The Navy Department Library

U.S. Navy Forward Deployment 1801-2001

U. S. Navy Forward Deployment 1801-2001

Peter M. Swartz and E. D. McGrady

Center for Strategic Studies

Alexandria, Virginia,

4825 Mark Center Driver,

223-1850,

(703) 824-2000

The Center for Strategic Studies is a division of The CNA Corporation (CNAC). The Center combines in one organizational entity regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategic and force assessment work. Such a center allows CNAC to join the global community of centers for strategic studies, and share perspectives on major security issues that affect nations.

There is a continuing need for analytic and assessment work that goes beyond conventional wisdom. The Center for Strategic Studies is dedicated to providing a deeper level of expertise, and work that considers a full range of plausible possibilities, anticipates a range of outcomes, and does not simply depend on straight-line predictions.

Another important goal of the Center is to attempt to stay ahead of today's headlines by looking at "the problems after next," and not fall into the trap of simply focusing on analyses of current events. The objective is to provide analyses that are actionable, and not merely commentary.

A principal activity of the Center is a Washington-area workshop and roundtable program that explores a wide range of issues. This program seeks to have subject experts meet with other experts and policy practitioners in non-attribution sessions to explore various aspects of U.S. security policy. This report is the product of one such workshop.

While the Center's charter does not exclude any area of the world, Center analysts have clusters of proven expertise in the following areas:

* The full range of East Asian security issues, especially those that relate to the rise of China

* Russian security issues, based on ten years of strategic dialogue with Russian institutes

* Maritime strategy

* Future national security environment and forces

* Strategic issues related to the Eastern Mediterranean region

* Missile defense

* Latin America, including guerrilla operations

* Operations in the Persian (Arabian) Gulf

The Center is under the direction of Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.), who is available at 703-824-2614 and on e-mail at mcdevitm@cna.org. The administrative assistant for the Center is Ms. Michele Treese, at 703-824-2833.

Approved for Distribution June 2001

This document is derived from Appendix A of Peter M. Swartz and E.D. McCrady, A Deep Legacy: Smaller-Scale Contingencies and the Forces that Shape the Navy (Alexandria VA: Center for Naval Analyses, CRM 98-95.10/ December 1998). Accordingly, it represents the best opinion of the CNA Corporation at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Deep Legacy also addressed historical models of U.S. Navy organization, procurement and employment, as well as deployment.

Peter M. Swartz

Director, International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies

Distribution unlimited. This document is approved for public release.

Introduction

The U.S. Navy today often sees itself almost exclusively as an extension of the Navy of the Cold War. This is understandable: the Cold War lasted for over four decades. That long period saw the formative experience of the current generation of naval officers and their civilian colleagues. Not only that, it also was the predominant experience of the generation that served before them, and that educated and trained today's Navy.

The Cold War, however, was a unique period, with a set of special characteristics that may or may not apply to current and future environments. Also, the Cold War is not the only legacy the current and future U.S. Navy has. The Navy had been many places and done many things before 1945 - indeed, before 1845. To the extent the Navy looks to past experience as one input to guide future decisions, it may well be able to draw on its earlier history - what we call its "Deep Legacy" - as much as if not more than its more recent Cold War experience.

Deployment policy

A significant operational driver for the current post-Cold War fleet is the particular general deployment policy the U.S. Navy has maintained since just after World War II. For decades, an almost continuous Carrier Battle Group (CVBG) and Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) presence has been maintained in the three "hubs" of the Far East, the Persian Gulf region, and the Mediterranean - locked and loaded and ready for anything. This requires considerable resources and drives the training and outlook of almost everyone in the Navy1.

The fleet has not always rotationally deployed to hub stations, however. It has not always been ready for high-intensity or mid-intensity warfighting. Nor has it always been ready for participating in Smaller-Scale Contingency (SSC) operations or (Operations Other Than War) OOTW.

___________

1. The Western Pacific hub dates back to World War II and before. The Mediterranean hub had its beginnings in the late 1940s. The Persian Gulf/Indian Ocean hub originated later, in the 1970s.

--1--

What forces have caused the Navy to adopt particular ways for deploying its forces around the world? More fundamentally, what are the models the Navy has used throughout its history for deploying forces?2

Models

If you look at the history of the U.S. Navy you find that the fleet has deployed according to five major models:

1. Model I: Combat surge

- ships and squadrons held near the continental United States (CONUS)

- fleets ready to surge against enemy ships and installations

- little or no SSC operations and OOTW

2. Model II: Combat forward

- ships and squadrons stationed forward

- primary focus is defeating an enemy fleet in high-intensity or mid-intensity war

- little or no SSC operations or OOTW

3. Model III: Contingency forward

- ships and squadrons permanently stationed forward

- primary focus on SSC operations and OOTW

- little or no focus on high-intensity or mid-intensity warfare

4. Model IV: Multi-mission and multi-area, separate fleets

- forward-deployed contingency squadrons, combat fleet held at CONUS

___________

2. Historically derived models are not the only models that can be used to analyze Navy deployments. For an alternative typology, see "Forward Presence" in ADM J. Paul Reason, USN, with David G. Freymann, Sailing New Seas (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 1998).

