The Navy Department Library

Inquiry Into Occupation and Administration of Haiti and the Dominican Republic

67th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Report No. 794.1

Inquiry Into Occupation and Administration of Haiti and The Dominican Republic.

April 20 (calendar day, June 26), 1922 - Ordered to be printed, with illustration.

Mr. Oddie (for Mr. McCormick), from the Select Committee on Haiti and the Dominican Republic, submitted the following

Report.

[Pursuant to S. Res. 112.]

The select committee of the Senate to investigate the occupation and administration of territories of the Republic of Haiti and of the Dominican Republic by American naval forces presents herewith a report upon the occupation of Haitian territory and the relation of the United States to the Government of Haiti.

The Island of Haiti, midway between Cuba and Porto Rico supports a population as numerous as that of Cuba (about three and a quarter million souls) upon a territory about three-quarters as large as that of Cuba. It is therefore noteworthy in considering the economic and social condition of the inhabitants of the Island of Haiti that during recent years the export and import trade of the island has averaged perhaps one-tenth of the volume of Cuban foreign trade. Porto Rico, with a territory equal to one-fifth of that of the Island of Haiti and with a population of about a million and a quarter, has exported and imported about twice as much as has the neighboring island.

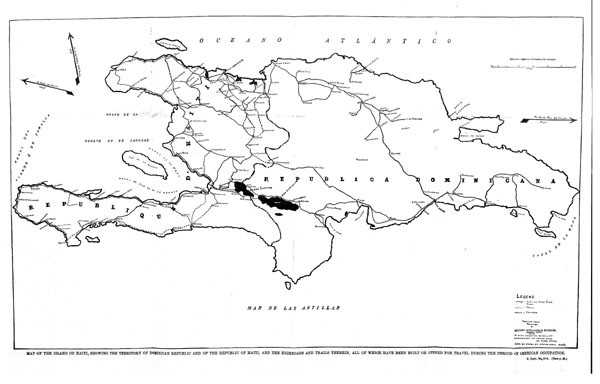

While the Cuban interior may be reached from all ports by connecting railways, and while Porto Rico is covered with a network of splendid highways, and while its ports are united by a coastwise railway system, the whole island of Haiti prior to the coming of the Americans in 1915 had absolutely no through and thorough highways and no railways other than half a dozen unremunerative, unsuccessful, and incomplete spurs of track running inland from different points of the coast. In a country without highways and without railways, and in which even the few trails were impassable during unseasonable weather, it is not surprising that agriculture, industry, and trade all languished and that the overwhelming majority of the population has been utterly poor and illiterate.

[start of page 2] The Economic Atrophy of Haiti.

Improved roads are an index to the industrial development of any country.

The French prior to 1800 had built about 550 miles of public roads in Haiti. Some of these were said by French writers to equal the best highways in France leading to the Versailles. The Haitians overthrew the French in 1804. The roads fell in disuse. The torrential rains which visit the island and the tropical vegetation which grows rapidly in the island soon made these roads for the most part almost impassable. When the Americans took possession there were not to exceed 210 miles of these French roads which were passable by wheeled vehicles even in dry weather.

The American authorities since their intervention in 1915 have built 385 miles of new construction and repaired 200 miles of old construction. Such highways as were passable even in dry weather were for the most part along the coast line. With these exceptions there was no way of getting to or from the coastal cities and towns to the interior except over trails through the forests no more clearly defined than were the Indian trails through the virgin forests of America before the white man had set foot therein.

Women and burros were the burden bearers of the country. All products which were brought into the market or taken into the interior from the coastal cities and towns were borne by the women carrying their burdens upon their heads or upon the backs of their burros.

The territory of the Republic of Haiti comprises one-third of the area of the island, the other two-thirds being included in the territory of the Dominican Republic. Three-quarters of the total population of the island inhabits the one-third of its area, which is subject to the sovereignty of the Haitian Republic.

There are two distinct social entities in Haiti - two Haitis as it were. One living in the coastal cities and towns. About 2 per cent, and certainly not exceeding 5 per cent of the total population represents the wealth and culture of the island. They embrace the governing class. They do not divide politically as our people do. The dividing line politically is between the "outs" and the "ins." A substantial army has been maintained by the government. Without it in the past no government could have come into existence or could have maintained its existence for any length of time. The "outs" seeking to get in have never hesitated to make an alliance with the Caco or bandit chiefs and organize revolutionary forces to march against the capital at any time they thought to be propitious.

The other very distinct element embraces 95 per cent or more of the entire population. They constitute the peasant class. They can neither read nor write. They have no conception of government. They have been the pawns of the governing class. Their condition is truly pathetic. Naturally generous and kind, with proper training and education they can become prosperous cultivators, capable of guarding their own interests.

Before the American marines landed in 1915 men did not dare to leave their humble homes in the interior recesses of the island lest [p. 3] they should be impressed into military service by either the government or the revolutionists. They knew not what hour of the day or the night they might be seized by military officers or Caco chiefs, taken from their homes and forced into service.

Their animals and the products of their little gardens were continuously being confiscated without compensation, and when the women took their produce to the markets in the cities and towns they were never certain that the little money they received for it would not be taken from them.

Now conditions are changed. Naturally, the peasants want Haiti for the Haitians. But at the same time, with very rare exceptions, the peasant class realize that since the American intervention for the first time in their history they are free from impressment into military service. They are no longer plundered by Cacos and bandits, and they are secure in the possession of their families and their property.

Haitian government prior to 1915 afforded neither protection nor service to the Haitian people. The Haitian peasant was burdened with heavy taxes, and for the most part no account was kept of the receipts or disbursements. No police protection was furnished the people in the interior. Hospital facilities in the cities and towns were inadequate and insanitary. No internal improvements were made for the benefit of the people.

One single disclosure made during the course of the hearings in Port au Prince will be interesting. It is typical.

Doctor Sylvain, president of the Union Patriotique was before the committee. He was asked concerning their educational system. He testified that the Republic of Haiti had compulsory education in the island since 1864; and yet only 2 per cent of the people can read and write. What a commentary on Haitian administration!

Under Haitian government teachers of music were hired who could not tell whether a sheet of music was right side up or upside down; teachers of drawing who could not draw a picture of an ordinary bucket; and in their courts subordinate judges who could neither read nor write. And it may be said that no other branch of governmental activity was far in advance of their educational system.

One word as to the material progress of the peasant class. Before the American intervention few of the Haitians had ever seen a plow. The peasant class had never seen and did not know how to use a shovel. At first when shovels were given to them for use they would take them to a pile of gravel, pick the gravel up in their hands, put it in the shovel, and then carry it to the place where it was intended to be placed. When the American marines began road building in the island, a schooner with road-building machinery was docked. In the hold of the vessel were 60 wheelbarrows. A captain of the marines in charge of the road building sent the foreman, a Haitian, with 60 men to bring the wheelbarrows to the place where the road building was in progress. After a time he looked for the men with the wheelbarrows. He saw them carrying the wheelbarrows on their heads instead of wheeling them.

The committee does not refer to these conditions in a critical spirit, or for the purpose of humiliating the Haitians, but because [p. 4] it is necessary that the American people shall know conditions as they are in order to enable them to determine what ought to be done at present and in the immediate future, and the committee says this looking solely to the benefit of the Haitian people and without any purpose, direct or indirect, looking to any material benefit to be derived by the Government of the United States from its temporary control or occupation of the island save and except such as would come to us as the benefactor of an unfortunate people.

