The Navy Department Library

THE AFGHAN WARS

1839-42 and 1878-80

by

Archibald Forbes

With Portraits and Plans

CONTENTS

| PART I.--THE FIRST AFGHAN WAR | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | PRELIMINARY, | 1 |

| II. | THE MARCH TO CABUL, | 14 |

| III. | THE FIRST YEAR OF OCCUPATION, | 32 |

| IV. | THE SECOND YEAR OF OCCUPATION, | 49 |

| V. | THE BEGINNING OF THE END, | 60 |

| VI. | THE ROAD TO RUIN, | 90 |

| VII. | THE CATASTROPHE, | 105 |

| VIII. | THE SIEGE AND DEFENCE OF JELLALABAD, | 122 |

| IX. | RETRIBUTION AND RESCUE, | 135 |

| PART II.--THE SECOND AFGHAN WAR | ||

| I. | THE FIRST CAMPAIGN, | 161 |

| II. | THE OPENING OF THE SECOND CAMPAIGN, | 182 |

| III. | THE LULL BEFORE THE STORM, | 202 |

| IV. | THE DECEMBER STORM, | 221 |

| V. | ON THE DEFENSIVE IN SHERPUR, | 253 |

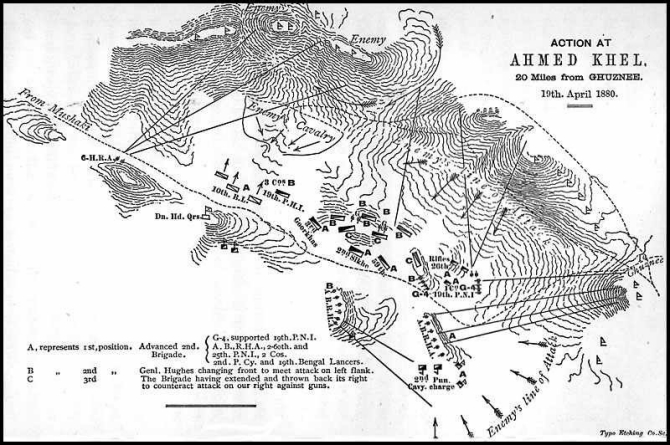

| VI. | AHMED KHEL, | 266 |

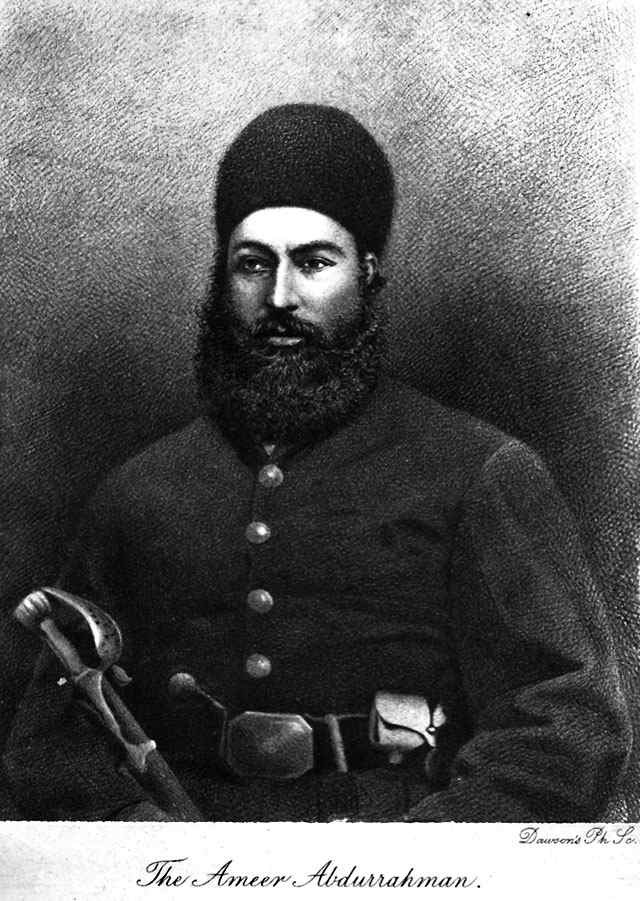

| VII. | THE AMEER ABDURRAHMAN, | 277 |

| VIII. | MAIWAND AND THE GREAT MARCH, | 292 |

| IX. | THE BATTLE OF CANDAHAR, | 312 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS AND PLANS

