The Navy Department Library

Viet-Nam

The Struggle for Freedom

Questions and Answers

DoD GEN-8

Armed Forces Information and Education

Department of Defense

This pamphlet was prepared as State Department Publication No. 7724. The cover has been changed to adapt it to use by the Armed Forces. Otherwise, this pamphlet is the same as the original.

Introduction

Questions

Questions/Answers

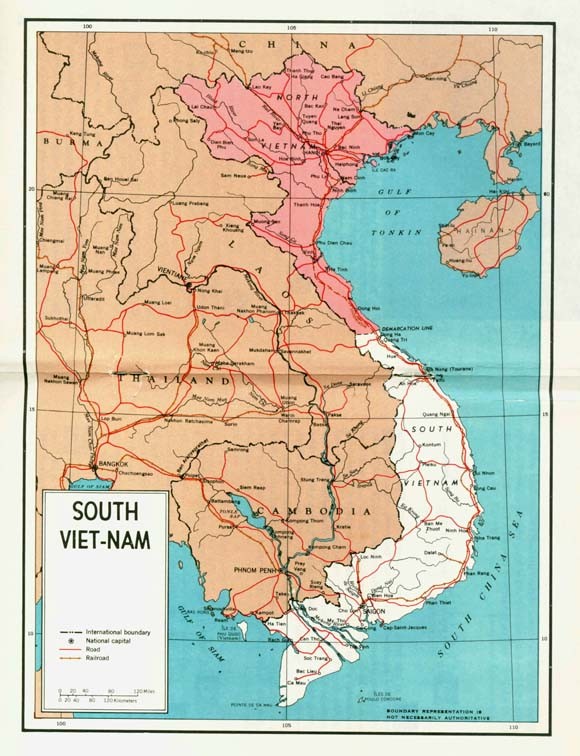

Map of South Viet-Nam

INTRODUCTION

On August 2, 1964, three North Vietnamese PT boats fired torpedoes and shells at the US destroyer Maddox on the high seas in the Gulf of Tonkin. The destroyer and US aircraft promptly fired back and drove off the PT boats.

On August 4 that attack was repeated in the same international waters against two US destroyers. Our Navy’s response was equally prompt and at least two of the attacking boats were sunk. In addition, air units of our 7th Fleet struck at the bases and other facilities in North Viet-Nam which supplied and supported the attacking boats. This latter action, as President Johnson told the nation that same night, was taken because “…repeated acts of violence against the Armed Forces of the United States must be met not only with alert defense but with positive reply.”

The next day the President told the nation and the world:

“Aggression—deliberate, willful, and systematic aggression—has unmasked its face to the entire world. The world remembers—the world must never forget—that aggression unchallenged is aggression unleashed.

We of the United States have not forgotten. That is why we have answered this aggression with action.

America’s course is not precipitate.

America’s course is not without long provocation…

To the south, it [North Viet-Nam] is engaged in aggression against the Republic of Viet-Nam.

To the west, it is engaged in aggression against the Kingdom of Laos.

To the east, it has now struck out on the high seas in an act of aggression against the United States of America…

…The challenge that we face in Southeast Asia today is the same challenge that we have faced with courage and that we have met with strength in Greece and Turkey, in Berlin and Korea, in Lebanon and in Cuba, and to any who may be tempted to support or to widen the present aggression I say this: There is no threat to any peaceful power from the United States of America. But there can be no peace by aggression and no immunity from reply. That is what is meant by the actions we took yesterday.”

On August 7 the Senate and House of Representatives in a joint resolution supported and approved the measures taken by the President to repel armed attack against US forces and to prevent further aggression. The resolution then added:

“The United States regards as vital to its national interest and to world peace the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia. Consonant with the Constitution of the United States and the Charter of the United Nations and in accordance with its obligations under the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, the United States is, therefore, prepared, as the President determines, to take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force, to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance in defense of its freedom.”

Over 200 million people live in the non-Communist countries south of China and east of India, a region rich in culture, land, and resources—the one part of Asia that is relatively under populated. From it come Asia’s most important food exports, 70 percent of the world’s tin and 70 percent of the world’s natural rubber. Lying athwart the crossroads between two oceans and two continents, Southeast Asia is a region of great importance not only to the people who live there but to all the free world.

The Communists of North Viet-Nam and China are eager to take over this fertile area, not by the type of open aggression used in Korea but by attack from within, by covert aggression through guerilla warfare, and by infiltrating trained men and arms across national frontiers. Communist success in Laos and South Viet-Nam would gravely threaten the freedom and independence of the rest of Southeast Asia. It would undermine the neutrality of Cambodia, would make Thailand’s position practically untenable, would increase the already great pressure on Burma, would place India in jeopardy of being outflanked, would enlarge Communist influence and pressures on Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and would impair the free-world defense position in all of Asia. It would confirm the Asian Communist belief that a policy of militancy pays dividends, and could undermine the will of free peoples on other continents to defend themselves.

That is why we stand firm in Southeast Asia today. And that is why we are determined to keep free men free in Southeast Asia tomorrow and in the years ahead.

It is important that Americans know the background of recent events in this part of the world. This pamphlet seeks to provide candid answers to the questions most frequently asked about Viet-Nam, Laos, and Southeast Asia in general.

