The Navy Department Library

Narrative of the United States' Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea

by W. F. Lynch, U.S.N.,

Commander of the Expedition

1849

Selected chapters available online:

Chapter 1: Introduction

List of the Members of the Expedition

Chapter 8: From the Sea of Galilee to the Falls of Buk'ah.--Departure of the Boats April 1848)

Chapter 18: From the Outlet of the Hot Springs of Callirohoe to Ain Turâbeh (5-9 May 1848)

Chapter 19: From the Dead Sea to the Convent of Mar Saba (10-14 May 1848)

Chapter 20: From Mar Saba to Jerusalem (15-16 May 1848)

Chapter 21: Jerusalem (17-22 May 1848)

Expedition to the Dead Sea.

Chapter I. Introductory

On the 8th of May, 1847, the town and castle of Vera Cruz having some time before surrendered, and there being nothing left for the Navy to perform, I preferred an application to the Hon. John Y. Mason, the head of the department, for permission to circumnavigate and thoroughly explore the Lake Asphaltites or Dead Sea.

My application having been for some time under consideration, I received notice, on the 31st of July, of a favourable decision, with an order to commence the necessary preparations.

On the 2d of October, I received an order to take command of the U.S. store-ship Supply, formerly called the Crusader.

In the mean time, while the ship was being prepared for her legitimate duty of supplying the squadron with stores, I had, by special authority, two metallic boats, a copper and a galvanized iron one, constructed, and shipped ten seamen for their crews. I was very particular in selecting young, muscular, native-born Americans, of sober habits, from each of whom I exacted a pledge to abstain from all intoxicating drinks. To this stipulation, under Providence, is principally to be ascribed their final recovery from the extreme prostration consequent on the severe privations and great exposure to which they were unavoidably subjected.

Two officers, Lieutenant J.B. Dale and Passed Midshipman R. Aulick, both excellent draughtsmen, were detailed to assist me in the projected enterprise.

In November I received orders to proceed to Smyrna, as soon as the ship should in all respects be ready for sea; and, through Mr. Carr, U.S. Resident Minister at Constantinople, apply to the Turkish government for permission to pass through a part of its dominions in Syria, for the purpose of exploring the Dead Sea, and tracing the river Jordan to its source.

I was then directed, if the firman were granted, to relinquish the ship to the first lieutenant, and land with the little party under my command on the coast of Syria. The ship was thence to proceed to deliver stores to the squadron, and Commodore Read was instructed to send her back in time for our re-embarking.

In the event of the firman being refused, I was directed to rejoin the squadron without proceeding to the coast of Syria.

The ship was long delayed for the stores necessary to complete her cargo. The time was, however, fully occupied in collecting materials and procuring information. One of the men engaged was a mechanic, whose skill would be necessary in taking apart and putting together the boats, which were made in sections. I also had him instructed in blasting rocks, should such a process become necessary to ensure the transportation of the boats across the mountain ridges of Galilee and Judea.

Air-tight gum-elastic water bags were also procured, to be inflated when empty, for the purpose of serving as life-preservers to the crews in the event of the destruction of the boats.

Our arms consisted of a blunderbuss, fourteen carbines with long bayonets, and fourteen pistols, four revolving and ten with bowie-knife blades attached. Each officer carried his sword, and all, officers and men, were provided with ammunition belts.

As taking the boats apart would be a novel experiment, which might prove unsuccessful, I had two low trucks (or carriages without bodies) made, for the purpose of endeavouring to transport the boats entire from the Mediterranean to the Sea of Galilee. The trucks, when fitted, were taken apart and compactly stowed in the hold, together with two sets of harness for draught horses. The boats, when complete, were hoisted in, and laid keel up on a frame prepared for them; and with arms, ammunition, instruments, tents, flags, sails, oars, preserved meats, and a few cooking utensils, our preparations were complete.

W.F. Lynch, Lieutenant-Commanding.

John B. Dale, Lieutenant.

R. Aulick, Passed-Midshipman.

Francis E. Lynch, Charge of Herbarium.

Joseph C. Thomas, Master's Mate.

George Overstock, Seaman.

Francis Williams, Seaman.

Charles Homer, Seaman.

Hugh Read, Seaman.

John Robinson, Seaman.

Gilbert Lee, Seaman.

George Lockwood, Seaman.

Charles Albertson, Seaman.

Henry Loveland, Seaman.

Henry Bedlow, Esq., and Henry J. Anderson, M.D., were associated with the Expedition as volunteers, after its original organization,--the first at Constantinople, and the other at Beïrût. More zealous, efficient, and honourable associates could not have been desired. They were ever in the right place, bearing their full share of watching and privation. To the skill of Mr. Bedlow, the wounded seaman was indebted for the preservation of his life; and words are inadequate to express how in sickness, forgetful of himself, he devoted all his efforts to the relief of his sick companions.

Chapter VIII. From the Sea of Galilee to the Falls of Buk'ah.--Departure of the Boats.

Bright was the day, gay our spirits, verdant the hills, and unruffled the lake, when, pushing off from the shelving beach, we bade adieu to the last outwork of border civilization, and steered direct for the outlet of the Jordan. The "Fanny Mason" led the way, followed closely by the "Fanny Skinner;" and the Arab boatmen of the "Uncle Sam" worked vigorously at the oars to keep their place in the line. With awnings spread and colours flying, we passed comfortably and rapidly onwards.

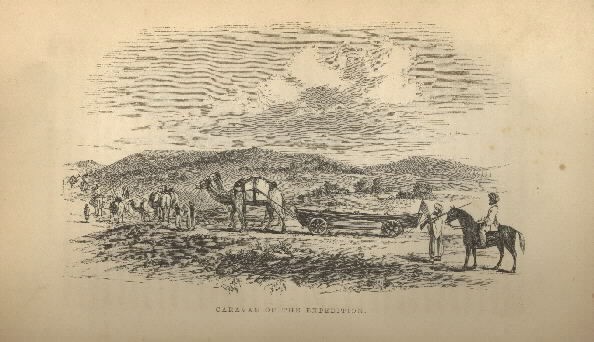

Our Bedawin friends had many of them exchanged their lances for more serviceable weapons, long-barrelled guns and heavily mounted pistols. 'Akil alone wore a scimetar. The priestly character of the Sherîf forbade him to carry arms. With the addition of Emir and his followers, they amounted in all to thirty horsemen. Passing along the shore in single file, their line was long and imposing. Eleven camels stalked solemnly ahead, followed by the wild Bedawin on their blooded animals, with their abas flying in the wind, and their long gun-barrels glittering in the sun; and Lieutenant Dale and his officers in the Frank costume brought up the rear.

Gallantly marched the cavalcade on the land, beautiful must have appeared the boats upon the water. Little did we know what difficulties we might have to encounter! But, placing our trust on high, we hoped and feared not.

We started at 2 P.M., the temperature of the air 82°, of the water 70°. For the first hour we steered S.E., then S.E by S., and E.S.E., when, at 3.40, we arrived at the outlet. The same feeling prevented us from cheering as when we launched the boats, although before us was the stream which, God willing, would lead us to our wondrous destination.

The lake narrowed as we approached its southern extremity. In its south-west angle are the ruins of ancient Tarrichaea; opposite, on the eastern shore, a lovely plain sweeps down to the lake, and on the centre of the waterline a ravine (wady) comes down. Due west from it, across the foot of the lake, the Jordan debouches shortly to the right. The right or western shore descends in a slope towards the lake; the left is somewhat more depressed, and much washed with rains.

The scenery, as we left the lake and advanced into the Ghor, which is about three-quarters of a mile in breadth, assumed rather a tame than a savage character. The rough and barren mountains, skirting the valley on each hand, stretched far away in the distance, like walls to some gigantic fosse, their southern extremities half hidden or entirely lost in a faint purple mist.

At 3.45, we swept out of the lake; course, W. by N. The village of Semakh on a hill to the south, and Mount Hermon brought into view, bearing N.E. by N.; the snow deep upon its crest, and white parasitic clouds clinging to its sides. On the extreme low point to the right are the ruins, called by the Arabs, Es Sumra, only a stone foundation standing. A number of wild ducks were upon the water, and birds were flitting about on shore. 3.55, our cavalcade again appeared in sight, winding along the shore. The Bedawin looked finely in their dark and white and crimson costumes.

At 4.30, course W.S.W. abruptly round a ledge of small rocks; current, two knots. Our course varied with the frequent turns of the river, from N.W. by W. at 4.35, to S. at 4.38. The average breadth about seventy-five feet; the banks rounded and about thirty feet high, luxuriantly clothed with grass and flowers. The scarlet anemone, the yellow marigold, and occasionally a water-lily, and here and there a straggling asphodel, close to the water's edge, but not a tree nor a shrub.

