The Navy Department Library

COMBAT NARRATIVES

The Landings in North Africa

November 1942

Download PDF Version [41.3MB]

Foreword

8 January 1943

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observation of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extract from the conflicting evidence are reprinted. Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleet have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

Admiral, U.S.N.

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations.

III

Charts and Illustrations

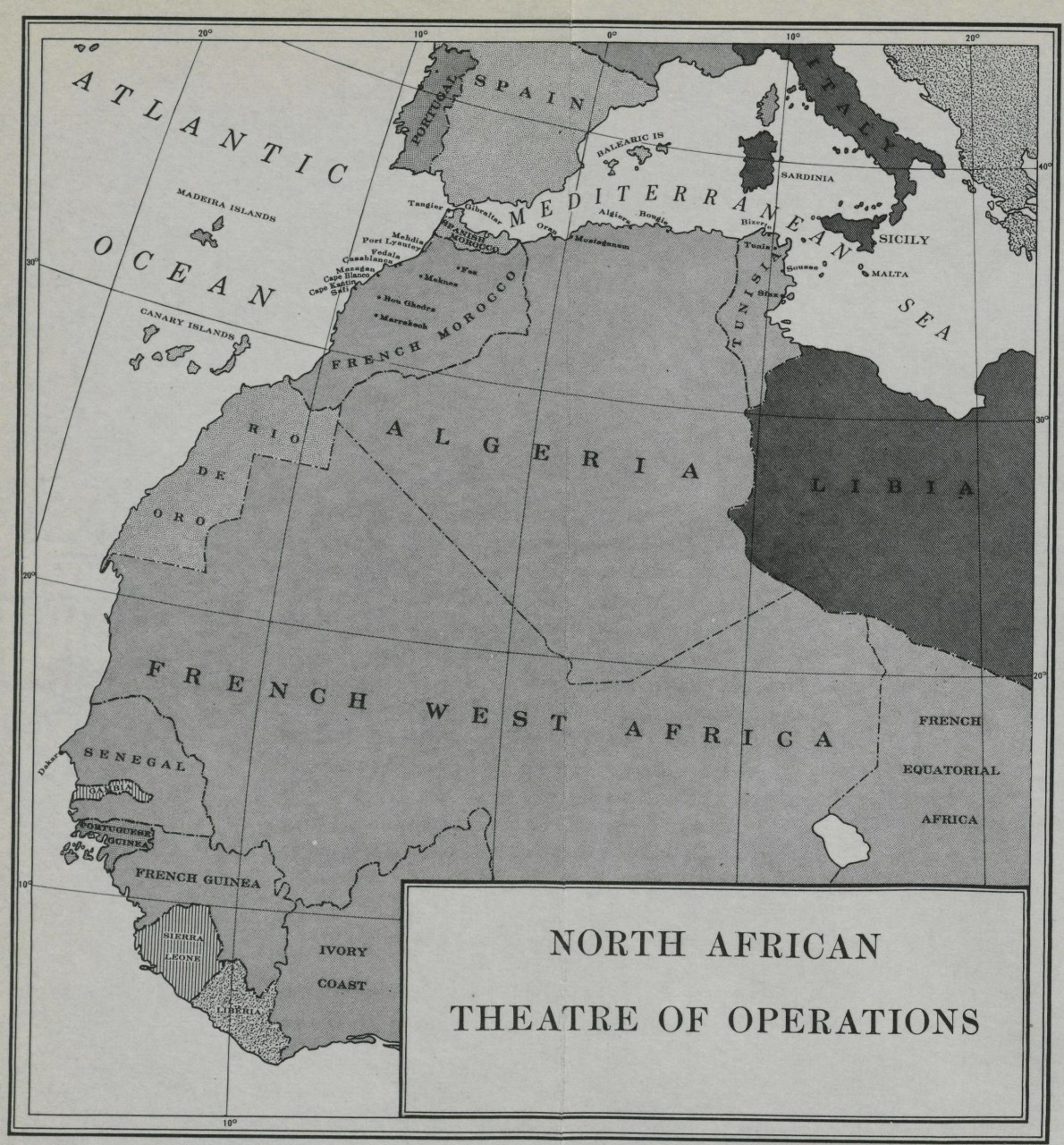

Charts: North African theater of operations |

Facing Page |

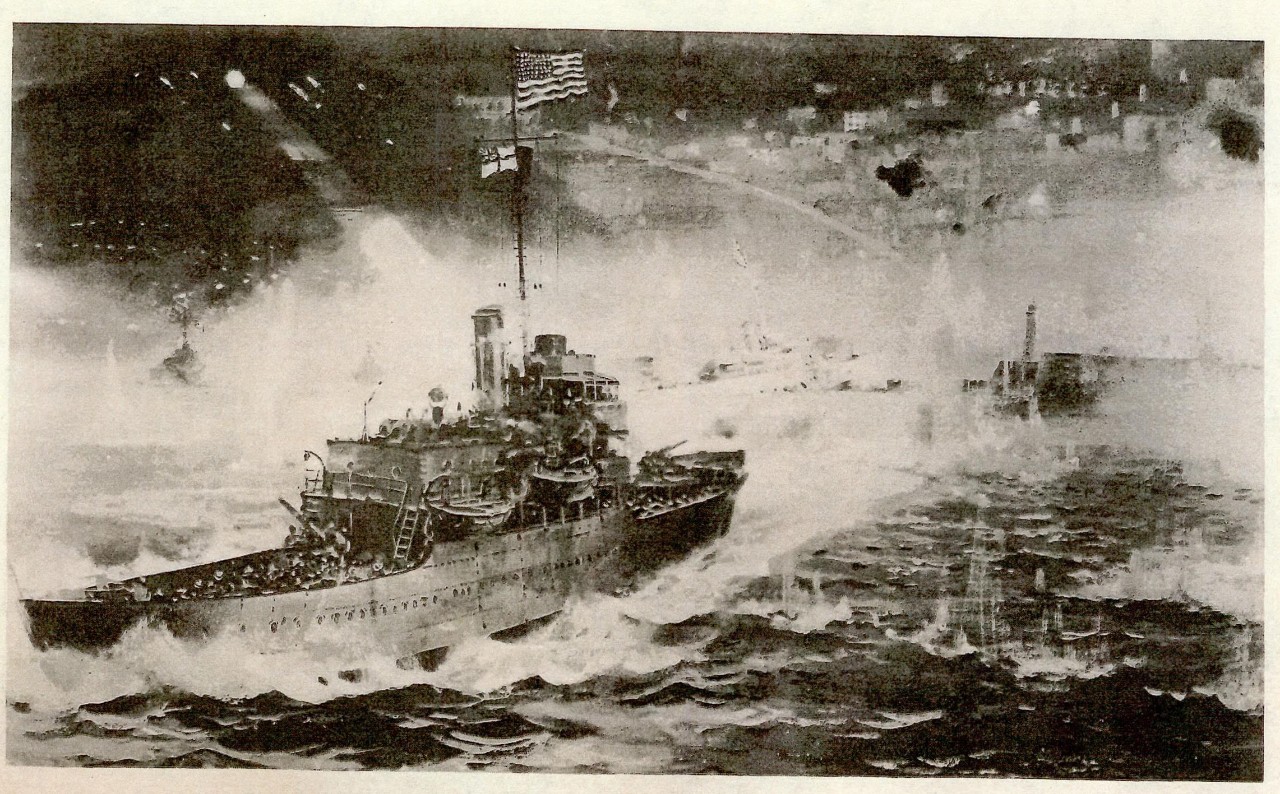

| Illustration: The Walney and Hartland entering Oran | 1 |

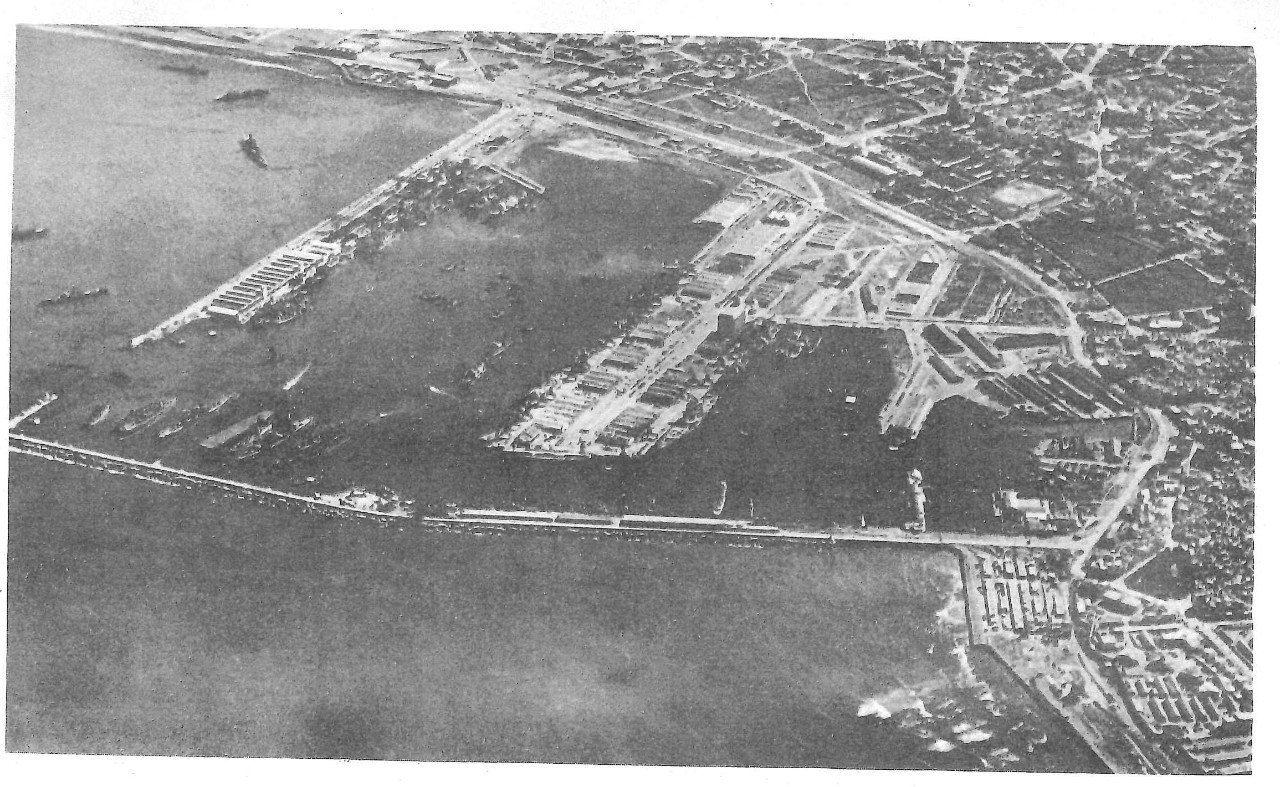

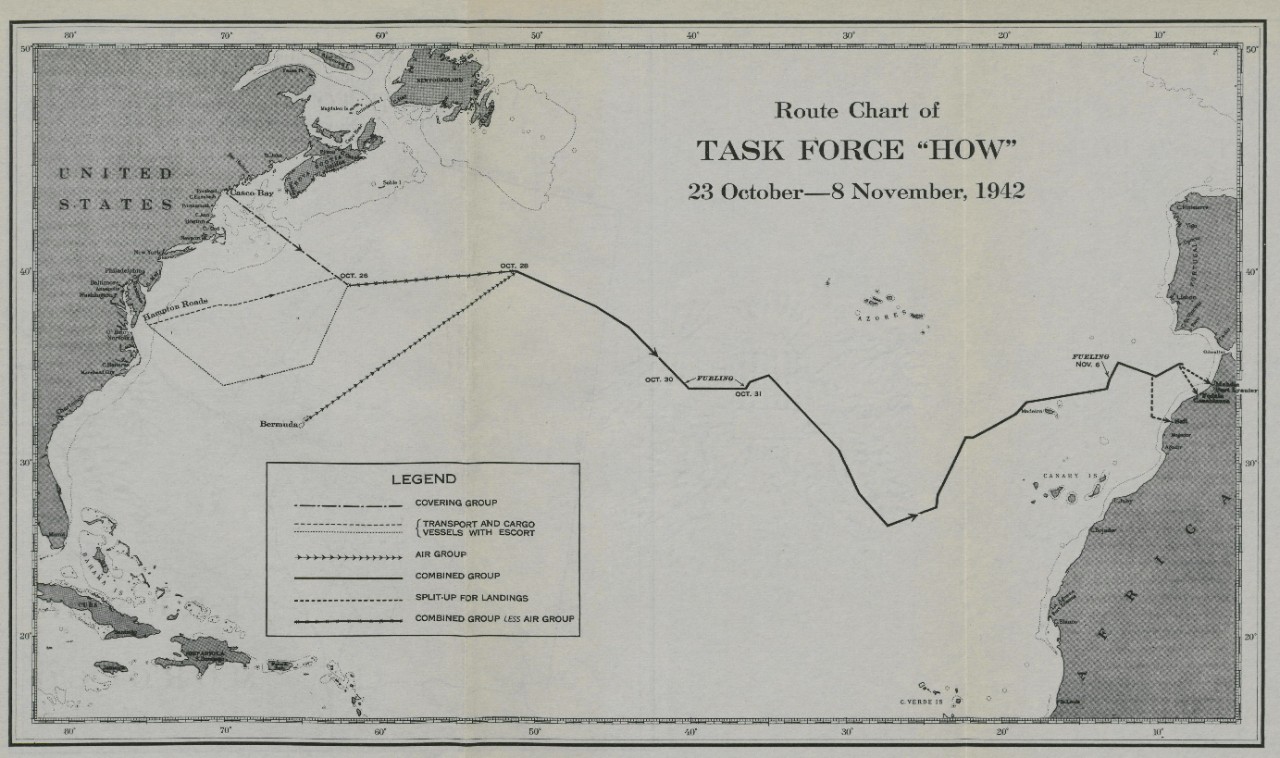

Charts: Route of Task Force, 23 October – 8 November 1942 Illustration: Casablanca Harbor |

18 |

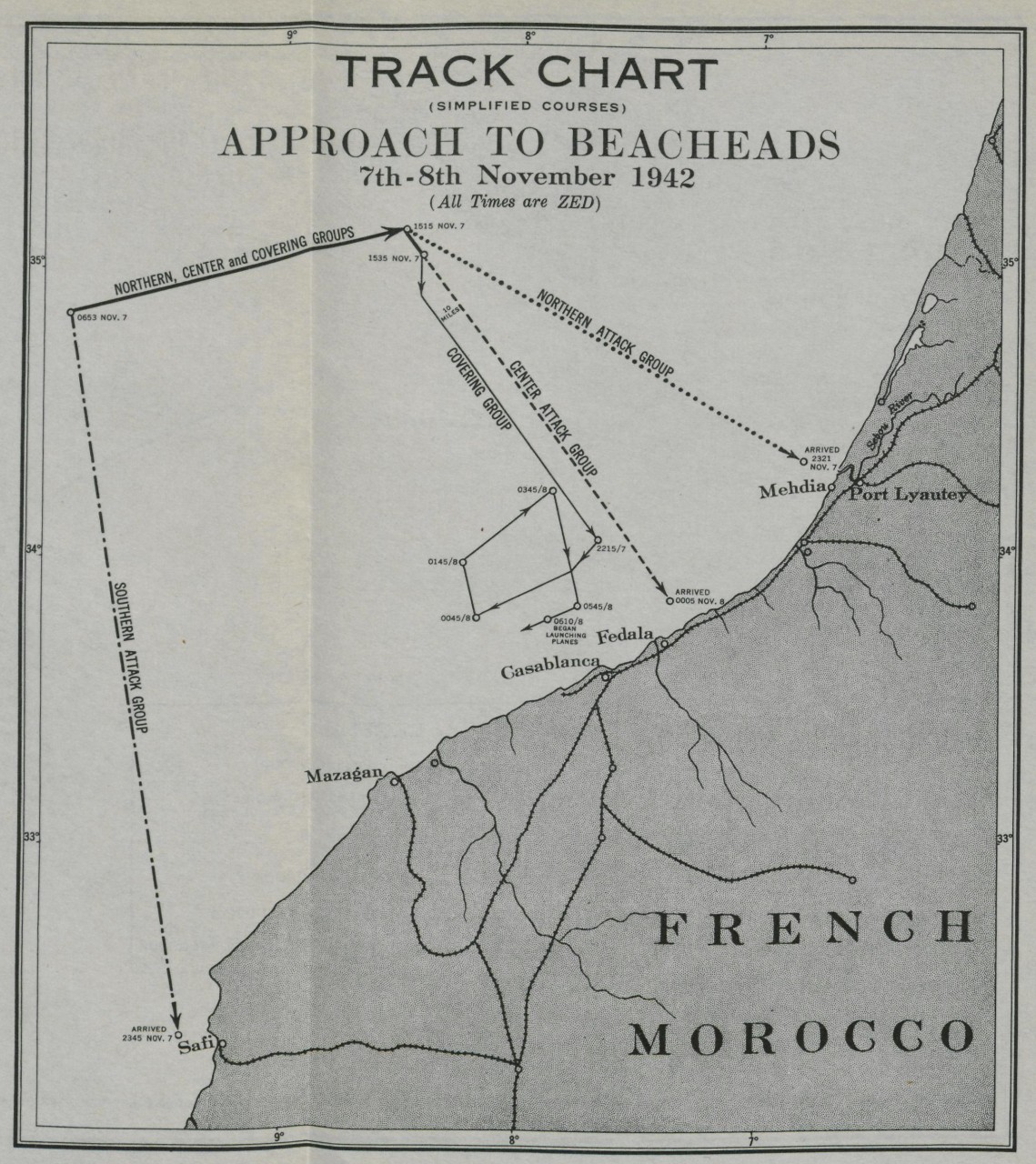

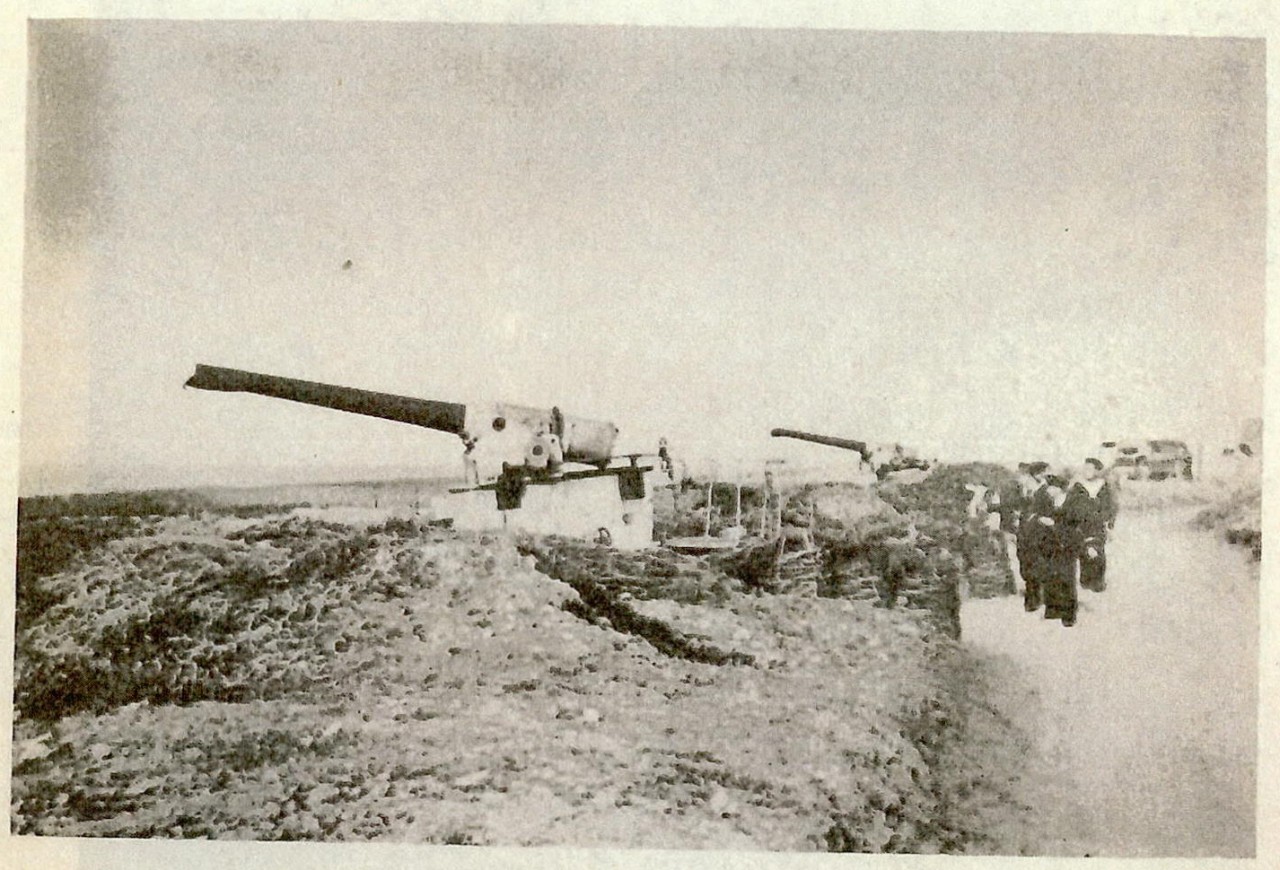

Chart: Approach to bridgeheads Illustrations: El Hank lighthouse Naval battery at Mehdia |