No review of the condition of Haiti can be just to its inhabitants which does not recognize existing anomalies and the antecedent historic facts which explain the economic and political backwardness of a people among whom may be found groups whose cultivation, education, and capabilities are comparable with corresponding elements of society in more advanced countries.

At the time of the overthrow of the French government and of the expulsion of their French masters by the Haitians there were among the former slaves to whom the government of the country fell few who were literate and absolutely none who were so trained in public affairs or who were so skilled in tropical agriculture as to make possible either the successful maintenance of civil order or the necessary continued development of the country's agricultural resources. Thus the Haitians labored under insuperable handicaps. There were among them for all practical purposes no trained agriculturists and administrators, no engineers and educators. Haiti had no means of educating her people or of developing men competent to govern. Misgovernment and revolution ensued, and as a consequence Haitian trade, by comparison with that of the other West Indian Islands, diminished. Haiti drifted, as it were, out of the currents of commerce.

During the six score years of Haitian independence there have been a dozen constitutions. The people have lived under self-styled monarchs as well as under military dictators and self-constituted presidents.

Since the Haitians gained control in 1804 there have been one series of revolutions after another. Part have been successful, part unsuccessful. Since 1804 there have been 29 chiefs of state. Otto Schoenrich in his work on Santo Domingo says:

It is to be observed, however, that of the Haitian executives only one completed his term of office and voluntarily retired; of the others, four remained in power until their death from natural causes; 18 were deposed by revolutions, one of them committing suicide, another being executed on the steps of his burning palace, and still another being cut to pieces by the mob; five were assassinated; and one is chief magistrate at the present time.

The disorders to which Haiti has been subject since the achievement of its independence attained such destructive frequency during the last decade before the American intervention in 1915, that in the space of 10 years no less than eight presidents assumed office (it would be a mistake to say that they were elected) for the nominal constitutional term of 7 years each. Three of the eight fled the country; one was blown up in the presidential palace; another died [p. 5] mysteriously, and according to popular belief by poison, while two were murdered. The last Haitian President who held office before the landing of the American forces was Sam, who had caused several scores of political prisoners to be massacred as they huddled in their cells. He himself was dragged from the French Legation by a mob, his head and limbs were torn from his body to be carried aloft on sticks and bayonets, while his bleeding trunk was dragged through the streets of the capital city.

It will not be wondered that under conditions thus indicated the irrigation works and highways built by the French disappeared, fertile sugar plantations vanished, coffee cultivation ceased, and that the country made no progress, material or social, political or economic. The mass of the people - gentle, kindly, generous - their peace and property threatened rather than secured by the so-called authorities, sought such quiet as they might find by hiding in the hills, where they have lived in a condition of primitive poverty and ignorance. Not only did the sugar and coffee plantations disappear, but almost all true agriculture, all organized cultivation of the soil, except as little patches of yams and plantains may be called such, ceased. The coffee crop, which is the principal article of Haitian export, is gathered from the wild trees - sprung from the stock planted by the French over a hundred years ago. The domestic animals include wretched swine, poor cattle, poultry of scrawny Tropic strains, and little asses which, as saddle or pack animals, served as the sole means of conveyance or transport in the country until the arrival of the American forces.

No Representative Government in Haiti.

In brief, before American intervention there had been no popular representative or stable government in Haiti. The public finances were in disarray, public credit was exhausted, and the public revenues were wasted or stolen. Highways and agriculture had given way to the jungle. The people, most of whom lived in wretched poverty were illiterate and spoke no other language than the native Creole. The country and its inhabitants have been a prey to chronic revolutionary disorders, banditry, and even during periods of comparative peace to such oppressive and capricious governors that the great mass of the people who, under happier circumstances might have become prosperous peasant farmers, have had neither opportunity nor incentive to labor, to save, or to learn. They had no security for their property and little for their lives. Voodoo practices, of course, were general throughout the territory of the Republic.

This view has been contested by certain Americans who, equally ignorant of the facts and indifferent to them, have given voice to general and unsubstantiable charges which if credited would blacken the good name of the American Navy and impugn the honor of the American Government. It is, however, the view of your committee and is supported by those informed and impartial investigators of Haitian conditions, whose opinions have come to the attention of your committee.

Lest this summary of Haitian conditions be considered prejudiced or overdrawn, the committee quotes the following from the report of the Haitian Commission of Verification of Documents of the Floating Debt.

But neither the Pressoit-Delbau Commission, nor the successors of Mr. Barjon in the position of paymaster of the Department of the Interior have been able to tell the Secretary of State for Finance what has become of those archives. Only one fact remains, from all the preceding, and it is to be remembered; that is, that the said archives have disappeared, and that they remain unfindable, for a cause which the commission is not in a position to verify nor to comment upon.

This great question of the revolutionary debts - of the revolutionary debt of Davilmar Theodore above all - constitutes the most delicate and certainly the most painful of the work of the commission. Without doubt, we have not the mission, Mr. Secretary of State, to judge the motives, interested or not, which determined and guided the conduct and the acts of such a chief, of such a political group, in the course of the years forever ill-omened before the month of July, 1915. In any case, this mission is not imparted to us, if at least we confine ourselves to considering strictly and narrowly our attributions of commissioners charged to investigate the arrears of the floating debt.

This expression "revolutionary debt" carries in itself its condemnation, by reason of the lugubrious ideas which it awakens in the mind. From the moment that our internal torments had to have as a final consequence the issuance of certificates of indebtedness of the State, to the profit of their authors of all classes, or, which means the same things, the flood of favors to the detriment of the national treasury, a premium was thus created to the profit of Haitian revolutionaryism. And it is thus that we have attended in these recent times this sad pageant marking the pages of our history; the revolution of the day being an appeal to the revolution of to-morrow; insurrection never disarmed, always erect and campaigning, perpetually assailing the supreme power, and never stopping but to divide the spoils of the hour, after the enthronement of the new idol which it was to undermine and overthrow.

In presence of the figures at once scandalous and formidable of the debt called revolutionary and in view of the deplorable conditions in which the different original notes were issued, whether at Ouanaminthe, at Pignor, at St. Michel, at Cape Haitien, at Port-au-Prince, and even at Kingston (Jamaica), finally a little everywhere; some in Haitien gourdes, the others in American gold, pounds sterling, or in francs - the commission thinks its opportune to make without offense or passion the following remarks which it offers for the meditation of the country.

There is no really productive work without the help of capital.

But when the loan is contracted for an unavowable purpose, having for motive the arming of the citizens of a country against their fellows, sustaining a disastrous and debasing war, sowing terror in all the social levels, with a view of satisfying personal ambitions - oh, then the conditions are not longer the same, and we find ourselves here in face of a hidden operation.

Incontestably, wherever civil war has passed it has sowed destruction, disunion, and death; cities devastated, factories destroyed, families reduced to the most frightful misery, the pleasant fields of the north transformed into charnal places three or more years ago; all these horrors worthy of the times of antiquity and of savage hordes have caused and still cause the raising of cries of pain and of indignation, and retell for ages and ages the cruelty of the political leaders who conducted directly or indirectly the bands of madmen and who excited them to carnage in the sole and unique purpose of seizing the power for the purpose of better assaulting the Public Treasury.

