The Navy Department Library

THE NAVY DEPARTMENT A Brief History until 1945

NAVAL HISTORICAL FOUNDATION PUBLICATION

PDF Version [9.4MB]

OFFICERS

President-Vice Admiral W.S. DeLany

Directors |

Vice Presidents |

| Admiral R.B. Carney (Chairman) | Admiral G.W. Anderson |

| Rear Admiral Parke H. Brandy | Admiral A.A. Burke |

| Admiral Robert L. Dennison | Rear Admiral Neil K. Dietrich (Exec. V.P.) |

| Honorable W. John Kenney | Rear Admiral E.M. Eller (Curator) |

| Honorable John T. Koehler | Rear Admiral J.B. Heffernan (Secy.) |

| Rear Admiral L.L. Strauss | Rear Admiral F. Kent Loomis (Treas.) |

| Mrs. J.S. Taylor | Admiral Jerauld Wright |

Honorary Vice Presidents

Mr. Charles Francis Adams |

Admiral John Hyland |

| Dr. James Phinney Baxter III | Admiral R.E. Ingersoll |

| Captain Charles Bittenger, USNR | Mr. Francis V. Kughler |

| Honorable John Nicholas Brown | Admiral Emory S. Land |

| Dr. Leonard Carmichael | Admiral Thomas H. Moorer |

| Honorable John H. Chafee | Admiral Ben Moreell (CEC) |

| General Leonard F. Chapman Jr, USMC | Rear Admiral Samuel E. Morison, USNR |

| Mr. Henry B. du Pont | Admiral Albert Gallatin Noble |

| Honorable Ferdinand Eberstadt | Admiral Arthur W. Radford |

| Mr. David E. Finley | Dr. S. Dillon Ripley |

| Honorable Thomas S. Gates, Jr. | Vice Admiral W.R. Smedberg III |

| Admiral Thomas C. Hart | Admiral Willard J. Smith, USCG |

| Admiral H. Kent Hewitt | Admiral Harold R. Stark |

| Admiral Ephraim P. Holmes | Honorable John L. Sullivan |

| Commander Walter Muir Whitehill, USNR |

Trustees

Mr. Joel Barlow |

Mr. Melville Bell Gorosvenor |

| Rear Admiral John J. Bergen, USNR | Rear Admiral Frederick J. Harlfinger II |

| Rear Admiral Bernhard H. Bieri, Jr. (SC) | Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid |

| Rear Admiral Frank A. Braisted | Mrs. McCook Knox |

| Commander M.V. Brewington, USNR | Captain George F. Kosco |

| Rear Admiral James F. Calvert | Lieutenant General V.M. Krulak, USMC |

| Captain a. Winfield Chapin, USNR | Rear Admiral Joseph B. McDevitt |

| Admiral Bernard A. Clarey | Colonel John H. Magruder, USMC |

| Vice Admiral Richard G. Colbert | Vice Admiral Vincent R. Murphy |

| Vice Admiral George M. Davis | Vice Admiral A.M. Pride |

| Honorable Charles S. Dewey | Vice Admiral W.F. Raborn |

| Captain John E. Dingwell | Rear Admiral Joseph E. Rice |

| Mrs. George du Manior | Admiral James S. Russell |

| Vice Admiral Charles K. Duncan | General L.C. Shepherd, Jr., USMC |

| Vice Admiral George C. Dyer | Captain Paul Revere Smith, USNR |

| Rear Admiral Walter M. Enger (CEC) | Rear Admiral Nathan Sonenshein |

| Honorable William B. Franke | General Gerald C. Thomas, USMC |

| Admiral I.G. Galantin | Rear Admiral R.L. Townsend |

| Rear Admiral L.R. Geis | Rear Admiral Thomas J. Walker III |

| Rear Admiral J.F. Greenslade | Vice Admiral Charles Wellborn, Jr. |

| Admiral Charles D. Griffin | Rear Admiral Mark W, Woods |

INFORMATION ON PRINTS, PAMPHLETS, BOOKS AND OTHER FOUNDATION

PUBLICATIONS MAY BE OBTAINED BY WRITING TO THE FOUNDATION.

FOREWORD

Until the military services were unified, the Navy was free, within Congressional limitations, to set up its own organizational structure.

The Continental Navy was governed by “Marine Committee.” This was superseded in 1779 by the Board of Admiralty. The Navy Department, as such, with its own Secretary was established on 30 April 1798. A Board of Commissioners was added in February 1815. The most permanent change in the organization of the Department came in 1842 when the Bureau system was established. Originally there were five Bureaus each with its own Chief.

For more than a century, and up until after World War II, the number, names and cognizance responsibilities of the Bureaus changed, and an Office of the Chief of Naval Operations was established in 1915. The Bureau System, however, remained the basis of the Navy Department organization.

Many years ago Pericles is recorded as saying: “If the record here shown seems good, consider that it was purchased by valiant men and by men that had learned their duty, by men who acted with honor in making a great contribution to the nation and gave an unquestionable account of themselves in battle.”

It is the intent of this presentation to cover briefly the highlights of these changes. It does not appear to be generally appreciated that the Bureau System was in effect during five successful and winning wars and the many intervening lean and peaceful years. Of course, there were changes but complete reorganization was not accepted as a cureall [sic] for all the problems of growth, technical advancements and management problems.

Sources for material in this pamphlet are: Administration of the Navy Department in World War II by Rear Admiral Julius A. Furer, USN, and A Brief History of the Organization of the Navy Department by Captain A.W. Johnson, USN.

The Continental Navy was the Navy of the Revolutionary War. Initially, directives relating to naval administration and operations originated in the “Marine Committee” composed of 13 members, one delegate from each colony. In 1779, this Committee was superseded by the “Board of Admiralty” consisting of “three Commissioners not members of Congress and a Secretary to whose management all affairs of the Continental Navy were committed subsequent nevertheless to the consent of Congress.”

After 1781, public indifference contributed to the gradual disappearance of this Navy. Its last ship, the Alliance was sold in 1785. In fact, when the Constitution for the Federal Government became effective in 1789, the Secretary of War was charged with the administration of both the Army and the Navy. The latter was an easy task—there was no Navy.

President Washington realized the naval weakness of the new Nation. He had a keen appreciation and understanding of the importance of sea power. It is unquestionably a fact that this led to his making arrangements for French naval support during the war. He wrote to General Lafayette in 1781: “…without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive, and with it everything honorable and glorious. A constant naval superiority would terminate the war speedily; without it, I do not know that it will ever be terminated honorably.” When Admiral de Grasse prevented the British fleet from relieving Cornwallis at Yorktown, the war was speedily terminated.

The actions of the Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean led the Congress in 1794 to authorize the construction of six frigates. Among these were the Constitution and Constellation, still afloat today. Again, public and congressional apathy was responsible for slow progress of this program. In fact, it was almost abandoned. Four years later, however, the United States became involved in the quasi-war with France. The Secretary of War at that time came under severe criticism for the lack of preparedness of the Navy.