QUESTIONS

1. What are the origins of our commitment in Viet-Nam?

2. What are the chances of peace in Southeast Asia?

3. What has brought about the present crisis in Viet-Nam?

4. What is our goal in South Viet-Nam?

5. What is the current status of loyalty to the Government and morale in South Viet-Nam?

6. What is the New Rural Life Hamlet Program, and how does it work?

7. What were the provisions of the 1954 Geneva agreements and how have they worked?

8. How does the Communist campaign in Viet-Nam differ from conventional war?

9. What is the latest and most realistic estimate of the military situation in South Viet-Nam?

10. What is the relative strength of the opposing forces in South Viet-Nam?

11. Why do we think, after the French defeat in Viet-Nam that we have any better chance of success?

12. Isn’t the war in South Viet-Nam a civil war and thus no concern of ours?

13. What is meant by “war of national liberation?”

14. How do you account for the fact that the Communists can instill such a strong will to fight in their followers?

15. Are the Vietnamese good soldiers?

16. It has been said that night operations—essential in a guerilla war—are not being conducted by the Vietnamese forces against the Viet Cong. Is this true?

17. What about charges of brutality against captured Vet Cong by Vietnamese Government troops?

18. What are the casualty figures—killed and injured—in Viet-Nam for Americans and Vietnamese?

19. What is the “South Viet-Nam National Liberation Front?”

20. Why do we say that the US role in Viet-Nam has been to provide advice and equipment, when everyone knows Americans have been fighting and dying in that war for more than 2 years?

21. Why don’t American advisers take direct command of Vietnamese units?

22. Why not send US combat units to fight in South Viet-Nam?

23. If the situation gets worse, will American dependents be removed from Viet-Nam?

24. Is it true that the equipment we have supplied to the Government of Viet-Nam and to our own personnel is inadequate and obsolescent?

25. How does the US AID program complement the military effort?

26. What about charges of waste and inefficiency in US aid to Southeast Asia?

27. Do the US air strikes against North Viet-Nam’s PT boat bases mean we intend to carry the war to North Viet-Nam?

28. Why not carry the war to North Viet-Nam?

29. Why not end the fighting in South Viet-Nam by neutralization through negotiation?

30. How is the military situation in South Viet-Nam related to that in Laos?

31. What were the terms of the 1962 Geneva agreement on Laos?

32. What happened after the 1962 agreement was signed?

33.What are US aims in Laos?

34. What kind of assistance do we provide to Laos?

35. What has brought about the present sense of crisis in Laos?

36. Why not turn the problem over to the United Nations?

QUESTIONS/ANSWERS

Q1. What are the origins of our commitment in Viet-Nam?

A1. The United States has provided economic, technical, and military assistance to Viet-Nam since 1950. After the Geneva accords of 1954 the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) became the only outside source of military aid for the Vietnamese armed forces. This activity was within the frameworks of the accords.

The policy behind our assistance was stated in a letter from President Eisenhower to the President of Viet-Nam on October 1, 1954: “The purpose of this offer is to assist the Government of Viet-Nam in developing and maintaining a strong, viable state, capable of resisting attempted subversion or aggression through military means.”

Our commitment was restated by President Eisenhower in 1959 when he said:

“Unassisted, Viet-Nam cannot at this time produce and support the military formations essential to it or, equally important, the morale—the hope, the confidence, the pride—necessary to meet the dual threat of aggression from without and subversion within its borders.

…Strategically, South Viet-Nam’s capture by the Communists would bring their power several hundred miles into a hitherto free region. The remaining countries in Southeast Asia would be menaced by a great flanking movement…The loss of South Viet-Nam would set in motion a crumbling process that could, as it progressed, have grave consequences for us and for freedom.”

In 1961 President Kennedy paid tribute to the courage of the Vietnamese people and said:

“…the United States is determined to help Viet-Nam preserve its independence, protect its people against Communist assassins, and build a better life through economic growth.”

On June 2, 1964, President Johnson said:

“It may be helpful to outline four basic themes that govern our policy in Southeast Asia.

First, America keeps her word.

Second, the issue is the future of Southeast Asia as a whole.

Third, our purpose is peace.

Fourth, this is not just a jungle war, but a struggle for freedom on every front of human activity.”

President Johnson went on to say:

“…we are bound by solemn commitments to help defend this area against Communist encroachment. We will keep this commitment. In the case of Viet-Nam, our commitment today is just the same as the commitment made by President Eisenhower to President Diem in 1954—a commitment to help these people help themselves.”

Q2. What are the chances of peace in Southeast Asia?

A2. At present they are remote.

The North Vietnamese spearheads of aggression are supported by the Communist regime in Peking, which rules over 700 million people.

Beyond its immediate objective of conquering the South, North Viet-Nam has indicated by its acts and statements that it intends to become master of as much of Southeast Asia as it can. This is clearly evident in Laos, where it supports the Communist Pathet Lao military force with men and equipment.

However, the United States has made it clear that a prescription for peace does exist in Laos and Viet-Nam.

As Secretary Rusk has often said, all that is needed to restore peace in Southeast Asia is for the Communists to live up to the agreements they have already made. All that is needed is for the Communists to stop their aggressions, to go home, to leave their neighbors alone.

Q3. What has brought about the present crisis in Viet-Nam?

A3. Let us review some recent history.

Under the Geneva agreements in 1954 it was hoped that South Viet-Nam would have the opportunity to build a free nation in peace. The country faced staggering problems—to name only one: the 900,000 refugees who, at the time of partition, had fled homes in the North to escape Communist rule.

President Eisenhower directed that the United States provide help—largely economic. With assistance South Viet-Nam began to grow and develop. Tangible signs of progress were evident in rice production, transportation, land reform, rubber output, and industrial development.

This confounded the expectations of the Communists in Hanoi, who had expected South Viet-Nam to collapse and fall under their control. In 1957 they reactivated the subversive network they had left south of the 17th parallel after Geneva and began the attempt to bring about the collapse of the South through selective terrorism and sabotage. In 1959 Hanoi announced its campaign of “national liberation” and embarked on an aggressive program of wholesale violations of the Geneva agreements.

