The Navy Department Library

Small Wars

Their Principles and Practice

BY

COLONEL C. [CHARLES] E. [EDWARD] CALLWELL

THIRD EDITION.

GENERAL STAFF - WAR OFFICE.

1906.

LONDON:

PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE

By HARRISON and SONS, 15-47, St. Martin's Lane, W.C.,

PRINTERS in Ordinary to His Majesty.

To be purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from

WYMAN and SONS, Ltd., 29, Breams Buildings, Fetter Lane, E.G., and

54, St. Mary Street, Cardiff; or

H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE (Scottish Branch), 23, Forth Street, Edinburgh; or

E. PONSONBY, Ltd 116, Grafton Street, Dublin,

or from the Agencies in the British Colonies and Dependencies,

the United States of America, the Continent, of Europe and Abroad of

T. FISHER UNWIN, London, W.C.

(Reprinted 1914.)

Price Four Shillings.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

In preparing this new edition for the press, advantage has been taken of experiences gained in campaigns which have taken place since the book was originally compiled. These include the French advance to Antananarivo and their later operations in Madagascar, the guerilla warfare in Cuba previous to the American intervention, the suppression of the rebellions in Rhodesia, the operations beyond the Panjab frontier in 1897-98, the re-conquest of the Sudan, the operations of the United States troops against the Filipinos, and many minor campaigns in Bast and West Africa.

Some of the later chapters have been re-arranged and in part re-written, and new chapters have been added on hill warfare and bush warfare. Useful hints have been obtained from the notes which Lieut.-Colonel Septans, French Marine Infantry, has incorporated in his translation of the first edition. An index has been added.

My acknowledgments are due to the many officers who have afforded valuable information, and who have aided in revising the proofs.

Chas. E. Callwell,

Major, R.A.

July, 1899.

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION, 1906.

This book has now been revised and brought up to date by the author, Colonel C. E. Callwell. It is recommended to officer as a valuable contribution on the subject of the conduct of small wars. It is full of useful facts and information on all the details which must be considered in the management of those minor expeditions in which the British Army is so frequently engaged. But it is not to be regarded as laying down inflexible rules for guidance, or as an expression of official opinion on the subjects of which it treats.

N. G. LYTTELTON,

Chief of the General Staff.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I. Introduction. |

||

| Page | ||

| Meaning of the term "Small War" | 21 | |

| General scope of the work | 22 | |

| Arrangement adopted | 22 | |

| General treatment | 23 | |

| CHAPTER II. Causes of small wars as affecting their conditions. The various kinds of adversaries met with. |

||

| Classes into which these campaigns may be divided | 25 | |

| Campaigns of conquest and annexation and their characteristics | 25 | |

| Examples | 25 | |

| The suppression of insurrections and lawlessness, and its features | 26 | |

| This, a frequent sequel to conquest and annexation | 26 | |

| Examples | 27 | |

| Campaigns to wipe out an insult or avenge a wrong | 27 | |

| Examples | 28 | |

| Campaigns for the overthrow of a dangerous power | 28 | |

| Campaigns of expediency | 28 | |

| The great variety in the natures of enemy to be dealt with | 29 | |

| Opponents with a form of regular organization | 29 | |

| Highly disciplined but badly armed opponents | 30 | |

| Fanatics | 30 | |

| The Boers | 31 | |

| Guerillas, civilized and savage | 31 | |

| Armies of savages in the bush | 32 | |

| Enemies who fight mounted | 32 | |

| The importance of studying the hostile mode of war | 32 | |

| CHAPTER III. The objective in small wars. |

|

| Selection of objective in the first place governed by the cause of the campaign | 34 |

| Cases where the hostile country has a definite form of government | 34 |

| The question of the importance of the capital as an objective | 35 |

| When the capital is a place of real importance in the country its capture generally disposes of regular opposition | 36 |

| The great advantage of having a clear and well defined objective | 37 |

| Tirah, a peculiar case | |

| Objective when the purpose of hostilities is the overthrow of a dangerous military power | 39 |

| Objective when there is no capital and no army | 40 |

| Raids on live stock | 40 |

| Destruction of crops, etc. | 40 |

| Suppression of rebellions | 41 |

| Special objectives | 42 |

| Conclusion | 42 |

| CHAPTER IV. Difficulties under which the regular forces labour as regards intelligence. The advantage is usually enjoyed by the enemy in this respect, but this circumstance can sometimes be turned to account. |

|

| Absence of trustworthy information frequent in small wars | 43 |

| Want of knowledge may be as to the theatre of war or as to the enemy | 43 |

| Illustrations of effect of uncertainty as to routes | 44 |

| Illustrations of effect of uncertainty as to resources of theatre | 45 |

| Illustrations of effect of uncertainty as to exact position of localities | 45 |

| Uncertainty in the mind of the commander reacts upon his plan of operations | 46 |

| Effect of doubt as to strength and fighting qualities of the enemy | 47 |

| Examples | 47 |

| Uncertainty as to extent to which the hostile population itself, and the neighbouring tribes, etc., will take part in the campaign | 49 |

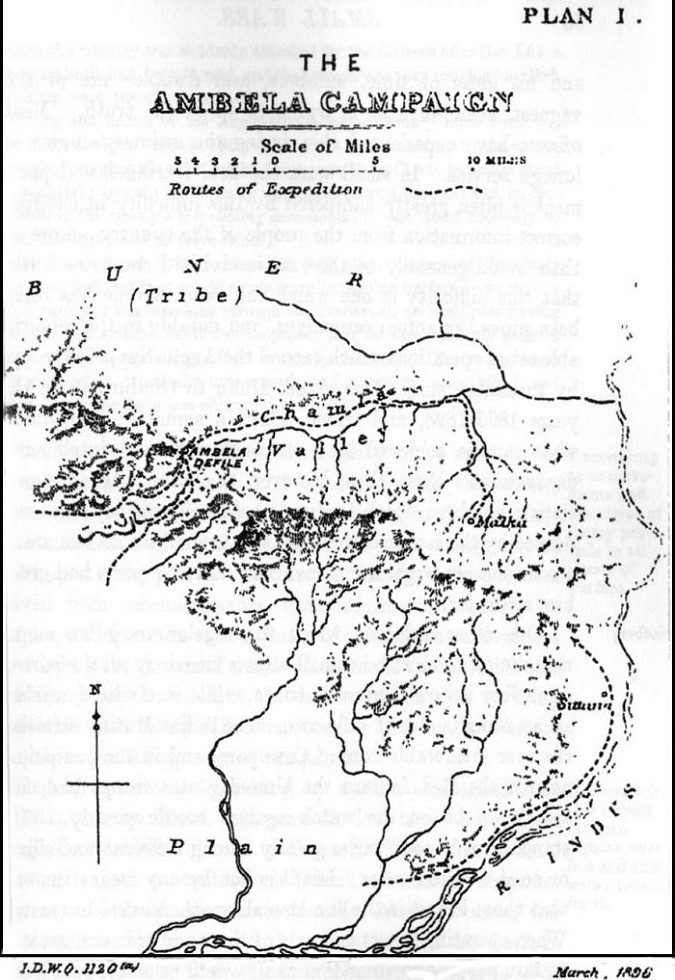

| Example of Ambela | 49 |

| Difficulty of eliciting correct information from natives | 49 |

| Treachery | 60 |

| Uncertainty as to movements and intentions of enemy prevails in all classes of warfare | 51 |

| Difference in this respect between regular warfare and small wars; reasons for it | 51 |

| Advantages enjoyed by the enemy as regards intelligence | 53 |

| Knowledge of theatre of war | 53 |

| The enemy seems always to know the movements of the regular army | 53 |

| This can be turned to account by publishing false information as to intentions | 54 |

| Conclusions arrived at in chapter only to be considered as generally applicable | 55 |

| CHAPTER V. The influence of the question of supply upon small wars and the extent to which it must govern the plan of operations. |

|

| Small wars when they are campaigns against nature are mainly so owing to supply | 57 |

| Reasons for this | |

| Connection between supply and transport | 58 |

| Supply trains in small wars | 58 |

| Difficulties as to supply tend to limit the force employed | 60 |

| The question of water | 60 |

| Supply a matter of calculation, but there is always great risk of this being upset by something unforeseen | 62 |

| Rivers as affecting supply in small wars | 63 |

| The boat expeditions to the Red River and up the Nile | 64 |

| Principle of holding back the troops and pushing on supplies ahead of them | 65 |

| Examples illustrating this | 66 |

| Example of a theatre of war being selected owing to reasons of supply | 67 |

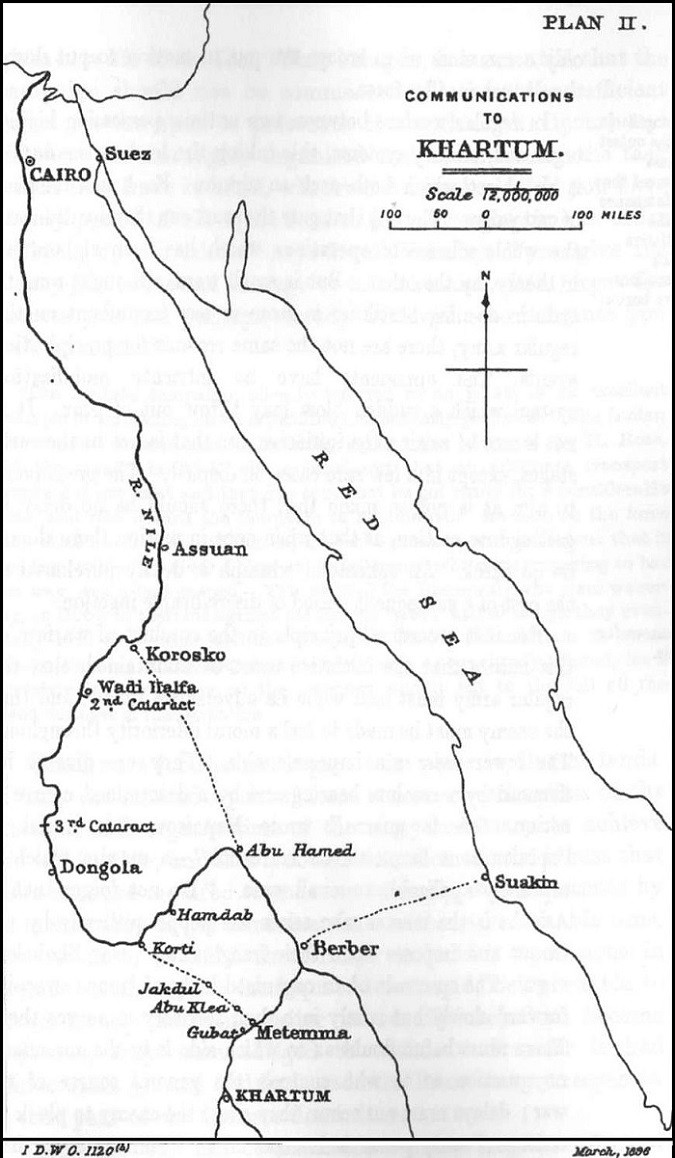

| The Nile Expedition a remarkable illustration of the subject of this chapter | 68 |