| Page | |

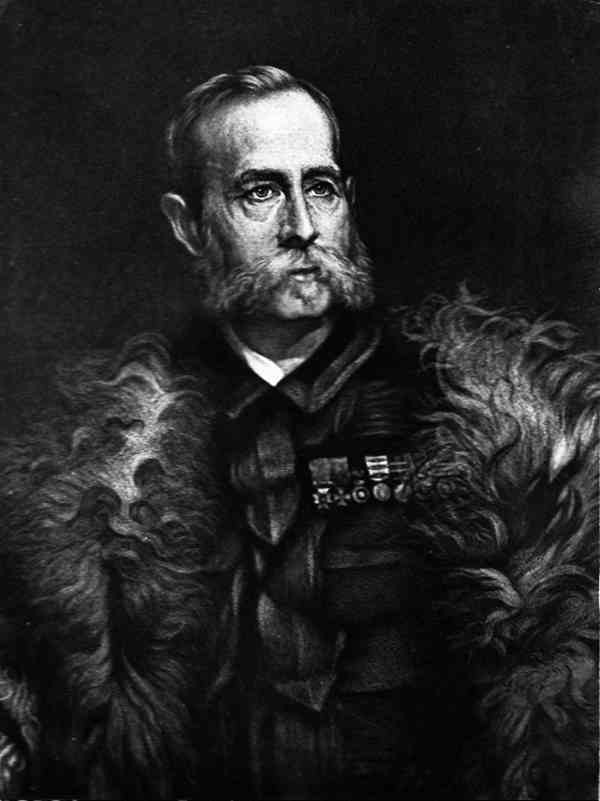

| PORTRAIT OF SIR FREDERICK ROBERTS, | Frontispiece |

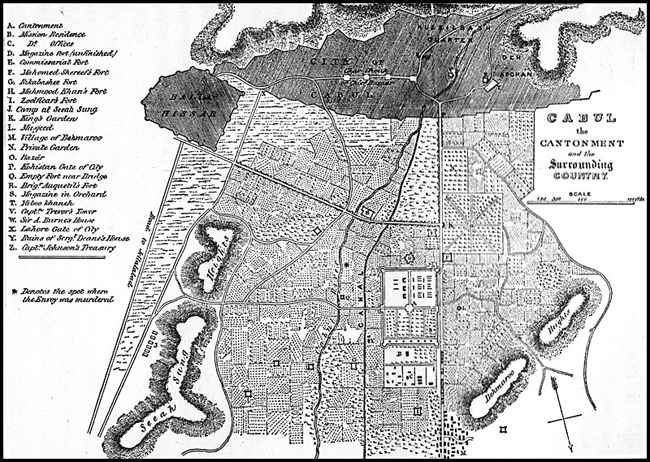

| PLAN OF CABUL, THE CANTONMENT, | 71 |

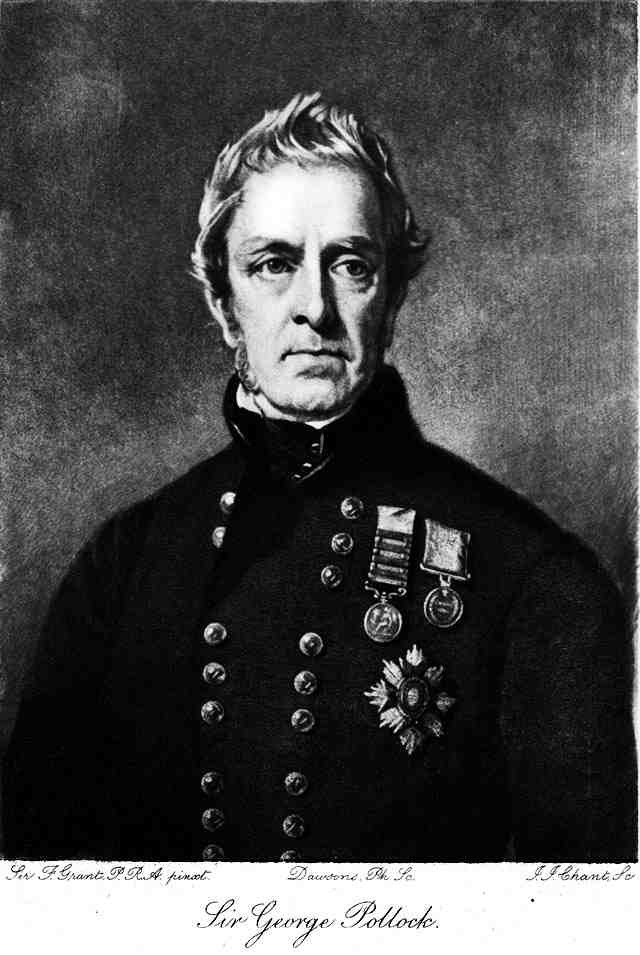

| PORTRAIT OF SIR GEORGE POLLOCK, | to face 136 |

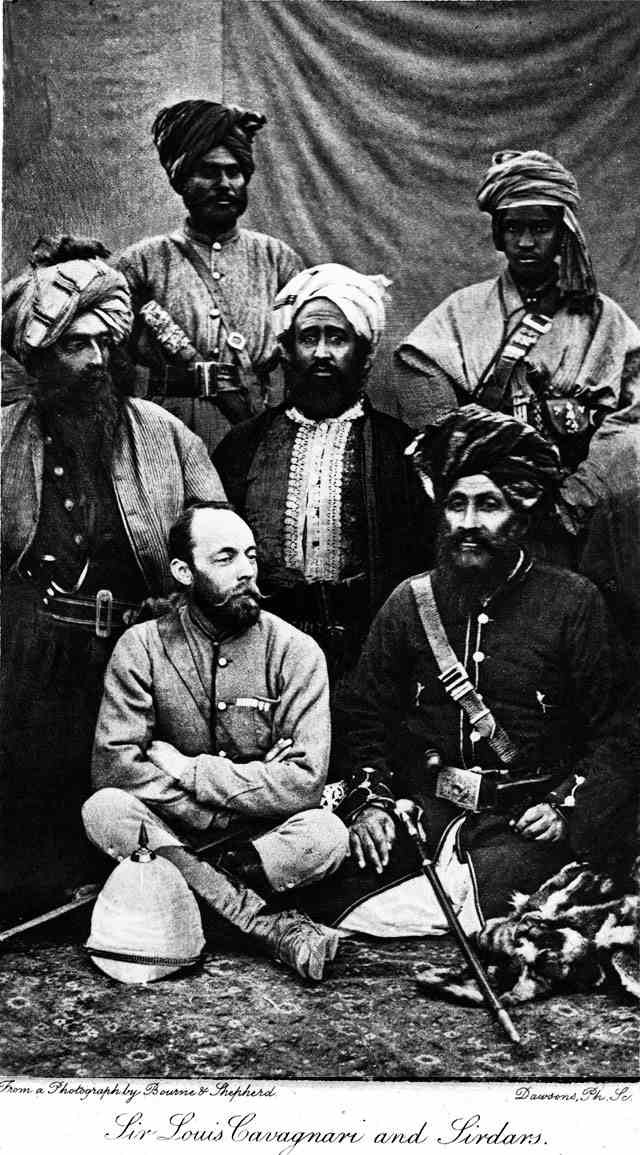

| PORTRAIT OF SIR LOUIS CAVAGNARI AND SIRDARS, | to face 182 |

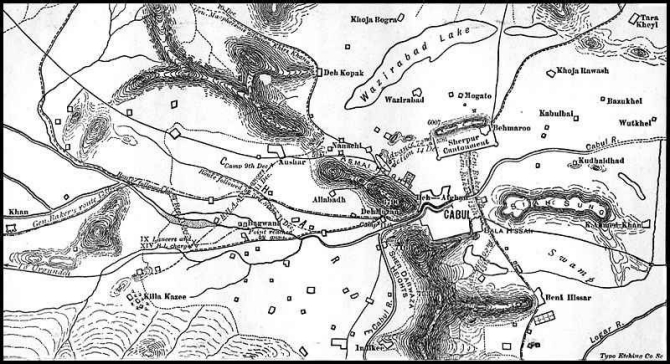

| PLAN OF CABUL SHOWING THE ACTIONS, DEC. 11-14, | 227 |

| PLAN OF ACTION, AHMED KHEL, | 267 |

| PORTRAIT OF THE AMEER ABDURRAHMAN, | to face |

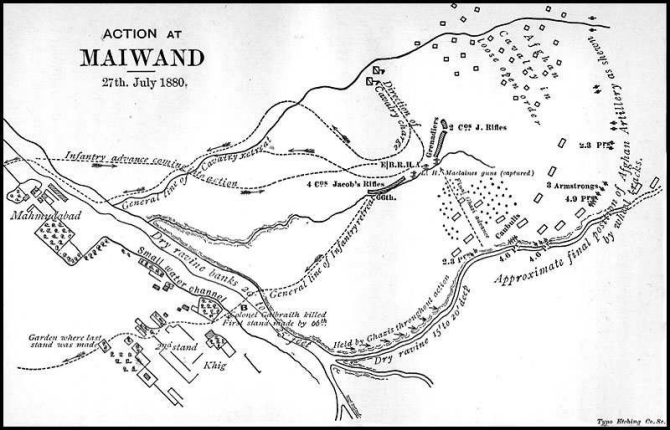

| PLAN OF THE ACTION OF MAIWAND, | 293 |

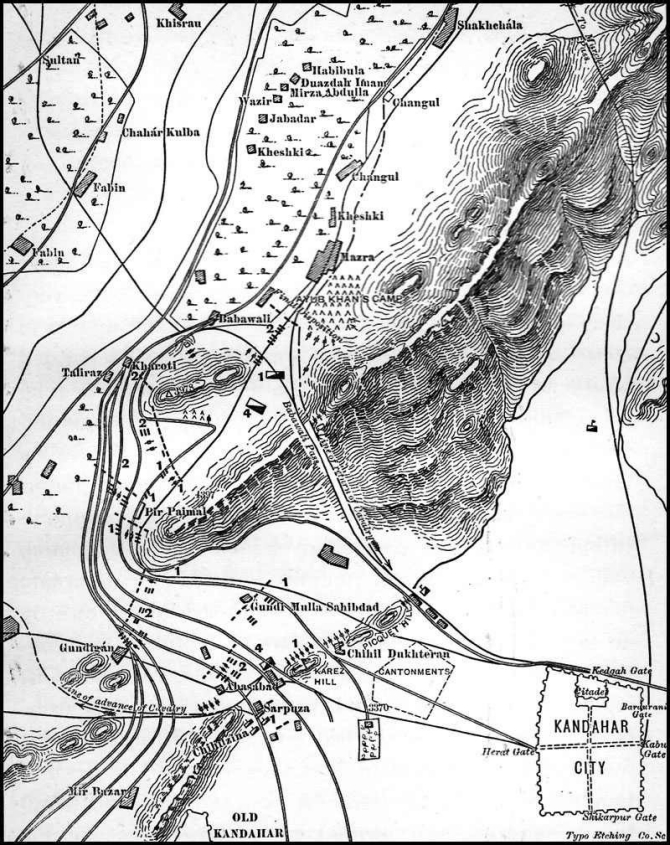

| PLAN OF THE ACTION OF CANDAHAR, | 314 |

The Portraits of Sir G. Pollock and Sir F. Roberts are engraved by permission of Messrs Henry Graves & Co.

THE AFGHAN WARS

PART I

THE FIRST AFGHAN WAR

CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARY

SINCE it was the British complications with Persia which mainly furnished what pretext there was for the invasion of Afghanistan by an Anglo-Indian army in 1839, some brief recital is necessary of the relations between Great Britain and Persia prior to that aggression.

By a treaty, concluded between England and Persia in 1814, the former state bound itself, in case of the invasion of Persia by any European nation, to aid the Shah either with troops from India or by the payment of an annual subsidy in support of his war expenses. It was a dangerous engagement, even with the caveat rendering the undertaking inoperative if such invasion should be provoked by Persia. During the fierce struggle of 1825-7, between Abbas Meerza and the Russian General Paskevitch, England refrained from supporting Persia either with men or with money, and when prostrate Persia was in financial extremities because of the war indemnity which the treaty of Turkmanchai imposed upon her,

--1--

England took advantage of her needs by purchasing the cancellation of the inconvenient obligation at the cheap cost of about £300,000. It was the natural result of this transaction that English influence with the Persian Court should sensibly decline, and it was not less natural that in conscious weakness Persia should fall under the domination of Russian influence.

Futteh Ali, the old Shah of Persia, died in 1834, and was succeeded by his grandson Prince Mahomed Meerza, a young man who inherited much of the ambition of his gallant father Abbas Meerza. His especial aspiration, industriously stimulated by his Russian advisers, urged him to the enterprise of conquering the independent principality of Herat, on the western border of Afghanistan. Herat was the only remnant of Afghan territory that still remained to a member of the legitimate royal house. Its ruler was Shah Kamran, son of that Mahmoud Shah who, after ousting his brother Shah Soojah from the throne of Cabul, had himself been driven from that elevation, and had retired to the minor principality of Herat. The young Shah of Persia was not destitute of justification for his designs on Herat. That this was so was frankly admitted by Mr Ellis, the British envoy to his Court, who wrote to his Government that the Shah had fair claim to the sovereignty of Afghanistan as far as Ghuznee, and that Kamran's conduct in occupying part of the Persian province of Seistan had given the Shah 'a full justification for commencing hostilities against Herat.'

The serious phase of the situation for England and India was that Russian influence was behind Persia in this hostile action against Herat. Mr Ellis pointed out

--2--

that in the then existing state of relations between Persia and Russia, the progress of the former in Afghanistan was tantamount to the advancement of the latter. But unfortunately there remained valid an article in the treaty of 1814 to the effect that, in case of war between the Afghans and the Persians, the English Government should not interfere with either party unless when called on by both to mediate. In vain did Ellis and his successor M'Neill remonstrate with the Persian monarch against the Herat expedition. An appeal to St Petersburg, on the part of Great Britain, produced merely an evasive reply. How diplomatic disquietude had become intensified may be inferred from this, that whereas in April 1836 Ellis wrote of Persia as a Russian first parallel of attack against India, Lord Auckland, then Governor-General of India, directed M'Neill, in the early part of 1837, to urge the Shah to abandon his enterprise, on the ground that he (the Governor-General) 'must view with umbrage and displeasure schemes of interference and conquest on our western frontier.'

