Ingersoll, Royal R. Cruising in the Old Navy. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Foundation, 1974.

The Navy Department Library

Cruising in the Old Navy

Naval Historical Foundation Publication

Washington, DC

1974

Foreword

"Cruising in the Old Navy" is the story of Rear Admiral, then Lieutenant, R. R. Ingersoll's cruise of 1887-1890 in the screw sloop Enterprise, Commander B. H. McCalla commanding. It is an excerpt from Admiral Ingersoll's much longer manuscript "The Story of my Life and Times", which his son Admiral R. E. Ingersoll has generously donated to the Foundation.

The longhand manuscript is a fascinating, often witty account of Admiral Ingersoll's experiences during his long naval career, spanning more than four decades 1865-1909, and filling more than 1,200 handwritten pages. While "Cruising in the Old Navy" is only a short excerpt, we feel that it gives the flavor of the longer work, recreating the life aboard a cruising man-of-war of the Old Navy. On this cruise Enterprise had a "roving commission", and was therefore free to set her own itinerary, while she also relied on the intelligence and resourcefulness of her own officers in meeting unexpected situations as they arose.

Written in Admiral Ingersoll's lively, acute style, "The Story of my Life and Times" should appeal alike to the naval historian, traveller, and plain nostalgic reader. The original manuscript of course has been placed in the Library of Congress along with the Foundation's other manuscript collections, while typescript copies of the manuscript also are available at the Library of Congress, the Truxtun-Decatur Naval Museum, and the Foundation office in the Navy Yard, Washington.

All Photos Are Official U. S. Navy Photos

--i--

--ii--

Cruising in the Old Navy

by Rear Admiral R. R. Ingersoll

1887

About the middle of the summer I learned that Commander B. H. McCalla wished me to go as Executive Officer of the steam corvette Enterprise which he was to command. A few days later Commander McCalla came down to Annapolis as the guest of Commander Sampson, and I improved the occasion to call on him. McCalla was Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Navigation at the Navy Department and a personal friend of Admiral John G. Walker, Chief of that Bureau--a power in the Department in those days. I was informed that the Enterprise would cruise in European waters and that I would get orders to that ship.

We packed our belongings, stored them, and went home to La Porte to make necessary arrangements prior to my departure for a long period of sea duty. It meant three years away from home and family in those days. It was hard enough for me to leave my dear wife, but it was doubly hard this time to leave, also, my four-year old son at a most interesting period of his life. A suite of rooms was arranged for my wife and boy, as my wife very sensibly decided not to live at her father's home, although urged by the grandparents to do so. She wished her small son to be mainly under her own control.

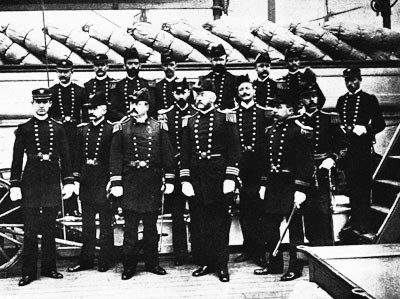

Orders came in September, and October 1st after a sorrowful parting from my little family I journeyed to the Navy Yard at New York and reported for duty on the Enterprise. She had no officers or crew or equipment, except standing rigging, engines, boilers and other permanent fixtures. Commander McCalla commissioned the ship on the 3rd of October, as I remember, and left me in charge to fit her out. About half a crew had been assembled on the old receiving ship Vermont, and as soon as messing gear was taken on board the men available came on board permanently. A full complement of officers soon reported. They were Lieut. D. D. V. Stuart, Navigator; Lieutenants Samuel Lemly, Richard Mulligan and H. C. Wakenshaw; Ensigns Percival J. Werlich and George W. Kline; Chief Engineer James Entwistle; Paymaster John A. Mudd; Surgeon Cumberland G. Herndon;

--1--

and Captain of Marines. Asst. Engineer F. M. Bennett was the only junior officer besides four midshipmen.

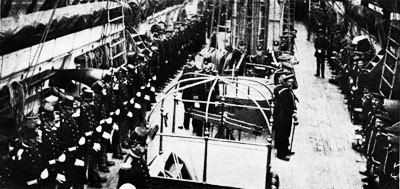

Berth deck cooks, USS Enterprise, circa 1887-1890.

In about three weeks the crew was completed and quartered on board. Only a small number, comparatively, were native-born Americans or, in fact, citizens by naturalization. There were some continued service men who were available for Petty Officers, but the crew as a whole was a conglomeration of various nationalities. Of the men who had been to sea and claimed to be seamen, for the most part they had been recruited from the drifting element found in large seaports like New York, who enlisted in the naval service for the sake of the higher pay than could be had in the merchant marine of foreign nations, for the United States had no merchant marine worth considering at that time. With the exception of the few American continued service men, and some of the fire room force, there was no patriotic inspiration in the service by the great majority of the crew. That class was in the service for what they could get out of it, and the flag and the country meant little to them. Getting the stores, sails, running rigging and ammunition on board kept all hands very busy for weeks, and there seemed to be no very great hurry about getting the ship ready for sea. Around Thanksgiving time I managed to make a flying visit home to see my family again, which was a very great joy, and I found my dear wife and our dear boy very comfortably located. And so the days passed until Christmas, and while we were all fitted out, no move was in sight.

Three days before Christmas word was received, and the papers were full of the fact, that a great log raft, constructed in a cigar shape of thousands of pine logs, which was being towed from Nova Scotia

--2--

to New York, had broken adrift from the towing vessels off the Nantucket Shoals and had been abandoned at sea, due to stress of weather. Recognizing that the log raft, if it held together, was a menace to navigation and in the track of steamers to and from New York, the Navy Department ordered the Enterprise to proceed at once to the locality where the raft was abandoned, make search for it, and if possible tow it into port. Steam was raised at once, and heavy coils of wire cables as well as a manila cable were hurriedly dumped on our decks, and just at dark the ship proceeded up the East River through Hell Gate on her way to Long Island Sound and out to sea. The weather was bitter cold and a heavy gale was blowing, which shifted to the northwest during the night and promised a heavy sea after passing Block Island. By noon of the next day the ship was bowling along before the wind and sea south of Martha's Vineyard and rolling rails under, shipping a sea now and then over the quarter. Many of the air ports leaked, and altogether it was very uncomfortable for everybody. The location of the abandonment of the raft was reached by nightfall, but naturally no trace of the obstacle was found as it had been subject to the drift and also the pounding of heavy seas for three days. The next day the gale broke and the sea went down, so a proper search could be made. Soon a log adrift was seen here and there, and floating logs were before long seen in all directions, covering a space of twenty to thirty miles in each direction. No mass of logs was seen, and it was evident that the raft had broken up. The single logs were not dangerous to navigation unless a ship should pick one up with her propeller--an event not probable because the bow wave would doubtless throw the log away from the ship's side if one was hit. After running several traverses with the line of drift and at right angles to it, it was decided that nothing could be done except to return to port and report, in order that ships could be warned of the drifting logs and avoid them or the locality. All the next day and until Christmas Eve was taken up in steaming for the entrance to Long Island Sound. The Navigator had to give up his duty on account of his eyes, and that duty devolved upon me in addition to my regular duties as Executive. All that night we steamed at full speed down the Sound to New York, the night being clear but very cold, and we arrived at the Navy Yard about four o'clock in the morning. I had not left the deck except to get food for over forty-eight hours, so after the ship had been secured at her berth at the Cob Dock all hands were ready to turn in for a good sleep, in spite of the fact that it was Christmas Day.

The Enterprise was a wooden sloop of war of about 1400 tons displacement, and while she was supposed to have been refitted she

--3--

had no modern equipment. A steam steering gear, a steam anchor engine, a ventilating system for the berth deck, a forward navigating bridge and a pilot house on that bridge, as well as other minor installations, were put in while the ship was outfitting at the Navy Yard, much of the work being done by our own force of mechanics, who were very competent men and were Americans. The discipline of the crew was only average, in spite of measures adopted to improve it. In those days men drank to excess whenever given leave, and remaining absent without leave was a common practice. Deprivation of liberty was the usual punishment.

