The Navy Department Library

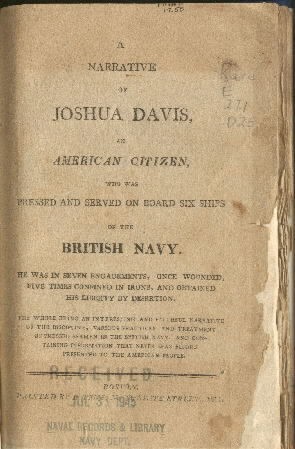

Narrative of Joshua Davis, an American Citizen

Who Was Pressed and Served on Board Six Ships of the British Navy, He was in Seven Engagements, Once Wounded, Five Times Confined in Irons, and Obtained His Liberty by Desertion.

The Whole Being an Interesting and Faithful Narrative of the Discipline, Various Practices and Treatment of Pressed Seamen in the British Navy. And Containing Information That Never was Before Presented to the American People.

BOSTON,

PRINTED BY B TRUE No. 78 STATE STREET.

1811.

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS, TO WIT:

DISTRICT CLERK'S OFFICE.

BE IT REMEMBERED, that on the seventh day of March, A.D. 1811, and in the thirty fifth year of the Independence of the United States of America, Joshua Davis, of the said District, has deposited in this Office the Title of a Book, the Right whereof he claims as author, in the Words following, to wit:--"A Narrative of Joshua Davis an American Citizen, who was pressed and served on board six ships of the British Navy. He was in seven engagements, once wounded, five times confined in irons, and obtained his liberty by desertion. The whole being an interesting and faithful narrative of the discipline, various practices and treatment of pressed seamen in the British navy, and containing information that was never before presented to the American people." In conformity to the Act of the Congress of the United States, intitled "An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of Maps, Charts and Books, to the Authors and Proprietors of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned;" and also to the Act, intitled "An act supplementary to an Act, intitled An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by securing the Copies of Maps, Charts and Books, to the Authors and Proprietors of such Copies during the times therein mentioned; and extending the Benefits thereof to the Arts of Designing, Engraving and Etching Historical, and other Prints."

| Wm S. SHAW, | { | Clerk of the District of Massachusetts |

--2--

NARRATIVE, &c.

I, JOSHUA DAVIS, was born in Boston, in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, on the 30th of June 1760. On the 14th of June, 1779, I entered on board of the privateer Jason, of 20 guns, commanded by Commodore John Manly, bound on a cruise. About the 25th of the same month, we sailed from Boston to Portsmouth, NH in order to take on board Lieut. Frost, and a number of men. We arrived there the next day, and after taking the men on board, put to sea again. The morning following, the man at the masthead discovered two sail a head of us. Our Captain went up in the fore-top with a spy glass to see what they were. On his coming down, he told Lieut. Thayer he supposed the two vessels to be one of our privateers with a prize. Lieut. Thayer went forward with the glass, and after looking sometime, said one of them appeared to be a frigate and the other a brig. On running nearer them, we supposed them to be enemies, and Lieut. Thayer advised the Captain to heave the ship in stays, to see if they would follow us; to which the Captain consented, and we hove the ship about. When they saw this, they hove in stays, and gave us chase. We ran back for Portsmouth, and by

--3--

the time we had got within half a league of the Isle of Shoals, the vessel got within two gun-shot of us. We perceived a squall coming on to the westward, very fast, and the Captain ordered every man to stand by, to take in sail. When the squall struck us, it hove us all aback--when we clued down. In ten seconds the wind shifted to our starboard beam, and shivered our sails. In a few seconds more the wind shifted on the starboard quarter, and struck us with such force that hove us on our beam ends, and carried away our three masts and bowsprit. She immediately righted and the squall went over. The vessels that were in chase of us saw our trouble--hove about--and went off with the squall; and we saw no more of them.

We went to work, to strip our masts, and to get the sails and rigging on board; when we found one of our men drowned under the fore-top-sail. We got up jury-masts, and run in between the Isle of Shoals and Portsmouth, where our Captain was determined to take our masts in. In a few days Capt. MANLY went on shore to see to getting the masts on board. While he was gone, Patrick Cruckschanks, our boatswain, and John Graves, captain of the forecastle, went forward and set down on the stump of the bowsprit, and said they would not step the masts in such a wild rodestead, to endanger their lives; but if the ship was taken into the harbour, they would do it with pleasure. When the Captain came on board, he asked Mr. Thayer why the people were not at work; and

--4--

was told they wished to get into the harbour first. The Captain answered. "I'll harbor them," and stepped up to the sentry at the cabin door, took his cutlass out of his hand, and ran forward, and said, "boatswain, why do you not go to work?" He began to tell him the impropriety of getting the masts in where the ship was; when Capt. MANLY struck him with the cutlass on the cheek, with such force that his teeth were to be seen from the upper part of his jaw to the lower part of his chin. He next spoke to John Graves, and interrogated, and was answered in a similar manner, when the Captain struck him with the cutlass on the head, which cut him so bad that he was obliged to be sent to the hospital, with the boatswain. The Captain then called the other to come down, and go to work. Michael Wall came down to him; the Captain made a stroke at him, which missed, and while the Captain was lifting up the cutlass to strike him again, Wall gave him a push against the stump of the foremast, and ran aft; the Captain made after him--Wall ran to the main hatchway and jumped down between the decks, and hurt himself very much. The Captain then, with severe threats, ordered the people to go to work; they went to work, and stepped the masts, got the topmasts on end, lower yards athwart, top sail yards on the cap, top gallant masts on end, sails bent, running rigging rove, boats on the booms, &c. and all done in the space of 36 hours.

Next day a privateer brig, called the Hazard,

--5--

from Boston, came down under our stern, and hailed us; we informed them it was the Jason, John Manly, commander. The Captain then said, "my orders from the General Court is, that all vessels of war that I meet with on my way to Penobscot, must repair there without fail." To which the Captain consented.

As soon as the Hazard was out of sight, we tript our anchor and stood to sea. In a few days we were off Sandy Hook; we hove too, and drifted off and on with the tide for a few days. One day our sailing master went to the fore-top-mast-head, to look out for a sail; about 3 o'clock he cried out, "a sail on the weather bow;" in a few minutes after, another; we made sail, and stood for them. As soon as they perceived us, they bore away for [from] us. In about two hours we were within two gun shot of them. Our Captain ordered every man to his quarters. The enemy hove upon the wind, with his larboard tacks on board--run up his courses, hoisted his colours, and gave us a broad side. Our Captain ordered the sailing master to get the best bower anchor out, so that the bill of it should take into the fore shrouds of the enemy. It was quickly done. The Captain ordered the helm hard a-port, which brought us a long side. The anchor caught their fore rigging. Our Captain then said, "fire away, my boys." We then gave them a broadside, which tore her off side very much, and killed and wounded some of them. The rest ran below, except their Captain, who stood on the deck like a man amazed.

--6--

Our Captain order Lieut. Frost to go out on the driver boom and get on board of her, and send the Captain on board of us, and keep the prisoners below. It was done; and as soon as the Captain came on board of us, our men on board of her cut away all her fore rigging, and pushed her ahead, to clear our anchor. When we got disentangled, we bore away for the other privateer, that began to run from us. We gave her a few shot from our bow chasers, and she hove too. Our Captain told them to take their boat and come on board. They answered, "our boat won't swim." Our Captain said, "then sink in her; you shall come on board or I will fire into you." They then out boat and came on board.

After we got all our prisoners in irons, and put all things to rights, we made sail for Boston, where we arrived in a few days.

In the action we had our sailing master wounded in the head, and was sent to the hospital, where he died of his wounds. He was the only man hurt in the engagement.--The two brigs taken were both privateers--one called the Hazard, of 18 guns, from Liverpool; the other called the Adventurer, of 18 guns, from Glasgow.

In a few days our commander came on board, and ordered the anchor up, as quick as possible, to run to sea. We crowded all sail upon her for all that night and next day. On the morning following, being on Nantucket Shoals, (and very foggy) a man on the forecastle cried out "sail ahead, within one cable's length of us."

