Miller, Kelly. Kelly Miller's History of the World War for Human Rights: Being an Intensely Human and Brilliant Account of the World War and Why and for What Purpose America and the Allies are Fighting and the Important Part Taken by the Negro, Including the Horrors and Wonders of Modern Warfare, the New and Strange Devices, etc... Washington, DC, and Chicago, IL: Austin Jenkins Co., 1919.

The Navy Department Library

The Negro in the Navy

Pages 555-599 from Kelly Miller's History of the World War for Human Rights...

Achievements of the Negro in the American Navy - Guarding the Trans-Atlantic Route to France - Battling the Submarine Peril - The Best Sailors in Any Navy in the World - Making a Navy in Three Months from Negro Stevedores and Laborers - Wonderful Accomplishments of Our Negro Yeomen and Yeowomen.

Stranger than fiction, the story of the organization, development and expansion of the United States Navy from a mere atom, as it were, to the present time, when her electrically propelled men-of-war, equipped with the most luxurious compartments and modern mechanism for despatch and communication as well as her great merchant marine, floating the emblem of freedom and democracy in every civilized port of the world, is one of the most fascinating pages in the history of human achievement.

And, as it were, the very culmination of wonder and admiration, the chain of events reciting the deeds of valor and unselfish devotion to duty upon the part of her black sons, constitutes an illustrious record easily marking its participants as conspicuous representatives of a people, who have won their tardily conceded recognition in every phase of American public life.

The services of the Negro in the American Navy very properly begin with the stirring and thrilling events of the American Revolution, which terminated in the independence of the colonies and the establishment of the United States.

The Negro In The Revolutionary War.

The Negro in the Navy was then and has been ever since no less devoted to duty and as fearless of death as Crispus Attucks, when he fell on Boston Commons, the first martyr of American independence.

In speaking of colored seamen, who showed great heroism, Nathaniel Shaler, commander of the private armed schooner General Thompson, said of an engagement between his vessel and a British frigate: "The name of one of my poor fellows, who was killed, ought to be registered in the book of fame, and remembered with reverence as long as bravery is considered a virtue. He was a black man by the name of John Johnson. A twenty-four pound shot struck him in his hip, and took away all the lower part of his body. In this state, the poor brave fellow lay on the deck, and several times exclaimed to his shipmates, 'Fire away, my boy! No haul color down!' Another black by the name of John Davis was wounded in much the same way. He fell near me, and several times requested to be thrown overboard, saying he was only in the way of others. When America can boast of such tars she has little fear from the tyrants of the ocean."

British gold and promises of personal freedom served as futile incentives among the Negroes of the American Navy; for them, the proud consciousness of duty well done served as a constant monitor and nerved their strong black arms when thundering shot and shell menaced the future of the country; and, although African slavery was still a recognized legal institution and constituted the basic fabric of the great food productive industry of the nation, it was the Negro's trusted devotion to duty which ever guided him in the nation's darkest hours of peril and menace.

Negroes In The War Of 1812.

In the second period, the War of 1812, a second fight with Great Britain, again made it necessary to call upon the Negro for his assistance. Whether with Perry on Lake Erie, Commodore MacDonough, Lawrence or Chauncey, the black man played his heroic and sacrificing role, struggling and dying that American arms and valor, the security of American lives and property, would suffer no destruction at the hands of the enemy. The fine words of Commodore Chauncey, commending their dauntless intrepidity and unswerving obedience and loyalty to the rigorous demands of duty, should be read and carefully studied by all men, friendly to human excellence and courage.

Commodore Chauncey's Tribute.

The following is a statement of Commodore Perry, expressing dissatisfaction at the troops sent him on Lake Erie: "I have this moment received by express the enclosed letter of General Harrison, If I had officers and men, - and I have no doubt that you will send them, - I could fight the enemy and proceed up the lake; but, having no one to command the Majestic and only one commissioned officer and two acting lieutenants, whatever my wishes may be, getting out is out of the question. The men that came by Mr. Champlin are a motley set, - blacks, soldiers, and boys. I can not think that you saw them after they were selected. I am, however, pleased to see anything in shape of a man."

The following is the reply from Commodore Chauncey to Commodore Perry in answer to the above letter: "Sir, I have been duly honored with your letters of the 23d and 26th ultimo and notice your anxiety for men and officers, I am equally anxious to furnish you; and no time shall be lost in sending officers and men to you as soon as the public service will allow me to send them from this lake. I regret that you are not pleased with the men sent you by Messrs. Champlin and Forest; for, to my knowledge, a part of them are not surpassed by any seamen we have in the fleet; and I have yet to learn that the color of skin, or the cut and trimmings of the coat, can affect a man's qualifications and usefulness.

"I have nearly fifty blacks on board this ship, and many of them are among my best men, and I presume that you will find them as good and useful as any on board your vessel; at least if you can judge by comparison; for those which we have on board this ship are attentive and obedient, and, as far as I can judge, are excellent seamen. At any rate, the men sent to Lake Erie have been selected with the view of sending a proportion of petty officers and seamen and I presume upon examination, it will be found that they are equal to those upon this lake."

The Colored Man In The Mexican War.

In the Mexican War (1845-1848) we find him, in his humble positions of service and usefulness, a positive factor in the final success and triumph of American ideals. No insidious treacheries, no dark plots of poison, arson and unfaithfulness characterized his conduct, and, in the final and complete blockade of the Mexican ports, his contribution of faithful and loyal service made effective the terms by which Generals Scott and Taylor taught the ever-observed lesson of American dominance upon the Western Hemisphere and thereby preserved the Monroe Doctrine.

In The Days Of The Civil War.

In the Civil War - when the violence of domestic strife menaced the continuance of the National Union; when the preservation of slavery constituted the subject of angry and stormy debate in every section of the country, it was in the Navy, no less than in the Army, that the Negro evinced that dauntless fidelity to duty which aided in stabilizing the discipline of the field forces, thereby effectively contributing to the success not alone of forcing the Mississippi, and intersecting the Confederacy, but also in hermetically sealing all Southern ports and reducing to imperceptible insignificance the possibility of foreign trade with the South, - a factor which made it doubly sure that Northern arms would ultimately triumph and the Union be saved. It was a colored man, Robert Small, who single handed, stole the Union cruiser Panther 'from Charleston harbor, foiled the Confederate fleet, and navigated her safely to a Union port In all the annals of courage and dazzling gallantry, this incident has been recited; and it constitutes a commendable example, with many others, however, of devotion to duty and undying love for freedom. Mr. Small became a successful business man, and was one of the few Negroes who served in the Congress of the United States.

The Negro In The Spanish War.

The Spanish-American War (1898-1900) also Has its roll of honorable dead and surviving heroes - it was a Negro who fired the first shot at Manila Bay, from the cruiser Olympia, flag ship of the late Admiral Dewey, commanding the American forces on the Asiatic station. He was John Christopher Jordan, Chief gunner's mate (retired) U.S.N. His career is a fair example of the Negro's ability. He was first enlisted in the United States Navy on June 17, 1877, as an apprentice of the third class, the very lowest rating in which he could have entered. He advanced, despite opposition, through the different grades in direct competition with his white shipmates to the grade of chief gunner's mate, the highest rating that could be reached in the enlisted status.

It was not because of his lacK of desire for further advancement that he did not go higher, nor was it due to his not being qualified, for it was conceded by all officers under whom he served that he was thoroughly competent and highly qualified for advancement. He was finally recommended by his superior officer for the position of warrant gunner, and the papers passed up for final approval by the Commander-in-Chief of the fleet, before being sent to the Secretary of the Navy. There he encountered the Negro's most formidable foe - prejudice. That official very unceremoniously forwarded the papers to the Navy Department with the following endorsement: "Respectfully forwarded to the Secretary of the Navy - disapproved. The explanation of disapproval will be found in the applicant's descriptive list."

However, this slur did not deter Jordan in his determination to go higher, for at the battle of Manila he was a gunner's mate of the first class, and his record was so conspicuous that it could not go unnoticed by the officials in Washington.