Recently Secretary of State Dean Rusk pointed out that in 1959 “no foreign nation had bases or fighting forces in South Viet-Nam. South Viet-Nam was not a member of any alliance. If it was a threat to North Viet-Nam it was because its economy far outshone the vaunted ‘Communist paradise’ to the north.”

Throughout 1960 and 1961 the situation in South Viet-Nam grew more critical. Over 3,000 civilians, in and out of government, were killed and another 2,500 kidnap[p]ed. Infiltration from North Viet-Nam increased. People in many areas came under Viet Cong control and were forced to provide the insurgents with food and recruits. The Viet Cong were able to mount attacks with larger units, up to battalion size.

It was apparent that the International Control Commission set up by the Geneva agreements could not restore peace and that the only effective course of action would be to help the Vietnamese Government to resist aggression. At their urgent request US military and economic assistance was substantially increased.

The struggle against the Viet Cong was interrupted in 1963 by internal crises arising from disputes between the Government and the Buddhists, as a result of which President Ngo Dihn Diem lost the confidence of his people. There were accusations of maladministration, nepotism, and injustice. Two coups d’etat occurred within 3 months, with inevitable dislocations in administration.

The Viet Cong exploited these disruptions by stepping up the scale of its attacks. There was a wave of killings and terrorist acts. But the government has moved vigorously and swiftly to reconstruct the machinery of government. With our continued assistance it is taking steps to recover the losses that occurred during the period of the coups.

Q4. What is our goal in South Viet-Nam?

A4. In helping the Republic of Viet-Nam to resist the attack mounted against it, the United States has these goals:

• an end to the fighting and terror in South Vietnam;

• preservation of the freedom of the South Vietnamese people to develop according to their own desires, without outside interference and without serving the policy of any other nation;

• establishment of the authority of the Government in Saigon over all the territory south of the 17th parallel.

The Communists charge that the United States seeks to establish a military base in South Viet-Nam. This is false. We have no colonial or territorial aims anywhere in Southeast Asia, nor do we seek any national military advantage such as the establishment of bases. It is the Communists who wish to impose their sterile dictatorships on a free people. Our purpose in Southeast Asia is to frustrate these designs.

Q5. What is the current status of loyalty to the Government and morale in South Viet-Nam?

A5. In some parts of Viet-Nam, especially those controlled by the Communists, loyalty to the Central Government is weak or non-existent and morale is poor. The years of war characterized by Viet Cong terrorist acts aimed at the civilian population have taken their toll. The unpopularity of the Diem government in its final period of rule also adversely affected loyalty and morale.

But elsewhere, where Government forces maintain security and where the economic, social, and administrative programs of the Central Government show results, the reverse is true. In some areas, where the Communists have been strong, peasant attitudes appear to be turning against the Viet Cong as the latter step up heavy taxation, rigid control, and indiscriminate terrorism and are unable to produce on promises made over a period of years.

Overall it is clear that the key to building morale and loyalty to the Government is physical security. As long as the Viet Cong are able to terrorize the civilian population, morale cannot be expected to be good. But it is quite plain that, given adequate protection from Communist reprisals, the South Vietnamese will support their Government.

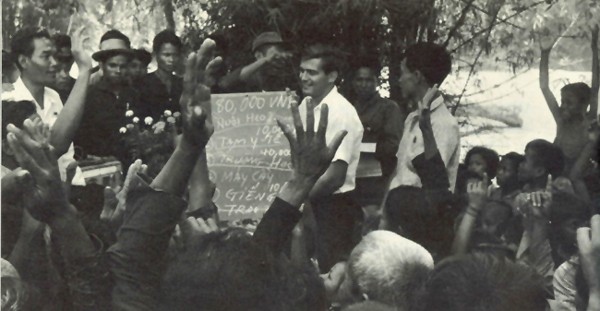

Q6. What is the New Rural Life Hamlet Program, and how does it work?

A6. The New Rural Life Hamlet Program, like its predecessor, the Strategic Hamlet Program, is designed to bring physical safety and security to the countryside and thus to provide the basic conditions in which economic, political, and social progress can take place. No development plans can succeed as long as the Viet Cong are able to terrorize peasants by hit-and-run raids, murder, and arson. On the other hand, military security alone, unaccompanied by tangible benefits, will not convince the rural population that they should support the Government. Thus the hamlet programs serve the dual purpose of providing physical safety and a better life through enhanced Government services.

The typical hamlet has rudimentary fortifications and warning systems. The inhabitants are trained and armed to protect themselves against a Viet Cong attack until reinforcements arrive. As security improves, Government services in such fields as health, education, and agriculture are provided, in many cases with the support of US aid programs. Along with security and economic improvements comes a new political awareness and loyalty to the Central Government. Hamlet elections are held to choose representative leaders who can give voice to the people’s aspirations and who help administer the Government services.

To sum up, the New Rural Life Hamlet Program is a military, political, economic, and social program which serves to focus the efforts and energies of the military and civil agencies of the Central Government on the rural population.

Q7. What were the provisions of the 1954 Geneva agreements and how have they worked?

A7. The Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities in Viet-Nam, signed on July 20, 1954, by representatives of France and the Viet Minh, established a truce line at the 17th parallel, the Communists to withdraw to the north, the non-Communists and French to the south. Both sides were to order and enforce a complete end to hostilities, and neither zone was to be used as a military base to resume hostilities or further an aggressive policy. No new troops or military equipment were to be introduced except on a replacement or rotation basis. An International Control Commission (ICC) was created to supervise the truce.

The United States, though not a party to the agreement, declared on July 21 that it would refrain from the threat or use of force to disturb it and would view any renewal of aggression “with grave concern and as a seriously threatening international peace and security.”

A separate declaration of the conference stated that the truce line should not be considered permanent and called for nationwide elections in 2 years under the supervision of the ICC.