1888

Finally, in January 1888 we sailed for Boston for some additional equipment, and from Cape Cod to Boston Light encountered a heavy gale with freezing temperature which lasted all one night, and the ship was a mass of ice half way up the fore and main rigging when we finally reached Boston. We went alongside the dock and secured the ship, but the ice covered the hull and rigging during the whole period of our stay at the Boston Navy Yard.

After about ten days the ship finally sailed, bound to Gibraltar by way of the Azores. We were glad, indeed, to make a start, for the long period which had elapsed since the ship was commissioned had not been of benefit to the personnel from a disciplinary point of view. The weather was cold but fair, and after a day's steaming the ship was put under sail alone. It was the hardest kind of work to get the sails and running rigging clear of ice in order to make sail, but it was done in time. With a fair wind all went very well, and in a few days we ran into the Gulf Stream with its warm current and mild air temperature. The ice everywhere disappeared as if by magic. We aired and dried bedding, clothing, and wet canvas, and reveled in the warm climate we had encountered. No particular event happened on the voyage to Fayal, except a heavy squall at night which caught the Officer of the Deck off his guard, for lightning with a light wind and a heavy cloud bank to the northwest did not mean anything to him until, with a hiss and a roar, the wind and rain broke upon the ship, which was under full sail at the time. My stateroom opened upon the quarter-deck, and in a very few minutes I reached the deck and took charge. The helm was put up and the ship headed before the wind. I thought we would lose our light sails and spars before we could get the sail off the ship, but with all hands turned out we managed to get all secure without loss or damage, except the carrying away of the spanker gaff. Lightning in the northwest quarter in winter

--4--

on the Atlantic is almost a sure sign of a nasty squall, and the prudent officer shortens sail in advance in plenty of time to take the brunt of the squall under low canvas. When within a day's steaming of Horta on the Island of Fayal, sail was taken in and steam raised, and the wind having hauled ahead, the ship steamed the rest of the way to port.

The sight of the green hills and mountains of the island was pleasant after the twenty-day voyage, and most welcome were the oranges, grapes and fresh vegetables for our mess. We found the fresh fish very fine, also. The native light wine of the Azores, particularly that made from grapes on the high volcanic Island of Pico, we found very exciting as well as wholesome.

No coal or other stores were taken on board at Horta, and after a pleasant stay of about a week we weighed anchor and steamed among the islands to the eastward, but making no stop. We passed in plain sight of St. Michaels on the largest of the group. The ship steamed the remainder of the voyage to Gibraltar, making sail to assist whenever the wind was fair and sails would draw, and made the run in about a week, anchoring off the Ragged Staff landing near the Naval Station. We received our first mail from home at Gibraltar.

A day or two after our arrival, the Lancaster which had been on the South American Station arrived en route to Ville Franche to become the new flagship on the station, having made the voyage from Rio de Janeiro almost entirely under sail. The ship had been a long time on the way, and her officers and crew were very glad to get into port again.

A short distance from the Enterprise lay at anchor an American brig, the Marie Celeste, showing the usual trim and rig of an American-built vessel--sails neatly furled and rigging apparently intact--and yet this vessel furnished one of the most extraordinary mysteries of the sea. A few days before our arrival she had been picked up as a derelict and towed into port by a passing steamer. She was sighted about 500 miles west of the Straits of Gibraltar with all sail set, coming to and falling off and apparently not under control. The attention of the steamer was attracted to the erratic movements of the brig, and she steamed close to for an observation. Not a soul was in sight on board the brig, and repeated hailing failed to bring anyone in sight on board. The steamer lowered a boat and sent a boarding party alongside. A search revealed that the brig had been deserted by officers and crew and all the boats were missing. The quarter boats' falls were hanging down just clear of the water. There was no evidence of a mutiny of the crew and no signs of bloodshed

--5--

or a struggle. The log revealed that the Captain's wife and little daughter were passengers on board, and that the brig was bound to Las Palmas of the Canary Islands from Boston. The hatches had not been started, and the men's chests were undisturbed in the forecastle. A sewing machine in the cabin had an unfinished piece of work, a child's garment, still on the sewing machine stand with a seam unfinished, indicating a hasty abandonment due to some sudden cause or impulse. The log had been written up to noon of the preceding day, and the record showed favorable winds and weather. There was no record of storms or sudden squalls. The cabins had not been ransacked or plundered, and nothing was found to furnish a motive or reason for suddenly abandoning the ship. After furling the sails, and with a few men on board as a crew, she was taken in tow and brought to Gibraltar, where an admiralty court sought a solution of the mystery, but without result. From that day to this no trace whatsoever has been found of the personnel of that ship, and no reason had been found for abandoning her in fair weather. The African Coast was about 400 miles distant, and with the boats the officers and men should have had no difficulty in making the land, and vessels are every day making for the entrance to Gibraltar Straits. Some sudden panic or other controlling reason caused that ship's company to hastily take to the boats, but what it was is a mystery and thus far has remained a mystery.

After coaling, the Enterprise ran over to Tangier and remained in that harbor a few days. Then we started on a cruise along the northern coast of Algeria, touching first at a small port west of Oran, where behind a small breakwater a couple of steamers were loading iron ore. Arriving at Oran, which has a fine, artificial harbor protected by a breakwater, our ship was assigned to a berth in one of the basins and tied up to one of the concrete piers. We found Oran to be practically a French city with but little to give it an Oriental character except the many types of natives thronging the streets. The products of the country furnished an extensive commerce with France and also with Spain. Much tobacco was grown as well as grain, and there were extensive vineyards. The tobacco all went to France. We found the cigarettes much the best produced anywhere in Europe, although they were not equal to the Egyptian or Turkish output according to some authorities. The costumes of the various races of Arabs and other native tribes were interesting. There was a typical French café chantant as well as numerous cafés and restaurants, while the architecture of the blocks of buildings was typical French of the southern provinces. Two Captains of Tops sneaked ashore with the catamaran, taking with them a colored landsman

--6--

whose duty it was to clean the ship's side with that craft. The gendarmes returned the men in due time, rewards for their arrest having been offered, and the catamaran was picked up by the market boat the morning after it had been stolen, where it had been abandoned at the landing.

With a fair wind and sea, it required only a night's run to Algiers, where we were assigned a prominent berth just inside the northern breakwater, and from our position we had a clear and comprehensive view of the interesting and historical city. In the foreground along the harbor front was an extensive promenade with blocks of buildings in French style, while in the background was the old, native city with its narrow streets and white, flat-topped houses that had not experienced a change for very many years, with here and there a minaret of a mosque. The old Kasbah or palace of the Deys of Algiers stood out prominently to the north of the harbor, practically in perfect condition. To the south of the city and bordering the Bay we saw the extensive and beautiful suburb of Mustapha Superieur, with hotels and private residences of the foreign population. Here were parks and drives with fine semitropical trees in great abundance. Algiers is famed as a winter resort, not only for the French but for tourists and winter residents of other nationalities, among them many Americans.

My work on board kept me busy, but I had an occasional stroll on shore, afternoon or evening, and I thoroughly enjoyed wandering about the old city, viewing the native shops, or in the French part of the city taking in the sights and novelties of the cafés and restaurants. The season at Algiers was drawing to a close in March, the month of the year we were there, and the tourists were going to France in large numbers by every steamer. After a pleasant sojourn of a week at the metropolis of French North Africa, we steamed along the coast to the eastward and just touched at Bona long enough to exchange calls with the officials, the town being just a shipping point and on the railway to the interior. Then we went on to Philippeville, from which point travelers take a train to the famous old town of Constantine, and then on to Biskra on the edge of the Sahara Desert. We remained one day only, however, and then bore away to the northward, with Ville Franche as our destination, and where we arrived in two days and moored to one of the buoys in the harbor.