Final Recognition.

The following letter was then addressed to Jordan's commanding officer by the Bureau of Navigation: The Bureau notes that John C. Jordan, gunner's mate first class, has served as such with a creditable service since August 6, 1899. The Chief of Bureau directs me to request an expression of opinion from the commanding officer as to whether Jordan possesses that superior intelligence, force of character and ability to command, necessary for a chief petty officer and particularly as to whether he is in all respects qualified for the position of chief gunner's mate of a first-class modern battleship."

The reply to this letter was to the effect that Jordan was in all respects qualified, and by order of the Secretary of the Navy, he was advanced to the grade of chief petty officer, filling this position with efficiency to the service and with credit to his race, until December 1, 1916, at which time he was retired, after serving thirty years in the Navy of the United States. The following letter was addressed to him by the Secretary of the Navy upon this occasion:

"The Department desires to congratulate you upon the completion of thirty years' service in the Navy. The fact that you started as an apprentice and now retire as a chief petty officer, your several honorable discharges and good conduct medals, show that you were a valuable man in the upbuilding of the Navy, and while the Department is glad to know that you will now enjoy the benefits of the retirement law, yet it regrets very much to see you retire from active life in the Navy. The Department hopes that you will always take a lively interest in naval affairs, and wishes you many years of good health and usefulness."

Other Instances.

Another very interesting character of the Navy during this period was Mr. C. D. Tippett of Washington D. C, who enlisted in the Navy in 1875, and who served honorably and faithfully, until recently, when he was retired for honorable service. Mr. Tippett enjoys the distinction of having crossed the equator on two different occasions, and holds a certificate from Neptune, a relic highly treasured by all naval men fortunate enough to hold one.

It has been the object of the preceding paragraphs to briefly recite some few instances of the Negro's activity in the American Navy from its beginning up to the present struggle. Space and time will not permit a more detailed and accurate exposition of the many other cases equally as interesting, instructive, and illustrative of the superb discipline and devotion to duty of this race whenever and wherever called upon to serve.

The Negro Seaman In The World War.

The extent of the Negro's work in the Army and the record of its brilliant achievements may in some degree obscure the service rendered our country and its Allies by the Negro in the Navy, but the Negro was represented in this branch of the military service almost in the same proportion, and, just as with Perry on Lake Erie. Farragut on the Mississippi, Dewey at Manila Bay, Hobson at Santiago, and Peary at the North Pole, he rendered efficient heroic and honorable service during the World War. It must be remembered that our ships were a part of the great war forces which kept open the highways of the deep and made possible the final triumph of the Allied armies, for, had the command of the ocean slipped from our hands those armies would have languished and been beaten back for lack of support in men and material. Had the sceptre of the seas passed to our foes, our own black boys would never have inscribed on their banner the imperishable name of Chateau-Thierry, The Argonne, and Hill 304. The one essential and indisputable element of victory was the supremacy of the Allied fleet.

Negroes In The Grand Fleet.

The Negro's part in the organization of the Grand Fleet is far from being inconsiderable, his services were utilized in the complement of every vessel and shore station and at this time as in the past, black blood was among the very first to be gloriously shed in the American Navy, that free government should live imperishably among the sons of men.

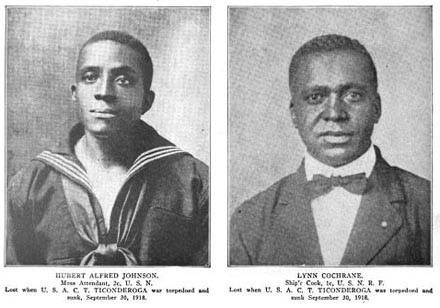

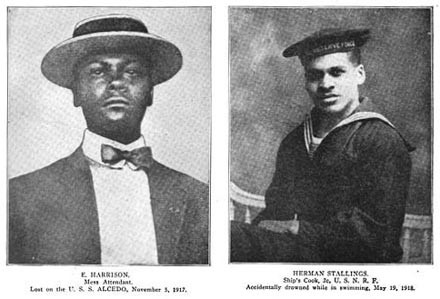

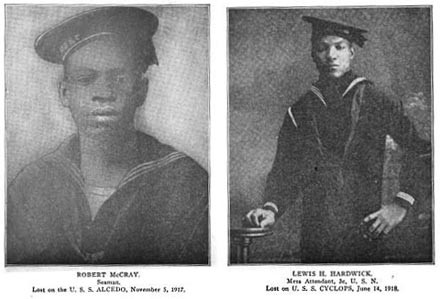

On November 4,1917, the U.S.S. Alcedo proceeded to sea from Quiberon Bay on escort duty to take convoy through the war zone; she had as members of her crew two young Negroes, just in the prime of life and patriotic to the core. It was the crew of this vessel that was first called upon to make the supreme sacrifice. Robert McCray and Earnest Harrison were their names, and the following report fully indicates the manner in which they gave their lives in order that democracy might not perish from the earth: "At or about 1:45 A.M., November 5th, while sleeping in emergency cabin, immediately under upper bridge, I was awakened by a commotion and immediately received a report from some man unknown, 'Submarine, Captain.'

"I jumped out of bed and went to the upper bridge, and the officer of the deck, Lieutenant Paul, stated he had sounded 'General quarters,' had seen submarine on surface about three hundred yards on port bow, and submarine had fired a torpedo, which was approaching. I took station on port wing of upper bridge and saw torpedo approaching about two hundred yards distant. Lieutenant Paul had put the rudder full right before I arrived on bridge, hoping to avoid the torpedo. The ship answered slowly to her helm however, and before any other action could be taken the torpedo I saw struck the ship's side immediately under the port forward chain plates, the detonation occurring instantly.

"I was thrown down and for a few seconds dazed by falling debris and water. Upon regaining my feet I sounded the submarine alarm on the siren, to call all hands if they had not heard the general alarm gong, and to direct their attention of the convoy and other escorting vessels. Called to the forward gun's crew to see if at stations, but by this time realized that the forecastle was practically awash. The foremast had fallen, carrying away radio aerial. I called out to abandon ship.

The Sinking Ship.

"I then left the upper bridge and went into the chart house to obtain ship's position from the chart, but, as there was no light, could not see. I then went out of the chart house and met the navigator, Lieutenant Leonard, and asked him if he had sent any radio; he replied 'No.' I then directed him and accompanied him to the main deck and told him to take charge of cutting away forward dories and life rafts. I then proceeded along starboard gangway and found a man lying face down in gangway. I stooped and rolled him over and spoke to him, but received no reply and was unable to learn his identity, owing to the darkness. It is my opinion that this man was dead. I then continued to the after end of ship, took station on after gun platform.

"I then realized that the ship was filling rapidly and her bulwarks amidships were level with the water. I directed the after dories and life rafts to be cut away and thrown overboard and ordered the men in the immediate vicinity to jump over the side, intending to follow them. Before I could jump, however, the ship listed heavily to port, plunging by the head and sunk, carrying me down with the suction.

Struggle In The Water.

"I experienced no difficulty, however, in getting clear and when I came to the surface I swam a few yards to a life raft, to which were clinging three men. We climbed on board this raft and upon looking around observed Doyle, chief boatswain's mate, and one other man in the whale boat. We paddled to the whale boat and embarked from the life raft. The whale boat was about half full of water and we immediately started bailing and then to rescue men from the wreckage, and quickly filled the whale boat to more than its maximum capacity, so that no others could be taken aboard. We then picked up two overturned dories which were nested together, separated them and righted them, only to find that their sterns had been broken.

"We then located another nest of dories, which were found to be seaworthy. Transferred some men from the whale boat into these dories and proceeded to pick up other men from wreckage. During this time cries were heard from two men in the water some distance away who were holding on to wreckage and calling for assistance. It is believed that these men were Earnest M. Harrison and John Winne, Jr. As soon as the dories were available, we proceeded to where they were last seen but could find no trace of them.