The Communists assumed South Viet-Nam would quickly collapse and come under the domination of Hanoi. They rightly considered that the provision for elections would work in their favor since they possessed ironclad control over the more populous northern zone and could insure that the people in the North would vote as directed.

In case the South neither collapsed nor fell to the North through elections, the Communists left thousands of arms and ammunition caches hidden in the South, along with large numbers of Viet Minh military personnel under orders to go underground until they were needed. These actions demonstrate their contempt for the Geneva agreements from the very beginning.

Complete independence from France did not come to South Viet-Nam until well after the conference. The basic decision on the form and leadership of the new Government was taken in a referendum on October 23, 1955. The country was declared a republic, and national elections were held on March 4, 1956, for a Constituent Assembly, which was transformed into a National Assembly after promulgation on the constitution it drafted.

By 1956 South Viet-Nam had thus established itself as a free republic determined to resist outside pressures and follow its own course. Government statements made between July 1954, when the Geneva accords were concluded, and July 1956, the date specified for the holding of elections, made it clear that South Viet-Nam did not regard itself as obligated to take part in elections that were not free and would thus greatly favor the North. The inability of the ICC to enforce other parts of the Geneva accords showed that adequate conditions for free elections could not be assured in the North. Under such circumstances, South Viet-Nam refused to agree to elections which could only result in its absorption into a totalitarian state.

Q8. How does the Communist campaign in Viet-Nam differ from conventional war?

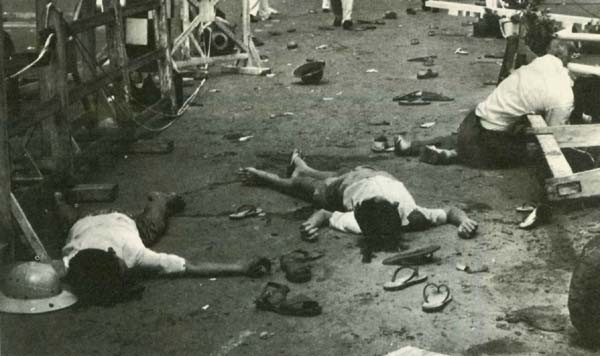

A8. Communist aggression in Viet-Nam aims at people primarily, not territory or military targets, though in support of this aim there is constant Viet Cong military action against Government forces.

The Communist weapons are murder, arson, sabotage, random bombings, and torture – aimed at terrorizing the civilian population and destroying the structure of Government, and back-stopped by well-equipped conventional forces capable of up to regimental-size operations.

The Viet Cong use political and propaganda techniques to supplement and pave the way for military action.

They concentrate on peasants and their villages, in an effort to undermine morale and loyalty to the Government.

The Communists use assassination as a weapon to damage the social structure of the nation, killing school teachers, health workers, local administration, and key officials.

This new type of aggression is harder to recognize and harder to combat than conventional warfare. It seeks to destroy a country from within, a more insidious but no less effective method of waging war than conquest by visible military force. In the case of South Viet-Nam it seeks to destroy the legitimate Government and social institutions and replace them with the total control on which Hanoi’s brand of communism relies.

Q9. What is the latest and most realistic estimate of the military situation in South Viet-Nam?

A9. The military situation in South Viet-Nam deteriorated from mid-1963 until early this year. In recent months it appears to have stabilized. While the overthrow of the Diem regime brought a measure of national unity, it also disrupted administration and military operations. Control of the countryside was reduced and some territory was lost to the Viet Cong—losses now in the process of being recouped.

Both sides have shown improvement in their ability to conduct both large- and small-scale operations, including ambushes. While the Viet Cong still concentrate on the propaganda and terrorism, they can also mount highly effective actions of battalion size and larger.

The Viet Cong remain an elusive enemy, and many Government operations do not make contact. However, under General Khanh, Government forces have shown particular improvement in their ability to conduct small unit operations, meeting the Viet Cong on their own ground and using such tactics as night attacks and ambushes.

Q10. What is the relative strength of the opposing forces in South Viet-Nam?

A10. The total strength of the regular Vietnamese Government forces is about 200,000. They are supplemented by an approximately equal number of semimilitary regional and popular forces. Viet Cong forces, including irregulars, number about 95,000 to 105,000.

Q11. Why do we think, after the French defeat in Viet-Nam, that we have any better change of success?

A11. The basis of the US presence and commitment in Viet-Nam is entirely different from that of France after World War II. By the end of the Indochina war in 1954, France was fighting a Communist-led Viet Minh that had captured leadership of the independence movement by assassination, terror, and disguise. Because France refused to grant true independence, many Vietnamese nationalists sat on the fence rather than join either side. To achieve their goals French troops were actively committed to combat against the Vietnamese, on Vietnamese soil, under the French flag.

The United States, on the other hand, has no colonial or territorial aims anywhere in Southeast Asia. Both we and the Vietnamese see the war in Viet-Nam as a Vietnamese war which must be fought and won by the Vietnamese people, who are seeking to preserve their freedom and independence against a new form of “colonialism,” in this case imposed by the Communist regime in Hanoi. The United States is there at the request of the Vietnamese Government solely to provide the economic, military, and training assistance needed to help the Republic of Viet-Nam successfully oppose the Communist-inspired and -controlled insurgency.

Q12. Isn’t the war in South Viet-Nam a civil war and thus no concern of ours?

A12. Far from being a civil war, the war in South Viet-Nam is the result of the announced attempt by the Communist regime in North Viet-Nam to conquer South Viet-Nam in violation of the 1954 Geneva accords. In Communist propaganda this form of aggression masquerades as a “war of national liberation.” In reality, the war which the Viet Cong are waging against South Viet-Nam is directed politically and militarily from Hanoi, the capital of North Viet-Nam. It is commanded primarily by leaders infiltrated from north of the 17th parallel. It is supplied by weapons and equipment sent by North Viet-Nam, which in turn is supported by Red China. Its aim is to win control of South Viet-Nam for communism, in violation of solemn agreements and with no reference to the wishes of the South Vietnamese people.