--2--

- colonial-type missions dominate for forward forces

- CONUS forces focus on preparation for high-intensity fleet actions

- CONUS forces seldom if ever surge in peacetime

5. Model V: Multi-mission and multi-area, mixed fleets

- battle fleets both forward and in CONUS

- all fleets capable of doing any mission, contingency, or war-fighting

In the next five sections we describe each of these major models in detail.

Model I: Combat surge

During its early years, from roughly 1798 to 1806, the U.S. Navy was primarily designed to do one mission: mid- and high-intensity war-fighting. It was built and maintained almost solely to fight the British, the French, the Spanish, and/or the Barbary States, should war between any of them and the United States threaten. In actual fact, the Navy did fight the French in the Caribbean and the Barbary States (Tripoli) in the Mediterranean, and prepared to fight the British in the Atlantic and elsewhere.3 Warfighting was usually in one-on-one engagements rather than squadron or fleet actions. Nevertheless it pitted sophisticated U.S. Navy warships against equally high-end or almost high-end naval opponents. Figure 1 shows Navy deployment during this period and after, from 1798 to 1815.

As an almost single-mission fleet, the U.S. Navy was designed to carry out major contingency combat operations against warships and forts of large and medium powers. It also worked to train for these missions.

____________

3. It continued to prepare to fight these powers from 1807 to 1815, and actually fought Barbary States again (this time they were Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli) and Britain (in the War of 1812); in this latter period, however, the warfighting fleet co-existed with an SSC/OOTW fleet, as discussed below.

--3--

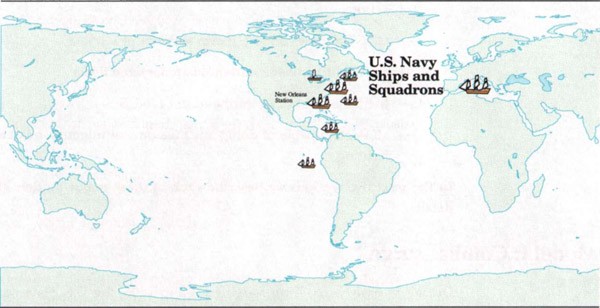

Figure 1. U.S. Navy deployment, 1789-1815

There was little or no preparation for SSC operations or other forms of OOTW.4

Table 1 shows the core missions for the deployments illustrated in figure 1. In the table, and all subsequent figures in this series, SSC and OOTW missions are shaded.

The fleet during this time was held near CONUS and expected to surge when conducting operations.

____________

4. Characteristics of the era are summarized in G. Terry Sharrer, "The Search for a Naval Policy, 1783-1812," in Kenneth J. Hagan (ed.), In Peace and War: Interpretations of American Naval History, 1775-1984 (Second Edition), (Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1984), 27-45. On the origins of the U.S. Navy and its initial forward warfighting experiences in the Caribbean and elsewhere, see Michael A. Palmer, The Quasi-War and the Creation of the American Navy, 1799-1801 (Columbia SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1987)

--4--

Table 1. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1789-1815

| Important deployed units | Core missions | ||

| Mediterranean Squadrons | Mid-intensity warfare in the Mediterranean: - To deter/combat Barbary States |

||

| Ships & Squadrons deployed to Eastern Atlantic & Caribbean |

Mid- and High-intensity warfare: - To deter/combat France, Britain, Spain |

||

| Frigate deployed to Pacific | High-intensity cruising warfare in the Pacific: - To combat Britain |

||

| New Orleans Station (after 1806) |

SSCs/OOTW in and around Louisiana: - To deter/combat pirates, smugglers, ex-slaves, Indians To deter/combat Spain/Britain |

This posture had a rationale: During this time, the United States was a medium-sized naval power in an era when there were several large and medium-sized naval powers all constantly engaged in warfare all around the world. The country's interests were national survival and protection of commerce in an era when that commerce was chiefly threatened by other large and medium powers. SSC operations and OOTW missions seldom had much importance.

Model II: Combat forward

This is the ultimate mid/high-intensity warfighting Navy. During the Civil War and World War II, when the United States had a large fraction of its national attention and effort involved in high-intensity warfighting, it deployed its fleets to the enemies' shores. In the case of the Civil War this was not far from the United States, but it was still forward (i.e., it was not arrayed defensively off New England or New York). During World War II, fleets deployed at great distances from the United States. Once the fleets deployed, they did not rotate.

--5--

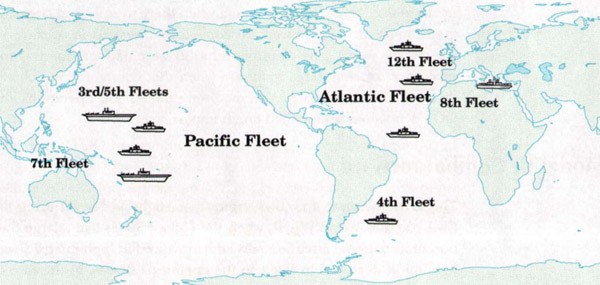

Figure 2 shows an example of major U.S. Navy fleet deployments during the middle phases of World War II.