"About this time, which was probably an hour after the ship sank, a German submarine approached the scene of torpedoing and lay to, near some of the dories and life rafts. She was in the light condition, and from my observation of her I am of the opinion that she was of the U-27-31 type. This has been confirmed by having a number of men and officers check the silhouette book. The submarine was probably one hundred yards distant from my whale boat, and I heard no remarks from anyone on the submarine, although I observed three persons standing on top of conning tower. After laying on surface about half an hour the submarine steered off and submerged. I then proceeded with the whale boat and two dories searching through the wreckage to make sure that no survivors were left in the water. No other people being seen, at 4:30 A.M. we steered away from the scene of disaster. The Alcedo was sunk, near as I can estimate, seventy-five miles west true of north end of Belle Ile. The torpedo struck ship at 1:46 by the officer of the deck's watch and the same watch stopped at 1:54 A.M. November 5th, this showing that the ship remained afloat eight minutes. The flare of Penmark Light was visible, and I headed for it and ascertained the course by Polaris to be approximately northeast. We rowed until 1:15, when Penmark Lighthouse was sighted. Continued rowing until 5:15 P.M., when Penmark Lighthouse was distant about two and one-half miles. We were then picked up by French torpedo boat number 257, and upon going on board I requested the commanding officer to radio immediately to Brest reporting the fact of torpedoing and that three officers and forty men were proceeding to Brest. The French gave all assistance possible for the comfort of the survivors. We arrived at Brest about 11 P.M. Those requiring medical attention were sent to the hospital and the others were sent off to the Panther to be quartered. Upon arrival at Brest I was informed that two other dories containing Lieut. H. E. Leonard, Lieut. H. A. Peterson, P. A. Aurgeon, Paul O. M. Andreae, and twenty-five men had landed at Pen March Point. This is my first intimation that these officers and men had been saved, as they had not been seen by any of my party at the scene of torpedoing."

Disappearance Of The Cyclops.

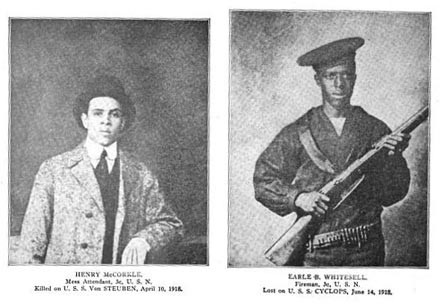

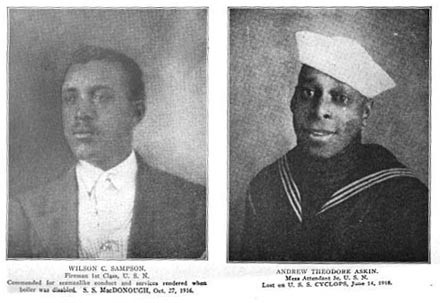

The next contribution of life on the part of the Negro in the American Navy was made when the U.S.S. war vessel Cyclops so mysteriously disappeared. Loaded with a cargo of manganese, with fifty-seven passengers, twenty officers, and a crew of two hundred and thirteen enlisted men (twenty-three of whom were Negroes). The vessel was due in port March 13, 1918. On March 4, the Cyclops reported at "Barbadoes, British West Indies, where she put in for bunker coal. Since her departure from that port there has not been the slightest trace of the vessel, and long continued and vigilant search of the entire region proved utterly futile, as not a vestige of wreckage has been discovered. No responsible explanation of the strange and mysterious disappearance of this vessel has ever been given by the officials of the Navy Department. It was known that one of her two engines was damaged, and that she was proceeding at reduced speed; but, even if the other engine had become disabled, it would not have had any effect on her ability to communicate by radio.

Many theories have been advanced, but none seems to account satisfactorily for the ship's complete vanishment. After months of search and waiting, the Cyclops was finally given up as lost and her crew officially declared dead. This vessel was under the command of a German-born officer, who, prior to his connection with the Navy Department, was an officer of the merchant marine. Many accusations were made reflecting upon his loyalty. Some even going as far as suggesting that he had intimidated the crew and delivered the vessel into the hands of the enemy; but, it is strange to note that none of these insinuations was directed to the loyal and ever true Negroes who formed a part of its crew and presumably went to their watery graves in order that German militarism might be crushed.

"What a strange episode if, indeed, these are the facts in this most unfortunate incident. In intelligent circles, it should and will mark the beginning of a period of racial justice and equity. When one's deeds and character will invariably constitute the exponent of one's appreciation.

The Negro True And Loyal.

Caucasian treachery in some of our national perils presented no charms for the Negro whose proven fidelity everywhere and on every occasion marks him the great American advocate in fact as well as in profession.

If these accusations should in the end prove true, which is highly possible, would it not have been wiser on the part of the directors of our naval policy, when the urgent pressure for man-power to officer the expanding Navy of the United States asserted itself, to have recognized the ability and merit of scores of black men, whose years of faithful and efficient service in the Navy of the United States and unquestioned fidelity to duty justly entitle them to the command of a vessel of this character, instead of utilizing the services of men of questioned loyalty and doubtful allegiance to command our naval vessels? For such an act of base and unpardonable treachery is unthinkable to a Negro. Rather would he most willingly have seen his last drop of rich loyal blood flow in torrents of effusion than to leave to his progeny such a record of shame and infamy.

The Jacob Jones.

Another incident in which the Negro displayed his constant willingness to die for the cause of America and its ideals was when the United States torpedo boat destroyer Jacob Jones was destroyed by a torpedo fired from a German submarine. This ship was one of six of an escorting group which was returning independently from Brest, France, to Queensland, Ireland. The following extract from the report of its commanding officer gives in brief detail the manner in which the majority of its crew met their death in an effort to uphold the principles of democracy. On this vessel, as well as all others that were lost, the Negro served, bled, and died, side by side with white men in a desperate struggle to subdue the German U-boat.

"I was in the chart house and heard some one cry out, 'Torpedo.' I jumped at once to the bridge and on the way up saw the torpedo about eight hundred yards from the ship approaching from about one point abaft the starboard beam headed for a point about amidships, making a perfectly straight surface run (alternately broaching and submerging to approximately four or five feet), at an estimated speed of at least forty knots. No periscope was sighted. When I reached the bridge, I found that the officer of the deck had already put the rudder hard left and rung up the emergency speed on the engine room telegraph. The ship had already begun to swing to the left. I personally rang up the emergency speed again and then turned to watch the torpedo. The executive officer left the chart house just ahead of me, saw the torpedo immediately on getting outside the door, and estimates that the torpedo when he sighted it was one thousand yards away, approaching from one point, or slightly less, abaft the beam and making exceedingly high speed.

"After seeing the torpedo and realizing the straight run, line of approach, and high speed it was making, I was convinced that it was impossible to manouver to avoid it. The officer of the deck took prompt measures in maneuvering to avoid the torpedo. The torpedo broached and jumped clear of the water at a short distance from the ship, submerged about fifty or sixty feet from the ship and struck approximately three feet below the water-line in the fuel oil tank between the auxiliary room and the after crew space.

The Slowly Sinking Ship.

"The ship settled aft immediately after being torpedoed to a point at which the deck just forward of the after deck house was awash, and then, more gradually, until the deck-abreast the engine room hatch was awash. A man on watch in the engine room attempted to close the water-tight door between the auxiliary room and the engine room, but was unable to do so against the pressure of water from the auxiliary room. The deck over the forward part of the after crew space and over the fuel oil tanks just forward of it was blown clear for a space athwartships of about twenty feet from starboard to port, and the auxiliary room was wrecked. The starboard after torpedo tube was blown into the air. No fuel oil ignited and apparently no ammunition exploded.

"The depth charges in the chutes aft were set on ready and exploded after the stern sank. It was impossible to get to them to set on safe as they were under the water.

"As soon as the torpedo struck, it was attempted to send out an S. O. S. message by radio, but the mainmast was carried away and antennae falling and all electric power had failed. I then tried to have the gun sight lighting batteries connected up in an effort to send out a low power message with them, but it was at once evident that this would not be practicable before the ship sank. There was no other vessel in sight, and it was therefore impossible to get through a distress signal of any kind. Immediately after the ship was torpedoed every effort was made to get rafts and boats launched. Also, the circular life belts from the bridge and several splinter mats from the outside of the bridge were cut adrift and afterwards proved very useful in holding men up until they could be got to the raft.