At 4.43, we passed an inlet, or bay, wider than the river, called El Mûh, which extended north a quarter of a mile. We lost sight of the lake in five minutes after leaving it. At 4.45, heard a shot from the shore, and soon after saw one of our scouts; 4.46, passed a low island, ninety yards long, tufted with shrubbery; left bank abrupt, twenty-five feet high; a low, marshy island, off a point on the right, which runs out from the plain at the foot of the mountains. Water clear and ten feet deep. 4.55, saw the shore party dismounted on the right bank. Mount Hermon glittering to the north, over the level tract which sweeps between the mountain, the lake, and the river.

When the current was strong, we only used the oars to keep in the channel, and floated gently down the stream, frightening, in our descent, a number of wild fowl feeding in the marsh grass and on the reedy islands. At 4.56, current increasing, swept round a bend of the shore, and heard the hoarse sound of a rapid. 4.57, came in sight of the partly whole and partly crumbled abutments of "Jisr Semakh," the bridge of Semakh.

The ruins are extremely picturesque; the abutments standing in various stages of decay, and the fallen fragments obstructing the course of the river; save at one point, towards the left bank, where the pent-up water finds an issue, and runs in a sluice among the scattering masses of stone.

From the disheartening account we had received of the river, I had come to the conclusion that it might be necessary to sacrifice one of the boats to preserve the rest. I therefore decided to take the lead in the"Fanny Mason;" for, being made of copper, quite serious damages to her could be more easily repaired; and if dashed to pieces, her fragments would serve to warn the others from the danger.

After reconnoitering the rapid, at 5.05, we shot down the sluice. The following note was made on shore:

"We halted at the ruins of an old bridge, now forming obstructions, over which the foaming river rushed like a mountain torrent. The river was about thirty yards wide. Soon after we halted, the boats hove in sight around a bend of the river. See! the Fanny Mason attempts to shoot between two old piers! she strikes upon a rock! she broaches to! she is in imminent danger! down comes the Uncle Sam upon her! now they are free! the Fanny Skinner follows safely, and all are moored in the cave below!"

As we came through the rapids, 'Akil stood upon the summit of one of the abutments, in his green cloak, red tarbouch and boots, and flowing white trousers, pointing out the channel with a spear. Over his head and around him, a number of storks were flying disorderly.

What threatened to be its greatest danger, proved the preservation of the leading boat. We had swept upon a rock in mid-channel, when the Arab crew of the Uncle Sam unskilfully brought her within the influence of the current. She was immediately borne down upon us with great velocity; but striking us at a favourable angle, we slided off the ledge of rock, and floated down together. The Fanny Skinner, drawing less water, barely touched in passing.

The boats were securely moored for the night in a little cave on the right bank, and were almost hidden among the tall grass and weeds which break the force of the eddy current.

From a boat drawing only eight inches water striking in mid-channel at this time of flood, I was inclined to think that the river must be very shallow in the summer months, particularly if much snow has not fallen among the mountains during the preceding winter.

We found the tents pitched on a small knoll, commanding a fine view of the river and the bridge. Over the ruins of the latter were yet hovering a multitude of storks, frightened from their reedy nests, on the tops of the ruined abutments, by the strange sights and sounds. There were two entire and six partial abutments, and the ruins of another, on each shore. The snowy crest of Mount Hermon bore N.E. 1/2N. The village of Semakh, lying in an E.N.E. direction, was concealed by an intervening ridge.

Our course, since leaving the lake, has varied from south to N.W by N.,--the general inclination has been west; river, twenty-five to thirty yards wide; current, two and a half knots; water clear and sweet. We passed two islands, one of them very small.

We were upon the edge of the Ghor. A little to the north, the Ardh el Hamma (the land of the bath) swept down from the left. The lake was concealed, although, in a direct line, quite near; and a lofty ridge overlooked us from the west. The soil here is a dark rich loam, luxuriantly clothed three feet deep with flowers,--the purple bloom of the thistle predominates, and the yellow of the marigold and pink oleander are occasionally relieved by the scarlet anemone. The rocks nowhere crop-out, but large boulders of sandstone and trap are scattered over the surface. Some flowers were gathered here, which equal any I have ever seen in delicacy of form and tint. Among them, besides those I have named, were the Adonis or Pheasant's eye; the Briony, formerly used in medicine; the Scabiosa Stellata, in great luxuriance, and which is cultivated at home; and two kinds of clover,--one with a thorny head, which we have never seen before, and the other small but beautiful, with purple flowers.

From the eminence above, our encampment beside the rapids looked charming. There were two American, one Arab, and one Egyptian (Dr. Anderson's) tents, of different colours,--white and green, and blue and crimson. In the soft and mellow light of the moon, the scene was beautiful.

On this side is the land of Zebulon; that of the tribe of Gad lies upon the other.

The sheikh of Semakh holds a tract of land on a singular tenure. The condition is that he shall entertain all travellers who may call, with a supper, and barley for their horses. Our Bedawin determined to avail themselves of the privilege. Nothing could be more picturesque than their appearance as they forded the stream in single file, and galloped over the hill to Semakh. And what a supper they will have! A whole sheep, and buckets of rice!1

Our friends returned late at night, splashing the water, shouting, and making such a clatter that we sprang to our arms expecting an attack. Repeatedly afterwards during the night we were disturbed by Dr. Anderson's horse, which, since the moment he joined us at Turân, had kept the camp in constant alarm, getting loose at night and rushing franticly over the tent-cords, attacking some slumbering Arab steed, his bitter enemy.

Tuesday, April 11. Very early this morning culled for our collection two varieties of flowers we had not before seen. At 6 A.M., called all hands, and prepared for starting. To avoid stopping in the middle of the day, we were necessarily delayed for breakfast in the morning.

8.10 A.M., started, the boats down the river, the caravan by land. The current at first about 21/2 knots, but increasing as we descended, until at 8.20 we came to where the river, for more than three hundred yards, was one foaming rapid; the fishing-weirs and the ruins of another ancient bridge obstructing the passage. There were cultivated fields on both sides. Took everything out of the boats, sent the men overboard to swim alongside and guide them, and shot them successively down the first rapid. The water was fortunately very deep to the first fall, where it precipitated itself over a ledge of rocks. The river becoming more shallow, we opened a channel by removing large stones, and as the current was not excessively rapid, we pulled well out into the stream, bows up, let go a grapnel and eased each boat down in succession. Below us were yet five successive falls, about eighteen feet in all, with rapids between,--a perfect breakdown in the bed of the river. It was very evident that the boats could not descend them.

On the right of the river, opposite to the point where the weirs and the ruined bridge blocked up the bed of the stream, was a canal or sluice, evidently made for the purpose of feeding a mill, the ruins of which were visible a short distance below. This canal, at its outlet from the river, was sufficiently broad and deep to admit of the boats entering and proceeding for a short distance, when it became too narrow to allow their further progress.

Bringing the boats thus far, we again took everything out of them, and cleared away the stones, bushes and other obstructions between the mill sluice and the river. A breach was then made in the bank of the sluice, and as the water rushed down the shallow artificial channel, with infinite labour, our men, cheerfully assisted by a number of Arabs, bore them down the rocky slope and launched them in the bed of the river,--but not below all danger, for a sudden descent of six or seven feet was yet to be cleared, and some eighty yards of swift and shallow current to be passed before reaching an unobstructed channel.

1 P.M. We accomplished this difficult passage, after severe labour, up to our waists in the water for upwards of four hours. Hauled to the right bank to rest and wait for our arms, instruments, &c. We were surrounded by many strange Arabs, and had stationed one of our men by the blunderbuss on the bows of the Uncle Sam, and one each by the other boats, while the remainder proceeded to bring down the arms.

We lay just above an abrupt bend from S. to N.E. by E. The left bank, in the bend, is sixty feet high, and precipitous, of a chocolate and cream-coloured earth. The river continues to descend, lessened in rapidity, but still about five knots per hour. It breaks entirely across, just below. There were thick clusters of white and pink oleander in bloom along the banks, and some lily-plants which had passed their season and were fading away. Here we killed an animal having the form of a lobster, the head of a mouse, and the tail of a dog; the Arabs call it kelb el maya, or water-dog.

1.20 P.M., started again. 1.45, descended a cascade at a angle of 30°, at the rate of twelve knots, passing, immediately after, down a shoal rapid, where we struck and hung, for a few moments, upon a rock. Stopped for the other boats, which were behind. The course of the river had been very circuitous, as reference to the chart will show.