19 |

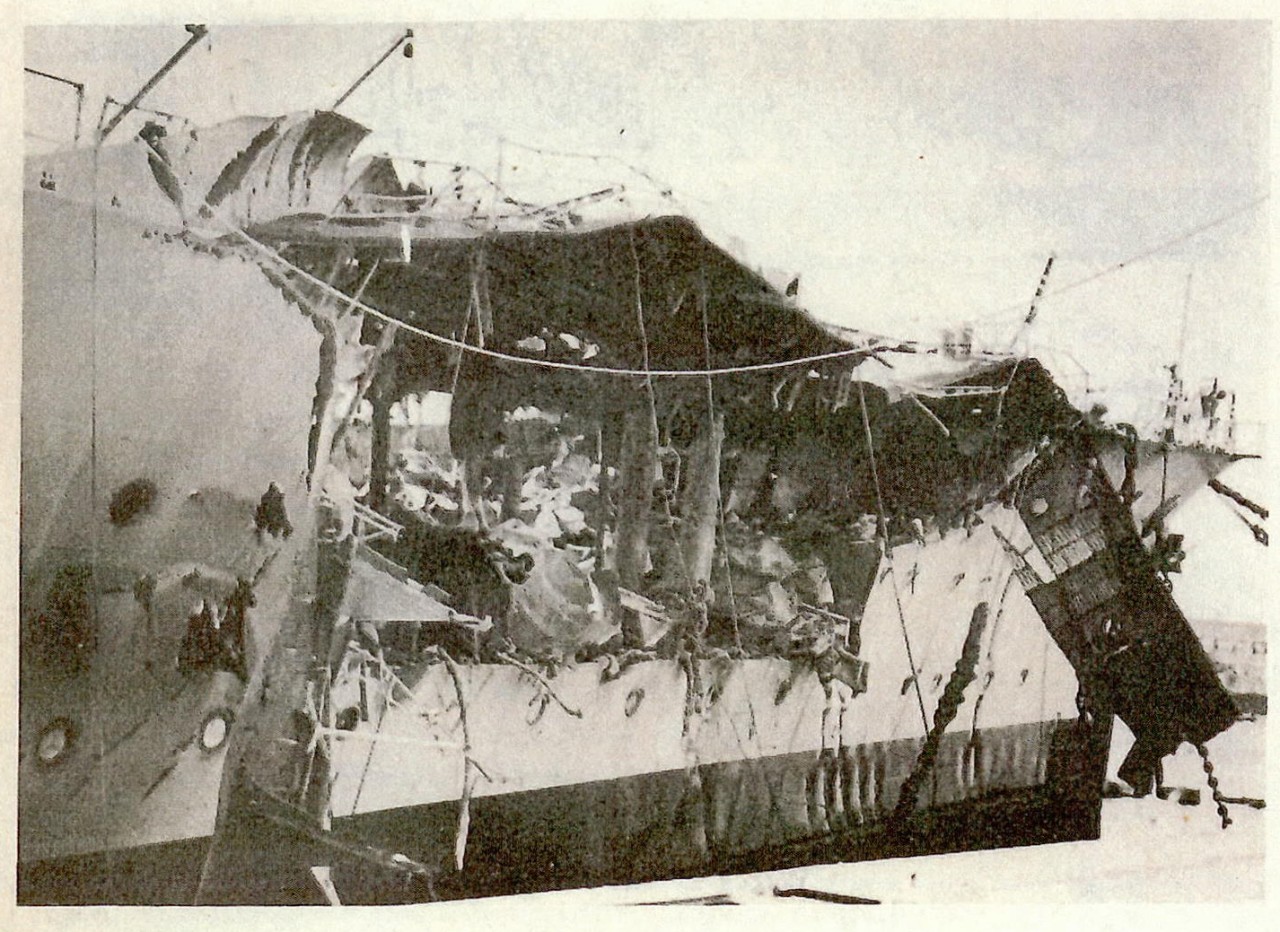

Charts: Bombardment of Casablanca Illustrations: Damage to the Jean Bart, bow Damage to the Jean Bart, stern |

24 |

Chart: Naval engagements off Casablanca Illustrations: Wreck of the Frondeur The Primaugent, Albatros, and Milan beached outside Casablanca |

25 |

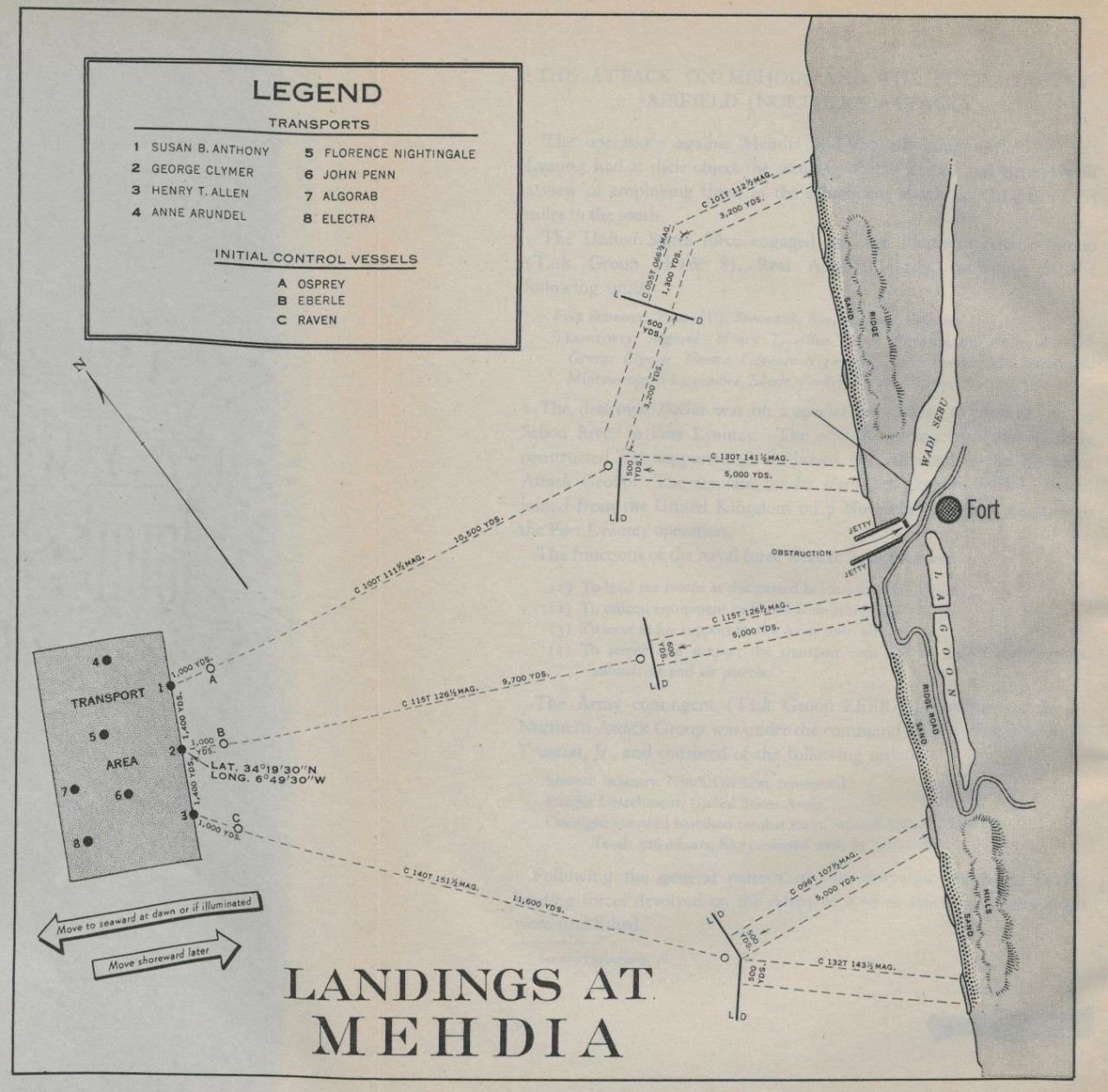

| Charts: Mehdia – the landing plan | 35 |

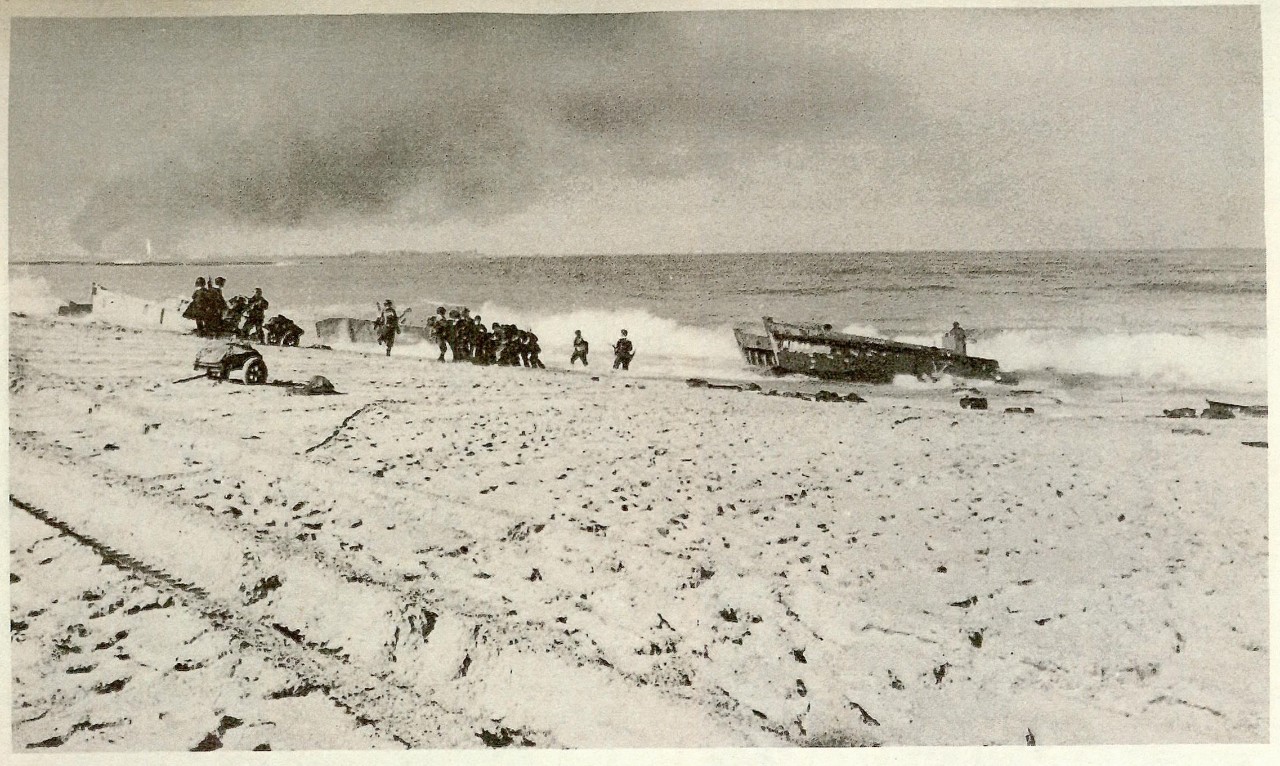

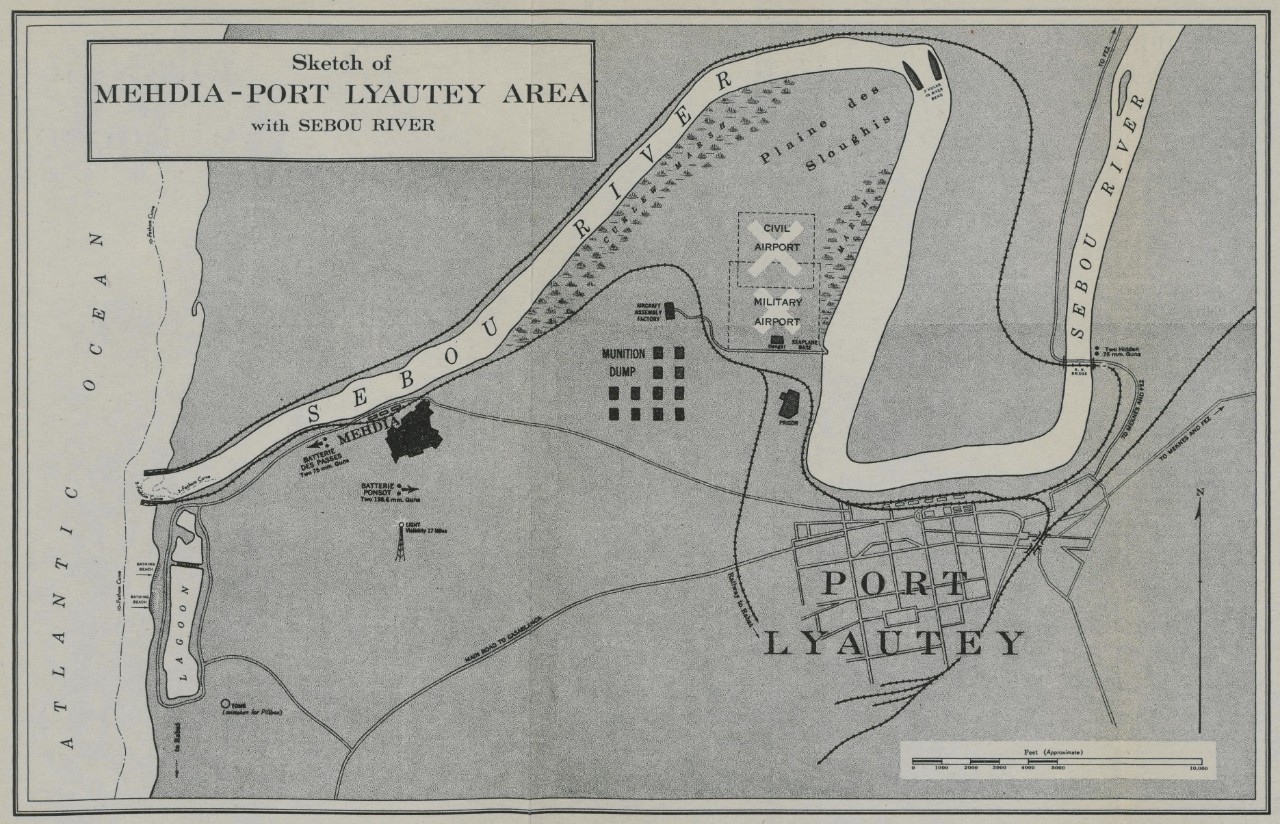

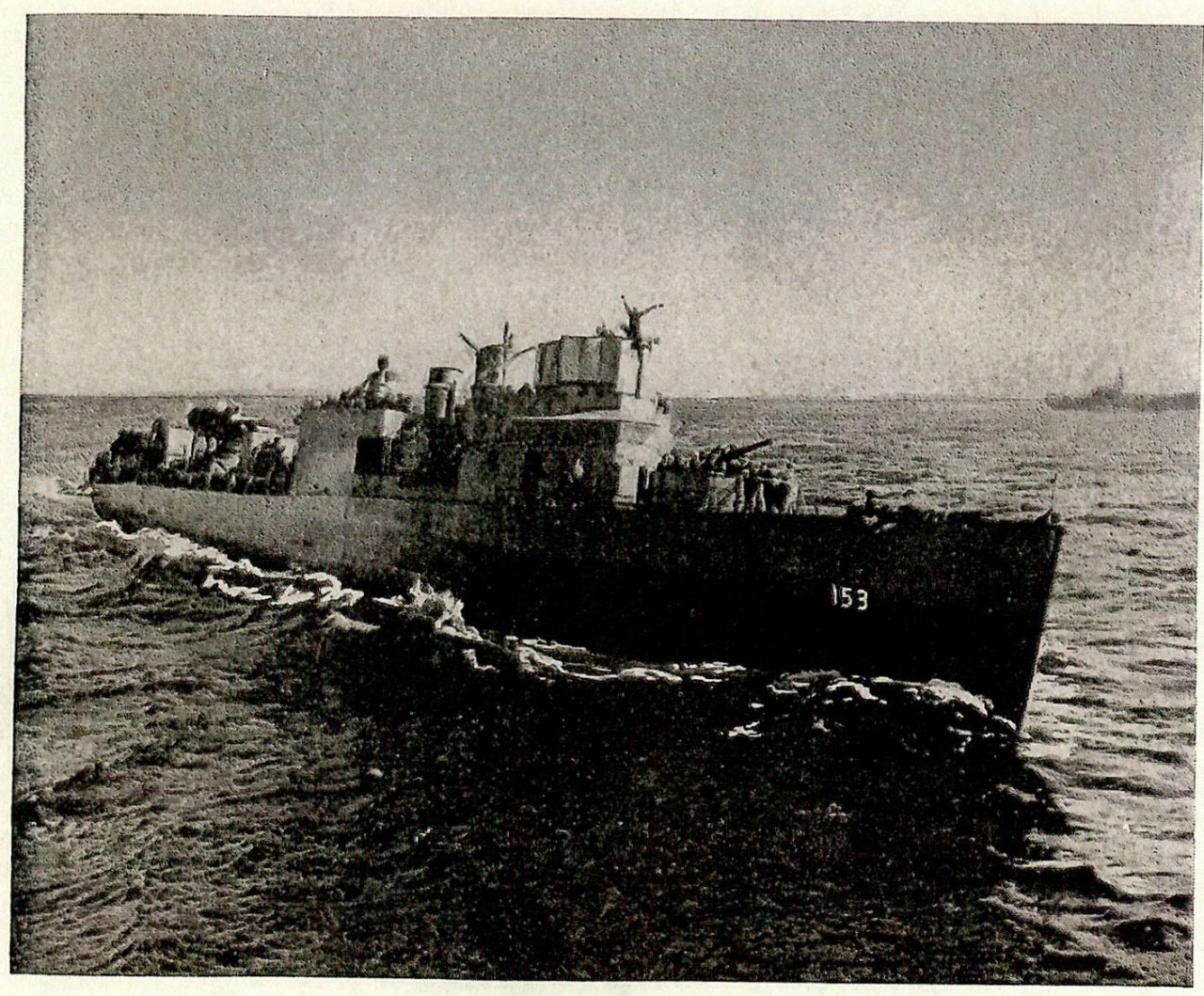

Charts: Sketch of Mehdia and Port Lyautey Illustration: Landing at Fedala |

46 |

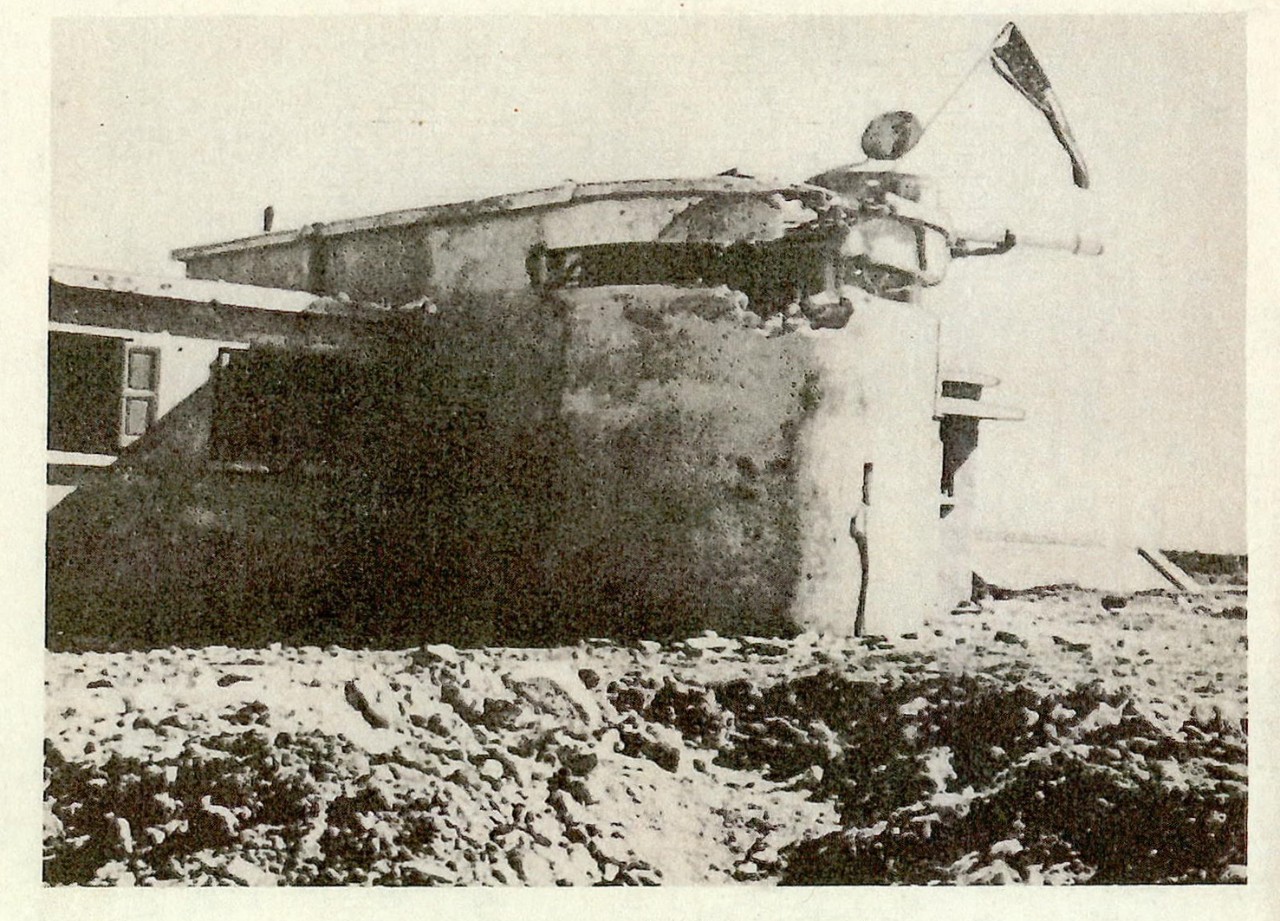

Charts: The attack on Safi Illustrations: Batterie Railleuse, wreck of fire control station Batterie Railleuse, direct hit on storehouse |