Struggling Men In The Water.

"The ship sank about 4:29 P.M. (about eight minutes after being torpedoed). As I saw her settling rapidly, I ran along the deck and ordered everybody I saw to jump overboard. At this time, most of those not killed by the explosion had got clear of the ship and were on rafts or wreckage. Some, however, were swimming and a few appeared to be about a ship's length astern of the ship, at some distance from the rafts, probably having jumped overboard very soon after the ship was torpedoed.

"Before the ship sank, two shots were fired from No. 4 gun with the hope of attracting the attention of some nearby ship. As the ship began sinking I jumped overboard. The ship sank stern first and twisted slowly through nearly one hundred and eighty degrees as she swung upright. From this nearly vertical position, bow in the air, to about the forward point, she went straight down. Before the ship reached the vertical position the depth charges exploded, and I believe them to have caused the death of a number of men. They also partially paralyzed, stunned, or dazed a number of others, some of whom are still disabled.

Safeguarding The Survivors.

"Immediate efforts were made to get all survivors on the rafts and then get the rafts and boats together. Three rafts were launched before the ship sank and one floated off when she sank. The motor dory, hull undamaged but engine out of commission, also floated off and the punt and wherry also floated clear. The punt was wrecked beyond usefulness and the wherry was damaged and leaking badly, but was of considerable use in getting men to the rafts. The whale boat was launched but capsized soon afterwards, having been damaged by the explosion of the depth charges. The motor sailor did not float clear, but went down with the ship.

"About fifteen or twenty minutes after the ship sank, the submarine appeared on the surface about two or three miles to the westward of the raft, and gradually approached until about eight hundred or one thousand yards from the ship, where it stopped and was seen to pick up one unidentified man from the water. The submarine then submerged and was not seen again.

By Motor Dory To The Scilly Islands.

"I was picked up by the motor dory and at once began to make arrangements to reach the Scillys in that boat in order to get assistance to those on the rafts. All the survivors then in sight were collected and I gave orders to one of the officers to keep them together. The navigating officer had fixed the position a few minutes before the explosion and both he and I knew accurately the course to be steered. I kept one of the officers with me and four men who were in good condition to man the oars, the engine being out of commission. With the exception of some emergency rations and a half bucket of water, all provisions, including medical kit, were taken from the dory and left on the rafts. There was no apparatus of any kind which could be used for night signalling.

"After a very trying trip, during which it was necessary to steer by stars and by direction of the wind, the dory was picked up about 1 P.M. by a small patrol vessel about six miles south of St. Mary's. The commander informing me that the rest of the survivors had been picked up. I deeply regret to state that out of a total of several officers and one hundred and six enlisted men on board at the time of the torpedoing, two officers and sixty-four enlisted men were killed in the performance of duty. The behavior of the men under the most exceptional and trying conditions is worthy of praise, and the following cases are a sample of the spirit of the men under these conditions.

Instance Of Rare Self-Denial.

"One man removed parts of his clothing (when all realized that their lives depended upon keeping warm), to try to keep alive men who were more thinly clad than himself. Another man at the risk of almost certain death, remained in the motor sailor and endeavored to get it clear for floating from the ship. While he did not succeed in accomplishing this act (which would have undoubtedly saved twenty or thirty lives) stuck to his duty until the very last. He was drawn under the water with the boat, but later came to the surface and was rescued."

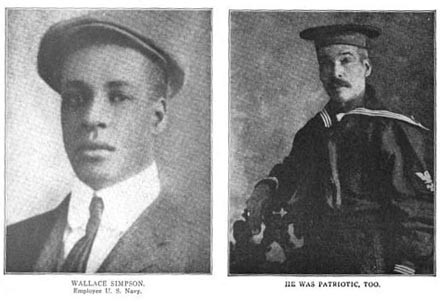

Wallace Simpson, a young Negro, was a petty officer aboard this vessel. Young Simpson was a graduate of the high school, Denver, Colorado, and at the call of his country, when but in the prime of his life, made the supreme sacrifice in order that the world might be made safe for democracy.

Negro Firemen And Coal Passers.

It seems that fate always throws the Negro in a line of service wherein he can by some method, peculiarly his own, have an opportunity to display his ability, loyalty and usefulness, in spite of prejudice and opposition. I particularly refer here to the positions of firemen and coal passers, because of the physical strength required for work of that kind. The Negro can serve better in the American Navy in this capacity than in any other, with the possible exception of the messman branch of service; but, nevertheless, in the former positions he has a decidedly better opportunity to bring into play originality and foresight, for the fire-room is the life of the ship and especially so when attacked.

When one of the vessels of our Navy had been hit with one torpedo from an enemy submarine and was about to be hit with a second, the commanding officer had the following statement to make: "I realized that the immediate problem was to escape a second torpedo. To do so, two things were necessary, to attack the enemy, and to make more speed than he could submerged. The depth charge crew jumped to their stations and immediately started dropping depth bombs. A barrage of depth charges was dropped, exploding at regular intervals far below the surface of the water. This work was beautifully done. The explosions must have shaken the enemy up, at any rate he never came to the surface again to get a look at us.

"The other factor in the problem was to make as much speed as possible, not only in order to escape an immediate attack, but also to prevent the submarine from tracking us and attacking us after nightfall.

"The men in the fire rooms knew that the safety of the ship and our lives depended on their bravery and steadfastness to duty. It is difficult to conceive a more trying ordeal to one's courage than was presented to every man in the fire room that escaped destruction. The profound shock of the explosion, followed by instant darkness, falling soot and particles, the knowledge that they were far below the water level, practically enclosed in a trap, the imminent danger of the ship sinking, the added threat of exploding boilers - all these dangers and more must have been apparent to every man below, and yet not one man wavered in standing by his post of duty.

Wonderful Devotion To Duty.

"No better example can possibly be given of the wonderful fact that with a brave and disciplined body of American men, white or black, all things are possible. However strong may be their momentary impulses for self-preservation in extreme danger, their controlling impulses are to stand by their stations and duty at all hazards.

"In at least two instances in this crisis below, men who were actually in the face of death did actually forget or ignored their impulse of self-preservation and endeavored to do what appeared to them to be their duty. One man was in one of the flooded fire rooms. He was thrown to the floor and instantly enveloped in flames from the burning gases driven from the furnaces, but instead of rushing to escape, he turned and endeavored to shut a water-tight door leading into a large bunker abaft the fire room. But the hydraulic lever that operated the door had been injured by the shock and failed to function. Three men at work at this bunker were drowned. If this man had succeeded in shutting the door, the lives of these men would have been saved as well as considerable buoyancy saved to the ship. The fact that he, though profoundly stunned by the shock and almost fatally burned by the furnace gases, should have had presence of mind and the courage to endeavor to shut the door is a great example of heroic devotion to duty as is possible for one to imagine. Immediately after attempting to close the door he was caught in the swirl of inrushing water and thrust up a ventilator leading to the upper deck.

Strange Effect Of The Explosions.

"The torpedo exploded on a bulkhead separating two fire rooms, the explosive effect being apparently equal in both fire rooms, yet, in one fire room not a man was saved, while in the other fire room two of the men escaped. The explosion blasted through the outer and inner skin of the ship and through an intervening coal bunker and bulkhead, hurling overboard seven hundred and fifty tons of coal. The two men saved were working the fires within thirty feet of the explosion and just below the level where the torpedo struck.

"It is difficult to see how it was possible for these men to have escaped the shower of debris, coal and water that must instantly have followed the explosion. However, the two men were not only saved but seemed to have retained full possession of their faculties. Both of them were knocked down and blown across the fire room. Their sensations were at first a shower of flying coal, followed by an overwhelming inrush of water that swirled them round and round and finally thrust them up against the gratings of the top of the fire rooms."

The Attack Upon The Torpedo Boat Cassin.

