The Navy Department Library

COMBAT NARRATIVES

Solomon Islands Campaign: XII The Bougainville Landing and the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay 27 October- 1 November 1943

PUBLICATIONS BRANCH

OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES NAVY

1945

PDF Version [34.1MB]

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D.C.

1 March 1945.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U.S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

[Signature]

HEWLETT THEBAUD,

REAR ADMIRAL, USN

Director of Naval Intelligence

CONFIDENTIAL

II

Foreword

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort had been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

[Signature]

E.J. King,

FLEET ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

CONFIDENTIAL

III

Charts and Illustrations

| Facing page | |

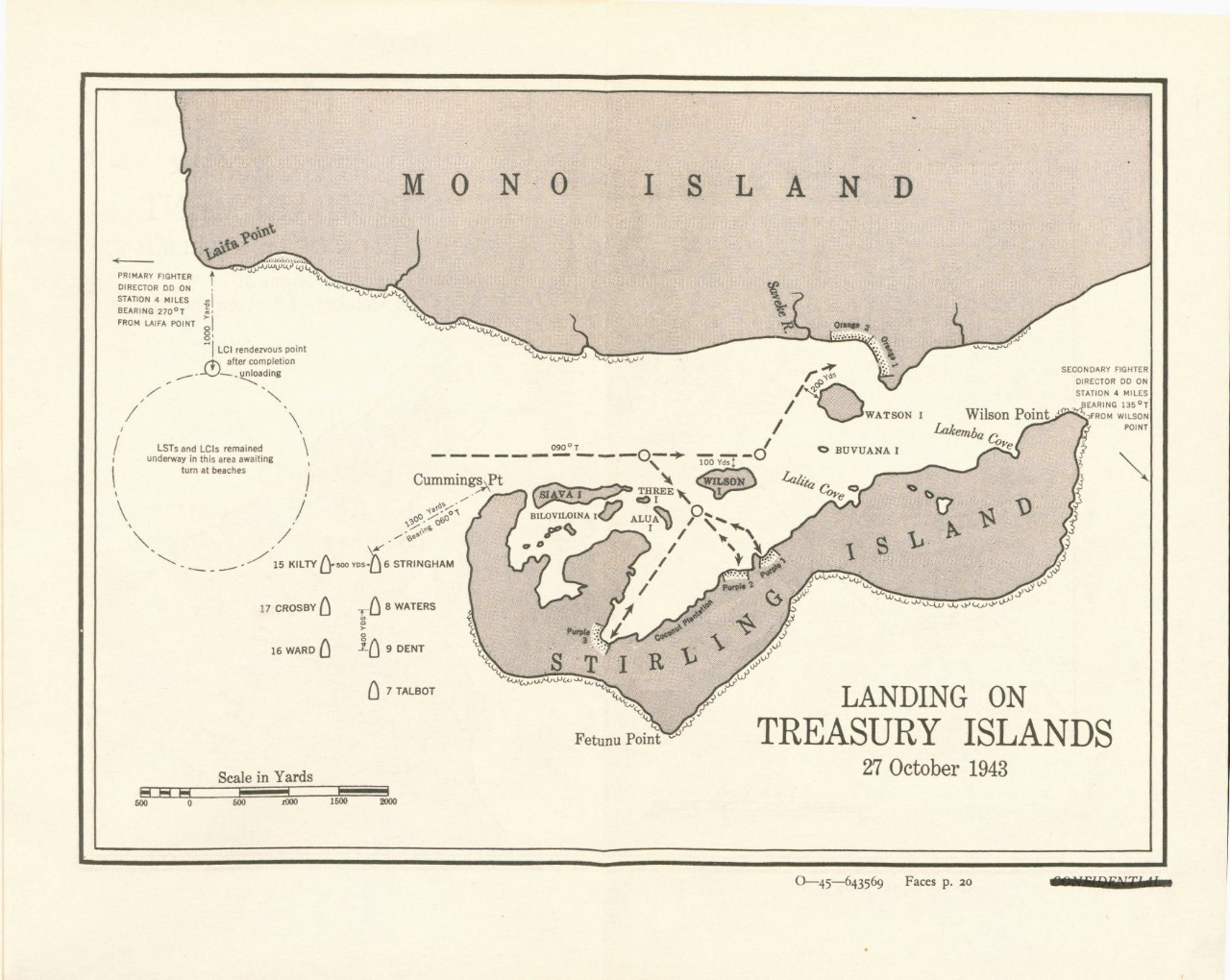

| Chart: Landing on Treasury Islands | |

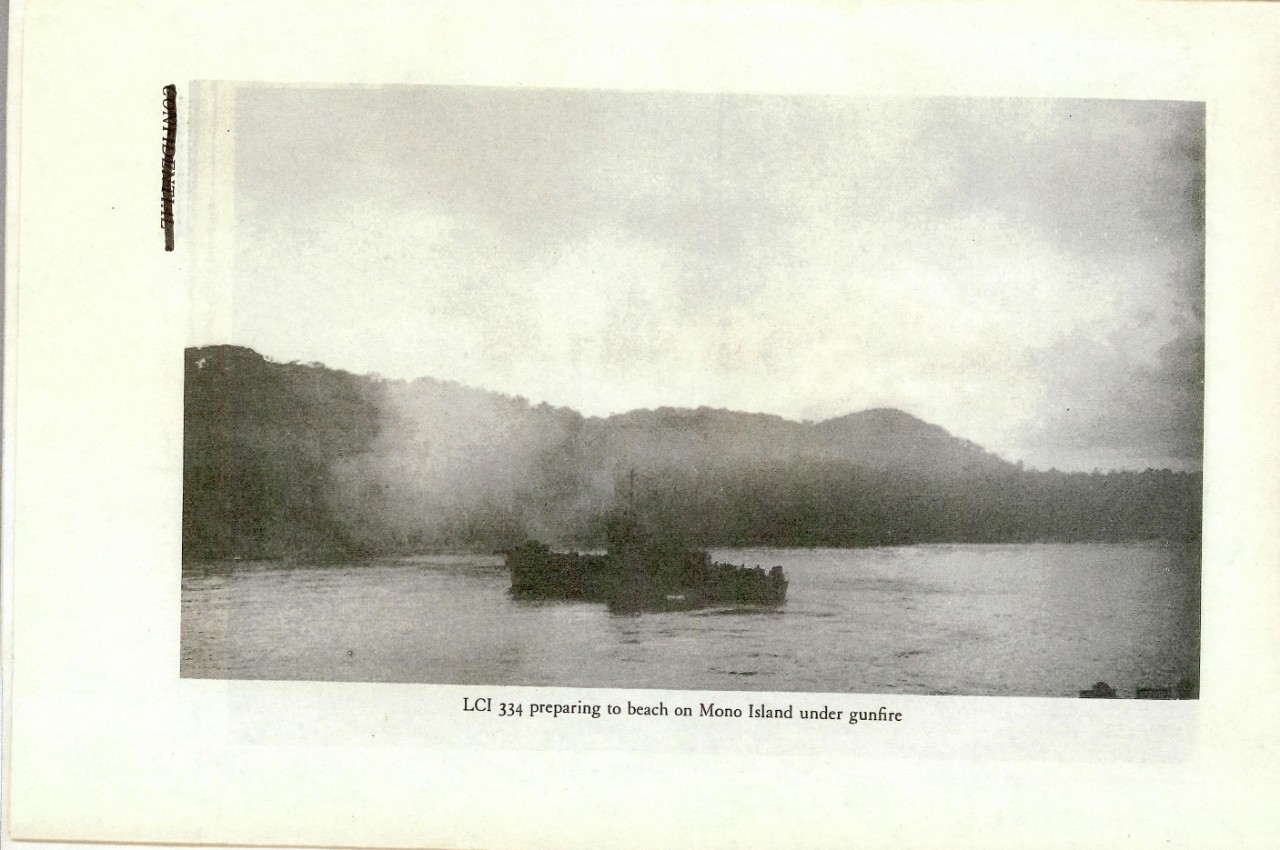

| Illustration: LCI 334 preparing to beach on Mono | 20 |