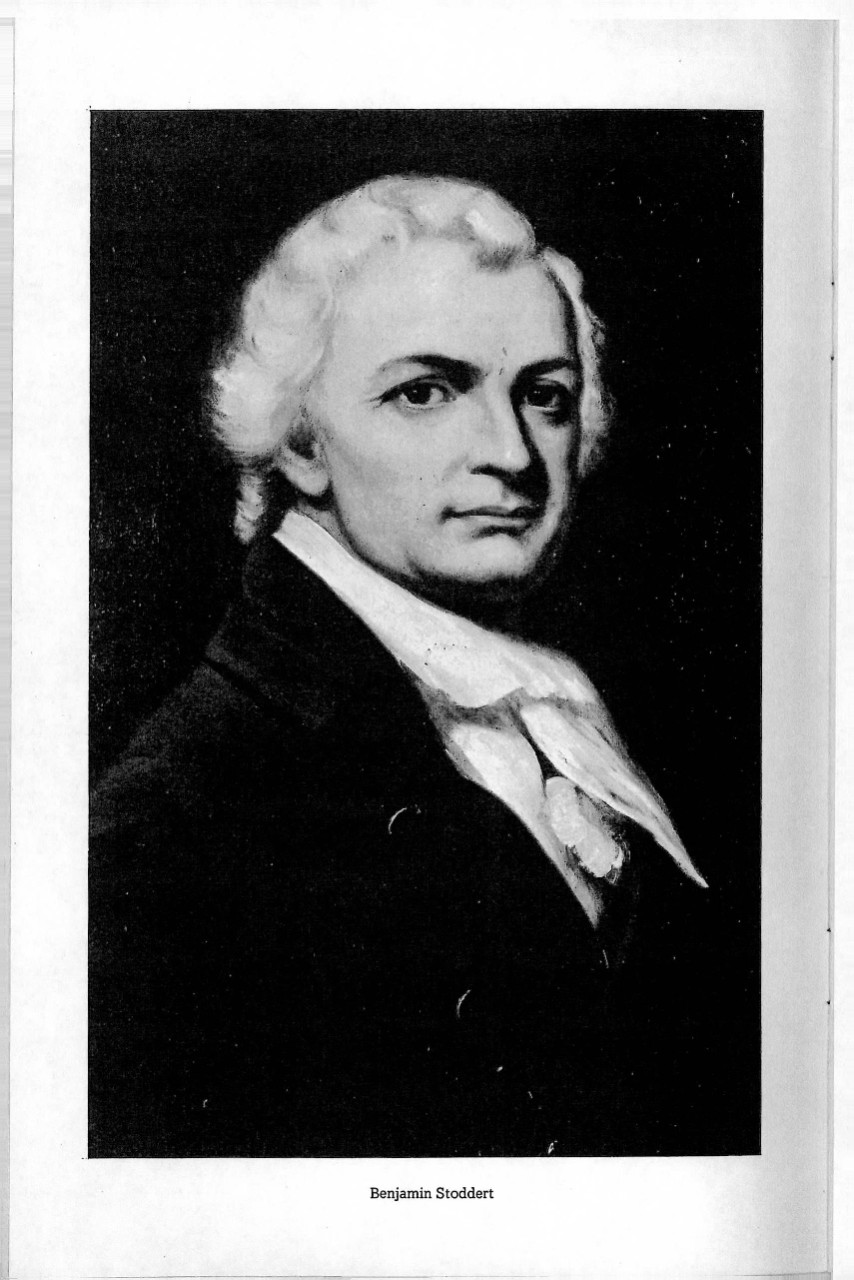

The Navy Department, as such, came into being on 30 April 1798, with a Secretary of the Navy as its chief officer. The law reads that: “The duty of this officer shall be to execute such orders as he shall receive from the President of the United States relative to the procurement of naval stores and materials, and the construction, armament, equipment, and employment of vessels of war as well as all other matters connection with the Naval Establishment of the United States.”

George Cabot of Massachusetts was nominated and confirmed on 30 March 1798 as the first Secretary of the Navy. He declined

1

the appointment. In so doing, he said: “The head of the Navy Department should possess considerable knowledge of maritime affairs; but this should be elementary as well as practical, including the principles of naval architecture and naval tactics. Above all, he should possess the inestimable secret of rendering a naval force invincible by any equal force of the enemy. Thus [sic] a knowledge of the human heart will constitute an essential ingredient in the character of this officer, that he may be able to convert every incident to the elevation of the American seamen. Suffer me to ask how a man who has led a life of indolence for twenty years can be rendered physically capable of these various exertions.”

Benjamin Stoddert, of Georgetown, was nominated in his place and became the first Secretary of the Navy. He understood seagoing, if not naval, requirements and operations. There were only a few ships in the Navy at that time. About one half dozen employees could supervise and handle the business in the Department itself. Naval agents in the principal seaports from Maine to Georgia handled the Navy’s business outside of the Secretary’s office. The command functions and operations of the ships themselves did not lay a heavy burden on the Secretary. The telegraph cable and wireless had not yet come into use. Once a ship was clear of port it was literally a free agent. The command was on its own to carry out as feasible, within local circumstances and sound judgement, the general instructions given by the Secretary prior to sailing. (See Admiral E.J. King “Philosophy of Command” in appendix.)

The War of 1812 brought the first real increase in the Navy. By October 1814, the Navy consisted of 11,000 officers and men. There were 450 men at sea, 405 in British prisons, 3260 on the Great Lakes, and 6512 in the maritime frontiers. There were 75 vessels on the Navy List and expenditures had grown from $1,900,000 in 1811 to $8,660,000 in 1815. The Chief Clerk of the Navy Department was the Secretary of the Navy’s principal civilian assistant and was a powerful figure. There was a Chief Clerk in the office until 1941. Then it was replaced by the Administrative Office of the Secretary. The growth emphasized the need for more assistance to administer the Office of the Secretary. It showed, too, that he especially needed the help of professional naval officers. As a result, and as of 7 February 1815, a law was passed “to alter and amend the several Acts establishing a Navy Department by adding thereto a Board of Commissioners.” The Board was to be composed of three Post Captains of the Navy to be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. The law provided that nothing in the Act was to be construed “to take from the Secretary of the Navy his control and direction of the naval forces of the United States, as now by law possessed.” As superintended by the Secretary, the Board was to “discharge all the ministerial duties of said office, relative to the procurement of naval stores and materials and the construction, armament, equipment, and employment

2

of vessels of war as well as all other matters connected with the naval establishment of the United States.”

The Board met initially on 25 April 1815. Within one month it had its first clash with the Secretary. The specific problem was whether Secretary Crowninshield was obliged to tell the Commissioners “the destination of a squadron.” President Madison resolved the dispute in a letter to the Secretary of the Navy in which he set forth that the Secretary was responsible only to the President; and the powers of the Board were determined by the Secretary. He determined that the Commissioners were to handle the material side of the Navy, i.e., the building, repair and equipping of the ships, together with the supervision of the navy yards. The military functions were to be the responsibility of the Secretary. These included appointment and assignment of officers, discipline of naval personnel, the employment and use of ships. It will be noted that then the responsibilities of the Secretary were directed toward naval command, while those of the Commissioners were toward logistics. Over the years the opposite concept emerged. The command function responsibility passed to the Chief of Naval Operations. The requirements of logistics were implemented by the Bureau system as a responsibility of the Secretary of the Navy’s civilian executives and naval technical assistants.