--7--

We run under her stern; and Lieut. Thayer hailed them. They answered they were from Liverpool, bound to New York. Our captain came on deck and said to Mr. Thayer that he would give them a shot, and make them heave too. At that instant a man called out "a sail to windward" and a man in the foretop said "there is a fleet bearing down upon us." We had to run to the northward of the fleet, until we judged ourselves clear of them. In about one hour after the fog cleared off so that we could discover about 40 sail; and a large ship astern of them all. She crowded all sail to get away from us. We came up with her very fast. Our captain said to Mr. Thayer, "that ship has got drags along side, and means to trap us; we will go about and try them." No sooner had we hove in stays, than they in studding sails, hove about, and came on pretty briskly after us. When she got within two gunshot of us, the fog came on again, and we lost sight of her. We stood on to the eastward for some days, when a man in the mast head cried out "a sail to leeward of us;" we put away for her, and crowded all the canvas we could put on her. In two hours we run her hull down; when a man at the maintopmasthead cries out, "two sail bearing down on the ship we are chasing." It was almost night, and our captain thought fit to give over the chase, and run under easy sail until next morning. In the morning we discovered two sail in chase of us, their hulls full in sight, and coming up with us very fast. We were ordered to

--8--

man the guns on both sides of the ship. One of them came up under our starboard quarter. A man in our maintop insisted that it was the Dean frigate, and that he saw his old captain (Nickerson) on the quarter deck. Our captain, to prove the man's words, took the spy-glass, and was satisfied that it was Capt. Nickerson.--We hailed each other, and afterwards our captain went on board of her. The other ship was the Boston frigate, of 36 guns, commanded by Capt. Tucker. We sailed in company ten or twelve days, when we parted, and gave them a salute of 13 guns, which they returned.

We then made sail, and run to the eastward. A few days after, the ship's company had pork served out to them. Thirty two pieces were hung over the ship's side to soak over night. The next morning a man went to his rope, and on pulling it up, found the rope bit, and the pork gone. Every man ran to his rope, and found them bitten in the same way. They went aft, and looked over the taffrel, and saw a shark under the stern. Our captain came upon deck, and ordered the boatswain to bring him a shark hook. He baited it with three pounds of pork. The shark took hold of the bait, and hooked himself. We made the chain fast to the main brace; and when we got him half way up, he slapt his tail, and stove in four panes of the cabin windows. We got a bite of rope round his tail, and pulled him on board; and when he found himself on deck, he drove the man from the helm, and broke two spokes of the wheel. The carpenter took an axe,

--9--

and struck him on the neck, which cut his head nearly off; (the boatswain tickling the shark under the belly with a handspike to keep his eyes off the carpenter.) When he had nearly bled to death, the carpenter gave him another blow, which severed his head from the body. Our captain then ordered the steward to give the ship's company two casks of butter, and the cook to prepare the shark for the people's dinner. He was 11-1/2 feet long.

In about 8 days after, the man at the mast-head sung out "a sail ahead." We gave chase to her, and in six hours came up with her. Our captain hailed them, and they answered they were from Bristol, bound to Barbadoes. Mr. Thayer went on board, and took the captain and four men and brought them on board of us, with two bags of dollars. We put a prize master and twelve men on board of her, and ordered her for Boston, where we afterwards found she arrived safe. She was a letter-of-marque, of 16 six-pounders, loaded with beef, pork, cheese, hats, &c. She had taken a Spanish vessel just before, from whom they took the money which we took from them.

We stood to the eastward for some time, and could not meet with anything--when we changed our coarse n. w. and in a few days were on the Banks of Newfoundland. One morning a man cried out from mast-head, "a sail bearing down upon us." We lay too until she came up with us. On hailing her, we were informed they were from Martinico. Their captain came on board, and said he

--10--

would give a barrel of sugar or rum for a barrel of water. We let him have four barrels of water for two of rum and two of sugar--He dined and supped with us, and went on board his vessel about 10 o'clock.

On the 30th Sept. the man at the maintopmasthead cried out, "a sail on our starboard beam." It being very calm, we could not then give them chase; but the wind began to rise about eight o'clock. She took the wind first, and came after us. We put away from her, and run all day under as much sail as we could croud. She came up under our larboard quarter about eleven that night. On hailing her, we found her to be the Surprise Frigate. They hailed us, "what ship is that?" We answered the Dean. They ordered us to "heave too, or they would fire into us." We replied, "fire away, and be d--d, we have got as many guns as you." They then gave us a broadside--Our captain would not let us fire until they got abreast of us. They gave us another broadside, which cut away some of our running rigging, and drove some of our men from the tops. We gave them a broadside, which silenced two of her bow guns. The next we gave her, cut away her maintopsail, and drove her maintop-men out of it. Both sides continued the fire until one o'clock. Our studding sails and booms, our sails, rigging, yards, &c. were so cut away that they were useless. Lanterns were hung at the ship's side, between the guns, on nails; but they soon fell on deck, at the shaking of the guns; which made it so dark that the men could not

--11--

see to load the guns. They broke the fore hatches open, and ran below. Our captain sent the sailing master forward to see why the bow guns did not keep the fire up; but he never returned. The captain then sent the masters mate on the same errand, and he never returned. It was therefore thought needless to stand it any longer, and the captain took the trumpet and called out for quarters--Then turning round to the men on deck, ordered them to go below and receive their prize money. I went down into the cabin, where I saw the two bags of money emptied on the table. Every man was paid according to his abilities. Eight dollars were given to me as my share. I went on deck, and found the ship reeling one way and the other. The man at the wheel was killed, and no one to take the helm. The rigging, sails, yards, &c. were spread all over the deck--the wounded men were carried to the cockpit; the dead men lying on deck, and no one to throw them overboard. The well men were gone below to get their clothes, in order to go on board the frigate--Soon after the frigate's long boat came with their first Lieutenant and about 20 sailors and marines; when every man that could be found on deck were drove into the boat. I went down into the Steward's room, in order to stay on board until we got into port. The doctor bid me stay with him, and attend to the wounded. The next night about 12 o'clock, one of the marines went into the hold to get some water--He overheard some of our men talking, and listened to them,

--12--

and heard them say that, at two o'clock, they intended rising on the men on deck, and carry the ship into Boston. The man went on deck, and told his officer what he had heard. The officer took all his men into the cabin, and armed them with pistols and cutlashes; and went into the hold, and ordered every man to come forward, or he would destroy them. They all, to the amount of thirty two men, came forward, and were put in irons, by the feet--I was taken from the doctor, and put in irons with the rest. In the course of ten days we arrived at St. Johns, Newfoundland, October 10th. We were all taken out of irons, and ordered on deck, to be searched for the money we had shared amongst us, when we were taken. I took four dollars out of my pocket, and hid them in the linings of the ship, in order to save them from the plunderers. I went on deck, when they searched me, and took the other four dollars from me. I went below again to get my money, but, alas! it was gone.

In the afternoon I was told by Mr. Lane, Lieutenant of the frigate, that I was to go on board of her, to do duty with the drummer. I told him I was a prisoner of war, and would not go. He called me a d--d yankee rascal, and if I said a word more, he would tie me up to the gangway and give me a dozen of lashes. Our people were ordered to prison, and while the Lieutenant was in the cabin, I hid myself in the boat among the prisoners, and went on board the prison ship, where they put us all in irons as fast as we got on board.--

--13--

While they were putting the handcuffs on me, the Lieutenant came up and took me by the collar, and said, "you d--d rascal, how came you here? away on board of the boat, this minute." I went into the boat, and rowed to the frigate. Capt. Reves, the Commander, called me into the cabin, and said if I behaved well he would give me a midshipman's pay; but his words proved false, for I found I was put in the ship's books as a gunners boy, at 16 shillings 6 pence per month.

