, Senate, Foreign Relations Committee, Records of the Conference for the Limitation of Naval Armament, June 20 to August 4, 1927, Document No.. 55, 70th Congress, 1st Session (Washington, D.C.: USGPO), p. 43.

23. David M. Masterson, ed., Naval History: The Sixth Symposium of the U.S. Naval Academy (Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1987), p. 272; William F. Trimble, "Admiral Hilary p. Jones and the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference," Military Affairs, XLIII (February, 1979), pp. 1-4. The delegates did agree on submarine and destroyer tonnage limits, limits that would be accepted at the London Conference in 1930.

24. General Board Report, No. 1367, Serial No. 1420-2, 31 December, 1927, RGB, RG 80, NA.

25. The authorization included a clause that

--44--

encouraged further international limitation and permitted the President to suspend further construction in the event of such limitations. O'Conner, Perilous Equilibrium, p. 22.

26. Coletta, Naval Heritage, p. 195.

27. O'Conner, Perilous Equilibrium, p. 21.

28. General Board Report, No. 438, Serial No. 1390, 11 September, 1928, RGB, RG 80, NA.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. O'Conner, Perilous Equilibrium, p. 21. Japan did not reject the plan, and Italy's response was negative because it insisted on parity with France and expressed her preference for the global tonnage method.

32. Ibid., pp. 22-23.

33. The Navy League was formed in January, 1903, to "educate the public and arouse interest in the Navy," by lectures, pamphlets, and by the publication of a League magazine. Rappaport, The Navy League, pp. 4-5.

34. General Board Report, No. 420-2, Serial No. 1415, 5 April, 1929, RGB, RG 80, NA.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Army and Navy Journal, November 10, 1928, p. 1.

38. Ibid.

39. Wilson, "Herbert Hoover," p. 175.

40. Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover, The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920-1933, vol. II (New York: Macmillan, 1951-52), p. 338.

41. Wilson, "Herbert Hoover," pp. 33-34.

42. Hoover, Memoirs, p. 359.

43. Ibid., p. 338.

44. U.S. Congress, Senate, Foreign Relations Committee, Hearings on the Treaty on the Limitation of

--45--

Naval Armaments, 71st Congress, 2nd Session, 1930 (Washington, D.C., USGPO, 1930), p. 233; hereafter Foreign Relations Committee, Hearings on the Treaty.

45. Army and Navy Journal, March 9, 1929, p. 549. Adams was the direct descendant of two presidents. He was well known among naval circles as in 1920, he skippered the racing Yacht Resolute in the America's Cup Race and defeated Sir Thomas Lipton's Shamrock IV. Until the election of 1920 he had been a registered Democrat, but switched tickets that year. Ibid.

46. Hoover, Memoirs, pp. 54, 217-218.

47. Time, March 11, 1929, p. 48.

48. RADM Julius A. Furer, Administration of the Navy Department in World War II (Washington, D.C.: USGPO, 1959), p. 54.

49. Adams recommended F. Trubee Davidson, the Assistant Secretary of War for Aeronautics and Thomas C. Desmond, a prominent New York Republican, Wilson, "Herbert Hoover," p. 39.

50. Ibid., p. 40. His title was bestowed upon him by the New Orleans Yacht Club and was not an official rank in the U.S. Navy.

51. Ibid.

52. Telegrams, Herbert Hoover to naval officers named. Presidential Papers, OF 18m-Navy, HHPL.

53. Note from CMDR. Ghormley to Bristol, 4 October, 1929, Official Correspondence, Bristol Papers, LC; Register of the Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps, 1929 (Washington, D.C.: USGPO, 1930).

54. General Board Report, No. 420-2, Serial No. 1415, 4 April, 1929, submitted to SECNAV Adams, RGB, RG 80, NA.

55. Ibid.

56. Ibid.

57. Peter Karsten, in his study of naval officers, concluded that "Naval officers might think what they liked about their duties, but the primary result of their labors was to aid American businessmen abroad." Peter Karsten, The Naval Aristocracy: The Golden Age of Annapolis and the

--46--

Emergence of Modern American Navalism (New York: Free Press, 1972), p. 268.

58. Letter from Hoover to Captain Allen Buchanan, March 22, 1929, Presidential Papers, OF 18m-Navy, HHPL. The ex-C.O. of the Mayflower, Captain Buchanan, was then appointed as a naval aid to Hoover.

--47--

CHAPTER THREE

PRE-CONFERENCE NEGOTIATIONS

The Washington Naval Treaty restricted the total tonnage of the capital ships of Great Britain, Japan, and the United States, but did not restrict the size of the cruiser fleets of each nation, and competitive cruiser construction between the three countries ensued. The desire of the United States and Great Britain to eliminate their competitive cruiser construction led to the failed Geneva Conference of 1927, and to President Hoover's efforts to organize another naval limitation conference during 1929. This chapter will review not only Hoover's attempts to bring about a new naval conference in which the great naval powers would participate but also the part played by the General Board in guiding Hoover's efforts.

In his inaugural address to the nation. President Herbert Hoover outlined the objectives of his foreign policy. His primary objective was to control international tensions brought about by military and naval expansion by promoting arms limitation negotiations between the major powers. He noted: "Peace can be promoted by the limitation of arms and by the creation of instrumentalities for peaceful settlement, of controversies."1 Hoover believed

--48--

that large armies and navies were wasteful and counter productive in a democracy; he hoped that the power and influence of the U.S. could, through cooperation with the League of Nations and the World Court, play a beneficial part in reducing the size of such armaments and thereby improve international relations.2

The topic of disarmament was not new to the delegates who attended the League of Nation's Fifth Preparatory-Commission of the Committee on Disarmament. Five times the delegates struggled with the issues, national prejudice, fear, and mutual suspicion in order to draft plans for a general disarmament conference, and five times since 1925 they failed. The General Board recommended that the U S. send a representative to the Commission, even though the U.S. was not a member of the League. However, the Board advised that the U.S. should abstain from any informal discussions on the reduction of battleship, tonnage, a proposal presented by the British that would reduce the then maximum limits as specified by the Washington Treaty, at 35,000 tons displacement and 16-inch caliber guns.