Until 1815 the administration of the Navy was in civilian hands exclusively. During that time the Navy fought an undeclared war with France, the Barbary pirates, and the War of 1812 with England. From 1815 to 1842 the Board of Commissioners was the principal adviser to the Secretary. There were no wars during that period. The Navy did progress materially, however, and saw the beginning of the steam Navy. It is not too surprising to note that this change was opposed by many senior officers. Secretary of the Navy Paulding said, “I will never consent to see our grand old ships supplemented by these new and ugly monsters. I am steamed to death.” In 1841, however, the side-wheelers Mississippi and Missouri were built. One year later the first steam frigate Michigan was built. This later became the Wolverine and was turned over to the City Congress of Erie in 1927. The first shell guns came into use, and in 1841 Congress appropriated $50,000 for experiments in ordinance. In 1844 this work received a serious set back when the gun called the “Peacemaker,” mounted on U.S.S. Princeton, burst during test firing. It killed the Secretary of State Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Gilmer. President Tyler had just gone below and escaped.

The introduction of steam propulsion led to the establishment of a Naval Corps of Steam Engineers. In 1842 an Act of Congress established such a Corps with an Engineer in Chief at a salary of $3,000 per year. The Hydrographic Office and Naval Observatory were established in 1840 with the Department of Charts and Instruments.

3

The necessity to functionalize the distribution of work within the Navy Department led Secretary Upshur to the conclusion that a reorganization was necessary. This eventuated into the “Bureau System” as established by Congress on 31 August 1842. Five Bureaus were created. Each was headed by a Bureau Chief with an indefinite term. The Secretary’s office was enlarged to include a Chief Clerk and nine other clerks. The allowance for other Bureaus were also prescribed with: (1) Construction Equipment and Repair—clerks; (3) Navy Yards and Docks—one civil engineer, a draftsman, and 3 clerks; (4) Ordnance and Hydrography—1 draftsman and 3 clerks; and (5) Medicine and Surgery—an assistant surgeon and 2 clerks.

It so happened that four of the five newly created Bureau Chiefs were the three Navy Commissioners and the Secretary of that Board. There were not, therefore, too many basic changes in administration. One of the real problems arose from the fact that the law intended the Bureau Chiefs should be technically qualified in the work of their own Bureaus. In fact, the organic act stated that the Chief of Bureau Construction, Equipment, and Repair be a “skillful naval constructor.” The first Bureau Chief was a former Commissioner,

4

David Conner, a line officer. This caused much bad feeling. In 1853 Congress directed that the Bureau Chief “be a skillful constructor as required by the act approved 31 August 1842, instead of a captain of the line,” and the intended assignment was made. It took until 1898, however, to get an officer of the Civil Engineer Corps as Chief of Bureau of Yards and Docks.

Human relations within the Navy also came under consideration about this time. This resulted in certain changes in longstanding practices including flogging and the issuance of grog. In 1842, temperance advocates tried to make the Navy dry for all hands. Twenty years later, in 1862, Congress passed a law that the “Spirit ration in the Navy of the United States shall forever cease.” By General Order #99 of 1 June 1914, Secretary Daniels made the Navy dry. In 1850 Congress abolished flogging. Many old hands opposed this because they considered it a manly and seamanlike form of punishment. Five years later, discipline had become a serious problem. Congress established the Summary Court-Martial. Discipline was reestablished.

Officers of the Staff, especially the Medical Corps, which had been established in 1806, were anxious to acquire assimilated rank and the prestige of the naval uniform. The line opposed this effort. In 1846, however, Secretary Bancroft issued a General Order granting rank to the Medical Corps. In 1847 Secretary Mason did the same for purser. These General Orders were sanctioned by Congress in 1854. It took until 1859 for Secretary Toucey to do this for Engineers, and until 1866 for the Naval Constructors. In 1867 the President was authorized to appoint one civil engineer to each yard in a commissioned rank.

In 1855 a law to increase the efficiency of the Navy was intended to weed out the inefficient officers. A board of 15 officers was appointed and found 201 officers incapacitated. It recommended that 49 of these be dismissed, 81 retired on furlough pay, and 71 retired on leave of absence pay. When the President approved this, the press took up the cause of these officers. State legislatures passed resolutions in behalf of their “native sons.” Two years later, in 1857, Congress approved the right of these officers to be heard before a Court of Inquiry. Some were restored. Lieutenant M.F. Maury with all his achievements in hydrography was not among them.

The intent to insure [sic] quality promotion of officers resulted in the establishment of an advisory board on promotion (a selection board) in 1862. In 1864 the present Naval Examining Board was established by Congress.

In 1860 the Navy had 90 ships, 1300 officers (about ¼ resigned and went South), and 7600 enlisted men. During the Civil War, Secretary Gideon Welles, who had been Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing, became Secretary of the Navy. He recommended creation of additional Bureaus and, as of 5 July 1862, the

5

Congress created eight instead of the original five Bureaus: (1) Yards and Docks, (2) Equipment and Recruiting, (3) Navigation, (4) Ordnance, (5) Construction and Repair, (6) Steam Engineering, (7) Provisions and Clothing (became Bureau of Supplies and Accounts on 19 July 1892), and (8) Medicine and Surgery. The Bureau of Navigation as set-up was a scientific Bureau. It included the Naval Observatory, Hydrographic Office, Nautical Almanac Office, and the Naval Academy. Until the Civil War, it was the practice to recruit ships’ crews locally including some officers. The expanding Navy made it necessary to give attention to personnel recruiting and administration. These functions were given to the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting. In addition, however, an “Office of Detail” was set-up in the Secretary of the Navy’s office, staffed by a single officer (later three were assigned). These officers took care of the appointment and training of officers. In April of 1865, however, that office was placed in the Bureau of Navigation. On 4 October 1884, Secretary Chandler by a General Order put the Bureau of Navigation’s Office of Detail back in the Secretary’s office. His successor, Secretary Whitney, on 5 May 1885 returned it to the Bureau of Navigation.

By an Act of Congress of 31 July 1861, the office of an Assistant Secretary of the Navy was established to perform such duties “as shall be prescribed by the Secretary of the Navy or as may be required by law, and in the absence of the head of the Department he will act as the Secretary of the Navy.”

The first appointee was Gustavus V. Fox. He had served 18 years as a midshipman and officer in the United States Navy, and then resigned in 1856 to go into business.

That office lapsed in 1869 but was reestablished in 1890 to insure there was a civilian of appropriate rank to continue civilian control in the absence of the Secretary.

Welles also requested the Congress to create the Office of Solicitor and Naval Judge Advocate General. By the Act of 2 March 1865, Congress authorized the President “to appoint by and with the advice and consent of the Senate for service during the rebellion and one year thereafter an officer of the Navy Department to be called the Solicitor and Naval Judge Advocate General.” The Act of 22 June 1870 established the Department of Justice and transferred the Navy Judge Advocate General to that Department to be known as the Naval Solicitor. That office was abolished in the Appropriation Act of 1878. The Secretary of the Navy appointed Captain William B. Remey, USMC, as Acting Judge Advocate General.

An Act of Congress dated 8 June 1880 reestablished the Office of Judge Advocate General and went on to say “…And the office of the said Judge Advocate General shall be in the Navy Department, where he shall, under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, receive, revise, and have recorded the proceedings of all courts- martial of inquiry, and boards for the examination of officers for

6

retirement and promotion in the naval service, and perform such other duties as have heretofore been performed by the Solicitor and Naval Judge Advocate General.” The language of the Act was explicit as to military law, beyond that it was ambiguous. In 1901 Congress appropriated specifically “for a solicitor to be an assistant to the Judge Advocate General of the Navy.” The salary to be $2,500 per year. The expanding Navy brought more work into the field of commercial law. In 1940 a special study group recommended a new division in the Office of the Under Secretary be established and manned by civilian lawyers. This became the Procurement Legal Division as established on 10 September 1941. Branch offices were set up in each Bureau on 3 August 1944. This division became the Office of the General Counsel. It was accepted as the business and commercial law office of the Navy Department. In June 1940 there were 22 civilian lawyers in the JAG’s office. In 1944 there were 160 in the Office of General Counsel.