Admiral Edwards, of the Portland, of 50 guns, ordered Commodore Manly to come on board his ship, as he had something to communicate to him. As soon as he arrived on board, Adm. Edwards asked Commodore Manly his name. Answer, John Manly. "Are you not the same John Manly that commanded a privateer from Boston, called the Columbia?" Answer, yes. "Were you not taken by his Majesty's ship Thunderer, and carried into Barbadoes, where the Governor of the island gave you a parole of honour." The answer was, yes. "Did you not go to the jail keeper, and bribe him; make your escape out of jail, take the King's tender by night, put the men in irons, and carry her into Philadelphia?" No answer was given to this question by Capt. Manly. Admiral Edwards said, "you are no gentleman, Sir; go on board of the ship that took you, and there you shall be confined until you arrive in England, where you shall be kept during the war"--which words were verified; for we no sooner arrived in Plymouth

--14--

than the Commodore was sent to Mill prison, where he remained until the year 1782, when an exchange of prisoners took place, and he was sent to France, when he soon reached Boston, where he had the pleasure of taking the command of a continental frigate, and sailed for the West Indies.

In the course of 13 days he took a valuable ship of 20 guns, loaded with all kinds of provision, for the army at New York. He was finally drove into Martinico Bay by a 50 gun ship and a frigate, who kept him there until the peace between Great Britain and the United States.

On the 6th day of November, we got under way with the Portland 50 gun ship, a large convey of shipping bound for England, where we arrived December 8. While our ship was lying in Plymouth Sound, an order was sent on board from Admiral Digby, commander in Plymouth Dock, to slip our cables, and put to sea. We immediately obeyed our orders, and run to the westward; laying too all the night. Next morning we saw a sail to the leeward of us. We bore down, in order to speak to her. It being hazy weather, and a gale coming on we thought it best to heave too, in order to take in sail; which we had scarcely finished, when another sail was seen to leeward of the first, (a brig.) We run down under the brigs quarter, and hailed her. They informed us that she was the Hope, kings tender, from Falmouth bound for Portsmouth, Eng. with a number of officers belonging to the 32nd regiment of foot. We left her and gave chase to the other sail,

--15--

a ship, which we overhauled very fast. In the course of two hours we came up with them, and ordered them to strike their colours, which they refused to do. We gave them a broadside, and they returned it--We gave them one more, which made them haul their colours down. We run to the leeward, in order to secure our half port, and bring our ship to the wind; it blowing very hard, we could not beat up for her. In a few minutes our prize came bearing down for us, under the press of sail.--When perceived by our Captain, he ordered the ship put away, and as much sail crowded as she could bear; but all to no purpose; the prize came upon us very fast, and seemed determined to sink us, by running foul of our stern, which we perceived when they got within pistol shot. Our Captain hailed them, and ordered them to bear away, or we would fire a broadside and sink them. They did not mind the order, but came down on our starboard quarter with such force as to tear away our quarter badges with the fluke of his small bow anchor. --The violence of the shock was so hard, that most of our men fell on the ship's deck. The prize immediately hove too, when we distinctly saw a number of English officers, with read [red] coats, on her deck. We hoisted out our cutter, which sunk in a few minutes--we then got our pinnace out, but she stove alongside--then tried the Captain's barge, and she stove to pieces, under the ship's starboard quarter; finally we got the long boat out, and dropped her down safe; a number of seamen

--16--

and marines got on board of her out of the gun-room windows. In going to the prize, a sea struck her, and filled her so that she would have sunk, had not the officers on deck thrown a rope to their assistance, which they caught, and hauled up to the prize's stern, and on getting on board, cut the boat away. The next day the wind shifted to the westward--we ran up Cherwell with our prize, and got safe into Plymouth Sound. In a few days we were ordered to Portsmouth, with our prize, where she was overhauled by the carpenters of the dock yard, and found to be fit for his Majesty's service. She was called the Gay Truin, which name she still bears.

Our ship lay at Spithead for some days, until an order was sent on board for us to get under way, and sail in company with the Indiaman, of 44 guns, the Emerald frigate of 36, the Huzza ship of 20, the Squirrel do. of 20, the Wasp lugger of 12, and the Wolfe cutter of 12, to go to Concall Bay, on the French coast, and cut out two 74 gun ships, that then lay in Saint Mallows harbour. We proceeded to Concall Bay that night, and got within gun shot of the ships, when the wind failed us; the tide running strong against us, and day light fast approaching, we were obliged to put away. When we run by fort Grenville, they saw and fired upon us with round shot, which carried away the Indiaman's fore topmast, jib-boom, crotchet yard, and killed and wounded a number of her men. The Emerald lost her Captain and four men, and a number of wounded,

--17--

rigging cut away, &c. The Surprize, (which I belonged to) had two men killed and five wounded, rigging cut, &c. The Huzza had no men killed, but three wounded, and her rigging cut. The Squirrel had none killed or wounded, but her spritsail yard was carried away. The Wasp and Wolfe both got clear, by running into shoal water. We made sail for Portsmouth, where we arrived in two days after. Our ship was ordered to go into dock.

As soon as we had tript our anchor, a midshipman came up to me and told me to take my hammock, and go with him on board the guard ship (the Arrogant of 74 guns) to which I with reluctance complied; and when put on board was ordered to do duty with the drummer. A few days after a number of impressed men came on board from a vessel from the Streights, and brought a fever with them, which raged amongst the ship's company, which amounted to fifteen hundred in the whole.

The sickness raged to such a degree, that in the course of ten days we had seventy two men carried on shore, not being permitted to carry them through the town to the burying ground. For myself, I had to get up every morning to play the revellee on the forecastle. As I passed by the main hatches, I took notice of from five to nine dead men sowed up in their hammocks. Every morning the boats sent with provisions to us from shore, were ordered to go to the buoy of our anchor, and there leave them until we took them along side, and cleared

--18--

the boats and returned them to the buoy again. No officer was allowed to go on shore, nor any person to come on board. One day, as I was drinking beer in the galley, I was taken ill on a sudden, and fell backwards--when I was taken up and carried to my hammock. I was insensible for about 8 hours, when my senses returned; and the doctor asked me how I felt--I told him I had a violent pain in my head and back. He said, "you are young, and likely to get over the fever, if you will mind my directions." The fever broke in about 48 hours, when I was ordered on shore to the hospital, with a few men that had recovered of the fever. We were all put into a sick ward. I recovered very fast; but unhappily had a relapse, by going out and setting on the grass; which made me so crazy, that when the doctor came to give me some physick, I bit him in the hand. However, in the course of three weeks I recovered so as to be able to walk under the piazza. One day walking alone, and reflecting on my unhappy situation, I cast my eyes round and saw two men coming towards me, who proved to be the doctor's mate and the midshipman, who put me on board the guard ship. As they passed by me, the midshipman said to the doctor, "is not that that Davis, which I put on board of the guard ship?" "No," replied the doctor, "he died long since." The midshipman stepped up to me, and clapping me on the shoulder, said, "Davis, is this you or your ghost?" I replied, "it was what was left of me." They left me at that time; but the

--19--

next morning a boat came after me, with the doctor and Lieutenant of the Surprize, who sent a porter for me, to go to them at Mr. Shuffler's office, under the middle sentry. I obeyed the order, and went with him to see the gentleman.

While I was before them, the doctor asked me how I did--To which I replied, that I did not feel very well; but he insisted that I was well enough to go on board with them. I made answer, "gentlemen, I am not well enough to go at present." He then told me I must go on board on the morrow, when they sent the boat for me. The next morning the porter came for me, when I told him, I would go with him, if he would let me get my clothes, which he gave me liberty to do. But instead of returning, I secreted myself behind the chimney until he was gone.

The next morning, while I was at breakfast, he came and took me with him to Mr. Shuffler. "You d--d rascal," said he, "why did you not come yesterday, when I sent for you? I will make you pay dearly for this"--and ordered the porter to call the sergeant of the guard, who soon came, and was ordered to take and confine me in the guard-house. I was taken there, and confined for the space of fourteen days, without provisions or bedding being allowed me--(yet the guard helped me to provisions, or I should have suffered much.) One morning I was looking through the bars of my window, and saw a boat coming to the landing place--and a boy coming near the window, I called, and asked him what ship he

--20--

belonged to? to which he answered, Thetis frigate, then laying in Blocker's hole. I told him to tell his captain that a man wanted to enter on board his ship. The next morning a boat was sent for me from the Thetis, the midshipman of which asked the sentry to let me go with him--The sentry told him to go to the officer and get my discharge. While he was gone, a boat came to the landing place, from the Surprise. The officer finding that both wanted one man by the name of Joshua Davis, told them to go to Mr. Shuffler, and clear up the business, for he could not think that one man could belong to two ships at the same time. On the morning after, while I was laying on the guard board, I felt a sudden pull by the leg. The word was, "get up you rascal, and answer to your captain;" when I soon found who I had to deal with. It was the captain of the Surprise, with Mr. Shuffler--the first of whom said, "Why did you not come on board yesterday, with the midshipman?" My answer was, "the sentry would not let me go without a discharge from his officer." He said, "See that you come on board when I send for you, sir." To which I made no answer. Mr. Shuffler said, "That fellow is a d--d sulky rascal, and ought to be flogged." The captain made no answer, but went out at the door, and Shuffler after him.