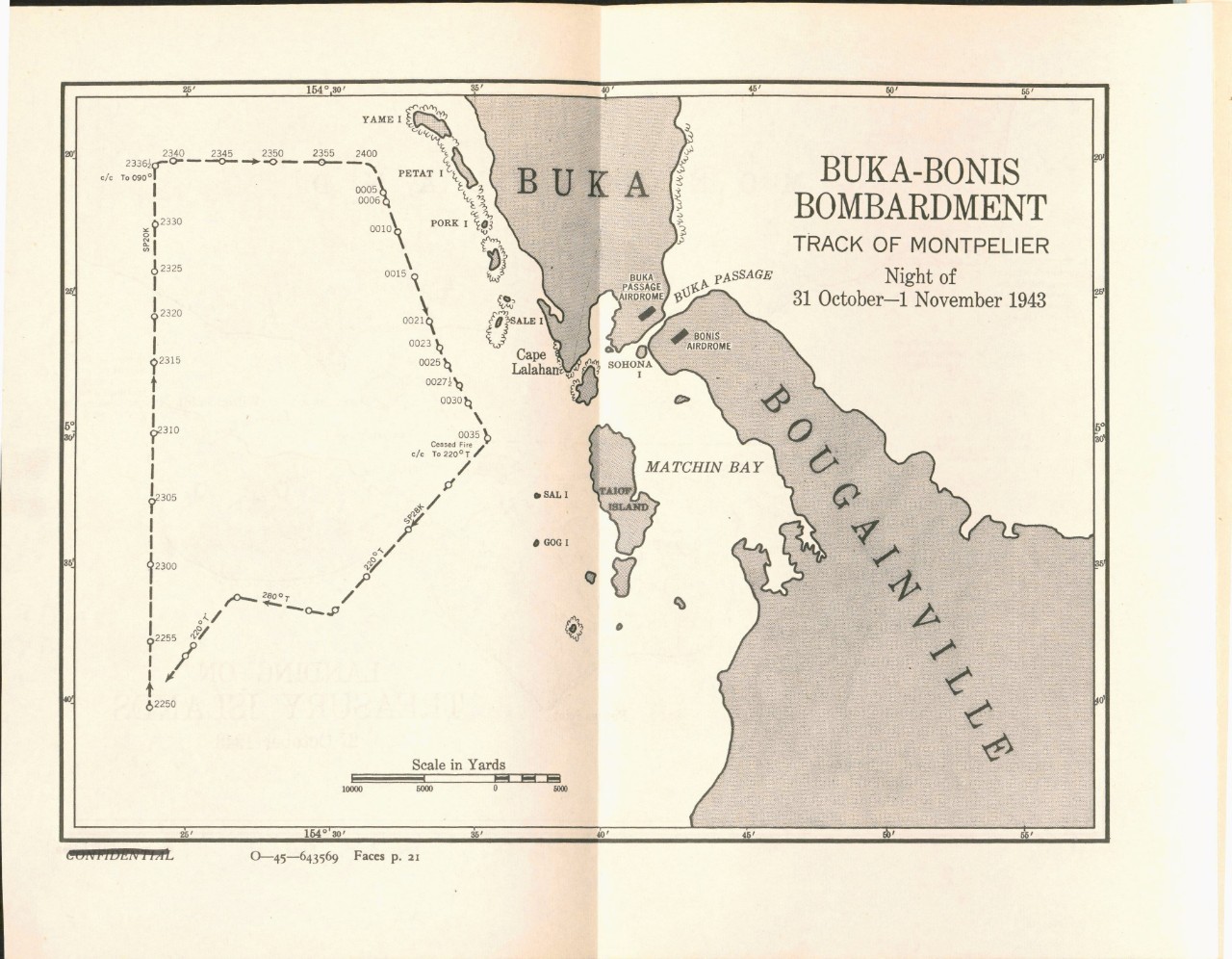

| Chart: Buka-Bonis Bombardment | |

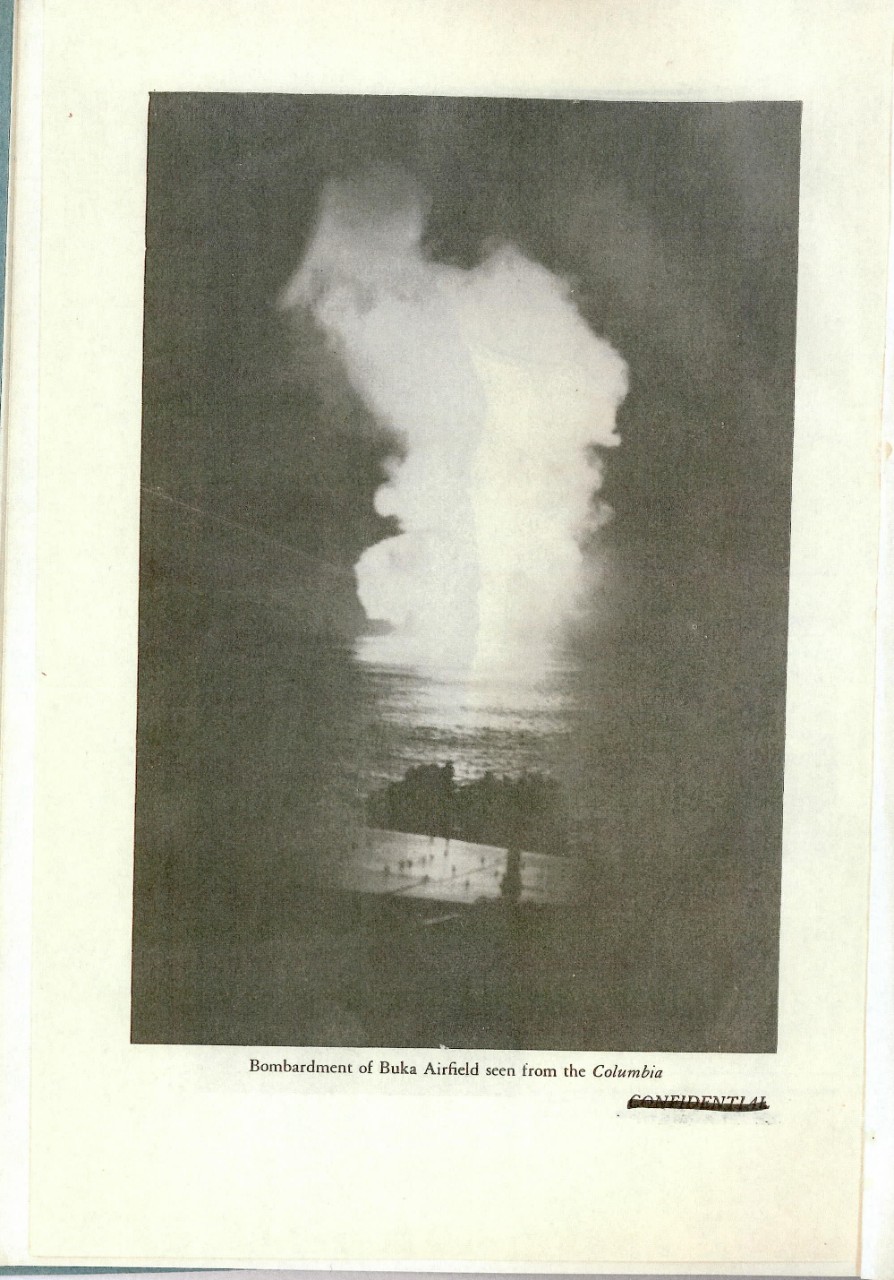

| Illustration: Bombardment of Buka Airfield | 21 |

| Illustrations | between pages 26-27 |

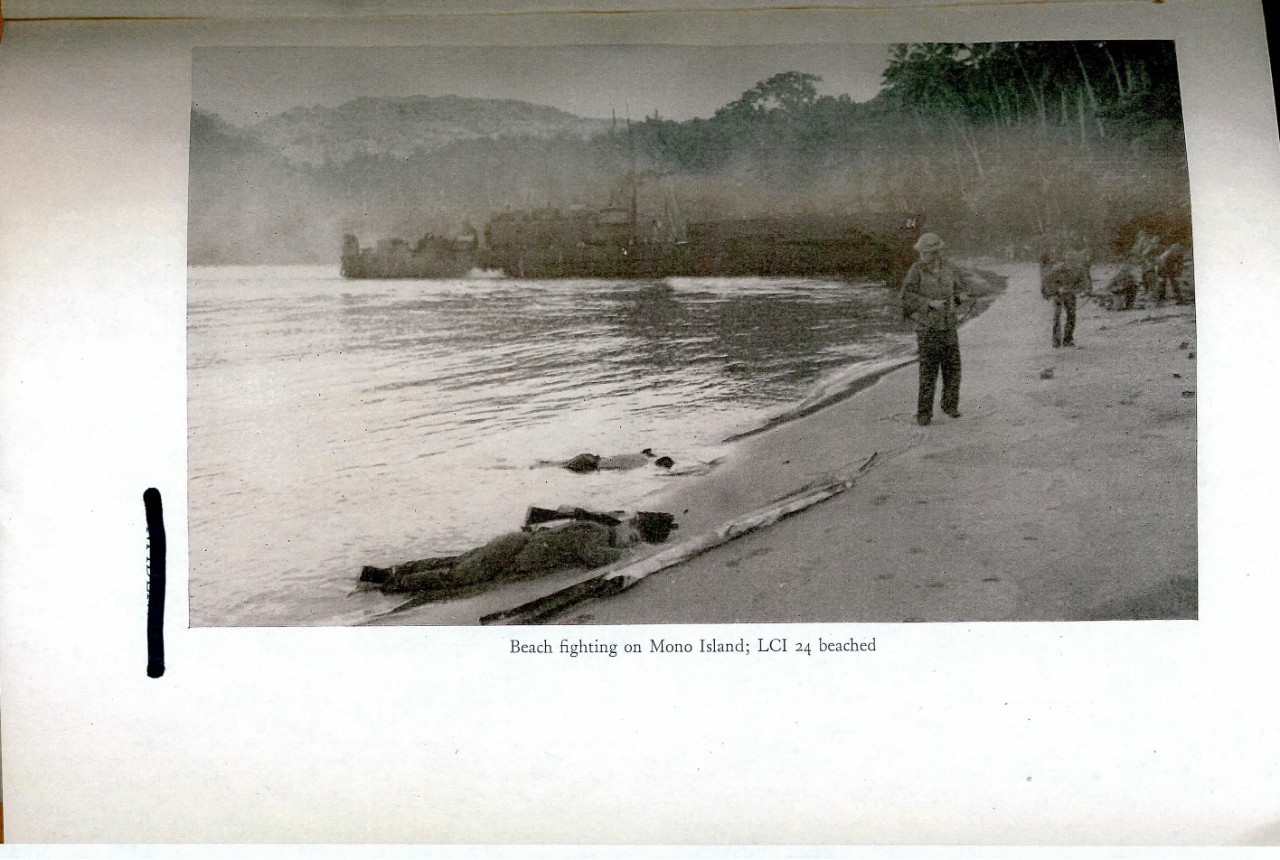

| Beach fighting on Mono Island | |

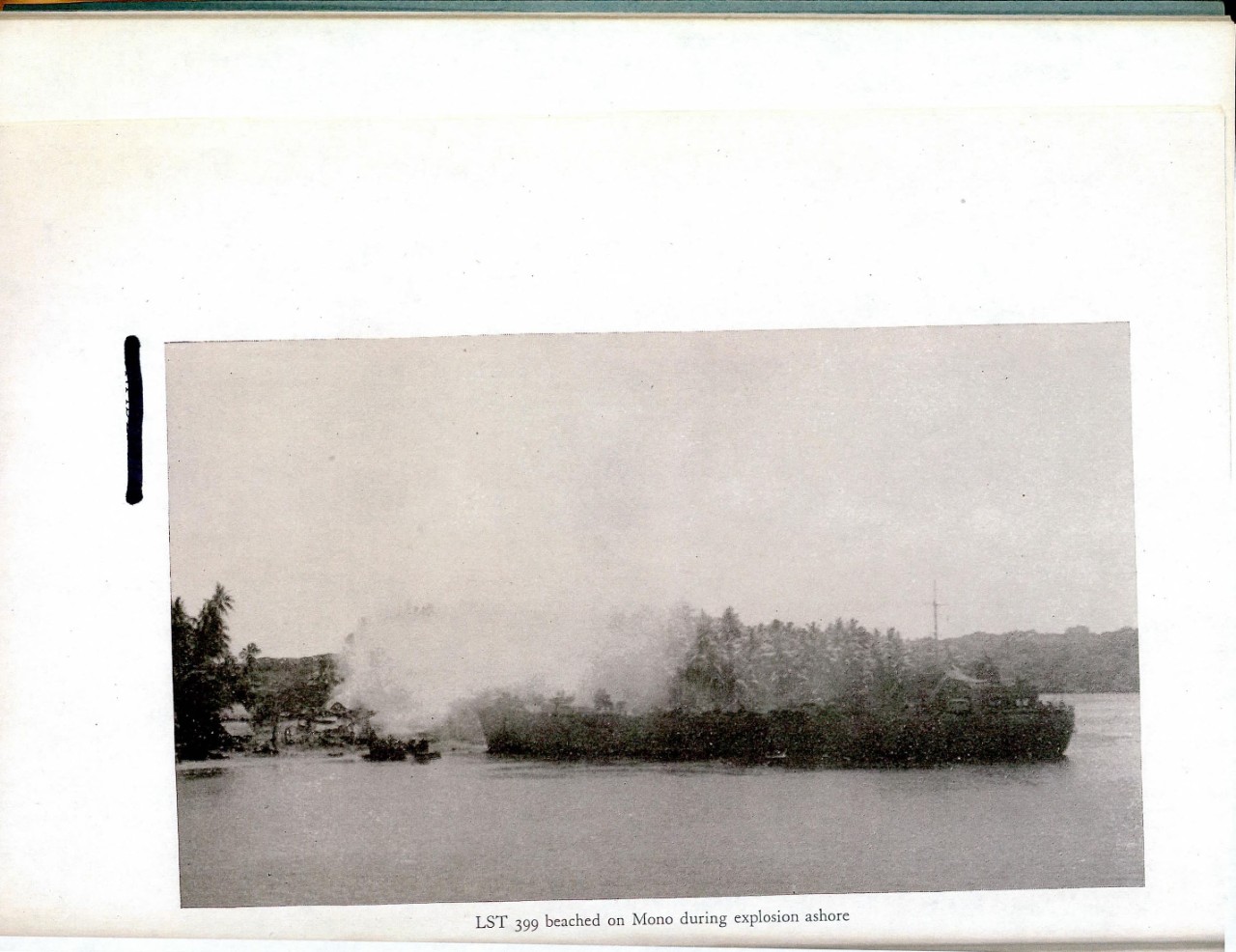

| LST 399 beached on Mono | |

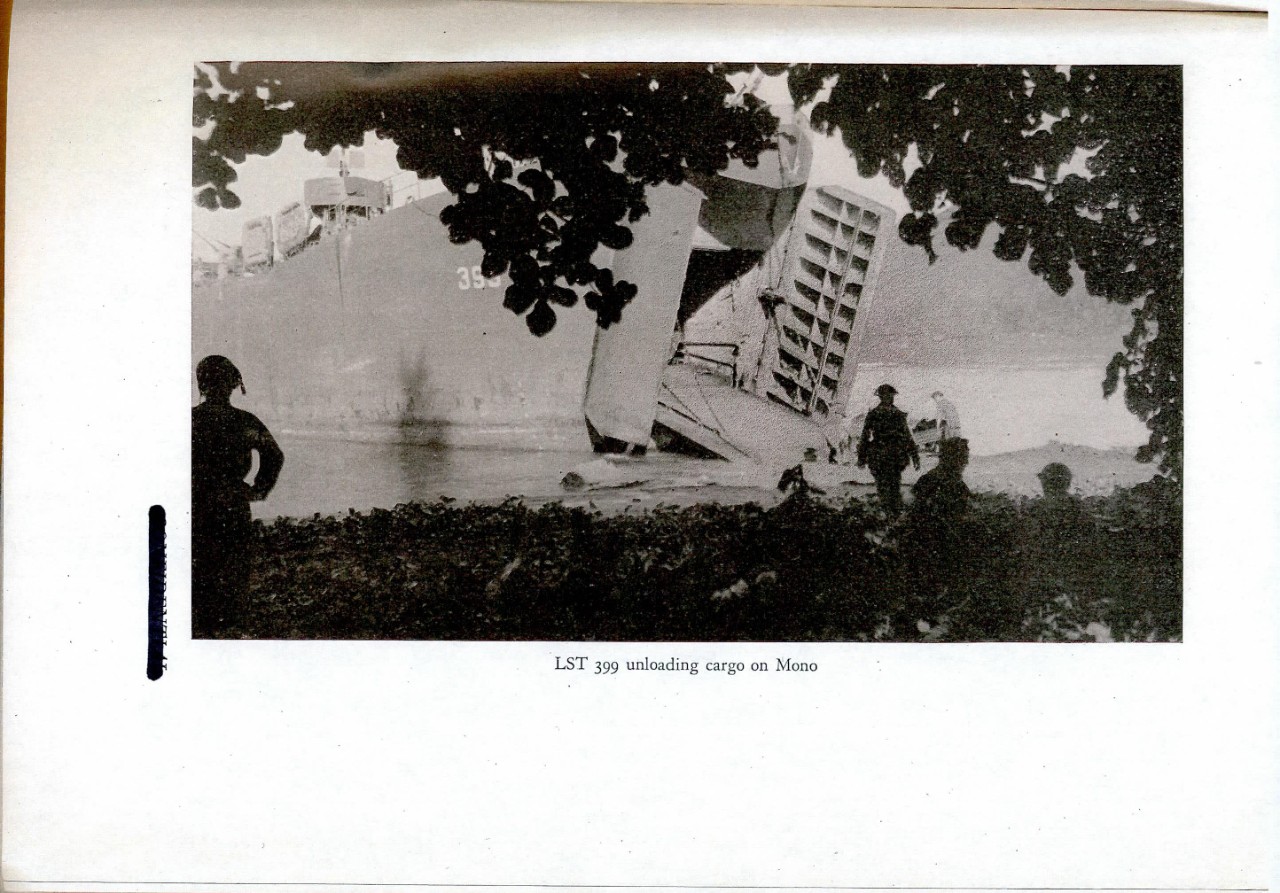

| LST 399 unloading cargo on Mono | |

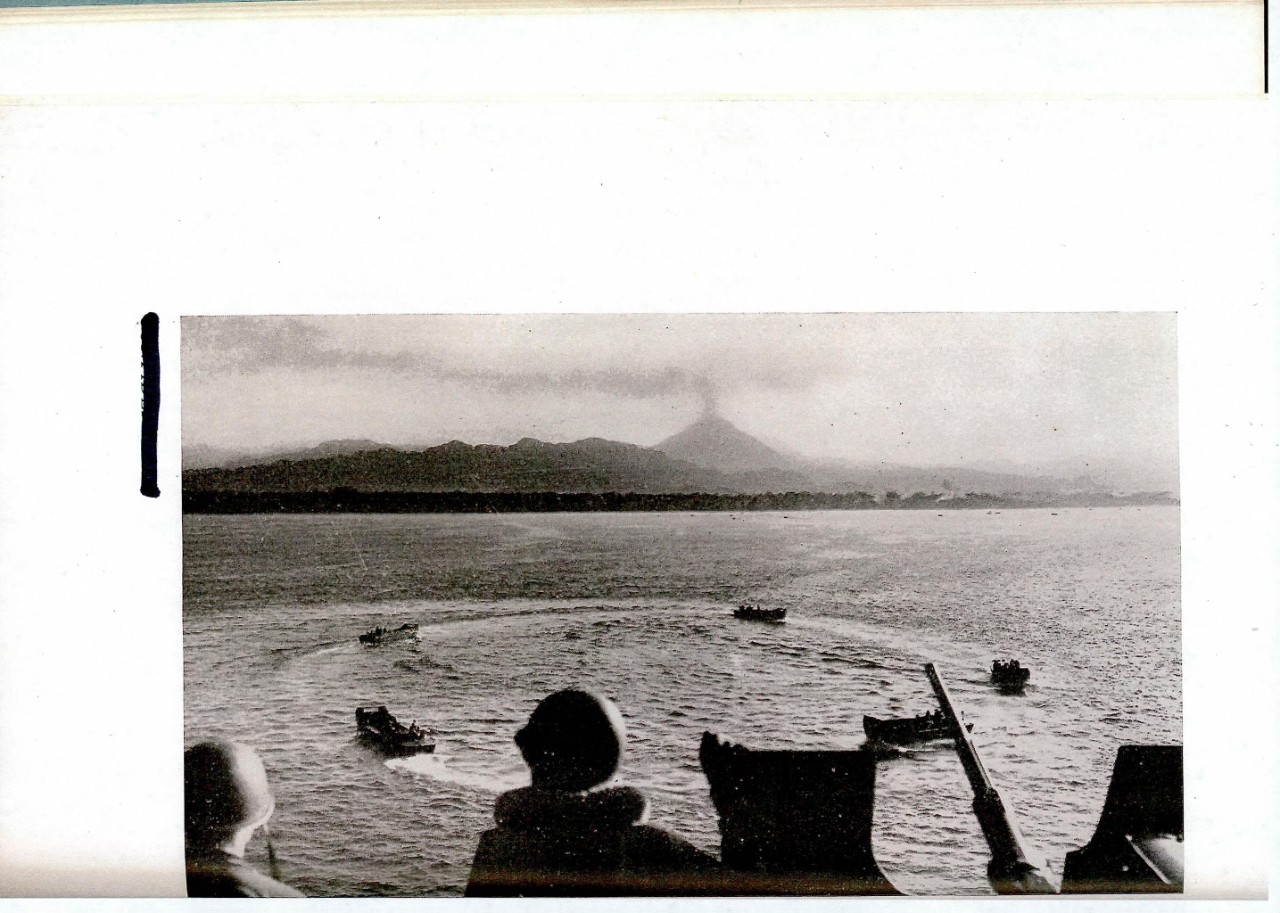

| Landing craft circle before | |

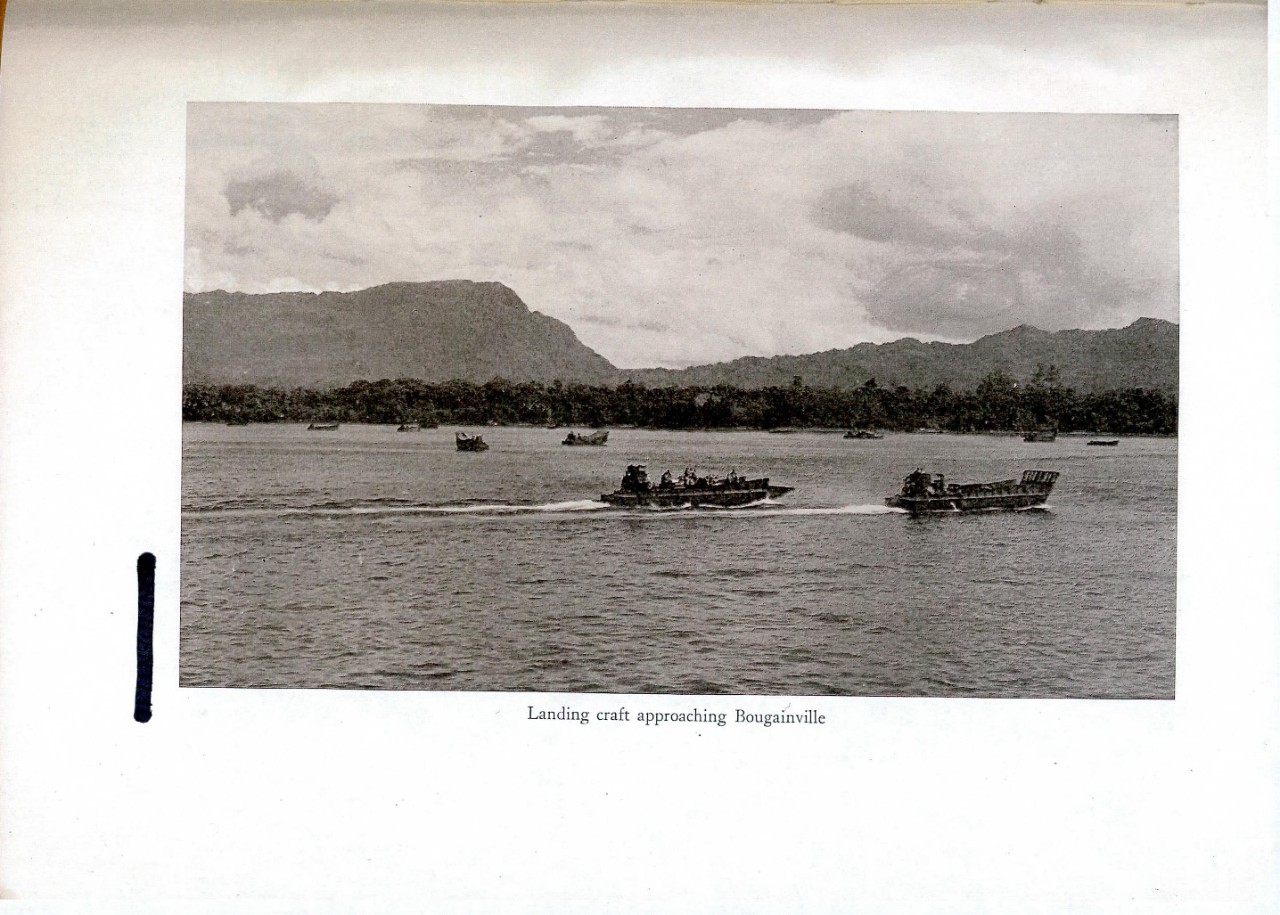

| Landing craft approaching Bougainville | |

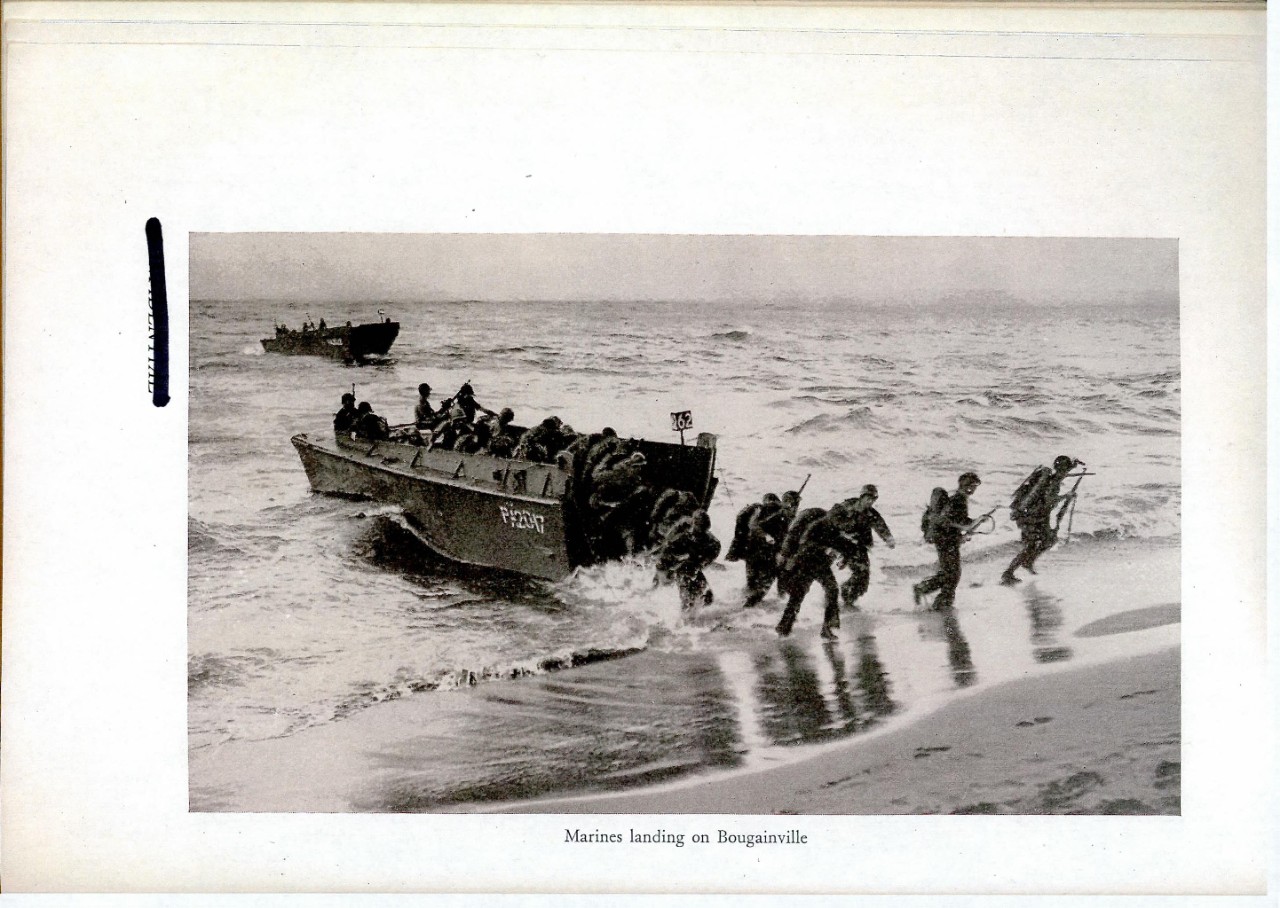

| Marines landing on Bougainville | |

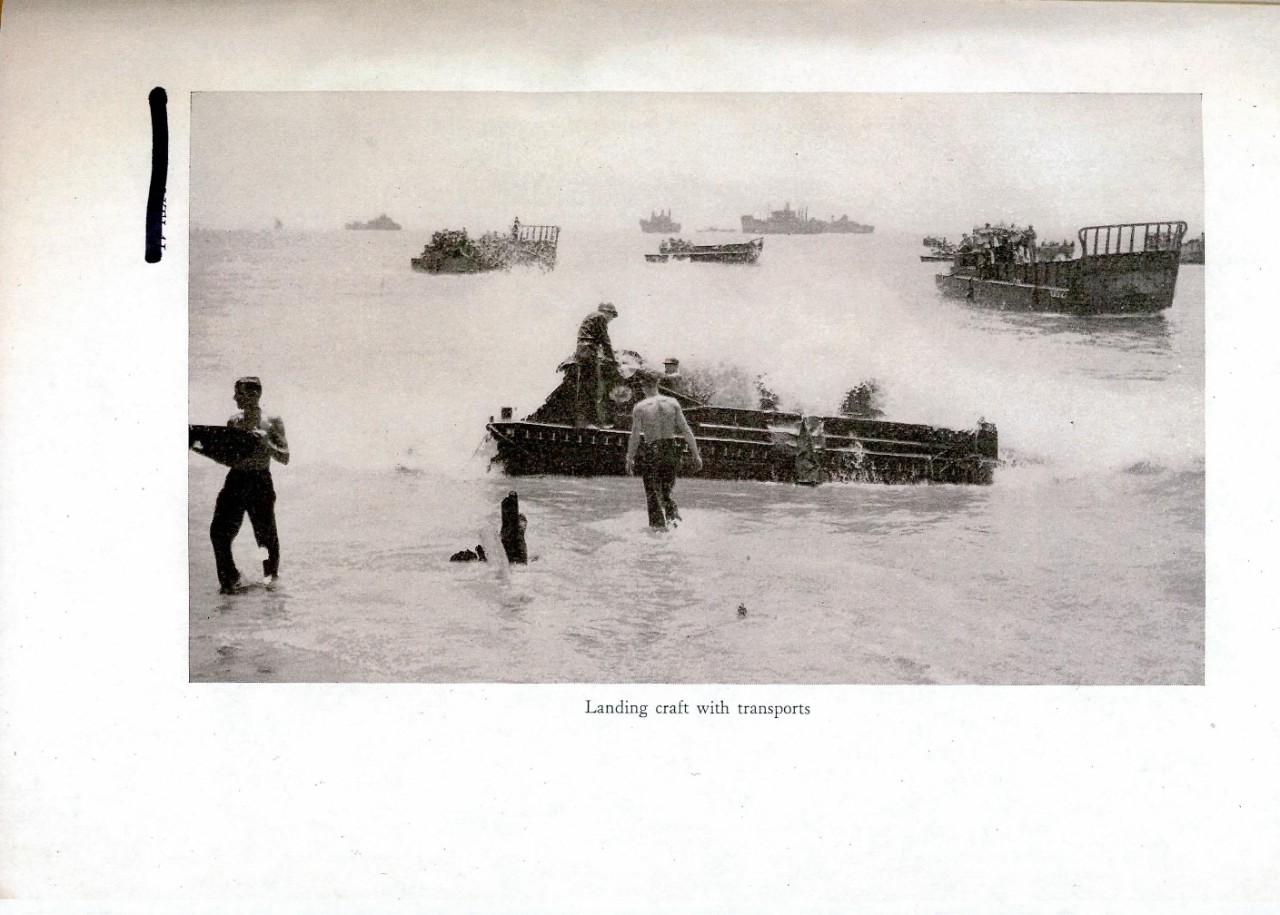

| Landing craft with transports | |

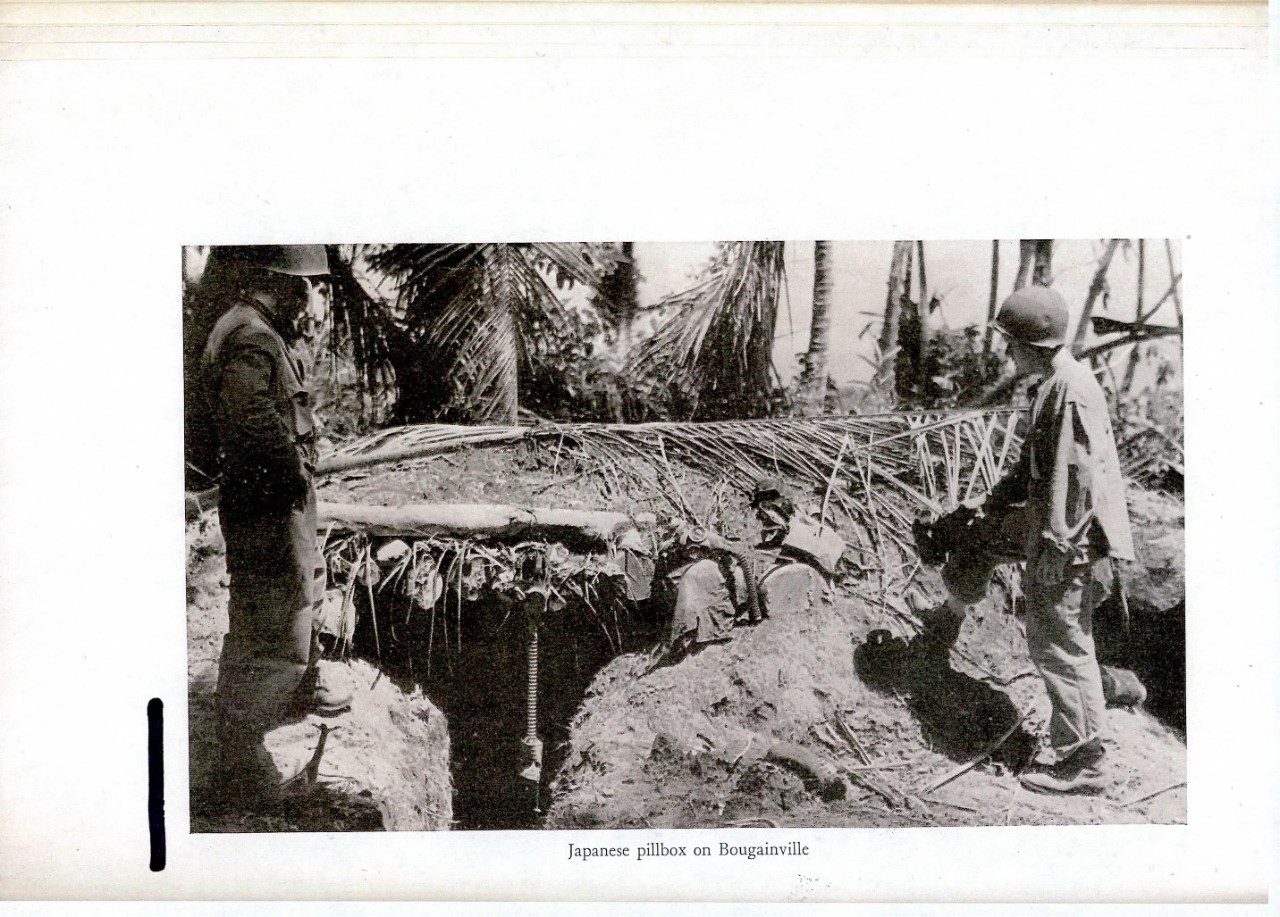

| Japanese pillbox on Bougainville | |

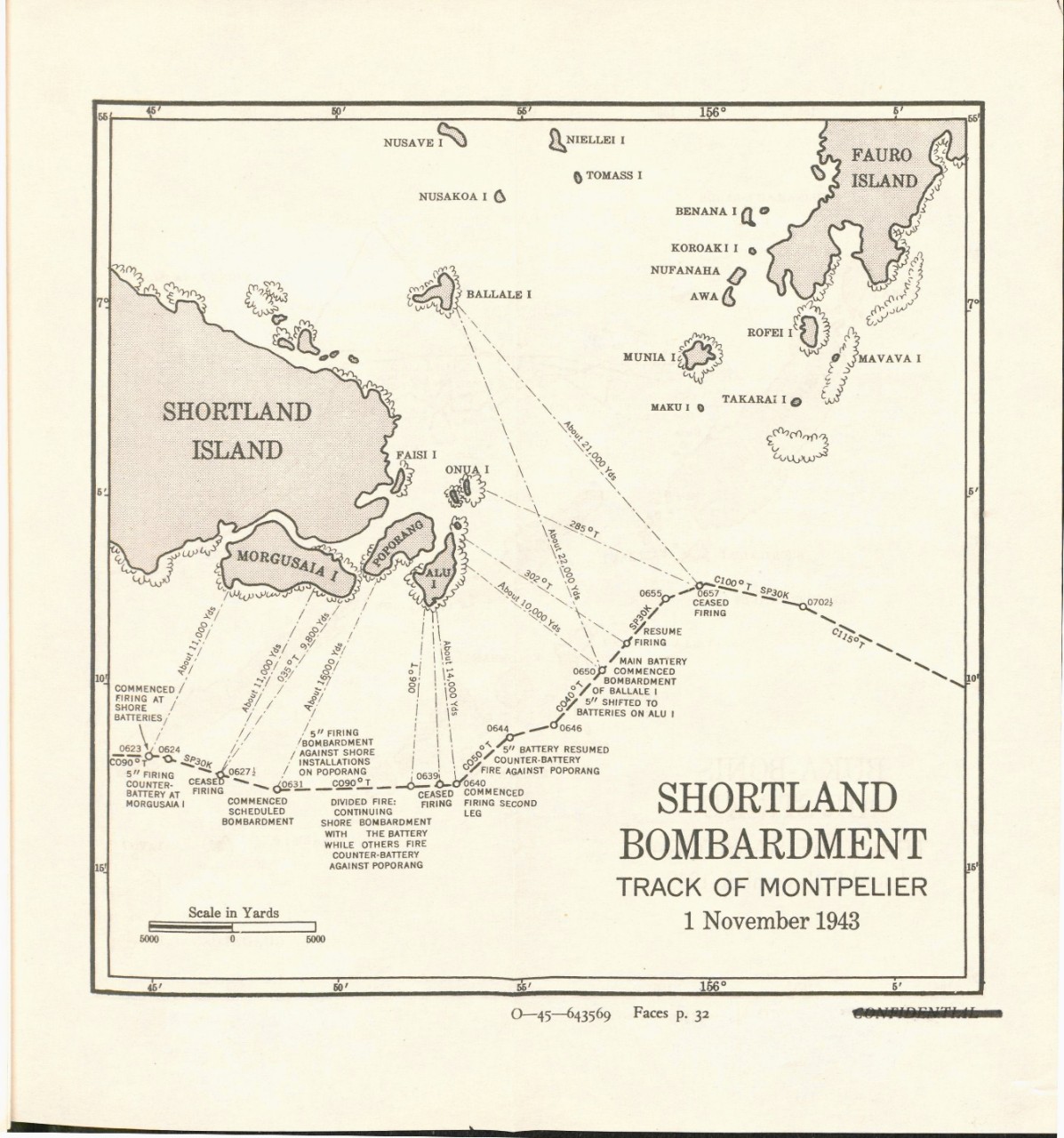

| Chart: Shortland Bombardment | |

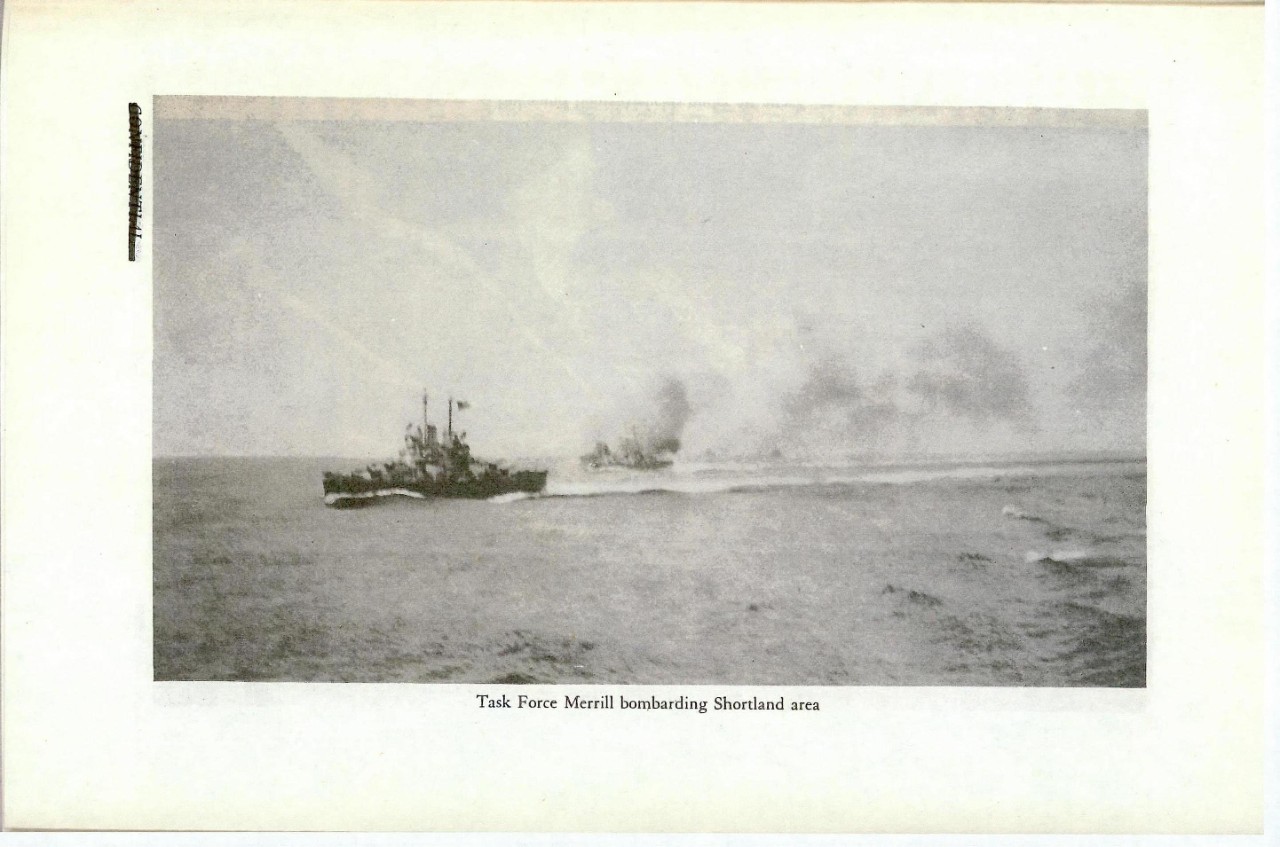

| Illustration: Task Force Merrill | 32 |

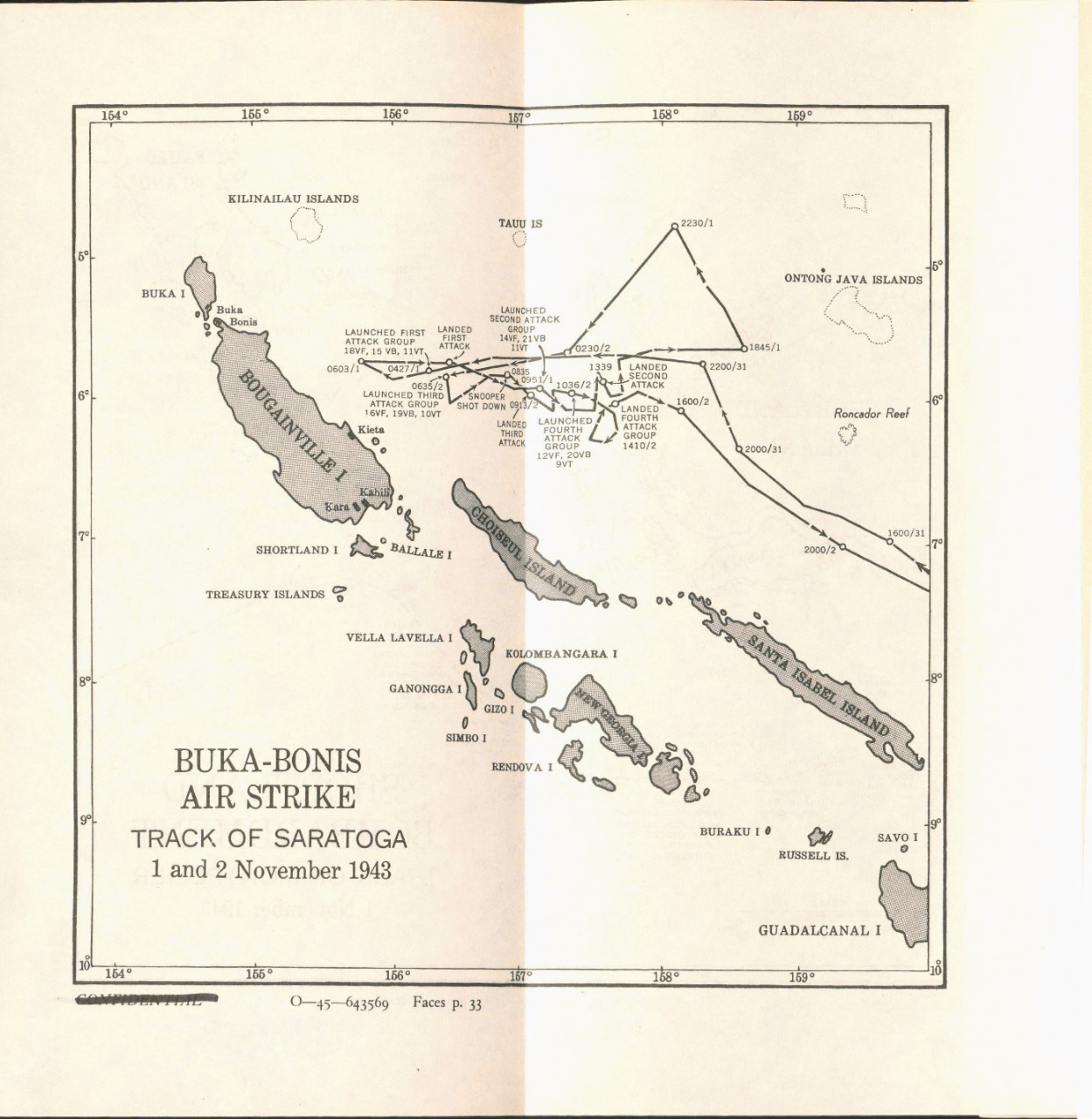