47 |

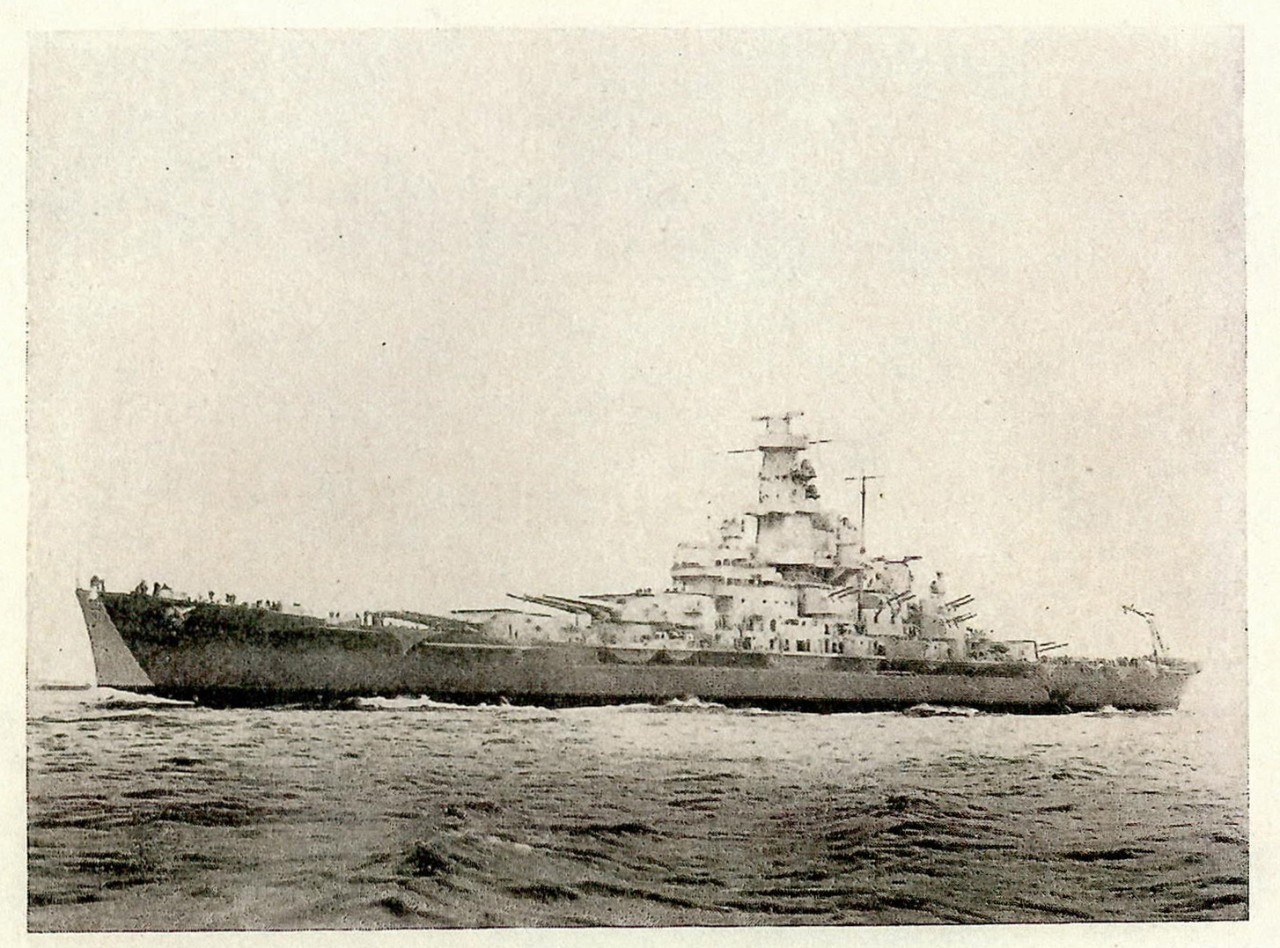

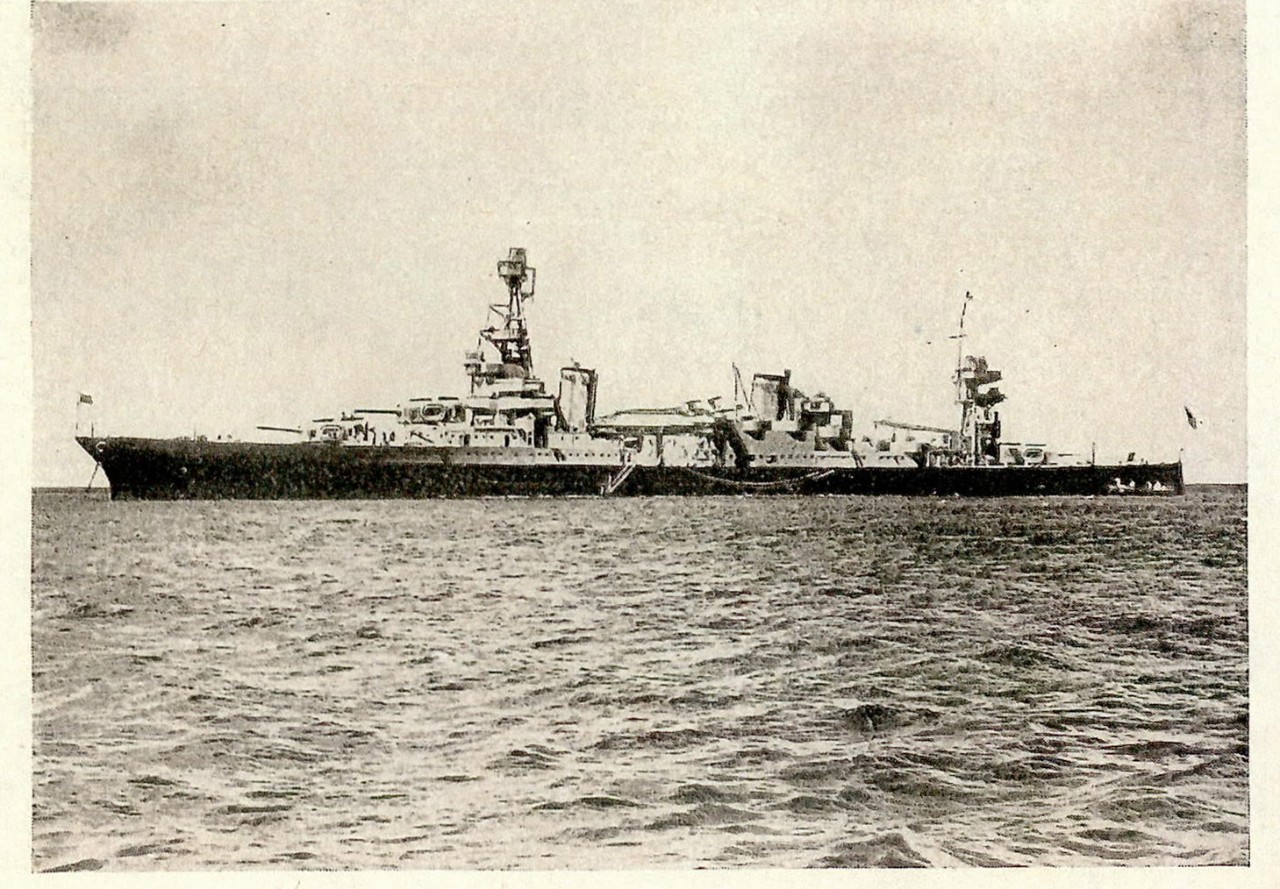

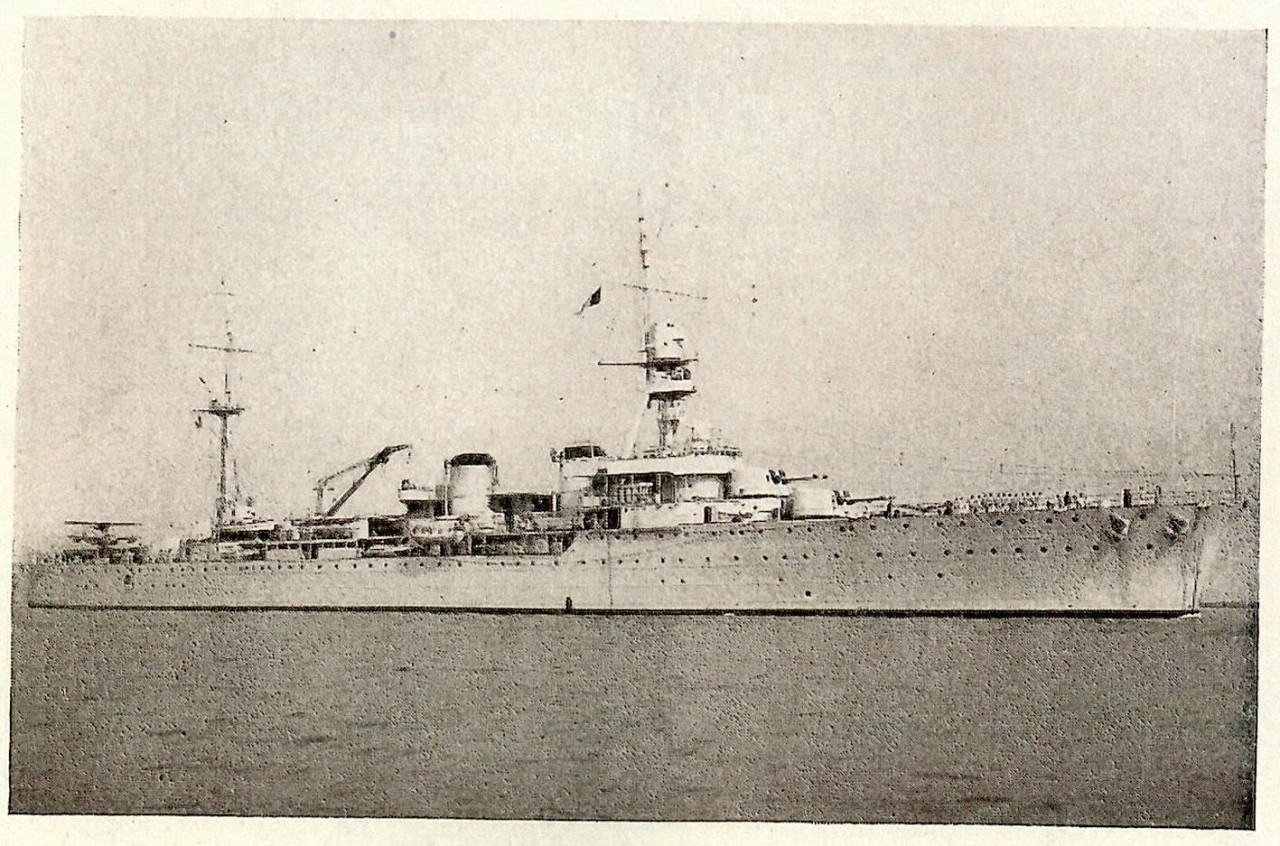

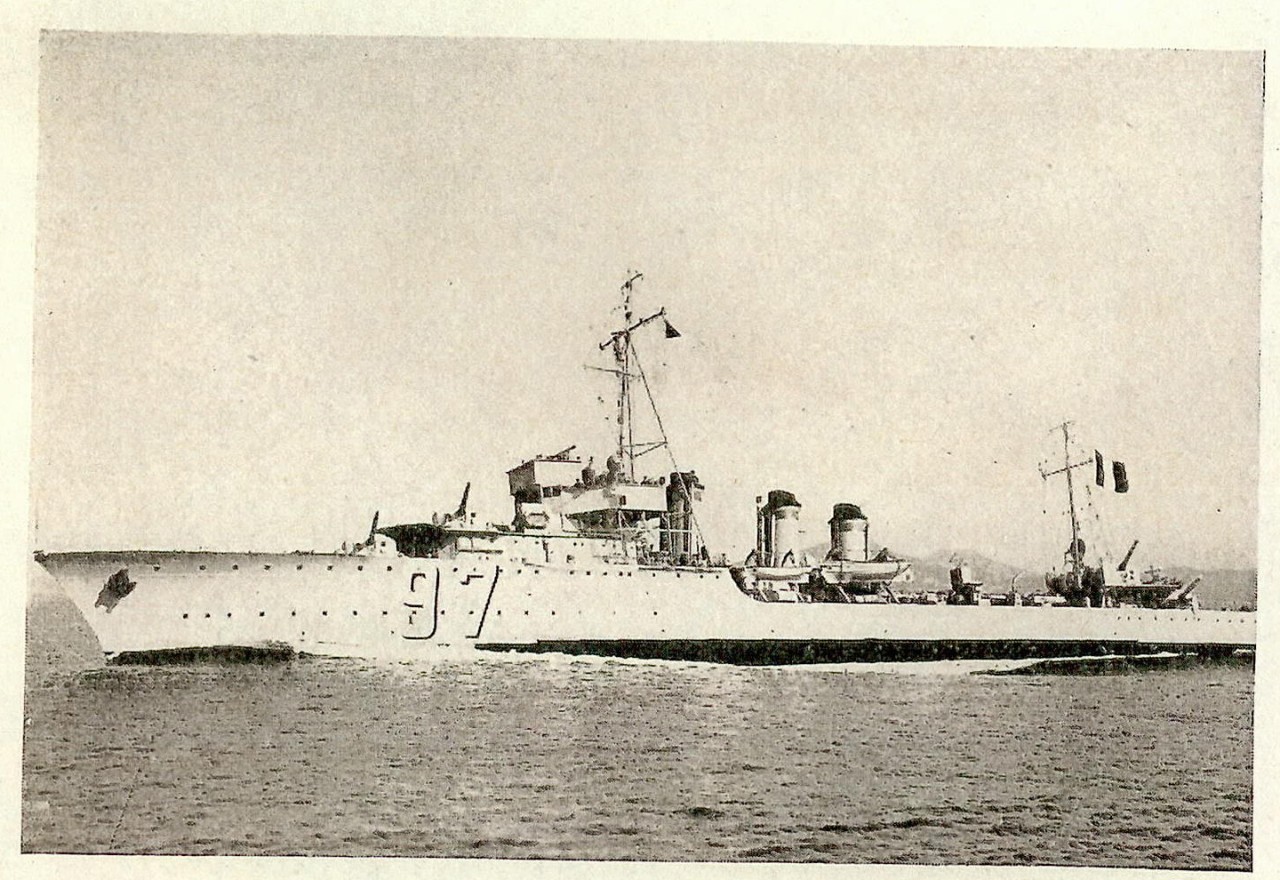

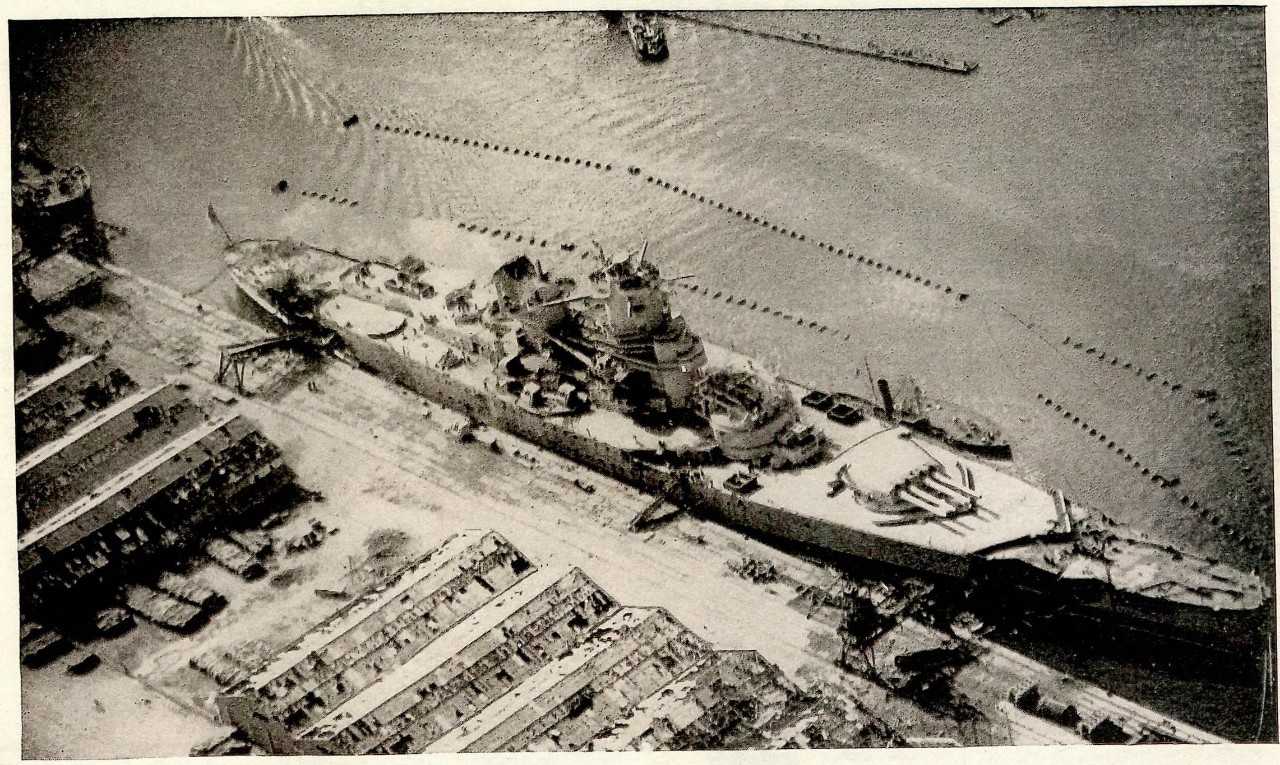

Illustrations: USS Bernadou Wreck of the Méduse USS Massachusetts USS Augusta The Primauguet The Brestois The Jean Bart brethed at the Môle du Commerce |