About 2 o'clock that afternoon, a boat arrived at the landing place with an officer, who came to the sentry with a written order for my release; with whom I went down to the boat,

--21--

and rowed off. In passing Blocker's hole, we were hailed by an officer from the Thetis, alongside of which we went. The officer and men went on board of her, leaving me in the boat. In a few minutes I heard a voice call me by name, from the gun deck, requesting me to go on board--which I pretended not to hear. "Don't you hear me," says he, "if you do not come up directly, I'll send down a runner and tackle and hoist you up." I went up; and he wished to know if I did not want to enter--to which I made no reply--when he asked me if I was not well. I told him I was not. He then ordered the steward to take me below and give me something to eat. I went down with him to the ward room, and partook of the officers' leavings, which was, polishing the bones. I then went forward among the men; and saw the boy that I called to my window, when in the guard house, who asked me if I came to stay on board the Thetis; to which I replied that I could not tell, and left him. In a few minutes I was called to get into the boat--and was no sooner in than Mr. Lovering, the second lieutenant of the Surprise, said to me, "do you not know in whose hands you are?" I told him yes. "Then why did you enter on board of the Surprise?" I said that I never voluntarily consented to enter on board the Surprise. "Well," says he, "you belong to the ship, and that's enough; now tell me the cause of your entering on board the Thetis." I told him it was on account of Mr. Shuffler sending me to the guard house, and starving

--22--

me there. He promised me that I should be better treated for the future. On entering the ship, Capt. Reves called me on the quarterdeck, and wished to know who had abused me. I said that Richard Grimes had abused me. He asked on what account. I said, "call him Sir, and I will inform you before his face." Grimes was called--and the Captain said, "have you abused this boy?" Grimes replied, "no, please your honour." I asked him, "did you not make me a swab-washer on the ship's waist, and did you not beat me with a suplejack, because I told you I was rated a drummer's boy?" Grimes said if he had done it, he was sorry for it. The Capt. ordered him away, and told him never to abuse me again, or he would be flogged severely--and this was all the satisfaction I got from either of them.

My bed was sent on board the next day, without being smoked; through which neglect I caught the fever again, The doctor ordered me to be put down in the ship's hold, over the water casks, fearing the whole crew should take the disease. In the mean time the ship was got under way to convoy a number of merchantmen to Halifax, N.S. The doctor attended me from day to day--and at times I was very much deranged--in which situation I continued for 21 days, when the fever broke, and I began to recover. In a few days I so far recovered as to go upon deck--and in a few days more we arrived at Halifax. Capt. Reves asked me how I felt--to which I replied that I did not feel very strong yet. He

--23--

said, "my lad, keep up your courage, and I will make a midshipman of you when we arrive in England." I did not place much confidence in what he said, as he had made a similar promise once before; and from that day I was determined to feign myself sick, and accordingly took my hammock. The doctor came and asked me how I felt--when I told him that I had a languid and weak feeling in my stomach. He told the captain that he was afraid I was in consumption. "If that is the case," says he, "he shall go on shore before the ship leaves the harbour.

On the 27th June, the ship sailed for Newfoundland. I was called on deck, and the Captain asked me how I was. "Very weak in the stomack, sir," said I. He said, "not so weak but that you can do duty again; come give us a tune on your fife." I played a tune very faintly--when he said, "you are either d--d weak or lazy, and told me to get my hammock and go on shore with the pilot, to whom the Captain said, "take this Yankee dog to prison"--and turning round to me, said, "get into the boat, and if I ever catch you privateering again, I will hang you on the yard arm." I went into the boat, and rowed on shore with the pilot, who carried me to the house of the commissary of prisoners. This was about 2 o'clock in the morning. We knocked at the door--the commissary looked out of the window, and the pilot told him he had a prisoner, and wished to know what to do with him. He was ordered to put me on board of the Pembroke, a 74 gun ship then lying in the stream.

--24--

I was put on board this ship, and there left alone, until morning; when, on going to the galley, I heard some person cough. I then went to the cooks cabin, and found it fast, but on knocking, somebody asked "who's there?" to which I replied, a prisoner. "Then how in hell came you here," said he. He opened the door, and I told him that the pilot put me on board in the night, from the Surprise, which had sailed from Halifax. "Very well," said he, "will you drink a glass of gin," which I took, and thanked him. While we were talking, there came a number of men on board, to breakfast. They were of the Bonetta's crew, from the dockyard, where she was repairing. I went to the captain of her, and told him I should be glad if he would let the commissary know that I was put on board of the ship the night before, by his order; and that I wished him to send me to prison. This business was neglected for four days, when I asked him again if he had spoken to the commissary for me. "No," says he, "you had better stay on board, than to go to prison." I thought all the time his plan was to keep me in the service--and told him that I was sent from the Surprise on account of my ill health, to go to prison. He asked me what countryman I was. I told him I was an American, and born in Boston--to which he said, "then I will see that you go there." In the afternoon the boat took me on shore. The commissary was standing on the wharf, and said to me, "my lad, I am sorry that I have kept you so long on board the

--25--

ship, without any provision." I told him I should have starved, had it not been for the Bonetta's crew. He told me to go to prison, and I should have my back provisions paid me--but it proved otherwise, for I never received more than my daily allowance the whole time I was there. In about 8 days a cartel was filled out to take us to Boston. Eighty four were put on board, of whom Capt. Ropes, of Salem, was one. We sailed from Halifax on the 7th of July and in six days were in sight of Cape Ann. We saw two boats to the leeward and bore down on them, in order to get some fish. One of our men, by the name of Connor, asked the skippers of the boats if they had any news from Boston, and was told that the frigates Boston and Dean, and Mars ship, were pressing all the men they could find.--Connor called all the people below, and told that if they went to Boston, they would be impressed on board of the ships there; and if they would stand by him, he would take the cartel into Cape Ann that night; to which we agreed. About 4 o'clock in the morning Connor went to the man at the helm, and said, "let me take a trip at the helm," and forced him from it; when he ran directly into Cape Ann,and came to an anchor under the fort. Soon afterwards, a thunder storm came on, and as there was no time to be lost, we got out the boat in order to go on shore. When we got the boat over the side, into the water, she filled, and four men jumped into it, and bailed it out, when it was immediately filled with men, and

--26--

rowed for the shore. The Captain of our cartel hailed the fort, and requested them to fire upon us--but no answer was made to him. As soon as we reached the shore, we sent the boat back for the rest of the people, who all came, except for the officers.

I went to Boston the next day, where I tarried until the 9th of October, when I entered on board of a privateer called the Viper, of 16 six pounders, commanded by Captain William Williams, bound on a cruise off New York.--We sailed on the 22nd of the month; made Sandy Hook on the 28th, and ran on for Philadelphia. We cruised from Cape May to Cape Hatteras, for 12 or 14 days, and experienced gales of wind, and white swells almost every day. One morning a sail was seen to the windward, bearing down for us. When we made sail for her, she hove about, and stood away. Our Captain said she appeared to be a privateer, and a fast sailer, and ordered our ship to be put about, in order to have her come up with us. About 12 o'clock she ranged long side, and hailed us; when we hoisted our colours and gave them a broadside, without giving them any other answer. They then hoisted English colours and gave us a broadside. We continued the fire for half an hour, when she shot ahead of us. Captain Williams ordered the helm aport, and bro't our larboard guns to bear on her, and raked her fore and aft. At the same time our Captain received a musket ball in the breast, and died of the wound in six hours after. He

--27--

was the only person hurt in the engagement. The privateer ran from us in a few minutes afterwards, and in three hours was out of sight. We afterwards found that she was the Hetty privateer, of 16 six pounders, out of New York.