The Lancaster was in port, and the Commander in Chief inspected the Enterprise. Spring on the Riviera is a very pleasant season, but the crowds who flock there for the winter find April and May a little too warm and move northerly to Switzerland, Germany or to Northern

--7--

France. Those who were making a first visit to this part of the world found it most interesting, and particularly Monaco and Monte Carlo were very alluring. For myself, having been at Ville Franche, Nice and Monaco very many times on previous cruises, it was an old story; anyway, my duties kept me busy on board the greater part of the time, and I only left the ship when I felt the need of a walk over the roads for exercise.

Our Commanding Officer was informed that it was the intention of the Flag Officer to send the Enterprise on an extended northern cruise, including the North Sea and the Baltic, and that he could prepare his own itinerary if he wished to do so. The Commanding Officer summoned me to the cabin and instructed me to submit a list of ports to visit, reasoning, I suppose, that as an old time cruiser in European waters I would know which ports offered the most in the way of attractions. Accordingly, several of us in the wardroom put our heads together and outlined a cruise to ports that few ships on the station had ever had an opportunity to visit. The list as I now remember was as follows and, with minor changes as to length of stay, was closely followed. We asked to go to Gibraltar, Lisbon, Oporto, Coruna, Ferrol, Southampton, Hull, Newcastle, Christiania, Copenhagen, Cronstadt, St. Petersburg, Stockholm, Danzig, Stettin, Elsinore, Leith, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Havre, Rouen, Bordeaux, Lisbon, Gibraltar, Tangier, Malaga, and back to Nice or Ville Franche, the cruise to take about nine months, or until February 1889. It was the most liberal and comprehensive cruise that could be made, unlimited as to time or fixed dates of arrival at or departure from ports.

--8--

It did not take the ship long to get ready, and in a few days after receipt of orders for the roving cruise outlined above we sailed for Gibraltar, where five days later we arrived and coaled. We were always glad of a day or two at Gibraltar at any time. Being a free port, mess stores, cigars and English goods, such as underwear, were to be had of excellent quality and at reasonable prices. During this visit the Commander and several officers were invited to be present at an inspection of the fortress batteries, and practice firing at moving sea targets by the gunners, and particularly to witness the firing of an 80-ton gun which had recently arrived from England and had been mounted for test. All these tests were very interesting to us, and we made the most of the opportunity. The firing of the land batteries at floating sea targets towed by gunboats was very good and the firing of the big, 80-ton gun using service charges and projectiles very impressive. We made full notes of all that we saw. The Captain did not care to call at Lisbon especially as a moderate gale was blowing, so we kept on and anchored off the mouth of the Douro River on which Oporto, the second city of Portugal, is situated. On account of a heavy sea on the bar, the pilots advised a wait for more favorable conditions. By the afternoon of the next day we crossed the bar, which did not seem to be a troublesome operation, but the pilots insisted on having a heavy pilot boat towed on each side with lines from the bows of the ship, to assist in steering they said, but we strongly suspect it was for the purpose of exacting a larger fee for pilotage. The ship steered perfectly with the steam gear, and there was no sea of consequence on the bar.

Oporto lies mainly on the north bank of the river, built on a series of low hills, with the business blocks on a lower level along the river which forms the harbor. The south bank opposite the city is less populous and is much higher than the north bank. From the south bank Wellington bombarded Oporto at the beginning of the Peninsular War, and later crossed the river and stormed the city, driving out the French garrison. The Douro River is subject to strong tides for some distance from its mouth. We were assigned a berth on the south bank close to shore, where we moored with anchors and hawsers. We enjoyed a very pleasant stay of a week at Oporto. Our Consul, a Portuguese, was a man of high standing in the community, and his business was that of a wine merchant. Port wine was and is a leading article of export from Oporto. The Consul arranged for many social entertainments and also for an excursion by rail to Braga, a considerable town north of Oporto, on a railway, noted for a remarkable number of religious shrines on a high hill covered with fine oak trees and reached by a small funicular tramway. Rich

--9--

Portuguese who have returned to their home country to enjoy their wealth are settled in Braga in large numbers. The handsome villas were very numerous and were surrounded by fine gardens planted to flowers. There did not seem to be much business going on, and the city seemed to be just a quiet, luxurious resting place for people well-to-do who just wished rest and quiet. We stocked our wine mess with a large quantity of port wine of an excellent quality and low in price, but the officers did not care much for it as a beverage, as it was too sweet and somewhat heady to suit most tastes.

From Oporto we cruised around Cape Finisterre, passing Vigo at the head of the Bay of that name, and entered Coruna Bay on which the historic town of Coruna is situated, and which withstood, until evacuated by the British, an attack by a superior force of French during the Peninsular War. Every school boy has read the poem, "The Burial of Sir John Moore," who died of wounds received during the siege of Coruna. The first lines, as I recall, were--

"We buried him hurriedly at dead of night,

The sod with our bayonets turning."

The morning following our arrival at Coruna we steamed through the narrow entrance which leads to the landlocked harbor of Ferrol, one of the principal Spanish naval stations with docks, workshops and barracks. I did not land at Ferrol, and aside from the usual official visits there was not much communication with the shore. The town did not offer anything of particular interest aside from the Navy Yard. Our stay at Ferrol lasted only three days, and we sailed on our way to the northern countries across the Bay of Biscay, famed for stormy weather and heavy seas. It was springtime, and we had only fair weather across the Bay. We rounded Cape Ushant and stood up the English Channel to Southampton, where we remained at anchor well below the town for about two weeks, enjoying the mild weather which then prevailed. Most of the officers bought English-tailored clothes. The Netley Hospital near the entrance to Southampton Water, as that reach is called, was the medical finishing school for English army surgeons, and our officers were entertained at an official dinner by the Officers' Mess of Netley Hospital. It was a fine dinner with speeches and much wine and many rounds of whiskies and sodas in the great lounge and smoking room after the dinner, where with songs and horseplay the younger officers enjoyed themselves and kept it up until long after midnight. I sneaked away as early as possible, which was when the Captain took his departure, and I thus escaped the greater part of the aftermath of the dinner. I however witnessed one bit of horseplay which was amusing. A tournament

--10--

or joust was held by mounting two lightweights on the shoulders of two heavier men, the lighter men representing knights and the heavy men the horses. For lances, billiard cues with a boxing glove on the end were used. Starting from the ends of the large room with lances poised, at a signal the knights charged, and when they came together there was generally a bad spill, one or the other, and sometimes both of the knights were "unhorsed". No injuries occurred, however, and the participants seemed to enjoy this form of sport immensely.

I had been to Southampton many times on other cruises and I was not a stranger to the city, but except for some necessary purchase I did not go ashore for my duties kept me very busy. We had hoped our next port would be Gravesend for a visit to London, but our Captain preferred to visit less-frequented ports, so we sailed for the North Sea, when ready, and put in at Hull, on the Humber. Few men-of-war call at the port of Hull, but we found it very dull. An interesting experience was the attending of a performance of the light opera of "Erminie", given in the local Opera House at Hull. I was invited to sit in a box with the author of the opera, M. Jacobowski, who criticized the singers and especially the chorus freely. I had seen the opera produced in New York and Brooklyn, with Francis Wilson in a leading role, and I think the English production by what was considered just a stock company was quite as good. Mr. Jacobowski was asked to name, in his opinion, the finest bit in the opera, and he instantly replied the "Good Night Chorus."