| Sketch of this campaign from the point of view of supply | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI. Boldness and vigour the essence of effectively conducting such operations. |

|

| The initiative | 71 |

| Forced upon the regular army to start with | 71 |

| Promptitude at the outset of less moment than the maintenance of the initiative when operations have begun | 72 |

| Reasons for this | 72 |

| Examples of evil consequences which arise from insufficient organization when the campaign is in progress | 74 |

| Examples of decisive results being obtained by promptitude at the outset | 74 |

| Strategical offensive essential | 75 |

| This not incompatible with tactical defensive | 76 |

| Effect of decisive action upon waverers in the hostile ranks and upon those hesitating to throw in their lot with the enemy | 76 |

| Even when the regular army is obliged to act strategically on the defensive this must not be a passive defensive | 77 |

| Great impression made upon the enemy by bold and resolute action | 78 |

| The importance of following up successes with vigour | 70 |

| Small forces can at times perform exploits of great subsequent importance by means of bluff | 80 |

| Examples | 81 |

| Conclusion | 83 |

| CHAPTER VII. Tactics favour the regular army while strategy favours the enemy, therefore the object is to fight, not to manoeuvre. |

|

| The regular forces are at a disadvantage from the point of view of strategy | 85 |

| Communications a main cause of this | 85 |

| Enemy has little anxiety as to communications, and operations cannot be directed against them | 86 |

| Examples of this | 87 |

| The enemy's mobility benefits him strategically | 87 |

| His power of sudden concentration and dispersion | 88 |

| Note that the mobility of the enemy does not necessarily prevent strategical surprises by the regulars | 89 |

| The better organized the enemy the less does he enjoy the strategical advantage | 90 |

| On the battle-field the advantage passes over to the regular forces | 90 |

| Reasons for the tactical superiority of the organized army | 90 |

| Since tactical conditions are favourable, while strategical conditions are the reverse, the object is to bring matters to a tactical issue. Usually better to fight the enemy than to manoeuvre him out of his position | 91 |

| Example of Tel-el-Kebir | 92 |

| Objection to elaborate manoeuvres as compared to direct action | 92 |

| Circumstances when this principle does not hold good | 94 |

| The question of the wounded | 95 |

| How this may hamper the regular troops strategically | 96 |

| CHAPTER VIII. To avoid desultory warfare the enemy must be brought to battle, and in such manner as to make his defeat decisive. |

|

| Prolonged campaigns to be avoided | 97 |

| Reasons for this | 97 |

| Troops suffer from disease | 97 |

| Supply difficulties render protracted operations undesirable | 98 |

| Enemy gains time to organize his forces | 98 |

| Desultory operations tend to prolong a campaign | 98 |

| Guerilla warfare very unfavourable to regular troops | 99 |

| Indecisive conduct of campaign tends to desultory warfare | 100 |

| Examples | 100 |

| Skirmishes should be avoided | 102 |

| Sometimes desirable to conceal strength so as to encourage enemy to fight | 102 |

| General engagements the object to be aimed at | 103 |

| Examples | 103 |

| Campaigns where circumstances oblige the enemy to adopt a decisive course of action are the most satisfactory | 105 |

| Owing to difficulty of getting enemy to accept battle, it is expedient to ensure a decisive victory when he does so | 106 |

| Battles sometimes to be avoided if losses cannot be risked | 107 |

| CHAPTER IX. Division of force, often necessitated by the circumstances, is less objectionable in these campaigns than in regular warfare. |

|

| Usual objections to division of force | 108 |

| Conditions of campaign often render it unavoidable in small wars | 108 |

| Moral effect of numerous columns | 109 |

| Enemy unable to profit by the situation and confused by several invading forces | 110 |

| Examples | 111 |

| Several columns have advantage that, even if some fail to make way, others succeed | 111 |

| Separation only permissible if each portion can stand by itself | 112 |

| Difficulty of judging requisite strength | 112 |

| Separation dangerous when superiority is not established | 113 |

| Difficulty of calculating upon exact co-operation between two separated forces intended to unite for some particular object | 113 |

| CHAPTER X. Lines ok communications, their liability to attack, the drain they are upon the army, and the circumstances under which they can be dispensed with. |

|

| Organization of lines of communication need not be considered in detail | 115 |

| Their length and liability of attack | 116 |

| Need of special force to guard them | 116 |

| Examples | 117 |

| Large numbers of troops absorbed | 117 |

| Abandoning communications altogether | 118 |

| Liberty of action which the force gains thereby | 118 |

| It involves the army being accompanied by large convoys | 119 |

| Question greatly affected by the length of time which the operation involves | 120 |

| Partial abandonment of communications | 120 |

| Examples of armies casting loose from their communications for a considerable time | 121 |

| Sir F. Roberts' daring advance on Kabul | 122 |

| Risks attending this | 122 |

| Inconvenience which may arise from the force being unable to communicate with bodies with which it may be co-operating | 123 |

| Conclusion as to abandonment of communications | 124 |

| CHAPTER XI. Guerilla warfare in general. |

|

| Guerilla warfare in general | 125 |

| Influence of terrain | 127 |

| Promptitude and resolution essential to deal with guerillas | 127 |

| Abd-el-Kader | 128 |

| General Bugeaud's mode of crushing him | 128 |

| Campaigns when want of mobility and decision on the part of the regular troops against guerillas has had bad effect | 129 |

| The broad principles of the strategy to be employed against guerillas | 130 |

| The war in Cuba | 131 |

| The sub-division of the theatre of war into sections | 133 |

| Fortified posts and depots | 134 |

| Flying columns | 135 |

| Their strength and composition | 136 |

| Columns of mounted troops in certain theatres of war | 136 |

| Suppression of the rebellion in Southern Rhodesia | 137 |

| The columns in the South African War | 139 |

| Danger of very small columns | 140 |

| Need for independence | 142 |

| Difficulty of controlling movements of separated columns | 142 |

| The South African "drives" | 143 |

| Need of a good Intelligence department in guerilla warfare, and of secrecy | 143 |

| Carrying off cattle and destroying property | 145 |

| Objection to the principle of raids | 146 |

| Pacification of revolted districts | 147 |

| Hoche in La Vendee | 147 |

| Upper Burma | 147 |

| Severity sometimes necessary | 148 |

| Conclusion | 148 |

| CHAPTER XII. Tactics of attack. |

|

| Offensive tactics generally imperative | 150 |

| How theory of attack differs in small wars from regular warfare | 150 |

| Artillery preparation | 152 |

| When and when not expedient | 152 |

| Objections to it | 153 |

| If enemy is strongly posted sometimes very desirable | 154 |

| It also sometimes saves time | 154 |

| Instances of want of artillery preparation | 154 |

| Importance of capturing enemy's guns | 156 |

| Trust of irregular warriors in their guns | 157 |

| Importance of capturing trophies | 158 |

| Difficulty of ensuring decisive success | 159 |

| Reasons for this | 159 |

| Objection to purely frontal attacks, advantage of Hank attack | 160 |

| Enemy seldom prepared for flank attacks, or attack in rear | 161 |

| Examples | 161 |

| Flank attacks give better chance of decisive victory | 162 |

| Containing force, in case of attacks on the flank or rear of the company | 163 |

| Action of Kirbekan, a rear attack | 164 |

| Co-operation of containing force | 164 |

| Main attack on the flank | 164 |

| Peiwar Kotal | 165 |

| Enemy inclined to draw away his forces to meet the Hank attack and so opens the way for a frontal attack | 166 |