The first Lieutenant then took the command of the ship, and stood for Philadelphia. The next day we saw a ship to the windward of us. We gave chase; at 4 o'clock were along side of her; and hailed her. They told us she was a merchantman, from South Carolina for New York, called the Margarett, and ladened with beef, pork, butter, and porter. We took her safe into Philadelphia--where I quitted the ship, and sold my share of prize money to the sailing master of the Saratoga, of 20 guns, for 4500 dollars (old continental money, it was then about sixty dollars for one) and set out for Boston, in company with John Gow, our serjeant of marines. In seven days we travelled as far as Morristown, then Gen. Washington's head quarters, and tarried there a few days, to see some of our old Boston friends, and to recruit ourselves. In eleven days more we reached Boston, which made it the 24th day of December.

On the 16th of May, 1781, I entered on board of the privateer Essex, of 20 guns, commanded by Capt. John Cathcart, and sailed from Boston on the 22nd of the same month, to cruise off Cape Clear. On the 4th of June, about four o'clock in the afternoon, we discovered a sail directly ahead of us. We had to

--28--

put away, until they hoisted their colours, and when hoisted, we found them to be English. Our captain said he would not attack her, (as she appeared to be a 20 gun coppered ship, and full of men) for fear of spoiling our cruise. She chased us all that night, and in the morning, we found she had carried away her maintopmast, and gave over the chase. We ran on for two days, when the man at mast-head, cried out "a sail," which we stood for, when she made a signal, which we knew, and returned. She came along side of us, and proved to be the Pilgrim, Capt. Robertson, who came on board of us, and informed he had taken five prizes out of the Jamaica fleet. Capt. Robertson, being the oldest commander, ordered our captain to follow him, while they cruised together on the coast of Ireland. The next day both gave chase to a ship to the leeward and came up with her. She proved to be the privateer Defence, of 18 guns, out of Salem, and kept company with us. Next day we gave chase to a brig, which we found to be from Barbadoes for Cork, with invalids, very leaky, and all hands to the pumps; had been taken by the privateer Rambler, from Salem, who gave them passport to go on. The Pilgrim boarded her first, and let her proceed. We afterwards boarded her, and took two six-pounders, and a few sails from them.

Next morning a sail was discovered ahead; the Pilgrim gave chase, and we followed her, (the Defence following us.) About one o'clock another sail was seen on our larboard beam,

--29--

to which we gave chase, and in two hours run her hull down. We soon found that she was too heavy for us; when we hove about, and stood from her. She gave chase, and came up with us very fast; and gave us a shot, which struck along-side, when our captain ordered the quarter-master to pull down the colours. They sent an officer on board, who told our lieutenant, that their ship was the Queen Charlotte, of 32 twelve, and nine pounders, from London. We were all sent on board of her, and put in irons. In the mean time, the Pilgrim got up to the ship we first gave chase to, and by her signal, we perceived her to be the Rambler privateer. The Pilgrim, Defence, and Rambler, all hove too, and saw us quietly taken and carried off.

In two days we arrived at Kinsale, when our irons were knocked off, and we sent on shore, to be confined in Kinsale castle. A few days after, Guillotion, a 20 gun ship, came into the harbour, and took us all on board, confining us in irons, and stowing us away in their cable tier. We lay in that situation nine days, until we arrived at Spithead, on the 26th June, 1781, when we were sent on board the Diligentee, of 84 guns, in irons.

On the 30th of June, I being 21 years of age, called the master at arms, and told him that that day I was free, and desired him to let me buy some gin, to celebrate the day. He said, "you d--d rebel, how dare you ask for gin? you shall not have any," and went from me. A sailor belonging to the ship, said, if I would

--30--

give him some money, he would get me some gin. I gave him half a crown, and he bought the money's worth. Eight of us were confined together by the feet, ranged along on the chests. I drank round to them, until the gin was gone; and feeling pretty merry, told them I would give them a song, if they would chorus me, to which they agreed.

THE SONG.

-

Washington.

Mysterious, unexampled, incomprehensible,

The blundering skemes of Britain, their folly, pride, and zeal;

Like lions how they growl and threat--mere asses have they shone,

And they shall share an asses' fate, and drudge for Washington.

Still deaf to mild entreaties, still blind to England's good,

You have for thirty pieces betray'd your country's blood;

Like Æsop's greedy cur, you'll gain a shadow for your bone,

And find us fearless shades indeed, inspir'd by Washington.

Your deep unfathom'd counsels our weakest heads defeat,

Our children fight your army, our boats destroy your fleet;

And to complete the dire disgrace, shut up within our town,

You live the scorn of all your host, the slaves of Washington.

--31--

Come let us wet our hangers, our cutlasses, and swords,

No justice is expected from commoners or lords--

Nor bribed by ministerial gold, Old-England low will lay,

Arouse, arouse, arouse, arouse, arouse America.

Determined fix the bayonet, and charge the sure fusee,

Resolv'd like ancient Romans, to set our country free;

And by our noble acts perform forever and for aye,

Prove that we are true sons, true sons of brave America.

And when that we have conquer'd them, we'll cut them up like shears,

To swords we'll beat our ploughshares, and our pruning hooks to spears,

And rush all desperate on our foes, nor breathe till battles won,

The shout huzza, America, and conq'ring WASHINGTON!

The song was overheard by the master at arms, who said to me, "you d--d rascal, how dare you sing such a rebel song on board of his majesty's ship? If I hear you sing that song again, I will gag you."

In about eight days we were sent on board a tender, and ordered to Plymouth, (Mill Prison.) We were 132 in number, and all put into the press room. Mr. M'Lane, our boatswain, called to the man on deck, and asked him to put down the wind-sail, or we should all die; which was accordingly complied with, and every man ran to get under it. Mr. M'Lane advised us to take off our clothes, and

--32--

lay as near the sail as possible. After the tender got under-way, Mr. M'Lane said to us, "if you will mind me, I will take the tender tonight; go to work, and make saws of your knives, and we will saw off the nails of the bulk-head, so as to get upon deck, and take the vessel and carry her to France. It was agreed to, and every man went to work, and singing, in order to drown the noise of the knives. About one o'clock that night, we heard the men on deck say "we shall be in Plymouth Sound in a few minutes, if the wind does not fail us." We got the bulk-head down, in order to go on deck, but to our great surprise, the hatckway was battered down so hard that we could not force it up. While we were contemplating what was next to be done, we heard the anchor drop.

July 11th, about eight o'clock in the morning we went to Mill Prison. When we had been there three weeks, a sergeant of the guard came into the prison yard, and ordered us to come forward, and answer to our names. He called over 82 names, of which mine was one; and directed us to prepare ourselves against the morning, to go on board a Cartel for France, for an exchange of prisoners. Those that had to stay behind, employed the night in writing letters for us to take to America, for their friends.

The next morning the sergeant came into the yard, and called our names over. We were escorted by 30 soldiers, to Plymouth-dock. In going through the town, a servant

--33--

came to the door of a large house, and ordered the sergeant to holt; which he did, and carried six of the prisoners in, who never returned. I being called in, was interrogated by a man in an arm-chair, with respect to the place of my birth, the name of the vessel I sailed, and was taken in, &c. I told him that I was an American; sailed in the Essex privateer, of 20 guns, commanded by Capt. John Cathcart; had been three weeks on the cruise; and were taken by the Queen Charlotte, and carried to Kinsale. Every one of us were questioned in a similar manner--when we were ordered to the landing place. I sat down on the capson of the wharf, where a number of boats came up. An officer said that six of us must go into each of those boats, which we did accordingly. The six to which I belonged were carried on board the Lynix, a 74 gun ship, and ordered to go down to the Steward's room, and get our provisions. The first lieutenant, Mr. Robertson, said to the first master's mate, "see that those men are put in different stations about the ship." One man was put in the forecastle, another in the foretop, the third in the maintop, the fourth in the mizentop, the fifth in the waist, and myself in the after-guard; after which we were put into different messes. As I was going one day to the galley, to get my allowance, one of my fellow prisoners said to me, "is it not a d--d shame that we cannot mess together?" The third lieutenant passing by, heard what he said to me, knocked him down and said "you yankee rebel, you want

--34--

to breed a mutiny in the ship. If I ever hear you speak to to the yankees again, you shall be tried by a court martial.

