The Navy Department Library

THE PIONEERS - A MONOGRAPH ON THE FIRST TWO BLACK CHAPLAINS IN THE CHAPLAIN CORPS OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY

H.L. Bergsma

Commander, Chaplain Corps

United States Navy

Download PDF Version [9.1MB]

THE PIONEERS

A MONOGRAPH ON THE FIRST TWO BLACK CHAPLAINS IN THE CHAPLAIN CORPS OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY

H.L. Bergsma

Commander, Chaplain Corps

United States Navy

NavPers 15503

S/N 0500-LP 277-8140

For sale by the Superintendents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Unless otherwise noted, all materials in this monograph are taken from Chaplains Corps files and from personal interviews Commander Herbert L. Bergsma, Chaplain Corps, U.S. Navy, former Chaplain Corps Historian, conducted with the chaplains involved. All quotations are taken from those interviews.

Due to trandfer of Chaplain Bergsma, editing was done by his Commander H. Lawrence Martin.

Appreciation es expressed to the following, who read the manuscript and offered valuable suggestions: Rear Admiral Neil M. Stevenson, Chaplain Corps, U.S. Navy, Deputy Chief of Chaplains; Dr. Dean C. Allard, Head, Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center, and Mr. Edward Marolda, Historian, Naval Historical Center.

ii

FOREWARD

The Chaplain Corps of the U.S. Navy has never been a static organization, but a constantly changing and growing one. In regard to the presence of Black chaplains in the Corps, change has come about partly as a result of sociological struggle, and partly because of increased understanding and cooperation on the part of individual chaplains.

Growth has occured, as in a spirit of brotherly love and professional statesmanship Black chaplains have been well received into partnership in military. Whereas the first Black chaplains, James Russell Brown and Thomas David Parham, Jr., reported to active duty in 1944, at this time there are forty-seven Black chaplains on active duty, and the number is rapidly increasing.

It seems quite appropriate that the first Black officer to attain the rank of captain in the U.S. Navy, T.D. Parham, Jr., should be a member of the Chaplain Corps.

ROSS H. TROWER

Rear Admiral, Chaplain Corps

U.S. Navy

Chief of Chaplains

December, 1980

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Acknowledgement | ii |

| Foreward | iii |

Rear Admiral Ross H. Trower Chaplain Corps, U.S. Navy Chief of Chaplains |

|

| Introduction | 1 |

| James Russell Brown | 3 |

| Thomas David Parham, Jr. | 11 |

v

INTRODUCTION

Pioneers have always been honored in the United States. They have pitted themselves against the unknown, the untracked, and the untried, and they have typically won. Such idealism, however, fares better in novels and on television than in reality. The experience of the pioneer is difficult, bewildering, and often painful. On the other hand, it is uplifiting as one envisions the glory that lies beyond. Perhaps the pioneer’s endurance of loneliness, separation, and isolation is as germane to the triumph as he physical crossing of a frontier.

1

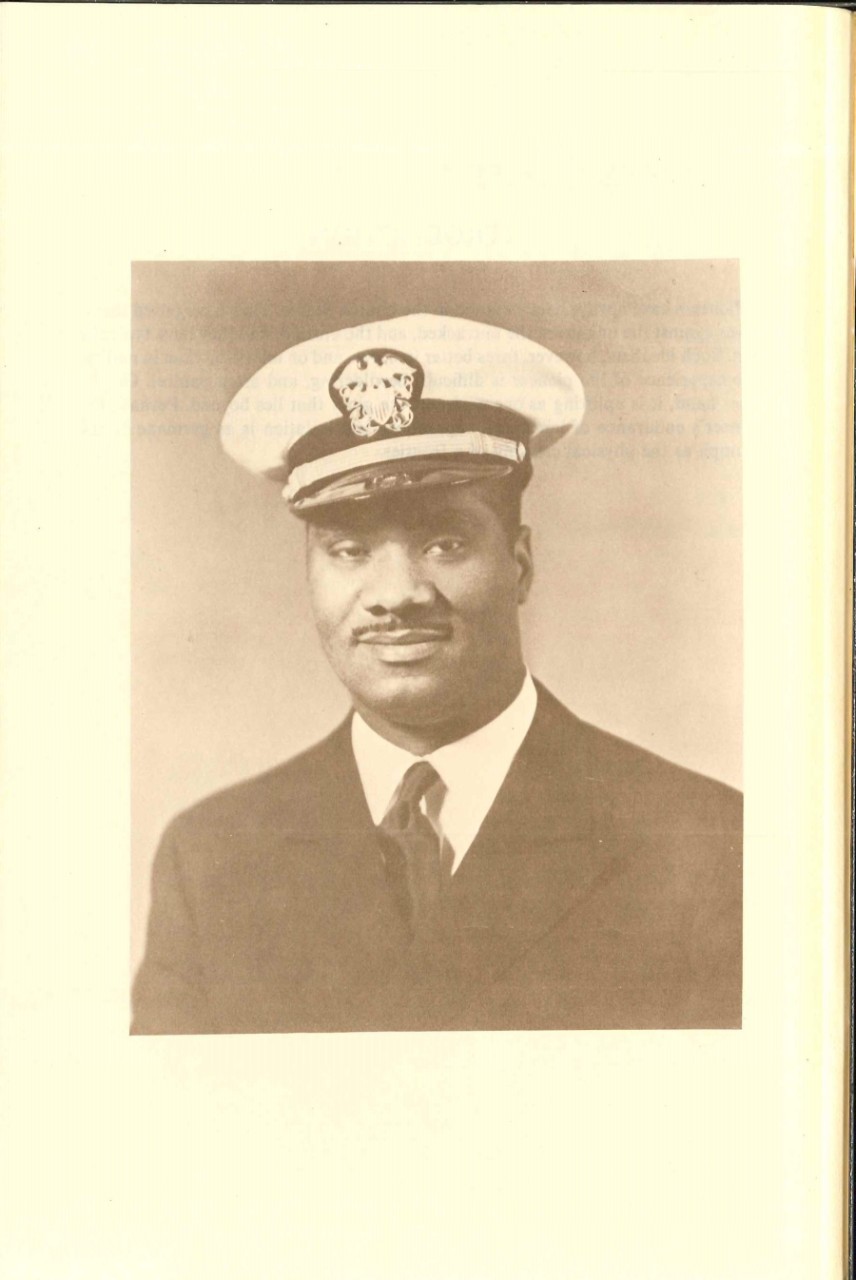

JAMES RUSSELL BROWN

Birth

28 October 1909; Guthrie, Oklahoma

Education

Friends University, Wichita, Kansas, B.A., 1932

Howard University School of Religion, Washington, D.C.; M. Div., 1935

Chicago Theological Seminary, Chicago, Illinois; advanced studies

Iliff School of Theology, Denver, Colorado; advanced studies

Family

Mariage: 26 July 1941 to Melba Ruth Long

Children: Jay, Nanita, Mark, and Melody

Ordination

May 1935 by the African Methodist Episcopal Church

Active Commissioned Service

26 April – 30 April 1946

Permanent Duty Assignments

Naval Training School, Williamsburg, Virginia

Naval Training Center, Great Lakes, Illinois

Supply Depot, Guam

Civilian Occupations

Dean: Bishop Williams School of Religion, Kansas City, Kansas

Pastor: Luke African Methodist Episcoal Church, Kansas City, Kansas

Shorter African Methodist Episcopal Church, Denver, Colorado

First African Methodist Episcopal Church, Kansas City, Kansas

First African Methodist Episcopal Church, Oakland, California

St. Paul Church, Berkeley, California

Charter President of OICs of America

Instructor, City College, San Francisco, California

Member, Human Relations Commissiion, Colorado and Kansas

Retirement

1976, following a forty-three year ministry.