A few days at Hull and then on to Newcastle on the River Tyne. We entered the river between two jetties extending out into the North Sea and passed through tiers of shipping, mostly steamers, though there were some coastwise sailing craft, lined up at the docks on each side of the river at North and South Shields, all moored head and stern and extending two or three miles, finally mooring in an upper reach below a high bridge spanning the river at Newcastle. Extensive shipbuilding works were in view on the northerly side of the river at Shields, with many steamers on the ways in various stages of construction. At Newcastle, above the bridge, is situated the great shipbuilding works of Armstrong, Mitchell & Co., the most extensive of private works in the United Kingdom, with a specialty of the building of men-of-war of the largest size and power, not only for the British Government but for other Governments all over the world except such as possessed large works of their own. The Captain and officers were extended the privilege of visiting the Armstrong, Mitchell works, which produced everything built-in or used on battleships of the first class, including hull, armor, guns, ammunition, machinery,

--11--

and equipment of every sort. The opportunity was one not to be missed, and in company with the Captain and other officers an entire day was put in inspecting various processes of construction of all that goes to make a complete battleship. The British battleship Victoria was nearing completion, and in her forward turret were mounted two of the famous 80 -ton guns regarded as the most powerful artillery of that day. This was the ship that later was rammed and sunk by the battleship [Camperdown] in maneuvers in the Eastern Mediterranean, with great loss of life. Admiral Tyron, the Commander in Chief, went down with his ship. Durham, with its magnificent Cathedral, is only about an hour's ride by train from Newcastle and I improved the opportunity to visit the Cathedral City. The visit was most interesting and well worthwhile, and I regarded it as a day well spent.

After loading as much coal as we could stow in our bunkers, and with a deckload as well, for coal was cheap at Newcastle but not of superior quality, we left our anchorage below Newcastle and moved down the river to North Shields. A heavy gale had prevailed the day before and during the night, and it was decided not to go to sea until the advent of better weather. Therefore we moored head and stern to bollards or heavy clusters of piles just above the shore end of the north jetty, with a full view of the entrance between the jetties and the open sea beyond where a heavy sea from the north was running. During the forenoon we made out a steamer, a freighter, of perhaps 2000 tons, heading in for the entrance. She came on, making fairly good weather, but yawing about as if she was not under complete control. When she reached the entrance, or very near to it, something happened to her steering gear probably, and in spite of the efforts made by her crew to prevent it, she piled up on the cement blocks to windward of the south jetty. Here she was exposed to the heavy seas curling around the end of the north jetty, and it was evident she would soon go to pieces. The heavy seas were breaking over her high above her decks, and it looked as if the crew would be lost, for the seas swept the jetty as well. The lifeboat station at South Shields was almost opposite our ship, just across the narrow river, and we saw the launch of the lifeboat, fully manned, as it came shooting out of its shed down the ways to the water. In a very short time it reached the stranded steamer, found a sheltered spot under and inshore of her bows, and, in spite of the heaving of the sea, took off every man and brought them safely ashore. During the day very much damage was done to the steamer. Her upper works and bridge were carried away and the decks swept clear of everything. When the weather moderated, as it did by the next morning, we went to sea and, passing quite near

--12--

the unfortunate steamer, we could see that she had a heavy list as if her holds were full of water and the ship was practically a total loss.

With a fair wind and moderate sea we ran across the North Sea, steering to sight the southern point of Norway, or the Naze, which we made out after a two days' voyage. Steaming up the Skagerrak, we stood on for the entrance to Christiania Fjord. It was the morning of July 4, 1888, and the sky was clear with bright sunshine and balmy air. The Captain as a rule did not employ pilots if the charts showed proper landmarks and other aids to navigation, and as we had good charts of the Fjord to Christiania we entered boldly and enjoyed the fine scenery as it unfolded with the rising of the sun. It was plain sailing as far as the Island of Drobak, about twenty miles below Christiania. The track laid out in a dotted line on the chart led to the eastward of Drobak Island, but a shoal extended off the mainland opposite the island, but did not encroach upon the channel. The west side of the fjord between Drobak Island and the mainland was shown free of all dangers. Therefore the Captain decided to pass to the westward of Drobak Island and changed the course accordingly. We were steaming about ten knots, with absolutely smooth water, and everything seemed lovely. As we rounded the south end of Drobak Island, several fishermen in their boats excitedly waved their hats and shouted something we could not make out. "Ah," said the Captain, "it is the Fourth of July and they are giving us a cheer." I was on the bridge with the Captain and Navigator enjoying the scene, and when we were abreast Drobak we felt a sudden checking of speed, and with a grinding noise the ship ran up on some underwater obstruction and came to a dead stop. The engines were stopped as soon as possible, and the officers looked at each other in amazement. A glance over the side near the bridge showed that we were up on some underwater obstruction that showed about six feet under water as we could plainly make out. We soon discovered by the eddies that the obstruction extended from Drobak Island across to the mainland, where presently we discovered two beacons evidently marking the direction and position of the obstruction, whatever it was. Backing the engine at full speed, with bottled-up steam, failed to budge the ship, and preparations were at once made to carry out anchors astern. The ship did not leak, indicating that the underwater damage, if any, was not serious. In less than an hour a tug with Norwegian officials came alongside, and we learned all about the obstruction on which we were firmly lodged.

We were on the Drobak defense jetty built of rubble stone by the Norwegian Government from Drobak Island to the mainland to prevent the passage of vessels of war to the westward of the island,

--13--

compelling the east channel to be used, and where shore batteries commanded the channel. The jetty was about fifty feet wide on the bottom and about twenty feet wide on the top at ten feet from the surface. Our ship had just plowed a furrow across the top of the jetty, displacing the loose rubble stone. If it had been a solid rock or concrete construction, we would have been seriously damaged. A steamer called the Falcon, with two large pontoons equipped with capstans and tackles, soon arrived from the Norwegian Naval Station of Horten, only a few miles away, in charge of a Lieutenant, who offered assistance. The ship was afloat from near the bridge aft, and her fore body projected beyond the jetty. A bower anchor was planted well astern with a 13 in. hawser attached, and a stream anchor with a kedge backing it were also planted astern. The guns forward of the bridge were moved aft on the quarter-deck, and ammunition, except powder, as well as all other movable weights were moved aft to lighten the ship as much as possible. Stream chains were swept under the forward body and carried to the pontoons on either side. Late in the afternoon, with bottled steam, an attempt was made to get off, backing at full speed, heaving on the stern cables to the stern anchors, the tug pulling and the pontoons lifting, but to no avail. It seemed apparent that further lightening would be necessary, and towards nightfall we commenced to hoist out coal from the forward bunkers, the men working in watches, and discharging the coal into a lighter alongside. About midnight the big steam Ice Breaker arrived from Christiania, sent down by the municipality to assist in floating the ship. We continued to lighten the ship by taking out coal until about fifty tons had been transferred to the lighter. It was decided, after consulting with the Captain of the Ice Breaker, to get all ready for a combined pull at high water, or about two P.M., the 5th of July, the next day after we had landed on the jetty. The Ice Breaker got into position and sent on board the largest hemp hawser I had ever seen, an eighteen-inch hawser laid rope, and yet pliable to handle. When all was ready, the Ice Breaker weighed anchor and started steaming slowly. When the big hawser tautened, at a signal everything that would pull was started--anchor engine, main engine, tug, and pontoons, with the lower rigging manned and the men shaking the shrouds to loosen up. When the Ice Breaker got fairly at work and everything else was working, the ship gave a shudder and slid off into deep water, the crew cheering. The upper deck was a scene of wreck, with guns and stores scattered about and the running rigging adrift. The yards were squared temporarily, and work began to clear up the decks and restore the ship to normal condition. It was far into the night before it was half finished.