| Difficulty of ensuring combination between a front and a flank attack | 167 |

| Ali Musjid | 168 |

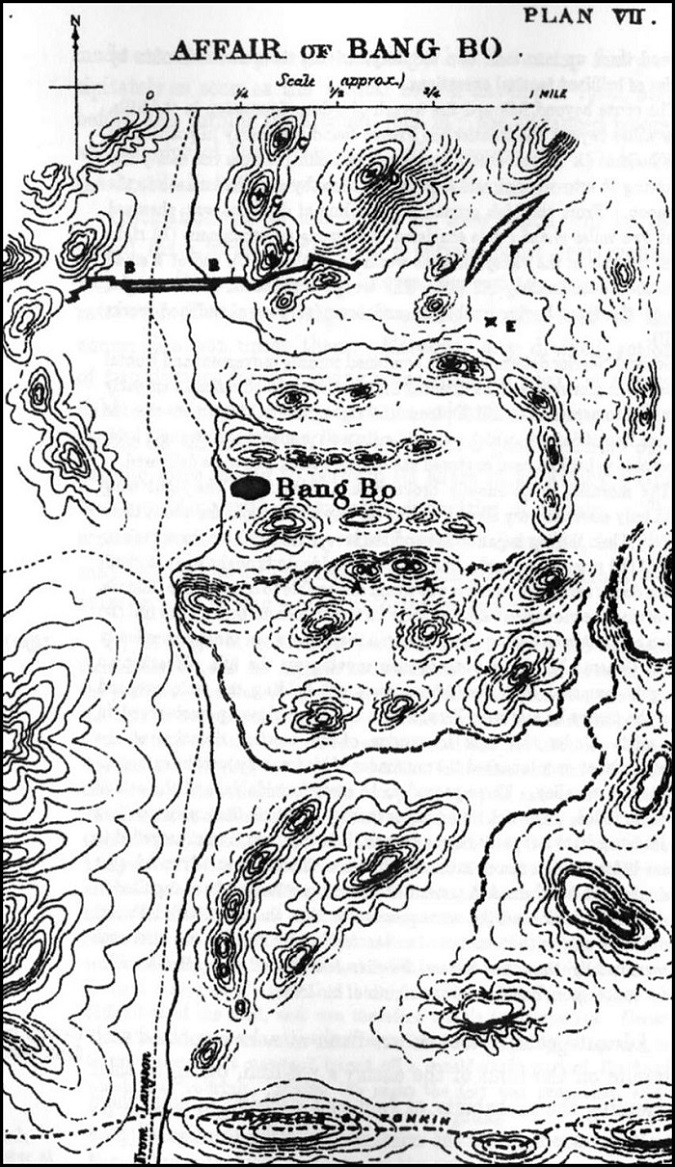

| French disaster at Bang Bo | 168 |

| Cavalry in flank attacks | 169 |

| Artillery in flank attacks | 170 |

| Imperative necessity of following up a preliminary success | 170 |

| Need of initiative on the part of subordinates in attack | 171 |

| Cavalry to be at hand to complete victory | 172 |

| Other arms to play into the hands of the cavalry | 173 |

| Importance of the cavalry acting at the right moment | 173 |

| Artillery to be pushed up to the front to play on enemy when line | |

| gives way | 174 |

| Attack often offers opportunities for deceiving the enemy as to available strength, and thus for gaining successes with insignificant forces | 175 |

| The separation of force on the battlefield | 175 |

| Advantages of this | 177 |

| Examples | 177 |

| Disadvantages | 178 |

| Enemy may beat fractions in detail | 178 |

| Difficulty of manoeuvring detached forces effectively | 180 |

| Detached bodies may fire into each other | 181 |

| Risk of misunderstandings | 182 |

| Examples | 183 |

| Note on the battle of Adowa | 184 |

| Risk of counter-attack | 184 |

| Examples of hostile counter-attack | 185 |

| Need of co-operation between infantry and artillery to meet counterattacks | 186 |

| Tendency of enemy to threaten flanks and rear of attacking force | 186 |

| The battle of Isly | 187 |

| An illustration of an echelon formation | 188 |

| Remarks on the echelon formation | 188 |

| Importance of pressing on, and not paying too much attention to demonstrations against flanks and rear | 189 |

| Attacks on caves in South Africa | 191 |

| Hour for attack | 192 |

| Attacks at dawn | 192 |

| Examples | 193 |

| Attacks early in the day expedient, to allow of effective pursuit | 194 |

| CHAPTER XIII. Tactics of defence. |

|

| Defensive attitude unusual, but sometimes unavoidable | 195 |

| Small bodies of regular troops hemmed in | 196 |

| Even then defensive must not be purely passive | 196 |

| Examples of minor counter-attacks under such circumstances | 197 |

| A counter-attack on a large scale must not miscarry where the army is in difficulties | 198 |

| Evils of passive defence if not imperative | 199 |

| Examples | 200 |

| Active defence | 201 |

| Remarks on defensive order of battle | 202 |

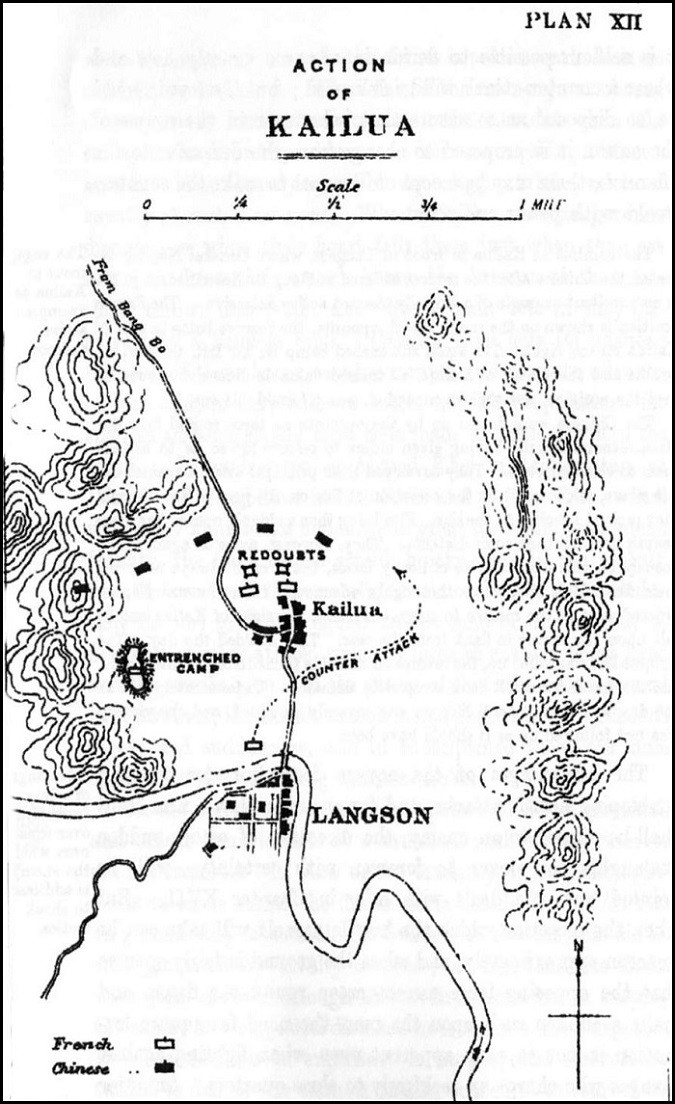

| The engagement at Kailua as example of active defence | 203 |

| Advantages of a line formation over square, even when the enemy is addicted to shock tactics | 203 |

| Examples | 204 |

| Difficulty as to flanks | 205 |

| The enemy may decline to attack | 205 |

| Conclusion | 206 |

| CHAPTER XIV. Pursuits and retreats. |

|

| Enemy not prepared for a vigorous pursuit if beaten, or for following up their victory with energy if triumphant | 207 |

| Their mobility makes them difficult to pursue | 207 |

| Infantry in pursuit | 208 |

| Need for great vigour | 209 |

| Detached force to strike in on line of retreat | 209 |

| Tendency of the enemy to disperse in all directions | 210 |

| Use of cavalry and horse artillery in pursuit | 211 |

| Retreats | 211 |

| Difficulty caused by carrying off wounded in retreat | 212 |

| Retreat draws down upon the troops the waverers in the hostile ranks | 212 |

| Enemy's eagerness at first to follow up a retiring force | 213 |

| Examples | 213 |

| Although irregular warriors at first keen in pursuit their ardour soon cools | 214 |

| Examples | 215 |

| Annihilation of regular forces due generally to their being completely isolated or to special causes | 216 |

| Beginning of retreat the critical period | 216 |

| General organization of a retreat | 217 |

| General Duchesne's orders | 218 |

| Note as to retreat in face of very determined adversaries who rely on shock attacks | 219 |

| Rearguards | 219 |

| Importance of main body keeping touch with the rear guard withdrawal of rear guards counter-attack sometimes the wisest course when a rear guard is in serious difficulty | 220 |

| Lieut.-Col. Haughton at the retreat from the Tseri Kandao pass | 224 |

| Conclusion | 225 |

| CHAPTER XV. The employment of feints to tempt the enemy into action and to conceal designs upon the battlefield. |

|

| Drawing the enemy on | 227 |

| Reasons why this can so often be carried out | 227 |

| How enemy's eagerness to follow up a retiring force can be turned to account | 228 |

| Hostile leaders cannot control their followers | 229 |

| The Zulus drawn into a premature attack at Kambula | 229 |

| Other examples | 230 |

| Value of the stratagem of pretended retreat in insurrectionary wars | 231 |

| Cavalry especially well adapted for this sort of work | 231 |

| Enticing the enemy into an ambuscade | 232 |

| Enemy sometimes drawn on unintentionally | 233 |

| Examples of Arogee and Nis Gol | 233 |

| Drawing the enemy on by exposing baggage, etc. | 234 |

| Drawing enemy on by artillery fire | 234 |

| Inducing the enemy to hold his ground when inclined to retire | 235 |

| Feints as to intended point of attack | 235 |

| In some cases the enemy cannot be drawn into action | 235 |

| The action of Toski as an illustration of this | 237 |

| Conclusion | 238 |

| CHAPTER XVI. Surprises, raids and ambuscades. |

|

| Surprise a favourite weapon of the enemy, but one which can also be used against him | 240 |

| Best time of day for surprises | 240 |

| By day a rapid march from a distance is generally necessary | 241 |

| Mobility essential in troops employed | 241 |

| Importance of keeping the project secret | 242 |

| Enemy to be put on a false scent if possible | 244 |

| Raids a form of surprise | 245 |

| Raids on the live stock of the enemy | 245 |

| The French "razzias" in Algeria | 246 |

| Difficulty of bringing in captured cattle, etc. | 247 |

| Ambuscades | 248 |

| Ease with which the enemy can sometimes be drawn into them | 248 |

| Remarks on the arrangement of ambuscades | 250 |

| Points to bear in mind | 252 |

| Skill of the enemy in devising ambuscades in small wars | 252 |

| The ambuscade at Shekan | 254 |

| Other examples | 254 |

| CHAPTER XVII. Squares in action on the march and in bivouac. |

|

| Square formation cannot be satisfactorily treated under the head either of attack or defence | 256 |

| Object of square formation | 256 |

| Enemy's tendency to operate against the flanks and rear of regular troops | 257 |

| Two forms of squares, the rigid and the elastic. The rigid form here dealt with | 258 |