49 |

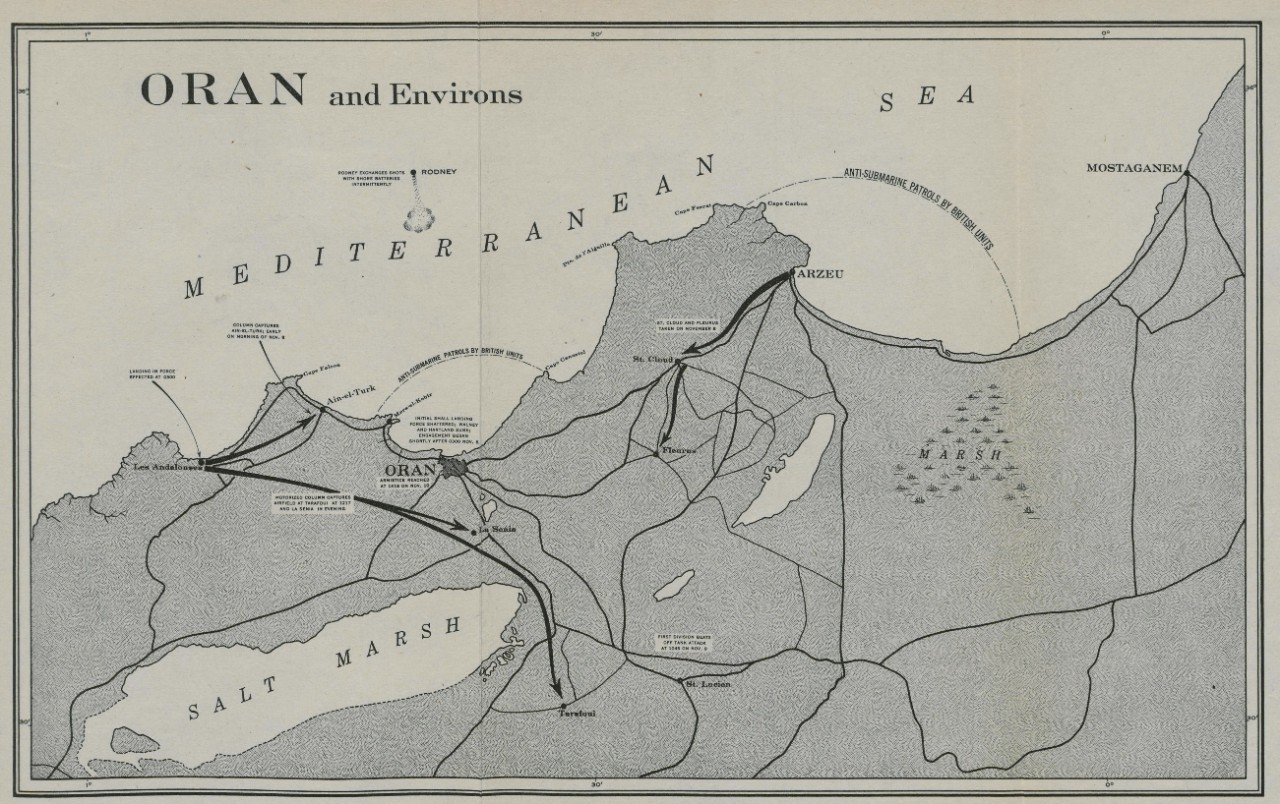

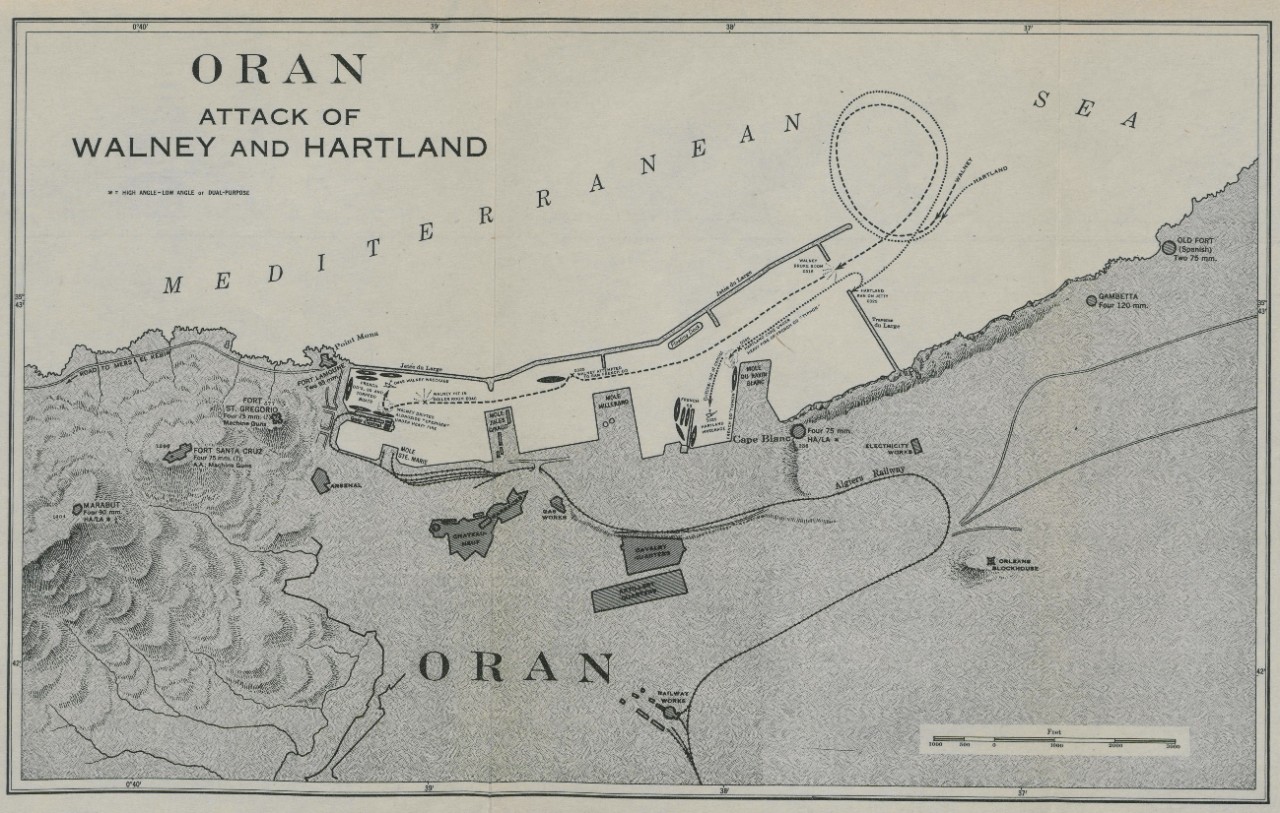

Charts: Oran and environs Illustration: Oran viewed from Santa Cruz |

64 |

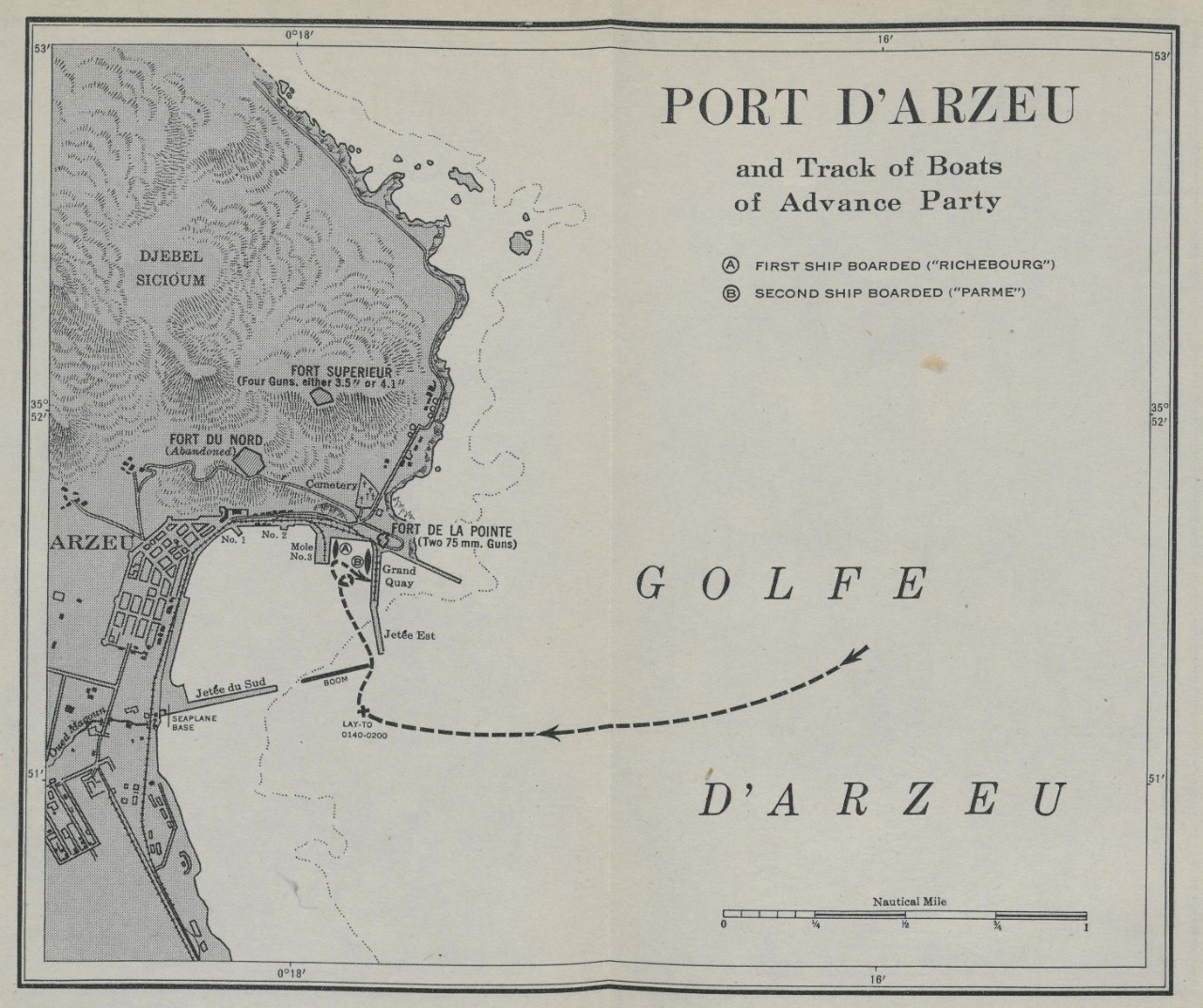

Charts: Port of Arzeu Illustration: Airplane view of Arzeu |

65 |

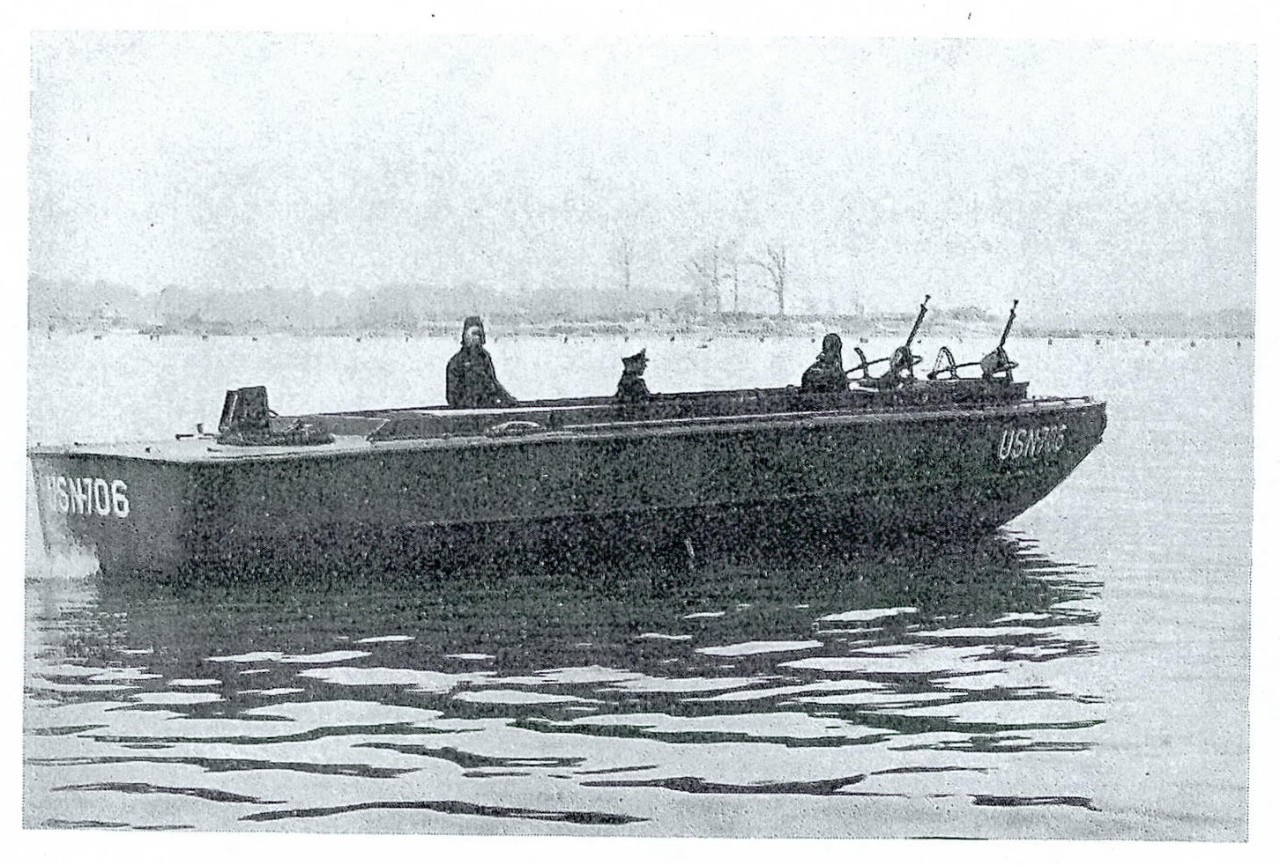

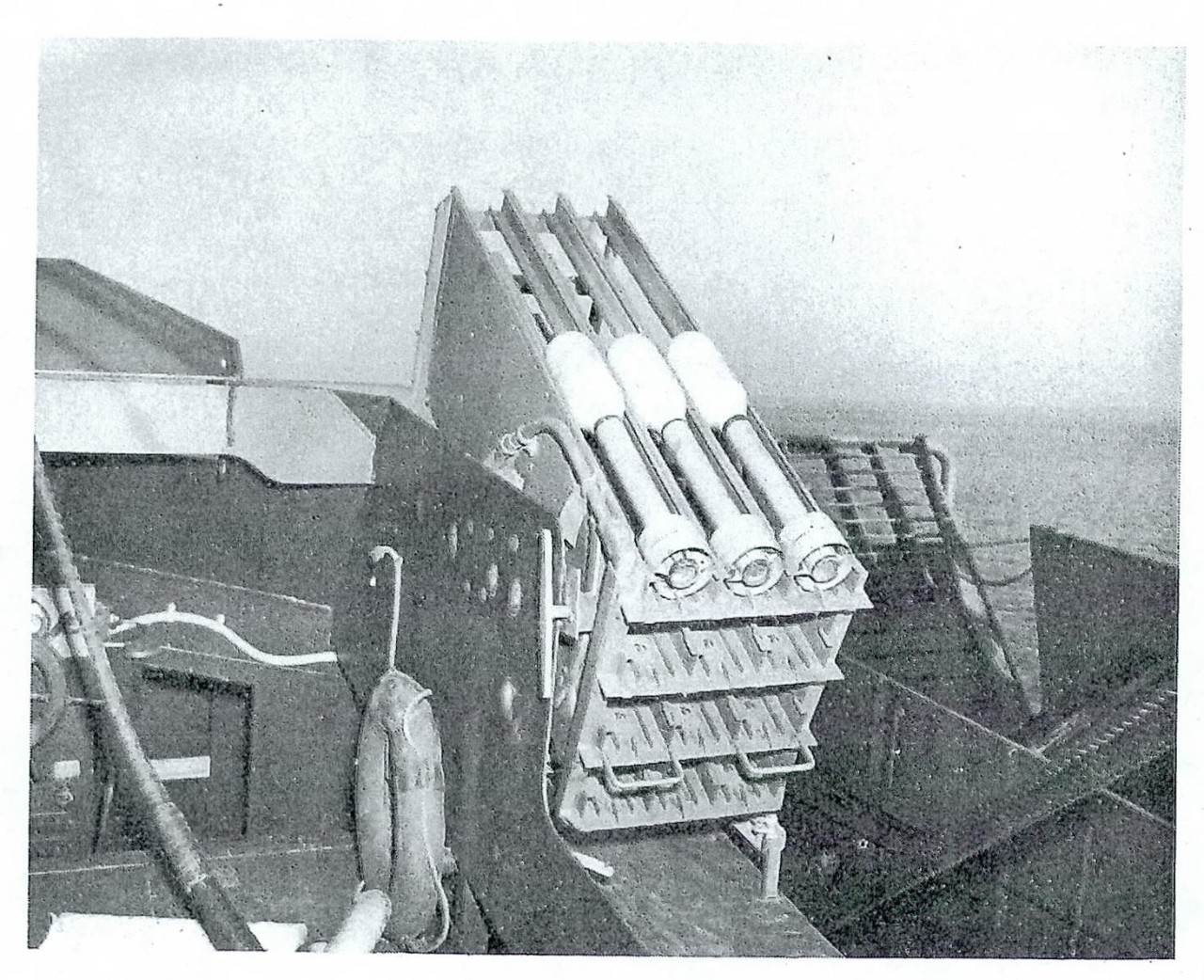

Charts: Track of Walney and Hartland Illustrations: LCP(L) with armament LCS with rocket racks |

70 |

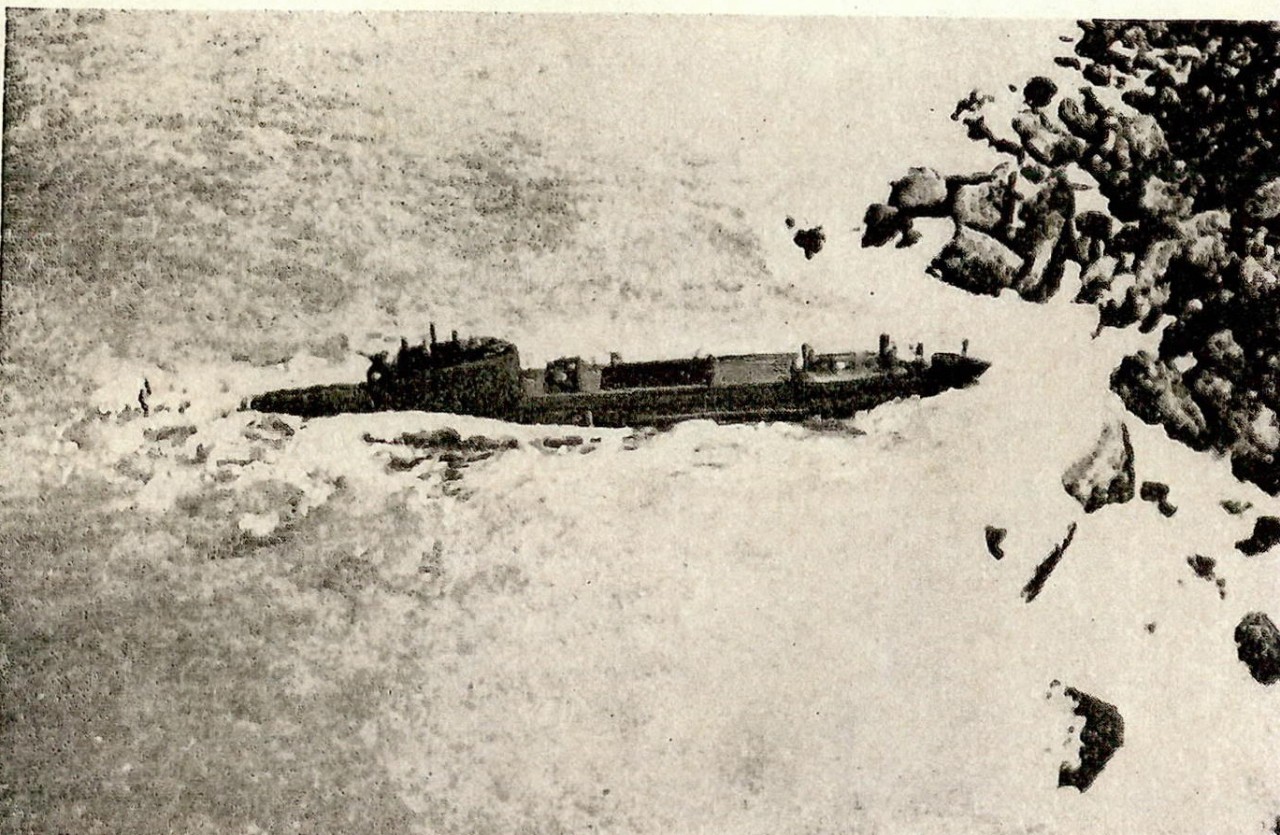

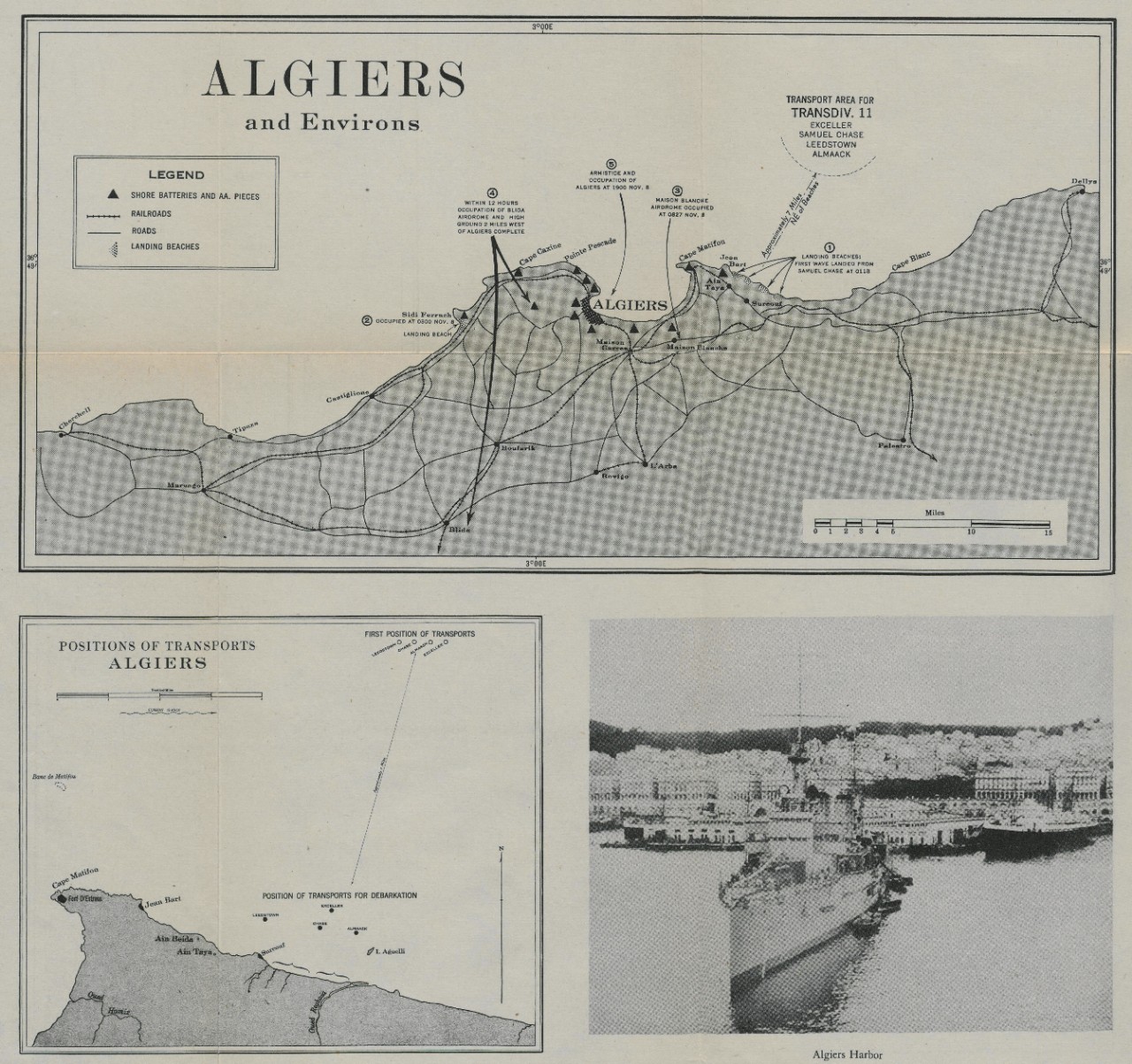

Charts: Algiers and environs Position of transports, Algiers Illustrations: Algiers Harbor Stranded landing craft (Fedala) Broached landing craft (Fedala) |