The Shah, unmoved by the representations of the British envoy, marched on Herat, and the siege was opened on November 23d, 1837. Durand, a capable critic, declares that the strength of the place, the resolution of the besiegers, the skill of their Russian military advisers, and the gallantry of the besieged, were alike objects of much exaggeration. 'The siege was from first to last thoroughly ill-conducted, and the defence, in reality not better managed, owed its éclat to Persian ignorance, timidity and supineness. The advice of Pottinger, the gallant English officer who assisted the defence, was

--3--

seldom asked, and still more seldom taken; and no one spoke more plainly of the conduct of both besieged and besiegers than did Pottinger himself.' M'Neill effected nothing definite during a long stay in the Persian camp before Herat, the counteracting influence of the Russian envoy being too strong with the Shah; and the British representative, weary of continual slights, at length quitted the Persian camp completely foiled. After six days' bombardment, the Persians and their Russian auxiliaries delivered an assault in force on June 23d, 1838. It failed, with heavy loss, and the dispirited Shah determined on raising the siege. His resolution was quickened by the arrival of Colonel Stoddart in his camp, with the information that a military force from Bombay, supported by ships of war, had landed on the island of Karrack in the Persian Gulf, and with the peremptory ultimatum to the Shah that he must retire from Herat at once. Lord Palmerston, in ordering this diversion in the Gulf, had thought himself justified by circumstances in overriding the clear and precise terms of an article in a treaty to which England had on several occasions engaged to adhere. As for the Shah, he appears to have been relieved by the ultimatum. On the 9th September he mounted his horse and rode away from Herat. The siege had lasted nine and a half months. To-day, half a century after Simonich the Russian envoy followed Mahomed Shah from battered but unconquered Herat, that city is still an Afghan place of arms.

Shah Soojah-ool Moolk, a grandson of the illustrious Ahmed Shah, reigned in Afghanistan from 1803 till 1809. His youth had been full of trouble and vicissitude. He

--4--

had been a wanderer, on the verge of starvation, a pedlar and a bandit, who raised money by plundering caravans. His courage was lightly reputed, and it was as a mere creature of circumstance that he reached the throne. His reign was perturbed, and in 1809 he was a fugitive and an exile. Runjeet Singh, the Sikh ruler of the Punjaub, defrauded him of the famous Koh-i-noor, which is now the most precious of the crown jewels of England, and plundered and imprisoned the fallen man. Shah Soojah at length escaped from Lahore. After further misfortunes he at length reached the British frontier station of Loodianah, and in 1816 became a pensioner of the East India Company.

After the downfall of Shah Soojah, Afghanistan for many years was a prey to anarchy. At length in 1826, Dost Mahomed succeeded in making himself supreme at Cabul, and this masterful man thenceforward held sway until his death in 1863, uninterruptedly save during the three years of the British occupation. Dost Mahomed was neither kith nor kin to the legitimate dynasty which he displaced. His father Poyndah Khan was an able statesman and gallant soldier. He left twenty-one sons, of whom Futteh Khan was the eldest, and Dost Mahomed one of the youngest. Futteh Khan was the Warwick of Afghanistan, but the Afghan 'Kingmaker' had no Barnet as the closing scene of his chequered life. Falling into hostile hands, he was blinded and scalped. Refusing to betray his brothers, he was leisurely cut to pieces by the order and in the presence of the monarch whom he had made. His young brother Dost Mahomed undertook to avenge his death. After years of varied fortunes the

--5--

Dost had worsted all his enemies, and in 1826 he became the ruler of Cabul. Throughout his long reign Dost Mahomed was a strong and wise ruler. His youth had been neglected and dissolute. His education was defective, and he had been addicted to wine. Once seated on the throne, the reformation of our Henry Fifth was not more thorough than was that of Dost Mahomed. He taught himself to read and write, studied the Koran, became scrupulously abstemious, assiduous in affairs, no longer truculent but courteous. He is said to have made a public acknowledgment of the errors of his previous life, and a firm profession of reformation; nor did his after life belie the pledges to which he committed himself. There was a fine rugged honesty in his nature, and a streak of genuine chivalry; notwithstanding the despite he suffered at our hands, he had a real regard for the English, and his loyalty to us was broken only by his armed support of the Sikhs in the second Punjaub war.

The fallen Shah Soojah, from his asylum in Loodianah, was continually intriguing for his restoration. His schemes were long inoperative, and it was not until 1832 that certain arrangements were entered into between him and the Maharaja Runjeet Singh. To an application on Shah Soojah's part for countenance and pecuniary aid, the Anglo-Indian Government replied that to afford him assistance would be inconsistent with the policy of neutrality which the Government had imposed on itself; but it unwisely contributed financially toward his undertaking by granting him four months' pension in advance. Sixteen thousand rupees formed a scant war fund with which to attempt the recovery of a throne, but the Shah

--6--

started on his errand in February 1833. After a successful contest with the Ameers of Scinde, he marched on Candahar, and besieged that fortress. Candahar was in extremity when Dost Mahomed, hurrying from Cabul, relieved it, and joining forces with its defenders, he defeated and routed Shah Soojah, who fled precipitately, leaving behind him his artillery and camp equipage. During the Dost's absence in the south, Runjeet Singh's troops crossed the Attock, occupied the Afghan province of Peshawur, and drove the Afghans into the Khyber Pass. No subsequent efforts on Dost Mahomed's part availed to expel the Sikhs from Peshawur, and suspicious of British connivance with Runjeet Singh's successful aggression, he took into consideration the policy of fortifying himself by a counter alliance with Persia. As for Shah Soojah, he had crept back to his refuge at Loodianah.

Lord Auckland succeeded Lord William Bentinck as Governor-General of India in March 1836. In reply to Dost Mahomed's letter of congratulation, his lordship wrote: 'You are aware that it is not the practice of the British Government to interfere with the affairs of other independent states;' an abstention which Lord Auckland was soon to violate. He had brought from England the feeling of disquietude in regard to the designs of Persia and Russia which the communications of our envoy in Persia had fostered in the Home Government, but it would appear that he was wholly undecided what line of action to pursue. 'Swayed,' says Durand, 'by the vague apprehensions of a remote danger entertained by others rather than himself,' he despatched to Afghanistan Captain

--7--

Burnes on a nominally commercial mission, which, in fact, was one of political discovery, but without definite instructions. Burnes, an able but rash and ambitious man, reached Cabul in September 1837, two months before the Persian army began the siege of Herat. He had a strong prepossession in favour of the Dost, whose guest he had already been in 1832, and the policy he favoured was not the revival of the legitimate dynasty in the person of Shah Soojah, but the attachment of Dost Mahomed to British interests by strengthening his throne and affording him British countenance.

Burnes sanguinely believed that he had arrived at Cabul in the nick of time, for an envoy from the Shah of Persia was already at Candahar, bearing presents and assurances of support. The Dost made no concealment to Burnes of his approaches to Persia and Russia. In despair of British good offices, and being hungry for assistance from any source to meet the encroachments of the Sikhs, he professed himself ready to abandon his negotiations with the western powers if he were given reason to expect countenance and assistance at the hands of the Anglo-Indian Government. Burnes communicated to his Government those friendly proposals, supporting them by his own strong representations, and meanwhile, carried away by enthusiasm, he exceeded his powers by making efforts to dissuade the Candahar chiefs from the Persian alliance, and by offering to support them with money to enable them to make head against the offensive, by which Persia would probably seek to revenge the rejection of her overtures. For this unauthorised excess of zeal Burnes was severely reprimanded by his Government,

--8--

and was directed to retract his offers to the Candahar chiefs. The situation of Burnes in relation to the Dost was presently complicated by the arrival at Cabul of a Russian officer claiming to be an envoy from the Czar, whose credentials, however, were regarded as dubious, and who, if that circumstance has the least weight, was on his return to Russia utterly repudiated by Count Nesselrode. The Dost took small account of this emissary, continuing to assure Burnes that he cared for no connection except with the English, and Burnes professed to his Government his fullest confidences in the sincerity of those declarations. But the tone of Lord Auckland's reply, addressed to the Dost, was so dictatorial and supercilious as to indicate the writer's intention that it should give offence. It had that effect, and Burnes' mission at once became hopeless. Yet, as a last resort, Dost Mahomed lowered his pride so far as to write to the Governor-General imploring him 'to remedy the grievances of the Afghans, and afford them some little encouragement and power.' The pathetic representation had no effect. The Russian envoy, who was profuse in his promises of everything which the Dost was most anxious to obtain, was received into favour and treated with distinction, and on his return journey he effected a treaty with the Candahar chiefs, which was presently ratified by the Russian minister at the Persian Court. Burnes, fallen into discredit at Cabul, quitted that place in August 1838. He had not been discreet, but it was not his indiscretion that brought about the failure of his mission. A nefarious transaction, which Kaye denounces with the passion of a just indignation, connects itself with Burnes' negotiations with the Dost;

--9--

his official correspondence was unscrupulously mutilated and garbled in the published Blue Book with deliberate purpose to deceive the British public.

Burnes had failed because, since he had quitted India for Cabul, Lord Auckland's policy had gradually altered. Lord Auckland had landed in India in the character of a man of peace. That, so late as April 1837, he had no design of obstructing the existing situation in Afghanistan is proved by his written statement of that date, that 'the British Government had resolved decidedly to discourage the prosecution by the ex-king Shah Soojah-ool-Moolk, so long as he may remain under our protection, of further schemes of hostility against the chiefs now in power in Cabul and Candahar.' Yet, in the following June, he concluded a treaty which sent Shah Soojah to Cabul, escorted by British bayonets. Of this inconsistency no explanation presents itself. It was a far cry from our frontier on the Sutlej to Herat in the confines of Central Asia--a distance of more than 1200 miles, over some of the most arduous marching ground in the known world. No doubt the Anglo-Indian Government was justified in being somewhat concerned by the facts that a Persian army, backed by Russian volunteers and Russian roubles, was besieging Herat, and that Persian and Russian emissaries were at work in Afghanistan. Both phenomena were rather of the 'bogey' character; how much so to-day shows when the Afghan frontier is still beyond Herat, and when a descendant of Dost Mahomed still sits in the Cabul musnid. But neither England nor India scrupled to make the Karrack counter-threat which arrested the siege of Herat; and the obvious

--10--

policy as regarded Afghanistan was to watch the results of the intrigues which were on foot, to ignore them should they come to nothing, as was probable, to counteract them by familiar methods if serious consequences should seem impending. Our alliance with Runjeet Singh was solid, and the quarrel between Dost Mahomed and him concerning the Peshawur province was notoriously easy of arrangement.