At the end of the Civil War there were 6700 officers, 51,500 enlisted men and about 670 ships. On 1 June 1865 the Navy Department consisted of 89 persons, including the Secretary of the Navy, naval officers, clerks, draftsmen and messengers.

For about 20 years after the Civil War, the Navy went into decline. David D. Porter, at the period when the Navy touched its low-water mark, said:

It would be much better to have no navy at all than one like the present, half-armed and with only half-speed unless we inform the world that our establishment is only intended for times of peace, and to protect missionaries against the South Sea savages and Eastern fanatics. One such ship as the British ironclad Invincible could put our fleet “hor de combat” in a short time.The following is an excerpt from a communication issued by Secretary Thompson on 3 April 1877:

The Secretary of the Navy regrets that it has become his duty to announce to the officers of the naval service that, the amount of money found by him in the Treasury of the United States, to the credit of the appropriation “Pay of the Navy” is insufficient to pay the officers for the months of April, May and June***.

The “List of Vessels of the U.S. Navy” of February 1880 showed 65 operating steam vessels, 22 sailing vessels and 26 old ironclad vessels.

On 25 June 1889 Secretary Tracy made radical changes in the duties of two Bureaus. Bureau of Navigation was given cognizance over all matters related to naval personnel. The gathering of naval intelligence was a device set-up in the Bureau of Navigation in 1882.

Bureau of Equipment was given cognizance of those duties of the Bureau of Navigation relating to the Hydrographic Office, Naval Observatory, and electrical lighting, etc. That Bureau sought to

7

develop all electrical installations afloat, until it was abolished in 1914 by an Act of Congress. At that time, however, some of the scientific activities of the Naval Observatory were again put back under the cognizance of Bureau of Navigation. It was not until 1942 when Bureau of Navigation became the Bureau of Personnel that its function concerned only personnel.

Secretary Tracy, partly to satisfy the proponents of the General Staff for the Navy, set up the “Board on Construction.” It was composed of the Chiefs of Bureau of Yards and Docks, Ordnance, Equipment, Construction and Repair, and Steam Engineering. It dealt with characteristics of new ships, development of navy yards, and localities of coaling stations. It functioned for about 20 years, then died a natural death. Commodore George Dewey was an early Chairman and Chief of Bureau of Equipment.

It is interesting to note that the General Order #372 of 25 June 1889, which redistributed the duties of the Bureaus, provided that the Bureau of Navigation be assigned the functions that later under general terms “readiness of the Navy for war” became the keystone of the structure of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. In his annual report Secretary Tracy said in 1889: “The fleet including vessels, officers, and seamen—training, assignment enlistment, inspection and practice—falls under the Bureau of Navigation.”

By 1894 the United States Navy ranked sixth in naval power behind Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Germany. Rebuilding it, as can be expected, raised political claims for credit by both political parties. Factually, Theodore Roosevelt was the person really responsible.

It was in 1898 when war was declared on Spain that a Naval War Board or Naval Strategy Board was set up. Its members were: Rear Admiral Sicard, Commodore Crowninshield, Captain A.S. Barker and Assistant Secretary Theodore Roosevelt. In 1898 Roosevelt and Baker left and Mahan was added. The Board was dissolved after the war and fleet operations reverted to Bureau of Navigation. The war experience showed the necessity for a body to study strategic problems to formulate war plans. This resulted in the creation of the General Board on 13 March 1900, by General Order #544 of Secretary Long.

Admiral Dewey chaired the General Board for 17 years. Its initial members were the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, the Chief Intelligence Officer and his principal assistant, the President of the Naval War College and his principal assistant, plus three other line officers. Its mission was “to insure efficient preparation of the Fleet in case of war and for the naval defense of the coast.” Rear Admiral Henry C. Taylor was Chief of the Bureau of Navigation at that time and chaired the Executive Committee until his death in 1904. The combination of Taylor and Dewey got the Board off to a good start. Upon the death of Admiral Dewey it became the policy to assign a very senior officer as Chairman of the Board. That applied to members as well. Their naval experience and ability, plus

8

the fact that this assignment was probably their last before retirement, left few axes to be ground. During World War II Secretaries Edison, Know, and Forrestal found their serviced invaluable. An effort in 1904 to give this Board legal status and administrative powers failed after lengthy hearings before the House NavalAffairs [sic] Committee.

Throughout the life of the Navy, Boards have been used extensively to assist the Secretary of the Navy in his administrative functions. Many of these have become a permanent part of the administrative machinery of the Navy Department. In the spring of 1861 Secretary Welles appointed his “Confidential Board” composed of the Chiefs of the Bureaus. Its duties were “considering and acting upon such subjects connected with the naval service as may be submitted to them by the Department for their opinion at this important junction of our national affairs.” In 1864 an effort was made to create a “Board of Naval Administrators” changed to a “Board of Admiralty” in 1865. The Grimes Bill before Congress tried to set up a “Board of Naval Survey.” These Boards were to be composed of line officers. The idea behind all of this was more direct control of the Navy Department by command officers. Secretary of the Navy did not approve these ideas and they failed authorization. The Board of Inspection and Survey dates back to the first steel ship in 1880 with procedures for conformity with plans and specifications. Among the oldest Statutory Boards are Naval Examining Board, Board of Medical Examiners, and Naval Retiring Board.

The oldest joint board to handle inter-service problems was the “Joint Board.” It was established in 1903 to meet a requirement for joint Army-Navy planning. It never received statutory authorization but operated by mutual agreement of the Secretaries. President Wilson suspended its operation between 1914-1919 because he considered Board matters to be his prerogative. It was reestablished in 1919 with naval members prescribed to be the Chief of Naval Operations, the Assistant Chief of Naval Operations, and the Director of the War Plans Division. The Joint Army-Navy Munitions Board was in operation before the war in 1939. At that time practically all Joint Boards were placed directly under the President as the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy.

In 1909, Secretary of the Navy, George von L. Meyer, made a radical change in the Navy Department organization. He established the “Naval Aide System” by creating four general divisions of the Department. They were: Operations of the Fleet, Personnel, Material, and Inspections. Each division was headed by an officer of the line called an “Aide.” The stated duties of the Aides were “to aid the Secretary in efficiently administering the affairs of the Navy Department.” The Secretary, Assistant Secretary, and Aides me t [sic] periodically but the Aides had no executive authority; their duties were advisory. The real intent of the system was to have the line officers control the operations, readiness, and logistic support of the fleet.

10

The Secretary was so anxious to make this reorganization that, instead of asking the Congress for authority to do so, he asked the Attorney General for a ruling as to whether it could be made through a change in Navy Regulations. Although the ruling was favorable, it added—that the fact Congress made appropriations to a Bureau for a specific purpose precluded the Secretary of the Navy from assigning work in question to any Bureau except the one named during the life of such an appropriation. This ruling remained effective until passage of the National Security Act in 1947. It had a profound effect in fixing the limits of the various Bureaus. It also strengthened the hold of the Committees of Congress on the naval purse strings. This did, however, lead to added detailed and specific lines in each Bureau’s appropriation.

Actually, Congress never did give statutory approval to this reorganization.