--14--

The next morning work was resumed, the coal restowed on board, guns and anchors in place as usual, so by about 4:00 P.M. of July 6th the ship weighed anchor and steamed to Christiania Harbor. The work of lightening the ship and of getting things to rights after we were clear of the jetty was greatly facilitated by the long hours of daylight. At that time of the year and in that latitude the sun set about 10:00 P.M. and rose at 2:00 A.M., while during the intervening four hours the bright twilight permitted the reading of a newspaper. It kept me very busy for a few days after arrival at Christiania improving the appearance of the ship after her hard experience. The crew was given liberty and enjoyed the privilege. I had one afternoon ashore and purchased some Norwegian porcelain. I also paid a visit to the Viking ship which had been uncovered a few years before in a burial mound of one of the Vikings. The ship was in a good state of preservation--what remained of it. The hull was nearly intact, with thwarts and planking nearly all in place. Even the round, wooden shields which lined the rail on each side were well preserved. The wood was blackened with age, having the appearance of charred wood. A replica of this Viking ship was built and crossed the Atlantic, as the Vikings are supposed to have done, long before Columbus made his first voyage of discovery.

At Christiania, with practically no night darkness, the crew kept late hours. Long after taps at 9: 30 P.M. the men were up, lounging about the decks, smoking, and listening to the serenades from boat parties which rowed about the ship at all hours before sunrise. We sailed from Christiania, and set our course for Denmark, and when a short distance from the island on which Copenhagen is situated we spent one afternoon at target practice. We arrived off Copenhagen shortly after daylight and went at once to the inner harbor, past the ancient fort, the "Dri Kroner" or Three Crowns, without first asking permission to enter the inner harbor as all men-of-war are supposed to do, but no notice was taken of this dereliction of port etiquette by the Danish authorities. What they thought about it we never knew.

The city of Copenhagen is of very great interest to foreign visitors. The Public Gardens are exceptionally fine, and Thorvaldsen's works are on view at the National Museum. The streets and shops are interesting, but I did not find anything particularly novel to purchase in the matter of souvenirs. After a few days' stay the ship sailed for Cronstadt, the fortress-defended city at the mouth of the Neva River on which St. Petersburg is situated. The voyage was uneventful until we reached the head of the Gulf of Finland, where a Russian despatch boat with a pilot and a naval officer for our ship met us and tendered the information that we were expected, and would be given a berth

--15--

at the head of the Cruiser Division of the Russian Navy, in readiness to take part in the reception of the Emperor of Germany who was expected at Cronstadt the next day with a fleet of German battleships, to pay a visit to the Emperor Alexander II of Russia. This was news to us, but our Commanding Officer may have had some information of the event and had timed our visit accordingly. At any rate, the next few days promised to be full of interest, and so they proved to be.

Approaching Cronstadt we found a large fleet of Russian ironclads moored in line, ready to receive the German Emperor William and his fleet. We fired the usual salutes to the Russian flag, the flag of the Senior Naval Commander, and the ship was piloted to a mooring buoy in the inner harbor of Cronstadt, off the Navy Yard and above the city, inside of the great forts built long ago for the defense of the fortress. There were about twenty-five modern vessels in the cruiser squadron, and we felt that our old wooden corvette with ancient artillery was somewhat superfluous in such a naval display. However, we got the ship in order, hoisted our largest American Flag at the peak, and prepared to man yards and carry out the program as laid down for the Russian ships, a copy of which in English was furnished us. Vice Admiral Schwartz, commanding at Cronstadt, sent a naval aide to pay a welcoming call, which our Commander returned. The next forenoon the booming of guns by the Russian armored fleet, answered by the Germans, announced the arrival in the outer harbor of the Emperor of Germany. The Russian royal yacht, North Star, with the Russian Emperor on board, passed along our line, receiving royal honors, on the way to meet and receive the German Emperor on board. More salvoes of artillery followed, and after an hour or two the royal yacht was seen returning with the royal standards of both Emperors flying. This was the signal for manning yards and dressing ship with flags, and more booming of artillery. The guns of the forts joined in the noisy official welcome. With yards manned, officers in special full dress, and the men in white, we waited the passing of the royal yacht. In passing the Cruiser Division she came quite close to the Enterprise, and both Emperors were plainly seen on the yacht's bridge. They both stepped to the side of the bridge nearest our ship and formally answered the salute by our Marine Guard paraded on the poop, and the four rolls of the drums and bugle salute. Both Emperors wore naval uniforms of Admirals. Alexander wore a German uniform and William a Russian uniform. The yacht proceeded to a wharf off Peterhof, the summer palace of the Russian czars, where the German Emperor was to be entertained during his visit. Peterhof was in plain sight of our anchorage, but the palace was hidden in the forest of trees surrounding it.

--16--

The occasion for the German Emperor's visit was not disclosed, of course, but there was no secret that some questions of state were to be discussed, and that the feeling between Russia and Germany at that time was not very cordial, in reality, while appearing to he so on the surface. The flags on the ships were kept flying until sundown. The following day thousands of visitors came down from St. Petersburg in all sorts of floating conveyances--steamers, yachts, sailboats and excursion boats--loaded to the guards to view the assembled fleets. We were surprised by a large steamer appearing close aboard carrying a large and handsomely-uniformed body of officers. They hailed the ship in English and asked to be allowed to visit our ship. We sent boats at once and brought on board nearly the whole officer roll of the Second Cuirassier Guards, a crack cavalry regiment--the Empress' regiment--the officers of which were rated as coming from Russia's noblest families. The Colonel's name I have unfortunately forgotten, but I remember the Lieutenant Colonel, Stepanhoff. All the Russians evinced the liveliest curiosity concerning our ship. They visited every part of her. We did our best to entertain them, after assembling as many as could crowd into our wardroom. We brought out cigars, cigarettes and champagne. They preferred their own cigarettes, I think. They stayed on and talked and talked, asking innumerable questions in regard to our country, for which they expressed great admiration. We finally broke out of our wine locker several cases of the much-despised, sweet Oporta wine we had laid in at Oporto. The Russians took to it like a kitten to new milk, and we got rid of nearly all of the stuff before the Russian officers took their leave. They cheered and cheered as the steamer moved away, and shouted repeatedly, "Come down to Krasnoe Selo and return our visit." We did, and later I will tell about that visit. We dated time from that event for long thereafter.

About six o'clock that evening a steamer from the Navy Yard came alongside with three Russian naval officers on board and announced that they had come to take our officers to Peterhof to witness the great display of fireworks which would take place about nine P.M. after their majesties had dined. It never gets entirely dark at that time of the year in that latitude. Nearly all our officers were absent on one junketing party or another, most of them at the Officers' Club in Cronstadt. We had to send somebody or cause offense, so finally I buckled on my sword, grabbed one of the midshipmen, and joined the Russians on their steamer, supposing that they would bring us back to the ship after the fireworks were over, but the result was otherwise. We were conducted to the Palace, given a good place to stand, from which the hulks in the offing from which the display was

--17--

to be fired were in good view, and our escorts quietly vanished. My companion and I supposed they had absented themselves for a moment only, but we never saw them again, either at Peterhof or any other place during our stay in Russia. However, we were soon interested in the scene before us. In front of the Palace, reaching to the water's edge was a beautiful garden with fountains playing, and the space about the Palace seemed packed with troops and brilliant groups of officers in dress uniforms. The Palace itself, what we saw on the outside of it, seemed not to be an elaborate affair--in fact, a very plain but extensive building. About eleven o'clock or thereabouts the fireworks began, and the display was really fine. They lasted more than an hour, and it was after midnight before they concluded. The crowd began to disperse, troops marching away, and no one appeared to direct us where to go. Finally, we followed the crowd out of the Palace grounds, hoping to bump into a hotel where we could put up for the night, and we found ourselves at last at the railway station. Trains were loading up for St. Petersburg, and while standing on the railway platform a gentleman accosted us, saying, "I am the United States Consul at Cronstadt." We almost fell on his neck for joy. A few words explained our dilemma, and he at once said, "I am returning to Cronstadt by way of Oranienbaum, where I expect to find a steam launch to cross to Cronstadt," and we begged to be allowed to share his fortunes. He was glad to help us out, and we patiently waited for a train from St. Petersburg to Oranienbaum, which is almost opposite Cronstadt. While waiting for the train, we made the chance acquaintance of Mr. Carter Harrison and his wife, who were going in the other direction. Finally a train came along, and keeping close to the Consul we got on board. The Consul was a German, a businessman in Cronstadt, and a gentleman. But for him, I really do not know where we would have landed finally. The train was a slow one, but we reached our destination at last, and hurried down to the waterfront, where the Consul routed out a man who owned a rickety steam launch tied up at the landing. When steam was up, we embarked and thanked our stars we were finally afloat and bound for our ship. The sun was high in the heavens when we reached the Enterprise a little before breakfast time, having been up all night, with nothing to eat or drink. We thanked our Consul for his kindness, and made for the mess table. We had seen much, but the expense in discomfort was great.