At 2.05, saw some of our caravan on a hill, in the distance. Wet and wary, I walked along the difficult shore to look for the other boats, when, seeing a cluster of Bedawin spears on the bank above, I went up to see to whom they belonged. It was a party of nine strange Arabs, who were seated upon the grass, their horses tethered near them. They examined my watch-guard and uniform buttons very closely; and eagerly looked over my shoulder, uttering many exclamations, when I wrote in my note-book. They repeatedly asked for something which I could not understand, and as they began to be importunate, I left them. Shortly after, while walking further up, I came upon their low, black, camel's hair tent, almost concealed by a thicket of rank shrubbery.

At 2.40, came to two mills, the buildings entire, but the wheels and machinery gone, with a sluice which had formerly supplied them with water. As in the morning, we turned the water from the upper part of the sluice into the river, carried the boats along, and dragged them safely round these second series of rapids.

The soil is fertile, but the country about here is wholly uncultivated. The surface of the plain is about fifteen feet above the river, thence gradually ascending a short distance to a low range of hills; beyond which, on each side, the prospect is closed in by mountains.

At 4.45, stopped to rest, after descending the eleventh rapid we had encountered. The velocity of the current was so great that one of the seamen, who lost his hold (being obliged to cling on outside), was nearly swept over the fall, and, with very great difficulty, gained the shore. The mountains on the east coast of Lake Tiberias were visible over the left bank. The summit of Mount Hermon (the snowy summit could alone be seen) bore N.E. by N.

At 5 P.M., passed a ravine (wady) on the left, in a bend between high, precipitous banks of earth. We here saw canes for the first time, growing thickly. On the right are lofty, perpendicular banks of earth and clay. The river winding with many turns, we opened, at 5.04, an extensive uncultivated plain on the right; a small, transverse, cultivated valley, between high banks, on the left;--the wheat beginning to head. The river fifty-five yards wide and two and a half feet deep. Current, four knots; the water becoming muddy. We saw a partridge, an owl, a large hawk, some herons (hedda), and many storks, and caught a trout.

At 5.10, rounded a high, bold bluff, the river becoming wider and deeper, with gravelly bottom. A solitary carob tree, resembling a large apple tree, on the right. At 5.40, the river about sixty yards wide, and current three knots, passed the village of 'Abeidîyeh, a large collection of mud huts, on a commanding eminence on the right;--the people, men, women, and children, with discordant cries, hurrying down the hill towards the river when they saw us. It was too late to stop, for night was approaching, and we had seen nothing of the caravan since we parted with them, at the ruined bridge, this forenoon.

If the inhabitants intended to molest us, we swept by with too much rapidity for them to carry their designs into execution. 5.44, passed a small stream coming in on the right. 5.46, another small stream, same side, 150 yard below the first; some swallows and snipes flying about. 5.48, passed a bank of fullers' earth, twenty feet high, on the left; a beautiful bank on the right, clothed with luxuriant verdure; the rank grass here and there separated by patches of wild oats.

The mountain ranges forming the edges of the upper valley, as seen from time to time through gaps in the foliage of the river banks, were of a light brown colour, surmounted with white.

The water now became clearer,--was eight feet deep; hard bottom; small trees in thickets under the banks, and advancing into the water--principally Turfa (tamarisk), the willow (Sifsaf), and tangled vines beneath.

We frequently saw fish in the transparent water; while ducks, storks, and a multitude of other birds, rose from the reeds and osiers, or plunged into the thickets of oleander and tamarisk which fringe the banks,--beyond them are frequent groves of the wild pistachio.

Half a mile below 'Abeidîyeh the river became deeper, with a gentle descent,--current, three and a half knots. 6.15, passed a small island covered with grass: started up a flock of ducks and some storks; a small bay on the left, a path leading down to it from over the hills; canes and coarse tufted grass on the shores. 6.19, another inlet on the left; 6.21, one on the right. The left shore quite marshy,--high land back; the water again became clear, and of a light green colour, as when it left the lake; many birds flying about, particularly swallows.

At 8 P.M. reached the head of the falls and whirlpool of Buk'ah; and finding it too dark to proceed, hauled the boats to the right bank, and clambered up the steep hill to search for the camp. About one-third up, encountered a deep dyke, cut in the flank of the hill, which had evidently been used for purposes of irrigation. After following it for some distance, succeeded in fording it, and going to the top of the hill, had to climb in the dark, through briars and over stone walls, the ruins of the village of Delhemîyeh. A short distance beyond, met a Bedawin with a horse, who had been sent to look for us. Learned from him that the camp was half a mile below the whirlpool, and abreast of the lower rapids. Sent word to Mr. Aulick to secure the boats, and bring the men up as soon as they were relived, and hastened on myself to procure the necessary guards, for our men were excessively fatigued, having been in the water without food since breakfast. A few moments after, I met 'Akil, also looking for us. At my request, he sent some of his men to relieve ours, in charge of the boats.

The village of Delhimîyeh, as well as that of Buk'ah opposite, were destroyed, it is said by the Bedawin, the wandering Arabs. Many of the villages on and near the river are inhabited by Egyptians, placed there by Ibrahim Pasha, to repress the incursions of the Bedawin--somewhat on our plan of the military occupation of Florida. Now that the strong arm of the Egyptian "bull-dog," as Stephens aptly terms him, is withdrawn, the fate of these villages is not surprising. The Bedawin in their incursions rob the fellahin of their produce and their crops. Miserable and unarmed, the latter abandon their villages and seek a more secure position, or trust to chance to supply themselves with food (for of raiment they seem to have no need,) until the summer brings the harvest and the robber. Once abandoned, their huts fall into as much ruin as they are susceptible of, which is nothing more than the washing away of the roofs by the winter rains.

Although I knew it to be important to note everything we passed, and every aspect of the country, yet such was the acute responsibility I felt for the lives placed in my charge, that nearly all my faculties were absorbed in the management of the boats--hence the meagreness of these observations. As some amends, I quote from the notes of the land party.

"Our route lay through an extensive plain, luxuriant in vegetation, and presenting to view in uncultivated spots, a richness of alluvial soil, the produce of which, with proper agriculture, might nourish a vast population. On our route as we advanced, and within half an hour (distance is measured by time in this country) from the last halting-place, were four or five black tents, belonging to those tribes of Arabs called fellahin, or agriculturists, as distinguished from the wandering warrior Arab, who considers such labour as ignoble and unmanly.

"Enclosing these huts was a low fence of brush, which served to confine the gambols of eight or ten young naked barbarians, who, together with a few sheep and a calf, were enjoying a romp in the sunshine, disregarding the heat. We declined the invitation to alight, but accepted a bowl of camel's milk, which proved extremely refreshing.

"A miserable collection of mud huts upon a most commanding site, called 'Abeidîyeh, attracted our attention as we passed it. The wild and savage looking inhabitants rushed from their hovels and clambered up their dirt-heaps to see the gallant sight--the swarthy Bedawin, the pale Franks, and the laden camels. Still further on, we passed the ruins of two Arab villages, one on each side of the Jordan, and upon elevations of corresponding height, 'Delhemîlyeh' and 'Buk'ah.'

"Below these villages, and close upon the Jordan's bank, where the river in places foamed over its rocky bed with the fury of a cataract, we pitched the camp. Here we were to await the arrival of the boats. At 2.30 we encamped, and at 5 they had not yet arrived. The sun set and night closed upon us, and yet no signs of them. We became uneasy, and were about mounting to go in search of them, when the captain made his appearance."

About 9 P.M., Emir Nasser, with his suite, came to the tent. After the customary cup of coffee he said that he would go with us to Bahr Lut (Dead Sea), or wherever else I wished, from pure affection, but that his followers would expect to be paid, and requested to know how many I required; how far they were to go, and what remuneration to receive. I replied that I was then too weary to discuss the matter, but would tell him in the morning, and he retired. Either from exposure, or fatigue, or the effect of the water, one of the seamen was attacked with dysentery. I anxiously hoped that he would be better in the morning, for each one was now worth a host.

Our encampment was a romantic one. Above was the whirlpool; abreast, and winding below, glancing in the moonlight, was the silvery sheen of the river; and high up, on each side, were the ruined villages, whence the peaceful fellahin had been driven by the predatory robber. The whooping of the owl above, the song of the bulbul below, were drowned in the onward rush and deafening roar of the tumultuous waters.

We were now approaching the part of our route considered the most perilous, from the warlike character of the nomadic tribes it was probable we should encounter. It therefore behoved us to be vigilant;--and notwithstanding the land party had been nearly all day on horseback, and the boats' crews for a longer period in the water, the watches could not be dispensed with; and one officer and two men, for two hours at a time, kept guard around the camp, with the blunderbuss mounted for immediate use in front.

Every one lay down with his cartridge-belt on, and his arms beside him. It was the dearest wish of my heart to carry through this enterprise without bloodshed, or the loss of life; but we had to be prepared for the worst. Average width of river to-day, forty yards; depth from two and a half to six feet; descended nine rapids, three of them terrific ones. General course, E.S.E.; passed one island.