Four years later when Secretary Daniels became SecNav in 1913, he disliked the system and eliminated all but the Aide for Operations. On the recommendation of Admiral Dewey, the Secretary retained Admiral Bradley A. Fiske who was then serving in that capacity. Fiske worked with Congressman Richard P. Hobson, of the Naval Construction Corps and a Spanish war hero, to win the unanimous approval of the House Naval Affairs Committee to have the following incorporated in the Naval Appropriation Bill of 1915:

There shall be a Chief of Naval Operations, who shall be an officer on the active list of the Navy not below the grade of Rear Admiral, appointed for a term of four years by the President, by and with the advice of the Senate, who, under the Secretary of the Navy, shall be responsible for the readiness of the Navy for war and be charged with its general direction.

All orders issued by the Chief of Naval Operations in performing the duties assigned him shall be performed under the authority of the Secretary of the Navy, and his orders shall be considered as emanating from the Secretary, and [sic] shall have full force and effect as such. To assist the Chief of Naval Operations in preparing general and detailed plans of war, there shall be assigned for this exclusive duty not less than fifteen officers of and above the rank of Lieutenant Commander of the Navy and Major of the Marine Corps.

SecNav did not approve this language because it gave too much power in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. The modification which he approved [sic] and which became law on 3 March 1915 read:

There shall be a Chief of Naval Operations, who shall be an officer on the active list of the Navy appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, from among the officers of the line of the Navy not below the grade of Captain for a period of four years, who shall,

11

under the direction of the Secretary, be charged with the operations of the fleet,and [sic] with preparation and readiness of plans for its use in war.

During the temporary absence of the Secretary and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the Chief of Naval Operations shall be next in succession to act as Secretary of the Navy.

The significant difference between the two versions of the duties of the Chief of Naval Operations will be noted to be the words “with the operations of the fleet, and with the preparation and readiness of plans for its use in war,” in the later version as against “responsible for the readiness of the Navy for war and be charged with its general direction” in the earlier. This definitely did not give the line CNO direct authority over the Bureau Chiefs.

Captain W. S. Benson was appointed to be the first Chief of Naval Operations and assumed such duty on 11 May 1915. On 29 August 1916 Congress authorized the rank of Admiral for the Chief of Naval Operations and approved that:

Hereafter the Chief of Naval Operations, while so serving as such Chief of Naval Operations, shall have the rank and title of Admiral, to take rank next after the Admiral of the Navy, and shall, while so serving as Chief of Naval Operations, receive the pay of $10,000 per annum and no allowances. All orders issued by the Chief of Naval Operations in performing the duties assigned him shall be performed under the authority of the Secretary of the Navy, and for his exclusive duty not less than fifteen officers of and above the rank of Lieutenant Commander of the Navy or Major of the Marine Corps: Provided, that if an officer of the grade of captain be appointed Chief of Naval Operations he shall have the rank and title of Admiral, as above provided; while holding that position: Provided further, that should an officer, while serving as Chief of Naval Operations, be retired from active service he shall be retired with the lineal rank and the retired pay to which he would be entitled had he not been serving as Chief of Naval Operations.

This same act made provision for promotion of officers above Lieutenant Commander by selection. It also fixed the number of officers in the grades of the line and staff corps. The Dental Corps and Naval Flying Corps were also then established.

World War I broke out soon after this organization was set up. It was effective because the Chief of Naval Operations afforded a central coordinating agency through which the Bureaus willingly worked.

After the war, however, the duties of the Chief of Naval Operations again came under interpretive challenge. The CNO contended

12

that his responsibility in connection “with the preparation and readiness of its (the fleet) use in war” gave him authority to give direct orders to the Bureaus. The Bureau Chiefs did not agree. In 1921 SecNav appointed a Board of Naval Officers to “consider and recommend such changes in the interest of efficiency and economy as may be deemed necessary in the organization of the Navy Department.” The results were not definitive but did bring an addition to Navy Regulations in 1924 which broadened the duties and powers of the Chief of Naval Operations. An additional paragraph to Art. 433 read: “He shall so coordinate all repairs and alterations to vessels and the supply of personnel therefor as to insure maximum readiness of the fleet for war.” The Bureau Chiefs challenged the legality of this article. Congressman Byrnes, in the House of Representatives, offered an amendment to the Naval Appropriations Bill of 1924:

Provided. That no money appropriated by this Act shall be available for the pay of any commissioned officers of the Navy while attached to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations engaged upon work not specifically assigned by law to such office.

The amendment passed the House. The Senate, however, rejected it.

This article was still in effect in 1933, when Secretary of the Navy Swanson appointed a Board under Assistant Secretary of the Navy Henry L. Roosevelt to investigate naval organization. Included was a study on the question of amalgamating the Line, Staff Corps, and Marine Corps. Admiral William H. Standley became CNO in July 1933 and brought his responsibilities before the Board. It was not only the Chiefs of technical Bureaus and Staff Corps officers who challenged the Chief of Naval Operations. Admiral W. D. Leahy was then Chief of the Bureau of Navigation as a line officer and was a strong proponent of bureau authority. President Roosevelt became interested in the dispute and wrote the Secretary of the Navy on 2 March 1934:

My thought, therefore, on this question is that Article 433 of the Navy Regulations should remain in force. By this, I mean that the Chief of Naval Operations should coordinate to (sic) all repairs and alterations to vessels, etc., by retaining constant and frequent touch with the heads of bureaus and offices. But at the same time, the orders to Bureaus and offices should come from the Secretary of the Navy. In the actual working out of this method, we come down to what should be a practical plan of procedure. The Chief of Naval Operations through his meetings with the bureau chiefs will be able to carry through ninety-nine percent of the plan and actual work by unanimous agreement. This constitutes the “coordination” expected.

This did not resolve the problem. It was debated during hearings on the Vinson Bill in 1939 and the Edison Bill in 1940. The

14

Vinson Bill was directed toward the elimination of the Bureau System. It would have created 4 offices: (1) Office of the Secretary of the Navy; (2) Office of Naval Operations; (3) Office of Naval Material; and (4) Office of the Marine Corps. This was not passed by the Congress. The Edison Bill proposed the merger of Bureaus of Construction and Repair and Engineering with the Bureau of Ships. Additional changes were proposed. Retention of Bureaus was included, but also a coordination of all material matters through a Director of Shore Establishments. He would function and have the same authority for logistic matters as the CNO has for operations. Only the merger of the two Bureaus became effective.

The Bureau of the Budget was established in 1921 by the Congress in the Office of the Secretary of the Navy. The Navy Department Budget Officer reported directly to him. Bureaus had to justify new estimates to the Navy Department Budget Office before he presented them to SecNav. He also acted as SecNav’s representative in presenting them to the Bureau of the Budget and the committees of Congress.

The Bureau of Aeronautics, “which shall be charged with matters pertaining to naval aeronautics as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Navy,” was established in July 1921 by an Act of Congress. Between 1910 and when the Navy first began to take an active interest in naval aviation and 1921, the design production and operation of aircraft was handled in much the same manner as ships. The first Assistant Secretary for Aeronautics was authorized on 24 June 1926.

By General Order #68 of 6 September 1921, A Navy Yard Division was established in the office of the Assistant Secretary of the Navy. In 1940 the Bureaus of Construction and Repair, and Engineering were merged into the Bureau of Ships. On 18 December 1941, Executive Order #8984 assigned certain duties to the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and directed that subject thereto the duties of the two offices. The Board did so on 9 February 1942, and that recommendation was the basis of procedures followed by the two offices during the war.