3

Motivation and Encouragement. The entire life of James Russell Brown has been lived in the atmosphere of the church. The African Methodist Episcopal Church community in which he was reared emphasized conversion, dedication, and scholarship. His mother and grandmother were active in church. His paternal grandfather and great uncle were pastors. The stable environment during his early was to direct him unerringly in his own ministry.

There was little inclination toward the Navy on the part of Black pastors in the early years of World War II. The Black minister in the forties was oriented almost exclusively toward the Black community, as much from racial exclusivism as by choice. In 1943-44, however, forces were set in motion which would initiate a greater consciousness of racial equality.

Movement in this direction was begun, not so much by a stirring of righteousness in the hearts of White America, as by the emergency need for the manpower in the war effort. As Chaplain Brown recalled, “They were taking Blacks in [the Navy] like it was Saturday night!” Even so, the Blacks were placed mostly in the steward rating or as stevedores on naval docks. Although upward mobility was slow, a beginning was made, and a few Black visionaries saw hope.

One such visionary was the Reverend Brown’s religious superior, Bishop N.W. Williams, who urged him to become a chaplain in the United States Navy. Bishop Williams, who had been a captain in the U.S. Army during World War I, was so anxious to have Brown enter the Navy as the first Black chaplain that he assured him that his wife Melba could probably become a WAVE1 and travel along! Brown was also encouraged by Bishop R.R. Wright of his church’s endorsing agency. Finally, Bishop John Andrew Gregg, who had a permanent residence in Kansas City where Brown was at this time Dean of the Bishop Williams School of Reverend Brown’s acceptance by the Navy. Bishop Gregg’s opinion was of great value. He had been commissioned by the government to travel worldwide to all except the Russian Front for the purpose of encouraging and inspiring the men in the Black units if the military. The bishop eventually wrote the book Of Men and Arms. He undoubtedly knew that the time of one inspirational circuit-riding preacher was over, and that Blacks needed a Black presence in the Chaplain Corps.

With such encouragement, the Reverend Brown wrote to Chief of Chaplains Robert D. Workman. Ultimately he was directed to the Office of Naval Officer Procurement in Kansas City, where he easily passed his physical examination. Even

________

1 WAVES Women’s Auxiliary Volunteer Emergency Service, which included women serving in both the enlisted and the officer components of the Navy.

4

so, there was some question about there being any openings for a Negro officer (a rarity at the time) until the Reverend Brown produced his letter from the Chief of Chaplains. The embarrassed executive officer re-read his own directives and concluded that an apology was in order.

Brown was commissioned a lieutenant (junior grade), Chaplain Corps, U.S. Navy, on 22 June 1944 to date from 26 April 1944. He reported for active duty on 4 July 1944-an auspicious date in terms of independence and liberty.

Orientation and Isolation. Immediately after reporting for active duty, Chaplain Brown was sent to Williamsburg, Virginia, for Chaplains School. He soon thereafter experienced extreme isolation and loneliness, often being sustained only by his resolute sense of calling. He stated when interviewed in 1979:

Sometimes people of another group have the fear that they are going to have others thrust themselves upon them or in their presence. This is what people don’t want. They like their freedom. If this was the case, I tried not to force myself to be around or in the presence of people unless I was sure that my presence was wanted or would be acceptable. So I had to maintain an attitude of individuality.

“Maintain an attitude of individuality” is a euphemism for isolation. Nowhere is Chaplain Brown’s strength more apparent than in his successful handling of isolation occasioned by discrimination. When asked about the climate of segregation he found in 1944, he said:

I was the only Black officer or chaplain in the area at the time. Although Chaplain Parham came to Williamsburg after I did and came to Great Lakes before I left. I was always by myself so far as being among officers and chaplains is concerned. I was by myself particularly in Williamsburg. Of course the city of Williamsburg was segregated. You even had separate seats to sit around separate trees at the Post Office. It was expected. It was the usual experience.

Acknowledging the status of being a naval officer was extremely awkward for Chaplain Brown. One day he was walking down one of the streets of Williamsburg when a tall, blue-eyed, White soldier approached him. Chaplain Brown was so accustomed to being ignored by everybody that he had conditioned himself not to be aware of others on the street. It just didn’t “do” for a Black to call undue attention to himself. Suddenly, however, the White enlisted man rendered a tremendous salute. Chaplain Brown was so startled he couldn’t respond, but simply walked by. The experience never left him. He later reflected:

How I regretted the incident! I’ve prayed about that a million times since, because I felt so sorry for the fellow who didn’t received a response from me. I’ve used it as a illustration in sermons many times, to point out how we can condition ourselves negatively; and when a positive situation comes along we are not able to respond…

Never again would he fail to realize his role and the opportunity for “positivizing” that it presented.

Minority Affairs. Chaplain Brown was initially detailed to the Office of Naval Office Procurement, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and later Detroit, Michigan, for the purpose of investigating incomplete applications of minorities for entrance into the chaplaincy. There was some question at the Bureau of Naval Personnel and at

5

the Chaplain Division as to why some applications from Blacks had been halted in their processing. Chaplin Brown’s duty was to search out whether or not there were any interferences or limitations being imposed on these applications. In order to do this he was granted wide access to appropriate files and direct communication with the Chief of Chaplains. He served in this capacity until September 1944. Asked whether he found clear cases of discrimination, he replied that he did not. He did find some instances of delays in processing, and several cases where ministers had second thoughts after having made application. Most applicants did not feel wanted.

Confident and Courage. From September 1944 until June 1945, Chaplain Brown served in Camp Robert Smalls at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. One benefit he derived from this tour duty (although Camp Robert Smalls was predominately occupied by Black personnel) was the realization that he was to serve all naval personnel and not just those of his own race.