Another instance of self-sacrifice and unparalleled heroism is contained in the account of the attack upon the torpedo boat Cassin by a German submarine, while on patrol duty off the coast of Ireland. The following is the story briefly related in the official report of her commanding officer:

"When about twenty miles south of Minehead, at 1:30 P.M., a German submarine was sighted by the lookout aloft four or five miles away, about two points on the port bow. The submarine at this time was awash and was made out by officers of the watch and the quartermaster of the watch, but three minutes later submerged. The Cassin which was making fifteen knots continued on its course until near the position where the submarine had disappeared. When last seen the submarine was heading in a southeasterly direction, and when the destroyer reached the point of disappearance the course was changed, as it was thought the vessel would make a decided change of course after submerging. At this time the commanding officer, the executive officer, engineer officer, officer of the watch, and the junior watch officers were all on the bridge searching for the submarine.

The Attack.

"About 1:57 P.M., the commanding officer sighted a torpedo apparently shortly after it had been fired, running near the surface and in a direction that was estimated would make a hit either in the engine or fire room. When first seen the torpedo was between three or four hundred yards from the ship, and the wake could be followed on the other side for about four hundred yards. The torpedo was running at high speed, at least thirty-five knots. The Cassin was manoeuvering to dodge the torpedo, double emergency full speed ahead having been signalled from the engine room and the rudder put hard left as soon as the torpedo was sighted. It looked for the moment as though the torpedo would pass astern. When about fifteen or twenty feet away the torpedo porpoised, completely leaving the water and sheering to the left. Before again taking the water the torpedo hit the ship well aft on the port side about frame one hundred sixty-three and above the water line. Almost immediately after the explosion of the torpedo the depth charges, located on the stern and ready for firing, exploded. There were two distinct explosions in quick succession after the torpedo hit. "But one life was lost. Osman K. Ingram, gunner's mate, first class, was cleaning the muzzle of number 4 gun, target practice being just over when the attack occurred. With rare presence of mind, realizing that the torpedo was about to strike the part of the ship where the depth charges were stored and that the setting off of these explosions might sink the ship, Ingram, immediately seeing the danger, ran aft to strip these charges and throw them overboard. He was blown to pieces when the torpedo struck. Thus, Ingram sacrificed his life in the performance of a duty which he believed would save his ship and the lives of the officers and men on board."

Torpedoing The President Lincoln.

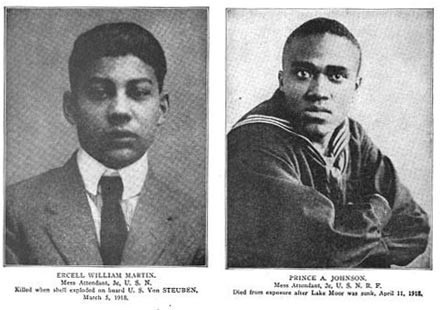

One of the most spectacular and thrilling incidents of our naval warfare in which more than a score of colored men bravely and heroically participated, was the attack and sinking of the U.S.S. President Lincoln, the commanding officer of which reports as follows:

"On May 31, 1918, the President Lincoln was returning to America from a voyage to France, and was in line formation with the U.S.S. Susquehanna, Antigone, and Ryndam, the latter being on the left flank of the formation and about eight hundred yards from the President Lincoln. The ships were about five hundred miles from the coast of France and had passed through what was considered to be the most dangerous part of the war zone. At about 9 A.M. a terrific explosion occurred on the port side of the ship about one hundred and twenty feet from the bow and immediately afterwards another explosion occurred on the port side of the ship about one hundred and twenty feet from the stern, these explosions being immediately identified as coming from torpedoes fired by a German submarine.

"It was found that the ship had been struck by three torpedoes, which were fired as one salvo from the submarine, two of the torpedoes striking practically together near the bow of the ship and the third striking near the stern. The wake of the torpedo had been sighted by the officers and lookouts on watch, but the torpedoes were so close to the ship as to make it impossible to avoid them; and it was also found that the submarine at the time of firing was only about eight hundred yards from the President Lincoln. There were at the time seven hundred and fifteen persons on board, some of these were sick and two men were totally paralyzed.

Coolness And Discipline.

"The alarm was immediately sounded and everyone went to his proper station which had been designated at previous drills. There was not the slightest confusion and the crew and passengers waited for and acted on orders from the commanding officer with a coolness which was truly inspiring. Inspections were made below decks and it was found that the ship was rapidly filling with water, both forward and aft, and that there was little likelihood that she would remain afloat. The boats were lowered and the life rafts were placed in the water and about fifteen minutes after the ship was struck all hands except guns' crews were ordered to abandon the ship.

"It had been previously planned that in order to avoid the losses which have occurred in such instances by filling the boats at the davits before lowering them, that only one officer and five men would get into the boats before lowering and that everyone else would get into the water and get on the life rafts and then be picked up by the boats, this being entirely feasible, as everyone was provided with an efficient life-saving jacket. One exception was made to the plan, however, in that one boat was filled with the sick before being lowered and it was in this boat that the paralyzed men were saved without difficulty.

The Ship Abandoned.

"The guns' crews were held at their stations hoping for an opportunity to fire on the submarine should it appear before the ship sank, and orders were given to the guns' crews to begin firing, hoping that this might prevent further attack. All the ship's company except the guns' crews and the necessary officers were at that time in the boats and on the rafts near the ship, and when the guns' crews began firing, the people in the boats set up a cheer to show that they were not downhearted. The guns' crews only left their guns when ordered by the commanding officer just before the ship sank. The guns in the bow kept up firing until after the water was entirely over the main deck of the after half of the ship.

"The state of discipline which existed and the coolness of the men is well illustrated by what occurred when the boats were being lowered and were about half way from their davits to the water. At this particular time, there appeared some possibility of the ship not sinking immediately, and the commanding officer gave the order to stop lowering the boats. This order could not be understood, however, owing to the noise caused by escaping steam from the safety valves of the boilers which had been lifted to prevent explosion, but by motion of the hand from the commanding officer the crews stopped lowering the boats and held them in mid air for a few minutes until at a further motion of the hand the boats were dropped into the water.

Inspected By The Submarine.

"Immediately after the ship sank the boats pulled among the rafts and were loaded with men to their full capacity and the work of collecting the rafts and tying them together to prevent drifting apart and being lost was begun. While this work was under way and about half an hour after the ship sank, a large German submarine emerged and came among the boats and rafts, searching for the commanding officer and some of the senior officers whom they desired to take prisoners. The submarine commander was able to identify only one officer, Lieut. E. V. M. Isaacs, whom he took on board. The submarine remained in the vicinity of the boats for about two hours and returned again in the afternoon, hoping apparently for an opportunity of attacking some of the other ships which had been in company with the President Lincoln, but which had, in accordance with standard instructions, steamed as rapidly as possible from the scene of attack.

"By dark the boats and rafts had been collected and secured together, there being about five hundred men in the boats and about two hundred on the rafts. Lighted lanterns were hoisted in the boats and flare-up lights and signal lights were burned every few minutes, the necessary detail of men being made to carry out this work during the night. The boats had been provided with water and food, but none was used during the day, as the quantity was necessarily limited, and it might be a period of several days before a rescue could be effected.

The Rescue.

"The ship's wireless plant had been put out of commission by the force of the explosion, and although the ship's operator had sent the radio distress signal, yet it was known that the nearest destroyers were two hundred and fifty miles away, protecting another convoy, and it was possible that military necessity might prevent their being detached to come to our rescue. At about 11 P.M. a white light flashing in the blackness of the night, - it was very dark - was sighted, and very shortly it was found that the destroyer Warrington had arrived to our rescue and about an hour afterwards the destroyer Smith also arrived. The transfer of the men from the boats and rafts to the destroyers was effected as quickly as possible and the destroyers remained in the vicinity until after daylight the following morning, when a further search was made for survivors who might have drifted in a boat or on a raft, but none were found, and at about 6 A.M., the return trip to France was begun.