| Usual formation | 259 |

| Squares in action. A formation at once offensive and defensive | 259 |

| Example of Achupa in Dahomey | 259 |

| Organization of squares in action | 260 |

| Abu Klea | 261 |

| Question of skirmishers | 261 |

| How to deal with gaps | 262 |

| Suggestion as to reserves in squares | 262 |

| The corners | 263 |

| Position of artillery | 263 |

| Position of cavalry | 264 |

| Question of forming two or more squares | 265 |

| Square affords a target for the enemy | 266 |

| Limited development of fire from a square | 267 |

| Square in attack | 267 |

| Tamai | 267 |

| Capture of Bida | 268 |

| Square formation has frequently proved most effective | 269 |

| Square formation as an order of march | 270 |

| Forming square on the move | 270 |

| Difficulties of marching in square | 272 |

| Suakin 1885 | 273 |

| Artillery and cavalry with reference to squares on the march | 274 |

| Bivouac in square | 276 |

| Conclusion | 276 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. Principles of laager and zeriba warfare. |

|

| General principles of laager and zeriba warfare | 277 |

| Tactically a defensive system | 278 |

| Objections to this | 278 |

| Situations where laagers and zeribas are very necessary | 279 |

| Their value in dealing with guerillas | 279 |

| Conditions necessary for their construction | 280 |

| Campaigns in which laagers and zeribas have been largely used | 280 |

| Their special advantages | 282 |

| Economy of outposts | 282 |

| Security at night | 282 |

| They generally, but not necessarily, enable the regular troops to select their ground and time for fighting | 282 |

| They afford the troops repose during prolonged operations | 284 |

| Zenbas may become defence posts upon the line of communications, or may serve as supply depots in advance of an army | 284 |

| General conclusions | 285 |

| CHAPTER XIX. Hill warfare. |

|

| Explanation of the term "hill warfare" | 286 |

| Its difficulties in all parts of the world | 286 |

| "Sniping" | 287 |

| Retirements unavoidable at times | 287 |

| Care of the wounded | 288 |

| Special risk to officers in Indian frontier fighting | 288 |

| Enemy generally warlike and nowadays well armed | 289 |

| Stones and trees can be thrown down on the troops | 289 |

| Size of columns | 290 |

| Several columns usual | 291 |

| Length of marches | 291 |

| The troops generally on the lower ground, the enemy on the heights | 292 |

| "Crowning the heights" | 292 |

| Examples of neglect of this | 292 |

| Enemy's dislike of attacking up hill and of being commanded | 293 |

| Seizing the high ground in attacking a defile | 294 |

| Occupying the heights in moving along a valley or defile | 294 |

| Moving flanking parties, and stationary flanking piquets | 294 |

| General arrangement when stationary picquets are adopted | 295 |

| Remarks on flanking picquets | 296 |

| Remarks on moving flanking parties | 298 |

| Comparison of system of crowning the heights to square formation | 299 |

| Retirement a necessity at times, but general conduct of operations should be such as to render them as infrequent as possible | 299 |

| Reconnaissances, in reference to this | 300 |

| Forces detached for particular objects, in reference to it | 300 |

| Holding capture heights, in reference to it | 302 |

| The case of Dargai | 302 |

| Troops not to get into clusters under enemy's fire | 303 |

| Remarks on attack in hill warfare | 304 |

| The Gurkha scouts attacking above Thati | 305 |

| Turning movements not to be undertaken too readily | 306 |

| Mountain guns and cavalry in attack in hill warfare | 307 |

| Remarks on the destruction of villages | 308 |

| The work must be carried out deliberately | 308 |

| Principle of attacking a village | 309 |

| Presence of women and children in villages | 310 |

| Stone throwers | 310 |

| The difficulty of communicating orders during action in hill warfare | 310 |

| Precautions to be observed | 312 |

| Importance of avoiding being benighted | 313 |

| Course to be pursued if troops are benighted | 315 |

| An early decision to be arrived at as to intended course of action when night approaches | 315 |

| Guns to be sent on | 316 |

| Examples of troops being benighted | 317 |

| Troops on the move at night | 318 |

| Sir W. Lockhart's maxims | 320 |

| Advantages which experienced troops enjoy in this class of warfare | 320 |

| Danger of even small ravines unless the heights are held | 321 |

| Value of counter-attack when troops get into difficulties | 322 |

| Examples of catching the enemy in ravines | 322 |

| General question of rear guards and retirements | 324 |

| Persistency of hill men in pursuit | 325 |

| The fact that the retirement is generally down hill tells against the regulars | 326 |

| Advisability of a sudden start and rapid movement at first when retiring | 327 |

| Changing a movement of advance into one of retirement | 328 |

| Details of retirement operations | 329 |

| Withdrawal of picquets | 329 |

| Picquets covering each other's retirements | 330 |

| Importance of parties nearest the enemy getting timely notice of intended retirement | 332 |

| Direction to be followed by retiring picquets | 332 |

| Pursuit often checked completely if enemy is roughly handled at the start | 333 |

| Value of counter-attacks when in retreat | 334 |

| Ravines to be avoided, and junctions of these with valleys to be specially guarded | 335 |

| Men to be sent on ahead to find the route in unknown country | 335 |

| Pace of column to be regulated by that of rear guard | 336 |

| The theory of rear guard duties in hill warfare | 336 |

| Position of baggage in retreats | 338 |

| Remarks on operations in forest-clad hills | 339 |

| Flankers in such terrain | 340 |

| Stockades | 341 |

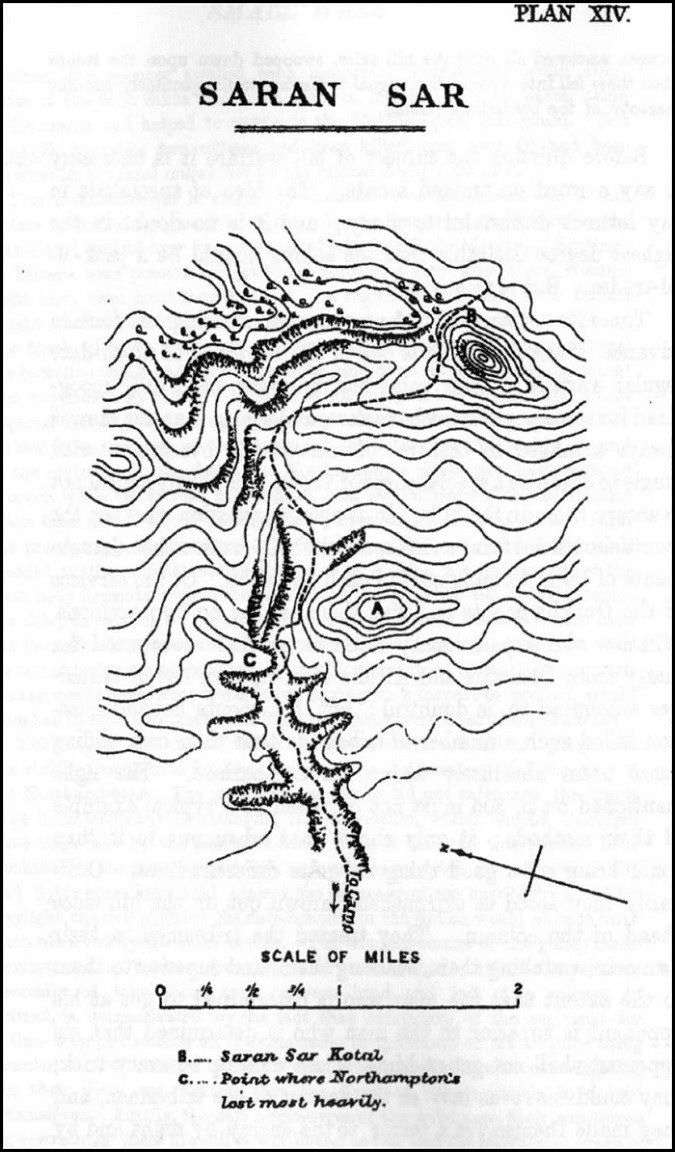

| The first reconnaissance to Saran Sar in Tirah as an example of hill warfare | 342 |

| Scouts | 345 |

| Outposts | 346 |

| Conclusion | 346 |

| CHAPTER XX. Bush warfare. |

|

| Comparison between the general features of bush warfare and of hill warfare | 348 |

| The question of scouts | 352 |

| Special infantry organization necessary | 353 |

| Sectional organization in Ashanti | 354 |

| Tendency of the enemy to attack flanks and rear | 354 |

| Flanking parties | 355 |

| This leads to a kind of square formation being very generally adopted | 355 |

| Its employment in Dahomey | 355 |

| Example of Amoaful | 357 |

| Advantages of this formation in bush fighting | 358 |

| Baggage and supply train | 359 |

| Arrangement of marches in the bush | 359 |

| Action of troops when fired upon | 360 |

| Small columns in the bush | 362 |

| Remarks on operations in a hilly country covered with jungle | 362 |

| Attack of stockades | 362 |

| Movement through very thick jungle | 364 |

| Guides | 365 |

| Difficulty of following up success in the bush, and consequence of this | 365 |

| Danger of dividing force in such country | 367 |

| How to avoid enemy's ambuscades. Impossibility of doing so in some theatres of war | 368 |

| Sir F. Roberts's instructions for dealing with ambuscades in Burma | 368 |

| Retreats in the bush | 369 |

| Heavy expenditure of ammunition | 370 |

| Searching the bush with volleys | 371 |

| Firing the bush | 372 |

| Conclusion | 373 |

| CHAPTER XXI. Infantry tactics. |

|

| Scope of this chapter | 374 |

| Object of normal infantry fighting formation | 374 |

| Reasons why this is not altogether applicable to small wars | 375 |

| Deep formation unusual in attack | 375 |

| Reasons | 375 |

| Proportion of supports and reserves can generally be reduced | 379 |

| Attacks on hill positions | 377 |

| British and French methods | 377 |

| Reserving fire in attack | 378 |

| Formation at Tel-el-Kebir | 379 |

| Attack on the Atbara zeriba | 379 |

| Tendency to draw supports and reserves forward to extend the firing line | 381 |