Nov. 18. Our ship dropped down to the Sound a few days after, and lay there three weeks, waiting for sailing orders, which we finally received, to go to Cork, and lay there as a guard ship, where we arrived in four days, and came to an anchor. In a few days after, Admiral Rodney, in the Formidable of 98 guns, came into the Cove, in company with the Fordrogant, Courage, Monarch, Bedford, and Fortitude, 74's, and Anson, 64, in order to get men. Capt. Blair of the Anson, came on board of us, and made a draft of men. I was ordered with 19 others, to go on board the Anson--and the first fair wind we sailed from the Cove of Cork for the West-Indies. Nothing of consequence happened during the voyage, and in 34 days we arrived safe at Barbadoes.

While we were taking in provisions, Count DeGrasse came off the harbour with 28 sail of the line, and blockaded us for a number of days--when we left the harbour's mouth and we made sail for Jamaica, to join Adm. Hood, with 24 sail of the line. We waited there several days, making ready to go out and meet the enemy--and finally sailed from Port Royal, and beat to the windward a number of days. On the 9th April, while running between Martinico and Guadaloupe, Adm. Hood's Squadron got becalmed off the harbour; and wind springing up suddenly from the shore, the French fleet, then lying in Martinico harbour,

--35--

took the advantage, got under way, run out, and attacked the rear of the fleet, which made great slaughter and confusion in our ships.--Admiral Rodney gave out a signal for his squadron to heave about, and stand in shore of the enemy, and cut them off. The French Admiral saw our design, ran into the harbour, and got clear. Our fleet then stood to the northward, in order to repair our crippled ships. The next day we changed our course to the southward--and on the morning of the 12th, a fleet was discovered to the southeast of us. A signal was given, from Admiral Rodney's ship, to give chase, and by 8 o'clock we were within two gun shot to the windward of them. We drew up in line of battle--the enemy doing the same--every ship in both fleets, clear for action. Cows, sheep hogs, ducks, hencoops, casks, wood, &c. were seen floating for miles around us. We bore down upon the French fleet, and commenced the action. It raged with the greatest fury for four hours, when it became calm, and we could scarcely see for smoke. Both fleets discontinued firing for about two hours. In the meanwhile our captain ordered the boatswain to pipe for dinner, and served out grog to all hands--but the galley having been taken down and sent below when the action commenced, we had no fire to cook our dinner with--on which account the steward served out raw pork and bread.

At 2 o'clock the smoke was entirely cleared off, and the action was renewed with redoubled fury. Our ship had an 84 gun ship on the larboard

--36--

quarter, and a 74 on our starboard bow, for the space of 20 minutes, when the Alfred, a 74, bore down on the 84, and relieved us of one of them, by giving the 84 a whole broadside, which carried away her maintopmast, main stay sail, and cut their rigging so bad, that they fell to the leeward to refit; the Alfred followed her, and gave her another broadside, which carried away their foremast, when she struck to the Alfred.

I was ordered to attend the signal officer on the poop of the ship. While I was waiting his orders, a shot came in over the taffrel, and killed two marines, wounded the officer in the arm, and went through the ship's side. Another shot struck Capt. Blair in the side, which cut him entirely in halves, when the first Lieutenant ordered the men to take his remains, and throw them overboard. We continued fighting under the command of the first Lieutenant, until a shot took his leg off, and he was carried below to the doctor. The command then devolved on the second Lieutenant. In about 15 minutes we shot away the enemy's mizen mast; when she wore away under our stern, and we bore away after her; but our rigging was cut so bad that we could not come up with her, until we had to repair it. I was ordered into the fore-top to help the men splice the rigging. In a few minutes after I got into the top, I heard a terrible explosion, which proved to be a French 74, that had blown up, after she was taken. When we got up with our French ship again, it was nearly sunset. We kept up a running fight about

--37--

one hour, when a small ball struck me in the leg. I went down to the doctor, who dressed it, and told me it was not dangerous, as it had only cut one of the sinews. In three weeks I was well enough to go on deck. After the engagement was over, Adm. Rodney ordered the fleet, with their prizes, to go to Port Royal, in Jamaica, where we soon arrived. The ships taken were, the Ville de Paris, of 110 guns and 1300 men; Le Glorious, Le Caesar, and Le Hector, of 74 guns each, and Le Ardent of 64 guns; one 74 guns blew up after being taken; Le Diadem sunk in the action.

An officer came on board the Barfleur, Adm. Hood's ship, and composed the following song, in honour of the victory gained over the French fleet, by Ad. Rodney, on the 12th April, 1782, and which was sung by our officers on board of the Anson.

SONG.

Tune--ARETHUSA.

It was in the year of '82, the Frenchmen knew

"full well it was true,"

When Rodney did their fleet subdue,

Our Admiral then he gave command

That we should by our quarters stand,

Says he, for the sake of Old England

--38--

The Frenchmen then they did combine

To draw their shipping in the line;

To sink our fleet was their design,

The Formidable, she acted well,

Commanded by our Admiral;

The old Barfluer none could excell--

The action we so long maintain'd,

Five captur'd ships we did obtain;

And hundreds of their men were slain,

Now may prosperity attend

Brave Rodney still, and all his men,

--39--

After being in harbour two months, repairing our crippled ships and prizes, and waiting for the windward fleet of merchantmen to come down, for us to convoy them home to England, orders came on board from the Admiral, to shift the men from ship to ship, on account of so many men having been killed and wounded in the engagement. I was drafted on board the Diamond frigate, of 36 guns, commanded by Capt. Roberts. In August, the whole fleet got under-way, and run out of the harbour, I believe there never was a larger fleet ever sailed out of the West-Indies before, they appeared like wood for miles around us. The third day after we sailed, a dreadful hurricane came on about two o'clock in the afternoon. All hands were employed in taking in sails, and striking yards, and topmast. We put away before the wind, and run under bare poles, at the rate of eleven knots an hour. Next morning not one of the fleet was to be seen. About eight o'clock that night we shipped a sea over our taffrel, which carried away our stern lanterns, and hencoops, and stove in the cabin windows, filling our waist so full of water that it ran down between decks, and

--40--

forced the people on deck as fast as possible, for fear of drowning. We were ordered to the winches, to clear the ship of water; and were two days before we got her entirely free, when the gale abated enough for us to get a foresail set. The wind had been S.W. four days, when it shifted N.W. and blew so hard that we had to put away again, and take in the foresail, in which condition we run six days, when the weather became calm again. Our ship rolled to such a degree that we were obliged to heave the waist guns overboard, to ease her. The fore-shrouds being rather slack, the foremast sprung, and before we could set them up, it went over the side; when we cut away the shrouds, and let it go. Next morning, the wind sprung up from the westward. We crouded sail on the main and mizen masts, and in nine days arrived safe in Plymouth sound. Our ship lay in there until the peace took place, when we were ordered into the harbour to be paid off, and when paid, I went to London in the stage, where I met with Capt.Scott of the ship Neptune, of Boston, and requested him to let me take passage in his ship for Boston. He told me he had so many passengers engaged, that he could not any way accommodate me. I asked him if there were any other Americans in the river; to which he replied there were not. I returned to Plymouth again, and went on board the king's tender, bound to Cork, with a number of men belonging to Ireland. The second day after our departure, on going round the Land's End, the

--41--

wind being so far north, we were obliged to put into Kinsale for harbour. On arriving there, 64 men, belonging to Ireland, went on shore. I thought it best to go with them; and went to Cork, in company with Frederick Blanchard, of North Carolina, and John Ryan, of Dublin. We stopped at the half-way house to take breakfast, and then went on. On rising a hill, we saw two men coming towards us, (Ryan and myself kept together, and Blanchard about 20 yards behind.) When we got up to them, they said, "what ship?" (we supposed they wished to know what ship we belonged to) to which we answered the Diamond frigate. "Then," said they, "deliver your money, or you are dead men," and drew pistols from their pockets, and presented them to our breasts. While we were taking our money from our pockets, Blanchard came up, and gave Ryan a push with his left hand; and struck the man that held him on the head with the butt end of a stick, which knocked him down. Ryan stood still--Blanchard turned, and ran back--the man that was knocked down, got up and took hold of Ryan again, saying, "now deliver your money directly;" at the same time firing a pistol at Blanchard, which missed him. We gave them our money--when they told us "to go to hell." They made a spring over a hedge, and ran down the hill. On looking round, we saw Blanchard in the hands of two more men, who robbed him of his all. Blanchard lost 23 guineas, Ryan 20, and myself 36, which was all either of us had!