The country can not make itself the accomplice of such financial disorder having hidden behind it crime and immorality.

The mass of notes issued, the considerable number of individuals who had or who arrogated to themselves the power of issue, and who unscrupulously, without restraint or the least reserve, thus compromised the future; the colossal figure to which these issues mounted have necessarily given birth in our mind to this question of palpitating interest, In what case can the recognizances issued be considered sincere? In what case are they not sincere? In other terms, when is it that the amounts subscribed have been really paid? When is it that we are found in the presence of fictitious values represented by notes of complaisance?

[p. 7] Revolutions are possible only on the condition that their authors find interested persons to finance these criminal enterprises. Unhappily with us the hard and honest work was always the exception, the revolutionary politics the rule, the great industry which attracted to it and monopolized all - energy, intelligence, and capacity. Therefore, there came a moment when the sole preoccupation for each energy unemployed, each intelligence searching its way, each capacity desirous of exerting itself; it was to clothe himself in revolutionary livery in which a campaign was instituted to gain access to the public treasury.

Testimony taken by the committee shows how the chronic anarchy into which Haiti had fallen, the exhaustion of its credit, the threatened intervention of the German government and the actual landing of the French naval forces, all imperiled the Monroe Doctrine and lead the Government of the United States to take the successive steps set forth in the testimony, to establish order in Haiti to help to institute a government as nearly representative as might be, and to assure the collaboration of the Governments of the United States and Haiti for the future maintenance of peace and the development of the Haitian people.

Your committee believes that doubtless the American representatives might have done better and that they have made mistakes, which in light of experience they would not make again; that as will presently be indicated in more detail, not only did the treaty fail to take cognizance of certain reforms essential to Haitian progress, but that in the choice of its agents and the determination of their responsibilities, the Government of the United States was not always happy.

The Occupation and the Treaty.

The history of the landing of American naval forces in Haiti and of the intervention of the United States to establish a government as representative, stable, and effective as possible, is set forth at length in the public hearings of the committee. The naval forces of the United States landed in July, 1915, when the country and more particularly the capital, after the murder of President Sam, had fallen into a condition of anarchy. The diplomatic representatives and naval forces of the United States made it possible for the Haitian Assembly to sit in security. The American representatives in the opinion of your committee influenced the majority of the Assembly in the choice of a president. Later, they exercised pressure to induce the ratification by Haiti of the convention in September, 1915, precisely as the United States had exercised pressure to induce the incorporation of the Platt Amendment in the Cuban Constitution, thus to assure the tranquillity and prosperity of Cuba. At about the same time representatives of the United States Navy took over temporarily the administration of the Haitian customhouses, which were then answerable to no central control, of which the revenues were disposed of at the discretion of the various local customs officers.

The convention of 1915 provides that a receiver general of customs, a financial advisor, and directors of public works and sanitation shall be nominated by the President of the United States and appointed by the President of the Republic of Haiti. It provides, furthermore, for the organization and discipline of an adequate force of constabulary or gendarmerie under the direction of officers nominated by the President of the United States, but commissioned in the [p. 8] service of the Haitian Government by the President of the Republic of Haiti.

Your committee has sought carefully to measure the benefits accruing to the Haitian people as the result of the convention, and to determine wherein the American Government or its representatives had failed in their duty and to advise as to the correction of mistakes or abuses in order that the maintenance of American forces in Haiti may be terminated as soon as possible.

Peace, sure and undisturbed peace, has been established throughout Haiti for the first time in generations. In former years men who were peasants - countrymen - were never seen upon the trails or in the market towns. They feared to appear lest they be pressed into the wretched and underpaid forces of the Republic or of revolutionary pretenders. Women only were found, driving pack animals or carrying burdens on the trails, and chaffering in the market places. The men were hidden in the hills. To-day, as old travelers will bear witness, for the first time in generations the men have come down freely from their hidden huts to the trails and to the towns.

Conformably with the terms of the treaty, the Haitian customs have been administered by the American receiver efficiently and honestly, whereas in the past, by common confession, the administration of them was characterized by waste, discrimination, if not by peculation. The Minister of Finance has acceded to the disbursement of revenues under American supervision. Finally, although the Haitian Government has declined to employ American experts in the administration of internal revenues, nevertheless, under the insistence of the financial advisor and despite general business depression, the sum of internal revenue collected has increased threefold, although the internal revenue laws are unchanged.

There has been very little criticism of the collection of customs under American supervision or of the American receiver general. The financial advisor has been the object of bitter attack, partly because of his personal relations with Haitian officials, partly because under instruction of the Secretary of State he withheld salaries of the principal Haitian officials as a measure of coercion and partly because he has been more than once, and for long periods, in Washington, absent from his post of duty in Port au Prince. In justice to the financial advisor, it must be said that he was ordered to Washington by the State Department and has remained in Washington by order of the State Department to further the negotiation of the loan for the refunding of the Haitian debt.

It has been stated the Haitian Government had never defaulted on the service of its foreign debts prior to the American occupation. This statement is not exactly correct, but it is undoubtedly true that it had exerted itself to an extraordinary degree to maintain the service of its foreign debts. Your committee is informed that to do this the Haitian Government had, during the three years immediately preceding the occupation, floated internal loans at the rates of 59, 56, and 47, to a gold value of $2,868,131, had defaulted on salaries, pensions, etc., to the extent of $1,111,280, had borrowed from the [p. 9] Bank of Haiti $1,733,000, had issued fiat paper money, and had borrowed to a very large amount from private individuals at enormous discounts on treasury notes. The Haitian Government had, at the time of the American intervention, totally exhausted its credit both at home and abroad. The amortization of the loan of 1875 was in arrears. A great deal has been made of the fact that after the naval forces took over the administration of the customhouses and after the outbreak of the Great War, there was a time when, despite careful administration, both interest and amortization due on the Haitian debt were unpaid. This is true, but the inability of the Haitian Government and its American advisers to pay was due to the state of anarchy into which the country had fallen and to the inestimable injury to Haitian trade with Europe consequent upon the outbreak of the Great War. During the last three years, $5,000,000 of interest and principal have been paid. To-day there is no interest or capital overdue. The foreign debt has been reduced by one third. On the contrary, there is a surplus in the treasury and it is proposed to refund the outstanding debt to the great benefit of the Haitian taxpayer.

The Republic of Haiti owes, largely in France, some $14,000,000, part of which could have been paid when the franc was at a discount of 17 to the dollar and which can now be paid while exchange stands at about 10 francs to the dollar. The Haitian Government has lost something over a million dollars by delaying the refunding of the debt. It is still to the patent advantage of the Haitian Government to refund the debt by borrowing in dollars and paying in francs, when the francs are worth not 5 for a dollar, as formerly, but 10 for a dollar. Apart from this, the opinion of your committee, it is of primary importance that the proposed loan should be made without delay, partly because it will afford a sum of money necessary to finish certain public works including the highway to Jacmel and that from Las Cahobas to Hinche, but also because under the proposed terms of the loan, the debt will be a general charge upon the revenues of the country and those revenues which are now specifically and irrevocably hypothecated to the service of certain loans will be freed from such rigid hypothecation and the onerous and inequitable revenue system of the country can be revised. There is appended to this report a table showing the contractual charges upon revenues in Haiti. A student of the Haitian financial system will be struck first by the charges upon exports (indirect and direct) and especially by the fact that they bear very heavily upon the poorest element of the population. If the debt be refunded as proposed, the revenue system can be revised and at one and the same time the burden upon the poor can be lightened an the export trade can be freed of uneconomic taxes.