On whose memory rests the dark shadow of responsibility for the first Afghan war? The late Lord Broughton, who, when Sir John Cam Hobhouse, was President of the Board of Control from 1835 to 1841, declared before a House of Commons Committee, in 1851, 'The Afghan war was done by myself; entirely without the privity of the Board of Directors.' The meaning of that declaration, of course, was that it was the British Government of the day which was responsible, acting through its member charged with the control of Indian affairs; and further, that the directorate of the East India Company was accorded no voice in the matter. But this utterance was materially qualified by Sir J. C. Hobhouse's statement in the House of Commons in 1842, that his despatch indicating the policy to be adopted, and that written by Lord Auckland, informing him that the expedition had already been undertaken, had crossed each other on the way.

It would be tedious to detail how Lord Auckland, under evil counsel, gradually boxed the compass from peace to war. The scheme of action embodied in the treaty which, in the early summer of 1838, was concluded between the Anglo-Indian Government, Runjeet Singh,

--11--

and Shah Soojah, was that Shah Soojah, with a force officered from an Indian army, and paid by British money, possessing also the goodwill and support of the Maharaja of the Punjaub, should attempt the recovery of his throne without any stiffening of British bayonets at his back. Then it was urged, and the representation was indeed accepted, that the Shah would need the buttress afforded by English troops, and that a couple of regiments only would suffice to afford this prestige. But Sir Harry Fane, the Commander-in-Chief, judiciously interposed his veto on the despatch of a handful of British soldiers on so distant and hazardous an expedition. Finally, the Governor-General, committed already to a mistaken line of policy, and urged forward by those about him, took the unfortunate resolution to gather together an Anglo-Indian army, and to send it, with the ill-omened Shah Soojah on its shoulders, into the unknown and distant wilds of Afghanistan. This action determined on, it was in accordance with the Anglo-Indian fitness of things that the Governor-General should promulgate a justificatory manifesto. Of this composition it is unnecessary to say more than to quote Durand's observation that in it 'the words "justice and necessity" were applied in a manner for which there is fortunately no precedent in the English language,' and Sir Henry Edwardes' not less trenchant comment that 'the views and conduct of Dost Mahomed were misrepresented with a hardihood which a Russian statesman might have envied.'

All men whose experience gave weight to their words opposed this 'preposterous enterprise.' Mr Elphinstone, who had been the head of a mission to Cabul thirty years

--12--

earlier, held that 'if an army was sent up the passes, and if we could feed it, no doubt we might take Cabul and set up Shah Soojah; but it was hopeless to maintain him in a poor, cold, strong and remote country, among so turbulent a people.' Lord William Bentinck, Lord Auckland's predecessor, denounced the project as an act of incredible folly. Marquis Wellesley regarded 'this wild expedition into a distant region of rocks and deserts, of sands and ice and snow,' as an act of infatuation. The Duke of Wellington pronounced with prophetic sagacity, that the consequence of once crossing the Indus to settle a government in Afghanistan would be a perennial march into that country.

--13--

CHAPTER II

THE MARCH TO CABUL

The two main objects of the venturesome offensive movement to which Lord Auckland had committed himself were, first, the raising of the Persian siege of Herat if the place should hold out until reached--the recapture of it if it should have fallen; and, secondly, the establishment of Shah Soojah on the Afghan throne. The former object was the more pressing, and time was very precious; but the distances in India are great, the means of communication in 1838 did not admit of celerity, and the seasons control the safe prosecution of military operations. Nevertheless, the concentration of the army at the frontier station of Ferozepore was fully accomplished toward the end of November. Sir Harry Fane was to be the military head of the expedition, and he had just right to be proud of the 14,000 carefully selected and well-seasoned troops who constituted his Bengal contingent. The force consisted of two infantry divisions, of which the first, commanded by Major-General Sir Willoughby Cotton, contained three brigades, commanded respectively by Colonels Sale, Nott, and Dennis, of whom the two former were to attain high

--14--

distinction within the borders of Afghanistan. Major-General Duncan commanded the second infantry division of the two brigades, of which one was commanded by Colonel Roberts, the gallant father of a gallant son, the other by Colonel Worsley. The 6000 troops raised for Shah Soojah, who were under Fane's orders, and were officered from our army in India, had been recently and hurriedly recruited, and although rapidly improving, were not yet in a state of high efficiency. The contingent which the Bombay Presidency was to furnish to the 'Army of the Indus,' and which landed about the close of the year near the mouth of the Indus, was under the command of General Sir John Keane, the Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay army. The Bombay force was about 5000 strong.

Before the concentration at Ferozepore had been completed, Lord Auckland received official intimation of the retreat of the Persians from before Herat. With their departure had gone, also, the sole legitimate object of the expedition; there remained but a project of wanton aggression and usurpation. The Russo-Persian failure at Herat was scarcely calculated to maintain in the astute and practical Afghans any hope of fulfilment of the promises which the western powers had thrown about so lavishly, while it made clear that, for some time at least to come, the Persians would not be found dancing again to Russian fiddling. The abandonment of the siege of Herat rendered the invasion of Afghanistan an aggression destitute even of pretext. The Governor-General endeavoured to justify his resolution to persevere in it by putting forth the argument that its prosecution was

--15--

required, 'alike in observation of the treaties entered into with Runjeet Singh and Shah Soojah as by paramount considerations of defensive policy.' A remarkable illustration of 'defensive policy' to take the offensive against a remote country from whose further confines had faded away foiled aggression, leaving behind nothing but a bitter consciousness of broken promises! As for the other plea, the tripartite treaty contained no covenant that we should send a corporal's guard across our frontier. If Shah Soojah had a powerful following in Afghanistan, he could regain his throne without our assistance; if he had no holding there, it was for us a truly discreditable enterprise to foist him on a recalcitrant people at the point of the bayonet.

One result of the tidings from Herat was to reduce by a division the strength of the expeditionary force. Fane, who had never taken kindly to the project, declined to associate himself with the diminished array that remained. The command of the Bengal column fell to Sir Willoughby Cotton, with whom as his aide-de-camp rode that Henry Havelock whose name twenty years later was to ring through India and England. Duncan's division was to stand fast at Ferozepore as a support, by which disposition the strength of the Bengal marching force was cut down to about 9500 fighting men. After its junction with the Bombay column, the army would be 14,500 strong, without reckoning the Shah's contingent. There was an interlude at Ferozepore of reviews and high jinks with the shrewd, debauched old Runjeet Singh; of which proceedings Havelock in his narrative of the expedition gives a detailed account, dwelling with extreme disapprobation

--16--

on Runjeet's addiction to a 'pet tipple' strong enough to lay out the hardest drinker in the British camp, but which the old reprobate quaffed freely without turning a hair.

At length, on December 10th, 1838, Cotton began the long march which was not to terminate at Cabul until August 6th of the following year. The most direct route was across the Punjaub, and up the passes from Peshawur, but the Governor-General had shrunk from proposing to Runjeet Singh that the force should march through his territories, thinking it enough that the Maharaja had permitted Shah Soojah's heir, Prince Timour, to go by Peshawur to Cabul, had engaged to support him with a Sikh force, and had agreed to maintain an army of reserve at Peshawur. The chosen route was by the left bank of the Sutlej to its junction with the Indus, down the left bank of the Indus to the crossing point at Roree, and from Sukkur across the Scinde and northern Belooch provinces by the Bolan and Kojuk passes to Candahar, thence by Khelat-i-Ghilzai and Ghuznee to Cabul. This was a line excessively circuitous, immensely long, full of difficulties, and equally disadvantageous as to supplies and communications. On the way the column would have to effect a junction with the Bombay force, which at Vikkur was distant 800 miles from Ferozepore. Of the distance of 850 miles from the latter post to Candahar the first half to the crossing of the Indus presented no serious difficulties, but from Sukkur beyond the country was inhospitable and cruelly rugged. It needed little military knowledge to realise how more and yet more precarious would become the communications as the chain lengthened,

--17--

to discern that from Ferozepore to the Indus they would be at the mercy of the Sikhs, and to comprehend this also, that a single serious check, in or beyond the passes, would involve all but inevitable ruin.

Shah Soojah and his levies moved independently some marches in advance of Cotton. The Dooranee monarch-elect had already crossed the Indus, and was encamped at Shikarpore, when he was joined by Mr William Hay Macnaghten, of the Company's Civil Service, the high functionary who had been gazetted as 'Envoy and Minister on the part of the Government of India at the Court of Shah Soojah-ool-Moolk.' Durand pronounces the selection an unhappy one, 'for Macnaghten, long accustomed to irresponsible office, inexperienced in men, and ignorant of the country and people of Afghanistan, was, though an erudite Arabic scholar, neither practised in the field of Asiatic intrigue nor a man of action. His ambition was, however, great, and the expedition, holding out the promise of distinction and honours, had met with his strenuous advocacy.' Macnaghten was one of the three men who chiefly inspired Lord Auckland with the policy to which he had committed himself. He was the negotiator of the tripartite treaty. He was now on his way toward a region wherein he was to concern himself in strange adventures, the outcome of which was to darken his reputation, consign him to a sudden cruel death, bring awful ruin on the enterprise he had fostered, and inflict incalculable damage on British prestige in India.

Marching through Bhawulpore and Northern Scinde, without noteworthy incident save heavy losses of draught

--18--

cattle, Cotton's army reached Roree, the point at which the Indus was to be crossed, in the third week of January 1839. Here a delay was encountered. The Scinde Ameers were, with reason, angered by the unjust and exacting terms which Pottinger had been instructed to enforce on them. They had been virtually independent of Afghanistan for nearly half a century; there was now masterfully demanded of them quarter of a million sterling in name of back tribute, and this in the face of the fact that they held a solemn release by Shah Soojah of all past and future claims. When they demurred to this, and to other exactions, they were peremptorily told that 'neither the ready power to crush and annihilate them, nor the will to call it into action, was wanting if it appeared requisite, however remotely, for the safety and integrity of the Anglo-Indian empire and frontier.'