Q13. What is meant by “war of liberation?”

A13. The Communists have adopted this phrase, first used by Soviet Premier Khrushchev in 1961, to describe they type of indirect aggression they have undertaken in Viet-Nam. In their propaganda pronouncements it is used to give the impression of a war fought by a local population to throw off foreign domination. Such a description does not fit the situation in South Viet-Nam. The “liberation” offered by North Viet-Nam means domination by Hanoi. The South Vietnamese are fighting to preserve their freedom and independence from this “liberation.”

This new formula for aggression as applied in South Viet-Nam uses conventional military confrontations in conjunction with terror as weapons to destroy government and social order and replace them with the total control on which Hanoi’s brand of communism relies. It is just as real and dangerous as other forms of aggression that threaten peace.

Q14. How do you account for the fact that the Communists can instill such a strong will to fight in their followers?

A14. Communist authorities make effective use of rigid indoctrination and fear to maintain tight discipline and control among the Viet Cong, who are taught to believe that they are fighting to “liberate” South Viet-Nam for communism, the “wave of the future” in Asia, according to their instructors. The Viet Cong draw encouragement from the support they receive, material and psychological, from North Viet-Nam and Communist China. With this ideological underpinning they are trained to kill without qualms, to endure privations beyond normal human capacity, and to ignore the rights of others. The ideological commitment is regularly strengthened by indoctrination programs and propaganda in the field. Harsh punishments and death are the fate of a Viet Cong solider who doesn’t conform.

Despite these constant efforts it is not true that Viet Cong morale and motivation are always high. There are many reports of low morale caused by food shortages, low pay, unpleasant duty, and forced labor. Viet Cong leaders must constantly combat this type of weakening morale. When they are unable to build up Viet Cong spirits by persuasion they resort to force. Many Viet Cong in the lower ranks undoubtedly serve because of fear.

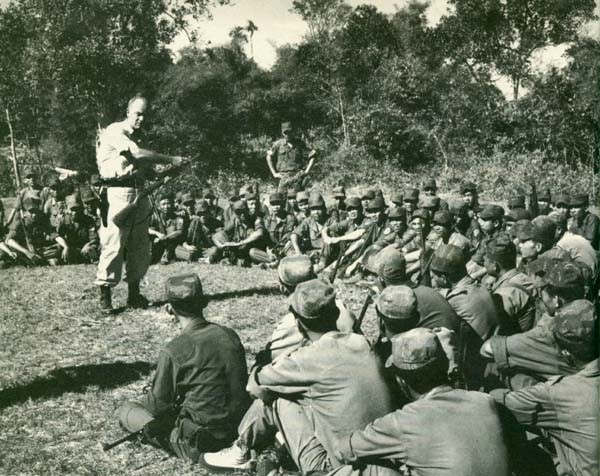

Q15. Are the Vietnamese good soldiers?

A15. In the opinion of the US military advisers who work most closely with them, the Vietnamese soldiers are capable and willing fighters. Many actions carried out by South Vietnamese forces have been launched in the face of intense enemy fire. Such operations could not have been performed by apathetic or reluctant soldiers. Government forces have sustained a high rate of casualties, a further indication of their willingness to take risks under fire. The many examples of individual Vietnamese heroism are too numerous to mention.

To be sure, there have been some instances of poor unit or individual performance—as in all armies. But these are exceptions. The Vietnamese are fighting to protect their homeland and their families. Overall, and especially in regions near their homes; Vietnamese soldiers have proven themselves to be skilled and courageous fighters.

Q16. It has been said that night operations—essential in a guerilla war—are not being conducted by the Vietnamese forces against the Viet Cong. Is this true?

A16. Failure to conduct night operations, especially of the small unit size necessary for effective antiguerilla warfare, was a serious shortcoming of the Government military forces under the Diem regime.

The present leadership recognizes that night operations are essential, and they are being undertaken by the Vietnamese regular and paramilitary forces with increasing frequency and effectiveness.

Q17. What about charges of brutality against captured Viet Cong by Vietnamese Government troops?

A17. There have been several widely publicized allegations along these lines. While it must be recognized that occasionally regrettable incidents do occur in combating an enemy who uses carefully planned murder, terror, and atrocities—particularly against civilians—as his own standard weapons, it cannot be emphasized strongly enough that the Governments of the United States and Viet-Nam condemn such actions.

Q18. What are the casualty figures—killed and injured—in Viet-Nam for Americans and Vietnamese?

A18. From January 1, 1961, through August 10, 1964, 181 American military personnel have been killed in action in Viet-Nam and over 900 have been wounded. There have been 84 deaths from noncombat causes.

In the last 5 years almost 20,000 South Vietnamese military have been killed, over 12,000 captured, and over 35,000 wounded.

During 1963, South Vietnamese civilian casualties resulting from Communist terrorist acts totaled 17,710, broken down as follows:

| Assassinated | ||

| Civilian population | 1,558 | |

| Local government officials | 415 | |

| Civil Servants | 100 | |

| Injured | 8,375 | |

| Kidnapped | 7,262 | |

Q19. What is the “South Viet-Nam National Liberation Front?”

A19. This organization was created in December 1960 by North Viet-Nam to provide a façade of political organization for their campaign of armed subversion of South Viet-Nam. It is unabashedly controlled from Hanoi. Its leadership is not well known in South Viet-Nam and includes none of the real opposition politicians who were out of government or in exile during the Diem years. What political support it has rests largely on fear and force of arms. Its purpose is to serve as a “popular front” for the Viet Cong, and to this end it conducts extensive propaganda both at home and abroad. Its broadcasts and publications depict the United States as a colonialist power, the South Viet-Nam Government as dictatorial, and the Hanoi regime as representing the true government of all Viet-Nam. The front advocates an end to the fighting through neutralization and the “peaceful reunification” of the country.