Admiral Schwartz paid a visit to the ship, coming alongside unexpectedly without his flag flying in a steam launch. The Captain was not on board, but I did the honors as best I could. The next day I called socially on the Admiral's family at his residence, and had a

--18--

cup of tea made fresh in Russian style with hot water from a samovar kept in readiness. The Admiral's wife was an English lady and a most gracious hostess.

An official dinner was given by Admiral Schwartz to Vice Admiral Knorr and the officers of the German Fleet. Our Captain, myself and two other officers of the Enterprise were also invited to be present. The dinner was typically Russian and very appetizing. Before sitting down to dinner, all partook of the yakouska or a spread of many kinds of appetizers, hors d'oeuvre, caviar, salted fish, sardines, and many dainty dishes I never had seen or heard of before, as well as vodka, of which each guest was expected to take at least a thimbleful. The dinner was enjoyable from a gastronomic viewpoint, with the usual wines with every course. A young Russian naval lieutenant had been detailed to sit next to me and act as interpreter and dinner guide. He recommended so many dishes with accompanying wines that I could not do more than just taste of the majority placed before us, but I liked the taste. After the dessert came the formal speeches and toasts. The first toast was to the German Emperor and, to our surprise, Admiral Schwartz gave it in English. Admiral Knorr responded also in English, apologizing for his lack of command of a language strange to him. He spoke very clearly and expressed himself well. The burden of his remarks was on the necessity of friendship between Germany and Russia. "We must be friends," he said, and concluding his remarks he toasted the Emperor of Russia, which was drunk standing with no "heel taps".

Finally came the day when Emperor William, having concluded his visit, embarked for his return to Germany. The North Star took him out to his fleet, and Emperor Alexander accompanied him. The same ceremony of salutes and dressing ship, with yards manned, was carried out, as featured his arrival. With the departure of the German fleet, the Russian squadrons scattered to their various stations along the Gulf of Finland, and the harbor was almost deserted.

Our ship went into drydock to have repairs made to such injuries as might be revealed, due to our drive at the Drobak defense jetty, before mentioned. It took two full days of twenty-four hours each to pump the water from the dock when we were once in it, due to an antiquated pump of little power as the only one available. The dock was not a large one, either. When the dock was pumped dry, we found that, aside from stripping of the copper from the outside planking, and the "brooming" of several planks near the keel forward, the ship had sustained no injury, but it took a good many days to do the work needed to restore the damage, owing to the small force of ship

--19--

carpenters put to work and the lazy manner of their working. We could not hurry matters and just had to be patient under the circumstances.

While we were in drydock, an interesting religious ceremony took place on the waterfront of Cronstadt, and was participated in by civil and military as well as naval officials. It was the annual blessing of the waters of the River Neva by the Patriarch of the Greek Church at Cronstadt. Troops paraded and a great crowd assembled at the appointed place, where a canopy had been erected. The ceremony occupied only a short time.

Admiral Schwartz very kindly offered to our Commander permission to use the shore rifle range outside the city limits for small arm target practice at shore ranges, an opportunity which does not often happen on foreign stations, and we sent our men organized as companies for this practice. We were obliged, however, to discontinue the use of the target ranges, owing to the ease with which the men were able to get vodka. The last company sent out for practice firing had the following experience. The squads distributed before the targets had hardly commenced practice when Russian moujiks appeared with milk cans and asked permission to sell milk. The Lieutenant in charge foolishly did not suspect anything, made no inspection of the milk cans, and readily gave permission. The men bought milk very freely. In less time than would seem possible, nearly every man in the company was gloriously drunk, and some were helplessly drunk. The milk was almost pure vodka discolored by a little milk. No further attempt was made at target practice, but the Lieutenant did try to march his drunken crowd back to the ship. The men straggled, and those on their feet staggered along in a disorganized mob. Cartridge

--20--

belts, canteens and other equipment were scattered along the way, and some dead drunken sailors reached the ship in droskies. It was days before the greater part of the equipment was picked up, and that was only made possible with the aid of the police. After that experience we gave up land target practice at Cronstadt.

The men behaved very badly while we were in dock, leaving the ship without permission at night and staying away until rounded up by the Russian police. Liquor was cheap and very plentiful, and the men were not of the character of those who compose the enlisted force of today.

The repairs were at last completed and we were floated out of the drydock. As soon as steam could be raised in the boilers, we steamed through the dredged channel from Cronstadt for St. Petersburg and entered the Neva River, proceeding until we reached the quay just below the Alexander Bridge, where we tied up to bollards on the quay. The waters of the Neva are practically fresh off the city and remain so until past Cronstadt. The water is nearly black in color, and in winter very thick ice forms, closing navigation, but communication is kept up by sleighs over the ice. From where we were moored the waterfront and city presented a fine appearance, with the domes of the many churches rising above the mass of buildings. Conspicuous in the view on the south side of the river was the great dome of St. Isaac's Cathedral, while on the north side the fortress of St. Peter and Paul was prominent with the very high and slender gilt spire of the church within the fortress visible as a prominent landmark. There were only two bridges over the Neva to the north side--the Alexander Bridge of stone, and a bridge of boats about half a mile further up the river. In winter before the river freezes over the bridge of boats is dismantled, and when the ice is thick enough sleighs cross on the ice, and temporary track is laid for streetcar traffic.

On arrival we were all furnished passports by the American Embassy and were cautioned never to be without them when ashore. We usually went ashore in uniform, but in citizen's clothes were never questioned. We all received passes for the Winter Palace and other public buildings, and everyone made good use of spare time to see as much of interest as possible. The street signs were puzzling, as they were lettered in Greek letters, but the long, wide street--the Nevsky Prospect--stretching from St. Isaac's to the other end of the city we soon became familiar with, and if we happened to be in any other part of the city and hired a drosky we just said "Nevsky". The driver made for that street, which we recognized as soon as we reached it. From there we soon learned to make our way to the river-front landing.

--21--

Nobody on shore of social standing, and a goodly share of the rest, do not arise in the summer season before noon and sometimes later. The day's pleasures commence in the evening and continue all night long, as there is no darkness requiring lights except a period about midnight. There are many gardens where bands play and out-of-door theatres flourish. One of the most popular at the time of our visit was the Zoological Garden. The stock of animals was very limited-about a dozen little Russian bears, who would stand on their hind legs and beg for bread through the bars of their cages while they were fed by other Russian bears who had imbibed freely during the evening and could scarcely stand on their hind legs, many of them. There was a great stage with a very large orchestra, while the seats were all out in the open. Admission was charged to the Garden--a nominal sum--and the theatre was free for all, but in the numerous caf&eactue;s lining the enclosure drinks were not free by any means. The principal entertainment given at the theatre was a splendid ballet, of which the Russian audience seemed particularly appreciative for they applauded uproariously. I went twice to the Zoological Gardens as guest of Russian naval officers.