It was little wonder that the Ameers were reluctant to fall in with terms advanced so arrogantly. Keane marched up the right bank of the Indus to within a couple of marches of Hyderabad, and having heard of the rejection by the Ameers of Pottinger's terms, and of the gathering of some 20,000 armed Belooches about the capital, he called for the co-operation of part of the Bengal column in a movement on Hyderabad. Cotton started on his march down the left bank, on January 30th, with 5600 men. Under menaces so ominous the unfortunate Ameers succumbed. Cotton returned to Roree; the Bengal column crossed the Indus, and on February 20th its headquarters reached Shikarpore. Ten days later, Cotton, leading the advance, was in Dadur, at the foot of the Bolan Pass, having suffered heavily in transport

--19--

animals almost from the start. Supplies were scarce in a region so barren, but with a month's partial food on his beasts of burden he quitted Dadur March 10th, got safely, if toilsomely, through the Bolan, and on 26th reached Quetta, where he was to halt for orders. Shah Soojah and Keane followed, their troops suffering not a little from scarcity of supplies and loss of animals.

Keane's error in detaining Cotton at Quetta until he should arrive proved itself in the semi-starvation to which the troops of the Bengal column were reduced. The Khan of Khelat, whether from disaffection or inability, left unfulfilled his promise to supply grain, and the result of the quarrel which Burnes picked with him was that he shunned coming in and paying homage to Shah Soojah, for which default he was to suffer cruel and unjustifiable ruin. The sepoys were put on half, the camp followers on quarter rations, and the force for eleven days had been idly consuming the waning supplies, when at length, on April 6th, Keane came into camp, having already formally assumed the command of the whole army, and made certain alterations in its organisation and subsidiary commands. There still remained to be traversed 147 miles before Candahar should be reached, and the dreaded Kojuk Pass had still to be penetrated.

Keane was a soldier who had gained a reputation for courage in Egypt and the Peninsula. He was indebted to the acuteness of his engineer and the valour of his troops, for the peerage conferred on him for Ghuznee, and it cannot be said that during his command in Afghanistan he disclosed any marked military aptitude. But he had sufficient perception to recognise that he had brought the

--20--

Bengal column to the verge of starvation in Quetta, and sufficient common sense to discern that, since if it remained there it would soon starve outright, the best thing to be done was to push it forward with all possible speed into a region where food should be procurable. Acting on this reasoning, he marched the day after his arrival. Cotton, while lying in Quetta, had not taken the trouble to reconnoitre the passes in advance, far less to make a practicable road through the Kojuk defile if that should prove the best route. The resolution taken to march through it, two days were spent in making the pass possible for wheels; and from the 13th to the 21st the column was engaged in overcoming the obstacles it presented, losing in the task, besides, much baggage, supplies, transport and ordnance stores. Further back in the Bolan Willshire with the Bombay column was faring worse; he was plundered severely by tribal marauders.

By May 4th the main body of the army was encamped in the plain of Candahar. From the Kojuk, Shah Soojah and his contingent had led the advance toward the southern capital of the dominions from the throne of which he had been cast down thirty years before. The Candahar chiefs had meditated a night attack on his raw troops, but Macnaghten's intrigues and bribes had wrought defection in their camp; and while Kohun-dil-Khan and his brothers were in flight to Girishk on the Helmund, the infamous Hadji Khan Kakur led the venal herd of turncoat sycophants to the feet of the claimant who came backed by the British gold, which Macnaghten was scattering abroad with lavish hand. Shah Soojah recovered from his trepidation, hurried forward in advance

--21--

of his troops, and entered Candahar on April 24th. His reception was cold. The influential chiefs stood aloof, abiding the signs of the times; the populace of Candahar stood silent and lowering. Nor did the sullenness abate when the presence of a large army with its followers promptly raised the price of grain, to the great distress of the poor. The ceremony of the solemn recognition of the Shah, held close to the scene of his defeat in 1834, Havelock describes as an imposing pageant, with homagings and royal salutes, parade of troops and presentation of nuzzurs; but the arena set apart for the inhabitants was empty, spite of Eastern love for a tamasha, and the display of enthusiasm was confined to the immediate retainers of His Majesty.

The Shah was eager for the pursuit of the fugitive chiefs; but the troops were jaded and sickly, the cavalry were partially dismounted, and what horses remained were feeble skeletons. The transport animals needed grazing and rest, and their loss of numbers to be made good. The crops were not yet ripe, and provisions were scant and dear. When, on May 9th, Sale marched toward Girishk, his detachment carried half rations, and his handful of regular cavalry was all that two regiments could furnish. Reaching Girishk, he found that the chiefs had fled toward Seistan, and leaving a regiment of the Shah's contingent in occupation, he returned to Candahar.

Macnaghten professed the belief, and perhaps may have deluded himself into it, that Candahar had received the Shah with enthusiasm. He was sanguine that the march to Cabul would be unopposed, and he urged on Keane, who was wholly dependent on the Envoy for

--22--

political information, to move forward at once, lightening the difficulties of the march by leaving the Bombay troops at Candahar. But Keane declined, on the advice of Thomson, his chief engineer, who asked significantly whether he had found the information given him by the political department in any single instance correct. Food prospects, however, did not improve at Candahar, and leaving a strong garrison there as well, curious to say, as the siege train which with arduous labour had been brought up the passes, Keane began the march to Cabul on June 27th. He had supplies only sufficient to carry his army thither on half rations. Macnaghten had lavished money so freely that the treasury chest was all but empty. How the Afghans regarded the invasion was evinced by condign slaughter of our stragglers.

As the army advanced up the valley of the Turnuk, the climate became more temperate, the harvest was later, and the troops improved in health and spirit. Concentrating his forces, Keane reached Ghuznee on July 21st. The reconnaissance he made proved that fortress occupied in force. The outposts driven in, and a close inspection made, the works were found stronger than had been represented, and its regular reduction was out of the question without the battering train which Keane had allowed himself to be persuaded into leaving behind. A wall some 70 feet high and a wet ditch in its front made mining and escalade alike impracticable. Thomson, however, noticed that the road and bridge to the Cabul gate were intact. He obtained trustworthy information that up to a recent date, while all the other gates had been built up, the Cabul gate had not been so

--23--

dealt with. As he watched, a horseman was seen to enter by it. This was conclusive. The ground within 400 yards of the gate offered good artillery positions. Thomson therefore reported that although the operation was full of risk, and success if attained must cost dear, yet in the absence of a less hazardous method of reduction there offered a fair chance of success in an attempt to blow open the Cabul gate, and then carry the place by a coup de main. Keane was precluded from the alternative of masking the place and continuing his advance by the all but total exhaustion of his supplies, which the capture of Ghuznee would replenish, and he therefore resolved on an assault by the Cabul gate.

During the 21st July the army circled round the place, and camped to the north of it on the Cabul road. The following day was spent in preparations, and in defeating an attack made on the Shah's contingent by several thousand Ghilzai tribesmen of the adjacent hill country. In the gusty darkness of the early morning of the 23d the field artillery was placed in battery on the heights opposite the northern face of the fortress. The 13th regiment was extended in skirmishing order in the gardens under the wall of this face, and a detachment of sepoys was detailed to make a false attack on the eastern face. Near the centre of the northern face was the Cabul gate, in front of which lay waiting for the signal, a storming party consisting of the light companies of the four European regiments, under command of Colonel Dennie of the 13th. The main column consisted of two European regiments and the support of a third, the whole commanded by Brigadier Sale; the native regiments constituted the

--24--

reserve. All those dispositions were completed by three A.M., and, favoured by the noise of the wind and the darkness, without alarming the garrison.

Punctually at this hour the little party of engineers charged with the task of blowing in the gate started forward on the hazardous errand. Captain Peat of the Bombay Engineers was in command. Durand, a young lieutenant of Bengal Engineers, who was later to attain high distinction, was entrusted with the service of heading the explosion party. The latter, leading the party, had advanced unmolested to within 150 yards of the works, when a challenge, a shot and a shout gave intimation of his detection. A musketry fire was promptly opened by the garrison from the battlements, and blue lights illuminated the approach to the gate, but in the fortunate absence of fire from the lower works the bridge was safely crossed, and Peat with his handful of linesmen halted in a sallyport to cover the explosion operation. Durand advanced to the gate, his sappers piled their powder bags against it and withdrew; Durand and his sergeant uncoiled the hose, ignited the quick-match under a rain from the battlements of bullets and miscellaneous missiles, and then retired to cover out of reach of the explosion.

At the sound of the first shot from the battlements, Keane's cannon had opened their fire. The skirmishers in the gardens engaged in a brisk fusillade. The rattle of Hay's musketry was heard from the east. The garrison was alert in its reply. The northern ramparts became a sheet of flame, and everywhere the cannonade and musketry fire waxed in noise and volume. Suddenly, as the day was beginning to dawn, a dull, heavy sound was heard by

--25--

the head of the waiting column, scarce audible elsewhere because of the boisterous wind and the din of the firing. A pillar of black smoke shot up from where had been the Afghan gate, now shattered by the 300 pounds of gunpowder which Durand had exploded against it. The signal to the storming party was to be the 'advance' sounded by the bugler who accompanied Peat. But the bugler had been shot through the head. Durand could not find Peat. Going back through the bullets to the nearest party of infantry, he experienced some delay, but at last the column was apprised that all was right, the 'advance' was sounded, Dennie and his stormers sped forward, and Sale followed at the head of the main column.