One Sunday after the worship service, when Chaplain Brown had the base duty, he received a call from a neighboring camp. There a young, homesick White serviceman was upsetting the barracks. Neither his friends nor the company officers could stop the disturbance. When they called the duty chaplain, they didn’t know he was Black; but when he appeared, they did not care provided he could help bring some peace to the area. Chaplain Brown gave this account:

It really was kind of forsaken at the young man’s camp. So they left me with him and I took him by the hand and talked to him of the loneliness I had felt as a student at Howard University during Christmas vacation when I had the flu and was far from my home. I wanted to be home so badly I began to think that if I could just wish hard enough, I could be. I knew what homesickness was because I had experienced it, so I talked to this load and got him to stop crying. I don’t know how long he remained quiet but by the time I left he hadn’t begun again. He was White, young, and I did a good job. Even if I do say so myself, I was successful! That was a unique experience, unique in that I was the only person [chaplain] available and they needed the right help, not color, and I did the job!

In 1945, he was approached at Camp Robert Smalls by an impressive Black enlisted man who was obviously distressed. He told Chaplain Brown that, although he knew a chaplain could not do anything about it, he wanted to report that the Blacks were going to tear down a refreshment stand was situated exactly between a Black and a White camp and should have served all equally. The girls serving at the counter, however, either made the Blacks wait until last to be served or refused to serve them at all. The Black sailors found this degrading, and determined to take action on a certain evening. The sailor who came to the chaplain thought he would understand and perhaps help in the disciplinary procedures that would inevitably follow.

But Chaplain Brown had other alternatives. He requested the help of his senior chaplain, J.D. Johnson; and their efforts finally involved the base commander, who contacted the railroad. The operators of the refreshment stand were replaced immediately. Fairness prevailed, and the riot was avoided. Chaplain Brown reasoned:

6

Perhaps we prevented a riot, the loss of lives, and bitterness between people. The Chaplain Corps, deserves credit for that. I think Chaplain Johnson deserves the credit. Things like that, however, don’t get much attention, but sometimes the things that are prevented are more important than the things that occur!

Service with Sensitivity. The progress Chaplain Brown sensed was more than sociological—it was spiritual; and it continued as he developed as a chaplain and as a naval officer. In July 1945, he journeyed to Guam in the USS ALTAMAHA (cve-18). On the first Sunday in transit the captain sent word that he wanted Chaplain Brown to bring the message the next Sunday. Chaplain Brown was shocked. The ship had a chaplain, he reasoned; and there was also a White chaplain in transit. Additionally, most of the officers and crew were White, since the majority of Blacks aboard ship during those days were stewards. The common assessment was that Blacks were not welcome in the Navy in any capacity except as stewards or as stevedores.

The impact of the request was even greater when Chaplain Brown realized that Holy Communion was to be observed. He knew that the fulfillment of his ministry on that particular Sunday would make a profound spiritual statement of his dignity as a man and as a pastor. In his characteristic self-deprecating way, he said:

When I came to this particular service on the ALTAMAHA, I was facing a somewhat lean situation in terms of the presence of people of my own sort. I must say the attitude of the chaplains on the ship and the attitude of the captain were such as to make me feel wanted and much at home in trying to perform a service according to the assignment. I led the communion and was assisted, of course, by the chaplain of the ship. A sacred attitude prevailed due greatly to the attitude of the audience. They seemed to be used to and hungry for worship. This preparation was due, of course, to the activities of the chaplain of the ship and the worshipful attitude of the captain himself. This was a very significant service to me because it was a far cry from non-participation, or lack of presence of a Black, to say nothing about bringing the primary message on this first Sunday, the communion Sunday, handling the elements and their being received so humbly by the enlisted men and officers who were aboard ship.

The spiritual impact of the first Black chaplain on that Sunday could be deduced from the fact that the captain asked him to lead the service again the next Sunday despite the presence of two other chaplains. Although Chaplain Brown was sensitive to the feelings of the feelings of the other chaplains and initially demurred in their favor, he agreed to preach again. He had discovered the dignity of acceptance.

Influence and Example. The courage displayed by Chaplain Brown at Great Lakes was undoubtedly a factor in his being sent to Guam, Mariana Islands, in 1945 where racial tensions had led to disorder. There at Camp Wise, another largely Black camp, he performed a ministry of amelioration and reconciliation.

His seven months there swept by rapidly. By the February 1946, Chaplain Brown was returning home to be separated and to embark upon a distinguished career as a civilian pastor.

Prudence and Perspective. The prudence and mature thinking of Chaplain Brown were an asset to him and the Navy as he ministered during troubled times. Like his prophetic predecessors, he took the long in race relations. He gave his

7

best in loyal and humble service, taking advantage of each opportunity as it came, and building a foundation for those who would follow him. It is an injustice to judge him wholly from the relative safety of more recent times. He truly did the work of a pioneer. Hear him:

I had to maintain an attitude of individually…

They needed the right help, not color…

Sometimes the things that are prevented are more important than the things that occur

Perhaps his greatest contribution as the first Black to serve as a Navy chaplain was his successful effort to bring increased dignity, stature, and meaning to the title: United States Navy Chaplain.