Q20. Why do we say that the US role in Viet-Nam has been to provide advice and equipment, when everyone knows Americans have been fighting and dying in that war for more than 2 years?

A20. The United States has been the primary supplier of advisers and equipment to South Viet-Nam since 1954. Not until 1961, however, when the security situation became more critical, were US advisers placed at the battalion level of Vietnamese military units and allowed to accompany the units on operations. This step greatly increased the advisers’ usefulness because they could demonstrate techniques and could observe and point out shortcomings at first hand. It also exposed them to Viet Cong fire.

At the same time a US Air Force unit was sent to Viet-Nam to assist the Vietnamese Air Force with combat training and in developing new techniques and equipment for use against the Communist insurgents. In addition, US pilots now ferry Vietnamese soldiers to combat locations by helicopter and other types of aircraft. These roles have also brought Americans into the line of fire.

It should be stressed that the Vietnamese bear the heavy brunt of casualties. But there is no question that our involvement in this war requires the kind of exposure that risks American lives.

Q21. Why don’t American advisers take direct command of Vietnamese units?

A21. The Republic of Viet-Nam is a sovereign country and, as such, has full responsibility for the command of its own military forces. US personnel work closely with their Vietnamese counterparts, giving advice and assistance of various kinds. For them to give the actual commands would not change the operational situation significantly, since Vietnamese officers provide courageous, capable leadership. It would also raise two serious difficulties.

First, for US officers to take command of Vietnamese units would be to put us in the position of the French. It would smack of colonialism. It would damage the Vietnamese will to fight for themselves and would be vigorously and profitably exploited in Viet Cong propaganda.

Second, it would aggravate the language problem, since Vietnamese enlisted men do not speak English or French, and not enough US advisers speak fluent Vietnamese. Attempting to command field operations with the aid of interpreters would be cumbersome and unsatisfactory. The training, advice, and support functions are well handled since the language problem is much less serious at the officer level.

Q22. Why not send US combat units to fight in South Viet-Nam?

A22. The military problem facing the armed forces of South Viet-Nam at this time is not primarily one of manpower. Basically it is a problem of acquiring training, equipment, skills, and organization suited to combating the type of aggression that menaces their country. Our assistance is designed to supply these requirements.

The Viet Cong use terrorism and armed attack as well as propaganda. The Government forces must respond decisively on all appropriate levels, tasks that can best be handled by Vietnamese. US combat units would face several obvious disadvantages in a guerilla war situation of this type in which knowledge of terrain, language, and local customs is especially important. In addition, their introduction would provide ammunition for Communist propaganda which falsely proclaims that the United States is conducting a “white man’s war” against Asians.

Q23. If the situation gets worse, will American dependents be removed from Viet-Nam?

A23. The decision on whether dependents come to or remain in Viet-Nam is up to each individual family, assuming that housing is available. In the case of military personnel, only a limited number are authorized to bring their dependents. There are now approximately 1,600 US dependents in Viet-Nam, about half of whom are military dependents. At present no change is contemplated in the policy of individual choice.

Q24. Is it true that the equipment we have supplied to the Government of Viet-Nam and to our own personnel is inadequate and obsolescent?

A24. Definitely not. From the start of our stepped-up involvement in Viet-Nam the highest possible priority has been given to requests for supplies and equipment from our personnel there and from Vietnamese forces, in terms of both quality and quantity. The equipment supplied has been in excellent condition and, in every case, represented what was required for the situation.

It had to be suited to the nature of the Viet Cong threat and the geographical environment, and such needs are not always best satisfied by the most modern equipment in US service inventories. For example, while the standard rifle in the US Army is the M-14, the M-1 has proven adequate in Viet-Nam. The smaller Vietnamese also make good use of the lighter and older carbines. Our latest jet aircraft are less suitable for use in Viet-Nam than are propeller aircraft, which can be used on shorter, less developed runways on which jet aircraft cannot operate. The propeller airplanes are also better suited to the flying experience of the Vietnamese pilots and easier for the ground crews to service.

On the other hand, much of the equipment sent to Viet-Nam is of the most advanced type, where this is best for the purpose. An example is the new M-113 armored personnel carriers, which have helped provide an important mobility advantage over the Viet Cong.

Q25. How does the US AID program complement the military effort?

A25. US assistance to Viet-Nam is organized to take account of the close relationship between political and military measures in this war.

In each of the 42 mainland provinces of South Viet-Nam a United States military advisory group and AID (Agency for International Development) representative work together to provide advice and assistance to the Vietnamese province chief. Members of the AID mission help bring prompt social and economic benefits to villages as soon as Vietnamese military forces, in many cases assisted by US advisers, have cleared an area of Viet Cong guerillas. Initially, relief supplies are provided to families who have suffered from Communist attack or have moved their homes into defended villages. As security is restored, American aid helps provide the villagers with the means to better their lives with a broad variety of programs, including medical, education, agriculture, transportation, well digging, channel dredging, road building, food distribution, and communications.

Because aid is distributed jointly with the Vietnamese Government, these programs have the additional benefit of helping forge administrative links between the villages and the Central Government in Saigon.

Q26. What about charges of waste and inefficiency in US aid to Southeast Asia?

A26. Through years of bitter fighting against the Communist Viet Cong, American economic aid has helped South Viet-Nam and Laos to stay afloat and to mount a resistance that still denies most of the area to Communists.