| General Skobelef's peculiar views | 381 |

| The company frequently made the unit | 382 |

| Attacks should usually be carried out at a deliberate pace | 383 |

| Infantry crossing especially dangerous zones | 384 |

| Compact formations desirable on the defensive | 386 |

| Macdonald's brigade at the battle of Khartum | 387 |

| Infantry opposed to irregular cavalry | 388 |

| Great importance of thorough fire discipline | 388 |

| Magazine rifle in the case of fanatical rushes | 389 |

| The question of volleys and of independent fire | 390 |

| Fire discipline in hill warfare | 392 |

| The conditions which in regular warfare make unrestrained fire at times almost compulsory, do not exist in small wars | 392 |

| Fire discipline on the defensive | 393 |

| Advantage of reserving fire for close quarters | 394 |

| Foreign methods | 395 |

| Remarks on the expenditure of ammunition | 396 |

| Expenditure of ammunition during night attacks | 397 |

| The bayonet of great value, although theoretically the superiority of the regulars should be more marked as regards musketry than in hand to hand fighting | 398 |

| Great effect of bayonet charges | 399 |

| On the defensive the bayonet is less certain | 399 |

| CHAPTER XXII. Cavalry and mounted troops generally. |

|

| Variety in mounted troops employed | 401 |

| Necessity generally of a respectable force of mounted troops in these campaigns | 401 |

| Examples of want of mounted troops | 402 |

| Need of mounted troops for raids | 403 |

| Importance of cavalry shock action | 404 |

| Risk of falling into ambushes or getting into ground where cavalry cannot act | 405 |

| Cavalry able to act effectively on broken ground where it would be useless in regular warfare | 406 |

| Irregular hostile formations militate against effective cavalry charges | 406 |

| Cavalry and horse artillery | 408 |

| Cavalry acting against hostile mounted troops | 409 |

| Importance of discipline and cohesion in such work | 409 |

| Difficulty of meeting a reckless charge of fanatical horsemen | 410 |

| Enemy's horse inclined to use firearms from the saddle | 411 |

| Cavalry if rushed to keep away from the infantry | 412 |

| Cavalry dealing with horsemen who fight on foot | 412 |

| Importance of lance | 414 |

| Skobelef s views on the action of Russian cavalry in the Turkoman campaign | 414 |

| Dismounted action of cavalry | 415 |

| Risk to horse-holders and horses | 415 |

| Combination of mounted and dismounted work suitable in certain conditions | 416 |

| Dismounted action the only possible action of cavalry in very broken ground | 418 |

| Valuable where judiciously used against hostile masses otherwise engaged | 419 |

| Dismounted action in general | 420 |

| Mounted troops, when dismounted, sometimes able to pose as a large force and so deceive the enemy | 420 |

| Mounted troops attacking di-mounted | 420 |

| Mounted rifles and mounted infantry as compared to cavalry | 422 |

| Final remarks on dismounted work | 423 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. Camel corps. |

|

| Camel corps a form of mounted infantry | 425 |

| Object to be able to traverse long distances | 425 |

| Difficult position of camel corps in action | 426 |

| Their helplessness when mounted. How to act if suddenly attacked | 427 |

| The affair of Burnak as illustrating camel operations | 427 |

| Camel corps only suitable in certain theatres of war | 428 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. Artillery tactics. |

|

| Artillery preparation | 429 |

| Guns to push up to close range | 429 |

| Examples | 430 |

| Chief risk run by guns pushed well to the front | 432 |

| Massing of guns unusual and generally unnecessary | 433 |

| Question of dispersion of guns in attack | 433 |

| Dispersion of guns on the defensive | 435 |

| Value of guns on the defensive against fanatical rushes | 430 |

| Comparative powerlessness of guns against mud villages | 437 |

| High explosives | 438 |

| Guns must be light and generally portable | 438 |

| Question of case shot | 439 |

| CHAPTER XXV. Machine guns. |

|

| Uncertainty as to how best to employ them | 440 |

| Their frequent failure till recently | 440 |

| Their value on the defensive | 441 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. The service of security. |

|

| Importance of the service of security | 442 |

| Outposts | 442 |

| Hour at which the enemy is most likely to give trouble | 442 |

| Hostile night attacks unusual | 443 |

| Comparatively small size of force helps enemy in preparing for night attacks | 445 |

| The Boer night attacks | 445 |

| Attacks at dawn very frequent | 446 |

| Annoyance by marauders and small hostile parties at night very common | 448 |

| Principle of outposts | 448 |

| Difference between the system in regular warfare and in small wars | 449 |

| Liability to attack from any side | 450 |

| Outposts generally close in, and not intended to offer serious resistance | 451 |

| Units to be protected generally find their own outposts | 451 |

| Arrangement of outposts, however varies according to nature of enemy | 452 |

| Extent to which the rapid movements of irregular warriors influence outposts | 452 |

| Difficulties of outposts in jungle and bush and in the hills | 454 |

| Tofrek | 455 |

| Picquets by day | 455 |

| Objections to the plan of outposts falling back at once on the main body | 456 |

| Picquets in hill warfare by day | 457 |

| Outposts in the bush by day | 458 |

| Need of even small parties always keeping a look-out in enclosed country | 459 |

| Regular troops to a certain extent at a disadvantage in outpost work in small wars | 460 |

| General remarks on outposts at night | 461 |

| Outposts at night on open ground | 462 |

| Outposts at night in the South African War | 463 |

| Distant picquets at night | 464 |

| Ambuscades as outposts | 466 |

| General Yusuf's system peculiar | 466 |

| Outposts by night in bush warfare | 467 |

| Outposts by night in hill warfare | 467 |

| The system of distant picquets at night not always adopted in hill warfare | 470 |

| Remarks on dealing with snipers at night | 471 |

| Sentries at night | 472 |

| Posting picquets at night | 473 |

| Defensive arrangements in front of outposts at night | 474 |

| Sir B. Blood's plan of using villagers as outposts | 474 |

| Service of security on the march | 474 |

| Effect of hostile tendency to operate against flanks and rear | 475 |

| Service of security when marching in square | 476 |

| Flanking parties and rear guards | 476 |

| Convoys | 477 |

| Importance of keeping columns on the march well closed up | 478 |

| Duties of the advanced guard | 478 |

| Conclusion | 479 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. Night operations. |