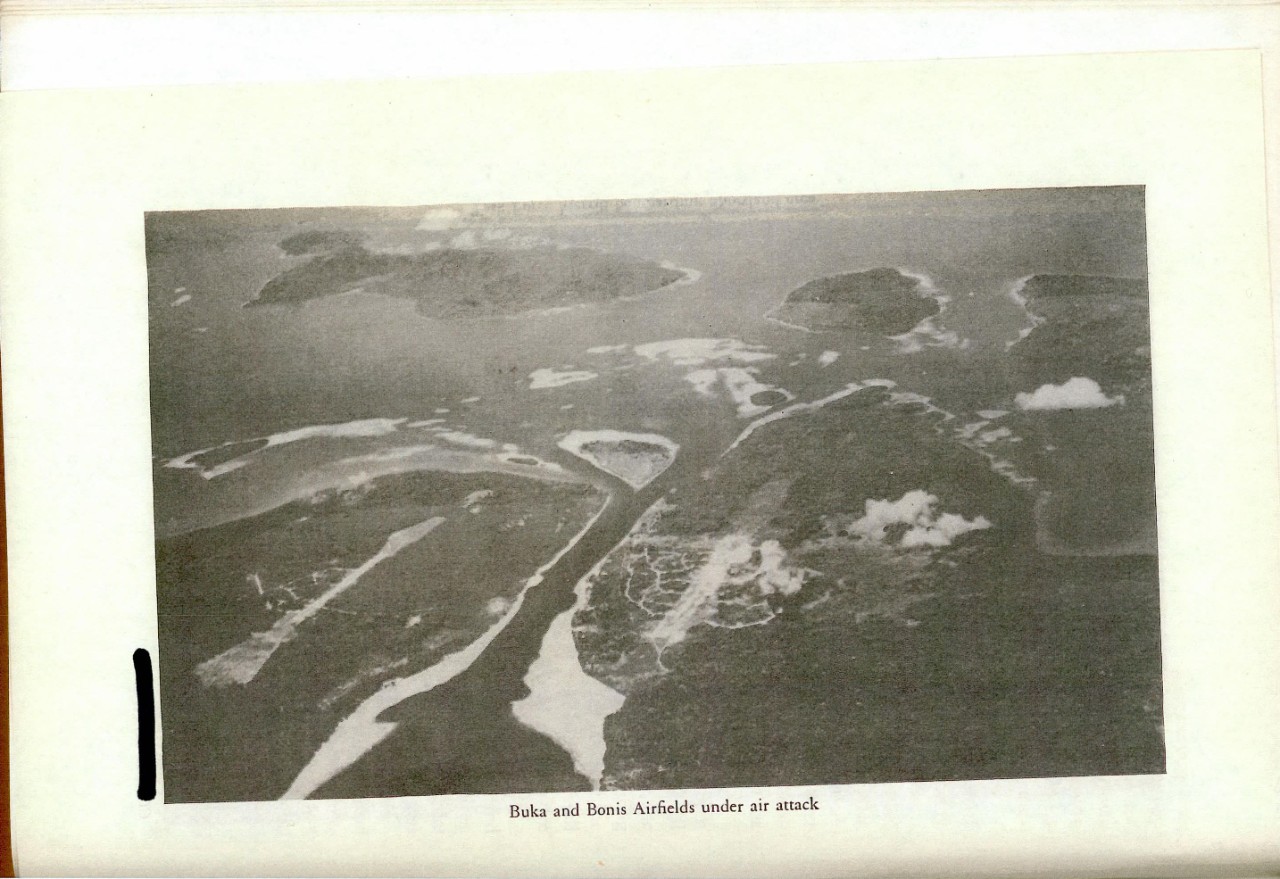

| Chart: Buka-Bonis Air Strike | |

| Illustration: Buke and Bonis Airfields | 33 |

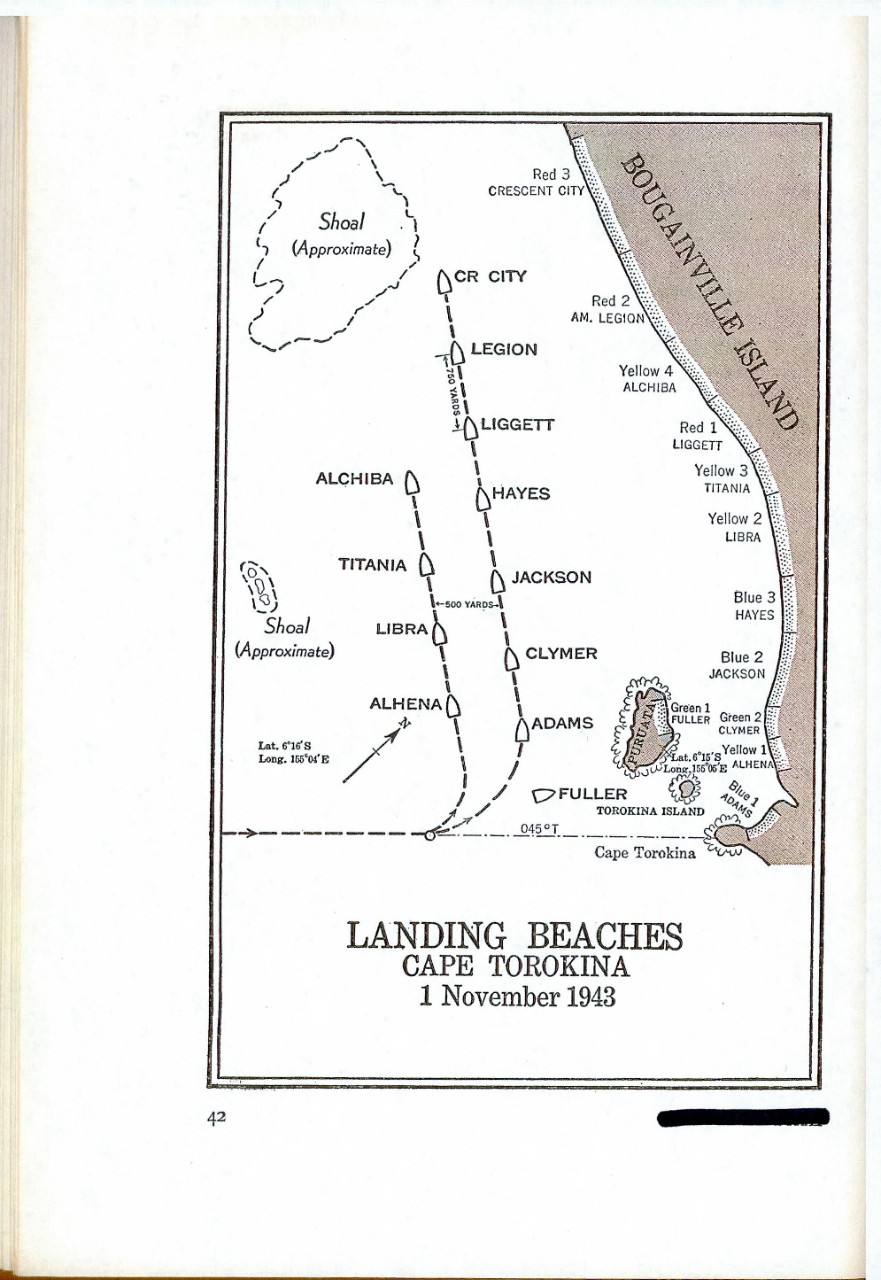

| Diagram: Landing Beaches, Cape Toronkina | on page 42 |

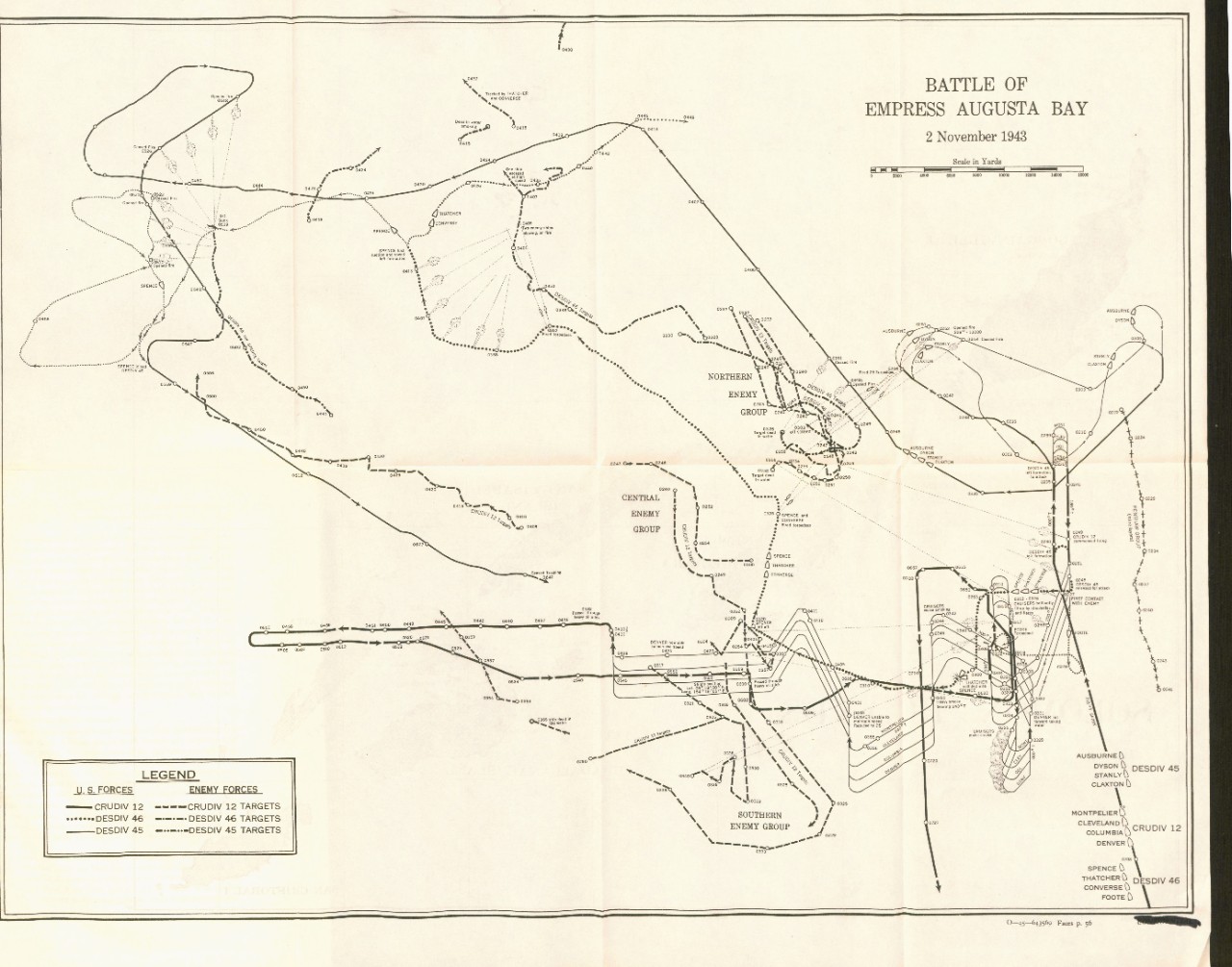

| Chart: Battle of Empess Augusta Bay | 56 |

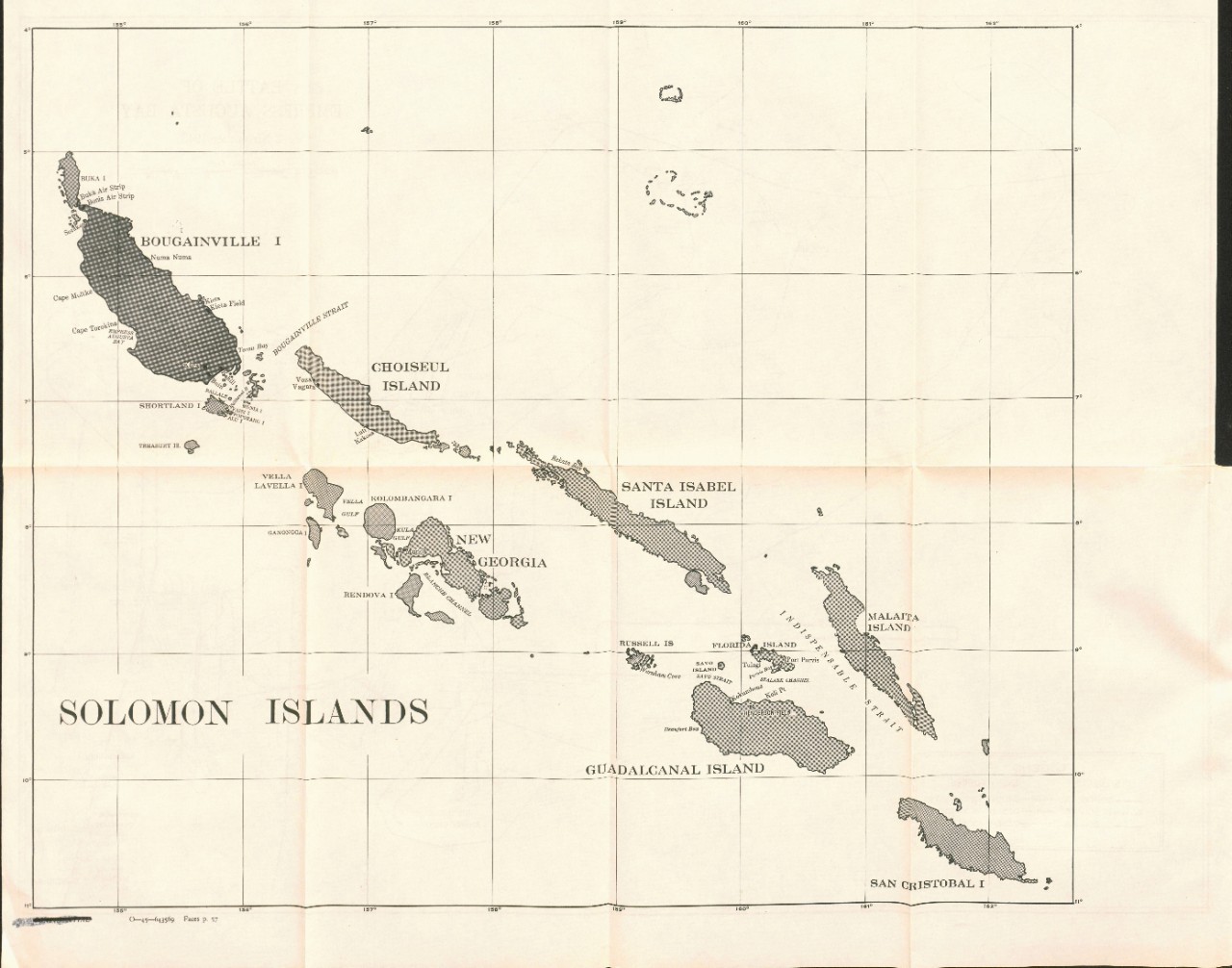

| Chart: Solomon Islands | 57 |

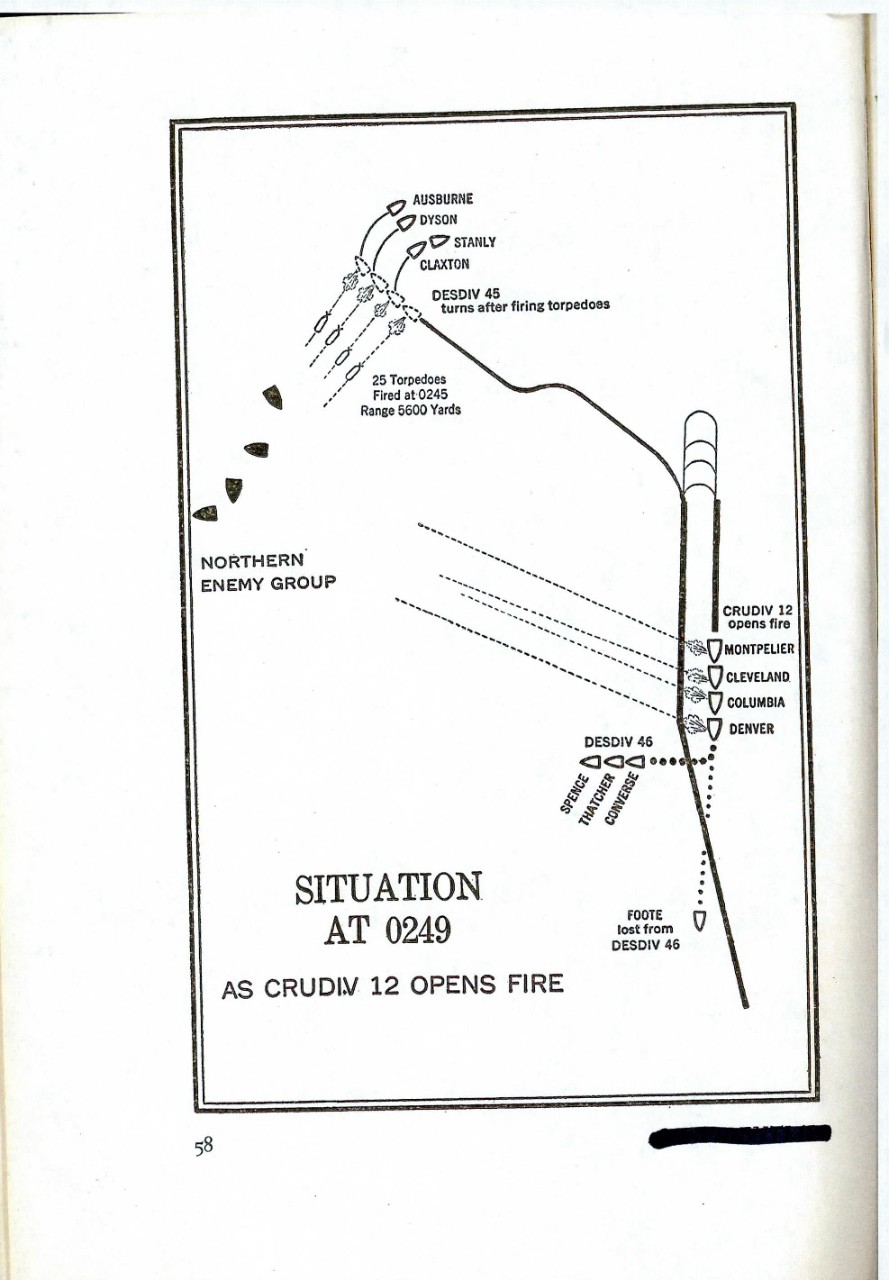

| Diagram: Battle Situation at 0249 | on page 58 |

| Illustrations | between pages 74-75 |

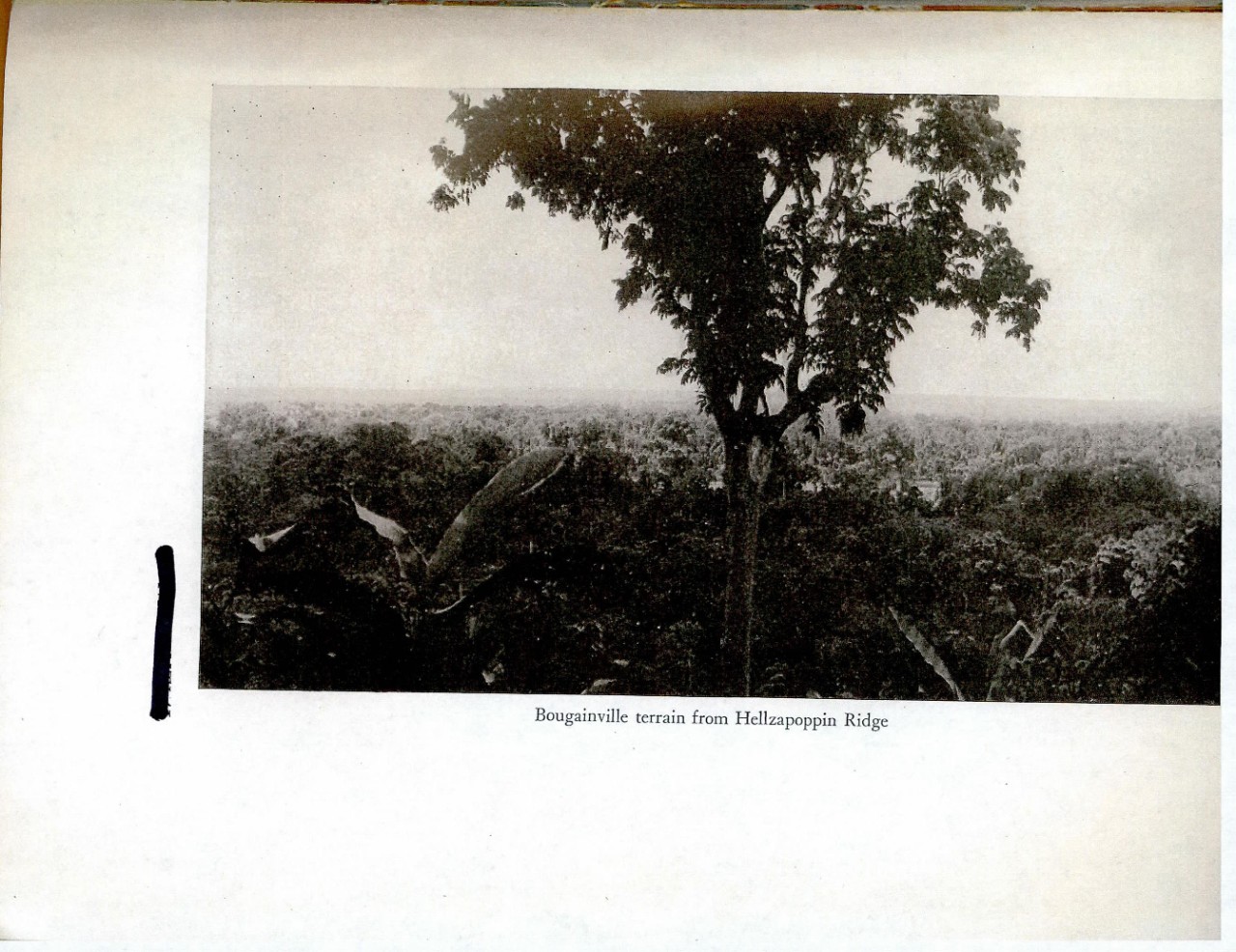

| Bougainville terrain from Hellzapoppin Ridge | |

| Bulldozer attempts to salvage landing craft | |

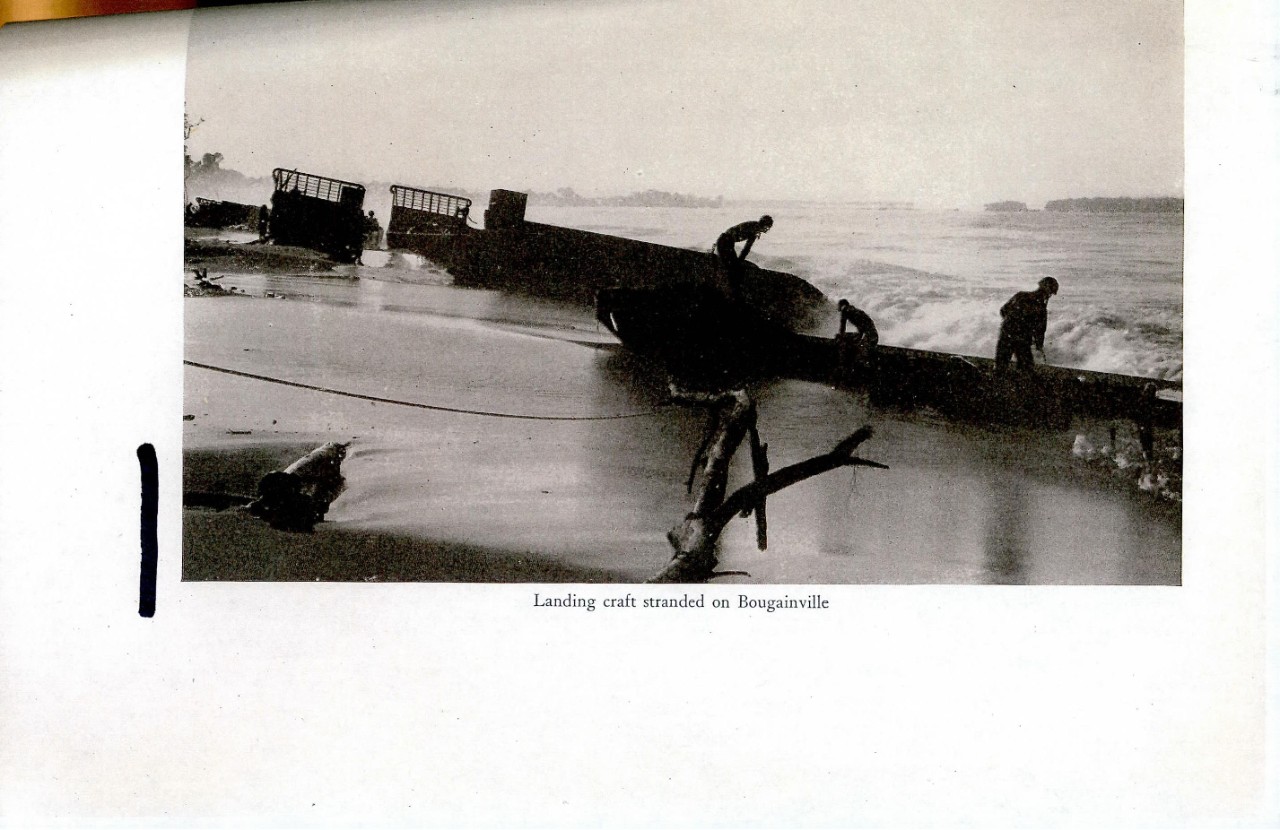

| Landing craft stranded | |

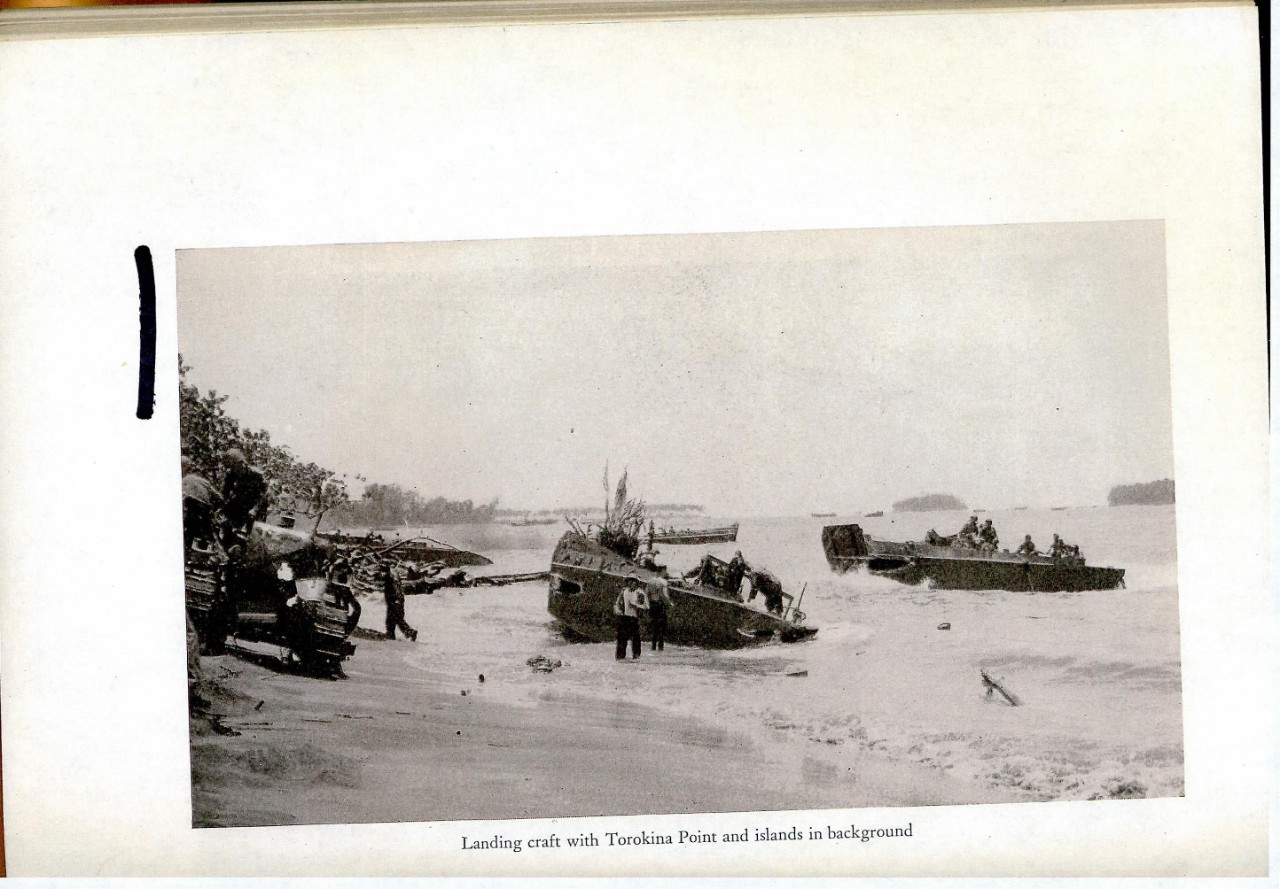

| Landing craft with Torokina Point in background | |

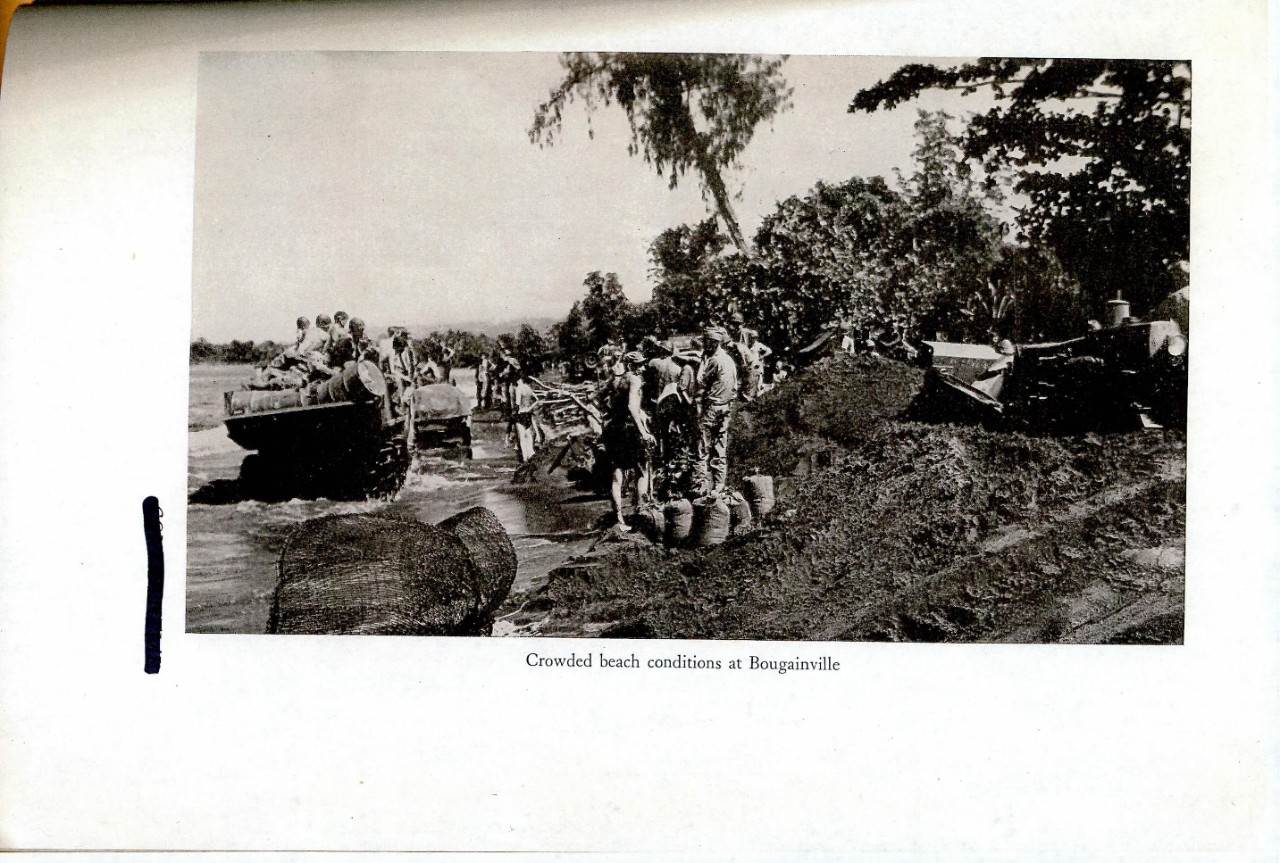

| Crowded beach conditions | |

| Beach markers on Bougainville | |

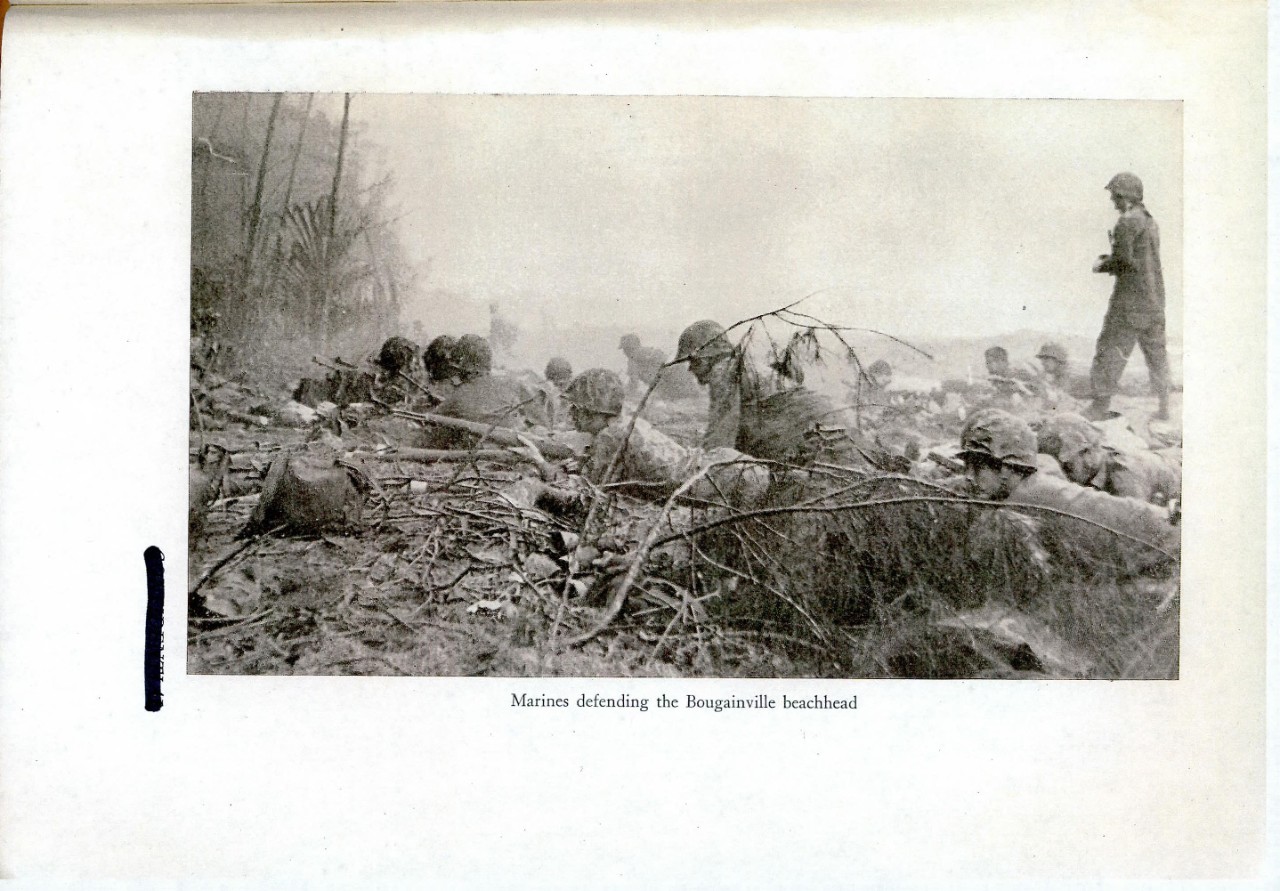

| Marines defending the Bougainville beachhead | |