--42--

Reader imagine what must have been my feelings at that time! Thus left in a strange (though hospitable) country--without money--without friends of whom I could demand any thing--without clothing--and but little prospect of ever seeing my native country again!--which me call to mind the Galley Slave--

"Hard, hard is my fate, oh how galling my chains, My life's steer'd by misery's chart."

There was no time to be lost--and I proposed to my friends, (who stood speechless by me, that we should go back to the half-way house, and tell the landlord of our misfortunes. There happened to be a number of horsemen at breakfast in the house, going on to Cork--to whom the landlord told our story. They instantly got up, mounted their horses, and went up the hill, (we followed them.) After looking and searching round for about two hours, and finding nothing of them, returned to the house again.

In a few minutes, about 40 men from the Kensale came in, who came over with us in the tender, to whom we made known our destitute situation; when they made a contribution among themselve, which amounted to 13 guineas, and of which I had better than four for my share. After we had taken some refreshment, we traveled on to Cork, where we all parted company, for different parts of Ireland. Blanchard and myself kept together for some

--43--

days, hoping to find a vessel bound for America, but could find none either in Cork, Passage, or Cove--and concluded to work our passage to London, in a vessel bound there. In sailing up the channel, the wind being directly ahead, and blew so hard, we had to put away, and run into Plymouth. I went on shore, and happened to meet a man by the name of Brannon, one of my old shipmates on the Anson, who advised me to enter on board the Æolus frigate, of 32 guns, bound to St. John's Newfoundland, where I could get away from her, and go home, I went on board that afternoon, and entered--and in a few days we dropped down the Sound, when the king's yacht came alongside, and paid us two months wages in advance.

May 24th,--we set sail, in company with the Echo, sloop of war, of 16 guns, Capt. George Robertson. After a passage of 18 days we arrived at St. Johns. One Sunday our captain gave a number of the people liberty to go on shore, and I happened to be one of them that had liberty to go on shore. I went on board a schooner, the captain of which told me he was bound to the Bay of Bulls. I offered him six dollars if he would let me go there with him. He asked me if I was not a man-of-war's-man--to which I replied that I was. "Then you cannot go with me," says he. I told him if he would let me go with him, I would stow myself away under the wood in the hold. He was about concluding, when an officer came into the cabin, and asked me how I came

--44--

there, and ordered me on board the ship. I went on deck, and he told me to go with him on board, with the remainder of our men. We got under way as quick as possible, and run down to a place called Fogo, on the Musquito shore, in order to assist in getting the Echo off the rocks, which she run on in going into the harbour. By the assistance of some fishermen from the shore, she had been got off before. We hove about, and stood for St. Johns again. Next day, Sept. 22, a gale of wind came on, and all hands were employed in taking in sail. I was sent forward with two men to take in the fore-sail. When at the gangway, to windward, a sea struck the ship on the beam, and all three were hove into the ship's waist. One man broke his leg; the other put his arm out of joint; and I fell on the shot lockers, and knocked out two of my teeth, and stunned myself. I was taken down to my hammock, and on recovery was ordered on deck to do duty.

The wind blew very hard that night, and in the morning it came round to the northward, when we ran into St. Johns.

Oct. 4--our ship was ordered to Lisbon, in order to get money from the Queen of Portugal, called protection money, due to the King of Great Britain. Our captain took in salt, lines, hooks, &c. that we might catch some fish on the Banks of Newfoundland; and on getting there we caught and salted down so many, that we were obliged to stow them under

--45--

the half deck. We generally dried them on the quarter deck and forecastle.

One day a sudden squall struck us, and hove the ship on her beam ends; when two of the main deck beams gave away; the fish under the half deck fell in between decks, and killed a sick man laying in his hammock. We had to throw fifteen hogsheads of fish overboard, and repair the deck.

On the morning of the 8th Nov. we arrived at Lisbon, and our Captain was busily employed every night in smuggling his fish on shore. One evening, about 8 o'clock, the hands were piped to hoist in a large iron chest, which contained the money, and which was put into the Captain's cabin. Next day, we took in 42 pipes of wine, and stowed them away in the after-hold. In the night all hands were employed in starting about 30 hogsheads of water in the main-hold, and pumped it out as quick as possible. All hands were ordered to go on shore in the boats, and bring anchors of wine on board, which was put into the empty water hogsheads, and the anchors sent on shore again.

The boats were then taken on board, when we made sail, and stood to sea. In crossing the Bay of Biscay--one night, after the middle watch had been called, the gunner's mate, of the morning watch, went to examine the gun rigging, and found 8 guns on the weather side cut away; and before the watch could get on deck to secure them, two guns broke away, and run to leeward with such force as to

--46--

brake away the lee side, and make the upper works take in water so fast that we had to batten down the hatches. In a few minutes the ship's waist was filled with water; when the Captain ordered a number of hammocks bro't up, and stuffed into the side, to stop the leak, which was soon done, when the water ran out of the scupper holes, and the ship cleared.

We ran up the channel, and on the 2d Dec. arrived at Chatham, England. The iron chest was taken out, and sent on shore under a guard of marines. That night the purser told the steward to give the custom-house officers as much liquor as they could drink. He took them down to his room, and gave them a good supper, and handed them drink so plentifully that they were soon intoxicated, when they fell asleep. The main hatchway was then opened, and all the wine hoisted up, and sent on shore.

In a few days the King's yacht came alongside, and paid off the people, when paid, I went on shore, and took stage for London, where I made enquiry at Lloyd's coffee house, for a vessel bound to Boston, and was told that Capt. Folger was in the house, at dinner. I waited until he came into the bar-room, when I asked him to let me go to Boston with him. He said, "I wish I could, my friend, but there is so many passengers already engaged, that I cannot take any more." I then asked him if there were any other American vessels in the river; to which he replied he did not know, and turned from me. I made several inquiries afterwards,

--47--

but could hear of nothing--and here I was put to my trumps one more--What to do, I did not know; my money would soon be gone, if I staid in London. I therefore concluded to go to Chatham, and enter on board a guard ship, that I might be handy to London, and go there when and as often as I pleased, to get a passage home with some captain, that had feeling for his countrymen.

I accordingly went down to Chatham, the next day, and entered on board his majesty's ship Irresistible, Com. Andrew Snape Hammond. Nothing of consequence took place for one year; when the king's Yacht came along side, to pay the ship's company: I received six months wages, and six months kept back; and the next day got liberty to go up to London, where I renewed my inquiry for Boston vessels, and was told that Capt. Kellehorn's ship lay at the Bell-wharf stains. I went on board, and the captain invited me into the cabin, when I asked him to let me have a passage with him, and I would give him seven guineas. He said the cabin and steerage were filled with passengers, who had given him 30 guineas each, and could not take another. He offered me some grog, which I refused, and left him; and went aboard my ship at Chatham. In six months after, we were paid of again, when I set out for London, once more. I went to the widow Bell's, and inquired for a vessel bound to Boston. She told me that Capt. Davis boarded in her house, and would be home to dinner in about an hour. When he came in, I went up to him, and said,

--48--

"how do you do, namesake." He smiled, and said he did not know me. I said "if you do not know me, you know my father--he lives in Boston, and is a hair-dresser;" when he said he knew him very well. "Sir," said I, if you know my father, I wish you would take me home to see him. He asked me what employment I was in; I told him that I belonged to a 74 gun ship, then lying in the river Medway, and had been up to London several times, trying to get a ship to carry me home. He asked me to whom I had applied. I said, to Capt. Folger, Capt. Scott, Capt. Kellehorn, &c. "And could you not get a passage of either of them?" says he--to which I told him no. "I pity you," said he, "and wish I could give you a passage with me, but I have more passengers now than I know what to do with, or know where to stow." When he said this, I turned round, and said, "I suppose I must go back to my ship again"--to which he said, "I suppose you must--good bye."