The fleets' missions were to conduct combat operations against enemy fleets and enemy forces ashore. They were deployed as squadrons or fleets (vice single ships). There was almost no participation in SSC or OOTW during this time (an exception was U.S. Navy participation in a European coalition operation in Japan during the Civil War).

Table 2 shows the reasons the fleets pictured in figure 2 were deployed as they were. In this model the fleets were almost exclusively used in high-intensity warfighting missions.

Figure 2. U.S. Navy deployment, 1943-1945

Why was the fleet was deployed like this?

During these years there were relatively short periods of intense naval and amphibious warfare where the stakes were seen to include national survival. The focus of national attention on high-intensity

--6--

Table 2. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1943-1945

| Important deployed units | Core missions | |

| 3rd/5th Fleets Pacific Fleet Task Forces |

High-intensity warfare in the North, Central, South and Southwest Pacific: To combat and defeat Imperial Japan, jointly with the U. S. Army |

|

| 4th, 8th, 12th Fleets Atlantic Fleet Task Forces Sea Frontier Task Forces |

High-intensity warfare in the North and South Atlantic and Mediterranean: To combat & defeat Nazi Germany alongside the Royal Navy, and supporting the U. S. & British armies |

warfighting just about excluded either SSC operations or OOTW from any significant role as naval missions.

Model III: Contingency forward

If the previous model was the ultimate warfighting navy, this model is the ultimate contingency navy. In this model the Navy also had one mission, but now it was SSC operations and OOTW against third-rate powers and entities, not high-intensity warfighting.

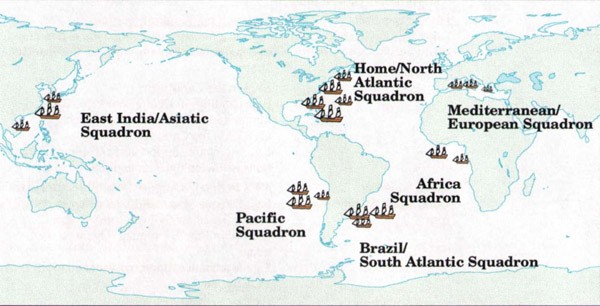

In order to be oriented toward SSC operations and OOTW, the Navy was made up of permanent squadrons forward deployed. These squadrons were focused on conducting SSC operations and OOTW in their region. Figure 3 shows generally where the major squadrons were deployed during the 19th century.

Warfighting, however, was not dropped entirely from the Navy's missions. If the squadrons were called on to fight a major or medium power, they would coalesce - with little or no preparation - into larger ad hoc entities. (Examples of wars where the Navy did coalesce include the Mexican, Civil, and Spanish American Wars, plus a couple of war scares.) This form of forward contingency operations combined with an ad hoc warfleet represents most of the fleet deployment design during the 19th century.

--7--

As shown in figure 3, the Navy for most of this period maintained stations in the North and South Atlantic and the North and South Pacific, as well as the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, the Western Pacific, and off West Africa. 5

Table 3 gives some of the reasons for these fleet and squadron deployments.

Why was the fleet deployed like this?

There were no major threats to the country (or to most countries) during this period. For example, the U.S. did not fight a major European power for the century-long period between 1815 and 1917. It was generally a "long peace" among large and medium powers, punctuated by a few bilateral, localized wars (e.g., the Mexican War) and war scares. The interests of the country at sea were mostly expansion and protection of commerce. The threats to that commerce during this period were largely from pirates and weak, third-world states.6

____________

5. The best short analysis of this 19th-century "cruising Navy" is Robert Greenhalgh Albion, "Distant Stations," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 80 (March 1954), 265-273. See also Stephen S. Roberts, An Indicator of Informal Empire: Patterns of U.S. Navy Cruising on Overseas Stations, 1869-1897, September 1980 (CNA Professional Paper 295).

6. In theory, and in the minds of naval officers of the period, the overseas cruisers could be called together to form fleets to operate against a second-tier adversary with a fleet at the lower end of the high-intensity warfare capability spectrum-such as Spain. This happened briefly during a war scare in 1873, and for real in 1898.

--8--

Figure 3. U.S. Navy deployment, 1841-1860 and 1865-1898

Table 3. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1841 -1860 and 1865-1898

| Important deployed units | Core missions | |

| East India Squadron Later, Asiatic Squadron |

SSCs in East Asian kingdoms and empires: E.g.: Sumatra, Fiji, China, Japan, Okinawa, Formosa & Korean Expeditions and landings OOTW throughout the Western Pacific: E.g.: Missionary, consular & merchant support, showing the flag, anti-piracy operations |

|

| Pacific Squadron | SSCs in the Eastern Pacific: E.g.: Indian War support at Seattle, Hawaii landings, intervention and war scare with Chile OOTW in the Eastern Pacific: E.g.: Merchant and consular support, Alaskan civil government support, showing the flag, exploration and surveying |