It was a bright moonlight night; the dew fell heavily, and the air was chilly. But neither the beauty of the night, the wild scene around, the bold hills, between which the river rushed and foamed, a cataract, nor moonlight upon the ruined villages, nor tents pitched upon the shore, watch-fires blazing, and the Arab bard singing sadly to the sound of his rebabeh,2 could, with all the spirit of romance, keep us long awake. With our hands upon our firelocks, we slept soundly; the crackle of the dry wood of the camp-fires, and the low sound of the Arab's song, mingling with our dreams; dreams, perchance, as pleasant as those of Jacob at Bethel; for, although our pillows were hard, and our beds the native earth, we were upon the brink of the sacred Jordan!

Chapter XVIII. From the Outlet of the Hot Springs of Callirohoe to Ain Turâbeh.

Friday, May 5. Rose at 2 A.M. Fresh wind from the north; air quite chilly, and the warmth of the fire agreeable. It was this contrast which made the heat of the day so very oppressive. Everything was still and quiet, save the wind, and the surf breaking upon the shore. I had purposed visiting the ruins of Machaerus, upon this singular hot-water stream, and to have excavated one of the ancient tombs mentioned in the itinerary of Irby and Mangles, the most unpretending, and one of the most accurate narrative I have ever read; but the increasing heat of the sun, and the lassitude of the party, warned me to lose no time.

In his description of the fortress of Machaerus, rebuilt by Herod, Josephus says, "It was also so contrived by nature that it could not be easily ascended; for it is, as it were, ditched about with such valleys on all sides, and to such a depth that the eye cannot reach their bottoms, and such as are not easily to be passed over, and even such as it is impossible to fill up with earth; for that valley which cuts it off on the west extends to threescore furlongs, and did not end till it came to the Lake Asphaltites; on the same side it was, also, that Machaerus had the tallest top of its hill elevated above the rest."

Speaking of the fountains, his words are, "Here are, also, fountains of hot water that flow out of this place, which have a very different taste one from the other; for some of them are bitter, and others of them are plainly sweet. Here are, also, many eruptions of cold waters; and this not only in the places that lie lower and have their fountains near one another, but what is still more wonderful, here is to be seen a certain cave hard by, whose cavity is not deep, but it is covered over by a rock that is prominent; above this rock there stand up two (hills or) breasts, as it were, but a little distant from one another, the one of which sends out a fountain that is very cold, and the other sends out one that is very hot; which waters, when they are mingled together, compose a most pleasant bath; they are medicinal, indeed, for other maladies, but especially good for strengthening the nerves. This place has in it, also mines of sulphur and alum."

At 2.45, called the cook to prepare our breakfast. At 3.40, called all hands, and having

"Broke our fast,

Like gentlemen of Beauce,"

started to sound across to Ain Turâbeh, thus making a straight line to intersect the diagonal one of yesterday. Two furlongs from the land, the soundings were twenty-three fathoms (138 feet). The next cast, five minutes after, 174 (1044 feet), gradually deepening to 218 fathoms (1308 feet); the bottom, soft, brown mud, with rectangular crystals of salt. At 8 A.M., met the Fanny Skinner. Put Mr. Aulick, with Dr. Anderson, in her; also the cook, and some provisions, and directed him to complete the topography of the Arabian shore, and determine the position of the mouth of the Jordan; and, as he crossed over, to sound again in an indicated stop. Made a series of experiments with the self-registering thermometer, on our way, in the Fanny Mason, to Ain Turâbeh. At the depth of 174 fathoms (1044 feet), the temperature of the water was 62°; at the surface, immediately above it, 76°. There was an interruption to the gradual decrease of temperature, and at ten fathoms there was a stratum of cold water, the temperature, 59°. With that exception, the diminution was gradual. The increase of temperature below ten fathoms may, perhaps, be attributable to heat being evolved in the process of crystalization. Procured some of the water brought up from 195 fathoms, and preserved it in a bottle. The morning intensely hot, not a breath of air stirring, and a mist over the surface of the water, which looked stagnant and greasy.

At 10.30, we were greeted with the sight of the green fringe of Ain Turâbeh, dotted with our snow-white tents, in charge of the good old Sherîf. Sent two Arabs to meet Mr. Aulick, at the mouth of the Jordan. Sherîf had heard of the fight between 'Akil and his friends with the Beni 'Adwans; we learned from him that several of the Beni Sukrs had since died of their wounds, and that the whole tribe had suffered severely.

Reconnoitered the pass over this place, to see if it would be practicable to carry up the level. It proved very steep and difficult, but those at 'Ain Feshkhah and Ain Jidy are yet more so; and, after consultation with Mr. Dale, determined to attempt the present one. Made arrangements for camels, to transport the boats across to the Mediterranean. The weather very warm.

Saturday, May 6. A warm but not oppressive morning; the same mist over the sea; the same wild and awful aspect of the overhanging cliffs. Commenced taking the copper boat apart, and to level up this difficult pass. To Mr. Dale, as fully competent, I assigned this task. With five men and an assistant, he laboured up six hundred feet, but with great difficulty.

At 9 A.M., thermometer, in the shade, 100°; the sky curtained with thin, misty clouds. At 11 A.M., Mr. Aulick returned, having completed the topography of the shore, and taken observations and bearings at the mouth of the Jordan. Dr. Anderson had collected many specimens in the geological department. The exploration of this sea was now complete. Sent Mr. Aulick out again, in the iron boat, to make experiments with the self-registering thermometer, at various depths; the result the same as yesterday and the day previous, the coldest stratum being at ten fathoms. Light, flickering airs, and very sultry during the night.

Sunday, May 7. This day was given to rest. The weather during the morning was exceedingly sultry and oppressive. At 8.30, thermometer 106°. The clouds were motionless, the sea unruffled, the rugged faces of the rocks without a shadow, and the canes and tamarisks around the fountain drooped their heads towards the only element which could sustain them under the smiting heat. The Sherîf slept in his tent, the Arabs in various listless attitudes around him; and the mist of evaporation hung over the sea, almost hiding the opposite cliffs.

At 6 P.M., a hot hurricane, another sirocco, blew down the tents and broke the syphon barometer, our last remaining one. The wind shifted in currents from N.W. to S.E.; excessively hot. In two hours it had gradually subsided to a sultry calm. All suffered very much from languor, and prudence warned us to begone. The temperature of the night was pleasanter than that of the day, and we slept soundly the sleep of exhaustion.

Monday, May 8. A cloudy, sultry morning. At 5 A.M., the leveling party proceeded up the pass to continue the leveling. At 8, the sun burst through his cloudy screen, and threatened an oppressive day. Constructed a large float, with a flag-staff fitted to it.

In the morning, a bird was heard singing in the thicket near the fountain, its notes resembling those of the nightingale of Italy. The bulbul, the nightingale of this region, is like our kingfisher, except that its plumage is brown and blue, and the bill a deep scarlet. We cannot say that we ever heard it sing; but at various places on the Jordan we heard a bird singing at night, and the Arabs said it was the bulbul.

The heat increased with the ascending sun, and at meridian the thermometer stood at 110° in the shade. The Sherîf's tent was dark and silent, and we were compelled to discontinue work. The surface of the sea was covered by an impenetrable mist, which concealed the two extremities and the eastern shore; and we had the prospect of a boundless ocean with an obscured horizon. At 1.30 P.M., a breeze sprang up from the S.E., which gradually freshened and hauled to the north. Towards sunset went into Ain Ghuweir, a short distance to the north. So far from being brackish, we found the water as sweet and refreshing as that of Ain Turâbeh.

At 4 P.M., the leveling party returned, having leveled over the crest of the mountain and 300 feet on the desert of Judea. They had been compelled to discontinue work by the high wind. The tent I sent them was blown down, and they were forced to dine under the "shadow of a rock."

Tuesday, May 9. Awakened at early daylight by the Muslim call to prayer. A light wind from N.E. Sky obscured; a mist over the sea, but less dense than that of yesterday. Sent Mr. Dale with the interpreter to reconnoitre the route over the desert towards Jerusalem. Pulled out in the Fanny Skinner, and moored a large float, with the American ensign flying, in eighty fathoms water, abreast of Ain Ghuweir, at too long a distance from the shore to be disturbed by the Arabs. Sent George Overstock and Hugh Read, sick seamen, to the convent of Mar Saba. Wind light throughout the day, ranging from N. to S.E.