We had hosts of visitors, and almost every day some of our old friends of the Second Cuirassier Regiment who came to the city from the great summer camp at Krasnoe Selo would appear on the quay opposite the ship, signal for a boat, and come on board to ask when we were going to the summer camp to return their visit. Finally the Colonel of the Regiment telegraphed our Commander asking him to set a day. It was evident the visit could not be longer postponed, so a day was set, the Colonel was informed, and a party was made up for the visit. Besides the Commander and myself, the party included two lieutenants, the surgeon and the paymaster. We were all in dress uniforms, epaulettes, cocked hats, swords and all that goes with that dress, but we did not take overcoats or capes as it was warm. We little knew how cold a Russian night can become, even after a hot day, and we wished many times for outer warm clothing. Taking a train at the station on which a special first-class carriage had been placed at our disposal, we reached Krasnoe Selo about three o'clock in the afternoon. Alighting from the train, we found a delegation of officers in waiting, each with a three-horse troika and a wild looking moujik on the box. The Commander was paired off with the Colonel, I was taken in charge by Stepanhoff, the Lieutenant Colonel, and the rest of our party was similarly paired off. When we were aboard, away went the troikas in a glad procession at full gallop. Now be it known that a troika is an open Victoria with just one seat at the back, the driver's box being much elevated in front. There are

--22--

three horses--one between the shafts of the vehicle, and a horse on each side of the middle one. The horse in the middle trots or gallops as he feels inclined or is urged by the whip or shouts of the jehu on the box, while the outside horses always gallop, with their heads pulled down and outside by check reins. There is no protection in the vehicle at the sides from the dirt or mud thrown to the rear by the hoofs of the galloping horses, and, road conditions favoring, they throw plenty of mud and dirt, which accumulates plentifully on the persons of the occupants of the back seat. With much clatter and shouts from the drivers, the cavalcade in a few minutes reached the barracks of the regiment--just plain wooden structures, unpainted and looking weatherworn. We halted in front of a large structure they called the mess and found a large body of officers waiting to receive us, which they did joyously. After introductions all around, and partaking of the bounteous [yakouska] which we patronized sparingly, being wary and mindful of the ordeal ahead of us, we were escorted to the Officers' Mess Hall. Nearly a hundred officers of all grades were at table, the Colonel presiding. A very fine dinner of many courses with wines of rare flavor followed and lasted for nearly two hours. Coffee, cigars and cigarettes, with cordials and pousse-café were next placed before us, and it must have been around seven in the evening when we arose from the table. All through the dinner we had been addressed in English, and the officers of the regiment did their best to make us feel they were glad to have us with them.

We were next asked if we would like to see some of the fine horses owned by officers of the regiment, and we all adjourned to an open space at the rear of the Mess Hall where a long string of splendid animals had gathered by direction while we were at dinner. The horses were slowly led by and commented upon. They were certainly worth seeing, but while the horse show was going on I noticed a party of thirty or forty of the stalwart guardsmen quietly closing around the Lieutenant Colonel and myself. Presently the soldiers began to sing, and then some danced grotesque dances which amused me very much and I applauded heartily. While I was applauding, the troopers suddenly and without warning rushed toward me, grabbed me in many pairs of hands and tossed me high in the air above their heads. When I came down, they caught me gently on their hands and hove me up again, shouting huzzas or something similar. I was soon out of breath with this unwonted exercise, so the troopers placed me on my feet, stood back a pace or two, and everyone came to a hand salute. Col. Stepanhoff said, "My dear sir, you have just received from this regiment an honor rarely given and one which princes of the blood royal would be glad to receive but do not get as

--23--

a rule." Gasping for breath, I said: "I--can--scarcely--find--words--to express my appreciation--of the honor--but I am only--the second in rank, and my superior officer has not been so honored," Stepanhoff said, "Where is your senior?" I pointed to the Commander whose back was turned to us as he stood talking to the Colonel, and said, "There he is." Stepanhoff spoke a word or two to the noncommissioned officers with the men, and the troopers made a rush for the Commander, much to his astonishment, and tossed him up in the air as they had honored me. His cocked hat fell off, as did his eyeglasses, and his uniform was generally awry when they stood him on his feet and saluted. "Has this honor a name?" I asked the Lieutenant Colonel. "No," he said, "what would you name it?" I said, "I think it might be appropriately called 'The Oriental Grand Bounce'." At any rate the Commander and I were duly initiated. Why the rest of our party escaped like initiation I never learned, but they did.

It was commencing to rain a light drizzle when the parade of horses was over, and though it was after 8 P.M. it was still broad daylight, and our hosts suggested a drive about the great camp, where some 70,000 troops, the flower of the Russian Army, were under canvas and in wooden barracks for the summer. The troikas were brought around, and the drive began through the camp which extended for miles. The guards turned out to salute the cavalcade as it passed at a gallop, and the horses' hoofs threw a light shower of mud which bespattered our dress uniforms and the cloaks of our escorts. We had no cloaks or overcoats, but wished we did have them for the night was getting cold. The drive lasted about an hour, and we were finally landed at the entrance of a great barn of a theatre, built of wood, where opera and ballet performances were given every evening for the entertainment of the officers of the many regiments assembled in camp. The theatre was crowded with officers, no ladies being present, of course. We were brushed off and introduced to the box reserved for our host's regiment. An opera was being presented, but just what it was I do not remember. Anyway we sat out one act only and then were taken to a larger restaurant where an elaborate supper was served--many dishes and many wines. We ate and drank sparingly, keeping our heads clear, but it was long past midnight when the feast was over. We were all in good shape, and our Commander expressed the very great pleasure we had all experienced, and added we thought it time to be saying our adieux. The troikas with our hosts took us to the railway station where our special train was standing on a siding, and after thanking our hosts for the royal entertainment and saying "au revoir", we climbed into the comfortable railway

--24--

carriage and settled down for the return journey to St. Petersburg, congratulating ourselves that we had gone through the strenuous entertainment in good shape. We waited and waited for the train to start, but the station master did not give any signal to start. We could not understand why we did not start. Finally, after a long wait, the Colonel put his head into the car window of our compartment and said to our Commander: "I beg your pardon, Captain, for troubling you after you are in your train, but the Grand Duke, brother of the Emperor, is at a bivouac of troops who will begin maneuvers at sunrise, and he has expressed a desire that the American officers pay him a visit at the bivouac before he starts on the maneuvers." We were astounded, but could not refuse a request of that origin, so we climbed out of our comfortable, warm compartment and boarded the blessed troikas again for a drive of twelve versts, or about seven miles, to the bivouac, in the cold air of the early morning. When we arrived we found that the Grand Duke and the troops had broken camp and had already begun the march to the scene of their exercises. It was all a "put-up job." We found already on the spot the band, a company of singers, and an army wagon packed with tables, hampers of provisions and liquors and all the paraphernalia for a feast. It is doubtful if the Grand Duke knew that we were in the country. However, we resigned ourselves to whatever was to come, which was a plenty. The long tables were soon set up, and many servants soon had them laid. We all sat down and the feast began. There was food and drink--mostly drink--and when we had all had rather more than enough, our hosts produced a great kettle of a silver punch bowl and announced that we would wind up with a "jouka punch". We watched its brewing with much curiosity, not to say apprehension. Three daggers were placed on the rim of the punch bowl forming a triangle, on which was placed a large lump of loaf sugar. Brandy was poured over the sugar, which was then lighted. As the alcohol burned with a sickly blue flame, drops of melted sugar fell into the bowl. Then were added wines of all sorts, together with slices of oranges, lemons and some strawberries. The bowl was full when the punch was completed. It had a dark brown color and looked deadly. It was. A level tumbler full was served to each officer, and the Colonel proposed a toast to the health of the Czar. The drink consumed, dancing commenced on the greensward, the band being led personally by the Colonel. The dancing was more grotesque than enjoyable, hampered as all were by their swords which furnished obstacles over which the dancers repeatedly and undignifiedly tripped. The sun was well up when we begged to be let off, and in spite of our hosts' anxiety to mix another "jouka punch" we finally persuaded our hosts to call

--25--

the entertainment at an end. Wearily we climbed aboard the troikas, numb with cold, for we had been out all night and looked it. It was more than an hour's drive back to camp at a gallop, and we landed at the Colonel's quarters. There we drank many cups of strong, hot tea, which speeded our recuperation, and about noon we finally were driven to the railway station and put aboard our train, which this time departed promptly. We reached our ship about three o'clock in the afternoon, and most of us went to bed and slept long and soundly. It was a wonderful and unique experience, typical of the style of entertaining usual and thought proper at that time, but no one of our party who was thus entertained will, I think, ever forget it, or care to go through another one.