It may be added that the new refunding loan, if consummated, will be made upon better terms than those recently made in the American marked by European and South American governments.

As the negotiations for the revision of the charter of the national bank are all but consummated, the committee thinks it unnecessary to dwell upon the matter further than to say that due to the insistence of the American State Department and of the vigilant financial advisor, the terms of the new charter are more advantageous to Haiti than those of the old and that already an end has been put to the fluc- [p. 10] tuation of the currency, in which foreign merchants and exporters speculated to their own advantage and to the injury of the Haitian peasant. It is because of this last that certain foreign financial interests, that is, interests neither American nor Haitian, have covertly, persistently, and perhaps corruptly, opposed the determination of the new bank charter and the stabilization of the currency.

As was indicated earlier in the report, when the American naval forces were landed in Haiti in 1915 the fine highway system left by the French had disappeared. In 1917 the commander of the occupation, in collaboration with the Haitian Government, invoked the Haitian law requiring the inhabitants to work upon the highways. This was the forced labor or corvee upon the roads. The law requiring the inhabitants to maintain roads was in principle not unlike some of the highway statutes of our own States. It had not been enforced for decades when, at the instance of the American naval command in Haiti, the Haitian Government invoked it in July, 1916. At first this step appears to have met with no opposition from the natives. On the contrary, under the tactful management of the gendarmerie command at this time, encouraged and stimulated by the enthusiasm of the American officers, they were eager to open a highway from the north to the south of the country. It is the almost unbelievable truth that with the decay of the French roads it was impossible for a vehicle to traverse any section of the roadless republic. People worked with great good will upon those sections of the highway near which they dwelt. It was only after a year or more, when the gendarmerie command unwisely compelled natives to leave the neighborhoods in which they lived in order to complete the roads through the mountains, that discontent and dissatisfaction were first manifest. It is impossible to say in what measure the corvee contributed to the armed outbreak in the north. Almost all Haitian revolutions have had their beginning in the broken country lying between Cape Haitien and the Dominican border. Here the Cacos had lived for generations, and hence they marched to make their periodical attacks upon the capital as followers of one or another revolutionary chieftain. At all events, when the road law had been invoked for nearly two years, and when its enforcement had given rise to discontent, for the reasons indicated, Charlemagne Peralte, an escaped prisoner, raised a band of Cacos in the north, which for some 15 or 18 months carried on a formidable guerilla war against the native gendarmerie and the American Marine Corps.

The accusations of cruelty which have been made against members of the Marine Corps have deeply concerned your committee and required its full consideration. If cruelty toward the inhabitants has been countenanced or has escaped the punishment which vigilance could impose, or on the other hand, if false or groundless accusations have been made, if facts have been distorted, the true conditions should be revealed. Your committee has realized the gravity of the charges and the importance of impartial investigation and it has allotted a full portion of its time to the investigation of these [p. 11] complaints made by or on behalf of the Haitians. Examination has been made of the records and methods of investigations conducted by the Navy Department. Many witnesses have been heard in this country and in Haiti, and some scores of affidavits read and considered. So far as time permitted no one was refused a hearing and no limit has so far been placed on the number of written complaints in affidavit form.

Much evidence does not appear in the record. This consists of oral statements made to the committee or to one or more members in the course of confidential conversations which took place during the committee's visit to Haiti. If those individuals who made the statements had not received and relied on the assurance that their names would not be published, nothing could have been learned from these valuable sources. Among those thus speaking in confidence were Haitians of education and influence, Haitians in positions of great importance, and as well as others in subordinate positions, and Haitian peasants, Americans engaged in business enterprise and other foreigners engaged in business or in philanthropic or educational work. If it had become known that any of these individuals expressed to the committee views contrary to the then organized opposition to the American occupation, and its continuance, that individual would at once be marked for punishment. The consequences to the individual during the continuance of the occupation might have been financially and socially hurtful and if the occupation were to be withdrawn that person who had said anything in its favor would be in danger of persecution or loss of his life. These people who talked to the committee or its members did not know for how long they would receive the protection of the occupation. Those whose views they opposed included an influential group who would, temporarily at least, dominate the country if the occupation were to be withdrawn in the near future.

The committee has weighed this undisclosed evidence and has tried to give it its correct weight, but the committee can not in justice to the individuals disclose their names. One of those who spoke most impressively and whose opinion was entitled to great weight on account of long residence and close sympathy with the Haitians said:

If the Government of the United States was to order the marines to quit the island, the last of them would scarcely be out of sight of land until a shot would be fired and then a revolution.

This opinion differently expressed is widely shared by responsible people in Haiti. Such can not express their opinions publicly at the present time, but no correct estimate of the situation can be reached without their opinions. The report of Professor Kelsey to the American Academy of Political Science, published in the committee's record shows that he had an experience similar to that of the committee. We commend Professor Kelsey's report to the close study of those who are interested in the Haitian problem.

During the five and one-half years of occupation, 8,000 individuals have served in an average force of 2,000 marines maintained in Haiti since the occupation. It is true that some few of these individuals have committed crimes affecting the Haitians, the offenses depending in no way on the military character of the guilty [p. 12] parties. The very small number of such individual crimes reflects credit on the discipline of the Marine Corps. Proper diligence has been exercised by our military authorities in prosecuting and punishing the criminals. There has, however, been a different class of accusations - charges of violence committed by American marines or by the gendarmerie (the Haitian police force organized under the direction of the Marine Corps) and these charges contain elements of military oppression or unnecessary severity and reckless cruelty. These have formed one of the principal fields for investigation by your committee.

With few exceptions there are no complaints of such military abuses in the years 1915, 1916, 1917, and the earlier part of 1918. Nor are there many such complains for the latter part of 1919 or the early part of 1920. All the charges concern times and places coincident with the phase of organized banditry or "Caco" outbreak which became serious in 1918 and was practically suppressed by the end of 1919. The charges of military abuses are generally limited to a somewhat restricted region in the interior of Haiti, namely, the central plain of St. Michel, in which are the communes of Maissade and Hinche, the mountains surrounding this plain, and the mountainous region surrounding the town of Mirebalais. This country is broken and wooded, thinly settled, and very difficult of access. Both areas are cut up by tangled ravines and barricaded by a confusion of small mountain ranges. Torrential streams add to the difficulties of travel. For years this has been habitually a revolutionary area and has been subjected for a generation to frequent destructive operations of irregular revolutionary forces or bandits. The male inhabitants of the region, if not in active sympathy with any of these revolutionary forces, were frequently forced to join them through fear. Peaceful agriculture was next to impossible, and the result was that a great majority of the inhabitants was lawless and in sympathy with the "Cacos," as the revolutionary bandits were called. The recruiting ground for revolutionary expeditions had always been the central plain and the mountains to the north, along the Dominican border.