--9--

Table 3. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1841-1860 and 1865-1898 (continued)

| Important deployed units | Core missions |

| Home Squadron Later, North Atlantic Squadron |

Mid- and high-intensity warfare: To form a nucleus warfighting force, if required, to deter/combat Britain, Mexico, Confederacy, Spain SSCs in the Caribbean: E.g.: Landings in Central America, Trinidad humanitarian fire-fighting operation OOTW in the Caribbean: E.g.: Merchant support and anti-piracy operations, showing the flag, exploration of Isthmus |

| Brazil Squadron Later, South Atlantic Squadron |

SSCs in Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay: |

| Africa Squadron | OOTW in West Africa: E.g.: Anti-slaver ops with the Royal Navy, missionary & merchant support, nation-founding support in Liberia |

Mediterranean Squadron |

SSCs in the Mediterranean: E.g.: Incident with Austrian Navy brig off Smyrna, landing in Egypt OOTW in the Mediterranean: E.g.: Missionary & merchant support, consular support, showing the flag |

Model IV: Multi-mission and multi-area, separate fleets

The United States occasionally maintained separate fleets for high-intensity warfighting and SSC/OOTW.

It began to do so in the period 1806-1815. A high-intensity warfighting fleet of frigates and smaller warships was maintained as was described above in Model I. After 1806, however (three years after the Louisiana Purchase), that fleet co-existed with a small flotilla of gunboats and other shallow-draft vessels on the New Orleans Station. This small station - well out of the mainstream of the regular Navy - intimidated or fought insurrectionists, smugglers, slavers, and pirates. It

--10--

continued its OOTW even during the War of 1812, when the rest of the fleet was busy fighting the major naval power of the day.7

As the 19th century drew to a close and great power competition heated up, this model for fleet employment re-emerged. It would be a model for fleet employment used both prior to World War I as well as before and immediately after World War II. This model had a main battle fleet stationed in CONUS and ready to surge against an enemy battle fleet, plus smaller outlying forces optimized for OOTW.

Figure 4 shows the fleet deployments for one of these periods, 1922-1937.8 Table 4 gives some of the reasons why the fleets were deployed to these stations. During this time, most of the U.S. battle fleet was stationed on the western coast of the United States, preparing solely for high-intensity warfare.9

___________

7. See Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession: The Creation of the U.S. Naval Officer Corps, 1794-1815 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 306-308, 310.

8. There is a large literature on the interwar fleet. See especially Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991). For an important recent treatment, see Norman Friedman, Thomas C. Hone, and Mark Mandeles, American & British Aircraft Carrier Development, 1919-1941 (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1999).

9. During the Theodore Roosevelt presidency, the battle fleet was stationed on the East Coast and was used to surge forward - even around the world - in response to changing political and military situations. See Seward W. Livermore, "The American Navy as a Factor in World Politics, 1903-1913", The American Historical Review, LXIII (July 1958), 863-879; and James R. Reckner, Teddy Roosevelt's Great White Fleet (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988). For the immediate post-World War II change in the Atlantic, see Peter M. Swartz, "In My View...'The Navy's Search for a Strategy, 1945-1947'", Naval War College Review XLIX (Spring 1996), 102-108. See also Michael A. Palmer, Origins of the Maritime Strategy: American Naval Strategy in the First Postwar Decade (Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1988).

--11--

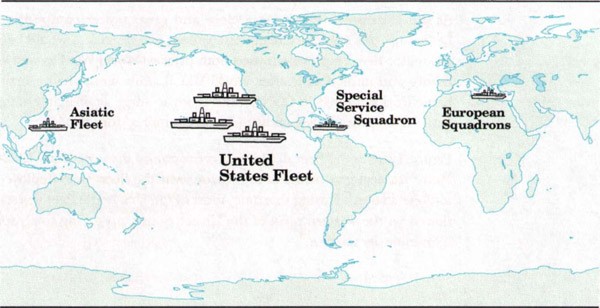

Figure 4. U.S. Navy deployment, 1922-1937

At the same time the country's need to engage in SSC operations continued, resulting in a few residual forward-deployed squadrons to conduct regional SSC operations: A Special Service Squadron - the so-called "Banana Fleet" - operated in the Caribbean and along the Central American coasts.10 An Asiatic "Fleet," including a Yangtze River Patrol, operated in and around China and the

____________

10. See Richard Millett, "The State Department's Navy: A History of the Special Service Squadron, 1920-1940," The American Neptune (April 1975), 118-138; and Donald A. Yerxa, "The Special Service Squadron and the Caribbean Region, 1920-1940: A Case Study in Naval Diplomacy," Naval War College Review, 39 (Autumn 1986), 60-72.