8

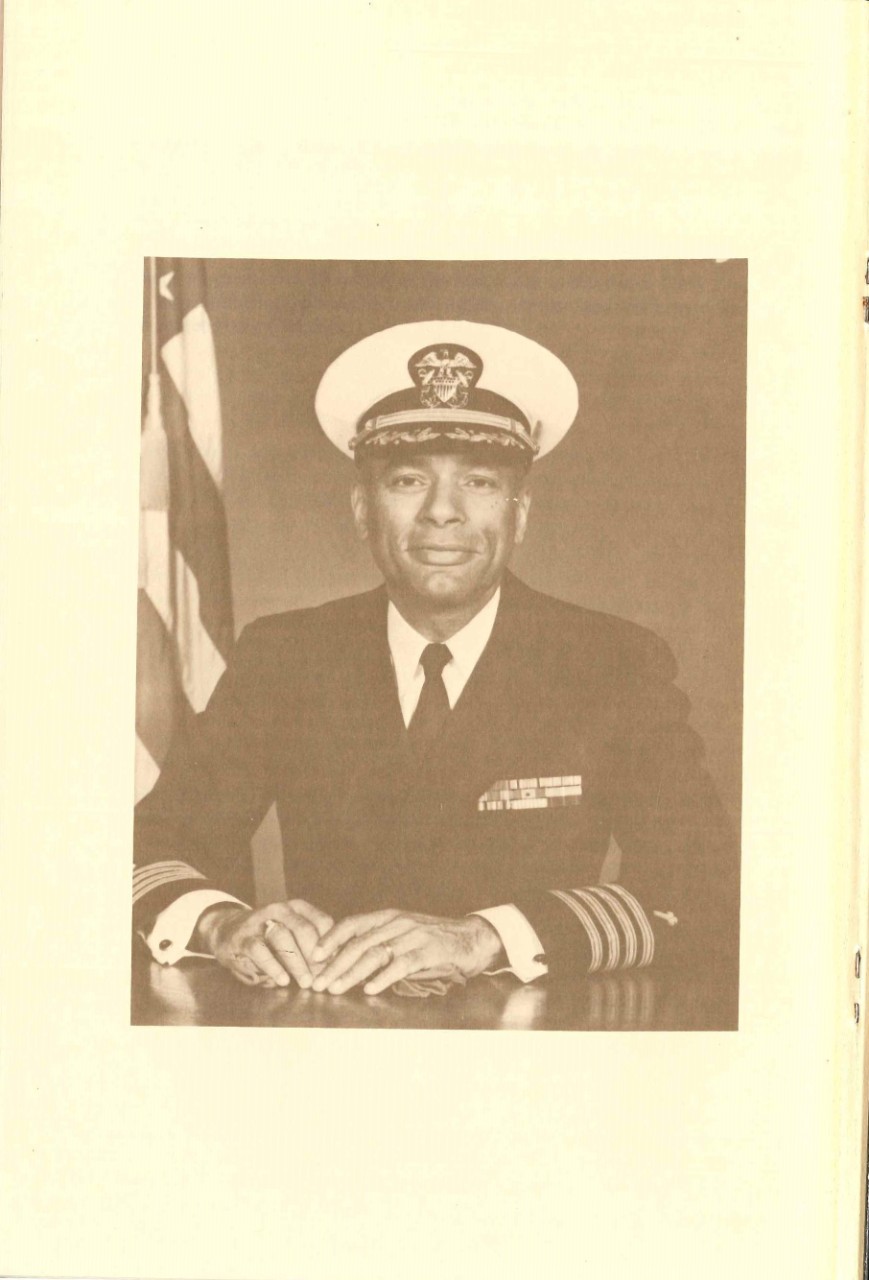

THOMAS DAVID PARHAM, JR.

Birth

21 March 1920, Newport News, Virginia

Education

Hillside High School, Durham, North Carolina; Valedictorian

North Carolina Central University, Durham, B.A., 1941, Magna Cum Laude

Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; S.T.M., 1944;

M. Div., 1969

American University, Washington, D.C.; M.A. 1972; Ph.D., 1973

Family

Marriage: 1 June 1951 to Eulalee Marion Cordice

Children: Edith, Evangeline, Mae Marion, and Thomas David III

Ordination

17 May 1944 by the United Presbyterian Church

Active Commissioned Service

December 1944-August 1946; January 1951 to the present

Promotions

Lieutenant (junior grade), 26 August 1944

Lieutenant, 5 July 1951

Lieutenant Commander, 1 July 1955

Commander, 1 July 1960

Captain, 1 February 1966

Previous Duty Assignments

Naval Training School, Hampton, Virginia

Naval Training Center, Great Lakes, Illinois

Manana Barracks, Hawaii

Naval Supply Center, Guam

Charleston Navy Yard, Charleston, South Carolina

Fleet Activities, Sasebo, Japan

Naval Air Station, Iwakuni, Japan

Menniger Foundation, Topeka, Kansas

First Marine Division, Camp Pendleton, California

Amphibious Squadron ONE and Marine Corps Recruiting Depot, San Diego, California

USS VALLEY FORGE (LPH-8)

Naval Air Station and Commander Fleet Air, Quonet Point, Rhode Island

Bureau of Naval Personnel, Washington, D.C.

Naval Training Center, Bainbridge, Maryland

Present Day

Chief, Pastoral Care Service, Naval Regional Medical Center, Portsmouth, Virginia

11

Ministry in the Making. Thomas David Parham had always been drawn toward the ministry. His uncle, also named Thomas, was the pastor of a church in Durham, North Carolina. While serving in that capacity, the uncle lived with the Parham family. With the father of young Parham gone to work each day and his mother busy with her homemaking, his uncle Thomas was more readily available to him.

He was later recall:

Knowing what I now know about identification, role models, and the like. I know that this [relationship with my uncle established my predominant interest in going into the ministry…I did know this until 1966 when I went to the Messenger Foundation to study marriage counseling. As early as I can remember, I wanted to go into the ministry.

Parham had outstanding academic records in the high school and the college available to him; but it seemed unlikely that he would be allowed at any of the several major universities and seminaries he might have chosen. After graduation from North Carolina Central University in his home town of Durham, he secured a scholarship grant and attended the Western Seminary (presently the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary) of the Presbyterian Church.

The Challenge of the Chaplaincy. Although five other members of his seminary class entered the naval chaplaincy upon graduation in May 1944, Parham was told that his application could not be accepted. He continued his work in a student pastorate in Youngstown, Ohio. During that summer, he saw a newspaper photograph of Chaplain J. Russell Brown, who had been commissioned on 4 July of that year. Parham went back to Pittsburgh and asked why he was unable to enter while other Offices of Naval Officer Procurement were accepting Blacks. Parham recalled that the same young lieutenant who earlier rejected him was there, and that after listening to the question he said, “We can take your application now.” Promising the church at Youngstown that he would return to them after the war was over, Parham entered the Chaplain Corps in December 1944. By barely six months he was the second Black Chaplain in the U.S. Navy.

Chaplain Parham tells why he decided to enter the Navy:

The thing that finally motivated me into going into the service was an incident at the railroad station, the Lake Erie Station. A group of draftees was leaving, and one of them was Shed Bell who was the brother of Tommy Bell who fought Jake Lamotta. I had officiated at his wedding, and I was down there to see him off. As I was about to leave after the train pulled out, a young mother who had just seen her son off, with tears streaming down her face, looked right at me and said, “What’s wrong with you?” I said, “Nothing, not a thing.” And it made such an impact on me, I said, “Well, I’m not married, no physical problems, and they do need chaplains”-so I decided to go on into the service.

Army life did not appeal to him, and so when the Stated Clerk of his General Assembly mentioned that there was greater need for chaplains in the Army than

12

in the Navy, Chaplain Parham told him, “Either I go into the Navy or I just won’t go in at all. [I’ll] just stay home.” That kind of intractability would irritate some, but was to benefit many who would look to Chaplain Parham for pastoral guidance and encouragement.

After a break in active duty between August 1946 and January 1950, Lieutenant Parham became the first career Black Chaplain. This young pastor had a commitment to the Navy that was to grow stronger and stronger over the years.

Discrimination and Discouragement. Although there was little discrimination in air travel. Blacks could not ride in the front seat of buses or trains during World War II; and there were separate public rest rooms. The Navy was unprepared for integration and Blacks were often billeted in segregated quarters. Chaplain Parham originally was denied use of the Bachelor Officers Quarter and the Officers Club. From the perspective of the nineteen eighties, he is philosophical about those years, and one might suppose that he was to some extent even then. He recently reflected:

The Country has improved; in fact, I think it has followed the lead of the military on the racial thing; because for most people in the forties the military was the first, integrated experience of any kind that they had.

The Chaplain Corps fared better than most communities in its attitude toward racial equality. Although Chaplain Parham received and overheard remarks that patronized or slighted Blacks, chaplains were relatively open about their feelings and few seemed prejudiced. In fact, young Parham considered that he had more trouble with inequality from an organizational standpoint than from personal bias.