After a temporary check to the latter, because of a misconception, it pushed on in close support of Dennie. That gallant soldier and his gallant followers had rushed into the smoking and gloomy archway to find themselves met hand to hand by the Afghan defenders, who had recovered from their surprise. Nothing could be distinctly seen in the narrow gorge, but the clash of sword blade against bayonet was heard on every side. The stormers had to grope their way between the yet standing walls in a dusk which the glimmer of the blue light only made more perplexing. But some elbow room was gradually gained, and then, since there was neither time nor space for methodic street fighting, each loaded section gave its volley and then made way for the next, which, crowding to the front, poured a deadly discharge at half pistol-shot into the densely crowded defenders. Thus the storming party won steadily its way, till at length Dennie and his

--26--

leading files discerned over the heads of their opponents a patch of blue sky and a twinkling star or two, and with a final charge found themselves within the place.

A body of fierce Afghan swordsmen projected themselves into the interval between the storming party and the main column. Sale, at the head of the latter, was cut down by a tulwar stroke in the face; in the effort of his blow the assailant fell with the assailed, and they rolled together among the shattered timbers of the gate. Sale, wounded again on the ground, and faint with loss of blood, called to one of his officers for assistance. Kershaw ran the Afghan through the body with his sword; but he still struggled with the Brigadier. At length in the grapple Sale got uppermost, and then he dealt his adversary a sabre cut which cleft him from crown to eyebrows. There was much confused fighting within the place, for the Afghan garrison made furious rallies again and again; but the citadel was found open and undefended, and by sunrise British banners were waving above its battlements Hyder Khan, the Governor of Ghuznee, one of the sons of Dost Mahomed, was found concealed in a house in the town and taken prisoner. The British loss amounted to about 200 killed and wounded, that of the garrison, which was estimated at from 3000 to 4000 strong, was over 500 killed. The number of wounded was not ascertained; of prisoners taken in arms there were about 1600. The booty consisted of numerous horses, camels and mules, ordnance and military weapons of various descriptions, and a vast quantity of supplies of all kinds.

Keane, having garrisoned Ghuznee, and left there his sick and wounded, resumed on July 30th his march on

--27--

Cabul. Within twenty-four hours after the event Dost Mahomed heard of the fall of Ghuznee. Possessed of the adverse intelligence, the Dost gathered his chiefs, received their facile assurances of fidelity, sent his brother the Nawaub Jubbar Khan to ask what terms Shah Soojah and his British allies were prepared to offer him, and recalled from Jellalabad his son Akbar Khan, with all the force he could muster there. The Dost's emissary to the allied camp was informed that 'an honourable asylum' in British India was at the service of his brother; an offer which Jubbar Khan declined in his name without thanks. Before he left to share the fortunes of the Dost, the Sirdar is reported to have asked Macnaghten, 'If Shah Soojah is really our king, what need has he of your army and name? You have brought him here,' he continued, 'with your money and arms. Well, leave him now with us Afghans, and let him rule us if he can.' When Jubbar Khan returned to Cabul with his sombre message, the Dost, having been joined by Akbar Khan, concentrated his army, and found himself at the head of 13,000 men, with thirty guns; but he mournfully realised that he could lean no reliance on the constancy and courage of his adherents. Nevertheless, he marched out along the Ghuznee road, and drew up his force at Urgundeh, where he commanded the most direct line of retreat toward the western hill country of Bamian, in case his people would not fight, or should they fight, if they were beaten.

There was no fight in his following; scarcely, indeed, was there a loyal supporter among all those who had eaten his salt for years. There was true manhood in this chief whom we were replacing by an effete puppet. The

--28--

Dost, Koran in hand, rode among his perfidious troops, and conjured them in the name of God and the Prophet not to dishonour themselves by transferring their allegiance to one who had filled Afghanistan with infidels and blasphemers. 'If,' he continued, 'you are resolved to be traitors to me, at least enable me to die with honour. Support the brother of Futteh Khan in one last charge against these Feringhee dogs. In that charge he will fall; then go and make your own terms with Shah Soojah.' The high-souled appeal inspired no worthy response; but one is loth to credit the testimony of the soldier-of-fortune Harlan that his guards forsook the Dost, and that the rabble of troops plundered his pavilion, snatched from under him the pillows of his divan, seized his prayer carpet, and finally hacked into pieces the tent and its appurtenances. On the evening of August 2d the hapless man shook the dust of the camp of traitors from his feet, and rode away toward Bamian, his son Akbar Khan, with a handful of resolute men, covering the retreat of his father and his family. Tidings of the flight of Dost Mahomed reached Keane on the 3d, at Sheikabad, where he had halted to concentrate; and Outram volunteered to head a pursuing party, to consist of some British officers as volunteers, some cavalry and some Afghan horse. Hadji Khan Kakur, the earliest traitor of his race, undertook to act as guide. This man's devices of delay defeated Outram's fiery energy, perhaps in deceit, perhaps because he regarded it as lacking discretion. For Akbar Khan made a long halt on the crown of the pass, waiting to check any endeavour to press closely on his fugitive father, and it would have gone hard with

--29--

Outram, with a few fagged horsemen at his back, if Hadji Khan had allowed him to overtake the resolute young Afghan chief. As Keane moved forward, there fell to him the guns which the Dost had left in the Urgundeh position. On August 6th he encamped close to Cabul; and on the following day Shah Soojah made his public entry into the capital which he had last seen thirty years previously. After so many years of vicissitude, adventure and intrigue, he was again on the throne of his ancestors, but placed there by the bayonets of the Government whose creature he was, an insult to the nation whom he had the insolence to call his people.

The entry, nevertheless, was a goodly spectacle enough. Shah Soojah, dazzling in coronet, jewelled girdle and bracelets, but with no Koh-i-noor now glittering on his forehead, bestrode a white charger, whose equipments gleamed with gold. By his side rode Macnaghten and Burnes; in the pageant were the principal officers of the British army. Sabres flashed in front of the procession, bayonets sparkled in its rear, as it wended its way through the great bazaar which Pollock was to destroy three years later, and along the tortuous street to the gate of the Balla Hissar. But neither the monarch nor his pageant kindled the enthusiasm in the Cabulees. There was no voice of welcome; the citizens did not care to trouble themselves so much as to make him a salaam, and they stared at the European strangers harder than at his restored majesty. There was a touch of pathos in the burst of eagerness to which the old man gave way as he reached the palace, ran through the gardens, visited the apartments, and commented on the neglect

--30--

everywhere apparent. Shah Soojah was rather a poor creature, but he was by no means altogether destitute of good points, and far worse men than he were actors in the strange historical episode of which he was the figurehead. He was humane for an Afghan; he never was proved to have been untrue to us; he must have had some courage of a kind else he would never have remained in Cabul when our people left it, in the all but full assurance of the fate which presently overtook him as a matter of course. Havelock thus portrays him: 'A stout person of the middle height, his chin covered with a long thick and neatly trimmed beard, dyed black to conceal the encroachments of time. His manner toward the English is gentle, calm and dignified, without haughtiness, but his own subjects have invariably complained of his reception of them as cold and repulsive, even to rudeness. His complexion is darker than that of the generality of Afghans, and his features, if not decidedly handsome, are not the reverse of pleasing; but the expression of his countenance would betray to a skilful physiognomist that mixture of timidity and duplicity so often observable in the character of the higher order of men in Southern Asia.'

--31--

CHAPTER III

THE FIRST YEAR OF OCCUPATION

Sir John Kaye, in his picturesque if diffuse history of the first Afghan war, lays it down that, in seating Shah Soojah on the Cabul throne, 'the British Government had done all that it had undertaken to do,' and Durand argues that, having accomplished this, 'the British army could have then been withdrawn with the honour and fame of entire success.' The facts apparently do not justify the reasoning of either writer. In the Simla manifesto, in which Lord Auckland embodied the rationale of his policy, he expressed the confident hope 'that the Shah will be speedily replaced on his throne by his own subjects and adherents, and when once he shall be received in power, and the independence and integrity of Afghanistan established, the British army will be withdrawn.' The Shah had been indeed restored to his throne, but by British bayonets, not by 'his own subjects and adherents.' It could not seriously be maintained that he was secure in power, or that the independence and integrity of Afghanistan were established when British troops were holding Candahar, Ghuznee and Cabul, the only three positions where the Shah was nominally paramount, when the

--32--

fugitive Dost was still within its borders, when intrigue and disaffection were seething in every valley and on every hill-side, and when the principality of Herat maintained a contemptuous independence. Macnaghten might avow himself convinced of the popularity of the Shah, and believe or strive to believe that the Afghans had received the puppet king `with feelings nearly amounting to adoration,' but he did not venture to support the conviction he avowed by advocating that the Shah should be abandoned to his adoring subjects. Lord Auckland's policy was gravely and radically erroneous, but it had a definite object, and that object certainly was not a futile march to Cabul and back, dropping incidentally by the wayside the aspirant to a throne whom he had himself put forward, and leaving him to take his chance among a truculent and adverse population. Thus early, in all probability, Lord Auckland was disillusioned of the expectation that the effective restoration of Shah Soojah would be of light and easy accomplishment, but at least he could not afford to have the enterprise a coup manqué when as yet it was little beyond its inception.

The cost of the expedition was already, however, a strain, and the troops engaged in it were needed in India. Lord Auckland intimated to Macnaghten his expectation that a strong brigade would suffice to hold Afghanistan in conjunction with the Shah's contingent, and his desire that the rest of the army of the Indus should at once return to India. Macnaghten, on the other hand, in spite of his avowal of the Shah's popularity, was anxious to retain in Afghanistan a large body of troops. He meditated strange enterprises, and proposed that Keane should support his

--33--

project of sending a force toward Bokhara to give check to a Russian column which Pottinger at Herat had heard was assembling at Orenburg, with Khiva for its objective. Keane derided the proposal, and Macnaghten reluctantly abandoned it, but he demanded of Lord Auckland with success, the retention in Afghanistan of the Bengal division of the army. In the middle of September General Willshire marched with the Bombay column, with orders, on his way to the Indus to pay a hostile visit to Khelat, and punish its khan for the 'disloyalty' with which he had been charged, a commission which the British officer fulfilled with a skill and thoroughness that could be admired with less reservation had the aggression on the gallant Mehrab been less wanton. A month later Keane started for India by the Khyber route, which Wade had opened without serious resistance when in August and September he escorted through the passes Prince Timour, Shah Soojah's heir-apparent. During the temporary absence of Cotton, who accompanied Keane, Nott had the command at Candahar, Sale at and about Cabul, and the troops were quartered in those capitals, and in Jellalabad, Ghuznee, Charikar and Bamian. The Shah and the Envoy wintered in the milder climate of Jellalabad, and Burnes was in political charge of the capital and its vicinity.