The causes of the outbreak of lawlessness above referred to are not altogether clear. The principal instigator was one Charlemagne Peralte. He had been a leader or chief of the Cacos in the mountains of the north. He was a man of local prominence and had held absolute sway over his followers. His career had been "revolutionary," but he caused no trouble during the quiet years after the occupation until in the autumn of 1917, when he and some of his followers took part in an armed attempt at Hinche to rob the house of Captain Doxey of some public funds which had been received for disbursement. Charlemagne was arrested and convicted by a provost court and sentenced to a term of imprisonment. He was made to labor in the streets of Cape Haitien under a guard like any other convict, and this aroused his intense bitterness against the Americans. He escaped in 1918 and began the outbreak in July, 1918, with a few of his old followers. His resentment was demonstrated by acts of [p. 13] violence alike against natives and Americans. He rapidly recruited followers from the former professional and habitual revolutionists, and other chiefs, following his example, came from retirement and recruited bands of their own. The outbreak was a much one of organized banditry as it was revolutionary, although there remained much resentment against the Americans among the former revolutionaries. There was resentment also against the continuance of the corvee, and this resentment undoubtedly made recruitment more easy for the bandit leaders. As in former days, also, the leaders pressed other inhabitants into their service.

The guerrilla outbreak was opposed first of all by the gendarmerie, which was recruited principally from the same class of population as the bandits and officered by the United States marines holding commissions in the gendarmerie but by March, 1919, it became clear that the gendarmerie could not suppress the outlawry without assistance, and thereupon the Marine Corps took over the greater part of the burden, although the gendarmerie remained in active service. The enemy knew their country perfectly. When arms were not in their hands they could not be distinguished at sight from other inhabitants. The transformation from peasant to bandit and vice versa could be made at an instant's warning. There was reason to suspect almost any male adult of being from time to time engaged in active lawlessness and habituated to guerrilla warfare.

The problem was to restore peace and order in this central and northern mountainous region. The situation did not admit of effective operations carried on by larger bodies than a platoon or two. The only practicable method was the one adopted - that of constant patrolling by parties ranging in number from 4 or 5 men to 30 or 40 men. These small patrols were almost always vastly outnumbered. They endured tremendous physical hardships. They were frequently beyond the reach of help and were even out of all communication with other friendly forces for two or three weeks at a time. They ran risks and faced dangers such as are endured by beleaguered garrisons. It is impossible to judge of the accusations which have been made or of the conduct of the marines or gendarmerie as if they had been engaged on police patrols in a settled country intersected by highways.

Each patrol was necessarily commanded by an American. At that time if a patrol of gendarmerie were intrusted to a Haitian sergeant, it was not effective against the bandits, and in a default of disciplined command it might constitute a menace to the inhabitants. There were not enough commissioned officers of the Marine Corps available to supply commanders of all these patrols. Many of them were commanded by sergeants, corporals, or even privates of the Marine Corps who were commissioned as captains or lieutenants in the gendarmerie. To the credit of our country nearly all of these men performed their duties admirably. Their courage sustained them in the face of danger and hardship, and their common sense and justice slowly won the confidence of the inhabitants. There were, however, some few exceptions who failed their duty. Among these few were commissioned as well as noncommissioned officers of the Marine Corps. It is against these patrol commanders that the charges of military abuses are made.

The uprising was subdued by these patrols. With greater endurance and determination than the bandits they kept constantly on the [p. 14] move. For months there were skirmishes and marches, and the bandits were kept constantly on the run. Many of the bandits took advantage of invitations to surrender. Those who did so were disarmed and were given a safe-conduct card; but some persisted. As long as a single hostile band was in the field the work remained unfinished. The leaders of the bandits knew and sometimes even were on friendly terms with the "notables" or leading men of these remote sections. As the campaign progressed the marines won the approval of the humble inhabitants, but they increased the dislike and resentment of those notables who were Cacos or were allied with them. The committee has found that most of the accusations are made against the bandits. Some of these were most active and effective against a small handful of marines. Some of the accusations first brought against them have been entirely disproved, and yet other accusations spring up against them. In such cases it is at least possible that they are the victims of slander inspired by the intelligent hatred of the small native leaders whose dominance they destroyed.

The campaign continued through the year 1919. The enemy bands frequently numbered as many as three or four hundred, although their personnel undoubtedly was constantly changing. By constant pursuit and by attacking on sight regardless of the disparity of numbers, the Americans or the gendarmerie, under the American command, gradually wore these bands down until they disappeared. The pursuit and the fighting occurred in the wilderness and it is hard to imagine and impossible to describe the hardships constantly endured by our men. The pursuit under the conditions we have described must have seemed endless, although surrenders and casualties and fatigue were constantly reducing the numbers of the Cacos. It is impossible to give the exact number of engagements, but it is accurate to say that in one place or another armed encounters occurred daily. Late in 1919 Charlemagne was killed in the field. This broke the back of the uprising, but another principal leader, Benoit, remained in bush for several months until he also was killed, in May, 1920. After his death the last of the disorder was quickly put down.

During all these times at least three-fourths of the territory of Haiti and four-fifths of the inhabitants were not directly affected. The remaining one-fourth of the territory to which this discussion refers, containing the lawless population, was the theater of practically all military operations, and was the only source of complaints of military abuses.

These regions are now peaceful. There are no bandits in Haiti. The inhabitants are leaving the mountain forests to cultivate the central plain - less disturbed than they have been within the memory of living man. It is impossible to determine in exact figures the number of Haitians killed in this 18 months' guerrilla campaign. But a fair estimate is about 1,500. The figure includes many reports based on guesses made during combat and not on actual count. The casualties, whatever they were, undoubtedly included some noncombatants. The bandits were found resting in settlements where [p. 15] they were surrounded by their women and children, or in villages where they camped and were tolerated by the inhabitants through fear or friendship. When encountered they had to be instantly attacked. These conditions largely account for the deaths of the bystanders.

Such casualties are to be deplored. They were unhappy consequences of the irregular operations. Your committee is convinced that the suppression of the bandits by patrols was the only method which would have been effective. It is fair to speculate that if the bandits had been permitted to continue their depredations, there would have been a greater number of innocent people killed and a far greater sum total of misery. During this outbreak the bandits preyed on the other inhabitants, robbed them, maltreated them, and burned their houses and crops, as they had been wont to do in the many revolutions before the occupation. The peasants who were the victims do not now wish for the withdrawal of the marines. To-day they may work and travel without fear of robbery. Of this the committee has been convinced by opinions expressed at first hand by intelligent peasants. These are jealous of their sovereignty but have every reason to be and are aware of the benefits of peace and order, and their first wish is that peace and order by some means may be assured.

The committee is convinced that cruelty has never been countenanced by the Navy Department or by the brigade commanders of our marines in Haiti, or the commandants of the gendarmerie of Haiti, nor has this been alleged to the committee.

It is evident to anyone who reads the testimony of a number of witnesses that some false and groundless charges have been made, and that in many cases facts have been distorted and exaggerated. Fairness compels the further explanation that few, if any of the illiterate and ignorant peasants making such charges knew the difference between what they had seen what they had heard said at second or third hand or on sheer rumor. Utterly untaught in justice or evidence, they have probably been induced in some cases to bear false witness. Whether these charges be described as false or mistaken, it would be wrong to judge those who made them by American standards. Nevertheless, the testimony of such witnesses is dangerous unless it is carefully sifted. An illustration will show this:

In September, 1920, five Haitian gendarmes stated under oath that Lieut. Freeman Lang, of the gendarmerie, had in the early part of November, 1918, at Hinche shot a prisoner. One other said he saw Lang shoot two prisoners. One other said he had seen Lang shoot five prisoners at different times in October and November, 1918. All, however, told of the death of one particular prisoner. They all said the single prisoner had been led from jail and that he had talked with Lang and had then been killed by Lang at a distance of 10 to 20 paces with a machine gun or automatic rifle. Two added that Lang told the man he was released and could go home. Some said the man refused to give information and was therefore shot. According to the testimony of each of these witnesses, it was a cold-blooded and treacherous killing. All said they had seen it done.