Chaplains School presented the first hurdle. It is there that the beginning chaplain often forms his self-image and his image of the Corps. Chaplains School, therefore, can influence a career for good or contribute to its short duration. For Parham, it was a more significant testing ground than for some others. He remembered having resentment in some situations in which he felt subordinated, but quickly admitted that such feeling was perhaps due at least in part to the tension he was experiencing, Chaplain Parham has demonstrated that a difficult and negative beginning can be constructively handled.

The unpleasantries[sic] he experienced, plus his promise to return to the church he had served in Youngstown, impelled him to leave active duty in 1946. His disappointments are easily understood: ministering to the exclusively Black Camp Smalls at Great Lakes; being ordered to other Black units at Manana, Hawaii, to help avert a potential racial riot; following Chaplain Brown to Guam to minister again to exclusively Black units; struggling with billeting inequality; and never being welcome in the Officers Club. He observed:

It was the same type of situation at the Charleston, Navy Yard to which I returned in 1946… We had had it at Great Lakes, Hawaii, and Guam… Instead of assigning me to a chaplain’s office, they relieved the chief steward of his office in the stewards’ barracks and gave me that for an office—in the stewards’ barracks! The senior chaplain wanted me to organize a Black service in the stewards’ barracks, but I didn’t have the interest in doing that. But I

13

announced it, put it in the Plan of the Day and that kind of thing, and nobody showed up. So the next Sunday they sent me to preach in the brig; I never did preach in the Chapel. ..I did have one wedding there (a Black steward’s mate and his Black bride)…there didn’t seem to be ay objection to that. But I couldn’t go into the Club, couldn’t stay in the BOQ, and that just wasn’t the way I wanted to live.

Upon his release from active duty, Chaplain Parham returned to Youngstown, where he served as pastor from 1946 through 1950 while remaining in the Naval Reserve.

The Changed Climate. Chaplain Parham returned to active duty in January 1951, soon after the outbreak of the Korean War1 . From 1951-56, he was the only Black chaplain on active duty. His anxiety as a Black professional, competing in a system effectively controlled by Whites, was still present, although progress had been made. President Roosevelt had begun the abandonment of segregation in the military service, and this had continued with varied intensity under his successors in the White House. The concept that “Black chaplains are for Black sailors” was progressively and appropriately being dispelled.

At one point during his earlier service, Chaplain Parham had thought that his color would prevent his receiving sea duty. With this impression he had proposed marriage to Eulalee Marion Cordice. The supposition had risen when Chaplain Parham was returning from Guam as a passenger in a ship early in 1946. The ship’s chaplain requested early detachment in order to attend school in Copenhagen. Since Chaplain Parham had until summer before his release from active duty, he asked the district chaplain if he could fill the unexpired tour of duty. The district chaplain left him with the impression that a Black chaplain would never to go to sea. He was later ordered to sea, although even then an active duty captain complained to the Chaplains Division, reminding the detailer that Parham would be the only chaplain in the ship for the entire crew and that the Black sailors in a ship numbered only a few stewards. This implied that Black chaplains were only for Black sailors. Chief of Chaplains Stanton W. Salisbury answered that captain’s complaints and wrote an article in the Christian Century in which he affirmed that the Chaplains Division had no plans to give Chaplain Parham any segregated duty. This was as public and as courageous a position as could be taken by a chief of a military section, and indicated progress both in the Chaplains Division and in the Navy.

Earlier, in 1952, when Chaplain Parham had returned to active duty and had completed two years at Great lakes, he received orders to the First Marine Division and made all preparations to go. The orders were suddenly cancelled, however, and he was sent to Sasebo, Japan. He would have been, of course, the first Black chaplain to serve with the Marine Corps. Referring to the incident, he said:

I heard a lot talk about the Marine Corps and Black officers, but I never did know what the deal was. I thought that either my orders were cancelled after they saw my picture, or that my senior chaplain, Frank Hamilton, was a little unwilling for me to get hurt down there, perhaps because he felt sorry for my wife Marion. I didn’t know what happened.

-----------

1Stanton W. Salisbury was Chief of Chaplains, and John Wesley Rogers was Chief of Naval Personnel.

14

Chaplain Parham did eventually serve with the First Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California, and successfully, both from his viewpoint and that of the Marine Corps. Times were improving; yet the new Lieutenant Commander Thomas D. Parham, his wife, Marion, and their bay girl never know when they would be made to feel like second-class citizens or experience demeaning condescension. This remark, for instance, by a recently arrived chaplain’s wife to other chaplains’ wives, was inadvertently overheard. “Yes, you know, no matter where you live you always have the chance of niggers moving next door.” Remembering that remark, Chaplain Parham would comment; “That chaplain is out of the Navy now; and it’s probably just as well, because the climate has changed.”

But the climate had not changed sufficiently in 1957 to forestall a well-meaning and well-liked senior chaplain from remarking to Chaplain Parham. “You know, if you ever do happen to make commander, you will really have arrived”; or for a Marine colonel to write in his fitness report, “He is remarkably good preacher; and not only that, he’s a Negro.

Reflection upon these circumstances led Chaplain Parham to the conclusion that he had to develop a pattern of patience and endurance. This meant that he would choose to endure expressions of racism rather than to challenge them directly. Chaplain Parham’s comment on this matter is instructive:

I’m not outwardly aggressive by nature because the problem with aggression is that in the North Carolina of my youth, it could get you killed very quickly… I’ve had to think in terms of long-term goals, and I’ll try to convince the Black sailor I counsel that if he wants to get a career out of this thing, then the best way is to not get into trouble in the first place, and to control his anger; because anger is a tricky ting. It is said, you know, “Whom the gods would destroy they first make angry.” And that’s true, and I’ve always remembered that, because anger makes you stop thinking. To have control, reasonableness and calmness is not just wise; it’s a matter of survival…I’ve often ad to swallow my pride, but I’ve never digested it.

Experimentation and Innovation. Perhaps the best test of any man lies not in his apparent talent, but in what he does with his opportunities. When Chaplain Parham approached his duty in Sasebo, Japan, the situation looked overwhelming. The Senior Chaplain assigned him the ministry to the ships in the harbor. Due to the Korean Conflict, large numbers of ships were consistently in the port. The young chaplain identified three ships each Sunday, took a portable organ and an organist, hand held services in each ship, often moving by motor whaleboat from one to another. Very shortly, however, the organist was transferred. Since he had always believed that music plays a significant role in worship. Chaplain Parham concluded that he had no choice but to learn to play the organ himself. He mastered three hymns, the Gloria Patri, and the Doxology. He reflected later that, “for ninety ships those three hymns were played over and over until I learned to play three more. Then I could double back on the other ones. By the time I left Sasebo, I had learned twenty-two hymns, which were enough to keep me going!”

In 1956, when assigned to the First Marine Division of Camp Pendleton, Chaplain Parham continued to take advantage of his opportunities. He vigorously joined all the Marine activities that he could, being convinced that such involvement

15

enhanced his ministry. He confided, “I got a 231, I think it was, on the rifle range which required a 250 for perfect; and my colonel would say to the Marines. “If that old man can do it, anybody can do it!”