Nusrallah, sheikh of the Rashâyideh, to whom I had refused to present before our work was complete, said to Sherîf to-day that if it had not been for him (Sherîf), he would have found means of getting what he wanted, intimating by force. On the matter being reported, he was ordered instantly to leave the camp. On his profession of great sorrow, and at the intercession of the Sherîf, he was permitted to remain, with the understanding that another remark of the kind would cause his immediate expulsion.

Sent off the boats in sections to Bab el Hulil (Jaffa gate), Jerusalem. Tried the relative density of the water of this sea and of the Atlantic--the latter from 25° N. latitude and 52° W. longitude; distilled water being as 1. The water of the Atlantic was 1.02, and of this sea 1.13. The last dissolved 1/11, the water of the Atlantic 1/6, and distilled water 5/17 of its weight of salt. The salt used was a little damp. On leaving the Jordan we carefully noted the draught of the boats. With the same loads they drew one inch less water when afloat upon this sea than in the river.3

The streams from the fountains of Turâbeh, Ain Jidy, and the salt spring near Muhariwat, were almost wholly absorbed in the plains, as well as those running down the ravines of Sudeir, Sêyâl, Mubughghik, and Humeir, and the torrent between the Arnon and Callirohoe. Taking the mean depth, width, and velocity of its more constant tributaries, I had estimated the quantity of water which the Dead Sea was hourly receiving from them at the time of our visit, but the calculation is one so liable to error, that I withhold it. It is scarcely necessary to say, that the quantity varies with the season, being greater during the winter rains, and much less in the heat of summer.

At 8.30, Mr. Dale and the interpreter returned. Before retiring, we bathed in the Dead Sea, preparatory to spending our twenty-second and last night upon it. We have carefully sounded this sea, determined its geographical position, taken the exact topography of its shores, ascertained the temperature, width, depth, and velocity of its tributaries, collected specimens of every kind, and noted the winds, currents, changes of the weather, and all atmospheric phenomena. These, with a faithful narrative of events, will give a correct idea of this wondrous body of water, as it appeared to us.

From the summit of these cliffs, in a line a little north of west, about sixteen miles distant, is Hebron, a short distance from which Dr. Robinson found the dividing ridge between the Mediterranean and this sea. From Beni Na'im, the reputed tomb of Lot, upon that ridge, it is supposed that Abraham looked "toward all the land of the plain," and beheld the smoke, "as the smoke of a furnace." The inference from the Bible, that this entire chasm was a plain sunk and "overwhelmed" by the wrath of God, seems to be sustained by the extraordinary character of our soundings. The bottom of this sea consists of two submerged plains, an elevated and a depressed one; the former averaging thirteen, the last about thirteen hundred feet below the surface. Through the northern, and largest and deepest one, in a line corresponding with the bed of the Jordan, is a ravine, which again seems to correspond with the Wady el Jeib, or ravine within a ravine, at the south end of the sea.

Between the Jabok and this sea, we unexpectedly found a sudden breakdown in the bed of the Jordan. if there be a similar break in the water-courses to the south of the sea, accompanied with like volcanic characters, there can scarce be a doubt that the whole Ghor has sunk from some extraordinary convulsion; preceded, most probably, by an eruption of fire, and a general conflagration of the bitumen which abounded in the plain. I shall ever regret that we were not authorized to explore the southern Ghor to the Rea Sea.

All our observations have impressed me forcibly with the conviction that the mountains are older than the sea. Had their relative levels been the same at first, the torrents would have worn their beds in a gradual and correlative slope;--whereas, in the northern section, the part supposed to have been so deeply engulfed, although a soft, bituminous limestone prevails, the torrents plunge down several hundred feet, while on both sides of the southern portion, the ravines come down without abruptness, although the head of Wady Kerak is more than a thousand feet higher than the head of Wady Ghuweir. Most of the ravines, too, as reference to the map will show, have a southward inclination near their outlets, that of Zerka Main or Callirohoe especially, which, next to the Jordan, must pour down the greatest volume of water in the rainy season. But even if they had not that deflection, the argument which has been based on this supposition would be untenable; for tributaries, like all other streams, seek the greatest declivities without regard to angular inclination. The Yermak flows into the Jordan at a right angle, and the Jabok with an acute one to its descending course.

There are many other things tending to the same conclusion, among them the isolation of the mountain of Usdum; its difference of contour and of range, and its consisting entirely of a volcanic product.

But it is for the learned to comment on the facts we have laboriously collected. Upon ourselves, the result is a decided one. We entered upon this sea with conflicting opinions. One of the party was skeptical, and another, I think, a professed unbeliever of the Mosaic account,. After twenty-two days' close investigation, if I am not mistaken, we are unanimous in the conviction of the truth of the Scriptural account of the destruction of the cities of the plain. I record with diffidence the conclusions we have reached, simply as a protest against the shallow deductions of would-be unbelievers.

At midnight the scene was the same as at Ain el Feshkhah, the first night of our arrival, save that the ground was more firm and the weather warmer; but the sea presented a similar unnatural aspect. There was also a new feature betokening a coming change; there were camels lying around, which had been brought in, preparatory to to-morrow's movement. Heretofore, I had always seen this animal reposing upon its knees, but on this occasion all not chewing the cud were lying down. The night passed away quietly, and a light wind springing up from the north, even the most anxious were at length lulled to sleep by the rippling waves, as they brattled upon the shore.

Chapter XIX. From the Dead Sea to the Convent of Mar Saba.

Wednesday, May 10. A clear, warm, but pleasant morning. Soon after daylight, sent Mr. Aulick and Mr. Bedlow to Jerusalem with the chronometers, to make observations for ascertaining their rate. At 7 A.M., the levelling party started. Made preparations for finally breaking up the camp on the Dead Sea.

At 9.30, struck tents, and at 10, started, and ascended the pass of Ain Turâbeh. With us were Sherîf, Ibrahim Aga, and the sheikhs of the Raschâyideh and Ta'âmirah, and six camels. Winding slowly up the steep pass, we looked back at every turn upon our last place of encampment, and upon the silent sea. We are ever sad on parting with things for the last time. The feeling that we are never to seem them again, makes us painfully sensible of our own mortality.

At 12, overtook the levelling party, and shortly after the camels with the sections of the boats. At 1.15 P.M., camped in Wady Khiyam Seyâ'rah (Ravine of the Tents of Seyâ'rah), so called from a tribe of that name having been surprised and murdered here. It is a rocky glen, over a steep precipice, a thousand feet above the Dead Sea. There are two large caves on the north side of the ravine, in which we prepared to take up our quarters, but the Arabs dissuaded us with the assurance that they abound with serpents and scorpions, which crawl out in the night.

Our camp was, properly speaking, in a depression of the extremity of the ridge between the ravines of Ghuweir and En Nar.

At night, we invited Sherîf to our tent, and prevailed on him to tell his history. His father was Sherîf, or hereditary governor of Mecca, to which dignity, at his death, the eldest brother of our friend succeeded. When Mecca surrendered to Mehemet Ali, his brother was deposed; and a cousin, inimical to them, was appointed in his stead. The deposed Sherîf fled to Constantinople; our friend was carried captive to Cairo, where he was detained ten years a prisoner, but provided with a house, and an allowance of 3000 piastres (125 dollars) per month for his support. When Arabia was overrun by the Wahabees, Mehemet Ali, wisely counting on sectarian animosity, gave our Sherîf a command, and sent him to the war. His person bears many marks of wounds he received in various actions. When Mehemet Ali was compelled by the quintuple alliance to abandon his conquests, our Sherîf went to Egypt to claim his pay, and reimbursements for advances he had made. Put off with vague promises, he proceeded to Stambohl (Constantinople) to sue for redress, and having laid his application before the divan, was now awaiting the decision. His account of himself is sustained by the information we received from our Vice-Consul and Mr. Fingie, H.B.M. Vice-Consul at Acre, respecting him. He is intelligent and much reverenced, and, in consequence, very influential among the tribes. To him and to 'Akil, coupled with our own vigilance, we may in a great measure ascribe our not having encountered difficulty with the Arabs. He was to leave us the next day, and would carry with him our respect and fervent good wishes. We often remarked among ourselves, what should we have done without Sherîf and 'Akil; we have not the slightest doubt that their presence prevented bloodshed.

A monk from the Convent of Mar Saba came in this evening, and brought word that our sick sailors were doing well. There seemed to be a good understanding between these religious and the various tribes; at night, an Arab shared his aba with the monk, and the shaven-crown of the Christian and the scalp-lock of the Muslim were covered by the same garment.

In a few hours we had materially changed our climate, and in this elevated region the air was quite cool. We slept delightfully, drawing our cloaks yet closer as the night advanced. At 4 A.M., thermometer 60°; absolutely cold.