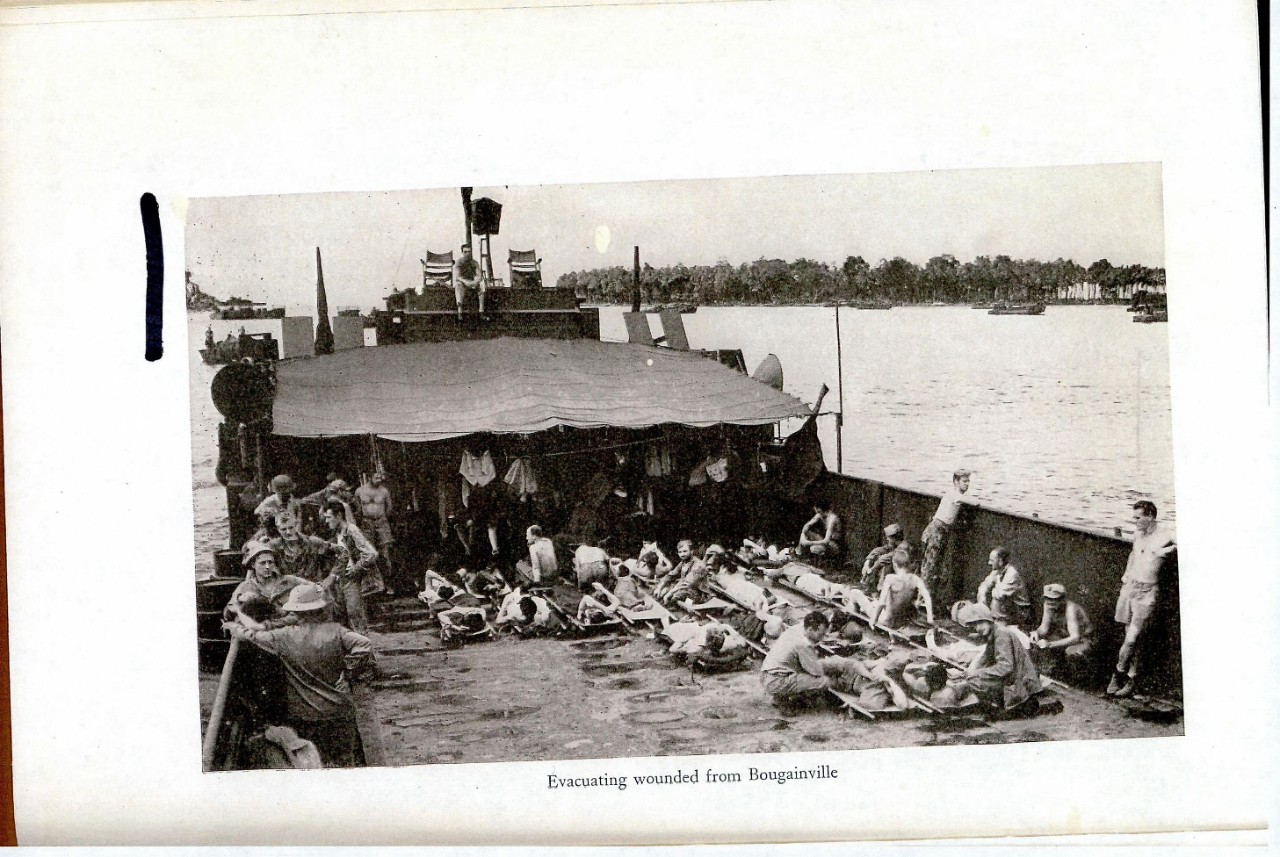

| Evacuating wounded from Bougainville |

IV

CONFIDENTIAL

Contents

| Page | |

| Strategic Considerations | 1 |

| Preliminary Plans | 2 |

| Final Plans | 6 |

| Enemy Situations | 8 |

| Neutralization of Enemy Airfields | 9 |

| Seizure of Treasury Islands | 11 |

| Loading and Approach | 13 |

| Landing and Unloading | 14 |

| Air Attack | 20 |

| The Choiseul Diversion | 23 |

| Buka-Bonis and Shortland Bombardments | 25 |

| Buka-Bonis | 25 |

| Shortland Area | 30 |

| Buka-Bonis Air Strikes | 34 |

| Landing on Bougainville | 37 |

| Preparations | 37 |

| Approach | 39 |

| Shore Bombardment | 40 |

| Landing and Beach Conditions | 41 |

| Air Opposition | 45 |

| Unloading and Retirement | 47 |

| Mine Laying | 48 |

| Battle of Empress Augusta Bay | 49 |

| Refueling | 49 |

| Approach | 50 |

| Battle Plans | 53 |

| Battle Chronology | 55 |

| Initial Attack | 55 |

| Cruiser Gunfire and Radical Maneuvers | 57 |

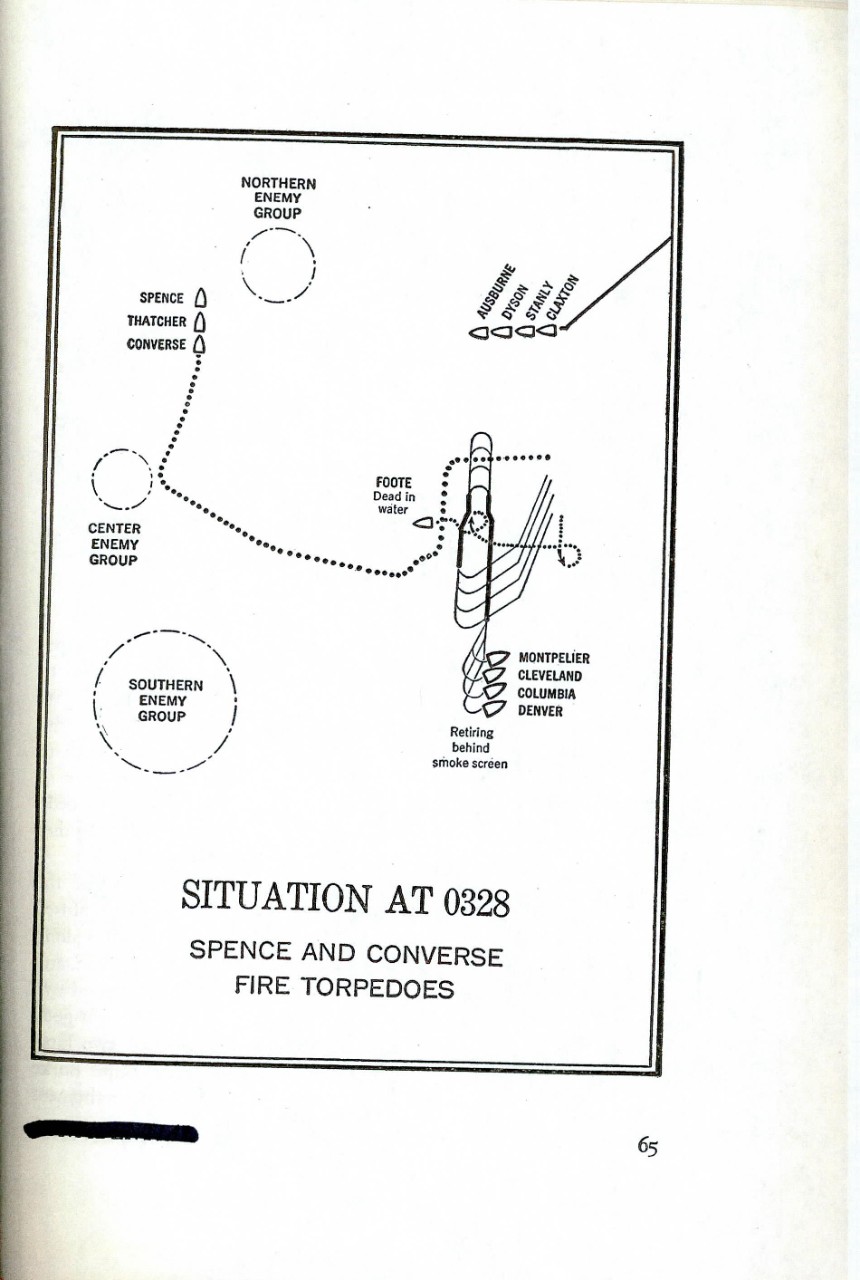

| Destroyer Division 46 | 62 |

| Destroyer Division 45 | 66 |

| Retirement | 69 |

| Anti-Aircraft Following the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay | 71 |

| Conclusion | 75 |

CONFIDENTIAL

V

| Page | |

| Appendix A: Air Strikes on Enemy Air Installations and Strips | 77 |

| Appendix B: Treasury Islands Operation: Task Force Organization | 79 |

| Appendix C: Bougainville Operation: Task Force Organization | 81 |

| Appendix D: Symbols of U.S. Navy Ships | 83 |

| Appendix E: List of Published Combat Narratives | 85 |

CONFIDENTIAL

VI

The Bougainville Landing

And the

Battle of Empress Augusta Bay

27 October-2 November 1943

STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS

AS Early as 11 July 1943 the South Pacific Command had decided that as part of the final phase of the Solomon Islands Campaign an assault should be made upon Bougainville Island, the largest stacle to our forces driving northward through the New Georgia Group; in ours it would provide a base for future operations against the great Japanese base at Rabaul on New Britain.