"Of the seven hundred and fifteen men present all told on board, it was found after the muster that three officers and twenty-three men were lost with the ship, and that one officer had been taken prisoner.

Conduct Of The Submarine Commander.

"Although the German submarine commander made no offers of assistance of any kind, yet otherwise his conduct for the ship's company in the boat was all that could be expected. We naturally had some apprehension as to whether or not he would open fire on the boats and rafts. I thought he might probably do this, as an attempt to make me and other officers disclose their identity. This possibility was evidently in the minds of the men of the crew also, because at one time I noticed some one on the submarine walk to the muzzle of one of the guns, apparently with the intention of preparing it for action. This was evidently observed by some of the men in my boat, and I heard the remark, 'Good night, here comes the fireworks.' The spirit which actuated remarks of this kind, under such circumstances, could be none other than that of cool courage and bravery."

Captured By Submarine, Naval Officer Escapes.

(Condensed from report by Lieutenant Edouard Victor M. Isaacs on his capture and escape from a German prison camp.)

"The President Lincoln went down about 9:30 in the morning, thirty minutes after being struck by three torpedoes. In obedience to orders I abandoned ship after seeing all hands aft safely off the vessel. The boats had pulled away, but I stepped on a raft floating alongside, the quarter deck being then awash. A few minutes later one of the boats picked me up. The submarine U-90, returned and the commanding officer, while searching for Captain Foote of the President Lincoln, took me out of the boat. I told him my captain had gone down with the ship, whereupon he steamed away, taking me prisoner to Germany. We passed to the north of the Shetlands into the North Sea, the Skaggerak, the Cattegat, and the Sound into the Baltic. Proceeding to Kiel, we passed down the canal through Heligoland Bight to Wilhelmshaven.

"On the way to the Shetlands, we fell in with two American destroyers, the Smith and the Warrington, who dropped twenty-two depth bombs on us. We were submerged to a depth of sixty meters and weathered the storm, although five bombs were very close and shook us up considerably. The information I had been able to collect was, I considered, of enough importance to warrant my trying to escape. Accordingly in Danish waters I attempted to jump from the deck of the submarine but was caught and ordered below.

Made A Prisoner Of War.

"The German Navy authorities took me from Wilhelmshaven to Karlsruhe, where I was turned over to the Army. Here I met officers of all the Allied armies, and with them I attempted several escapes, all of which were unsuccessful. After three weeks at Karlsruhe I was sent to the American and Russian officers' camp at Villinen. On the way I attempted to escape from the train by jumping out of the window. With the train making about forty miles an hour, I landed on the opposite railroad track and was so severely wounded by the fall that I could not get away from my guard. They followed me, firing continuously. When they recaptured me they struck me on the head and body with their guns until one broke his rifle. It snapped in two at the small of the stock as he struck me with the butt on the back of the head.

Placed In Solitary Confinement.

"I was given two weeks' solitary confinement for this attempt to escape, but continued trying, for I was determined to get my information back to the Navy. Finally, on the night of October 6th, assisted by several Army officers, I was able to effect an escape by short-circuiting all lighting circuits in the prison camps and cutting through barbed wire fences surrounding the camp. This had to be done in the face of a heavy rifle fire from the guards. But it was difficult for them to see in the darkness, so I escaped unscathed. In company with an American officer in the French Army, I made my way for seven days and nights over mountains to the Rhine, which to the south of Baden forms the boundary between Germany and Switzerland. After a four-hour crawl on hands and knees I was able to elude the sentries along the Rhine. Plunging in, I made for the Swiss shore. After being carried several miles down the stream, being frequently submerged by the rapid currents, I finally reached the opposite shore and gave myself up to the Swiss gendarmes, who turned me over to the American legation at Berne. From there I made my way to Paris and then London and finally Washington, where I arrived four weeks after my escape from Germany."

The accounts and incidents heretofore mentioned are but a few of the exceptionally meritorious cases, of the many, in which the devotion to duty and the unquestioned heroism characterized the conduct of the Negro under the galling fire of danger and death.

Can Not Specify The Work Of The Negro Seamen.

Primarily due to the difference in organization between the Army and Navy of the United States, it is well nigh impossible to point out and record with any degree of accuracy the signal and patriotic sacrifices of any great body of Negroes as a unit in the naval service. While in the Army, where segregation and discrimination of the rankest type force the Negro into distinct Negro units; the Navy, on the other hand, has its quota of black men on every vessel carrying the starry emblem of freedom on the high seas and in every shore station. The operations of the Navy of the United States during the World War has covered the widest scope in its history without a doubt. It carried the Negro in European waters from the Mediterranean to the White Sea. At Corfu, Gibraltar, along the French Bay of Biscay, in the English Channel, on the Irish coast, in the North Sea, at Murmansk and Archangel, he was ever present to experience whatever of hardships were necessary and to make whatever sacrifices demanded, that the proud and glorious record of the Navy of the United States should remain untarnished.

Work Of Colored Seamen.

He formed a part of the crew of nearly two thousand vessels that plied the briny deep, on submarines that feared not the under sea peril, and wherever a naval engagement was undertaken or the performance of a duty by a naval vessel, the Negro, as a part of the crew of that vessel, necessarily contributed to the successful prosecution of that duty; and, whatever credit or glory is achieved for American valor, it was made possible by the faithful execution of his duty, regardless of his character. For, on a battleship where the strictest system of co-ordination and cooperation among all who compose the crew is absolutely necessary, each man is assigned a particular and a special duty independent of the other men, and should he fail in its faithful discharge the loss of the vessel and its enterprise might possibly result.

Training For Service.

Far be it from the intention of this article to condone the existing policy of the Navy of the United States as regards the Negro, where unwritten law prescribes and precludes him from service above a designated status. It is well known that no Negro has ever graduated from the United States Naval Academy, at Annapolis, Maryland, which is primarily essential to receive a commission as a line officer of the Navy. It is true that some three or four Negroes have attempted to complete the course of instruction at this academy, but, their treatment, as a result of race prejudice, made their efforts futile, as well as their stay there more miserable than a decade of confinement in a Hun penitentiary. Intimidation, humiliation, and actual physical violence, notwithstanding their determination, finally resulted in the conclusion to abandon the coveted goal of becoming officers in the great Navy of the United States.

It is also known that notwithstanding the urgent pressure for experienced men to officer the expanding Navy as a result of the World War, it became necessary to commission hundreds of men, who as a result of their experience as enlisted men, are temporary officers. But none of these commissions was given to a Negro, despite the fact that scores of them had rendered honorable service of from ten to twenty years and were exceptionally qualified as stated by their commanding officers for these commissions. During the war there were approximately eleven thousand men commissioned as officers. A great majority of this number were commissioned as pay clerks, paymasters, medical officers, and other ranks, wherein no technical naval knowledge or experience is required. And it is strange to note that not a single Negro received one of these commissions.

Insufficient Number Of Officers.

In his annual report to the Congress of the United States, the Secretary of the Navy Department made the following statement: "The regular Navy personnel as it existed at the beginning of the war has been repeatedly combed for warrant officers and enlisted men competent for advancement to commissioned rank, and this source furnished experienced and capable officers. But more were needed and they came from new recruits. It early became evident that as the new men came into the service they should be tried out for officer qualifications and that those having talent should receive special instruction to prepare them for officer duty. Officer material schools were hastily improvised in the various naval districts at the outbreak of war to train the new men coming in, etc."

In the face of the above admission of the serious shortage of qualified men, it can not be understood why the awarding of commissions was made to inexperienced white boys with no prior naval experience or demonstrated ability in preference to the Negro, who has demonstrated his fitness and ability by years of faithful service in every phase of naval activity to which he has been given access.

German Propaganda Effort.