[p. 16] In November, 1920, five of these same witnesses also testified before the Mayo court of inquiry. On the latter occasion the witness who had said Lang killed two prisoners testified that only one man was killed and that he was walking away. Another witness at the later hearing said that the prisoner was walking, then that he was running and trying to escape. His first version had been that Lang had told the prisoner he could go home. Another of these witnesses, the one who said he had seen Lang take five from prison and shoot them because they would not talk, could not at the second hearing say whether the prisoners were running or not when they were shot, and that in two of the cases he did not see the shot fired. He also gave a different place for one of the shootings in his later testimony. There were no prisoners missing from the prison at Hinche at those times. In their later testimony two witnesses made the date precise, November 4, but one could not tell the year. One who first testified he saw Lang shoot the prisoner, later said he did not see Lang shoot the prisoner, only saw the prisoners dead after hearing the shots. Another first testified that Lang told the prisoner he could go home, and said two months later that he was a long way off and could hear nothing that was said. Lang's version, fully substantiated by Daggette, another marine eye witness, was that the prisoner, a Caco leader just captured, was taken under guard from prison to Lang's house to be questioned. He refused to talk and was led back under guard toward the jail. Lang at the same time had walked a considerable way toward his office in another building when he heard the guard fire two or three shots and saw the prisoner running toward some woods across the square. The guard was missing his shots and it was dusk.

Lang ran back 30 or 40 yards to his house where there was an automatic rifle kept set up on the veranda loaded and cocked. He fired in order to prevent his escape; one shot burst and brought the running man down dead at a distance of 150 yards. He at once reported the incident to his superior officer. A circumstance which discredits the Haitian witnesses is that an automatic rifle is too heavy a weapon to hold comfortably while standing up to cross question a witness or to have overlooked while assuring a prisoner he could walk away with safety. At any rate the Mayo court exonerated Lang completely of this charge and likewise exonerated him on other charges brought against him by the same kind of witnesses, charges that circumstances and positive testimony proved impossible. These charges were probably inspired.

A reading of the testimony referred to in the Mayo court record will certainly raise that suspicion. (See Exhibit 5 attached to record of Mayo court and testimony before that court of Toussaint, Monfiston, Brave, Jean, Rouchon, Lang, and Daggett.)

The committee itself has heard Haitian witnesses declare they had seen certain acts and describe them in detail, and then after some questioning - entirely kindly - say they had been one-half mile or more away or in another part of the country and had only heard about it soon afterwards or much later.

A witness named Polidor St. Pierre testified before the committee at Port au Prince that he had been tortured in the prison St. Marc in January, 1919, and that the American marine captain whom he named had been personally present and directed the tortures. The [p. 17] witness said that the captain had caused him to be put in irons and hung up by a rope attached to his handcuffs and passed over a rafter in a prison cell. He said he thus passed five days without eating or drinking. The witness next testified that the next morning after the witness entered the prison the captain caused water to be boiled and poured down the witness's throat. The actual operation was performed by four gendarmeries, the captain being present.

The witness said that two days afterwards the captain himself applied a hot iron to various parts of the witness's body, and that later he received medical treatment from the captain and a surgeon. The witness said that another Haitian prisoner named Medelus Valet was present and saw these occurrences, and that this same Valet was at the time of the committee's hearing imprisoned at Port au Prince. The committee caused Medelus Valet to be brought before it and sworn. Before this time neither the committee nor its counsel had opportunity to communicate in any way with Valet, and had no intimation as to what his testimony would be. Valet said that St. Pierre was tortured, that he had been hung up on three different occasions about one-half hour each by a rope attached to his handcuff, that he had not had water poured down his throat but that he had been branded. Valet said that this was all done by Haitian detectives and gendarmes in the absence of the captain, and that the captain became very angry when he learned of the mistreatment. He took St. Pierre out of the cell, put him in the prison sergeant's room and had a surgeon treat him three times a day. (Reference: Testimony of St. Pierre, record, pp. 857 - 865; testimony of Valet record, pp. 883 - 885.) These illustrations are not exceptional but usual, both in untruthfulness of testimony and in the suspicion of subornation.

On the other hand, certain instances of unauthorized executions of captives at the hands of marines or at their command are beyond much doubt established. The number is small. In fact, after full inquiry and earnest invitation to complainants to come forward as witnesses or with affidavits, the committee is to this day reasonably satisfied of the fact of 10 such cases, of which 2 have been established in the course of judicial inquiries. Those who were killed had been caught bearing arms and had been imprisoned. These illegal killings all took place within the period of six months from December, 1918, to May, 1919, and all happened in one of the two areas in the remote interior. Of the three Americans who, as officers, would be directly responsible, if the facts were judicially established, one (1) was insane, one (2) is dead, and the other (3), commissioned in the gendarmerie from the enlisted personnel of the marines, has been discharged from the service. These three cases call for special mention:

(1) The evidence as to this case is found in the court-martial records of Privates Johnson and McQuilkin and on pages 737 to 741 of the committee's record. The American gendarme lieutenant in question was a private in the Marine Corps, commissioned as lieutenant in the gendarmerie. The two privates, Johnson and McQuilkin, were court-martialed because they were members of a firing squad which illegally executed two Caco prisoners in May, 1919, at Croix des Bouquets in the region [p. 18] of Mirebelais. The evidence is clear that these executions were ordered and superintended by the American lieutenant of gendarmerie. In the testimony it also appeared as undisputed that these same men had been present at the execution of still one more Haitian prisoner five days earlier, also under the orders of the same lieutenant. There is no doubt but that those who were executed had already been taken prisoners and were shot without trial. The lieutenant who directed the executions was not court-martialed because he was found to be insane. His mental condition was observed at Port au Prince in July 1919, at the Naval Hospital, Charleston, S.C., in September 1919, and the Naval Hospital, Washington, D.C., in October, 1919, and in all cases the diagnosis was dementia precox.

The court-martials of the two privates were upon charges preferred June 22, 1919, one month after the executions of the Haitian prisoners. It was these two court-martial cases which upon being reviewed by General Barnett, as commandant of the Marine Corps, caused him to write a letter to Colonel Russell, then brigade commander, in which the general uses the expression "practically indiscriminate killings" by marines of natives. General Barnett testified before the committee (record p. 439) that these two court-martial cases formed the only basis for his allegation. While there can be no excuse for the killing of these three Haitians there could have been no legal conviction of the lieutenant of gendarmerie, who was insane.