The duties and responsibilities, respectively, of the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and of the Chief of Naval Operations, in this combination, were stated in the following terms in the Executive Order:

As Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, the officer holding the combined offices as herein provided shall have supreme command of the operating forces comprising the several fleets, seagoing forces, and sea frontier forces of the United States Navy and shall be directly responsible under the general direction of the Secretary of the Navy, to the President therefor.

15

As Chief of Naval Operations, the officer holding the combined offices as herein provided shall be charges, under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, with the preparation, readiness, and logistic support of the operation forces comprising the several fleets, seagoing forces and sea frontier forces of the United States Navy, and with the coordination and direction of effort to this end of the bureaus and offices of the Navy Department except such offices (other than bureaus) as the Secretary of the Navy may specifically exempt. Duties as Chief of Naval Operations shall be contributory to the discharge of the paramount duties of Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.

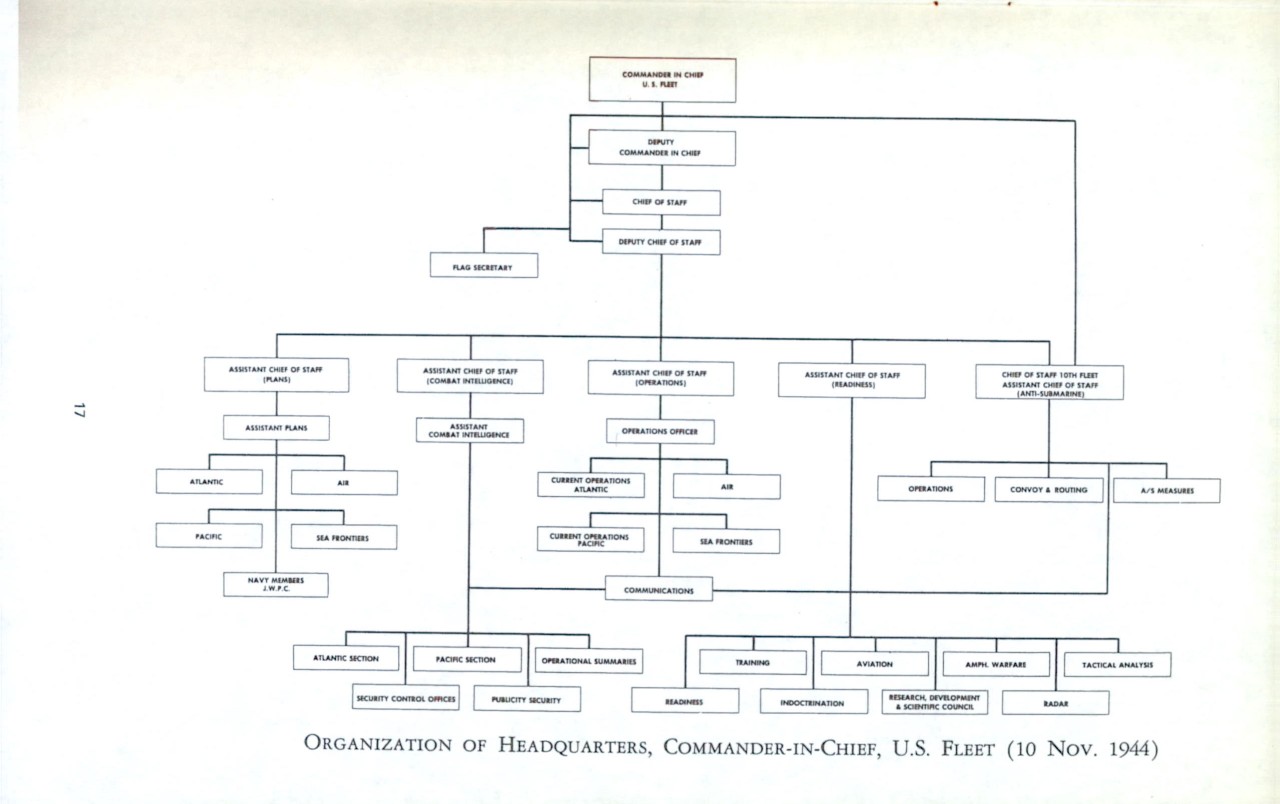

In this single paragraph the Chief of Naval Operations was given the legal authority he had been seeking since the office was created in 1915. This organization prevailed throughout World War II with the numerical staff as shown herewith:

| 1/1/42 | 10/1/45 | |

| Officers: | ||

| Men | 10 | 213 |

| Women | 0 | 58 |

| Enlisted: | ||

| Men | 9 | 82 |

| Women | 0 | 211 |

| Total: | 19 | 564 |

The details of the necessary wartime administrative changes and augmentations are not included in this paper. Suffice it to say that no really basic changes were made in the Bureau System organization.

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Admiral King took steps to return to the Chief of Naval Operations the functions taken over from that office. He proposed an organization consisting of the Chief of Naval Operations, assisted by a Vice Chief and five Deputy Chiefs for Operations, Personnel, Administration, Logistics, and Air, plus an Inspector General. The Secretary of the Navy approved this in general but would not agree to the contention of the wording of Executive Order 9096 giving the CNO direct access to the President, bypassing the Secretary of the Navy in the process.

All this eventuated in the issuance of Executive Order 9635 of 29 September 1945 entitled, “Organization of the Navy Department and the Naval Establishment.” The first paragraph stated: “In

16

order to provide for the more effective integration of its activities, the Navy Department shall hereafter be organized to take cognizance of the major groupings of: military matters; general and administrative matters; business and related industrial matters.” Sub-paragraph 6b of the order states: “there shall be in the Navy Department, an office charges, as the Secretary of the Navy may direct, with the coordination of naval research, experimental test and development activities, and with such other related duties as may be appropriate.”

Immediately after the war, the Bureau Chiefs were downgraded to two-star rank, while the Deputy Chiefs of Naval Operations and the Chief of the Bureau of Personnel retained their three stars.

Nothing is more indicative of the expansion of naval administration than a comparison of personnel employed in the Navy Department at the height of the Civil War and World War II. Both lasted four years and the Navy played just as great a role in winning the former as the latter. In the Civil War 89 persons were employed in the Navy Department in Washington. This included the Secretary of the Navy, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Bureau Chiefs, naval officers in the Bureaus or directly under Secretary of the Navy, and civilian employees such as clerks, draftsmen, and messengers. The civilian personnel had grown from 39 in 1860 to 66 in 1865 and are included in the 89 people. The Navy had grown from 90 ships and 10,000 officers and men to more than 680 ships and 62,000 officers and men.

The Navy at the peak of World War II had 19,000 civilians and in excess of 13,000 officers and 19,000 enlisted personnel, totaling 51,500 in the Navy Department.

In the Civil War the ratio of personnel in the Navy Department to naval personnel in the field was 1:700; it declined to about 1:70 in World War II.

Unification, of course, brought changes in the set up in the naval establishment. The Bureau System, as such, prevailed for many post unification [sic] years.

Throughout its 120 years, the system has never been above criticism and attack both from within and without the Navy. The Bureaus normally held the purse strings. They did not always meet the concepts and ideas of the seagoing forces. There has been cognizance and prestige rivalry between the Bureaus. It can be said, however, that the flexibility, competence, and soundness of the Bureau System has successfully met the requirements of the Navy during five winning wars and the intervening years of peace and lean budgets.