It was a prophetic utterance that the accomplishment of our military succession would mark but the commencement of our real difficulties in Afghanistan. In theory and in name Shah Soojah was an independent monarch; it was, indeed, only in virtue of his proving himself able to rule independently that he could justify his claim to

--34--

rule at all. But that he was independent was a contradiction in terms while British troops studded the country, and while the real powers of sovereignty were exercised by Macnaghten. Certain functions, it is true, the latter did permit the nominal monarch to exercise. While debarred from a voice in measures of external policy, and not allowed to sway the lines of conduct to be adopted toward independent or revolting tribes, the Shah was allowed to concern himself with the administration of justice, and in his hands were the settlement, collection and appropriation of the revenue of those portions of the kingdom from which any revenue could be exacted. He was allowed to appoint as his minister of state, the companion of his exile, old Moolla Shikore, who had lost both his memory and his ears, but who had sufficient faculty left to hate the English, to oppress the people, to be corrupt and venal beyond all conception, and to appoint subordinates as flagitious as himself. 'Bad ministers,' wrote Burnes, 'are in every government solid ground for unpopularity; and I doubt if ever a king had a worse set than has Shah Soojah.' The oppressed people appealed to the British functionaries, who remonstrated with the minister, and the minister punished the people for appealing to the British functionaries. The Shah was free to confer grants of land on his creatures, but when the holders resisted, he was unable to enforce his will since he was not allowed to employ soldiers; and the odium of the forcible confiscation ultimately fell on Macnaghten, who alone had the ordering of expeditions, and who could not see the Shah belittled by non-fulfilment of his requisitions.

Justice sold by venal judges, oppression and corruption

--35--

rampant in every department of internal administration, it was no wonder that nobles and people alike resented the inflictions under whose sting they writhed. They were accustomed to a certain amount of oppression; Dost Mahomed had chastised them with whips, but Shah Soojah, whom the English had brought, was chastising them with scorpions. And they felt his yoke the more bitterly because, with the shrewd acuteness of the race, they recognised the really servile condition of this new king. They fretted, too, under the sharp bit of the British political agents who were strewn about the country, in the execution of a miserable and futile policy, and whose lives, in a few instances, did not maintain the good name of their country. Dost Mahomed had maintained his sway by politic management of the chiefs, and through them of the tribes. Macnaghten would have done well to impress on Shah Soojah the wisdom of pursuing the same tactics. There was, it is true, the alternative of destroying the power of the barons, but that policy involved a stubborn and doubtful struggle, and prolonged occupation of the country by British troops in great strength. Macnaghten professed our occupation of Afghanistan to be temporary; yet he was clearly adventuring on the rash experiment of weakening the nobles when he set about the enlistment of local tribal levies, who, paid from the Royal treasury and commanded by British officers, were expected to be staunch to the Shah, and useful in curbing the powers of the chiefs. The latter, of course, were alienated and resentful, and the levies, imbued with the Afghan attribute of fickleness, proved for the most part undisciplined and faithless.

--36--

The winter of 1839-40 passed without much noteworthy incident. The winter climate of Afghanistan is severe, and the Afghan, in ordinary circumstances, is among the hibernating animals. But down in the Khyber, in October, the tribes gave some trouble. They were dissatisfied with the amount of annual black-mail paid them for the right of way through their passes. When the Shah was a fugitive thirty years previously, they had concealed and protected him; and mindful of their kindly services, he had promised them, unknown to Macnaghten, the augmentation of their subsidy to the old scale from which it had gradually dwindled. Wade, returning from Cabul, did not bring them the assurances they expected, whereupon they rose and concentrated and invested Ali Musjid, a fort which they regarded as the key of their gloomy defile. Mackeson, the Peshawur political officer, threw provisions and ammunition into Ali Musjid, but the force, on its return march, was attacked by the hillmen, the Sikhs being routed, and the sepoys incurring loss of men and transport. The emboldened Khyberees now turned on Ali Musjid in earnest; but the garrison was strengthened, and the place was held until a couple of regiments marched down from Jellalabad, and were preparing to attack the hillmen, when it was announced that Mackeson had made a compact with the chiefs for the payment of an annual subsidy which they considered adequate.

Afghanistan fifty years ago, and the same is in a measure true of it to-day, was rather a bundle of provinces, some of which owned scarcely a nominal allegiance to the ruler in Cabul, than a concrete state. Herat and Candahar were wholly independent, the Ghilzai tribes inhabiting

--37--

the wide tracts from the Suliman ranges westward beyond the road through Ghuznee, between Candahar and Cabul, and northward into the rugged country between Cabul and Jellalabad, acknowledged no other authority than that of their own chiefs. The Ghilzais are agriculturists, shepherds, and robbers; they are constantly engaged in internal feuds; they are jealous of their wild independence, and through the centuries have abated little of their untamed ferocity. They had rejected Macnaghten's advances, and had attacked Shah Soojah's camp on the day before the fall of Ghuznee. Outram, in reprisal, had promptly raided part of their country. Later, the winter had restrained them from activity, but they broke out again in the spring. In May Captain Anderson, marching from Candahar with a mixed force about 1200 strong, was offered battle near Jazee, in the Turnuk, by some 2000 Ghilzai horse and foot. Andersen's guns told heavily among the Ghilzai horsemen, who, impatient of the fire, made a spirited dash on his left flank. Grape and musketry checked them; but they rallied, and twice charged home on the bayonets before they withdrew, leaving 200 of their number dead on the ground. Nott sent a detachment to occupy the fortress of Khelat-i-Ghilzai, between Candahar and Ghuznee, thus rendering the communications more secure; and later, Macnaghten bribed the chiefs by an annual subsidy of £600 to abstain from infesting the highways. The terms were cheap, for the Ghilzai tribes mustered some 40,000 fighting men.

Shah Soojah and the Envoy returned from Jellalabad to Cabul in April 1840. A couple of regiments had

--38--

wintered not uncomfortably in the Balla Hissar. That fortress was then the key of Cabul, and while our troops remained in Afghanistan it should not have been left ungarrisoned a single hour. The soldiers did their best to impress on Macnaghten the all-importance of the position. But the Shah objected to its continued occupation, and Macnaghten weakly yielded. Cotton, who had returned to the chief military command in Afghanistan, made no remonstrance; the Balla Hissar was evacuated, and the troops were quartered in cantonments built in an utterly defenceless position on the plain north of Cabul, a position whose environs were cumbered with walled gardens, and commanded by adjacent high ground, and by native forts which were neither demolished nor occupied. The troops, now in permanent and regularly constructed quarters, ceased to be an expeditionary force, and became substantially an army of occupation. The officers sent for their wives to inhabit with them the bungalows in which they had settled down. Lady Macnaghten, in the spacious mission residence which stood apart in its own grounds, presided over the society of the cantonments, which had all the cheery surroundings of the half-settled, half-nomadic life of our military people in the East. There were the 'coffee house' after the morning ride, the gathering round the bandstand in the evening, the impromptu dance, and the burra khana occasionally in the larger houses. A racecourse had been laid out, and there were 'sky' races and more formal meetings. And so 'as in the days that were before the flood, they were eating and drinking, and marrying and giving in marriage, and knew not until the flood came, and took them all away.'

--39--

Macnaghten engaged himself in a welter of internal and external intrigue, his mood swinging from singular complacency to a disquietude that sometimes approached despondency. It had come to be forced on him, in spite of his intermittent optimism, that the Government was a government of sentry-boxes, and that Afghanistan was not governed so much as garrisoned. The utter failure of the winter march attempted by Peroffski's Russian column across the frozen steppes on Khiva was a relief to him; but the state of affairs in Herat was a constant trouble and anxiety. Major Todd had been sent there as political agent, to make a treaty with Shah Kamran, and to superintend the repair and improvement of the fortifications of the city. Kamran was plenteously subsidised; he took Macnaghten's lakhs, but furtively maintained close relations with Persia. Detecting the double-dealing, Macnaghten urged on Lord Auckland the annexation of Herat to Shah Soojah's dominions, but was instructed to condone Kamran's duplicity, and try to bribe him higher. Kamran by no means objected to this policy, and, while continuing his intrigues with Persia, cheerfully accepted the money, arms and ammunition which Macnaghten supplied him with so profusely as to cause remonstrance on the part of the financial authorities in Calcutta. The Commander-in-Chief was strong enough to counteract the pressure which Macnaghten brought to bear on Lord Auckland in favour of an expedition against Herat, which his lordship at length finally negatived, to the great disgust of the Envoy, who wrote of the conduct of his chief as 'drivelling beyond contempt,' and 'sighed for a Wellesley or a Hastings.' The ultimate result of Macnaghten's

--40--

negotiations with Shah Kamran was Major Todd's withdrawal from Herat. Todd had suspended the monthly subsidy, to the great wrath of Kamran's rapacious and treacherous minister Yar Mahomed, who made a peremptory demand for increased advances, and refused Todd's stipulation that a British force should be admitted into Herat. Todd's action in quitting Herat was severely censured by his superiors, and he was relegated to regimental duty. Perhaps he acted somewhat rashly, but he had not been kept well informed; for instance, he had been unaware that Persia had become our friend, and had engaged to cease relations with Shah Kamran--an important arrangement of which he certainly should have been cognisant. Macnaghten had squandered more gold on Herat than the fee-simple of the principality was worth, and to no purpose; he left that state just as he found it, treacherous, insolent, greedy and independent.