(2) Reference in this instance is made to the testimony of Mr. Spear, formerly a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, which appears in the committee's record, pages 583 to 592, and also to the record, pages 646 to 647. Mr. Spear, now an attorney practicing in Nebraska, had enlisted in the Marine Corps and been promoted to a lieutenancy. While holding this rank he saw service in Haiti. In May, 1919, he was second in command of a detachment of Marines near Mirebelais. This detachment was relieved by another, the commander of which turned over two Haitian prisoners to the commander of Spear's detachment. The commander of Spear's detachment understood that these prisoners were turned over to him with orders to kill one of them.

One of them was shot by the orders of the commander of Spear's detachment. There were no Haitian prisoners at that time under sentence of death, and this alleged execution would therefore necessarily be illegal. The detachment commander who directed this execution was killed in an airplane accident in August 1920. The committee finds no reason to doubt the truth of Mr. Spear's testimony, and although the death of this unknown Haitian can not be regarded as legally established the occurrence can not here go unmentioned. It apparently did not become known to officers in higher command. There is nothing to show that Lieutenant Spear was in any way responsible for the death of this Haitian. There can be no justification for the execution of the prisoner if in fact it took place.

(3) In this case the American in question was, as captain in the gendarmerie, in direct military control of a relatively small territorial subdivision. The locality was, however, one of importance, because it was a trouble center for bandits. From time to time prisoners were taken in armed encounters or arrested as bandits. This man admitted to the brigade commander, Brigadier General Catlin, and to the commandant of the gendarmerie that he had caused the execution without trial of six prisoners led from jail.

[p. 19] The question of a court-martial on a charge of murder was resolved in favor of the offender by the brigade commander because the proof of guilt consisted of the confession, and the confession required corroboration. Such was the quality of the other evidence available that the brigade commander doubted whether it would be sufficient in law. He testified before the committee that an acquittal would have had a bad effect on the natives, who would have called the trial a whitewash, while a conviction in a place far away could never have any effect one way or the other with the inhabitants. He decided not to risk an acquittal, and without court-martial removed the man from command and service in the gendarmerie. The man, soon afterwards discharged from the Marine Corps, has disappeared. If apprehended he might be surrendered to Haiti at the request of that Government, but the legality of such surrender would be at least doubtful. Whether at this late date a conviction for murder on testimony of the ignorant and irresponsible native witness from the locality would be possible or just the committee as a nonjudicial body can not decide. It feels, however, that there might be a reasonable doubt. In the judgment of the committee there must have been some tangible ground for trial and punishment if not for murder, at least for a lesser offense against discipline. The committee is astonished that a man without sufficient experience or established character should have been placed in authority in a troubled district. (See General Catlin's testimony, record, pp. 660-662. General Catlin's statement, Exhibit 5, Mayo court record, Lieut. Col. A. S. Williams's testimony, record, pp. 549 - 550.)

The committee has heard a number of complaints of the burning of houses of innocent inhabitants by the marines. The witnesses or affiants do no allege nor do they deny that there were cacos or bandits actually there at the time of the burning. The times and places allege in all cases seem, however, to indicate that the houses burned were palm or wattle huts in settlements infested by bandits. The bandits were either there or near by in camps or were resting in the guise of innocent inhabitants, and the huts were burned by patrols. In some cases this was undoubtedly a necessary military measure. It is also quite possible that some habitations were burned without substantial justification on this ground, but the committee has not learned of any that were burned at places and times where and when there were not grounds to suspect that they were used as shelter for the enemy.

Accusations have been made of tortures and cruel beatings. Many of these accusations have been completely refuted; others bear a resemblance to types of cruelty well known in Haiti for many years but foreign to anything known in America. Americans are not given to mutilating their dead enemies. A charge of mutilation against an American at once suggests a very close scrutiny of everything the witness says. Mutilations probably did occur. They may have been inflicted by the bandits or by the gendarmerie in the absence of white officers or conceivably by white officers, but the character of the testimony leaves a grave doubt as to the identity of the criminals. The committee is convinced that these cruel or inhuman acts were probably never committed by Americans.

[p. 20] Maj. Clarke H. Wells, of the United States Marine Corps, was a colonel in the gendarmerie and in command of the Northern Department of Haiti in the last months of 1918 and until March 1919, when he was relieved by the then brigade commander, Brigadier General Catlin. The manner in which he performed his duty and the subsequent investigations of his conduct call for special comment by the committee. Conditions had gotten out of hand in his department, which embraced the trouble centers of Hinche and Maissade, and General Catlin, reaching that conclusion, relieved him. There had been a mutiny in a gendarmerie station. Specific accusations were made against Major Wells, and these accusations were examined in four later investigations. Court-martial charges of a serious nature were preferred against this officer and withdrawn without trial on account of insufficiency of evidence to substantiate the charges. He was in a position of high responsibility, and the consequences of any failure in duty or misconduct on his part would therefore have been great. The committee finds every evidence of sincere and energetic investigation of the charges against Major Wells, but it regrets that investigation was not instituted more promptly or rather at the time when he was relieved from command of the Northern Department. A board of investigation took up his case about six months after he was relieved from command. It is apparent that even then too much time had elapsed to arrive at the facts. The character of the testimony adverse to Major Wells does, in the opinion of the committee, raise such a doubt as to fault on his part as would make unjust any findings against him.

At the same time the present situation is unjust to the officer in question if he is blameless. Therefore, the failure to go thoroughly into his conduct in March, 1919, is greatly to be regretted. The truth arrived at then would undoubtedly have cleared up incidentally many of the other accusations with which the committee has had to deal because the greater part of the accusations arose in Major Wells's department during the time of his incumbency.

The specific accusations were:

(1) That he permitted a continuance of a modified form of corvee after all corvee had been prohibited. Actual knowledge of this on the part of Major Wells could not be proved, but at Hinche and Maissode there continued some work on the road which while not technically forced labor was being done at low wages by unwilling workmen. This caused serious trouble.

(2) That Major Wells directed the suppression of mention of trouble in reports to gendarmerie headquarters. Major Wells has denied this but has stated that he did make an effort to suppress sensationalism in reports. The testimony is conflicting.

(3) That he gave directions to treat the Cacos with severity and that he discouraged the taking of prisoners. Some forms of this accusation are to the effect that he directed that prisoners be killed and that his was understood to authorize the execution of prisoners already captured rather than the shooting at sight of armed bandits.

The testimony subsequently taken on all these points is contradictory and confusing especially on the last point. Three gendarmerie officers were examined at least twice and the statements of each were very dissimilar on the different occasions. A number of officers with equal opportunities for observation were examined and [p. 21] their testimony was entirely negative. The testimony which was most damaging, if competent, was purely hearsay and on being followed up was not substantiated. There are indications that the testimony of some of the officers examined after they had left the service was biased by prejudice. Other officers examined spoke very highly of Major Wells's administration.

The record as a whole discloses an earnest effort in September 1919, by Major Turner, and in January, 1920, by Colonel Hooker and Major Turner, by the direction of the brigade commander, Colonel Russell, and in September, 1920, by Generals Lejeune and Butler by the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, and in October and thereafter in 1920 by the Mayo court of inquiry to arrive at the facts. This committee wishes to express its regret that doubt still remains and its belief that more prompt investigation should have been made.