Bougainville presented problems which were unique in the Solomons Campaign. It is northernmost of the larger islands and has adequate harbors and a terrain favorable for airfields. Moreover the enemy could easily transport reinforcements of men and material from Rabaul and support his operations by air from bases on New Britain, New Ireland, and Truk—all of which were beyond the range of our land-based fighters. Japanese supply and communication routes to the island were well protected and within easy reach of enemy naval establishments at Truk, Kavieng, Buka, Kieta, and minor bases in southern Bougainville and adjacent islands.

The Japanese had had nearly two years in which to construct defenses on Bougainville, as compared with a month in which to prepare against our attack on Guadalcanal. They had built two airfields at the northern end, two on the southern, one in the Shortland area to the south, and one field and a seaplane base on the east coast. Strong ground forces were concentrated in and around southern Bougainville and garrisons were established on the east coast and to the north.

CONFIDENTIAL

I

Between August and October numerous developments in Pacific strategy took place which influenced plans for the Bougainville operation. In the Solomons, South Pacific forces pressing northward and westward, virtually completed the occupation of New Georgia with the capture of Munda on 5 August and landed on Vella Lavella ten days later. In less than two months the occupation of the latter island was completed, and by 9 October the Japanese had been compelled to evacuate the by-passed island of Kolombangara.1 Across the Solomon Sea to the west, Allied forces, carrying the New Guinea Campaign farther into the Huon Gulf area, took Salamaua and Lae in September. On 2 October they captured Finschhafen and thus placed themselves closer to the Japanese base at Rabaul than our South Pacific forces, which were advancing toward it from the southeast.

In the meantime, due east of Bougainville, preparatory steps were being taken to mount the Central Pacific Campaign by the occupation, in August, of additional atolls in the Ellice Islands. Raids preliminary to the Gilbert Islands operations began with an air strike on Marcus Island on the last day of August, followed by a strike on Tarawa Atoll on 18 September and an air strike and bombardment of Wake Island in the first week in October. D-day for the Gilbert Islands landings was to be 20 November, and forces were already being assembled for that purpose while the Bougainville operation was being prepared.

Preliminary Plans

The final conception of the Bougainville operation evolved through a series of preliminary plans which were changed under the impact of a continuously shifting strategic situation. Some of the alterations were drastic departures from the original thinking, and the final plan bore small relation to the first.

The first plan, outlined in a letter of 11 July 1943 from COMSOPAC, Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., envisaged a forthright assault about 15 October on southern Bougainville Island, including the airfields at Kahili and Ballale, the Shortland-Faisi area and Tonolei Harbor. The Commanding General, First Marine Amphibious Corps, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, was put in command of land forces for the operation and instructed to collect and disseminate combat intelligence, initiate detailed

----------------

1 See Combat Narratives, “Operations in the New Georgia Area, 21 June-5 August 1943,” and “Kolombangara and Vella Lavella, 6 August-7 October 1943.”

2

planning, and keep COMSOPAC constantly in touch with the development of plans.

Preliminary study of the mission and of enemy strength in the area indicated that Allied ground forces available would be insufficient for an assault on the strongly defended area of southern Bougainville. Advised of this, COMSOPAC changed the plan on 5 August to limit it to the seizure of Shortland, Faisi, Ballale, and such adjacent islands as were necessary to furnish a base for further operations and to deny enemy air and naval forces the use of southern Bougainville. The tentative start date for the operation was left unchanged.

Both the bolder plan of July and the more limited one of August conceived of the operation mainly as a ground campaign for the seizure of enemy airfields already constructed. Had either of these plans been followed, the Bougainville operation would have proved similar to those of New Georgia and Guadalcanal. As combat intelligence accumulated and the strategic picture developed, it was realized. However, that the enemy was more vulnerable in shipping and in the air than on the ground. When means of striking the enemy where he was weakest and avoiding him where he was strongest were considered, the alternative of seizing undeveloped or weakly-held area and constructing our own fields presented itself. This is precisely what we had done when we landed on Vella Lavella and by-passed Kolombangara on 15 August.

At the request of COMSOPAC, Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon, USA, Maj. Gen. Charles D. Barrett, USMC, and Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson presented a memorandum on 7 September expressing their complete agreement that the attack on the Shortland area should be abandoned, and that the following alternative plan be substituted: (1) Complete the projected Airfields in New Georgia and Vella Lavella; (2) Continue and increase the air effort to neutralize enemy airfields in the southern Bougainville area, and put heavy pressure on airfields in the Buka area; (3) On D-day, simultaneously seize the Treasury Islands and the Choiseul Bay area, install radar equipment at both places, construct airfields on one or both, and establish motor torpedo boat advance bases and staging points for landing craft at both positions. All this was for the purpose of strangling and containing southern Bougainville; (4) Airfields in the Buka area were then to be neutralized by air action. It was recommended that a further advance, after completion of step 4, be made up the northeastern coast following the Choiseul-

3

Kieta axis, or up the southwestern coast following the Treasury Island-Empree Augusta Bay axis. Choice of the line of advance would be determined after reconnaissance of the area and observation of enemy reactions.

Intelligence was gathered by amphibious methods on an unprecedented scale. Ground patrols were landed by submarine, seaplane, and motor torpedo boat to penetrate defended beaches. Careful studies were made of the Shortland area, the Treasury Islands, Choiseul, southern and northern Bougainville, and the Kieta and Numa Numa areas. On the basis of these studies, Buka was rejected as being too distant to permit aircraft fighter cover, Kahili as too strongly defended, and Shortland because of insufficient beach area. Kieta and Numa Numa were discarded because of their strong enemy garrisons and airfields.

On 22 September COMSOPAC issued a warning order, cancelling the preliminary plans of 11 July and 5 August and instructing the Commanding General, First Marine Amphibious Corps to be prepared on or about 1 November to execute either one of two plans. Plan 1 called for the seizure of Treasury Island and the northern Empress Augusta Bay area, Bougainville, and the construction of airfields in the latter area. Plan II was in two phases: (I) the seizure of the Treasury Islands and the Choiseul Bay area, the installation of radars and PT bases at both places and an airfield on Choiseul, in preparation for the second phase; and (2) during the latter part of December 1943, the seizure of an enemy airfield in the vicinity of Tenekau Bay on the east coast of Bougainville, between Kieta and Numa Numa.

COMSOPAC’s operation plan was to be issued later. Admiral Wilkinson was placed in command of the operation and instructed to coordinate detailed planning. General Vandegrift, as earlier, was to be in command of land forces.

The success of the Vella Lavella operation, which by-passed Kolombangara and in a few weeks forced its evacuation without a fight, led to a further re-examination of Solomons strategy. It was though that Plan II, outlined above, would delay unduly the completion of the Solomons Campaign. Moreover, our fighters operating from an airfield on Choiseul would not be able to cover later bomber strikes at Rabaul. It was decided that the operation should look more definitely toward the reduction of the great base around which he Japanese had built the defense of the Bismarck Archipelago-Solomons area. Thoughts that turned to the

4

bolder plan of establishing a beachhead on Bougainville and by-passing the strongholds to the south. Representatives from the staff of COMSOPAC conferred with General Douglas MacArthur, who shared their distaste for a direct assault on the Shortland area, and favored an attack on Bougainville. He requested that Admiral Halsey investigate the possibility of this move.

Tactical and other considerations dictated the selection of northern Empress Augusta Bay, about half way up the western coast of Bougainville, as the objective. It presented, however, a number of disadvantages. The low, swampy, timbered coast had limited protection from onshore winds. There was only a meager network of foot trails, and no satisfactory anchorage for larger vessels. The Cape Torokina area, where the landing beaches were sought, was practically undeveloped. Moreover, some of the nearby native tribes were known to favor the enemy. To offset these disadvantages, defenses in the area were reported to be comparatively weak. Beach trails and inland foot trails were only irregularly patrolled. The Torokina area also appeared to comprise a natural defensive region of approximately eight by six miles. The area was almost equidistant from enemy installations to the north of Buka and to the south in the Shortland area and lay astride enemy communications to Rabaul. These, among other considerations, dictated the selection of Cape Torokina as the site for the beachhead.

The Treasury Islands landing was retained from the earlier plans to provide protection for future convoys to Empress Augusta Bay. The Choiseul phase of the operation was not abandoned, but the determination of its relation to other phases remained to be formulated.

The Bougainville operation was designed as a flanking movement to cut the enemy’s line of communication, avoid a frontal attack, and force the enemy to withdraw eventually from his strongest positions without a fight. In some ways this strategy had been anticipated in the Vella Lavella-Kolombangara operation. But the Bougainville operation was of greater complexity and import. It was designed not only to leave thousands of enemy troops slowly strangling in southern Bougainville, Choiseul, and the Shortland area, but also to advance our air and naval bases so as to enlarge the field of targets to include Rabaul and New Britain, far beyond the immediate objective. Furthermore, unlike the Vella Lavella operation, the Bougainville operation was not intended to conquer an entire island. It was designed simply as the capture of a

5

beachhead, which could hold within its comparatively small perimeter a bomber field, a fighter strip, and an advanced naval base.

The conception was bold, and the risk of provoking violent enemy airland-surface action was calculated and accepted. “Enthusiasm for the plan was far from unanimous, even in the South Pacific,” reported Admiral Halsey, “but, the decision having been made, all hands were told to ‘get along.’”

Final Plans

In his operation plan of 12 October 1943 COMSOPAC set 1 November as D-day. This plan fixed only the major objectives and assigned the major commands. Admiral Wilkinson, who was placed in command of this operation, was directed to seize and hold the Treasury Islands on D minus 5 day and to establish there radars and minimum facilities for small craft. On D-day he was to seize and hold a suitable site in the northern Empress Augusta Bay area, where he was to establish facilities for small craft and construct such airfields as might be directed by COMSOPAC. In addition he was to lay defensive and offensive minefields as directed.

In the same operation plan Admiral Halsey directed Commander Aircraft, South Pacific, Maj. Gen. Ralph J. Mitchell, USMC, to support the operation with land-based planes by providing defensive reconnaissance, air cover, and air support for forces engaged. He was also to provide support by strikes against airfields on Bougainville and against any enemy units threatening the attack force. Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, commander of a carrier task force, was directed to be prepared to support operations of the land-based planes by strikes against enemy bases and also to base aircraft ashore when directed. Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill, in command of a task force of cruisers and destroyers, was directed to destroy enemy surface vessels which might threaten Admiral Wilkinson’s operations or the South Pacific position, and to attack enemy bases as directed by COMSOPAC. Submarines under command of Capt. James Fife, Jr., were to attack enemy shipping and surface units. Prior to and during the operation, aircraft of the Southwest Pacific were to conduct striking missions against Rabaul.

Even as late as 12 October the final conception of the Choiseul phase of the operation was still unformulated; in fact, in his operation plan or that date COMSOPAC directed Admiral Wilkinson to be prepared, on five days notice, to establish PT advance bases in the northwest half of Choi-

6

seul. This conception was later abandoned. It was feared, however, that since the Treasury Islands were on a direct line to the proposed Bougainville beachhead, the landing there might serve to point out our main objective to the Japanese and cause them to reinforce the area.

To throw the enemy off the scent, the Choiseul landing was retained, though midified into a diversionary movement. The size and position of Choiseul would suggest its use as a base for attack against either Shortland or Bougainville—and if the latter, the base would suggest a landing on the east rather than the west coast. The last major change in the operation plan, that adopting the Choiseul diversion, was made on 22 October. Marines were to be landed at Voza, Choiseul, on D minus 5 day, or the night of the day of the Treasury landing. They were to conduct a raid lasting about twelve days, striking the enemy at several places and attempting to confuse him. As the diversionary movement was described by Maj. Gen. Roy S. Gieger, USMC,2 it was ‘a series of short right jabs designed to throw the enemy off balance and conceal the real power of the left hook to his midriff at Empress Augusta Bay.”

The Third Marine Division, reinforced, Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage commanding, was assigned the northern Empress Augusta Bay mission. These troops conducted landing exercises on beaches of the New Hebrides and Guadalcanal during the period 17-19 October. The Eighth New Zealand Brigade Group, reinforced, commanded by Brigadier R.A. Row, was assigned the Treasury Islands operation, and carried out landing exercises on Florida Island on 14-17 October. The force for the Choiseul diversion was the 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Victor H. Krulak.

Admiral Wilkinson, Commander Third Amphibious Force, had the responsibility for the detailed planning of the naval operations. His operation plan of 15 October, amended and elaborated by his operation order of the 18th, included plans for logistics, naval gunfire, minesweeping, minelaying, communications and boat pools along with schedules for debarkation, ship movements and cruising dispositions for the Treasury and Empress Augusta Bay operations, The ships and craft at Admiral Wilkinson’s disposal for the two landings were divided into the Northern Force, for Empress Augusta Bay, and the Southern Force, for the Treasury Islands. Admiral Wilkinson designated Rear Admiral George

------------------

2 General Geiger relived General Vandegrift as Commander First Marine Amphibious Corps on 9 November 1943.

7

H. Fort commander of the latter force, and retained command of the Northern Force himself.

Enemy Situation

Every effort was made to encourage the enemy in the belief that our target was the Buin-Shortland area. He learned of our Shortland reconnaissance party, and undoubtedly took note of low-flying photographic missions and bombing attacks which assisted him toward the same conclusion. To the satisfaction of all, it was observed that he was moving reinforcements, artillery, and heavy equipment into the area, rapidly replacing aircraft combat losses (at least in September), developing existing air cases, and also constructing new ones.

Our intelligence revealed that Japanese air reconnaissance was active in the Bougainville area, that numerous observation posts were located along the coast and on outlying islands, and that patrolling was active along the shoreline. Air and submarine attack was to be expected, and surface attack was possible. The natives, except those on Treasury Island, were believed to be pro-Japanese. Our forces were warned particularly against natives in the Empress Augusta Bay area, who might appear friendly but might well be scouts for the enemy.

Enemy naval strength in the Rabaul-Solomons area as of 11 October was estimated to be one heavy cruiser, one light cruiser, eight to ten destroyers, twelve submarines, twenty-one patrol craft, plus necessary auxiliaries, numerous barges, and some PT boats. Large naval forces were at Truk.

Estimated enemy ground strength as of the same date was as follows:

| Bougainville and Shortland Islands (including air, labor, and service troops) | 35,000 |

| Choiseul Island (including evacuees) | 2,000 |

| New Britain (Rabaul area) | 56,000 |

| New Ireland | 5,000 |

| Total | 98,500 |

As for the troops in the Bougainville area, 5,000 were thought to be in the northern sector (Buka area) , 5,000 in the eastern sector (Numa Numa-Kieta) , 17,000 in the southern sector, 5,000 to 6,000 in the Shortland Islands, 3,000 in Ballale and surrounding islands, and 132 in the Treasury Islands. All indications were that the enemy considered the defense of southern Bougainville of prime importance.

8

As of 9 October enemy air strength was estimated to be 160 fighters, 120 medium bombers, 66 dive or light bombers, and 39 float planes based on Bougainville, on New Ireland, and in the vicinity of Rabaul. Approximately 72 per cent of these planes were thought to be based in the Rabaul area, 20 per cent in the Bougainville area, and eight per cent on New Ireland. It became increasingly evident that under severe punishment by Allied planes the enemy was gradually displaying less confidence in his ability to protect his air bases in southern Bougainville. The strength of aircraft at Buka continued high, but concentrations at Kahili, Ballale, and Kara began to dwindle—a clear recognition of Allied air and naval superiority.

In the vicinity of Empress Augusta Bay, the Japanese were believed to have an outpost located in the Cape Torokina area with an estimated strength of not more than 100 men and possibly some antiaircraft machine guns. A small observation post was believed to be located near the Laruma River. Small forces were also known to be near Mawareka, with reserves, including artillery, at Mosigetta, totaling in all about 1,000 men. Large forces were known to be located in the Buka, Kieta, and Kahili areas.

In late October there were indications that the enemy was preparing to counter further by-passing or flanking movements by increasing the number of mobile troops available to repulse landings on lightly defended areas. About the same time, intelligence photographs disclosed military activity at Cape Torokina, including emplacement of antiaircraft positions, and construction of a slit trench and some minor buildings. This was in no wise alarming, however, and indicated no enemy awareness of the impending assault upon the position.

Neutralism of Enemy Airfields

Between out northernmost airfield at Barakoma and the proposed landing site at Cape Torokina were three enemy airfields. Kahili, a large and well-developed airfield, lay at the southern tip of Bougainville, and Kara, a new strip, lay seven miles inland from Kahili and to the northwest. Ballale airfield was on the island of Ballale thirteen miles southeast of Kahili. Twenty-eight miles north of Kahili on the east coast of Bougainville was located Kieta airdrome, nonoperational at the time, and nearby was Kieta seaplane anchorage. Radar, radio, and other installations were grouped around these fields. To the northwest at the

9

tip of Bougainville Island was Bonis airstrip, and just across a narrow passage was Buka airstrip, on Buka Island.

The campaign to neutralize these airfields, or at least those at the southern end of Bougainville, by means of land-based aircraft bombing, was intensified on 15 October 1943. From that date through 31 October planes based at Barakoma and Munda, under ComAirNorSols, Brig. Gen. Field Harris, USMC, carried out an average of approximately four attacks a day, ranging in strength from 100 planes down to strafing attacks by a few fighters.3 Kahili was subjected to 18 attacks, Kara to 17, Ballale 6, Buka 7, and Kieta 2 within this period. On an average day of four attacks such as 23 October, 59 tons were dropped on Kara and 68 tons on Kahili.

Enemy air activity in the South Pacific area was greatly reduced during the month. Enemy sorties declined from 801 in September to 495 in October, while his losses increased from 148 in September to 173 in the latter month. By comparison, our aircraft in the South Pacific flew 3,259 sorties in October, with a loss of 26 planes in combat. More than 90 per cent of our air effort was directed against enemy land targets---principally in the southern Bougainville area.

The success of this effort is attested by the fact that all enemy airfields in the southern Bougainville area were practically neutralized by the end of October, thereby removing one of the major hazards to be projected operations against the Treasury Islands, Choiseul, and Bougainville.