--12--

Table 4. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1922-1937

| Important deployed units | Core missions |

| United States Fleet | High-intensity warfare in the mid or Western Pacific: Exercises off Hawaii or Panama to deter/prepare to combat & defeat the Imperial Japanese Navy Minimal ad-hoc OOTW: E.g.: One show-the-flag deployment to Australia and New Zealand, CV electricity generation support to Tacoma, Los Angeles earthquake humanitarian support |

| Asiatic Fleet (Including Yangtze River Patrol) |

SSCs in China and the Philippines: E.g.: Interventions and landings in Chinese ports; Philippine colonial counter-insurrection operations OOTW throughout the China Seas and their littorals: E.g.: Showing the flag (especially in Japan & viz a viz the Japanese & British), protecting merchants & missionaries |

| Special Service Squadron |

SSCs in Mexico, Central American & Caribbean Republics: At the behest of the State Department: interventions, NEOs and humanitarian operations OOTW in Mexico, Central American & Caribbean Republics: E.g.: Showing the flag, civil and military government support, Chile-Peru peace-making support |

| Naval Detachment Turkish Waters, later Naval Detachment Eastern Mediterranean |

SSCs in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea: E.g.: Russian Black Sea and Greek Asia Minor NEOs OOTW in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea: E.g.: Showing the flag, protecting missionaries and merchants, diplomatic representation |

| Squadron 40(T) | SSC operations off Spain: Protecting/evacuating U. S. nationals during the Spanish Civil War |

--13--

Philippines.11 Various ad hoc squadrons conducted operations in European waters.12

This meant that the whole fleet was multi-mission, but that the individual fleets were separated according to whether they were the battle fleet or primarily designed to conduct SSCs and OOTW.13 During these times the Navy also did a complex form of OOTW ashore: civil government of certain U.S. possessions.14

____________

11. On China, see Stephen S. Roberts, The Decline of the Overseas Station Fleets: The United States Asiatic Fleet and the Shanghai Crisis, 1932, November 1977 (CNA Professional Paper 208); CAPT Bernard D. Cole, USN, Gunboats and Marines: The United States Navy in China, 1925-1928 (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1983); and RADM Kemp Tolley, Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1971).

12. For the various European SSC/OOTW squadrons, see Adam Siegel, "The Tip of the Spear: The U.S. Navy and the Spanish Civil War," unpublished paper, 1992; A.C. Davidonis, The American Naval Mission in the Adriatic, 1918-1921 (Washington, DC: Navy Department, Office of Records Administration, September 1943); Henry P. Beers, U.S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia (Archangel and Murmansk), 1918-1919 (Washington, DC: Navy Department, Office of Records Administration, November 1943); and ibid, U.S. Naval Detachment in Turkish Waters, 1919-1924 (Washington, DC: Navy Department, Naval Historical Center, 1940)

13. For a detailed but easily digested order of battle for each of these elements as of 1939, see James C. Fahey, The Ships and Aircraft of the United States Fleet (reprint edition) (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1978), 28.

14. On the U.S. Navy's civil and military government operations, see CAPT J.A.C. Gray MC, USN, Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and Its United States Naval Administration (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1960); Dr. Henry P. Beers, American Naval Occupation and Government of Guam, 1898-1902 (Washington, DC: Navy Department Office of Records Administration, March 1944); and a massively detailed, three-volume study, LCDR Dorothy E. Richard, USN, United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1957).

--14--

The rationale for this deployment posture was as follows: The naval powers of the world in these eras mostly subscribed to concepts of the importance of main battle-fleet battles at sea.15 SSCs and OOTW were clearly in second place. Nevertheless, the U.S. (and other nations) had colonial and other responsibilities they could not neglect. So the Navy - with some reluctance - sliced off little pieces of the fleet to do SSC operations and OOTW, often under the direct orders of the State Department or the Navy Department acting in its capacity as an agent of U.S. imperialism or colonial administration. The main battle fleet remained at home, to surge out to fight whomever the enemy proved to be.16

Model V: Multi-mission and multi-area, mixed fleets

This model has all the fleets ready to conduct any mission (multi-mission). They conduct peacetime OOTW and SSC operations, as well as mid- and high-intensity combat with the same ships and organizations.

____________

15. These concepts have traditionally been referred to as "Mahanian," after Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan. Mahan had much to say about warfighting and little to say about SSCs, OOTW and forward presence. See, for example John B. Hattendorf (editor), Mahan on Naval Strategy: Selections from the Writings of Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991); and John Tetsuro Sumida, Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command: The Classic Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan Reconsidered (Baltimore, MD: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1997). For a magisterial extended argument that a Mahanian model characterized U.S. Navy strategy for a century - but no longer - see George W. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990 (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1994).

16. For a discussion of the relationships between forward deployment and innovation, using the example of the interwar battle fleet experience, see Tom Hone, 'The Navy's Dilemma," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (April 2001), 75-78.

--15--

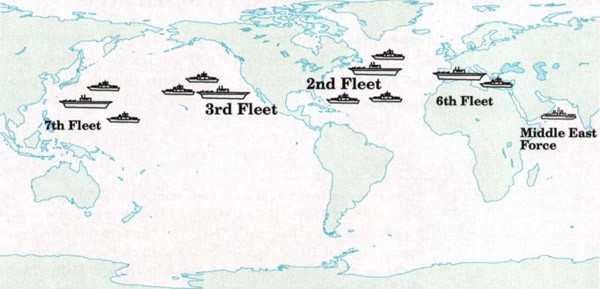

To do this variety of missions, the fleets are deployed both off CONUS and to forward stations. Each forward station holds a full-up multi-capable battle fleet. CONUS forces are kept ready to surge from CONUS in the event of either a major war or an SSC. This deployment strategy is typical for the Navy during the Cold War and post-Cold War periods (1948-present).17 Figure 5 shows fleet deployments for one time-frame during this period, the late Cold War, and table 5 gives some of the missions assigned to those fleets.