But, in spite of these outward and open acts of prejudice and oppression, the Negro never wavered in the loyal performance of any duty, however humble or arduous with which he was charged. And it might be mentioned that these acts of oppression were brought to his attention and emphasized by subtle German propagandists, who hoped to alienate his affections and devotion from his native country. As an example of this diabolical scheme, the following letter, which was dropped from German balloons over a sector held by Negro troops, in September, 1918, is quoted:

"To the Colored Soldiers and Sailors of the United States: Hello, boys! What are you doing over here? Fighting the Germans? Why? Have they ever done you any harm? Of course, some white folks and the lying English-American papers told you that the Germans ought to be wiped out for the sake of humanity and democracy. What is democracy? Personal freedom, all citizens enjoying the same rights socially and before the law. Do you enjoy the same rights as the white people do in America, the land of freedom and democracy? Or, are you not rather treated over there as second-class citizens? Can you go into a restaurant where white people dine? Can you get a seat in the theatre where white people sit? Can you get a berth or a seat in the railroad car, or can you even ride in the South in the same street car with white people? And how about the law? Is lynching and the most horrible crimes connected therewith, a lawful proceeding in a democratic country?

"Now, all this is entirely different in Germany, where they do like colored people, where they treat them as gentlemen and as white men, and quite a number of colored people have fine positions in business in Berlin and other German cities. Why, then, fight the Germans only for the benefit of Wall Street robbers and to protect the millions they have loaned to the English, French and Italians? You have been made the tool of the egotistical and rapacious rich in England and America and there is nothing in the whole game for you but broken bones, horrible wounds, spoiled health, or death. No satisfaction whatever will you get out of this unjust war. You have never seen Germany. So you are fools if you allow people to make you hate us. Come over and see for yourself. Let those do the fighting who make the profits out of the war. Don't allow them to use you as cannon fodder. To carry a gun in this service is not an honor, but a shame. Throw it away and come over to the German lines. You will find friends who will help you along."

The Propaganda Fails.

Such a piece of infamous treachery scarcely deserves comment; for, if the Negro had been the least inclined to be a traitor, he could not forget the atrocious treatment accorded the black man in the African colonies controlled by Germany. For the Negro well remembers the treachery of von Trotha, who invited the Herero chiefs to come in and make peace and promptly shot them in cold blood. And the words of his cruel and inhuman "Extermination Order" directing that every Herero man, woman, child or babe was to be killed and no prisoners taken. All of which had the sanction of Berlin.

But, aside from his intimate knowledge of German treachery and duplicity, a still higher principle inspired the Negro; for to forget the loyalty to his own native country in this hour of trial and darkness would be scandalous and shameful and would blacken the Negro in the eyes of the whole world. Of this class of treachery, the Negro is absolutely incapable. They have endured some of the greatest sacrifices and humiliations that could be demanded of a people, but, they always have kept before them ideals, founded on loyalty and devotion to duty, and never, in their darkest days, have they sought to gain their ends by treasonable means. For the path of treason is still an unknown path to the Negro. Their duty and their conscience alike bade them be faithful and true to their government and their flag in this hour of darkness and trouble.

Number Of Negroes Engaged.

During the World War, there were approximately ten thousand Negroes who voluntarily enlisted in the Navy of the United States. They were distributed throughout the various ratings of the enlisted status. Many of them were chief petty officers who had rendered years of faithful service and were regarded as experts in their profession, and, consequently, played an important part in the organization and function of the battle units. In the transport service, his powerful physical endurance and strength made him a determining factor in the Herculean efforts to supply men, munitions, and provisions for the battlefields of France. In order to appreciate the magnitude of his service, let us briefly note the following facts:

Two million American fighting men were safely landed in France. To do this the transport force of the Atlantic fleet of the United States had to be utilized. At the outbreak of the war the transport force was small, but it now comprises twenty-four cruisers, forty-two troop transports, and scores of other vessels, manned by three thousand officers and forty-one thousand enlisted men, two thousand of whom are Negroes.

Peril And Danger.

To think of the peril and dangers of this service at best, even in peace times, seamanship is a comfortless and cheerless calling. But in war, to the ordinary perils of the sea are added unusual hardships which reach their maximum in the dangers and perils of the war zone - the attack without warning of the invisible foe whose presence is too frequently known only by a terrific explosion, which casts the hapless crew adrift on surging seas, leagues from a friendly shore. Think of the terrific strain under which these men perform their perilous tasks. Gun crews on continuous duty, ever ready with the shot that might save the ship; the black men below in the fire room, expecting every moment to receive the fatal blast which would entrap them in a hideous death; the watch, ceaseless in its vigil by day and by night, peering through the darkness and the mist, conscious that upon their alertness depended the lives of all. Yet under these conditions of unprecedented hardships every black man performed his duty with the highest degree of courage and self-sacrifice.

We will mention one of the many instance of the matchless intrepidity of the men engaged in this hazardous service. In September, 1918, a transport with several hundred sick and wounded soldiers on board, was torpedoed when a short distance out from Brest. Thirty-six men of the fire room met their death in the fire and steam and boiling water of the stokehold. With two compartments flooded, their comrades dead and dying, with a seeming certainty that the attack would continue, which would mean that every man in the compartment where the torpedo struck would be drowned or burned to death. Yet despite all, when volunteers were called for to man the still undamaged furnaces to keep up steam for the run back to port, every man in the force stepped forward and said he was ready to go below.

Hard And Grinding Work.

There was nothing spectacular about this grinding duty. Winter and summer, by day and by night, in the fog and in the rain and in the ice, it demanded constant vigilance, unceasing toil, and extreme endurance. The work of this dangerous service was endless and its hardships and hazards are barely realized. During the winter storms of the north Atlantic the maddened seas all but engulfed these tiny but staunch transports, when for days they breasted the fury of the gale and defied the very elements in their struggle for mastery. No sleep then for the tired crew; no hot food; no dry clothes. Yet despite it all, with each hour perhaps the last, with death stalking through the staggering hulls, not a man - black or white - to the everlasting glory of the American Navy, not a man but felt himself especially favored in being assigned that duty.

Ceaseless Vigilance.

Since this country entered the war practically all the enemy's naval forces, except the submarines, have been blockaded in his ports by the naval forces of the Allies, and there has been no opportunity for naval engagements of a major character. The enemy's submarines, however, formed a continual menace to the safety of all our transports and shipping, necessitating the use of every effective means and the utmost vigilance for the protection of our vessels. Concentrated attacks were made by enemy U-boats on the ships that carried the very first contingent to Europe, and all that have gone since have faced this liability to attack. Our destroyers and patrol vessels, upon all of which Negroes served in addition to convoy duty, have waged an unceasing offensive warfare against the submarine. In spite of all this, our naval losses have been gratifyingly small. Not one American troop ship, as previously stated, has been torpedoed on the way to France, and but three, the Antilles, President Lincoln, and the Covington, were sunk on the return voyage.

Gratifying Results Of Naval Activity.

Only three fighting ships were lost as a result of enemy action - the patrol ship Alcedo, a converted yacht sunk off the coast of France, November 5, 1917; the torpedo boat destroyer Jacob Jones, sunk off the British coast, December 6, 1917, and the cruiser San Diego, sunk off Fire Island, off the New York coast, July 18, 1918, striking a mine supposedly set adrift by a German submarine. The transport Finland and the destroyer Cassin, which were torpedoed, reached port and were soon repaired and placed back in service. The transport Mount Vernon struck by a torpedo on September 5th, proceeded to port under its own steam and was repaired.

The most serious loss of life due to enemy activity was the loss of the coast guard cutter Tampa, with all on board, in Bristol Channel, England, on the night of September 26, 1918. The Tampa, which was doing escort duty, had gone ahead of the convoy. Vessels following heard the explosion, but when they reached the vicinity there were only bits of floating wreckage to show where the ship had gone down. Not one of the one hundred and eleven officers and enlisted men of her crew were rescued; and though it is believed she was sunk by a torpedo from an enemy submarine, the exact manner in which the vessel met its fate may never be known. Among the number of men lost on this vessel were at least a score of black men. Taking into consideration all the dangers and difficulties attending this service of the transport force, the comparatively light casualty list is eloquent testimony of an efficient personnel organized and trained under a wise administrative command.

The Negro In The Merchant Marine.