After all, organization is simply a plan of administration to accomplish some definite end. It is not an end in itself. Pope said: “For forms of government let fools contest, whatere’s administered best, is best.”

18

APPENDIX 1

General Order NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 362. Washington, June 15, 1888.

The following circular, issued by the Secretary of the Treasury on the 11th instant, is published for the information and guidance of officers and others connected with the Navy Department, the Navy and the Marine Corps.

WILLIAM C. WHITNEY,

Secretary of the Navy.

--------------

TREASURY DEPARTMENT,

WASHINGTON, D.C., June 11, 1888.

On and after July 1, 1888, the numbering of the quarters of the year will be made by the fiscal year instead of the calendar year, as heretofore. After that date the quarters will be as follows:

First quarter, July 1 to September 30.

Second quarter, October 1 to December 31.

Third quarter, January 1 to March 31.

Fourth quarter, April 1 to June 30.

In the indication of accounts and vouchers, the preparation of warrants and departmental blanks, the payment of salaries, and all other business of the Department in which it may be necessary to divide or make mention of the quarters, the foregoing direction will be observed.

C. S. FAIRCHILD,

Secretary.

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 374. WASHINGTON, July 26, 1889.

In order to insure uniformity, the following routine will be observed at morning and evening colors on board of all men-of-war in commission, and at all Naval Stations:

When a band is present it will play--

At morning colors : "The Star Spangled[sic] Banner."

At evening colors : "Hail Columbia."

All persons present, belonging to the Navy; not so employed as to render it impracticable, will face toward the colors and salute as the ensign reaches the peak or truck in hoisting, or the taffrail or ground in hauling down.

B. F. TRACY,

Secretary of the Navy.

19

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 98. Washington, D.C., May 18, 1914.

ORDERS GOVERNING THE MOVEMENTS OF THE RUDDER. (98)

1. This order supersedes General Order No. 30, of May 5, 1913, which should be marked "Canceled' across its face.

2. The term " helm" shall not be used in any command or directions connected with the operation of the rudder; in lieu thereof the term "rudder" shall be use--standard rudder, half rudder, etc.

3. The commands "starboard" and "port" shall not be used as governing the movement of the rudder; in lieu thereof the word "right" shall be employed when the wheel (or lever) and rudder are to be moved to the right to turn the ship's head to the right (with headway on), and "left" to turn the ship's head to the eft (with headway on). Instructions in regard to the rudder angle dhall be given to the steersman in such terms as "handsomely," "ten degrees rudder," "half rudder," "standard rudder," "full rudder," etc ; so tha a complete order would be "riht--standard rudder," "left--handsomely," etc. The steersman should afterwards be informed of the new course by such terms as "course--1350 ."

JOSEPHUS DANIELS,

Secretary of the Navy.

------------------

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No.99. Washington, D. C., June 1, 1914.

CHANGE IN ARTICLE 827, NAVAL INSTRUCTIONS. (99)

On July 1, 1914, Articke 827, Naval Instructions, will be annulled and in its stead the following will be substituted:

"The use or introducton for drinking purposs of alcoholic liquors on board any naval vessel, or within any navy yard or station, is strictly prohibited, and commanding officers will be held directly responsible for the enforcement of this order."

JOSEPHUS DANIELS,

Secretary of the Navy.

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 236. Washington, D. C., September 29, 1916.

CHANGE IN SCALE OF MARKS FOR ENLISTED MEN.

1. On and after January 1, 1917, marks assigned enlisted men of the Navy shall e based on a scale of 4 to 0 instead of 5 to 0.

2. The specific marks required to be attained by enlisted men for certain purposes in the Navy Regulations and other instructions will be considered as changed accordingly.

3. The marks of all enlisted men on Decemer 31, 1916, will be averaged the same as upon the discharge of a man, and the averages so attained will be converted into the equivalent figures under the new scale.

4. A red link line should be drawn across the page of the service record where the division occurs with the notation: "Equivalent average marks under scale of 4 to 0."

5. Marks under the scale of 4 to 0 of or above 2.50 shall be considered satisfactory; all marks below 2.50 shall be considered unsatisfactory.

W. S. BENSON,

Acting Secretary of the Navy.

20

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 353. Washington, D. C., December 10, 1917.

NAMES OF BATTLE CRUISERS NOS. 1 TO 5.

1. That part of General Order No. 334 which assigns names to battle cruisers Nos. 1 to 5 is hereby canceled, and those vessels are assigned names as follows:

No. 1--Lexington.

No. 2--Constellation.

No. 3--Saratoga.

No. 4--Ranger.

No. 5--Constitution.

JOSEPHUS DANIELS,

Secretary of the Navy.

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No.17. Washington, D. C., 5 January, 1921.

During the present emergency, it is prohibited for any person in the naval service to purchase or accept intoxicating liquor from bootleggers within the proscribed[sic] zones, or to have intoxicating liquor in his possession on board any naval vessel, or at any naval sation, or at any other place under he exclusive jurisdiction of the Navy Department, except as authorized for medical and religious purposes.

JOSEPHUS DANIELS,

Secretary odf the Navy.

NOTE.--This order is identical with General Order No. 410 of August 2, 1918.

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 55 Washington, 30 June, 1921.

1. The naval bill for the coming year carries very much reduced appropriations from those of last year. The country rightly demands economy.

2. Proper economy is not possible without the fullest cooperation of all in the Naval Establishment. It is care in small things that makes up the sum total of real savings. The enlisted man or workman who needlessly destroys a tool or throws away a box of nails is equally guilty with the admiral or high official who causes an unnecessary ship to be constructed.

3. All such are working against the desires of the country and the interests of the Navy. Every penny so wasted is taken away from the funds necessary to keep a proper national defense. All should realize their responsibility in this matter.

4. The department directs that all shall bear this question constantly in mind and govern their actions accordingly. Every effort will be made to see that this order is carried out in letter and in spirit.

5. This order shall be published at general muster aboard all vessels of the Navy and posted on all bulletin boards at navy yards and naval stations.

EDWIN DENBY,

Secretary of the Navy.

21

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 178 Washington, July 17, 1928.

INFORMATION REGARDING AIRPLANES OR ENGINES

1. The following policy by the Secretary of War on May 12, 1928, and by the Secretary of he Navy on May 22, 1928, is published for information and guidance :

'That no information on the characteristics or performance of any airplane produced soley for the War or Navy Departments be published, given out to the press, magazines, or to the public in any for by any person until such airplane or engine has been adopted as standard service equipment for at least one year, or until such airplane or engine is rejected as standard service equipment by the departmental interested."

2. In accordance with this poicy, no information in regard to airplanes or engines will be given out by any person under the Navy Departmnt until divulging such information shall have been approved by the Secretary of the Navy upon the recommendation of the Bureau of Aeronautics.

CURTIS D. WILBUR.

GENERAL ORDER NAVY DEPARTMENT,

No. 215 Washington, D. C., March 5, 1931.

USE OF HOLYSTONES TO CLEAN WOODEN DECKS

1. The use of holystones for cleaning for the wooden decks of naval vessels wears down the decks so rapidly that their repair or replacement has become an item of expense to the Navy Department which can not be met under limited appropriations.

2. The wooden decks of the new 10,000-ton light cruisers are so light that they may be made unserviceable very rapidly by the use of holystones.

3. It is therefore directed that the use of holystones or similar material for cleaning wooden decks be restricted to the removal of stains.