The precariousness of the long lines of communications between British India and the army in Afghanistan--a source of danger which from the first had disquieted cautious soldiers--was making itself seriously felt, and constituted for Macnaghten another cause of solicitude. Old Runjeet Singh, a faithful if not disinterested ally, had died on June 27th, 1839, the day on which Keane marched out from Candahar. The breath was scarcely out of the old reprobate when the Punjaub began to drift into anarchy. So far as the Sikh share in it was concerned, the tripartite treaty threatened to become a dead letter. The Lahore Durbar had not adequately fulfilled the undertaking to support Prince Timour's advance by the Khyber, nor was it duly regarding the obligation to maintain

--41--

a force on the Peshawur frontier of the Punjaub. But those things were trivial in comparison with the growing reluctance manifested freely, to accord to our troops and convoys permission to traverse the Punjaub on the march to and from Cabul. The Anglo-Indian Government sent Mr Clerk to Lahore to settle the question as to the thoroughfare. He had instructions to be firm, and the Sikhs did not challenge Mr Clerk's stipulation that the Anglo-Indian Government must have unmolested right of way through the Punjaub, while he undertook to restrict the use of it as much as possible. This arrangement by no means satisfied the exacting Macnaghten, and he continued to worry himself by foreseeing all sorts of troublous contingencies unless measures were adopted for 'macadamising' the road through the Punjaub.

The summer of 1840 did not pass without serious interruptions to the British communications between Candahar and the Indus; nor without unexpected and ominous disasters before they were restored. General Willshire, with the returning Bombay column, had in the previous November stormed Mehrab Khan's ill-manned and worse armed fort of Khelat, and the Khan, disdaining to yield, had fallen in the hopeless struggle. His son Nusseer Khan had been put aside in favour of a collateral pretender, and became an active and dangerous malcontent. All Northern Beloochistan fell into a state of anarchy. A detachment of sepoys escorting supplies was cut to pieces in one of the passes. Quetta was attacked with great resolution by Nusseer Khan, but was opportunely relieved by a force sent from another post. Nusseer made himself master of Khelat, and there fell into his cruel hands

--42--

Lieutenant Loveday, the British political officer stationed there, whom he treated with great barbarity, and finally murdered. A British detachment under Colonel Clibborn, was defeated by the Beloochees with heavy loss, and compelled to retreat. Nusseer Khan, descending into the low country of Cutch, assaulted the important post of Dadur, but was repulsed, and taking refuge in the hills, was routed by Colonel Marshall with a force from Kotree, whereupon he became a skulking fugitive. Nott marched down from Candahar with a strong force, occupied Khelat, and fully re-established communications with the line of the Indus, while fresh troops moved forward into Upper Scinde, and thence gradually advancing to Quetta and Candahar, materially strengthened the British position in Southern Afghanistan.

Dost Mahomed, after his flight from Cabul in 1839, had soon left the hospitable refuge afforded him in Khooloom, a territory west of the Hindoo Koosh beyond Bamian, and had gone to Bokhara on the treacherous invitation of its Ameer, who threw him into captivity. The Dost's family remained at Khooloom, in the charge of his brother Jubbar Khan. The advance of British forces beyond Bamian to Syghan and Bajgah, induced that Sirdar to commit himself and the ladies to British protection. Dr Lord, Macnaghten's political officer in the Bamian district, was a rash although well-meaning man. The errors he had committed since the opening of spring had occasioned disasters to the troops whose dispositions he controlled, and had incited the neighbouring hill tribes to active disaffection. In July Dost Mahomed made his escape from Bokhara, hurried to Khooloom, found its ruler and the tribes full of

--43--

zeal for his cause, and rapidly grew in strength. Lord found it was time to call in his advance posts and concentrate at Bamian, losing in the operation an Afghan regiment which deserted to the Dost. Macnaghten reinforced Bamian, and sent Colonel Dennie to command there. On September 18th Dennie moved out with two guns and 800 men against the Dost's advance parties raiding in an adjacent valley. Those detachments driven back, Dennie suddenly found himself opposed to the irregular mass of Oosbeg horse and foot which constituted the army of the Dost. Mackenzie's cannon fire shook the undisciplined horde, the infantry pressed in to close quarters, and soon the nondescript host of the Dost was in panic flight, with Dennie's cavalry in eager pursuit. The Dost escaped with difficulty, with the loss of his entire personal equipment. He was once more a fugitive, and the Wali of Khooloom promptly submitted himself to the victors, and pledged himself to aid and harbour the broken chief no more. Macnaghten had been a prey to apprehension while the Dost's attitude was threatening; he was now in a glow of joy and hope.

But the Envoy's elation was short-lived. Dost Mahomed was yet to cause him much solicitude. Defeated in Bamian, he was ready for another attempt in the Kohistan country to the north of Cabul. Disaffection was rife everywhere throughout the kingdom, but it was perhaps most rife in the Kohistan, which was seething with intrigues in favour of Dost Mahomed, while the local chiefs were intensely exasperated by the exactions of the Shah's revenue collectors. Macnaghten summoned the chiefs to Cabul. They came, they did homage to the Shah and

--44--

swore allegiance to him; they went away from the capital pledging each other to his overthrow, and jeering at the scantiness of the force they had seen at Cabul. Intercepted letters disclosed their schemes, and in the end of September Sale, with a considerable force, marched out to chastise the disaffected Kohistanees. The fort of Tootundurrah fell without resistance. Julgah, however, the next fort assailed, stubbornly held out, and officers and men fell in the unsuccessful attempt to storm it. In three weeks Sale marched to and fro through the Kohistan, pursuing will-o'-the-wisp rumours as to the whereabouts of the Dost, destroying forts on the course of his weary pilgrimage, and subjected occasionally to night attacks.

Meanwhile, in the belief that Dost Mahomed was close to Cabul, and mournfully conscious that the capital and surrounding country were ripe for a rising, Macnaghten had relapsed into nervousness, and was a prey to gloomy forebodings. The troops at Bamian were urgently recalled. Cannon were mounted on the Balla Hissar to overawe the city, the concentration of the troops in the fortress was under consideration, and men were talking of preparing for a siege. How Macnaghten's English nature was undergoing deterioration under the strain of events is shown by his writing of the Dost: 'Would it be justifiable to set a price on this fellow's head?' How his perceptions were warped was further evinced by his talking of 'showing no mercy to the man who has been the author of all the evil now distracting the country,' and by his complaining of Sale and Burnes that, 'with 2000 good infantry, they are sitting down before a fortified place, and are afraid to attack it.'

--45--

Learning that for certain the Dost had crossed the Hindoo Koosh from Nijrao into the Kohistan, Sale, who had been reinforced, sent out reconnaissances which ascertained that he was in the Purwan Durrah valley, stretching down from the Hindoo Koosh to the Gorebund river; and the British force marched thither on 2d November. As the village was neared, the Dost's people were seen evacuating it and the adjacent forts, and making for the hills. Sale's cavalry was some distance in advance of the infantry of the advance guard, but time was precious. Anderson's horse went to the left, to cut off retreat down the Gorebund valley. Fraser took his two squadrons of Bengal cavalry to the right, advanced along the foothills, and gained the head of the valley. He was too late to intercept a small body of Afghan horsemen, who were already climbing the upland; but badly mounted as the latter were, he could pursue them with effect. But it seemed that the Afghans preferred to fight rather than be pursued. The Dost himself was in command of the little party, and the Dost was a man whose nature was to fight, not to run. He wheeled his handful so that his horsemen faced Fraser's troop down there below them. Then the Dost pointed to his banner, bared his head, called on his supporters in the name of God and the Prophet to follow him against the unbelievers, and led them down the slope.

Fraser had formed up his troopers when recall orders reached him. Joyous that the situation entitled him to disobey them, he gave instead the word to charge. As the Afghans came down at no great pace, they fired occasionally; either because of the bullets, or because of an

--46--

access of pusillanimity, Fraser's troopers broke and fled ignominiously. The British gentlemen charged home unsupported. Broadfoot, Crispin and Lord were slain; Ponsonby, severely wounded and his reins cut, was carried out of the mˆlée by his charger; Fraser, covered with blood and wounds, broke through his assailants, and brought to Sale his report of the disgrace of his troopers. After a sharp pursuit of the poltroons, the Dost and his followers leisurely quitted the field.

Burnes wrote to the Envoy--he was a soldier, but he was also a 'political,' and political employ seemed often in Afghanistan to deteriorate the attribute of soldierhood--that there was no alternative for the force but to fall back on Cabul, and entreated Macnaghten to order immediate concentration of all the troops. This letter Macnaghten received the day after the disaster in the Kohistan, when he was taking his afternoon ride in the Cabul plain. His heart must have been very heavy as he rode, when suddenly a horseman galloped up to him and announced that the Ameer was approaching. 'What Ameer?' asked Macnaghten. 'Dost Mahomed Khan,' was the reply, and sure enough there was the Dost close at hand. Dismounting, this Afghan prince and gentleman saluted the Envoy, and offered him his sword, which Macnaghten declined to take. Dost and Envoy rode into Cabul together, and such was the impression the former made on the latter that Macnaghten, who a month before had permitted himself to think of putting a price on 'the fellow's' head, begged now of the Governor-General 'that the Dost be treated more handsomely than was Shah Soojah, who had no claim on us.' And then followed a strange confession

--47--

for the man to make who made the tripartite treaty, and approved the Simla manifesto: 'We had no hand in depriving the Shah of his kingdom, whereas we ejected the Dost, who never offended us, in support of our policy, of which he was the victim.'