We were in a most dreary country; calcined hills and barren valleys, furrowed by torrent beds, all without a tree or shrub, or sign of vegetation. The stillness of death reigned on one side; the sea of death, calm and curtained in mist, lay upon the other; and yet this is the most interesting country in the world. This is the wilderness of Judea; near this, God conversed with Abraham; and here, came John the Baptist, preaching the glad tidings of salvation. These verdureless hills and arid valleys have echoed the words of the Great Precursor; and at the head of the next ravine lies Bethlehem, the birth-place of the meek Redeemer,--in full sight of the Holy City, the theatre of the most wondrous events recorded on the page of history,--where that self-sacrifice was offered, which became thenceforth the seal of a perpetual covenant between God and man!

Thursday, May 11. There is, perhaps, no greater trial to the constitution than sudden changes of atmospheric temperature; in other words, of climate. We were so enfeebled by the heat we had experienced in the chasm beneath us, that, at the temperature of 60°, the air here felt piercingly cold. We had shivered through the night; and so busy had been the sentinels in searching for dried thistles and shrubs, to feed the watch-fires, that, perhaps, in all our wanderings, the guard had never been so remiss.

We began, early, to prepare for work and sent off three camel-loads of specimens, &c., to Jerusalem. Settled and parted with the good Sherîf.

Breakfasted in the rocky glen, with our backs towards the barren hills of the Desert of Judea; while the rays of the sun, rising over the mountains of Moab, were reflected from the glassy surface of the desolate sea before us.

We levelled, to-day, over parched valleys, and sterile ridges, to the flattened summit of an elevation, at the base of which three ravines meet, called the "Meeting of the Tribes,"--the Dead Sea concealed by an intervening ridge. We were fully 2000 feet above it, and the wind was fierce and cutting. Strolling from the camp, soon after we had pitched the tents, I felt so cold as to be compelled to return to my tent. The thermometer, at the opening, stood at 69° but 7° below summer-heat. This place derives its name from a gathering of the tribes, or council, once held here. We saw, to-day, a light-brown fox, with a white tail.

Friday, May 12. The morning and the evening cool; the mid-day warm. Levelled into and up the Wady en Nar (Ravine of Fire) to the Greek Convent of Mar Saba. The ravine was shut in, on each side, by high, barren cliffs of chalky limestone, which, while they excluded the air, threw their reverberated heat upon us, and made the day's work an uncomfortable one. There was an association connected with the scene, however, which sustained us under the blinding light and oppressive heat of noon. The dry torrent-bed, interrupted by boulders, and covered with fragments of stone, is the channel of the brook Kidron, which, in its season, flows by the walls of the Holy City.

The approach to the convent is striking, from the lofty, perpendicular cliffs on each side, perforated with a great many natural and artificial excavations. Immense labour, sustained by a fervent though mistaken zeal, must have been expended here.

A perpendicular cliff, of about 400 feet, has its face covered with walls, terraces, chapels, and churches, constructed of solid masonry, all now in perfect repair. The walls of this convent, with a semicircular-concave sweep, run along the western bank of the ravine, from the bottom to the summit. The buildings form detached parts, constructed at different periods.

At 3.30 P.M., coming up from the ravine, we descended an inclined wady, and camped outside of the western gate of the convent, under a broad ledge of rock, forming the head of a lateral ravine, running into the main one. A narrow platform was before us, with a sheer descent from its edge to the bottom of the small ravine, which bore a few scattering fig-trees. We were earnestly invited to take up our quarters inside; but, dreading the fleas, we preferred the open air. There was a lofty look-out tower on the hill above us, to the south.

At the foot of a slight descent, about pistol-shot distance, was a low door, through which we were admitted to visit the convent. By the meagre monk who let us in, we were conducted through a long passage, and down two flights of stairs, into a court paved with flags; on the right centre of which stood a small, round chapel, containing the tomb of St. Saba. On the opposite side was the church, gorgeously gilded and adorned with panel and fresco paintings; the former enshrined in sliver, and some of them good; the latter, mere daubs. The pavement was smooth, variegated marble; there were two clocks, near the altar; and two large, rich, golden chandeliers, and many ostrich-eggs, suspended from the ceiling.

From the court we were led along a terraced walk, parallel with the ravine, with some pomegranate-trees and a small garden-patch on each side; and, ascending a few steps, turned shortly to the left, and were ushered into the parlour, immediately over the chasm. The adjoining room was occupied by our two sick men, of whom admirable care had been taken, and we rejoiced to find that they were convalescent. The parlour was about sixteen by twenty-four feet, almost entirely carpeted, with a slightly-elevated divan on two sides. The stinted pomegranate-trees and the few peppers growing in the mimic garden were refreshing to the eye; and, after a lapse of twenty-two days, we enjoyed the luxury of sitting upon chairs.

From the flat, terrace roofs, are stairways of cut stone, leading to excavations in the rock, which are the habitations of the monks. We visited one of them, high up the impending cliff. It consisted of two cells, the inner one mostly the work of the present tenant. They were then dry and comfortable, but in the rainy season must be exceedingly damp and unwholesome.

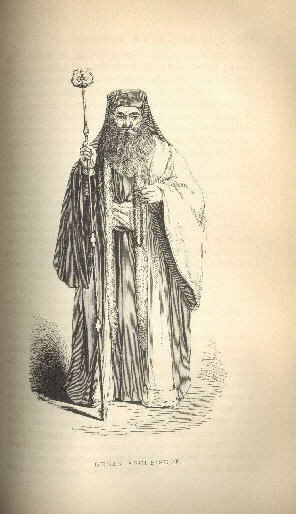

Within the convent, we were told that there are seventy wells, and numerous cisterns, with abundance of rain-water. There are many flights of stairs, corridors, and cells; among the last, that of John of Damascus. A lofty tower shoots, shaft-like, from the northern angle, and a lone palm-tree rears its graceful form beside it. Near the chapel of St. Saba, is a singular cemetery, containing a great many skulls, piled against the walls,--a sad memorial of an act of cruelty on the part of the Turks and the Persians;--Chosroes, king of Persia, having, in the sixth century, put to death a number of monks, whose skulls are collected here. The room is excavated in the rock, and may have the preservative qualities such a legend would infer. In times of scarcity, the Arabs throng here for food, which is given to them gratuitously; and to this, doubtless, is attributable the popularity of the inmates of the convent with the wandering tribes. The monks live solely upon a vegetable diet. There are about thirty in the convent, including lay-brothers, and, except a few from Russia, they are all Greeks. They are good-natured, illiterate, and credulous. The archbishop, from Jerusalem, looked like a being of a superior order among them, and, in his pontifical attire, presented an imposing appearance.

The interior of the convent is far more extensive than one would suppose, looking upon it from the western side, whence only the tower, the top of the church, and a part of the walls are visible.

There is egress from the convent to the ravine by means of a ladder, which, at will, is let down from a low, arched door. The sight, from the bottom of the ravine, is one well calculated to inspire awe. The chasm is here about 600 feet wide and 400 deep,--a broad, deep gorge, or fissure, between lofty mountains, the steep and barren sides of which are furrowed by the winter rains. There are many excavations in the face of the cliffs, on both sides of the ravine, below the convent. One of them has evidently been a chapel, and on its walls are carved the names of many pilgrims, mostly Greeks, from 1665 to 1674, and, after the lapse of upwards of a century, from 1804 to 1843. A little above the convent, on the west side, halfway up, on the abrupt face of the precipice, are the ruins of a building, a chapel or a fortress. One story is standing, with a tower, pierced with loop-holes. The numerous excavations present a most singular appearance; and, looking upon them one expects every moment to see the inmates come forth. It is a city of caverns.

We walked some distance up the bed of the Kidron, and encountered several precipices from ten to twelve feet high, down which cataracts plunge in winter. It will be difficult, but not impracticable, to level this torrent bed. Collected some fossils, and a few flowers, for preservation. Even at this early season, the scanty vegetation, scattered here and there in the ravines of the desert of Judea, was already parched and withered. There were but few flowers within this ravine; the scarlet anemone and the purple blossom of the thistle being the prevailing ones. We gathered one, however, which was star-shaped; the leaves white near the stem, but blue above, and the seed-stalks yellow, with white heads. A few leaves nearest the flower were green, but the rest, with the stalk, were parched and dry. It was inodorous, and, like beauty without virtue, fair and attractive to the eye, but crumbling from rottenness in the hands of him who admiringly plucks it. In this ravine, from the Dead Sea to the borders of cultivation, we have, besides, gathered for our herbarium, the blue weed, so well known in Maryland and Virginia for its destructive qualities; the white henbane; the dyer's weed, used in Europe for dyeing green and yellow; the dwarf mallow, commonly called cresses, and the caper plant, the unopened flower-buds of which, preserved in vinegar, are so much used as a condiment.