71 |

Contents

| Page | |

| The landings in North Africa | 1 |

| The Moroccan expedition | 6 |

| Characteristics of the coast | 7 |

| Fixed defenses | 8 |

| Mobile defenses | 10 |

| The French naval forces | 11 |

| Organization of the United States Amphibious Force | 11 |

| Departure | 13 |

| The Atlantic crossing | 15 |

| The Battle of Casablanca | 19 |

| The attack on Mehdia and the Port Lyautey airfield | 34 |

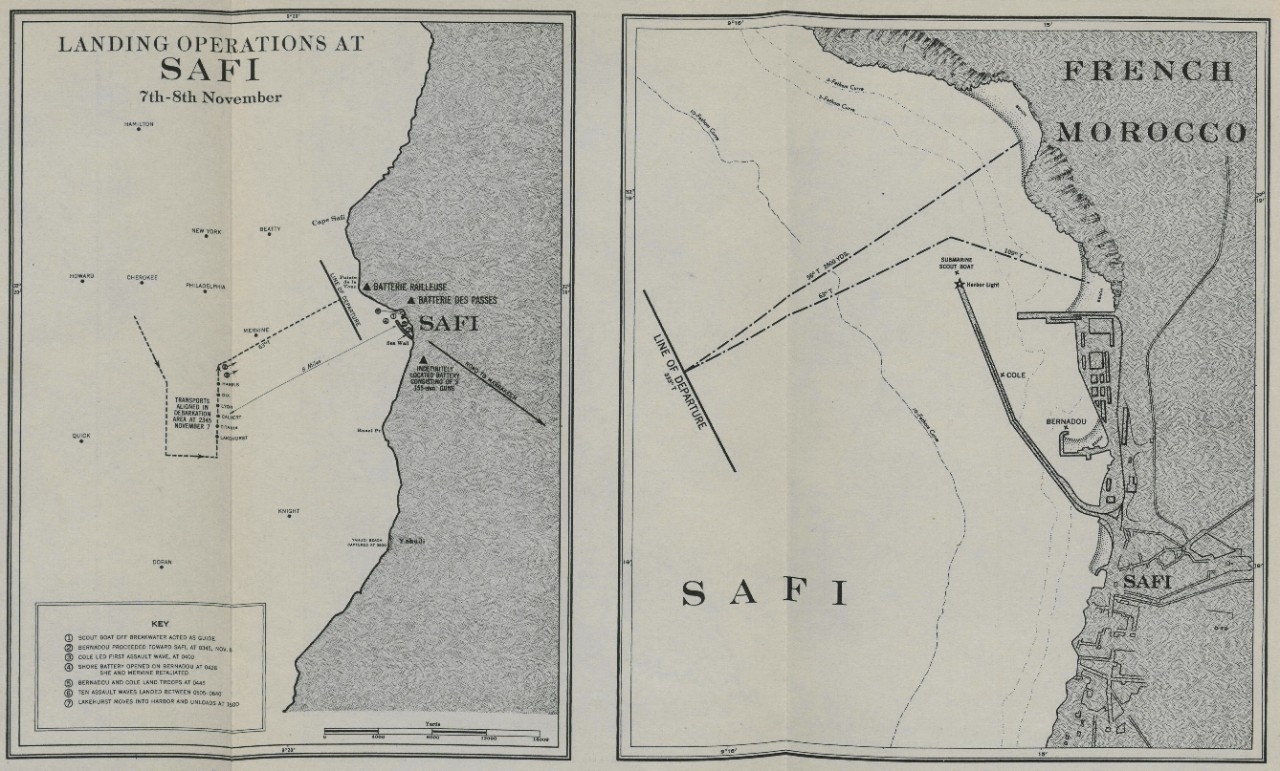

| The attack on Safi | 46 |

| Attach on Fedala | 55 |

| The Algerian expedition | 61 |

| The attack on Oran and Arzeu | 62 |

| The attack on Algiers | 70 |

| Conclusion | 78 |

| Appendix I. Task Force HOW | 79 |

| Appendix II. Designations of aircraft mentioned in Narrative | 84 |

V

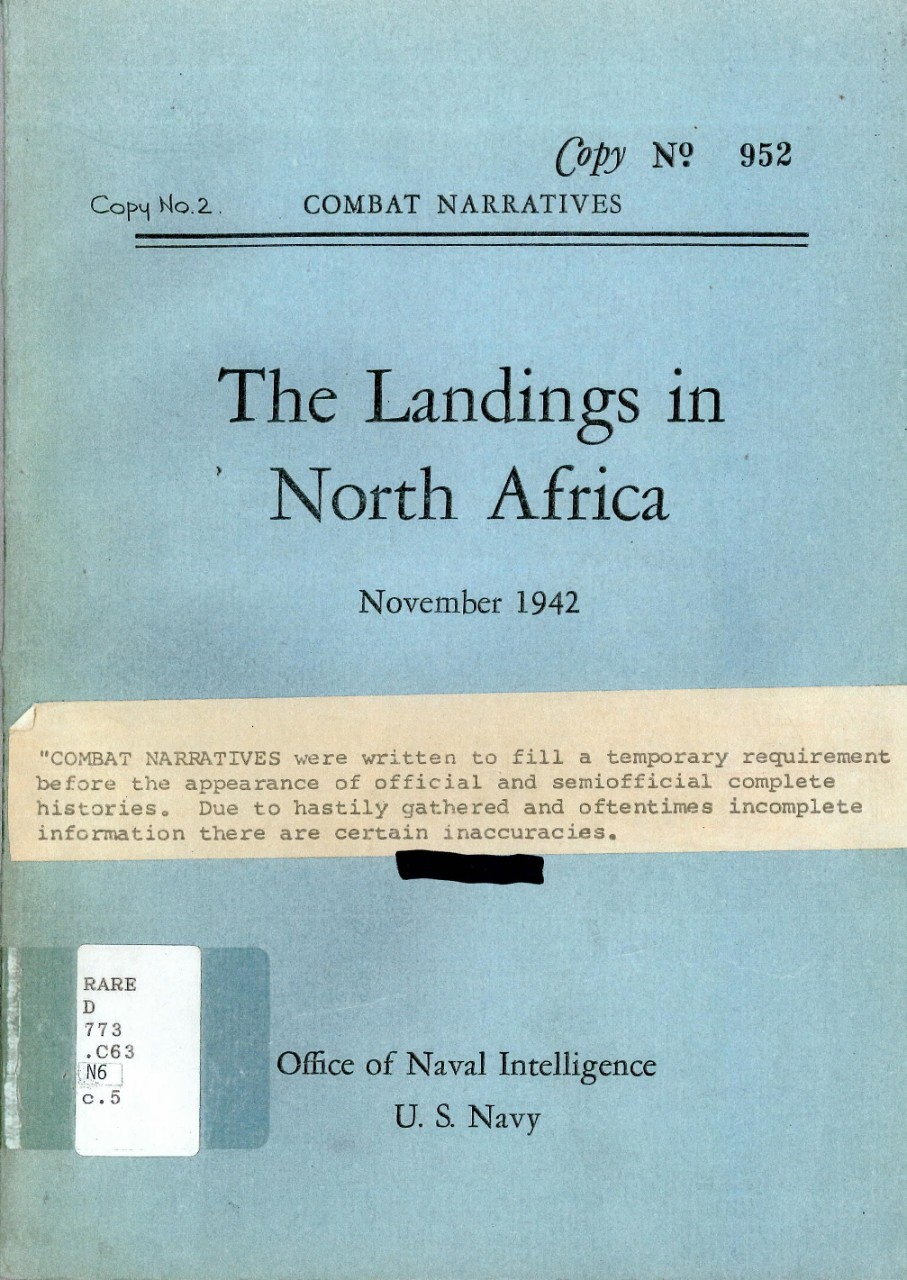

0-44-566293 Faces p. I

The Walney and Hartland entering Oran (reproduction of painting by eyewitness)

The Landings in North Africa

November 1942

In order to forestall an invasion of Africa by Germany and Italy, which, if successful, would constitute a direct threat to America across the comparatively narrow sea from western Africa, a powerful American force equipped with adequate weapons of modern warfare and under American command is today landing on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of the French colonies in Africa. “The landing of this American army is being assisted by the British Navy and Air Forces, and it will in the immediate future be reinforced by a considerable number of divisions of the British Army.

“This combined Allied force, under American command, in conjunction with the British campaign in Egypt, is designated to prevent an occupation by the Axis armies of any part of northern or western Africa and to deny to the aggressor nations a starting point from which to launch an attack against the Atlantic coast of the Americas.

“In addition, it provides an effective second front assistance to our heroic allies in Russia.”

With these few words President Roosevelt announced the landing of American troops on African soil on Sunday, 8 November 1942.

This announcement to the American people was accompanied by one in French, broadcast in the early hours of 8 November, of which the English translation is as follows:

“My friends, who suffer day and night under the crushing yoke of the Nazis, I speak to you as one who was with your army and navy in France in 1918. “I have held all my life the deepest friendship for the French people- for the entire French people. I retain and cherish the friendship of hundreds of French people in France and outside of France. I know your farms, your villages and your cities. I know your soldiers, professors and workmen. I know what a precious heritage of the French people are your homes, your culture and the principles of democracy in France.

“I salute again and reiterate my faith in liberty, equality and fraternity. No two nations exist which are more united by historic and mutually friendly ties than the people of France and the United States.

“Americans, with the assistance of the United Nations, are striving for their own safe future as well as the restoration of the ideals, the liberties, and the democracy of all those who have lived under the tricolor.

I

“We come among you to repulse the cruel invaders who would remove forever your rights of self-government, your rights to religious freedom, and your rights to live your own lives in peace and security.

“We come among you solely to defeat and rout your enemies. Have faith in our words. We do not want to cause you any harm.

“We assure you that, once the menace of Germany and Italy is removed from you, we shall quit your territory at once.

“I am appealing to you and your realism, to your self-interest and national ideals.

“Do not obstruct, I beg of you this great purpose.

“Help us where you are able, my friends, and we shall see again the glorious day when liberty and peace shall reign again on earth.

“Vive La France éternelle!”

Operations in North Africa long antedated our entry into World War II. They had been limited, however, to Egypt and Libya. Their extension to preclude any Axis action in Morocco had been under discussion by the British high command for some time prior to 7 December 1941. The plan originally contemplated a landing of about 55,000 men in the vicinity of Casablanca. Upon our entry into the war the plan underwent several expansions. It was first enlarged to provide for landing not only near Casablanca but at Mehdia-Port Lyautey and Safi as well. It was thereafter further expanded to include the occupation of the entire North African coast as far as Tripolitania. This occupation would facilitate the safeguarding of Mediterranean convoys, thus enormously shortening the route to the Middle East and saving considerable tonnage previously employed in the route to the Middle East and saving considerable tonnage previously employed in the long passage around the Cape of Good Hope.

The various stages through which the project passed need not be examined. Agreement in principle was readily reached. The United States was to have charge of both the military and naval operations on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. Casablanca, therefore, became an essentially American objective[1]. Oran and Algiers, two cities the occupation of which was contemplated, were to be captured by a joint British and American force, of which the British were to supply all the naval units except a few transports. The landing forces were to be partly American, partly British. Logistics presented a formidable problem, but by July 1942, a plan was formulated providing in detail for an offensive in North Africa under American command, prior to December 1942.

__________

1 Consequently it will be treated more fully than the Mediterranean operations.

2

The strategical purpose of the operations were stated by the Combined Chiefs of Staff to be as follows:

(1) Establishment of firm and mutually supported lodgments in the Oran-Algiers-Tunis area on the north coast, in order that appropriate bases for continued and intensified air, ground and sea operations might be readily available.

(2) Vigorous and rapid exploitation from lodgments obtained in order to acquire complete control of the entire area, including French Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, to facilitate effective air and ground operations against the enemy, and to create favorable conditions for extension of offensive operations to the east through Libya against the rear of Axis forces in the Western Desert.

(3) Complete annihilation of Axis forces opposing the British forces in the Western Desert and intensification of air and sea operations against the Axis on the European continent.

The “concept of United States participation” issued by the Joint United States Chiefs of Staff called the following military and naval forces:

(1) A Joint Expeditionary Force to seize and occupy the Atlantic coast of French Morocco.

(2) United States forces required in conjunction with British forces to seize and occupy the Mediterranean coast of French North Africa.

(3) Additional Army forces as required to complete the occupation of Northwest Africa.

(4) Naval local defense forces and sea frontier forces for the Atlantic coast of French Morocco and naval personnel for naval base maintenance and harbor control at Oran.

(5) The United States to be responsible for logistic support and requirements of all United States Forces.

The directive of the Joint United States Chief of Staff further provided that the United States should furnish the Commander in Chief, Allied Forces. This command was given to Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, U.S. Army, then our Commanding General, European Theater of Operations. General Eisenhower had already established his headquarters in London. He was supplied with a combined United States-British staff. Later Maj. Gen. Mark W. Clark, U.S. Army, was appointed Deputy

3

Commander in Chief. Vice Admiral Bertram H. Ramsay, R.N., was selected initially to be General Eisenhower’s principle naval subordinate but was replaced in mid-October by Admiral Sir Andrew Browne Cunningham R.N., who assumed the title “Naval Commander, Expeditionary Force.” The United States Navy was represented at Allied Force Headquarters by Rear Admiral Bernhard H. Bieri, Deputy Chief of Staff, United States Atlantic Fleet.

The extension of the original British plan to include action on the entire Barbary Coast had wider implications than were involved in the operation’s diversionary effect pm the Russian front. Allied strategy called for the formation and the gradual tightening of a ring around the Axis powers. The northern coast of the Mediterranean was an important segment of that ring and the occupation of French North Africa an essential prelude to the opening of a second front on the European continent. At the same time, countermeasures by the Axis would be forestalled.

That Germany might attempt to send forces across the Straits of Gibraltar was a possibility that could not be ignored. The threat to the South Atlantic area which would result from an Axis penetration into French Equatorial Africa made it imperative that access to that region be denied to our enemies at once. In this respect the attitude of Spain had to be taken into account.

Although not a belligerent, Spain was watching Allied strategy in North Africa with lively interest. Rumors that General Franco might attempt an occupation of French Morocco in the event that Allied forces occupied Dakar had been current for some time. That Spain would not be adverse to enlarging her Moroccan colony was well known, nut her ability to do so without Axis cooperation was questionable. The possibility of an Hispano-Axis bargain was, however, serious enough to render it imperative that sufficient forces be stationed on the French-Spanish Moroccan border to forestall and Spanish move.

As can be seen, the contemplated operations had to be on a very large scale. We were undertaking possibly the most ambitious combined operation in the annals of warfare. Careful preparation and, above all, absolute secrecy were essential if the operation were to be successful at a cost that would not be appalling.

4

The question of how much resistance the French North African colonies would offer was difficult to gauge.

The situation prevailing in the French Navy was a peculiar one. French naval officers have for generations been chosen largely from certain families, most of whom are Bretons and avowedly royalist. The traditions of “Grand Corps” are still very much alive. As a result French naval officers are inclined to think more in terms of the service than of the nation. The enlisted men, who like their superiors are mostly Bretons, have long been accustomed to follow the lead of their officers. Their ambition is to achieve a rating and retire with a pension. In order to do so, an unblemished record for discipline and subordination is necessary. Admiral Darlan was especially popular among the enlisted men because his efforts on their behalf at the time of armistice.

That the rank and file of the French Navy would resent any interference in French affairs, no matter how well intentioned, was a foregone conclusion among all competent observers. The traditional antipathy to the British, the “hereditary enemy” had been revived by the attack on Dakar and Mers-el-Kébir in 1940. British designs on Bizerte were suspected. The fact that Great Britain was now joined by the United States made little difference. It was generally accepted that Anglo-Saxon sea power was opposed to the French colonial system. The determined resistance the French naval units offered at Casablanca- and on the Algerian coast- was in marked contrast to the pro forma resistance offered by the land forces.

The situation in the French Army was slightly different in that it reflected the vies of the average Frenchman. Marshall Pétain was personally popular and his relations with Reich were condoned on the ground that no other course was open to him. The senior officers were as a rule loyal to the Marshal, anxious to make a honorable show of resistance and inclined to be antiforeign. The junior officers and enlisted men, however, were inclined to look favorable on the Unites States. For this reason it was deemed advisable throughout the entire French African campaign to stress the American complexion of the expedition.

The government officials as a class were resentful of all interference and concerned about their salaries and pensions. The civil population was neutral and mainly interested in bettering its economic condition. The natives, including the indigenous troops, were apathetic.

Generally speaking it may be said that in North Africa, France was a

5

“house divided,” in which respect it reflected the political situation in European France.

The occupation of French North Africa was accomplished by means of simultaneous assaults on Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. General Eisenhower exercised command over all elements of the three attacking forces, with the exception of the permanent British naval units in the Mediterranean. These remained under the control of the British Admiralty.

Geographically the three operations fall into two regions based on the seas to which they are related. From a military point of view those in the Mediterranean were primarily British and designed to supplement somewhat the British land operations proceeding from Egypt. On the other hand, the attack from the Atlantic to a certain extent owed its inception to the strategic needs of hemispheric defense. For purposed of clarity the Moroccan and Algerian expeditions will therefore be considered separately.

THE MOROCCAN EXPEDITION

In the Moroccan expedition the naval component was known as the Western Naval Task Force and was under the command of Rear Admiral Henry K. Hewitt, U.S.N. The Army component was known as the Western Task Force and was under the command of Maj, Gen. George S. Patton, U.S. Army. The mission assigned to the Naval Task Force was:

“To establish the Western [Army] Task Force on beachheads near Mehsia, Fedala and Safi, and support the subsequent coastal military operations in order to capture Casablanca as a base for further military and naval operations.”

The principle objective of the expedition was therefore the harbor of Casablanca, modern seaport on the Atlantic protected by an adequate breakwater and processing docks and other facilities. To accomplish the task it was considered advisable to occupy simultaneously three other harbors. The most important of these was Fedala, situated 14 miles northwest of Casablanca. Secondary landing places which were deemed necessary for the success of the operations were Mehdia, 65 miles north of Casablanca, and Safi, 125 miles south of Casablanca. The object of landing at Fedala and Safi was to facilitate the capture of Casablanca

6

from the land side. Mehdia was occupied because of the adjoining airfield at Port Lyautey.

Although capable of being expressed in a few lines, the mission assigned to the Western Naval Task Force presented serious difficulties.

Characteristics of the coast.

The coast of Morocco is generally rocky with occasional long shelving beaches which require transport to lie a considerable distance from the shore. Rocky outcrops add to the difficulties of making safe landings. The number if possible landing places is relatively limited. Fully navigable rivers are nonexistent. Such harbors as exist are artificial. Intelligence reports, however, indicated that several practicable beaches were located in the vicinity of the ports to be occupied.