One of Chaplain Parham’s most admirable qualities is his utter freedom from complaint or excuse. One of the principles by which he operates is caught up in his statement: “I take what the Lord sends.”

When attached to Amphibious Squadron ONE as senior chaplain, (1960-62), Chaplain Parham and one subordinate Protestant chaplain had eighteen ships for which they were responsible. When the ships were in port it was impossible for the chaplains to conduct Sunday worship in all of them. Chaplain Parham improvised by having the Floating Christian Endeavor, an evangelistic group from the Scott Memorial Baptist Church, conduct worship on the ships not visited by a chaplain on a particular weekend. The fervent evangelistic approach of these teams occasioned some criticism; but when Chaplain Parham was addressed by those with complaints, he would reply that when you contact churches for help in providing worship for all, you take what the Lord sends. He elaborated:

Whenever I get an enlisted person now that doesn’t work out too well I tell myself, “You have to take what the Lord sends, “When our detailer asks me if I want a certain chaplain t work for me, I tell him, “You can’t send me a chaplain I don’t want, no matter what the situation is. I take what the Lord sends.”

The Lord continued to send a great deal toward Chaplain Parham, and he was quick to receive anything that could benefit his people. When assigned to the USS VALLEY FORGE (LPH-8) in December 1962, he inherited what was described as a “beautiful shrine area,” on the hanger deck. There was a triptych made of anodized aluminum, each panel fifteen feet long and seven feet high, with stained glass all the way across the top and a back-lighted picture of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane in the center. A fourth panel formed a roof by a suspension arrangement. Its location made it a focal point on the ship. It also made an excellent setting for groups, a fact not lost upon the Chaplain. He remembered:

My first Easter on the ship was spent in ort in Hawaii, and a providential thing happened. The University of California had a women’s chorus on tour and they were doing a concert on Sunday night at Barbers Point Naval Station, so I got them for Sunday morning. Can you imagine, thirty-five or forty girls in pastel pink and green dresses on a Sunday morning in Hawaii, singing for church in our beautiful shrine area! I had twenty-five or thirty of our personnel lined up as escorts after the service for a tour of the ship, and the girls also had dinner with us. It was memorable day.

Before the ship left the harbor Chaplain Parham had also supervised the appearance of the Hawaiian Dance Group from the Church College of the Pacific in the same shrine area. He recalled with obvious enjoyment:

So we got fifty or sixty hula dancers on our ship. So they came out aboard, grass skirts and leis and the whole bit… This was another kind of scoop situation that didn’t happen anywhere else, and hadn’t anywhere else. It was good for the ship, and surely enhanced the chaplain in the eyes of the crew.

16

Care in Counseling. Chaplain Parham also made contributions in the area of counseling. He had the privilege of training at the Menninger Foundation, and described that experience as having been most helpful. He expected younger Blacks to look to him for direction and even for a philosophy of life, and they did. They did not always take the counsel, especially during the turbulent times of the sixties and seventies; but it was always there and always consistent.

Chaplain Parham advised his commanders with directness, insight, and honesty. There was a time, for instance, when compulsory chapel attendance for new recruits was attacked almost everywhere as limiting individual freedom. Chaplain Parham maintained that exposure to religion in basic training was part of the whole military package. In recruit training one doesn’t have a choice about class instruction, drill, exercise, or uniform. Why should he have a choice about whether or not he attends religious services (i.e., apart from which service)? He recalled his duty with Marines during the controversy:

My colonel, Frank R. Wilkinson, agreed with me. I had him in the pulpit every Sunday to welcome the new recruits who were in church, and he always told them. “Young men, get acquainted with the Lord while you’re here, so that when you call on him or strength, he knows who you are; so that when you call upon him in combat, you will not call upon him as a stranger.”

There are those who evaluate the effectiveness of a counselor by the extent to which his counsel is transmitted to others. In this respect, Chaplain Parham has enjoyed enviable success. One incident is cited. He gave instruction for baptism to a recruit; and as final preparations were being made, the recruit asked if his buddy could be baptized, too. The chaplain mentioned that the buddy had not had any instruction. The young man replied, “Well, I’ve taught him everything you taught me.” About the time of the baptism, the chaplain asked the Marine what he was going to do after his baptism, and the Marine blurted out, “I’m going to take some leave, and I’m going to get my mother squared away. “Chaplain Parham commented on this:

That’s an example not only of the chaplain’s influence, but of the comprehensive influence of the Marine Corps. General Krulak’s graduation speech was a classic. He told them to have faith in God, in their country, in themselves, and in their Marine Corps buddies. Four building blocks of the future, all in a neat and workable package. The men believed him, too.

In the late sixties and early seventies one of the greatest difficulties in counseling on the part of chaplains had to do with the problems of race. A Black chaplain serving during that time had unique involvement. Chaplain Parham’s counseling under those circumstances reflected his values and approach. On one occasion he was visited in his stateroom in the USS VALLEY FORGE by five non rated, Black sailors who announced to him that they had checked with the Black members of the Marine battalion riding the ship, and they had all agreed that they were going to take over the ship. They excepted Chaplain Parham to assume command.

In his calm and measured way, Chaplain Parham carefully explained to them that he knew no navigation and did not know where they were in the ocean, that there would be no replenishment of food or fuel since they were dependent upon the

17

Navy for all their provisions, and that a takeover would therefore be a disaster. He later recalled, “They were really crushed. They were surprised that I was not equipped to take over the ship, and I found it hard to explain to them that chaplains don’t get that kind of training.”

Chaplain Parham knew that he could do no better than to acquaint the sailors with reality. Unfortunately, it did not stop a riot from occurring when they arrived at Subic Bay. When the same seamen were charged with inciting to riot, the chaplain followed their legal processes carefully, giving personal assistance; but he never referred to the night when he was asked to become the commanding officer of the USS VALLEY FORGE.

Those were traumatic years, and many of the disturbances had racial overtones that spread rapidly. Chaplain Parham remembered:

…As news travelled it got amplified, but on our ship it was more a matter of saying that since other ships had riots we ought to have one. I think it was just that simple, because we didn’t have any real problems on our ship. The men just didn’t want to be outdone.

This analysis might seem simplistic to some, but the times were such that serious and disturbing national and military questions centering on the Vietnam conflict called all authority into question.