R.E. Griffith, M.D., of Philadelphia, with whom our botanical collection has been placed for classification, cites an opinion, supported by strong argument, that the last-named plant is the hyssop of Scripture.

During the night, we had a severe thunder storm, with a slight shower of rain. One of the camels, in its fright, fell into the ravine before the caverns where we slept, and kept us long awake with its discordant cries. The animal was unhurt; but the Arabs tortured it, by their fruitless endeavours to extricate it in the dark. They were alike deaf to advice, entreaties, and commands, until one of the sentries was ordered to charge upon them, when they hurriedly dispersed, and the poor camel and ourselves were left in quietude.

Saturday, May 13. Calm and cloudy. 6 A.M., thermometer 68°. It had been 53° during the night, and 79° at 11 A.M. the preceding day. Deferred levelling any farther, until we had reconnoitred the two routes to Jerusalem. The one up the ravine, although presenting great difficulties, proved more practicable than the route we had come. Let all hands rest until Monday. Extricated the camel from the ravine.

Sunday, May 14. A quiet day--wind east; weather pleasant. Collected some fossils, and a few flowers, for preservation. At meridian, temperature 76°; at midnight, 58°. While here, several of the beddin, or coney of Scripture, were seen among the rocks.

Chapter XX. From Mar Saba to Jerusalem.

Monday, May 15. Wind S.W.; partially cloudy. Thermometer, at 2 A.M., 58°; at Meridian, 72°. Discharged all the Arabs, except a guide and the necessary camel-drivers. The levelling party worked up the bed of the Kidron, while the camp proceeded along the edge of the western cliff. In about two hours, we passed a large cistern, hewn in the rock, twenty feet long, twelve wide, and eighteen high. There was water in it to the depth of four feet, and its surface was coated with green slime. In it two Arabs were bathing. Nevertheless, our beasts and ourselves were compelled to drink it. Soon after, isolated tufts of scant and parched vegetation began to appear upon the hill-sides. We were truly in a desert. There was no difference of hue between the dry torrent-bed and the sides and summits of the mountains. From the Great Sea, which washes the sandy plain on the west, to that bitter sea on the east, which bears no living thing within it, all was dreary desolation! The very birds and animals, as on the shores of the Dead Sea, were of the same dull-brown colour,--the colour of ashes. How literally is the prophecy of Joel fulfilled! "That which the palmer-worm hath left, hath the locust eaten; and that which the locust hath left, hath the canker-worm eaten; and that which the canker-worm hath left, hath the caterpillar eaten. The field is wasted, the land mourneth, and joy is withered from the sons of men."

How different the appearance of the mountain districts of our own land at this season! There, hills and plains, as graceful in their sweep as the arrested billows of a mighty ocean, are before and around the delighted traveller. Diversified in scenery, luxuriant of foliage, and, like virgin ore, crumbling from their own richness, they teem with their abundant products. The lowing herds, the bleating flocks, the choral songsters of the grove, gratify and delight the ear; the clustering fruit-blossoms, the waving corn, the grain slow bending to the breeze, proclaim an early and redundant harvest. More boundless than the view, that glorious land is uninterrupted in its sweep until the one extreme is locked in the fast embrace of thick-ribbed ice, and the other is washed by the phosphorescent ripple of the tropic; while, on either side, is heard the murmuring surge of a wide-spread and magnificent ocean. Who can look upon that land and not thank God that his lot is cast within it? And yet this country, scathed by the wrath of an offended Deity, teems with associations of the most thrilling events recorded in the book of time. The patriot may glory in the one,--the Christian of every clime must weep, but, even in weeping, hope for the other.

Soon after leaving the cistern, or pool, we passed an Arab burial-ground, the graves indicated by a double line of rude stones, as at kerak; excepting one of a sheikh, over which was a plastered tomb. Before it our Arab guide stopped, and, bowing his head, recited a short prayer.

As we thence advanced, pursuing a north-westerly course, signs of cultivation began to exhibit themselves. On each side of use were magnificent rounded and sharp-crested hills; and, on the top of one, we soon after saw the black tents of an Arab encampment; some camels and goats browsing along the sides; and, upon the very summit, the figures of some fellahas (Arab peasant women) cut sharp against the sky.

A little farther on, we came to a small patch of tobacco, in a narrow ravine, the cotylidons just appearing; and, in the shadow of a rock, a fellah was seated, with his long gun, to guard it. Half a mile farther, we met an Arab, a genuine Bedawy, wearing a sheepskin aba, the fur inwards and driving before him a she-camel, with its foal. A little after, still following the bed of the Kidron, we came to the fork of the pilgrim's road, which turns to the north, at the foot of a high hill, on the summit of which was a large encampment of the tribe Subeih. Leaving the pilgrim's road on the right, we skirted the southern base of the hill, with patches of wheat and barley covering the surface of the narrow valley;--the wheat just heading, and the fields of barley literally "white for the harvest." Standing by the roadside, was a fellaha, with a child in her arms, who courteously saluted us. She did not appear to be more than sixteen.

The valley was here about two hundred yards wide; and to our eyes, so long unused to the sight of vegetation, presented a beautiful appearance. The people of the village collected in crowds to look upon us as we passed far beneath them. Some of them came down and declared that they would not permit the 'Abeidîyeh (of which tribe were our camel-drivers) to pass through their territory; and claimed for themselves the privilege of furnishing camels. We paid no attention to them, but camped on the west side of the hill, where the valley sweeps to the north.

Tuesday, May 16. Weather clear, cool, and delightful. At daylight, recommenced levelling. Soon after, the sheikh of the village above us, with fifteen or twenty followers, armed with long guns, came down and demanded money for passing through his territory. On our refusal, high word ensued; but finding his efforts at intimidation unsuccessful, he presented us with a sheep, which he refused to sell, but gave it, he said, as a backshish. Knowing that an extravagant return was expected, and determined not to humour him, I directed the fair value of the sheep, in money, to be given. Finding that no more was to be obtained, he left us.

It was a pastoral sight, when we broke up camp, this morning. The sun was just rising over the eastern hills; and, in every direction, we heard shepherds calling to each other from height to height, their voices mingling with the bleating of sheep and goats, and the lowing of numerous cattle. Reapers were harvesting in every field; around the threshing-floors the oxen, three abreast, were treading out the grain; and women were passing to and from, bearing huge bundles of grain in the straw, or pitchers of leban (sour milk), upon their heads. Every available part of this valley is cultivated. The mode of harvesting is primitive. The reaping-hook alone is used; the cradle seemed to be unknown. The scene reminded one forcibly of the fields of Boaz, and Ruth the gleaner. But, with all its peaceful aspect, there was a feature of insecurity. Along the bases of the hills, from time to time shifting their positions, to keep within the shade, were several armed fellahin, guarding the reapers and the grain. The remark of Volney yet holds true:--"the countryman must sow with his musket in his hand, and no more is sown that is necessary for subsistence."

Towards noon it became very warm, and we were thirsty. Meeting an old Arab woman, we despatched her to the Subeih for some leban. We noticed that 'Awad, our Ta'âmirah guide, was exceedingly polite to her. But when she returned, accompanied by her daughter, a young and pretty fellaha, he became sad, and scarce said a word while they remained. On being asked the reason of his sudden sadness, he confessed that he had once spent twelve months with that tribe, sleeping, according to the custom of Arab courtship, every night outside of the young girl's tent, in the hope of winning her for his wife. He said that they were mutually attached, but that the mother was opposed to him, and the father demanded 4000 piastres, about 170 dollars. 'Awad had 2000 piastres, the earnings of his whole life, and in the hope of buying her (for such is the true name of an Arab marriage), he determined to sell his horse, which he valued at 1000 piastres, or a little over forty dollars. But,

"The course of true love did never yet run smooth;"

and unfortunately his horse died, which reduced him to despair. Shortly after, the girl's uncle claimed her for his son, then five years old, offering to give his daughter to her brother. According to an immemorial custom of the Arabs, such a claim took precedence of all others, and the beautiful girl, just ripening into womanhood was betrothed to the child. With the philosophy of his race, however, 'Awad subsequently consoled himself with a wife; but, true to his first love, never sees its object without violent emotion.

He further told us, that in the same camp there was another girl far more beautiful than the one we had seen, for whom her father asked 6000 piastres, a little more than 250 dollars. The one we saw was slightly and symmetrically formed, and exceedingly graceful in her movements. The tawny complexion, the cheek-bones somewhat prominent, the coarse black hair, and the dark, lascivious eye, reminded us of a female Indian of our border.

Leaving the fellahin busy in their fields, and still following the ravine, we came to a narrow ridge, immediately on the other side of which were some thirty or forty black tents. Here a stain upon the rocks told a tale of blood.