Figure 5. U.S. Navy deployment, 1973-1989

17. There is a large literature on the forward deployed U.S. Sixth Fleet. See especially LCDR Philip A. Dur USN, "The Sixth Fleet: A Case Study of Institutionalized Naval Presence, 1946-1968" (Ph.D. Diss.: Harvard University, 1975). On the U.S. Seventh Fleet, see LCDR Joseph A. Sestak, Jr. USN "The Seventh Fleet: A Study of Variance Between Political Directives and Military Force Postures" (Ph.D. Diss.: Harvard University, 1984).

--16--

Table 5. Context for U.S. Navy deployment pattern, 1973-1989

| Important deployed units | Core missions |

| 7th Fleet | High-intensity warfare vs. Soviet Union: Exercises & surveillance ops to deter/prepare to defeat Soviet Navy & forces ashore in N. Pacific, Arctic, Indian oceans & littorals SSCs in the China Seas: E.g.: Vietnam minesweeping, prepare for & execute NEOs, shows of force, KAL-007 shootdown recovery ops OOTW throughout the Western Pacific & Indian ocean littorals: E.g.: Showing the flag, Freedom of Navigation (FON) ops |

| 3rd Fleet | High-intensity warfare vs. Soviet Union: Exercises and surveillance ops to deter/prepare to defeat Soviet Navy & forces ashore in N. Pacific OOTW: E.g.: Hosting PRC delegation |

| 2nd Fleet | High-intensity warfare vs. Soviet Union: Exercises and surveillance ops to deter/prepare to defeat Soviet Navy & forces ashore in N. Atlantic, Arctic oceans & littorals SSCs in the Caribbean: E.g.: Grenada intervention, Central American surveillance ops, prepare for NEOs, shows of force OOTW in the Caribbean: E.g.: Showing the flag, counter-drug operations< |

| 6th Fleet | High-intensity warfare vs. Soviet Union: Exercises and surveillance ops to deter/prepare to defeat Soviet Navy & forces ashore in Mediterranean & Black seas & littorals SSC operations in the Middle East and North Africa: E.g.: Shows of force, Prepare for and execute NEOs, Airlift support, Suez minesweeping, Red Sea mine-hunting, Lebanon intervention support, Libya strikes, airliner diversion OOTW throughout the Mediterranean and Black Sea littorals: E.g.: Showing the flag, FON ops |

| Middle East Force |

SSCs, especially viz a viz Iraq and Iran: E.g.: Tanker escort, minesweeping, oil platform bombardment, prepare for NEOs OOTW throughout the Persian Gulf and Red Sea littorals: E.g.: Showing the flag |

Why was the fleet deployed like this?

--17--

The Navy decided after World War II that, based on its World War II experience, the multi-capable, task-organized, forward-deployed battle fleet was the paradigm for everything.18 Preparation for high-intensity war with the Soviets (and, later, mid-intensity war with the Iraqis and North Koreans) necessitated a focus on battle-fleet organization and combat capability. The actual likelihood of such activity - especially during the last quarter-century of U.S. Navy history - has been small (contrast this with the high likelihood of war during the first quarter-century of U.S. Navy history).

Meanwhile, the country had become a superpower with diverse global peacetime interests. The Navy had to do both the numerous SSC/OOTW tasks and the major war-preparation task simultaneously, with the same ships.19 (There were a few exceptions. Two examples: the Northern European Force from the mid-1940s through the mid-1950s and the MIDEASTFOR from the late 1940s to the late 1970s were OOTW forces, somewhat reminiscent of the Asiatic Fleet and the Special Service Squadron in the Caribbean half a century earlier.20)

____________

18. The conceptual roots of this policy are laid out in Samuel P. Huntington, "National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 80 (May 1954), 483-493. The paradigm Huntington presents is about as valid today as when he wrote it, and tracks well with the Navy's post-Cold War policy statement, Forward...From the Sea (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1994).

19. For an analysis of the late Cold War and early post-Cold War record, see H.H. Gaffney et al., U.S. Naval Responses to Situations, 1970-1999 (Alexandria VA: Center for Naval Analyses, Center for Strategic Studies, December 2000).

20. For a history of the Middle East Force, see Michael Palmer, On Course to Desert Storm: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf (Washington DC: Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Center, 1992); and W. Seth Carus et al. From MIDEASTFOR to Fifth Fleet: Forward Naval Presence in Southwest Asia, October 1996 (CNA Research Memorandum 95-219).

--18--

Maintaining deployment patterns

Each of the preceding models was driven by a particular set of influences: national goals, the international environment, the domestic social climate, and the existing level of naval technology. Here we will briefly discuss the effect of those influences on U.S. Navy deployment patterns in three important eras.