My readers may guess what my feelings were at that time, to hear a man (a customer of my father's) talk so careless and unfeeling to a fellow-countryman and townsman in trouble and distress.

However, I was determined to go back to the ship again, and there stay until another opportunity should offer to go home. I staid on board the ship 12 months longer, in which time nothing of note transpired. At the end of the year, we were paid six months of our wages, when I got liberty to go to London; and on

--49--

arriving there, I went to the widow Bell's, (where I had been the year before) in search of a Boston vessel. I was told by the widow that Capt. Scott and Capt. Kellehorn had been there, but both had sailed about a week before--and did not know of any other vessel for Boston, in the river.

I went back to the ship once more, like a dog returning to his vomit. About nine months after, Mr. Wescott, our first Lieutenant, came on board, and informed Mr. King, the second Lieutenant, that a disturbance had broken out in Holland, between the Prince of Orange and the people; and that our ship was to be got in readiness for sea as quick as possible. I asked leave of the Lieutenant to let me go up to London--which he granted, but bid me not to stay more than three days, because the ship was going to sea in a short time. I went to the widow Bell's once more, in hopes of finding what I long desired, (a passage home.) She told me that Captain Cushing boarded with her, and would be home to dinner. I waited about two hours, when he came in, and I told him, I had something to communicate to him. He told me to sit down, saying, "I believe I have seen you before, to which I replied, "yes, sir, at Master Proctor's school;" that my name was Davis, and belonged to a King's ship in the river Medway, and had been there three years and four months. He asked me if I did not want to go home--I told him that was what brought me to London. He then said I might go with him, but as he had

--50--

just arrived, he did not expect to get away in less than two months. I told him I wanted to get the wages due me from the ship, and must contrive some plan to get them. There were due me 13 guineas from the King, and 6 from the purser. He said it was a pity to loose it--and after a few words more we parted, saying "don't let me go away without you."

I went on board the ship the next day, where I found everything in confusion. The ship was built by contract, and had lain in the river only four years. When the carpenters knocked away the knees of the upper deck, they were all found to be rotten, which took some-time to replace them. I was determined to quit the ship as quick as I could, and formed a plan accordingly. I went to my messmate, (Mr. John Reves, of Philadelphia, and captain of the hold) and told him my plan was to feign myself sick, then go to the hospital, and get discharged. He said I could not deceive the doctor--but I told him I would, if he would assist me--he said he would all he could. I told him I would go to my hammock, drink a pint of vinegar a day, rub allum on my tongue to make it white, and rap my elbow against the ceiling to make the pulse beat. Reves said it was a good plan, if it did but take. I accordingly took to my hammock, and sent for the doctor's first mate. He came to me, and took hold of my wrist, saying my pulse beat quick; then told me to put out my tongue, and said, "I appeared to have symptoms of fever; have you any pains?" I told him I had pains in my

--51--

back and head. He left me a few minutes, and returned with a liquid, which he gave me to take. I filled my mouth with it, and turned round, to go to sleep. Says he, "you will feel better after this," and went away--when I spit out his medicine. Next morning he brought the doctor with him; when I saw him coming, I knocked my elbow again, put allum on my tongue, and quivered my limbs. He took hold of my wrist, and turning round to his mate, says, "this man has got a fever and ague on him, and must be sent to the hospital to-morrow. The next morning I was ordered to go into the boat--and my appearance, I think, was rather singular; I had a large great coat on, full of holes, and dragging behind me full 6 inches; an old black handkerchief on my head, and led to the boat between two men. On getting into the boat, the officers said, "David, you will hardly weather this." To which I replied, "I do not know whether I shall or not." When I got to the hospital, I went to the keeper of the place, and asked him in private whether he knew, if I bribed the doctor's mate, I could get my discharge. "Yes," says he, "I will insure your discharge if you will give me half a guinea." The doctor's mate came to me and asked how I did. I told him I should feel better after I had little of his assistance--to which he said, he would help me all he could--when I told him all my plan. He said I should have my discharge for one guinea, which I agreed to give him--when he told me there would be a discharge in a few

--52--

days. One morning, (about five days after) Dr. Dean, of Rochester, the doctor of our ship, the doctor of the Dictator, the doctor of the Scipio, and our commander, with two post captains, and a number of doctor's mates, came to the hospital, and ordered us all, to the amount of 48 men, to come and be examined--they discharged us singly. I was called in, and asked how I felt. I said I felt very weak at the stomach. The doctor turned to the gentlemen, and said, "This man has a high fever, and the consumption, and ought not to go to sea;" when I was ordered out of the room. Immediately afterwards the doctor's mate came to me, and said, "Well, my lad, I have got a discharge for you, and next Friday you and all the men discharged, must go with me down to the dockyard, at the Commissioner's office, and get your money." The next day a number of us, that were discharged, took off our hospital clothes, and put on new ones, and went into the fields to recreate ourselves; and a dear recreation it proved, for as we were getting over a hedge-stile, we perceived the doctor's mate and two mid-shipmen, who turned round and took particular notice of us. They went on board, and told the lieutenant a very plausible story. The next morning an officer came into our room, and ordered 15 of us to follow him. There was no chance of getting off, so we had to comply with his orders, and go on board. Mr. Wescott, the first Lieutenant, said, "You damn'd deceitful rascals, I'll take care that you do not take the

--53--

doctors in again," and called the master at arms, who came, and was ordered to put us into irons--and we were accordingly put into irons by the feet. The next day our Commodore came on board with a number of ladies and gentlemen to see the ship; on passing us, the Commodore's Lady asked him what we had done, that we were confined in irons? he told her that we had deceived the doctors. On her inquiring what was to be done with us, he replied "They must be punished for it.["] She said "I pity them." An Irishman that was in irons with us, says "God bless you Madam; I hope you will live to bless the Commodore all the days of your life." In about ten minutes Mr. King, the second lieut. came down with the master at arms, and said to him, "Take these men out of irons, and let them go to their stations again." Our irons were then knocked off, and we ordered by the boatswain to go to work. The ship being nearly ready for sea, I was determined not to go in her, at the risk of my life; and was contriving another plan how I should get out of her.

The day before we sailed, a number of pressed men were brought on board, and put into different divisions. The second division had to row the guard that night. When they were called upon to answer to their names, I took particular notice of one of the men, who was called out to row in the second watch. After the officer had discharged the division, I went up to the man, and told him he had to

--54--

row the boat that night, and asked him if he knew how--to which he said no; when I offered to do it for him, if he would lay in his hammock when the second guard boat's men were called, and I would answer to his name. He wished to know why I wanted to do it for him--I said "because I have a good reason for it; we were to sail early in the morning, and my clothes were all on shore; if he would let me do his duty in the boat, I would bring some gin on board, and treat him; to which he immediately consented.

About 2 o'clock in the morning, the guard-boat men were called. I ran down the ladder first, and took the bow oar; the cockswain then came down with a lanthorn in one hand, and a purser's bread bag in the other, which were put in the stern sheets. The Lieutenant came into the boat, and ordered us to put off. As we were rowing up the river, the shipping hailed us--to which the cockswain answered "The guard-boat," and were so hailed until we got as far as Rochester Bridge, when the officer ordered the cockswain to put the boat away, and go on shore at a place called Midshipman's Hard. As soon as the boat struck the shore, the officer jumped out, and told us to stay by the boat, as he should return in 20 minutes. We waited some time for the officer's return; when one of the men of the boat asked the cockswain to let us go on shore and get some gin, which he refused. Another said that he would stay by the boat while the rest went up, if we would send him down some

--55--