The committee is not a judicial body. It feels that it should make no report definitely accusing any individual of crime unless that individual has had a trial. The committee can not try individuals nor can the committee continue indefinitely in existence. Since its visit to Haiti the committee has received a number of affidavits definitely accusing American officers of murder and extreme cruelty, mostly during the year 1919. The number of officers named is not large. During its visit to Haiti it heard testimony in which officers were accused and in which military abuses were attributed to unnamed American marines. Investigation of some of these cases has already been made and the committee has the reports. The committee has referred all other accusations for investigation by the Navy Department, requesting a report as to facts developed. It has admitted in evidence all the accusations. Time has not permitted due investigation of and report on the more recently received accusations. The committee proposes to print all accusations of a serious nature, but it proposes to reserve such publication until the results of investigation can be printed at the same time. In this way it feels it may demonstrate to the Haitians the willingness of America to receive and air all just complaints, but at the same time it will safeguard innocent and faithful American officers from revolting slander.

On the evidence before it the committee can now state -

(1) That the accusations of military abuses are limited in point of time to a few months and in location to restricted area.

(2) Very few of the many Americans who have served in Haiti are thus accused. The others have restored order and tranquillity under arduous conditions of service, and generally won the confidence of the inhabitants of the country with whom they came in touch.

(3) That certain Caco prisoners were executed without trial. Two such cases have been judicially determined. The evidence to which reference has been made shows eight more cases with sufficient clearness to allow them to be regarded without much doubt as having occurred. Lack of communications and the type of operations conducted by small patrols not in direct contact with superior authority in some cases prevented knowledge of such occurrences on the part of higher authority until it was too late for effective [p. 22] investigation. When reported, investigations were held with no apparent desire to shield any guilty party. Such executions were unauthorized and directly contrary to the policy of the brigade commanders.

(4) That tortures of Haitians by Americans has not in any case been established, but that some accusations may have a foundation in excesses committed by hostile natives or members of the gendarmerie without the knowledge of American officers. Mutilations have not been practiced by Americans.

(5) That in the course of the campaign certain inhabitants other than bandits were killed during operations against the outlaws, but that such killings were unavoidable, accidental, and not intentional.

(6) That there was a period of about six months at the beginning of the outbreak when the gendarmerie lost control of the situation and was not itself sufficiently controlled by its higher officers, with the result that subordinate officers in the field were left too much discretion as to methods of patrol and local administration, and that this state of affairs was not investigated promptly enough, but that it was remedied as soon as known to the brigade commander. That the type of operations necessarily required the exercise of much independent discretion by detachment commanders.

(7) That undue severity or reckless treatment of natives was never countenanced by the brigade or gendarmerie commanders and that the investigation by naval authority of charges against members of the Marine Corps display no desire to shield any individual, but on the contrary an intention to get at the facts.

(8) That the testimony of most native witnesses is highly unreliable and must be closely scrutinized and that many unfounded accusations have been made. It is also felt that in the case of accusations of abuses committed two years ago now made for the first time, the delay has not arisen through any well grounded fear of oppression by military authority, but that many of those accusations in affidavit form, now forthcoming, are produced at this late date because it is thought by those who are agitating for the immediate termination of the occupation that such accusations will create in the United States a sentiment in favor of such termination. In such cases the delay in making the charges and in presenting the evidence weighs heavily against the truth of the charge. All such charges, however, require full investigation. The committee feels certain that the necessary investigation by the Navy Department will be thoroughly conducted, that the rights of those accused will be respected, and that there will be no suppression of facts. When collected that facts so obtained may be weighed with the facts alleged in the accusation. If, when all such evidence is in, the committee has any reason to change any of its conclusions it will submit with the evidence as printed such revision of this report on the alleged military abuses as may be required.

The committee believes that an important lesson may be learned from a study of the bandit campaign and the subsequent grave charges of misconduct. The lesson is the extreme importance in a campaign of this kind for higher command to require daily operation reports to be prepared by patrol leaders. In the early days of the outbreak such reports were not systematically required. Small patrols would be out of touch with the rest of our forces for days or [p. 23] weeks under distressing conditions of service. There is no complete record of the places they visited or when the visits were made or who was in command. If such reports or records were in existence, innocent individuals could instantly be cleared of unfounded charges, and guilty individuals could be identified with certainty. Such reports would have been a safeguard to the inhabitants and to the reputation of the Americans.

American Effort to Blacken the Name of the Navy.

In concluding this portion of the report the committee expresses its chagrin at the improper or criminal conduct of some few members of the Marine Corps and at the same time feels it to be its duty to condemn the process by which biased or interested individuals and committees and propagandists have seized on isolated instances, or have adopted as true any rumor however vile or baseless in an effort to bring into general disrepute the whole American naval force in Haiti. The committee wishes to express its admiration for the manner in which our men accomplished their dangerous and delicate task.

Patrolling still goes on, although the country is peaceful. For the last two years or more daily reports have been required. It is noteworthy that in the last two years or more there have arisen no serious grounds for complaint.

The confidence placed in the Americans by the Haitian peasants and the approval frequently communicated to the committee by those who know and sympathize with the peasants and who are engaged in philanthropic or educational work among them negative the idea of any campaign of terrorism against the inhabitants such as agitators and professional propagandists, Haitian and American, would have appear. [original paragraph unclear]

The acceptance of the status quo, the appreciation of the present peace and increasing prosperity of the country, by the mass of the people, is proven by the fact that there are among two and a half million people only twenty-five hundred gendarmes and less than twenty-five hundred marines.

A Summary of Failure and Achievement.

It has been necessary to interrupt the general consideration of the American occupation in Haiti, in order to review at length the incidents of the outbreak of 1918 and 1919. The committee is not prepared to say that the rising of Caco bands in the section of the country, where for a generation revolution habitually originated, was encouraged by the corvee. But it is impossible not to condemn the blunder committed when, under the corvee, laborers were carried beyond their vicinage to work under guard in strange surroundings. This was an error of commission like those of omission arising from failure to develop a definite and constructive policy under the treaty or to centralize in some degree responsibility for the conduct of American officers and officials serving in Haiti under the Government of Haiti or that of the United States. The blunder arose, too, from the failure of the departments in Washington to appreciate the importance of selecting for service in Haiti, whether in civil or military capacities, men who were sympathetic to the Haitians and able to maintain cordial personal and official relations with them.

[p. 24] It may be set down to the credit of the American occupation and the treaty officials that the Haitian cities, once foul and insanitary, are now clean, with well-kept and well-lighted streets. The greater part of an arterial highway system opening up the heart of the country has been built. The currency, which once violently fluctuated under the manipulations of European merchants, has been stabilized, to the great advantage of the Haitian peasant. Arrears of amortization as well as of interest on the public debt have been paid, as also are regularly paid the salaries of the smallest officials. The steamship communications between Haiti and the United States are greatly improved. Trade and revenues are increasing. The revision of the customs and internal taxes, so important to the prosperity of Haiti and especially of its poorest classes, awaits the funding of the debt by a new loan. There is peace and security of property and person throughout the Republic. The peasant in his hovel or on the road to market is safe from molestation by brigand or official authority. A force of 2,500 gendarmes, insufficiently trained to cope with the caco outbreak in 1918, is now admirably disciplined. As its morale has improved, the force has become at once more considerate and more efficient in the discharge of its duties. It is noteworthy that an increasing proportion of the commissioned officers are native Haitians, those promoted from the ranks to be supplemented by others, graduates of the newly established cadet school. In brief, under the treaty, the peace of the Republic, the solvency of its Government, and the security of its people have been established for the first time in many years.