The old "forward stations"

How did the "Old Navy" maintain itself on distant station for SSC operations and OOTW?21 While deployments in the 19th and early 20th centuries varied somewhat by region and decade, they generally shared two basic characteristics:

* A ship-by-ship, port-by-port pattern of "showing the flag"

* A three-year tour of duty.

The squadrons were administrative rather than tactical units. Except during the winter months in the Mediterranean, it was unusual for all the vessels to be assembled in any one place. In current parlance, there was normally no "battle-group integrity." The Navy Department policy was for the ships to keep moving from port to port, and especially to pry them away from the more attractive ports of call. Occasionally, for a particularly important SSC operation, all the ships of a squadron would come together, as occurred when the Mediterranean Squadron assembled to pressure the King of Naples for President Jackson in 1836, and when Commodore Perry went to open Japan to foreign trade in 1853-54.

The three-year cruise was likewise a dominant feature of the distant squadrons. Normally, a ship enlisted a crew for those three years and she was expected to deliver them back to their home yard before that time was up. On arrival there, the crew was discharged and the officers given a brief leave. On the more distant stations, particularly the China/Asiatic, more than half of the three-year period was often used up coming and going.

___________

21. This discussion is adapted from Albion, "Distant Stations," 270.

--19--

There were a few exceptions to the three-year-cruise pattern. Because of its generally unhealthy conditions, the Africa Station tour of duty was reduced to two years. In a harbinger of current Fifth Fleet mine-warfare vessel manning policy in the Persian Gulf, the river gunboats in China stayed out there indefinitely while other vessels brought out new crews to relieve the old ones.

Why did these patterns hold?

First, the SSCs and OOTW practiced by the U.S. Navy during this period could be handled by a one- or two-ship force, and occasionally by a squadron. Large expeditions - such as the 18 warships and auxiliaries sent up the Parana River in 1859 to coerce the Paraguayans - were rare. (In that instance, ships from the Home, Africa, and Brazil squadrons - as well a Revenue Service cutter - were coalesced into an ad hoc fleet).22

Moreover, the Navy had an additional important function to perform besides SSC operations and OOTW: It was a naval presence force as well. Showing the flag and reassuring local American consuls, missionaries, and merchants was an important part of its job.

Also, the maritime technology of the period allowed ships to stay far forward for extended periods - provided foreign depot support could be requisitioned, which it usually could. Wood, canvas, and rope were all repairable or replaceable even in distant Third World ports. And three-year tours forward were bearable - even desirable - by the Navy's officers and men. They also could be reconciled within the social mores and civil-military relations of the period.23

___________

22. This was the largest U.S. Navy squadron ever assembled between the Navy's founding and the Civil War, and the largest U.S. military expedition ever on South American soil. The story is in John Hoyt Williams, "The Wake of the Water Witch," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings Supplement, 1985, 14-19.

23. On the three-year deployments, see Albion, "Distant Stations," 270, and Patrick H. Roth, "The U.S. Navy's Brazil/South Atlantic Stations 1826-1904: An Informed Look," unpublished manuscript, 1995.

--20--

The Inter-regnum

Changes in the world and domestic environment and technology brought most of the forward squadrons home in the early 20th century. There, as the Atlantic Fleet and - later - the U.S. Fleet, they mostly stayed until World War II. The World War I European deployments and the Asiatic Fleet were the most notable exceptions, although there were others.

Some Asiatic Fleet sailors stayed in Asia for many years. The pros and cons of being a "China Fleet Sailor" and "going Asiatic" were constant sources of debate within the Navy. Ambitious career Navy men strove to stay with the fleet in CONUS.

Immediately following World War II, most of the Navy was simply demobilized. The remainder was deployed in and around the East and West Coasts, in the Fifth and Eighth "surge" fleets (like the old U.S. Fleet, but now divided between the coasts). Tiny task forces were maintained forward in the seas around Europe and Japan, and a small Seventh Fleet operated from Chinese and Philippine bases - the successor to the Asiatic Fleet. While there were more elements involved, the same essential underlying deployment pattern as during the interwar period is discernible.

The post-World War II forward fleets

Starting in the late 1940s, U.S. Navy deployment patterns again changed, to emphasize forward-deployed operations. This time, as we have seen, the forward-deployed elements were configured as forward-deployed combat-capable fleets ready for all possible operations - from naval presence, "show the flag" operations, through OOTW and SSCs, to general high-intensity and even nuclear war.

Ship and personnel rotation policies, however, differed greatly from those of earlier eras of forward deployment. Ships deployed for several months, but not years, and crew members rotated automatically

--21--

between sea and shore duty.24 Throughout the Cold War, the six-month deployment was the announced Navy goal, although it was not always achieved - and was seldom achieved during the Vietnam War and the various post-Vietnam Persian Gulf crises.25 During the post-Cold War period, however, the Navy has been adamant at maintaining six-month deployments in reality as well as rhetoric.26

Why the difference?

First, logistics requirements to support modern steel warships far exceed those of their wooden predecessors. Even with underway replenishment ships, tenders, and forward shore bases, modern warships need extensive routine maintenance, repair, and overhaul - evolutions best done in most cases in home yards.