In the meantime the Fifth Army Air Force of the Southwest Pacific area, under command of Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, USA, intensified the heavy air offensive it had mounted against the enemy in mid-August. A considerable part of this offensive was aimed at the Japanese base at Rabaul. On 12 October Allied planes struck the Rabaul area in one of the heaviest attacks ever made in the Southwest Pacific theater up to that time. Heavy and medium bombers with strong fighter protection dropped 350 tons of bombs and expended 250,000 rounds of ammunition in strafing. Allied medium bombers in low-level attacks on three airfields in the area destroyed an estimated 100 aircraft on the ground, and damaged 51 others before they could take off. Of the 40 enemy fighters able to attempts interception, 26 were reported shot down in combat over the targets. During the same attack our heavy bombers struck at enemy shipping in the harbor, sinking three destroyers, three medium-sized merchant vessels

-----------------------

3 See Appendix A for detailed tabulation of these air attacks.

10

totaling 18,000 tons, 43 small cargo vessels of less than 500 tons each, and 70 harbor craft. In addition, a submarine, a submarine tender, a destroyer tender, and another merchant ship were hit and seriously damaged. Wharves, warehouses, barracks, administration buildings, and fuel and ammunition dumps were demolished or heavily damaged. Our losses amounted to only five planes.

In the week that followed, Allied planes destroyed or damaged approximately 250 Japanese aircraft in the New Guinea-New Britain area. Of these, 138 were shot down in air combat, 36 were probably destroyed in combat, 70 were claimed to have been wrecked on the ground, and another 12 damaged on the ground. Included in this air activity was a second attack on the Rabaul area on 18 October, this time by 55 B-25’s. Our force claimed to have destroyed 24 enemy aircraft in air combat and 36 on the ground. It also reported the sinking of one enemy destroyer, one gunboat, one medium-sized cargo vessel, and the probable sinking of one gunboat and another medium-sized cargo vessel.

Allied planes carried out four additional attacks on the Rabaul area before the end of October: one on the 23rd, another on the following day, one on the 26th, and one on the 29th. The size of the attacking forces ranged from 60 to 145 planes. Our forces claimed to have destroyed 226 enemy aircraft in air combat or on the ground and probably destroyed 106 others. Even allowing for considerable inaccuracies in reporting planes destroyed on the ground, it is evident that the Japanese suffered heavy losses as a result of these attacks. While the enemy rapidly replaced his losses, his menace to our Bougainville landing was somewhat reduced by the end of October.

SEIZURE OF TREASURY ISLANDS

In his operation plan issued 12 October 1943, Admiral Halsey had directed that Admiral Wilkinson, in addition to other operations, “seize and hold Treasury Islands on Dog minus 5 day, capture and destroy enemy forces, and establish thereat radars and minimum facilities for small craft as necessary.”

Prior to the issuance of this order, on the night of 22-23 August, a submarine had landed a reconnaissance party of Naval and Marine officers and men on Mono Island of the Treasury Group. These men were evacuated by the same means on the night of 27-28 August. Their report indicated that the best landing beach on the island was in Blanche Harbor

11

between the Saveke River mouth and Falamai Point. This beach appeared suitable for all types of landing craft, and had an ample water supply nearby. The additional advantage of sufficient dispersal and bivouac areas for troops gave this beach superiority over all others examined. The reconnaissance party saw signs of enemy patrols and activities, but no Japanese were sighted. Beaches Orange One and Ornage Two were therefore located by the operational orders between the mouth of Saveke River and Falamai Point. Beaches Purple One, Two, and Three were located on the north shore of Stirling Island, where no opposition was anticipated. In addition, Beach Emerald was selected at Soanotalu, on the northern shore of Mono Island.

Admiral Wilkinson on 15 October designated Rear Admiral George H. Fort as Commander Southern Force in command of the Treasury operation. MTB’s based at Lambu Lambu, Vella Lavella and at Lever Harbor on northern New Georgia were to screen the approach by a picket line from the Shortlands to Choiseul. He also made the following ground units, under command of Bigadier Row, NZEF, available for the operation:

8th New Zealand Brigade Group (less certain detachments).

198th Combat Artillery (AA) less detachments and one provisional battalion.

Detachment Headquarters, ComAirNorSols, including Argus 6.4

2nd Platoon, Company A, 1st Corps Signal Bn., IMAC.5

Advanced Naval Base:

Communication Unit No. 8.

Boat Pool No. 10.

Company A, 87th Construction Battalion.

1st Battalion, 14th New Zealand Brigade (in reserve).

The New Zealanders were seasoned veterans who had participated in the campaigns of North Africa, Greece and Crete.

Admiral Halsey directed the task force commanded by Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill to cover the operation from surface attack. He also

---------------------

4 The first Argus unit was shipped overseas in March 1943. By the middle of that year sufficient combat experience had been obtained to permit a redefinition of the mission of an Argus unit and to justify the reorganization of the unit so that it might more efficiently perform its functions. Its purpose has been described as follows: “To provide, during the development stage of a United States Naval Base, a comprehensive air warning, surface warning, and fighter direction organization which will coordinate all radar operations under the Area Commander.” This conception is much broader than originally contemplated. The complement of an Argus unit is approximately 20 officers and 178 men.

5 First Marine Amphibious Corps.

12

directed shore-based aircraft to support the operation by furnishing air cover and support, and to neutralize enemy airfields in the Bougainville area.

In order to obtain last minute information a reconnaissance party of two New Zealand noncommissioned officers and some natives was landed by PT boat on Mono Island the night of 21-22 October. This party reported that, according to friendly natives, the enemy had recently landed reinforcements and that his strength was about 225 men; that medium caliber guns had been emplaced on both sides of Falamai Point; that machine guns were emplaced on Mono Island along the approaches to the landing beaches; that there was an observation post at Laifa Point with direct wire communication with the radio station near the Saveke River; and that Stirling Island was unoccupied by the enemy. The reconnaissance party, evacuated the night of 22-23 October, brought with them some Mono Island natives to act as guides for the landing.

On the night of 25-26 October an advance party of New Zealand noncommissioned officers and some natives landed on Mono. Their mission was to cut communication lines between the observation post at Laifa Point and the radio station just prior to the landing.

Loading and Approach

Transport units under Admiral Fort were divided into five groups, each with its tactical commander.6 The First Transport Group under Commander John D. Sweeney, ComTransDiv 12, consisted of eight APD’s screened by the Eaton, Pringle, and Philip. The Second Transport Group, under Captain Jack E. Hurff, ComDesRon 22, was made up of eight LCI(L)’s and two newly converted LCI gunboats screened by the Waller, Cony, Saufley, Adriot, Conflict, and Daring. The Third Transport Group, under Commander James R. Pahl, ComDesDiv 44, consisted of two LST’s screened by the Conway, Renshaw, and YMS’s 197 and 260. The Fourth Transport Group, under Lt. (jg) Martin E. Bergstrom, was composed of one APc and three LCT’s screened by two PT boats, and the Fifth Transport Group under Lieut. James E. Locke, consisted of APc, six LCM’s, and an aircraft rescue boat.

-------------------

6 For task group organization see Appendix B.

13

The five transport groups were loaded and departed independently, so timed as to arrive at Blanche Harbor on 27 October as follows:

Unit |

Depart | Arrive 27 October |

| 1st Transport Group | Guadalcanal 1230 26 October | 0520 |

| 2nd Transport Group | Guadalcanal 0400 26 October | 0555 |

| 3rd Transport Group | Guadalcanal 1930 25 October | 0640 |

| 4th Transport Group | Rendova1200 26 October | 0830 |

| 5th Transport Group | Lambu Lambu 1900 26 October | 0830 |

Five days prior to the loading, the APD’s and LCI(L)’s embarked troops and conducted a landing rehearsal.

The several groups made independent passages without incident, except that a flare was dropped near the LCI gunboats between Simbo and Treasury Islands. The groups passed before dawn, as scheduled, in the area between Simbo and Treasury Islands. The element of surprise was extremely important, since there were reported to be approximately 25,000 Japanese in the Shortland-Buin area with 83 barges at their disposal. These forces could have heavily reinforced the treasury Islands in a few hours. Complete radio silence was therefore maintained except for three orders by high frequency voice radio (TBS), which included an order delaying H-hour by 20 minutes.

Since practically every unit venturing west or north of Vella Lavella at night previous to this operation had been quickly detected by enemy float-plane snoopers, it was considered almost certain that our approach would be discovered during the night; but despite the flare dropped near one of the smaller task units, it seems probable that the enemy made no contact and that surprise was fairly complete. The covering cruiser group under Admiral Merrill, to the westward, was discovered by snoopers, however, and many flares and float lights were dropped near the formation. “Fortunately,” as Capt. Arleigh A. Burke, ComDesRon 23, remarked in his report, “the bogie became so interested in playing ‘hide and seek’ with the [covering] task force that is believed he did not see the landing forces coming up towards Treasury Island from the South.”

Landing and Unloading

At 0540 the seven APD’s of the First Transport Group lay to 1,300 yards off Cummings Point, Stirling Island, bearing 060o T., just south of

14

the entrance to Blanche Harbor, and commenced the debarkation of troops into boats. Sunrise was approaching, with visibility good, the sky partly cloudy, wind northeast, force 2. The Eaton, as fighter director ship, proceeded to her station four miles off the harbor, while the Pringle and Philip began their shore bombardment within five minutes after the transport group arrived. The air spotter was already over the targets, and at 0600 the fighter cover of 32 planes arrived on station.

Since it was impracticable to operate destroyers in the narrow waters of Blanche Harbor, the fire support area was located west of the entrance. All firing at this stage was on pre-arranged targets. Preparatory fire of the Pringle was delivered approximately according to schedule, with good battery performance. No assistance, unfortunately, was obtained from the air spotter, who subsequently reported radio material failure responsible for his inability to aid the gunners. While it later developed that much of the Pringle’s fire was a little too far back from the beach to be of maximum effectiveness, she nevertheless covered her assigned area reasonably well. The preparatory fire of the Philip, which suffered several gun casualties, was disappointing in accuracy, timing, and quantity. At 0623, three minutes before the boats of the assault wave hit the beach, the destroyers ceased fire. The Pringle maneuvered clear of the fire support area to patrol west of Blanche Harbor, while the Philip proceeded independently to patrol on east-west courses approximately 6,000 yards south of Stirling Island.

In the meantime the loaded boats from the APD’s had rounded Cummings Point under the arched tracers of 5-inch shells, the sight of which “gave confidence to the boats.” Two newly converted LCI (L) gunboats had left the Second Transport Group during the night and escorted the landing boats of the APD’s into the harbor. The major assault was to be made on Beach Orange at Falamai, the only suitable beach of the northern coast of Mono Island. A smaller force was to land on the Purple beaches of Stirling Island where no opposition was expected. In order to reach Falamai it was necessary to proceed two miles up the harbor, which averaged only about 1,000 yards in width. Since no enemy resistance was expected on Stirling Island, and Japanese machine-gun positions were reported along the southern coast of Mono Island as well as on both sides of Falamai Peninsula, the assault wave was routed close to Stirling Island to a point just beyond Watson Island, where the boats bound for the Orange beaches turned left.

15

Before that point was reached, the boats from the Stringham and Talbot turned right and proceeded independently to Beaches Purple 2 and 3. The New Zealand troops were landed on Stirling Island without opposition. Although the beaches were bad, no difficulty was encountered.

Resistance quickly developed on the opposite side of the harbor, however. Despite air bombing the previous day and bombardment by the fire support group the approaching boats were fired on by a number of machine guns, some mortars, and a twin-mount 40-mm. automatic gun located at Falamai. Fortunately only one boat was disabled by gunfire although several were perforated by bullets. Five naval personnel and several New Zealand troops were wounded on the way in.

At this point the newly converted LCI(L) gunboats, which had arrived from Noumea just in time to participate in this operation, saw their first action. Equipped with 3-inch guns, two of these craft accompanied the assault boats, one preceding and one on the flank. Just prior to the landing one of the gunboats rounded Watson Island and knocked out the 40-mm. twin-mount, thus saving many lives. The gunboats also returned the fire of several enemy machine guns. Their performance during this operation, for which they had no time to train, was described by Admiral Fort as “especially creditable.” They continued to operate in the harbor throughout the morning.

The assault wave hit the beach at H-hour (0626) exactly. The wave consisted of 16 LCP®’s carrying 640 men to the Orange beaches. The APD’s lay in the transport area for about two hours, landing 1,600 men and at least 80 tons of stores. In the meantime, the McKean, which had left the formation at 0430 and proceeded independently to Beach Emerald at Soanotalu on the north coast of Mono to land troops, returned to the transport area ay 0708 and reported that the landing was successful and unopposed. At 0800 the APD’s departed under the escort of the Conway and Renshaw.

The Second Transport Group, which included eight LCI(L)’s, completed its approach by 0630, and the Cony and Waller took stations as fighter director ships. The LCI(L)’s, under Comdr. J. McDonald Smith, rounded the west end of Stirling Island at 0630 in two columns as follows: port column---Nos. 222 (F), 334, 24, and 336; starboard column—Nos. 61, 67, 69, and 330. The landing craft were preceded by the AM’s Adroit, Conflict, and Daring. The columns on their way up the harbor passed the Higgins boats of the APD’s returning from the beaches and observed

16

shore fire converging on the gunboats accompanying the landing craft, all of which were vigorously returning the fire. The LCI(L)’s opened fire in order of station in column as they came abreast of the enemy installations, silencing some of them. Three of the landing craft in the right column, Nos. 61, 67, and 69, swung to starboard after they were midway down the channel and proceeded to the Purple beaches on Stirling Island. The remaining craft swung to port to approach the Orange beaches, on which they let go their ramps about 0647.

The LCI(L)s were under rifle and mortar fire on the Orange beaches throughout their unloading period. Four shells exploded near No. 334, and two near the stern of the No. 330 as she was retracting. Observers on LCI(L) 24 spotted an active pillbox some 60 yards off her port bow, an inactive one about 20 yards off her starboard bow, and a very active pillbox some 80 yards off her starboard bow. They were all well camouflaged with netting and foliage and blended into the jungle background. Two dead men lay before one pillbox, and others lay at the water’s edge. Soon two Japanese snipers tumbled from the tops of coconut trees near the beach.

In spite of this opposition, the eight LCI(L)’s achieved the rather remarkable feat of debarking 1,600 troops and 150 tons of cargo within 35 minutes. LCI(L) 330 completed the debarkation of 299 officers and men and 14 tons of heavy equipment and supplies in 14 minutes, which, according to Admiral Wilkinson “would be considered an outstanding performance even without any opposition from the beach.” There were no casualties among naval personnel and no damage of any consequence to the craft. By 0730 the LCI(L)’s were underway with the AM’s for Guadalcanal escorted by the Waller, Pringle, and Saufley.

About 0715 LST’s 399 and 485 of the Third Transport Group stood in to Blanche Harbor preceded by two YMS;s sweeping for all types of mines. Seeing no evidence of a beach party or beachmaster, the commanding officers selected their own landing sites and beached exactly on schedule, at 0735, LST 300 at beach Orange 1, and No. 485 at Orange 2. Five minutes later both ships were subjected to heavy fire from one or more 80-mm. Mortars, two or more 30-mm. mountain guns, and considerably sniping with small arms. Within the ensuing 50 minutes LST 399 received two direct hits. One on the port side amidships tore a three-by-four foot hole in the bulkhead and started a fire, which was quickly extinguished; another hit on the breech of a 40-mm. gun destroyed the

17

gun and killed three of its crew. LST 435 received two direct hits on the forecastle and several near hits. These hits wounded eight men, one of whom subsequently died, but did relatively minor damage to the vessel.

LST 399 found herself in especially difficult straits. She was bracketed by a score of shells from the mortar that made the two direct hits. It was also discovered that a large, well-covered, active pillbox was located about eight yards from her port bow door, and that Japanese snipers were quite active. During a lull in the firing the ramp was lowered, but the first man of the ship was shot down, and the two who followed were dropped in their tracks. It became necessary to close the ramp for protection. Several New Zealand troops were standing on shore out of the arc of the pillbox’s fire ineffectually firing Bren guns into the pillbox. None of the LST’s forward automatic weapons could be brought to bear on the box. Personnel aboard ship opened up on the snipers and brought one down. But at that point they received orders from the beach to cease firing. It had become apparent that the soldiers ashore were not going to silence the pillbox, which had become so active that all hands aboard ship had to take cover. No unloading could be attempted until the pillbox was silenced.

At 0815 the LST requested permission to leave his beach, but received the reply, “Not granted.” Whereupon, a resourceful New Zealander mounted a D-8 bulldozer, and with the great blade raised high to protect him from fire, he rolled heavily down the ramp, several soldiers covering him with Bren guns as he came out. He then worked to the “blindside” of the pillbox, lowered his blade, and ploughed the pillbox and its seven occupants under the earth, “tamping it down well all around, effectively silencing its fire.”

Both LST’s began unloading operations at 0830. In the meantime the Eaton, with Admiral Fort, entered the harbor in an attempt to silence the mortar fire. However, she could not locate the battery, which ceased fire when the Eaton approached. The Philip, on station south of Stirling Island, was assigned a target by the shore fire control party and fired five salvos. There was no more martar fire for hours, though whether as the result of hits by the Philip was not known.

The Fifth Transport Group, consisting of one APc, six LCM’s, and an aircraft rescue boat, arrived off the western entrance of the harbor about 1830, and the Fourth Transport Group, composed of one APc, three LCT’s, and a screen of two PT boats, arrived about 1850. Both

18

groups were ordered to report to Commander Naval Base, Treasury Islands, for beaching and unloading assignments.

Unloading from LST 399, which was the task of a detail of officers and men from the New Zealand Brigade Group, proceeded well at first, but after the mobile equipment was ashore the unloading came to “an almost abrupt halt.” It was necessary that unloading be speeded by hand, since the ship never had more than three trucks and some jeeps. Many of the unloading crew were soldiers who had just come back from jungle fighting, and were not easily convinced that unloading by hand was necessary. LST 485, for lack of bulldozer, road, or unloading area, also had to resort to unloading by hand.

At 1120 mortar fire was reopened from a new position on the hillside about 500 yards off the bow of the No. 399, which was bracketed and then hit on the port side. Shells continued screaming over the forecastle and striking the beach, and at 1125 another shell struck the ship on the port side, this time in the capstan control room, wrecking the capstan machinery. A few minutes later, on about the 20th salvo, the mortar (or mortars) registered a direct hit on a large ammunition dump at Falamai. A violent explosion knocked men off their feet on Beach Orange 2, fired the native village, and set off small arms dumps. Burning debris, shrapnel from exploding 90-mm. shells, and exploding pyrotechnics covered the forward part of LST 399, so that the whole forecastle seemed on fire. He heat grew so intense that the forward guns had to be abandoned, and when it was noticed that the heat was blistering the paint on the starboard bow, the forward magazine was flooded. Hoses were manned up forward, by means of which several clusters of fire on the deck were extinguished. The commanding officer of LST Group 15, Comdr. Vilhelm K. Busck, then signaled LST 399 to retract and rebeach 50 yards to the west, which she promptly did.

At 1155 the Philip and the two LCI(G)’s entered the channel in an attempt to silence the mortar fire, but by the time they had established contact with the shore party the mortar had ceased firing. Mortar fire was never resumed.

Commander LST Group 15, after getting unloading started again on LST 485, proceeded to LST 399 where he found the unloading detail demoralized by the previous shelling. With the aid of a New Zealand officer he finally got some work under way though it went forward slowly. Upon rebeaching, LST 399 found that her forward electrical

19

apparatus had shorted out, and that the ramp had to be lowered by hand. At 1515 Comdr. Busck was again called back to the ship by an appeal for him to use his authority to speed the work of discharging cargo. Few minutes after he arrived bogies were reported; a Zeke came over pursued by two P-38’s, and DDs offshore opened a gun-plane duel. For a time it was impossible to control the unloading parties.

By 1600 the enemy planes were driven off, and unloading was resumed, continuing until after dark. At 1841 LST 485, having completely unloaded and retracted, lay to off the stern of No. 399 to protect her sister ship. LST 399 reported at 1902 that unloading was at a standstill, although she still had 20 tons of cargo aboard and was under orders to unload completely. Finding it impossible to resume unloading, she retracted at 1943 and both LST’s stood out of the channel, led by the Philip and accompanied by the two YMS’s. When LST 399 was about 1,000 yards from the beach she received reports of bogies and heard enemy planes overhead. Soon thereafter she saw the beach she had just left go up in a huge mass of flame, eight or ten bombs having been dropped.