This was especially true of younger enlisted personnel who were undereducated draftees or high school dropouts, and who came primarily from the streets of the nation’s larger cities. Chaplain Parham had little difficulty offering his experienced counsel to these persons. He had been initially assigned to the “knucklehead battalions” at Great Lakes in 1945. He then served the stevedores in Hawaii and logistic support companies in Guam. In those early years he often got people of limited education because they were mostly Black and poor. They would either gravitate to him or be diverted there. He said:

I learned to appreciate what some people refer to as the rougher or the coarser element, because they are usually very open and above board. If they don’t like you, they cut your throat; and if they do like you, they cut somebody else’s throat. At least

Anyone who counseled during the turbulent years of the late sixties and early seventies remembers that there was very little patience for abstract beating around the bush. It was not surprising that Chaplain Parham was often queried on the character and purpose of Black Power, since he was by that time part of, and very successful in, “the system.” His answers were forthright:

I always told people who talked about Black Power, “There is where it is; stripes on the sleeve!” I said to them, “I sign documents for the Chief of Chaplains and I can tell other chaplains to jump and they say, “How high?” That’s Black Power! And I’d say, “If you want to get in one the power structure, the military is where it is because in every civilized country the military is either number one or number two in the power system. You’re never far outside the main power stream if you are in the military.” The principle is that the individual can go as far as he wants to or has the opportunity. It’s not so much a question of Black Power as it is the power of the Black who achieves! And when the discontented guys in the service came to me, I’d say to them, “Now if you were the commanding officer, things would be different

18

here, wouldn’t they?” And they’d say, “Yes, very!” And I’d say, “O.K., you be the commanding officer! Admiral Zumwalt didn’t like the Navy the way he saw it, either. And when they made him CNO he got us a brand new Navy. Not everybody was happy with it, but he was.” And that’s what I try to get across to the young men who are disconnected in the service or with the service. The thing you must do is get to the place where you can influence the system.

Promotion and Progress. Chaplain Parham likes to tell the story of how he bought a set of golf clubs because the station’s commanding officer and the admiral at Quonset Point, Rhode Island, where he next served, both played golf, and he thought golf might be a good sport.

While at Quonset Point, Chaplain Parham was promoted to the rank of captain, effective February 1966. He was the first Black Navy captain.1

Since selection to rear admiral is unlikely in an organizations as small as the Chaplain Corps, Chaplain Parham might have been tempted to relax and enjoy his position, but he did not. The first thing he did at Quonset Point was to begin an early Sunday morning worship service which he publicized as the “golfer’s service.” It seems that the station’s commanding officer, when presented with the idea of an early service, asked if he could come to church and still tee off at 8:30. Assured that he could, the commanding officer strongly supported the innovation.

The ministry of Chaplain Parham at Quonset Point was characterized by impressive music, earnest preaching, and active home visitation. Chaplain Parham’s outreach extended to the Chaplains School in Newport and to the civilian community. In support of the training program at the Chaplains School, Chaplain Parham hosted helicopter familiarization flights at Quonset Point Naval Air Station.

Human Relations and Recruitment. In 1967, Chief of Chaplains James W. Kelly had Chaplain Parham ordered to Washington as his Assistant for Plans and as Assistant for Human Relations in the office of the Chief of Naval Personnel, Vice Admiral Benedict Joseph Semmes. He was especially qualified to serve the Chief of Naval Personnel in his assigned area and was able to make significant impact upon the entire service. He took the opportunity to articulate his philosophy of human relations:

Over twenty years ago I went from Guam to Saipan to visit a unit which had recently moved to Saipan from Guam. The island commander met me and asked why I had come. I explained that it was a sentimental journey to see old friends. He told me that if I had come to preach I was welcome; but if I had come to add to the racial ferment that had begun to disturb the island, I was welcome to leave.

Religion for him was not relevant to the social situation. He reflected the opinion held by many sincere people of that period both within and without the military structure.

Chaplain Parham knew that the ideal racial and human relations situation did not exist in the Navy, and he saw his own assignment as indicating that fact. The assignment, however, was precisely in keeping with two of his ideals; the striving for

-------

1 According to some sources, Robert Smalls, a former slave, became the first Black Navy captain; but the story is not based on fact.

19

growth in human relations and the involvement of chaplains in that process. Chaplain Parham was and is a synthesizer. He continually sought to conjoin all the convictions, virtues, and loves he embraced, believing in the unity of values that are right. He often reflected in his speeches and writings that the leadership of a chaplain implies involvement in efforts to improve human relations.

Navy chaplains have always been concerned with the whole man. They received much credit for the elimination of flogging from the pre-Civil War Navy, and they have characteristically heard and understood those who have been mistreated by others. Religious services were integrated long before the mess halls, the wardrooms, and the berthing areas.

The chaplain has had a distinct advantage in working in the field of human relations in that he is a clergyperson and therefore a peer to all other members of the clergy. Chaplain Parham once wrote:

The chaplain can encourage his civilian counterpart in the crusade for true brotherhood… He can invite his civilian counterparts, especially those from the minority community, aboard the station, or the ship when in port, allowing them to see for themselves the nearest thing that we have in our nation to an ideal society.

He insisted that the chaplain can become familiar with the ghetto, including its sights and its sounds. He can learn the language, and he can know the frustrations. After becoming conversant with the ways of the ghetto, Chaplain Parham affirmed, the Chaplain can instruct others. He said:

Through pulpit exchanges, church parties, reciprocal concerts by choirs and other singing groups, the two sides of the tracks may be joined by a bridge of mutual interest leading to mutual understanding.

Chaplain Parham relished the label of being a Navy recruiter and wore a recruiter’s emblem. He felt that since chaplains have always been volunteers, it should not seem incongruous that they should ask others to volunteer, especially when recruits could do their country a service while improving their own condition. He taught that it was usually good advice to suggest reenlistment to any person who came from a disadvantaged background.

At that time, the Navy was lowest of all services in minority representation. This made it difficult for the Navy to be accepted in the ghetto as an organization offering unlimited opportunity. He said:

Until Navy is composed of approximately the same percentage of persons from various cultural backgrounds as are found in the national population, it cannot be said to be truly representative of America and a valid picture of human relations at its best.

In this context he pointed out that the Navy was particularly short of chaplains from minority communities.

Chaplain Parham knew that occupational equality was not the ultimate answer, since for many servicemen their military duties account for only a third of their time. When work is secured at the end of the day, they return to their usual environments.

20

The Defense Department decided that it was necessary to take measures to help bring about open housing. Chaplain Parham was proud that chaplains were prominent in this drive. One chaplain in the San Diego area was able to change the minds of seventy-five percent of the landlords who had refused to sign open occupancy pledges. Chaplains also belonged to many civic, social, and religious organizations comprising the leadership of the civilian community. How explicit the chaplain was made a difference when social concerns were discussed. He was not vulnerable to community pressure; hence he could exert leadership without fear of reprisal. Chaplain Parham said, “Never has any prophet been as invulnerable as the Navy chaplain.” He continued:

The question may be raised as to whether the chaplain is being used as a tool of the establishment. I think the question itself is indicative of a misunderstanding of the situation. The chaplain by his voluntary service is not a tool of the establishment; rather, he is the establishment’s effective spokeman. The policies of the establishment are his policies; his goals and his aims are one with the military power structure. The aim of the military is power for peace internationally, nationally, and locally. The chaplain by his religion commitment is pledged to peace. Chaplains mediate a spiritual power which is more effective than temporal power. The power if a loving example is invincible. It is the chaplain’s privilege to be that example at work in the civilian community.