The beaches are subject to heavy ground swells, high surf, and a considerable tidal rise and fall which render debarkation operations extremely difficult[2]. A swell of 16 feet, which in breaking doubles in high, is not uncommon. Very high surf and swell are frequently observed in spite of fair local weather. Low pressure over the Azores moving towards southern Spain will cause a heavy surf off Morocco in about one day. A depression passing south of Iceland, on the other hand, will not be felt until 2 or 3 days later. The worst swell and surf, however, result from a depression in the area between Bermuda and Newfoundland. After a lag of about 36 hours, surf, accompanied by gale winds, may be expected along the Moroccan coast. The chances of these disturbances naturally increase with the approach of winter weather. In view of the late date chosen for the North American expedition the meteorological factor was one of the utmost importance. In fact, immediately after the debarkations a surf developed which, had it occurred a day or two sooner, would have immeasurably increased the hazards of the landing.

Predictions require the continuous study of meteorological conditions over the entire Atlantic. The efficiency of the metrological service of the Navy contributed in no small degree to the success of the undertaking. In order that no source of information be neglected, five beacon submarines were dispatched to the Moroccan coast two days ahead of the main

__________

2 One of the probable reasons why our landings on the Moroccan beaches met with such light opposition was the fact that the French did not believe a landing through the surf possible and were expecting attacks on more sheltered spots, such as harors or, in the case of Media, a beach along the Sebou River.

7

body. Among their duties was the prompt reporting of meteorological conditions.

Fixed defenses

Although the French fortification plan was far from completed. The coastal area was protected by numerous fixed defenses. These consisted of (a) naval coast defense batteries, (b) emplaced army field artillery, (c) army or naval antiaircraft batteries, and (d) machine guns, usually mounted in pill boxes. The exact location and nature of all these batteries were not known in advance. The intelligence reports, however, proved remarkably accurate. Such slight inaccuracies as were discovered will be mentioned in dealing with operations. The defenses reported were as follows:

Mehdia.[3] – This town, situated at the mouth pf the Sebou River on the southern bank, had been fortified with two batteries. One, known as the Batterie Ponsot, consisted of two 138.6-mm. guns and was located halfway between the Kasba (walled native quarter) and the lighthouse. It commanded all sea approaches to the Sebou River. Estimated range: 18,000 meters. Another battery, known as the Batterie does Pases, consisted of two 75-mm. guns and was located on the river’s edge below the Kasba.

Fedala[4].- This village, mainly a pleasure resort, 12 miles northeast if Casablanca, had been fortified with four batteries. (a) The Batterie Port Blondin was located at Chergui about 3 miles northeast of the harbor of Fedala. It consisted of four138.6-mm. Estimated range: 18,000 meters. (b) The Batterie du Port, located just southwest of where Cape Fedala starts to jut out, consisted of two 100-mm. guns with an estimated range of 14,000 meters. It dominated the small harbor of Fedala. (c) The Batterie des Passes, consisted of two 75-mm. guns, was located on the tip of Cape Fedala. (d) An army antiaircraft battery of four 75-mm. guns was located just south of the village alongside the railroad tracks.

Casablanca area[5].- At the Table d’Aukasha, a headland about 5 miles northeast of Casablanca, a battery of four guns had been mouthed. These were reported to be either 164.7-mm or 138.6-mm. guns. Three miles southwest of Casablanca the El Hank promontory juts out into the Atlantic. Here two batteries had been mounted. Battery No. I consisted of four

__________

3 See charts opposite pp. 19 and 35.

4 See charts opposite pp. 24 and 25.

5 See charts opposite pp.24 and 25.

8

194-mm. guns aligned northeast and southwest to the west of Point El Hank lighthouse. Battery No. 2 consisted of four 138.6-mm. guns spread in a line between Battery No. I and the tip of the point. These two batteries were formidable. The former was said to have a range of at least 23,500 meters, the latter a range of about 18,000 meters. The guns were mounted on a central pivots and could be trained both east and west. The fire control and magazines were modern.

Casablanca Harbor[6].- The harbor of Casablanca is formed by two jetties located at right angles to each other, the Jetée Delure and the Jetée Transversale. The former extends along the ocean in a northeasternly directions for a distance of 2,600 meters. The entrance to the inner harbor is close to the 1,500 meter point on the Jetée Declure, opposite the end of the Jetée Transversale. The area thus enclosed is approximately bisected by a spacious wharf, the Môle du Commerce. The outer harbor is formed by the coast, the Jetée Transversale and the portion of the Jetée Delure projecting beyond the entrance to the inner harbor. Two rocky outcroppins located near the coast about 1,300 meters from the Jetée Transversale are within the red sector of the Roches Noires lighthouse.

The harbor area had been fortified with air raid protection mainly in view. On the Jetée Delure, at the 1,000 meter point, a battery of four 40-mm. AA guns had been installed. Further along, at the 1,700 and 2,100 meter points, blockhouses had been constructed. They were believed to contain 37-mm. and 13.2-mm. machine guns. On the spur extending toward the Jetée Transversale four 13.2-mm. AA machine guns had been mounted. At the angle formed by the Jetée TRansversale and the shore two batteries had been mounted, each equipped with a searchlight. The westerly battery was believed to contain four 75-mm. AA guns, the easterly battery four 13.2-mm. AA guns. On the end of the Jetée TRansversale a bettery of two 75-mm. guns and one 13.2-mm. AA gun had been mounted. On the roof of the adjoining Phosphate Building another battery of four 13.2-mm. AA guns in towers had been erected.

The uncompleted battleship Jean Bart, moored at the southeastern end of the Môle du Commerce heading northwest, may be considered as part of the fixed defenses of Casablanca. Her normal armament consisted of eight 15-inch guns in two turrets (range 35,000 yards) of which only four had been installed, fifteen 6-inch guns, of which only five had been

__________

6 See charts opposite pp. 24 and 25.

9

installed, twelve 37-mm. guns and twenty-four 13.2-mm. AA machine guns.

Safi.[7]- The harbor of Safi had been fortified by two Navy coast defense batteries, the Batterie Railleuse and the Batterie des Passes.

The Batterie Raileuse was located on the Pointe de la Tour, a promontory jutting our into the Atlantic 2 ¾ miles northwest of Safi. Here the French had placed four 130-mm. guns on circular concrete emplacements. Estimated range: 19,000 yards; estimated rate of fire: 8 rounds per gun per minute. The fire of this battery was controlled by a fire control station equipped with a modern range finder. Four .50-caliber AA machine guns had also been mounted.

The Batterie des Passes consisted of two 75-mm. guns and was situated about 2,000 yards north of the city.

About 2 miles south of Safi an army battery had been emplaced. It consisted of three 155-mm. guns. Its exact location was not determined until operations began.

Other fixed defenses need not be considered as they played no appreciable part in the operations.

Mobile Defenses

The fixed defenses of the Moroccan coast were supplemented by mobile defenses drawn in Morocco was 13 infantry regiments, 8 cavalry regiments,[8] and 4 artillery regiments plus 3 batteries. The exact composition of the French land forces need not detain us.[9] Suffice to say these forces were variegated, colorful, and picturesque and could undoubtedly have put up a stiff resistance had they so desired. The only ones to do so were the professional soldiers of the Foreign Legion.

The artillery consisted of two regiments of African artillery, two regiments of Colonial artillery and three batteries of the Foreign Legion. Most of the field pieces were 75’s, but some were 65’s. In addition there was one regiment of antiaircraft artillery. These mobile units caused considerable trouble by compelling our transports to keep well out of range and by contesting the advance of the landing parties. They frequently

__________

8 The famous Chasseurs d’Afrique have been motorized.

9 A French infantry regiment normally consists of 3,120 men, a cavalry regiment of 1,140 men, an artillery regiment of 1,683 men. The strength of batteries varies. The 75’s usually have 98 men to a battery, the 105’s 108 men. The motorized batteries of 75-mm. guns muster about 170 men.

10

bolstered the fixed defenses by taking positions in emplacements usually prepared in advance. Owing to their mobility- some were motorized, others were horse-drawn- their location could not be determined beforehand.

The French air forces in Morocco were too inconsiderable to be able to affect operations. The total number of planes, both Army and Navy, in the area was estimated at 168. During the landing operations at Fedala and Mehdia some Italian planes were identified among those strafing the beaches. In addition to the air base at Port Lyautey, numerous air fields were scattered throughout Morocco, weakly defended by antiaircraft units.

The French naval forces

Intelligence reports credited the French with the following vessels based on Casablanca.

Jean Bart, battleship 1

Gloire, Primauguet, light cruises 2

Albatros, Le Malin, Milan,[10] flotilla leaders 3

Alcyon, Brestois, Fougueux, Frondeur, Simoun, Tempête, destroyers 6

Actéon, Archiméde, Aurote, Céres, Conquérant, Iris, Méduse,

Orphée, Pallas, Psyché, Tonnant, Vénus, submarines 12

Boudeuse, sloop 1

This list, except for some unimportant errors in names, proved substantially correct.[11]

These vessels, with the exception of the Jean Bart, were in full commission and fully manned. Well-trained, well-equipped, thoroughly disciplined and the leadership is energetic and able,” is how one report summed up the situation.

ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED STATES

AMPHIBIOUS FORCE

The organization of the Amphibious Force command by Rear Admiral Hewitt, designated Task Force HOW[12], varied at different

__________

10 Considerable confusion has crept into the reports due to the similarity of these last two names.

11 By the time our forces reached Casablanca, the Gloire and one submarine had been detached, one destroyer and two sloops added.

12 Numbers identifying task forces have been omitted from all Combat Narratives in the interest of security. Navy flag names for the first letter of surnames of commanding officers have been substituted.

11

times as the operations progressed. Roughly speaking, the Task Force went through three states: (a) departure, (b) passage, (c) attack, the details of which will be found in Appendix I. The basic idea was the formation of a Covering Group to contain the French Fleet at Casablanca and, if necessary, the French units at Dakar, while three Attack Groups effected landings at Mehdia, Fedala, and Safi.

The expeditionary force which participated in these operations was built around two Army divisions, the Sixth and the Ninth. Both were reinforced by special detachments. This force was command devolved as soon as satisfactory beachheads were established.

Care had been taken to make this force as letter-perfect in amphibious operations as circumstances permitted. The doctrine adopted by the United States Army was the result of tests conducted for a period of 3 years prior to the North African campaign. The unit chosen for these maneuvers was the First Division, United States Army.[13] During the winter of 1939-40 this division began its experimental work at Culebra Island, Puerto Rico, and continued it in northern waters. Gradually evolving principles which form the “basic training” of the Army.

Briefly stated, the basic training, besides thorough physical conditioning, involved instruction in such details as the protection of critical items such as gas masks, rifles, and ammunition wile wading through surf, and the manner in which safe landings from boats to shore can be made. All Army contingents forming part of the Task Force had received this training prior to reporting to the transports. Whenever possible, as in the case of the Third Division which had been trained on the West Coast, this training was undergone on actual beaches. When this was not possible, a simulated landing was made. Automobiles riding over artificially undulating ground took the place of small boats. Beaches marked off were then occupied and unloading operations performed with as much realism as practicable.

Once at Hampton Roads the units were placed on transports and sent up Chesapeake Bay to Solomon Islands, where they remained on an average of 3 weeks performing actual landings. The training usually included three “dress rehearsals.”

__________

13 This division constituted the U.S. Army contingent in the Mediterranean landing which will be considered presently.

12

The system adopted was undoubtedly the best that could be devised. It was deficient, however, in one important respect. No surf could be devised. It was deficient, however, in one important respect. No surf comparable to that encountered on the Moroccan coast was available. The heavy loss of landing craft which was the cause of so much trouble and anxiety had not been taken into consideration. No doctrine of boat salvage was perfected.[14] The North African landings had been scheduled perilously near the season of winter storms. In fact, one broke right after our landings were completed. Our unpreparedness to meet the meteorological risk was such that our avoidance of a costly failure has been described by many officers who participated as “providential.”

DEPARTURE

The shipping problem was a difficult one. The Army contingent to be transported amounted to 1,920 officers and 35,385 men. The equipment and material were in proportion. Space had to be provided for 250 tanks. The landing craft were bulky and numerous. On 1 June 1942, there were but 8 ships assigned to and operating with the Amphibious Force, United States Atlantic Fleet. This number was gradually increased by assignment of newly constructed vessels, by the transfer of 5 ships from the West Coast and by the conversation of 11 ships during August and September, with the result that by 1 October 26 transports and 7 cargo ships had been assembled at Hampton Roads.

By 23 October loading operations were completed and the Task Force organization was put into effect. In order to avoid congestion, the Covering Group was dispatched to Casco Bay and the Air Group to Bermuda just before the main body sailed. The departure from the United States was set for 2 successive days. Detachment ONE, consisting of units assigned to the Mehdia and Safi landings, began threading its way through the swept channel at Hampton Roads about 1000 on 23 October.

Detachment TWO, consisting of units intended for Fedala landings,

__________

14 “Boats that had been broached were abandoned at the critical time when a little judgement might have saved them, and having been abandoned to the mercy of the surf, soon were hopelessly battered to pieces. No doctrine had been laid down nor had men been instructed in the salvage of equipment that was undamaged and still serviceable.

“Two or three men with a few tools could have effectively salvaged enormous quantities of clocks, boat compasses, anchors, fire extinguishers, tools, propellers, etc. As it was, a few machine guns were saved but the lack of transportation facilitates and utter lack of guards to prevent pillaging at night by natives prevented any worthwhile efforts in this line.” (From report of a ranking officer.)

13

sortied 24 hours later. The Covering Force put sea from Casco Bay on 24 October. The air Group, however, did not leave Bermuda until the 25th.

Just prior to sailing, the transport Harry Lee, fully combat-loaded, developed engine trouble. Her commanding officer, Capt. James W. Whitfield, performed the difficult task of transferring men and materials to the Calvert in the remarkably short time of 48 hours. With an escort consisting of the destroyers Boyle (Lt. Comdr. Eugene S. Karpe) and the Eberle (Lt. Comdr. Karl F. Poehlmann), the Calvert sailed from Hampton Roads on 25 October and joined the main body in mid-Atlantic on 30 October.[15]

A picturesque touch was furnished by the S.S. Contessa. Considerable difficulty had been encountered finding a vessel of sufficiently light draft to negotiate the shallow, 12-mile passage up the Sebou River to Port Lyautey. Unless the planes our forces intended to land at that airport were to be immobilized through lack of gasoline and bombs, some means must be found to deliver these and other aviation supplies promptly. A survey of the available transports failed to disclose one that did not draw more than the channel depth, 17 feet. The Contessa, an old 5,5000-ton British-built fruit vessel, then en route to New York, was accordingly contacted by wireless and directed to Newport News. Although operated by the United States Maritime Commission, she flew the Honduran flag. Her captain, William H. John, was British, the first-mate Italian-American, the second mate Norwegian, the third mate American. The first engineer was British, the second German-American, the third Honduran. In her crew were Filipinos, Swedes, Danes, Estonians, Spaniards, Portuguese, Mexicans, Peruvians, Belgians, Brazilians, Finns, Arabs, and Australians.

On reaching Newport News the crew of the Contessa scattered before the vessel could be impressed into service and many men could not be reached. In order to man the ship, the jails of Norfolk were combed. With this motley crew her captain nevertheless volunteered to sail her unescorted over the submarine-infested Atlantic. A Reserve officer, Lieut. A.V. Leslie, was put on board as a “liaison officer” with authority to assume command should the crew become obstreperous. The crew,

__________

15 This detachment was designated Task Group HOW 15.

14

however, proved exemplary. On 26 October the Contessa sailed indedendently from Hampton Roads.[16]

The largest armada in history was now on its way.

THE ATLANTIC CROSSING

The cruising formation of the Task Force[17] was normally as follows: The Protective Screen (consisting of the former Covering Group reinforced by additional destroyers) took station about 14 miles ahead of the convoy, the Air Group about 12 miles astern. The escort ships (Convoy Screen) formed an outer and an inner screen. The vessels of the outer screen maintained station approximately 10 miles ahead of the main body or at the extreme limits of visibility (about 8 miles) on the quarter or beam of the convoy. The vessels of the inner screen patrolled sectors approximately 6,500 yards ahead, 4,000 yards on the beam or 2,000 yards astern of the convoy. The convoy itself steamed in 9 columns preceded by the Augusta, the Force Flagship. The New York and the Texas headed the two outer columns. The escorting vessels not otherwise assigned were stationed around or among the transports with a line of lighter vessels to the rear to deal with trailing submarines.

In routing the Task Force across the Atlantic extreme care was taken to mystify the enemy as to the actual designation. Detachment ONE took an initial southerly course as if heading for the West Indies. When well clear of the coast this course was changed to east and later to north. Detachment TWO took a northeasterly course as if heading for the British Isles. The two groups effected their junction in the afternoon of 26 October. The Air Group proceeded northeast from Bermuda and joined the main body in the afternoon of 28 October, in approximately longitude 51ᵒ W., latitude 40ᵒ N. Here the course was changed sharply to the southeast, as if the ultimate destination were Dakar. This general

__________

16 The cruise of this vessel sounds like a story by Conrad. After a hectic voyage during which she lost her way, the Contessa turned up at Safi a few hours prior to that landing. She was thereupon headed up to Mehdia, escorted by the Cowie. Up the winding channel, over sand bars, past obstructions, the Contessa scraped her way in spite of dented plates and leaking steams. Two miles south of Port Lyautey she ran hard aground and, before she could be floated, the ebb tide swung her around until she was pointing down stream. She had accomplished her mission, however. Lighters were rushed out from the airport, which had just been occupied, and her invaluable cargo was safely disembarked.

17 Unless otherwise specified, the term Task Force is applied to the Western Naval Task Force and the term Task Force Commander to Rear Admiral Hewitt.

15

southeasterly course, with slight variations necessitated by the fueling of the combat ships, was continued until a point was reached approximately due south of the Azores and west of Canary Islands. There the course was again changed to the northeast, in the general direction of the Straits of Gibraltar. Care was taken, however, to avoid possible unfriendly air searches from the Azores and the Canaries. Passing to the north of Madeira, the destroyers fueled again on 6 November, after which the entire Task Force proceeded to a point northeast of Casablanca, preparatory to separating according to objectives.

Once off soundings, the true destination of the expedition was revealed to the personnel, thereby putting an end to considerable speculation and arousing great enthusiasm. The “useless chatter” over the TBS that resulted brought a pointed admonition from Admiral Hewitt to whom it sounded “more like a Chinese laundry at New Year’s than a fleet going to war.” Other precautionary measures were taken in the interest of security. Nothing was to be thrown overboard during daylight. Bilges were not to be pumped until after twilight. All cans were to be well punctured before disposal.

Stringent regulations were adopted to deal with any craft sighting the Task Force. “Neutral merchant vessels and aircraft which are met at sea shall by their presence be considered as having established prima facie evidence of aiding the enemy,” read the instructions to the screen. All such vessels were to be boarded and set on the quickest course that would take them out of sight. If necessary to insure secrecy, they might be detained in an Allied port. Flagrant violations of the rules against unneutral service might lead to capture and even sinking. Aircraft were to be shot down.

The amount of drilling in small boat technique given the men during the crossing varied with the individual commanders. One ranking Army officer reported that on his transport “very little” training was done en route and on the other “apparently less.” On the other hand, another officer noted that on his transport “all boat crews and soldiers familiarized themselves with the plan, harbor and facilities. Everyone rehearsed in their detailed duties.”

Radio silence was strictly enforced, but at home the broadcasters were busy, so much so that many officers were afraid all their elaborate precautions would be nullified. When finally the magic word “Casablanca: came over the air “the armchair jockeys who pontificate on the radio

16

and in the press to the menace of our lives and the detriment of our efforts” were roundly denounced. “One need not have the perspicacity of the Three Wise Men,” one irate officer reported, “to see that bit by bit injudicious admissions as to the location of likely operations have gone so far as to bring the name of Casablanca into the news. And here we are at sea, still hundreds of miles from our objective and the ocean lousy with U-bots.” No wonder the fleet zigzagged so continuously that its track looked like that “of a reeling drunk in the snow,” to quote one eye-witness. During one of these gyrations the Brooklyn was compelled to reverse engines to avoid colliding with the Hambleton. “I believe in a two-Navy ocean for you and me,” was the good-natured comment the cruiser made to the destroyer.

On 31 October a radio message was picked up. “Going down slowly 35-06 North, 16-59 West. Many wounded and dying. Please send help” – a grim reminder of the serious business in hand.[18] In spite of frequent alarms no authenticated submarine attack was recorded. This is all the more remarkable and indicative of the efficacy of the protective measures adopted, as numerous enemy scouting lines had been formed across the route that was being traversed and the Task Force numbered no less than 99 vessels. One stationary line was reported along latitude 40ᵒ N., from Spain to the Azores. Another extended from the African coast westward to the Cape Verde Islands, thence south to Dakar. A third was said to extend initially from the west of the Azores to west of the Cape Verde Islands and to be retiring northeastward as the convoy approached. It is probable that the convoy was sighted by submarines as early as 25 October; yet no attacks developed.