|

| Reason why night attacks find so much favour in the present day | 481 |

| General question of their advisability in small wars | 481 |

| Upon the whole the drawbacks decidedly outweigh the advantages | 482 |

| Risk of confusion and panic | 4S3 |

| Objections less serious in the case of attacks on a very small scale | 485 |

| Division of force at night almost always a mistake | 485 |

| Need of careful preparations | 486 |

| Precautions against assailants mistaking each other for the enemy | 486 |

| The bayonet the weapon for night attacks | 487 |

| Examples of successful night attacks on a small scale | 487 |

| Night marches. When especially advantageous | 488 |

| Risk of movement being detected by some accident | 489 |

| Enemy keeps a bad look-out at night | 490 |

| Risk of confusion on the march | 491 |

| Importance of the troops being well disciplined | 492 |

| General conclusions as to night operations | 493 |

| Arrangements for repelling night attacks | 494 |

| Lighting up the ground | 495 |

| Artillery and machine guns in case of night attacks | 495 |

| The question of reserves | 496 |

| Need of strict fire discipline | 496 |

| Bayonet to be used if the enemy penetrates into the lines | 497 |

| Counter-attacks in case of a night attack by the enemy | 497 |

| Conclusion | 498 |

| INDEX. | 499 |

| PLANS. | ||

| Page | ||

| I. | The Ambela Campaign | 49 |

| II. | Communications to Khartum | 70 |

| III. | Fight at Khan Band | 166 |

| IV. | Kirbekan | 166 |

| V. | The Peiwar Kotal | 166 |

| VI. | Action at Charasia | 166 |

| VII. | Affair of Bang Bo | 169 |

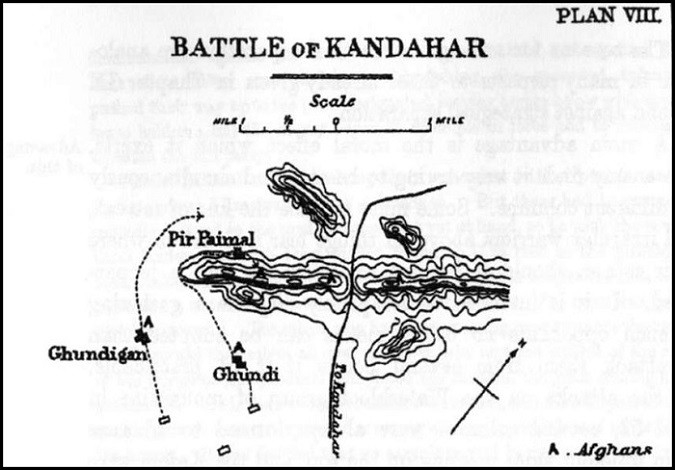

| VIII. | Battle of Kandahar | 176 |

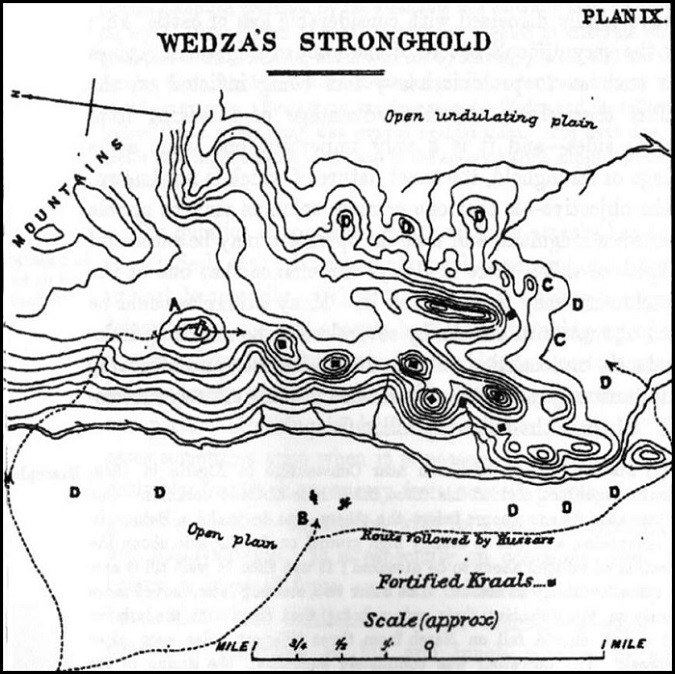

| IX. | Wedza's Stronghold | 176 |

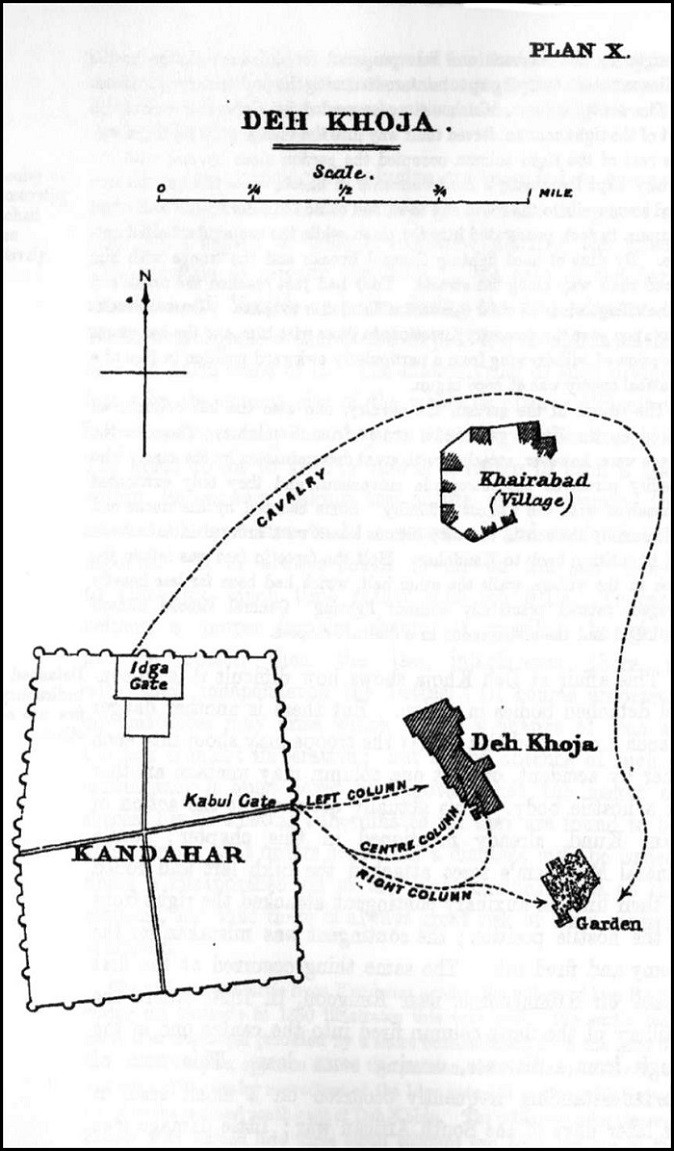

| X. | Deh Khoja | 180 |

| XI. | Affair of Longbatta | 184 |

| XII. | The Zlobani Mountain | 184 |

| XIII. | Action of Kailua | 203 |

| XIV. | Saran Sar | 344 |

| XV. | Macdonald's Brigade at Khartum | 387 |

Chapter I.

Introduction.

| Meaning of the term "Small War." | SMALL WAR is a term which has come largely into use of late years, and which is admittedly somewhat difficult to define. Practically it may be said to include all campaigns other than those where both the opposing sides consist of regular troops. It comprises the expeditions against savages and semi-civilised races by disciplined soldiers, it comprises campaigns undertaken to suppress rebellions and guerilla warfare in all parts of the world where organized armies are struggling against opponents who will not meet them in the open field, and it thus obviously covers operations very varying in their scope and in their conditions. The expression "small war" has in reality no particular connection with the scale on which any campaign may be carried out; it is simply used to denote, in default of a better, operations of regular armies against irregular, or comparatively speaking irregular, forces. For instance, the struggle in 1894-95 between Japan and China might, although very large forces were placed in the field on both sides, from the purely military point of view almost be described as a small war; for the operations on land were conducted between a highly trained, armed, organized, and disciplined army on one side, and by forces on the other side which, though numerically formidable, could not possibly be described as regular |

--21--

troops in the proper sense of the word. Small wars include the partisan warfare which usually arises when trained soldiers are employed in the quelling of sedition and of insurrections in civilised countries; they include campaigns of conquest when a Great Power adds the territory of barbarous races to its possessions; and they include punitive expeditions against tribes bordering upon distant colonies. The suppression of the Indian Mutiny and the Anglo-French campaign on the Peiho, the British operations against the Egyptian army in 1882, and the desultory warfare of the United States troops against the nomad Red Indians, the Spanish invasion of Morocco in 1859, and the pacification of Upper Burma, can all alike be classed under the category of small wars. Whenever a regular army finds itself engaged upon hostilities against irregular forces, or forces which in their armament, their organization, and their discipline are palpably inferior to it, the conditions of the campaign become distinct from the conditions of modern regular warfare, and it is with hostilities of this nature that this volume proposes to deal. |

|

| General scope of the work. | Upon the organization of armies for irregular warfare valuable information is to be found in many instructive military works, official and non-official. The peculiar arrangements as to transport, the system of supply, the lines of communications, all these subjects are dealt with exhaustively and in detail. In this volume, therefore, questions of organization will be as far as possible avoided. It is intended merely to give a sketch of the principles and practice of small wars as regards strategy and tactics, and of the broad rules which govern the conduct of operations in hostilities against adversaries of whom modern works on the military art seldom take account. |

| Arrangement adopted. | The earlier chapters will deal with the general principles of strategy, the later chapters with tactics. In a treatise which necessarily covers a great deal of ground it is difficult |

--22--

to avoid a certain amount of repetition, but it has been thought better to incur this than to interpolate constant references from one part of the book to the other. The subject will throughout be discussed merely from the point of view of the regular troops. The forces opposing these, whether guerillas, savages, or quasi-organized armies, will be regarded as the enemy. A comparison will be to a certain extent established between the conduct of campaigns of this special character and the accepted principles of strategy and tactics. The teachings of great masters of the art of war, and the experience gained from campaigns of modern date in America and on the continent of Europe, have established certain principles and precedents which form the groundwork of the system of regular warfare of to-day. Certain rules of conduct exist which are universally accepted. Strategy and tactics alike are in great campaigns governed, in most respects, by a code from which it is perilous to depart. But the conditions of small wars are so diversified, the enemy's mode of fighting is often so peculiar, and the theatres of operations present such singular features, that irregular warfare must generally be carried out on a method totally different from the stereotyped system. The art of war, as generally understood, must be modified to suit the circumstances of each particular case. The conduct of small wars is in fact in certain respects an art by itself, diverging widely from what is adapted to the conditions of regular warfare, but not so widely that there are not in all its branches points which permit comparisons to be established. |

|

| General treatment. | In dealing with tactical questions arising in small wars the more recent campaigns are chiefly taken into consideration, owing to the advances in the science of manufacturing war material. Tactics necessarily depend largely on armament, and while the weapons which regular troops take into the field have vastly improved in the last 40 years, it must be |

--23--

remembered that the arms of the enemy have also improved. Even savages, who a few years ago would have defended themselves with bows and arrows, are often found now-a-days with breechloading rifles - the constant smuggling of arms into their territories, which the various Powers concerned seem wholly unable to suppress, promises that small wars of the future may involve very difficult operations. On the other hand the strategical problems presented by operations of this nature have not altered to at all the same extent. Therefore there is much belonging to this branch of the military art still to be learnt from campaigns dating as far back as the conquest of Algeria and as the terrible Indian struggle of 1857-58. And the great principle which regular troops must always act upon in small wars - that of overawing the enemy by bold initiative and by resolute action whether on the battlefield or as part of the general plan of campaign - can be learnt from the military history of early times just as well as it can be learnt from the more voluminously chronicled struggles of the present epoch. |

--24--

Chapter II.

Causes of small wars as affecting their conditions.

The various kinds of adversaries met with.

Classes into which these campaigns may be divided. |

Small wars may broadly be divided into three classes - campaigns of conquest or annexation, campaigns for the suppression of insurrections or lawlessness or for the settlement of conquered or annexed territory, and campaigns undertaken to wipe out an insult, to avenge a wrong, or to overthrow a dangerous enemy. Each class of campaign will generally be found to have certain characteristics affecting the whole course of the military operations which it involves. |

Campaigns of conquest and annexation and their characteristics. |

Campaigns of conquest or annexation are of necessity directed against enemies on foreign soil, they mean external not internal war, and they will generally be directed against foemen under control of some potentate or chief. Few countries are so barbarous as not to have some form of government and some sort of military system. So it comes about that campaigns of conquest and annexation mean for the most part campaigns against forces which, however irregular they may be in their composition, are nevertheless tangible and defined. Glancing back over the small wars of the century the truth of this is manifest. |

Examples. |

The conquest of Scinde and the Punjab involved hostilities with military forces of some organization and of undoubted fighting capacity. The French expedition to Algeria overthrew a despotic military power. The Russians in their gradual extension of territory beyond the Caspian have often had to deal with armies - ill armed and organized, of course, but nevertheless armies. To oppose the annexation of his dominions, King Thebaw of Burma had collected bodies of troops having at least a semblance of system and cohesion, although they showed but little |

--25--

fight. The regular troops detailed for such campaigns enjoy the obvious advantage of knowing whom they are fighting with; they have a distinct task to perform, and skilful leadership, backed by sufficient force, should ensure a speedy termination of the conflict. |

|

The suppression of insurrections and lawlessness, and its features. |

But campaigns for the subjugation of insurrections, for the repression of lawlessness, or for the pacification of territories conquered or annexed stand on a very different footing. They are necessarily internal not external campaigns. They involve struggles against guerillas and banditti. The regular army has to cope not with determinate but with indeterminate forces. The crushing of a populace in arms and the stamping out of widespread disaffection by military methods, is a harassing form of warfare even in a civilised country with a settled social system; in remote regions peopled by half-civilized races or wholly savage tribes, such campaigns are most difficult to bring to a satisfactory conclusion, and are always most trying to the troops. |