Second, American social mores and civil-military relations have changed. Three-year deployment enlistments are gone. Now, concern for family separation and personnel retention are significant drivers of OPTEMPO and PERSTEMPO.

Back to the future

Nevertheless, as we enter the 21st century, there is much discussion of changing the Cold War and post-Cold War deployment rotation paradigm. The "Horizon" concept, developed in 1997 by CNO Strategic

____________

24. For an analysis of late Cold War U.S. Navy deployment length policy, see Christopher C. Wright, "U.S. Naval Operations in 1982," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings/Naval Review 109 (May 1983), 51-57.

25. In 1980, in an extreme example of breaking the six-month rule, a nuclear-powered carrier and two nuclear-powered cruisers deployed to the Indian Ocean for 251 days. At one point the carrier was at sea for 152 consecutive days.

26. In 1985, the CNO ordered cuts in deployment schedules to eliminate excessive at-sea periods for ships and aircraft squadrons, resulting in adherence to the six-month deployment rule. See Roy A. Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation, 1910-1995 (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1997), 327, 348, 352.

--22--

Studies Group (SSG) XVI, is currently being examined in OPNAV and elsewhere.27

What is "Horizon's" vision? Among other things, it is to use state-of-the-art and future technology and organizational concepts to achieve:

* Platforms capable of remaining forward deployed for up to three years

* Fully trained and ready sailors to rotate to these platforms.

Significantly, "Horizon" assumes a continuation of the forward-deployed combat-capable fleet model of the Cold War and Post-Cold War years (our Multi-Mission, Multi-Area Mixed Fleets Model), rather than a change to a new (or old) alternative deployment model.

Conclusion

Again, what we have sought to demonstrate in this paper is that before World War II and the Cold War there were times when different environments and technology required different Navy deployment policy paradigms. The overwhelming power of recent history - i.e., of the post-World War II paradigm - has focused the Navy on what it is doing now, as an extension of what it recently did, at the expense of what it could do. We hope that this paper can begin putting the various models of both deep and recent history in the proper perspective, to the benefit of Navy forward deployment planning for the future.28

__________

27. "Horizon" was first laid out in Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group XVI, Naval Warfare Innovation Concept Team Reports (Newport, RI: Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group, June 1997), VIII-1-12.

28. For a somewhat related analysis examining six American, French and British historical case studies of the use of forward military presence for peacetime political shaping, see Edward Rhodes, Jonathan Di Cicco, Sarah Milburn Moore, and Tom Walker, "Forward Presence and Engagement: Historical Insights into the Problem of Shaping" Naval War College Review (Winter 2000) LIII, 25-61

--23--

Related CNA studies

Barnett, Thomas P. M. and Henry C. Gaffney, Jr., Reconciling Strategy and Forces Across an Uncertain Future: Three Alternative Visions, July 1993 (CNA Research Memorandum 93-80) Limited to DoD Agencies.

Brooks, Linton F., Peacetime Influence Through Forward Naval Presence, October 1993 (CNA Occasional Paper) https://www.cna.org/reports/1993/peacetime-influence

Dismukes, Bradford, National Security Strategy and Forward Presence: Implications for Acquisition and Use of Forces, March 1994 (CNA Research Memorandum 93-192) https://www.cna.org/reports/1994/nss-and-forward-presence

__________, The Political-Strategic Case for Presence: Implications for Force Structure and Force Employment, June 1993 (CNA Annotated Briefing 93-7) Limited to DoD Agencies.

Gaffney, Henry H., Jr. et al., U.S. Naval Responses to Situations, 1970-1999, December 2000 (CNA Research Memorandum D0002763.A2/Final) Distribution Limited.

Roberts, Stephen S., The Decline of the Overseas Station Fleets: The United States Asiatic Fleet and the Shanghai Crisis, 1932, November 1977 (CNA Professional Paper 208) Informal Paper/Professional Paper

__________, An Indicator of Informal Empire: Patterns of U.S. Navy Cruising on Overseas Stations, 1869-1897, September 1980 (CNA Professional Paper 295) Informal Paper/Professional Paper

Siegel, Adam B., To Deter, Compel and Reassure in International Crises: The Role of U.S. Naval Forces, February 1995 (CNA Research Memorandum 94-193) https://www.cna.org/reports/1995/deter-compel-and-reassure

__________, The Use of Naval Forces in the Post-War Era: U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps Crisis Response Activity, 1946-1990, February 1991 (CNA Research Memorandum 90-246) https://www.cna.org/reports/1991/the-use-of-naval-forces-in-the-post-war-era

Stewart, George, Scott M. Fabbri, and Adam B. Siegel, JTF Operations Since 1983, July 1994 (CNA Research Memorandum 94-42) https://www.cna.org/reports/1994/jtf-operations-since-1983

Swartz, Peter M. and E. D. McGrady, A Deep Legacy: Smaller-Scale Contingencies and the Forces that Shape the Navy, December 1998 (CNA Research Memorandum 98-95.10) https://www.cna.org/reports/1998/a-deep-legacy

For copies call: CNA Document Center (703) 824-2123.

[END]