The passage was an uneventful one. On 1 November, the Augusta radar spotted an unidentified aircraft crossing the convoy track from port to starboard, probably a clipper. On 2 November, the Doran reported that her number three magazine had been flooded, apparently with malicious intent. The saboteur, who was probably mentally deranged, was apprehended. On 3 November, a Ranger plane on antisubmarine patrol crashed. The personnel were rescued but the plane sank. On 4 November, the Miantonomah was forced to drop out because

__________

18 This distress signal undoubtedly was sent by the S.S Alaska (nor. Cgo. 5,681 tons), which was torpedoes about 1900Z, 30 October, at 35-06 N., 16-59 W., and sent distress signals on the 30th and 31st. When torpedoed, she had just picked up 55 survivors from the S.S President Doumer hit at 1865Z. The Alaska ultimately made port.

17

of excessive roll. The Raven was detailed to escort her, the two vessels to rejoin as soon as practicable. This was not until 4 days later. The voyage was drawing to an end, and as a result of the proximity of land, coastwise shipping was beginning to appear. On 5 November, a Portuguese streamer was sighted by the screen in time to be avoided by an emergency turn to port. The next day a Spanish streamer was picked up by the screen but, as she did not sight the convoy, was allowed to proceed. On 6 November fishing craft and coastal steamers were thereafter encountered. All were rounded up.

As the African coast was approached “the progress of the political offensive fluctuated from day to day. One day it seemed that the French were going to resist, then word came that the Army and Air forces would not oppose us, and then that the attitude of the French Navy was in doubt. Everyone hoped that they would save their bullets for the Nazis, but French war psychology is completely inexplicable and we could take no chances.”

On the night of 6-7 November, weather dispatches from Cominch, the War Department and the beacon submarines[19] off the Moroccan coast were received. From these reports the fleet meteorologist was able to state that both wind and swell would decrease and that favorable weather conditions would prevail during the next 48 hours. The Force Commander therefore decided to put the attack plan in operation and signals to that effect were dispatched to all units. D-day Was set for 8 November and H-hour for 0400.[20]

The good fortune that had attended the expedition in its approach maneuvers was well summed up by one officer who reported as follows: “Against no other inhabited civilized coast could an approached have been made to a point within 16 miles of the main base, in darkness, using radar of all types, whistles and light maneuvering signals, fathometers and radio telephone without bringing down instant and strenuous opposition… Without any intention to detract in the slightest from the success that was achieved, I must say seriously and emphatically that I do not believe

__________

19 Task Group HOW II consisted of: Barb(F), Lt. Cmdr. John R. Waterman, off Safi, Blackfish, Lt. Comdr. John F. Davidson, off Dakar, Herring, Lt. Comdr. Raymond W. Johnson, off Casablanca, Shad, Lt. Comdr. Edgar J. Macgregor, III, off Mehdia, Gunnel, Lt. Comdr.. John S. McCain, Jr., off Fedala.

20 All times given hereafter are Zed time.

18

Casablanca Harbor

0-44-566293 Faces p. 18

0-44-566293 Faces p. 19

El Hank lighthouse

Naval battery at Mehdia

that under identical conditions of organization and training this feature of the operations could be repeated once in ten tries."

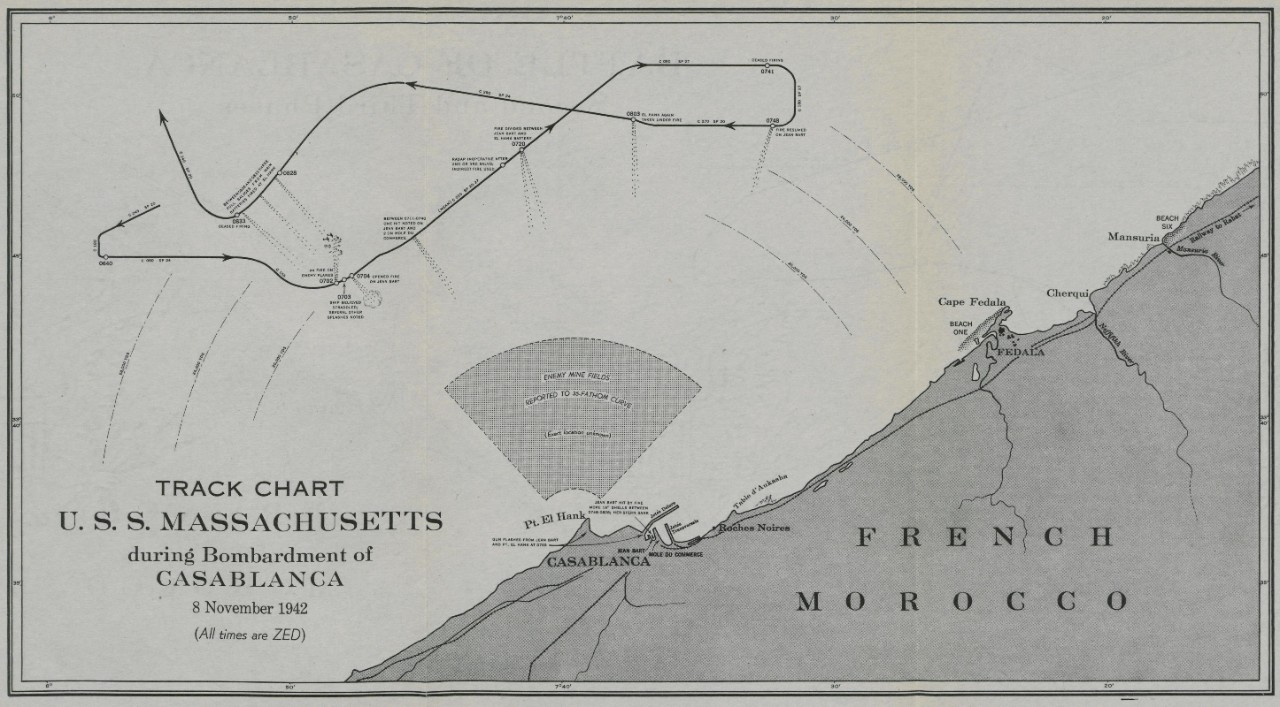

THE BATTLE OF CASABLANCA

Intelligence indicated that the French naval forces and land batteries on the Moroccan coast would probably offer resistance. A battle plan had accordingly been adopted in which targets were assigned to specific vessels of the Covering Group. That group now consisted of the Massachusetts (F), Tuscaloosa, Wichita; the destroyers Wainwright, Mayrant, Rhind, and Jenkins and the oiler Chemung. The Massachusetts had given the task of destroying the Jean Bart and the major caliber shore batteries. The forward turrets were to fire on the French battleship and the after turret on the heavier battery on Point El Hank. The Tuscaloosa had been assigned to submarines, cruisers, and other naval craft in Casablanca Harbor, in that priority. The Wichita was to open fire on the lighter battery on the tip of Point El Hank, then shift to submarines, cruisers, and other craft, thence to Table d’Aukasha.[21] The destroyers were to provide antisubmarine screen for the heavy ships, destroy enemy submarines should they sortie, provide defense against air torpedo and bombing attacks, and destroy enemy light vessels and shore installations as might be directed.

In the event that the Task Force Commander should receive an indication of the surrender of the port of Casablanca, or of the desire of the armed forces therein for the peaceful entry of the American armed forces, the commander of the destroyers (Capt. Moon in the Wainwright) would, upon signal, proceed with utmost regard for the mine fields, enter the harbor, and take the necessary steps to immobilize French naval vessels and shore batteries. This special mission was never called into operation in view of the hostile attitude of the French forces.

Admiral Giffen was in command of the Covering Group, subject, however, to Admiral Hewitt who was in command of the entire Task Force. The various organizations and subdivisions of the Task Force have been criticized as unnecessarily complicated. Without going into that mooted question, it should be pointed out that the detailing of an appropriate force to deal with the French naval units, leaving the fire support units

__________

21 The Jean Bart was moored to the southeastern end of the Môle du Commerce, the other vessels were berthed alog the Jetée Delure.

of the attack groups to give direct protection to the landings, was tactically sound and certainly proved effective. The French fleet was the main objective of the Covering Group, although in effecting its destruction that group inevitably came into contact with the shore defenses. The operations of the Covering Group, but they constituted a separate action designated to give indirect protection to the landing operations of all three attack groups by forestalling interference by the French naval units based on Casablanca.

The Battle of Casablanca falls into three phases. The first began with the opening moves for position and continued until the sortie by the French fleet which was completed at about 0830. The second phase is concerned mainly with the destruction of the French fleet, which was practically complete by 1300. The third and last phase is concerned with the engagement with the El Hank batteries and covers the period between 1300 until the retirement of the Covering Group at about 1600.

FIRST PHASE

7 November

| 0653 | Southern Attack Group released. |

| 1515 | Northern Attack Group released. |

| 1535 | Center Attack Group released. |

| 2215 | Covering Group changes and beings maneuver on parallelogram. |

| 2400 | Casablanca receives first alert. |

8 November

| 0300 | Casablanca receives second alert. |

| 0610-0624 | Nine planes launched. |

| 0641-0642 | Planes from Massachusetts encounter antiaircraft fire and hostile aircraft. |

| 0702 | Massachusetts open fire on enemy planes |

| 0703 | Gun flashes observed from El Hank and Jean Bart. |

| 0704 | Massachusetts opens fire on Jean Bart on first run. Tuscaloosa and Witchita follow. |

| 0720 | Massachusetts divides fire between El Hank and Jean Bart. |

| 0741 | Reserve run started. |

| 0751 | Wichita opens fire on Table d’Aukasha |

| 0818 | Cruisers concentrate on harbor mouth |

| 0833 | Covering Group ceases firing. |

The morning of 7 November found the Task Force proceeding in a general southeasterly direction. At 0655 the Southern Attack Group was

20

released and proceeded to its destination, Safi. Immediately thereafter the remaining groups changed course to 076.5ᵒ T., as if heading for the Straits of Gibraltar. At 1515 the North Attack Group was released and proceeded to its designation, Mehdia. At 1535 the Center Attack Group was released and, after some variations, ultimately settled down to a basic course of 145ᵒ T. In the meantime, the Covering Group, after a short run to the south, took an approximately parallel course of 144ᵒ T., which placed it about 10 miles to the southwest of the Center Attack Group is a position to cover it from any interference by the French fleet based on Casablanca. The plan called for the arrival of the three attack groups before their objectives about midnight when debarkation was to begin.

At 2215 the Covering Group changed course to 246ᵒ T. and proceeded to cover an irregular parallelogram designed to keep it between the Center Attack Group and Casablanca while debarkation was being effected and to bring it to a position to open fire on Casablanca at sunrise (0656) should it become necessary. After completing these four courses the Covering Group, at 0542 on the 8th took a course 245ᵒ T. and began the launching of planes. Between 0610 and 0624 nine planes had been launched as follows:

ANTISUBMARINE PATROL

| Tuscaloosa | 2 SOC-3 |

| Wichita | 1 SOC-3 |

SPOTTING

| Massachusetts | 2 OS2U |

| Tuscaloosa | 2 SOC-3 |

| Wichita | 2 SOC-3 |

The normal formation of the Covering Group was as follows: The heavy ships proceeded in column, distance 1,000 yards, the Massachusetts (F) in the van, followed by the Tuscaloosa and the Witchita in that order. The heavy ships were screened by the four destroyer in a semicircular formation about 3,000 yards ahead of the flagship, the Wainwright and Mayrant to starboard, the Rhind and Jenkins to port.

In the meantime the French naval authorities at Casablanca had received a first alert shortly midnight, followed by a more serious one at about 0300 of the 8th. Nevertheless, no reconnaissance patrols were undertaken. Whatever routine patrols were maintained were so

21

ineffective that our arrival off Casablanca was a distinct surprise. When, shortly before midnight on 7 November, our forces came within range of Point El Hank, the light was found burning. It was not extinguished until shortly after midnight.

It soon became apparent that the intelligence predictions to the effect that the French fleet and land batteries would offer considerable resistance were about to be realized. Intercepted messages from the Southern Attack Group thereupon began to maneuver itself into a position for the first run past Casablanca. At 0640, the course being 090ᵒ T, the group began closing the range.

At 0641 one of the spotting planes from the Massachusetts reported that it was under antiaircraft fire from the beach. One minute later the other plane reported that it had encountered hostile aircraft, followed at 0655 by a similar report from the first plane. At 0700 six fighter planes were observed ahead of the flagship at a very low altitude (about 1,200 feet) pursuing several of our SOC-3’s and one of our OS2U’s. The order was therefore given to the flagship to engage the enemy aircraft.

At 0703 gun flashes were observed from the direction of El Hank and the Jean Bart, followed by several large splashes near the Massachusetts. Indeed, it is believed that the El Hank battery straddled the flagship on the first salvo. Five or six very large splashes, presumably from shells fired by the Jean Bart, were observed about 600 yards short, on the starboard bow of the flagship. The engagement, which up till then had been limited to aircraft, now became general. The cruisers had been previously directed to open fire when the flagship did so without further signal.

On the morning of 8 November the wind was from the southwest, force one to two; sea moderate with slight swell. In general, weather conditions were excellent except for surface haze, particularly near shore. As the morning wore on, however, sun glare and reflection added to the difficulty of spotting and observation. Little could be done to improve conditions insofar as sun glare was concerned except by staying to the

22

northeast of the harbor, from which point the batteries of El Hank could not be bombarded.

At 0704 the main batteries of the flagship opened fire on the Jean Bart, range 24,400 yards, bearing 131.5ᵒ T. Thereafter, during the first run, the range to the Jean Bart varied from 23,200 yards at 0711, to 29,600 yards at 0740. During this period one hit on the Jean Bart, and two on the Môle du Commerce were noted. No radar ranges or bearings were obtained since the fire control radars on the flagship became inoperative after the second or third salvo. Air spot was also uncertain during this period because of the smoke, antiaircraft fire, and enemy fighters. Indirect fire based on a bearing obtained on the El Hank Lighthouse was used. After about 15 minutes, however, the main battery of the Jean Bart ceased firing and did not fire again during the day.[22]

At 0720 the flagship divided her fire. Turret No. 3 shifted to the El Hank battery while the forward turrets continued firing at the Jean Bart. The range of Point El Hank at this time was 22,900 yards, bearing 173ᵒ T.

During this opening period of the action the course of the Covering Group was 050ᵒ T. and thereafter, until 0730, speed varied from 20 to 27 knots. Various courses were steered, the mean course being 055ᵒ T. From 0730 until the end of the first run at 0741 the course was 090ᵒ T. Small changes in course and speed were made at frequent intervals in order to make it as difficult as possible for the enemy fire control. In general, course changes were made towards the last splashes (i.e., “chasing the splashes”). Later, this became impracticable in views of the fact that the heavier ships, particularly the flagship, were often straddled.

At 0705 the Tuscaloosa opened fire on the submarine berthing area in Casablanca Harbor, and at 0719 she shifted fire to the shore batteries at Table d’Aukasha, the opening range being 27,000 yards, minimum range 24,800 yards. Plane spot was used. After 20 minutes the batteries were silenced.

The Wichita opened fire at 0766 on El Hank, range 21,800 yards (using reduced charges) and at 0727 shifted fire (with full charges) to the submarine area in the harbor, range 27,000 yards.

At this stage of the operations enemy planes appeared in considerable numbers. At one time what were believed to be several French torpedo

__________

22 Turret No. 1, the only one containing guns, had become jammed.

23

planes were observed. These, however, did not come within antiaircraft range and made no attacks.

At 0741 the course was changed to south, preparatory to a reverse run to the westward, and at 0748 the course was steadied at 270ᵒ T. The forward turrets of the Massachusetts resumed fire on the Jean Bart. The initial range was 26,000 yards. It varied thereafter from 25,000 yards at 0756 to 31,600 yards at 0828.

At 0803, the course being, then 280ᵒ T., the flagship resumed firing at Point El Hank with turret number three, initial range 24,000 yards, the range thereafter increasing to 28,900 yards at 0818 and decreasing to 27,400 yards at 0831. Between 0828 and 0833 three salvos frim all three turrets were fired at Point El Hank at a mean range of about 27,000 yards.

The Tuscaloosa commenced firing on a second run at 0759 on targets in the harbor (initial range 22,500 yards), shifting at 0810 to Point El Hank (range 28,000 yards). Firing ceased at 0823 as the harbor targets were then out of range.

The Wichita opened fire at Table d’Aukasha at 0751, checked firing in a few minutes when a plane reported that the batteries there were not firing, and at 0806 resumed fire on the ships in the harbor, mean range 24,500 yards.

Both cruisers had been ordered at 0818 to concentrate on the harbor entrance after the planes had reported that the enemy submarines were preparing to sortie.

No hits were made on ships of the Covering Group during the first phase, although there were many splashes close aboard.

At 0830 a message was intercepted to the effect that the Army was encountering no resistance and that the Navy fire was damaging the city. Cease fire was therefore ordered at 0833 pending clarification of the situation. The Covering Group started to withdraw on course 340ᵒ T., although the secondary battery of the Jean Bart was firing what appeared to be two destroyers were observed standing out of Casablanca Harbor. The French were making a sortie frim Casablanca, thereby initiating the second phase of the battle.