Now let us briefly consider the contribution of the Negro to the construction and development of the merchant marine, a force vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the war. When America entered the war, it is a well-known fact that her merchant marine was insignificant; and, to respond to the urgent appeal of France and her allies to hurry men, provisions and munitions, a gigantic task of constructing the necessary ships stared her in the face. For the Germans at this time were making a desperate effort to starve England, France and the other Allies by destroying their commerce with America and the world, by a resort, as was brazenly announced to the world, to a heartless campaign of ruthless submarine warfare. Therefore, the very first efforts of the United States were to use every power of the Navy to destroy and neutralize the effect of the lurking submarine and enter upon a policy of ship construction, which in its gigantic magnitude and comprehensiveness was unprecedented.

The manner in which the Negro generously contributed to the effectiveness of this policy is well known to all the world. For the very first record breaking riveting feat was won by a Negro crew at Sparrows Point, Maryland. His ability in this field of endeavor was ably demonstrated in all of the great industrial plants in which his services were so generously utilized. Heretofore, he had been debarred from identification in the capacity as a laborer in these plants; but, now, that war in all of its desperation was threatening the very existence of the country, the barriers of prejudice gave way and he again proved the falsity of the statement that the Negro could not handle machinery. The managers of great shipbuilding plants along the Atlantic seaboard testified before the Federal Shipbuilding Labor Adjustment Board that Negroes had worked on machines, gauged to as fine a degree as one one-thousandth of an inch with perfect satisfaction.

Wonderful Achievements.

To the achievements of the Navy, in erecting great training camps, destroyer and aviation bases, hospitals, in training thousands of men for oversea duty, the Army of merchant ships, the building of a vast fleet of smaller vessels, the construction of great warehouses at home and abroad, the manufacture of heavy guns and their mounts, the production of powder and technical ordnance must be added the most spectacular achievement of all - the repair of interned German ships, in all of which the Negro participated with zeal and enthusiasm and in many instances won the admiration and commendation of his superior officers.

When these vessels, many of them of the largest type of trans-Atlantic liners, were taken over by our government, it was found that the machinery of several had been seriously damaged by the maliciously planned and carefully executed sabotage of the crews. The principal injury was to the cylinders and other parts of the engines, and, as the passenger ships were potent factors in the transportation of troops, their immediate repair was of vital necessity. Nothing daunted by the magnitude of the past, our Navy undertook the repair of these broken cylinders by employing the system of electric welding, and so successful was this work, in which scores of black men were utilized, that during all the months of service in which these vessels have been engaged, not a single defect has developed.

Honor To Whom Honor Is Due.

All honor to the officers who risked their professional reputations and carried forward to complete success and accomplishment, which expert engine manufacturers considered impossible; and all honor to the patience, zeal, industry and intelligence of the noble band of laborers whose persistence and ceaseless endeavor made possible the accomplishment of these world-renowned examples of constructive and inventive American genius.

Let us not forget the mighty and tireless work of those in the Department whose efforts were as assiduous as their success was complete. From the humblest yeowoman upward to the Secretary of the Navy, through the Bureaus and their chiefs, all were animated by the same spirit of energy, of foresight, and determination to place the fleet on the highest basis of efficiency and strength. In this generous and sacrificing spirit, black men and black women, working side by side, shared in proportion and never wavered or faltered in the task of measuring up to the expectations of those whose confidence and regard are so highly esteemed.

Generous Recognition Of Service.

Another just and appreciated evidence of the generous recognition with which the consistency and faithfulness of his service was awarded, may be noted in the organization and development of the muster roll section of the Bureau of Navigation of the Navy Department. Owing to a widespread demand upon the part of the citizens of the country shortly after we entered the war, for accurate and specific information concerning the whereabouts of their kinsmen in the naval service, a demand which it was practically impossible to comply with in view of the ancient methods in vogue at the time in the file section of the Bureau of Navigation, and in further view of the fact of the unprecedented expansion of the enlisted personnel of the Navy, the Secretary of the Navy found it absolutely necessary to convene a conference of all the officials who had any positive and direct knowledge as to the details and operation of the file section.

This was done in order to evolve out of the multiplicity of seasoned counsel a competent and successful solution of the very important and grave problem which so heavily weighed upon the mind of the civil population of the country, when they were offering freely upon its altar their most treasured blood, as a precious sacrifice. Indeed, so important and so urgent became the necessity for an immediate and satisfactory solution of this problem that there was no evasion in a high browed manner of any creditable source of needed information. Accordingly, the Bureau of Navigation, in obedience to the inevitable expansion necessitated in all the Bureaus of the Navy by the exigencies of war, determined to organize and operate a muster roll section, charged primarily with the duty of apprehending the present whereabouts of every man of the enlisted personnel in a systematic and scientific manner.

Organization Of The Muster Roll Section.

The execution of the very essential duty of chief of the muster roll section was entrusted to John T. Rishcr, a colored man, to whom was given plenary power to engage and select his corps of assistants. Of course, Mr. Risher determined immediately in the face of all opposing precedents, to fully utilize the services, abilities and talents of the colored youth of the country, upon whose educational development millions of dollars had been spent in the past. In consequence, more than a dozen young colored women have been engaged in the capacity of yeowomen in this muster roll section. This is quite a novel experiment, as it is the first time in the history of the Navy of the United States that colored women have been employed in any clerical capacity. And it may be noted that while many young colored men have enlisted in the mess branch of the service, it was reserved to young colored women to invade successfully the yeoman branch, thereby establishing a precedent. There are all cool, clear-headed and well-poised, evincing at all times, in the language of a white chief yeowoman: 'A tidiness and appropriate demeanor both on and off duty which the girls of the white race might do well to emulate." The work of this section has proven highly efficient and satisfactory, as the plans in vogue there under its modern management are both scientific and accurate. Many of the superior officials have scrutinized the experiment very closely and are a unit in the sincerity of their admiration of its success and effectiveness.

Personnel Of The Muster Roll Section.

The personnel of the muster roll section is divided in three classes, to wit:

(a) Civil service employees, who are Messrs. Albert D. Smith of Texas; David C. Johnson of Texas; George W. Beasley of Massachusetts, and W. T. Howard of Louisiana. All of the above have had years of valuable experience and are considered expert in all matters pertaining to the enlisted personnel of the Navy of the United States.

(b) Yeowomen, who are as follows: Misses Armelda H. Greene of Mississippi; Pocahontas A. Jackson of Mississippi; Catherine E. Finch of Mississippi; Fannie A. Foote of Texas; Ruth A. Wellborn of Washington, D. C.; Olga F. Jones, Washington, D. C.; Sarah Davis of Maryland ; Sarah E. Howard of Mississippi; Marie E. Mitchell, Washington, D. C; Anna G. Smallwood, Washington, D. C.; Maud C. Williams of Texas; Carroll E. Washington of Mississippi; Joseph B. Washington of Mississippi; Inez B. Mcintosh of Mississippi.

(c) Young men of the naval reserve force, who are: Messrs. William R. Minor of Virginia; L. D. Boyd, Brown Boyd of Virginia; Minter G. Edwards of Mississippi; Fred Jolie of Louisiana; M. T. Malvan, Washington, D. C.; U. S. Brooks; Thomas C. Bowler; Albert L. Gaskins, Washington, D. C; Daniel Vickers of Alabama, and Mr. Fuller.

Signing Of The Armistice.

On November 11, 1918, there came that long expected and welcome message announcing to an anxious and war-weary world that an armistice had been concluded, by the terms of which actual hostilities were to cease.

On November 21, 1918, five American dreadnaughts were in that far-flung double line of Allied ships, through which passed in surrender the dreadnaughts, cruisers and destroyers of the second most powerful Navy in the world. When Admiral Beatty sent his famous signal, "The German flag is to be hauled down at 3:57 and is not to be hoisted again without permission," the work of our Navy as a battle unit in the war zone was over. And the following tribute from Gen. John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, was sent to the commander of the United States naval forces: "Permit me to send to the force commander, the officers, and men of the American Navy, in European waters, the most cordial greetings of the American Expeditionary Force. The bond which joins together all men of American blood has been mightily strengthened and deepened by the rough hand of war.