This a frequent sequel to conquest and annexation. |

It should be noted that campaigns of conquest, and annexation not infrequently pass through two distinct stages. In the first stage the forces of civilization overthrow the armies and levies which the rulers and chieftains in the invaded country gather for its defence, a few engagements generally sufficing for this; in the second stage organized resistance has ceased, and is replaced by the war of ambushes and surprises, of murdered stragglers and of stern reprisals. The French conquest of Algeria is a remarkable illustration of this. To crush the armies of the Dey and to wrest the pirate stronghold which had been so long a scourge of neighbouring seas from his grasp, proved easy of accomplishment; but it took years and years of desultory warfare to establish French rule firmly in the vast regions which had been won. The same was the case in Upper Burma; the huge country was nominally annexed, practically without a struggle, but several years of typical guerilla warfare followed before British power was |

--26--

thoroughly consolidated in the great province which had been added to the Indian Empire. |

|

Examples. |

Insurrections and revolts in districts difficult of access where communications are bad and information cannot readily be obtained involve most troublesome military operations. In Europe the Carlist wars and early wars of Balkan liberation are examples of this. In the United States, the periodical risings and raids of the Red Indians led to protracted indecisive hostilities of many years' duration. The Kaffir and Matabili rebellions in South Africa have always proved most difficult to suppress. The case of the Indian Mutiny is somewhat different at least in its early stages for here the rebels owing to the peculiar circumstances of the case were in a position to put armies in the field, and this led to field operations of most definite and stirring character; but, as the supremacy of British military power in India became re-established, and as the organized mutineer forces melted away, the campaign degenerated in many localities into purely guerilla warfare, which took months to bring to a conclusion. As a general rule the quelling of rebellion in distant colonies means protracted, thankless, invertebrate war. |

Campaigns to wipe out an insult or avenge a wrong. |

Campaigns of the third class have characteristics analogous to the conditions ordinarily governing wars of conquest and of annexation. Hostilities entered upon to punish an insult or to chastise a people who have inflicted some injury, will generally be on foreign soil. The destruction of a formidable alien military power will necessarily involve external war. Under this heading, moreover, may be included expeditions undertaken for some ulterior political purpose, or to establish order in some foreign land - wars of expediency, in fact. Campaigns of this class when they do not (as is so frequently the case) develop into campaigns of conquest, differ from them chiefly in that the defeat of the enemy need not be so complete and crushing to attain the objects sought for. |

--27--

Examples. |

The Abyssinian expedition of 1868 is a typical example of a campaign to avenge a wrong; it was undertaken to compel the release of prisoners seized by King Theodore. The China War of 1860, and the Spanish invasion of Morocco in 1859, were of the same nature. The Ashanti imbroglio of 1874 and the French operations against the Hovas in 1883 and the following year may be similarly classed. Most of the punitive expeditions on the Indian frontier may be included in this category; but many of these latter have resulted in annexation of the offending district, and the French campaigns in Annam in 1861 and recently in Dahomey ended in like fashion. |

Campaigns for the overthrow of a dangerous power. |

Wars entered upon to overthrow a menacing military power likewise often terminate in annexation. The Zulu war was a campaign of this nature - the disciplined armies of Ketchwayo were a standing danger to Natal, and the coming of the Zulu power was indispensable for the peace of South Africa; the war, however, ended in the incorporation of the kingdom in the British Empire. The Russian expeditions against the Tekke Turkomans were partly punitive; but they were undertaken mainly to suppress this formidable fighting nomad race, and the final campaign became a campaign of conquest. The short and brilliant operations of the French against the Moors in 1844 afford a remarkable instance of a small war having for its object the overthrow of the dangerous forces of a threatening state, and of its complete fulfillment; but in this case there was no subsequent annexation. |

Campaigns of expediency. |

Wars of expediency undertaken for some political purpose, necessarily differ in their conditions from campaigns of conquest, punitive expeditions, or military repression of rebellious disorders. The two Afghan wars, and especially the first, may be included in this category. The Egyptian war of 1882 is another example. Such campaigns are necessarily carried out on foreign soil, but in other respects they may have few features in common. |

--28--

The great variety in the natures of enemy to be dealt with. |

To a certain extent then the origin and cause of a small war gives a clue to the nature of the operations which will follow, quite apart from the plan of campaign which the commander of the regular forces may decide upon. But when conflicts of this nature are in prospect, the strength and the fighting methods of the enemy must always be most carefully considered before any decision as to the form of operations to be adopted is arrived at; the tactics of such opponents differ so greatly in various cases that it is essential that these be taken fully into consideration. The armament of the enemy is also a point of extreme importance. In regular warfare each side knows perfectly well what is to be expected from the adversary, and either adversary is to a certain extent governed by certain rules common to both. But in small wars all manner of opponents are met with, in no two campaigns does the enemy fight in the same fashion, and this divergence of method may be briefly illustrated from various campaigns of the past century. |

Opponents with a form of regular organization. |

Some small wars of late years have been against antagonists with the form and organization of regular troops. The hostile armies have been broken up into battalions, squadrons, and batteries, and in addition to this the weapons of the enemy have been fairly efficient. This was the case in Egypt in 1882, to a certain extent in Tonkin as far as the Chinese were concerned, and also in a measure in the Indian Mutiny. In such struggles the enemy follows as far as he is able the system adopted in regular warfare. In the campaigns above-mentioned, the hostile forces had enjoyed the advantage of possessing instructors with a knowledge of European methods. In cases such as these the warfare will somewhat resemble the struggles between modern armies, and the principles of modern strategy and tactics are largely if not wholly applicable. |

At the outset of the last Afghan war the hostile forces had a form of regular organization; this could, however, |

--29--

|

scarcely claim to be more than a travesty, and the Afghan armament was, moreover, most inferior. The Russians in their campaigns against Khokand and Bokhara had to deal with armies standing on a somewhat similar footing as regards organization and weapons. Somewhat lower in the scale, but still with some pretence to organization and efficient armament, were the Dey of Algiers' troops which confronted the French invasion in 1830. There is, of course, a great variety in the extent to which the hostile forces approximate to regular armies in various small wars; but there is a clear distinction between troops such as Arabi Pasha commanded in 1882, and mere gatherings of savages such as the British and French have at times to cope with in Western Africa. |

| Highly disciplined but badly armed opponents. | The Zulu impis, again, presented totally different characteristics. Here was a well disciplined army with a definite organization of its own, capable of carrying out manoeuvres on the battlefield with order and precision; but the Zulu weapons were those of savages. The Matabili were, organized on the Zulu model, but their system was less perfect. Zulus and Matabili fought in a fashion totally different from the Chinese, the Afghans, and Arabi Pasha's forces, but they were none the less formidable on that account. |

Fanatics. |

The Hadendowa of the Red Sea Littoral, the Afghan Ghazis, and the fanatics who occasionally gave the French such trouble in Algeria, had not the discipline of the Zulu or of the Matabili, nor yet their organization; but they fought on the same lines. Such warriors depend on spears and knives and not on firearms. They are brave and even reckless on the battlefield. Tactics which serve well against forces armed with rifles and supported by artillery, are out of place confronted with such foes as this. Face to face with Sudanese and Zulus old orders of battle, discarded in face of the breech-loader and of shrapnel shell, are resumed again. The hostile tactics are essentially aggressive, and inasmuch as they involve substitution of shock action for |

--30--

fire action, the regular forces are compelled, whether they like it or not, to conform to the savage method of battle. |

|

The Boers. |

In the Boer war of 1881 the British troops had a different sort of enemy to deal with altogether. The Boers were armed with excellent firearms, were educated and were led by men of knowledge and repute, but they at that time had no real organization. They were merely bodies of determined men, acknowledging certain leaders, drawn together to confront a common danger. The Boers presented all the features of rebels in a civilized country except in that they were inured from youth to hardship, and that they were all mounted. As a rule adversaries of this nature prefer guerilla warfare, for which their weapons and their habits especially adapt them, to fighting in the open. The Boers, however, accepted battle readily and worked together in comparatively speaking large bodies even in 1881. The incidents of that campaign, although the later and greater war has rather overshadowed them and deprived them of interest, were very singular, and they afford most useful lessons with regard to the best way of operating against adversaries of this peculiar class. In 1901 and 1902, after the overthrow of the organized Boer armies had driven those still in the field to adopt guerilla tactics, the operations partook of the character of irregular warfare against a daring and well armed enemy gifted with unusual mobility and exceptional cunning. |

Guerillas, civilized and savage. |

The Turks in Montenegro, the Austrians in Bosnia, and the Canadian forces when hunting down Riel, had to deal with well armed and civilized opponents; but these preferred guerilla methods of warfare, and shirked engagements in the open. Organization they had little or none; but in their own fashion they resisted obstinately in spite of this, and the campaigns against them gave the regular troops much trouble. These operations afford good illustrations of guerilla warfare of one kind. Guerilla warfare of a totally different kind is exemplified by the Maori and the Kaffir wars, in which |

--31--

the enemy, deficient in courage and provided with poor weapons, by taking advantage of the cover in districts overgrown with bush and jungle managed to prove most difficult to subdue. To regular troops such antagonists are very troublesome, they shun decisive action and their tactics almost of necessity bring about a protracted, toilsome war. The operations on the North-West Frontier of India in 1897 afford admirable examples of another form of guerilla warfare that against the well armed fanatical cut-throat of the hills, lighting in a terrain peculiarly well adapted to his method of making war. |

|

Armies of savages in the bush. |

Savages dwelling in territories where thick tropical vegetation abounds, do not, however, always rely on this desultory form of war. In Dahomey the French encountered most determined opposition from forces with a certain organization which accepted battle constantly. The Dutch in Achin, where the jungle was in places almost impenetrable, found an enemy ready enough to fight and who fought under skilful guidance. The Ashantis during the campaign of 1871 on several occasions assembled in large bodies; they did not hesitate to risk a general engagement when their leaders thought an opportunity offered. |

Enemies who fight mounted. |

Another and altogether different kind of enemy has been met with at times in Morocco, in Algeria, and in Central Asia. In the Barbary States are to be found excellent horsemen with hardy mounts. The fighting forces of the Arabs, Moors, and Tartars have always largely consisted of irregular cavalry, and the regular troops campaigning in these countries have been exposed to sudden onslaught by great hordes of mounted men. The whole course of operations has been largely influenced by this fact. |

The importance of studying the hostile mode of war. |

Military records prove that in different small* wars the hostile mode of conducting hostilities varies to a surprising extent. Strategy and tactics assume all manner of forms. It is difficult to conceive methods of combat more dissimilar |

--32--

than those employed respectively by the Transkei Kaffirs, by the Zulus, and by the Boers, opponents with whom British troops successively came in conflict within a period of three years and in one single quarter of the African continent. From this striking fact there is to be deduced a most important military lesson. It is that in small wars the habits, the customs, and the mode of action on the battlefield of the enemy should be studied in advance. This is not imperative only on the commander and his staff - all officers should know what nature of opposition they must expect, and should understand how best to overcome it. One of the worst disasters which has befallen British troops of recent years, Isandlwhana, was directly attributable to a total misconception of the tactics of the enemy. The French troubles in Algeria after its conquest were due to a failure to appreciate for many years the class of warfare upon which they were engaged. The reverses in the first Boer war arose from entering upon a campaign without cavalry, the one arm of the service essential to cope with the hostile method of conducting warfare. In great campaigns the opponent's system is understood; he is guided by like precedents, and is governed by the same code; it is only when some great reformer of the art of war springs up that it is otherwise. But each small war presents new features, and these features must if possible be foreseen or the regular troops will assuredly find themselves in difficulties and may meet with grievous misfortune. |

--33--

Chapter III.