Both AID and military assistance personnel have lost their lives to Viet Cong guerillas and terrorists. The Viet Cong have spared no effort in their attempt to sever the AID lifeline. Supply trains are regularly ambushed or derailed. Snipers ambush malaria control spray teams. Relief supplies must be airlifted to refugees in areas where road transport is absent or too dangerous. AID technicians, seeking to improve the lives of villagers, work and live, like the villagers, in village hamlets that are ringed with sharpened bamboo stakes to guard against Viet Cong attack.

Recently there have been allegations in this country that some economic aid to Viet-Nam and Laos has been wasted or not used efficiently. Some of these charges are false. Some are perfectly true. All of the information in these allegations was known to the AID because it comes from the AID’s own investigative and auditing records. Obviously, administering an assistance program under what are essentially wartime conditions is a very different matter from supervising a normal program of assistance. However, the agency has never let these conditions justify a slackening in its audit and supervisory activities.

Very simply, an aid program that is the active operating tool and the lifeline of a counterinsurgency effort in a country at war is not a loan from the bank and cannot be audited in the same way.

Q27. Do the US air strikes against North Viet-Nam’s PT boat bases mean we intend to carry the war to North Viet-Nam?

A27. No. That action was limited in scale and purpose. Its only targets were the weapons and facilities which were used to attack US vessels on the high seas. Its sole intent was to make it unmistakably clear that the United States will not tolerate aggression against its naval forces in international waters and that we will not be deterred by such attacks from discharging our obligations to friendly nations seeking to defend their independence against Communist attack.

Q28. Why not carry the war to North Viet-Nam?

A28. This course of action—its implications and ways of carrying it out—is under continuing study. Whatever ultimate course of action may be forced upon us by the other side, it is clear that actions outside of South Viet-Nam would be only a supplement to, not a substitute for progress within S. Viet-Nam’s own borders.

This conflict within South Viet-Nam must be pursued with the greatest possible vigor and with all possible US support. Wider action is not excluded, but wider action must proceed alongside progress within South Viet-Nam itself if it is undertaken. The main task in South Viet-Nam is to defeat the Communist Viet Cong guerillas and to establish the authority of the government over all South Viet-Nam.

Any decision to expand the war must take into full account of all possible consequences of such action and its implications for the whole of Southeast Asia. As President Johnson said on June 23, 1964:

“The United States intends no rashness and seeks no wider war. But the United States is determined to use its strength to help those who are defending themselves against terror and aggression. We are a people of peace—but not of weakness or timidity.”

Q29. Why not end the fighting in South Viet-Nam by neutralization through negotiation?

A29. What is meant by “neutralization?” If it means that South Viet-Nam is permitted to develop in peace according to its own wishes, free of interference or control by outside forces, then a solution is indeed at hand. It was spelled out in the 1954 Geneva accords. The fighting in South Viet-Nam is the result of the Government’s effort to defend the country against the Communists’ rampant violations of the negotiated settlement. Peace can come to South Viet-Nam if the Hanoi authorities and their agents, the Viet Cong, end their aggression and observe the terms of the agreement that was signed 10 years ago.

But the kind of “neutralization” advocated by North Viet-Nam and its puppet organization, the “National Liberation Front of South Viet-Nam,” plainly means something else. Under their formula all outside assistance to South Viet-Nam would end, despite the fact that it comes at the request of the Government. Negotiations would take place for the reunification of all Viet-Nam, and the absorption of the South into the North, an outcome long aimed at by Viet Cong terrorist tactics, would result.

Neutralization is a two-way street. In the context of current world affairs it requires a severing of ties with both sides of the struggle between communism and freedom. In repeated public statements North Viet-Nam has specifically rejected neutralization for itself. Its aim in advocating neutralization illustrates the Communist maxim “What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is negotiable.”

There is no reason to think that a new agreement to guarantee South Viet-Nam’s independence and neutrality would be effective. The Communist authorities in Hanoi and Peiping signed such an agreement for Laos at the 1962 Geneva conference. They have demonstrated no more respect for this document than for the 1954 Geneva agreement.

Nor is there any realistic prospect that a united Viet-Nam would be non-Communist or “Titoist.” First of all, the Hanoi regime still maintains strong external ambitions in regard to neighboring countries in Southeast Asia. It is militantly Communist. Moreover, for much of its history the area of Viet-Nam has been under Chinese domination. Most of the North Vietnamese top leaders have been trained in China, and there is little likelihood that they would turn away from the Peiping regime even if they could. The prospect that a united Viet-Nam under Hanoi’s control would sever ties with Communist China and follow an independent course is quite unlikely.

Q30. How is the military situation in South Viet-Nam related to that in Laos?

A30. There is unmistakable and indisputable evidence that the North Viet-Nam government provides direction and support to the Communist forces in both Laos and South Viet-Nam. The Hanoi regime aids the Viet Cong in South Viet-Nam with large numbers of military specialists, vital supplies and equipment, and key communications facilities. Much of the personnel and materiel moves into South Viet-Nam over the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” which runs through eastern Laos. The Communist forces in Laos—the Pathet Lao—are supported in similar fashion, as well as by full combat units of the North Vietnamese army.

Q31. What were the terms of the 1962 Geneva agreement on Laos?

A31. A Declaration on the Neutrality of Laos and a Protocol to the Declaration were signed at Geneva in July 1962. They stated that Laos would be independent and neutral. All foreign military personnel were to withdraw within 75 days, except a limited number of French instructors requested by the Lao Government. No arms were to be brought in except at the request of the Lao Government. The 14 signatories, who included Communist China, Communist North Vietnam, and the Soviet Union, agreed to respect the territorial integrity and to refrain “from all direct or indirect interference in the internal affairs” of Laos and from the use of Lao territory to interfere in the internal affairs of other countries. An International Control Commission was set up to assure compliance with the agreement. All signatories promised to support a three-faction neutralist coalition government under Prince Souvanna Phouma.