Air Attack

Shortly before the air attack on the LST’s in the afternoon, the Philip had been operating in the restricted waters of the harbor, where she was in a vulnerable position. She was given ample warning, however, by the fighter director ship Cony, which picked up the bogies by SC-2 radar at 1508, distance 47 miles. The Philip promptly stood out of the harbor, and the Cony increased speed to 30 knots.

Fighter director personnel on the Cony plotted four groups of enemy planes approaching the area. Basing their estimates on the number of raid tracked and on the radar reports, fighter directors estimated that there were from 30 to 40 Val dive bombers and 50 to 60 Zeke and Hamp fighters. Our air forces consisted of 16 P-38’s on station divided into two groups of eight each, one at 20,000 feet and one at 25,000 feet. We also had 16 P-40’s, all at 10,000 feet, and eight P-39’S at 10,000 feet. We had eight P-38’s and eight P-40’s orbiting in the general area 15 miles northeast of the Treasury Islands. The other flights were orbiting in a general area 15 miles northwest of the islands. The fighters were vectored out and constantly fed new plots. Three of the enemy groups were apparently intercepted. Several ‘tally-ho’s” were heard, but no information on any of the raids was given by any of the aircraft in the 12 divisions.

20

under the Cony’s direction. Ship’s officers and men, however, reported seeing many enemy aircraft shot down, Our fighter planes claimed to have destroyed 12 enemy planes and reported no losses themselves. The attack was not turned back, however.

At 1525 the Cony sighted a large formation of horizontal bombers approaching from the west on a course that would take them over Blanche Harbor. Our fighters were engaging the enemy bombers and were seen to shoot down four or five of them. Seventeen enemy planes were counted as the formation closed. Our fighters were still engaging the bombers when they began unloading bombs. One large geyser was seen in the western entrance to the harbor, but this attack was not pressed home because of the successful interception.

A few minutes later, at 1532, a group of Vals attacked the Cony and Philip from the southwest. The planes were not intercepted before they reached their attack position. They came in out of the sun in an attack that the Philip described as “the best coordinated and severest this ship had experienced.” The Philip maneuvered at high speed with full rudder throughout the attack, firing on each plane in turn with her main battery and automatic guns. A number of 20-mm. hits were observed, and one plane was seen trailing white smoke. The planes followed close on one another, making runs from port quarter to port bow, dropping their bombs, and levelling off to starboard. Approximately 12 bombs landed from 15 to 100 yards off the starboard side, but none of them hit the Philip.

Some ten or twelve planes attacked the Cony in three or four waves from different sectors. Maneuvering in a series of radical turns, the Cony opened fire with her main battery and automatic weapons on each group. At 1533 the crew of No. 5 gun reported a shell jammed in the gun, which had to be drenched down the bore and outside. The Cony shot down five planes during the attack—one by 5-inch gunfire, and four by 40- and 20-mm. One other was possibly shot down and three were damaged.

About six bombs fell within 100 yards of the Cony. Then at 1534 two bombs struck her main deck aft abreast No. 4 gun. One of the bombs hit the starboard main deck at frame 163, one foot inboard, and exploded on contact; the other hit and penetrated the port main deck at frame 157, eight feet inboard, angled through bulkhead 157 and the longitudinal bulkhead between compartments C-202-E and C-4-F and exploded in the

21

under the Cony’s direction. Ship’s officers and men, however, reported seeing many enemy aircraft shot down, Our fighter planes claimed to have destroyed 12 enemy planes and reported no losses themselves. The attack was not turned back, however.

At 1525 the Cony sighted a large formation of horizontal bombers approaching from the west on a course that would take them over Blanche Harbor. Our fighters were engaging the enemy bombers and were seen to shoot down four or five of them. Seventeen enemy planes were counted as the formation closed. Our fighters were still engaging the bombers when they began unloading bombs. One large geyser was seen in the western entrance to the harbor, but this attack was not pressed home because of the successful interception.

A few minutes later, at 1532, a group of Vals attacked the Cony and Philip from the southwest. The planes were not intercepted before they reached their attack position. They came in out of the sun in an attack that the Philip described as “the best coordinated and severest this ship had experienced.” The Philip maneuvered at high speed with full rudder throughout the attack, firing on each plane in turn with her main battery and automatic guns. A number of 20-mm. hits were observed, and one plane was seen trailing white smoke. The planes followed close on one another, making runs from port quarter to port bow, dropping their bombs, and levelling off to starboard. Approximately 12 bombs landed from 15 to 100 yards off the starboard side, but none of them hit the Philip.

Some ten or twelve planes attacked the Cony in three or four waves from different sectors. Maneuvering in a series of radical turns, the Cony opened fire with her main battery and automatic weapons on each group. At 1533 the crew of No. 5 gun reported a shell jammed in the gun, which had to be drenched down the bore and outside. The Cony shot down five planes during the attack—one by 5-inch gunfire, and four by 40- and 20-mm. One other was possibly shot down and three were damaged.

About six bombs fell within 100 yards of the Cony. Then at 1534 two bombs struck her main deck aft abreast No. 4 gun. One of the bombs hit the starboard main deck at frame 163, one foot inboard, and exploded on contact; the other hit and penetrated the port main deck at frame 157, eight feet inboard, angled through bulkhead 157 and the longitudinal bulkhead between compartments C-202-E and C-4-F and exploded in the

22

engine room was pumped out by 0800. At 1049 the Cony wiped a spring bearing and had to be taken in tow by the Apache. She reached Purvis Bay without further incident.

In the meantime the LST’s were being harassed on their retirement course by Japanese planes. At 2024, about 40 minutes after they began retiring, several flares and float lights were dropped near the ships. The Philip was escorting and the Saufley later joined. At 2257, without warning from any radar-equipped vessel, a plane dropped two bombs and a float light close to No. 399. The ship received several splinters of shrapnel along the port side, one of which penetrated the conning station, while another cut the forestay. The severe shaking given the vessel broke the amplifier tubes.

The remainder of the trip was uneventful save for the extraordinary work done by the three doctors embarked on LST 485. An operating room had been improvised in the troop quarters, and all the seriously wounded were taken aboard that ship. One doctor and two corpsmen were sent from LST 399 to LST 485, which had wounded aboard. During the 30 hours en route to Guadalcanal, the three medical officers and assisting corpsmen worked without sleep or rest, performing 15 major operations and giving 120 plasma and 50 dextrose injections. All except five of the wounded were saved.

THE CHOISEUL DIVERSION

As A diversion for the Treasury landings and for the Bougainville operation to come, a landing of the 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion, under command of Lt. Col. Victor H. Krulak, on Choiseul Island, was planned for midnight of D minus 5 day, which was the day of the landing on the Treasury Islands. The operation was to be carried out by part of the ships that participated in the Treasury landings. Reports indicated that many enemy evacuees from Kolombangara were moving to the western part of Choiseul for ultimate transfer to Bougainville and elsewhere. Their removal from Choiseul had begun on 20 October.

TransDiv 22 and TransDiv 12 completed unloading at Treasury Islands at 0800 on 27 October and began the return to Guadalcanal. Wounded were transferred to TransDiv 12, and TransDiv 22 exchanged damaged boats for good ones. TransDiv 22, Comdr. Robert H. Wilkinson in the Kilty, with the Ward, Crosby, and McKean, left the convoy en route to Guadalcanal and set course for Juno River, Vella Lavella Island, via

23

Gizo Strait. The Conway accompanied the high speed troop ships. This force lay to off Juno River at 1830. So smooth was the planning that a large number of loaded boats were off the beach and ready to come alongside as soon as the APD’s stopped. The 800 men of the 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion, acting as infantry, were embarked expeditiously.

TransDiv 22, in column, fell in astern of the Conway as guide and proceeded across the Slot was uneventful. When the shore was 12,000 yards ahead on bearing 000o T speed was reduced to 10 knots and course adjusted to head westward of the Zinoa Islands. At 2310 an explosion was heard that was believed to be a bomb dropped on the port quarter of the rear APD. At 2314 a plane was heard overhead, but was not sighted or revealed by radar. No further attack was made at this time.

At 2322 all engines of the APD’s were stopped when the ships were 2,400 yards offshore at Voza on the southwest coast of Choiseul. After proceeding farther toward the shore, the Conway retired and took patrol station about 3,000 yards to the seaward of TransDiv 22. At about 2352 a boat with a scouting party left the APD’s, and at 0019 the first wave of boats followed.

A night fighter was assigned to the force, but remained at a high altitude. At 0145 a Japanese twin-float observation seaplane of the Jake type crossed over the Conway at an altitude of 200 feet and dropped two bombs which exploded some 200 yards off the port quarter. The plane did not renew the attack and our destroyers did not take it under fire. At 0209 the landing was completed and the boats hoisted in. The return trip was without incident.

The Marines were unopposed in their landing, but were discovered shortly thereafter. On the 29th they raided a barge group at Vagara, from which the enemy fled, leaving the Marines to destroy the supplies and barges. At 1800 the same day the Marines met a strong force between Vagara and Voza. In succeeding days they continued patrol and raiding activities along a 25-mile line, destroying enemy installations, barges, and supplies. Their swift and vigorous activity surprised the enemy and created the impression that a larger force was at work. Its mission completed, the battalion was withdrawn in LCI’s at 0150 on 4 November. Our losses during the entire operation were nine killed, two missing, and fifteen wounded, one of whom was captured. Known enemy casualties were 143 killed. In addition, the battalion disrupted

24

the withdrawal of Kolombangara refugees along the coast of Choiseul and captured valuable intelligence material. It is believed that our strategy worked well, for by 2 November the enemy had begun to gather strong detachments to oppose the Marines. Their attention was thus to some extent diverted from our primary objective, Bougainville.

BUKA-BONIS AND SHORTLAND BOMBARDMENTS

The landing operations at Empress Augusta Bay were coordinated with series of surface bombardments and air strikes designed to neutralize enemy airfields to the north and south of the beachhead. These operations opened shortly after midnight with a surface bombardment of Buka and Bonis, followed by an air strike at dawn from carrier-based planes. Also at dawn the task force that had bombarded Buka and Bonis earlier was to bombard enemy bases in the Shortland Islands south of Bougainville. H-hour at Torokina Point was set for 0715, about an hour after sunrise. A second air strike on Buka and Bonis was scheduled to occur about two hours after the assault wave reached the shore at Empress Augusta Bay. These events occurred as follows:

0021 Surface bombardment of Buka and Bonis.

0624 First air strike on Buka and Bonis.

0631 Surface bombardment of Shortland Islands.

0726 First assault wave reaches beach at Torokina Point.

0930 Second air strike on Buka and Bonis.

Buka-Bonis

Admiral Halsey’s plan called for a surface bombardment of Buka and Bonis airfields shortly after midnight on D-day. These two airfields, lying on opposite sides of Buka Passage at the northern tip of Bougainville Island, endangered our landing forces at Empress Augusta Bay and had to be rendered inoperative. This was to be followed by a shelling of the Shortland area at 0600 on D-day.

These missions were assigned to a task force under the command of Rear Admiral Aaron S. Merrill, who was also ordered to cover the operations at Empress Augusta Bay. Task Force Merrill was organized as follows, ships listed in normal order, van to rear:

DesDiv 45, Capt. Arleigh A. Burke, ComDesRon 23:

Charles F. Ausburne (F), Comdr. Luther K. Reynolds

Dyson, Comdr. Roy A. Gano.

Stanly, Comdr. Robert W. Cavenagh.

Claxton, Comdr. Herald F. Stout

25

CruDiv 12, Rear Admiral Merrill, ComTaskFor:

Montpelier (FF), Capt. Robert G. Tobin.

Cleveland, Capt. Andrew G. Shepard.

Columbia, Capt. Frank E. Beatty.

Denver, Capt. Robert P. Briscoe.

DesDiv 46, Comdr. Bernard L. Austin:

Spence (F) Comdr. Henry J. Armstrong, Jr.

Thatcher, Comdr. Leland R. Lampman.

Converse, Comdr. Dewitt C.E. Hamberger.

Foote, Comdr. Alston Ramsay.

Admiral Merrill and his staff spent the day before their departure at Admiral Halsey’s headquarters, studying mosaics made from reconnaissance photographs, collecting grid overlays to be used during the bombardments, and discussing with photographic interpreters the latest air intelligence of target locations in the Buka and Shortland areas. Information thus acquired was pronounced “most gratifying-not only from a gunnery perspective but from the point of view of safe navigation as well.” Navigational hazards in the Buka area were formidable, since it was known that our charts contained many discrepancies, and our information concerning location of reefs and shoals was scanty.

Task Force Merrill left Port Purvis at 0230 on 31 October for the run of 537 miles to the north end of Bougainville. The course lay south of the Russell Islands and the New Georgia Group and west of the Treasury Islands, striking due north from a point in latitude 06o 39’ S., longitude 154o 25’ E.—a track that would pass well clear of the uncharted reefs on the west coast of Bougainville Island.

In this deep penetration into enemy waters, it was hoped that surprise could be achieved and that enemy planes could be caught on the fields during the bombardment. Strict radio silence, including TBS, was ordered, and a night fighter was assigned to cover the task force and prevent enemy snoopers from reporting our movements. The Columbia was fighter director ship. Little was expected of the night fighter, however, when the night proved to be dark and overcast.

At 1854, while on course 310o, speed 29 knots, the task force picked up a bogey bearing 337o, distance 24 miles. This plane closed to within five miles at 1996, then disappeared from the screen at 50 miles on bearing 355o , the approximate course to Buka. Admiral Merrill considered it reasonable to assume that his high-speed wake had been sighted and that the snooper was returning to report in person. In addition, a radio report

26

was intercepted which indicated that the enemy had sighted our force and suspected that Buka was our objective. The time of the report, curiously, would indicate that its origin was Treasury Island and not a reconnaissance plane. During the next four hours bogies were on the screen constantly, but none of them showed any evidence of having sighted the task force. Beginning at 2329. Definite indications of enemy radar transmissions from the direction of Buka were received.

At 2336 ½ the task force changed course to 090o and headed directly for the beach to the north of Buka, having slowed to 20 knots 12 minutes previously. Convinced that Buka had been alerted by this time, CTF broke radio silence to say: “Confident we are expected, be on the alert for traps.” DesDiv 45, less Stanly, led the bombardment formation 7,000 yards in the van, and DesDiv 46 split, the first section 3,000 yards ahead of the cruisers, the second section 1,500 yards astern. The Stanly cruiser on a northwest line of bearing. She was to keep between the formation intercepting enemy forces would come. The Stanly was to rejoin astern when the final retirement course of the formation was taken.

Enemy submarines had been reported concentrating in the northern Solomons. As an additional precaution one of our submarines had been stationed south of Rabaul to warn of the sortie of enemy units. Also radar-equipped Liberators were ranging the area northwest of Buka to give warning of danger from that direction. Two Liberators remained on ground alert at Munda. Two Black Cats, with a spotter from CruDiv 12 inch each, reported on station over the targets in due time.

The cruisers were to cover assigned target areas with both 5-inch and 6-inch batteries, their offside 5-inch batteries to be alert to take under fire any targets, air or surface, encountered to seaward. The leading cruiser, the Montpelier, was assigned the Bougainville shore line of Buka Strait, and the Buka strip and supply area to the west of the field. The Cleveland was assigned Buka field with its revetments, as well as the supply and personnel area to the south and east of the field; the Columbia. Buka field with revetments, and the supply and personnel area to the west and northwest of the field; and the Denver, the headquarters, supply and personnel area to the north and northeast of the field for her 6-inch battery, and for her 5-inch battery, Buka field and revetment areas on each side of the field. Destroyers were to open fire at discretion after the

27

cruisers, unless moving targets threatened the formation or shore batteries opened fire, whereupon destroyers were to begin firing in advance of the cruisers. The leading destroyer was not to fire except against specific shore batteries and surface or air units threatening our forces. This ship’s primary function was a careful visual and radar search for early detection of moving surface units and a lookout and sound search for navigational dangers in the track of the task force. Other destroyers, except those in the rear, were to be assigned targets upon receipt of late intelligence reports. Rear destroyers were to fire only at specific shore batteries and surface or air targets, and were to maintain careful radar and visual search for early detection of moving surface units threatening our forces. Each cruiser was allotted 750 rounds of 6-inch 47 caliber H.C., of which the first 200 were to be fired with flashless and the remainder with smokeless powder; and 600 rounds of 5-inch 38 antiaircraft common, to be fired in the same manner.

At 2348 the Charles F. Ausburne came to 160o T., the firing course, which roughly paralleled the coast line and the outlying islands. An instant late a flashing white light was reported on the starboard bow. There were two friendly planes on the screen, assumed to be our spotters, and a bogey 12 miles to the southwest. CTF directed the force to take all bogies in range under fire once the bombardment started.

At 0021 the signal was executed to “commence firing,” and the cruisers opened fire, obtained their spots promptly, and began pumping projectiles over the hills on their targets. Shore batteries replied and were immediately taken under fire by the destroyers. A few rounds from the Ausburne silenced one battery in short order before it scored any hits. Other shore batteries continued persistently, despite the fire from our destroyers.

At 0027 the van destroyer Ausburne turned to the retiring course 220o T. Shortly thereafter reports were received indicating small surface targets, presumably enemy PT’s, approaching at high speed from the port quarter, and CTF ordered them taken under fire. Fire was opened immediately, and at 0030 ½ the Cleveland reported that the PT’s had turned away, probably after launching torpedoes. Ships were instructed to maneuver independently to avoid torpedoes. Ships in the rear of the formation continued firing their 40-mm. batteries.

The bombardment continued, with gunfire from the six-mile column described by one spectator as “impressive.” Most encouraging spots were

28

continually coming in from the plane spotters, The navigational fix used in firing was apparently excellent, as initial salvos “in all cases” fell where they intended to fall, and, as Admiral Merrill reported, the gunners had “no greater problem than ‘turning the crank.’” Fires which grew rapidly in intensity were started at both Buka and Bonis, until the area for miles around was lighted up and the hills in the foreground were silhouetted against the fires beyond.

About 0037 two enemy planes approached from the starboard beam of the formation and dropped four white flares which floated in midair and silhouetted the ships from the beach. Up to this point fire from the shore batteries had been spasmodic and inaccurate, reported only as “gun flashes from the beach.” As soon as the flares were dropped, however, splashes could be seen and shells heard overhead. One shell exploded abreast the flag office aboard the Montpelier, wetting down the exposed gun crews and wrecking the Admiral’s typewriter, but causing no further damage. These batteries were taken under fire, while ships astern were firing at planes making runs at the formation. The Cleveland reported at 0039 that she was firing at a periscope on her starboard bow, though with no apparent results.

According to plan, as each ship in the column came up to the water in which the Ausburne had turned, she turned to retirement course 220o T. and ceased firing. By 0038 the last ship had completed firing and turned away. Speed was increased to 28 knots and retirement begun.

Shortly after the bombardment began, the Stanly, at that time about ten miles to the northwest of the bombardment formation on a course approximately parallel to that of the formation, picked up a large pip on her radar approaching from the west toward the bombardment formation. Knowing that there were no friendly surface ships in this area, the Stanly opened fire, full radar control. The target ship was making speeds between 24 and 28 knots at a distance of between 16,000 and 18,000 yards. The target could never be clearly seen but shortly after the Stanly opened fire a very heavy black smoke seemed to envelop the ship and so continued as long as she was in sight. Radar indicated that shells were coming close to the target, but no definite hits could be spotted. Nor did the Stanly observe any hits as the result of the half salvo of torpedoes she fired. The target then turned to the east and ran away, still smoking badly. It was believed that the target was a “small destroyer,” and that she was damaged. Instead of pursuing, the Stanly set course to rejoin the formation, which was then retiring at high speed.

29

At 0050, 12 minutes after retirement was started, a number of float lights were dropped ahead of the formation, which promptly changed course to 280o by station units and increased speed to 30 knots. Fifteen minutes later cruisers and destroyers opened fire on bogies to starboard, which quickly retired.

The Stanly, back on the starboard quarter of the formation, after a lively exchange with shore batteries on her way to rejoin, reported a surface target at 0128 bearing 330o , distance six miles, and was ordered to open fire. She fired on targets which she took for PT’s closing at high speed, and believed she scored hits with her 5-inch battery. At any rate, the targets quickly retired.