The objective in small wars.

Selection of objective in the first place governed by the cause of the campaign. |

The selection of the objective in a small war will usually be governed in the first place by the circumstances which have led up to the campaign. Military operations are always undertaken with some end in view, and are shaped for its achievement. If the conquest of the hostile territory be aimed at, the objective takes a different form from that which it would assume were the expedition dispatched with merely punitive intent. A commander bent on extorting terms from some savage potentate will frame his plans on different lines from the leader sent to crush the military power of a menacing tribe. But in all cases there are in warfare of this nature certain points which will, apart from the cause of the campaign, influence the choice of the objective, and which depend mainly on the class of enemy to be dealt with. |

Cases where the hostile country has a definite form of government. |

The enemy is often represented by a people with comparatively speaking settled institutions, with a central form of government, and with military forces regulated and commanded by a central authority. Monarchical institutions are to be found in many semi-civilized and savage lands, amounting often to forms of despotism which are particularly well calculated to ensure a judicious management of available military forces when at war. The savage Zulu warriors fought in organized armies controlled by the supreme authority of the king. Runjeet Singh was a respected ruler who could dispose, of organized forces completely at his command; the Amir of Bokhara stood on a similar footing during the campaigns which ended in the annexation of his |

--34--

khanate to the Russian Empire. The Ashantis and Dahomeyans were nationalities which although uncivilized were completely dominated by their sovereigns. In cases such as these the objective will generally be clear and well defined. There are armies the overthrow of which will generally bring the head of the hostile state to reason. There are centres of government the capture of which will paralyse the forces of resistance of the country. To a certain extent the destruction of the military forces of the enemy under such conditions almost necessarily involves the fall of the capital, because the military forces gather for the protection of the capital and the fall of the capital follows upon their defeat almost as a matter of course. The conditions approximate to those of regular warfare in the very important particular that from the outset of the campaign a determinate scheme of operations can be contemplated and can be put in force. |

|

The question of the importance of the capital as an objective. |

In great campaigns of modern history it has come to be considered as the usual objective that the capital of the hostile nation should be threatened, and that it should if possible be actually captured. In a civilized country the metropolis is not only the seat of government and of the legislature, but it is also generally the centre of communications and the main emporium of the nation's commerce. Its occupation by an enemy means a complete dislocation of the executive system, it brings about a collapse of trade, and, if the occupation be long continued, it causes financial ruin. But the capitals of countries which become the theatres of small war are rarely of the same importance. In such territories there is little commercial organization, the chief town generally derives its sole importance from being the residence of the sovereign and his council, and its capture by a hostile army is in itself damaging rather to the prestige of the government than injurious to the people at large. |

In the last Afghan war Kabul was occupied early in the campaign, after the overthrow of the troops of Yakoub Khan. But its capture by no |

--35--

means brought about the downfall of the Afghans as a fighting power, on the contrary it proved to be merely the opening engagement of the campaign. The country was in a state of suppressed anarchy, the tribes scarcely acknowledge the Amir to be their King, and when Kabul fell and the government such as it was, ceased to exist, the people generally cared little; but they bitterly resented the insult to their nation and to their faith which the presence of British troops in the heart of the country offered. |

|

But, although the relations of Kabul to the Afghan race maybe taken as typical, there are often exceptions, and cases have often occurred in these wars where the capital of the country has proved the core of its resistance. In the case of a petty chieftain the capital means his stronghold. Sekukuai's and Morosi's mountains are examples of this, and their capture put an immediate end to the campaign in each case. When the object of the war is to extort certain conditions or to exact reparation from some half-civilised or savage potentate, the capture of his capital will generally have the desired effect. It was so in the Chinese war of 1860, when all efforts at negotiation failed till the allied forces were at the gates of Pekin. |

|

When the capital is a place of real importance in the country its capture generally disposes of regular opposition. |

When the capital is really the focus and centre of a State, however barbarous, any approach to organized resistance under the direct control of the head of the State, will almost always cease when the capital falls; but it does not by any means follow that the conflict is at an end. The capture of Algiers in 1830 closed the campaign as one against armies including troops of all arms; it proved, however, to be only the prelude to years of desultory warfare. It was the same in Dahomey, where the fighting power of Benauzin's forces was utterly broken in trying to bar the advance of the invaders to Abomey, but there were troublesome hostilities with guerillas subsequently. On the other hand, the fighting after the occupation of Ulundi in the Zulu war and of Buluwayo in the Matabili campaign, was only of a desultory description. The amount of resistance offered to the regular troops after they have overthrown the more or less organized forces of the |

--36--

enemy and seized the chief town varies in different cases. But the French experiences in Algeria, and the British experiences in Afghanistan, show that these irregular, protracted, indefinite operations offer often far greater difficulties to the regular armies than the attainment of the original military objective. |

|

The great advantage of having a clear and well-defined objective. |

The advantage of having a well defined objective even for a time can, however, scarcely be over-rated, and the Central Asian campaigns of Russia illustrate this vividly. Turkestan was territory inhabited largely by nomads, but its rolling plains and steppes were studded with historic cities many of which had been for ages the marts of oriental commerce. The invaders went to work with marked deliberation. They compassed the downfall of the khanates by gradually absorbing these cities, capturing them in many cases by very brilliant feats of arms. The conquests were not achieved by any display of mighty force, the actual Russian armies in these operations were rarely large, but the objectives were always clear and determinate; the capture of one city was generally held sufficient for a year, but it thereupon became a Russian city. The troops had always an unmistakable goal in front of them, they went deliberately to work to attain that goal, and when it was attained they rested on their laurels till ready for another coup. Such is the military history of the conquest of Central Asia. It is a record of war in which desultory operations were throughout conspicuous by their absence. Such conditions are, however, very seldom found in small wars; important towns and centres of trade, moreover, are not the sole conditions offering distinct objectives. |

Sometimes the circumstances of the case will cause the enemy to muster in full strength, and will permit of a decisive victory being gained which concludes the war, and it is most fortunate when the operations take this form. The enormous importance of moral effect in these campaigns will be dealt with in a later chapter, suffice it to say here |

--37--

that it is a factor which enters into all their phases; a defeat inflicted upon a large force of irregular warriors terrifies not only those engaged, but also all their kind. It is the difficulty of bringing the foe to action which, as a rule, forms the most unpleasant characteristic of these wars; but when such opponents can be thoroughly beaten in the open field at the commencement of hostilities, their powers of further serious resistance often cease. And so, when by force of circumstances the enemy is compelled to accept battle to defend some point of great importance to him or to safeguard some venerated shrine, thus offering a well-defined objective, the regular troops greatly benefit. Many examples of this might be quoted. Denghil Tepe, for instance, became the stronghold in which practically the whole military power of the Tekke Turkomans concentrated itself in 1879 and 1880, although the Turkomans are, in the main, a nomad race; the Russians failed in their first campaign through mismanagement, but the objective never was in doubt, and in their second venture the formidable nomad race, which might have taken years to subdue, was crushed for good and all when the fortress fell. The experience of the French in Annam in 1861 is another case in point. They had formed a small settlement at Saigon, and this the Annamese, profiting by the inability of the French to detach troops thither during the China war, blockaded in great force, forming a regular entrenched camp close by. Thus it came about that when the French were at last able to land a large force at Saigon, they found a formidable hostile army before them in a highly defensible position, which was just what they wanted. By bold and skilful dispositions they signally defeated the Annamese drawn up to meet them, and the effect of the blow was so great that they were able to overrun the country afterwards almost unhindered. |

|

Tirah, a peculiar case. |

The Tirah campaign of 1897 affords a singular example of the advantages of a definite objective. It was the just boast of the Afridis and Orukzais that the remarkable upland |

--38--

valleys which constitute their summer home, and which were practically unknown to the British, had defied the efforts of all invaders. The duty of Sir W. Lockhart's army, therefore, was to overrun these valleys, and to prove to the formidable tribesmen that whatever might have been their experience in the past, they had now to do with a foe capable of bursting through the great mountain barriers in which they put their trust, and of violating the integrity of territory which they believe to be incapable of access by organized troops. The army performed its task of penetrating into Tirah, and of leaving its mark in the usual manner by the demolition of buildings and destruction of crops. Nor did its subsequent retirement, harassed by the mountaineers in defiles where they could act to the very best advantage, appreciably detract from the success of the operation as a whole. For the enemy had learnt that an Anglo-Indian army could force its way into these fastnesses, could seize their crops, destroy their defences, burn their villages, and could, after making its presence felt in every ravine and nook, get out again; and that settled the matter. The conditions here were peculiar, but they illustrate well the broad principle that in warfare of this nature it is half the battle to have a distinct task to perform. |

|

Objective when the purpose of hostilities is the overthrow of a dangerous military power. |