24

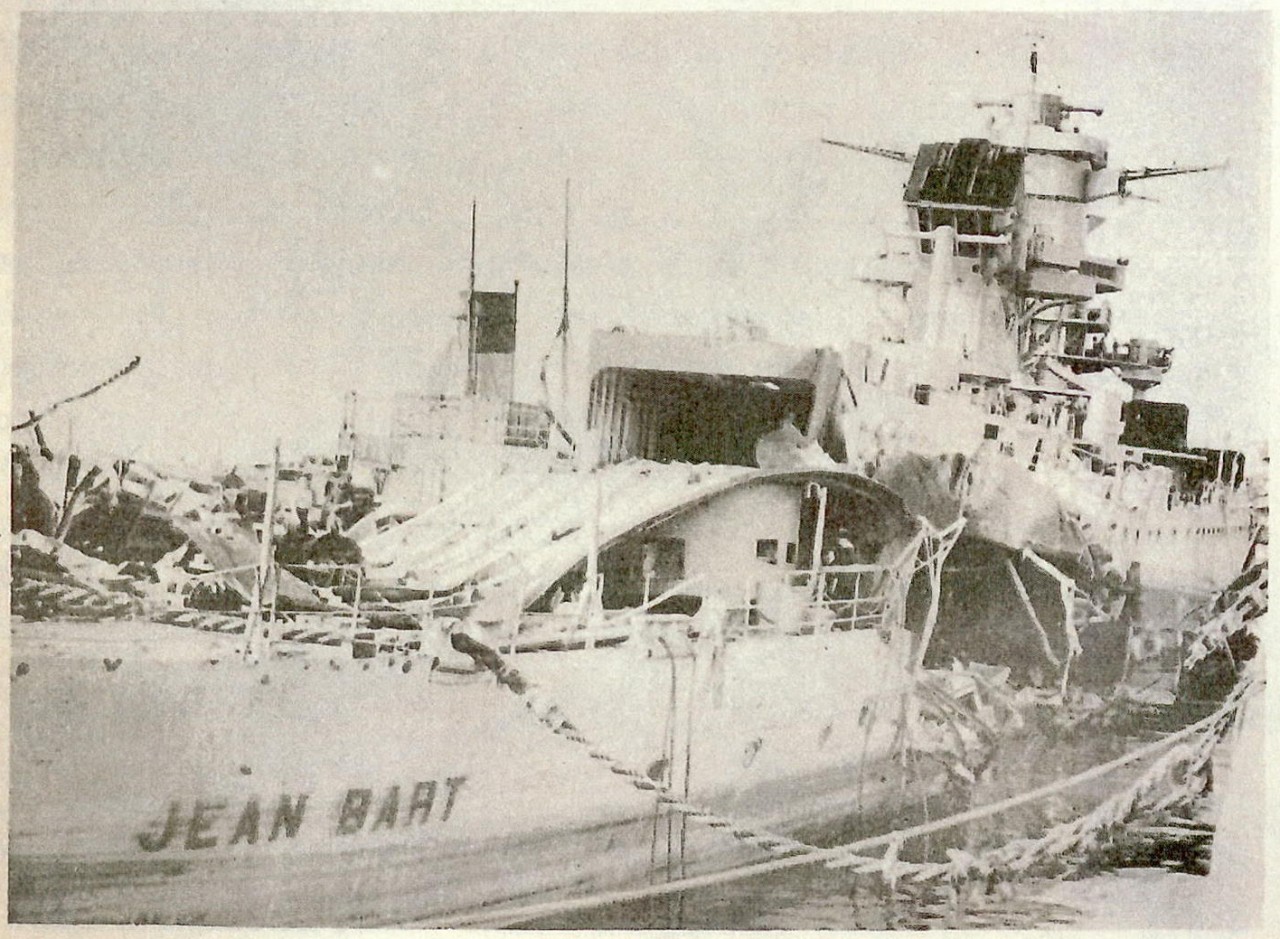

Damage to Jean Bart, bow

Damage to Jean Bart, stern

0-44-566293 Faces p. 24

0-44-566293 Faces p. 25

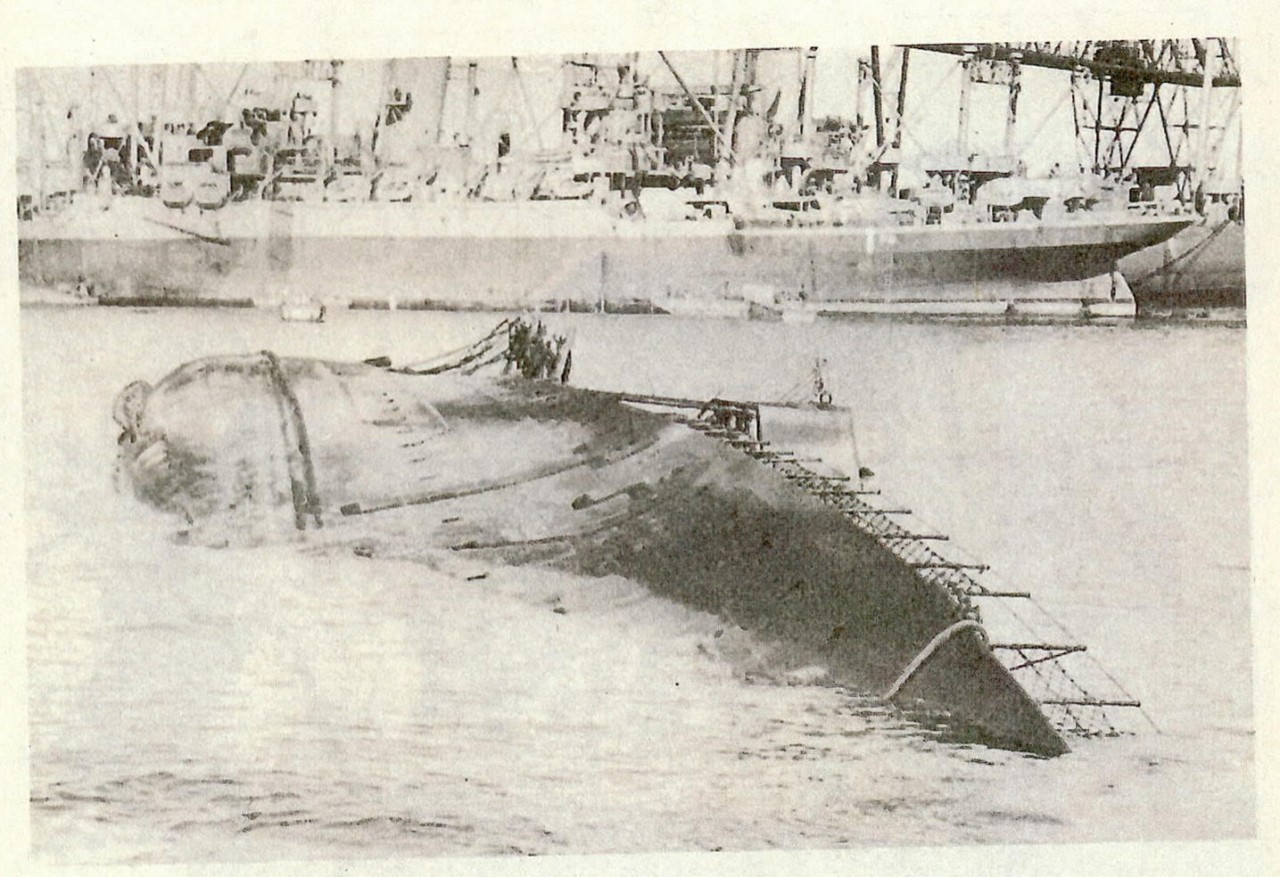

Wreck of the Frondeur

The Primauguet, Albatros, and Milan beached outside Casablanca

The outstanding event of the first phase had been the wrecking of the Jean Bart, which had been hit by 16-inch shells from the Massachusetts,[23] besides being struck by two small bombs. As a result her stern settled until she rested on the bottom.

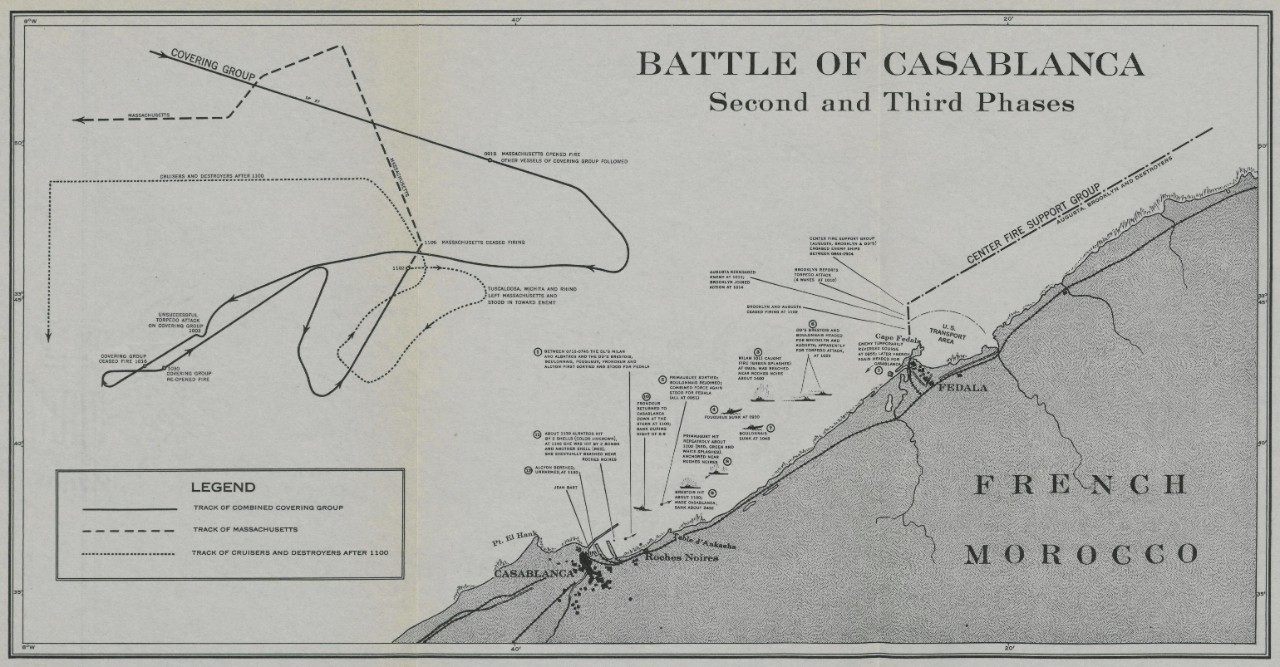

SECOND PHASE

| 0610-0730 | French submarines sortie. |

| 0715-0745 | French destroyers sortie. |

| 0818 | Augusta plane reports movement. |

| 0820 | Milan opens fire. |

| 0843 | Augusta opens fire, followed by Brooklyn. |

| 0918 | Massachusetts opens fire, followed by Wichita and Tuscaloosa. |

| 0925 | Massachusetts disables Milan and Fougueux. |

| 1000 | Primauguet sorties. Fougueux sinks. |

| 1003-1021 | French submarines attack. |

| 1045 | Boulonnais sinks. |

| 1100 | Massachusetts withdraws to save ammunition. Brestois, Frondeur and Primauguet hit. |

| 1106-1142 | Tuscaloosa, Wichita and Rhind engage enemy vessels attempting to regain Casablanca. Wichita hit by shell. |

| 1145 | Cruisers of Covering Group sweep coast to southward. Albatros damaged. |

| 1300 | Cruisers rejoin Massachusetts and withdraw to northwest. |

The second phase of the action was the destruction of the French naval units which sortied from Casablanca.

The French warships in Casablanca Harbor proved to be the battleship Jean Bart, the light cruiser Primauguet, the flotilla leaders (contretorpilleurs) Milan (F), Albatros, Le Malin, the destroyers Alcyon, Boulonnais, Brestois, Fougueux, Frondeur, Simoun, Tempête, the submarines Amazone, Amphitrite, Antiope, Conquérant, Méduse, Oréade, Orphée, Psyché, sidi-Ferruch, Sybille, Tonnant, and the sloops Commandant Delage Gracieuse, Grandiére.[24] They were under the command of Rear Admiral Gervais de Lafond.

As has been noted, the French fleet in the harbor had for some time been subject to a devastating bombardment. The Jean Bart had been wrecked by the fire of the Massachusetts. The submarines Amphitrite, Psyché and Oréade had also been sunk at their moorings by the

__________

23 Two of these shells are known to have exploded. Two orders struck at such angles that the base of each was deformed and the fuze and explosive content forced out before detonation. However, one of these “duds” was the shells which jammed turret No. 1 in train and thus prevented the ship from firing for several crucial hours.

24 Cf. intelligence report above.

25

bombardment. The flotilla leader Le Malin, while moored to the Jetée Delure, was hit by a shell from the Massachusetts which struck the jetty, tunneled through, and entered the port side of the vessel without exploding, causing a bulge outward on the starboard side. The Le Malin did not sortie, nor did the destroyers Simoun and Tempéte, then undergoing repairs.

Between 0610 and 0730 the submarines Amazone, Antiope, Conquérant, Méduse, Orphée, Sidi Ferruch, Sybille and Tonnant had sortied. The subsequent operations of these vessels cannot be definitely stated. Their ultimate fate is all that us known beyond doubt. The Méduse was beached near Mazagan. The Tonnant reached Cadiz and was scuttled by her crew on 15 November. The Amazone and the Antiope managaged to make Dakar. The Conquérant, Sidi Ferruch and Sybille were never reported. The Orphée was the only submarine to return to Casablanca.

Between 0715 and 0745 the French destroyers put to sea and headed northeast in the following order: Destroyer Division II (Milan, Albatros), Destroyer Division 5 (Brestois, Boulonnais), Destroyer Division 2 (Fougueux, Frondeur, Alcyon). Each division was in column and the columns in echelon. The Primauguet did not sortie at this time.

At 0818 a plane from the Augusta reported the movement to the Task Force Commander, who relayed the information to the Covering Group at 0822 and to the Air Group 0840. At 0859 the Covering Group was ordered to head for Fedala, speed 27 knots, and at 0915 received orders to destroy the French vessels.

In the meantime the cruisers of the Center Fire Support (Augusta, Brooklyn) together with four destroyers (Wilkes, Swanson, Ludlow, Rowan) were streaming at 27 knots to intercept the oncoming French vessels.[25] At 0820 the Milan opened fire on the Wilkes. Her shots were short. At 0835 Destroyer Division TWO opened fire. The Augusta replied at 0843, followed at 0848 by the Brooklyn. Firing continued until 0904 at ranges from 13,000 to 24,000 yards. At 0855 the French destroyers temporarily reversed their course but soon returned to the attack, whereupon the Brooklyn resumed fire at 0909 and the Augusta

__________

25 No track chart of the French ship movements is available. The track chart of the Center Fire Support is too involved to reproduce. The evolutions of those vessels covered a small area and were designated to keep them within range of the French as long as possible without prejudice to the protection of the transport area.

26

0915. The French vessels broke the engagement about 0920 and headed back to Casablanca.

On the way they were engaged by the Covering Group. At 0918 the Massachusetts opened fire, followed by the Wichita at 0919 and the Tuscaloosa at 0925. The French returned the fire at once. Their fire control was excellent. The Massachusetts was hit twice, with slight damage. Another shell passed through the flagship’s colors. These hits. However, may have come from El Hank battery.

It was during this period that the French sustained their first losses. At 0925 the Massachusetts reported that the flotilla leader with which she had been engaged was seen with only her bow out of water. This undoubtedly was the Milan, which had been hit by three shells below the water line and two or three near the bridge and had caught fire twice. She was ultimately (1400) beached near Roches Noires. The flagship then shifted to another target which appeared to be a destroyer. After three salvos the target completely disappeared. She was probably the Fougueux, which sank about 0930 in latitude 33ᵒ 42’ N., longitude 07ᵒ 37’ W. At 1016 the Covering Group ceased firing.

At this point the Center Fire Support reengaged the retreating enemy, the Brooklyn opening fire at 1015 and the Augusta at 1025. At 1030 the Covering Group resumed firing. A “melee engagement” with the French destroyers ensued during which, at 1045, the Brooklyn received her only hit by a shell which, although it did not explode, injured six men.

At this stage of the action the Primauguet sortied from Casablanca, rallied the Boulonnais, which had damaged her steering gear and had fallen behind, and proceeded once more up the coast toward Fedala with the other destroyers. The French vessels soon found themselves under the combined fire of the Covering Group and the Center Fire Support. Hits began to accumulate. At 1045 the Boulonnais sank in latitude 33ᵒ 40’ N., longitude 07ᵒ 34’ W., mainly as the result of fire from the Augusta. The remaining destroyers (Frondeur, Alcyon) formed on the Brestois. At about 1100 this vessel took a bad list and with difficulty managed to return to port where she capsized off the Jetée Delure at 2400. The same fate befell the Frondeur which returned to port about the same time down by the stern. She sank at her berth during the night. It is impossible to assign the hits on these three vessels. Their destruction was

27

probably the work of several ships. The color splashes reported by the French would so indicate.[26]

At 1102 the Center Fire Support ceased firing except for occasional long range shots by the Brooklyn.

By 1100 the Massachusetts had expanded 60 percent of her 16-inch ammunition and the preservation of the remainder was considered essential against a possible sortie by the Richelieu from Dakar. The cruisers of the Covering Group had expended an even higher percentage, but it was felt that their attendant upon further depletion of the flagship’s main battery ammunition. Accordingly, at 1102, the commanding officer of the Tuscaloosa was ordered to take the Wichita and the Rhind under his command and close with the enemy light forces. At 1106 the flagship ceased firing and hauled away to the northward while the cruisers and the Rhind stood in and engaged the enemy vessels which were attempting to regain the harbor. Firing continued until 1142. It was while engaging the enemy at close quarters that the Wichita was hit by a French shell (1128) which injured 14 men.

By this time the only French vessels afloat were the Primauguet, Albatros and Alcyon. Shortly after 1100 the Primauguet was badly hit, five shells striking below the water line and an 8-inch shell in No. 3 turret. She came in and anchored off Roches Noires. (Between 1400 and 1700 she was bombed and strafed and her whole forward half wrecked. A direct hit on the bridge killed the captain, the executive officer and 7 other officers.) About one-half hour later (1130) the Albatros was hit by 2 shells, 1 of which was below the water line forward.[27] At 1145 she received 2 bomb hits amidships. Completely helpless, she asked for a tow. While being towed back to Casablanca she was shelled and strafed. She was eventually beached at Roches Noires. Of a crew of 200, 25 were reported killed and 80 wounded. The inly surface vessel to return safely to Casablanca was the destroyer Alcyon which made port about 1130.

At about noon the three sloops Commandant Delage, Grazieuse and Grandiére, which had remained in the harbor during the engagement,

__________

26 The color splash of the AP ammunition used by the Massachusetts and the Brooklyn was green, that of the Augusta red. The destroyers did not use color splashes. The bombardment ammunition of our cruisers was also free from color.

27 The French timetable, from which these times are taken, only gives approximate times.

28

sortied to pick up the survivors of the Boulonnais, Fougueux, and Milan. While so doing they became engaged with the Augusta and the Brooklyn at 1326. The Graniére was slightly damaged by bombs at 1330.

At about 1145 a message was intercepted from the Task Force Commander stating that an enemy cruiser was laying a smoke screen southwest of Casablanca and heading down the coast. The cruisers of the Covering Group, screened by the Rhind, were order to sink her. No trace of this cruiser was found so at 1300 our cruiser headed back to rejoin the flagship.

With the withdrawal of the Covering Group the second phase of the battle ended. It had witnessed the practical annihilation of the French fleet.

NOTE: The sortie of the French fleet had been the occasion for some submarine activity. At 1003, just after the course had been change from 250ᵒ T. to 230ᵒ T. (see tracked chart of Massachusetts), the wakes of four torpedoes were sighted by the executive officer of the Massachusetts about 60ᵒ on the port bow at a distance of less than 1,000 yards. By skillful maneuvering the flagship passed between numbers three and four in the spread, counting from the left. Number four torpedo passed a few feet outboard of the starboard paravane. All ran very shallow. It is believed that they were fired by a submarine at a range of between 4,000 and 5,000 yards. Emergency signals were made by flag hoist to the ships astern. After avoiding the torpedoes, the ship changed course to 240ᵒ T. At 1018 the course was changed to 090ᵒ T. in order to overtake what appeared to be a submarine on the surface and a ship on the port quarter. At 1021 another torpedo wake was sighted and passed about 100 yards to port. In the meantime, at 1010, an unsuccessful submarine attack was made on the Brooklyn. The wakes of four torpedoes were observed, as well as the bubbles from the tubes.

THIRD PHASE

| 1326 | Covering Group begins search for enemy vessels reported proceeding to Fedala. |

| 1341 | Massachusetts located one destroyer. El Hank open fire. |

| 1355 | Cruiser of Covering Group continued search, advancing to mouth of Casablanca Harbor. |

| 1450 | Land batteries at Casablanca compel retirement. |

| 1558 | Massachusetts fire salvo at El Hank, then retires with Covering Group. |

29

The third phase of the engagement began with a search for French units which were reported steaming along the coast with the probable intention of interfering with our landing operations. The action soon developed, however, into an attempt to silence the persistent batteries at Point El Hank which had maintained an intermittent fire during the entire battle. These batteries, as well as the other fixed defenses, were manned by naval personnel, which probably accounts for their determined resistance.

At 1302 a message was received from the Task Force Commander that two cruisers and a destroyer had been reported standing up the coast from Casablanca to Fedala. At this time the Covering Group cruisers and the Rhind had not yet rejoined from their sweep to the southwest in pursuit of another French cruiser which had been reported as having slipped through. At 1326 the Covering Group set course 080ᵒ T. toward Fedala and increased speed to 27 knots, At 1340 the Massachusetts opened fire in a light vessel, bearing 136ᵒ T., range 22,000 yards. If the French timetable is correct, the only vessel that could possibly have been in the neighborhood of Fedala was one of the three sloops. Only two salvos, however, were fired at this target, as the El Hank batteries opened at 1341 with excellent aim. All turrets were shifted accordingly to that target at 1345. The range was 19,000 yards, increasing gradually to 23,000 yards when firing ceased at 1350.

About this time the Task Force Commander ordered the Covering Group to destroy before nightfall the light forces which appeared to be making sorties frim Casablanca. At 1355, accordingly, the cruisers, plus the Rhind, stood in toward the harbor, this time from the direction of Fedala in ordered to avoid gunfire from El Hank. An enemy vessel, undoubtedly the Brestois, was shelled near entrance at range of 17,000 yards. No gunfire was observed from the French ships but the shore batteries again forced retirement at about 1450. At that time two other enemy vessels were observed outside the harbor, near the entrance. One of them (obviously the Milan) was on fire, another (probably the Albtros) was beached.

At 1423 the Massachusetts received orders from the Task Force Commander to preserve ammunition for a possible sortie of the Richelieu from Dakar and, as a result, broke off the action. There were, however, several loaded 16-inch guns on the flagship and it was decided to unload them on Point El Hank. This was done at 1558 at a range of about

30

30,000 yards. After one ranging shot a six-gun salvo was fired. Although over, the Salvo apparently hit explosive or inflammable stores. As an unusually large explosion was noted.[28]

Shortly thereafter the flagship was joined by the cruisers and the group stood out to sea, thereby terminating the third phase of the battle.

Summary

The performance of the Covering Group in clearing the way for the troop landing had been an outstanding one despite the failure of the radar to function properly on the larger units of the fleet. The concussion of the large caliber guns soon put the greater number of the radar range finders out of commission. As a result the expenditure of ammunition was much greater than had been anticipated.

The following table is illuminating.

| Ship | Battery | Percent Expended |

| Massachusetts | 16 inch 5 inch |

67 2.25 |

| Tuscaloosa | 8 inch 5 inch |

85 1 |

| Wichita | 8 inch 5 inch |

83 7 |

| Wainwright | 8 inch 5 inch |

25 |

| Rhind | 5 inch | 8 |

| Mayrant | 5 inch | 30 |

| Jenkins | 5 inch | 6 |

It will be noted that the Massachusetts, Tuscaloosa, and Wichita had expended so great a portion of their heavy caliber ammunition that they would have been seriously embarrassed if compelled immediately to go into action against the larger units of the French Navy.

A similar state of affairs existed on some of the other vessels of the fleet. The Brooklyn, which had been operating off Fedala, reported a total ammunition expenditure of 75 percent.

The performance of the French naval forces, both ships and batteries, throughout the entire engagement was excellent. Their gunnery was accurate, straddles being frequently made on the first salvo. That more hits were not scored on our vessels was due to the skill with which they

__________

28 As only AP 16- inch shells had been issued to the Massachusetts, the damage inflicted on shore batteries was less than that obtainable had HC shells been employed. The Massachusetts, however, had to be prepared to fight the Richelieu as well as the Jean Bart.

31

maneuvered and to the high angle of fall of the French projectiles at long range.