An Arab widower ran off with a married woman from the encampment before us,--a most unusual crime among this people. In little more than a month, the unhappy woman died. Knowing that by the laws of the tribes he could be put to death by the injured man, or any of his or the woman's relatives he might encounter, and that they were on the watch for him; and yet anxious to return, he made overtures for a settlement. After much negotiation, the feud was reconciled on condition that he gave his daughter, 400 piastres, a camel, and some sheep to the inured man. A feast was accordingly given, and the parties embraced in seeming amity. But the son-in-law brooded over his wrong, and one day seeing the seducer of his former wife approaching, concealed himself in a cavity of the rock and deliberately shot him as he passed. Such is the Arab law of vengeance, in cases of a flagrant breach of faith like this, that all of both tribes, 'Awad told us, are now bound to put the murderer to death.

This elopement is not an isolated circumstance, although a most unusual one. The only wonder is that with such a licentious race as the Arabs, the marriage contract, wherein the woman has no choice, is not more frequently violated. Burckhardt relates a similar case, which occurred south of Kerak, in 1810.

A young man of Tafyle had eloped with the wife of another. The father of the young man with all his family had been also obliged to fly, for the Bedawin law authorized the injured husband to kill any of the offender's relations in retaliation for the loss of his wife. Proffers were made for a settlement of the difficulty, and negotiations were opened. The husband began by demanding from the young man's father two wives in return for the one carried off, and the greater part of the property which the emigrant family possessed in Tafyle. The father of the guilty wife, and her first-cousin also, demanded compensation for the insult which their family had received by the elopement. The affair was settled by the offender's father placing four infant daughters, the youngest of whom was not yet weaned, at the disposal of the husband and his father-in-law, who might betroth them to whom they pleased, and receive themselves the money which is usually paid for girls. The four girls were estimated at three thousand piastres. In testimony of peace being concluded between the two families, and of the price of blood having been paid, the young man's father, who had not yet shown himself publicly, came to shake hands with the injured husband; a white flag was suspended at the top of the tent in which they sat, a sheep was killed and the night spent in feasting. After that, the guilty pair could return in safety.

Soon after noon, we passed the last encampment of black tents, and turning aside from the line of march, I rode to the summit of a hill on the left, and beheld the Holy City, on its elevated site at the head of the ravine. With an interest never felt before, I gazed upon the hallowed spot of our redemption. Forgetting myself and all around me, I saw, in vivid fancy, the route traversed eighteen centuries before by the Man of Sorrows. Men may say what they please, but there are moments when the soul, casting aside the artificial trammels of the world will assert its claim to a celestial origin, and regardless of time and place, of sneers and sarcasms, pay its tribute at the shrine of faith, and weep for the sufferings of its founder.

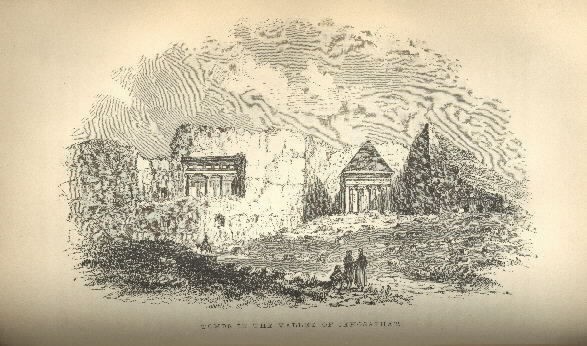

I scarce realized my position. Could it be, that with my companions I had been permitted to explore that wondrous sea, which an angry God threw as a mantle over the cities he had condemned, and of which it had been heretofore predicted that no one could traverse it and live. It was so, for there, far below, through the descending vista, lay the sombre sea. Before me, on its lofty hill, four thousand feet above that sea, was the queenly city. I cannot coincide with most travellers in decrying its position. To my unlettered mind, its site, from that view, seemed, in isolated grandeur, to be in admirable keeping with the sublimity of its associations. A lofty mountain, sloping to the south, and precipitous on the east and west, has a yawning natural fosse on those three sides, worn by the torrents of ages. The deep vale of the son of Hinnom; the profound chasm of the valley of Jehoshaphat, unite at the south-east angle of the base to form the Wady en Nar, the ravine of fire, down which, in the rainy season, the Kidron precipitates its swollen flood into the sea below.

Mellowed by time, and yet further softened by the intervening distance, the massive walls, with their towers and bastions, looked beautiful yet imposing in the golden sunlight; and above them, the only thing within their compass visible from that point, rose the glittering dome of the mosque of Omar, crowning Mount Moriah, on the site of the Holy Temple. On the other side of the chasm, commanding the city and the surrounding hills, is the Mount of Olives, its slopes darkened with the foliage of olive-trees, and on its very summit the former Church of the Ascension, now converted into a mosque.

Many writers have undertaken to describe the first sight of Jerusalem; but all that I have read convey but a faint idea of the reality. There is a gloomy grandeur in the scene which language cannot paint. My feeble pen is wholly unworthy of the effort. With fervent emotions I have made the attempt, but congealed in the process of transmission, the most glowing thoughts are turned to icicles.

The ravine as we approached Jerusalem; fields of yellow grain, orchards of olives and figs, and some apricot-trees, covered all the land in sight capable of cultivation; but not a tree, nor a bush, on the barren hill-sides. The young figs, from the size of a currant to a plum, were shooting from the extremities of the branches, while the leaf-buds were just bursting. Indeed, the fruit of the fig appears before the leaves are formed,4 and thus, when our Saviour saw a fig-tree in leaf, he had, humanly speaking, reason to expect to find fruit upon it.

Although the mountain-sides were barren, there were vestiges of terraces on nearly all of them. On the slope of one there were twenty-four, which accounts for the redundant population this country once supported.

Ascending the valley, which, at every step, presented more and more an increasing luxuriance of vegetation, the dark hue of the olive, with its dull, white blossoms, relieved by the light, rich green of the apricot and the fig; and an occasional pomegranate, thickly studded with its scarlet flowers, we came to En Rogel, the Well of Job, or of Nehemiah (where the fire of the altar was recovered), with cool, delicious water, 118 feet deep, and a small, arched, stone building over it.

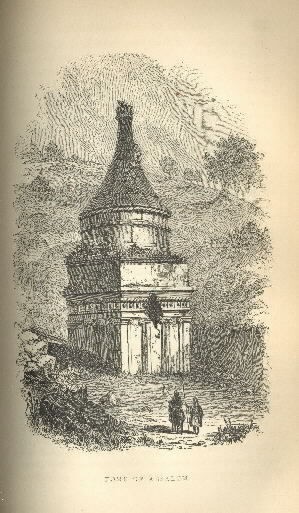

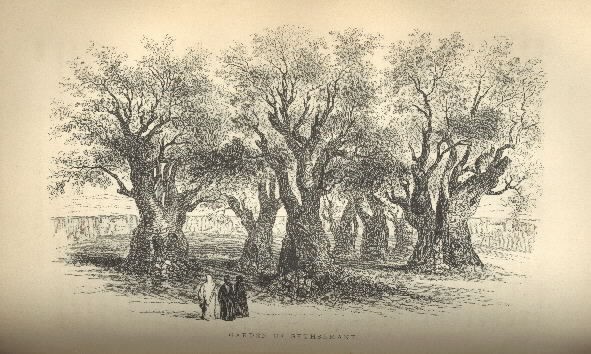

On our right, was the Mount of Offence, where Solomon worshipped Ashtaroth: before us, in the rising slope of the valley of Jehoshaphat, had been the kings' gardens in the palmy days of Jerusalem: a little above, and farther to the west, were the pool of Siloam and the fountain of the Virgin: on the opposite side of the chasm was the village of Siloam, where, it is said, Solomon kept his strange wives; and, below it, the great Jewish burial-ground, tessellated with the flat surfaces of grave-stones; and, near by, the tombs of Absalom, Zacharias, and Jehoshaphat; and, above, and beyond, and more dear in its associations than all, the garden of Gethsemane.

We here turned to the left, up the valley of the son of Hinnom, where Saul was anointed king; and, passing a tree on the right, which, according to tradition, indicates the spot where Isaiah was sawn asunder; and by a cave in which it is asserted that the apostles concealed themselves when they forsook their Master; and under the Aceldama, bought with the price of blood; and near the pool in the garden of Urias, where, from his palace, the king saw Bathsheba bathing; we levelled slowly along the skirts of Mount Zion, near the summit of which towered a mosque, above the tomb of David.

It was up Mount Zion that Abraham, steadfast in faith, led the wondering Isaac, the type of a future sacrifice.

Centuries after, a more august and a self-devoted victim, laden with the instrument of his torture, toiled along the same acclivity; but there was then no miraculous interposition; and He who felt for the anguish of a human parent, spared not Himself.