The stay at St. Petersburg was made more eventful for me by a visit to the Russian gun factory on the southwest outskirts of the city at (Petrolkof?), where all the processes from the pouring of the steel to form the ingots which were subjected to hydraulic compression, to their forging, finishing and assembling in the built-up gun were shown, and a finished gun was fired for proof. The visit was arranged for and I was accompanied by Lieut. B. H. Buckingham, our Naval Attache at St. Petersburg. It was a visit of great value to me personally, but I did not make a report to the Navy Department as that would have infringed on the prerogative of Buckingham.

I purchased a samovar made at Tula, south of Moscow, and other articles of brass of fine workmanship. I regret now that I did not take advantage of the opportunity to buy furs and rugs. Shopping was very difficult owing to the language, and lack of being posted as to values, but I collected some examples of Russian porcelain.

A longer stay could have been enjoyed, but our schedule was a long one, and with some regret we sailed for the lovely capital of Sweden, Stockholm, a port very rarely visited by men-of-war owing to the intricate navigation required through the maze of islands behind which the harbor of Stockholm is situated. A capable pilot took us in and anchored the ship in a quiet basin from which the fine city was in view, with imposing public buildings and fine gardens bordering the waterfront. Invitations to many entertainments were forthcoming soon after our arrival, but only a few could be accepted on account of lack of time. The week at Stockholm passed all too quickly, and our next port was Danzig, where the anchorage near the city is exposed to the wind and sea from the Baltic, rendering boating very difficult. Often with a north wind we were hours without communication with the shore. One Sunday afternoon the officers were given a luncheon by the officers of a German regiment who were

--26--

very hospitable and friendly. One of the officers, a Captain, had married a lady from Buffalo, New York. He spoke perfect English and, during the visit of the ship, did much to add to the entertainment of our people.

Proceeding down the Baltic from Danzig, our destination was not announced by the Commander, and we were surprised, but agreeably so, when we brought up at Swinemunde at the mouth of the Oder River, on which the thriving city of Stettin is situated, with extensive shipbuilding works. I do not remember a time, if ever before, an American man-of-war visited Stettin. The mouth of the Oder and vicinity is a favorite seaside resort for Berliners and others for the benefit of sea bathing and the cool air of the Baltic in the hot summer months. With the aid of a pilot the ship proceeded up the Oder River to the point where it bends sharply to the eastward, where a deep water, sea level canal had been constructed through a stretch of several miles straight south, joining the river again below Stettin, a saving of about twenty miles in distance and avoiding shoal river navigation. We moored opposite the city, amid other shipping, to bollards or clusters of piles bound together with iron bands, tying up with our own hawsers. Opposite the ship was a good landing, and a small square, out of which broad streets lead to the business districts of the city. Our Consul at Stettin was very glad to see us and talk with his own countrymen.

Stettin is not far from Berlin by rail, and all who could be spared from duty were given leave to visit the German capital. Chief Engineer Entwistle and I made the trip together. We stopped at the Kaiserhof, visited the palaces, museums and principal gardens, lunched at the prominent cafés, promenaded "Unter den Linden", went to the music halls and listened to fine bands in the evening, and altogether spent three very profitable and delightful days in Berlin.

Our men were very restless at Stettin, many of them leaving the ship without permission, although leave was given to all the crew entitled to it. We were not far from the landing opposite, but one of our men, a fireman, was drowned trying to swim ashore. His funeral, held a day after the recovery of his body, attracted much attention. The German Military Commander sent a platoon of soldiers to march with our men in the funeral cortege.

We did not touch at any other German port on our way out of the Baltic, but anchored one day off Elsinore in full view of the castle where Hamlet is supposed to have made his home in the celebrated play by Shakespeare. I went ashore for an hour or two and bought

--27--

some samples of Danish porcelain as souvenirs of Denmark but not of Hamlet.

The next voyage was across the North Sea to Leith, the seaport of Edinburgh, Scotland, with which it is connected by tramway lines and a fine paved road. There are very extensive docks at Leith with tidal locks. The rise and fall of the tide is twenty to twenty-five feet, and ships can only enter or leave the tidal basins at high water when the locks are open. We had to coal ship at Leith, and to go into the tidal basin to do so, I took the ship in without a pilot and tied up at the coal dock, where our coal was dumped on our spar deck a carload at a time by means of an hydraulic lift. While we remained at the dock, all who could visited Edinburgh and its historical points of interest. I made a trip to Glasgow to visit an exhibition of Scotch Industries and found it interesting. We made several interesting side trips in the neighborhood of Edinburgh and Leith.

After we came out of the tidal basin, we anchored overnight in the roadstead until we were joined by Mr. B. F. Stevens, our Despatch Agent in London, who wanted to make a sea trip to Amsterdam, our next port in our itinerary. The North Sea was rough when we got outside, but the wind was favorable and we ran before it, making good time and arriving off Ijmudrn or the mouth of the "Nord See Canal" leading to Amsterdam about midnight of the night following our departure from Leith. The night was clear and harbor lights were visible, and the Commander decided to run in behind the breakwaters, although the harbor was full of shipping, rather than roll about outside until daylight. We ran in and managed to stop and drop an anchor without colliding with other vessels, but there was not much to spare. The harbor inside the breakwaters at Ijmudrn where vessels wait to enter the North Sea Canal for Amsterdam is not very large, and as a gale was blowing outside, the small anchorage was packed with vessels large and small. There is a tidal lock at the entrance to the canal, but vessels are taken in at almost any stage of the tide by being lifted up to the canal level. Early the next morning our ship with a pilot on board was signaled to enter the canal. We got underway, steamed to the lock and were raised to the canal level in a few minutes and sent on our way. It was a curious experience, for in many places the canal protected by dikes was above the level of the country through which we were passing. Large herds of dairy cattle were seen in the fields, and we passed through two or more railway bridges which were swung to allow the passage of ships. The canal is wide enough to permit steamers of large size to pass, and there is no delay.

--28--

Arriving at the Zuyder Zee at Amsterdam, we were moored in a large basin near the terminal docks of the Dutch Transatlantic Steamship Co. operating liners to New York. The principal thing in my memory of Amsterdam aside from the historical points of interest is that of the mosquito pest. Our ship was not screened so far as doors and air ports were concerned, and we suffered intensely. The men also had no protection and had scarcely any sleep. I purchased a couple of Delft plaques and cups and saucers as souvenirs. We were not sorry to be on our way from Amsterdam, a stay of five days being quite long enough.

Steaming down the North Sea toward the Straits of Dover, we passed close to the Goodwin Sands, the scene of many wrecks in the days of sailing ships, and the scene of many heroic rescues of shipwrecked seamen by the lifeboats' crews of the Ramsgate and Margate Stations. The story of many of these incidents is given in a book called "Storm Warriors", written by an English clergyman whose name I have unfortunately not remembered. We kept over to the French side of the Straits of Dover and we speculated on our probable destination somewhere on the French Coast, and some guessed Cherbourg, but we were surprised when we ran into the outer harbor of Havre and signaled for a pilot who came on board at once. We did not anchor but kept on up toward the head of the Bay and entered the mouth of the River Seine. The tide was just beginning to flood, and we made excellent time favored by the tide, passing through most interesting and picturesque country, the Province of Normandy. The river had many bends and turns, but all shallow places had been dredged out and the river banks revetted with stone as a protection against washing away by the tidal bore which comes in twice a day with a roar like the surf on the beach, and a wave crest

--29--

several feet high. The bore passed us while we were in one of the long reaches, but bothered us not at all for we were going with it, and it broke along the sides of the ship without wetting our decks.