Q32. What happened after the 1962 agreement was signed?

A32. We withdrew all 666 of our military adviser personnel from Laos. The Pathet Lao allowed several thousand North Vietnamese military combat men to remain—these are the backbone of almost every Pathet Lao battalion. Later, additional North Vietnamese troops returned to Laos—many of them in organized battalions. The North Vietnamese have continued to use the corridor through Laos to reinforce and supply the Viet Cong in South Viet-Nam.

The Royal Lao Government opened the areas under its control to access by all Lao factions and by the International Control Commission. The Communists have denied access to the areas they control not only to other Lao groups, including the Prime Minister, but to the International Control Commission. They have fired at personnel and aircraft on legitimate missions under the authority of the Royal Lao Government.

In short, the non-Communist elements have made every effort to comply with and support the agreement; the Communist elements have persistently undercut and frustrated it.

Q33. What are US aims in Laos?

A33. We want in Laos what the Laotian people want for themselves—that they be left alone to live in peace. This is what was provided in the Geneva agreements. The signatories to those agreements pledged themselves to withdraw their forces from Laos, which was to remain independent and neutral. If those agreements had been treated as more than paper pledges by Communist North Viet-Nam, Laos, would not be troubled by war today.

Laos is a divided country with little national cohesion and with strong ethnic and cultural differences among its people. Moreover, it shares a long border with China. Under these circumstances the 1962 Geneva settlement provided an appropriate framework to remove Laos from the stage of big power confrontation and to maintain its neutrality.

Q34. What kind of assistance do we provide to Laos?

A34. We are giving substantial economic and technical assistance under AID programs. These include agricultural, health, educational, public works, rural development, and other projects. We also assist large numbers of refugees dislocated as a result of Pathet Lao aggression. Our economic aid meets basic needs of the Lao Government and people and helps to offset the heavy defense burden they must bear in response to Communist aggressiveness. To help control inflation and promote economic stability we contribute to a multilateral stabilization fund and help finance a commodity import program.

At the request of the Lao Government and in accord with the Geneva agreements we are providing small arms, artillery, ammunition, and other equipment and supplies, as well as training abroad and logistical support, to the Royal Lao Army and to the neutralist forces which help uphold Premier Souvanna Phouma’s Government of National Union. We have also helped the Laotians create a small air force having primarily a transportation function. We have provided T-28 propeller airplanes to assist in defending against the new Communist attacks.

Q35. What has brought about the present sense of crisis in Laos?

A35. Early this spring the Communist Pathet Lao began to build up their forces near the Plaine des Jarres, a key plateau area in Laos held by the neutralist forces headed by Gen. Kong Le. In early May the Pathet Lao, supported by North Vietnamese units (Viet Minh), launched a heavy assault on Kong Le’s forces, driving him and his troops off positions on the Plaine des Jarres where they had been since well before the 1962 Geneva agreement. The Pathet Lao have continued their military buildup, Viet Minh units remain in Laos, and the Viet Cong continue to receive reinforcements and supplies via the Ho Chi Minh trail through eastern Laos.

In April Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma took part in a meeting of the three factions aimed at ironing out some of the problems in Laos. The Communists deliberately broke up the meeting by insisting their demands be accepted without change. Faced with this evidence of bad faith Prince Souvanna announced his intention to resign. This precipitated an attempted seizure of power by a group of conservative military leaders in Vientiane. We oppose this action and called for the restoration of the conditions required by the Geneva agreement and support for Souvanna. The attempted coup was ended and Prince Souvanna remained as head of government. But the Communists promptly seized on this episode as a pretext for their long-planned military assault.

These Communist actions show utter disrespect for the 1962 Geneva agreement. They also raise the danger that the Pathet Lao will continue their aggressive conduct, refuse to cooperate with the legitimate Government, and try to establish themselves on the Mekong River and the Thai border.

Q36. Why not turn the problem over to the United Nations?

A36. The United Nations has been involved in Southeast Asia in a variety of ways. In 1959 the Security Council sent a commission to Laos. A UN representative has been working for some time on the border problems between Cambodia and Thailand. In 1963 the General Assembly sent a mission of inquiry to look into alleged violations of human rights in Viet-Nam.

In June 1964 the United States proposed in the Security Council that a UN force of perhaps 1,200 men should police the tense Cambodian-Vietnamese border, but there was not sufficient support for that kind of operation. Instead, a commission of three members was named to examine this border situation and to make recommendations.

Hanoi and Peiping condemned even this limited UN involvement in the Vietnamese situation. The Communist Viet Cong said they could not guarantee the safety of this commission and would not accept its findings.

UN peacekeeping forces can be extremely useful, but they work best when the parties to a dispute are willing to work out and agree to a peaceful settlement. Such a settlement was spelled out in the 1954 Geneva accords, which have been persistently and flagrantly violated by the Viet Cong and their masters in Hanoi.

It would be very difficult for the United Nations to play an effective peacekeeping role in the present situation of active hostilities, guerilla attacks, and widespread terrorism. The United Nations lacks the enormous resources that would be necessary. And it is highly unlikely that such an involvement would be approved by the Security Council.

Nevertheless, as it has in many other instances, the United Nations has served as a useful forum in which the United States has been able to bring to world attention the aggressive acts of the Communist powers in Asia. It was there, before the Security Council, for example, that US Ambassador Adlai Stevenson spelled out for all the world to see the story of Hanoi’s recent attack on two US warships.

We do not oppose a UN role in Southeast Asia. But talk of turning the problem over to the United Nations ignores the hard realities of the situation and should not be permitted to serve as a way to avoid our own responsibilities.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 7724

Far Eastern Series 127

Released August 1964

Office of Media Services

BUREAU OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS

US GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1964

[END]