Upon the arrival of Chaplain Parham in Washington, the Chief of naval Personnel, Vice Admiral Benedict Joseph Semmes, established a schedule that required the chaplain to meet with him every Tuesday morning unless either of them was out of town. Chaplain Parham visited colleges and seminaries in the interest of promoting human relations and minority recruitment. Recruiting districts, learning that he was available, arranged television interviews, and scheduled banquets for community leaders, clergypersons, business executives, and school administrators.

The number of Blacks in the Navy was substantially increased as Chaplain Parham concentrated on correcting the image that the Navy had within the Black community. This was not easy. At times he was challenged by members on his Black audiences as if he had in some way sold out to the Navy. He recalled:

I used to say in speeches that the Navy was the closet approximation on earth that I knew of to the kingdom of God. That seemed to get some people. Yet at time I really thought that was true in makeup, tolerance, and opportunity—and I still say that there’s no living situation comparable to a ship where there are guys in berthing compartments three-deep, not assigned by any racial or ethnic or financial consideration at all. They are just there. Right there in the chow line—no differences, no special treatment. And they are within 800 feet of one another on that ship all the time, for months and months. You can’t think of a situation closer or more equal.

While such convictions may have been unpalatable to some, they struck a responsive chord in others. An article by him was published in the Naval Institute Proceedings, and he was invited to speak to such groups as the Presbyterian Ministers Fund Corporators Annual Meeting and at various colleges. Ursinus College awarded him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

Representing the Navy in this way was not always an easy experience for Chaplain Parham, because there was much anti-military sentiment in the late 1960s. He

21

met with an angry response at a community rally in Minneapolis and was refused admission to a meeting at Jesse Jackson’s church in Chicago. In the San Francisco-Oakland, California, area, Chaplain Parham encountered opposition by the press. When asked what he thought of the Black Panther movement, he replied that he admired their discipline and their military structure. He added that since there was a war on in Vietnam, a lot of them could be quite useful over there helping the war effort. The San Francisco Chronicle responded with a two-column headline on the front page, second session, of its next edition: NAVY CAPTAIN SAYS LE THE PANTHERS FIGHT THE CONG. Chaplain Parham explained:

What I meant was, if they wanted to fight somebody, we had somebody over there that was willing to fight. That’s where the war was, not in the streets of Oakland; and I felt that they were misdirected in their energy… But the media began to twist that to say I was in Oakland trying to recruit the Black panthers to fight the Viet Cong. And so we got orders from the Twelfth Naval District to make it perfectly clear on all news releases that we were not lowering recruiting standards, and were not specifically looking for Black Panthers; but anybody who could qualify we would be happy to have… [The media] did the same thing on the Associated Press coverage when I made captain. One of the photographers said, “Smile.” And I said I didn’t want ham it up for photographers and so they reported me as saying that I never smile! Nothing can be further from the truth.

It was not easy to be on display as much as Chaplain Parham was.

In addition to his activities in human relations and minority recruitment, Chaplain Parham was also part of the Bureau of Naval Personnel Drug Abuse Team, which traveled extensively, speaking to both officers and enlisted personnel concerning the growing drug problem. This increased his exposure, and also his impact.

Studies in Sociology. In 1970, when his tour of duty in Washington was substantially over, Chaplain Parham was sent to American University where he earned a Ph.D. degree in sociology. Vice Admiral Charles K. Duncan, then Chief of Naval Personnel, permitted this on condition that the chaplain would consent to stay in Washington for school and remain on active duty for five additional years. Chaplain Parham agreed, partly because of his personal respect for the Admiral. He has always had the greatest praise for Admiral Duncan’s control of situations, attention to detail, and comprehensive command of what was taking place around him.

Chaplain Parham disagreed with Admiral Duncan on one matter, however:

Admiral Duncan felt that we should not institute Reserve Officer Training Programs at various Black colleges in the South because the colleges were inferior and the students would come to the Navy handicapped because of that. They would not be able to compete in the Navy with graduates of the more advanced schools. I told him that his position was logical but not realistic because the competitiveness of a person based on his own motivation and desire for self-improvement ought to be given more weight.

I told him I had gone to a eleven-grade high school, a non-accredited college, and a small seminary in Pennsylvania; but I had still come out on top. When I went to seminary, there were guys from better schools and colleges there; but I was at the top of my class because I studied and I worked more than the rest of them, as God gave me strength.

I said that if somebody came out of Prairie View, we were considering him handicapped by a limited education. But once he got into the Navy, he could very well take off. I had experienced guys who had finished top-flight schools and had Hebrew and Greek and

22

other courses like that. While I knew I didn’t know anything, they thought they knew it. I learned it by extra effort, because I wanted to learn it; and that opportunity ought to be given to everybody. That was my only disagreement with Admiral Duncan.

Continued Contribution. Having concluded his tour of duty in the Washington area, Chaplain Parham was ordered to the Naval Training Center, Bainbridge, Maryland. He conducted a thriving chapel program until the base was disestablished, whereupon he was ordered to duty as Chief, Pastoral Care Service, Naval Regional Medical Center, Portsmouth, Virginia.

Chaplain Parham continues to serve his denomination on boards and committees. He is sought after as a speaker at seminars, breakfast meetings, rallies, and other occasions. In a soft-spoken, yet empathic way, he exemplifies unity within diversity. In occupation and in dedication he finds both his commitment to God ad his commitment to the Navy contributing to the social goals he has championed all his life—equality of opportunity and fair treatment for everyone. This had produced a remarkable single-mindedness, which has been reflected in his counseling and in his contribution to the Chaplain Corps and to the entire naval service. What makes consideration of his career especially refreshing is not his determined assault upon the current state of affairs, but the humor and candor, which have interlaced his efforts. Chaplain Parham’s recent reply to a question about the increase of Black opportunity during his lifetime demonstrates his abiding love for the Navy:

During my lifetime things have gone from almost zero to 85-90 percent for the Black community. It’s been uphill all the way. A good case in point: just now, the Secretary of the Navy, who is of Hispanic background, is in position where he can benefit greatly the cause of equality and opportunity for the minorities. He[sic] is now where policy can be made.

This is true of the Army’s Secretary, Clifford Alexander, who is Black. And that reminds me, I got into a rhubarb with him once after he had a speech with a idealistic description of what America should be like, in which he bemoaned the fact that it wasn’t yet that way. Well, afterwards during a question period I said to him, “Now about that description you gave of what America should be in terms of minority opportunity and initiative; that is exactly like it is in the Navy.” He looked like somebody had shot him. Then he came back with the question, “How many Black admirals have you got?” And I said (which was true at the time), “Well there’s nobody even eligible. I’ve been a captain longer than any of them, and I’m not even in the zone.” So that was my position on that! All that was required was time.

Chaplain Parham’s faith in the Navy has by now been justified by the promotion of Blacks to flag rank. Although he is not among those so promoted, he would be the first to be philosophical about that, and to reflect with gratitude upon the pioneering role that he has been enabled to play.

*U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1981 O--334-343

23