4. Wooden decks will usually be cleaned with brushes and sand or by such other means as will not caue excesive wear.

C. F. ADAMS,

Secretary of the Navy.

22

APPENDIX 2

EXECUTIVE ORDER

No. 9635

ORGANIZATION OF THE NAVY DEPARTMENT

AND THE NAVAL ESTABLISHMENT

By virtue of the authority vested in me by Title I of the First War Powers Act (55 Stat. 838; 50 U.S. Code 601, Supp. IV), and the other applicable statues, as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, and as President of the United States, it is hereby ordered as follows:

1. In order to provide for the more effective integration of its activities, the Navy Department shall hereafter be organized to take cognizance of the major groupings of: military matters; general and administrative matters; business and related industrial matters. The structure of the organization to accomplish this purpose shall be such as the Secretary of the Navy may deem appropriate and necessary, with due regard for the necessity for delegation and decentralization.

2. The Secretary of the Navy shall prescribe such duties for the Under Secretary of the Navy and the Assistant Secretaries of the Navy, and may transfer to, from, and among the officers and bureaus of the Navy Department such of their functions and duties, as may be appropriate and necessary to effectuate the provisions of this order.

3. As used in this order, the term “naval establishment” means sea, air and ground forces—vessels of war, aircraft, auxiliary craft and auxiliary activities, and the personnel who man them—and the naval agencies necessary to support and maintain the naval forces and to administer the Navy as a whole; the term “Navy Department” means the executive part of the naval establishment at the seat of the Government.

The Marine Corps is an integral part of the naval establishment. In time of war or when the President shall so direct, the Coast Guard is a part of the naval establishment.

4. The Chief of Naval Operations

(a) shall be the principal adviser to the President and to the Secretary of the Navy on the conduct of war, and principal naval adviser and military executive to the Secretary of the Navy on the conduct of the activities of the naval establishment.

(b) shall have command of the operating forces comprising the several fleets, seagoing forces, sea frontier forces, district and other forces, and the related shore establishments of the Navy, and shall be responsible to the Secretary of the Navy for their

23

use in war and for plans and preparations for their readiness for war.

c. shall be charged, under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, with the preparation, readiness and logistic support of the operating forces, comprising the several fleets, seagoing forces, sea frontier forces, district and other forces, and related shore establishments of the Navy, and with the coordination and direction of effort to this end of the bureaus and offices of the Navy Department.

5. The staff of the Chief of Naval Operations shall be composed of such numbers of Vice Chiefs of Naval Operations, Deputy Chiefs of Naval Operations, Assistant Chiefs of Naval Operations, a Naval Inspector General, and other officers as may be considered by the Secretary of the Navy to be appropriate and necessary for the performance of the duties herein prescribed for the Chief of Naval Operations.

6. There shall be in the Navy Department

a. An office charged with coordination and correlation of the activities of bureaus and offices, as the Secretary of the Navy may direct, to effectuate common policies of procurement, contracting and production of material throughout the naval establishment.

b. An office charged, as the Secretary of the Navy may direct, with the coordination of naval research, experimental, test and development activities and with such other related duties as may be appropriate.

7. The bureaus and offices of the Navy Department, in addition to the Chiefs of such bureaus and offices, shall be staffed by such officers, including a Deputy and one or more Assistant Chiefs, as may be determined to be appropriate and necessary by the Secretary of the Navy.

8. During the temporary absence of the Secretary of the Navy, the Under Secretary of the Navy, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air, and the Chief of Naval Operations, in that order, shall be next in succession to act as the Secretary of the Navy. In the absence of the Chief of Naval Operations, the Vice and Deputy Chiefs of Naval Operations shall be next in succession in accordance with relative rank.

9. Nothing in this order is intended to modify the statutory authority, duties, or responsibilities of the Secretary of the Navy, nor shall it be so construed.

10. Executive Order 8984 of December 18, 1941 and 9096 of March 12, 1942 (as amended by Executive Order 9528 of March 2, 1945), are hereby revoked.

HARRY S. TRUMAN

THE WHITE HOUSE,

September 29, 1945

24

APPENDIX 3

Adm. E. J. King’s philosophy of Command

“CINCLANT SERIAL (053) OF JANUARY 21, 1941

Subject: Exercise of Command—Excess of Detail in Orders and Instructions

1. I have been concerned for many years over the increasing tendency now grown almost to “standard practice”—of flag officers and other group commanders to issue orders and instructions in which their subordinated are told “how” as well as “what” to do to such an extent and in such detail that the “Custom of the service” has virtually become the antithesis of that essential element of command—“initiative of the subordinate.”

2. We are preparing for—and are now close to— those active operations (commonly called war) which require the exercise and the utilization of the full powers and capabilities of every officer in command status. There will be neither time nor opportunity to do more than prescribe the several tasks of the several subordinates (to say “what”, perhaps “when” and “where”, and usually, for their intelligent cooperation, “why”); leaving to them—expecting and requiring of them—the capacity to perform the assigned tasks (to do the “how”).

3. If subordinates are deprived—as they now are—of that training and experience which will enable them to act “on their own”—if they do now know, by constant practice, how to exercise “initiative of the subordinate”—if they are reluctant (afraid) to act because they are accustomed to detailed orders and instructions—if they are not habituated to think, to judge, to decide and to act for themselves in their several echelons of command—we shall be in sorry case when the time of “active operations” arrives.

4. The reasons for the current state of affairs—how did we get this way?—are many but among them are four which need mention; first, the “anxiety” of seniors that everything in their commands shall be conducted so correctly and go so smoothly, that none may comment unfavorably; second, those energetic activities of staffs which lead to infringement of (not to say interference with) the functions for which the lower echelons exist; third, the consequent “anxiety” of subordinates lest their exercise of initiative, even in their legitimate spheres, should result in their doing something which may prejudice their selection for promotion; fourth, the habit on the one hand and the expectation on the other of “nursing”

25

5. Let us consider certain facts; first, submarines operating submerged are constantly confronted with situations requiring the correct exercise of judgement, decision and action; second, planes, whether operating singly or in company, are even more often called upon to act correctly; third, surface ships entering or leaving port, making a landfall, steaming in thick weather, etc., can and do meet such situations while “acting singly” and, as well, the problems involved in maneuvering in formations and dispositions. Yet these same people—proven competent to do these things without benefit of “advice” from higher up—are, when grown in years and experience to be echelon commanders, all too often not made full use of in conducting the affairs (administrative and operative) of their several echelons—echelons which exist for the purpose of facilitating command.

6. It is essential to extend the knowledge and the practice of “initiative of the subordinate” in principle and in application until they are universal in the exercise of command throughout all the echelons of command. Henceforth, we must all see to it that full use is made of the echelons of command—whether administrative (type) or operative (task)—by habitually framing orders and instructions to echelon commanders so as to tell them ‘what to do’ but not ‘how to do it’ unless the particular circumstances so demand.

7. The corollaries of paragraph 6 are:

a. adopt the premise that the echelon commanders are competent in their several command echelons unless and until they themselves prove otherwise;

b. teach them that they are not only expected to be competent for their several command echelons but that it is required of them that they be competent;

c. train them—by guidance and supervision—to exercise foresight, to think, to judge, to decide and to act for themselves;

d. stop ‘nursing’ them;

e. finally, train ourselves to be satisfied with ‘acceptable solutions’ even though they are not ‘staff solutions’ or other particular solutions that we ourselves prefer.”

26